Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

05 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Current Nutritional Treatment for MASLD

3. Milpa Diet and Its Effect on the Prevention and Treatment of MASLD

4. Potential Benefits of Milpa Diet Components

4.1. Protein Sources Suggested and Their Benefits

4.2. Benefits of Carbohydrates and Lipids in the Milpa Diet

4.3. Antioxidant and Micronutrients

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Futures Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J Hepatol. 2023;79: 1542–1556. [CrossRef]

- Chan W-K, Chuah K-H, Rajaram RB, Lim L-L, Ratnasingam J, Vethakkan SR. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A State-of-the-Art Review. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2023;32: 197–213. [CrossRef]

- Le MH, Yeo YH, Li X, Li J, Zou B, Wu Y, et al. 2019 Global NAFLD Prevalence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20: 2809–2817.e28. [CrossRef]

- Huh Y, Cho YJ, Nam GE. Recent Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2022;31: 17–27. [CrossRef]

- Fleischman MW, Budoff M, Zeb I, Li D, Foster T. NAFLD prevalence differs among hispanic subgroups: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20: 4987–4993. [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Cevallos P, Torre A, Mendez-Sanchez N, Uribe M, Chavez-Tapia NC. Epidemiological and Genetic Aspects of NAFLD and NASH in Mexico. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2022;19: 68–72. [CrossRef]

- Martínez LA, Larrieta E, Kershenobich D, Torre A. The Expression of PNPLA3 Polymorphism could be the Key for Severe Liver Disease in NAFLD in Hispanic Population. Ann Hepatol. 2017;16: 909–915. [CrossRef]

- Chinchilla-López P, Ramírez-Pérez O, Cruz-Ramón V, Canizales-Quinteros S, Domínguez-López A, Ponciano-Rodríguez G, et al. More Evidence for the Genetic Susceptibility of Mexican Population to Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease through PNPLA3. Ann Hepatol. 2018;17: 250–255. [CrossRef]

- Huttasch M, Roden M, Kahl S. Obesity and MASLD: Is weight loss the (only) key to treat metabolic liver disease? Metabolism. 2024;157: 155937. [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Obes Facts. 2024;17: 374–444. [CrossRef]

- Younossi ZM, Zelber-Sagi S, Henry L, Gerber LH. Lifestyle interventions in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20: 708–722. [CrossRef]

- Montemayor S, Mascaró CM, Ugarriza L, Casares M, Llompart I, Abete I, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and NAFLD in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome: The FLIPAN Study. Nutrients. 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Hayat U, Siddiqui AA, Okut H, Afroz S, Tasleem S, Haris A. The effect of coffee consumption on the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver fibrosis: A meta-analysis of 11 epidemiological studies. Ann Hepatol. 2021;20: 100254. [CrossRef]

- Marti-Aguado D, Calleja JL, Vilar-Gomez E, Iruzubieta P, Rodríguez-Duque JC, Del Barrio M, et al. Low-to-moderate alcohol consumption is associated with increased fibrosis in individuals with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2024;81: 930–940. [CrossRef]

- Stine JG, Long MT, Corey KE, Sallis RE, Allen AM, Armstrong MJ, et al. American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) International Multidisciplinary Roundtable report on physical activity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7. [CrossRef]

- Cuthbertson DJ, Keating SE, Pugh CJA, Owen PJ, Kemp GJ, Umpleby M, et al. Exercise improves surrogate measures of liver histological response in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Liver Int. 2024;44: 2368–2381. [CrossRef]

- Zizumbo-Villarreal D, Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR). Departamento de Agricultura, Sociedad y Ambiente, Colunga-GarcíaMarín P, Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR). Departamento de Agricultura, Sociedad y Ambiente. La milpa del occidente de Mesoamérica: profundidad histórica, dinámica evolutiva y rutas de dispersión a Suramérica. Rev geogr agríc. 2017; 33–46.

- Sánchez-Velázquez OA, Luna-Vital DA, Morales-Hernandez N, Contreras J, Villaseñor-Tapia EC, Fragoso-Medina JA, et al. Nutritional, bioactive components and health properties of the milpa triad system seeds (corn, common bean and pumpkin). Front Nutr. 2023;10: 1169675. [CrossRef]

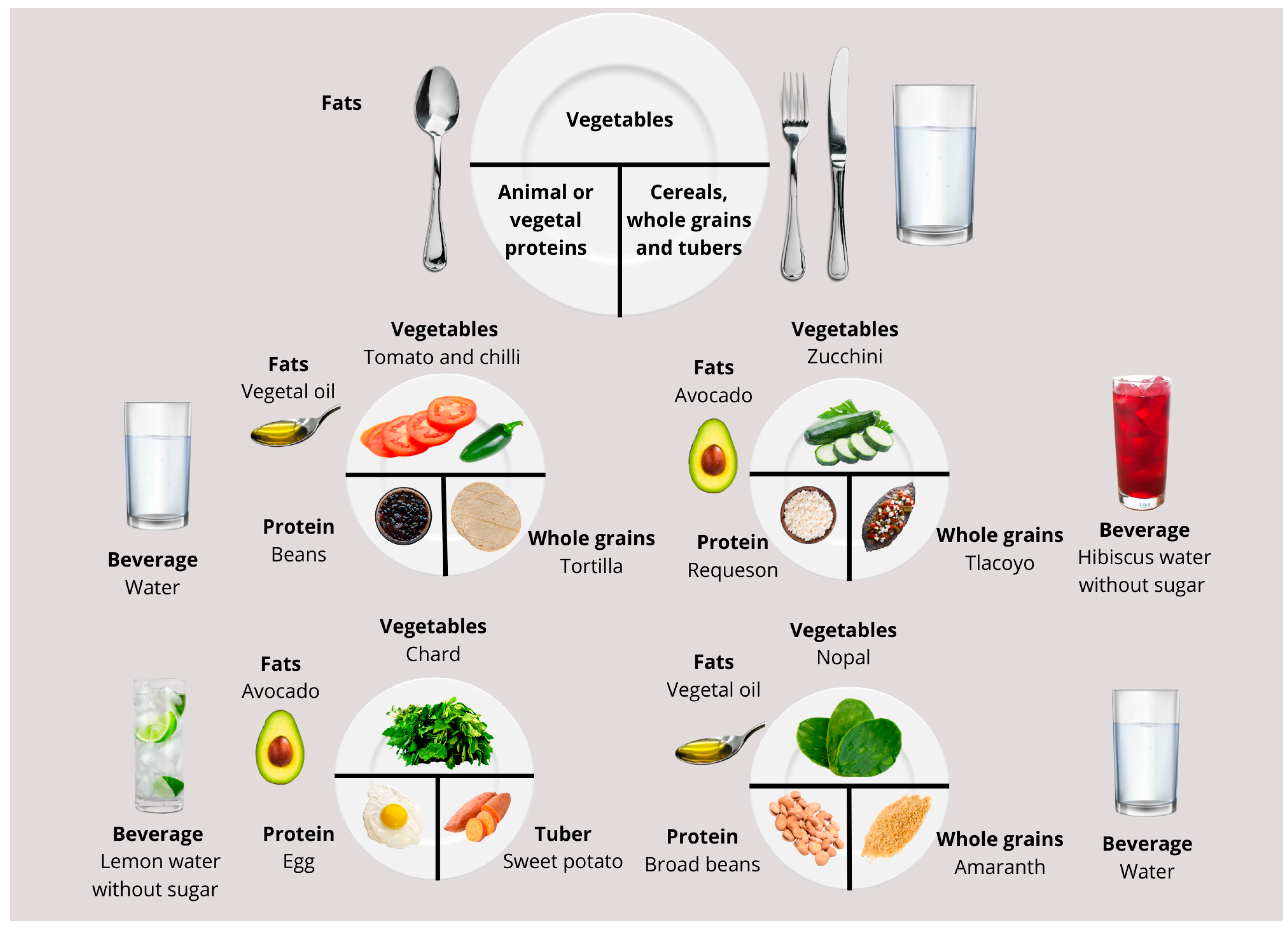

- Secretaría de Salud. Dieta de la Milpa. Modelo de Alimentación Saludable y Culturalmente Pertinente. Fortalecimiento de la Salud con Comida, Ejercicio y Buen Humor. 2020 Jun. Available: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/715861/01_Documento_de_La_dieta_de_la_milpa.pdf.

- Wang L-C, Yu Y-Q, Fang M, Zhan C-G, Pan H-Y, Wu Y-N, et al. Antioxidant and antigenotoxic activity of bioactive extracts from corn tassel. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2014;34: 131–136. [CrossRef]

- Gulcin İ. Antioxidants and antioxidant methods: an updated overview. Arch Toxicol. 2020;94: 651–715. [CrossRef]

- Meza-Rios A, López-Villalobos EF, Anguiano-Sevilla LA, Ruiz-Quezada SL, Velazquez-Juarez G, López-Roa RI, et al. Effects of Foods of Mesoamerican Origin in Adipose Tissue and Liver-Related Metabolism. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59. [CrossRef]

- Gwirtz JA, Garcia-Casal MN. Processing maize flour and corn meal food products. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1312: 66–75. [CrossRef]

- Ghimire A, Wanner C, Tonelli M. Closing CKD Treatment Gaps: Why Practice Guidelines and Better Drug Coverage Are Not Enough. Am J Kidney Dis. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lo Turco V, Potortì AG, Rando R, Ravenda P, Dugo G, Di Bella G. Functional properties and fatty acids profile of different beans varieties. Nat Prod Res. 2016;30: 2243–2248. [CrossRef]

- Ballal K, Wilson CR, Harmancey R, Taegtmeyer H. Obesogenic high fat western diet induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in rat heart. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;344: 221–230. [CrossRef]

- Christ A, Lauterbach M, Latz E. Western Diet and the Immune System: An Inflammatory Connection. Immunity. 2019;51: 794–811. [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez VJ, Beltrán-Velasco AI, Redondo-Flórez L, Martín-Rodríguez A, Tornero-Aguilera JF. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2023;15. [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Gutiérrez A, Sánchez-Pimienta TG, Batis C, Willett W, Rivera JA. Toward a healthy and sustainable diet in Mexico: where are we and how can we move forward? Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113: 1177–1184. [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Salud. Fortalecimiento de la Salud con Comida, Ejercicio y Buen Humor: La Dieta de la Milpa. Modelo de Alimentación Mesoamericana Saludable y Culturalmente Pertinente. 2020.

- Castelnuovo G, Perez-Diaz-del-Campo N, Rosso C, Armandi A, Caviglia GP, Bugianesi E. A Healthful Plant-Based Diet as an Alternative Dietary Approach in the Management of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Nutrients. 2024;16: 2027. [CrossRef]

- Boye J, Wijesinha-Bettoni R, Burlingame B. Protein quality evaluation twenty years after the introduction of the protein digestibility corrected amino acid score method. British Journal of Nutrition. 2012;108: S183–S211. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso BR, Tan SY, Daly RM, Via JD, Georgousopoulou EN, George ES. Intake of Nuts and Seeds Is Associated with a Lower Prevalence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in US Adults: Findings from 2005-2018 NHANES. The Journal of nutrition. 2021;151. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld RM, Juszczak HM, Wong MA. Scoping review of the association of plant-based diet quality with health outcomes. Front Nutr. 2023;10: 1211535. [CrossRef]

- Lv Y, Rong S, Deng Y, Bao W, Xia Y, Chen L. Plant-based diets, genetic predisposition and risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Med. 2023;21: 351. [CrossRef]

- Yuzbashian E, Fernando DN, Pakseresht M, Eurich DT, Chan CB. Dairy product consumption and risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2023;33: 1461–1471. [CrossRef]

- Kaenkumchorn TK, Merritt MA, Lim U, Le Marchand L, Boushey CJ, Shepherd JA, et al. Diet and Liver Adiposity in Older Adults: The Multiethnic Cohort Adiposity Phenotype Study. J Nutr. 2021;151: 3579–3587. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura SM, Duarte SMB, Stefano JT, Mazo DFC, Pinho JRR, Oliveira CP. PNPLA3 GENE POLYMORPHISM AND RED MEAT CONSUMPTION INCREASED FIBROSIS RISK IN NASH BIOPSY-PROVEN PATIENTS UNDER MEDICAL FOLLOW-UP IN A TERTIARY CENTER IN SOUTHWEST BRAZIL. Arquivos de gastroenterologia. 2023;60. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Wang D, Zhou S, Duan H, Guo J, Yan W. Nutritional Composition, Health Benefits, and Application Value of Edible Insects: A Review. Foods. 2022;11: 3961. [CrossRef]

- Quah Y, Tong SR, Bojarska J, Giller K, Tan SA, Ziora ZM, et al. Bioactive Peptide Discovery from Edible Insects for Potential Applications in Human Health and Agriculture. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 2023;28. [CrossRef]

- Scoditti E, Sabatini S, Carli F, Gastaldelli A. Hepatic glucose metabolism in the steatotic liver. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;21: 319–334. [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Diabetes Endocrinology. Redefining obesity: advancing care for better lives. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025;13: 75.

- Mogna-Peláez P, Riezu-Boj JI, Milagro FI, Herrero JI, Elorz M, Benito-Boillos A, et al. Inflammatory markers as diagnostic and precision nutrition tools for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Results from the Fatty Liver in Obesity trial. Clin Nutr. 2024;43: 1770–1781. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Wang S, Wang J, Liu W, Gong H, Zhang Z, et al. Insoluble dietary fiber from soybean residue (okara) exerts anti-obesity effects by promoting hepatic mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. Foods. 2023;12: 2081. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Sun W, Swallah MS, Amin K, Lyu B, Fan H, et al. Preparation and characterization of soybean insoluble dietary fiber and its prebiotic effect on dyslipidemia and hepatic steatosis in high fat-fed C57BL/6J mice. Food Funct. 2021;12: 8760–8773. [CrossRef]

- Dang J, Cai T, Tuo Y, Peng S, Wang J, Gu A, et al. Corn peptides alleviate nonalcoholic fatty liver fibrosis in mice by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and regulating gut Microbiota. J Agric Food Chem. 2024;72: 19378–19394. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Pan X, Zhang S, Wang W, Cai M, Li Y, et al. Protective effect of corn peptides against alcoholic liver injury in men with chronic alcohol consumption: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Lipids Health Dis. 2014;13: 192. [CrossRef]

- Cui H-X, Luo Y, Mao Y-Y, Yuan K, Jin S-H, Zhu X-T, et al. Purified anthocyanins from Zea mays L. cob ameliorates chronic liver injury in mice via modulating of oxidative stress and apoptosis. J Sci Food Agric. 2021;101: 4672–4680. [CrossRef]

- Lee-Martínez SN, Luzardo-Ocampo I, Vergara-Castañeda HA, Vasco-Leal JF, Gaytán-Martínez M, Cuellar-Nuñez ML. Native corn (Zea mays L., cv. “Elotes Occidentales”) polyphenols extract reduced total cholesterol and triglycerides levels, and decreased lipid accumulation in mice fed a high-fat diet. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;180: 117610.

- Lucero López VR, Razzeto GS, Escudero NL, Gimenez MS. Biochemical and molecular study of the influence of Amaranthus hypochondriacus flour on serum and liver lipids in rats treated with ethanol. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2013;68: 396–402. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Fukui R, Jia H, Kato H. Amaranth supplementation improves hepatic lipid dysmetabolism and modulates gut Microbiota in mice fed a high-fat diet. Foods. 2021;10: 1259. [CrossRef]

- Rjeibi I, Ben Saad A, Hfaiedh N. Oxidative damage and hepatotoxicity associated with deltamethrin in rats: The protective effects of Amaranthus spinosus seed extract. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;84: 853–860. [CrossRef]

- Escudero NL, Albarracín GJ, Lucero López RV, Giménez MS. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of flour and protein concentrate of Amaranthus cruentus seeds. J Food Biochem. 2011;35: 1327–1341. [CrossRef]

- Valerino-Perea S, Lara-Castor L, Armstrong MEG, Papadaki A. Definition of the traditional Mexican diet and its role in health: A Systematic review. Nutrients. 2019;11: 2803. [CrossRef]

- Šmíd V, Dvořák K, Šedivý P, Kosek V, Leníček M, Dezortová M, et al. Effect of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Lipid Metabolism in Patients With Metabolic Syndrome and NAFLD. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6: 1336–1349. [CrossRef]

- Li H-Y, Gan R-Y, Shang A, Mao Q-Q, Sun Q-C, Wu D-T, et al. Plant-Based Foods and Their Bioactive Compounds on Fatty Liver Disease: Effects, Mechanisms, and Clinical Application. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021: 6621644. [CrossRef]

- Calder PC. Omega-3 fatty acids and metabolic partitioning of fatty acids within the liver in the context of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2022;25: 248–255. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal A, Rizwana, Tripathi AD, Kumar T, Sharma KP, Patel SKS. Nutritional and Functional New Perspectives and Potential Health Benefits of Quinoa and Chia Seeds. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12. [CrossRef]

- Lee S, Choi Y, Jeong HS, Lee J, Sung J. Effect of different cooking methods on the content of vitamins and true retention in selected vegetables. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2017;27: 333. [CrossRef]

- Aburto TC, Batis C, Pedroza-Tobías A, Pedraza LS, Ramírez-Silva I, Rivera JA. Dietary intake of the Mexican population: comparing food group contribution to recommendations, 2012-2016. Salud Publica Mex. 2022;64: 267–279. [CrossRef]

- Huang X, Gan D, Fan Y, Fu Q, He C, Liu W, et al. The Associations between Healthy Eating Patterns and Risk of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Case-Control Study. Nutrients. 2024;16. [CrossRef]

- Donghia R, Campanella A, Bonfiglio C, Cuccaro F, Tatoli R, Giannelli G. Protective Role of Lycopene in Subjects with Liver Disease: NUTRIHEP Study. Nutrients. 2024;16. [CrossRef]

- Lee D, Chiavaroli L, Ayoub-Charette S, Khan TA, Zurbau A, Au-Yeung F, et al. Important Food Sources of Fructose-Containing Sugars and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. Nutrients. 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Shin MK, Yang SM, Han IS. Capsaicin suppresses liver fat accumulation in high-fat diet-induced NAFLD mice. Animal cells and systems. 2020;24. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Hao L, Yu F, Li N, Deng J, Zhang J, et al. Capsaicin: a spicy way in liver disease. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15: 1451084. [CrossRef]

- Sun M, Gu Y, Glisan SL, Lambert JD. Dietary cocoa ameliorates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and increases markers of antioxidant response and mitochondrial biogenesis in high fat-fed mice. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry. 2021;92. [CrossRef]

- Rebollo-Hernanz M, Aguilera Y, Martin-Cabrejas MA, de Mejia E G. Phytochemicals from the Cocoa Shell Modulate Mitochondrial Function, Lipid and Glucose Metabolism in Hepatocytes via Activation of FGF21/ERK, AKT, and mTOR Pathways. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland). 2022;11. [CrossRef]

- Askari F, Rashidkhani B, Hekmatdoost A. Cinnamon may have therapeutic benefits on lipid profile, liver enzymes, insulin resistance, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Nutr Res. 2014;34: 143–148. [CrossRef]

- Mackonochie M, Rodriguez-Mateos A, Mills S, Rolfe V. A Scoping Review of the Clinical Evidence for the Health Benefits of Culinary Doses of Herbs and Spices for the Prevention and Treatment of Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients. 2023;15. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian K, Fakhar F, Keramat S, Stanek A. The role of antioxidants in the treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: A systematic review. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024;13: 797. [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Uscanga A, Loarca-Piña G, Gonzalez de Mejia E. Baked corn (Zea mays L.) and bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) snack consumption lowered serum lipids and differentiated liver gene expression in C57BL/6 mice fed a high-fat diet by inhibiting PPARγ and SREBF2. J Nutr Biochem. 2017;50: 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Hussain A, Kausar T, Jamil MA, Noreen S, Iftikhar K, Rafique A, et al. Role of Pumpkin Parts as Pharma-Foods: Antihyperglycemic and Antihyperlipidemic Activities of Pumpkin Peel, Flesh, and Seed Powders, in Alloxan-Induced Diabetic Rats. Int J Food Sci. 2022;2022: 4804408. [CrossRef]

- Langmann F, Ibsen DB, Johnston LW, Perez-Cornago A, Dahm CC. Legumes as a Substitute for Red and Processed Meat, Poultry or Fish, and the Risk of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in a Large Cohort. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2025;38: e70004. [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe P, Jayawardana R, Galappaththy P, Constantine GR, de Vas Gunawardana N, Katulanda P. Efficacy and safety of “true” cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) as a pharmaceutical agent in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2012;29: 1480–1492. [CrossRef]

- Bandara T, Uluwaduge I, Jansz ER. Bioactivity of cinnamon with special emphasis on diabetes mellitus: a review. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2012;63: 380–386. [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe P, Pigera S, Premakumara GAS, Galappaththy P, Constantine GR, Katulanda P. Medicinal properties of “true” cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum): a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13: 275. [CrossRef]

- Eidi A, Mortazavi P, Bazargan M, Zaringhalam J. Hepatoprotective activity of cinnamon ethanolic extract against CCI4-induced liver injury in rats. EXCLI J. 2012;11: 495–507. [CrossRef]

- Morán-Ramos S, Avila-Nava A, Tovar AR, Pedraza-Chaverri J, López-Romero P, Torres N. Opuntia ficus indica (nopal) attenuates hepatic steatosis and oxidative stress in obese Zucker (fa/fa) rats. J Nutr. 2012;142: 1956–1963. [CrossRef]

- Bahrami A, Teymoori F, Eslamparast T, Sohrab G, Hejazi E, Poustchi H, et al. Legume intake and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2019;38: 55–60. [CrossRef]

| Aspect | Milpa Dieta | Western Diet |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | The traditions of Mesoamerica are based on the millenial agricultural system. | Predominant in industrialized countries, characterized by consuming processed and ultra-processed foods. |

| Characteristic foods | Corn, beans, squash, chili, chili, quelites, tomato, amaranth, ricotta cheese. | Red meats, ultra-processed products, refined flours, added sugars, full-fat dairy products. |

| Main source of proteins | Legumes (beans), insects, ricotta cheese and lean meats | Red meats, sausages, full-fat dairy products and animal proteins |

| Predominant carbohydrates | Nixtamalized corn and amaranth | Refined flours and added sugars |

| Fats | Predominantly unsaturated (seeds, avocado, zucchini, sunflower oil). | High in trans and saturated fats |

| Fiber | High in fiber (whole grains, vegetables, pulses). | Low in fiber (diets high in processed and refined foods). |

| Caloric density | Moderate, based on natural and minimally processed ingredients. | High, with rich calorie load from fats and sugars. |

| Health impact | Promotes cardiovascular health, prevents metabolic diseases by reducing adipose tissue at the central level. | Linked to obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease. |

| Sustainability | Environmentally friendly, based on local production and polycultures. | High environmental impact due to meat consumption and intensive monoculture. |

| Food processing | Minimal, fresh and natural food. | High, with additives, preservatives and excess sodium. |

| Food group | Components |

|---|---|

| Whole grains and tubers | Corn, amaranth, oats, sweet potato, cassava, chayotextle, or chinchayote. |

| Vegetables | Nopales, quelites, quintoniles, purslane, green beans, romeritos, huauzontle, tomato, citlali tomato, tomatillo, miltomate, chili peppers, bell peppers, squash, chayote, mushroom, chilacayote, colorines, izote flower, jicama, watercress, chaya, huitlacoche, achiote, epazote, vanilla, acuyo, mushrooms, and allspice, among others. |

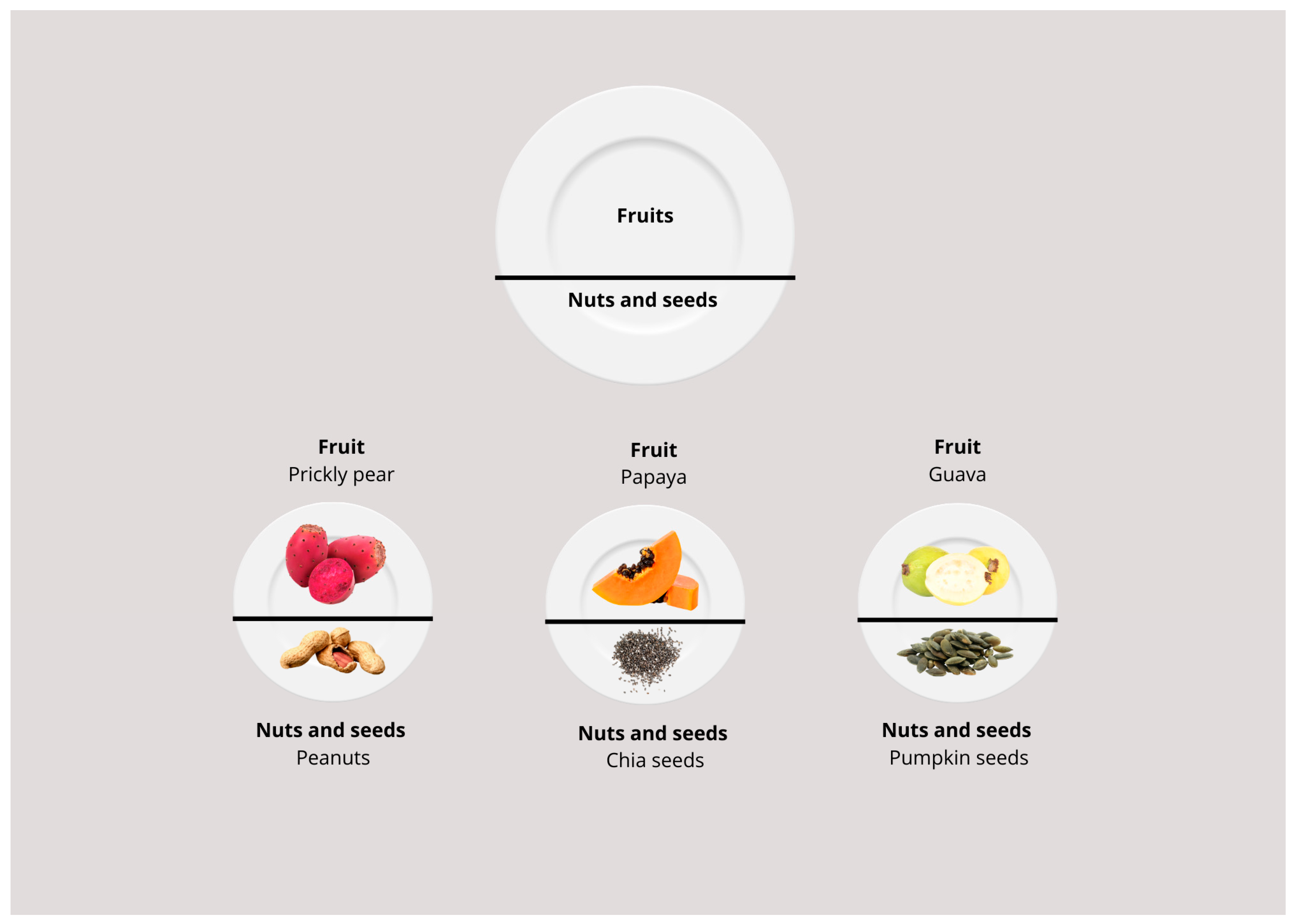

| Legumes, seeds, and oilseeds | Beans, fava beans, chia seeds, chocolate, peanuts, pumpkin seeds |

| Fruits | Soursop, prickly pear, papaya, black zapote, chicozapote, mamey, guava, tejocote, capulín, pineapple, anona, xoconostle, cherimoya, nance, berries, yellow plum, and pitahaya. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).