3. Analysis

Evolution begins at the atomic level (The Editors of Encyclopaedia 2021). For example, a large banana contains radioactive potassium producing one nuclear transformation per second or 18.4 becquerel. Biological pathways are constantly evolving. Pathways originally mapped using a specific cell type have established a good baseline, but knowledge of cell specificity has made their use in personalised medicine redundant (Sedley L, 2025). Due to epigenetic mechanisms, that is, the impact of the environment and the lifestyle on gene expression; biological pathways are unique to each cell, and each person.

Due to a constant flow of protons and dynamic electromagnetic interactions induced by epigenetics, computer simulations of deoxynucleic acid (DNA) show chromatin flows like a wave (Sedley L 2023). All matter above absolute zero temperature emit electromagnetic radiation (EMR) (Mulders MA 1987). Diagnostic medical technologies have been exploiting the natural occurrence human EMR for over a century (Mandell J 2013). EMR intensities cover a spectrum of wavelengths (Stark G 2021) which are characterised by their frequency, amplitude, phase, direction, velocity, and coherence of the radiation (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2021).

3.1. Photon

The photon is measured in electron volts (eV) (Butcher G 2016) and represents the electromagnetic potential exchanged when an electron transitions between orbits. It may or may not be visible to the human eye (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2021). All living organisms emit ultra-weak photon emissions (UPE), also known as biophotons, which range between 260 nm and 800 nm. Their low emission frequency results in weak intensity, rendering them undetectable to the human eye (Schutgens FWG, Neogi P et al 2009; Prasad A, Rossi C et al 2014; Chang JJ, Fisch J et al 2010).

Electromagnetic radiation (EMR) facilitates communication among various organisms, with microorganisms capable of transmitting signals over long distances and through significant barriers (Prasad A, Rossi C et al 2014).

3.2. Chromophores and Photoreceptors

Chromophores are atomic regions within molecules that create pigmentation through their interaction with electromagnetic radiation (Dawson PL, Acton JC 2013). When electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with energy between 400-700nm transfers between two orbitals of a chromophore, the human eye perceives this as colour (Stark G 2021).

In the eye, ultra-violet (UV) and visible light induce environmental cues are absorbed by chromophores of photoreceptors and are converted to intracellular signals (Sancar A 2000). Photoreceptors responsible for central circadian photo-entrainment are found abundantly in the eye. However, the human brain is also capable of detecting light without the use of the eyes (Sedley, L 2025)

3.3. Central Circadian Rhythm

Among all circadian rhythm regulators, light exerts the most powerful influence on biological timekeeping (Hudec M, Dankova P et al 2020). Each cell has a unique rhythm that is peripheral to the central circadian rhythm, but interacts with proteins of the central circadian rhythm (Matsui M S, Pelle E et al 2016).

3.4. Gene Regulation of the Circadian Rhythm

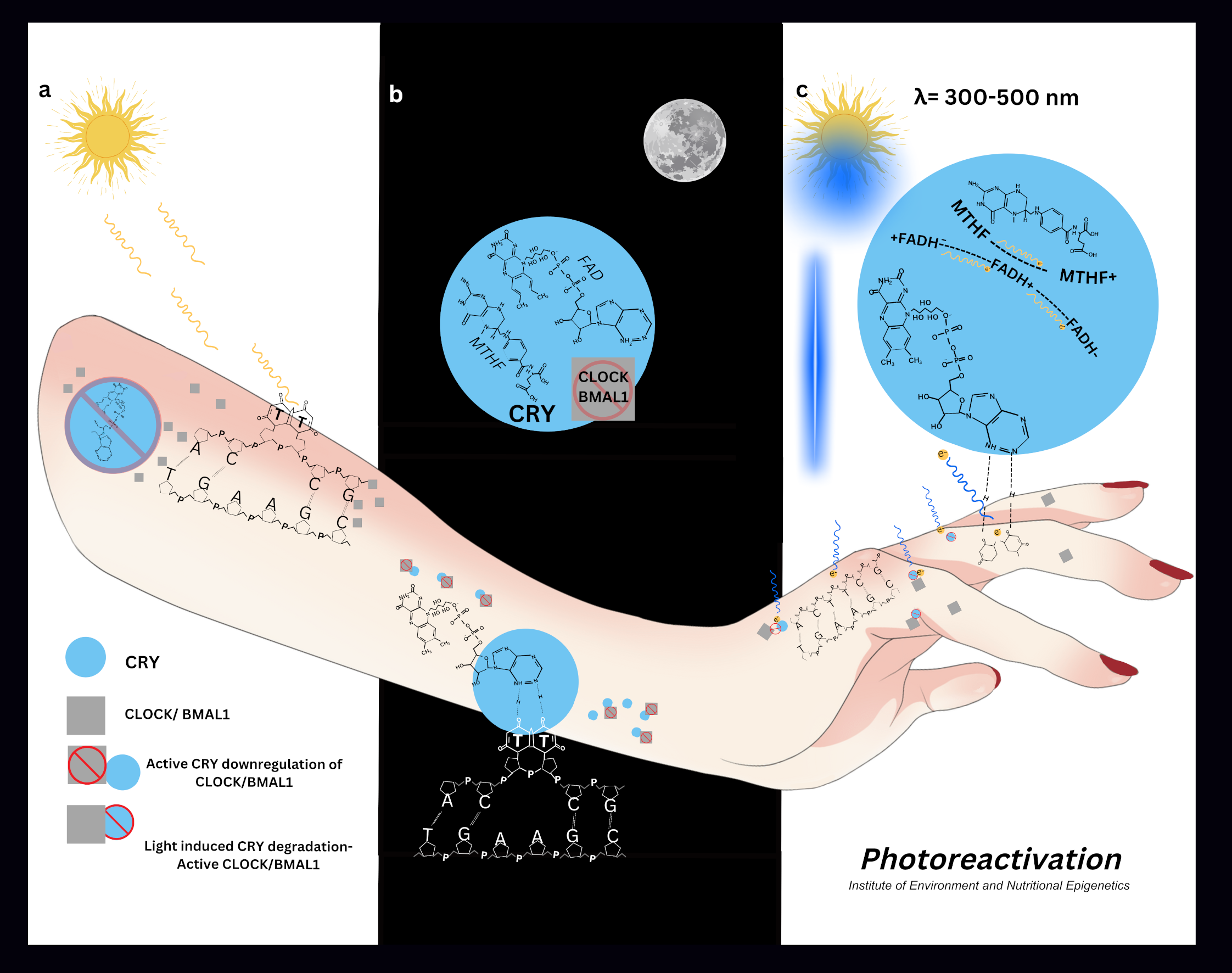

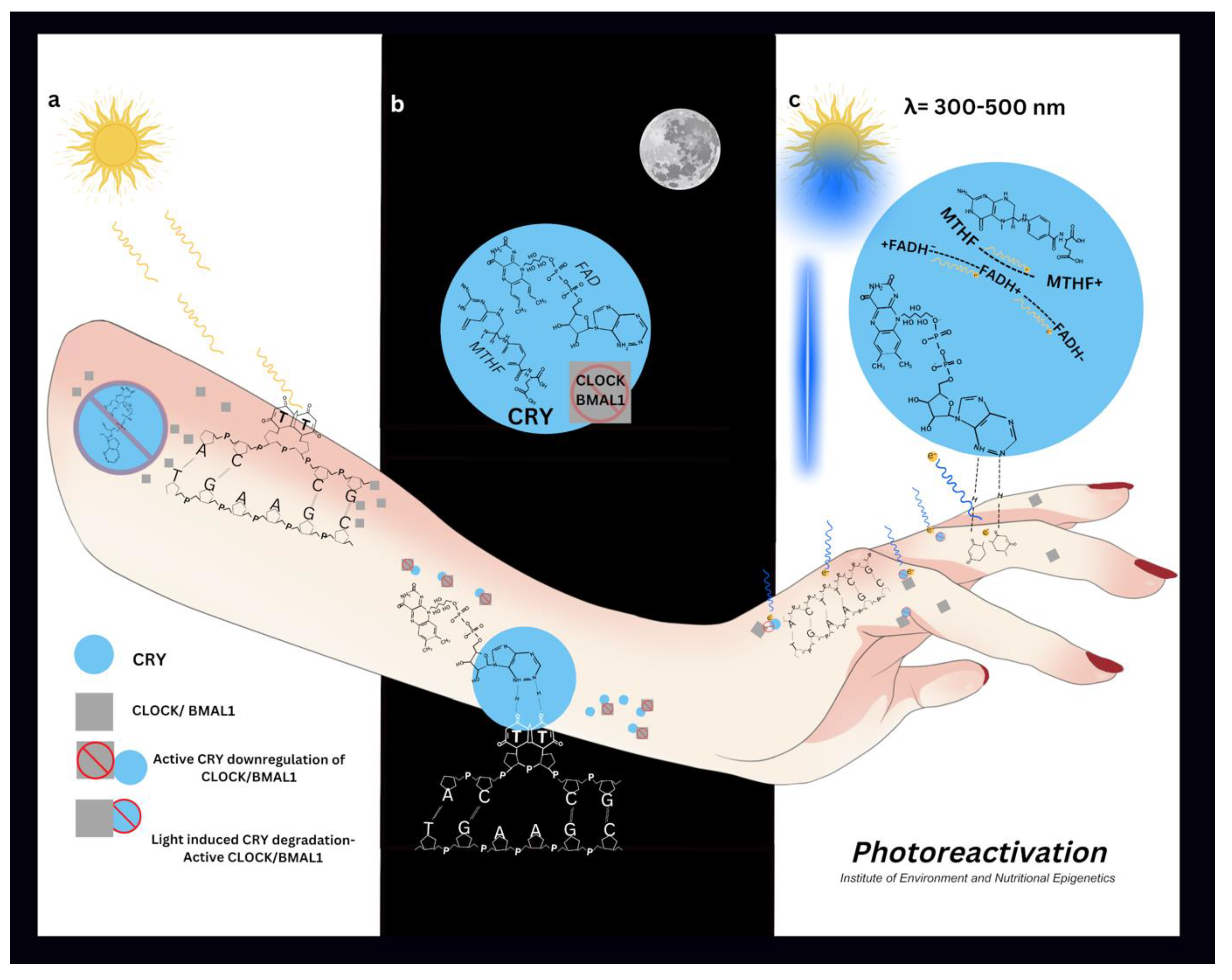

Clock Circadian Regulator (CLOCK/NPAS2) and Basic Helix Loop Helix ARNT Like 1 (BMAL1) are the primary regulators of the circadian rhythm (Hudec M, Dankova P et al 2020). CLOCK possess histone acetyltransferase activity which regulates chromatin remodelling events for circadian regulation of gene expression. CLOCK forms a dimer with BMAL1 and acetylates it at lysine 537 (Hirayama J, Sahar S et al 2007). Other important epigenetic regulators of circadian genes are Sirtiun Histone Deacetylase 1 (SIRT1), Histone Deacetylase 3 (HDAC3), and Histone Lysine Demethylase 5a (KDM5A/JARDI1a) (Hudec M, Dankova P et al 2020). Acetylated activation of BMAL1 triggers the recruitment of Cryptochrome Circadian Regulator 1 (CRY1) (Hirayama J, Sahar S et al 2007). CLOCK/BMAL1 complex binds Period Circadian Regulator (PER) at its E-box sequence in its profto initiate transcription. PER and CRY1 form a complex which inhibits the CLOCK-BMAL1 complex initiating the rhythmic circadian feedback mechanism (Hudec M, Dankova P et al 2020).

3.5. Circadian Rhythm and Pathology

Abnormal diurnal occupational or regional light exposure is associated with a range of symptoms and diseases (Silvani MI, Werder R et al 2022). And research pertaining to light therapy is growing in popularity (Sedley L 2025) (Strong RE, Marchant BK et al 2009).

3.6. Cryptochrome

Cryptochromes (CRY) serve as the primary photoreceptors in circadian rhythm regulation. These proteins contain two essential dietary-derived chromophores: flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) and methyltetrahydrofolate (MTHF). Together, these chromophores enable CRY to absorb UV-blue light at 420nm (Sancar A 2000).

The clock gene regulator FAD incorporates a riboflavin cofactor, which acts as a fluorescent pigment crucial for flavoproteins' redox electron transport. Light exposure irreversibly alters both the pigmentation and absorption characteristics of the flavin chromophore within the visual spectrum by modifying its redox state (Hernan B 2022) (Sedley, 2025)

3.7. Dietary Chromophores and Light Exposure

Chromophores within proteins like CRY photoreceptors are degraded into inactive products following exposure to UV-blue light (Holzer W, Shirdel J et al 2005). This irreversible reduction plays a significant role in the light induced resetting of protein activity, in this case the circadian rhythm. It does this by determining its maximum absorption within the protein structure (Hernan B 2022).

Food products exposed to light, influence enzyme activity through the production of toxic inhibitory products. For example, lumichrome is a metabolite of flavin reduction that inhibits active flavin absorption and transport, and has been implicated in number of pathological conditions (Sedley L 2025). Folate is also shown to be reduced 30-50% following UV exposure (Branda RF, Eaton JW 1978).

3.8. The Importance of the Sun

Vitamin D is the most widely studied essential molecule synthesised from sunlight. Dermal 7-dehydrocholesterol absorbs ultra-violet B (UV-B) wavelengths shorter than 315nm converting it to pre-vitamin D and then to the vitamin D3 isomer. The local atmosphere, sun protective clothing, the solar zenith angle, skin pigmentation, time of day, and age all determine the probability of a suitable photon reaching a molecule of 7-dehydrocholesterol for conversion (Webb AR 2006).

Over 1000’s of years, housing and clothing have led to sudden changes in the level of sun exposure for many populations. Adaptive skin lightening has allowed for greater penetration of essential physiological doses UV energy (Muehlenbein MP 2010).

3.9. Sun and Skin Cancer

Skin cancer is a pathological side-effect of excessive dermal UV radiation. Sun avoidance campaigns are promoted heavily as the incidence of skin cancer doubles every 10-20 years (Muehlenbein MP 2010).

3.10. DNA Damage and Dimerization

UV radiation causes DNA damage through dimerization of thymine or cytosine (Rastogi RP, Kumar RA et al 2010). Pyrimidine dimers are repaired by nucleotide excision repair pathway (NER) (Alcalay J, Freeman SE 1990) and photolyase proteins (Okamoto-Uchida Y, Izawa J et al 2018) all of which require a precise fluctuation of all epigenetic modulators (Sedley L 2020).

During replication, unrepaired dimers are incorporated into DNA and are associated with squamous and basal cell carcinomas (Muehlenbein MP 2010).

3.11. The Role of the Skin Peripheral Circadian Rhythm in Skin Cancer Prevention

CRY photoreceptors and CLOCK genes are found abundantly in skin and hair follicles (Lyons A, Moy L et al 2019) (Suh S, Choi EH et al 2020) (Buscone S, Mardaryev AN et al 2017). Epidermal peripheral circadian rhythms regulate the cell cycle, DNA synthesis, repair, water loss, proliferation, sebum production and temperature (Matsui M S, Pelle E et al 2016).

Circadian gene expression can be parallel to a cell's lifespan (Johnson CH 2010) (Oklejewicz M, Destici E et al 2008), driving cell division (Johnson CH 2010) (Zámborszky J, Hong CI et al 2007). DNA damage and circadian rhythms are intimately connected (Okamoto-Uchida Y, Izawa J et al 2018) and disruptions to circadian rhythms are implicated in a range of malignancies (Kang TH, Lindsey-Boltz L, A et al 2010). The nucleotide excision repair (NER) DNA repair pathway is controlled by CRY (Kang TH, Lindsey-Boltz L, A et al 2010) and oscillates with the circadian rhythm (Hogenesch JB 2009). DNA damage disrupts the cell phase; the pause allows time for DNA repair and resets the cells rhythm (Oklejewicz M, Destici E et al 2008).

3.12. Mammalian Photolyase Activity

Photolyase enzymes repair DNA damage via light dependant photoreactivation, which is rapid, error free, and requires only light EMR (Sancar A 2000). Photolyase activity has been detected in human cells (Sutherland BM, Bennett PV 1995), yet remains controversial due to circadian light dependant difficulties in detection.

3.13. CRY2 Homology

Human CRY2 has 20-25% sequence homology to microbial Photolyase, and 40-60% sequence homology to Drosophila (4- 6) Photolyase. Therefore CRY2 is likely to be the source of human photolyase activity (Todo T, Ryo H et al 1996). A circadian influence on the photolyase activity was noted when human photoreactivation was delayed (Roza L, De Gruijl FR et al 1990).

Mammalian studies of CRY photolyase activity have been far from equivalent due to natural human circadian conditions; such as the duration of light exposure, light intensity, and the cell phase required for successful photoreactivation (Okamoto-Uchida Y, Izawa J et al 2018) (Sutherland BM, Bennett PV 1995) (Hsu DS, Zhao X et al 1996). For example, in one particular study, cells were incubated in the dark for only 10 mins and then re-exposed to a 366nm UV-A black light at 4°Celcius for only one hour which is inadequate time for CRY re- synthesis/translocation which requires a full circadian cycle (Hsu DS, Zhao X et al 1996).

3.14. Chemicals and Skin Cancer

Sunscreens, make-up, tanning lotions, and after-sun moisturisers can contain epigenetic modulators which can interfere with DNA repair mechanisms. Sunscreens and after-sun treatments can contain salicylate derived compounds (Cancer Council 2023) which inhibit primary CBP-p300 acetyltransferase expression essential for DNA repair (Shirakawa K, Wang L et al 2016). In addition, natural sunscreen products containing zinc, nicotinamide or fatty acids which can influence epigenetic mechanisms resulting in reduced photolyase activity or inactivation of NER (Xu Y, Shi Z et al 2022) (Feldman JL, Dittenhafer-Reed KE et al 2015).

3.15. Skin Cancer a Unique Perspective

It was recognised in the 1950’s that coal tar derived paraffins provided effective protection against sunburn (Russell B, Anderson D 1950), and in the 1960’s, studies on mice showed that sunscreens containing the chromophore para-amino benzoic acid (PABA) could protect against sun-induced cancers (Knox JM, Griffin AC et al 1960). However, the sun is not the only factor influencing skin cancer. In 1775, an increased risk of scrotal squamous cell carcinoma was reported in chimney sweeps exposed to hydrocarbon coal tar products and populations less likely to wear protective clothing on the extremities have a reduced incidence of body melanoma but an increased risk of malignant melanoma on the soles of the feet and palms, suggesting hydrocarbon chemicals and a lack of skin pigmentation influence the malignant transformation (Diepgen TL, Mahler V 2002).

Coal tar is comprised of 40% hydrogen, 42% carbon and 10% water and is an active ingredient in over-the- counter medical products and is used as a denaturant or preservative in cosmetics, soaps, detergents, and lotions. Coal tar derived polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) are used in industrial applications from asphalt to sealants. Dermal absorption of PAH, leads to systemic malignancy in over 50% of murine cases (McCormick S, Snawder JE et al 2022) (Nayak S, Patnaik L 2022). Levels of only 0.1% is required for genotoxicity. The most recent assessment on the safety of PAHs and their use in cosmetics was conducted by the American College of Toxicology (2008) which concluded that despite evidence of significant carcinogenicity, more research is needed to conclude their safety. To my knowledge, no additional research by has been published.

3.16. Light Dependant Epigenetic Mechanisms

One carbon metabolism (1-CM) or methylation purposes also requires light energy. Like CRY, the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) protein requires the dietary derived riboflavin containing light and heat sensitive FAD cofactor (Rosenblatt DS, Erbe RW 1977) (Hühner J, Ingles- Prieto Á et al 2015) (Igari S, Ohtaki A et al 2011). The product of MTHFR, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate is a quencher of photosensitisers known to inhibit DNA strand breaks and its synthetic counterpart folic acid, promotes double stranded DNA breaks in a dose dependant manner (Offer T, Ames BN et al 2007).

Environmental methyl radicals are formed via UV oxidation of methane (Leighton PA 1961). Adaptive selection of the MTHFR gene and the consequent down-regulation of 1-CM is seen in residents of high altitude (Yang J, Jin ZB et al 2017), possibly due to differences in UV induced degradation of the 1-C derived chromophore (Branda RF, Eaton JW 1978), and environmental pressures like CO2 methane concentrations (Sedley 2020)

1-C methylation epigenetic mechanisms provide another example of delayed DNA repair due to circadian regulation. 5-methyltetrahydrofolate is sequestered and translocated to the nucleus by serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT) following sumoylation. Sumolyation is responsive to UV radiation and SHMT is expressed primarily in light sensitive tissues. SHMT translocation and protein levels are increased 12-24 hours in response to UV treatment, however its expression remains stable. SHMT 5’ untranslated region contains an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) which is activated in response to non - lethal UV treatment stimulating protein translation and DNA repair. (Fox JT, Shin WK et al 2009).

Circadian genes also function as transcription factors for the regulation of 1-C metabolism. MAT2A carries a binding site for transcription factor CLOCK and may play a role in a metabolic switch that separates 1-C metabolism's methylation from thymine synthesis for replication (Genome Reference Consortium 2022).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Together this research suggests the transcription factor vitamin D and melanin for sun protection may not be the only beneficial effects derived from the sun.

A greater understanding of the importance of sunlight in DNA repair and the epigenetic mechanisms associated with the repair, including the timing of essential processes will be very valuable in reducing the incidence of skin cancer and advancing skin cancer preventative medicine.

Regardless of whether mammalian cells have adequate photolyase activity, all mechanisms promoting DNA repair, require a timely and highly specific fluctuation of epigenetic mechanisms, which can be interrupted by topical, environmental, or dietary factors.

Prior to the knowledge of epigenetic mechanisms, cosmetics were developed to protect the skin from the harmful effects of UV radiation, many of which, may now be considered harmful if not applied at the appropriate time.

The influence of light exposure on dietary chromophores in food products is an important area of research due to their indispensable role in epigenetics mechanisms and gene expression.

Finally, the research underscores the necessity of integrating quantum biology and epigenetics into public health policies, calling for personalisation of recommendations, and computational models to enhance health analysis and treatment strategies.