Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

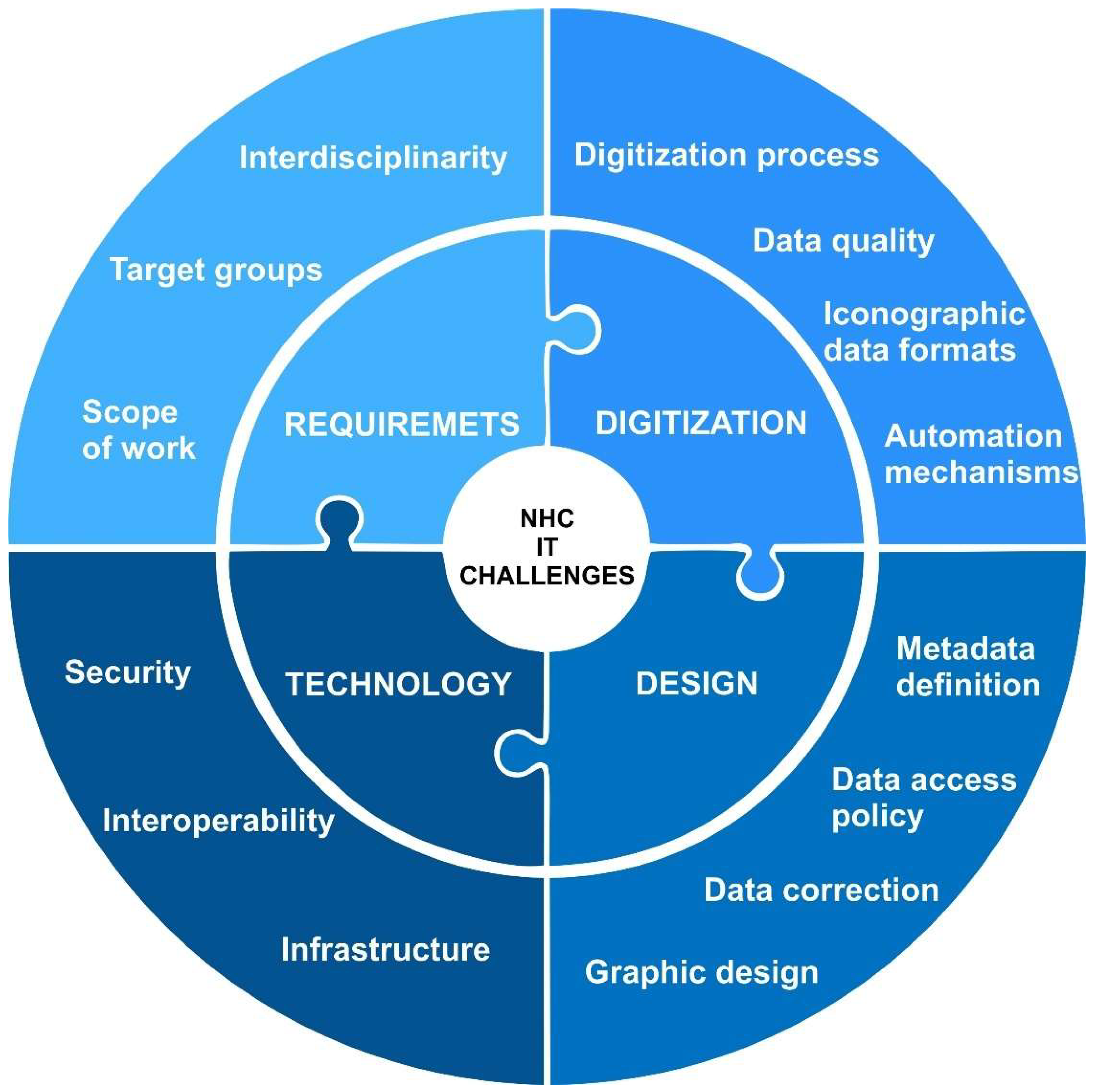

Numerous institutions engaged in the management of Natural History Collections (NHC) are embracing the opportunity to digitize their holdings. The primary objective is to enhance accessibility to the specimens for interested individuals and to integrate into the global community by contributing to an international specimen database. This initiative demands a comprehensive digitization process and the development of an IT infrastructure that adheres to stringent standards of functionality, reliability, and security. The focus of this endeavor is on the procedural and operational dimensions associated with the accurate storage and management of taxonomic, biogeographic, and ecological data pertaining to biological specimens digitized within a conventional NHC framework. The authors suggest categorizing the IT challenges into four distinct areas: requirements, digitization, design, and technology. Each category discusses a number of selected topics, highlighting often underestimated essentials related to the implementation of the NHC system. The presented analysis is supported by numerous examples of specific implementations enabling a better understanding of the given topic. This document serves as a resource for teams developing their own systems for online collections, offering post factum insights derived from implementation experiences.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

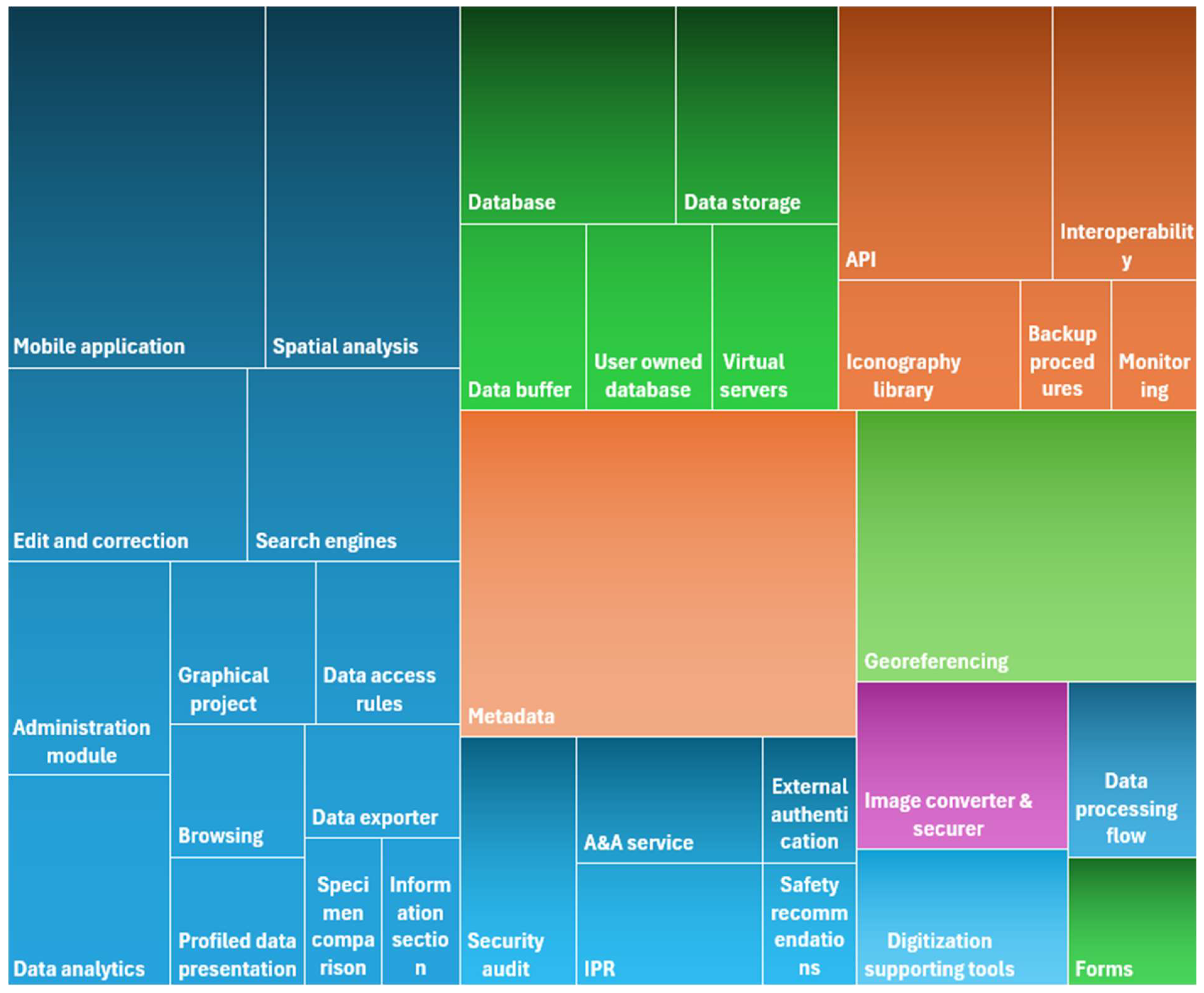

3. Planning and Building Online Natural Collection Systems

3.1. Requirements

3.1.1. Scope of the System Specification

| Name | Optionality | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Digitization | ||

| Data processing flow | Obligatory | The data flow diagram defines the tasks, responsibilities and resources used to conduct the digitization process in order to achieve the highest possible efficiency. See more in Section 3.2.1. |

| Metadata | Obligatory | A set of metadata used to register unique resources of natural collections gathered by the housing organization. Given the high complexity of the database, this description allows for unambiguous, compliant with international standards, information entry. See more in Section 3.3.1. |

| Forms | Obligatory | Forms are used to prepare a metadata description according to an accepted structure, avoiding inconsistencies between data entered by different people. Usually created as a spreadsheet file. It contains all the necessary attributes according to the metadata specification, divided into sheets covering e.g. taxa, samples, iconography and bibliographic entries. See more in Section 3.2.4. |

| Digitization supporting tools | Optional | A collection of instruments designed to facilitate the digitization of specimens throughout different phases of their preparation. The validator enables the verification of the description's adherence to established guidelines, while the converter aids in transforming existing specimen descriptions into a new format. The aggregator serves to merge files containing descriptions created by various teams, and the report generator is utilized to compile the total number of records in the description files. This tool is particularly beneficial for project coordinators in their efforts to continuously monitor the advancement of digitization activities. See more in Section 3.2.4. |

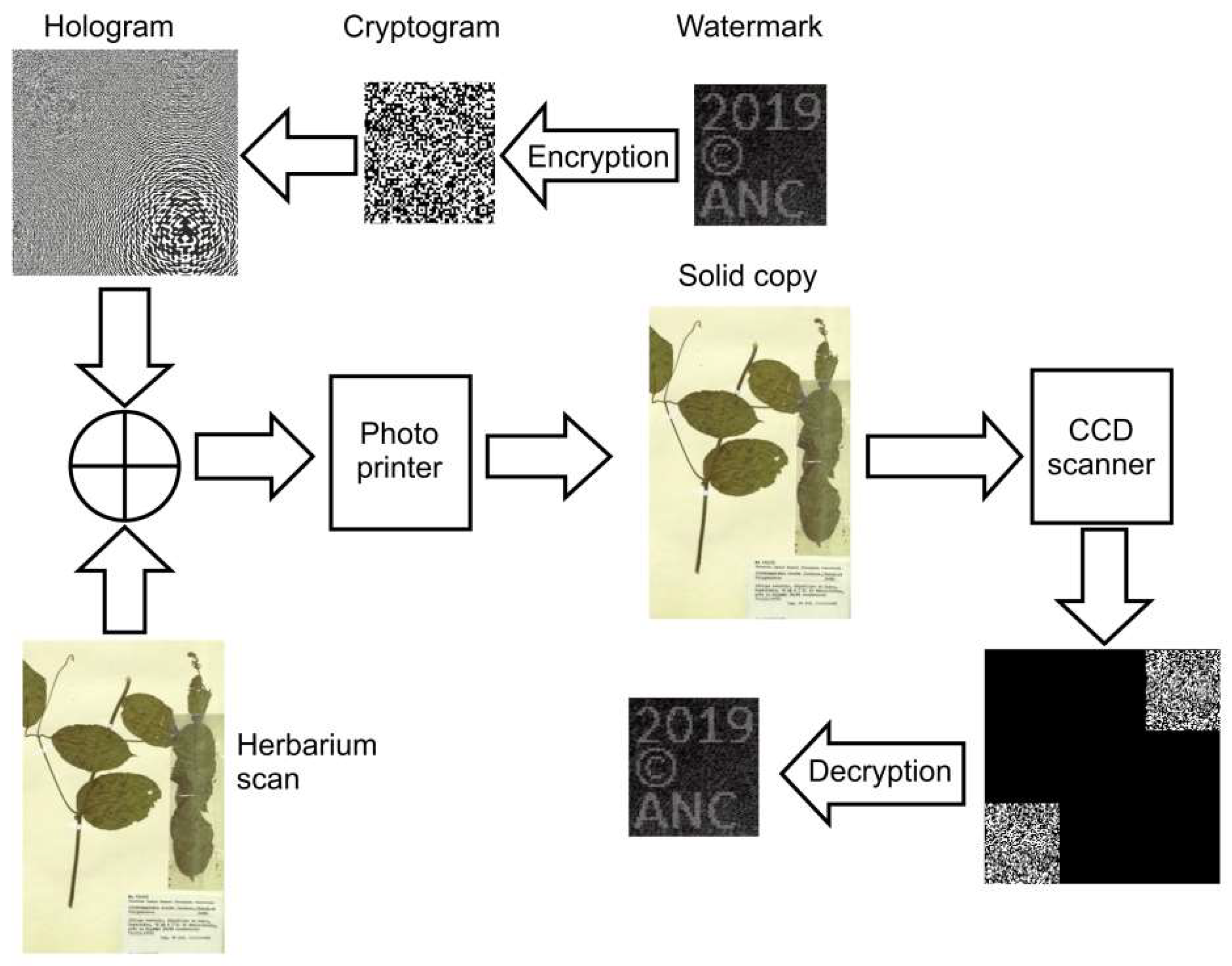

| Image converter & securer | Obligatory (in terms of converting) | A tool whose task is to convert a graphic file (scan, photo) to the format required by modules for sharing and presentation in the final user interfaces. Optionally, the tool includes a set of functions for securing iconography in order to protect copyright. See more in Section 3.4.3.3. |

| Georeferencing | Obligatory | All records were geotagged based on the textual descriptions of the specimens' locations, such as those found on herbarium sheets. This geotagging facilitates analysis through the Geographic Information System, enabling the examination of digitized records and the identification of spatial relationships. There are different quality class of geotagging records:

|

| End user interfaces | ||

| Browsing | Obligatory | Data browsing should be available in a general view from the main page for both logged-in and non-logged-in users. The scope of information received may, however, be varied (non-logged-in users see only part of the information about the specimens). In addition to the general view, the ability to browse data in a profiled way, adapted to the needs of different user groups and their level of advancement, may be optionally provided. |

| Search engine(s) | Obligatory | Search engines serve as fundamental instruments for examining the amassed data on specimens. It is advisable to develop search engines tailored to specific target audiences, providing varying levels of complexity and functionality. A potential categorization includes search engines such as general, specialized, collections, systematic groups, samples, multimedia, bibliography, and educational. For instance, a multimedia search engine facilitates access to information presented in formats such as images, videos, maps, or audio recordings that are either related to the stored specimens (for example, a scan of a herbarium) or independent of them (such as a photograph of a habitat), thereby enabling access to a multimedia database that complements the archived specimens. |

| Profiled data presentation | Optional | Adjusting the portal view to the target group according to their knowledge and interests. Adjustment concerns the advancement of the search engine (complexity of queries), the language of phrases during the search or the scope of presented data. The view can be set depending on your own preferences. For more please reach Section 3.1.2. |

| Graphical project | Obligatory | Meeting WCAG requirements in the project concerns the access interfaces on which users operate, i.e. the portal and the mobile application. Implementation of WCAG principles is legally required. Effective UX (User Experience) and UI (User Interface) design allows users to easily locate the content they anticipate. One can argue that users' online behaviours and preferences are quite similar to those of customers in a retail environment. In accordance with UX principles, it is essential to anticipate the actions users will take to access features or information, commonly referred to as user flow. More in Section 3.3.4. |

| Administration module | Obligatory (scope for discussion) | Composed of: account management, permission levels, profile settings, reports and stats, protected taxa, protected areas, manage users' roles, files report, file sources, team leaders, editor tools, Excel files tools, task history, database changes history |

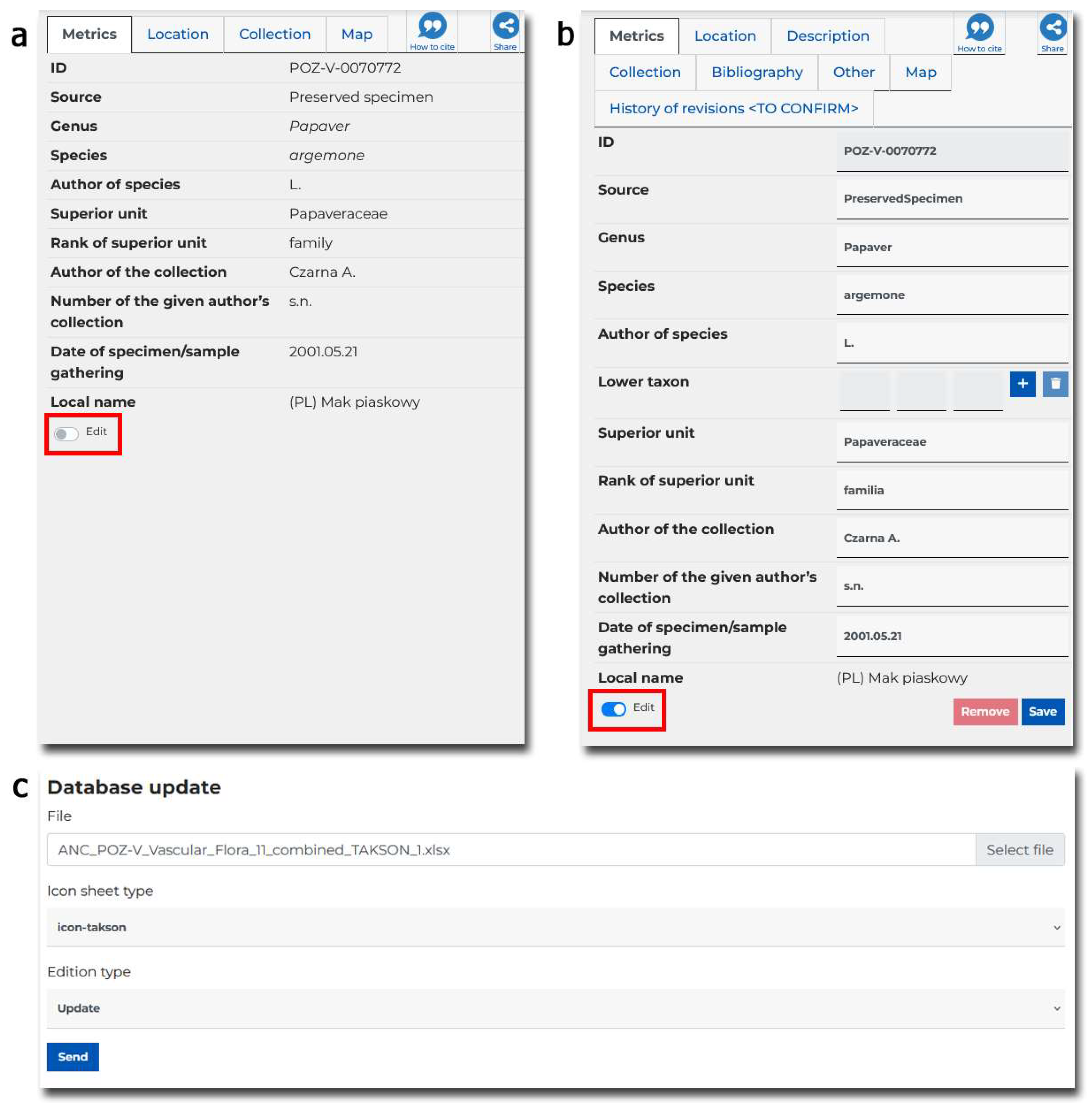

| Edit and correction | Obligatory (optional at portal level) | Available at the portal level providing the possibility of correcting data describing natural collections within two modes: a) editing a single record - in the details view of a given record (specimen, samples, bibliography, iconography and multimedia), an authorized person can switch the details view to the editing mode. It is then possible to correct all fields of a given record and save it. Changes are made and visible immediately. b) group editing of many taxonomic records - often, the attribute value for records is corrected simultaneously. Such a change is possible from the level of statistical tools - reports. Search results can be grouped according to a selected field, and then the value of the selected field can be changed for all records from this group. For more see Section 3.3.3. |

| Data access rules | Optional | It allows to limit access to sensitive information, due to the protection of diversity, and especially the protection of species that are subject to protection. Access to sensitive information requires appropriate authorizations. Data is protected at two levels: specimen (full information about the specimen), field (a specific feature of the specimen may be restricted). More in Section 3.3.2. |

| Data exporter | Optional | This feature can be utilized when displaying search result data, contingent upon the acquisition of the necessary permissions. It enables users to download the retrieved data as a spreadsheet file that adheres to the specified format. The data obtained through this method can subsequently be analysed using external analytical tools. |

| Data analytics (reports) | Optional | A tool designed to produce statistical reports utilizing data from specimens stored in the database. This reporting tool enables the categorization of data based on one or multiple parameters and facilitates the creation of graphs that illustrate the proportion of a specific group of specimens within the results generated by the query. It serves as an invaluable resource for understanding the contents of collections, including the identification of discrepancies in metadata descriptions, such as the presence of species in regions where they are not expected to occur. |

| Specimen comparison | Optional | The functionality allows for the comparison of two or more (depending on the scheme used) specimens. A feature especially desired by scientists conducting in-depth analyses. |

| Support for team Colaboration | Optional | Group of users working on the same topic can create a team and share their observations with team supervisor. The feature can be used by scientist e.g. while working in the field as well as by school teachers. |

| Preparation of educational materials | Optional | Specimens, photos and observation can be added to user defined albums and complemented with custom description. Such albums can be then shared with other users or exported in a form of pdf presentation. |

| Spatial analysis BioGIS (GIS tools) | Optional | The BioGeographic Information System (BioGIS) serves as a tool for the entry, collection, processing, and visualization of geographic data. It has become extensively utilized in scientific research and decision-making activities, particularly in the field of biodiversity studies. It allows for the presentation of phenomena in space on different type of maps, e.g.: dot distribution map, area class map, choropleth map, diagram map, cluster map, attribute grouping map, timelaps map. |

| Information section | Optional | A section at a portal containing following information: mission, portal (info on offering), mobile application, BioGIS, our users (info on target groups), about us, how to use (guidelines), contact. |

| Mobile application | Optional | The mobile application facilitates the documentation of natural observations through text descriptions, photographs, and audio recordings. Observations are exported to a database and become accessible from the portal, which in turn allows them to be edited and used with existing analytical and georeferencing tools. The observation form is equipped with a set of predefined fields as well as customizable open fields that users can define according to their preferences. The predefined fields encompass ordinal data, identification details of the observation (such as number, date, and author), geographical coordinates of the observation site, area size, and vegetation coverage. This allows for greater engagement of target groups, but also for reaching external users who use the NHC system to create their own collections of specimens and other natural observations |

| Backend services | ||

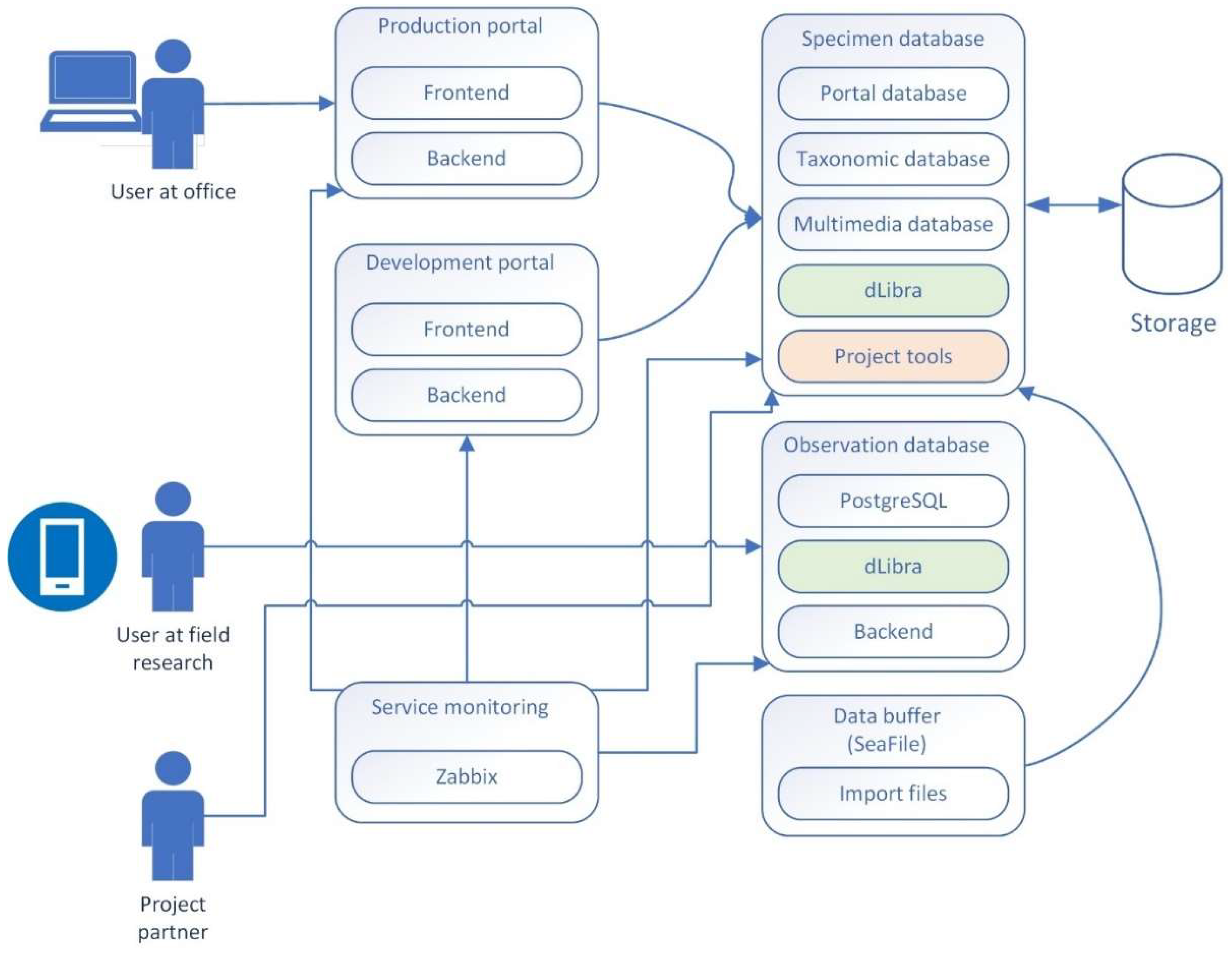

| API | Obligatory | The API is used to provide interested parties with automatic access to the contents of the database. Access to the NHC system takes place through an interface implemented in REST (REpresentational State Transfer) technology. Considering that the portal and the mobile application use the same programming interface its implementation is obligatory. Most of the offered functionalities are available only to the logged-in user; therefore, access to individual interface methods is secured with JSON Web Token. |

| Interoperability | Optional | This functionality enables the provision of specific information from the taxonomic database to external organizations, facilitating database integration. For instance, to support integration with GBIF, the "BioCASe Provider Software" (BPS) service was developed, which is compatible with the "Biological Collection Access Service." This global network of biodiversity repositories amalgamates data on specimens from wildlife collections, botanical gardens, zoos, and various research institutions worldwide, alongside information from extensive observational databases. Check Section 3.4.2 for more information. |

| Iconography library | Obligatory | A library for sharing digital objects and documents used to import and store multimedia. It should include a range of features that make it easier to enter, manage and use digital assets, such as serving images in the required resolution and storing related metadata to make it easier to find the desired content. |

| Backup operational procedures | Obligatory | A set of procedures and mechanisms focused on archiving and restoring data after a failure. |

| Monitoring | Optional | Ensuring the continuity of the system’s operation and the security of the data stored in it is extremely important due to access to the data and services offered. Monitoring with a given time interval a defined list of key services. Information about the unavailability of services is sent by email to a designated person or group of people. This allows for immediate intervention by service administrators and restoration of their operation. |

| Infrastructure | ||

| Data buffer | Obligatory | A designated place in the storage system allowing for saving and storing data after the digitization process and before the actual import into the database. Please reference to 3.4.1.2 for more information. |

| Data storage | Obligatory | Space on array disks or tape systems that allows for storing source data and processed data along with their copies in a safe manner after the database import process. Disk arrays also deal with serving data to design applications (portal and mobile application). Please reference to 3.4.1.2 for more information. |

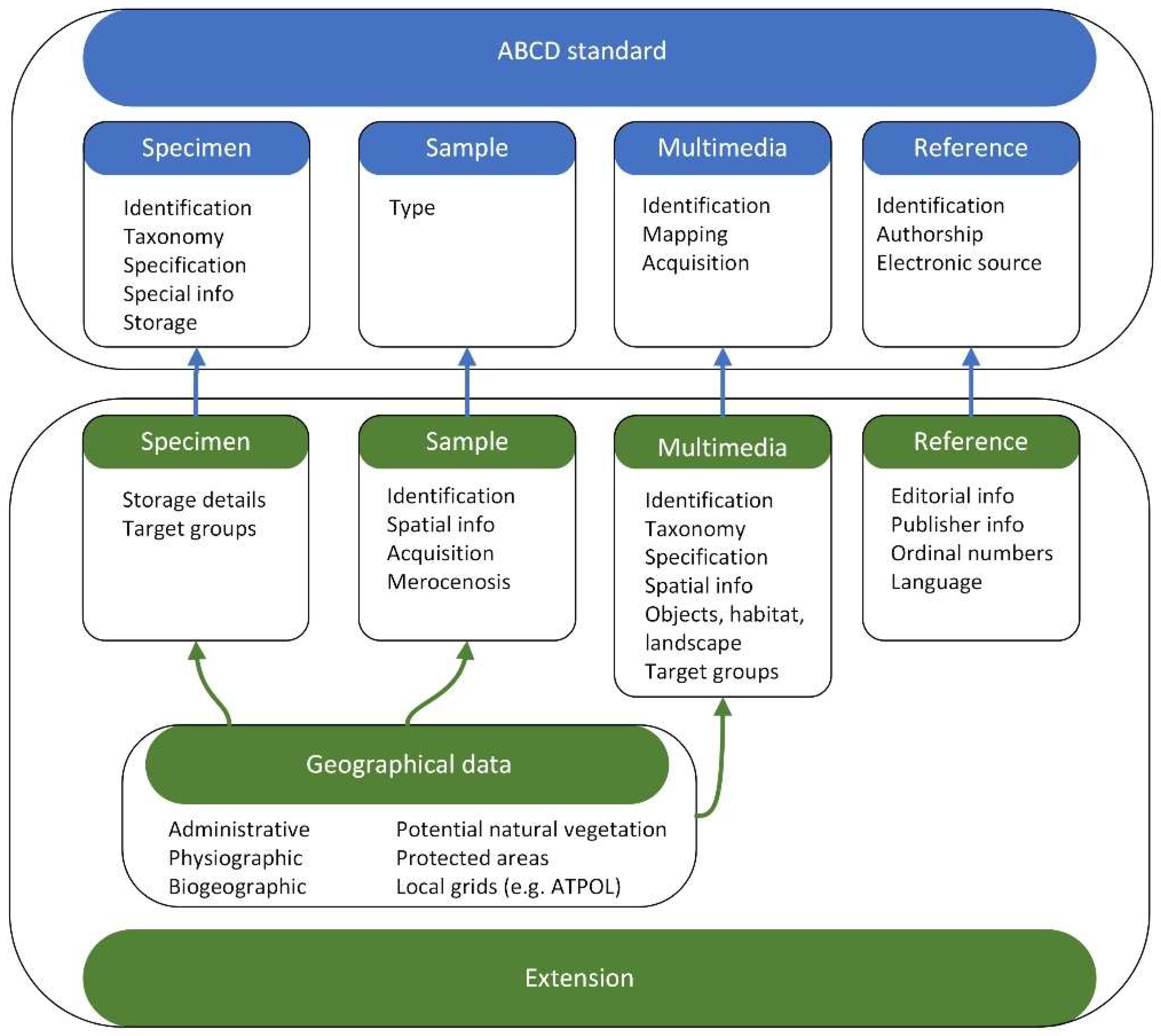

| Database | Obligatory | The database is a core of the NHC system, the content of which is based primarily on collections of biological specimens, as well as locations of photographs and published or previously unpublished field observations. In addition, its structure should correspond to the set of metadata defined by international standards (e.g. ABCD) and the requirements of the target groups. More in Section 3.4.1.3. |

| Database for users’ content | Optional | Enables storing information independent of the data that make up the Natural History Collections Database and is available only to a given user and authorized persons. Mainly concerns the sections like: my observations, my albums, my maps, my teams. |

| Virtual servers | Obligatory | In order to provide customers with only ready-made and tested solutions that meet the expected requirements, the infrastructure has been divided into a development and production part. Each new functionality is subjected to a validation procedure and only after its positive result is it made available to the end customer. More in Section 3.4.1.3. |

| Security | ||

| Authentication and authorization service | Obligatory | A service that allows for user authentication and authorization. Authentication verifies the user's identity using credentials such as passwords, biometrics, or third-party authentication providers. Authorization (access control) controls what authenticated users can access. |

| External authentication service | Optional | Enabling login using existing user credentials from platforms such as Apple, Google or Facebook. This improves the user experience and reduces the need to remember multiple usernames and passwords. |

| Safe programming recommendations | Optional | Implementation of general recommendations for secure programming during code implementation in accordance with the SDLC (Software Development LifeCycle) concept. Application of detailed security recommendations for programming languages used in project creation. More in Section 3.4.3.1. |

| Security audit | Obligatory | The need to conduct an audit by a qualified team of experts in at least two stages: halfway through the project (early detection of weaknesses) and at its end (verification of the implementation of previous recommendations and final check of the system's vulnerabilities). Particular attention should be paid to issues related to: user password management, serving content via the web server, configuring the server itself and user registration. More in Section 3.4.3.2. |

| Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) | Obligatory | Preserving IPR to published materials. Security issues include the methodology of securing iconographic data, with particular emphasis on graphic files from both the specimen scanning process and photographs presenting observation data. Additionally, they are related to the proper way of citing the materials used by external scientists. More information at 3.4.3.3. |

3.1.2. Target Groups

3.1.3. Interdisciplinarity

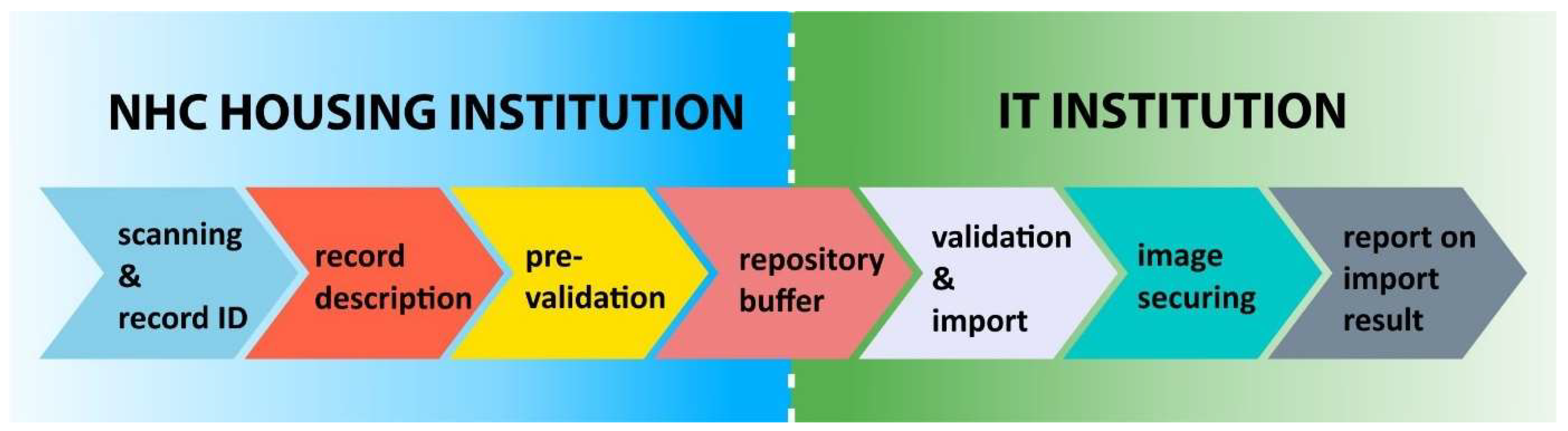

3.2. Digitization

3.2.1. Digitization Process

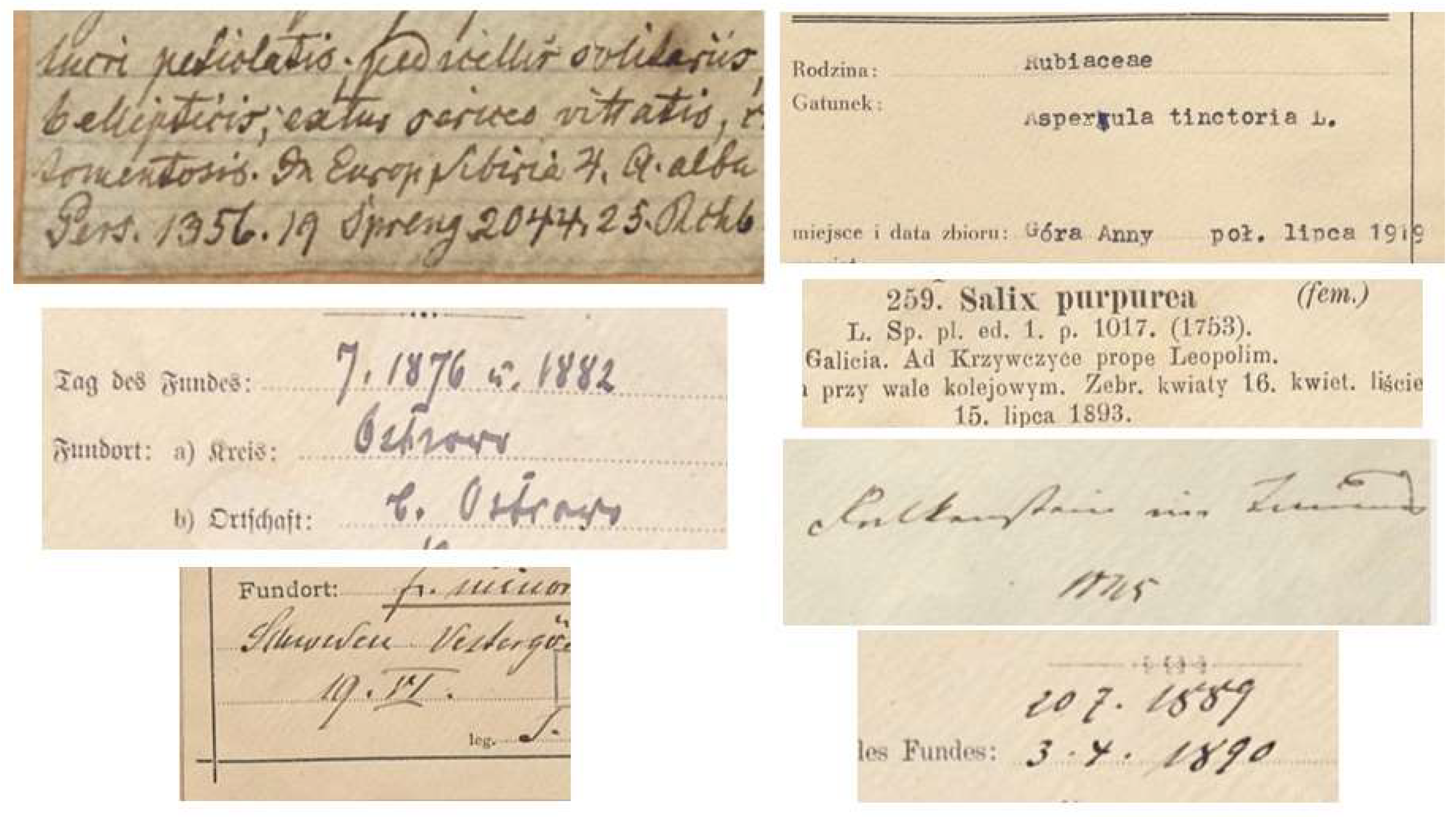

3.2.2. Data quality - Date Uncertainty and Ambiguity

| Read value | Comment |

|---|---|

| 19.VI | Lack of year |

| 20.7.1889, 3.X.1890 | month given in Arabic or Roman numerals |

| 7.1876 ü 1882 | Date given (probably) without day and with double year |

| mid July (in Polish “połowa lipca”) 1919 | Imprecise harvest day |

| end of May (in Polish “koniec maja”) 1916 | Imprecise harvest day |

| flowers (in Polish “kwiaty”) 16.04, leaves (in Polish “liście”) 15.07.1893 |

Providing the date (without the year), and two specimens on one sheet |

| 19?5 | One of the year digits is not legible |

3.2.3. Iconographic Data Formats

3.2.4. Automation of Digitalization Procedures

3.3. Design

3.3.1. Metadata Definition

| Field content description: | Contains brief information about the type of information that should be entered into a given field. |

| Field format: | Specifies whether the field is a field of a specific format: Integer field, Float field, Text field, Date field in ABCD format. |

| Allowed values: | This field contains only values from the allowed list. Each list item is entered on a separate line. |

| Required field: | The word YES in this field description element indicates that the field is mandatory. The word NO in this field description element indicates that the field is optional. |

| Example values: | This description element provides example values for the field. |

| Comments: | Space for any additional information related to the field. |

3.3.2. Data Access Restrictions

| Level | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | the field is not protected, everyone can see it, even if they are not logged in, e.g. genus, species, |

| 1 | the field is only available to logged in users (e.g. ATPOL coordinates), |

| 2 | the field is only available to trusted collaborators, e.g. exact coordinates, exact habitat, |

| 3 | the field is only available to authorized internal users, e.g. suitability for target groups, technical information regarding file import. |

3.3.3. Data Correction

3.3.4. Graphic Design

3.4. Technology

3.4.1. Infrastructure

3.4.1.1. Understanding Specimen Quantity Factor

3.4.1.2. Storage Space

| Regular | Economical | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Operation name or location | Factor | TB | TB |

| Source material | 90 | 90 | |

| Processed and protected material | 1.6 | 144 | 144 |

| RAID 6 | 0.2 | 46.8 | 46.8 |

| Conversion to ISO | 0.1 | 28.08 | 28.08 |

| Total in one location | 308.88 | 308.88 | |

| Geographic copy | 308.88 | 308.88 | |

| Local copy | 308.88 | 118.8 | |

| Buffer for the digitization process | 120 | 120 | |

| TOTAL | 1046.64 | 856.56 | |

| CONVERSION RATE | ~11.63 | ~9.52 | |

3.4.1.3. Computing and Service Resources

3.4.2. Interoperability

| Dataset related fields | ||

|---|---|---|

| ABCD | AMUNATCOLL | |

| Property Name | Link to specification | Property Name / Comment |

| /DataSets/DataSet/ContentContacts/ContentContact/Name | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:ContentContact-Name | Information generated automatically during export depending on the custodian of a given collection |

| TechnicalContact/Name | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:TechnicalContact-Name | Information generated automatically during export |

| /DataSets/DataSet/ContentContacts/ContentContact/Organization/Name/Representation/@language | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:DataSet-Representation-@language | Information generated automatically during export |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Metadata/Description/Representation/Title | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:DataSet-Title | Information generated automatically during export |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Metadata/RevisionData/DateModified | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:DataSet-DateModified | Date of last import, date generated automatically by the system during export |

| Specimen fields | ||

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/SourceInstitutionID | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:SourceInstitutionID | Institution |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/SourceID | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:SourceID | Botany / Zoology |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/UnitID | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:UnitID | Collection / Specimen number |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/RecordBasis | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:RecordBasis | Source |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/SpecimenUnit/NomenclaturalTypeDesignations/NomenclaturalTypeDesignation/TypifiedName/NameAtomised/Botanical/GenusOrMonomial | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:TaxonIdentified-Botanical-GenusOrMonomial | Genus |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/Identifications/Identification/Result/TaxonIdentified/ScientificName/NameAtomised/Zoological/GenusOrMonomial | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:TaxonIdentified-Zoological-GenusOrMonomial | Genus |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/Identifications/Identification/Result/TaxonIdentified/ScientificName/NameAtomised/Botanical/FirstEpithet | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:TaxonIdentified-FirstEpithet | Species |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/Identifications/Identification/Result/TaxonIdentified/ScientificName/NameAtomised/Zoological/SpeciesEpithet | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:TaxonIdentified-Zoological-SpeciesEpithet | Species |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/Gathering/Agents/GatheringAgent/Person/FullName | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:GatheringAgent-FullName | Author of the collection |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/Identifications/Identification/Identifiers/Identifier/PersonName/FullName | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:Identifier-FullName | Author of designation |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/Gathering/DateTime/ISODateTimeBegin | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:Gathering-DateTime-ISODateTimeBegin | Date of specimen/sample collection |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/SpecimenUnit/Preparations/Preparation/PreparationType | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:SpecimenUnit-PreparationType | Storage method |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/Gathering/SiteCoordinateSets/SiteCoordinates/CoordinatesLatLong/LatitudeDecimal | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:Gathering-LatitudeDecimal | Latitude |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/Gathering/SiteCoordinateSets/SiteCoordinates/CoordinatesLatLong/LongitudeDecimal | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:Gathering-LongitudeDecimal | Longitude |

| /DataSets/DataSet/Units/Unit/Identifications/Identification/Result/TaxonIdentified/ScientificName/FullScientificNameString | https://terms.tdwg.org/wiki/abcd2:TaxonIdentified-FullScientificNameString | Required by Darwin Core. Merging of several fields: Genus + Species + SpeciesAuthor + YearOfCollection |

3.4.3. Security

3.4.3.1. Security Programming Practices

3.4.3.2. Security System Audit

3.4.3.3. Securing Iconographic Data

| Tag | Exemplary value |

|---|---|

| ID | POZ-V-0000001 |

| Image Description | The image depicts a scan from the Natural History Collections of Housing Institution Name. |

| Copyright | Copyright © 2025 Housing Institution Name, City. All rights reserved. |

| Copyright note | This image or any part of it cannot be reproduced without the prior written permission of Housing Institution Name, City. |

| Additional Information | Deleting or changing the image metadata is strictly prohibited. For more information on restrictions on the use of photos, please visit: https://www.domain.com/ |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABCD | Access to Biological Collection Data |

| ACID | Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability) |

| AMUNATCOLL | Adam Mickiewicz University Nature Collections |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| BPS | BioCASe Provider Software |

| BioGIS | BioGeographic Information System |

| CGH | Computer Generated Hologram |

| CI/CD | Continuous Integration/Continuous Delivery |

| DMP | Data Management Plan |

| EBV | Essential Biodiversity Variables |

| EXIF | Exchangeable Image File Format |

| FAIR | Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Re-usable |

| GBIF | Global Biodiversity Information Facility |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| HDD | Hard Disk Drive |

| IPR | Intellectual Property Rights |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| IT | Information Technology |

| JWT | JSON Web Token |

| NHC | Natural History Collection |

| OWASP | Open Web Application Security Project |

| PCI DSS | PCI Data Security Standard |

| RAID | Redundant Array of Independent Disks |

| REST | REpresentational State Transfer |

| SDLC | Software Development LifeCycle |

| SDL | Security Development Lifecycle |

| SEO | Search Engine Optimization |

| SSD | Solid State Drive |

| SSRF | Server-Side Request Forgery |

| TIFF | Tag Image File Format |

| UX | User Experience |

| UI | User Interface |

| WCAG | Web Content Accessibility Guidelines |

References

- Lawrence M. Page, Bruce J. MacFadden, Jose A. Fortes, Pamela S. Soltis, and Greg Riccardi, "Digitization of Biodiversity Collections Reveals Biggest Data on Biodiversity," BioScience, vol. 65, no. 9, pp. 841–842, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Pamela S Soltis, Gil Nelson, and Shelley A James, "Green digitization: Online botanical collections data answering real-world questions," Appl Plant Sci., vol. 6, no. 2, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Richard T. Corlett, "Achieving zero extinction for land plants," Trends in Plant Science, vol. 28, no. 8, pp. 913-923, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Pereira et al., "Essential Biodiversity Variables," Science, vol. 339, no. 6117, pp. 277-278, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Bogdan Jackowiak et al., "Digitization and online access to data on natural history collections of Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan: Assumptions and implementation of the AMUNATCOLL project," Biodiversity: Research and Conservation, vol. 65, 2022. [CrossRef]

- KEW. (2025) KEW Data Portal. [Online]. Available online: https://data.kew.org/?lang=en-US.

- MNP. (2025) Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in Paris - collections. [Online]. Available online: https://www.mnhn.fr/en/databases.

- PVM. (2025) Plantes vasculaires at Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle. [Online]. Available online: https://www.mnhn.fr/fr/collections/ensembles-collections/botanique/plantes-vasculaires.

- TRO. (2025) Tropicos database. [Online]. Available online: http://www.tropicos.org/.

- NDP. (2025) Natural History Museum Data Portal. [Online]. Available online: https://data.nhm.ac.uk/about.

- SMI. (2025) Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. [Online]. Available online: https://collections.nmnh.si.edu/search/.

- Maciej M Nowak, Marcin Lawenda, Paweł Wolniewicz, Michał Urbaniak, and Bogdan Jackowiak, "The Adam Mickiewicz University Nature Collections IT system (AMUNATCOLL): portal, mobile application and graphical interface," Biodiversity: Research and Conservation, vol. 65, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dirk S. Schmeller et al., "A suite of essential biodiversity variables for detecting critical biodiversity change," Biol Rev, vol. 93, pp. 55-71, 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Jetz, M.A. McGeoch, R. Guralnick, and et al., "Essential biodiversity variables for mapping and monitoring species populations," Nat Ecol Evol, pp. 539–551, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Alex R. Hardisty et al., "The Bari Manifesto: An interoperability framework for essential biodiversity variables," Ecological Informatics, vol. 49, pp. 22-31, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Luiz M. R. Jr Gadelha, Pedro C. de Siracusa, and Eduardo Couto Dalcin, "A survey of biodiversity informatics: Concepts, practices, and challenges," WIREs Data Mining Knowl Discov., vol. 11:e1394, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Feest, Ch. Swaay van , T. D. Aldred, and K. Jedamzik, "The biodiversity quality of butterfly sites: A metadata assessment," Ecological Indicators, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 669-675, 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Walls et al., "Semantics in Support of Biodiversity Knowledge Discovery: An Introduction to the Biological Collections Ontology and Related Ontologies," PLOS ONE, vol. 9, no. 3, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J.R. Silva da et al., "Beyond INSPIRE: An Ontology for Biodiversity Metadata Records," OTM Confederated International Conferences "On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems", 2014. [CrossRef]

- Marcin Lawenda, Justyna Wiland-Szymańska, Maciej M. Nowak, Damian Jędrasiak, and Bogdan Jackowiak, "The Adam Mickiewicz University Nature Collections IT system (AMUNATCOLL): metadata structure, database and operational procedures," Biodiversity: Research and Conservation, vol. 65, 2022. [CrossRef]

- ANC. (2025) AMUNatColl project. [Online]. Available online: http://anc.amu.edu.pl/eng/index.php.

- FBAMU. (2025) Faculty of Biology of the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. [Online]. Available online: http://biologia.amu.edu.pl/.

- PSNC. (2025) Poznan Supercomputing and Networking Center. [Online]. Available online: https://www.psnc.pl/.

- ANCPortal. (2025) AMUNATCOLL Portal. [Online]. Available online: https://amunatcoll.pl/.

- ANDR. (2025) AMUNATCOLL Mobile Application - Android. [Online]. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=pl.pcss.amunatcoll.mobile.

- IOS. (2021) AMUNATCOLL Mobile Application - iOS. [Online]. Available online: https://apps.apple.com/pl/app/amunatcoll/id1523442673.

- Seafile. (2025) Open Source File Sync and Share Software. [Online]. Available online: https://www.seafile.com/en/home/.

- (2017) ISO - International Organization for Standardization. [Online]. Available online: https://www.iso.org/iso-8601-date-and-time-format.html.

- (2002) RFC 3339: Date and Time on the Internet: Timestamps. [Online]. Available online: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc3339.html.

- Guo, N.; Xiong, W.; Wu, Q.; Jing, N. An Efficient Tile-Pyramids Building Method for Fast Visualization of Massive Geospatial Raster Datasets. Adv. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2016, 16, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIS. (2025) Biodiversity Information Standards. [Online]. Available online: https://www.tdwg.org/.

- DCMI. (2025) The Dublin Core™ Metadata Initiative. [Online]. Available online: https://www.dublincore.org/.

- William K. Michener and Matthew B. Jones, "Ecoinformatics: supporting ecology as a data-intensive science," Trends in Ecology & Evolution, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 85-93, 2012. [CrossRef]

- E. Kacprzak et al., "Characterising dataset search—An analysis of search logs and data requests," Journal of Web Semantics, 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Löffler, V. Wesp, B. König-Ries, and F. Klan, "Dataset search in biodiversity research: Do metadata in data repositories reflect scholarly information needs?," PLoS ONE, vol. 16, no. 3, 2021. [CrossRef]

- DwC. (2025) Darwin Core standard. [Online]. Available online: https://dwc.tdwg.org/.

- ABCD. (2025) Access to Biological Collections Data standard. [Online]. Available online: https://www.tdwg.org/standards/abcd/.

- Steve Krug, Don't make me think! Web & Mobile Usability.: MITP-Verlags GmbH & Co. KG, 2018.

- EUDirective2019-882. (2019) European Accessibility Act (EAA) – Directive (EU) 2019/882. [Online]. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/882/oj/eng.

- EUDirective2016-2102. (2016) Web Accessibility Directive – Directive (EU) 2016/2102. [Online]. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2016/2102/oj/eng.

- EN301549. (2021) European Standard EN 301 549. [Online]. Available online: https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_en/301500_301599/301549/03.02.01_60/en_301549v030201p.pdf.

- GBIF. (2025) Global Biodiversity Information Facility. [Online]. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/en/.

- Qisi Liu and Liudong Xing, "Reliability Modeling of Cloud-RAID-6 Storage System," International Journal of Future Computer and Communication, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 415-420, 2015. [Online]. Available online: https://www.ijfcc.org/show-61-745-1.html.

- ISOUNITS. (2025) Standards by ISO/TC 12 Quantities and units. [Online]. Available online: https://www.iso.org/committee/46202/x/catalogue/.

- ByteUnits. (2025) Wikipedia - Multiple-byte units. [Online]. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Byte&utm_campaign=the-difference-between-kilobytes-and-kibibytes&utm_medium=newsletter&utm_source=danielmiessler.com#Multiple-byte_units.

- Pooya Rostami Mazrae, Tom Mens, Mehdi Golzadeh, and Alexandre Decan, "On the usage, co-usage and migration of CI/CD tools: A qualitative analysis," Empir Software Eng, vol. 28, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fangming Guo, Caijun Chen, and Ke Li, "Research on Zabbix Monitoring System for Large-scale Smart Campus Network from a Distributed Perspective," Journal of Electrical Systems, vol. 20, no. 10, pp. 631-648, 2024. [Online]. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/9f42244a7b3a7f64dfd1484ed04f63e8.

- PostgreSQL. (2025) PostgreSQL database web site. [Online]. Available online: https://www.postgresql.org/.

- dLibra. (2025) Digital Library Framework. [Online]. Available online: https://www.psnc.pl/digital-libraries-dlibra-the-most-popular-in-poland/.

- Erik Wilde and Cesare Pautasso, REST: From Research to Practice. NY: Springer New York, 2011. [CrossRef]

- JWT. (2025) JSON Web Tokens. [Online]. Available online: https://jwt.io/.

- BioCASe. (2025) Biological Collection Access Service. [Online]. Available online: http://www.biocase.org/.

- (2025) GBIF Data Standards. [Online]. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/standards.

- Hassan Saeed et al., "Review of Techniques for Integrating Security in Software Development Lifecycle," Computers, Materials & Continua, vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 139-172, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ryan Dewhurst. (2025) Static Code Analysis. [Online]. Available online: https://owasp.org/www-community/controls/Static_Code_Analysis.

- OWASP. (2025) Open Web Application Security Project. [Online]. Available online: https://owasp.org/.

- EXIF. (2025) Exchangeable Image File Format. [Online]. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exif.

- Dapu Pi et al., "High-security holographic display with content and copyright protection based on complex amplitude modulation," Optics Express, vol. 32, no. 17, pp. 30555-30564, 2024. [CrossRef]

| Action | Species search language | Search | Browsing |

|---|---|---|---|

| View | |||

| General | national (e.g. English, Polish) | simplified - one field whose value is matched to many fields from the specimen description | browse in list, map and aggregated reports; key information about specimens |

| Scientific | Latin | Simple - a few selected fields Extended - adding multiple fields to search conditions Advanced - any definition of complex conditions including logical expressions |

browse as list, map and aggregated reports. Full information about specimens |

| Educational | national, including everyday language | simplified - mainly searching from available educational materials | Educational materials about the specimen |

| Public administration | national, Latin | search among species | Aggregated reports for selected species |

| State services | national, Latin | Mainly from protected and similar species | Graphic information is essential |

| Code | Format description | Extension | Volume | Creation Way | Typical applications | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAW | Output files obtained directly from the digitizing device, in a device-specific format (e.g. recording format) | depending on the device, e.g. .CRW or .CR2 for Cannon cameras | big | It is created manually or semi-automatically (depending on the equipment), in the digitization process. | long-term data archiving | The format is often manufacturer dependent, may be closed, patented etc. so it is not recommended as the only form of long-term archiving. Some devices (e.g. scanners) can generate TIFF files immediately, without the RAW option. |

| MASTER | Lossless transformation of a RAW file to an open format, without any other changes. | most often TIFF | big | It can be automated for some RAW formats, if batch processing tools exist for these formats. If they do not exist, manual actions are necessary, e.g. in the manufacturer's software supplied with the camera. | long-term data archiving | Basic format for long-term data archiving, preserved in parallel to RAW format. In case an error occurs during the transformation from RAW to MASTER, MASTER files can be restored from RAW. |

| MASTER CORRECTED | MASTER file subjected to necessary corrections (e.g. straightening, cropping), still saved in lossless form. | most often TIFF | big | Depending on the type of corrections, this may be a manual or partially automated operation. | long-term data archiving limited sharing of sample files |

This is the base form for generating further formats for sharing purposes. It contains the file in a usable form (after processing), in the highest possible quality. If it turns out that an error occurred during the corrections of the MASTER file, you can always go back to the clean MASTER form and repeat the corrections. |

| PRESENTATIONHI-RES | MASTER CORRECTED files converted to a format dedicated for online sharing in high resolution. Low lossy compression may be used here, but does not have to be. | E.g. TIFF (pyramidal) or JPEG2000 | big | It can be created fully automatically based on the MASTER CORRECTED file. | online sharing | Sharing such files online usually requires the use of a special protocol that allows for gradual loading of details - the standard here is the IIIF protocol. |

| PRESENTATIONLOW-RES | MASTER CORRECTED files converted to a format dedicated for online sharing in medium/low resolution - there is a loss of quality. | E.g. JPG, PDF, PNG | small | It can be created fully automatically based on the MASTER CORRECTED file. | online and offline sharing (download) | Sharing by simply displaying on web pages or downloading files from the site's pages. |

| Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Converter | console or internet application | A tool for automatic formatting of Excel files in the form of a web application. Its existence is based on the assumption that there is previously digitized data that requires adaptation to the new format. Its task is to convert input files into files compliant with the metadata specification using specific configurations (sets of rules) allowing for optional editing of input data |

| Form | spreadsheet | The basis for proper preparation of input data is compliance with the metadata specification. This is also intended to automate the processing processes by the developed applications. In order to avoid inconsistencies between the data filled in (often by different people), a form in the form of a spreadsheet file was prepared. It contains all the columns in accordance with the metadata specification, divided into sheets for taxa, samples, iconography and bibliography. |

| Validator | console or internet application | A tool for validating spreadsheet files available as a web application. Its task is to check the presence and correctness of filling in the appropriate sheets in the file. The tool returns a report with errors and details of their occurrence, divided into each detected sheet. |

| Aggregator | console application | A program used to combine spreadsheet files that are compliant with the metadata description. It is used in the digitization process, mainly at the stage of describing records by the georeferencing team or the translation team. |

| Reporter | console application | A program used to summarize the number of records in spreadsheet files that are compliant with the AMUNATCOLL description. It is mostly used by project coordinators for the purpose of ongoing monitoring of the progress of digitization work. |

| Level | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | specimen made public | information about the specimen (record) is not protected, full information is available to all logged in and non-logged in users |

| 1 | specimen made public with restrictions | information about the specimen (record) is partially protected - sensitive data (e.g. geographical coordinates, habitat) is protected |

| 2 | specimen is restricted | information about the specimen (record) is made available only to external and internal users verified in terms of competence |

| 3 | non-public specimen | information about the specimen (record) is made available only to authorized internal users (e.g. selected from among the employees of the hosting institution) |

| Classification of specimens | Number of specimens | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of specimens | 2.25 million | ||

| Botanical collections (algae and plants) | approx. 500 thousand | ||

| Included nomenclatural types | approx. 350 | ||

| Mycological collections (fungi and lichens) | approx. 50 thousand | ||

| Zoological collections | approx. 1.7 million | ||

| Included nomenclatural types | over 1000 | ||

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Broken Access Control | Access controls implement policies designed to restrict users from operating beyond their designated permissions. When these controls fail, it often leads to unauthorized information disclosure, alteration or destruction of data, or the execution of business functions that exceed the user's authorized limits. |

| Cryptographic Failures | It emphasizes the importance of safeguarding data both during transmission and while stored. Sensitive information, including passwords, credit card details, personal data, and proprietary information, necessitates enhanced security measures, particularly when such data falls under privacy laws like the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) or financial data protection standards such as the PCI Data Security Standard (PCI DSS). |

| Injection | This vulnerability arises from the absence of verification for user-provided data, specifically the lack of filtering or sanitization measures. It pertains to the use of non-parameterized, context-sensitive calls that are executed directly within the interpreter. Additionally, it encompasses the utilization of malicious data, such as that found in SQL queries, dynamic queries, commands, or stored procedures. |

| Insecure Design | A broad category representing various weaknesses, expressed as "missing or ineffective control design." Design flaws and implementation flaws must be distinguished for some reason, and have different root causes and remedies. A secure design may still have implementation flaws that lead to exploitable vulnerabilities. An insecure design cannot be fixed by a perfect implementation, because by definition, the necessary security controls were never designed to defend against the specific attacks. |

| Security Misconfiguration | The application stack may be susceptible to attacks due to insufficient hardening or improper configuration of various services, such as enabling unnecessary ports, services, pages, accounts, or permissions. Additionally, error handling mechanisms may disclose excessive information, including stack traces or other overly detailed error messages. Furthermore, the most recent security features may either be disabled or incorrectly configured. The server might fail to transmit security headers or directives, or it may not be configured with secure values. |

| Vulnerable and Outdated Components | Lastly, the software could be outdated or contain vulnerabilities. The scope encompasses the operating system, web or application server, database management system, applications, APIs, and all associated components, runtimes, and libraries. It is essential that the underlying platform is consistently patched and updated, and software developers must verify the compatibility of any updated, enhanced, or patched libraries. |

| Identification and Authentication Failures | To protect against authentication attacks, user identity confirmation, authentication, and session management are key. Frequently, vulnerabilities arise from automated attacks wherein the perpetrator possesses a compilation of legitimate usernames and passwords. Additionally, breaches can occur due to inadequate or ineffective credential recovery methods, forgotten passwords, and the transmission of passwords in plaintext or through poorly hashed password storage systems. The absence or ineffectiveness of multi-factor authentication further exacerbates these risks. Moreover, there may be instances of improper invalidation of session identifiers or the exposure of session identifiers within URLs. |

| Software and Data Integrity Failures | Software and data integrity failures pertain to code and infrastructure that do not adequately safeguard against breaches of integrity. It is impermissible for an application to depend on plugins, libraries, or modules sourced from unverified origins. A frequent method for exploiting vulnerabilities is through the auto-update feature, which allows updates to be downloaded and implemented on a previously trusted application without adequate integrity checks. |

| Security Logging and Monitoring Failures | Logging and monitoring service activity helps detect, escalate, and respond to active breaches. Events such as logins, failed logins, and high-value transactions should be audited. Warnings and errors should generate clear log messages when they occur, and they themselves should be monitored for suspicious activity. Alert thresholds and response escalation processes should be defined at the appropriate level, and information about their exceedance should be provided in real or near real time. |

| Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) | An SSRF vulnerability arises when a web application retrieves a remote resource without validating the URL supplied by the user. This allows an attacker to manipulate the server-side application into directing the request to an unintended destination. Such vulnerabilities can impact services that are exclusively internal to the organization's infrastructure, in addition to any external systems. Consequently, this may lead to the exposure of sensitive information, including authorization credentials. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).