Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

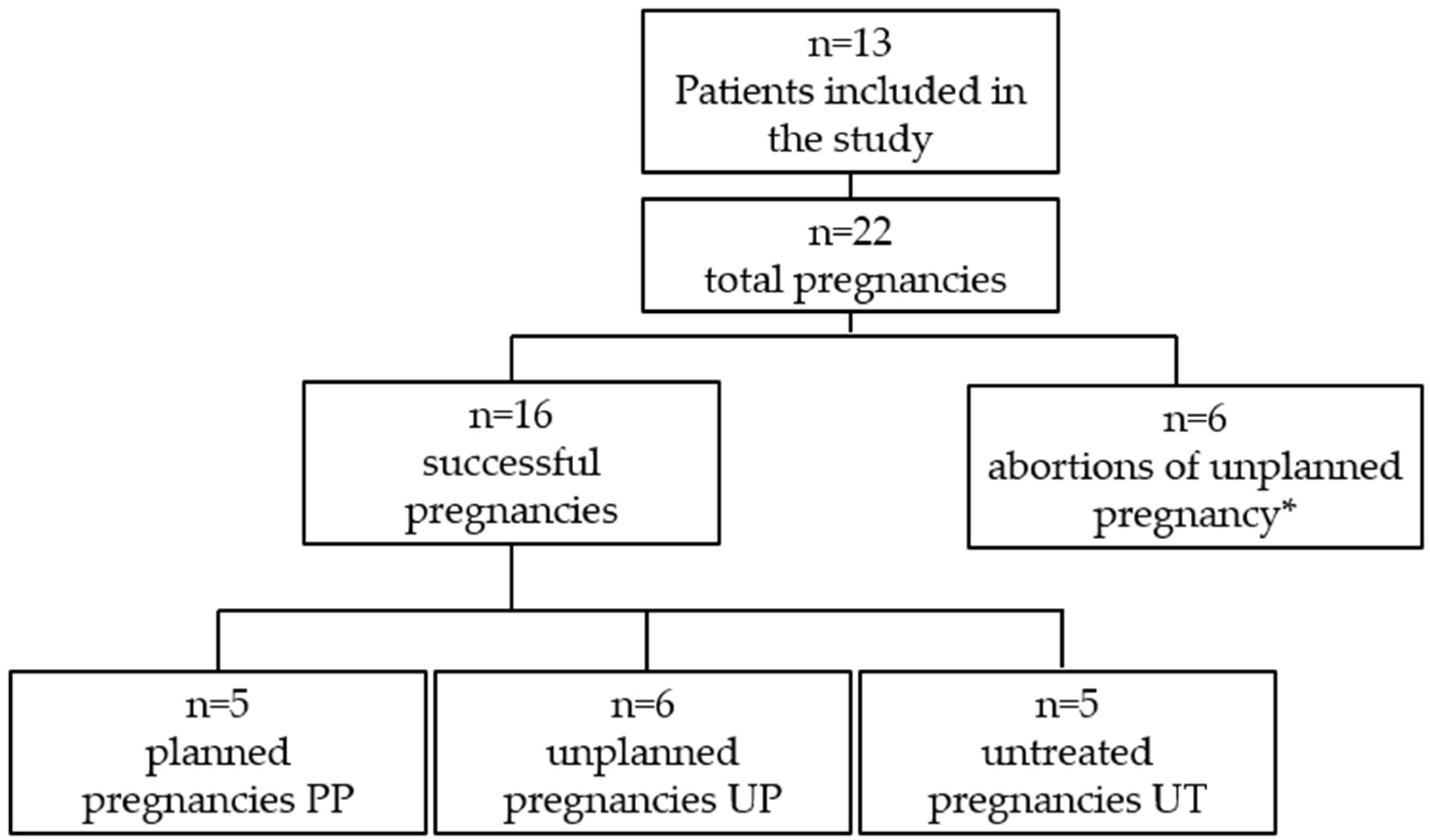

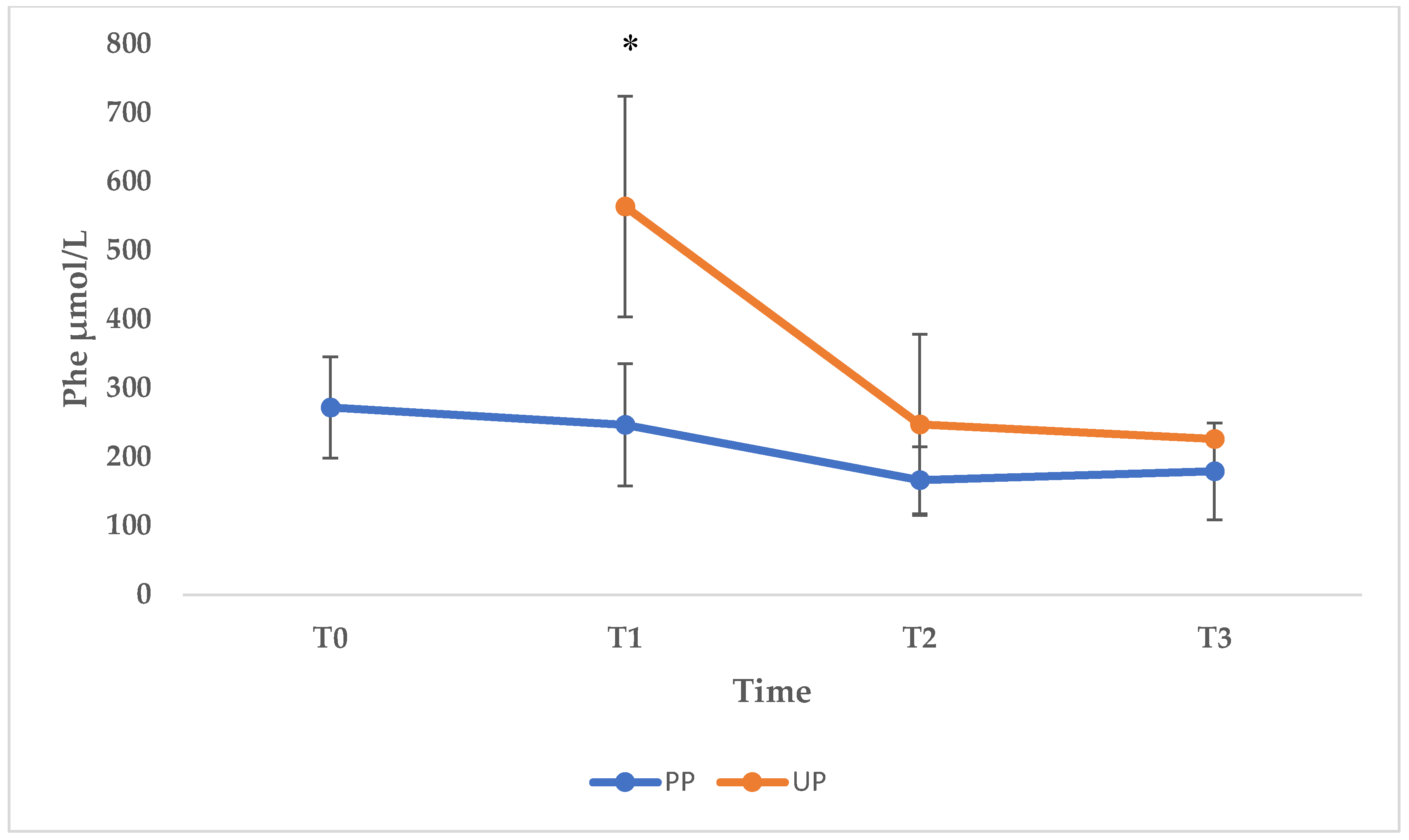

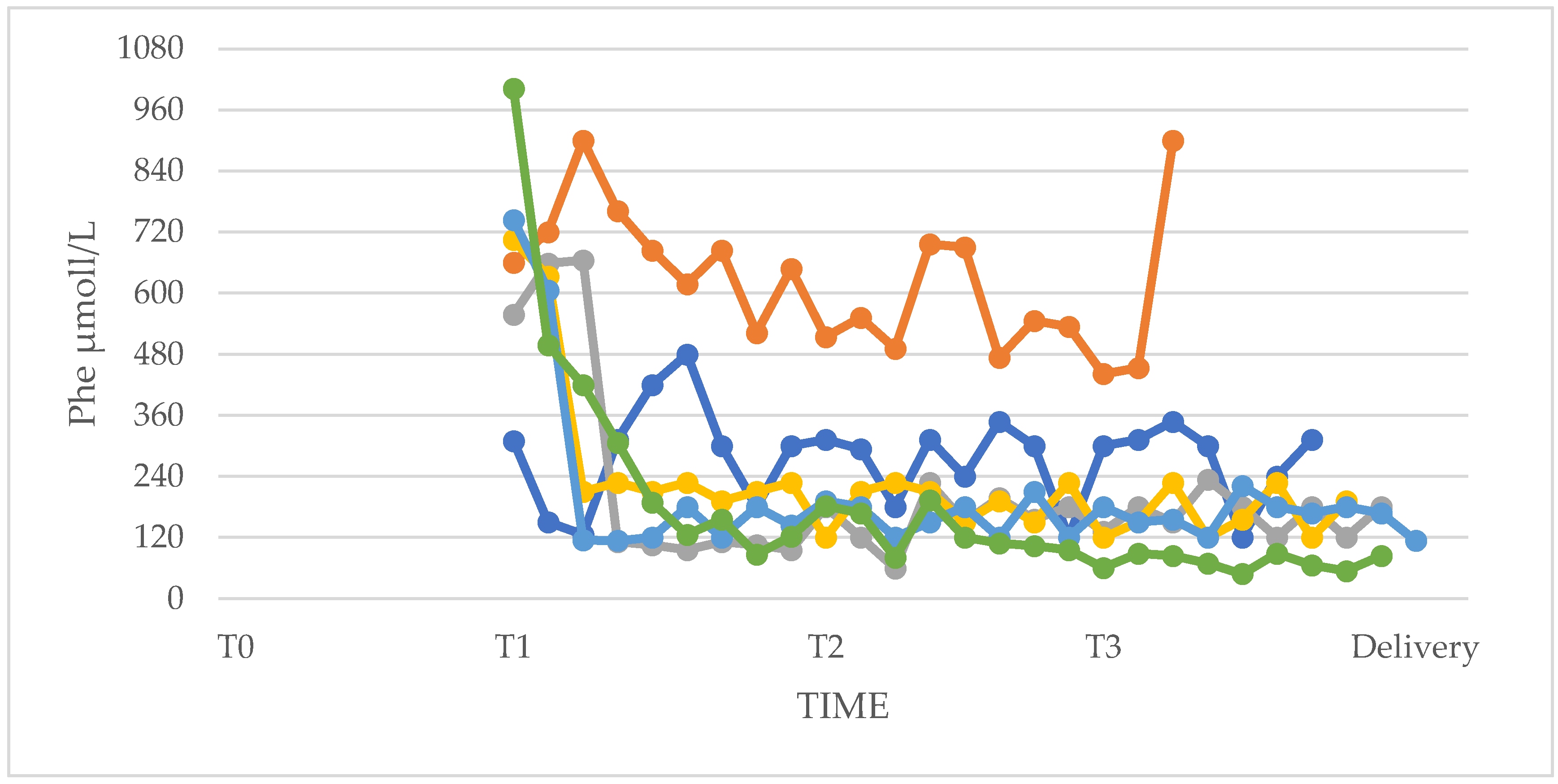

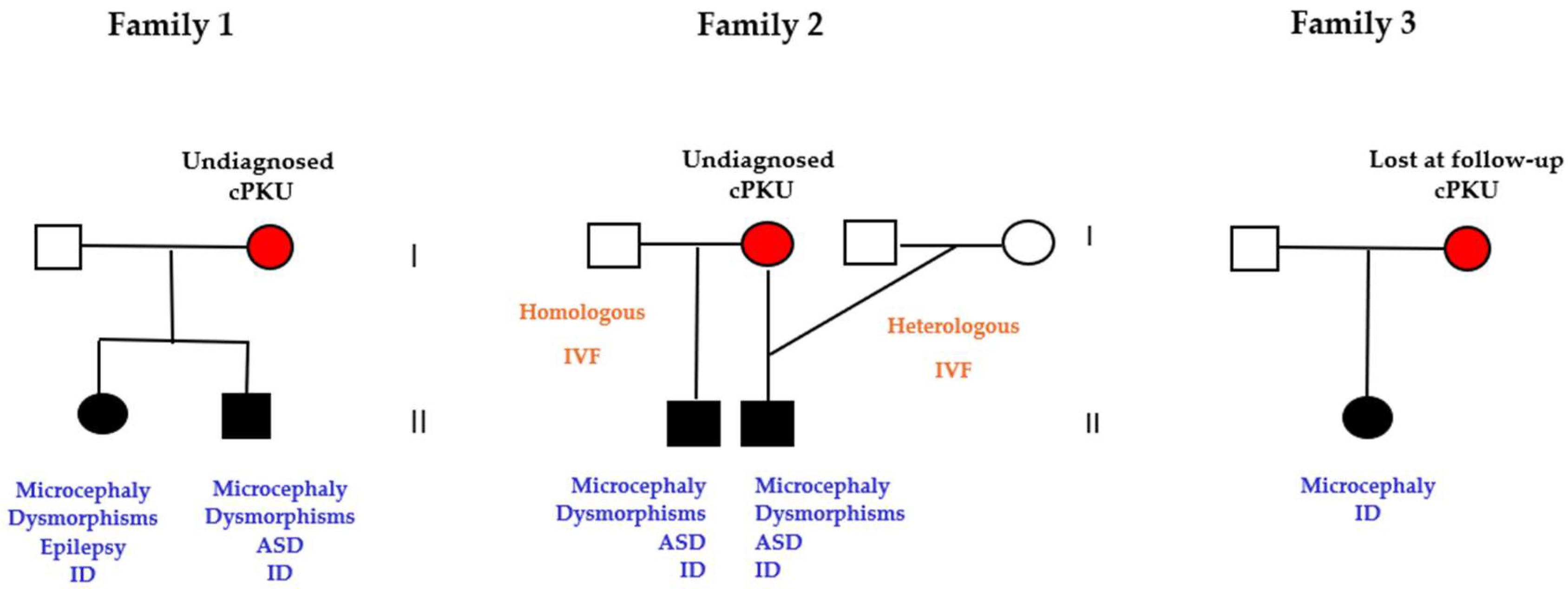

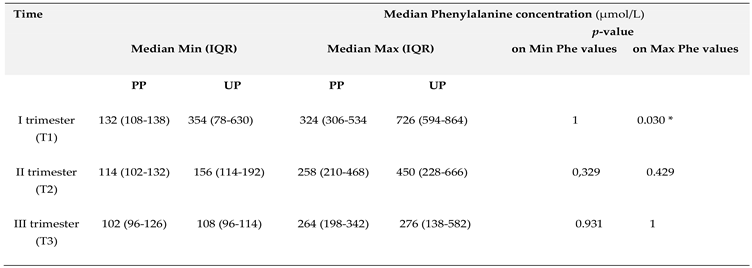

Maternal phenylketonuria syndrome (MPKUS) is the most serious pregnancy complication of women with phenylketonuria (PKU). High phenylalanine (Phe) levels are indeed embryotoxic for the fetus. A low-Phe diet started before conception and maintained throughout pregnancy ensures optimal blood Phe concentrations (120-360 μmol/L) and pregnancy outcome. Women with unplanned pregnancies are at higher risk of MPKUS and require a rapid and sustained reduction of blood Phe. In this retrospective study, we evaluated the effects of dietary intervention on Phe levels and on clinical parameters of the offspring at birth in a group of patients with PKU. We also describe the fetal outcome of unplanned and untreated PKU mothers. The cohort consisted of 13 patients for a total of 22 pregnancies: 16 successful pregnancies and 6 abortions. Pregnancies were divided into three groups: "Planned Pregnancies, PP (n=5)", "Unplanned Pregnancies, UP (n=6)" and "Unplanned and untreated Pregnancies UT (n=5)". Women in the UP group showed higher levels of Phe than women in the PP group especially during the first trimester. The offspring of the UP group showed no congenital malformations but lower median auxologic parameters at birth compared to PP, although not significantly different. The women in the UT group received the diagnosis of PKU after the birth of a MPKUS offspring. Low-Phe diet is critical to prevent MPKUS especially when started before conception or no later than 10th week of gestation. Intensive effort is necessary to avoid unplanned pregnancies and to identify undiagnosed PKU women at risk of MPKUS.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

2.2. Amino Acid Assay

2.3. Anthropometric Parameters

2.4. Dietary Management During Pregnancy

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

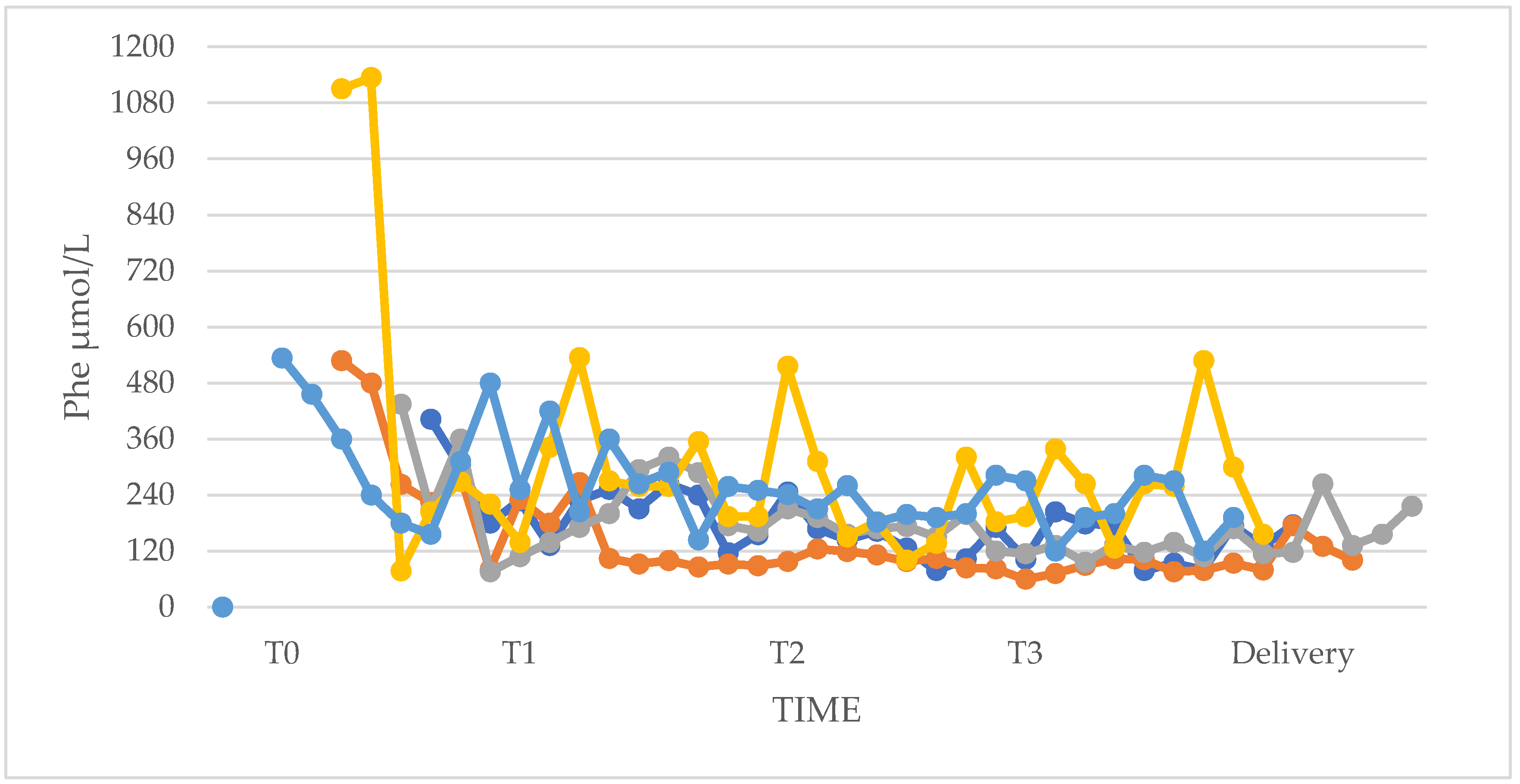

3.1. Phenylalanine and Tyrosine Levels and Phe/Tyr Ratio (PP and UP Groups)

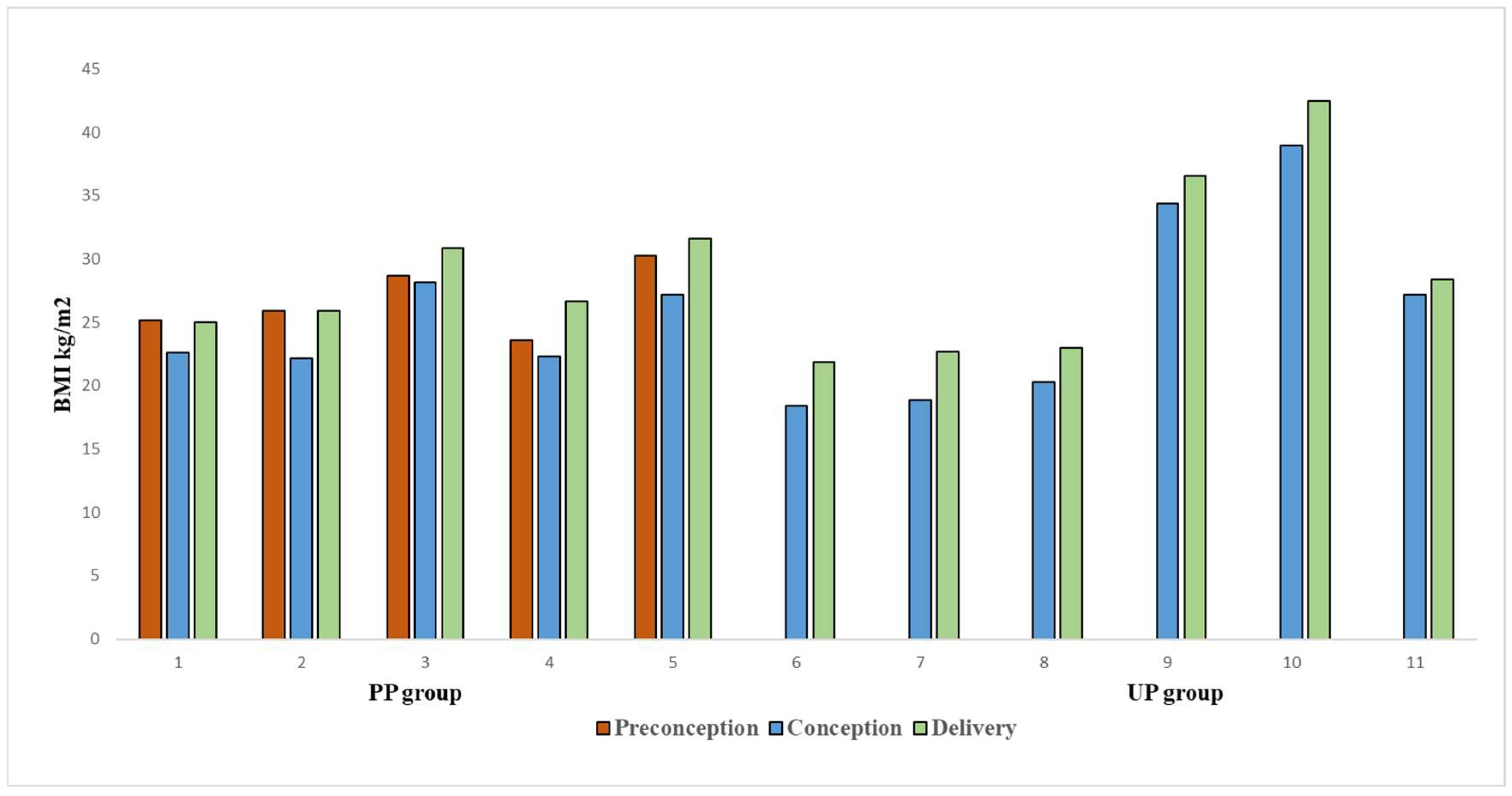

3.2. Anthropometric Characteristics of Women

3.3. Dietary Therapy

3.4. Phenylalanine Tolerance

3.5. Adherence to Dietary Therapy

3.6. Pregnancies of Previously Undiagnosed PKU Women (UT n=5)

3.7. Abortions of Unplanned Pregnancies

3.8. Offspring Neonatal Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Genetics. American Academy of Pediatrics: maternal phenylketonuria. Pediatrics 2001;107(2):427-428. [CrossRef]

- Burgard, P.; Bremer, H.J.; Bührdel, P.; et al. Rationale for the German recommendations for phenylalanine level control in phenylketonuria 1997. Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158(1):46-54. [CrossRef]

- Trefz, F.K.; Ullrich, K.; Cipcic-Schmidt, S.; Fünders-Bücker, B.; van Teeffelen-Heithoff, A.; Przyrembel, H. Prophylaxis and treatment of maternal phenylketonuria (MPKU). Statement of the Working Group for Pediatric Metabolic Diseases (APS). Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 1995;143:898-899.

- Adams, A.D.; Fiesco-Roa, M.Ó.; Wong, L.; Jenkins, G.P.; Malinowski, J.; Demarest, O.M.; Rothberg, P.G.; Hobert, J.A. ACMG Therapeutics Committee. Electronic address: documents@acmg.net. Phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency treatment and management: A systematic evidence review of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2023 Sep;25(9):100358. Epub 2023 Jul 20. PMID: 37470789. [CrossRef]

- Hanley, W.B.; Clarke, J.T.; Schoonheyt, W. Maternal phenylketonuria (PKU)--a review. Clin Biochem. 1987 Jun;20(3):149-56. PMID: 3308176. [CrossRef]

- Dent, C.E. Discussion of Armstrong MD: the relation of biochemical abnormality to the development of mental defect in phenylketonuria. Etiologic Factors in Mental Retardation: Report of the 23rd Ross Pediatric Research Conference. Ross Laboratories; 1957: 32- 33.

- Mabry, C.C.; Denniston, J.C.; Nelson, T.L.; Son, C.D. Maternal phenylketonuria: a cause of mental retardation in children without the metabolic defect. N Engl J Med. 1963; 269: 1404- 1408.

- Lenke, R.R.; Levy, H.L. Maternal phenylketonuria and hyperphenylalaninemia. An international survey of the outcome of untreated and treated pregnancies. N Engl J Med. 1980; 303(21): 1202- 1208.

- Koch, R.; Hanley, W.; Levy, H.; et al. “The Maternal Phenylketonuria Collaborative Study: 1984-2002” Pediatrics 2003; 112(6 Pt 2): 1523-1529.

- Lee, P.J.; Ridout, D.; Walter, J.H.; et al. “Maternal Phenylketonuria: report from the United Kingdom Registry 1978-97” Arch Dis Child 2005; 90: 143-146.

- Medical Research Council Working Party on Phenylketonuria “Phenylketonuria due to phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency: an unfolding story” BMJ 1993; 306: 115-119.

- Matalon, K.M.; Acosta, P.B.; Azen, C. Role of nutrition in pregnancy with phenylketonuria and birth defects. Pediatrics. 2003 Dec;112(6 Pt 2):1534-6. PMID: 14654660. [CrossRef]

- Widaman, K.F.; Azen, C. Relation of prenatal phenylalanine exposure to infant and childhood cognitive outcomes: results from the International Maternal PKU Collaborative Study. Pediatrics. 2003;112(6 Pt 2):1537-1543. [CrossRef]

- Waisbren, S.E.; Azen, C. Cognitive and behavioral development in maternal phenylketonuria offspring. Pediatrics. 2003;112: 1544-1547. [CrossRef]

- Vockley, J.; Andersson, H.C.; Antshel, K.M.; Braverman, N.E.; Burton, B.K.; Frazier, D.M.; et al. Phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency: diagnosis and management guideline. Genet Med. 2014;16(2):188–200. [CrossRef]

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 449: Maternal phenylketonuria. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Dec;114(6):1432-1433. PMID: 20134300. [CrossRef]

- Rouse, B.; Matalon, R.; Koch, R.; Azen, C.; Levy, H.; Hanley, W.; Trefz, F.; de la Cruz, F. Maternal phenylketonuria syndrome: congenital heart defects, microcephaly, and developmental outcomes. J Pediatr. 2000 Jan;136(1):57-61. PMID: 10636975. [CrossRef]

- Platt, L.D.; Koch, R.; Hanley, W.B.; Levy, H.L.; Matalon, R.; Rouse, B.; Trefz, F.; de la Cruz, F.; Güttler, F.; Azen, C.; Friedman, E.G. The international study of pregnancy outcome in women with maternal phenylketonuria: report of a 12-year study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Feb;182(2):326-33. PMID: 10694332. [CrossRef]

- Grohmann-Held, K.; Burgard, P.; Baerwald, C.G.O.; Beblo, S.; Vom Dahl, S.; Das, A.; Dokoupil, K.; Fleissner, S.; Freisinger, P.; Heddrich-Ellerbrok, M.; Jung, A.; Korpel, V.; Krämer, J.; Lier, D.; Maier, E.M.; Meyer, U.; Mühlhausen, C.; Newger, M.; Och, U.; Plöckinger, U.; Rosenbaum-Fabian, S.; Rutsch, F.; Santer, R.; Schick, P.; Schwarz, M.; Spiekerkötter, U.; Strittmatter, U.; Thiele, A.G.; Ziagaki, A.; Mütze, U.; Gleich, F.; Garbade, S.F.; Kölker, S. Impact of pregnancy planning and preconceptual dietary training on metabolic control and offspring's outcome in phenylketonuria. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2022 Nov;45(6):1070-1081. Epub 2022 Aug 22. PMID: 36054426. [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, D.; van Wegberg, A.M.J.; Ahring, K; Bik-Multanowski, M.; Blau, N.; Bulut, F.D.; Casas, K.; Didycz, B.; Djordjevic, M.; Federico, A.; Feillet, F.; Gizewska, M.; Gramer, G.; Hertecant, J.L.; Hollak, C.E.M.; Jørgensen, J.V.; Karall, D.; Landau, Y.; Leuzzi, V.; Mathisen, P.; Moseley, K.; Mungan, N.Ö.; Nardecchia, F.; Õunap, K.; Powell, K.K.; Ramachandran, R.; Rutsch, F.; Setoodeh, A.; Stojiljkovic, M.; Trefz, F.K.; Usurelu, N.; Wilson, C.; van Karnebeek, C.D.; Hanley, W.B.; van Spronsen, F.J. Can untreated PKU patients escape from intellectual disability? A systematic review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018 Aug 29;13(1):149. PMID: 30157945; PMCID: PMC6116368. [CrossRef]

- Maillot, F.; Cook, P.; Lilburn, M.; Lee, P.J. A practical approach to maternal phenylketonuria management. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007 Apr;30(2):198-201. Epub 2007 Mar 9. PMID: 17351826. [CrossRef]

- Scala, I.; Riccio, M.P.; Marino, M.; Bravaccio, C.; Parenti, G.; Strisciuglio, P. Large Neutral Amino Acids (LNAAs) Supplementation Improves Neuropsychological Performances in Adult Patients with Phenylketonuria. Nutrients. 2020 Apr 15;12(4):1092. PMID: 32326614; PMCID: PMC7230959. [CrossRef]

- Bertino, E.; Spada, E.; Occhi, L.; Coscia, A.; Giuliani, F.; Gagliardi, L.; Gilli, G.; Bona, G.; Fabris, C.; De Curtis, M.; Milani, S. Neonatal anthropometric charts: the Italian neonatal study compared with other European studies. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010 Sep;51(3):353-61. PMID: 20601901. [CrossRef]

- Waisbren, S.E.; Hamilton, B.D.; St. James, P.; Shilo, S.; Levy, H.L.;. Psychological factors in maternal phenylketonuria: women’s adherence to medical recommendations. Am J Pub Health. 1995;12:1636–41. [CrossRef]

- Galan, H.L.; Marconi, A.M.; Paolini, C.L.; Cheung, A.; Battaglia, F.C. The transplacental transport of essential amino acids in uncomplicated human pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009. [CrossRef]

- van Wegberg, A.M.J.; MacDonald, A.; Ahring, K.; Bélanger-Quintana, A.; Blau, N.; Bosch, A.M.; Burlina, A.; Campistol, J.; Feillet, F.; Giżewska, M.; Huijbregts, S.C.; Kearney, S.; Leuzzi, V.; Maillot, F.; Muntau, A.C.; van Rijn, M.; Trefz, F.; Walter, J.H.; van Spronsen, F.J. The complete European guidelines on phenylketonuria: diagnosis and treatment. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017 Oct 12;12(1):162. PMID: 29025426; PMCID: PMC5639803. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wan, K.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liang, Y.; Wang, X.; Feng, P.; He, F.; Zhou, R.; Yang, D.; Jia, H.; Cheng, G.; Shimokawa, T.; Assessing the relationship between pregravid body mass index and risk of adverse maternal pregnancy and neonatal outcomes: prospective data in Southwest China. Sci Rep. 2021 Apr 7;11(1):7591. PMID: 33828166; PMCID: PMC8027183. [CrossRef]

- Teissier, R.; Nowak, E.; Assoun, M; et al. Maternal phenylketonuria: low phenylalaninemia might increase the risk of intra uterine growth retardation. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2012;35(6):993- 999. [CrossRef]

- Bhasin, K.K.; van Nas, A.; Martin, L.J.; Davis, R.C.; Devaska, S.U.; Lusis, A.J. Maternal low-protein diet or hypercholesterolemia reduces circulating essential amino acids and leads to intrauterine growth restriction. Diabetes 2009 58:559–566 . [CrossRef]

- van Spronsen, F.J.; van Wegberg, A.M.; Ahring, K.; Bélanger-Quintana, A; Blau, N.; Bosch, A.M.; Burlina, A.; Campistol, J.; Feillet, F.; Giżewska, M.; Huijbregts, S.C.; Kearney, S.; Leuzzi, V.; Maillot, F.; Muntau, A.C.; Trefz, F.K.; van Rijn, M.; Walter, J.H.; MacDonald, A. Key European guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with phenylketonuria. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Sep;5(9):743-756. Epub 2017 Jan 10. PMID: 28082082. [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, A.; Leheup, B.; Battaglia-Hsu, S.F.; Jonveaux, P.; Jeannesson, E.; Feillet, F. Undiagnosed phenylketonuria in parents of phenylketonuric patients, is it worthwhile to be checked? Mol Genet Metab. 2013;110 Suppl:S62-5. Epub 2013 Sep 1. PMID: 24051226. [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, Y.; Sivri, H.S. Maternal phenylketonuria in Turkey: outcomes of 71 pregnancies and issues in management. Eur J Pediatr. 2019 Jul;178(7):1005-1011. Epub 2019 May 3. PMID: 31053953. [CrossRef]

- Bouchlariotou, S.; Tsikouras, P.; Maroulis, G. Undiagnosed maternal phenylketonuria: own clinical experience and literature review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009 Oct;22(10):943-8. PMID: 19557660. [CrossRef]

- Gokmen, T.; Oguz, S.S.; Altug, N.; Akar, M.; Erdeve, O.; Dilmen, U. A case of maternal phenylketonuria syndrome presenting with unilateral renal agenesis. J Trop Pediatr. 2011 Apr;57(2):138-40. Epub 2010 Jul 1. PMID: 20595329. [CrossRef]

- Hanley, W.B. Finding the fertile woman with phenylketonuria. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008 Apr;137(2):131-5. Epub 2008 Feb 8. PMID: 18262326. [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, A.; Leheup, B.; Battaglia-Hsu, S.F.; Jonveaux, P.; Jeannesson, E.; Feillet, F. Undiagnosed phenylketonuria in parents of phenylketonuric patients, is it worthwhile to be checked? Mol Genet Metab. 2013;110 Suppl:S62-5. Epub 2013 Sep 1. PMID: 24051226. [CrossRef]

| Pregnant Women with PKU | n=13 |

| Pregnancies (including abortions) | n=22 |

| PKU classification | Classic PKU =8 Mild PKU =3 Mild HPA =2 |

| Historical tolerance (dietary Phe; mg/day) | Range 340-2100 |

| Maternal age at conception (years) | Mean (SD) 30.2 ± 4.8 Range 24-39 |

|

|

Offspring PP (N=5) Males=1, Females=4 |

Offspring UP (N=5) Male=5, Female=0 |

p Value | |

|

Birth weight (Kg) Median (IQR) |

2.79 (2.74-3.33) |

2.40 (2.30-2.85) |

0.690 |

|

Weight percentiles Median (IQR) |

21 (19-74) |

5 (3-10) |

0.151 |

|

Length (cm) Median (IQR) |

49 (47-49) |

45 (45-50) |

0.600 |

|

Length percentiles Median (IQR) |

48 (19-56) |

8 (4-21) |

0.310 |

|

Head circumference (cm) Median (IQR) |

33 (32.5-34) |

32.5 (32-33) |

0.800 |

|

Head circumference percentiles Median (IQR) |

40(40-47) |

23 (2-27) |

0.548 |

|

Apgar index Median (IQR) |

8.0 (8.0-9.0) |

7.0 (7.0-8.0) |

0.400 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).