Submitted:

18 March 2025

Posted:

19 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

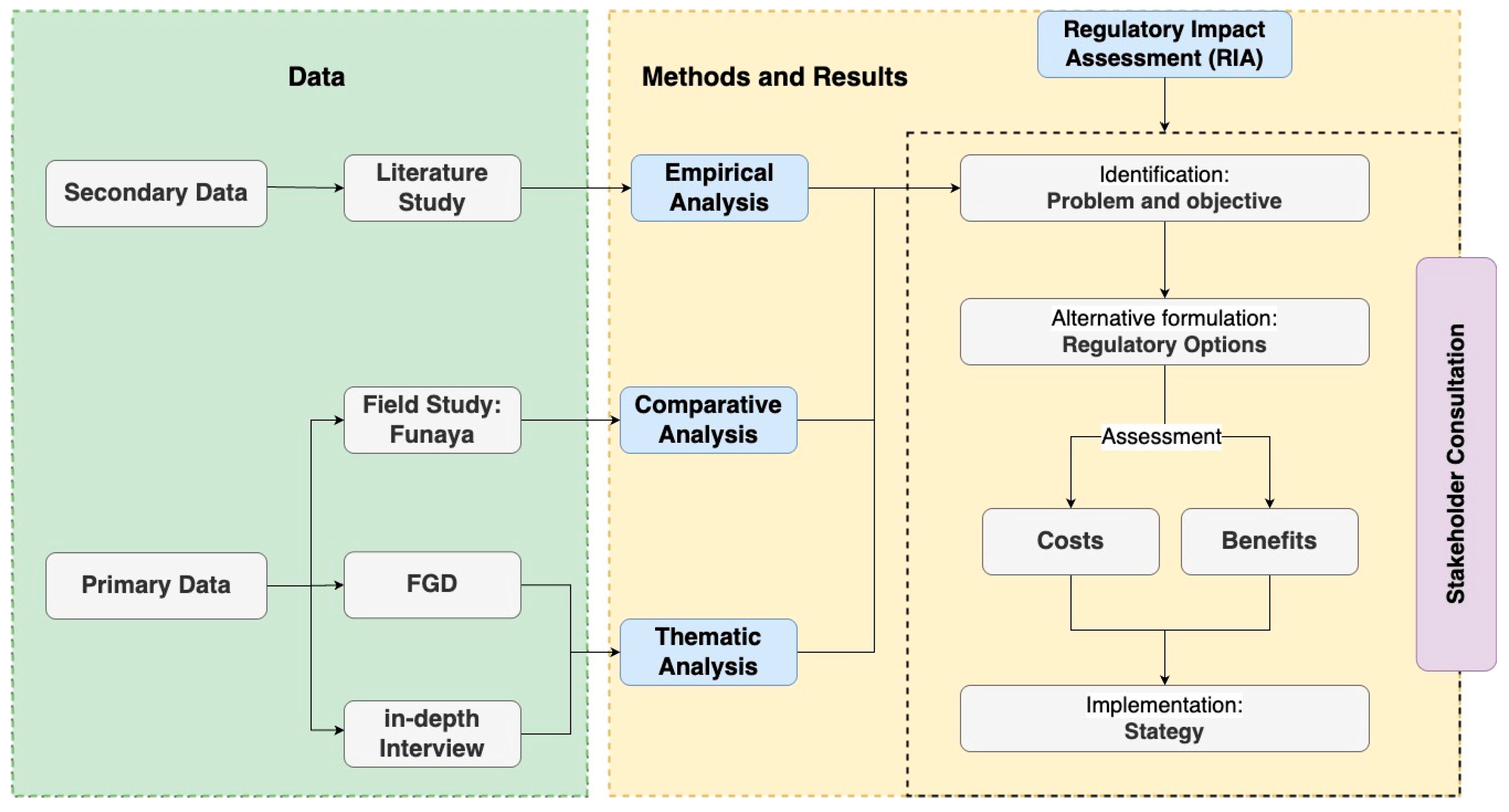

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification of Issues and Objectives

3.1.1. Potential for Improving Existing Regulations

3.1.2. Regulations That Need to Be Enhanced, Developed, and Established

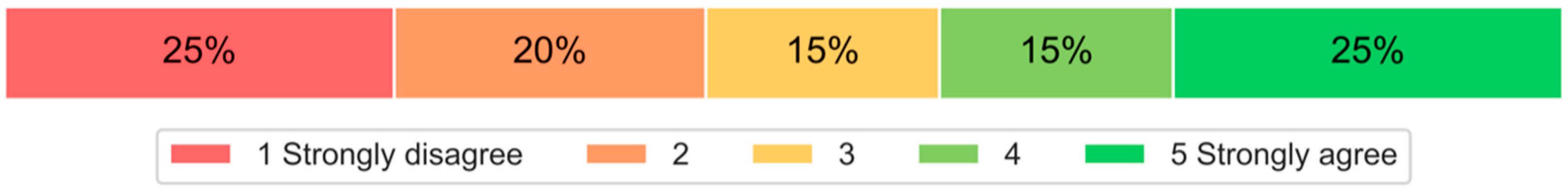

3.1.3. Respondents’ Perspectives on Environmental and Settlement Policies for the Bajo Community

- Exclusive Zoning

- 2

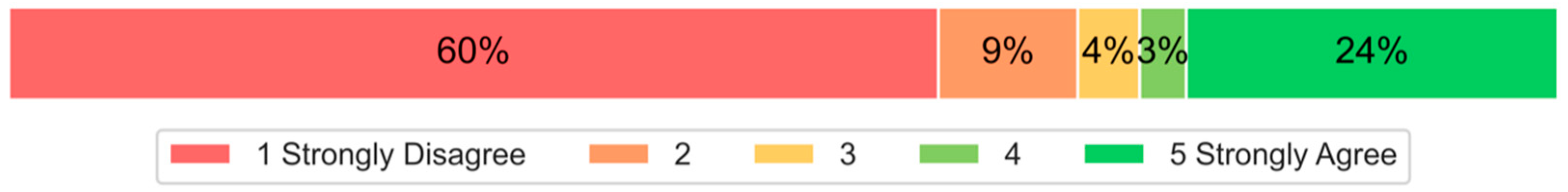

- Local Wisdom and Integral Relationship with the Sea

- Preference for a traditional lifestyle: They prefer approaches according to traditional customs to adopting new technology.

- Resistance to technological change: For example, they prefer traditional wooden boats to modern boats once provided by the government.

- Attachment to the environment: Their houses on water are a physical manifestation of their local wisdom and a way of life passed down through generations.

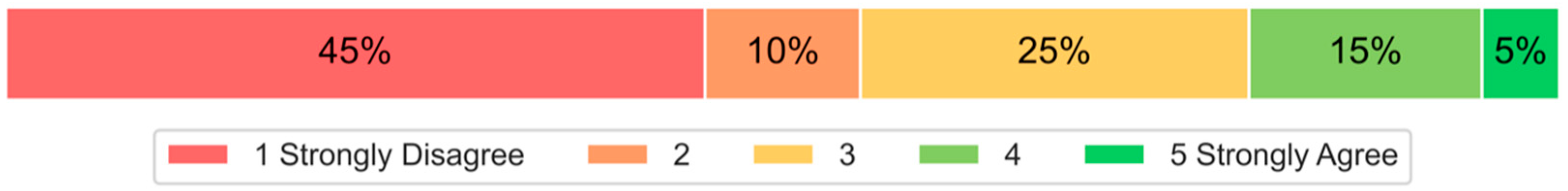

3.1.4. Integration of Land Rights Regulations in Maritime Areas: Stakeholder Perspectives and Local Wisdom

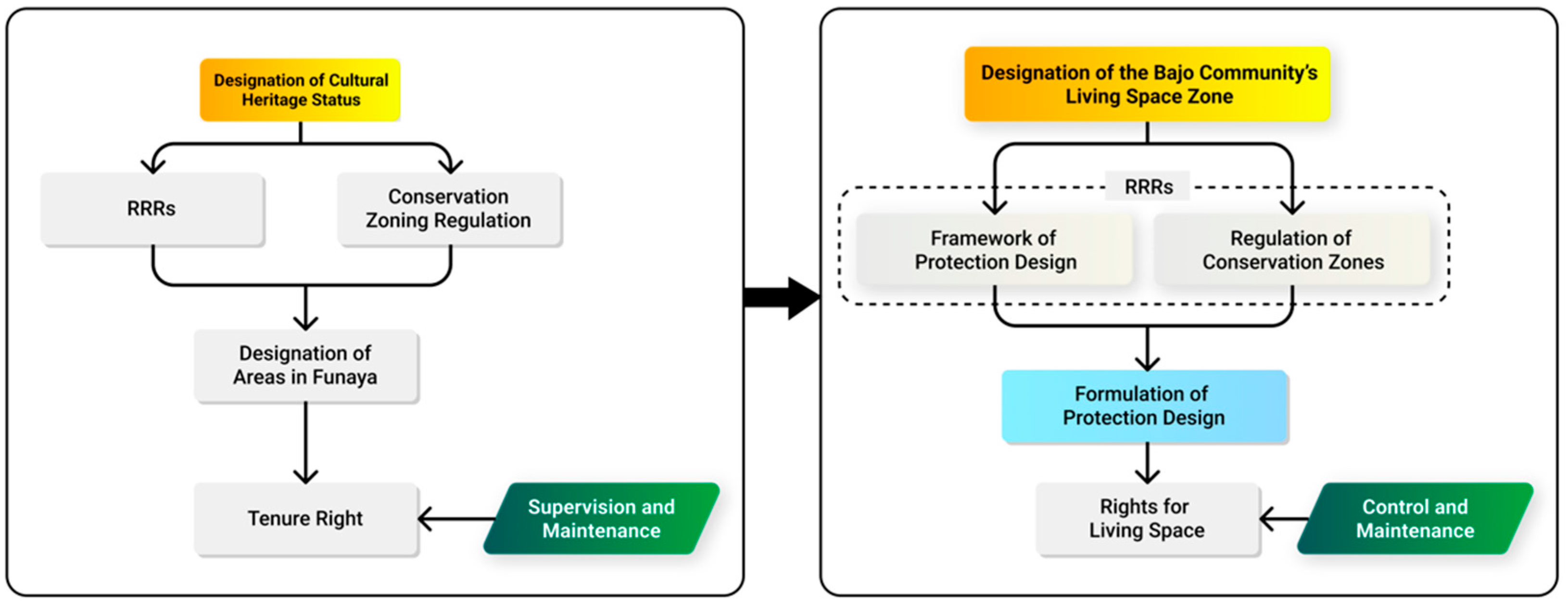

3.1.5. The Need to Adapt Japan’s Funaya Protection Design as a Benchmark

3.2. Formulation of Policy Alternatives

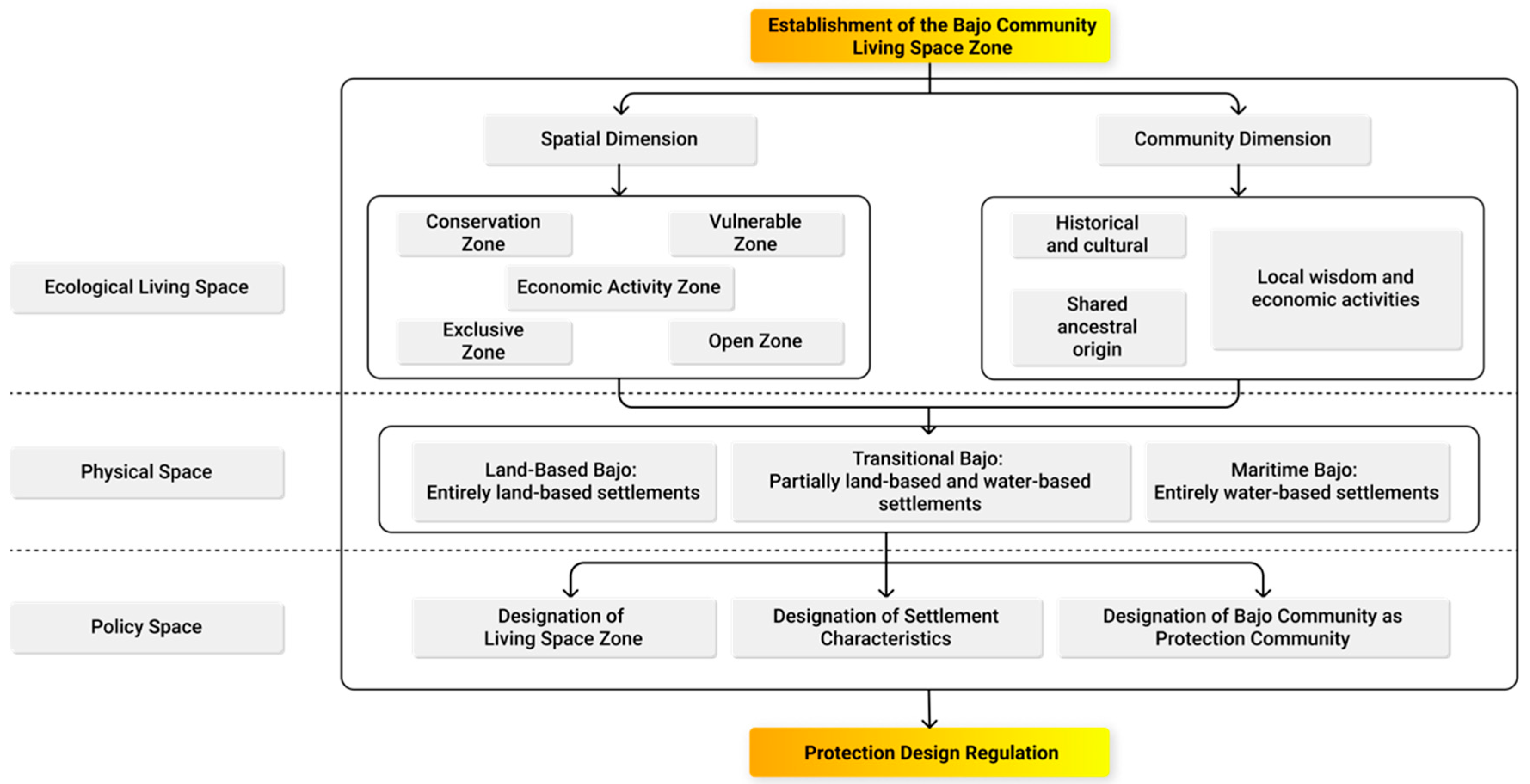

3.2.1. Establishment of the Bajo Community’s Living Space Zone

-

Conservation Zone (Zone A)This zone focuses on ecosystem and biodiversity protection. It is designed to support the preservation of natural resources essential to the Bajo community’s livelihood. Permitted activities in this zone include educational programs, research, and community-based ecotourism.

-

Vulnerable Zone (Zone B)This zone consists of areas at high risk of natural disasters such as abrasion, floods, or tsunamis. Infrastructure development in this zone must include risk mitigation measures, such as the provision of evacuation facilities and designated shelter areas for the Bajo people.

-

Economic Activity Zone (Zone C)This zone is designed to support community-based economic activities sustainably. It includes Maritime Bajo settlements, where the Bajo people manage marine resources following their local traditions. The zone is also supported with market infrastructure, ports, and marine product processing facilities.

-

Exclusive Zone (Zone D)This zone is reserved for the exclusive use from the Bajo community. Within this zone, the Bajo people have the right to manage natural resources without the threat of exploitation by external parties. Traditional regulations, such as bapongka, are enforced to ensure the sustainability of marine ecosystems.

-

Open Zone (Zone E)This zone is designated for public access for general purposes, such as transportation routes and traditional fishing areas. The management of this zone must prevent privatization or any violations that could harm the ecosystem.

-

Land-Based Bajo (Settlement A)Entirely land-based settlements, focused on access to basic facilities such as electricity and clean water.

-

Transitional Bajo (Settlement B)Partially land-based and water-based settlements, requiring proper sanitation facilities such as bio-septic tanks to protect the environment.

-

Maritime Bajo (Settlement C)Entirely water-based settlements, where residency is permitted only in Zone C with additional requirements, including mandatory household waste management.

3.2.2. Protection Design Regulation

-

Rights to Natural Resources

- Conservation Zone (Zone A): Right to sustainably utilize this zone for education, research, and community-based ecotourism.

- Economic Activity Zone (Zone C): Right to manage marine resources traditionally while considering ecosystem regeneration.

- Exclusive Zone (Zone D): Exclusive right to protect the area and its marine resources from external exploitation.

-

Rights to Settlements and Basic Infrastructure

- Bajo Daratan (Land-Based Settlements): Right to basic facilities such as clean water, sanitation, electricity, and road access.

- Bajo Peralihan (Transitional Settlements): Right to sanitation infrastructure, such as bio-septic tanks, to ensure environmental sustainability.

- Bajo Maritim (Maritime Settlements): Right to establish residences in designated areas within Zone C with legal recognition.

-

Rights to Cultural Recognition

- Right to preserve customs, cultural rituals, and traditions that define the Bajo community identity.

- Right to legal protection for traditional practices such as bapongka (seasonal fishing restrictions based on customary laws).

-

Prohibition of Destructive Activities

- Zone A (Conservation Zone): Destructive activities such as using non-eco-friendly fishing gear or waste dumping are prohibited.

- Zone B (Vulnerable Zone): Building constructions that increase disaster risks without mitigation measures are prohibited.

- Zone C (Economic Activity Zone): Unsustainable resource extraction methods are prohibited.

-

Prohibition of Privatization and Land Use Conversion

- Zone E (Open Zone): Privatization or exclusive claims over public-use areas are prohibited.

- Bajo Settlements: Unauthorized land use conversion is not allowed without government and local community approval.

- Prohibition for External Parties: Zone D (Exclusive Zone): Outsiders are prohibited from exploiting resources or entering the area without Bajo community permission.

-

Responsibilities of the Bajo Community

- Environmental Conservation: Actively maintaining ecological sustainability through traditional practices and participating in conservation efforts.

- Settlement Management: (i) Bajo Peralihan: Required to have bio-septic tanks to prevent water pollution. (ii) Bajo Maritim: Obliged to protect exclusive territories by complying with traditional rules like bapongka.

-

Responsibilities of the Government

- Policy and Infrastructure Management: (i) Providing disaster mitigation training, disaster-resilient infrastructure, and early warning systems in Zone B. (ii) Ensuring economic infrastructure such as markets, ports, and marine product processing facilities in Zone C.

- Legal Protection: (i) Protecting Bajo community rights over their exclusive territories. (ii) Monitoring and preventing illegal activities that damage marine and terrestrial ecosystems.

3.2.3. Developing Protection Design

-

Establishment of the Living Space Zones:

- Conservation Zone (Zone A): Designated for the protection of ecosystems and biodiversity.

- Vulnerable Zone (Zone B): Established to mitigate disaster risks through resilient infrastructure.

- Economic Activity Zone (Zone C): Supports sustainable, community-based economic activities.

- Exclusive Zone (Zone D): Reserved for resource management exclusively by the Bajo community.

- Open Zone (Zone E): Public-access areas governed by spatial regulations.

-

Establishment of the Community Designation:

- The Bajo community is designated as a Protected Community, ensuring legal recognition of their traditions, culture, and ancestral heritage.

- Legal protection mechanisms are developed based on historical and cultural data to safeguard the community’s territories.

-

Establishment of the Settlement Characteristics:

- Land-Based Bajo (Settlement A): Fully land-based settlements with access to basic facilities such as clean water and electricity.

- Transitional Bajo (Settlement B): Partially land- and water-based settlements that require bio-septic tanks to prevent pollution.

- Maritime Bajo (Settlement C): Fully water-based settlements, where residences can only be built in designated Zone C areas.

-

Environmental and Sustainability Norms:

- The Bajo community is responsible for maintaining ecosystem balance by adhering to local conservation regulations.

- The government must provide training, disaster mitigation facilities, and eco-friendly infrastructure, such as early warning systems and evacuation shelters.

- Resource exploitation by external parties is prohibited without community and governmental approval.

-

Security and Infrastructure Norms:

- Transitional and Maritime Bajo settlements must have sanitation systems like bio-septic tanks for waste management.

- Public infrastructure and settlements must be adapted to environmental risks, such as coastal erosion in transitional areas.

-

Exclusive Rights for the Bajo Community:

- The community has the right to sustainably utilize marine resources following local traditions such as bapongka.

- The community has exclusive rights to protect their territories from external exploitation without permission.

3.3. Cost–Benefit Analysis

3.4. Implementation Strategy

3.4.1. Dissemination Mechanism

-

Public Information Dissemination

- Utilizing local media, such as radio and visual posters, to communicate the benefits of the policy.

- Organizing discussion forums with the Bajo community to explain their rights, restrictions, and responsibilities related to protection design and living spaces in coastal areas.

-

Education and Training

- Conducting training on the use of environmentally friendly fishing gear.

- Enhancing the community’s understanding of the importance of coastal ecosystem conservation and maritime culture.

-

Collaboration with Partners

- Involving NGOs, community leaders, and academics in developing socialization modules based on local wisdom and culture.

- Encouraging the Bajo community to be pioneers in spreading messages to their community and serving as role models for other coastal indigenous groups.

3.4.2. Monitoring Implementation

-

Community-Based Supervision

- Establishing local monitoring groups consisting of the Bajo community to oversee zoning implementation and area protection.

- Providing training for these groups to identify violations, such as illegal exploitation by external parties.

-

Technology-Supported Monitoring

- Utilizing drones and GIS-based applications for periodic mapping of areas.

- Developing a digital reporting system that enables the community to report issues in real-time.

-

Periodic Evaluation

- Conducting quarterly evaluations involving all stakeholders to review policy effectiveness and identify areas for improvement.

- Preparing monitoring reports as reference material for further decision-making processes.

3.4.3. Incentives and Sanctions

- Financial and Infrastructure Incentives: Support in the form of subsidies for the renovation or construction of eco-friendly traditional stilt houses, promoting cultural and environmental sustainability, will be provided.

- Involvement in Culture-Based Tourism Programs: Communities following the protection design guidelines will be directly involved in culture-based tourism programs, creating additional income opportunities through locally managed tourism.

- Priority in Training and Assistance Programs: These communities will receive priority in sustainable coastal resource management training programs, strengthening their skills and knowledge in ecosystem conservation.

- Security and Recognition of Protection Zones: The community will receive protection from external exploitation through the enforcement of exclusive zoning and official recognition of the Bajo community Protection Zone. This ensures legal certainty and safeguards their living spaces and cultural identity.

- Loss of Financial and Infrastructure Incentives: Communities that do not follow the guidelines will not receive subsidies for the renovation or construction of traditional stilt houses in coastal areas.

- Exclusion from Priority in Training Programs: Groups that fail to comply will not be included in training and mentoring programs for sustainable coastal resource management.

- Exclusion from Culture-Based Tourism Programs: Communities that do not adhere to the guidelines will not be included in culture-based tourism programs that provide additional income opportunities.

- Loss of Security and Protection Zone Recognition: Their community areas will not be recognized as protected zones, and their asset legalization process will become more complicated and prolonged, adding to their administrative burden.

4. Conclusions

5. Recommendation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATR/BPN | Agrarian Affair and Spatial Planning/National Land Agency |

| FGDs | Focus Group Discussions |

| HAT | Land Ownership |

| HP3 | Coastal Water Concession Rights |

| KKPRL | Coastal and Small Islands Spatial Planning |

| NGOs | Non-Government Organizations |

| RIA | Regulatory Impact Assessment |

| RRRs | Rights, Restrictions, Responsibilities |

| UUD 1945 | The 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia |

References

- C. A. Sather, “Sea Nomads and Rainforest Hunter-gatherers: Foraging Adaptations in the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago,” in The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives, P. Bellwood, J. J. Fox, dan D. Tryon, Ed. Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Publication, Australian National University, 1995, hal. 229–268.

- B. O. Nababan, Y. Christian, A. Afandy, dan A. Damar, “Integrated Marine and Fisheries Center and priority for product intensification in East Sumba, Indonesia,” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Volume 414, The World Seafood Congress 2019 – “Seafood Supply Chains of the Future: Innovation, Responsibility, Sustainability,” vol. 414, no. 1, Sep 2020.

- B. C. Chaffin, H. Gosnell, dan B. A. Cosens, “synthesis and future directions,” Ecology and Society, vol. 19, no. 3, 2014.

- F. Berkes, “Evolution of Co-Management: Role of Knowledge Generation, Bridging Organizations, and Social Learning,” Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 90, no. 5, hal. 1692–1702, 2009.

- J. A. Matthews, Encyclopedia of Environmental Change. SAGE Publications, Ltd., 2014.

- UUD, “Undang-Undang Dasar 1945.” Pemerintah Republik Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia, 1945.

- E. Schlager dan E. Ostrom, “Property-Rights Regimes and Natural Resources: A Conceptual Analysis,” Land Economics, vol. 68, no. 3, hal. 249–262, 1992.

- Permen ATR/KBPN Nomor 17, “Peraturan Menteri ATR/KBPN Nomor 17 Tahun 2016 tentang Penataan Pertanahan Di Wilayah Pesisir dan Pulau-Pulau Kecil,” JDIH (Legal Documentation and Information Network) of Ministry of ATR/BPN. Berita Negara RI No.573/2016, Jakarta, Indonesia, 2016.

- PP 18/2021, “Peraturan Pemerintah Republik Indonesia Nomor 18 Tahun 2021 Tentang Hak Pengelolaan, Hak Atas Tanah, Satuan Rumah Susun, dan Pendaftaran Tanah,” JDIH (Legal Documentation and Information Network) of Ministry of ATR/BPN. Lembaran Negara RI No.28/2021, Jakarta, Indonesia, 2021.

- Permen ATR/KBPN Nomor 18, “Peraturan Menteri ATR/KBPN Nomor 18 Tahun 2021 tentang Tata Cara Penetapan Hak Pengelolaan dan Hak Atas Tanah,” JDIH (Legal Documentation and Information Network) of Ministry of ATR/BPN, 2021.

- Batubara, “Hak Bermukim Masyarakat Adat Lokal dan Tradisional di Perairan Pesisir.” 2023.

- O. Green et al., “Barriers and bridges to the integration of social–ecological resilience and law,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, vol. 13, no. 6, hal. 332–337, 2015.

- L. S. Evans, N. C. Ban, M. Schoon, dan M. Nenadovic, “Keeping the ‘Great’ in the Great Barrier Reef: large-scale governance of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park,” International Journal of the Commons, vol. 8, no. 2, hal. 396, 2014.

- S. M. Morcom, D. Yang, R. S. Pomeroy, dan P. A. Anderson, “Marine ornamental aquaculture in the Northeast U.S.: The state of the industry,” Aquaculture Economics & Management, vol. 22, no. 1, hal. 49–71, 2018.

- D. R. Armitage et al., “Adaptive co-management for social–ecological complexity,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, vol. 7, no. 2, hal. 95–102, 2009.

- Ediawan, Y. Komariah, F. Rustiani, Ha. Kusdaryanto, M. Mustafa, dan B. Wijayanto, Pedoman Penerapan Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA), Revisi 200. Kementerian Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional/Bappenas, 2009.

- P. Duangputtan dan N. Mishima, “Study on the adaptation of Funaya houses under the Denken system in the preservation area of Ine town, Japan,” Journal of Environtmental Design, vol. 7, hal. 84–87, 2020.

- Asnaedi, J. Winoto, H. Harianto, dan L. K. Sari, “Hak Tanah Perairan Suku Bajo: Identifikasi Dan Solusi Kelemahan Aspek Legal,” Bina Hukum Lingkungan, vol. 9, no. 2, 2025.

- Asnaedi, J. Winoto, Harianto, dan L. K. Sari, “[in-review] Analysis of the Influence of the Rights, Restrictions, and Responsibilities (RRRs) Framework on the Fulfilment of the Bundle of Rights and the Obedience of the Bajau Community,” 2025.

- Kirkpatrick dan, D. Parker, “Regulatory impact assessment and regulatory governance in developing countries,” Public Administration and Development, vol. 24, no. 4, hal. 333–344, 2004.

- World Bank, “Regulatory Impact Assessment Documents.” 2024.

- Q. Treasury, “Published Regulatory Impact Statements.” 2024.

- J. R. Drummond dan C. M. Radaelli, “Behavioural Analysis and Regulatory Impact Assessment,” European Journal of Risk Regulation, vol. 15, no. 4, hal. 950–965, 2024.

- M. Obie, “Perubahan Sosial Pada Komunitas Suku Bajo Di Pesisir Teluk Tomini,” Al-Tahrir: Jurnal Pemikiran Islam, vol. 16, no. 1, hal. 153, 2016.

- F. Rubama, I. Hasan, R. Limonu, F. Lihawa, dan N. Sune, “Adaptasi Masyarakat Suku Bajo Terhadap Bencana Di Desa Torsiaje, Kecamatan Popayato, Kabupaten Pohuwato, Provinsi Gorontalo,” Geosfera: Jurnal Penelitian Geografi, vol. 3, no. 1, hal. 10–16, 2024.

- S. Mukramin, “Strategi Bertahan Hidup: Masyarakat Pesisir Suku Bajo di Kabupaten Kolaka Utara,” Walasuji : Jurnal Sejarah dan Budaya, vol. 9, no. 1, hal. 175–186, 2018.

- F. C. Mustofa, T. Aditya, dan H. Sutanta, “Evaluation of participatory mapping to develop parcel-based maps for village-based land registration purpose,” International Journal of Geoinformatics, vol. 14, no. 2, hal. 45–55, 2018.

- M. Obie dan L. Lahaji, “Coastal and Marine Resource Policies and the Loss of Ethnic Identity of the Bajo Tribe,” Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, vol. 9, no. 3, hal. 147, Mei 2020.

- E. Prasetio dan I. Ronaboyd, “Bajo Tribal Marine Customary Rights Supervision: A Reform with Archipelagic Characteristics,” Jurnal Kajian Pembaruan Hukum, vol. 2, no. 2, hal. 227, 2022.

- Harun, “Bajo’s Living Law on Environmental Preservation to Support Economic Improvement,” Dialogia Iuridica, vol. 14, no. 1, hal. 76–94, 2022.

- Ristea, O. Cristina, dan V. Lavric, “Assessment of Heavy Metal Contamination of Seawater and Sediments Along the Romanian Black Sea Coast : Spatial Distribution and Environmental Implications,” 2025.

- Afrianti, B. Surya, dan K. Aksa, “Peningkatan Kualitas Permukiman Suku Bajo Desa Popisi Kecamatan Bangggai Utara Kabupaten Banggai Laut,” Journal of Urban Planning Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, hal. 140–146, 2021.

- J. Kitzinger, “Qualitative Research: Introducing focus groups,” BMJ, vol. 311, no. 7000, hal. 299–302, 1995.

- R. A. Powell dan H. M. Single, “Focus Groups,” International Journal for Quality in Health Care, vol. 8, no. 5, hal. 499–504, 1996.

- Silverman, Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analyzing talk, text and interaction, 3rd ed. Sage Publications Ltd, 2006.

- Suhartini, “Kajian Kearifan Lokal Masyarakat Dalam Pengelolaan Sumberdaya Alam Dan Lingkungan,” in Prosiding Seminar Nasional Penelitian, Pendidikan dan Penerapan MIPA, 2009.

- P. S. Soselisa, R. Alhamid, I. Y. Rahanra, dan U. Pattimura, “Integration of Local Wisdom and Modern Policies: The Role of Traditional Village Government In The Implementation of Sasi In Maluku,” Baileo: Jurnal Sosial Humaniora, vol. 2, no. 1, hal. 63–75, 2024.

| Aspects | Funaya | Bajo Tribe |

|---|---|---|

| Location and Characteristics | Located along Ine Bay, traditional wooden structures are built over water, serving as residences and boat garages. | Located in coastal waters, stilt houses are built over water, serving as residences and maritime activity hubs. |

| Protection Regulations | Governed by the Act on Protection of Cultural Properties and local zoning regulations. | No specific protection regulations, subject to general policies such as the Agrarian Law and KKPRL |

| Land Ownership | Perpetual ownership with cultural zone protection granted to building owners. | Ownership is time-limited, such as right of use or building use rights, with no automatic renewal guarantees. |

| Renovation and Conservation | Renovation must use natural materials (wood) and requires local government approval; renovation subsidies up to 70%. | Renovations are self-managed with no specific standards, minimal government support, or incentives. |

| Building Function | Used as residences, restaurants, museums, and cultural tourism accommodation. | Mostly used as residences, with little diversification for economic or tourism purposes. |

| Government Support | Financial subsidies, cultural conservation training programs, and promotion as a tourism destination. | Minimal financial or policy support for cultural and environmental preservation of the Bajo community. |

| Environmental Management | Exclusive zoning system to control access and protect coastal ecosystems. | No specific zoning or ecosystem management in Bajo community areas. |

| Community Participation | Local communities are involved in planning and management, with clear responsibilities in conservation. | Limited community participation in policymaking or management, often only as policy objects. |

| RRRs | Rights: land ownership; restrictions: forbiddance on new constructions in preservation zones; responsibilities: cultural and environmental preservation. | Rights: time-limited rights such as right of use or building use rights; restrictions: no clear limitations; responsibilities: collective responsibilities remain undefined. |

| Living Space Zones | Zone A: Conservation |

C: Utilizing zones for educational programs, research, and community-based ecotourism. G: Regulating policies and regulations to protect ecosystems. |

C: Must not carry out destructive activity such as using non-environmentally friendly fishing gear or waste disposal. G: Must not give resource exploitation permit to any party. |

C: Actively participating in preserving the sustainability of zones by complying with conservation regulation. G: Providing conservation training and critical zone monitoring facilities. |

| Zone B: Vulnerable |

C: Prioritizing the development of disaster-resistant infrastructure, such as evacuation sites and wave barriers. | C: Must not develop settlements which potentially increase the risk of disaster impact. | C: Participating in disaster mitigation training and utilizing the provided facilities. G: Providing early warning systems and conducting regular evacuation simulations. |

|

| Zone C: Economic Activities |

C: (1) The right to legally reside in this area with security guarantees and recognized ownership under the law. (2) Access to basic facilities such as clean water, sanitation, and adequate electricity. G: Managing the zone by providing spatial planning that supports community needs and ecosystem sustainability. |

C: (1) Prohibited from engaging in activities that harm the environment, such as indiscriminate disposal of domestic or industrial waste. (2) Land use conversion is prohibited without community and government approval. G: External parties cannot be granted permission for activities that threaten sustainability or the welfare of the Bajo community without consultation and approval from the Bajo community. |

C: (1) Managing the area by balancing settlements and sustainable economic activities. (2) Participating in government programs to improve economic capacity and environmental management. G: (1) Providing subsidies or incentives for community-based economic development. (2) Ensuring the availability of supporting infrastructure, such as traditional markets, adequate ports, and seafood processing facilities. (3) Providing training for the community to improve economic skills and environmentally friendly resource management. |

|

| Zone D: Exclusive |

C: (1) Full rights to manage and sustainably utilize marine resources in accordance with the bapongka tradition. (2) Exclusive rights to protect the area from access and exploitation by external parties without permission. (3) The right to determine harvesting periods for marine resources to ensure ecosystem regeneration. | C: (1) Maintaining the exclusive area by involving indigenous communities for supervision and sustainable management. (2) Complying with bapongka traditional rules governing the timing and methods of marine resource utilization. (3) Reporting illegal activities, such as fishing by external parties, to the relevant authorities. G: (1) Providing legal protection for the exclusive territory of the Bajo community. (2) Establishing monitoring and law enforcement mechanisms against violations in the exclusive area. |

||

| Zone E: Open |

C: Free access to this area for public activities such as transportation, fishing, and waterways for transit by any party. G: To regulate and manage spatial planning in this zone for public interests and environmental sustainability. |

C and G: It is prohibited to claim or privatize this area as the property of any individual or specific group. | C: Using this zone responsibly, including maintaining cleanliness, avoiding environmental damage, and complying with applicable regulations. G: (1) Developing spatial planning that includes the utilization of public property for various needs. (2) Supervising activities in open zones to ensure no violations against the ecosystem. |

|

| Community | Historical and Cultural | C: The right to preserve cultural traditions, rituals, and customs that have been passed down through generations. | C: It is prohibited to commercialize traditions in ways that degrade their original cultural values. | C: Actively participating in cultural preservation activities through local communities or organizations. G: Providing education and awareness about the community’s cultural history to younger generations. |

| Common Ancestry | C: The right to official recognition of the community’s origins and identity as part of local history. | C: It is prohibited to claim land ownership without legitimate legal grounds. | C: Supporting cooperation among community members to maintain unity and harmony. G: Providing legal mechanisms to regulate the recognition of community origins based on historical records. |

|

| Local Wisdom and Economic Activities | C: The right to utilize local natural resources sustainably according to community traditions. | C: It is prohibited to use exploitative methods that are environmentally unfriendly or damage the ecosystem. G: External parties shall not be granted exploitation rights that threaten the community’s sustainability. |

C: Participating in environmental conservation. G: Providing training and support for infrastructure to facilitate economic activities. |

|

| Community | Land-Based Bajo: Settlement A: Entirely Land-Based | C: (1) The right to live and reside safely, legally, and sustainably in the community’s territory in accordance with customary and national law. (2) The right to access basic facilities such as electricity, clean water, sanitation, and healthcare services. |

C: It is prohibited to convert land use without approval from the community and government. G: Commercial exploitation permits that disrupt the land ecosystem’s balance shall not be granted. |

C: Participating in environmental conservation. G: Providing training and support for infrastructure to facilitate economic activities. |

| Transitional Bajo: Settlement B: Partly Land-Based | C: Mandatory use of bio-septic tanks to prevent water pollution. G: Construction permits shall only be granted in Zone C areas. |

C: (1) Actively contributing to environmental sustainability on land and at sea by ensuring sanitation facilities meet standards. (2) Mandatory use of bio-septic tanks to prevent water pollution. (3) Mandatory household waste management. G: Providing disaster mitigation facilities to prevent the impact of coastal erosion in transitional settlements. |

||

| Maritime Bajo: Settlement C: Entirely Water-Based | C: Establishing residences in Zone C, designated as a settlement zone over water. |

| Aspect | Costs | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Economy | No additional costs for zoning management or implementation. | Loss of community-based economic potential. |

| Environment | No major change or environmental interventions. | Risk of environmental damage due to unregulated resource exploitation. |

| Social and Culture | No immediate social structure changes. | Loss of local traditions and cultural identity due to lack of legal protection. |

| Infrastructure | No additional costs for infrastructure development. | Lack of infrastructure for disaster mitigation and sanitation in transitional settlements. |

| Aspect | Costs | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Economy | Initial investment in infrastructure and community training. | Increased community-based economic activities (Zone C). |

| Environment | Operational costs for zoning enforcement and monitoring illegal activities. | Ecosystem and biodiversity protection through Zone A. |

| Social and Culture | Community education costs and adaptation to new systems. | Protection of traditions (bapongka) and Bajo identity through Zone D. |

| Infrastructure | Costs for disaster-resilient infrastructure and modern sanitation maintenance. | Provision of sanitation facilities (bio-septic tanks) and disaster risk mitigation (Zone B). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).