1. Introduction

Tissue engineering has contributed to the advancement of research in dentistry. One of the main objectives of this continuous search in dentistry is the identification of a “biocompatible” tissue substitute that does not contain any toxic species, damaging to host tissue or promoting inflammation [

1], but does promote integration and regeneration of host tissues through cellular migration, vascularization, and restoration of normal gingival tissues [

2]. Biocompatible biomaterials should help, not interfere, in the surgical wound healing process, and achieve satisfactory aesthetic outcomes at least equivalent to autogenous grafts [

3].

In periodontal surgeries, the subepithelial connective tissue graft (SCTG) is described in the literature as the gold standard [

4], but this term implies a well-defined, consistent standard for the harvesting procedure. Yet, harvesting SCTG is associated with the risk of postoperative complications at the donor site such as pain, palatal bleeding, and gingival necrosis [

5]. Additionally, the amount and quality of the graft are patient dependent and could be limited. [

6]

To avoid these limitations, numerous matrices are available on the market intended to replace or complement SCTG. The acellular dermal matrix (ADM) has been used for many decades not only in periodontal procedure, but to treat burn wounds, facial and breast reconstructions [

7]. ADM is routinely used for root coverage procedures and soft tissue augmentation at teeth or implant sites [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Human tissue samples taken after the ADM grafting at regular time intervals, demonstrated normal wound healing with complete integration of the graft by the host gingival tissue without adverse complications [

14].

As an alternative to ADM, porcine acellular dermal matrices (PADM) are developed using proprietary manufacturing processes that do not damage the elastin nor the extracellular collagen of the matrix, providing a suitable density for cells, micro vessels, and soft-tissue growth. Although the rapid degradation by the enzymatic action of collagenase has been described as the greatest demerit of native collagen [

15,

16], a in vivo study reported that cross-linking of the collagen fibers can extend the resorption time of biomaterials with substantial differences regarding biodegradation, biocompatibility and angiogenesis [

17]. To clarify, a biomechanical study [

18] described the PADM as a densely packed type I collagen fibers in great abundance, with a higher tensile strength compared to autogenous grafts. These findings suggest a long-term resistance of the substitute during the healing process, which conflicts with the general idea about the demerit of soft tissue substitutes.

One of the aspects described in the literature about PADM is the effects of foreign body reaction (FBR) during integration with the surrounding tissues. FBR is an unavoidable process which takes place whenever a material is implanted into the body and its stages represent significant challenges to a material integrity and its therapeutic function [

19]. It is therefore crucial to understand and deepen the experimental studies related to this process to elucidate the stages and processes of the incorporation of different matrices created and introduced to the market, and the consequences of their use in clinical practice in a safe and predictable way.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to verify, through histological analyses, the biocompatibility of PADM through tissue reaction resulting from subcutaneous implantation in rats over time.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Size Calculation

Animal selection, management, and surgery protocol of this quasi-experiment were approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation at the School of Dentistry of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, FORP/USP (process no. 2019.1.664.58.8). The ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In vivo Experiments) guidelines were followed by the authors [

20]. The animals were divided into four groups (7, 14, 21 and 28 days), including six rats in each. The sample size was based on previous studies with similar methodology [

17,

21]. Twenty-four male Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus albinus) weighing 350 g (Central Animal Facility, FORP/USP) were fed a selected solid diet and received water ad libitum over a 12-h light/dark cycle at temperatures between 22 and 24°C.

2.2. Surgical Procedure

After the first 2 weeks of acclimatization, the animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 9 mg/kg ketamine 10% and 5 mg/kg xylazine 2%. The back of each rat was depilated using an electric shaver. Following disinfection with polyvidone iodine, a skin incision of 8 mm was made right paramedian along the vertebral column followed by the separation of two subcutaneous pouches. One porcine acellular dermal matrix (NovoMatrix – BioHorizons - Ontário, Canadá) (5mmx5mm size and 1.5mm height) was implanted subcutaneously on the right and left sides along the dorsal midline of each mouse. The membranes were allocated in the resulting 12 pouches. Primary wound closure was achieved using 4 simple sutures with 5-0 nylon material (

Figure 1).

2.3. Postoperative Healing

Postoperative healing occurred with one intercurrence, in which one animal from group 7days and another from group 21days had wound dehiscence. No other complications, including infection, bleeding, or allergic reactions, were observed.

2.4. Tissue Sampling and Histology

At 7, 14, 21 and 28 days after matrix grafting, the animals were anesthetized and euthanized in a carbon dioxide chamber. The specimens were removed with the surrounding connective tissue and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. From each specimen, five histological slides were obtained from 4 m longitudinal sections. The slides were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) to evaluate the fibrous capsule thickness, cell ingrowth, cell ingrowth density and giant cells count. Picrosirius stain was performed to evaluate collagen fiber density [

22]. Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) stain was performed for macrophages identification [

23] and immunohistochemical vimentin staining for the detection of connective tissue cells, particularly fibroblasts and giant cells [

24,

25]. Longitudinal histological sections from each animal were analyzed on a Leica DM LB2 microscope outfitted with a Leica DFC310FX digital camera (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). One single examiner (M.B.L.R.) with no knowledge of the experimental groups analyzed all the images through the LAS v. 4.1 in a x20 magnification lens.

Linear measurements were performed for fibrous capsule thickness and cell ingrowth, which was determined by the distance between the innermost cell and the outermost collagen fiber of the matrix. Macrophages and giant cells were counted along a 0.4 mm section of the matrix-host tissue interface and were confirmed by TRAP or vimentin-stained sections. (

Figure 2).

Cell ingrowth density measurements were performed in region of interest (ROI), in which a square was positioned tangentially to the graft-capsule interface. Cell invasion density was measured within the graft in a 0.1mm2 area (

Figure 3).

Collagen fiber density was measured by polarized light microscopy on slides stained with Picrosirius. Two ROI areas of 0.6 mm2 each were positioned tangentially to the graft-capsule interface to measure the density of the fibers in the graft and in the fibrous capsule of the host (

Figure 4). The ratio (graft/host) between the means of these measurements was used for statistical analysis.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses for mean, median and standard deviation values were calculated for all the parameters evaluated. Kruskal-Wallis and post hoc Dunn's multiple comparisons testing were used for comparisons within groups. A confidence level of 95% was adopted. Prism 8 for macOS, version 8.2.1(279) (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was the statistical software used for the analyses. Results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Histological Analysis

A non-implanted porcine acellular dermal matrix was processed to evaluate the matrix structure prior to the implantation in vivo and revealed a dense network of collagen fibers showing diverse orientations, and no signs of remaining cells (

Figure 5).

In the period of seven days following implantation, the matrix did not present any difference regarding its structure and, thus, the collagen fibers remained unaltered at this time (

Figure 6A,B). Vimentin-positive mononucleated cells were intermingled with some collagen fibers in the outermost part of the matrix (

Figure 7A). A fibrous capsule formation was observed adjacently to the outer surface of the graft, showing collagen fibers from the host running parallel to the graft surface and a weak inflammatory reaction, characterized by neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages.

At 14 days post-grafting (

Figure 6C), it is possible to visualize an enhanced cell infiltration into the matrix (

Figure 7B–D) and the formation of few new vessels on its periphery, where multinucleated giant cells – vimentin-positive and TRAP-stained – attached directly to the collagen fibers of the matrix (

Figure 7C,D). At least part of the vimentin-positive mononucleated cells were also stained for TRAP (

Figure 7D). The boundaries of the matrix begin to be intermingled with tissue elements of the adjacent host tissue, in the context of a stronger inflammatory infiltrate (

Figure 6B and

Figure 7D).

At 21 days post-grafting (

Figure 6E), the enhancement of the cell infiltration is clear, and the multinucleated giant cells are located in areas of concave contour of the graft-host tissue interface (

Figure 6F and

Figure 7E). The boundaries of the graft are no longer well defined due to a more intense inflammatory response and an initial collagen deposition on the partially resorbed graft collagen fibers, which integrate host tissue and graft. Blood vessels ingrowth from the surrounding connective tissues can also be occasionally detected.

At 28 days post-grafting (

Figure 6G), there is still volume preservation of the matrix, cellular invasion to its innermost part, and the formation of new vessels on its outermost part (

Figure 7F). The graft-host tissue interface is now less clear due to the deposition of new collagen fibers in direct contact with graft collagen fibers and predominantly perpendicular to the fibrous capsule. In addition, the inflammatory process is minimal, and multinucleated giant cells are only occasionally observed (

Figure 6H and

Figure 7F).

3.2. Histomorphometrical Analysis

For the histomorphometrical analysis, the histological sections were evaluated over time in terms of fibrous capsule thickness, cell ingrowth, cell ingrowth density and giant cells count. Linear measurements were performed for fibrous capsule thickness and cell ingrowth. Giant cells were counted in an extension of 0.4 mm and confirmed by subsequently TRAP and vimentin-stained sections. All the parameter data are represented in boxplots due to their non-parametric characteristics (

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

For the cell ingrowth evaluation, there was an increase in cellular ingrowth inside the graft over time. Statistical differences were noted when comparing cell ingrowth length among time points, specifically between 7 and 14 days, 7 and 21 days, and 7 and 28 days (

Figure 8A).

For the cell ingrowth density in a ROI of 0.1mm

2 from the outermost part of the graft, there was a statistically different increase in cell ingrowth density over time, with statistical differences between 7 and 21 days, 7 and 28 days, and 14 and 21 days (

Figure 8B).

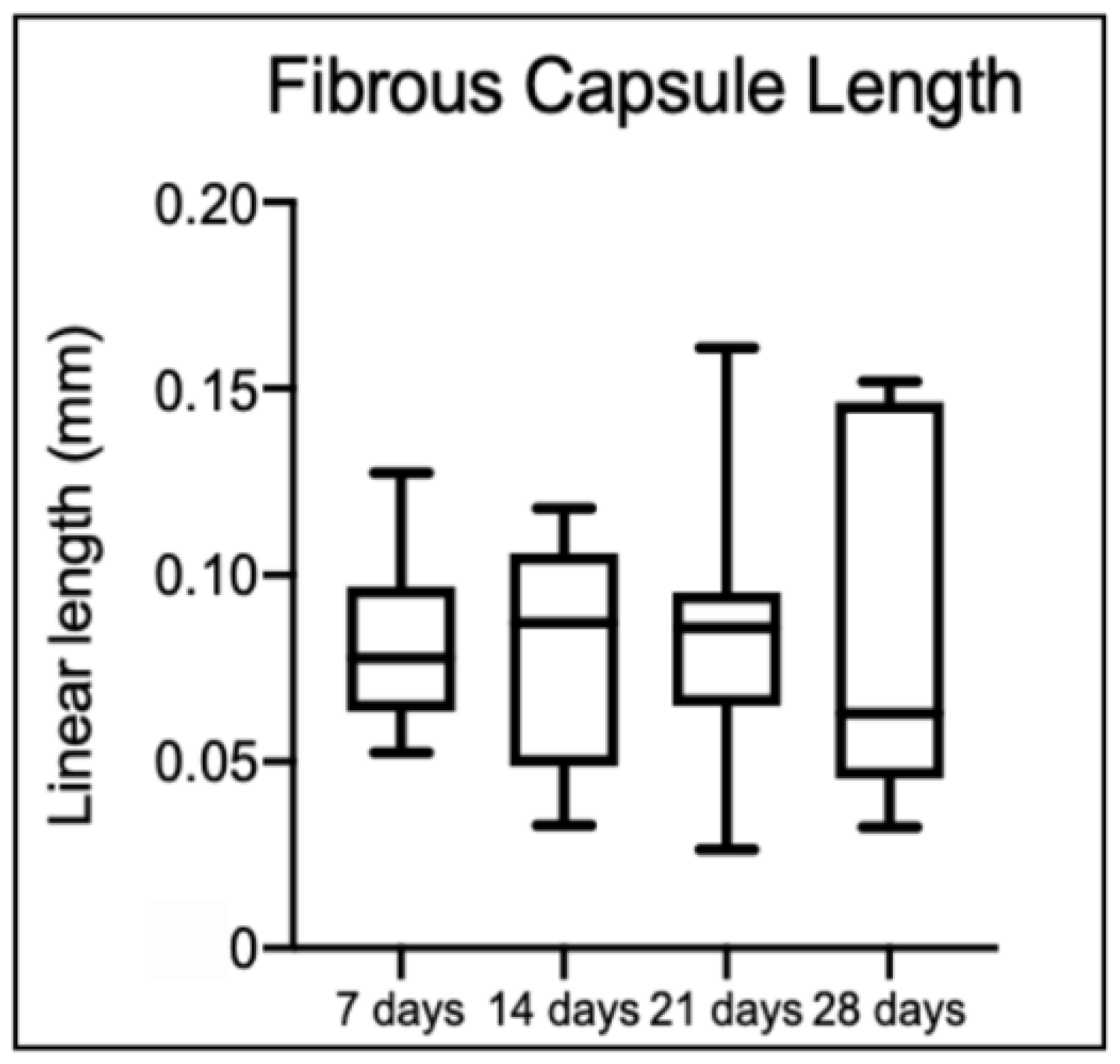

Regarding the fibrous capsule length, there were no statistical differences among time points (

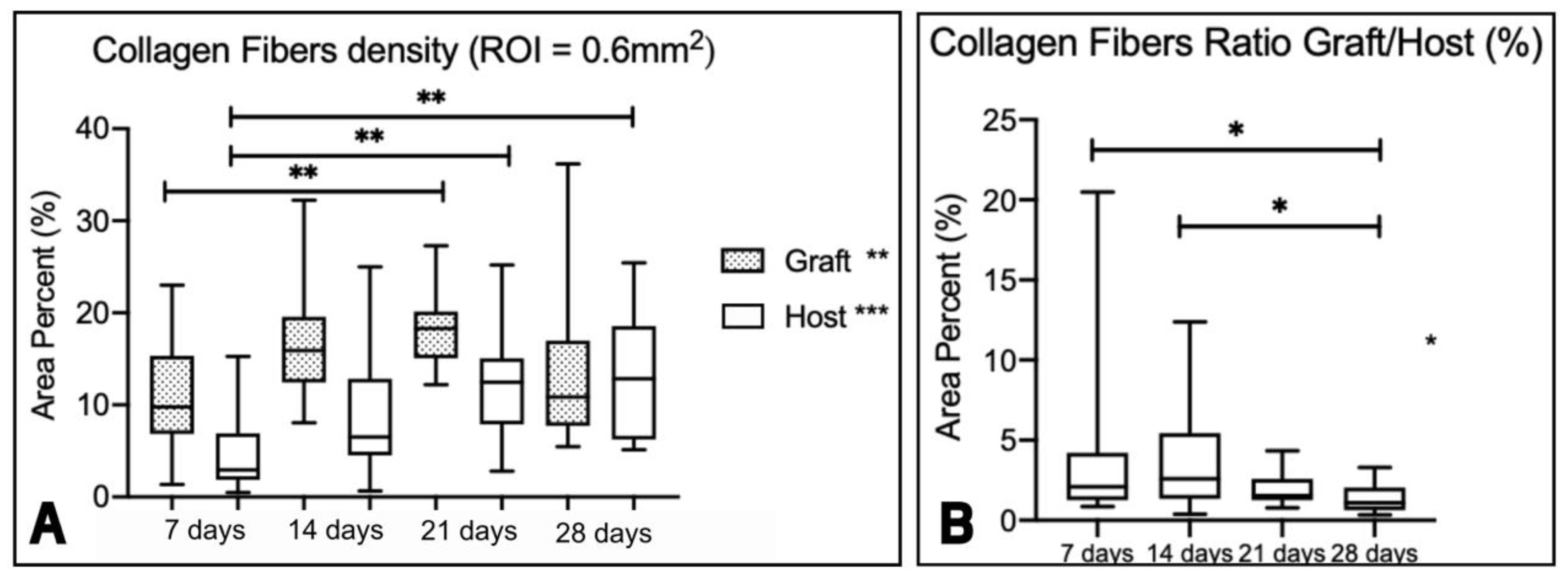

Figure 9). However, the collagen fiber density of the graft (

Figure 10A) changed over time, particularly between 7 and 21 days. For the host, statistical differences over time are also observed, particularly between 7 and 21 days, and 7 and 28 days. The ratio graft/host values also changed over time (

p < 0.001), particularly between 7 and 28 days, and 14 and 28 days (

Figure 10B).

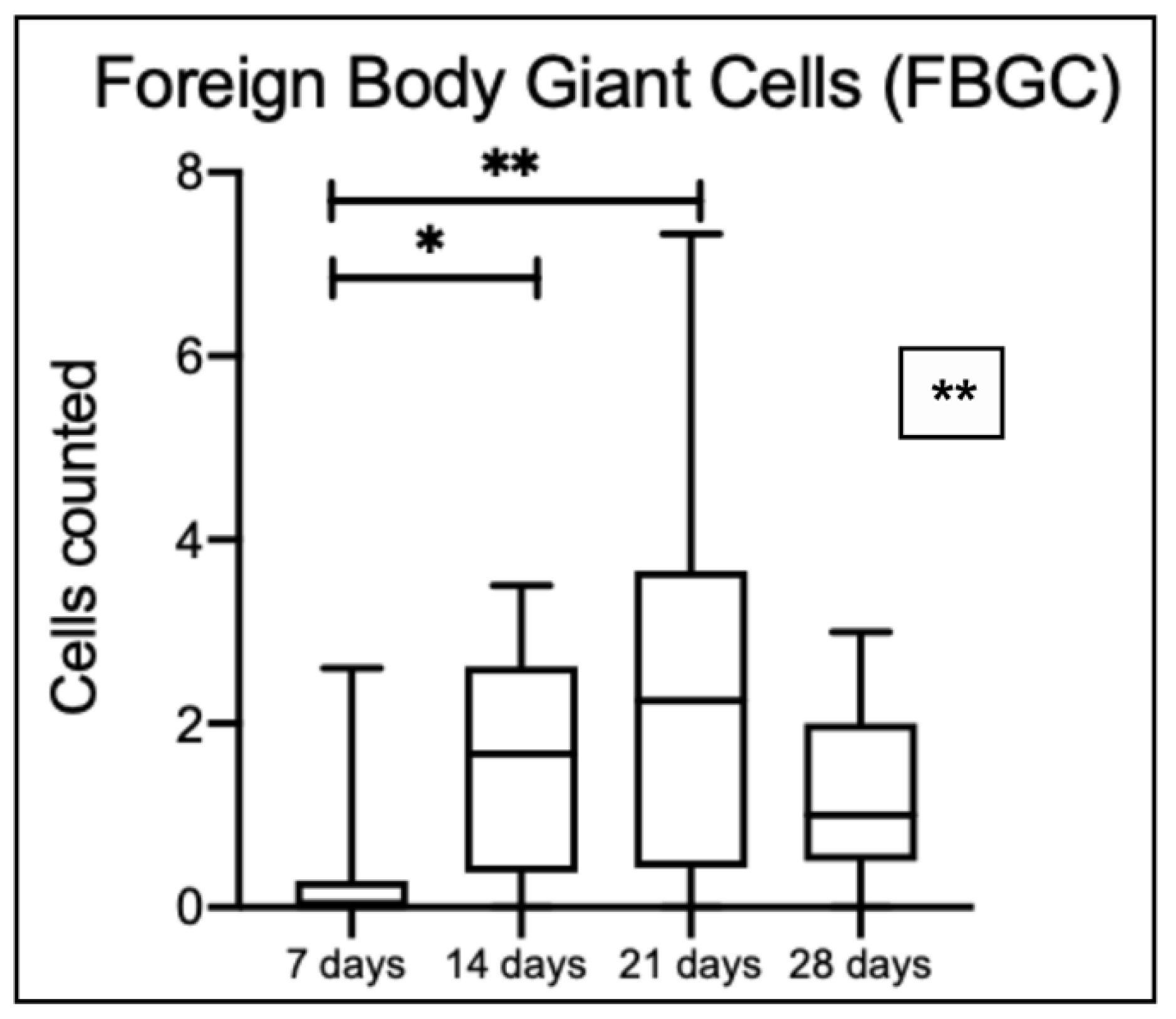

The number of FBGC increased over time until the 21 days (

Figure 11). A statistically significant difference is observed among time points, specifically between 7 and 14 days, and 7 and 21 days; cell number decreased at 28 days.

4. Discussion

In the present animal study, we examined biocompatibility, foreign body reaction and tissue integration of a porcine acellular dermal matrix evaluated in a subcutaneous rat model. The histological aspects observed in this study describe a process of host tissue integration of the matrix. The fibrous capsule thickness, cell ingrowth, cell density ingrowth, foreign body giant cells count and collagen fiber density over time were analyzed at 7, 14, 21 and 28 days after the subcutaneous matrix implantation. These analyses take part in a natural, healthy, and expected process of wound healing. Phases belonging to the wound healing process include vascular response, inflammatory response, proliferation and maturation or remodeling, with a considerable overlap between these phases [

26].

Although the quantification of vessels was not performed in this study, it was possible to observe and describe the presence of blood vessels in the fibrous capsule/periphery of the matrix at 14 days, and at the 28th day, in which vessels were already visible intermingled with the collagen fibers of the matrix. This finding suggests that an angiogenesis process occurs inside the matrix over time, which makes the matrix integration process favorable. In line with our work, Wong et al. [

27] evaluated the revascularization of human ADM in a rat model and observed that after 7 days CD31+ endothelial cells have infiltrated the matrix. In the same study, at 14 days mature CD31+ microvessels were present throughout the matrix. Vascularization 2 weeks following implantation was demonstrated in similar collagen I/III materials by Schwarz et al. [

28]. Conversely, in a minipig study, a subcutaneous implantation of another ADM was performed, and the authors observed mature microvessels in the periphery of the implanted graft at 1 month evaluation [

29]. As described by Gaahnati et al. [

30], the studied matrix did not become vascularized until some point between days 30 and 60.

The inflammatory response is a complex and essential homeostatic process to extrinsic and intrinsic tissue damage. Immune cells are recruited to vascularized tissues to eliminate the source of cell injury and prepare for tissue regeneration [

2]. With the performed cell ingrowth and cell ingrowth density analysis within a ROI, we can observe that the matrix allows cell ingrowth over time. The presence of the inflammatory process characterized by neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages in the capsule at 7 days and decreasing at 14 and 21 days, contributes to the matrix integration process. However, over time, it was possible to observe the advance of cells -not necessarily inflammatory- permeated by collagen fibers inside the graft. The cell ingrowth density analysis that shows an increase in density over time characterizes the following proliferation and maturation phase. Despite several methodological differences and distinct methods for data interpretation, many studies associate cell ingrowth with the safety of the matrix in vivo, and density of collagen fibers, matrix surface and porosity with the speed of the integration process [

3,

14,

17,

18,

21,

30,

31]

The transition from the inflammatory to the proliferative phase has a major player which is the macrophages. Moreover, depletion studies demonstrated that the absence of macrophages in the inflammatory or proliferation phase of wound healing resulted in decreased tissue formation or even hemorrhage [

26]. Multi-nucleated giant cells are cell-type derived from the fusion of monocytes/macrophages [

19] and many biological aspects of their behavior have been discovered from biomaterials implanted in soft tissues including specific intercellular and intracellular signaling pathways, such as inducing fibroblasts proliferation [

32]. The FBGC were counted in this study and confirmed by subsequent vimentin labeling and TRAP staining sections. In the macrophage, TRAP is essential for the normal production and processing of collagen (type I) [

22,

23] and vimentin is secreted in response to pro-inflammatory signaling pathways and it is probably involved in immune function [

24] which suggests the reason why the vimentin-positive FBGC is observed adherent to the collagen fibers at 14 and 21 days. Also, the decrease in the acute inflammatory process in this study is concomitant with a drop in FBGC count. According to Chamberlain et al. [

33], all macrophages, regardless of cell origin or culture surface, shift toward the M2 phenotype, a pro-healing type of macrophage, similar to their known shift to an M2 polarization in vivo during the foreign-body response. This description corroborates the rationality of this work, which is based on the contribution of the foreign body reaction process to the integration of the matrix to the host tissue, as found in other studies that addressed different methodologies, but with the interpretation adjusted to each of them [

17,

21,

34,

35].

An adequate host tissue integration is mandatory for the long-term success of graft implantation procedures. A higher collagen density can be a reason for slower biodegradation and cell ingrowth [

21]. Although the studied matrix has a densely packed collagen structure as observed in the collagen density analysis, the delay in the process of cell ingrowth may have allowed for the remodeling of the collagen fibers over time. As shown in this work, the density in the collagen fiber of the graft decreases particularly between 7 and 21 days, when the inflammatory process is still in high activity. In the host, where the fibrous capsule was clearly delimited and less dense at 7 days, it was possible to observe an increase in density without clear delimitation of the beginning and end of the graft versus the capsule. These findings suggest that the degradation process happened over time and new collagen and elastin fibers were deposited as described in other studies with the same matrix [

18,

31], and with human ADM [

3,

14,

29].

Therefore, different studies have been published over the years to better understand the process of integration of collagen matrices to replace connective tissues. Methodologies do not always report different analyses performed at varying experimental times in diverse animal or human models [

14]. These methodological discrepancies make it difficult to compare results, but it elucidates the integration process in each of them. In this work, for example, we understand the limitation of the experimental time evaluated, as well as the analyses performed. It is possible that in longer follow-up periods we could observe the process of full integration of the matrix into the tissues as previously described in the literature, and the failures thereof. Also, characterization of cell invasion, as the shift from the inflammatory to remodeling phase are important subjects to study further in this experimental model.

For an implanted material to be considered biocompatible, in vivo analyses must fulfill two requirements described by Crawford et al. [

2]: 1) little or no biological reaction from extractable components and 2) a thin, fibrous capsule (typically in the range 50-200 microns in thickness) with little evidence of acute on-going inflammatory reaction after one month of implantation in soft tissue. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that the porcine acellular dermal matrix was proven to be biocompatible tissue substitute in rats.

5. Conclusions

Within their limits, the findings of this study support the biocompatibility of porcine acellular dermal matrix as tissue substitute, allowing tissue integration through cell ingrowth and proliferation, degradation of the collagen matrix through FBGC activity and deposition of new collagen over the time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.L.R. and A.B.N.J.; Data curation, B.F.M.M. and B.d.B.B.; Formal analysis, M.B.L.R., B.F.M.M. and B.d.B.B.; Funding acquisition, A.B.N.J.; Investigation, B.F.M.M. and B.d.B.B.; Methodology, M.B.L.R.; Resources, L.A.B.d.S. and A.B.N.J.; Supervision, L.A.B.d.S.; Validation, P.T.d.O.; Writing – original draft, M.B.L.R.; Writing – review & editing, P.T.d.O. and A.B.N.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation at the School of Dentistry of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, FORP/USP (process no. 2019.1.664.58.8). The ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In vivo Experiments) guidelines were followed by the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marco Antonio dos Santos, Nilza Maria and Adriana Luisa Gonçalves de Almeida for their technical assistance during the execution of the study. The analysis was performed at the Multi-users 3Dbio-lab supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP). The matrices were donated by Biohorizons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

SCTG

ADM |

Subepithelial connective tissue graft

Acellular dermal matrix |

| PADM |

Porcine acellular dermal matrix |

| FBR |

Foreign body reaction |

| H&E |

Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| TRAP |

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase |

| ROI |

Region of interest |

| FBGC |

Foreign body giant cells |

References

- Williams, D.F. On the mechanisms of biocompatibility. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2941–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, L.; Wyatt, M.; Bryers, J.; Ratner, B. Biocompatibility Evolves: Phenomenology to Toxicology to Regeneration. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2021, 10, e2002153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novaes, A.B.; Marchesan, J.T.; Macedo, G.O.; Palioto, D.B. Effect of In Vitro Gingival Fibroblast Seeding on the In Vivo Incorporation of Acellular Dermal Matrix Allografts in Dogs. J. Periodontol. 2007, 78, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambrone, L.; Botelho, J.; Machado, V.; Mascarenhas, P.; Mendes, J.J.; Avila-Ortiz, G. Does the subepithelial connective tissue graft in conjunction with a coronally advanced flap remain as the gold standard therapy for the treatment of single gingival recession defects? A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Periodontol. 2022, 93, 1336–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoma, D.S.; Benić, G.I.; Zwahlen, M.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Jung, R.E. A systematic review assessing soft tissue augmentation techniques. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2009, 20 (Suppl. S4), 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhr, O.; Bäumer, D.; Hürzeler, M. The addition of soft tissue replacement grafts in plastic periodontal and implant surgery: critical elements in design and execution. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, S123–S142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novaes, A.B., Jr; Palioto, D.B. Experimental and clinical studies on plastic periodontal procedures. Periodontol 2000 2019, 79, 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.J. A comparative study of root coverage obtained with an acellular dermal matrix versus a connective tissue graft: results of 107 recession defects in 50 consecutively treated patients. . 2000, 20, 51–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, P.; Laurell, L.; Geivelis, M.; Lingen, M.W.; Maddalozzo, D. Acellular Dermal Matrix Allografts to Achieve Increased Attached Gingiva. Part 1. A Clinical Study. J. Periodontol. 2000, 71, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, E.L. Jr.; Batista, F.C.; Novaes, A.B. Jr. Management of soft tissue ridge deformities with acellular dermal matrix. Clinical approach and outcome after 6 months of treatment. J Periodontol 2001;72: 265-273.

- Novaes, A.B. Jr.; Pontes, C.C; Souza, S.L; Grisi, M.F.; Taba, M. Jr. The use of acellular dermal matrix allograft for the elimination of gingival melanin pigmentation: Case presentation with 2 years of follow-up. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent 2002;14:619-623.

- Novaes, A.B. Jr. , Grisi, D.C., Molina, G.O., Souza, S.L., Taba, M. Jr., Grisi, M.F. Comparative 6-month clinical study of a subepithelial connective tissue graft and acellular dermal matrix graft for the treatment of gingival recession. J Periodontol 2001;72:1477-1484.

- Reis, M.B.L.; Mandetta, C.d.M.R.; Dantas, C.D.F.; Marañón-Vásquez, G.; Jr, M.T.; de Souza, S.L.S.; Messora, M.R.; Bulle, D.B.P.; Jr, A.B.N. Root coverage of gingival recessions with non-carious cervical lesions: a controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 4583–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, A.; Barros, R.R.; Iezzi, G.; Piattelli, A.; Novaes, A.B., Jr. Acellular Dermal Matrix Graft for Gingival Augmentation: A Preliminary Clinical, Histologic, and Ultrastructural Evaluation. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatakis, D.N.; Promsudthi, A.; Wikesjö, U.M.E. Devices for periodontal regeneration. Periodontology 2000 1999, 19, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pabst, A.M.; Happe, A.; Callaway, A.; Ziebart, T.; Stratul, S.I.; Ackermann, M.; Konerding, M.A.; Willershausen, B.; Kasaj, A. In vitro and in vivo characterization of porcine acellular dermal matrix for gingival augmentation procedures. J. Periodontal Res. 2014, 49, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothamel, D.; Schwarz, F.; Sager, M.; Herten, M.; Sculean, A.; Becker, J. Biodegradation of differently cross-linked collagen membranes: an experimental study in the rat. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2005, 16, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabst, A.; Sagheb, K.; Blatt, S.; Sagheb, K.; Schröger, S.; Wentaschek, S.; Schumann, S. Biomechanical Characterization of a New Acellular Dermal Matrix for Oral Soft Tissue Regeneration. J. Investig. Surg. 2022, 35, 1296–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, R. J, Bosshardt, D.D. Multinucleated Giant Cells: Good Guys or Bad Guys? Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2018, 24, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percie du Sert, N; Hurst, V; Ahluwalia, A; Alam, S; Avey, M. T; Baker, M; Browne, W.J; Clark, A; Cuthill, I.C; Dirnagl, U; Emerson, M; Garner, P; Holgate, S.T; Howells, D.W; Karp, N.A; Lazic, S.E; Lidster, K; MacCallum, C.J; Macleod, M; Pearl, E.J, Petersen, O.H; Rawle, F; Reynolds, P; Rooney, K; Sena, E.S; Silberberg, S.D; Steckler, T; Würbel, H. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar]

- Rothamel, D.; Benner, M.; Fienitz, T.; Happe, A.; Kreppel, M.; Nickenig, H.-J.; E Zöller, J. Biodegradation pattern and tissue integration of native and cross-linked porcine collagen soft tissue augmentation matrices – an experimental study in the rat. Head Face Med. 2014, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattouf, R; Younes, R; Lutomski, D; et al. Picrosirius red staining: a useful tool to appraise collagen networks in normal and pathological tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2014, 62, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayman, A.R. Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) and the osteoclast/immune cell dichotomy. Autoimmunity 2008, 41, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor-Vaknin, N.; Punturieri, A.; Sitwala, K.; Markovitz, D.M. Vimentin is secreted by activated macrophages. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003, 5, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saika, S.; Ohmi, S.; Kanagawa, R.; Tanaka, S.-I.; Ohnishi, Y.; Yamanaka, A.; Hiraoka, J.-I. Immunolocalization of Vimentin in Macrophage-derived Giant Cells. Method for Obtaining Larger Giant Cells. Acta Histochem. ET Cytochem. 1995, 28, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorg, H.; Sorg, C.G. Skin Wound Healing: Of Players, Patterns, and Processes. Eur. Surg. Res. 2023, 64, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.K.; Schonmeyer, B.H.; Singh, P.; Carlson, D.L.; Li, S.; Mehrara, B.J. Histologic Analysis of Angiogenesis and Lymphangiogenesis in Acellular Human Dermis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2008, 121, 1144–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, F.; Rothamel, D.; Herten, M.; Sager, M.; Becker, J. Angiogenesis pattern of native and cross-linked collagen membranes: an immunohistochemical study in the rat. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2006, 17, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.G.; Lee, W.J. Characterization and tissue incorporation of cross-linked human acellular dermal matrix. Biomaterials 2015, 44, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanaati, S.; Schlee, M.; Webber, M.J.; Willershausen, I.; Barbeck, M.; Balic, E.; Görlach, C.; I Stupp, S.; A Sader, R.; Kirkpatrick, C.J. Evaluation of the tissue reaction to a new bilayered collagen matrix in vivo and its translation to the clinic. Biomed. Mater. 2011, 6, 015010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Amo, F.S.-L.; Rodriguez, J.C.; Asa'Ad, F.; Wang, H.-L. Comparison of two soft tissue substitutes for the treatment of gingival recession defects: an animal histological study. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2019, 27, e20180584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diegelmann, R.F.; Cohen, I.K.; Kaplan, A.M. The Role of Macrophages in Wound Repair. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1981, 68, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, L.M.; Holt-Casper, D.; Gonzalez-Juarrero, M.; Grainger, D.W. Extended culture of macrophages from different sources and maturation results in a common M2 phenotype. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2015, 103, 2864–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouw, I.M.; van Wachem, P.B.; Molema, G.; Plantinga, J.A.; de Leij, L.F.; van Luyn, M.J. The foreign body reaction to a biodegradable biomaterial differs between rats and mice. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 52, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boháč, M.; Danišovič, Ľ.; Koller, J.; Dragúňová, J.; Varga, I. What happens to an acellular dermal matrix after implantation in the human body? A histological and electron microscopic study. Eur. J. Histochem. 2018, 62, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

(A) Disinfection with polyvidone iodine. (B) A skin incision of 8 mm was made along the right paramedian of the vertebral column. (C) Two subcutaneous pouches were created with a round scissor. (D) One porcine acellular dermal matrix (NovoMatrix – BioHorizons - Ontário, Canadá) (5mmx5mm size and 1.5mm height) was implanted subcutaneously in each of the right and left sides along the dorsal midline of each mouse. (E) Primary wound closure was achieved using 4 simple sutures with 5-0 nylon material.

Figure 1.

(A) Disinfection with polyvidone iodine. (B) A skin incision of 8 mm was made along the right paramedian of the vertebral column. (C) Two subcutaneous pouches were created with a round scissor. (D) One porcine acellular dermal matrix (NovoMatrix – BioHorizons - Ontário, Canadá) (5mmx5mm size and 1.5mm height) was implanted subcutaneously in each of the right and left sides along the dorsal midline of each mouse. (E) Primary wound closure was achieved using 4 simple sutures with 5-0 nylon material.

Figure 2.

Print screen from the LAS program screen. The H&E sections were analyzed, and linear measurements were performed. (A) Fibrous capsule thickness (mm). (B) Three measurements were taken for linear cell ingrowth through the graft (mm) and the mean value was recorded. (C) Macrophages and giant cells were counted within a 0.4 mm section and confirmed by TRAP and vimentin-stained sections. (20x magnification).

Figure 2.

Print screen from the LAS program screen. The H&E sections were analyzed, and linear measurements were performed. (A) Fibrous capsule thickness (mm). (B) Three measurements were taken for linear cell ingrowth through the graft (mm) and the mean value was recorded. (C) Macrophages and giant cells were counted within a 0.4 mm section and confirmed by TRAP and vimentin-stained sections. (20x magnification).

Figure 3.

Print screen from the LAS program screen. The H&E sections were analyzed, and cell ingrowth density was measured within the graft (*) in a 0.1mm2 area. (x20 magnification).

Figure 3.

Print screen from the LAS program screen. The H&E sections were analyzed, and cell ingrowth density was measured within the graft (*) in a 0.1mm2 area. (x20 magnification).

Figure 4.

Collagen fiber density measurements were performed in the region of interest (ROI), which is a rectangle of 0.6 mm2 area. The ROI area (red rectangle) was positioned tangentially to the graft and capsule intersection to measure both the graft* (A) and the host tissue(B). (Picrosirius stain - 20x magnification).

Figure 4.

Collagen fiber density measurements were performed in the region of interest (ROI), which is a rectangle of 0.6 mm2 area. The ROI area (red rectangle) was positioned tangentially to the graft and capsule intersection to measure both the graft* (A) and the host tissue(B). (Picrosirius stain - 20x magnification).

Figure 5.

Light microscopy of histological sections of porcine acellular dermal matrix graft with Hematoxylin and Eosin staining. (A) Longitudinal slice of the porcine acellular dermal matrix graft showing the matrix size (5x5 mm) x1.6. (B) The densely packed collagen fibers structure under x40 magnification. (C) The transversal slice of the porcine acellular dermal matrix graft revealing a thickness of 1.5 mm. (D) A x40 magnification from the same slice showing groups of dense collagen fibers in different orientations.

Figure 5.

Light microscopy of histological sections of porcine acellular dermal matrix graft with Hematoxylin and Eosin staining. (A) Longitudinal slice of the porcine acellular dermal matrix graft showing the matrix size (5x5 mm) x1.6. (B) The densely packed collagen fibers structure under x40 magnification. (C) The transversal slice of the porcine acellular dermal matrix graft revealing a thickness of 1.5 mm. (D) A x40 magnification from the same slice showing groups of dense collagen fibers in different orientations.

Figure 6.

Light microscopy of histological sections of subcutaneous porcine acellular dermal matrix grafts of rats at 7 (A,B), 14 (C,D), 21 (E,F) and 28 (G,H) days of repair. In (B,D,F,H), the asterisks (*) are over the area of the porcine acellular dermal matrix. In (D,F), the arrows point to multinucleated foreign body giant cells adhered to bundles of collagen fibers of the matrix. Whereas at 7 days (B) the transition between the porcine acellular dermal matrix and the connective tissue of the host is abrupt even with the onset of an inflammatory infiltrate, at 28 days (H) the contiguity of collagen fibers, the reduction of the inflammatory infiltrate, and the invasion of cells in the periphery of the acellular dermal matrix make it difficult to accurately identify its boundaries. Scale bar: in (G), repeats in (A,C,E) = 1,2 mm; in (H), and (B,D,F) = 100 μm. (Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining).

Figure 6.

Light microscopy of histological sections of subcutaneous porcine acellular dermal matrix grafts of rats at 7 (A,B), 14 (C,D), 21 (E,F) and 28 (G,H) days of repair. In (B,D,F,H), the asterisks (*) are over the area of the porcine acellular dermal matrix. In (D,F), the arrows point to multinucleated foreign body giant cells adhered to bundles of collagen fibers of the matrix. Whereas at 7 days (B) the transition between the porcine acellular dermal matrix and the connective tissue of the host is abrupt even with the onset of an inflammatory infiltrate, at 28 days (H) the contiguity of collagen fibers, the reduction of the inflammatory infiltrate, and the invasion of cells in the periphery of the acellular dermal matrix make it difficult to accurately identify its boundaries. Scale bar: in (G), repeats in (A,C,E) = 1,2 mm; in (H), and (B,D,F) = 100 μm. (Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining).

Figure 7.

Light microscopy of histological sections of subcutaneous porcine acellular dermal matrix grafts of rats at 7 (A), 14 (B–D), 21 (E), and 28 (F) days of repair. Vimentin labeling (A–C,E,F) and TRAP staining (D). The asterisks (*) are over the area of the porcine acellular dermal matrix. The arrows in B-E indicate multinucleated foreign body giant cells (FBGC) adherent to bundles of collagen fibers of the matrix. In (C) the vimentin labeling is denser in the cytoplasm of FBGC in the close vicinity to the fibers to which it is adherent. A blood vessel (arrowheads) is observed intermingling with the fibrous capsule in (D) and with the collagen bundles of the matrix in (F). Scale bars in (A,B,D–F) = 50 μm; in C = 20 μm.

Figure 7.

Light microscopy of histological sections of subcutaneous porcine acellular dermal matrix grafts of rats at 7 (A), 14 (B–D), 21 (E), and 28 (F) days of repair. Vimentin labeling (A–C,E,F) and TRAP staining (D). The asterisks (*) are over the area of the porcine acellular dermal matrix. The arrows in B-E indicate multinucleated foreign body giant cells (FBGC) adherent to bundles of collagen fibers of the matrix. In (C) the vimentin labeling is denser in the cytoplasm of FBGC in the close vicinity to the fibers to which it is adherent. A blood vessel (arrowheads) is observed intermingling with the fibrous capsule in (D) and with the collagen bundles of the matrix in (F). Scale bars in (A,B,D–F) = 50 μm; in C = 20 μm.

Figure 8.

Boxplots representing linear cell ingrowth over time in (A) and the area percent of cell ingrowth density in a ROI of 0.1mm2 over time in (B). The asterisks inside the box represent statistical differences between all the groups (Kruskal-Wallis test **** p < 0.0001). The other asterisks represent statistical differences within periods of time (* p = 0.0234; *** p = 0.0002; **** p < 0.0001) for Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

Figure 8.

Boxplots representing linear cell ingrowth over time in (A) and the area percent of cell ingrowth density in a ROI of 0.1mm2 over time in (B). The asterisks inside the box represent statistical differences between all the groups (Kruskal-Wallis test **** p < 0.0001). The other asterisks represent statistical differences within periods of time (* p = 0.0234; *** p = 0.0002; **** p < 0.0001) for Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

Figure 9.

Boxplots representing fibrous capsule length over time. No statistical differences between values were detected (p > 0.05).

Figure 9.

Boxplots representing fibrous capsule length over time. No statistical differences between values were detected (p > 0.05).

Figure 10.

(A) Boxplots representing the collagen fiber density in percent area (%) for the graft and host tissue evaluated at 7, 14, 21 and 28 days (ROI = 0.6mm2). The asterisks represent statistical differences within each time point (Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons, ** p = 0.0087; *** p = 0.0006). (B) Boxplot representing the ratio between the collagen fiber density of the graft and the host. The asterisk represents statistical differences within each time point (Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons, * p < 0.01).

Figure 10.

(A) Boxplots representing the collagen fiber density in percent area (%) for the graft and host tissue evaluated at 7, 14, 21 and 28 days (ROI = 0.6mm2). The asterisks represent statistical differences within each time point (Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons, ** p = 0.0087; *** p = 0.0006). (B) Boxplot representing the ratio between the collagen fiber density of the graft and the host. The asterisk represents statistical differences within each time point (Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons, * p < 0.01).

Figure 11.

Boxplots representing the number of FBGC in 0.4 mm length. A significant statistical difference was noted among the time points (** p = 0.0038). Statistical differences between groups were observed when comparing 7 and 14 days (* p = 0.024) and 7 and 21 days (** p = 0.0042) (Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s multiple comparison test).

Figure 11.

Boxplots representing the number of FBGC in 0.4 mm length. A significant statistical difference was noted among the time points (** p = 0.0038). Statistical differences between groups were observed when comparing 7 and 14 days (* p = 0.024) and 7 and 21 days (** p = 0.0042) (Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s multiple comparison test).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).