1. Introduction

Pesticides play a crucial role in agriculture by protecting crops from pests, diseases, and weeds. They enhance food production and contribute to global food security. However, the widespread and often indiscriminate use of pesticides has led to their accumulation in the environment, presenting significant challenges and risks[

1].One key concern is the contamination of water sources, both surface water and groundwater, with pesticide residues. Pesticides can enter water bodies through runoff from agricultural fields, leaching from soil, and improper handling or disposal practices. This contamination poses a threat to aquatic ecosystems, drinking water supplies, and non-target organisms, including beneficial insects, birds, and mammals[

2]. To address this issue, effective and environmentally-friendly pesticide treatment methods are essential. First and foremost, the removal of pesticide residues from water sources is necessary to safeguard human health. Consumption of pesticide-contaminated water can lead to acute or chronic toxic effects, especially if the concentrations exceed regulatory limits[

3]. Furthermore, the preservation of aquatic ecosystems is crucial. Pesticides can have detrimental effects on various aquatic organisms, such as fish, amphibians, and invertebrates. Even at low concentrations, these chemicals can disrupt reproductive systems, impair growth and development, and induce behavioral changes in aquatic life. By treating water sources contaminated with pesticides, we can help protect the balance and biodiversity of aquatic ecosystems[

4].

The use of environmentally-friendly methods for pesticide treatment is vital to minimize the negative impact on the environment. Traditional treatment methods, such as activated carbon filtration or chemical precipitation, have limitations in terms of efficiency and selectivity. These methods may also generate harmful byproducts or require extensive post-treatment processes[

3]. Emphasizing the importance of environmentally-friendly alternatives, advanced oxidation processes are gaining recognition. AOPs offer effective treatment solutions while considering environmental compatibility. By utilizing oxidation techniques like ozone, hydrogen peroxide, and UV radiation, AOPs can degrade pesticide residues and transform them into harmless byproducts. This approach minimizes the introduction of additional pollutants and promotes the sustainable management of pesticide-contaminated water sources[

5]. Pesticide treatment plays a crucial role in protecting human health, preserving aquatic ecosystems, and ensuring environmental sustainability. With the increasing need for safer and more effective methods, the development and implementation of environmentally-friendly approaches, such as AOPs, are essential for addressing pesticide contamination and mitigating its adverse effects on ecosystems and society at large[

6].

Advanced oxidation processes are a category of chemical treatment methods used to facilitate the degradation of organic contaminants in water and wastewater. AOPs employ the generation of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (

•OH) to oxidize and break down various organic compounds into harmless substances or lower toxicity intermediates[

7]. In the context of pesticide treatment, AOPs offer a promising solution for the removal of pesticide residues from water sources. AOPs can effectively degrade and eliminate the pesticide residues[

8,

9]. It involves the application of advanced oxidation techniques like ozone (O

3), hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), and ultraviolet (UV) radiation, either individually or in combination, to generate

•OH radicals. These radicals possess strong oxidative power, enabling them to attack and break the chemical bonds of various organic compounds, including pesticide molecules[

10]. The AOPs' potential lies in their ability to degrade a wide range of organic contaminants, including highly resistant pesticides. They can effectively transform complex pesticide structures into simpler and less toxic byproducts. By using AOPs, it becomes possible to treat water contaminated with different pesticide classes, such as herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides[

5,

11]. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) offer advantages in terms of efficiency, selectivity, and environmental compatibility. They can be tailored to target specific pesticide compounds based on their reactivity and structure. Additionally, AOPs are capable of mineralizing pesticides into carbon dioxide (CO

2) and water (H

2O), reducing or eliminating the presence of potentially harmful byproducts[

12]. The objective of this review is to explore and evaluate different types of Advanced Oxidation Processes in treating wastewater contaminated with pesticides. By analyzing existing studies and research findings, the review aims to compare the effectiveness of various advanced oxidation methods in terms of their efficiency, advantages, limitations, and applicability in the practical treatment of pesticide-contaminated wastewater, and suggestions for future research are proposed.

2. Pesticides in Aqueous Environment

2.1. Sources of Pesticide Contamination in Aqueous Environment

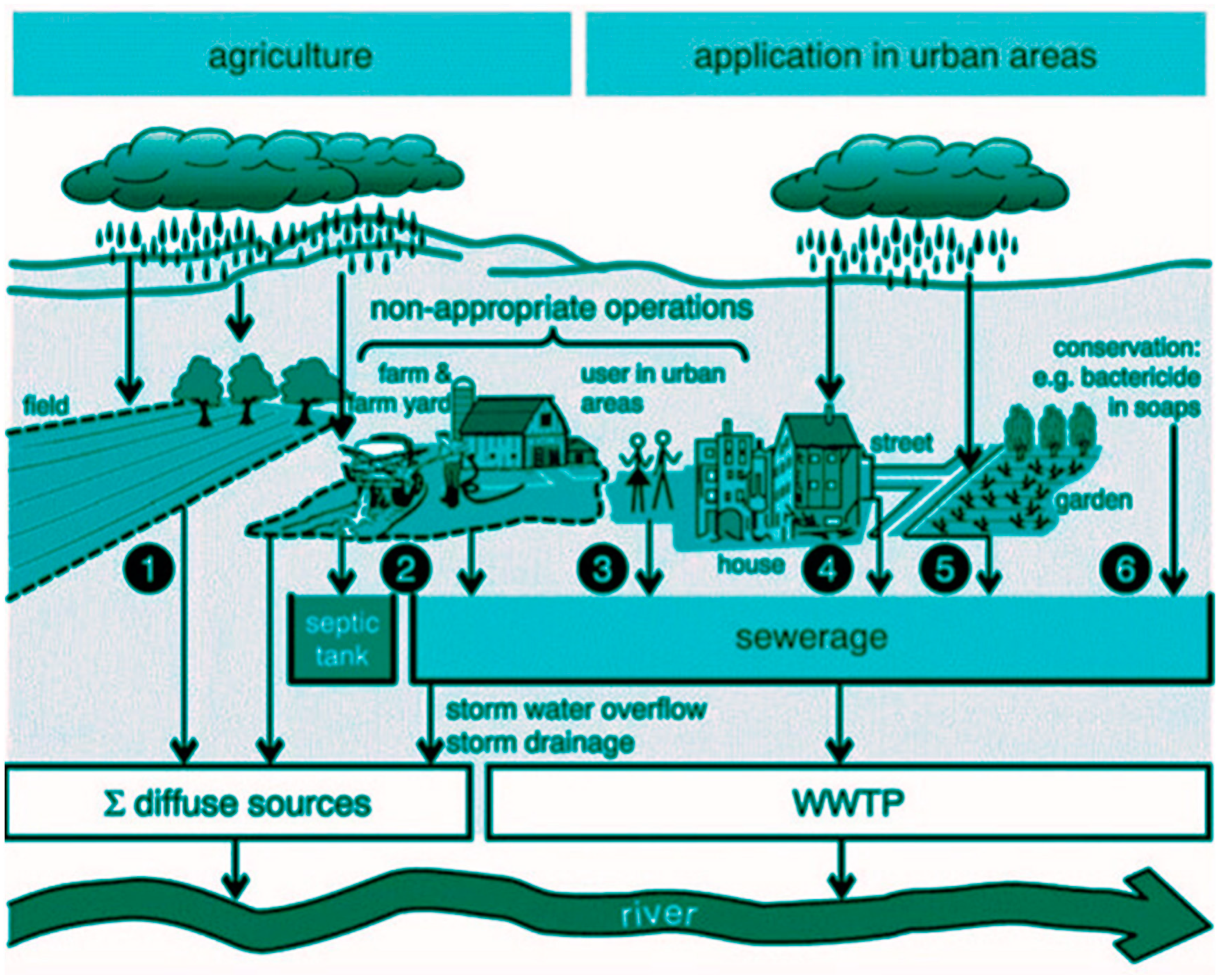

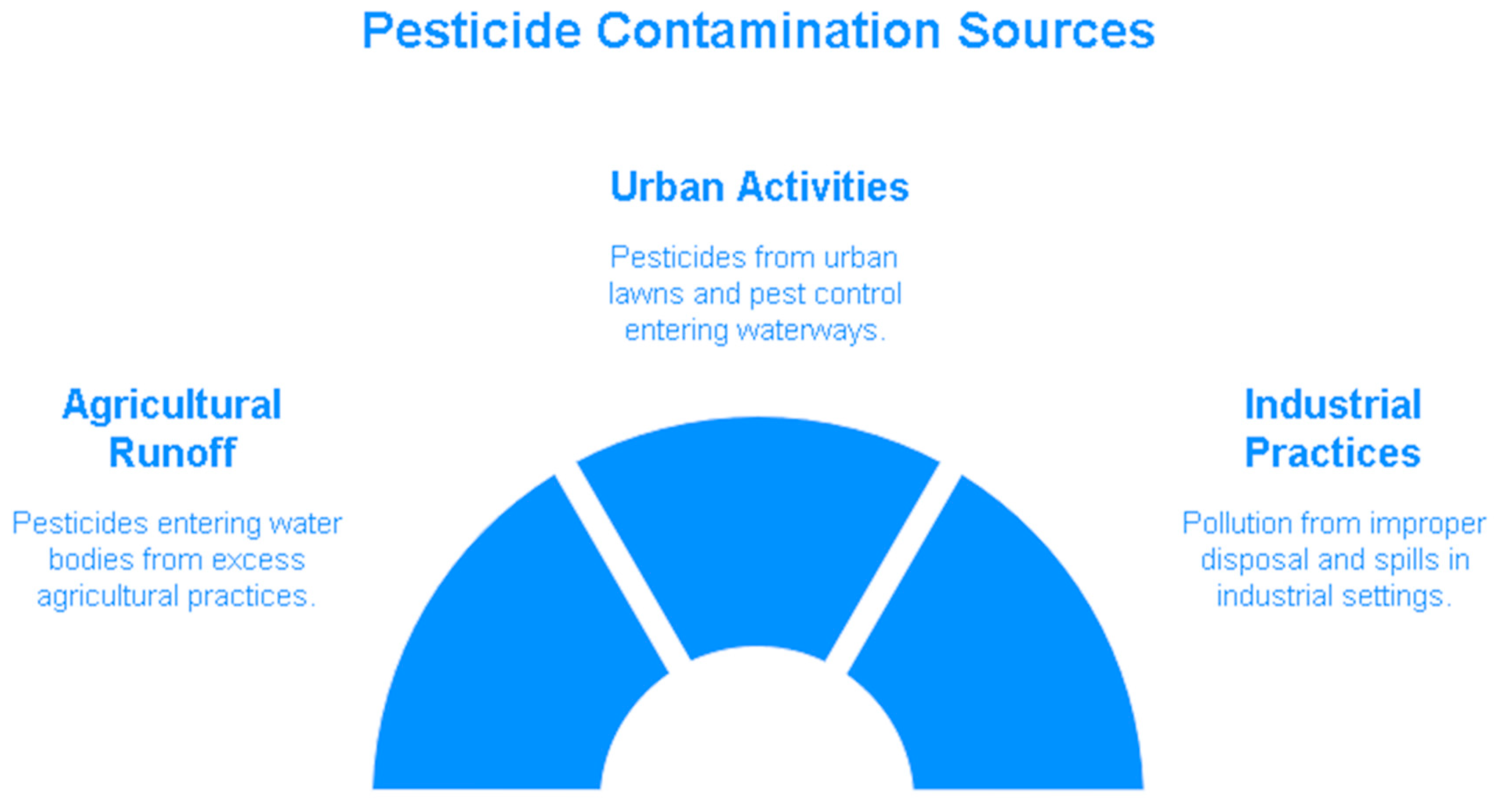

Pesticide contamination in wastewater stems from various sources, primarily agricultural runoff and urban activities (

Figure 1). In agricultural settings, pesticides are widely used to protect crops from pests and diseases[

13]. However, excess application or improper handling can lead to runoff during rainfall events, carrying pesticides into nearby water bodies or infiltrating groundwater. Additionally, urban areas contribute to pesticide contamination through the use of lawn and garden pesticides, as well as pest control measures in households and public spaces (

Figure 2). Stormwater runoff from urban surfaces can transport these chemicals into sewage systems, further exacerbating contamination issues[

14]. Furthermore, industrial activities such as manufacturing and chemical production may also contribute to pesticide pollution through improper disposal practices or accidental spills, adding to the complexity of managing pesticide contamination in wastewater systems. Efforts to mitigate pesticide pollution require a multifaceted approach, including improved agricultural practices, stricter regulations on pesticide use, and enhanced wastewater treatment methods to safeguard water quality and ecosystem health[

13].

2.2. Health and Environmental Impacts of Pesticide Pollution

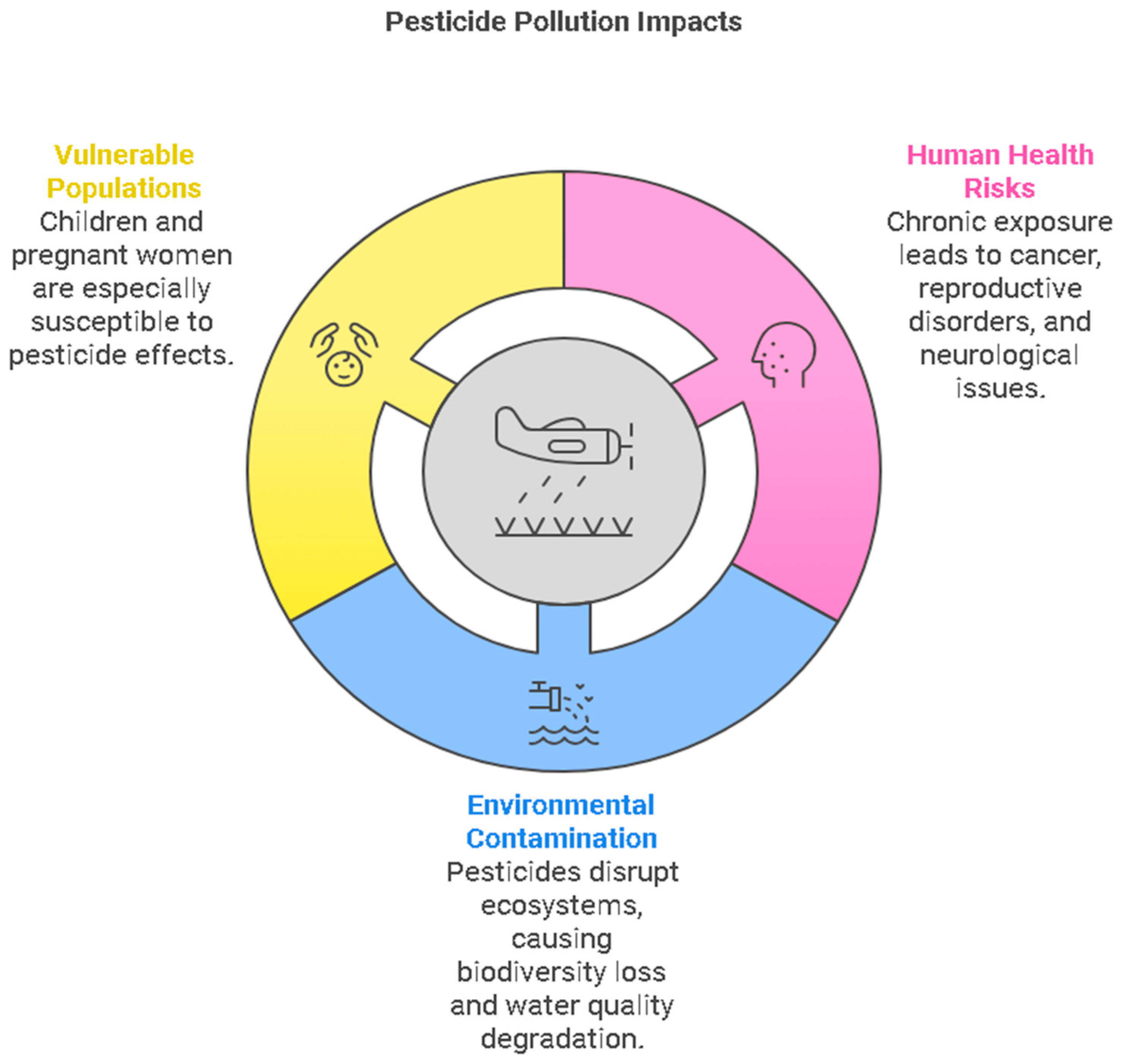

Pesticide pollution presents significant health and environmental risks to both human populations and ecosystems (

Figure 3). Human health impacts arise from exposure pathways like consuming contaminated food and water, inhaling pesticide residues, and direct skin contact during agricultural activities. Chronic pesticide exposure is associated with various health issues, including cancer, reproductive disorders, and neurological ailments, with children and pregnant women being especially vulnerable[

15]. Environmental consequences encompass soil, water, and air contamination, disrupting ecosystems, causing biodiversity loss, and affecting non-target organisms like beneficial insects and aquatic life through toxicity and habitat disturbances. Pesticides persist in the environment, leading to bioaccumulation and biomagnification, with long-term repercussions on ecosystems. The degradation of water quality due to pesticide runoff from agricultural areas and improper disposal practices threatens aquatic life, safe drinking water sources, and agricultural productivity by compromising essential water resources[

16].

3. Overview of Different Advanced Oxidation Processes and Their Underlying Mechanisms of Wastewater Treatment

3.1. Fenton and Fenton-Like Process

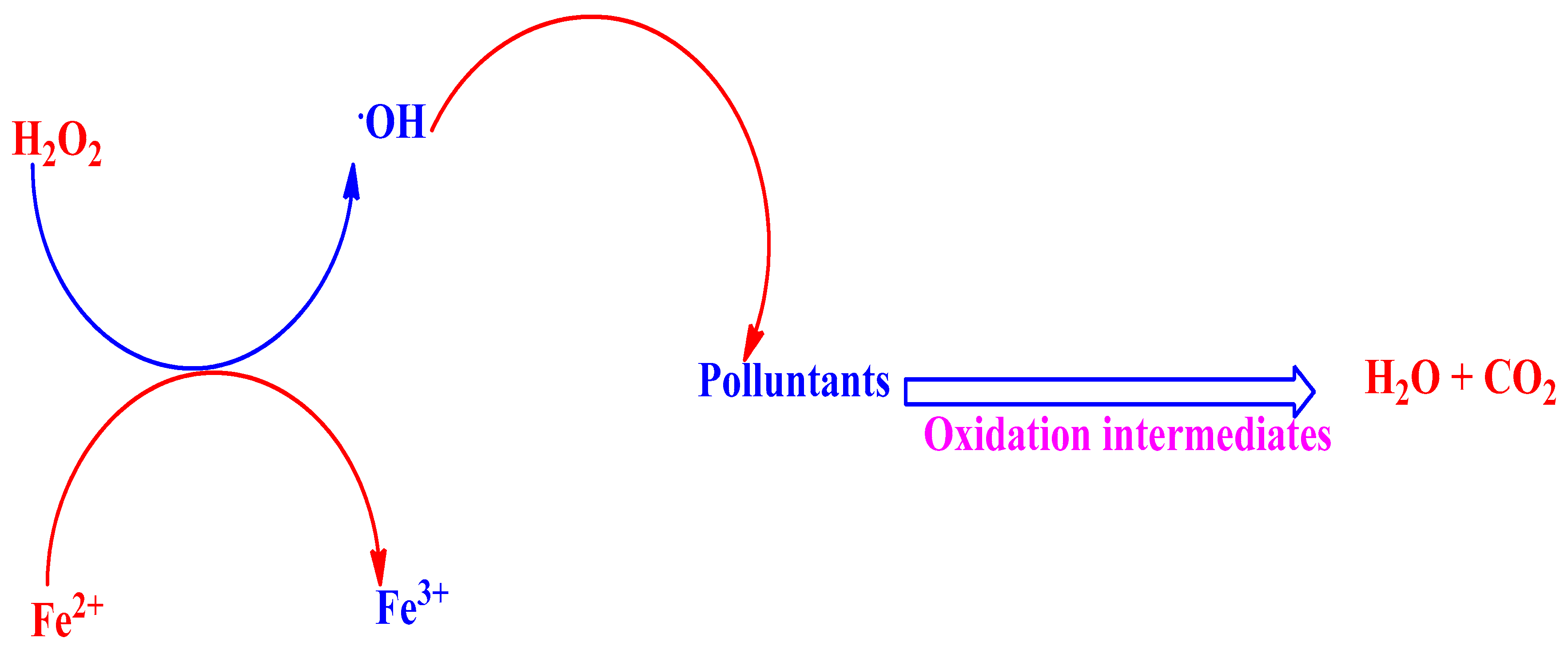

Fenton's reaction relies on the use of hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) and a catalyst, typically iron (Fe), to generate hydroxyl radicals[

17,

18]. The iron catalyst converts hydrogen peroxide to highly reactive hydroxyl radicals at a suitable pH[

19]. These hydroxyl radicals can rapidly oxidize various organic pollutants, breaking them down into simpler and less harmful compounds. The underlying mechanism involves the reaction between iron catalyst and hydrogen peroxide, forming hydroxyl radicals via the Fenton reaction (Eq. 1.1)[

18]. Building upon this fundamental mechanism, various advanced oxidation methods have been developed, such as photo-Fenton (PF), electro-Fenton (EF), photo electro-Fenton (PEF), and solar photo electro-Fenton (SPEF)[

20,

21,

22]. These methodologies aim to enhance the circulation of Fe(III)/Fe(II) species and amplify the generation of hydroxyl radicals (

) to effectively degrade recalcitrant contaminants. The mechanisms underlying these advanced processes involve: 1) In-situ electro-generation of H

2O

2 through the two-electron reduction of molecular oxygen (O

2) on a carbonaceous cathode (Eq. 1.2); 2) Utilization of an electric field to facilitate the in-situ regeneration of Fe(II) species at the cathode (Eq. 1.3)[

22]; 3) Accelerated conversion of Fe(III) to Fe(II) species via photocatalytic reactions, coupled with the decomposition of H

2O

2 to generate additional hydroxyl radicals (Eqs. 1.4~1.5)[

20,

21].

The oxidation mechanism for the Fenton process is shown in

Figure 4. Based on this principle, Fenton process has been widely used in various kinds of organic wastewater treatment. The degradation efficiency of organic pollutants in the Fenton process depends on operation parameters such as wastewater pH, concentration of Fenton reagent, and initial organic pollutants concentration, of which wastewater pH is a highly important parameter[

19].

3.2. Ozonation-Based Advanced Oxidation Process

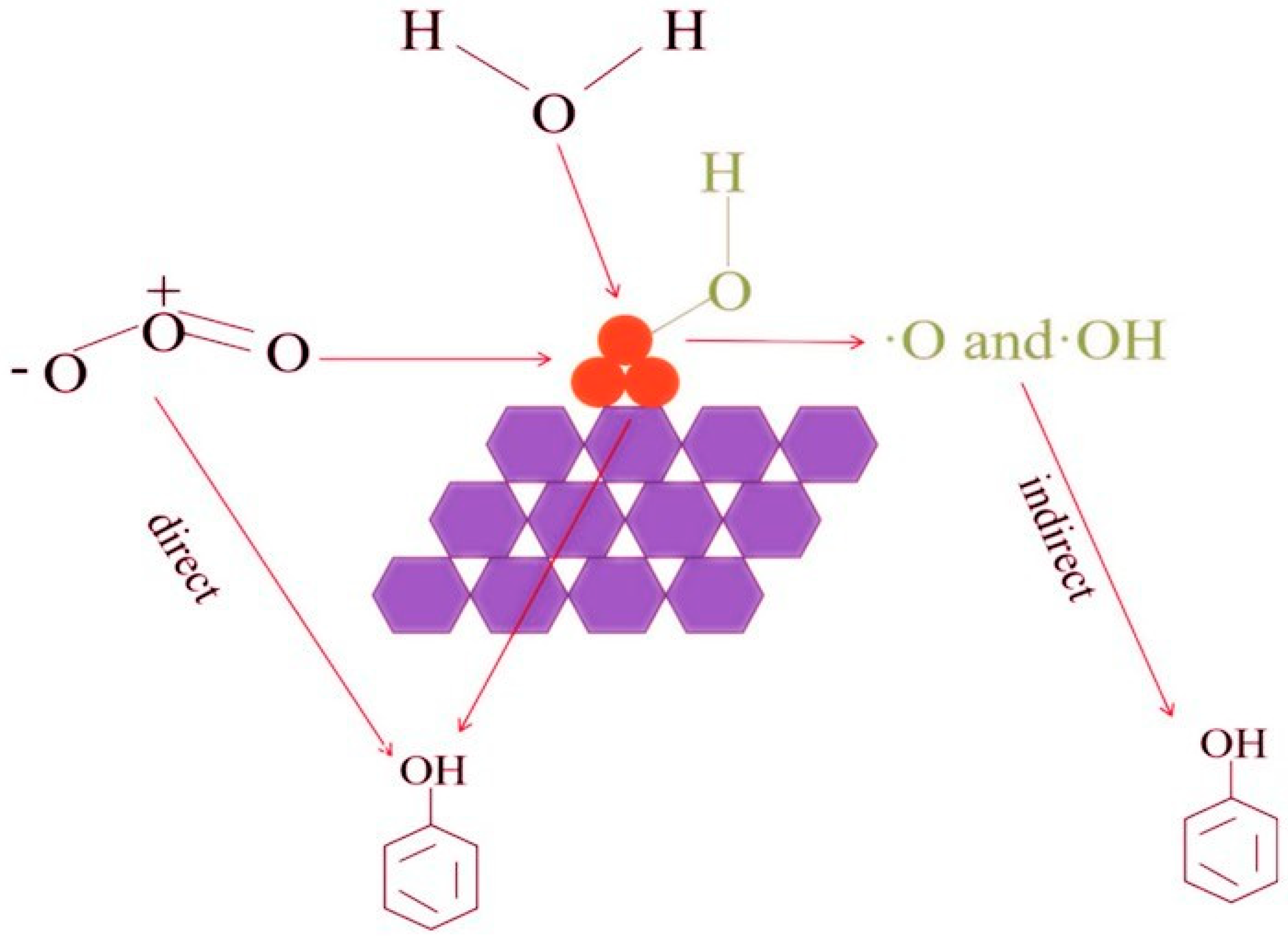

Ozonation-based advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) primarily degrade and mineralize refractory contaminants through two main mechanisms: 1) Direct ozonation involves ozone reacting directly with target contaminants. This process encompasses redox reactions, cycloaddition reactions, electrophilic substitution reactions, and nucleophilic reactions[

23]. 2) Another approach entails utilizing various physical or chemical methods to catalytically generate high redox potential reactive oxygen species (ROS) from ozone, notably hydroxyl radical (

)[

25,

26,

27,

28]. Indirect catalytic ozonation has emerged as the predominant approach for degrading and mineralizing refractory organic compounds. The synergetic effect between ozone and hydrogen peroxide has long been recognized and extensively explored by researchers for the mitigation of emerging contaminants, such as pesticides, dyes, endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), pharmaceuticals, and personal care products (PPCPs)[

29,

30]. This synergistic reaction between ozone and hydrogen peroxide generates powerful reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly the hydroxyl radical (

) (Eq. 1.6), significantly enhancing the efficiency of removing various ozone-resistant pollutants.

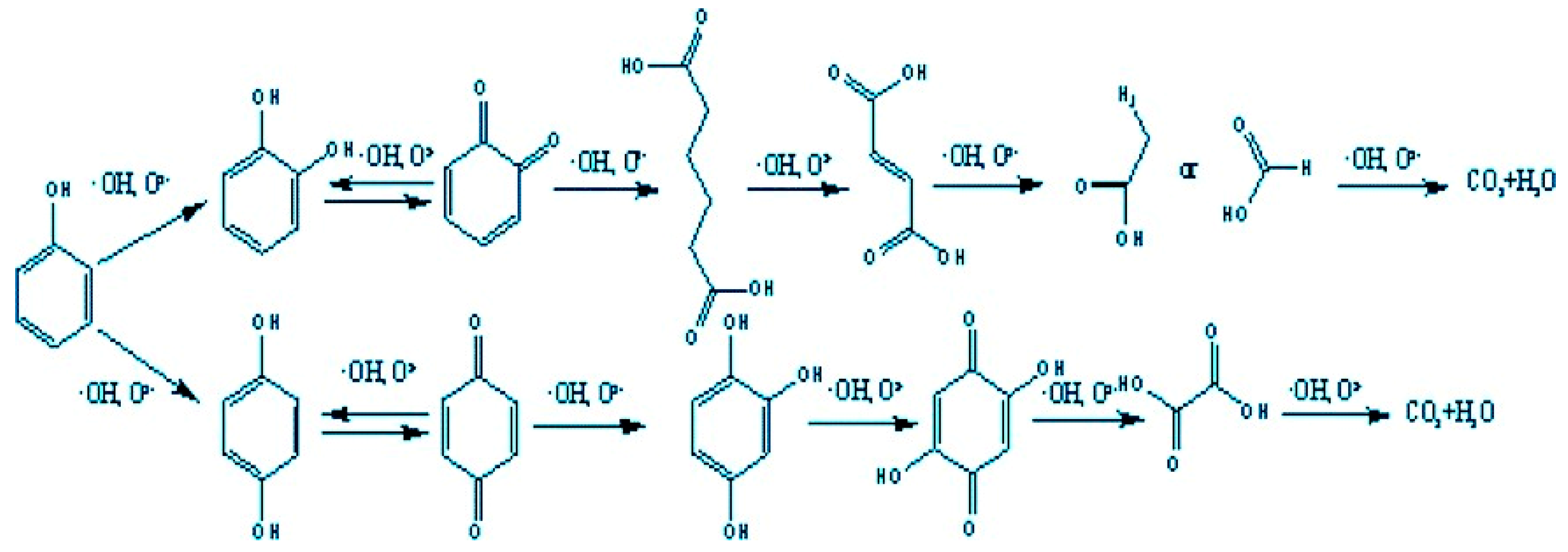

For example,

Figure 5 shows the probable pathway of phenol degradation in the catalytic ozonation process over MgO/AC. Firstly, electrophilic hydroxyl radicals preferentially attack adjacent or para position of benzene ring in the reaction, and phenol is oxidized to the catechol or hydroquinone. The hydroxyl radicals may also attack the 2 positions of p-benzoquinone, and generate 1, 2, 4-benzenetriol, 2, 5-dihydroxy-1, 4-benzoquinone and acetic acid. During the reaction, it was also speculated that there might be macromolecular substances such as acid anhydride or ester by MS analysis, and the specific formation process needs to be further studied. The final products of both these possible pathways are CO

2 and H

2O, as shown in

Figure 6 [

31].

3.3. Photocatalysis

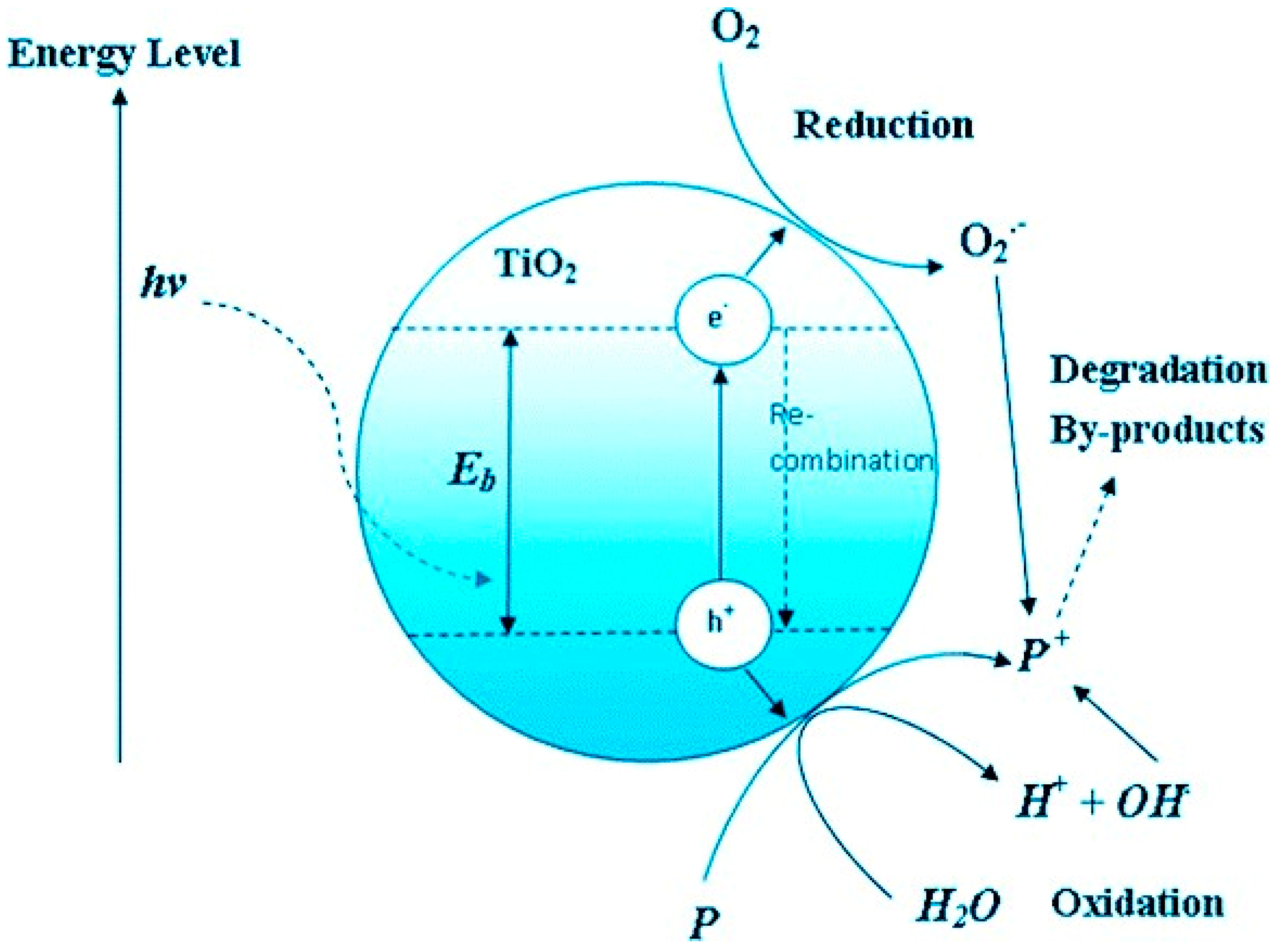

Photocatalysis involves the use of both a catalyst and light energy to generate highly reactive species that can degrade organic pollutants[

32,

33,

34]. The catalyst, usually a semiconductor material such as titanium dioxide (TiO

2) or zinc oxide (ZnO), absorbs photons and creates electron-hole pairs. These charge carriers then participate in redox reactions, leading to the degradation of pollutants. The underlying mechanism includes the generation of hydroxyl radicals (

) through reactions between the catalyst and species like water or oxygen[

34,

35,

36]. A prerequisite for initiating a photocatalytic reaction is that the energy imparted by photons onto the photocatalyst surpasses the energy gap (approximately 3.2 eV for titanium dioxide) between the valence band (VB) and the conduction band (CB). Upon absorption of light energy equal to or exceeding 3.2 eV, electrons residing in the VB transition to the CB, resulting in the generation of photogenerated electrons (CB-e

−) while leaving behind corresponding holes in the VB (VB-h

+) (Eq. 1.7). In the presence of moisture in the ambient air, photogenerated electrons (CB-e

−) and holes (VB-h

+) interact with oxygen and water molecules, respectively. Photogenerated electrons (CB-e

−) exhibit strong reducibility, facilitating the reduction of surface-bound oxygen molecules to superoxide free radicals (

), which subsequently undergo a cascade of reactions leading to the formation of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) (Eqs. 1.8~1.10). Conversely, the VB holes (VB-h

+) possess robust oxidation potential, enabling the oxidation of hydroxide ions (−OH) (including those within water molecules) to generate free hydroxyl radicals (

) simultaneously (Eqs. 1.11~1.12)[

37,

38]. The hydroxyl radical (

) emerges as the principal oxidant in the photocatalytic oxidative degradation of organic pollutants, owing to its formidable oxidation capabilities.

When exposed to radiation, photocatalysts become activated, generating highly reactive photo-induced charge carriers that interact with pollutants, as depicted in

Figure 7. This process allows for the efficient removal of pollutants at ambient temperature and pressure, offering a solution to the high energy consumption typically associated with conventional methods.

3.4. UV/H2O2 Process

UV/H

2O

2 has demonstrated efficacy in degrading macromolecular organic pollutants in water, leading to the formation of smaller molecule organic species[

39,

40]. This process exhibits notable removal efficiency towards fluorescent compounds, substances containing benzene rings, or those with double bonds owing to the formation of high redox potential hydroxyl radical (Eq. 1.13)[

39,

41]. The UV/H

2O

2 process employs three main degradation mechanisms: Firstly, hydrogen peroxide's strong oxidizing properties enable direct oxidation of organic compounds in water. Secondly, UV irradiation initiates molecular bond dissociation, leading to the breakdown of organic pollutants. Thirdly, under UV irradiation, hydrogen peroxide undergoes photolysis, generating hydroxyl radicals (

) that are instrumental in oxidizing and decomposing organic pollutants. This oxidation facilitated by hydroxyl radicals constitutes the primary reaction pathway in the UV/H

2O

2 process.

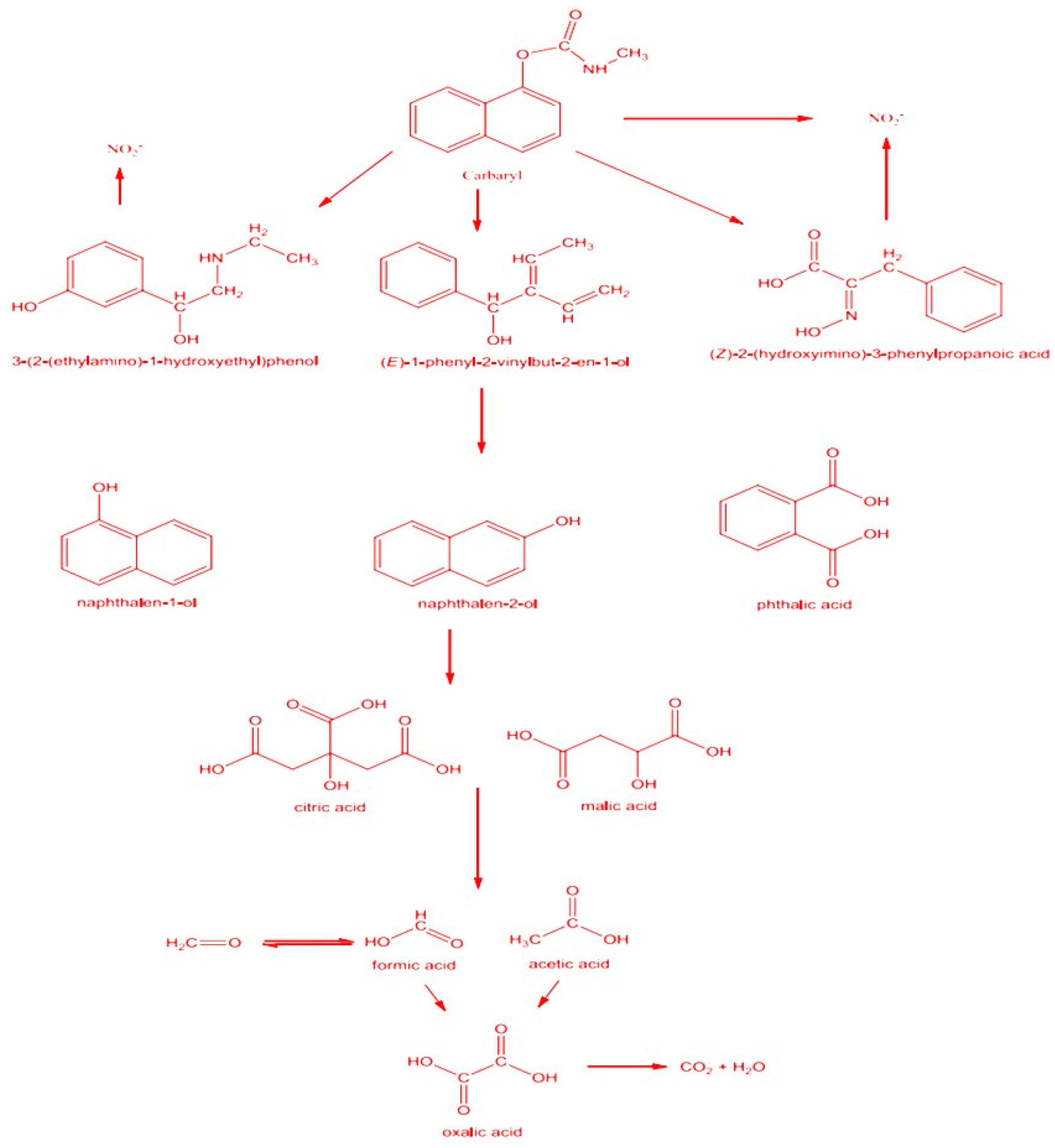

Hydroxyl radicals (·OH) initiate their attack on the carbaryl molecule, causing the disruption of chemical bonds within carbaryl. This reaction can also result in the hydroxylation of the carbaryl molecule, incorporating hydroxyl groups (OH-) into its structure. As a consequence, subsequent reactions may lead to the breakdown of the carbaryl ring, fragmenting the compound into smaller components and generating intermediate compounds. These intermediates, including hydroxylated carbaryl derivatives and other by-products, are formed throughout the degradation process[

42]. Further oxidation and decomposition reactions, facilitated by hydroxyl radicals (·OH), proceed to break down complex structures into simpler, more readily mineralized compounds. The degradation sequence progresses until complete mineralization of carbaryl is achieved, yielding non-toxic inorganic end products such as carbon dioxide (CO

2) and water. The monitoring of by-products formed during the degradation process remains essential to validate the efficiency and safety of the treatment[

42]. In

Figure 8, the assessment of carbaryl elimination utilizing UV and UV/H

2O

2 processes was explored. It became evident that the use of UV alone without H

2O

2 for carbaryl removal exhibited minimal effectiveness. Conversely, the combination of UV irradiation with H

2O

2 significantly hastened the elimination process, resulting in complete degradation within 75 minutes, attributed to the heightened generation of hydroxyl radicals facilitated by H

2O

2. The postulated pathway mechanism was based on the analysis of aromatic intermediates, carboxylic acids, and anions through GC-MS and IC techniques. Key indicators supporting carbaryl decomposition by UV/H

2O

2 included variations in dissolved oxygen levels, pH, acidity concentrations, and formaldehyde presence. The results underscore that carbaryl pesticides are effectively degraded through UV and UV/H

2O

2 processes, highlighting the potential of this approach for pesticide removal in drinking water and wastewater treatment applications.

3.5. UV/O3 Process

The UV/O

3 process represents an advanced photochemical oxidation method where ozone and ultraviolet radiation are introduced simultaneously. This approach capitalizes on ozone's oxidative properties and ultraviolet light's photolytic capabilities, utilizing the active species generated from ozone decomposition under ultraviolet light to oxidize organic matter. Glaze et al. outlined the synergistic mechanisms between ultraviolet light and ozone, (Eq. 1.14~17)[

43]. Ozone (O

3) undergoes photolysis under UV radiation, resulting in the production of hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2). Subsequently, hydrogen peroxide reacts with ozone to generate hydroxyl radicals (

), a process known as the peroxone process. Additionally, hydrogen peroxide can independently produce hydroxyl radicals (

) under UV radiation.

In the combination of ultraviolet and ozone, another active species,

, is generated, which significantly contributes to the degradation of organic pollutants in water[

44]. An outstanding advantage of this combined process is its ability to promote the indirect reaction of ozone and facilitate the transformation of organic compounds from ground state molecules to active species. This creates favorable conditions for the oxidation of organic compounds, thereby enhancing their degradation efficiency.

3.6. Electrochemical Oxidation

Electrochemical oxidation involves the application of electrical energy to drive the oxidation of pollutants in an aqueous solution, resulting in their breakdown into less harmful substances. In AOPs, reactive species, primarily hydroxyl radicals (•OH), are generated, which are powerful oxidizers capable of decomposing a wide range of organic contaminants [

45].

Figure 9 illustrates the mechanism of electrochemical degradation of organic pollutants using both non-active and active anodes.

4. Advantages and Limitations of Advanced Oxidation Processes in the Dechlorination of Pesticide Pollutants

Table 1.

Comparisons of different AOPs based on their advantages and limitations in the Dechlorination of Pesticide Pollutants.

Table 1.

Comparisons of different AOPs based on their advantages and limitations in the Dechlorination of Pesticide Pollutants.

| Advanced Oxidation Process (AOPs) |

Advantages |

Limitations |

References |

| Photocatalysis |

- Broad applicability: Photocatalysis can effectively degrade a wide range of pesticides, including various chemical classes.

- High degradation efficiency: The generation of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (∙OH) through photocatalysis enables efficient and complete pesticide degradation.

- Regeneration of catalyst: Catalyst materials like TiO2 or ZnO can be regenerated and reused, leading to cost savings.

|

- Catalyst selectivity: Not all pesticides can be efficiently degraded by photocatalysis, as the process's effectiveness depends on the pesticide's adsorption and reaction properties.

- Light dependency: Photocatalytic reactions require a light source, preferably ultraviolet (UV) radiation. This dependency may limit operation under certain conditions and increase energy consumption.

- Catalyst recovery and recycling challenges: Separating the catalyst from the treated water or waste stream can be challenging, affecting the overall efficiency and practicality of photocatalysis.

|

[46,47] |

| Ozonation process |

- Wide pesticide applicability: Ozone is highly reactive and effective in degrading various pesticide classes, including herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides.

- Rapid reaction kinetics: Ozonation offers fast reaction rates, resulting in relatively quick degradation of pesticides.

- No chemical byproduct formation: Ozone decomposes into oxygen, leaving no harmful residues or additional chemical pollutants. |

- Limited persistence: Ozone has a short half-life and readily decomposes. Therefore, its effective contact time with the pesticide may be limited and require continuous ozone generation for sustained degradation.

- Selectivity: While ozone can degrade many pesticides, there may be variations in reactivity, and some pesticides might require longer contact times or higher ozone concentrations.

- Off-gas management: The removal and treatment of ozone-rich off-gases can be challenging, requiring appropriate air pollution control measures. |

[48,49]

|

| Fenton process |

- Effective for complex matrices: Fenton's reaction can efficiently degrade pesticides even in complex matrices like wastewater or soil samples, where other treatments may encounter difficulties.

- Wide pH range: The Fenton reaction can operate under a wide pH range, allowing flexibility in treating different environmental conditions.

- High reactivity: Fenton's reaction generates highly reactive hydroxyl radicals, leading to rapid and effective degradation of pesticides.

- Efficient in acidic conditions (pH 3–4).

- Cost-effective compared to other AOPs

|

- Catalyst limitations: Selecting the proper iron catalyst and maintaining its activity is crucial. Iron catalysts may lose efficiency over time due to precipitation, fouling, or other factors, necessitating replacement or regeneration.

- Hydrogen peroxide requirement: The Fenton's reaction relies on the addition of hydrogen peroxide, which can be costly and pose safety concerns in large-scale applications.

- pH adjustment: Fenton's reaction often requires pH adjustment to initiate the reaction. This step adds complexity to the process and might limit its application in some scenarios. |

[50] |

| UV/H2O2

|

- UV/H2O2 is effective in degrading many pesticide classes and complex mixtures.

- It offers relatively fast reaction rates and can achieve high degradation efficiencies.

- The process can be easily controlled by adjusting the dosages of UV light and hydrogen peroxide.

- No sludge production, and H₂O₂ decomposes into water and oxygen.

|

- UV/H2O2 requires a sufficient supply of hydrogen peroxide, which can add to the operational costs.

- The presence of certain water constituents can inhibit or compete with the reaction, reducing overall efficiency.

- UV/H2O2 may not be suitable for treating large volumes of water due to the limited penetration depth of UV light. |

[51]

|

| Sonochemical degradation |

- Efficiency: Sonochemical degradation can achieve high levels of pollutant degradation due to the intense cavitation and localized hotspots created by ultrasound waves.

- Versatility: It can be applied to a wide range of pollutants, including organic compounds, pesticides, and pharmaceuticals.

- Green process: Sonochemical degradation is generally considered a green process as it operates at ambient temperatures and pressures, reducing energy consumption.

|

- Energy-intensive: Sonochemical degradation requires high power ultrasound waves, making it an energy-intensive process.

- Limited scalability: Sonochemical reactors for large-scale applications can be challenging due to issues such as uneven distribution of cavitation and scale-up complexities.

|

[52] |

| Electrochemical oxidation |

- Selectivity: Electrochemical oxidation allows for selective degradation of specific pollutants, depending on the choice of electrode material and operating conditions.

- Continuous operation: It enables continuous pollutant removal as long as a sufficient supply of electricity is available.

- Easy control: Parameters such as current density and electrode potential can be adjusted to optimize the degradation process.

- No chemical addition is needed. |

- Electrode fouling: Fouling of the electrodes can occur during the electrochemical oxidation process, reducing its efficiency.

- Limited applicability: Electrochemical oxidation may not be suitable for certain types of pollutants that are less amenable to oxidation or require specific reaction pathways.

- Cost: The cost associated with electrical power consumption, electrode maintenance, and system setup can be a limitation.

|

[5,53] |

| Advanced oxidation with peroxides |

- Versatility: Advanced oxidation with peroxides can effectively degrade a wide range of organic pollutants, including hard-to-treat compounds.

- Simplicity: Peroxide-based AOPs often have straightforward reactor designs, making them easier to implement and operate.

- No need for external energy: In certain cases, the reactions involving peroxides can be initiated by natural light rather than requiring additional energy sources.

|

- Cost: The use of peroxides in AOPs can contribute to higher operational costs due to the procurement and handling of reagents.

- By-products formation: Depending on the reaction conditions, some AOPs involving peroxides can produce undesired by-products, which need further treatment or disposal.

- pH sensitivity: The effectiveness of peroxide-based AOPs can be pH-dependent, and optimizing the reaction conditions may be necessary to achieve optimal degradation efficiency.

|

[54,55] |

5. Studies on Pesticide Treatment in Aqueous Environment Using AOPs

Table 2.

A categorization of the studies based on the type of pesticide, AOP utilized, and their key findings.

Table 2.

A categorization of the studies based on the type of pesticide, AOP utilized, and their key findings.

| Studies |

Type of pesticides |

AOP utilized |

Key findings |

| The Efficiency of Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Removal of Pesticides from Water |

Wide range of pesticides |

Ozonation, UV/H2O2, Fenton processes |

AOPs efficiently degrade pesticides, reducing their concentration below regulatory limits |

| Comparative Study of Pesticide Degradation by Ozone, UV, and Advanced Oxidation Processes |

Various pesticides |

Ozone, UV, AOPs involving peroxides (e.g., UV/H2O2) |

AOPs involving peroxides show higher degradation rates than individual ozone or UV treatment |

Application of Advanced Oxidation Processes for Removing Pesticides from Soil

|

Various pesticides |

Electro-Fenton, photocatalysis, and Sono-oxidation |

AOPs can effectively remove pesticides from soil, with some methods showing higher efficiency than others |

| Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Treatment of Pesticide containing Wastewater |

Pesticide containing wastewater

|

UV, ozone, UV/O3 process

|

AOPs effectively degrade pesticides in wastewater, highlighting their potential as a treatment option |

Process Optimization and Kinetics of Pesticide Degradation by Advanced Oxidation Processes

|

Various pesticides

|

Not specified |

The study focuses on the optimization and kinetics of pesticide degradation, providing insights into effective AOP application for pesticide treatment |

| Advanced Oxidation Processes for Degradation of Pesticides in Water |

Various pesticides |

Photocatalysis, ozonation, Fenton processes |

AOPs showed promising results for pesticide removal, with effectiveness varying based on pesticide type, initial concentration, and reaction conditions |

Pesticide Degradation by Advanced Oxidation Processes

|

Various pesticides |

Ozonation, Fenton processes, UV radiation |

AOPs effectively degraded a wide range of pesticides, reducing their concentrations to acceptable levels. Optimal degradation efficiency required careful optimization of AOP parameters |

Evaluation of AOPs for Pesticide Removal in Water: A Critical Review

|

Various pesticides |

Photocatalysis, ozonation, electrolysis |

AOPs demonstrated significant potential for pesticide treatment, but further research was needed to optimize their effectiveness. Reaction conditions and catalyst selection played a crucial role in determining AOP efficiency |

| Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Degradation of Pesticides in Aqueous Environment: A Review |

Various pesticides |

Photocatalysis, Fenton processes, ozonation |

AOPs efficiently removed pesticides, but the choice of process depended on the specific pesticide and water characteristics. Understanding degradation mechanisms and optimizing operating conditions were essential |

| Evaluation of Advanced Oxidation Processes for Mitigating the Environmental Impact of Pesticides |

Various pesticides |

Ozonation, UV/H2O2, photocatalysis |

AOPs effectively degraded pesticides, reducing their concentrations to environmentally safe levels. Reaction time, pH, initial pesticide concentration, and catalyst selection were critical factors for optimizing AOP efficiency |

6. Factors Influencing Pesticide Degradation in Aqueous Environment

The efficiency of AOPs is strongly influenced by the pH of the reaction medium, with different pesticides showing varying degradation rates at different pH levels. Optimization and adjustment of pH to suit the specific AOPs and pesticide are crucial for maximum efficiency[

9,

56]. Temperature is another critical factor affecting AOPs efficiency, as higher temperatures generally enhance reaction rates by increasing kinetic energy. However, extremes in temperature can impact the stability of catalysts or reactants, necessitating the maintenance of an appropriate temperature range[

7,

57]. Catalysts play a key role in AOPs by improving reaction rates and selectivity. The selection of suitable catalysts compatible with both the pesticide and AOPs system significantly influences overall efficiency. Furthermore, the duration of AOP treatment, initial pesticide concentration, and the presence of other substances in the matrix can all affect degradation efficiency[

56,

58]. Optimizing reaction time, considering initial pesticide concentrations, and understanding the impact of coexisting substances are essential for effective pesticide degradation processes. It is worth noting that the impact and optimal conditions of these factors can vary depending on the specific pesticide, AOPs method, and environmental conditions. Therefore, conducting preliminary investigations and optimization studies considering these factors is crucial to ensure effective pesticide treatment using AOPs.

7. The Current Challenges and Limitations Faced in the Application of AOPs for Pesticide Treatment in Aqueous Environment and Future Directions

The implementation of AOPs for pesticide remediation presents several noteworthy challenges and limitations. To begin with, the diverse chemical compositions of pesticides lead to varying degradation rates and pathways when exposed to AOPs. This variability complicates the development of effective treatment methods, requiring tailored strategies for individual pesticides, thereby augmenting the intricacy and cost of the treatment process[

59]. AOPs often rely on high-energy sources like UV radiation, ozone, or hydrogen peroxide, which can be demanding in terms of resources and expenses, especially when considering large-scale applications. The generation of potentially harmful by-products during AOP treatment raises alarming concerns regarding water quality and environmental repercussions, compelling the necessity of thorough monitoring and mitigation measures. The efficacy of AOPs is susceptible to water quality factors such as pH, temperature, and the presence of assorted organic and inorganic components, further complicating their practical implementation in real-world treatment scenarios[

60].

The application of AOPs for pesticide treatment is an evolving field that offers promising future directions. One key direction is the development of more efficient and cost-effective AOPs tailored specifically for different types of pesticides. Future research efforts may focus on enhancing the selectivity and effectiveness of AOPs to target a wider range of pesticides with improved degradation rates and pathways. There is a growing emphasis on developing integrated treatment approaches that combine AOPs with other innovative technologies to enhance pesticide removal efficiency while minimizing the formation of harmful by-products. Moreover, future directions in AOPs for pesticide treatment may involve the optimization of operating conditions, such as pH, temperature, and reactor design, to ensure consistently high treatment performance and scalability from lab-scale to field-scale applications. Continuous advancements in AOPs technology, including the use of alternative energy sources and novel catalyst materials, can further enhance the sustainability and practicality of AOPs for pesticide treatment[

61].

8. Conclusion

Advanced Oxidation Processes have proven highly effective in degrading diverse pesticides, consistently reducing their concentrations below regulatory limits. Among tested methods, UV/H₂O₂ and UV/O₃ systems demonstrated superior degradation rates compared to standalone ozone or UV treatments. Comparative studies of AOPs, such as UV, ozone, and the combined UV/O₃ approach revealed that hybrid methods outperform individual techniques, emphasizing the value of synergistic oxidation strategies. Key operational parameters, including pH, temperature, reaction duration, initial pesticide concentration, and catalyst choice, significantly influence degradation efficiency. These factors exhibit variable impacts depending on pesticide properties and reaction conditions, underscoring the need for meticulous optimization of AOP parameters to maximize performance.

While AOPs offer notable advantages, such as broad applicability, rapid kinetics, high degradation efficiency, and catalyst reusability, challenges persist. Limitations include reliance on light sources, treatment selectivity, transient effects, catalyst constraints, and operational costs. Addressing these drawbacks is critical for scalable and sustainable implementation. Future research should prioritize three areas: (1) Catalyst Innovation: Developing selective, stable catalysts through novel materials (e.g., nanostructured composites, catalytic coatings) and mechanistic studies on pesticide-catalyst interactions. (2) Parameter Optimization: Investigating how pH, oxidant concentration, irradiation intensity, and sequential/simultaneous treatment modes affect degradation pathways and by-product formation. (3) Sustainability Enhancements: Reducing energy consumption and costs while improving long-term efficacy for real-world wastewater treatment scenarios.

Credit Authorship Contribution Statement

Chun Zhao: Writing–review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis. Min Li: Writing–review & editing, Visualization, Software. Mehary Dagnew: Writing–review & editing, Writing–original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Qin Xue: Conceptualization, Writing–review & editing, Software. Jian Zhang: Writing–review & editing, Visualization. Zizeng Wang: Writing – review & editing, conceptualization. Anran Zhou: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 22076015 & 52370126) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 2024CDJQYJCYJ-001).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Khan, B.A., et al., Pesticides: Impacts on Agriculture Productivity, Environment, and Management Strategies, in Emerging Contaminants and Plants: Interactions, Adaptations and Remediation Technologies, T. Aftab, Editor. 2023, Springer International Publishing: Cham. p. 109-134.

- Pawan, K., et al., Impact of Pesticides Application on Aquatic Ecosystem and Biodiversity: A Review. Biology Bulletin, 2023. 50(6): p. 1362-1375.

- Desisa, B., A. Getahun, and D. Muleta, Advances in Biological Treatment Technologies for Some Emerging Pesticides, in Pesticides Bioremediation, S. Siddiqui, M.K. Meghvansi, and K.K. Chaudhary, Editors. 2022, Springer International Publishing: Cham. p. 259-280.

- Madsen, H.T., et al., Addition of Adsorbents to Nanofiltration Membrane to Obtain Complete Pesticide Removal. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, 2015. 226(5): p. 160. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sánchez, C., I. Robles, and L.A. Godínez, Review of recent developments in electrochemical advanced oxidation processes: application to remove dyes, pharmaceuticals, and pesticides. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 2022. 19(12): p. 12611-12678. [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.S., et al., A Review on Eco-Friendly Pesticides and Their Rising Importance in Sustainable Plant Protection Practices. International Journal of Plant & Soil Science, 2023. 35: p. 200-214. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y. and R. Zhao, Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) in Wastewater Treatment. Current Pollution Reports, 2015. 1(3): p. 167-176.

- Tijani, J.O., et al., A Review of Combined Advanced Oxidation Technologies for the Removal of Organic Pollutants from Water. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, 2014. 225(9): p. 2102. [CrossRef]

- Derbalah, A. and H. Sakugawa, Sulfate Radical-Based Advanced Oxidation Technology to Remove Pesticides From Water A Review of the Most Recent Technologies. International Journal of Environmental Research, 2024. 18(1): p. 11. [CrossRef]

- Manna, M. and S. Sen, Advanced oxidation process: a sustainable technology for treating refractory organic compounds present in industrial wastewater. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2023. 30(10): p. 25477-25505.

- Girón-Navarro, R., et al., Evaluation and comparison of advanced oxidation processes for the degradation of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D): a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2021. 28(21): p. 26325-26358. [CrossRef]

- Khan, Q., et al., Advanced oxidation/reduction processes (AO/RPs) for wastewater treatment, current challenges, and future perspectives: a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2024. 31(2): p. 1863-1889. [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R., et al., Occurrence and Sources of Pesticides to Urban Wastewater and the Environment, in Pesticides in Surface Water: Monitoring, Modeling, Risk Assessment, and Management. 2019, American Chemical Society. p. 63-88.

- Karri, R.R., G. Ravindran, and M.H. Dehghani, Chapter 1 - Wastewater—Sources, Toxicity, and Their Consequences to Human Health, in Soft Computing Techniques in Solid Waste and Wastewater Management, R.R. Karri, G. Ravindran, and M.H. Dehghani, Editors. 2021, Elsevier. p. 3-33.

- Arzu, Ö., A. Dilek, and K. Muhsin, Pesticides, Environmental Pollution, and Health, in Environmental Health Risk, L.L. Marcelo and S. Sonia, Editors. 2016, IntechOpen: Rijeka. p. Ch. 1.

- Syafrudin, M., et al. Pesticides in Drinking Water—A Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021. 18. [CrossRef]

- Jain, B., et al., Treatment of organic pollutants by homogeneous and heterogeneous Fenton reaction processes. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 2018. 16(3): p. 947-967. [CrossRef]

- Miklos, D.B., et al., Evaluation of advanced oxidation processes for water and wastewater treatment – A critical review. Water Research, 2018. 139: p. 118-131. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-h., et al., A review on Fenton process for organic wastewater treatment based on optimization perspective. Science of The Total Environment, 2019. 670: p. 110-121. [CrossRef]

- Vigil-Castillo, H.H., et al., Assessment of photo electro-Fenton and solar photo electro-Fenton processes for the efficient degradation of asulam herbicide. Chemosphere, 2023. 338: p. 139585.

- Clematis, D. and M. Panizza, Electro-Fenton, solar photoelectro-Fenton and UVA photoelectro-Fenton: Degradation of Erythrosine B dye solution. Chemosphere, 2021. 270: p. 129480.

- Brillas, E. and C.A. Martínez-Huitle, Decontamination of wastewaters containing synthetic organic dyes by electrochemical methods. An updated review. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2015. 166-167: p. 603-643. [CrossRef]

- Issaka, E., et al., Advanced catalytic ozonation for degradation of pharmaceutical pollutants―A review. Chemosphere, 2022. 289: p. 133208. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S., et al., Ozonation of organic compounds in water and wastewater: A critical review. Water Research, 2022. 213: p. 118053. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., et al., Insight into synergies between ozone and in-situ regenerated granular activated carbon particle electrodes in a three-dimensional electrochemical reactor for highly efficient nitrobenzene degradation. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2020. 394: p. 124852. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z., et al., Ozone-activated peroxymonosulfate (O3/PMS) process for the removal of model naphthenic acids compounds: Kinetics, reactivity, and contribution of oxidative species. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2023. 11(3).

- Yang, J.D., et al., Activation of ozone by peroxymonosulfate for selective degradation of 1,4-dioxane: Limited water matrices effects. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2022. 436. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., et al., Production of Sulfate Radical and Hydroxyl Radical by Reaction of Ozone with Peroxymonosulfate: A Novel Advanced Oxidation Process. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015. 49(12): p. 7330-7339. [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh, H., et al., Ozone and ozone/hydrogen peroxide treatment to remove gemfibrozil and ibuprofen from treated sewage effluent: Factors influencing bromate formation. Emerging Contaminants, 2020. 6: p. 225-234.

- Bourgin, M., et al., Effect of operational and water quality parameters on conventional ozonation and the advanced oxidation process O3/H2O2: Kinetics of micropollutant abatement, transformation product and bromate formation in a surface water. Water Research, 2017. 122: p. 234-245.

- Zhou, L., et al., Efficient degradation of phenol in aqueous solution by catalytic ozonation over MgO/AC. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 2020. 36: p. 101168. [CrossRef]

- Loeb, S.K., et al., The Technology Horizon for Photocatalytic Water Treatment: Sunrise or Sunset? Environmental Science & Technology, 2019. 53(6): p. 2937-2947.

- Carey, J.H., J. Lawrence, and H.M. Tosine, Photodechlorination of PCB's in the presence of titanium dioxide in aqueous suspensions. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 1976. 16(6): p. 697-701. [CrossRef]

- Bie, C., L. Wang, and J. Yu, Challenges for photocatalytic overall water splitting. Chem, 2022. 8(6): p. 1567-1574. [CrossRef]

- Ming, H., et al., Tailored poly-heptazine units in carbon nitride for activating peroxymonosulfate to degrade organic contaminants with visible light. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2022. 311: p. 121341.

- Wang, F., et al., Unprecedentedly efficient mineralization performance of photocatalysis-self-Fenton system towards organic pollutants over oxygen-doped porous g-C3N4 nanosheets. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2022. 312: p. 121438. [CrossRef]

- Su, R., et al., Progress on mechanism and efficacy of heterogeneous photocatalysis coupled oxidant activation as an advanced oxidation process for water decontamination. Water Research, 2024. 251: p. 121119.

- Li, Z., et al., Recent progress in defective TiO2 photocatalysts for energy and environmental applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2022. 156: p. 111980. [CrossRef]

- Guo, K., et al., Comparison of the UV/chlorine and UV/H2O2 processes in the degradation of PPCPs in simulated drinking water and wastewater: Kinetics, radical mechanism and energy requirements. Water Research, 2018. 147: p. 184-194.

- Deng, J., et al., Degradation of the antiepileptic drug carbamazepine upon different UV-based advanced oxidation processes in water. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2013. 222: p. 150-158.

- Sheikhi, S., R. Dehghanzadeh, and H. Aslani, Advanced oxidation processes for chlorpyrifos removal from aqueous solution: a systematic review. Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering, 2021. 19(1): p. 1249-1262.

- Ibrahim, K.E.A. and D. Şolpan, Removal of carbaryl pesticide in aqueous solution by UV and UV/hydrogen peroxide processes. International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry, 2022. 102(14): p. 3271-3285. [CrossRef]

- Peyton, G.R. and W.H. Glaze, Destruction of pollutants in water with ozone in combination with ultraviolet radiation. 3. Photolysis of aqueous ozone. Environmental Science & Technology, 1988. 22(7): p. 761-767. [CrossRef]

- Farkas, L., et al., Comparison of the effectiveness of UV, UV/VUV photolysis, ozonation, and ozone/UV processes for the removal of sulfonamide antibiotics. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2024. 12(1).

- He, Y., et al., Recent developments and advances in boron-doped diamond electrodes for electrochemical oxidation of organic pollutants. Separation and Purification Technology, 2019. 212: p. 802-821. [CrossRef]

- Hadei, M., et al., A comprehensive systematic review of photocatalytic degradation of pesticides using nano TiO2. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2021. 28(11): p. 13055-13071. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K., P.K. Mishra, and S.N. Upadhyay, Recent developments in photocatalytic degradation of insecticides and pesticides. 2023. 39(2): p. 225-270.

- Swami, S., et al., Evaluation of ozonation technique for pesticide residue removal and its effect on ascorbic acid, cyanidin-3-glucoside, and polyphenols in apple (Malus domesticus) fruits. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2016. 188(5): p. 301. [CrossRef]

- Garrido, I., et al., Abatement of pesticides residues in commercial farm soils by combined ozonation-solarization treatment. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2023. 195(12): p. 1406. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q., et al., Improving the efficiency of Fenton reactions and their application in the degradation of benzimidazole in wastewater. RSC Advances, 2018. 8(18): p. 9741-9748.

- da Luz, V.C., et al., Enhanced UV Direct Photolysis and UV/H2O2 for Oxidation of Triclosan and Ibuprofen in Synthetic Effluent: an Experimental Study. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, 2022. 233(4): p. 126.

- Pirsaheb, M. and N. Moradi, Sonochemical degradation of pesticides in aqueous solution: investigation on the influence of operating parameters and degradation pathway – a systematic review. RSC Advances, 2020. 10(13): p. 7396-7423.

- Paquini, L.D., et al., An overview of electrochemical advanced oxidation processes applied for the removal of azo-dyes. Brazilian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 2023. 40(3): p. 623-653. [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, M., et al., Advanced oxidation processes: Performance, advantages, and scale-up of emerging technologies. Journal of Environmental Management, 2022. 316: p. 115295.

- Gautam, P., A. Popat, and S. Lokhandwala, Advances & Trends in Advance Oxidation Processes and Their Applications, in Advanced Industrial Wastewater Treatment and Reclamation of Water: Comparative Study of Water Pollution Index during Pre-industrial, Industrial Period and Prospect of Wastewater Treatment for Water Resource Conservation, S. Roy, et al., Editors. 2022, Springer International Publishing: Cham. p. 45-69.

- Kaur, R., et al., Pesticide residues degradation strategies in soil and water: a review. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 2023. 20(3): p. 3537-3560. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Chueca, J., J. Carbajo, and P. García-Muñoz, Intensification of Photo-Assisted Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water Treatment: A Critical Review. Catalysts, 2023. 13(2): p. 401. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S., et al., Pesticide Pollution in Agricultural Soils and Sustainable Remediation Methods: a Review. Current Pollution Reports, 2018. 4(3): p. 240-250.

- Choo, K.-H., Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) and Membrane Operations, in Encyclopedia of Membranes, E. Drioli and L. Giorno, Editors. 2015, Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg. p. 1-2.

- Feijoo, S., et al., Generation of oxidative radicals by advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) in wastewater treatment: a mechanistic, environmental and economic review. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology, 2023. 22(1): p. 205-248. [CrossRef]

- Jatoi, A.S., et al., Recent trends and future challenges of pesticide removal techniques – A comprehensive review. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2021. 9(4): p. 105571. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).