1. Introduction

The evolution of nanomedicine from its inception to its application in diagnostics and therapy can be summarized in several key stages [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Foundation and Theoretical Concepts of nanotechnology were first introduced by physicist Richard Feynman in 1959. His ideas laid the groundwork for manipulating matter at the atomic level. In the early 1980s, Nadrian Seeman pioneered the field of DNA nanotechnology, proposing the use of nucleic acids to construct complex nanostructures. Technological Advancements during the 1990s in materials science and biotechnology facilitated the development of nanomaterials. Researchers began exploring the unique properties of nanoparticles, such as increased surface area and reactivity, which could be harnessed for medical applications including targeted drug delivery and their ability to improve the solubility and bioavailability of drugs. The early 2000s marked a period of significant investment and interest in nanomedicine. The U.S. government prioritized nanotechnology through initiatives like the National Nanotechnology Initiative, funded by the 21st Century Nanotechnology Research and Development Act. Researchers developed innovative nanocarriers designed to deliver therapeutic agents more effectively to target sites, such as tumors, while minimizing systemic toxicity; this was achieved by engineering nanoparticles with specific ligands or antibodies that could bind to tumor-specific receptors. This represented a critical advancement in improving the efficacy of traditional chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Concurrently, nanotechnology enabled the creation of highly sensitive diagnostic tools, including nanobiosensors and nanodevices. These tools significantly improved disease detection, monitoring, and biomarker identification, allowing for earlier and more accurate diagnosis. Nanoparticles were used as contrast agents in imaging modalities like MRI and CT scans, enhancing the sensitivity and resolution of tumor detection. For instance, dendrimers and gold nanoparticles were explored for their imaging capabilities, showing compatibility with biological systems. The term "nanotheranostics" emerged in the early 2000s as a combination of "nano," referring to nanoscale materials, and "theranostics," which is a portmanteau of "therapy" and "diagnostics." The concept signifies the integration of therapeutic and diagnostic functions into a single system, utilizing nanoparticles and nanomaterials. It represents an innovative approach that utilizes nanotechnology to simultaneously diagnose and treat diseases, particularly in the field of cancer. This dual capability of simultaneous diagnosis and therapy not only enhances the precision of medical interventions but also offers improved personalization of treatment strategies, making nanotheranostics a promising area of research and application in modern medicine. As nanomedicine technologies matured, a variety of nanopharmaceuticals and diagnostic products entered clinical trials. Some of these products have obtained regulatory approvals and are now commercially available, demonstrating real-world applications in medical settings. Through these stages, nanomedicine has transitioned from theoretical concepts and laboratory research to practical applications in diagnostics and therapy, showcasing its potential to revolutionize healthcare. Overall, the journey from early research to the current applications of nanomedicine in cancer diagnosis and therapy demonstrates a continuous evolution from non-targeting to targeting, from simple materials to mixed systems, and from single to combined technologies driven by interdisciplinary collaboration and technological advancements, with a focus on improving patient outcomes and precision medicine.

2. Contribution of Radioisotopic Imaging Techniques to Nanomedicine

Imaging techniques, particularly radioisotopic methods, play a crucial role in the development of nanomedicine and nanotheranostics and their contributions are multifaceted since they are instrumental during preclinical and clinical trials to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new nanomedicine therapies. They help in determining optimal dosages, understanding pharmacokinetics, and monitoring tumor responses [

36,

37,

38,

39].

By tagging nanoparticles with radioisotopes, researchers can track their distribution and localization in vivo. Radioisotopic imaging techniques, such as Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT), allow for non-invasive real-time monitoring of agents within the body wich is essential for assessing the efficacy of nanotherapeutics in targeting specific tissues or tumors thus enabling adjustments in therapy based on the observed effectiveness [

40,

41,

42]. This capability is crucial for personalized medicine, where treatment protocols can be dynamically adapted to individual patient responses. Understand the biodistribution, metabolism and excretion of nanomedicines helps optimize their design and functionality, ensuring that the agents are delivered precisely where needed, thereby minimizing systemic side effects. In the context of nanotheranostics, radioisotopic imaging allows for the evaluation of how effectively nanoparticles target tumor sites. By tracking the accumulation of radiolabeled nanoparticles in tumors, clinicians can assess treatment responses and adjust therapeutic strategies accordingly. On the other hand, certain nanotheranostic platforms utilize radioisotopes not only for imaging but also for therapeutic purposes. This approach involves delivering radiation directly to tumor cells while monitoring the treatment's impact through imaging techniques, combining therapy and diagnostics effectively [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. The application of radioisotopic imaging in nanomedicine is prominent in oncology, where it aids in the diagnosis and treatment of various cancers. Furthermore, these imaging techniques are also being explored in other fields, such as cardiovascular disease, neurology, and infection management [

50]. They facilitate understanding disease mechanisms and evaluating new treatment approaches. In summary, radioisotopic imaging techniques significantly contribute to the advancement of nanomedicine and nanotheranostics by enhancing diagnostic precision, enabling real-time therapeutic monitoring, optimizing targeted drug delivery, and facilitating innovative treatment strategies across multiple medical disciplines.

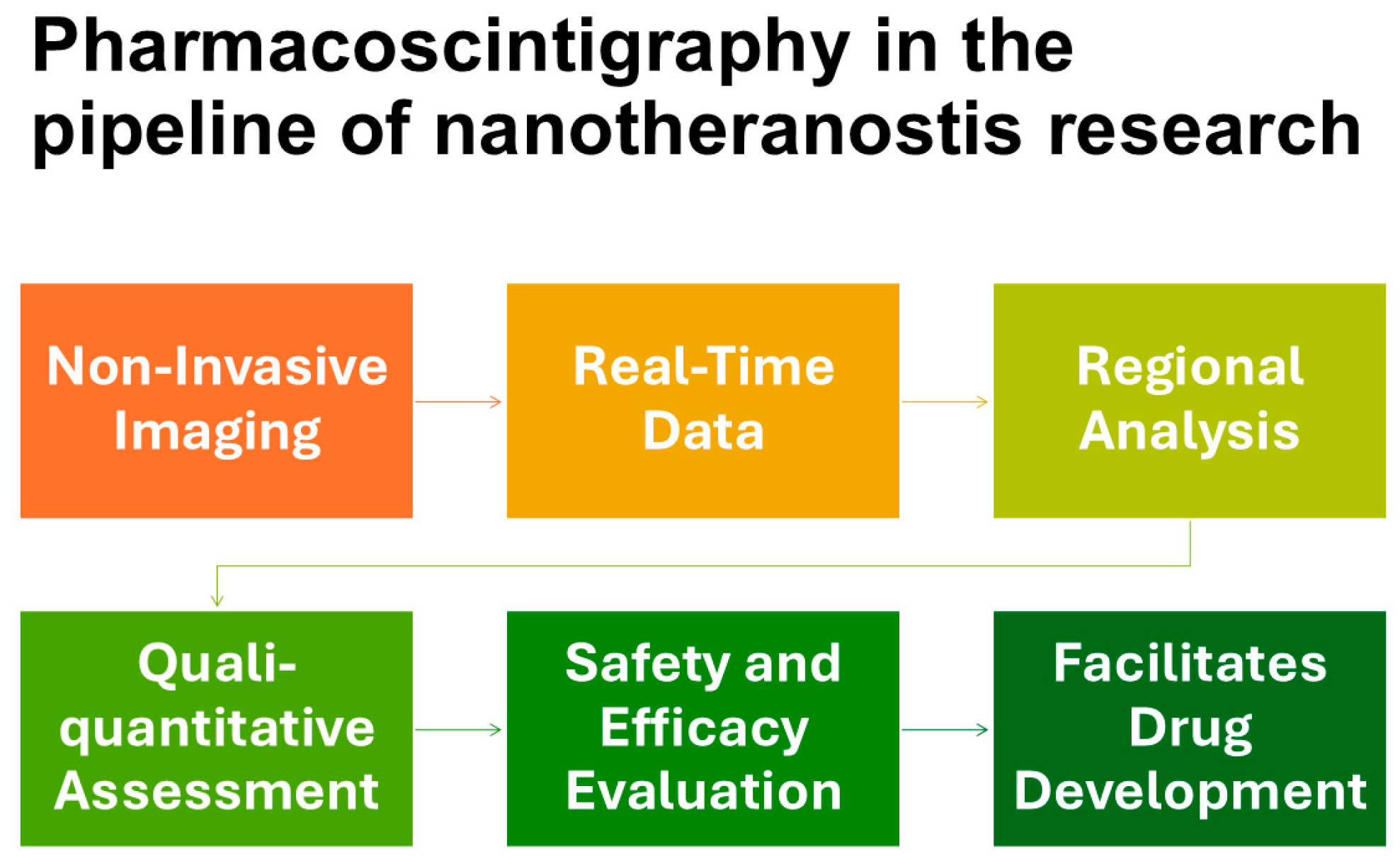

Pharmacoscintigraphy (

Figure 1) is a term that encompasses radioisotopic imaging techniques, including planar gamma imaging, SPECT, and PET, to denote their specific role and application in pharmacological research. In this article, we will use this term to broadly refer to this specialized field, highlighting its role in the investigation and development of nanotheranostics [

51,

52,

53].

As personalized medicine gains prominence, pharmacoscintigraphy contributes to the development of tailored therapies by elucidating individual patient responses to different formulations. The integration of radionuclide tagging into pharmacoscintigraphy thus boosts nanotheranostics research by ensuring efficacy, safety, and compliance with regulatory standards, ultimately leading to improved therapeutic outcomes.

3. Pharmacoscintigraphy in the Development of Nanotheranostics

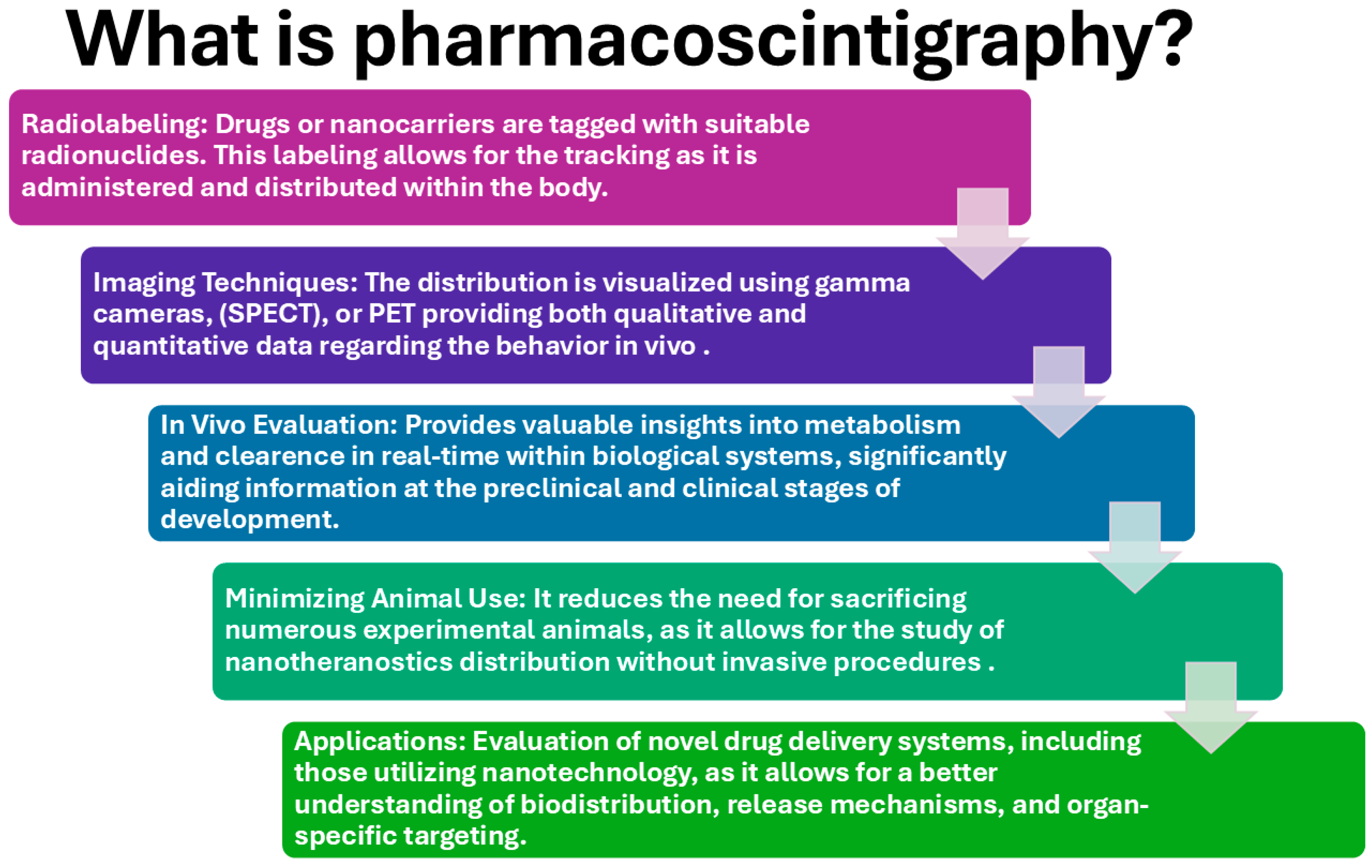

The principles of scintigraphy involve the use of radioactive materials to visualize biological processes in vivo (

Figure 2). These substances are administered to a subject and then localize in specific tissues based on their chemical properties and physiological interactions. When the radioactive isotope decays, it emits radiation. These gamma rays are what scintigraphy detects. Scintigraphy involves specialized detection systems which are designed to capture the emitted radiation from the radioactive material within a living body. The light produced by the interaction of radiation with the scintillation crystals is then converted into electrical signals, which are processed to create an image. These images reflect the distribution and concentration of the radioactive material, indicating how organs function rather than merely their anatomical structure. Unlike conventional imaging techniques that primarily focus on anatomical details (such as X-rays or MRI), scintigraphy provides functional imaging. It allows researchers and clinicians to assess physiological functions such as blood flow, metabolic activity, and organ perfusion. Scintigraphy can produce both two-dimensional and three-dimensional images. This multidimensional capability allows for more detailed analysis of organ function and pathology. Advanced data processing techniques allow quantitative analysis of the images, enabling researchers and clinicians to measure various parameters related to drug biodistribution and PK, such as uptake rate and elimination half-life providing significant insights into physiological processes [

54]

.

3.1. Imaging Modalities

Table 1 shows the comparative analysis of imaging techniques summarizing different features of each modality [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58].

3.1.1. Gamma Scintigraphy

This is a fundamental technique in nuclear medicine that relies on gamma-emitting radionuclides to provide real-time imaging of pharmaceutical formulations. The principle of gamma scintigraphy is based on the emission of gamma photons from radiotracers, typically labeled with Technetium-99m (99mTc), Iodine-123 (123I), or Indium-111 (111In). These emissions are captured to construct two-dimensional images of drug distribution, allowing for precise tracking of drug transit and retention in different organs. This technique has been widely used for assessing gastrointestinal transit, pulmonary drug deposition, and nanoparticle biodistribution [

54,

56].

3.1.2. Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT)

SPECT imaging extends gamma scintigraphy by enabling three-dimensional visualization of radiotracer distribution. This is achieved by acquiring multiple planar images from different angles, which are then reconstructed into a volumetric dataset. The ability of SPECT to provide high-resolution spatial localization makes it a valuable tool in nanomedicines research. One of the primary applications of SPECT is imaging organ-specific drug accumulation and clearance. This is particularly useful in evaluating the targeting efficiency of nanoparticles designed for tumor therapy or inflammation sites. Additionally, SPECT has been employed to monitor therapeutic responses in nanotheranostics, providing critical data for optimizing drug formulations [

54,

55,

56,

59].

3.1.3. Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

PET is a highly sensitive imaging modality that provides quantitative molecular insights into nanomedicines interactions. Unlike SPECT, which detects single-photon emissions, PET relies on positron-emitting radiotracers such as Fluorine-18 (18F), Zirconium-89 (89Zr), and Copper-64 (64Cu). The annihilation of emitted positrons with electrons results in the production of gamma photons, which are detected to generate high-resolution images. The application of PET in nanomedicine has been particularly promising in studying tumor targeting efficiency. The technique allows for real-time assessment of receptor-mediated nanoparticle uptake and quantification of drug metabolism and clearance pathways. Furthermore, PET's high sensitivity enables the detection of low concentrations of radiolabeled nanomedicines, making it an invaluable tool in early-phase drug development [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59].

3.2. Radiolabeling Techniques

Radiolabeling methods for nanoparticles have been extensively reported and reviewed by numerous authors in recent years. These studies have contributed to the development of various strategies for incorporating radionuclides into nanoplatforms, ensuring their stability, biocompatibility, and applicability for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Given the breadth of research in this field, the present section provides a concise summary of the most relevant and widely employed radiolabeling techniques. Readers seeking a more comprehensive understanding of these methodologies, including detailed protocols for reproducibility in their own investigations, are encouraged to refer to the cited references in this section [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69].

There are several methods available for radiolabeling nanotheranostics as well as many dosage forms, primarily used in gamma scintigraphy.

Table 2 summarizes the radioisotopes most commonly used for radiolabeling and their physical properties.

Each method has its advantages and limitations, with the choice depending on several factors, including the type of nanocarrier, the physicochemical properties of the radionuclide, and the intended clinical application. The selected method should not compromise the performance of the dosage form while ensuring that the radioactive labeling is effective for imaging purposes. These methods include direct radiolabeling, chelator-based labeling, covalent binding, encapsulation, and neutron activation, each offering distinct advantages and limitations.

3.2.1

Direct radiolabeling involves incorporating the radionuclide directly into the nanocarrier without requiring external chelators or complexation agents. This process can occur through chemisorption, isotopic exchange, or surface interaction, depending on the material composition. For instance, metallic nanoparticles, such as gold or iron oxide can adsorb 99mTc due to their high affinity for metal ions [

70,

71]. Additionally, sulfhydryl-containing nanoparticles can bind reduced 99mTc to form stable complexes [

72,

73,

74,

75]. However, while direct radiolabeling is simple and fast, it may suffer from lower labeling efficiency and in vivo instability, which could lead to radionuclide dissociation.

3.2.2

Chelator-based radiolabeling remains one of the most widely used strategies due to its high stability and versatility [

76,

77,

78,

79,

80]. In this approach, a bifunctional chelator (

Table 3) is conjugated to the nanocarrier, forming a stable complex with radiometals such as gallium-68 (68Ga), copper-64 (64Cu), or lutetium-177 (177Lu). Chelators like DTPA (Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid) and DOTA (1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraaceticacid) provide strong coordination with radiometals, preventing their premature release. This method is particularly useful for polymeric micelles and liposomal formulations, where DOTA-functionalized systems allow stable binding of therapeutic radionuclides such as 177Lu, supporting their dual role in imaging and therapy.

3.2.3 Covalent radiolabeling is another approach that provides strong radionuclide attachment through chemical reactions, improving in vivo stability. Iodination methods, such as electrophilic substitution, are commonly employed for labeling proteins, peptides, and polymeric nanocarriers with iodine-125 (125I) or iodine-131 (131I). Additionally, click chemistry-based strategies, such as copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), facilitate the radiolabeling of nanoparticles with isotopes like 64Cu or 18F, ensuring site-specific conjugation without altering the physicochemical properties of the nanoparticles.

3.2.4 Encapsulation or incorporation of radionuclides within the nanoparticle matrix represents another effective labeling technique, particularly for systems with a high capacity for drug loading. Liposomes, micelles, and mesoporous silica nanoparticles can incorporate hydrophilic radionuclides, such as 111In or 99mTc-pertechnetate, into their aqueous core. Similarly, some inorganic nanocarriers, including cerium oxide-based systems, allow the incorporation of radiometals like 68Ga or 177Lu into their structure. The primary challenge of encapsulation-based radiolabeling is the potential leakage of the radionuclide, requiring additional stabilization strategies to prevent premature release.

3.2.5

Neutron activation is an alternative radiolabeling technique that involves irradiating preformed nanoparticles with thermal neutrons, converting a stable isotope within the nanostructure into a radioactive one. This method is particularly useful for nanocarriers containing elements such as holmium-165 (165Ho), which, upon neutron activation, transforms into the beta-emitting holmium-166 (166Ho) [

81]. The advantage of neutron activation is that it does not require chemical modification or surface functionalization, preserving the integrity of the nanosystem. However, this technique requires access to nuclear reactors, limiting its widespread applicability in routine radiolabeling procedures.

Advances in radiochemistry and nanotechnology continue to refine these methods, offering new opportunities for developing multimodal imaging probes and radiotherapeutics.

Table 4 summarizes the key characteristics of different radiolabeling methods.

The choice of radioisotopes significantly affects the study outcomes in radiolabeled absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) studies due to several factors [

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98]. The specific radioisotope selected can influence the stability and behavior of the radiolabeled compound because of radiolitic processes or interfering with how the compound interacts within biological systems by an active site specially if the radioactive element is not typically present in the drug molecules or the nanocarrier. The location of the radiolabel within the molecule may influence the drug’s metabolism and distribution patterns. Labeling at a position that is prone to metabolic degradation can lead to challenges in interpreting distribution data. The purity of the radiolabeled compound and its specific activity (radioactivity per unit of mass) are critical parameters. High specific activity is preferred as it allows for better detection and quantification without significantly altering the PK of the drug. The half-life of the radioisotope affects the duration of the study and the type of analysis that can be performed. For instance, isotopes with shorter half-lives may require rapid in vivo studies, complicating the design. Overall, the careful selection of radioisotopes is essential to obtain reliable and interpretable results from ADME studies, facilitating accurate assessments of a drug's behavior in vivo. Examples of applications of radiolabeling strategies are summarized in

Table 5.

3.3. Choosing An Imaging Modality

The choice of imaging modality for pharmacoscintigraphy is influenced by several factors [

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105], including the type of study, radionuclide characteristics, specificity needs, availability of equipment and expertise, ethical considerations, and regulatory compliance. The specific goals of the investigation, such as biodistribution, PK, or pharmacodynamics of drug formulation, dictate the imaging modality. For example, SPECT is often chosen for three-dimensional imaging of internal structures, while planar gamma cameras may be sufficient for simpler studies. The choice of radionuclide, such as gamma-emitting isotopes like 99mTc or 111In, plays a crucial role, as different radionuclides have distinct energy levels and half-lives. Positron emitters like Carbon-11 or Fluorine-18 require specialized equipment like PET scanners due to their higher photon energies and shorter half-lives. The level of anatomical detail required for the study also influences modality selection. While SPECT provides higher spatial resolution and can generate cross-sectional images, planar imaging may not deliver the necessary detail for certain applications, especially when complex structures are involved. The availability of equipment and expertise is another determining factor, as some techniques, like PET, are more expensive and require specialized training. Ethical considerations regarding radiation exposure levels and safety limits, as recommended by nuclear regulatory authorities on radiological protection, are of utmost importance when dealing with human subjects. The chosen modality should balance the need for quality imaging with participant safety. Regulatory compliance, including adherence to Good Manufacturing Practices, also impacts the choice of imaging modality and the overall study design. By considering these factors, researchers can select the most appropriate imaging modality for their specific needs in imaging scintigraphy [

105].

3.4. Limitations of Imaging Techniques

These techniques do not provide detailed anatomical insights, making it challenging to visualize the exact location of the radiolabeled agent unless it outlines clearly identifiable organs. Hybrid imaging techniques overcome this limitation. Not all drugs or compounds or nanosystems can be effectively labeled with radioisotopes, which limits the applicability of the technique. The equipment is often expensive, especially if hybrid modalities are used, and its operation requires skilled personnel, which can be a barrier to widespread use. While the radiation doses used are low and generally considered safe, the need to handle radioactive materials still requires adherence to strict safety protocols. These limitations indicate that while radioisotopic imaging techniques are a valuable tool in drug evaluation, there are specific challenges that researchers must navigate to effectively utilize this technique [

101,

102,

103,

104,

105].

4. Applications in Nanomedicines Research

4.1. Objectives

The main objectives of conducting pharmacoscintigraphic ADME studies are as follows [

106]:

Determine Mass Balance: To compare the amount of administered radioactivity to the amount recovered in excreta.

Routes of Elimination: To identify routes of elimination and evaluate the extent of absorption.

Metabolite Identification: To identify circulatory and excretory metabolites.

Clearance Mechanisms: To determine the mechanisms of clearance (renal, biliary, metabolic).

Distribution Characterization: To characterize the distribution of the compound within tissues and organs.

Exposure Determination: To ascertain the exposure levels of the parent compound and its metabolites.

Validation of Animal Models: To help validate the animal species used for toxicological testing.

Pharmacological/Toxicological Contribution: To explore whether metabolites contribute to the pharmacological or toxicological effects of the drug.

4.2. Why Pharmacoscintigraphic ADME Studies Are Recommended

Nanomedicines and drug delivery systems often exhibit unique PK profiles compared to conventional drugs due to their small size, surface properties, and ability to interact with biological barriers. Radiolabeled studies allow researchers to characterize the ADME properties of these nanomaterials accurately. Understanding how nanomedicines distribute in the body is critical, especially because they may accumulate in specific tissues (e.g., tumors) due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. Radiolabeled compounds can be tracked non-invasively to delineate their distribution across different organs and tissues over time. The metabolism of nanomedicines may differ significantly from that of traditional drugs. Investigating how a nanocarrier is metabolized or cleared can inform the design of drug delivery systems and help predict potential toxicological concerns. Regulatory authorities may require comprehensive ADME data for the registration of nanomedicines. Radiolabeled studies provide essential data needed to demonstrate safety and efficacy through systematic evaluation of how these formulations behave in biological systems [

102,

103,

106,

107,

108].

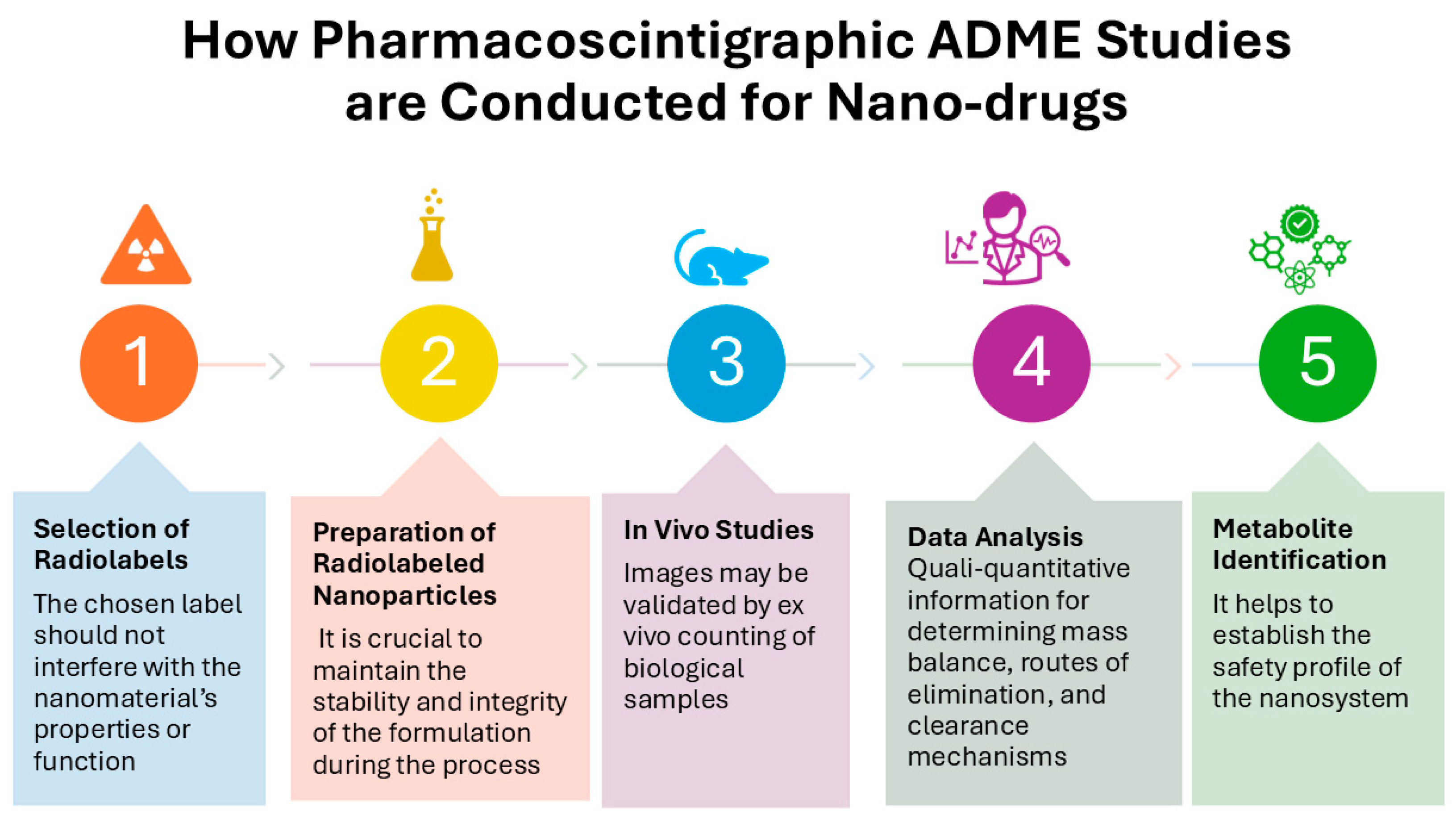

4.3. How Pharmacoscintigraphic ADME Studies Are Conducted for Nanomedicines

The first step is the selection of radiolabels. Assess the appropriate radiolabel based on the chemical structure and application. The chosen label should not interfere with the nanomaterial’s properties or function. Then, preparation of radiolabeled nanoparticles by synthetasing the nanomedicine with the appropriate radiolabeling strategy may involve encapsulating the radioisotope within the nanoparticle or attaching it to the surface. It is crucial to maintain the stability and integrity of the formulation during this process and quality control are part of the evaluation before using it in the imaging studies. Once the nanosystem is ready, it is administered to suitable animal model and in vivo studies are conducted by acquiring functional images and may be also collecting biological samples (e.g., blood, urine, feces, organs) over time to complement or validate the PK and biodistribution results. Quantitative analysis of images (and samples) to assess the extent of radioactivity associated with the administered nanosystem is crucial for determining mass balance, routes of elimination, and clearance mechanisms. Additionally, metabolite identification, is possible, helps understanding the biotransformation pathways to establish the safety profile of the nanomedicine [

102,

103,

106,

107,

108]. In summary, radiolabeled ADME studies are invaluable for the development and regulatory evaluation of nanomedicines and drug delivery systems, as well as of nanotheranostics, assisting in the understanding of their unique PK profiles and safety assessments (

Figure 3).

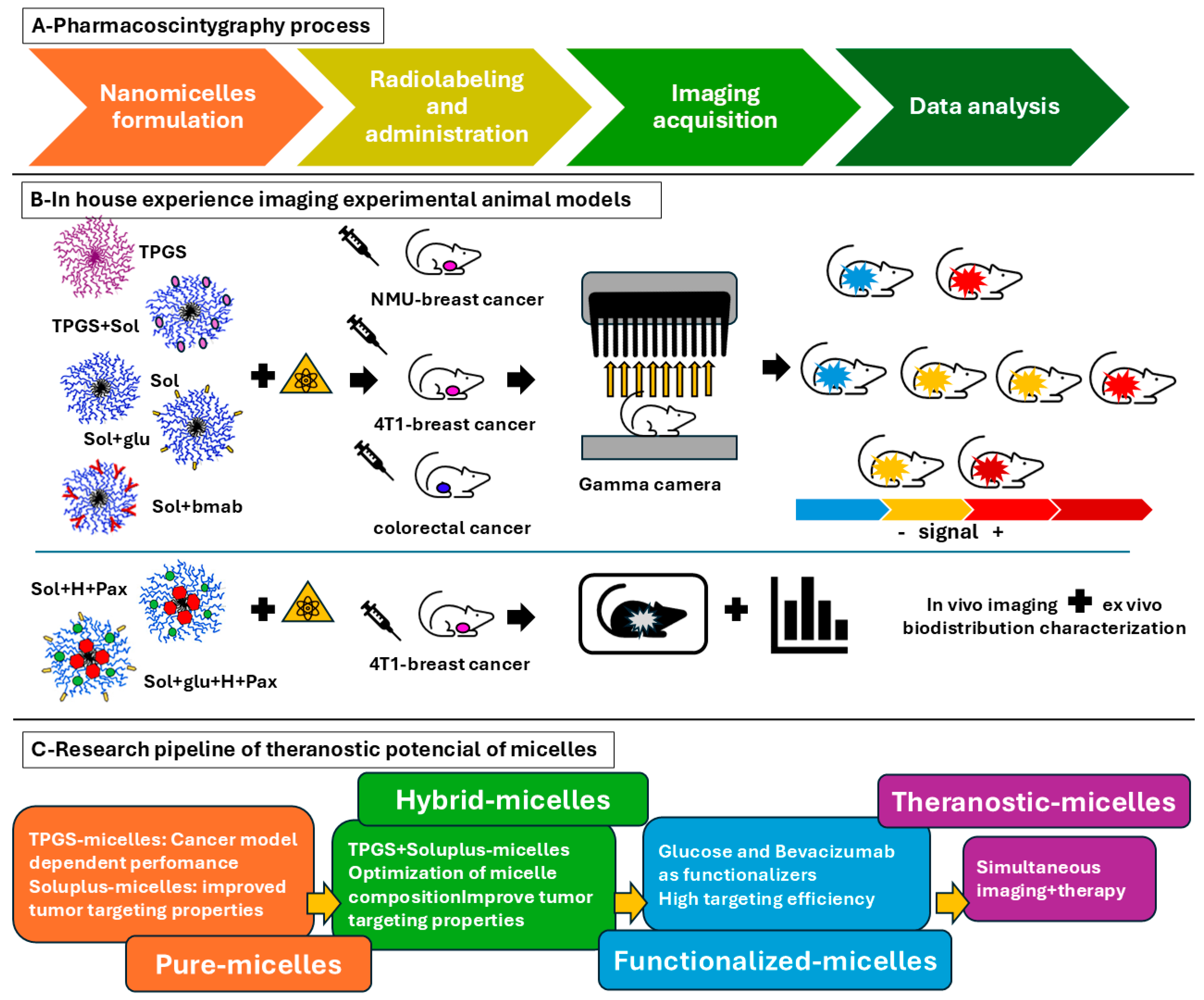

5. In-House Experience: Nanotheranostics in Cancer

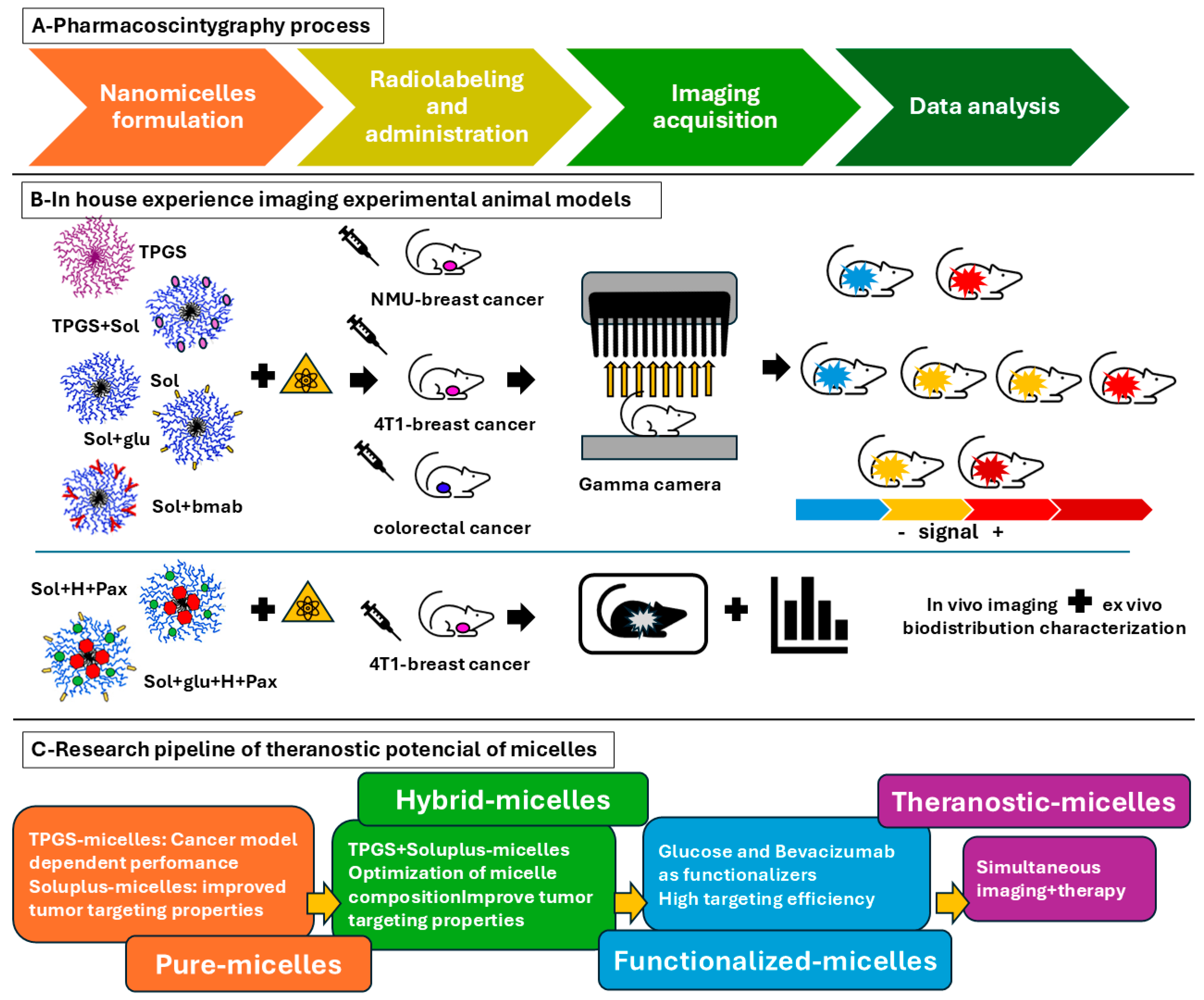

The advancement of nanotheranostics has needed the development of sophisticated imaging techniques to evaluate their biodistribution, PK, and therapeutic efficacy. Among these, radionuclide imaging has played a pivotal role, providing non-invasive, real-time insights into the behavior of nanosystems in vivo. The research conducted in our institution has significantly contributed to this field by employing 99mTc radiolabeling to study various polymeric nanomicelles (

Figure 4). The investigations have provided crucial data on micelle performance, functionalization strategies, and the potential for targeted imaging and therapy in oncology [

109,

110,

111,

112,

113,

114].

The work has primarily focused on TPGS-based nanomicelles, Soluplus® micelles, and hybrid micelles composed of TPGS and Soluplus®, all of which exhibit excellent solubilizing properties and biocompatibility. The use of 99mTc radiolabeling enabled precise tracking of these nanosystems, allowing us to evaluate their stability, tumor uptake, and clearance rates. Beyond their imaging potential, these nanomicelles have been investigated as theranostic platforms as well, capable of serving as both drug delivery vehicles and imaging agents.

TPGS (D-α-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol succinate) is a nonionic surfactant with self-assembling properties that form stable nanomicelles. The foundational studies focused on the radiolabeling efficiency, stability, and PK of 99mTc-TPGS micelles in healthy Wistar rats. Planar gamma imaging was performed at multiple time points to evaluate micelle stability in blood circulation, accumulation in organs of clearance (liver, kidneys, and intestines) and excretion pathways (renal and hepatobiliary clearance). The results demonstrated that 99mTc-TPGS micelles could be successfully radiolabeled with 99mTc, retaining their physicochemical properties, remained stable in circulation, exhibited controlled hepatic and renal clearance, and maintained a favorable PK profile, supporting their potential for in vivo imaging applications [

110]. TPGS micelles were later tested in a chemically induced breast cancer model using

N-nitroso-N-methylurea (NMU) in Sprague-Dawley rats and compared against 99mTc-sestamibi. Imaging analysis revealed that 99mTc-TPGS micelles achieved higher tumor uptake and contrast than 99mTc-sestamibi, exhibiting superior imaging performance because of their higher tumor-to-background ratios demonstrating their potential as a more efficient diagnostic agent [

111,

112]. However, in the 4T1 murine breast cancer model, the same formulation exhibited low tumor accumulation, suggesting that passive targeting via the EPR effect was insufficient. To overcome this limitation, hybrid micelles composed of TPGS and Soluplus® were tested, demonstrating improved tumor uptake and superior imaging contrast, likely due to optimized micelle stability and biodistribution. Then, Soluplus® micelles and hybrid Soluplus® + TPGS micelles were further evaluated for tumor accumulation and imaging efficiency. These formulations demonstrated superior imaging performance in the 4T1 breast cancer model, achieving higher tumor-to-background ratios compared to TPGS micelles alone. Planar gamma imaging was used to monitor biodistribution and retention over time, confirming that these formulations offered better tumor retention. To improve active targeting, Soluplus® micelles were functionalized with glucose, aiming to exploit the overexpression of glucose transporters (GLUT1) in breast cancer cells. Imaging studies showed that glucose-functionalized micelles exhibited significantly increased tumor uptake, confirming that GLUT1-mediated targeting enhanced retention and imaging contrast. Beyond their imaging applications, polymeric micelles have demonstrated the potential for drug delivery, making them ideal candidates for theranostic applications [

113]. One particularly study investigated the co-loading of histamine and paclitaxel in nanomicelles, demonstrating the capacity of these systems to improve chemotherapy while being tracked via radionuclide imaging. The theranostic potential of polymeric micelles was further demonstrated, when Soluplus® micelles alone and functionalized with glucose were co-loaded with paclitaxel and histamine aimed to improve therapeutic outcomes through different mechanisms. These micelles demonstrated significantly greater antitumor efficacy compared to the other formulations as this experimental group showed a more pronounced reduction in triple negative breast cancer cell viability and increased apoptosis compared to micelles containing paclitaxel alone or histamine alone. The formulations exhibited differing effects on neovascularization, with histamine-loaded micelles (both with and without paclitaxel) significantly reducing new blood vessel formation, which is crucial for tumor growth, while the empty micelles did not show this effect. The ability of these micelles to carry therapeutic payloads while being imaged in vivo suggests their future role as integrated diagnostic and therapeutic platforms [

114].

In a separate study focused on colorectal cancer, Soluplus® micelles were functionalized with bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), to enhance active targeting in a colorectal cancer xenograft model [

109]. Planar gamma imaging was used to track the biodistribution of radiolabeled micelles in tumor-bearing mice, demonstrating that bevacizumab-functionalized micelles showed higher tumor accumulation and prolonged retention compared to non-functionalized micelles demonstrating a synergistic effect between passive EPR and active targeting mechanisms. These findings support the role of VEGF-targeting micelles in improving nanoparticle-mediated tumor imaging and therapy guidance [

109].

Table 6 summarizes the performance of the different radiolabeled nanomicelles in the studies carried out in house.

6. Discussion and Future Perspectives

The integration of pharmacoscintigraphy into nanomedicine research has significantly improved our ability to assess nanotheranostics behavior in vivo, providing critical data on biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, and therapeutic efficacy. Pharmacoscintigraphy, encompassing gamma scintigraphy, SPECT, and PET, has demonstrated its value in evaluating nanotheranostics, enabling the precise tracking of radiolabeled nanocarriers in both preclinical and clinical studies. This capability has facilitated the optimization of nanoformulations, ensuring their stability, targeted delivery, and therapeutic potential. One of the major advantages of radionuclide imaging is its ability to provide real-time, non-invasive monitoring of drug-loaded nanocarriers. This feature is particularly relevant in oncology, where nanotheranostic formulations must efficiently reach and accumulate in tumor tissues while minimizing systemic toxicity. By allowing dynamic visualization of drug distribution, these imaging techniques contribute to the rational design of nanomedicines, refining their pharmacological profiles and improving therapeutic outcomes. Future advancements in imaging technology both in the preclinical and clinical settings hold promise for further enhancing the precision of nanotheranostics tracking. Multimodal approaches that integrate the high sensitivity of PET with the superior anatomical resolution of MRI or CT, provide a more comprehensive understanding of nanotheranostics behavior at both molecular and structural levels. Additionally, the emergence of longer-lived positron-emitting radionuclides, such as Zirconium-89 (89Zr), offers extended imaging windows, which are particularly beneficial for evaluating slow-releasing nanotheranostic platforms. Beyond their application in biodistribution studies, pharmacoscintigraphy is proving instrumental in assessing the therapeutic efficacy of nanotheranostics. Imaging studies allow for the quantification of tumor response following treatment, revealing changes in tumor volume, perfusion, and metabolic activity. This capability is critical in evaluating whether nanotheranostics achieve sufficient therapeutic concentration at the target site. Moreover, imaging-based tracking of biomarkers of disease progression, such as hypoxia levels or angiogenesis, can provide deeper mechanistic insights into nanotheranostics action, guiding further refinements in formulation design. Another crucial contribution of pharmacoscintigraphy to nanomedicine research is its role in regulatory approval processes. Regulatory agencies, increasingly require in vivo imaging data to support the approval of nanomedicines, particularly those involving novel drug delivery systems. Imaging-derived pharmacokinetic and biodistribution data provide essential safety and efficacy assessments, expediting the transition of nanotheranostics from preclinical studies to human trials. Furthermore, pharmacoscintigraphy allows for the early identification of off-target effects, helping to refine dosing regimens and reduce potential adverse reactions before first-in-human administration. The impact of pharmacoscintigraphy is not limited to preclinical and regulatory applications; it also plays a crucial role in the development of personalized medicine strategies. By tailoring therapies based on patient-specific imaging data, clinicians can optimize treatment regimens, adjusting dosing and formulation strategies to maximize efficacy while minimizing toxicity. The ability to track individual patient responses in real time could lead to a more adaptive, precision-based approach to nanotheranostic applications, particularly in oncology and other complex disease settings. Lastly, pharmacoscintigraphy provides valuable information on the long-term stability and integrity of nanocarriers. Given that many nanoformulations rely on the controlled release of therapeutic agents, imaging studies can reveal how these formulations behave under physiological conditions over extended periods. This aspect is particularly relevant for theranostic applications, where both diagnostic imaging and therapeutic delivery must be tightly coordinated to achieve optimal patient outcomes.

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, imaging techniques play a vital role in the research and development of nanotheranostics providing real-time, non-invasive insights into their biodistribution and pharmacokinetics, therapeutic efficacy, formulation stability, and mechanisms of action, while also facilitating the transition to clinical applications. As technological advancements continue to refine imaging modalities and regulatory frameworks increasingly recognize their value, pharmacoscintigraphy will remain an indispensable tool for the successful translation of nanomedicines from preclinical research to clinical applications, contributing to more effective and personalized treatment strategies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

ADME Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion

CT Computed Tomography

DNA Desoxyribonucleic-acid

EPR Enhanced Permeability and Retention

GLUT-1 Glucose Transporter 1

GMP Good Manufacturing Practices

MRI Magnetic Resonance Imaging

NMU: N-nitroso-N-methylurea

PET Positron Emission Tomography

PK Pharmacokinetic

Sol: Soluplus®

Sol+glu: Soluplus® micelle functionalized with glucose

Sol+bmab: Soluplus® micelle functionalizaed with bevacizumab

Sol+H+Pax: Soluplus® micelle loaded with histamine and paclitaxel

Sol+glu+H+Pax: : Soluplus® micelle functionalized with glucose loaded with histamine and paclitaxel

SPECT Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography

TPGS: D-α-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol succinate

TPGS+sol: hybrid micelle with Soluplus®+TPGS

US: United States

VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

References

- Bayda, S.; Adeel, M.; Tuccinardi, T.; Cordani, M.,; Rizzolio, F. The History of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology: From Chemical–Physical Applications to Nanomedicine. Molecules 2020, 25, 112. [CrossRef]

- Beg, S.; Kawish, S. M.; Panda, S. K.; Tarique, M.; Malik, A.; Afaq, S.; Al-Samghan, A. S.; Jawed, Iqbal J.; Alam, K.; Rahman, M. Nanomedicinal strategies as efficient therapeutic interventions for delivery of cancer vaccines. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 69, 43–51. [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Yang, X.; An, N.; Yang, F.; Sun, J.; Xing, Y.; Shang, H. Advances in the application of nanotechnology in reducing cardiotoxicity induced by cancer chemotherapy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86, 929–942. [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y.; Ju R. Recent progress in nanomedicine for enhanced cancer chemotherapy. Theranostics 2021, 11, 6370–6392. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Pu, Y.; Shi, J. Nanomedicine-enabled chemotherapy-based synergetic cancer treatments. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 4. [CrossRef]

- Nevins, S.; McLoughlin, C. D.; Oliveros, A.; Stein, J. B.; Rashid, M. A.; Hou, Y.; Jang, M. H.; Lee, K. B. Nanotechnology approaches for prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity, neuropathy, and cardiomyopathy in breast and ovarian cancer survivors. Small 2024, 14, e2300744. [CrossRef]

- Bagherifar, R.; Kiaie, S. H.; Hatami, Z.; Armin Ahmadi, Sadeghnejad, A.; Baradaran, B.; Jafari, R.; Javadzadeh, Y. Nanoparticle-mediated synergistic chemoimmunotherapy for tailoring cancer therapy: recent advances and perspectives. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 110. [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Yang, C.; Wu, Y.; Ru, G.; He, X.; Tong, X.; Wang, S. Nanocarriers surface engineered with cell membranes for cancer targeted chemotherapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 45. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T. P.; Moreira, J. A.; Monteiro, F. J.; Laranjeira, M. S. Nanomaterials in cancer: reviewing the combination of hyperthermia and triggered chemotherapy. J. Control. Release 2022, 347, 89–103. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Rashid, S.; Chaudhary, A. A.; Alawam, A. S.; Alghonaim, M. I.; Raza, S. S.; Khan, R. Nanomedicine as potential cancer therapy via targeting dysregulated transcription factors. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2023, 89, 38–60. [CrossRef]

- Kuderer, N. M.; Desai, A.; Lustberg, M. B.; Lyman, G. H. Mitigating acute chemotherapy-associated adverse events in patients with cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 681–697. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Rosenkrans, Z. T.; Ni, D.; Lin, J.;, Huang, P.; Cai, W. Nanomedicines for renal management: from imaging to treatment. Accounts Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 1869–1880. [CrossRef]

- Kopecek, J.; Yang, J. Polymer nanomedicines. Adv. Drug Deliver. Rev. 2020, 156, 40–64. [CrossRef]

- Lammers, T.; Sofias, A. M.; van der Meel, R.; Schiffelers, R.; Storm, G.; Tacke, F.; Koschmieder, S.; Brümmendorf, T. H.; Kiessling, F.; Metselaar, J. M. Dexamethasone nanomedicines for COVID-19. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 622–624. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. Y. S.; Rutka, J. T.; Chan, W. C. W. Nanomedicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2434–2443. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Kantoff, P. W.; Wooster, R.; Farokhzad, O. C. Cancer nanomedicine: progress, challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017 17, 20–37. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S. N.; Chen, X.; Dobrovolskaia, M. A.; Lammers, T. Cancer nanomedicine. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 550–556. [CrossRef]

- Kemp, J. A.; Kwon, Y. J. Cancer nanotechnology: current status and perspectives. Nano Converg 2021, 8, 34. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M. Cancer nanotechnology: opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 2005, 161–171. [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, J.; Ferrari, M. Clinical cancer nanomedicine. Nano Today 2019, 25, 85–98. [CrossRef]

- van der Meel, R.; Sulheim, E.; Shi, Y.; Kiessling, F.; Mulder, W. J. M.; Lammers, T. Smart cancer nanomedicine. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 1007–1017. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Gao, D.; Zhao, J.; Yang, G.; Guo, M.; Wang, Y.; Ren, X.; Kim, . JS.; Jin, L.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, X. Thermal immuno-nanomedicine in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 116-134. [CrossRef]

- Mansoori, G.; Fauzi Soelaiman, T. Nanotechnology—An Introduction for the Standards Community. J. ASTM Int. 2005, 2, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Gnach, A.; Lipinski, T.; Bednarkiewicz, A.; Rybka, J.; Capobianco, J.A. Upconverting nanoparticles: Assessing the toxicity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 1561–1584. [CrossRef]

- National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI). Available online: www.nano.gov (accessed on 22 July 2019).

- Allhoff, F. On the Autonomy and Justification of Nanoethics. Nanoethics 2007, 1, 185–210. [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. There’s plenty of room at the bottom. Eng. Sci. 1960, 23, 22–36. Available at https://calteches.library.caltech.edu/1976/1/1960Bottom.pdf.

- Taniguchi, N.; Arakawa, C.; Kobayashi, T. On the basic concept of nanotechnology. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Production Engineering, Tokyo, Japan, 26–29 August 1974.

- Rothemund, P.W.K.; Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature 2006, 440, 297–302. [CrossRef]

- Seeman, N.C. Nucleic acid junctions and lattices. J. Theor. Biol. 1982, 99, 237–247. [CrossRef]

- Weissig, V.; Pettinger, T.K.; Murdock, N. Nanopharmaceuticals (part 1): Products on the market. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 4357–4373. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Bayda, S.; Hadla, M.; Caligiuri, I.; Russo Spena, C.; Palazzolo, S.; Kempter, S.; Corona, G.; Toffoli, G.; Rizzolio, F. Enhanced Chemotherapeutic Behavior of Open-Caged DNA@Doxorubicin Nanostructures for Cancer Cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 231, 106–110. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Xie, Q.; Sun, Y. Advances in nanomaterial-based targeted drug delivery systems. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023, 13, 11:1177151. [CrossRef]

- Yetisgin, A. A.; Cetinel, S.; Zuvin, M.; Kosar, A.; Kutlu, O. Therapeutic Nanoparticles and Their Targeted Delivery Applications. Molecules 2020, 8, 2193. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shao, A. Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy and Its Role in Overcoming Drug Resistance. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 193. [CrossRef]

- Li, S. D.; Huang, L. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of nanoparticles. Mol. Pharm. 2008, 5, 496–504. [CrossRef]

- Haripriyaa, M.; Suthindhiran, K. Pharmacokinetics of nanoparticles: current knowledge, future directions and its implications in drug delivery. Futur J Pharm Sci 2023, 9, 113. [CrossRef]

- Tuguntaev, R.G.; Hussain, A.; Fu, C.; Haoting Chen, Tao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, L.; Liang, X. J.; Guo, W. Bioimaging guided pharmaceutical evaluations of nanomedicines for clinical translations. J Nanobiotechnol 2022, 20, 236. [CrossRef]

- Park, SM.; Baek, S.; Lee, J. H.; Woo, S. K.; Lee, T. S.; Park, H. S.; Lee, J.; Kang, Y. K.; Kang, . SY.; Yoo, M. Y.; Yoon, H. J.; Kim, B. S.; Lee, K.P.; Moon, B. S. In vivo tissue pharmacokinetics of ERBB2-specific binding oligonucleotide-based drugs by PET imaging. Clin Transl Sci. 2023, 16, 1186-1196. [CrossRef]

- Sudha, R. A. N. A.; Gaurav, M. I. T. T. A. L.; Krishna, C. H. U. T. A. N. I.; & Kumar, S. R. Chapter 6: Nuclear Scintigraphy: A promising tool to evaluate novel and nano-based drug delivery systems. Nanotheranostics (4), 165-185. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263544279_6_Nuclear_Scintigraphy_A_Promising_Tool_to_Evaluate_Novel_and_Nano-Based_Drug_Delivery_Systems.

- Digenis, G.A.; Sandefer, E. P.; Page, R. C.; Doll, W. J. Gamma scintigraphy: an evolving technology in pharmaceutical formulation development-Part 1. Pharmaceutical Science & Technology Today, 1998, 1, 100-108. [CrossRef]

- Terán, M.; Savio, E.; Paolino, A.; Frier, M. Hydrophilic and lipophilic radiopharmaceuticals as tracers in pharmaceutical development: In vitro–In vivo studies. BMC Nucl Med 2005, 5, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Dani, P.; Sharma, R. K. Pharmacoscintigraphy: a blazing trail for the evaluation of new drugs and delivery systems. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst 2009, 26, 373–426. [CrossRef]

- Thombre, A. G.; Shamblin, S. L.; Malhotra, B. K.; Connor, A. L.; Wilding, I. R.; Caldwell, W. B. Pharmacoscintigraphy studies to assess the feasibility of a controlled release formulation of ziprasidone. J Control Release 2015, 213, 10–17. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Khanna, K.; Kumar, N.; Karwasra, R.; Janakiraman, A. K.; Rajagopal, M. S. Illuminating Insights: Clinical Study Harnessing Pharmacoscintigraphy for Permeation Study of Radiolabeled Nimesulide Topical Formulation in Healthy Human Volunteers. Assay Drug Dev Technol 2023, 21, 325–330. [CrossRef]

- Preisig, D.; Varum, F.; Bravo, R.; Hartig, C.; Spleiss, J.; Abbes, S.; Caobelli, F.; Wild, D.; Puchkov, M.; Huwyler, J.; Haschke, M. Colonic delivery of metronidazole-loaded capsules for local treatment of bacterial infections: A clinical pharmacoscintigraphy study. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2021, 165, 22–30. [CrossRef]

- Sandal, N.; Mittal, G.; Bhatnagar, A.; Pathak, D. P.; Singh, A. K. Preparation, Characterization, and In Vivo Pharmacoscintigraphy Evaluation of an Intestinal Release Delivery System of Prussian Blue for Decorporation of Cesium and Thallium. J Drug Deliv 2017, 2017, 4875784. [CrossRef]

- Foppoli, A.; Maroni, A.; Moutaharrik, S.; Melocchi, A.; Zema, L.; Palugan, L.; Cerea, M.; Gazzaniga, A. In vitro and human pharmacoscintigraphic evaluation of an oral 5-ASA delivery system for colonic release. Int J Pharm 2019, 572, 118723. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M. I.; Baboota, S.; Ahuja, A.; Ali, M.; Ali, J.; Sahni, J. K.;Bhatnagar, A. Pharmacoscintigraphic evaluation of potential of lipid nanocarriers for nose-to-brain delivery of antidepressant drug. Int J Pharm 2014, 470, 99–106. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Hu, S.; Teng, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, K.; Xu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Gao, X. Current advance of nanotechnology in diagnosis and treatment for malignant tumors. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 200. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Dani, P.; Sharma, R. K. Pharmacoscintigraphy: A blazing trail for the evaluation of new drugs and delivery systems. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst 2009. 26, 373–426. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. K.; Bhardwaj, N.; Bhatnagar, A. Pharmacoscintigraphy: An unexplored modality in India. Indian J Pharm Sci 2004, 66, 18–25. Available at https://www.ijpsonline.com/articles/pharmacoscintigraphy--an-unexplored-modality-in-india.pdf.

- Gupta, H.; Aqil, M.; Khar, R. K.; Ali, A.; Bhatnagar, A.; Mittal, G. Biodegradable levofloxacin nanoparticles for sustained ocular drug delivery. J Drug Target 2011, 19, 409–417. [CrossRef]

- Cherry, S. R., Sorenson, J. A., & Phelps, M. E. (2012). Physics in nuclear medicine (4th ed.). Elsevier.

- Rahmim, A.; Zaidi, H. PET versus SPECT: Strengths, limitations, and challenges. Nucl Med Commun 2008, 29, 193-207. [CrossRef]

- Mettler, F. A., & Guiberteau, M. J. (2018). Essentials of nuclear medicine imaging (7th ed.). Elsevier.

- Hess, S.; Blomberg, B. A.; Zhu, H. J.; Høilund-Carlsen, P. F.; Alavi, A. The pivotal role of FDG-PET/CT in modern medicine. Acad Radiol 2014, 21, 232-249. [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, S.; Long, NJ. Radiopharmaceuticals for imaging and therapy. Dalton Trans 2011, 21, 6067. [CrossRef]

- Polyak, A.; Ross, T. L. Nanoparticles for SPECT and PET Imaging: Towards Personalized Medicine and Theranostics. Curr Med Chem 2018, 25, 4328–4353. [CrossRef]

- Pellico, J.; Gawne, P. J.; T M de Rosales, R. Radiolabelling of nanomaterials for medical imaging and therapy. Chem Soc Rev 2021, 50, 3355–3423. [CrossRef]

- Varani, M.; Bentivoglio, V.; Lauri, C.; Ranieri, D.; Signore, A. Methods for Radiolabelling Nanoparticles: SPECT Use (Part 1). Biomolecules 2022, 20, 1522. [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, C.; Song, Z.; Ma, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Z.; He, X. Radiolabeling of Nanomaterials: Advantages and Challenges. Front Toxicology 2021, 3,753316. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Pillai, M. R. A.; Knapp, F. F. Radiopharmaceuticals for imaging and therapy in the era of personalized medicine: Current progress and future challenges. Sem Nucl Med 2015, 45, 333–347. [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, R.; Hong, H.; Cai, W. PET imaging of tumor angiogenesis. Theranostics 2014, 4, 419–436.

- Draxler, S.; Roobol, S. J.; Viehweger, C. M.; Kettenbach, K. Radiolabeling strategies for nanoparticles and small-molecule theranostics: A comprehensive review. Front Toxicology 2021, 3, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Lamb, J.; Holland, J. P. Advanced Methods for Radiolabeling Multimodality Nanomedicines for SPECT/MRI and PET/MRI. J Nucl Med 2018, 59, 382-389. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Goel, S.; Sun, X. Chelator-free radiolabeling strategies for inorganic nanomaterials in nuclear imaging and therapy. Chem Soc Rev 2021, 50, 1713-1740. [CrossRef]

- Munaweera, I.; Shi, Y.; Koneru, B.; Saez, R.; Aliev, A.; Di Pasqua, A. J.; Balkus, K. J. Jr. Chemoradiotherapeutic Magnetic Nanoparticles for Targeted Treatment of Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer. Mol Pharm 2015, 12, 3588-3596. [CrossRef]

- Notni, J.; Wester, H. J.; Schottelius, M. New developments in radiometal-based theranostics. J Nucl Med 2019, 60, 1602-1612.

- Garcés, M.; Magnani, N. D.; Pecorelli, A.; Calabró, V.; Marchini, T.; Cáceres, L.; Pambianchi, E.; Galdoporpora, J.; Vico, T.; Salgueiro, J.; Zubillaga, M.; Moretton, M. A.; Desimone, M. F.; Alvarez, S.; Valacchi, G.; Evelson, P. Alterations in oxygen metabolism are associated to lung toxicity triggered by silver nanoparticles exposure. Free Radic Biol Med 2021, 166, 324–336. [CrossRef]

- Garcés, M.; Marchini, T.; Cáceres, L.; Calabró, V.; Mebert, A. M.; Tuttolomondo, M. V.; Vico, T.; Vanasco, V.; Tesan, F.; Salgueiro, J.; Zubillaga, M.; Desimone, M. F.; Valacchi, G.; Alvarez, S.; Magnani, N. D.; Evelson, P. A. xidative metabolism in the cardiorespiratory system after an acute exposure to nickel-doped nanoparticles in mice. Toxicology 2021, 464, 153020. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, P.; Bernabeu, E.; Bertera, F.; Garces, M.; Oppezzo, J.; Zubillaga, M.; Evelson, P.; Salgueiro, M. J.; Moretton, M. A.; Höcht, C.; Chiappetta, D. A. Dual strategy to improve the oral bioavailability of efavirenz employing nanomicelles and curcumin as a bio-enhancer. Int J Pharm 2024, 651, 123734. [CrossRef]

- Galdopórpora, J. M.; Martinena, C.; Bernabeu, E.; Riedel, J.; Palmas, L.; Castangia, I.; Manca, M. L.; Garcés, M.; Lázaro-Martinez, J.; Salgueiro, M. J.; Evelson, P.; Tateosian, N. L.; Chiappetta, D. A.; Moretton, M. A. Inhalable Mannosylated Rifampicin-Curcumin Co-Loaded Nanomicelles with Enhanced In Vitro Antimicrobial Efficacy for an Optimized Pulmonary Tuberculosis Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 959. [CrossRef]

- Grotz, E.; Tateosian, N. L.; Salgueiro, J.; Bernabeu, E.; Gonzalez, L.; Manca, M. L.; Amiano, N. O.; Valenti, D.; Manconi, M.; García, V. E.; Moretton, M.; Chiappetta, D. A. Pulmonary delivery of rifampicin-loaded soluplus micelles against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Drug Delivery Sci Technol 2019, 53, 101170. [CrossRef]

- Martín Giménez, V.M.; Moretton, M.A.; Chiappetta, D.A.; Salgueiro, M.J.; Fornés, M.W.; Manucha, W. Polymeric Nanomicelles Loaded with Anandamide and Their Renal Effects as a Therapeutic Alternative for Hypertension Treatment by Passive Targeting. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 176. [CrossRef]

- Price, E. W.; Orvig, C. Matching chelators to radiometals for radiopharmaceuticals. Chem Soc Rev 2014, 43, 260–290. [CrossRef]

- Kostelnik, T. I.; Orvig, C. Radioactive Main Group and Rare Earth Metals for Imaging and Therapy. Chem Rev 2019, 119, 902–956. [CrossRef]

- Wadas, T. J.; Wong, E. H.; Weisman, G. R.; Anderson, C. J. Coordinating radiometals of copper, gallium, indium, yttrium, and zirconium for PET and SPECT imaging of disease. Chem Rev 2010, 110, 2858–2902. [CrossRef]

- Ramogida, C. F.; Orvig, C. Tumour targeting with radiometals for diagnosis and therapy. Chem Commun 2013, 49, 4720–4739. [CrossRef]

- Zeglis, B. M.; Lewis, J. S. A practical guide to the construction of radiometallated bioconjugates for positron emission tomography. Dalton transactions 2011, 40, 6168–6195. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Medina, C.; Teunissen, A. J. P.; Kluza, E.; Mulder, W. J. M.; van der Meel, R. Nuclear imaging approaches facilitating nanomedicine translation. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2020, 154–155, 123-141. [CrossRef]

- Qaim, S.M.; Scholten, B.; Neumaier, B. New developments in the production of theranostic pairs of radionuclides. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 2018, 318, 1493–1509. [CrossRef]

- Man F.; Gawne, P. J.; T.M. de Rosales, R.. Nuclear imaging of liposomal drug delivery systems: A critical review of radiolabelling methods and applications in nanomedicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2019, 143, 134-160. [CrossRef]

- Quastel, M.; Richter, A.; Levy, J. Tumour scanning with indium-111 dihaematoporphyrin ether. Br J Cancer 1990, 62, 885–890. [CrossRef]

- Franken, P. R.; Guglielmi, J.; Vanhove, C.; Koulibaly, M.; Defrise, M.; Darcourt, J.; Pourcher, T. Distribution and dynamics of (99m)Tc-pertechnetate uptake in the thyroid and other organs assessed by single-photon emission computed tomography in living mice. Thyroid 2010, 20, 519–526. [CrossRef]

- Bottenus, B. N.; Kan, P.; Jenkins, T.; Ballard, B.; Rold, T. L.; Barnes, C.; Cutler, C.; Hoffman, T. J.; Green, M. A.; Jurisson, S. S. Gold(III) bis-thiosemicarbazonato complexes: synthesis, characterization, radiochemistry and X-ray crystal structure analysis. Nucl Med Biol 2010, 37, 41–49. [CrossRef]

- Czernin, J.; Satyamurthy, N.; Schiepers, C. Molecular mechanisms of bone 18F-NaF deposition. J Nucl Med 2010, 51, 1826–1829. [CrossRef]

- Sephton, R. G.; Hodgson, G. S.; De Abrew, S.; Harris, A. W. Ga-67 and Fe-59 distributions in mice. J Nucl Med 1978, 19(8), 930–935. Available at https://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/jnumed/19/8/930.full.pdf.

- Chilton, H. M., Witcofski, R. L.; Watson, N. E. Jr.; Heise, C. M. Alteration of gallium-67 distribution in tumor-bearing mice following treatment with methotrexate: concise communication. J Nuclear Med 1981, 22, 1064–1068. Available at https://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/jnumed/22/12/1064.full.pdf.

- Spetz, J.; Rudqvist, N.; Forssell-Aronsson, E. Biodistribution and dosimetry of free 211At, 125I- and 131I- in rats. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2013, 28, 657–664. [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, R.; Chakraborty, S.; Dash, A. 64Cu2+ Ions as PET Probe: An Emerging Paradigm in Molecular Imaging of Cancer. Mol Pharm 2016, 13, 3601-3612. [CrossRef]

- Piccardo, A.; Paparo, F.; Puntoni, M.; Righi, S.; Bottoni, G.; Bacigalupo, L.; Zanardi, S.; DeCensi, A.; Ferrarazzo, G.; Gambaro, M.; Ruggieri, F. G.; Campodonico, F.; Tomasello, L.; Timossi, L.; Sola, S.; Lopci, E.; Cabria, M. 64CuCl2 PET/CT in Prostate Cancer Relapse. J Nucl Med 2018, 59, 444–451. [CrossRef]

- Abou, D. S; Ku, T.; Smith-Jones, P. M. In vivo biodistribution and accumulation of 89Zr in mice. Nucl Med Biol 2011, 38. 675–681. [CrossRef]

- Graves, S. A.; Hernandez, R.; Fonslet, J.; England, C. G.; Valdovinos, H. F.; Ellison, P. A.; Barnhart, T. E.; Elema, D. R.; Theuer, C. P.; Cai, W.; Nickles, R. J.; Severin, G. W. Novel Preparation Methods of (52)Mn for Immuno PET Imaging. Bioconj Chem 2015, 26, 2118–2124. [CrossRef]

- Vakili, A.; Jalilian, A.R.; Yavari, K.; Shirvani-Arani, S.; Khanchi, A.; Bahrami-Samani, A.; Salimi, B.; Khorrami-Moghadam, A.Preparation and quality control and biodistribution studies of [90Y]-DOTA-cetuximab for radioimmunotherapy. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 2013, 296, 1287–1294. [CrossRef]

- Breeman, W. A.; van der Wansem, K.; Bernard, B. F.; van Gameren, A.; Erion, J. L.; Visser, T. J.; Krenning, E. P.; de Jong, M. The addition of DTPA to [177Lu-DOTA0,Tyr3]octreotate prior to administration reduces rat skeleton uptake of radioactivity. Eur J Nucl Med 2003, 30, 312–315. [CrossRef]

- Dadachova, E.; Bouzahzah, B.; Zuckier, L. S.; Pestell, R. G. Rhenium-188 as an alternative to Iodine-131 for treatment of breast tumors expressing the sodium/iodide symporter (NIS). Nucl Med Biol 2002, 29(1), 13–18. [CrossRef]

- Sukthankar, P.; Avila, A.; Whitaker, S.; Iwamoto, T.; Morgenstern, A.; Apostolidis, C.; Liu, K.; Hanzlik, R.; Dadachova, E.; Tomich, J. Branched amphiphilic peptide capsules: Cellular uptake and retention of encapsulated solutes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1838: 2296-2305. [CrossRef]

- International Commission on Radiological Protection. (2016). Radiological protection in medicine. Annals of the ICRP, 46(1), 1-144.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2022). Ethical considerations for clinical investigations of medical products involving children. https://www.fda.gov/media/161740/download.

- Boschi, S.; Lee, J. T.; Beyer, G. Radiopharmaceuticals for PET and SPECT imaging: A literature review over the last decade. Int J Mol Sci 2002, 23, 5023. [CrossRef]

- Dennahy, I. S.; Han, Z.; MacCuaig, W. M.; Chalfant, H. M.; Condacse, A.; Hagood, J. M.; Claros-Sorto, J. C.; Razaq, W.; Holter-Chakrabarty, J.; Squires, R.; Edil, B. H.; Jain, A.; McNally, L. R. Nanotheranostics for image-guided cancer treatment. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 917. [CrossRef]

- Kunjachan, S.; Ehling, J.; Storm, G.; Kiessling, F.; Lammers, T. Noninvasive imaging of nanomedicines and nanotheranostics: Principles, progress, and prospects. Chem Rev 2015, 115, 10907–10937. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Selvaraj, K. Choice of Nanoparticles for Theranostics Engineering: Surface Coating to Nanovalves Approach. Nanotheranostics 2004, 8, 12-32. [CrossRef]

- Willmann, J.; van Bruggen, N.; Dinkelborg, L.; Gambhir, S. S. Molecular imaging in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2008, 7, 591–607. [CrossRef]

- Penner, N.; Xu, L; Prakash, C. Radiolabeled absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion studies in drug development: Why, when, and how? Chem Res Toxicol 2012, 25(3), 513–531. [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; England, C. G.; Chen, F.; Cai, W. Positron emission tomography and nanotechnology: A dynamic duo for cancer theranostics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2017, 113, 157–176. [CrossRef]

- Goel, M.; Mackeyev, Y.; Krishnan, S. Radiolabeled nanomaterial for cancer diagnostics and therapeutics: principles and concepts. Cancer Nanotechnol 2023,14:15. [CrossRef]

- Salgueiro, M. J.; Portillo, M.; Tesán, F.; Nicoud, M.; Medina, V.; Moretton, M.; Chiappetta, D.; Zubillaga, M. Design and development of nanoprobes radiolabelled with 99mTc for the diagnosis and monitoring of therapeutic interventions in oncology preclinical research. EJNMMI radiopharmacy and chemistry 2024, 9, 74. [CrossRef]

- Tesán, F. C.; Portillo, M. G.; Moretton, M. A.; Bernabeu, E.; Chiappetta, D. A.; Salgueiro, M. J.; Zubillaga, M. B. Radiolabeling and biological characterization of TPGS-based nanomicelles by means of small animal imaging. Nucl Med Biol 2017, 44, 62–68. [CrossRef]

- Tesán, F. C.; Nicoud, M. B.; Nuñez, M.; Medina, V. A.; Chiappetta, D. A.; Salgueiro, M. J. 99mTc-Radiolabeled TPGS nanomicelles outperform 99mTc-sestamibi as a breast cancer imaging agent. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2019, 23, 2019, 4087895. [CrossRef]

- Tesán, F. C.; Portillo, M.; Medina, V.; Nuñez, M.; Zubillaga, M.; Salgueiro, M. J. Tumor imaging in experimental animal models of breast carcinoma with routinely available 99mTc-sestamibi. Int J Res Pharm L Sci 2015, 3, 254–259.

- Moretton, M. A.; Bernabeu, E.; Grotz, E.; Gonzalez, L.; Zubillaga, M.; Chiappetta, D. A. A glucose-targeted mixed micellar formulation outperforms Genexol in breast cancer cells. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2017, 114, 305–316. [CrossRef]

- Nicoud, M. B.; Ospital, I. A.; Táquez Delgado, M. A.; Riedel, J.; Fuentes, P.; Bernabeu, E.; Rubinstein, M. R.; Lauretta, P.; Martínez Vivot, R.; Aguilar, M.; Salgueiro M. J.; Speisky D.; Moretton M.; Chiappetta, D. A.; Medina V. A. Nanomicellar formulations loaded with histamine and paclitaxel as a new strategy to improve chemotherapy for breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 3546. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The diagram outlines key stages of pharmacoscintigraphy in the research pipeline of nanotheranostics.

Figure 1.

The diagram outlines key stages of pharmacoscintigraphy in the research pipeline of nanotheranostics.

Figure 2.

Conceptual overview of pharmacoscintigraphy, a nuclear imaging technique used to study the biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of radiolabeled drugs and nanomedicines. The schematic highlights the fundamental principles of this technique, emphasizing its role in preclinical and clinical research for optimizing nanotheranostic platforms.

Figure 2.

Conceptual overview of pharmacoscintigraphy, a nuclear imaging technique used to study the biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of radiolabeled drugs and nanomedicines. The schematic highlights the fundamental principles of this technique, emphasizing its role in preclinical and clinical research for optimizing nanotheranostic platforms.

Figure 3.

Overview of pharmacoscintigraphic Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) studies for nanomedicines. It details the methodologies employed for radiolabeling nanocarriers, imaging techniques for tracking biodistribution, and strategies for analyzing excretion pathways. These studies are crucial for ensuring the safety and efficacy of nanomedicines before clinical translation.

Figure 3.

Overview of pharmacoscintigraphic Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) studies for nanomedicines. It details the methodologies employed for radiolabeling nanocarriers, imaging techniques for tracking biodistribution, and strategies for analyzing excretion pathways. These studies are crucial for ensuring the safety and efficacy of nanomedicines before clinical translation.

Figure 4.

Comprehensive overview of preclinical imaging studies conducted to evaluate the theranostic potential of nanomicelles in different cancer models (4T1 breast cancer, NMU-induced breast cancer, and colorectal cancer). The schematic categorizes micelles into pure, hybrid, and functionalized formulations, highlighting their targeting efficiency and therapeutic capabilities. Key functionalization strategies, such as glucose and bevacizumab conjugation, are also illustrated to demonstrate their impact on tumor targeting and therapeutic outcomes. A-Schematic representation of the experimental workflow for radiolabeling, in vivo administration, and imaging of nanotheranostic formulations. The process begins with the synthesis and radiolabeling of micelles, followed by intravenous administration in tumor-bearing animal models. Serial imaging acquisitions are performed at different time points to track biodistribution, tumor accumulation, and excretion pathways; B-Representative imaging results from three different tumor models: 4T1 breast cancer, NMU-induced breast cancer, and colorectal cancer. The images illustrate the dynamic distribution of radiolabeled micelles within the body, highlighting differences in tumor uptake and clearance patterns among the different formulations; C-Comparative analysis of micelle formulations, categorized into pure micelles, hybrid micelles, and functionalized micelles. Functionalization strategies, such as glucose and bevacizumab conjugation, are shown to increase tumor targeting efficiency. Graphical representations of quantitative imaging data are included to demonstrate variations in tumor-to-background ratios and excretion kinetics across different formulations. Abbreviations: TPGS: D-α-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol succinate, Sol: Soluplus®, NMU: N-nitroso-N-methylurea, TPGS+sol: hybrid micelle with Soluplus®+TPGS, Sol+glu: Soluplus® micelle functionalized with glucose, Sol+bmab: Soluplus® micelle functionalizaed with bevacizumab, Sol+H+Pax: Soluplus® micelle loaded with histamine and paclitaxel, Sol+glu+H+Pax: : Soluplus® micelle functionalized with glucose loaded with histamine and paclitaxel.

Figure 4.

Comprehensive overview of preclinical imaging studies conducted to evaluate the theranostic potential of nanomicelles in different cancer models (4T1 breast cancer, NMU-induced breast cancer, and colorectal cancer). The schematic categorizes micelles into pure, hybrid, and functionalized formulations, highlighting their targeting efficiency and therapeutic capabilities. Key functionalization strategies, such as glucose and bevacizumab conjugation, are also illustrated to demonstrate their impact on tumor targeting and therapeutic outcomes. A-Schematic representation of the experimental workflow for radiolabeling, in vivo administration, and imaging of nanotheranostic formulations. The process begins with the synthesis and radiolabeling of micelles, followed by intravenous administration in tumor-bearing animal models. Serial imaging acquisitions are performed at different time points to track biodistribution, tumor accumulation, and excretion pathways; B-Representative imaging results from three different tumor models: 4T1 breast cancer, NMU-induced breast cancer, and colorectal cancer. The images illustrate the dynamic distribution of radiolabeled micelles within the body, highlighting differences in tumor uptake and clearance patterns among the different formulations; C-Comparative analysis of micelle formulations, categorized into pure micelles, hybrid micelles, and functionalized micelles. Functionalization strategies, such as glucose and bevacizumab conjugation, are shown to increase tumor targeting efficiency. Graphical representations of quantitative imaging data are included to demonstrate variations in tumor-to-background ratios and excretion kinetics across different formulations. Abbreviations: TPGS: D-α-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol succinate, Sol: Soluplus®, NMU: N-nitroso-N-methylurea, TPGS+sol: hybrid micelle with Soluplus®+TPGS, Sol+glu: Soluplus® micelle functionalized with glucose, Sol+bmab: Soluplus® micelle functionalizaed with bevacizumab, Sol+H+Pax: Soluplus® micelle loaded with histamine and paclitaxel, Sol+glu+H+Pax: : Soluplus® micelle functionalized with glucose loaded with histamine and paclitaxel.

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of Imaging Techniques.

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of Imaging Techniques.

| Feature |

Gamma Scintigraphy |

SPECT |

PET |

| Spatial Resolution |

Low |

Moderate |

High |

| Sensitivity |

Moderate |

High |

Very High |

| Quantification |

Limited |

Semi-quantitative |

Fully Quantitative |

| Cost |

Low |

Moderate |

High |

| Applications |

Gastrointestinal transit and retention studies Pulmonary drug deposition evaluation Nanoparticle biodistribution assessments |

Imaging organ-specific drug accumulation and clearance Evaluating nanoparticle targeting to tumors and inflammation sites Monitoring therapeutic responses in nanotheranostics |

Studying tumor targeting efficiency of nanomedicines Quantifying receptor-mediated nanoparticle uptake Investigating drug metabolism and clearance pathways |

Table 2.

Common Radionuclides Used in PET and SPECT Imaging.

Table 2.

Common Radionuclides Used in PET and SPECT Imaging.

| Radionuclide |

Imaging Modality |

Half-Life |

Energy (keV) |

Primary Applications |

| Fluorine-18 (18F) |

PET |

109.8 min |

511 |

Oncology, neurology, cardiology |

Carbon-11 (11C)

|

PET

|

20.4 min

|

511

|

Neurology, oncology, molecular imaging |

| Zirconium-89 (89Zr) |

PET |

78.4 h |

511 |

Immuno-PET, antibody labeling |

| Copper-64 (64Cu) |

PET |

12.7 h |

511 |

Radiotherapy, imaging of hypoxia |

| Gallium-68 (68Ga) |

PET |

68 min |

511 |

Peptide receptor imaging, neuroendocrine tumors |

| Technetium-99m (99mTc) |

SPECT |

6.0 h |

140 |

General nuclear medicine imaging |

| Indium-111 (111In) |

SPECT |

2.8 d |

171, 245 |

Infection imaging, leukocyte labeling |

| Iodine-123 (123I) |

SPECT |

13.2 h |

159 |

Thyroid imaging, neuroimaging |

| Luthetium-177 (177Lu)* |

SPECT-therapy |

6.7 d |

113, 208 |

Oncology |

Table 3.

Common Chelators and Applications:.

Table 3.

Common Chelators and Applications:.

| Chelator |

Commonly Used Radionuclides |

Application |

| DTPA (Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid) |

99mTc, 111In |

SPECT imaging |

| DOTA (1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid) |

177Lu, 68Ga, 64Cu |

PET imaging & radiotherapy |

| NOTA (1,4,7-Triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid) |

68Ga, 64Cu |

PET imaging |

| DFO (Deferoxamine) |

89Zr |

Immuno-PET imaging |

Table 4.

Characteristics of radiolabeling methods.

Table 4.

Characteristics of radiolabeling methods.

| Radiolabeling Method |

Nanocarrier Examples |

Radionuclides Used |

Advantages |

Limitations |

| Direct Radiolabeling |

Gold, Iron Oxide NPs |

99mTc, 188Re |

Simple and fast |

Lower in vivo stability |

| Chelator-Based |

Liposomes, Micelles |

68Ga, 177Lu, 64Cu |

High stability |

Requires chemical modification |

| Covalent Binding |

Proteins, Peptides |

125I, 131I, 64Cu |

Strong attachment |

May alter nanocarrier properties |

| Encapsulation |

Liposomes, Silica NPs |

111In, 99mTc |

Maintains nanoparticle integrity |

Risk of leakage |

| Neutron Activation |

Holmium Oxide NPs |

166Ho, 89Zr |

Nochemical modification required |

Limited availability |

Table 5.

Example Applications:.

Table 5.

Example Applications:.

| Nanotheranostic System |

Radionuclide |

Labeling Strategy |

Application |

| Polymeric micelles |

99mTc |

Direct adsorption |

Tumor imaging |

| Liposomes |

111In |

Encapsulation |

Drug delivery tracking |

| Iron oxide nanoparticles |

89Zr |

Chelation (DFO) |

Long-term biodistribution studies |

| Mesoporous silica |

177Lu |

Lattice incorporation |

Radionuclide therapy |

Table 6.

Comparative Analysis of Nanomicelle Performance.

Table 6.

Comparative Analysis of Nanomicelle Performance.

| Nanomicelle Type |

Functionalization |

Tumor Uptake |

Imaging Performance |

Theranostic Potential |

| TPGS-Based Micelles |

None |

Low (4T1 model)

High (NMU model) |

Poor imaging contrast

Superior to 99mTc-sestamibi |

Limited as standalone therapy

Potential imaging agent |

| Soluplus® Micelles |

None |

Moderate (EPR effect) |

Good imaging contrast |

Potential for passive drug release |

| Soluplus® + TPGS Micelles |

None |

High (4T1 model) |

Improved tumor localization |

Synergistic tumor targeting |

| Soluplus® Micelles |

Glucose

Bevacizumab |

High (GLUT1-mediated)

Very High (VEGF-targeting) |

Improved tumor imaging

Strong imaging contrast and retention |

Greater drug targeting capability

Optimal for guided drug delivery |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).