1. Introduction

The increasing global demand for energy, coupled with the urgent need to address climate change and enhance energy security, has accelerated the transition toward renewable energy sources [Olabi, A. 2022]. Among these sources, bioenergy—primarily derived from biomass—plays a crucial role. It is utilized for generating heat and electricity, serving as transportation fuel, and producing industrial products [Reid, W.2020]. As economic development and global population growth continue, waste generation has risen significantly, highlighting the need for rational utilization strategies. Sustainable waste management is vital for achieving the goals of the circular economy [Kilibarda et al., 2023]. Processes that convert suitable waste materials into energy provide a viable means for energy recovery, complementing existing waste management systems. Energy derived from waste can be harnessed for various applications, including electricity generation, process steam for industrial consumers, hot water, and district heating or cooling. In the European Union, energy recovery from waste is a fundamental component of waste management systems, supported by advanced technologies that minimize health and environmental risks. The growing bioenergy industry is integral to the European Green Deal framework, which aims to establish a sustainable and climate-neutral economy in Europe [Liobikienė, G., 2023]. As a renewable energy source, bioenergy is transforming the continent's energy landscape and significantly reducing its carbon footprint, promoting climate protection while enhancing economic growth.

Europe’s strong commitment to renewable energy and sustainable waste management makes it a global leader in biogas production [Pavičić J, 2022], with output reaching around 20 billion cubic meters in 2020. The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union provides a legal framework for environmental protection, including waste management and energy recovery, ensuring compliance among member states. Additionally, European countries are actively investing in research and innovation to improve the efficiency and sustainability of biogas production [Piwowar, A.; 2022; Eder, A. 2018]. The bioenergy sector also contributes to job creation, with biomass energy supporting approximately 779,000 jobs during the 2021/2022 period, including about 354,000 positions in the EU. This employment growth is particularly beneficial for rural areas, where promoting bioenergy initiatives fosters economic development [Singh, A. 2023; Simionescu, M.,2020]. By incorporating bioenergy into Europe’s energy mix, the European Green Deal enhances energy security and encourages sustainable practices, contributing to a greener and more resilient economy. Furthermore, sustainable biomass fuel production aligns with the United Nations' focus on climate protection and supports Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7, which aims to provide affordable and clean energy [Kothari, R., 2023, Habermann, H.; 2011]. Biogas stands out as a sustainable and versatile alternative for energy production and effective waste management. Generated through the anaerobic digestion of organic matter, biogas is primarily composed of methane and carbon dioxide. This process not only produces electricity and heat through combined heat and power (CHP) systems but also addresses challenges related to organic waste disposal.

In the Republic of Serbia, waste management is governed by regulations [LAW, 2016; 2018; Regulation 2010] that have been aligned with European Union standards, focusing on a waste management hierarchy that prioritizes waste prevention. When waste generation cannot be prevented, it is essential to ensure conditions for reuse, recycling, energy recovery, and processing. Only after these steps can the remaining waste be safely landfilled in an environmentally friendly manner. Effective waste management technologies, particularly those for energy recovery, are relatively new in Serbia. These technologies aim to provide solutions that address environmental protection and mitigate emissions into air, water, and soil, while also considering human health impacts. Energy recovery from waste is one of the most strictly regulated industrial sectors in the EU, with stringent monitoring of pollutants and lower threshold values compared to other sectors.

Unfortunately, a significant portion of waste in Serbia ends up in unsanitary and illegal landfills, leading to environmental pollution and threats to public health. The lack of proper waste treatment and disposal conditions often results in frequent fires, exacerbating public health risks and long-term environmental degradation. The increasing demand for energy, coupled with rising costs and decreasing availability, motivates both public and private sectors to consider investments in energy recovery facilities. Public participation is essential to ensure compliance with regulations and to guarantee timely information dissemination from relevant authorities. If these conditions are met, there is potential for Serbia’s waste management system to evolve into a sustainable model aligned with practices in developed countries, thus mitigating negative impacts.

This study aims to investigate the biogas production potential of various substrates, specifically focusing on animal manure, energy crops, food industry waste, and slaughterhouse waste. Data for this research were obtained from a comprehensive review of scientific and scholarly literature from global databases. We will analyze the biogas and methane yields per unit of fresh, dry, and organic dry matter, examining how the characteristics of these substrates influence their biogas production potential. Additionally, we will evaluate the implications of our findings for optimizing substrate selection and biogas plant design within the specified geographic context and analyze all aspects (Environmental, Economic, Technological, and Social) of the current manure management practices concerning their potential integration into sustainable biogas production systems. The primary focus of this research is on measuring methane yield and biogas production volume, while intentionally excluding detailed engineering aspects of biogas plant design and long-term economic modeling.

2. From Waste to Energy: The Significance of Substrate Selection

The term "substrate" refers to the raw materials used in biogas production. When multiple substrates are combined, the less-utilized material is referred to as a co-substrate. Assessing the availability, cost, and biochemical properties of potential substrates is crucial, as these factors significantly influence the design, operational efficiency, and economic feasibility of biogas plants [Cvetković, S., 2014; Divya, D., 2020].

The first step in assessing the potential for biogas production is the qualitative and quantitative determination of available feedstock for anaerobic digestion. Based on data regarding feedstock for anaerobic digestion, further calculations are performed to estimate the potential biogas yield using literature data or experimental findings on biogas production from the considered raw materials.

All types of biomass available within the local government area of the city of Čačak can be utilized for anaerobic digestion in biogas production. According to the 2022 Agricultural Census [AFFD, 2022], the available feedstock includes:

Manure from livestock farms,

Agricultural production residues,

Biodegradable organic waste from the food industry and similar sectors,

The biodegradable fraction of municipal waste and waste from the hospitality sector (food waste),

Wastewater from the food industry and sewage sludge from wastewater treatment plants,

Energy crops (corn silage, sorghum, various grass species).

For the analysis of the utilization potential of available feedstock for biogas production within the local government area of the city of Čačak, data will be used on agricultural crops, waste streams from livestock and poultry production, municipal waste, and designated energy crop production (corn silage).

The energy potential structure of the analyzed available feedstock is as follows:

The biogas yield from a specific substrate is considered potential; however, the actual amount produced in a biogas plant depends on operational conditions and process stability [Martinov, M., 2020]. Therefore, analyzing the characteristics of substrates is essential for determining their potential for biogas production and informing the design of the biogas plant.

In our upcoming discussion, this study aims to provide practical recommendations for enhancing the efficiency and sustainability of biogas production through the strategic use of substrates. By conducting a comprehensive literature review and experimental methodology, we will examine how different substrate characteristics can affect biogas yields and guide best practices that can be applied in various countries around the world.

2.1. Manure from Livestock Farms

Manure from livestock farms represent a suitable feedstock for biogas production, as they not only contain organic matter but also harbor anaerobic bacteria that can facilitate the initiation of the anaerobic digestion process. There is a strong and stable manure. The liquid consists of animal waste and can be transported by pumps and pipelines to the biogas facility. According to agricultural practices in Serbia, farmers typically collect animal manure in lagoons or storage tanks. Due to the nature of husbandry practices, manure from sheep and goats is challenging to collect and utilize for biogas production.

For the territory of the city of Čačak, based on data from the 2022 Agricultural Census [AFFD, 2022], an analysis of livestock herd sizes indicates that approximately 3,500 agricultural holdings raise cattle. The majority of cattle are found in the herd size categories of 1–2 animals (approximately 3,000) and 3–9 animals (approximately 5,500). Pigs are raised on 5,800 agricultural holdings, with the highest numbers in the categories of 10–19 animals (approximately 11,500) and 20–49 animals (approximately 10,000). Sheep are raised on 3,400 agricultural holdings, predominantly in the categories of 3–9 animals (approximately 11,500) and 10–19 animals (approximately 10,500).

Poultry farming is recorded on 6,453 agricultural holdings, with the highest poultry numbers found in the category of approximately 5,000 birds per holding. Additionally, around 100,000 birds are raised on five agricultural holdings, while a significant number of holdings fall within the category of 1–49 birds per farm.

The data presented in the tables 1-3 provide insights into the characteristics and potential of various manure types and substrates for biogas production. Together, these data emphasize the importance of substrate selection and composition in optimizing biogas production.

Table 1 displays the dry matter and organic dry matter content for two liquid manure types: bovine and pig. Additionally, it includes three solid manure types from cattle, pigs, and poultry, providing percentages for both dry matter and organic dry matter across these various manures. The data indicates that:

- Liquid manures from beef and pork contain lower dry matter content (8-11% and 7%, respectively) but have a high percentage of organic matter (75-86%).

-Solid manures: Solid cattle and pig manures have higher dry matter percentages (25% and 20-25%, respectively) than liquid forms, indicating a greater potential for solid substrates in biogas production due to their higher organic content.

The yield of biogas is determined by the amount of fresh, dry, or organic dry matter present in a substrate [Nwokolo, 2020; Seadi, T, 2008]. This directly impacts biogas potential. Substrates with a dry matter content of less than 20% are used for "wet digestion," and this includes manure [Cveković, S, 2016].

Based on

Table 1, it is evident that manure has relatively low potential methane production per unit of organic dry matter [Kafle & Kim, 2013; Cveković, S.2016]. This yield depends on the composition; for instance, liquid manure from cattle predominantly contains carbohydrates, whereas liquid manure from pigs is rich in proteins, which results in a higher methane content [Weiland, 2010].

Table 2 presents valuable information regarding the biogas yields (in Stm³/t) and the methane (CH

4) content for different manure types. Key findings include:

- Solid poultry manure produces the highest biogas volume, ranging from 70 to 90 Stm³/t of fresh matter, while consistently maintaining a methane content of approximately 60%.

- Solid pig manure also demonstrates notable performance, yielding between 55 and 65 Stm³/t, highlighting its suitability as an effective substrate for biogas production.

The biogas yield in bovine liquid manure ranges from 20 to 30 m3, which is slightly lower than that of pig liquid manure, which ranges from 20 to 35 per ton of fresh matter (

Table 2) [Angelidaki, I., 2003, Zhang, J. 2017]

Table 3 presents the potential methane yields from organic dry matter across different types of manure. The results show that:

- Poultry manure exhibits the highest average methane yield at 280 Nm³/t of organic dry matter. This is closely followed by both pork liquid manure and solid beef manure, each yielding 250 Nm³/t, demonstrating their considerable effectiveness in methane generation.

The water content of manure is high, ranging from 68% to 93%, which reduces its energy potential. However, this moisture is beneficial when combined with other substrates that have higher dry matter contents, such as corn silage. When comparing manure to corn silage, manure can yield up to ten times less biogas per unit weight. This means that for the same size biogas plant, ten times more manure is required than corn silage [Martinov, M, 2020]. Therefore, for a plant with a nominal electrical capacity of 150 kW, at least 1,000 conditional head of cattle would be necessary, as one conditional head of cattle, weighing 500 kg, generates only 0.11 to 0.15 kWe [Martinov, M 2020]. Economic analysis indicates that constructing and operating larger plants, with a nominal electrical capacity of 500 to 1,000 kW, is more cost-effective [Martinov, M, 2020]. Consequently, modern plants utilize a mix of manure and other substrates, such as energy crops.

2.2 Energy plants

Energy crops serve not only as co-substrates but also as the primary raw material in biogas plants. These energy plants are specifically cultivated biomass, which is usually ensiled for storage [Rostocki et al., 2024]. The most commonly utilized options include corn silage, silage from whole grain plants like rye, and various cereal types or their mixtures, alongside cereal grains, grass silage, beet silage (either fodder or sugar), and sugar beet leaves [Levavasseur et al., 2022]. Beyond using the entire plant as corn silage, popular forms include silage made from corn cobs and husks, a mixture of grain and cobs, as well as grain corn focusing solely on cobs.

The data presented in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 provide valuable information regarding energy proteins and energy crops in the context of biogas production.

The dry matter and organic dry matter content of these various energy crops is detailed in

Table 4. This table highlights the composition of energy proteins, which can influence their suitability as substrates for biogas production.

The percentage of dry matter is highest in grass silage at 50%, while it is lowest in sugar beet leaf at 16%. The percentage of organic dry matter is highest for rye and whole plant silage at 98%, with the lowest for grass silage at 70%. We hypothesize that substrates with higher organic dry matter content and an optimal balance of carbohydrates and proteins will yield significantly greater volumes of biogas and methane compared to those with lower organic dry matter content. Energy crops and silages with a dry matter content of about 35% or more are commonly used in a type of anaerobic digestion known as "dry digestion." A dry matter content of less than 28% in maize can lead to the occurrence of leachate, resulting in significant energy losses [Kothari, R, 2014]. For silage of whole cereal plants, harvesting should occur when dry matter yields are highest (in a monoculture system), which is at the end of milky ripeness or the beginning of waxy ripeness [Kothari, R., 2014]. In grass silage, it is crucial that the dry matter content does not exceed 35%, as this increases the proportion of lignin and fiber, leading to a decrease in methane yield compared to organic dry matter [Kothari, R., 2014].

Table 5 outlines the potential yields of methane-containing biogas from different types of energy crops. This table shows the possible biogas yields rich in methane from various energy crops, offering insights into their efficiency as substrates for biogas production. Key points include:

- Sugar beet shows high biogas yields (170-180 Stm³/t) and high methane content (around 53%).

- Corn silage also demonstrates significant potential with yields of 170-200 Stm³/t, indicating its effectiveness as a substrate.

Table 6 illustrates the potential yield of methane from organic dry matter across various types of energy plants, comparing their efficiency in converting organic matter into methane. This comparison highlights the significant contributions different energy plants can make to biogas production.

- Cereal grains offer the highest yield potential at 380 Nm³/t, while corn silage also ranks favorably at 340 Nm³/t, underscoring their efficiency in methane generation.

Cereal grains are used as a supplement to existing substrates, where the type of grain is not important, and they are particularly well-suited for precise management of biogas production [Hutňan, M.2010, Senghor, A.2017]. Due to their favorable energy yields per hectare and fermentation properties, maize is particularly well-suited for biogas production [Hutňan, M, 2010]. From one ton of corn silage, 350 to 400 kWh is obtained [Martinov, M, 2020]. For a plant with a nominal power of 500 kWe, 170 to 250 acres would be required for maize silage production. In countries with favorable feed-in tariffs, the share of biogas produced from silage ranges from 30% to 100% [Martinov, M, 2020].

Collectively, tables 4, 5 and 6 emphasize the significance of both energy protein and energy crop selection in optimizing methane production for biogas applications.

2.3. Organic Waste of the Food Industry

Organic waste from the food industry is generated in various processes, such as the production of sugar, alcohol, oil, beer, and the processing of fruits and vegetables [Morales-Polo, C. 2021]. These substances are produced during the processing of plants, essentially the constituent parts of plants [Wang, L. J. 2013]. Pomace, a by-product, forms during the processing of grapes and fruits into wine and fruit juices [Soja, J., 2024], it is also produced when alcohol is made from cereals, beets, potatoes, or fruit [Nair, L. G., 2022]. In the production of beer, it appears as a secondary product known as beer trop. Sugar production generates sugar beet noodles as a by-product. Molasses and beet noodles, due to their residual sugar content, serve as suitable substrates for biogas production [FNR, 2016]. While the potential uses of these by-products are uncertain, their high biogas yield makes them appropriate as substrates or co-substrates for biogas production. This holds true for by-products from alcohol production, which yield biogas comparable to manure [Martinov, M.,2020].

According to data from the 2022 Agricultural Census [Source: Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, 2022], the most widely cultivated fruit species in the Čačak region is plum, with approximately 690,000 trees across the city’s territory. Other fruit species under cultivation include apple (approximately 656,000 trees), pear (approximately 205,000 trees), and apricot (approximately 187,000 trees). The number of cherry, peach, and sour cherry trees ranges between 25,000 and 50,000, while walnut, quince, and hazelnut are less represented.

Vegetable production within the local administrative area of Čačak, both in open fields and protected environments, is organized either as garden-scale production or for commercial market purposes. The cultivation of major arable crops occupies a total area of 10,932.26 hectares, representing 37.21% of the total agricultural land available to farmers. The predominant crop is maize, covering 5,099.97 hectares (46.64%), followed by wheat with 2,604.57 hectares (23.82%), potato with 1,465.21 hectares (13.40%), barley with 1,184.34 hectares (10.84%), and oat with 578.34 hectares (5.29%).

According to the 2022 Census, out of 1,795 agricultural holdings engaged in primary agricultural production, a total of 921 hectares are dedicated to vegetable crops, including tomatoes, cabbage and kale, peppers, onions (both red and white), cauliflower, carrots, peas, and other fresh vegetables, as well as melons and strawberries.

The production of major arable crops (maize, wheat, potato, barley, and oat) covers approximately 11,000 hectares within the city of Čačak, accounting for 37.21% of the total agricultural land available to producers. In terms of orchard production, significant agricultural residues could be utilized for biogas production. Based on data from the 2022 Agricultural Census, orchards cover approximately 4,200 hectares, while vineyards occupy around 30 hectares. The largest orchard area is under plum cultivation (approximately 2,000 hectares), whereas the smallest area is allocated to other berry fruits (approximately 5 hectares). These agricultural residues represent a viable raw material source for biogas production.

Table 7 and

Table 8, and 9 provide comprehensive data on organic waste from the food industry and its potential for biogas production, detailing various aspects critical to understanding its viability as a substrate.

Table 7 shows the percentages of dry matter and organic dry matter for different types of organic waste produced by the food industry. This information reveals the composition of each waste type, highlighting the relative amounts of dry matter and organic content, which are essential factors influencing the efficiency of biogas production. Notable observations include:

- Molasses has a high dry matter content of 80-90% and a significant organic matter percentage of 85-90%, emphasizing its potential as a valuable substrate for biogas production.

The potential yield of methane is a key criterion for evaluating the various substrates suitable for use in biogas plants during anaerobic digestion [Seadi, T, 2008, Weiland, 2010, Piekutin, J., 2021].

Table 8 presents biogas yields and methane content for various types of organic waste from the food industry. This table quantifies the expected biogas production potential for each waste category, emphasizing which types may be most effective for generating methane and contributing to renewable energy sources.

Stm³/t of Fresh Matter:

- This metric indicates the total volume of biogas produced per ton of fresh organic waste. It includes all components in the waste, regardless of their dry matter content. For example, molasses yields between 290 and 340 Stm³/t of fresh matter, which illustrates its potential to produce significant amounts of biogas due to its high organic content.

Stm³/t of Organic Dry Matter:

- This metric focuses on the biogas yield relative to the organic dry matter present in the waste. It provides a more accurate measure of the substrate's effectiveness for biogas production because it accounts only for the decomposable organic components. In the case of molasses, the high organic dry matter percentage contributes to its strong yield, making it an efficient substrate for anaerobic digestion.

Examining both metrics reveals how various types of organic waste differ in their potential for biogas production, which is shaped by their composition and moisture levels. This combined analysis enhances understanding of which substrates could be more effective for maximizing biogas yields.

Other potential substrates (beet pulp, cereal pomace, potato, fruit, brewer's pulp) have a significantly lower potential biogas yield per ton of fresh mass; for example, beer pomace can yield up to 130 m³, while beet pulp can yield up to 75 m³. However, the highest potential yield of biogas per ton of organic dry matter comes from beer pomace at 750 m³, followed by cereal and potato pomace at 700 m³ and fruit pomace at 600 m³, with methane content reaching up to 75% (

Table 8).

Table 9 details the methane yield from organic dry matter for different substrates derived from the food industry. By comparing the efficiency of methane production across these substrates, this table identifies the most promising options for maximizing biogas yield. The highest mean value for potential methane yield per ton of organic dry matter is found in apple pomace at 453 m³, followed closely by grape pomace at 448 m³ and rapeseed cake at 396 m³ (

Table 9).

2.4 Organic Waste from the Animal Food Production Industry

Waste raw materials from the meat processing and dairy industries represent valuable feedstocks for biogas production in anaerobic digestion facilities due to their high concentrations of organic matter, particularly proteins and fats. Waste generated from the meat processing industry arises from industrial operations such as slaughterhouses, meat processing plants, and related facilities.

The European Union Regulation classifies waste generated by the slaughterhouse industry into three categories: (high, medium and low risk) [Regulation (EC) No 1069/2009]. Based on these categories, the requirements for disposal are also defined [Martinov, M.,2020]. One of the technologies for collecting this waste is biogas technology. Slaughter waste from categories medium and low risk is primarily used as a substrate for producing rich meat [Martinov, M.,2020]. The legal framework for biogas production from animal waste, including deceased animals, was adopted in 2011 and is fully aligned with EU regulations [Regulation on Animal Waste, 2011]. The implementation of biogas technology in facilities generating this type of waste provides an effective solution for waste disposal while also offering an opportunity for these facilities to receive compensation for the waste delivered to biogas plants for treatment.

Biogas plants that utilize organic waste from the slaughterhouse industry typically include a system for shredding and homogenizing slaughterhouse waste [Martinov, M.,2020]. Depending on the condition and classification of the substrate, processing in special tanks is required for a specific period of time at certain temperature and pressure before anaerobic digestion in a fermenter. The typical biogas yield from waste streams in the meat processing industry ranges between 225 and 978 m³ of methane per ton of organic dry matter derived from meat processing waste [Pitk et al., 2012; Hejnfelt & Angelidaki, 2009].

Additionally, wastewater and waste from dairy processing, such as whey and off-specification products, are biodegradable and represent an optimal feedstock for biological treatment aimed at biogas production.

2.5. Municipal and Wastewater of the Food Industry

Municipal wastewater, or household wastewater, originates from residential areas and results primarily from human metabolism and household activities [Bachmann, N., 2015]. Wastewater generated in the food industry, on the other hand, stems from the production process [Ounsaneha, W., 2021]. Municipal wastewater and that generated in the food industry are often discharged directly into watercourses and lakes, which negatively impacts the environment. Consequently, wastewater must be treated; thus, the methods and conditions for discharging wastewater into recipients are defined to prevent environmental pollution [Jin, Y., 2015; Law on Water, 2018]. Before being discharged to the recipient, wastewater undergoes treatment through physical, biological, and chemical processes [Patel, A., 2021]. Wastewater treatment yields sludge, which can be either treated or untreated residue remaining after the treatment process. One of the challenges is the proper disposal of sewage sludge, ensuring it is managed in a manner that does not threaten the environment or human health. With an anaerobic process, organic stabilization and hygienization of waste sludge can be achieved [Martinov, M.,2020]. After anaerobic digestion, if the analyses indicate it, the waste sludge can be safely disposed of in a landfill or used on agricultural land [Martinov, M.,2020]. The dry matter percentage in the sludge reaches up to 5 percent, whereas municipal and wastewater from the food industry generally contain a low proportion of dry matter, sometimes less than 1%, meaning they have a water content, which impacts the size of the biogas plant [Martinov, M.,2020]. Biogas plants that use wastewater as a substrate for biogas production are primarily part of the wastewater treatment system; by generating electricity from biogas, they partially meet their energy needs [Martinov, M.,2020].

2.6. Municipal Solid Organic Waste

Besides solid biofuels, municipal and industrial waste also play a crucial role in the worldwide bioenergy landscape, contributing about 21.4 gigawatts to the total. Municipal solid organic waste consists of biodegradable materials suitable for anaerobic digestion, including waste from gardens, parks, food, and household kitchen scraps, as well as waste from restaurants and catering services involved in maintaining green areas [Pavi, S., 2017]. This type of waste is characterized by a heterogeneous composition and inconsistency, which necessitates primary waste separation. As urban areas continue to face increasing waste volumes, utilizing waste for energy production has become increasingly significant [Buraimoh, O. M., 2020]. The global waste-to-energy market was valued at USD 34.50 billion in 2023 and is expected to expand from USD 35.84 billion in 2024 to USD 50.92 billion by 2032, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.5% during the forecast period [Sobczak A, 2022]. In 2023, the Asia-Pacific region led the waste-to-energy market, holding a market share of 47.24%.

Over the past few decades, energy generation from solid biomass in Europe has significantly risen, reaching a peak of over 100 million metric tons of oil equivalent in 2021 [Honcharuk, I. 2023]. The biomass resources utilized for energy include various materials. Often, wood from trees and forest debris is used in the form of logs, chips, or pellets; energy crops are cultivated specifically for their high yield and energy content; and biogas can also be produced from livestock manure. Additionally, the bioenergy sector exploits waste products to generate energy, such as landfill gas, solid municipal waste, and sewage sludge. Within the European Union (EU), biomass plays a crucial role in the renewable energy landscape. In 2022, it contributed 169.4 terawatt hours of electricity, making it the third-largest source of renewable energy in the region, after wind and hydroelectric power.

Biogas plants utilizing this waste must be equipped to separate large impurities and metals, along with having devices for shredding the substrate. In terms of dry matter content, it significantly exceeds that of manure and is comparable to energy crops. Consequently, the estimated yield of biogas from this substrate is approximately 100 m³ per ton. In contrast, the potential methane yield from one ton of organic dry matter from green waste is 369 m³ (table 10).

Table 10 indicates that green waste has a potential yield of methane from organic dry matter of 369 Nm³/t of organic solid matter (oSM). This information is significant in the context of municipal solid organic waste (MSOW) for several reasons:1. High Methane Potential: The value of 369 Nm³/t suggests that green waste is an effective substrate for biogas production. This makes it a valuable component of municipal organic waste management strategies, as it can contribute significantly to methane generation through anaerobic digestion. 2. Waste Management: Utilizing green waste for biogas production helps reduce the volume of organic waste that would otherwise end up in landfills. This aligns with sustainable waste management practices and can mitigate greenhouse gas emissions associated with waste decomposition in landfills. 3. Resource Recovery: The high methane yield from green waste indicates an opportunity for municipalities to recover energy from organic waste. This can support local energy needs and contribute to renewable energy targets. 4. Integration with Other Substrates: In the context of municipal solid organic waste, green waste can be co-digested with other organic materials (like food waste) to optimize biogas production, leveraging the complementary characteristics of different substrates.

The construction of a biogas plant that uses this type of substrate would not only solve the issue of disposing of municipal biodegradable waste but also generate revenue from producing electricity and heat.

3. Optimizing Biogas Production: Case from Practice

Biogas plants are defined as small-scale facilities that generate biogas from suitable substrates, feedstocks, or biomass with sufficient energy potential [Slepetys, J., 2012; Norouzi, O.; 2022]. Biomass refers to the biodegradable fraction of products, waste, or residues of biological origin, providing a diverse range of organic materials capable of undergoing anaerobic decomposition [Mistretta, M., 2022]. During the anaerobic digestion process, biogas—primarily composed of methane and carbon dioxide—is produced. To maximize energy recovery, the biogas generated in small biogas plants is best utilized in Combined Heat and Power (CHP) systems, which enhance efficiency by simultaneously generating electricity and heat [Nazari, A., 2021].

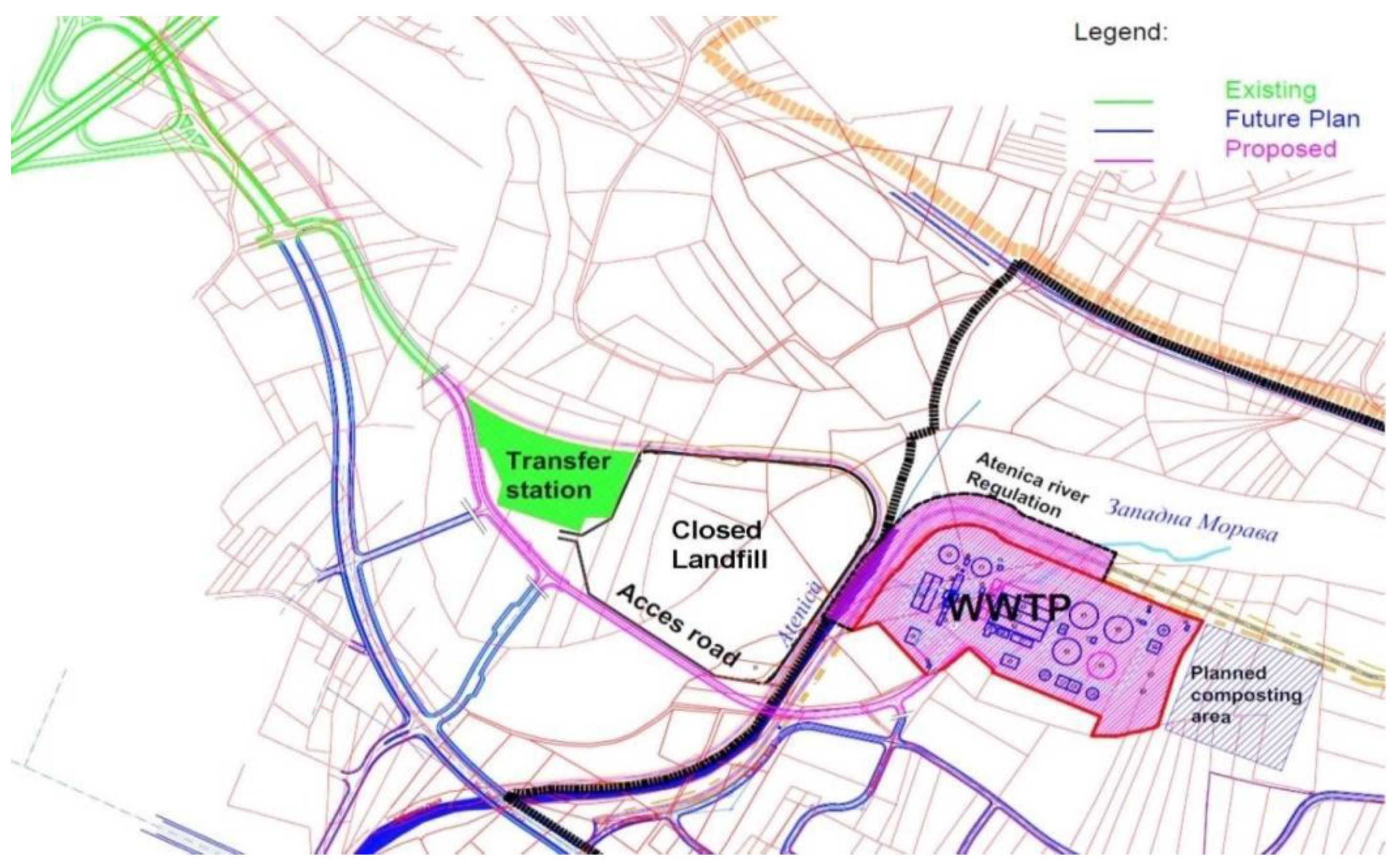

Figure 1 shows the location for wastewater treatment where in Čačak a biogas plant is to be built, and

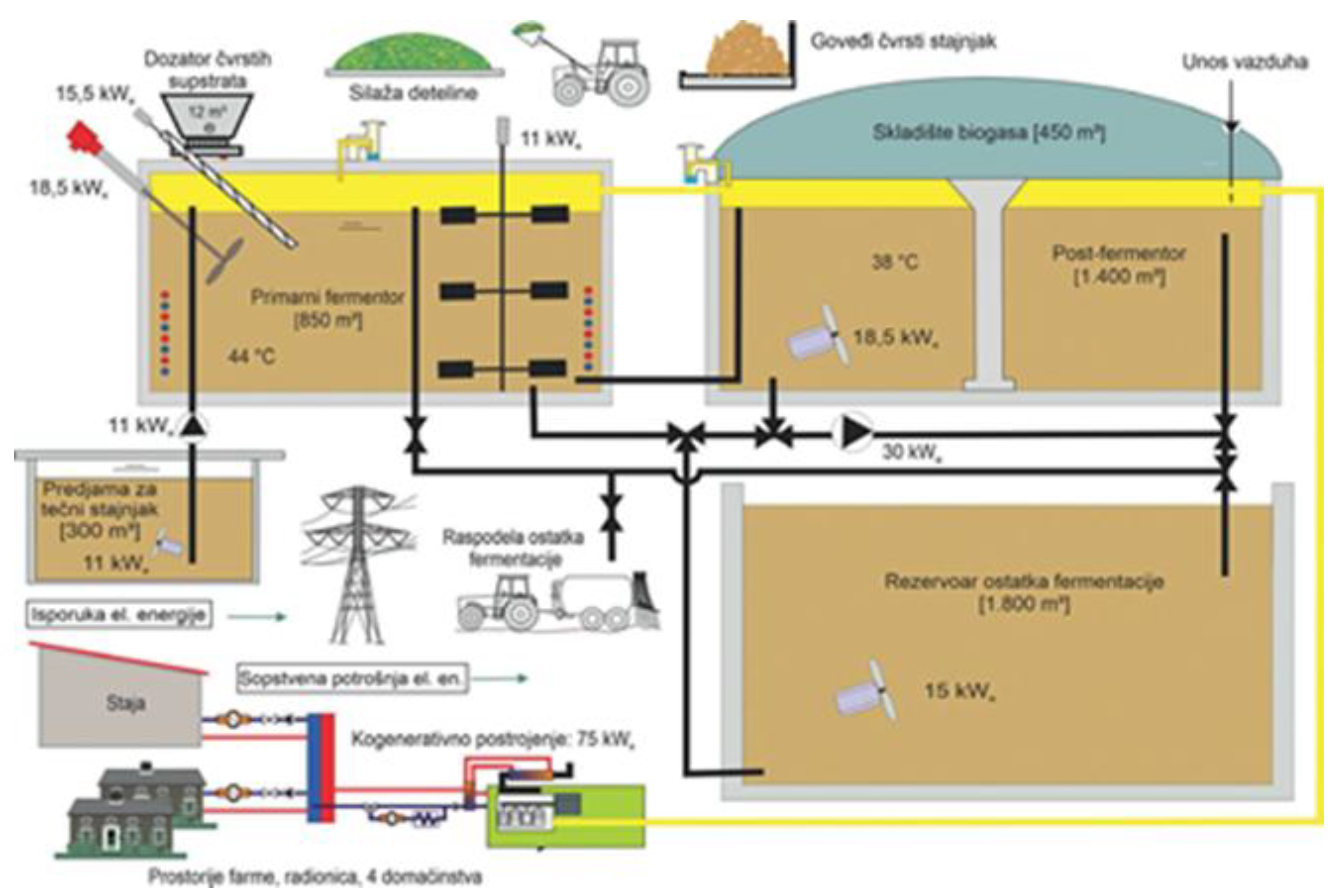

Figure 2 shows a conceptual design for the biogas plant designed for the study conducted by Čurčić et al. [2022].

The available substrates for biogas production with energy potential for biogas generation at the wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) in the area of the municipality of Čačak are presented in

Table 11. The substrate mixture comprises bovine solid manure and pig liquid manure, each representing 41% of the total substrate intake. The remainder of the substrate consists of clover silage. The daily substrate intake is approximately 15 tons, with an average dry matter content of 20%. Liquid manure is pumped from a 300 m³ pit into the fermenter, while solid substrates are introduced into the fermenter via a 12 m³ device mounted on the concrete flat roof of the fermenter.

The fermenter has a working volume of 850 m³, while the post-fermenter has a volume of 1,400 m³ with an integrated biogas storage capacity of 450 m³. The fermentors are heated to 44°C and 38°C, respectively (mesophilic mode). The average total hydraulic retention time is 150 days, which meets the legal requirement that the 1,800 m³ residual fermentation tank does not need to be covered. The cogeneration plant, equipped with a gas engine, has an installed electrical power of 75 kW and an electrical efficiency of about 37%. The total electricity output of 1,780 kWh per day is supplied to the grid. Operational needs for the biogas plants account for 10% electricity and 19% heat relative to the generated quantities. Approximately 22% of the generated heat energy is used to heat the pig barn, farm buildings, and four residential properties.

The total cost of the investment was €550,000. The average annual income is approximately €168,500, with 87% generated from electricity sales, while the remainder comes from the marketing of fermentation byproducts and the utilization of thermal energy. Annual costs are around €110,500, with 23% allocated for substrate purchases, 40% for depreciation, 31% for operating expenses, and 6% for labor costs.

Additionally, the economic implications of substrate selection are substantial. The costs associated with obtaining high-quality substrates can affect the overall viability of biogas production. Our findings suggest that while the most effective substrates may be more expensive, they could yield significant returns through enhanced methane production. Future research should focus on assessing the long-term economic benefits of employing various substrates, including the operational expenses related to maintaining optimal digestion conditions.

The findings of this study underscore the importance of substrate selection in maximizing biogas production. It reveals that the organic dry matter content is a critical factor influencing biogas yield. This is consistent with previous research by Weiland (2010), who emphasized that the substrate's composition significantly affects methane potential. In this study, the analysis shows that liquid manure varies in methane yields based on its organic matter composition. For instance, while bovine liquid manure has a higher dry matter content, pig manure contains greater overall organic dry matter, resulting in a higher methane yield. This observation aligns with Kafle & Kim (2013), who found that protein-rich substrates generally produce more methane compared to those high in carbohydrates.

Operational conditions also play a vital role in optimizing biogas production. Factors such as retention time and temperature are crucial for the efficiency of anaerobic digestion. The study highlights that methanogenesis is influenced by substrate composition, fermenter filling rate, retention time, and temperature [Obileke, K., 2021; Phillip, 2024]. Moreover, anaerobic microorganisms require specific conditions to thrive, including the absence of oxygen, adequate nutrients, consistent mixing, and a pH level between 5.5 and 8.5 [Kafle & Kim, 2013; Choudhary, A., 2020]. The anaerobic digestion process can operate under various temperature regimes, including psychrophilic (below 20°C), mesophilic (30-42°C), and thermophilic (43-55°C) conditions [Sárvári Horváth et al., 2016].

Recent research has explored strategies to enhance biogas yield, particularly through anaerobic co-digestion and process parameter optimization. Cheong et al. (2016) developed a simulation model for co-digesting food waste with sewage sludge, identifying optimal conditions for maximizing biogas production. Additionally, studies have examined volatile fatty acid (VFA) accumulation, offering insights into thermophilic anaerobic digesters [Harirchi, S., 2022]. The co-digestion of distillery wastewater with molasses and glycerol has shown promising benefits, and the feasibility of using brewery spent grain in anaerobic digestion has also been explored [Phuket, K., 2024].

Incorporating co-substrates, such as energy crops, can further enhance biogas production. For example, combining corn silage with manure has been found to increase overall biogas yield. This supports earlier research indicating that co-digestion exploits the synergistic effects of various substrates, thereby improving methane production efficiency [Mata-Alvarez et al., 2000]. The variability in biogas yield emphasizes the need for ongoing assessment of substrate combinations to identify optimal mixes for maximizing methane output.

Overall, the insights from this study contribute to a deeper understanding of biogas production dynamics. By emphasizing the importance of substrate characteristics—such as organic dry matter content and nutrient composition—alongside operational parameters like temperature and retention time, the study identifies critical opportunities for optimizing biogas technology. Future research should focus on innovative substrates, including agricultural residues and food waste, and their combinations, as well as optimizing operational conditions to fully leverage the potential of biogas technology in waste management and renewable energy production.

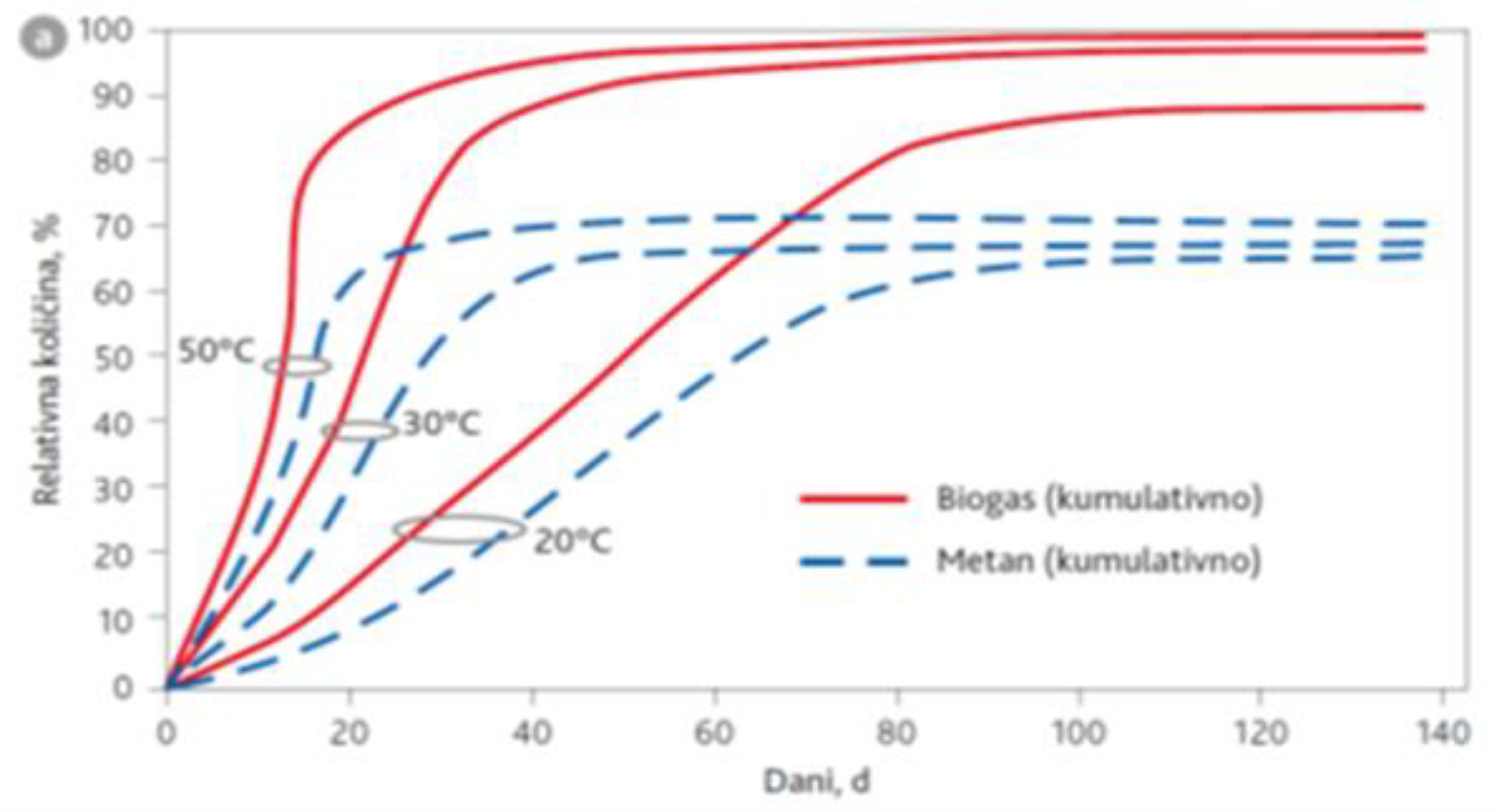

The effect of substrate retention time and temperature on the relative yield of biogas is illustrated in

Figure 3. The growth and activity of anaerobic microorganisms, or the efficiency of anaerobic digestion, is affected by the absence of oxygen, the availability of nutrients, the mixing intensity, and the presence and quantity of inhibitors [Al Seadi Teodorita, 2008, Weiland, 2010]. Along with anaerobic conditions, essential factors include a constant temperature and a pH value ranging from 5.5 to 8.5 [Kafle & Kim, 2013, Choudhary, A.,2020]. Anaerobic digestion can occur at temperatures below 20°C (psychrophilic bacteria), between 30 and 42°C (mesophilic), and from 43 to 55°C (thermophilic) [Sárvári Horváth et al., 2016].

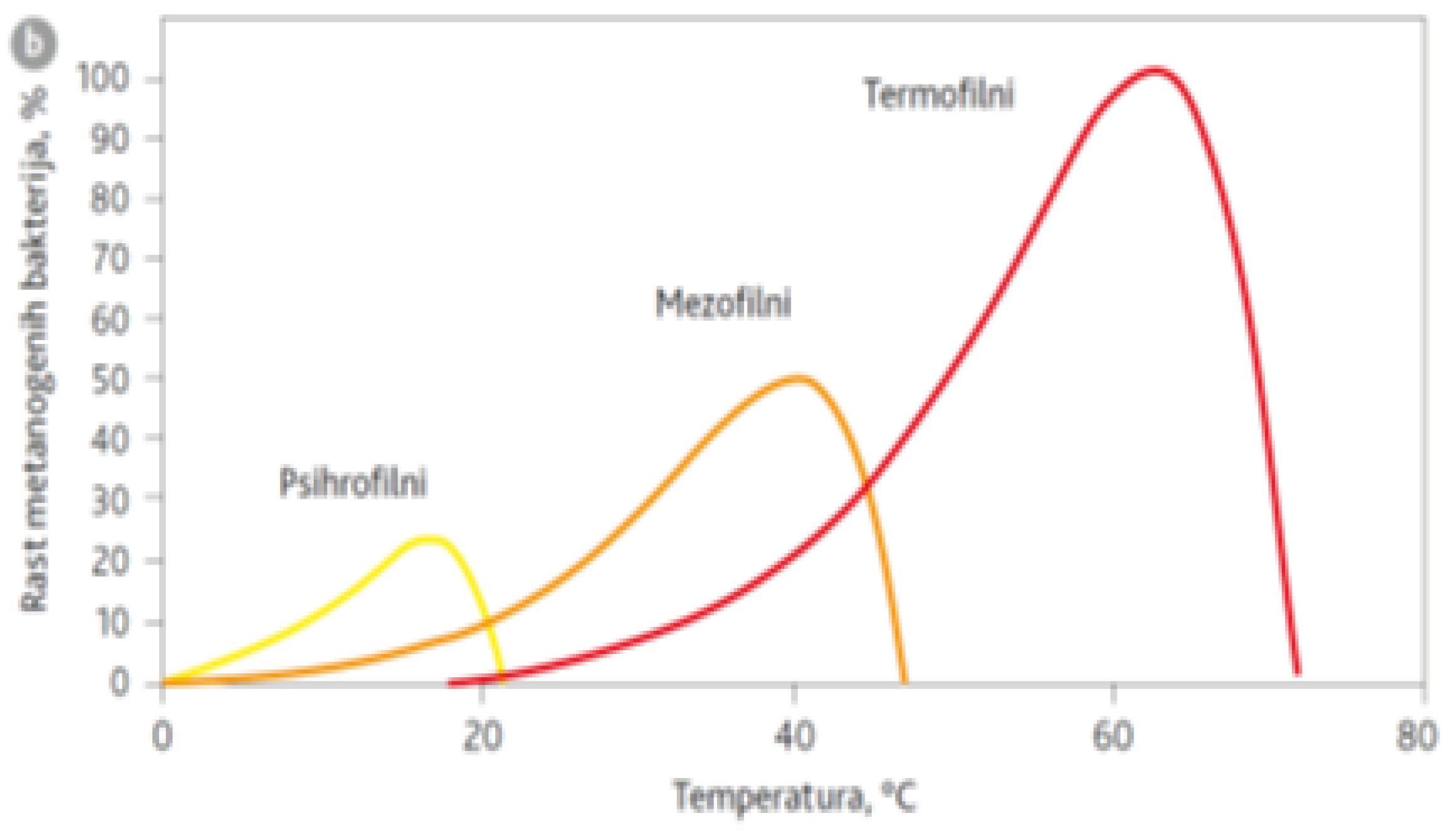

The effect of temperature regime on the growth of methanogenic bacteria is shown in

Figure 4. The minimum residence time has been shown to be between 15 to 20 days for thermophilic bacteria, 30 to 40 for mesophilic bacteria, and 70 to 80 for psychrophilic bacteria.

Specifically, the optimal temperature range for mesophilic bacteria (30-42°C) promotes a more stable digestion process, as reported by Sárvári Horváth et al. (2016). Our analysis suggests that maintaining these conditions is essential for enhancing biogas yield, reinforcing the idea that operational stability is vital for the economic viability of biogas plants.