Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Geographical Barriers to Healthcare Access

1.2. Healthcare Infrastructure and Access in Nepal

1.3. Neonatal Mortality and Health Disparities in Remote Nepal

2. Methods

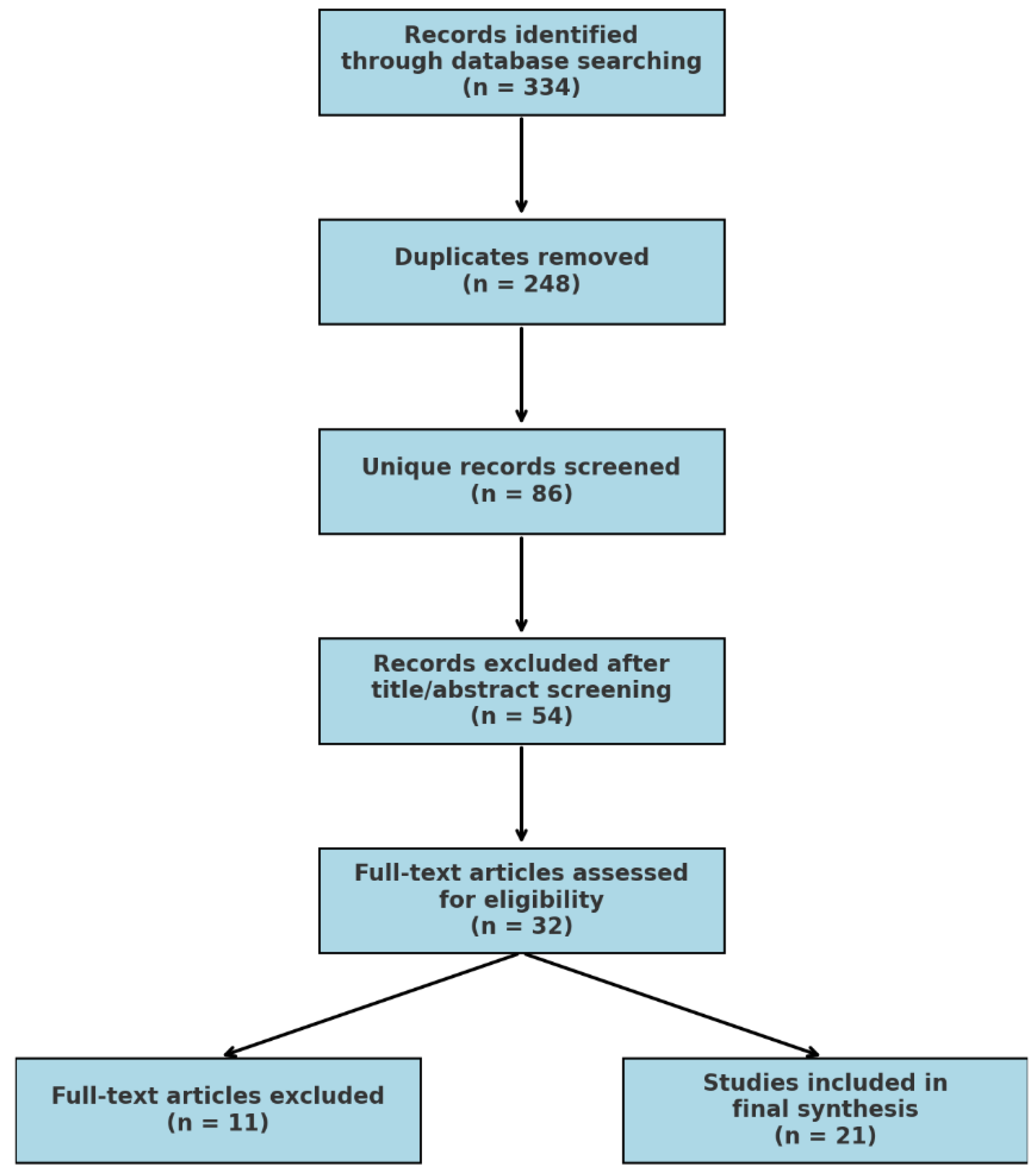

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

- ‘neonatal mortality’ OR ‘infant mortality’

- ‘neonatal resuscitation’ OR ‘Helping Babies Breathe (HBB)’

- ‘newborn care’ OR ‘birth outcomes’

- ‘healthcare disparities’ OR ‘healthcare access’

- ‘skilled birth attendants’ OR ‘healthcare workers’

- ‘remote regions’ OR ‘rural healthcare’ OR ‘resource-limited settings’

- ‘geographical barriers’ OR ‘terrain’ OR ‘infrastructure challenges’

- ‘Nepal’ AND ‘hilly regions’ OR ‘mountainous regions’

- ‘antenatal care’ OR ‘delivery practices’

- ‘cultural barriers’ OR ‘socio-cultural factors’ OR ‘ethnic groups’

- ‘healthcare interventions’ OR ‘healthcare programs’

2.1.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Quantitative and qualitative studies

- Randomized controlled trials

- Observational studies

2.2. Data Extraction and Analysis

- Study design and population

- Neonatal mortality rates and birth outcomes

- Healthcare access and service availability

- Effectiveness of interventions

- Geographical and cultural factors influencing neonatal healthcare

2.3. Narative Synthesis

2.3.1. The Four-Stage Narrative Synthesis Framework

2.3.2. Preliminary Synthesis

2.3.3. Exploring Relationships Within and Between Studies

- Study type (qualitative vs. quantitative)

- Geographical region (hilly vs. mountainous)

- Type of intervention (e.g., HBB, SBA programs)

2.3.4. Critical Appraisal of Studies

- Study design and methodology

- Sample size and representativeness

- Intervention effectiveness and bias evaluation

2.4. Synthesis and Presentation of Findings

- Regional disparities in neonatal mortality and birth outcomes

- Impact of neonatal resuscitation programs such as HBB

- Infrastructure and resource gaps in neonatal healthcare

- Geographical barriers to healthcare access

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Regional Disparities in Neonatal Mortality and Birth Outcomes

4.2. Impact of Neonatal Resuscitation Programs Such as HBB

4.3. Infrastructure and Resource Gaps in Neonatal Healthcare

4.4. Geographical Barriers to Healthcare Access

5. Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhattarai, K.; Conway, D. Contemporary environmental problems in Nepal: Geographic perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.R.; Shakya, P.; Karmacharya, B.; Xu, D.R.; Hao, Y.T.; Lai, Y.S. Equity of geographical access to public health facilities in Nepal. BMJ Glob Health 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, A.; Byrne, A.; Morgan, A.; Jimenez-Soto, E. Utilisation of health services and geography: deconstructing regional differences in barriers to facility-based delivery in Nepal. Matern Child Health J 2015, 19, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasti, S.P.; van Teijlingen, E.; Rushton, S.; Subedi, M.; Simkhada, P.; Balen, J. Overcoming the challenges facing Nepal's health system during federalisation: An analysis of health system building blocks. Health Res Policy Syst 2023, 21, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rublee, C.; Bhatta, B.; Tiwari, S.; Pant, S. Three Climate and Health Lessons from Nepal Ahead of COP28. NAM Perspect 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, N.; Chongsuvivatwong, V.; Geater, A.F.; Ulstein, M.; Bechtel, G.A. Infant death rates and animal-shed delivery in remote rural areas of Nepal. Social Science & Medicine 2000, 51, 1447–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, P.R.; Agho, K.; Renzaho, A.Μ.Ν.; Nisha, M.K.; Dibley, M.J.; Raynes-Greenow, C. Factors Associated With Perinatal Mortality in Nepal: Evidence From Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2001–2016. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, B.K.; Kittel, G. Neonatal mortality and child health in a remote rural area in Nepal: a mixed methods study. BMJ Paediatr Open 2019, 3, e000519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalter, H.D.; Setel, P.W.; Deviany, P.E.; Nugraheni, S.A.; Sumarmi, S.; Weaver, E.H.; Latief, K.; Rianty, T.; Nandiaty, F.; Anggondowati, T.; et al. Modified Pathway to Survival highlights importance of rapid access to quality institutional delivery care to decrease neonatal mortality in Serang and Jember districts, Java, Indonesia. J Glob Health 2023, 13, 04020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuikel, B.S.; Shrestha, A.; Xu, D.R.; Shahi, B.B.; Bhandari, B.; Mishra, R.K.; Bhattrai, N.; Acharya, K.; Timalsina, A.; Dangaura, N.R.; et al. A critical analysis of health system in Nepal: Perspective's based on COVID-19 response. Dialogues Health 2023, 3, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, R.; Bohara, D.; Kc, M.; Shanmuganathan, S.; Mistry, S.K.; Yadav, U.N. Challenges and opportunities for implementing digital health interventions in Nepal: A rapid review. Front Digit Health 2022, 4, 861019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, K.B.; Koirala, N.; Ivanova, O.; Bastola, R.; Singh, D.; Magar, K.R.; Banstola, B.; Adhikari, R.P.; Giedraitis, V.; Paudel, D.; et al. Newborn morbidities and care procedures at the special newborn care units of Gandaki Province, Nepal: A retrospective study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2024, 24, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, G.; Paudel, P.; Shrestha, P.; Jnawali, S.P.; Jha, D.K.; Ojha, T.R.; Lamichhane, B. Free Newborn Care Services: A New Initiative in Nepal. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council 2018, 16, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, R.B.; Mishra, S.R.; Khanal, V.; Gelal, K.; Neupane, S. Newborn Health Interventions and Challenges for Implementation in Nepal. Frontiers in Public Health 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, V.; Bista, S.; Mishra, S.R. Prevalence of and factors associated with home births in western Nepal: Findings from the baseline of a community-based prospective cohort study. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health 2024, 27, 101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, M.; Javanparast, S.; Newman, L.; Dasvarma, G. Health system barriers influencing perinatal survival in mountain villages of Nepal: Implications for future policies and practices. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition 2018, 37, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, A.R.; Adhikari, B.; Lamichhane, B.; Joshi, D.; Regmi, S.; Lal, B.K.; Dahal, S.; Baral, S.C. Service availability and readiness for basic emergency obstetric and newborn care: Analysis from Nepal Health Facility Survey 2021. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0282410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, K.; Subedi, R.K.; Dahal, S.; Karkee, R. Basic emergency obstetric and newborn care service availability and readiness in Nepal: Analysis of the 2015 Nepal Health Facility Survey. PloS one 2021, 16, e0254561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, P.; Dhungana, R.; Gamboa, E.; Davis, S.; Visick, M. Newborn Resuscitation Scale Up and Retention Program Associated with Improved Neonatal Outcomes in Western Nepal. Int J Pediatr Res 2022, 8, 087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaphle, S.; Hancock, H.; Newman, L.A. Childbirth traditions and cultural perceptions of safety in Nepal: Critical spaces to ensure the survival of mothers and newborns in remote mountain villages. Midwifery 2013, 29, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version 2006, 1, b92. [Google Scholar]

- Snilstveit, B.; Oliver, S.; Vojtkova, M. Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. Journal of Development Effectiveness 2012, 4, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, M.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Roberts, H.; Britten, N.; Popay, J. Testing methodological guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: Effectiveness of interventions to promote smoke alarm ownership and function. Evaluation 2009, 15, 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASP. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist. Available at: https://casp-uk.net, 2020.

- Bhattarai, B.; Panthi, S.; Yadav, G.K.; Gautam, S.; Acharya, R.; Neupane, D.; Khanal, N.; Khatri, B.; Neupane, K.; Adhikari, S.; et al. Association of geographic distribution and birth weight with sociodemographic factors of the maternal and newborn child of hilly and mountain regions of eastern Nepal: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Paediatr Open 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choulagai, B. Barriers to using skilled birth attendants' services in mid- and far-western Nepal: A cross-sectional study. BMC International Health and Human Rights 2013, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kc, A.; Bergström, A.; Chaulagain, D.; Brunell, O.; Ewald, U.; Gurung, A.; Eriksson, L.; Litorp, H.; Wrammert, J.; Grönqvist, E.; et al. Scaling up quality improvement intervention for perinatal care in Nepal (NePeriQIP): Study protocol of a cluster randomised trial. BMJ global health 2017, 2, e000497–e000497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maru, S.; Bangura, A.H.; Mehta, P.; Bista, D.; Borgatta, L.; Pande, S.; Citrin, D.; Khanal, S.; Banstola, A.; Maru, D. Impact of the roll out of comprehensive emergency obstetric care on institutional birth rate in rural Nepal. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenhals, S.; Folsom, S.; Levy, D.; Sherpa, A.; Fassl, B. Critical Assessment of Maternal-Newborn Care Delivery in Solukhumbu, Nepal. Annals of Global Health 2017, 83, 202–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Shankar, P.R. Knowledge regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation among health assistants in Nepal: A cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0293323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, P.; Simkhada, P.; Bissell, P.; van Teijlingen, E.; Khatri, R.; Stephenson, J. Health facility preparedness of maternal and neonatal health services: A survey in Jumla, Nepal. BMC Health Services Research 2021, 21, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.W.; Levy, D.P.; Sherpa, A.J.; Lama, L.; Judkins, A.; Chambers, A.A.; Crandall, H.; Schoenhals, S.; Bjella, K.B.; Vaughan, J.H.; et al. Analysis of the Perinatal Care System in a Remote and Mountainous District of Nepal. Matern Child Health J 2022, 26, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuladhar, S. Changes in health facility readiness for obstetric and neonatal care services in Nepal: An analysis of cross-sectional health facility survey data in 2015 and 2021. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; van Teijlingen, E.; Hundley, V.; Angell, C.; Simkhada, P. Dirty and 40 days in the wilderness: Eliciting childbirth and postnatal cultural practices and beliefs in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2016, 16, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, M.; Bhatta, M. Newborn Care Practices of Mothers in a Rural Community in Baitadi, Nepal. Health Prospect 2018, 10, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S. Chhaupadi practice in Nepal: A literature review. World Medical & Health Policy 2022, 14, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author Year | Study Design | Study Population | Key Themes | Findings | Study Quality and Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acharya, et al. (2021) [18] |

Cross-sectional | 457 health facilities across Nepal | Healthcare infrastructure, facility readiness, emergency obstetric care | Hospitals had higher neonatal care readiness. Only 16.1% offered assisted vaginal birth, 10% provided anticonvulsants. Readiness linked to staffing levels, 24-hour service, and newborn death review. | Moderate risk of bias due to self-reported facility readiness assessments |

| Bhattarai, et al. (2022) [25] |

Cross-sectional. | 1,386 term singleton births from 4 hospitals in eastern Nepal | Geographic disparities, birth weight, maternal factors | Low birth weight was higher in hilly regions (6.6%). Dalit ethnicity, low maternal age, and higher antenatal visits associated with hilly region births. | Low risk; large dataset but limited causal inferences |

| Cao, et al. (2021) [2] |

Spatial analysis | 5,553 public health facilities, 2020 population data | Healthcare access, geographic barriers | 92.54% of population accessed facilities within 15 min via motorized transport. Accessibility declined for higher-level facilities. Recommended new health centers in underserved areas. | Moderate risk due to reliance on modeled transport data |

| Choulagai(2013) [26] | Cross-sectional | 2,481 women who gave birth in last 12 months in three districts | Skilled birth attendants, barriers to healthcare access | 48% used SBAs. Barriers included distance (45%) and transport issues (21%). Antenatal care improved SBA utilization. | Low risk; strong sample representation but lacks qualitative depth |

| Ghimire (2019) [7] |

Demographic health survey analysis | 23,335 pregnancies from Nepal Demographic Health Survey | Neonatal mortality trends, regional disparities | Perinatal mortality rate was 42 per 1,000 births. Higher mortality in mountainous regions, younger mothers, poor sanitation. | Low risk; robust dataset but lacks intervention-specific data |

| Kaphle, et al. (2013) [20] |

Qualitative | 25 pregnant/postnatal women, 16 healthcare/community stakeholders in Mugu | Cultural barriers, birth practices | Animal-shed births preferred due to spiritual beliefs, leading to neonatal risks. Cultural beliefs conflicted with medical advice. | Moderate risk due to small sample size and subjective reporting |

| Karki & Kittel (2019) [8] |

Mixed-methods | 12,287 people from Dolpa district | Neonatal mortality, cultural influences, healthcare access | Neonatal mortality rate was 67 per 1,000. Cultural mistrust of modern medicine and poor health infrastructure led to increased deaths. | Moderate risk; strong sample but relies on retrospective data |

| Kc, et al. (2017) [27] |

Secondary analysis | Women aged 15-49 from Nepal Demographic and Health Surveys (2001, 2006, 2011, 2016) | Neonatal mortality trends, socioeconomic disparities | Neonatal mortality decreased between 2001 and 2016, but disparities widened between wealth quintiles. Tetanus vaccination, maternal education, and household conditions were key predictors of neonatal mortality. | Low risk; robust dataset but limited ability to analyze causal relationships |

| Khanal, et al. (2024) [15] |

Prospective cohort | 735 mother-infant pairs in western Nepal | Home births, healthcare utilization | 11.8% had home births. Low antenatal care increased likelihood of home birth. Higher wealth correlated with hospital births. | Low risk; strong methodology but lacks long-term neonatal tracking |

| Khatri, et al. (2022) [14] |

Cross-sectional | 901 antenatal care facilities and 454 perinatal service providers | Healthcare infrastructure, service quality | Structural quality scores were higher for private facilities; government-run facilities in rural areas showed poor readiness for maternal and newborn care. | Moderate risk; self-reported facility assessments limit objectivity |

| Maru, et al. (2017) [28] |

Pre-post intervention | 210 postpartum women in rural Nepal | Emergency obstetric care, birth facility utilization | Institutional birth rates rose from 30% to 77% after CEmOC introduction. Availability improved birth planning and safety perceptions. | Low risk; rigorous comparison but limited to one hospital area |

| Naresh, et al. (2022) [19] |

Prospective observational | 18 health facilities assessing 49,809 births | Newborn resuscitation, HBB | HBB training reduced neonatal deaths and birth asphyxia. Skill retention remained high over 24 months. | Low risk; large dataset, but results may not generalize to non-participating regions |

| Pandey, et al. (2023) [17] |

Cross-sectional | 804 health facilities in Nepal. | Emergency obstetric care, facility readiness | Service availability for neonatal care remains inadequate. Only 43.7% of facilities met Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care (CEmONC) standards. | Moderate risk due to facility-reported data |

| Paudel, et al. (2018) [16] |

Qualitative | 42 interviews with women who experienced perinatal deaths and 20 interviews with healthcare workers | Healthcare system barriers, perinatal mortality | Poor governance, lack of community engagement, and weak health system accountability contributed to high perinatal mortality in remote villages. | Moderate risk; small sample limits generalizability |

| Schoenhals, et al. (2017) [29] |

Cross-sectional | 122 women who gave birth in the past 24 months in Solukhumbu District | Maternal-newborn health practices | Only 26% of births occurred in health facilities, with 70% at home. Limited access to skilled birth attendants contributed to neonatal complications. | Moderate risk; small sample size but relevant to high-altitude populations |

| Shrestha & Jung (2023) [13] |

Quasi-experimental | Rural Nepalese children from Nepal Living Standards Survey data | Healthcare reform, gender-based disparities | Healthcare reform reduced infant mortality for boys but had no significant effect on girls, suggesting persistent societal gender biases in healthcare access. | Moderate risk; reliance on secondary data may not capture all confounders |

| Singh & Shankar (2023) [30] |

Cross-sectional | 500 health assistants registered with Nepal Health Professional Council | CPR knowledge among healthcare workers | Only 12.8% had CPR training; none had performed CPR. Training gaps highlight urgent need for competency development. | Low risk; strong methodology but limited to one profession |

| Tamang, et al. (2021) [31] |

Descriptive cross-sectional | 31 state-run health facilities in Jumla District | Facility preparedness, medicine availability | Many facilities lacked essential neonatal medicines and transport services. Emergency preparedness was inadequate in most centers. | Moderate risk; self-reported data may limit reliability |

| Thapa, et al. (2000) [6] |

Community-based retrospective | 3,007 live-born children from 772 mothers in Jumla, Nepal | Animal-shed births, neonatal mortality | Neonatal mortality was significantly higher for births occurring in animal sheds compared to homes. Lack of hygiene and medical care contributed to higher risk. | Moderate risk; older dataset but relevant to cultural birth practices |

| Thomas, et al. (2022) [32] |

Cross-sectional | 487 households and 19 health facilities in Solukhumbu District | Facility readiness, SBA availability | Only 35.7% of births occurred in health facilities. Lack of trained obstetric and neonatal staff hindered service readiness. | Low risk; large sample, but self-reported barriers may introduce bias |

| Tuladhar (2024) [33] |

Cross-sectional | Survey data from 2015 and 2021 assessing facility readiness | Neonatal service provision, healthcare trends | By 2021, only 2.2% of facilities stocked all essential neonatal medicines. Readiness for neonatal care remained critically low, particularly in rural areas. | Moderate risk; government survey data may not reflect all local disparities |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).