1. Introduction

With more than 16 million sequences submitted to GISAID [

1] and other databases in the moment this manuscript was written, SARS-CoV-2 is probably the most widely sequenced pathogen in the world. Successive waves of infection have resulted in a constant selection of SARS-CoV-2 variants with new mutations in their viral genomes [2-4]. Sometimes, these novel variants carry specific mutations that have been linked to higher transmissibility [5-7] and/or immune evasion [

8,

9], making them relevant from a public health perspective [

10] and leading to their classification as variants of interest (VOI) or variants of concern (VOC) [

11].

While public health interventions, quarantine measures, and vaccination programs have been integral to the management of both past and present pandemics, the COVID-19 pandemic represents the first instance in which genomic sequencing has been deployed on an unprecedented global scale. This genomic surveillance has provided a critical advantage in pandemic response, enabling near-real-time insights into the transmission dynamics and evolutionary trajectory of SARS-CoV-2 [

12].

Spain has a decentralized health system with the competencies in healthcare transferred to the autonomous regions. In particular, Andalusia, the largest region of Spain and the third largest region in Europe, with a population of 8.5 million, equivalent to a medium-sized European country like Austria or Switzerland, has implemented over the last decades, a thoroughly digitalized health system. During the first wave of the pandemic, Andalusia established an early pilot project SARS-CoV-2 sequencing [

13], which became later the Genomic Surveillance Circuit of Andalusia [

14], in close coordination with the Spanish Health Authority [

15]. This circuit was an integral component of the strategy for Personalized Medicine during the COVID-19 pandemic [

16]. On the other hand, the Andalusian Public Health System has systematically been storing the electronic health record (EHR) data of all Andalusian patients in the Population Health Base (BPS, acronym from its Spanish name “Base Poblacional de Salud”) since 2001, making of this database one of the largest repositories of highly detailed clinical data in the world (containing longitudinal detailed clinical information on over 15 million of patients) [

17].

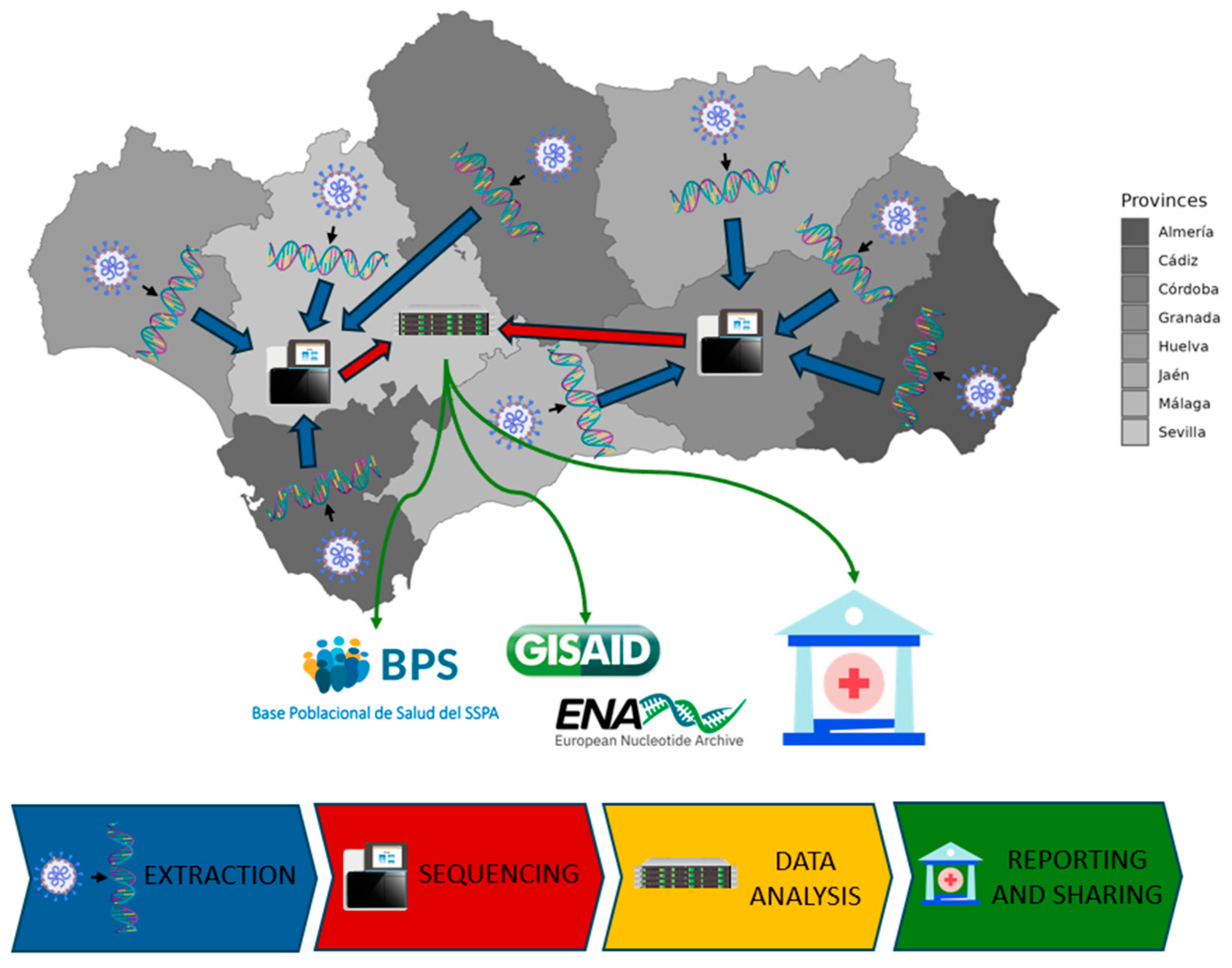

The genomic surveillance circuit is a consortium that includes the 27 main hospitals across the 8 provinces of Andalusia (

Table S1), the Platform of Computational Medicine, the General Directorate of Public Health of the Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs, and the Technical Subdirectorate of Information Management of the Andalusian Health Service.

Figure 1 sketches the general operating layout of the circuit.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and patient selection

The genomic surveillance circuit for SARS-CoV-2 in Andalucia includes 42,552 SARS-CoV-2 genomes that were systematically sequenced among PCR-positive individuals following the recommendations of the Spanish Ministry of Health [

18] in the period January 2021 to the present.

2.2. SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing

SARS-CoV-2 RNA-positive samples were subjected to whole-genome sequencing at the sequencing facilities of Hospital Universitario San Cecilio (Granada, Spain), Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío (Sevilla Spain) and Hospital Universitario Virgen de Las Nieves / Andalusian Virus Reference Laboratory (Granada, Spain).

The sequencing strategy primarily involved short-read sequencing, although long-read sequencing was applied to a subset of samples.

For short-read sequencing, RNA extraction and amplification were performed following the ARTIC network protocols [

19] using ARTIC primer set versions V3, V4, V4.1 and V5.3.2 [20-23] from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA) for Illumina sequencing over time. Briefly, overlapping amplicons spanning the SARS-CoV-2 genome were generated after cDNA synthesis using SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 1 µL of random hexamer primers, and 11 µL of RNA.

Libraries were prepared according to the COVID-19 ARTIC protocol (V3, V4, V4.1 and V.5.3.2, depending on the version) and the Illumina DNA Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Library quality was assessed using the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and libraries were subsequently quantified using the Qubit DNA BR assay (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Normalized libraries were pooled and sequenced on various Illumina platforms, including MiSeq v2 (2x150 cycles), Miniseq (2x150 cycles), iSeq (2x150 cycles), NextSeq 500/550 Mid Output v2.5 (2x150 cycles) and Nextseq 1000 (2x150 cycles) sequencing reagent kits.

For long-read sequencing, SARS-Cov-2 samples were sequenced on a MinION Mk1C platform (Oxford Nanopore, Oxford, United Kingdom) using a FLO-MIN106D flow cell. Library preparation followed the “PCR tiling of SARS-CoV-2 virus with rapid barcoding and Midnight RT PCR Expansion” protocol (SQK-RBK110.96 and EXP-MRT001), which generates 1,200 bp amplicons [

24].

2.3. Illumina sequencing data processing workflow

Illumina sequencing data were analyzed using in-house scripts and the nf-core/viralrecon pipeline software (v.2.6.0) [

25]. Briefly, after read quality filtering, sequences for each sample are aligned to the SARS-CoV-2 isolate Wuhan-Hu-1 (GenBank accession: MN908947.3) [

26] using bowtie2 (v.2.4.4) algorithm [

27], followed by primer sequence removal and duplicate read marking using iVar (v.1.4) [

28] and Picard tools (v3.0.0) [

29], respectively. Genomic variants were identified through iVar software using a minimum allele frequency threshold of 0.25 for calling variants and a filtering step to keep variants with a minimum allele frequency threshold of 0.75. Using the set of high confidence variants and the MN908947.3 genome, a consensus genome per sample was finally built using bcftools (v.1.16) [

30].

Lineage and clade assignment to each consensus genome was generated by the Pangolin (v.4.3.1, pangolin-data v.1.32) [

31] and Nextclade (v.3.9.1) [

32] tools, respectively.

2.4. Nanopore sequencing data processing workflow

For Nanopore data, base calling was performed on a Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) cluster with four Tesla v100 GPUs using the app Guppy (v.5.0.16) [

33] and the model dna_r9.4.1_450bps_hac. High-accuracy FASTQ files produced by Guppy were then processed with the nf-core/viralrecon pipeline (version 2.6.0), which employs the ARTIC Network pipeline [

34] for read alignment to the SARS-CoV-2 isolate (MN908947.3), variant calling and consensus sequence generation. Lineage and clade assignment were performed in the same manner as in the Illumina workflow.

2.5. Phylogenetic analysis

A phylogenetic analysis was performed using the Augur toolkit (v.28.0.1) [

35] on a representative set of consensus genomes obtained from the Andalusian surveillance circuit. From the entire dataset spanning January 2021 to January 2025, a representative selection of 50 genomes per lineage was applied. Augur functionality relies on the IQ-Tree (v.2.2.0.3) software [

36]. The MAFFT program (v.7.515) [

37,

38] was utilized for the multiple alignment, using the strain MN908947.3 as reference. The phylogenetic tree is recovered by maximum likelihood, using a general time reversible model with unequal rates and unequal base frequencies [

39]. Branching date estimation was carried out with the least square dating (LSD2) method [

40] using TreeTime (v.0.9.4) [

41]. Branching point reliabilities were estimated by UFBoot, an ultrafast bootstrap approximation to assess branch support [

42].

The results can be viewed on the Nextstrain [

43] local server with detailed sampling information, including the collection date, host’s primary care center and its location (town and province), the hospital that recruited the sample, sequencing technology (Illumina or Nanopore) and the sequencing laboratory facility.

3. Results

3.1. Sequencing effort over the 2021-2025 period

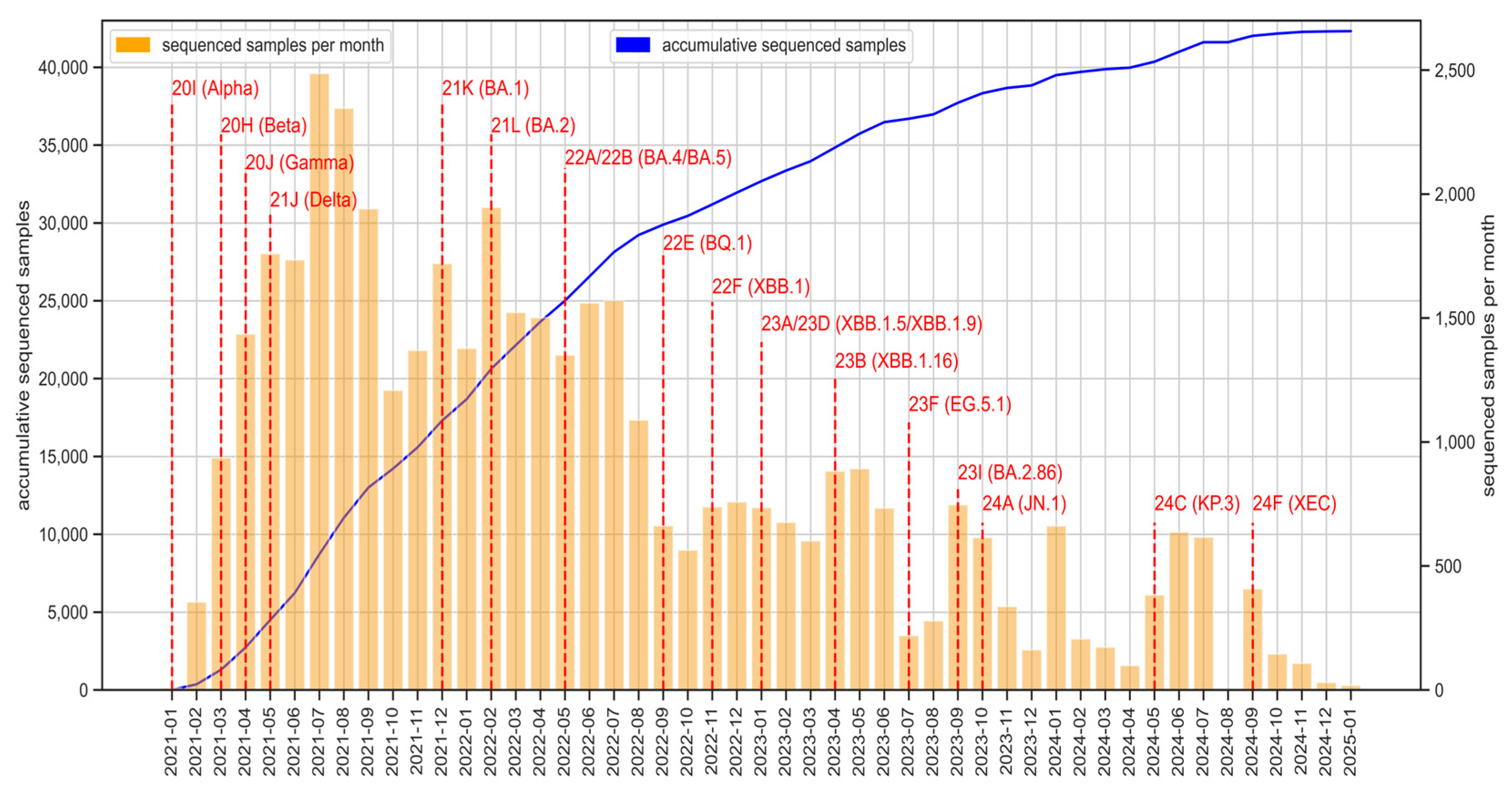

Since the beginning of the circuit, more than 42,500 SARS-CoV-2 genomes have been obtained (

Figure 2), with variability in sequencing volume across the monitored period, reflecting fluctuating epidemic waves. The main SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Interest (VOI), Variants of Concern (VOC) and Variants under Monitoring (VUM) were detected in Andalusia. Notable VOCs such as Alpha (20I/B.1.1.7), Beta (20H/B.1.351), Gamma (20J/P.1) and Delta (21A/B.1.617.2, 21I, 21J) were identified in early 2021, followed by the emergence of multiple Omicron subvariants (21K/BA.1, 21L/BA.2, 22A/BA.4 or 22B/BA.5) as well as recombinant forms like 23A/XBB.1.5, 23D/XBB.1.9 or 23B/XBB.1.16 throughout 2022 and 2023. The detection of recent variants, including 23I/BA.2.86, 24A/JN.1, 24C/KP.3 and 24F/XEC recombinant during 2023 and 2024 underscores the continued evolution of SARS-CoV-2 and the necessity of sustained genomic monitoring.

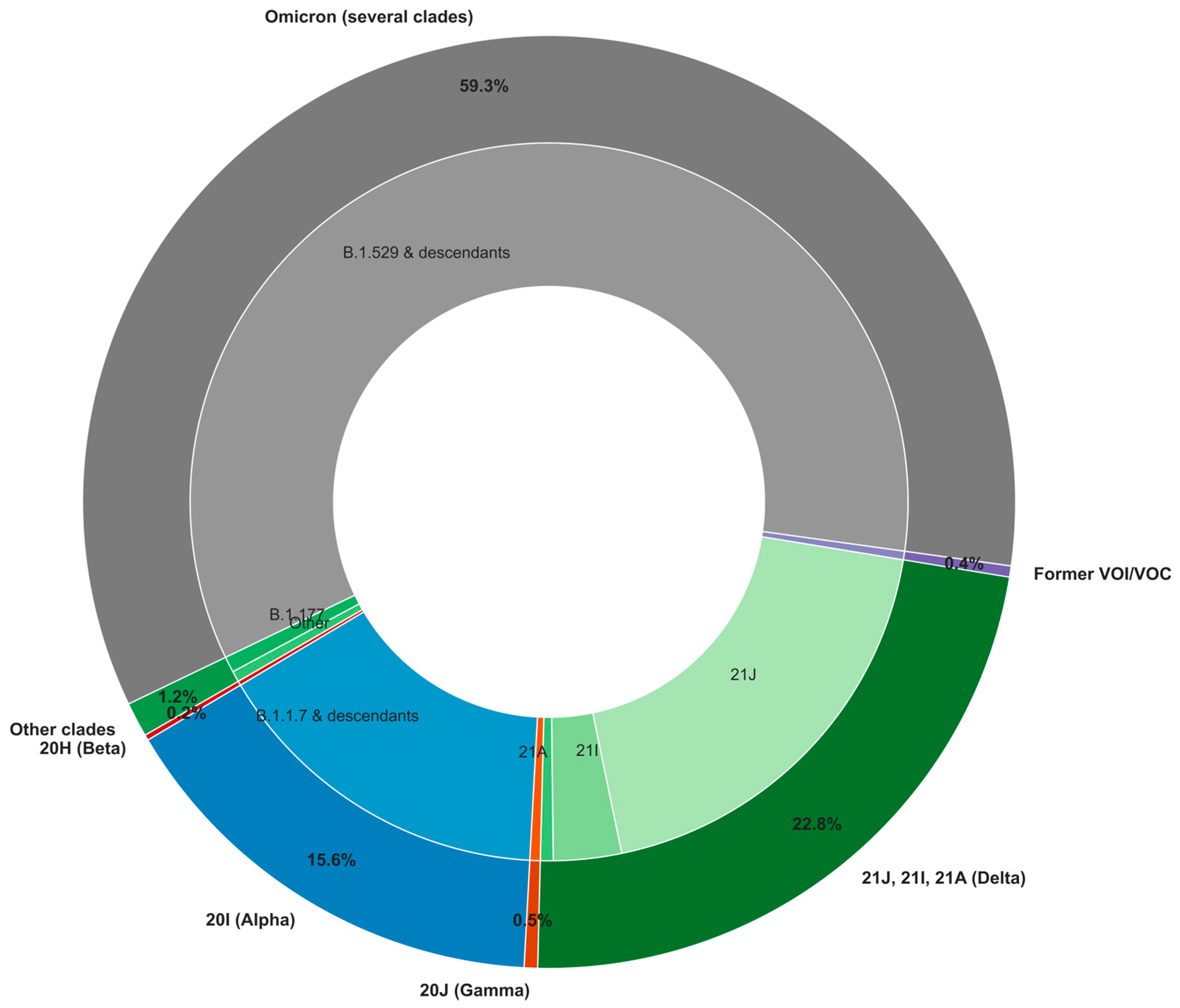

Over the study period and focusing on high-quality SARS-CoV-2 genomes with at least 95% genome coverage, the Omicron variant and its descendants accounted for the largest proportion of detected cases (59.3%,

Figure 3). Delta variants formed the second-largest group (22.8%), represented by three primary clades (21A, 21I, and 21J) with distinct distributions. The Alpha/20I variant followed, making up 15.6% of cases. Other variants circulated at lower frequencies, including Beta/20H (0.2%), Gamma/20J (0.5%), and previously classified VOI and VOC (0.4%), which include Eta/21D, Iota/21F, Lambda/21G, and Mu/21H. Finally, 1.2% of cases were grouped into "other clades," encompassing 20E/B.1.177, an early prevalent lineage in Spain that later spread across Europe [

6], as well as other early SARS-CoV-2 lineages (20A/B.1, 20C/B.1.575, among others). This distribution reflects the shifting dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 variants, with Omicron emerging as the dominant variant, likely due to its enhanced transmissibility and immune escape capabilities [

44].

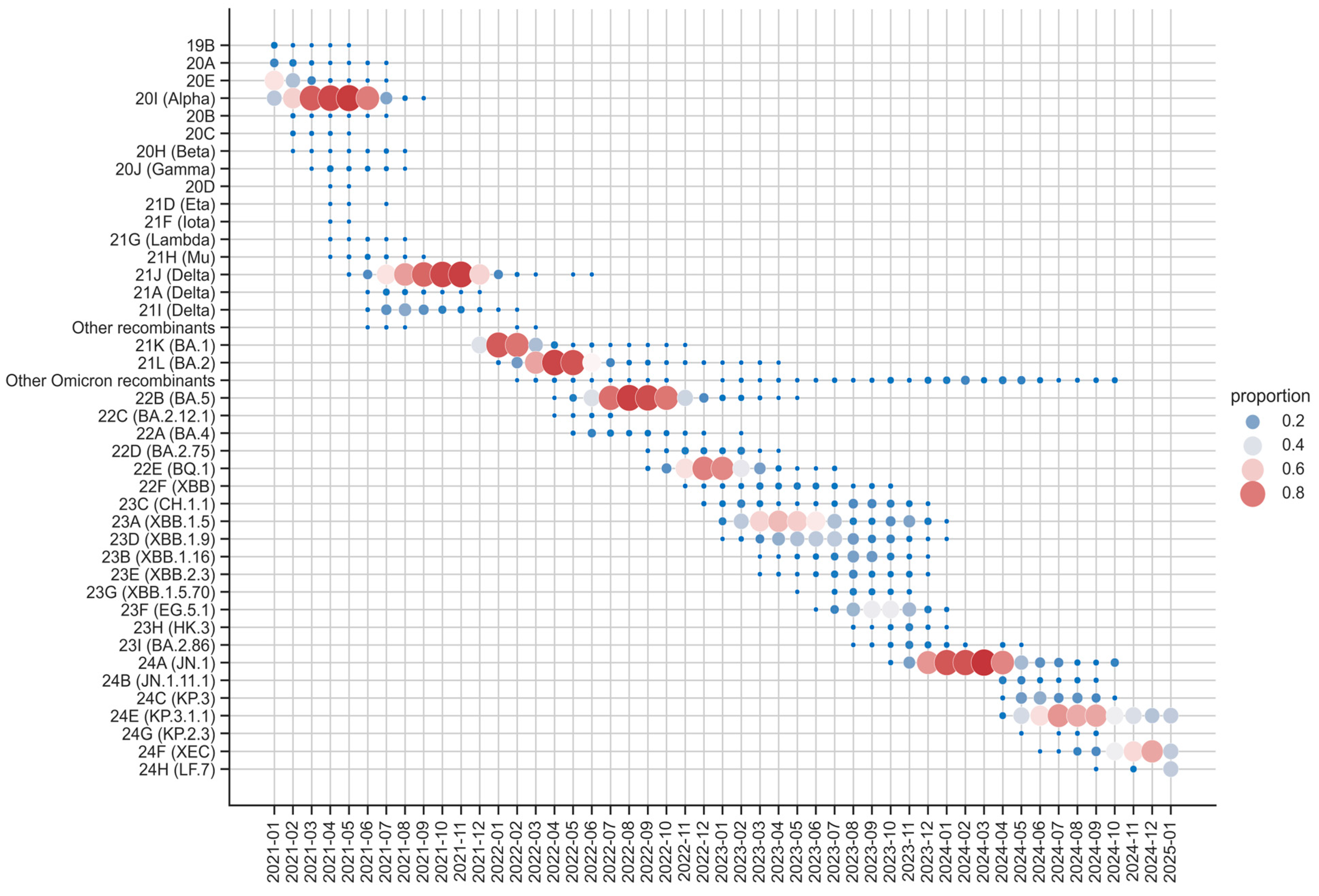

Figure 4 illustrates the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 variants in Andalusia from 2021 to 2025, showing distinct patterns of clade dominance and coexistence. Early in the timeline, 2021 was characterized by the coexistence of several clades, including 19B, 20A, 20E, 20I (Alpha) and Delta (21J, 21A and 21I) among others less relevant. By mid-2021, Delta (21J) became the dominant clade, maintaining its prevalence into late 2021. This prolonged dominance underscored its high transmissibility and global impact during that phase of the pandemic.

The transition from Delta to Omicron began in late 2021, with Omicron rapidly replacing Delta by early 2022. Among Omicron sublineages, 21K (BA.1), 21L (BA.2) and 22B (BA.5) emerged as the most prevalent, driven by key mutations that enhanced immune evasion. For instance, BA.1 contained key mutations such as S371L, S373P, and S375F, which reduced antibody neutralization, affecting the efficacy of monoclonal antibodies and immune responses from prior infections or vaccinations [

44]. BA.2, while sharing many mutations with BA.1, contained the unique S371F substitution, further improving immune escape [

44]. Meanwhile, BA.5's (22B) dominance was primarily attributed to mutations such as L452R and F486V, which significantly improved immune evasion [

45]. BA.5 remained dominant until November 2022, after which its descendant BQ.1 (22E) emerged as the dominant variant, maintaining dominance until March 2023.

In 2023, the evolutionary landscape of SARS-CoV-2 shifted with the emergence and dominance of Omicron recombinant clades. By late 2023, the landscape exhibited the highest clade diversity, characterized by the coexistence of recombinant clades such as 23A (XBB.1.5), 23D (XBB.1.9), and 23F (EG.5.1), among others, reflecting a complex viral ecosystem. These recombinant clades, arising from BA.2-derived variants, represented a significant proportion of the Omicron landscape. Notably, 23A (XBB.1.5), also known as “Kraken,” became the most prevalent recombinant clade due to its superior immune evasion, largely due to mutations like S486P [

46]. Other recombinant clades, including 23D (XBB.1.9) and 23F (EG.5.1), further highlighted the diversity and adaptive capacity of the virus. During this period, no single clade maintained clear dominance, indicating a transitional phase driven by the emergence and competition of multiple variants.

By early 2024, the non-recombinant clade 24A (JN.1) emerged as the dominant clade, reaching high prevalence. However, as the year progressed, 24E (KP.3.1.1) gained dominance, demonstrating increased transmissibility and immune escape potential. Along with 24F (XEC), it carries spike protein mutations such as S:F456L, which enhance transmissibility, receptor binding affinity, and immune evasion, highlighting its potential to influence future transmission dynamics [

47].

The overall trends reveal alternating periods of clade dominance and high diversity. From 2021 to late 2022 and again from late 2023 to late 2024, specific clades predominated. Conversely, 2023 stood out for the coexistence of recombinant clades. These patterns reflect the ongoing interplay between transmissibility, immune evasion, and recombination, reinforcing the need for continuous genomic surveillance.

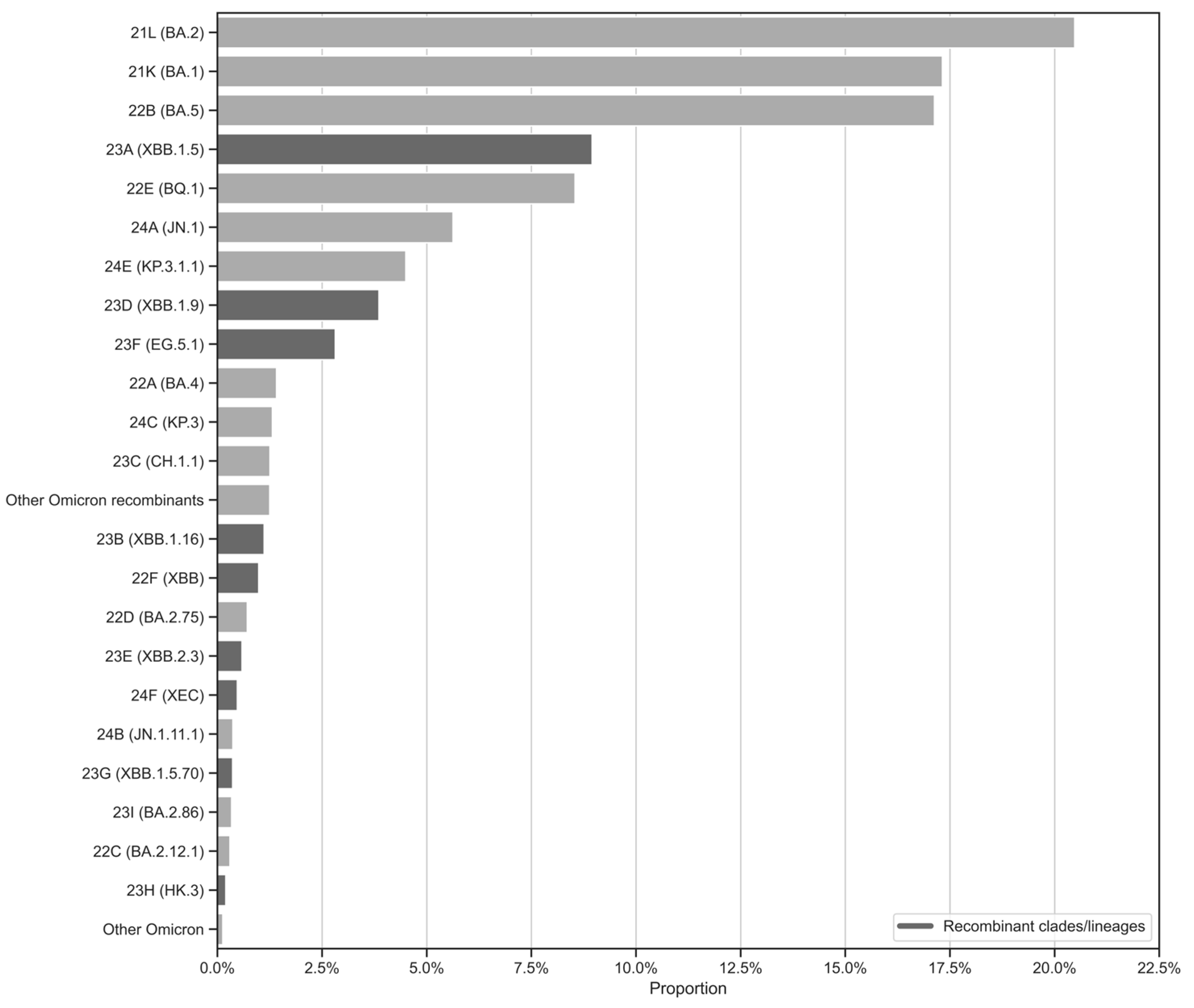

While

Figure 4 provides insights into the temporal evolution and dominance of SARS-CoV-2 clades in Andalusia,

Figure 5 complements this by presenting a proportional overview of Omicron clades based on sample representation in the surveillance circuit, rather than temporal trends. Additionally, it distinguishes between recombinant and non-recombinant clades. As a result, the most abundant clades, 21L/BA.2, 21K/BA.1 and 22B/BA.5, together account for a significant portion of the dataset. This high representation likely reflects their widespread circulation and epidemiological dominance during the early phases of the Omicron wave, coinciding with intensified sequencing efforts during their emergence (

Figure 2). Recombinant clades such as 23A/XBB.1.5, 23D/XBB.1.9, and 23F/EG.5.1 are also well-represented, highlighting their growing significance in the later stages of the pandemic. Meanwhile, clades like 24E/KP.3.1.1 and 24F/XEC, though less prominent, reflect the ongoing diversification of the virus and its ability to adapt to selective pressures.

3.2. Nextstrain local server

The Nextstrain local server for the circuit, available at [

48], allows epidemiologists and regional public health institutions to conduct near real-time genomic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 evolution.

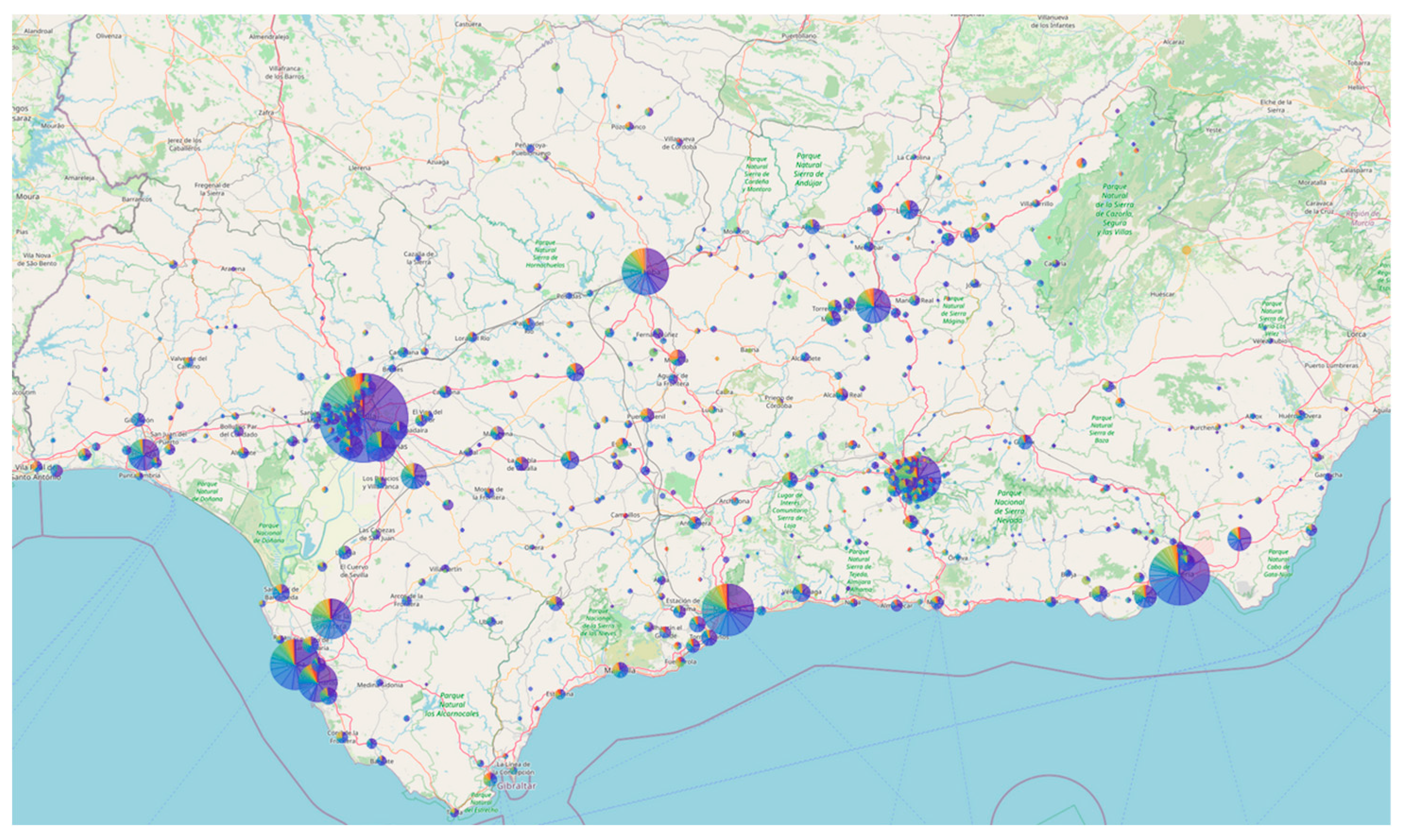

Figure 6 shows the map of Andalusia generated by the Auspice software for the Nextstrain local server of the circuit, using a representative set of approximately 9,000 genomes (see materials and methods). As can be observed, the entire region is well represented, with a higher concentration of samples in more densely populated areas.

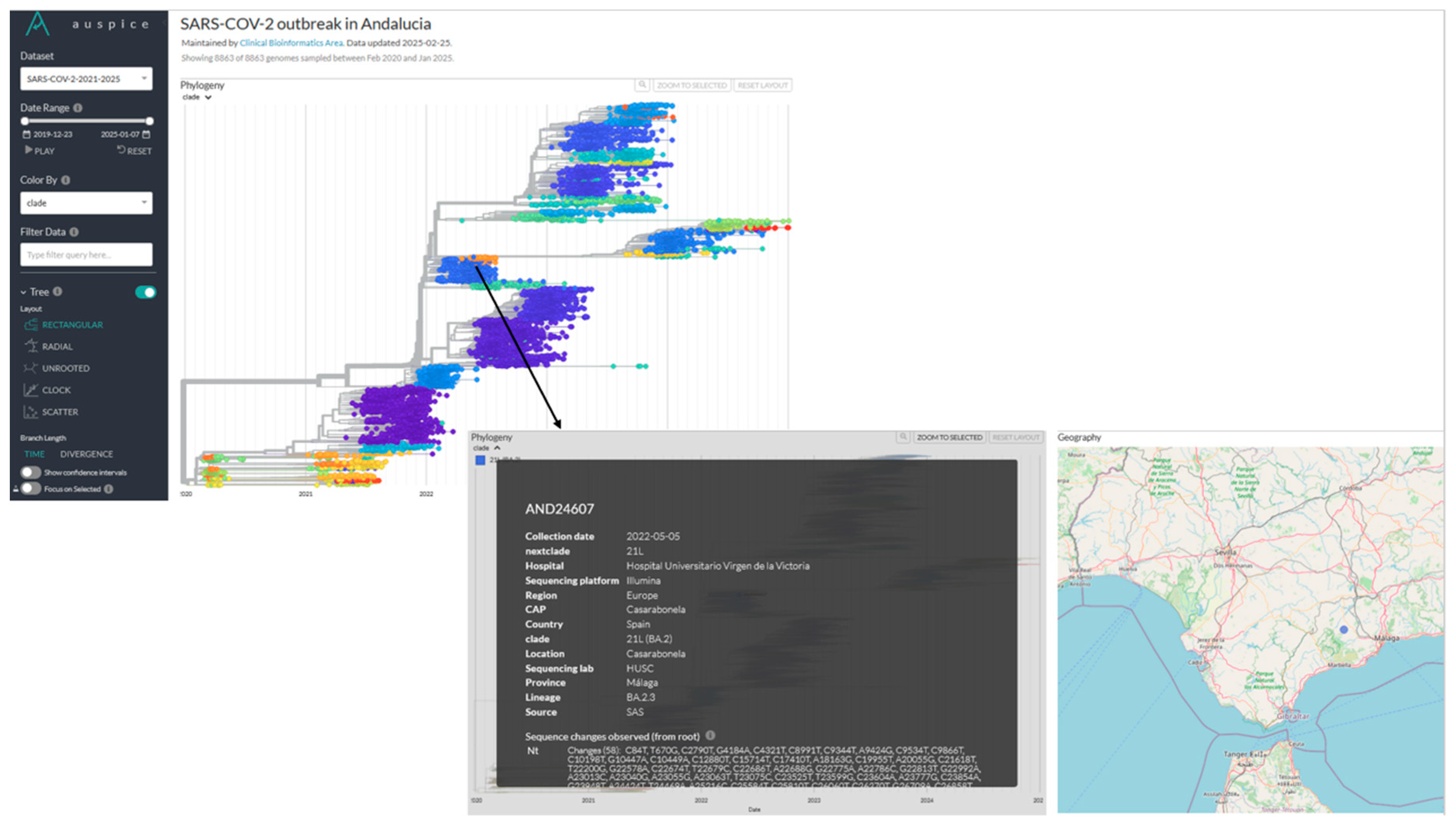

The corresponding phylogeny is also available (

Figure 7), providing information on individual samples, including details such as the primary care center. This data supports epidemiologists in enhancing outbreak response, strengthening surveillance and improving public health decision-making.

3.3. Use cases

During the 2021-2025 period the Andalusian Surveillance circuit has been used for several retrospective studies by facilitating the systematic storage of SARS-CoV-2 genomes within the BPS database [

17]. This integration enables the direct linkage of viral genomic data with the clinical record of infected patients, providing an unprecedented environment for large-scale Real-World Evidence (RWE) studies. Through this unique data ecosystem, researchers can explore the interplay between viral evolution, patient characteristics, disease progression, treatment responses, and long-term health outcomes. Such a robust framework fosters novel epidemiological insights and supports precision medicine approaches, strengthening public health decision-making in the face of emerging infectious threats. Actually, the availability of SARS-CoV-2 genomes in the context of the clinical data of the infected patients allowed to carry out a study demonstrating that variants can have different mortality (regardless of the patient status, age, sex, comorbidities, and any other characteristic), in particular, that the alpha variant was deadlier that the previous Wuhan variant [

49].

Additionally, a series of studies allowed the evaluation of the protective effect of some drugs on COVID-19 prognostic and patient mortality. Notably, vitamin-D [

50] or the antipsychotic aripiprazole [

51] have shown significant protective effects. Furthermore, a broader study identified 21 drugs that were associated with reduced COVID-19 mortality [

52].

The evolution of the virus and the constant replacement of variants has also been studied, with a particular focus on the role of recombination in viral adaptation. Studies have documented the occurrence of viral co-infections, which provided the conditions for the emergence of novel recombinant variants. These findings underscore the importance of recombination as a key mechanism driving SARS-CoV-2 diversity and evolution [

53].

Moreover, the circuit has actively contributed to technical advancements in genomic surveillance. Efforts have been directed toward improving experimental procedures for virus detection, enhancing the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic testing [

54]. In addition, significant progress has been made in genomic data management, including the development of methodologies for reconstructing complete viral genomes from partial or low-quality sequencing data [

55]. These innovations have improved the accuracy and reliability of genomic analyses, ensuring high-quality data for epidemiological and public health decision-making.

4. Discussion

The implementation of a standardized genomic surveillance circuit for SARS-CoV-2 in Andalusia has provided an unprecedented opportunity to monitor the evolution of the virus and inform public health decisions in near real time. The integration of a common protocol for sequencing and bioinformatics analysis across the whole region has ensured consistency in data quality and interpretation. This coordinated approach, covering a population of 8.5 million people, represents one of the largest regional efforts in genomic surveillance within a decentralized healthcare system. By unifying sequencing workflows across hospitals and integrating genomic data into a centralized platform, the circuit has facilitated rapid variant detection, epidemiological tracking and clinical outcome assessment.

One of the major strengths of this surveillance initiative has been its ability to provide near real-time genomic monitoring, enabling health authorities to quickly adapt containment measures in response to emerging variants. The circuit has identified and tracked the introduction and expansion of major SARS-CoV-2 variants in Andalusia, reflecting both global and region-specific transmission dynamics. The transition from early variants like Alpha and Delta to the successive waves of Omicron subvariants (21K/BA.1, 21L/BA.2, 22B/BA.5) and recombinant forms (23A/XBB.1.5, 23B/XBB.1.16, 23D/XBB.1.9), including novel recombinants [

53], demonstrates the rapid adaptability of SARS-CoV-2 to immune pressure and transmissibility advantages. This underscores the importance of sustained genomic surveillance in identifying new evolutionary pathways and reinforces the need for continuous monitoring.

Beyond variant identification, the genomic surveillance circuit has provided crucial insights into epidemiological trends. By linking genomic data with clinical records from the BPS, the circuit has enabled studies assessing the impact of specific mutations on disease severity, patient outcomes, and treatment effectiveness.

The success of the SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance circuit in Andalusia has also set the stage for a broader whole-genome sequencing surveillance initiative [

56]. Building upon the infrastructure and expertise developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, this circuit has expanded its scope to other emerging and endemic viral threats, including West Nile virus [

57], monkeypox virus [

58], influenza virus and respiratory syncytial virus. This expansion reinforces the long-term value of investing in genomic surveillance as a fundamental tool for epidemic preparedness and response. The ability to quickly adapt sequencing pipelines to new pathogens ensures that Andalusia remains at the forefront of public health genomics, providing a model that can be replicated in other regions.

Despite its achievements, the genomic surveillance circuit also presents challenges and areas for improvement. One limitation is the logistical complexity of maintaining a high-throughput sequencing infrastructure at regional level. Coordinating sample collection, sequencing workflows, and data integration in a decentralized healthcare system requires continuous optimization of resources and standardization efforts. Additionally, while the reliance on centralized sequencing hubs has facilitated high-quality data generation, it may also introduce delays during periods of very high demand.

Ensuring the sustainability of genomic surveillance beyond pandemic crises will require long-term investment, interdisciplinary collaboration, and integration with other epidemiological monitoring systems to maintain a robust and adaptable genomic surveillance network [

59].

5. Conclusions

The establishment of a regional genomic surveillance network for SARS-CoV-2 in Andalusia has demonstrated the power of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) in tracking viral evolution, guiding public health interventions, and integrating clinical and epidemiological data. Expanding this initiative to other pathogens strengthens infectious disease monitoring and pandemic preparedness.

Centralized WGS-based surveillance circuits, such as this one, provide an efficient approach for real-time outbreak detection, transmission tracking, and infection control. Their integration into public health systems enhances epidemiological investigations and response strategies.

Moving forward, maintaining a continuous genomic monitoring infrastructure will be critical for early threat detection and effective outbreak response. By leveraging centralized WGS surveillance, Andalusia contributes to global infectious disease monitoring within the One Health framework.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: List of hospitals that participate in the SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance circuit of Andalusia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JD, JAL, FG; methodology, JPF, CSCS, ML, AA, CL, FMO, PCM, LMD, AdS, AF, SSG; software, JPF, CSCS, FMO, ML; formal analysis, JPF, CSCS, CL, FMO; resources, JD, JAL, FG, JMNM, NL, The Andalusian COVID-19 sequencing initiative; data curation, JPF.; writing—original draft preparation, JPF, JD.; writing—review and editing, JPF, JD, JAL, FG, CL, SSG, CSCS, JMNM.; supervision, JD.; funding acquisition, JD, JAL, FG, JMNM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has been funded by the European Union’s EU4Health programme (EU4HEALTH - 101113109), and the HERA incubator plan (ECDC/HERA/2021/024 ECD.12241). JD has been supported by grant PT17/0009/0006 from the ISCIII, co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), as well as the European Commision’s H2020 ELIXIR-EXCELERATE (Grant Agreeement No. 676559) and by the Consejería de Salud y Familias-Junta de Andalucía (COVID-0012-2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the data were obtained in routine surveillance

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The SARS-CoV-2 whole-genome sequences described in this study are available in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under the identifier PRJEB44396 and in GISAID.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VOI |

Variants of Interest |

| VOC |

Variants of Concern |

| VUM |

Variants Under Monitoring |

| EHR |

Electronic Health Record |

| BPS |

Base Poblacional de Salud |

| GPU |

Graphics Processing Unit |

| RWE |

Real-Word Evidence |

| WGS |

Whole-genome sequencing |

References

- Shu, Y.; McCauley, J. GISAID: Global initiative on sharing all influenza data–from vision to reality. Eurosurveillance 2017, 22, 30494.

- Faria, N.R.; Mellan, T.A.; Whittaker, C.; Claro, I.M.; Candido, D.d.S.; Mishra, S.; Crispim, M.A.; Sales, F.C.; Hawryluk, I.; McCrone, J.T. Genomics and epidemiology of the P. 1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science 2021, 372, 815-821.

- Tang, J.W.; Tambyah, P.A.; Hui, D.S. Emergence of a new SARS-CoV-2 variant in the UK. Journal of Infection 2021, 82, e27-e28.

- Tegally, H.; Wilkinson, E.; Giovanetti, M.; Iranzadeh, A.; Fonseca, V.; Giandhari, J.; Doolabh, D.; Pillay, S.; San, E.J.; Msomi, N. Detection of a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern in South Africa. Nature 2021, 592, 438-443.

- Volz, E.; Mishra, S.; Chand, M.; Barrett, J.C.; Johnson, R.; Geidelberg, L.; Hinsley, W.R.; Laydon, D.J.; Dabrera, G.; O’Toole, Á. Assessing transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B. 1.1. 7 in England. Nature 2021, 593, 266-269.

- Hodcroft EB, Zuber M, Nadeau S, Vaughan TG, Crawford KHD, Althaus CL, Reichmuth ML, Bowen JE, Walls AC, Corti D, Bloom JD, Veesler D, Mateo D, Hernando A, Comas I, González-Candelas F, Stadler T, Neher RA. Spread of a SARS-CoV-2 variant through Europe in the summer of 2020. Nature. 2021;595(7869):707–712.

- Araf, Y.; Akter, F.; Tang, Y.d.; Fatemi, R.; Parvez, M.S.A.; Zheng, C.; Hossain, M.G. Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2: genomics, transmissibility, and responses to current COVID-19 vaccines. Journal of medical virology 2022, 94, 1825-1832.

- Chen, R.E.; Zhang, X.; Case, J.B.; Winkler, E.S.; Liu, Y.; VanBlargan, L.A.; Liu, J.; Errico, J.M.; Xie, X.; Suryadevara, N. Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants to neutralization by monoclonal and serum-derived polyclonal antibodies. Nature medicine 2021, 27, 717-726.

- Beyer, D.K.; Forero, A. Mechanisms of Antiviral Immune Evasion of SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Molecular Biology 2022, 434, 167265.

- Cyranoski, D. Alarming COVID variants show vital role of genomic surveillance. Nature 2021, 589.

- WHO. SARS- CoV-2 variants of concern and variants of interest. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Porter, AF.; Sherry, N.; Andersson, P.; Johnson, SA.; Duchene, S.; Howden, BP. New rules for genomics-informed COVID-19 responses-Lessons learned from the first waves of the Omicron variant in Australia. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18(10):e1010415.

- Sequencing of the SARS-CoV-2 virus genome for the monitoring and management of the Covid-19 epidemic in Andalusia and the rapid generation of prognostic and response to treatment biomarkers. Available online: https://www.clinbioinfosspa.es/projects/covseq/indexEng.html (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- SARS-CoV-2 whole genome sequencing circuit in Andalusia. Available online: https://www.clinbioinfosspa.es/COVID_circuit/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Vázquez-Morón S, Iglesias-Caballero M, Lepe JA, Garcia F, Melón S, Marimon JM, de Viedma DG, Folgueira MD, Galán JC, López-Causapé C, Benito-Ruesca R, Alcoba-Florez J, González-Candelas F, de Toro M, Fajardo M, Ezpeleta C, Pérez-González C, Martínez-González B, Navarro D, González-Rodríguez LJ, Pérez-Ruiz M, Cilla G, Palacios-García E, Pérez-Lago L, Rodríguez-Iglesias M, Cantón R, Delgado-Iribarren A, Oteo-Iglesias J. Enhancing SARS-CoV-2 Surveillance through Regular Genomic Sequencing in Spain: The RELECOV Network. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(10):8573.

- Dopazo, J.; Maya-Miles, D.; García, F.; Lorusso, N.; Calleja, M.Á.; Pareja, M.J.; López-Miranda, J.; Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Padillo, J.; Túnez, I. Implementing Personalized Medicine in COVID-19 in Andalusia: An Opportunity to Transform the Healthcare System. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2021, 11, 475.

- Muñoyerro-Muñiz, D.; Goicoechea-Salazar, J.; García-León, F.; Laguna-Tellez, A.; Larrocha-Mata, D.; Cardero-Rivas, M. Health record linkage: Andalusian health population database. Gaceta Sanitaria 2019, 34, 105-113.

- ISCIII. Integration of Genome Sequencing in the SARS-CoV-2 Surveillance (in Spanish). Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/Integracion_de_la_secuenciacion_genomica-en_la_vigilancia_del_SARS-CoV-2.pdf . (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- ARTIC Network. Available online: https://community.artic.network/ (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- ARTIC Network, V3 Primer Availability. Available online: https://community.artic.network/t/v3-primer-availability/123 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- ARTIC Network, SARS-CoV-2 Version 4 Scheme Release. Available online: https://community.artic.network/t/sars-cov-2-version-4-scheme-release/312 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- ARTIC Network, SARS-CoV-2 V4.1 Update for Omicron Variant. Available online: https://community.artic.network/t/sars-cov-2-v4-1-update-for-omicron-variant/342 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- ARTIC Network, SARS-CoV-2 Version 5.3.2 Scheme Release. Available online: https://community.artic.network/t/sars-cov-2-version-5-3-2-scheme-release/462 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Freed, N.E.; Vlková, M.; Faisal, M.B.; Silander, O.K. Rapid and inexpensive whole-genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 using 1200 bp tiled amplicons and Oxford Nanopore Rapid Barcoding. Biol. Methods Protoc. 2020, 5, bpaa014.

- Patel, H.; Monzón, S.; Varona, S.; Espinosa-Carrasco, J.; Garcia, M.U.; Nf-Core Bot; Ewels, P. nf-core/viralrecon: nf-core/viralrecon v2.6.0 - Rhodium Raccoon. Zenodo 2023.

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273.

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359.

- Grubaugh, N.D.; Gangavarapu, K.; Quick, J.; Matteson, N.L.; Goes De Jesus, J.; Main, B.J.; Tan, A.L.; Paul, L.M.; Brackney, D.E.; Grewal, S.; Gurfield, N.; Van Rompay, K.K.A.; Isern, S.; Michael, S.F.; Coffey, L.L.; Loman, N.J.; Andersen, K.G. An amplicon-based sequencing framework for accurately measuring intrahost virus diversity using PrimalSeq and iVar. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 8.

- Broad Institute. Picard Toolkit; Broad Institute, GitHub Repository, 2018. Available online: http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/ (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; Li, H. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab008.

- O'Toole, Á.; Scher, E.; Underwood, A.; Jackson, B.; Hill, V.; McCrone, J.T.; Colquhoun, R.; Ruis, C.; Abu-Dahab, K.; Taylor, B.; Yeats, C.; du Plessis, L.; Maloney, D.; Medd, N.; Attwood, S.W.; Aanensen, D.M.; Holmes, E.C.; Pybus, O.G.; Rambaut, A. Assignment of epidemiological lineages in an emerging pandemic using the pangolin tool. Virus Evol. 2021, 7, veab064.

- Aksamentov, I.; Roemer, C.; Hodcroft, E.B.; Neher, R.A. Nextclade: Clade assignment, mutation calling and quality control for viral genomes. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3773.

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Holt, K.E. Performance of Neural Network Basecalling Tools for Oxford Nanopore Sequencing. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 129.

- ARTIC Network. The ARTIC Field Bioinformatics Pipeline. Available online: https://github.com/artic-network/fieldbioinformatics (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Huddleston, J.; Hadfield, J.; Sibley, T.R.; Lee, J.; Fay, K.; Ilcisin, M.; Harkins, E.; Bedford, T.; Neher, R.A.; Hodcroft, E.B. Augur: a bioinformatics toolkit for phylogenetic analyses of human pathogens. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 2906.

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; Von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534.

- Katoh, K.; Misawa, K.; Kuma, K.; Miyata, T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 3059–3066.

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. A simple method to control over-alignment in the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 1933–1942.

- Tavaré, S. Some Probabilistic and Statistical Problems in the Analysis of DNA Sequences; University of Utah: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 1986.

- To, T.-H.; Jung, M.; Lycett, S.; Gascuel, O. Fast Dating Using Least-Squares Criteria and Algorithms. Syst. Biol. 2016, 65, 82–97.

- Sagulenko, P.; Puller, V.; Neher, R.A. TreeTime: Maximum-likelihood phylodynamic analysis. Virus Evol. 2018, 4, vex042.

- Hoang, D.T.; Chernomor, O.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q.; Vinh, L.S. UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 518–522.

- Hadfield, J.; Megill, C.; Bell, S.M.; Huddleston, J.; Potter, B.; Callender, C.; Sagulenko, P.; Bedford, T.; Neher, R.A. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 4121–4123.

- Willett, B.J.; Grove, J.; MacLean, O.A.; Wilkie, C.; De Lorenzo, G.; Furnon, W.; Cantoni, D.; Scott, S.; Logan, N.; Ashraf, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron is an immune escape variant with an altered cell entry pathway. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1161–1179.

- Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Iketani, S.; Nair, M.S.; Li, Z.; Mohri, H.; Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Bowen, A.D.; Chang, J.Y.; et al. Antibody evasion by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5. Nature 2022, 608, 603–608.

- Tamura, T.; Irie, T.; Deguchi, S.; Yajima, H.; Tsuda, M.; Nasser, H.; Mizuma, K.; Plianchaisuk, A.; Suzuki, S.; Uriu, K.; et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron XBB.1.5 variant. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1176.

- Wang, Q.; Mellis, I.A.; Ho, J.; Bowen, A.; Kowalski-Dobson, T.; Valdez, R.; Katsamba, P.S.; Wu, M.; Lee, C.; Shapiro, L.; et al. Recurrent SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations confer growth advantages to select JN.1 sublineages. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2402880.

- The SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance circuit of Andalusia, Nextstrain server. Available online: https://nextstrain.clinbioinfosspa.es/SARS-COV-2-2021-2025 (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Loucera, C.; Perez-Florido, J.; Casimiro-Soriguer, C.S.; Ortuño, F.M.; Carmona, R.; Bostelmann, G.; Martínez-González, L.J.; Muñoyerro-Muñiz, D.; Villegas, R.; Rodriguez-Baño, J.; et al. Assessing the impact of SARS-CoV-2 lineages and mutations on patient survival. Viruses 2022, 14, 9.

- Loucera, C.; Peña-Chilet, M.; Esteban-Medina, M.; Muñoyerro-Muñiz, D.; Villegas, R.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; Rodriguez-Baño, J.; Túnez, I.; Bouillon, R.; Dopazo, J. Real world evidence of calcifediol or vitamin D prescription and mortality rate of COVID-19 in a retrospective cohort of hospitalized Andalusian patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23380.

- Loucera-Muñecas, C.; Canal-Rivero, M.; Ruiz-Veguilla, M.; Carmona, R.; Bostelmann, G.; Garrido-Torres, N.; Dopazo, J.; Crespo-Facorro, B. Aripiprazole as protector against COVID-19 mortality. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12362.

- Loucera, C.; Carmona, R.; Esteban-Medina, M.; Bostelmann, G.; Muñoyerro-Muñiz, D.; Villegas, R.; Peña-Chilet, M.; Dopazo, J. Real-world evidence with a retrospective cohort of 15,968 COVID-19 hospitalized patients suggests 21 new effective treatments. Virol. J. 2023, 20, 226.

- Perez-Florido, J.; Casimiro-Soriguer, C.S.; Ortuño, F.; Fernandez-Rueda, J.L.; Aguado, A.; Lara, M.; Riazzo, C.; Rodriguez-Iglesias, M.A.; Camacho-Martinez, P.; Merino-Diaz, L.; et al. Detection of high levels of co-infection and the emergence of novel SARS-CoV-2 Delta-Omicron and Omicron-Omicron recombinants in the epidemiological surveillance of Andalusia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3.

- Chaves-Blanco, L.; de Salazar, A.; Fuentes, A.; Viñuela, L.; Perez-Florido, J.; Dopazo, J.; García, F. Evaluation of a combined detection of SARS-CoV-2 and its variants using real-time allele-specific PCR strategy: an advantage for clinical practice. Epidemiol. Infect. 2023, 151, e201.

- Ortuño, F.M.; Loucera, C.; Casimiro-Soriguer, C.S.; Lepe, J.A.; Camacho-Martinez, P.; Merino-Diaz, L.; de Salazar, A.; Chueca, N.; García, F.; Perez-Florido, J.; et al. Highly accurate whole-genome imputation of SARS-CoV-2 from partial or low-quality sequences. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab078.

- The Whole Genome Sequencing Surveillance Circuit of Andalusia. Available online: https://www.clinbioinfosspa.es/surveillance_circuit/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Casimiro-Soriguer, C.S.; Perez-Florido, J.; Fernandez-Rueda, J.L.; Pedrosa-Corral, I.; Guillot-Sulay, V.; Lorusso, N.; Martinez-Gonzalez, L.J.; Navarro-Marí, J.M.; Dopazo, J.; Sanbonmatsu-Gámez, S. Phylogenetic Analysis of the 2020 West Nile Virus (WNV) Outbreak in Andalusia (Spain). Viruses 2021, 13, 836.

- Casimiro-Soriguer, C.S.; Perez-Florido, J.; Lara, M.; Camacho-Martinez, P.; Merino-Diaz, L.; Pupo-Ledo, I.; de Salazar, A.; Fuentes, A.; Viñuela, L.; Chueca, N.; et al. Molecular and phylogenetic characterization of the monkeypox outbreak in the South of Spain. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e1965.

- Neves, A.; Willassen, N.P.; Hjerde, E.; Cuesta, I.; Martin, C.S.; Inno, H.; Pilvar, D.; Ng, K.; Salgado, D.; van Helden, J.; Gu, W.; Popleteeva, M.; Dopazo, J.; Šuri, T.; Pačes, J.; Mazurek, C.; Kurowski, K.; Koralewska, N.; Maier, G.; ELIXIR CONVERGE WP9 community. A survey into the contribution of regional/national pathogen data platforms and on the resources needed to develop and maintain them. F1000Research 2024, 12, 1590.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).