1. Introduction

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, drones) are becoming increasingly popular in wildlife research, providing unique opportunities for data gathering and observation. Recent applications of drones encompass a wide array of endeavors, from gathering biological samples [

1], monitoring morphometric attributes [

2], and collecting behavioral data [

3,

4] to conducting census surveys [

5], anti-poaching surveillance [

6], and mapping species habitat use [

7]. This technology has enabled researchers to access remote locations [

8], study fine-scale wildlife movements, and employ automated imagery analysis techniques for efficient species detection [

9].

Despite the promising advancements and diverse applications, the growing integration of drones into wildlife studies has raised concerns about potential misuse and increased anthropogenic pressure. While in some cases, drones present a less disruptive alternative to traditional data collection methods [

10], studies indicate that their presence can still influence animal behavior, trigger physiological stress responses, and, in some cases, lead to habitat displacement. Media reports have highlighted instances of wildlife harassment captured in social media videos, fueling public apprehension [

11]. The portrayal of drones as sources of disturbance in natural habitats has led to discussions about the need for comprehensive research and clarity on disturbance issues [

11]. Concerns have led some countries to ban drones in protected areas, underlining the urgency of addressing these increasing anthropogenic pressures [

12].

Literature suggests that drone noise is a key factor influencing the behavior of terrestrial, avian, and aquatic species during drone encounters [

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, visual stimuli, such as the drone’s presence and proximity, can also contribute to behavioral changes, particularly in birds, which may perceive drones as potential threats or predators [

17,

18,

19,

20]. The mammalian auditory system, being often highly sensitive, triggers rapid neural responses, leading to swift fight-or-flight reactions [

21]. The extent of disturbance depends on multiple factors, including flight altitude, speed, approach distance, and environmental conditions such as habitat type and time of day. Different species exhibit varying sensitivities, with some showing habituation over time while others display heightened avoidance behaviors. Although studies have explored specific drone stimuli such as sound [

22] and visual cues [

23], there remains a limited understanding of the distinct impacts of these signals on animal behavior. To bridge this gap and raise awareness of the impact of drone disturbances on wildlife, this paper provides a comprehensive review of existing research on the wildlife.

This paper emphasizes the dual perspective of animal welfare and the potential behavioral alteration caused by drone disturbances, advocating for a comprehensive examination of the disturbance impact of drones. Moreover, this work raises a fundamental question for the engineering community: Can we design drones that minimize disturbance to animals while complying with legislation that requires transparent drone operations? Addressing this challenge requires a concerted effort to develop drone technologies that mitigate disturbance impact, ensuring that the use of drones aligns with ethical considerations in wildlife research.

Building on prior research [

24] that provided a preliminary analysis of drone-induced wildlife disturbances through select case studies, this review expands upon that foundation by integrating a broader array of studies. It offers a more comprehensive examination, addressing additional factors such as species-specific responses, drone flight characteristics, and environmental conditions. The goal of this extended work is to provide a more thorough understanding of the effects of drones on wildlife and to emphasize the importance of developing guidelines and technology for the ethical use of drones in research.

By synthesizing findings from a broad spectrum of studies, this review aims to enhance our understanding of how different species respond to drones and identify key factors that influence the extent of disturbance. Furthermore, it advocates for the development of ethical guidelines that balance the need for technological innovation in wildlife research with the imperative to minimize harm to the animals under study. Understanding these interactions is essential for balancing conservation efforts with responsible drone use and ensuring that technological advancements align with wildlife protection principles. This paper contributes to the ongoing discourse on the responsible use of drones in wildlife research, highlighting the need for continuous innovation in drone design and operation to safeguard ecological integrity.

2. Material and Methods

The literature on the use of UAVs for monitoring and studying wildlife, their interactions, and associated effects was extensively reviewed up to December 31, 2023. To supplement this review, we conducted a targeted search for scientific literature that specifically addresses drone noise and its impact on terrestrial wildlife. Using keywords such as ‘drone,’ ‘unmanned aerial vehicle,’ ‘unmanned aerial system,’ ‘remotely-piloted aircraft system,’ ‘unmanned aircraft,’ ‘UAV,’ ‘UAS,’ and ‘RPAS,’ combined with the terms ‘wildlife,’ ‘disturbance,’ ‘animals,’ ‘birds,’ ‘marine,’ ‘aquatic,’ ‘reptiles,’ ‘terrestrial,’ and ‘megafauna,’ we identified relevant publications through Google Scholar search and Web of Science. Our initial search revealed a scarcity of published material specifically addressing the impact of drone noise on terrestrial habitats. As a result, we expanded our literature review to include drone impact studies on aerial and aquatic habitats. To ensure a comprehensive review, scientific publications included peer-reviewed journal articles, university dissertations (including Master’s theses), conference proceedings, and project reports. Additionally, we broadened our search by tracing relevant publications cited within other studies. This expanded scope yielded a total of 92 publications referencing disturbance impact, encompassing factors such as flight angles, approach distance, wind masking, noise, and visual stimuli.

This search was also complemented by the drone working group at The Wildlife Society, which has identified 1,572 peer-reviewed articles on wildlife and drones as of December 15, 2024. We reviewed the references within this collection to extract research specifically addressing drone disturbances on wildlife, focusing on drone operational factors, sensory stimuli, species and habitat-specific sensitivities, and physiological and behavioral responses. Our integrated approach offered to provide a comprehensive understanding of both the broader context of drone utilization in wildlife studies, as well as specific insights into the effect of drone noise on animals.

This review proceeds by first discussing the types of drones used in wildlife research, focusing on their operational characteristics and how these impact wildlife in various settings. The paper then transitions into an analysis of the interactions between drones and wildlife, emphasizing key factors such as flight altitude, speed, proximity, and noise. Species-specific responses to these variables are explored in detail, with particular attention given to the behavioral reactions observed across terrestrial, aerial, and aquatic species. Detailed tables are included throughout these sections, providing a clear summary of findings and highlighting patterns of responses among terrestrial, aerial, and aquatic species. Following this, a framework for recommended drone operation parameters is developed based on existing literature, providing guidelines for minimizing wildlife disturbance. The discussion extends to broader challenges, including the complexity of environmental stimuli and the long-term impact of repeated drone exposure. Ethical considerations are integrated throughout the analysis, emphasizing the need for responsible drone usage in wildlife research. The paper concludes by proposing future directions for technological advancements and the development of species-specific mitigation strategies. Finally, the importance of global collaboration in standardizing ethical drone practices is underscored to ensure the responsible integration of UAVs into ecological research.

3. Drones and Wildlife

The earliest observations of aerial vehicle-induced disturbance behaviors were noted in studies that primarily focused on using aircraft to estimate population numbers [

25]. As researchers began to understand the negative impact that animals’ aversive reactions could have on the accuracy of the census data, the issue gained more direct and focused attention [

26,

27]. This section explores the various factors that influence how drones impact wildlife, covering operational elements such as flight altitude, speed, and approach distance, which affect different species in unique ways. Additionally, we examine how the time of the day, weather conditions, and environmental factors influence wildlife responses, emphasizing the need for further research. Finally, it looks at how wildlife’s perception of drones can be influenced by their habitat, biological state, and the presence of predators, which can heighten sensitivity to drone disturbances. This section aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complexities involved in using drones in wildlife research, with an emphasis on minimizing their impact on animals.

3.1. Drone Types

Within the drone landscape, three primary categories stand out: fixed-wing, multirotor, and hybrid Vertical Take-off and Landing (VTOL) drones, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Fixed-wing drones, which resemble small aircraft, are extensively used in professional mapping applications due to their high efficiency in covering large areas [

28]. These drones operate by using power exclusively for forward propulsion and rely on a single rigid wing to generate lift, eliminating the need for vertical rotors. Fixed-wing drones are particularly effective for tasks such as comprehensive mapping, infrastructure inspection, surveying, and agricultural monitoring over expansive geographical regions. They can fly at higher altitudes to achieve the same ground sample distance (GSD) as multirotor drones flying at lower altitudes, due to their ability to carry heavier payloads. Additionally, fixed-wing drones are generally quieter than multirotor drones, which can be advantageous if species have a low threshold for disturbance.

In contrast, multirotor drones, including quadcopters and hexacopters, are favored by professionals for their agility and precision [

28]. These drones excel in tasks requiring detailed maneuverability, such as aerial photography, surveillance, inspection, and short-range deliveries. They are designed with multiple rotors that provide superior control and stability during flight, although this design limits their endurance and range compared to fixed-wing and VTOL drones. Multirotors often need to operate at lower altitudes to achieve high-resolution imaging, which can make them more disruptive due to their increased noise levels.

Hybrid VTOL drones represent a recent innovation that combines the vertical take-off and landing capabilities of multirotors with the aerodynamic efficiency of fixed-wing flight. These drones can perform vertical take-offs and then transition smoothly to horizontal flight, allowing them to cover longer distances than multirotor drones. Their aerodynamic efficiency during horizontal flight extends their endurance and range, making them suitable for more demanding missions. Moreover, hybrid VTOL drones can handle larger payloads, which enhances their versatility for tasks such as mapping, inspection, and drone delivery that require both vertical take-off and long-distance travel.

The design differences among drones also affect the noise they generate. Fixed-wing drones are typically quieter than multirotor drones, partly because they can operate at higher altitudes while maintaining the same GSD, which reduces the need for lower, noisier flights. For instance, noise levels in common commercial drones range from as high as 70 dB at close proximity (e.g., the Raven drone at 18 meters Above Ground Level (AGL)) to as low as 30 dB at higher altitudes (e.g., the Draganflyer at 100 meters AGL). These variations demonstrate how drone type, altitude, and proximity to the subject can significantly impact disturbance levels.

Table 1 provides a detailed comparison of noise levels across various drones, illustrating how the operational noise ranges influence their use in wildlife-sensitive environments.

3.2. Operational Factors Influencing Wildlife Responses

The flight characteristics of drones— such as altitude, approach distance, takeoff distance, airspeed, proximity, and approach angle— are critical factors in understanding how drones interact with wildlife across various habitats. These variables are frequently highlighted in the research, underscoring their importance in assessing the impact of drone operations on animals.

Researchers emphasize the significance of approach distance and airspeed in drone studies involving birds, with these factors being key details reported in numerous journal articles. For example, studies on avian responses to drone flights have shown that stationary birds generally exhibit minimal reaction when drones maintain a distance of more than 40 meters during takeoff [

17]. Similarly, drones can approach waterfowl within close proximity (e.g., 4 meters) without causing significant disturbance, provided they avoid direct approaches from above [

18]. Maintaining specific airspeeds (e.g., 20–25 km/h) has also been noted to minimize disturbance, allowing drones to pass by wildlife before they become fully aware of their presence [

33]. In a study involving waterfowl, researchers found that waterfowl on land are more vigilant when approached by drones, with greater disturbance observed at lower altitudes and closer take-off distances. The study recommends a minimum take-off distance of approximately 500 meters and a flight altitude of 100 meters to minimize the risk of geese exhibiting escape behavior [

19]. In another study on gentoo (

Pygoscelis papua) and Adélie (

Pygoscelis adeliae) penguins, researchers found that penguins on Ardley Island exhibited significant behavioral changes, especially at lower altitudes. Adélie penguins responded at 50 meters, while gentoo penguins reacted at 30 meters. Increased vigilance reactions were most pronounced at altitudes of 10–20 meters. While some habituation occurred during horizontal flights, no habituation was observed in vertical flights [

20]. Another study on the Crozet Islands assessed the impact of drones on 11 seabird species, revealing varying responses to drone approaches at different altitudes. The study found that reactions varied by species and altitude: at 50 meters, only one species showed a response, while at 10 meters, most species exhibited significant stress behaviors. Some species, like giant petrels (

Macronectes ssp.) and cormorants (family

Phalacrocoracidae), were highly sensitive, while others, such as certain albatrosses (family

Diomedeidae) and penguins (family

Spheniscidae), showed minimal reaction even at close distances. Notably, king penguins (

Aptenodytes patagonicus) demonstrated a physiological stress response, as indicated by an increased heart rate monitored by biologgers, despite minimal behavioral changes [

34]. These studies highlight the importance of considering species-specific sensitivity when planning drone flights and suggest further research to quantify bird behavior in greater detail [

19]. A study on eastern grey kangaroos (

Macropus giganteus) in urban environments found that while drones often trigger vigilance, kangaroos rarely flee unless the drone flies at an altitude of 30 meters or lower. The research suggests flying drones at altitudes of 60–100 meters to minimize disturbance and calls for further studies on the effects of drone surveys on wildlife behavior [

35]. Similarly, in African reserves, elephants and giraffes have been documented to show increased vigilance when drones approach at distances of 50 meters and 80 meters AGL, respectively [

36]. In a study on bottlenose dolphins (

Tursiops ssp.), researchers conducted 361 drone flights at altitudes ranging from 5 to 60 meters over three years. The research indicated that dolphin behavior was significantly influenced by drone altitude. Prolonged hovering times and larger pod sizes further exacerbated these behavioral responses. Despite these impacts, drones were found to be effective for observing dolphin behavior, and the study recommended flying above 30 meters to minimize disturbance [

14].

These studies highlight the importance of considering species-specific sensitivity when planning drone flights and suggest further research to quantify animal behavior in greater detail.

Table 2 presents a selection of studies that examine how different species respond to drone flights under various conditions, summarizing key factors such as species, UAV type, flight distance, and observed behavioral impact.

3.3. Sensory Stimuli: Noise and Visual Impact

Research has shown varying responses to drones among species, with detection mechanisms still under investigation. For instance, bottlenose dolphins (

Tursiops truncatus), known for their clear visual acuity in both water and air [

45], may rely on visual cues, while manatees (

Trichechus manatus latirostris), with poorer visual acuity [

46], might respond more to the noise produced by drones. Observations of manatees (

Trichechus manatus manatus) exhibiting sudden escape behaviors when approached by drones suggest that noise could plays a significant role in their detection [

47]. Similarly, elephants have been observed to quickly move away from drones due to their bee-swarm-like sounds [

15]. Asian elephants (

Elephas maximus) were shown to become disturbed at an average altitude of 109 m AGL. This heightened sensitivity is thought to be due to their ability to detect and respond to low-frequency sounds, which drones can produce [

13]. These findings corroborate the observations reported by Moss et al., 2011 [

48], which emphasize the reliance of African elephants on their auditory abilities for environmental interaction and communication with peers. Additionally, northern giraffes (

Giraffa camelopardalis) have demonstrated reactions to drones flying at altitudes exceeding 100 meters AGL. Their sensitivity may be influenced by their exceptional height, as being the tallest land animal places their auditory system closer to the drone’s noise source—around 5 meters closer than that of other terrestrial species [

13]. Similarly, a study that assessed the behavioral responses of southern white rhinos (

Ceratotherium simum) to drone flights found that animals could perceive the drone up to 100 meters AGL and that acoustic output alone was enough to initiate a reaction [

49]. Duporge et al., 2021 [

50] contrasted sound profiles of seven drone systems at various altitudes with the audiograms from 20 mammal species. The research found a trade-off between image resolution and sound levels where noise drops below a threshold of 40 dB or where further altitude increases provide minimal additional noise reduction. This method provides valuable guidelines for drone use in wildlife research and conservation, with potential applications for other species and drone systems. Among species without audiograms, the giant anteater (

Myrmecophaga tridactyla)—an endangered species and the largest in the Pilosa order—was exposed to drone studies for the first time in [

51]. Due to its limited auditory and visual capabilities, the giant anteater showed a high tolerance for sound pressure before exhibiting any behavioral changes, as predicted [

51].

Research also suggests that drones can disturb animals, particularly through visual cues when noise is masked by environmental sounds. One hypothesis is that the visual impact of drones may mimic the shape or movement of predatory birds, triggering instinctive defensive or escape behaviors, particularly among species sensitive to aerial threats [

52,

53]. From the perspective of birds, the presence of drones during overflights can affect their behavior, as certain species may perceive drones as a threat, particularly those that are preyed upon by avian predators [

54]. The shape and wing profile of certain drones have been identified as factors influencing the reactions of waterfowl, with profiles resembling raptors causing the most disturbance to wildlife [

55]. Disturbance tends to occur more frequently during drone banking maneuvers, takeoff, or landing, especially when these actions happen over or near a flock, leading to the postulation that birds may interpret these movements as resembling the swooping of a predatory bird [

55,

56]. For example, lekking prairie chickens (

Tympanuchus cupido) display a heightened sensitivity to drone overflights within altitudes ranging from 25 to 100 meters [

57]. This heightened sensitivity may also be attributed to the vulnerability of displaying birds to potential attacks by hawks [

58]. Beyond evasive behaviors, some bird species were documented engaging in harassment, mobbing, or direct attacks on drones mid-flight [

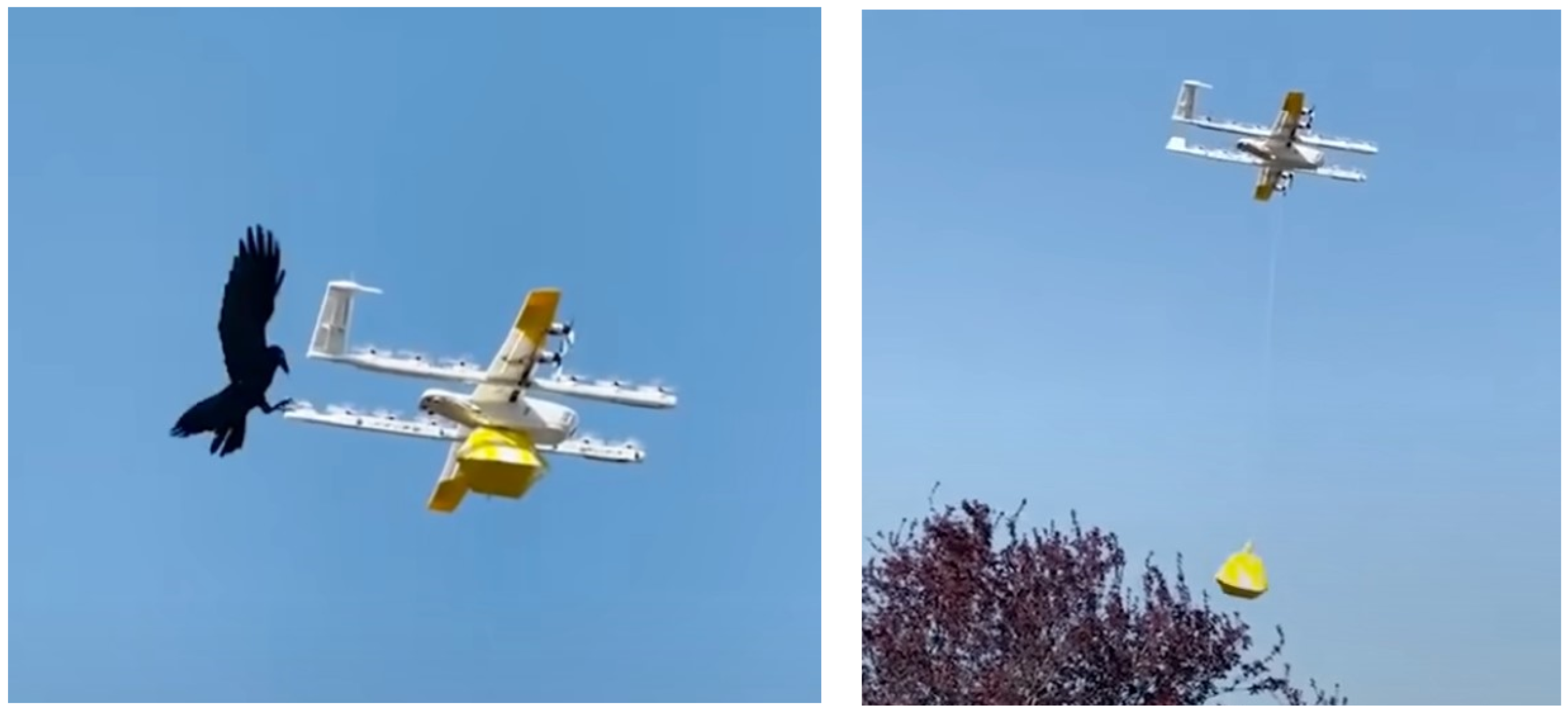

59]. A visual representation in

Figure 2 depicts a raven attacking a delivery drone.

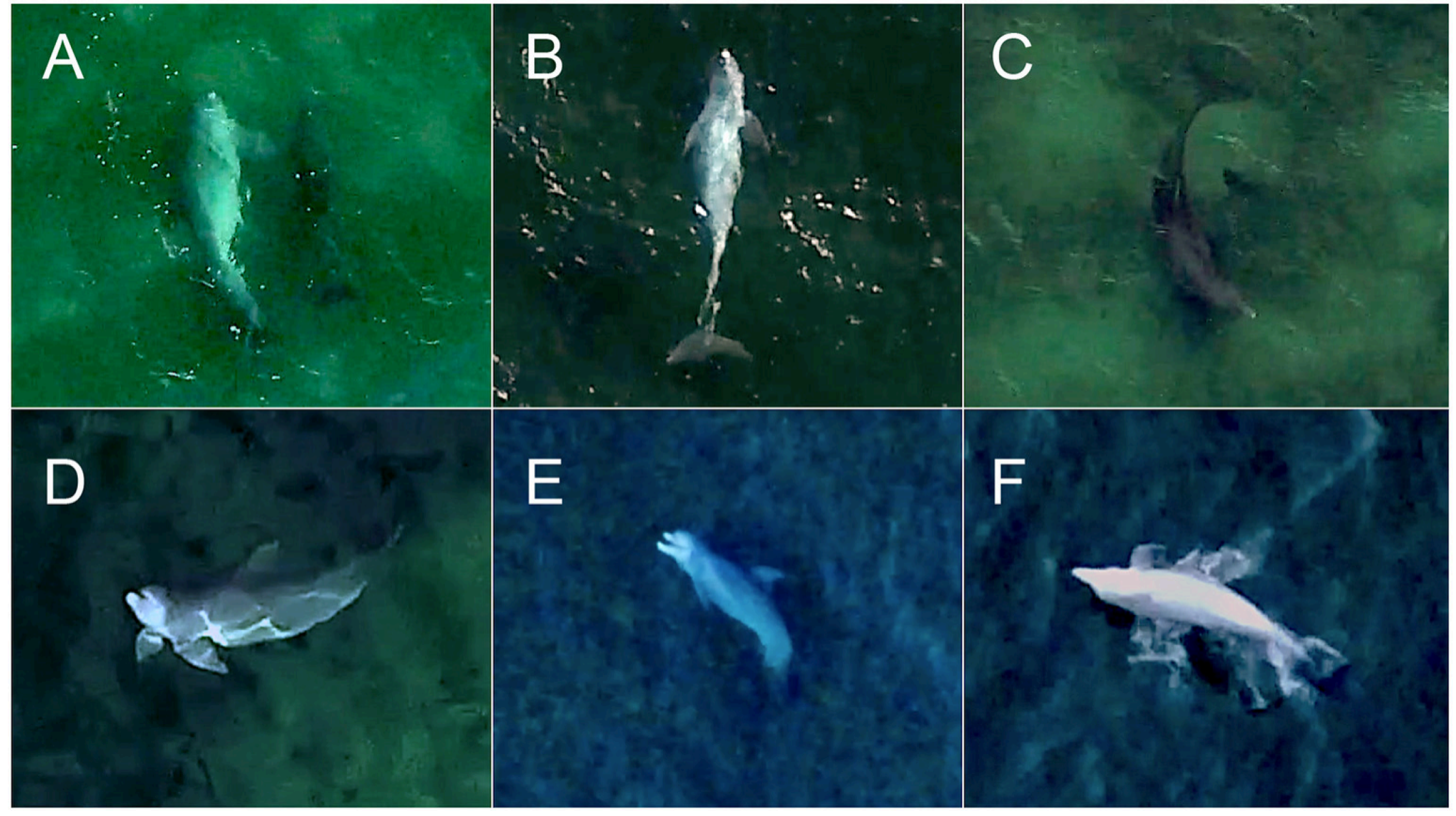

A study utilizing DJI-Phantom2 Vision+, DJI-Phantom3 Pro, and DJI-Phantom4— evaluated the responses of coastal bottlenose dolphins (

Tursiops ssp.) and Antillean manatees (

Trichechus manatus manatus) to drone flights in Belize. Dolphins exhibited mild curiosity at altitudes of 11–30 meters, particularly when alone or in small groups, while manatees displayed stronger disturbances, fleeing at distances from 6 to 104 meters [

47]. These findings highlight the multifaceted nature of drone-wildlife interactions, where both the type of drone and its sensory stimuli affect the behavior of various species.

Table 3 summarizes selected studies that explore the influence of drone noise and visual stimuli on various species, highlighting their responses to different UAV models and flight conditions.

3.4. Species and Habitat-Specific Sensitivities

Drones have demonstrated significant promise for non-invasive wildlife observation, however, their effect on animal behavior can vary significantly based on species-specific traits and environmental conditions. A growing body of evidence highlights these impacts, providing the basis for developing methodological frameworks to guide permissible disturbance levels during observational studies, such as setting minimum flight altitudes for specific species [

36,

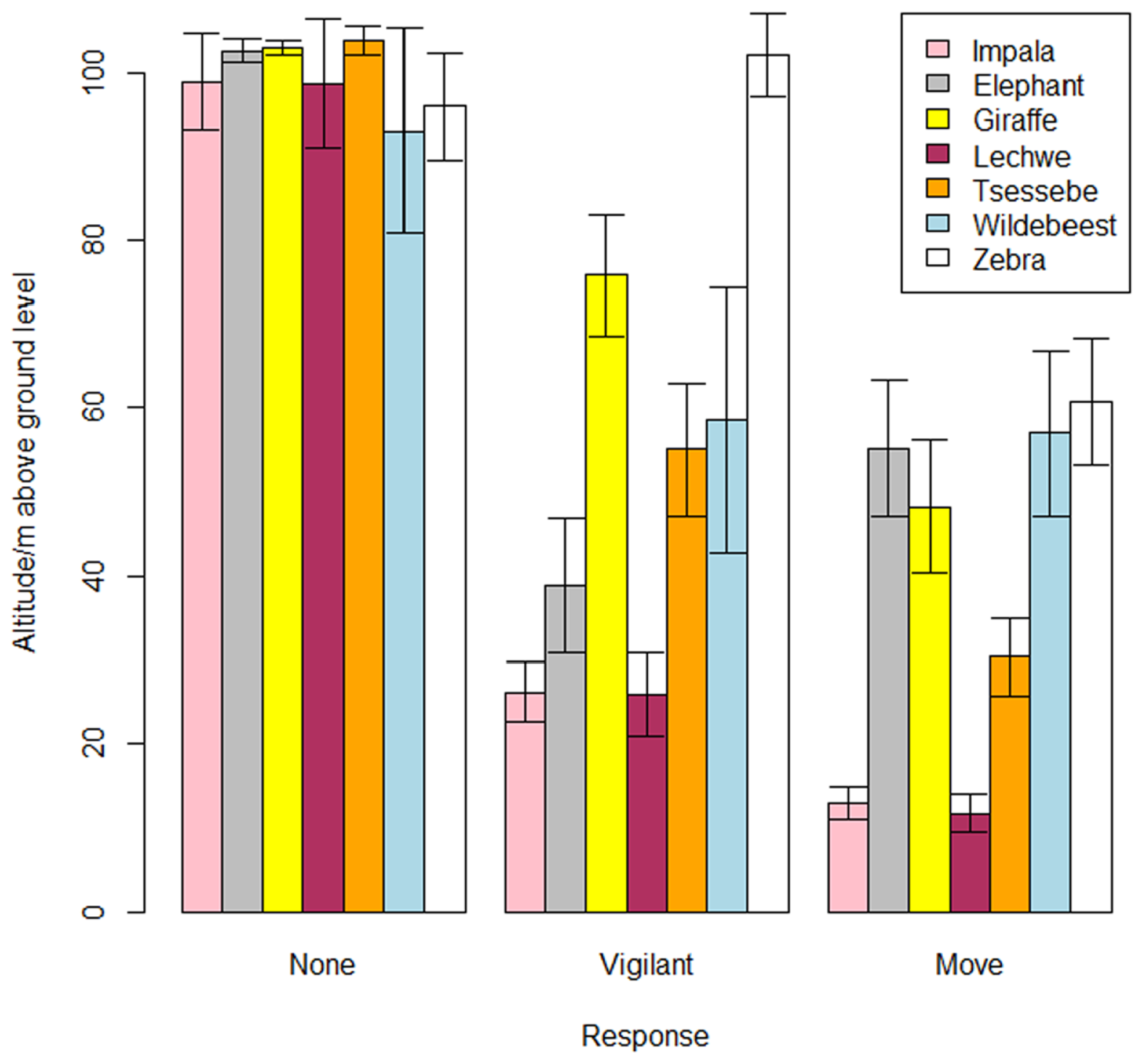

47]. For example, a study examining seven African herbivore species revealed negative responses to drones, which were flown at different altitudes, as depicted in

Figure 3. The vigilance threshold varied across species: african elephants (

Loxodonta africana), nothern giraffes (

Girafa camelopardalis), wildebeest (

Connochaetes taurinus), and plains zebras (

Equus quagga) avoided drones at around 50–60 meters AGL, while tsessebe reacted at 30 meters AGL. In contrast, impala (

Aepyceros melampus) and lechwe (

Kobus leche) only moved when drones were about 15 meters AGL [

36]. Interestingly, in the case of plains zebras, no response was recorded at around 80 meters AGL, but vigilance was observed at 100 meters. This counterintuitive behavior may stem from factors such as the drone’s trajectory, environmental conditions like wind amplifying noise at higher altitudes, or the zebras’ line-of-sight perception. Such observations highlight the complexity of species-specific sensitivities and the need for further investigation to better understand the interplay between drone flight parameters and wildlife responses.

Nevertheless, the recommendations derived from these studies often do not permit generalizability, since they are limited by the specific environmental contexts in which they were conducted. Moreover, the effects of drone disturbances are not constant throughout the day, as the natural soundscape and visual conditions vary significantly between day and night. Drone noise and lighting create dynamic scenarios where animal responses may differ based on the time of day. Consequently, variations in behavior between day and night, differing environmental conditions throughout the day, and advancements in drone technology call for a deeper investigation into how drone impacts on wildlife vary over a 24-hour cycle and whether they remain consistent across species [

65].

Environmental factors, such as atmospheric conditions, habitat characteristics, and human activity, play a crucial role in shaping wildlife responses to drones. For instance, weather conditions like wind speed, direction, and humidity can amplify or attenuate drone noise. Humid air carries sound waves more effectively, potentially increasing the range at which drone noise affects wildlife [

66]. This can amplify disturbances, particularly in environments where animals rely on acoustic cues for communication, navigation, or predator detection. Similarly, wind direction and speed can alter how noise travels, leading to varying behavioral responses under different weather conditions. For example, wind direction and speed can affect how drone noise travels through an environment. In windy conditions, wildlife might perceive drone noise differently compared to calm weather scenarios, impacting in turn their behavioral responses. Seasonal variations also influence species responses. For example, harbor seals (

Phoca vitulina) show variability in reactions to drone based on the season, with a threshold distance of 80m during the pre-breeding period and heightened agitation at 150m during the molting season [

67].

Human activity further interacts with environmental settings to affect wildlife responses. Animals in remote, undisturbed habitats often exhibit stronger reactions to drones compared to those in anthropogenically influenced environments, where habituation to human presence may occur [

13]. For example, wildlife in tourist-heavy safari parks may show reduced vigilance compared to populations in isolated reserves, where drone noise may be perceived as a novel disturbance.

Beyond environmental factors, ecological and behavioral contexts shape how animals perceive drones. Many species have evolved patterns of activity and habitat use to minimize competition and predation risks [

68]. For instance, prey species might occupy different habitats or be active at different times of day than their predators. Varying predation risk pressure suggests that animals adjust their behavior according to their vulnerability to predators in specific environments, seeking cover or engaging in avoidance strategies to reduce their risk [

69]. The introduction of drones can disrupt these finely tuned behaviors, adding a layer of disturbance that alters how animals allocate time and energy.

In areas with high predator densities, prey species tend to exhibit heightened vigilance, reducing their threshold for responding to novel disturbances like drones [

70]. This heightened vigilance can cause prey species to perceive drones as potential threats, prompting stress or escape behaviors. Even when no direct reaction occurs, the energy and time spent on vigilance can indirectly reduce fitness by diverting resources from natural activities like foraging and parental care. For instance, large groups of herbivores were observed shifting from foraging to vigilance and locomotion during drone scanning flights [

71]. Responses towards drone disturbances may further depend on the landscape characteristics, like visual openness. For instance, [

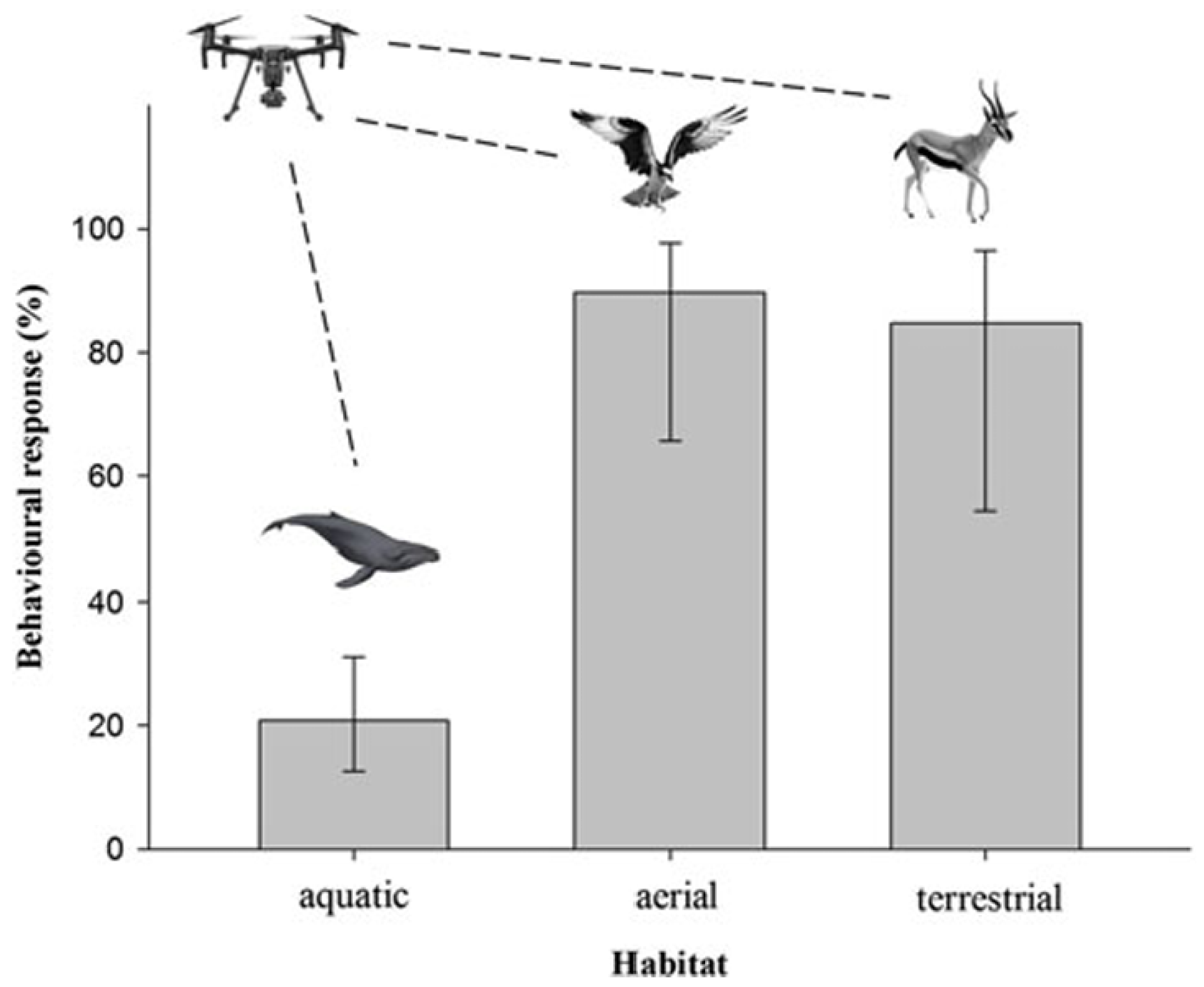

11] revealed that wildlife reactions to aerial vehicles vary depending on the primary habitat type they inhabit (see

Figure 4).

The study examined drone effects on wildlife by combining scientific literature with public YouTube videos to capture behavioral responses of animals to drones. Researchers categorized responses by habitat (aerial, terrestrial, aquatic) and species, revealing that wildlife in aerial and terrestrial habitats demonstrated a higher likelihood of exhibiting behvioral changes in response to aerial vehicles. This heightened sensitivity is likely because these species often encounter predators or other threats from above and have developed acute awareness and defensive behaviors to respond quickly to such dangers. In the case of terrestrial mammals, the presence of drones elicits flush responses, hypothesized to serve as a mechanism to avoid encounters with unfamiliar objects [

11]. While drones are extensively researched concerning megafauna [

72] and their use in recreational filming [

12], our comprehension of their impact on animal behavior is incomplete.

Table 4 provides an overview of selected studies investigating species and habitat-specific sensitivities to drone flights, summarizing observed behavioral responses across different environmental contexts.

3.5. Physiological and Behavioral Responses

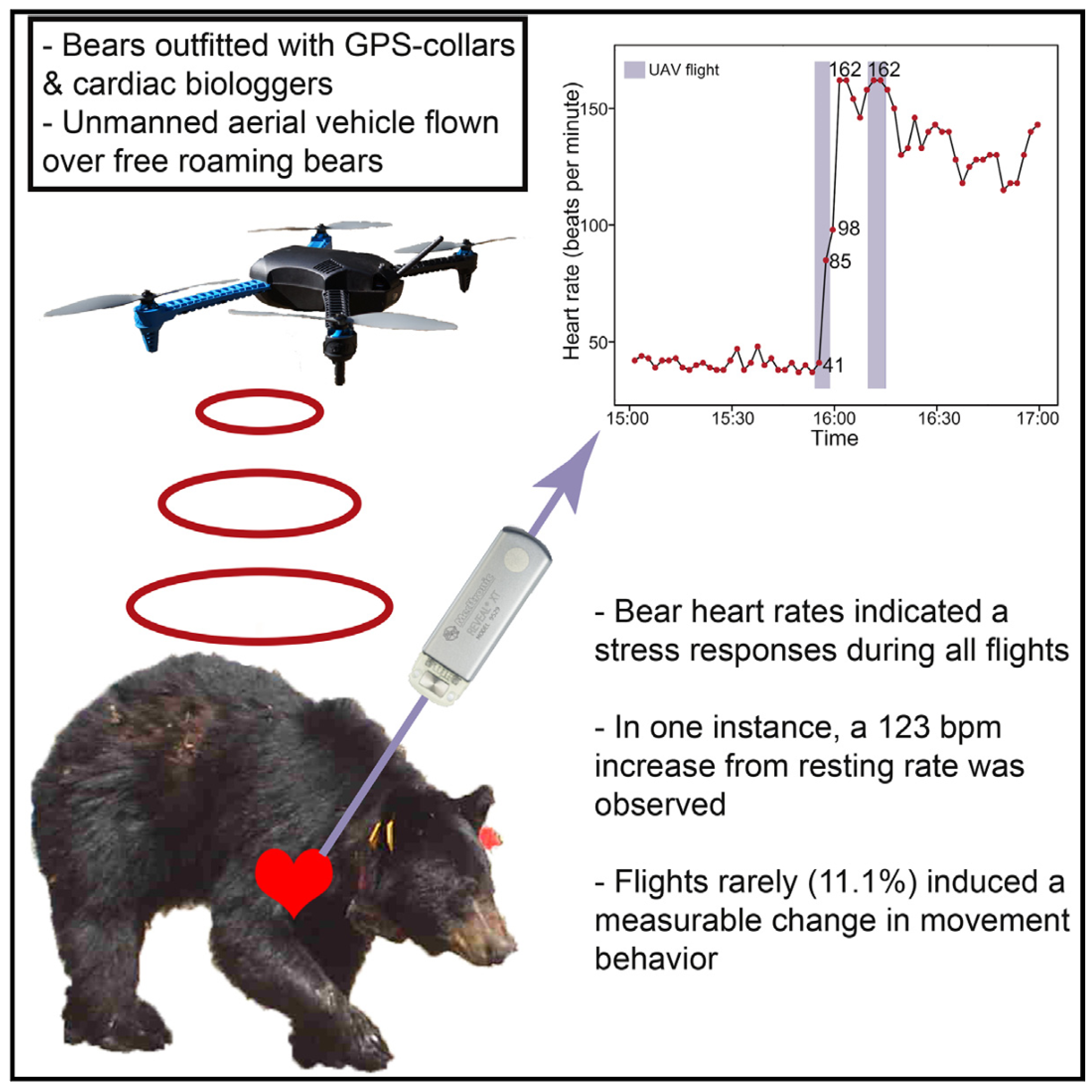

Exploring the potential broader impacts of drone disturbances on wildlife, it is worth noting that these disruptions might also manifest through metabolic and physiological reactions in animals. Research on hibernating black bears (

Ursus americanus), depicted in

Figure 5, showed elevated heart rates in response to overhead drone [

79]. Female American black bear with at least two cubs exhibited the fastest recorded movement, relocating 576.3 meters away within 40 minutes of drone exposure. Southern white rhino mothers with calves showed a greater response to higher drone flights than solitary males or groups of sub-adult individuals, suggesting they may perceive risk differently to other social groupings due to the presence of calf [

49].

The biological state of an animal refers to its physiological condition and the activities it is engaged in at any given time, such as breeding, nesting, molting, or foraging. These states can influence how an animal perceives and reacts to external stimuli, including the presence of drones [

80]. For example, animals in critical life stages like breeding or parental defense of nests tend to exhibit heightened sensitivity to disturbances. Studies show that nesting species, such as Adélie and gentoo penguins, demonstrate varying responses to drone activity [

20], which highlights the necessity of factoring in biological state when planning drone operations [

81,

82,

83]. Disruptions during sensitive periods, such as breeding seasons, can lead to severe behavioral changes, including nest abandonment or increased energy expenditure [

84], potentially affecting reproductive success [

85].

Similarly, nesting birds may engage in nest-guarding behaviors to prevent the intrusion of objects into their territory, and drones may violate these boundaries, causing defensive or flight responses [

80]. Moreover, for these birds, the combined visual and auditory disturbances from drones can lead to increased vigilance, agonistic behavior, standing or walking away from nests, and escape behaviors [

80,

86]. Supporting this hypothesis, a study on great dusky (

Cypseloides senex) and white-collared (

Streptoprocne zonaris) swifts found that drones flying within 40 meters caused significant disturbances, leading over 60% of birds to temporarily abandon their breeding sites. To minimize disturbance, it is recommended that drones maintain a distance of over 50 meters, with recreational flights kept at least 100 meters away from nesting areas [

23].

In contrast, wildlife in aquatic habitats, such as marine mammals, exhibited a lower probability of behavioral responses. This difference can be attributed to their natural environment, which provides a layer of protection from aerial threats. Conventional understanding suggests that small- and medium-sized drones generate minimal underwater noise, seemingly causing little disturbance to marine life [

87]. It has also been discovered that drone sounds do not propagate effectively from the air into the water. The noise generated by drones closely matches the background noise level in shallow water habitats [

85,

88]. Upon comparing recorded drone noise levels with the established hearing thresholds of dolphins and whales, it became evident that, for the majority of these marine mammals, drones operate beneath their auditory thresholds [

89]. An investigation centered on southern right whale (

Eubalaena australis) mother-calf pairs in Australia utilized drone tracking and acoustic tag measurements and found no observable behavioral reactions to close drone approaches [

90]. Other studies, albeit anecdotal, have reported similar outcomes for various baleen whale species, including gray whales (

Eschrichtius robustus) [

91], humpback whales (

Megaptera novaeangliae) [

92], bowhead whales (

Balaena mysticetus) [

81], and blue whales (

Balaenoptera musculus) [

93]. In the case of toothed whales (

Tursiops truncatu), a study [

94] disrupts this presumption, revealing heightened signs of discomfort, including increased reorientation and tail slapping in bottlenose dolphins when a drone operated at a 10m altitude. Intriguingly, these effects dissipate at higher altitudes of 25m to 40m, prompting a reevaluation of the presumed harmlessness of drones near cetaceans. Another study [

47] also showcased the behavioral responses of bottlenose dolphins to drones, as depicted in Fig

Figure 6. This emphasizes the necessity for comparable studies on toothed whales with different hearing thresholds and frequencies to assess their reactions to drone approaches. Additionally, it is essential to consider potential physiological responses, such as stress, in cetaceans exposed to drones, as noted for terrestrial mammals [

79].

The overall impact of these adverse outcomes depends on the extent and severity of the disturbance, as well as the sensitivity of a given species. Researchers should address the complex interplay that exists between specific sensitivities and the different biological states of an animal, in order to accurately interpret drone-induced effects on wildlife behavior [

95]. For instance, variations in foraging behavior can significantly influence responses, particularly under conditions of energy deficit. Animals experiencing hunger or energy shortages may exhibit riskier behaviors or tolerate higher disturbances as they prioritize food acquisition over avoiding potential threats [

96]. This threat-sensitive foraging can explain differences in wildlife responses to drones across seasons and environmental conditions [

97]. The impact of drones during critical periods like breeding and molting seasons further underscores the need for targeted investigations to comprehend the specific challenges posed during these crucial life stages [

98]. Furthermore, age-dependent reactions, as witnessed in varying responses between adult and younger age classes, contribute to a nuanced understanding of the differential stressors imposed by drones at different life stages [

34].

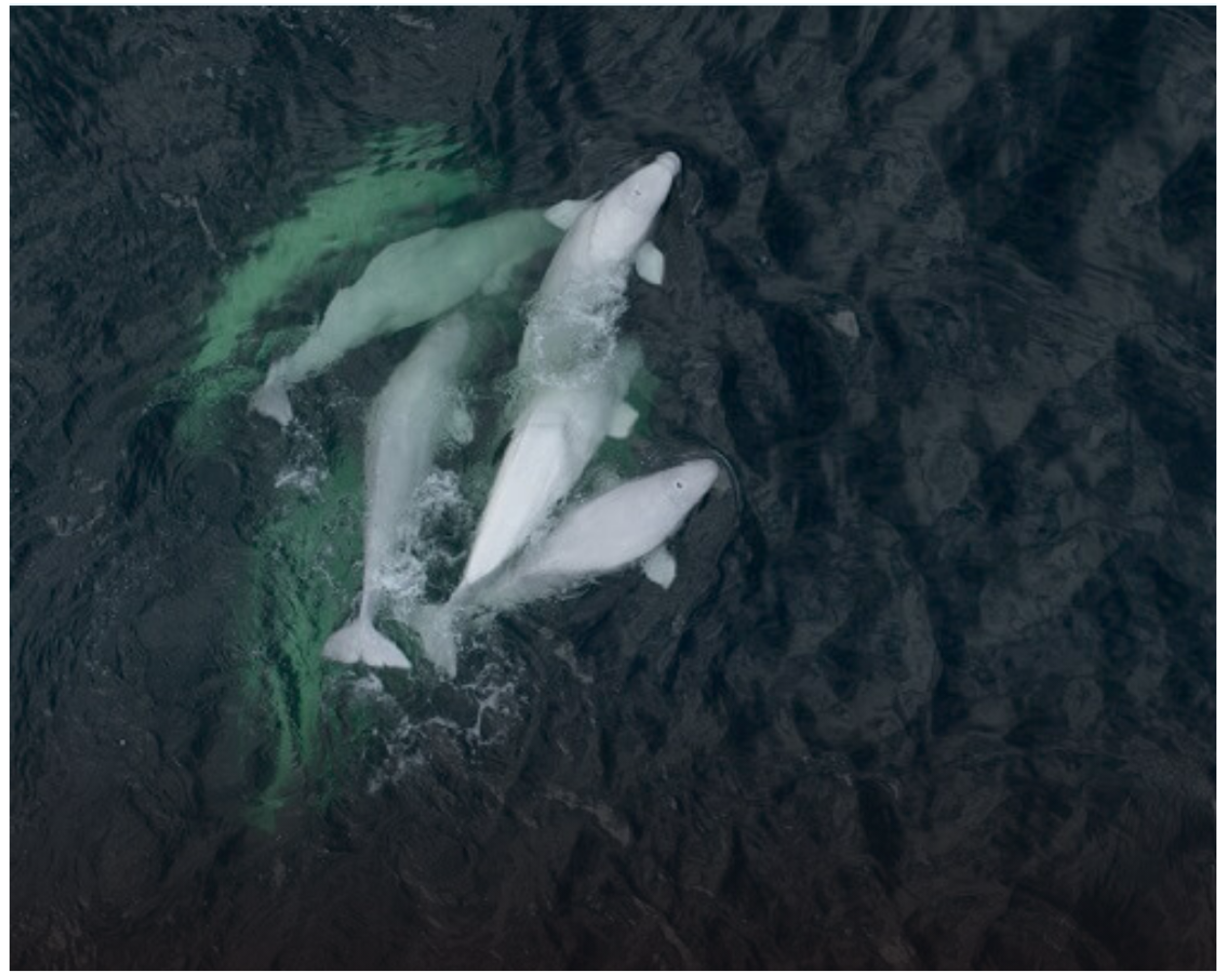

In the realm of group dynamics, collective responses versus those of lone individuals when utilizing drones in ecological studies add another layer of complexity to wildlife research [

14]. Group size has been reported to modify animals’ responses toward drones, with larger groups exhibiting increased avoidance. For instance, beluga whales (

Delphinapterus leucas) in larger groups were observed to exhibit increased avoidance responses and were prone to sudden dives during low-altitude flights, particularly below 23m [

42]. Larger groups experience a higher likelihood of sudden dives (shown in

Figure 7), particularly when a drone initially approaches the group.

Table 5 provides an overview of selected studies investigating the physiological and behavioral responses of wildlife to drone flights, summarizing key observations across different species and contexts.

4. Best Practices and Recommendations

Based on the comprehensive review of the impacts of drone disturbances on wildlife in

Section 3, we propose the following best practices to guide drone-based wildlife research while minimizing the impact on animal behavior and habitat. These guidelines aim to minimize impacts on animal behavior and habitats by standardizing critical parameters, including flight altitude, approach methods, environmental factors, and ethical considerations, establishing a comprehensive framework for responsible drone use.

4.1. Flight Parameters

Altitude is a primary factor influencing wildlife disturbance. Research consistently shows that maintaining altitudes of 40–80 meters reduces stress, particularly for large terrestrial mammals and avian species, as supported by findings in

Section 3.2. For terrestrial animals, operating drones above 35–80 meters minimizes reactions like vigilance or avoidance behaviors [

35,

36]. Nesting birds, especially during breeding seasons, are highly sensitive, and flights should remain at or above 80 meters to avoid reproductive disruptions [

19]. Marine mammals are less disturbed at higher altitudes, though descents below 30 meters can provoke avoidance behaviors and should be restricted to essential tasks [

14].

Proximity to animals also significantly affects their responses (see

Table 2). For large mammals, an approach distance of 30–50 meters minimizes avoidance behaviors, while birds benefit from a horizontal distance of 50–80 meters, especially during nesting or breeding periods. Marine species similarly require lateral distances of 40–60 meters or more to minimize disruption. Closer proximity may be acceptable if animals exhibit neutral behaviors; however, starting observations from farther away and approaching gradually ensures reduced stress.

Drone speed and trajectory further influence animal responses. Operating at speeds below 5 m/s is recommended, particularly near groups or juvenile animals, as slower speeds lower the risk of stress-induced reactions [

39]. Drone approaches from lateral or oblique angles are preferable, as direct overhead paths may mimic predatory movements, particularly for birds and smaller terrestrial species, and are thus best avoided [

17,

18].

4.2. Species-Specific and Contextual Sensitivity

Species-specific sensitivity to drones is influenced by species’ auditory and visual thresholds as well as its biological states. For example, drone activity should be minimized near nesting, breeding, and post-breeding sites during critical periods, with altitudes and distances tailored to reduce disturbances, especially when parental care with juveniles may heighten sensitivity to disturbances in these vulnerable settings [

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85]. No-fly zones may be required for certain species to prevent interference with natural behaviors, which is a direct application of the findings in

Section 3.5.

The ethical aspects of drone usage extend to the frequency and duration of flights, with evidence suggesting that repeated drone exposure can lead to cumulative stress. Limiting drone presence to essential observation periods and avoiding prolonged or repetitive sessions is advised, particularly in high-sensitivity areas or when working with vulnerable or endangered species [

18]. Flight sessions lasting no longer than 10–15 minutes are generally recommended, as shorter observation periods allow animals to resume natural behaviors more quickly, which is crucial for avoiding long-term stress impacts and to avoid disrupting foraging or breeding periods [

104].

Ethical drone use must also adhere to inviolable norms that ensure wildlife welfare. Certain levels of disturbance and any physical harm caused to animals are categorically unacceptable, regardless of the perceived conservation value or data collection goals of the research. Ethical frameworks should guide decision-making by balancing the need for data collection with the goal of minimizing disturbance. These frameworks should consider species vulnerability, the ecological context, and the long-term benefits of the research [

105,

106]. For example, while drone usage in critical habitats may pose temporary risks, it could also yield valuable data to inform habitat protection and restoration efforts. However, such decisions must respect the well-being of wildlife as a top priority.

Mitigation techniques tailored to specific ecosystems and species are essential for minimizing drone-related impacts (see

Section 3.4). These techniques include maintaining optimal altitudes and distances based on behavioral thresholds, using quieter drones with noise-reducing technologies, and employing biomimetic designs that mimic natural elements like birds or insects to reduce perceived threats. In forested ecosystems, for instance, dense vegetation can naturally attenuate drone noise, whereas in open environments, operators should rely on flight parameters that avoid startling animals. Temporal adjustments, such as scheduling flights during non-critical biological periods, and employing adaptive management protocols that adjust drone operations based on real-time behavioral monitoring, are also critical components of ethical drone use.

In addition, researchers can refer to existing ethical frameworks such as the ’Three Rs’ principle (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement), commonly applied in animal research, to minimize harm [

107,

108]. This approach encourages non-invasive practices, such as remote sensing and the use of pre-recorded audio cues, and emphasizes the importance of minimizing stress while maximizing the value of data collected for conservation.

4.3. Environmental and Temporal Considerations

Environmental conditions and the timing of drone operations significantly influence wildlife responses. Flights should be conducted outside peak activity periods, such as dawn and dusk, respecting animals’ natural rhythms and reducing disturbances during vulnerable times, a strategy that aligns with observations in

Section 3.4 on environmental influences on wildlife responses.

Weather conditions also influence drone noise propagation and animal responses. In high-humidity or windy environments, sound tends to carry further, amplifying disturbances for sound-sensitive species [

66]. Drone operations should ideally be rescheduled in such conditions, especially when animals rely heavily on acoustic cues for communication or predator detection [

69,

70]. For studies conducted in open areas where sound-attenuating barriers are absent, opting for calm, clear weather further helps minimize unexpected noise amplification [

63].

4.4. Behavioral Monitoring and Adaptive Drone Management

Real-time behavioral monitoring is a critical component of adaptive drone management in wildlife studies. Telemetry data and real-time video monitoring systems allow researchers to continuously assess wildlife reactions, enabling flight adjustments based on observed behaviors [

109]. For instance, increased vigilance or movement away from the drone, should prompt an immediate increase in altitude or a temporary pause in flights. This responsiveness ensures that drone operations remain minimally invasive and helps preserve natural animal behaviors.

A tiered descent protocol is also recommended to avoid startling wildlife. Initiating observations at a higher altitude (such as 80 meters) and descending only as tolerated by animals is an effective approach. This approach is applicable whether animals show visible signs of stress or not [

44]. In situations where no immediate stress responses are visible, continue to monitor the animals closely, maintaining conservative drone operation standards to preemptively avoid potential stress. Observing animals’ reactions at each altitude and adjusting accordingly is essential for minimizing disturbances.

4.5. Data Collection and Standardized Reporting

Standardized data logging is essential for establishing consistent practices across drone-based wildlife research and for enabling future comparisons across studies [

110]. Researchers are encouraged to develop detailed logs that capture flight parameters, environmental conditions, species observed, and specific behavioral responses at each stage of drone operation. Time-stamped observations should categorize responses into established behavior types, such as vigilance or avoidance, to allow for accurate interpretations and facilitate cross-study analyses.

Supplementary telemetry and acoustic data enhance this standardized approach by providing objective measures of drone noise levels at various distances and altitudes (see

Table 1). Telemetry data, including altitude, speed, and proximity to animals, allows researchers to correlate flight characteristics with observed behaviors and fine-tune protocols for specific species [

111]. For sound-sensitive environments, integrating acoustic measurements with drone audiograms provides a basis for understanding how noise levels relate to species audiograms, ensuring that drone noise remains within acceptable limits [

64].

Finally, establishing a comprehensive shared repository for wildlife drone data would enable collaborative data sharing, enhancing the consistency and effectiveness of drone protocols across studies. Such a database would provide a central resource for researchers, facilitating cross-study comparisons and supporting the development of universally applicable ethical guidelines for drone operations in wildlife studies [

112,

113]. To address potential data privacy and ethical concerns, particularly concerning sensitive information about vulnerable species, the repository should implement strict access controls to ensure that only verified researchers can access the data. Data anonymization can be used where necessary to protect specific locations or individual animals from potential threats. Furthermore, all data sharing and storage has to adhere to legal frameworks of the data’s origin country and operate under the guidance of an ethics committee to comply with international conservation and privacy standards.

5. Discussion and Future Work

In the context of technological innovation intersecting with conservation needs, this study examines the impact of drone noise on animals. This research highlights an opportunity to advance ethical drone use, emphasizing the importance of minimizing disturbances during wildlife monitoring.

5.1. Key Challenges in Wildlife Responses to Drones

The increasing use of drones in scientific, conservation, and recreational applications presents several challenges, particularly regarding wildlife response variability and the mitigation of drone-induced disturbances. This section outlines key challenges in understanding and managing drone impacts on wildlife, serving as a foundation for targeted future directions.

5.1.1. Species Responses and Long-Term Impacts of Drones

One of the primary challenges in using drones for wildlife observation is the variability in species-specific responses and the limited understanding of long-term impacts. Different species—and even individuals within the same species—exhibit a wide range of behavioral reactions to drones, ranging from acute vigilance and escape behaviors to habituation over time. Factors such as auditory and visual sensitivity, habitat type, social context, and life stage significantly influence these responses.

While short-term studies often document immediate behavioral effects, the long-term consequences of repeated or sustained drone exposure remain largely unknown. Repeated disturbances can result in cumulative physiological stress, displacement from critical habitats, or changes in energy allocation, which may reduce fitness and impact population dynamics over time. For instance, chronic exposure to drones during sensitive periods such as breeding, molting, or parental care may disrupt reproductive success, cause nest abandonment, or alter group behaviors. Conversely, some species might become habituated to drone presence over time, potentially altering their natural anti-predator behaviors and increasing their vulnerability to other threats.

Future Research Need: Developing a comprehensive and standardized framework for monitoring drone impacts across species and over extended periods is critical. This framework should collect species-specific data across diverse environmental contexts, examine habituation effects and behavioral plasticity, and track cumulative impacts such as stress biomarkers, reproductive success, and changes in movement or behavior over time. Understanding the long-term effects of repeated exposure will allow researchers to balance the benefits of drone use with the need to safeguard wildlife welfare.

Proposed Approach: Longitudinal studies and meta-analyses are needed to consolidate knowledge on drone responses, allowing for generalizable guidelines that can be adapted for specific species and conditions. Monitoring programs using technologies such as GPS collars, remote cameras, and biometric sensors should be implemented to document wildlife responses before, during, and after repeated drone exposure. These efforts will provide a robust understanding of both species-specific variability and the cumulative long-term effects of drone use. Additionally, integrating stress-related physiological data, such as cortisol levels, with behavioral observations will offer deeper insights into how drone exposure influences wildlife health and fitness. Such research is essential to inform sustainable practices, ethical guidelines, and policy decisions for the responsible use of drones in wildlife observation.

5.1.2. Limitations in Multi-Species Risk Assessment

The current body of research primarily focuses on individual species or narrow taxonomic groups, with few studies examining the broader ecological impact of drones on multi-species communities or ecosystems. As a result, risk assessments lack comprehensive data on how drone operations affect diverse wildlife populations and interspecies interactions within shared habitats.

Future Research Need: Establish multi-species assessment protocols that include diverse taxa and ecological interactions. Understanding drone effects across different species cohabiting in the same ecosystem can improve conservation strategies.

Proposed Approach: Encourage cross-disciplinary collaborations that assess drone impact across various species and ecological settings, with the aim of creating community-wide or ecosystem-specific guidelines.

5.1.3. Ethical and Conservation Considerations

The ethical implications of using drones in wildlife habitats demand careful consideration. Prolonged exposure to drone noise, particularly in high-use tourist areas, can lead to chronic stress responses in wildlife, potentially affecting health, reproductive success, and habitat use. This is especially relevant in protected or sensitive areas where conservation goals prioritize minimal human intrusion.

Future Research Need: Ethical frameworks and noise-reduction strategies should be developed in collaboration with conservation stakeholders. This includes establishing drone-free zones and limits on drone activity in ecologically sensitive areas.

Proposed Approach: Introduce ethical guidelines for drone operations that prioritize non-invasive practices, such as silent or biomimetic drones, and establish regulatory standards to protect critical habitats from drone disturbances.

5.1.4. Technological Constraints in Noise and Flight Precision

Current drone technology poses inherent limitations in minimizing auditory and visual disturbances, particularly with noise levels in multirotor drones and flight precision needed for close-range monitoring. Noise pollution is an ongoing challenge, with varying impacts on species depending on their hearing range, habitat, and exposure to other anthropogenic sounds.

Future Research Need: Invest in research on quieter propulsion systems and adaptive flight algorithms that reduce noise and increase precision.

Proposed Approach: Develop quieter, eco-friendly drones specifically designed for wildlife research, with emphasis on noise suppression technologies and improved flight control to avoid rapid movements that may startle animals.

5.2. Future Research Directions

Moving forward, several additional areas warrant attention for the advancement of ethical drone-assisted wildlife conservation. The following recommendations outline future directions to enhance the effectiveness and ethical considerations of drone use in this domain.

5.2.1. Innovations in Drone Technology

As we advance in ethical drone use for wildlife conservation, there is an increasing emphasis on continuous innovation. Future advancements in drone technology should prioritize the development of quieter propulsion systems, adaptive flight algorithms that minimize disturbances, and specialized sensors that enhance data collection while reducing impact on wildlife.

Collaborations among engineers, biologists, and conservationists will be crucial in pushing the boundaries of drone design and tailoring future models to minimize ecological footprints. Additionally, the adoption of drone swarms presents significant potential for wildlife monitoring, enabling the collection of high-quality, multi-perspective data across vast areas. However, the real-world deployment of these systems remains limited due to a lack of automated solutions capable of ensuring synchronization and coordination in diverse environments.

Similarly, the development of swarm or multi-drone systems highlights the potential of coordinated intelligence to overcome challenges associated with single-drone limitations [

114]. The implementation of autonomous multi-drone missions could revolutionize wildlife research by increasing efficiency and reducing the need for human presence in sensitive habitats. To achieve this, further research into automated control systems that enhance cooperation between drones is essential. This will enable real-time data collection and monitoring of social species, particularly in areas where human intervention might disrupt animal behavior [

115,

116].

5.2.2. Tailoring Guidelines for Diverse Ecosystems

Recognizing ecosystem diversity, future efforts in drone-assisted wildlife conservation should concentrate on crafting guidelines tailored to the specific needs of aerial, terrestrial, and aquatic environments. While it is impossible to test every habitat or species, a practical approach would be to focus on representative species, communities, or habitat types that capture a broad range of behavioral responses. Modeling based on these representative groups can help create adaptable frameworks, allowing for generalizable guidelines that can be refined for specific cases. Recommendations must account for unique sensitivities within each habitat, suggesting altitude and noise thresholds that respect wildlife behavioral intricacies and acoustic requirements. A nuanced approach to guidelines ensures adaptability across diverse ecosystems.

5.2.3. Global Collaboration and Standardization

The envisioned path forward emphasizes fostering global collaboration and standardization in ethical drone use for wildlife conservation. Cross-disciplinary partnerships among researchers, conservationists, and policymakers are crucial for sharing best practices, harmonizing ethical standards, and establishing a framework for responsible drone-assisted wildlife monitoring globally. Standardization guarantees consistent prioritization of ethical considerations, irrespective of geographic location or ecosystem type.

5.2.4. Development of Testing Standards for Drones

Shaping the future of ethical wildlife monitoring requires establishing testing standards for drones. Rigorous assessments of noise levels, flight altitudes, and impact on animal behavior should be part of a standardized testing framework, ensuring adherence to predefined ethical criteria and fostering accountability in wildlife conservation practices. Recent advancements in drone technology [

117] hold promise for biologists, offering tools to better assess the real-time effects of drones on animals in the wild. For instance, software such as the newly developed WildBridge [

118], which provides real-time camera feeds and telemetry data on any external interface, can track drone proximity to targets, enabling a more accurate and immediate assessment of animal reactions to the drone. Biomimicry concepts could also be explored in testing protocols to evaluate the drone’s ability to minimize disturbance by drawing inspiration from natural behaviors observed in wildlife.

6. Conclusions

The increasing utilization of drones in wildlife research has provided significant advancements in data collection, remote monitoring, and conservation efforts. However, this review highlights the substantial challenges associated with drone-induced disturbances on wildlife, emphasizing the necessity of evidence-based operational protocols to mitigate potential adverse effects. The impact of drones varies considerably across species and habitats, influenced by factors such as flight altitude, speed, proximity, noise levels, and species-specific sensitivities. While short-term behavioral and physiological responses to drone disturbances are well documented, the long-term ecological consequences remain insufficiently explored.

A synthesis of the existing literature underscores the critical importance of implementing standardized operational guidelines to ensure the ethical and responsible use of drones in wildlife research. Flight altitude, trajectory, and approach methodologies must be carefully optimized to reduce stress-induced responses while maintaining the integrity of ecological studies. Additionally, future research should focus on longitudinal assessments to evaluate the cumulative effects of drone exposure on wildlife behavior, reproductive success, and habitat use. Advancements in drone technology, including noise reduction mechanisms and biologically informed designs, may further enhance the potential for non-invasive aerial data collection.

Given the interdisciplinary nature of this field, collaboration among ecologists, engineers, conservationists, and regulatory bodies is imperative to develop species-specific guidelines that balance research objectives with wildlife welfare. Ethical considerations must remain central to the development of best practices, ensuring that technological innovation does not compromise ecological integrity. Addressing these challenges requires a concerted effort to refine drone applications in wildlife research, ultimately supporting conservation initiatives while minimizing anthropogenic disturbances. Future studies should prioritize standardized risk assessments and regulatory frameworks to ensure the sustainable integration of drones into ecological research and biodiversity conservation.

Acknowledgement

This work is supported by the WildDrone MSCA Doctoral Network funded by EU Horizon Europe under grant agreement no. 101071224, and the U.S. National Science Foundation under the Imageomics Institute (OAC-2118240), and the ICICLE Institute (OAC-2112606)

References

- Geoghegan, J.L.; Pirotta, V.; Harvey, E.; Smith, A.; Buchmann, J.P.; Ostrowski, M.; Eden, J.S.; Harcourt, R.; Holmes, E.C. Virological Sampling of Inaccessible Wildlife with Drones. Viruses 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, J.D.; Lemos, L.; Barlow, D.; Wing, M.G.; Chandler, T.; Torres, L.G. Estimating morphometric attributes of baleen whales with photogrammetry from small UASs: A case study with blue and gray whales. Marine Mammal Science 2019, 35, 108–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graving, J.M.; Chae, D.; Naik, H.; Li, L.; Koger, B.; Costelloe, B.R.; Couzin, I.D. DeepPoseKit, a software toolkit for fast and robust animal pose estimation using deep learning. eLife 2019, 8, e47994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, G.; Yang, H.; Pan, R.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, P.; Wang, J.; Jin, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Guo, S. Using unmanned aerial vehicles with thermal-image acquisition cameras for animal surveys: a case study on the Sichuan snub-nosed monkey in the Qinling Mountains. Integrative Zoology 2020, 15, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linchant, J.; Lhoest, S.; Quevauvillers, S.; Lejeune, P.; Vermeulen, C.; Semeki Ngabinzeke, J.; Luse Belanganayi, B.; Delvingt, W.; Bouché, P. UAS imagery reveals new survey opportunities for counting hippos. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulero-Pázmány, M.; Stolper, R.; Van Essen, L.; Negro, J.J.; Sassen, T. Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems as a Rhinoceros Anti-Poaching Tool in Africa. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szantoi, Z.; Smith, S.E.; Strona, G.; Koh, L.P.; Wich, S.A. Mapping orangutan habitat and agricultural areas using Landsat OLI imagery augmented with unmanned aircraft system aerial photography. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2017, 38, 2231–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, L.; Martinez, E.; Bader, M.K.F.; Orams, M.B.; Bollard, B. Insights into the use of an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) to investigate the behavior of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in Vava’u, Kingdom of Tonga. Marine Mammal Science 2020, 36, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, P.C.; Fleishman, A.B.; Klein, D.J.; McKown, M.W.; Bézy, V.S.; Lohmann, K.J.; Johnston, D.W. A convolutional neural network for detecting sea turtles in drone imagery. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2019, 10, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colefax, A.P.; Butcher, P.A.; Pagendam, D.E.; Kelaher, B.P. Reliability of marine faunal detections in drone-based monitoring. Ocean & Coastal Management 2019, 174, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebolo-Ifrán, N.; Grilli, M.G.; Lambertucci, S.A. Drones as a Threat to Wildlife: YouTube Complements Science in Providing Evidence about Their Effect. Environmental Conservation 2019, 46, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly Baltrus. Drone harasses bighorn sheep at Zion National Park. https://www.nps.gov/zion/-learn/news/droneharassesbhs.htm. accessed Dec., 2014.

- Mesquita, G.P.; Mulero-Pázmány, M.; Wich, S.A.; Rodríguez-Teijeiro, J.D. Terrestrial Megafauna Response to Drone Noise Levels in Ex Situ Areas. Drones 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, A.B.; Butcher, P.A.; Colefax, A.P.; Pagendam, D.E.; Mayjor, M.; Kelaher, B.P. Responses of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops spp.) to small drones. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 2021, 31, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, R. Drones Flying High as New Tool for Field Biologists. Science 2014, 344, 459–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.E.; Sykora-Bodie, S.T.; Bloodworth, B.; Pack, S.M.; Spradlin, T.R.; LeBoeuf, N.R. Assessment of known impacts of unmanned aerial systems (UAS) on marine mammals: data gaps and recommendations for researchers in the United States. Journal of Unmanned Vehicle Systems 2016, 4, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, M.A.; O’Brien, C.; Kostoglou, K.N.; Symonds, M.R.E. Escape responses of terrestrial and aquatic birds to drones: Towards a code of practice to minimize disturbance. Journal of Applied Ecology 2020, 57, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vas, E.; Lescroël, A.; Duriez, O.; Boguszewski, G.; Grémillet, D. Approaching birds with drones: first experiments and ethical guidelines. Biology Letters 2015, 11, 20140754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech-Hansen, M.; Kallehauge, R.; Lauritzen, J.; Sørensen, M.; Laubek, B.; Jensen, L.; Pertoldi, C.; Bruhn, D. Evaluation of disturbance effect on geese caused by an approaching unmanned aerial vehicle. Bird Conservation International 2020, 30, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rümmler, M.C.; Mustafa, O.; Maercker, J.; Peter, H.U.; Esefeld, J. Sensitivity of Adélie and Gentoo penguins to various flight activities of a micro UAV. Polar Biology 2018, 41, 2481–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbe, C.; Dent, M.L.; Gannon, W.L.; McCauley, R.D.; Römer, H.; Southall, B.L.; Stansbury, A.L.; Stoeger, A.S.; Thomas, J.A. , C.; Thomas, J.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 459–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97540-1_13.Animals. In Exploring Animal Behavior Through Sound: Volume 1: Methods; Erbe, C., Thomas, J.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 459–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scobie, C.A.; Hugenholtz, C.H. Wildlife monitoring with unmanned aerial vehicles: Quantifying distance to auditory detection. Wildlife Society Bulletin 2016, 40, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, G.P.; Rodríguez-Teijeiro, J.D.; Wich, S.A.; Mulero-Pázmány, M. Measuring disturbance at swift breeding colonies due to the visual aspects of a drone: a quasi-experiment study. Current Zoology 2020, 67, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, S.; Hlebowicz, K.; Cawthorne, D.; Lundquist, U.P.S. Unveiling the Impact of Drone Noise on Wildlife: A Crucial Research Imperative. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS); 2024; pp. 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caughley, G. Bias in Aerial Survey. The Journal of Wildlife Management 1974, 38, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, D.E.; Rongstad, O.J.; Mytton, W.R. Response of Nesting Red-Tailed Hawks to Helicopter Overflights. The Condor 1989, 91, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patenaude, N.J.; Richardson, W.J.; Smultea, M.A.; Koski, W.R.; Miller, G.W.; Würsig, B.; GReene JR., C. R. Aircraft sound and sisturbance to bowhead and beluga whalees during spring migration in the Alaskan Beaufort sea. Marine Mammal Science 2002, 18, 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi-Fitzpatrick, A.; Chavarria, D.; Cychosz, E.; Dingens, J.; Duffey, M.; Koebel, K.; Siriphanh, S.; Tulen, M.; Watanabe, H.; Juskauskas, T.; et al. Up in the Air: A Global Estimate of Non-Military Drone Use: 2009-2015 2016.

- Sky Watch. The Sky-Watch Way: Empowering Innovation in UAS Solutions. https://www.sky-watch.com/. accessed Dec., 2024.

- Yuneec. Drones: H850 RTK. http://yuneec.uk/. accessed Dec., 2024.

- Avy Drone. Avy: The ultimate BVLOS & VTOL drone for emergencies. https://avy.eu/. accessed Dec., 2024.

- Airborne Drones. Drones noise level. https://www.airbornedrones.co/drone-noise-levels/. accessed Dec., 2024.

- Dundas, S.J.; Vardanega, M.; O’Brien, P.; McLeod, S.R. Quantifying Waterfowl Numbers: Comparison of Drone and Ground-Based Survey Methods for Surveying Waterfowl on Artificial Waterbodies. Drones 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimerskirch, H.; Prudor, A.; Schull, Q. Flights of drones over sub-Antarctic seabirds show species-and status-specific behavioural and physiological responses. Polar Biology 2018, 41, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, E.; Bolin, J.; Leon, J.; Burnett, S. Fright or Flight? Behavioural Responses of Kangaroos to Drone-Based Monitoring. Drones 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennitt, E.; Bartlam-Brooks, H.L.; Hubel, T.Y.; Wilson, A.M. Terrestrial mammalian wildlife responses to Unmanned Aerial Systems approaches. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G. Fleeing by Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus<) in response to a recreational drone in Maputo Bay, Mozambique. Biodiversity Observations 2016, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Arona, L.; Dale, J.; Heaslip, S.G.; Hammill, M.O.; Johnston, D.W. Assessing the disturbance potential of small unoccupied aircraft systems (UAS) on gray seals (Halichoerus grypus) at breeding colonies in Nova Scotia, Canada. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, W.L.; Fishlock, V.; Leslie, A. First guidelines and suggested best protocol for surveying African elephants (Loxodonta africana) using a drone. koedoe 2021, 63, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, V.; Xu, F.; Turghan, M.A. Przewalski’s Horses (Equus ferus przewalskii) Responses to Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Flights under Semireserve Conditions: Conservation Implication. International Journal of Zoology 2021, 2021, 6687505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiano, S. Dolphin Behavioral Responses to Uncrewed Aerial Systems as a Function of Exposure, Height, and Type. Master’s thesis, Stephen F Austin State University, 2023.

- Aubin, J.A.; Mikus, M.A.; Michaud, R.; Mennill, D.; Vergara, V. Fly with care: belugas show evasive responses to low altitude drone flights. Marine Mammal Science 2023, 39, 718–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orange, J.P.; Bielefeld, R.R.; Cox, W.A.; Sylvia, A.L. Impacts of Drone Flight Altitude on Behaviors and Species Identification of Marsh Birds in Florida. Drones 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepien, E.N.; Khan, J.; Galatius, A.; Teilmann, J. How low can you go? Exploring impact of drones on haul out behaviour of harbour-and grey seals. Frontiers in Marine Science 2024, 11, 1411292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, L.M.; Peacock, M.F.; Yunker, M.P.; Madsen, C.J. Bottle-Nosed Dolphin: Double-Slit Pupil Yields Equivalent Aerial and Underwater Diurnal Acuity. Science 1975, 189, 650–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G.B.; Colbert, D.E.; Gaspard, J.C.; Littlefield, B.L.; Fellner, W. Underwater Visual Acuity of Florida Manatees (Trichechus manatus latirostris). International Journal of Comparative Psychology 2003, p. 130–142. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, E.A.; Maloney, B.; Magnasco, M.O.; Reiss, D. Bottlenose Dolphins and Antillean Manatees Respond to Small Multi-Rotor Unmanned Aerial Systems. Frontiers in Marine Science 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, C.J.; Croze, H.; Lee, P.C. The Amboseli elephants: a long-term perspective on a long-lived mammal; University of Chicago Press, 2011.

- Penny, S.G.; White, R.L.; Scott, D.M.; MacTavish, L.; Pernetta, A.P. Using drones and sirens to elicit avoidance behaviour in white rhinoceros as an anti-poaching tactic. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2019, 286, 20191135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duporge, I.; Spiegel, M.P.; Thomson, E.R.; Chapman, T.; Lamberth, C.; Pond, C.; Macdonald, D.W.; Wang, T.; Klinck, H. Determination of optimal flight altitude to minimise acoustic drone disturbance to wildlife using species audiograms. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2021, 12, 2196–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, R.M. Walker’s Mammals of the World; Vol. 1, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

- Egan, C.C.; Blackwell, B.F.; Fernández-Juricic, E.; Klug, P.E. Testing a key assumption of using drones as frightening devices: Do birds perceive drones as risky? The Condor 2020, 122, duaa014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Griffin, A.S.; Lucas, A.; Wong, K. Psychological warfare in vineyard: Using drones and bird psychology to control bird damage to wine grapes. Crop Protection 2019, 120, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storms, R.F.; Carere, C.; Musters, R.; van Gasteren, H.; Verhulst, S.; Hemelrijk, C.K. Deterrence of birds with an artificial predator, the RobotFalcon. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2022, 19, 20220497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEvoy, J.F.; Hall, G.P.; McDonald, P.G. Evaluation of unmanned aerial vehicle shape, flight path and camera type for waterfowl surveys: disturbance effects and species recognition. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, M.; Hildenbrandt, H.; Sankey, D.W.E.; Portugal, S.J.; Hemelrijk, C.K. Self-organization of collective escape in pigeon flocks. PLOS Computational Biology 2022, 18, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, J.K.; Burchfield, D. Evaluation of unmanned aerial vehicles for surveys of lek-mating grouse. Wildlife Society Bulletin 2022, 46, e1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, D.H.; Patten, M.A.; Shochat, E.; Pruett, C.L.; Sherrod, S.K. Causes and Patterns of Mortality in Lesser Prairie-chickens Tympanuchus pallidicinctus and Implications for Management. Wildlife Biology 2007, 13, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisson-Curadeau, É.; Bird, D.; Burke, C.; Fifield, D.A.; Pace, P.; Sherley, R.B.; Elliott, K.H. Seabird species vary in behavioural response to drone census. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 17884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- News, A. Video: Raven attacks drone delivering coffee.

- Frouin-Mouy, H.; Tenorio-Hallé, L.; Thode, A.; Swartz, S.; Urbán, J. Using two drones to simultaneously monitor visual and acoustic behaviour of gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) in Baja California, Mexico. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 2020, 525, 151321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duporge, I.; Spiegel, M.P.; Thomson, E.R.; Chapman, T.; Lamberth, C.; Pond, C.; Macdonald, D.W.; Wang, T.; Klinck, H. Determination of optimal flight altitude to minimise acoustic drone disturbance to wildlife using species audiograms. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2021, 12, 2196–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headland, T.; Ostendorf, B.; Taggart, D. The behavioral responses of a nocturnal burrowing marsupial (Lasiorhinus latifrons) to drone flight. Ecology and Evolution 2021, 11, 12173–12181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macke, E.N.; Jones, L.R.; Iglay, R.B.; Elmore, J.A. Drone noise differs by flight maneuver and model: implications for animal surveys. Drone Systems and Applications 2024, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headland, T.; Ostendorf, B.; Taggart, D. The behavioral responses of a nocturnal burrowing marsupial (Lasiorhinus latifrons) to drone flight. Ecology and Evolution 2021, 11, 12173–12181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, C.M. Absorption of sound in air versus humidity and temperature. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1966, 40, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino-González, A.; Kovacs, K.M.; Lydersen, C.; Ims, R.A.; Lowther, A.D. Drones and marine mammals in Svalbard, Norway. Marine Mammal Science 2021, 37, 1212–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, M.; Atzeni, L.; Lovari, S.; Nasanbat, B.; Ravchig, S.; Herrador, F.C.; Bombieri, G.; Augugliaro, C. Spatiotemporal behavior of predators and prey in an arid environment of Central Asia. Current Zoology 2023, 69, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisser, E.L.; Bolnick, D.I.; Benard, M.F. Scared to death? The effects of intimidation and consumption in predator–prey interactions. Ecology 2005, 86, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.S.; Laundré, J.W.; Gurung, M. The ecology of fear: optimal foraging, game theory, and trophic interactions. Journal of mammalogy 1999, 80, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, N.M.; Panebianco, A.; Gonzalez Musso, R.; Carmanchahi, P. An experimental approach to evaluate the potential of drones in terrestrial mammal research: a gregarious ungulate as a study model. Royal Society Open Science 2020, 7, 191482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleón, M.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A.; Donázar, J.A.; Revilla, E.; Martín-López, B.; Gutiérrez-Cánovas, C.; Getz, W.M.; Morales-Reyes, Z.; Campos-Arceiz, A.; Crowder, L.B.; et al. Rethinking megafauna. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2020, 287, 20192643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennitt, E.; Bartlam-Brooks, H.L.; Hubel, T.Y.; Wilson, A.M. Terrestrial mammalian wildlife responses to Unmanned Aerial Systems approaches. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, A.B.; Butcher, P.A.; Colefax, A.P.; Pagendam, D.E.; Mayjor, M.; Kelaher, B.P. Responses of bottlenose dolphins ( spp.) to small drones. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 2021, 31, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vanVuuren, M.; vanVuuren, R.; Silverberg, L.M.; Manning, J.; Pacifici, K.; Dorgeloh, W.; Campbell, J. Ungulate responses and habituation to unmanned aerial vehicles in Africa’s savanna. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, E.; Raoult, V.; Williamson, J.E.; Gaston, T.F. Estuary Stingray (Dasyatis fluviorum) Behaviour Does Not Change in Response to Drone Altitude. Drones 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, J.; Borges, F.O.; Cid, A.; Laborde, M.I.; Rosa, R.; Pearson, H.C. Assessing the Behavioural Responses of Small Cetaceans to Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Remote Sensing 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, N.M.; Panebianco, A. Sociability strongly affects the behavioural responses of wild guanacos to drones. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 20901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditmer, M.A.; Vincent, J.B.; Werden, L.K.; Tanner, J.C.; Laske, T.G.; Iaizzo, P.A.; Garshelis, D.L.; Fieberg, J.R. Bears Show a Physiological but Limited Behavioral Response to Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Current biology : CB 2015, 25, 2278–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, J.R.; Green, M.C.; DeMaso, S.J.; Hardy, T.B. Drone surveys do not increase colony-wide flight behaviour at waterbird nesting sites, but sensitivity varies among species. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koski, W.R.; Gamage, G.; Davis, A.R.; Mathews, T.; LeBlanc, B.; Ferguson, S.H. Evaluation of UAS for photographic re-identification of bowhead whales, Balaena mysticetus. Journal of Unmanned Vehicle Systems 2015, 3, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]