1. Introduction

The cornea is the most sensitive organ in the entire organism, and this is due to the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve that “dresses” the cornea in a dense network of nerve threads. Corneal innervation is indispensable in maintaining the homeostasis of the ocular surface. It not only plays a crucial role in the blinking and lacrimal reflex but also releases numerous trophic substances necessary for epithelial cell proliferation. Therefore, alteration of the innervation leads to epithelial breakdown with the appearance of neurotrophic keratopathy (NK). Neurotrophic keratopathy is considered a rare pathology with an average prevalence of 5/10.000 and is caused by trigeminal nerve injury anywhere on its route, preganglionic, postganglionic, and ocular surface injuries. The etiologies are various, ocular or systemic: viral herpetic infection, malignancy, surgery, or corneal injury [

1].

In the current clinical practice, there is only conventional treatment for NK, focused only on preventing continuous corneal degradation and not on the underlying cause of the disease. Therefore, in most cases, corneal disease is just partially controlled. New medical treatments, like nerve growth factors, have been studied in recent years. Cenegermin, a recombinant human nerve growth factor, has been approved for the treatment of NK, but the very high cost limits its use in current practice. It has proven its effectiveness by stimulating epithelial healing. Some authors declared that it also improved corneal sensitivity, but more interventional studies are needed [

2,

3,

4].

Corneal neurotization remains the only intervention that can restore corneal innervation and ocular homeostasis. It was described for the first time in 1972 by Samii but was not practicable due to the high complexity and lack of benefits. In recent years, several variants of corneal neurotization have been described, trying to create a more accessible version in current practice. Terzis introduced the concept of direct neurotization in 2009 [

5], and Borchel`s group, in 2014 [

6] used sural nerve graft coapted end-to-side to the contralateral supratrochlear nerve.

Surgical Procedure

Through neurotization, a connection is created between the denervated cornea and vital branches of the ipsilateral or contralateral trigeminal nerve. Currently, several variants of this intervention exist. They are divided into two large classes, direct neurotization, and indirect neurotization, from more invasive variants to newer endoscopic techniques, all having the same goal, restoring corneal sensitivity. Direct neurotization (DNT) technique involves the transposition of the ipsilateral or contralateral supratrochlear/ supraorbital nerves to the denervated cornea. Indirect neurotization (INT) requires the interposing of a nerve graft between the supraorbital/ supratrochlear nerves and the denervated cornea. The preferred nerve graft for neurotization is sural nerve, but greater auricular nerve or acellular nerve graft have also been described. [

7,

8,

9,

10]. For INT, a length of 10-15 cm is required for the grafted nerve.[

11]

However, corneal neurotization remains a complex technique that requires a multidisciplinary approach and a steep learning curve, but its promising results and further refinement will lead to a growing interest in this intervention. The aim of this scoping review is to gather the relevant scientific reports in the last decade, systematizing the concepts regarding the procedure and comparing the surgical outcome from different techniques.

2. Materials and Methods

In this review we examined the recently published data regarding surgical procedures and clinical outcomes for corneal neurotization, performed by surgeons with good experience in this procedure. Therefore, only publications investigating at least three patients were included.

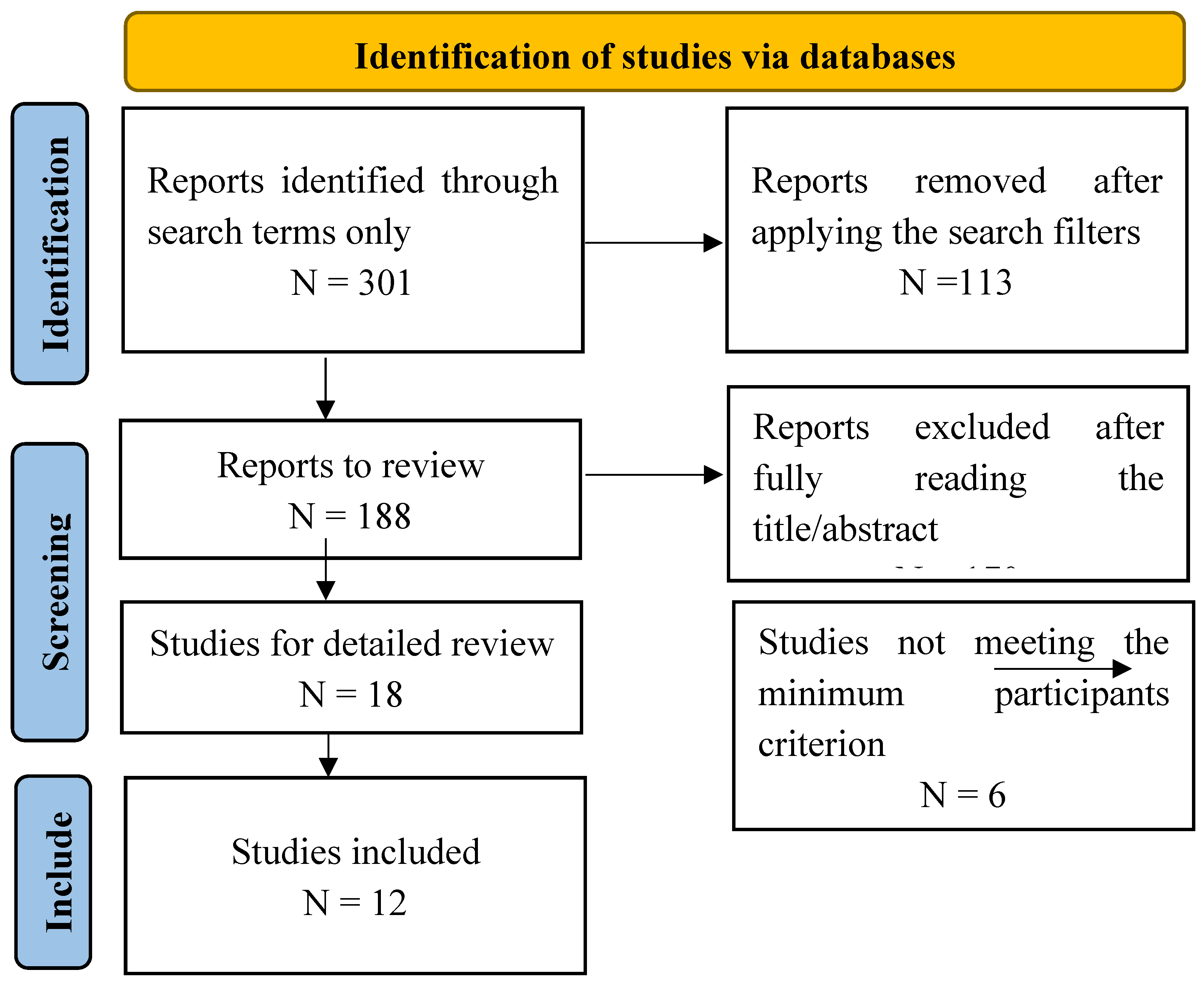

The review was prepared following PRISMA guidelines. The studies were searched on PubMed and Google Scholar with the terms “corneal neurotization” or “corneal reinnervation” (last date of search – January 2025, reviewers S.O. and P.L.). 301 results were found, starting 1961. Most of the reports appeared, however, after the year 2017. Inclusion criteria were date of publication between 2017 and 2024, full text available, English or French language, human subjects, at least three patients followed. Abstracts, congress communications and other articles without full text availability were excluded (

Figure 1).

We observed the demographic parameters, surgical procedures, anatomical outcomes – corneal healing, in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM), and functional outcomes – central corneal sensibility (CCS), best corrected visual acuity (BCVA).

3. Results

Twelve studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review, published between 2018-2023 (

Table 1). All patients were diagnosed with NK with reduced or abolished corneal sensation on Cochet–Bonnet aesthesiometer (CBA) before surgery (except for one study [

12] in which corneal sensitivity was tested only qualitatively). Cochet-Bonet esthesiometer determines central corneal sensation, with a scale from 0 mm (no sensation) to 60 mm (full sensation).

The most reported causes of neurotrophic keratopathy were trigeminal lesions secondary to tumors, intracranial interventions, craniocerebral injuries, herpetic keratitis, and congenital causes mainly described in children. Less frequent were cases of neurotrophic keratopathy secondary to repeated eye interventions or idiopathic cases.

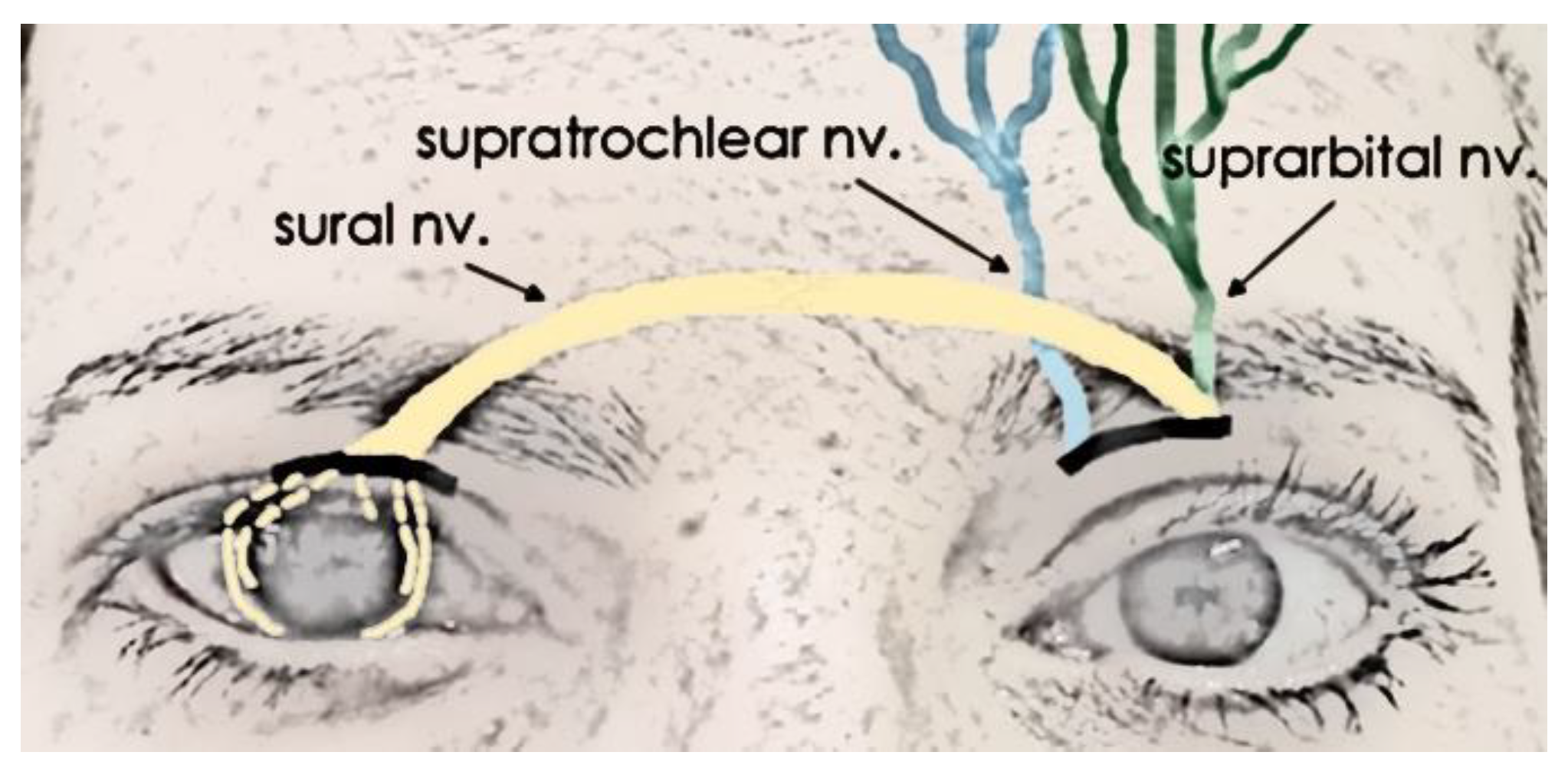

There was a total of 164 eyes that underwent neurotization. Most of the cases received INT (127eyes). Sural nerve (or other grafts: acellular nerve allograft [

9,

10]) was attached to supratrochlear or supraorbital nerve (more rarely to infraorbital nerve), with an end-to-end procedure (mainly) or end-to-side (Sweeney et al., 35% of the cases [

9]). A schematic of the intervention is represented in

Figure 2. 37 cases received DNT, where contralateral intact supraorbital or supratrochlear nerve was distributed to the damaged cornea (ipsilateral nerves can also be used, if they are intact, observed mainly in Catapano et al., or Lin et al. [

13,

14]). In both methods, the nerve graft was tunneled into the conjunctival space of the affected eye, the fascicles were separated and attached either perilimbal or into the peripheral corneal stroma via a corneoscleral tunnel incision. Multiple fascicles were implanted around the cornea, in all the quadrants (usually 4 to 6 fascicles). A temporal central tarsorrhaphy was sometimes necessary. Amniotic membrane was used sometimes, over the cornea or wrapping the anastomosis, with the argument that this may assist with nerve regeneration owing to the high levels of neurotrophic growth factors [

15].

Neurotization is a complicated procedure. Elalfy et al. [

16] estimated a surgical time of 5 hours for the very first procedures performed by the team, gradually reduced to 3 hours once two surgeons performed sural nerve harvest and eye preparation procedures simultaneously. They also noticed improvements in ocular surface and tear film stability (break-up time, Schirmer, corneal staining). Only 5 patients were analyzed with IVCM, with nerve parameters improved at 3 months, but no further improvement later, up to 12 months. Subjective corneal sensation appeared earliest at 1.5 months, and latest in a patient at 18 months.

Fogagnolo et al. [

17] compared DNT (16 cases) to ITN (10 cases) in a multicenter prospective study. No differences in CCS were observed, between groups, at 12 months (a faster recovery time was seen in DNT, CCS being statistically better at 3 and 6 months). All NKs healed after a mean period of 3.9 months (2-6 months). However, 3 patients did not regain corneal sensitivity. SCP was normal at 12 months, on IVCM. While no major complication was observed, all patients that underwent DNT had mild face oedema, and all with INT had oedema of the upper third of the face. Numbness at the harvesting site subsided after 12 months. Misperception of the corneal sensitivity at the harvesting site was common in the first 3-6 months after surgery.

Catapano et al. [

13] investigated mostly pediatric cases (mean age 12.5±8.3). Congenital cornea anesthesia was the main cause for NK and 26% patients developed amblyopia. They also investigated the difference in corneal sensibility when the nerve fascicles were inserted perilimbal, versus corneoscleral tunnels, observing a better, yet without statistical significance outcome in the latter group (2.5±6.1 mm, versus 19.4±23.1 mm, p<0.08). 87% achieved ≥40 mm central corneal sensibility and 64% achieved full sensibility. Four patients developed PED, only after PK, all of them having maximum CCS. PEDs were successfully treated in 4 weeks with lubricants and a bandage contact lens. Woo et al. [

18] included also pediatric cases (17 patients out of 23). CCS improved to near normal in more than 60% of the eyes. The first sensation appeared at 3 months, and the maximum was achieved at 11.1 months, on average. Younger patients experienced more recurrent epithelial breakdown (mean age 10.9), the authors suggesting reduced awareness and increased propensity to injuries in children.

Weis et al. [

12] claims to be the first study to present a series of adult patients with NT. All 6 patients regained corneal sensation in the first 6 months. All ulcers healed and the epithelium remained stable.

Anatomical improvements were also assessed with IVCM, regarding corneal nerve density. In Gianacarre et al. [

19] corneal sub-basal nerve plexus (SNP) was absent in all preoperatively, appeared at 3 months, and became comparable to normal eye by 12 months. IVCM quantified corneal nerve branch density, corneal nerve fiber length, corneal nerve total branch density, corneal nerve fiber area, corneal nerve fiber width, and corneal nerve fractal dimension. All parameters improved, beginning with the 3-month scan, and all but two parameters (corneal nerve fiber withs and fractal dimension) increased progressively until the end of follow-up, at 12 months. They also reported significant improvements in tear film function following corneal neurotization as evidenced by the Schirmer test and tear breakup time (TBUT). The mean Schirmer test score increased from 3.0 mm/5 minutes (± 0.81) preoperatively to 7.66 mm/5 minutes (± 1.24) postoperatively, while the TBUT improved from 2.6 seconds (± 0.47) to 6.0 seconds (± 0.81).

Leyngold et al. [

10] observed peripheral improvement in corneal sensibility in all 7 eyes, while central improvement was reported in 5. The focus in this study was, however, the successful use of processed acellular nerve allograft (Avance Nerve Graft, processed human nerve allograft intended for the surgical repair of peripheral nerve discontinuities). Acellular allograft seems to have the same outcomes as autograft and additionally, simplifies the procedure [

9,

10]. However, more experimental studies with higher sample sizes are needed. Sweeney et al. [

9] didn`t notice any differences in CCS between end-to-end coaptations (11 cases) versus end-to-side (6 cases) coaptation techniques (52 mm versus 60 mm max CCS).

Wisely et al. [

20] reported the first successful corneal neurotization performed simultaneously with PK. Corneal sensation appeared at 4 months (corneal irritation), and an objective improvement was noticed at 4.5 months.

All patients in Lin et al. [

14] study were postherpetic NK. The procedure was well tolerated with no intraoperative complications. The best corrected visual acuity remained stable, dependent on corneal scaring usually seen in NK caused by ocular injuries, with further improvements expected after PK.

Su D et al. [

21] noticed full epithelium recovery at 12 months and nerve regeneration present at 6 months, on average, with maximum regeneration between 12-18 months. However, they observed a time difference between corneal nerve recovery and corneal sensation recovery. Corneal nerve fiber density recovered earlier (at 12 months) than corneal nerve branch density (at 18 months), the latter being better corelated (p<0.05) with corneal sensation recovery. They evaluated and compared the recovery of central and peripheral sub-basal corneal nerve fiber density (CNFD) following NT surgery. While both regions experienced significant improvements over 24 months, no statistically significant differences were observed between the central and peripheral CNFD values (P > 0.05). Most, not all patients recovered corneal sensation, but the numbers are not specified.

4. Discussion

Almost all the patients included in the review had corneal sensation improvement assessed by Cochet–Bonnet aesthesiometer. The rate of success for either DNT or INT could be estimated at about 90% (range between 60.7% and 100%). Studies with both variants of neurotization described have found no significant difference between the postoperative outcomes of the two groups (Fogagnolo et al. [

17]).

Indirect neurotization with a sural nerve graft was the preferred procedure, applied to 63% of all eyes. Acellular allograft could replace the sural nerve and seems to have the same outcomes as autograft and additionally, simplifies the procedure. (Sweeney et al., Leyngold et al., 24 eyes in total [

9,

10]). However, more experimental studies with higher sample sizes are needed.

The cause of NK did not seem to influence the outcome of the surgery, regarding corneal sensation and stability. Pediatric cases, with congenital anesthesia of the cornea, or adult cases, with causes ranging from intracranial surgeries to herpetic keratitis, all had similar outcomes [

13]. Visual acuity did not always recover, but usually remained at least stable, with no further deterioration. The variability of visual acuity was mainly corelated to corneal scars in long lasting NK, improvements being expected after PK. Therefore, corneal neurotization should be performed in the early stages of neurotrophic keratopathy before these changes appear. Amblyopia was another concern in small children. Catapano et al. [

13] added other reasons for the variability, including patient selection, surgical technique, disease duration and structural integrity of the cornea.

Preoperatory CCS on CBA was 2.717 mm (averaged from the 10 articles reporting the parameter; range 0-9.2 mm) and significantly improved after the surgery, at 36.01 mm (range 21.1-49.7 mm). Corneal sensation appeared within 4.12 months, on average (7 studies reported accurately this parameter; range 3-6 months), and reached maximum at 12 months (apart from Sweeney et al., who reported maximum sensitivity at 6.6 months).

Catapano et al [

13] noticed that cases with fascicles inserted into corneoscleral tunnels had more corneal sensation at early follow-up compared to those where fascicles were tunneled into the subconjunctival space. Woo et al. [

18] described that chronic denervation and a contralateral donor may be a cause of delayed recovery after neurotization, but at the last follow-up, there were no significant differences compared to the control group. They also have found that the number of fascicles and insertions is negatively correlated with the results of reinnervation. The number of fascicles used in the studies included here were 4-8.

Some studies used in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM) to analyze corneal nerves. They showed significant improvement in nerve parameters after NT [

10,

14,

16,

17,

20]. Su D et al. [

21] identified a temporal difference between the recovery of corneal nerve density and corneal sensation, highlighting the correlation between these factors. By analyzing patients with significant recovery at 24 months postoperatively, it was found that central and peripheral CNFD showed substantial recovery by 12 months, with continued improvement in peripheral nerves due to their thinness, as evidenced by IVCM images. Objective evidence of corneal sensation and reinnervation after neurotization could also be provided by MEG [

13].

After corneal neurotization, there were cases where epithelial healing was present but not the corneal sensitivity. This was explained by the fact that nerve growth factors could provide protective trophic support to the cornea, independent of corneal sensations [

16,

17].

Giannaccare et al. [

19] demonstrated increased tear film stability (Schirmer test and TBUT), highlighting the overall enhancement in ocular surface health and tear film stability post-surgery. Lacrimal secretion was tested and a significant increase in tear production was noticed after cornea neurotization [

15].

Neurotization was a safe procedure, with no intraoperative complications reported. Numbness at the donor site usually subsided within 1 year [

10,

16,

20]. One study reported misperception of sensitivity at the harvested site, for the first 3-6 months [

16].

Future Perspectives

Corneal neurotization seems a well-established procedure in case of loss of corneal sensibility. No serious complications and high success rate mean that the procedure is safe and could become the first choice of treatment in NK. However, we still lack enough data, as relatively low numbers of patients received treatment so far. The procedure is relatively new, being better described only in the last 15 years. Some refinements of the procedure already exist, with the possibility of replacement of sural nerve by acellular nerve in INT or increased use of amniotic membrane at the corneal site.

Outcome measurement is another problem that surgeons face. IVCM is not easily available, and CBA has some degree of subjectiveness. Pain in the end is a subjective feeling, so improvement in sensitivity scoring may benefit only the scientific community and not the patient.

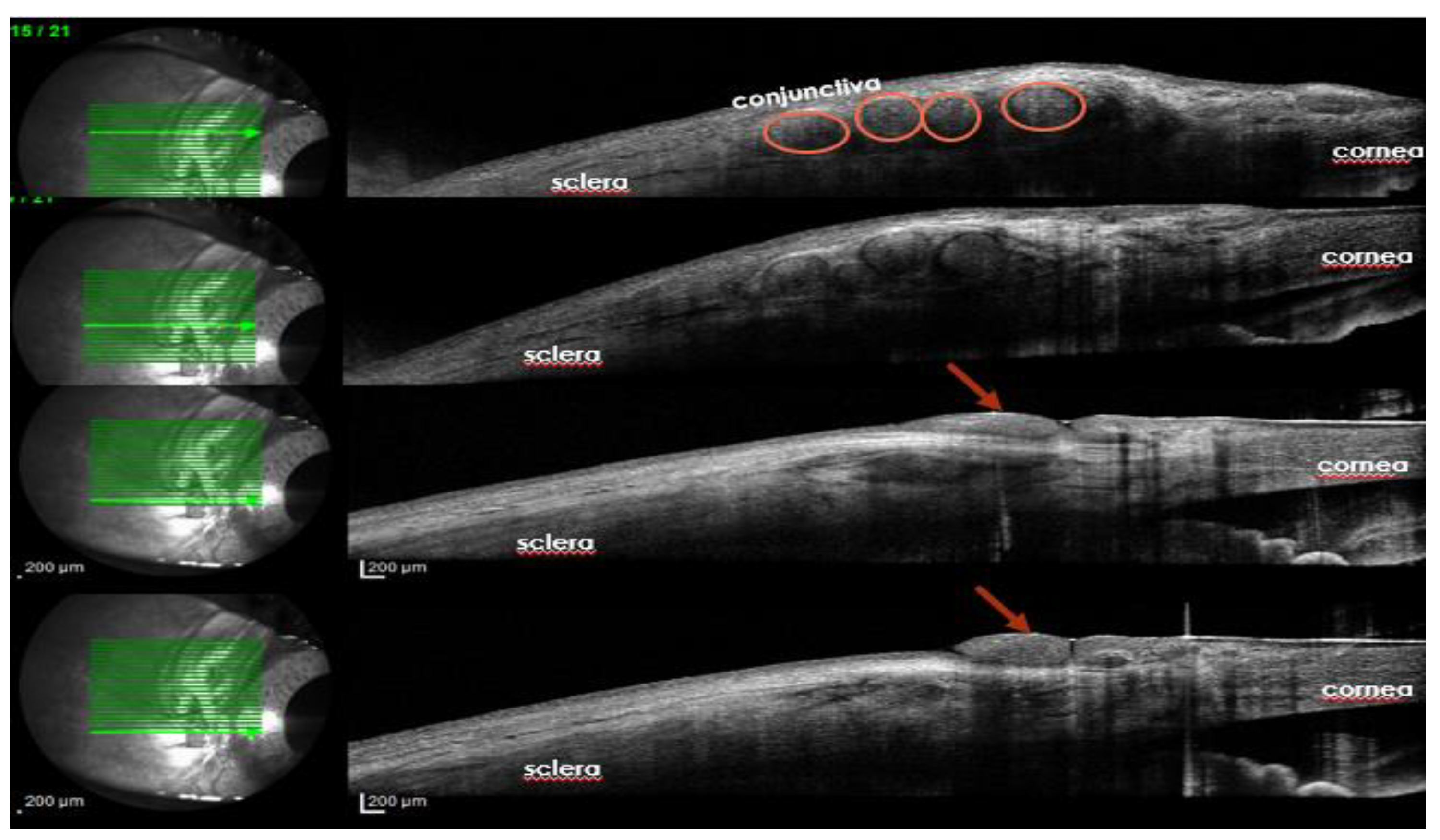

We suggest that the presence of nerve filaments tunneled around the cornea could be observed with ocular coherence tomography (

Figure 3). Refinements in anterior segment OCT could improve nerve fiber detection at the level of corneal sub-basal plexus.

Limitations

As mentioned before, there are not enough patients to receive neurotization so far. Only 164 patients in total were included in this review. Some of the articles includes lacked data regarding CCS or objective measurement, like IVCM. It seems that only a few centers have experience with many patients, most of the reports found in online databases being case reports or small sample reports.