Submitted:

04 March 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

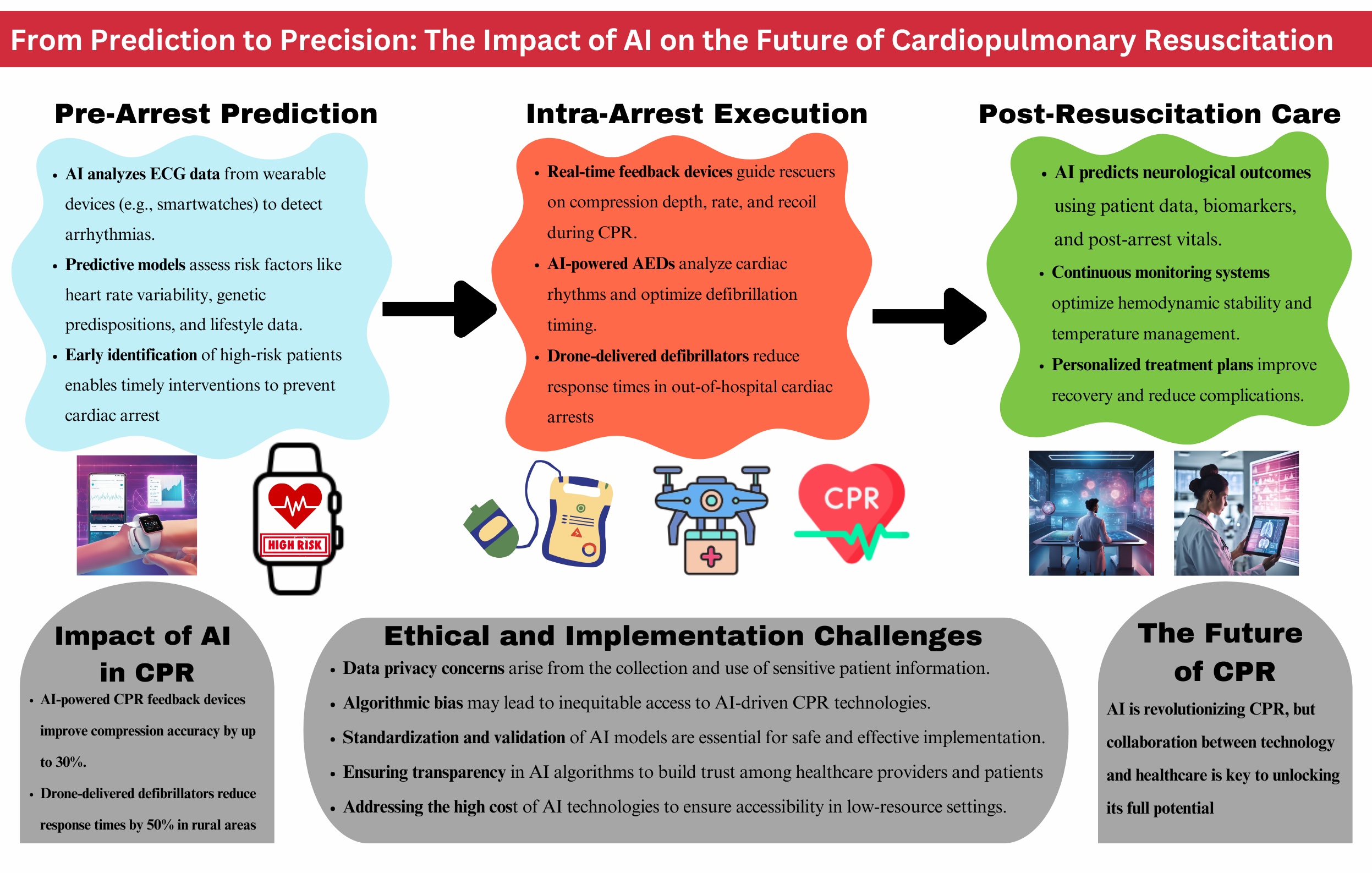

1. Introduction

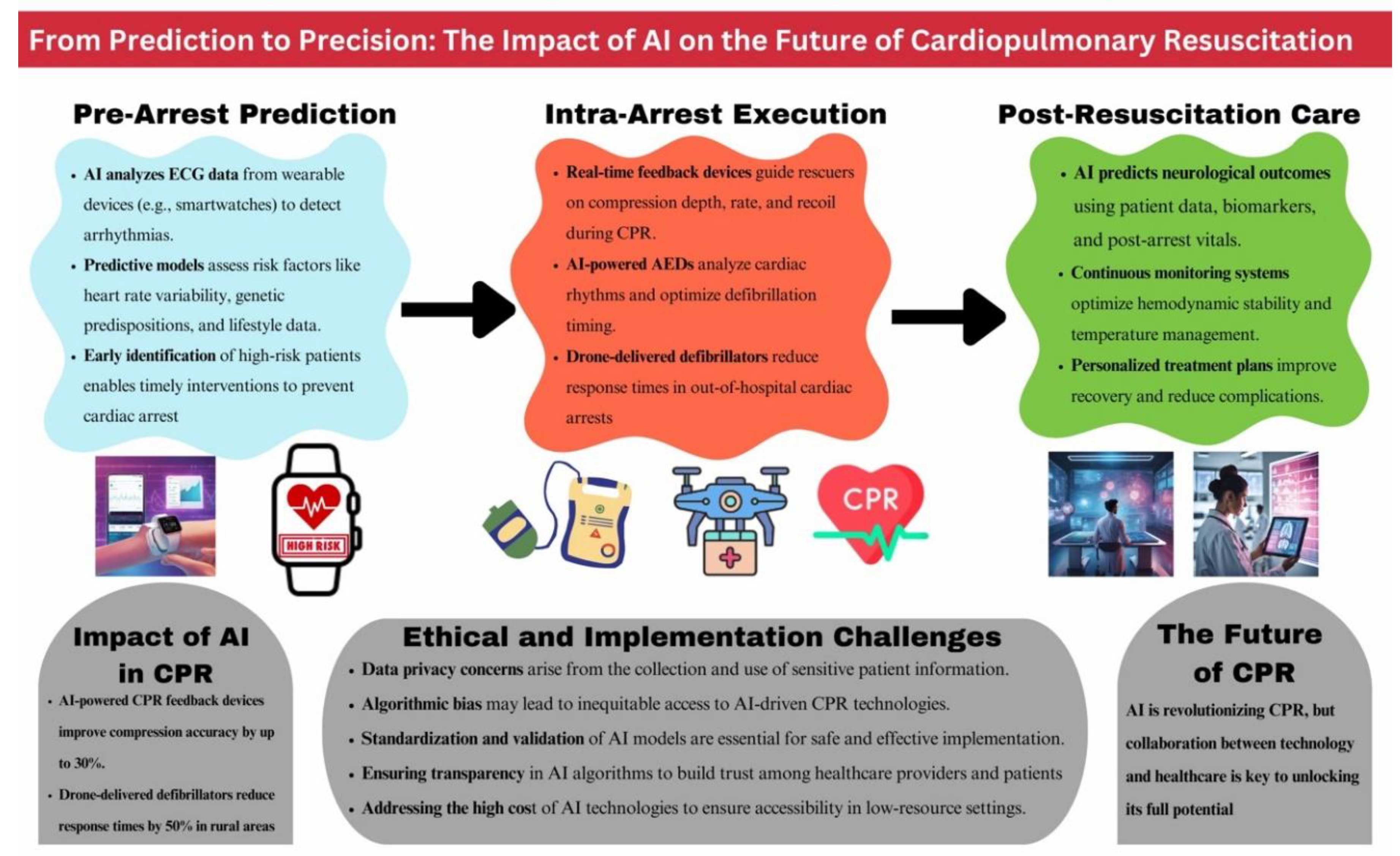

2. Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Search and Study Selection:

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria:

3. Results:

3.1. Pathophysiology, Risk Factors, and Triggers of Sudden Cardiac Arrest

3.2. Current Strategies for Predicting Sudden Cardiac Death

3.3. Historical Development and Advances in CPR

4. Recent Advancements in CPR

4.1. Mechanical CPR Devices

4.2. Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (ECPR)

4.3. Feedback Mechanisms

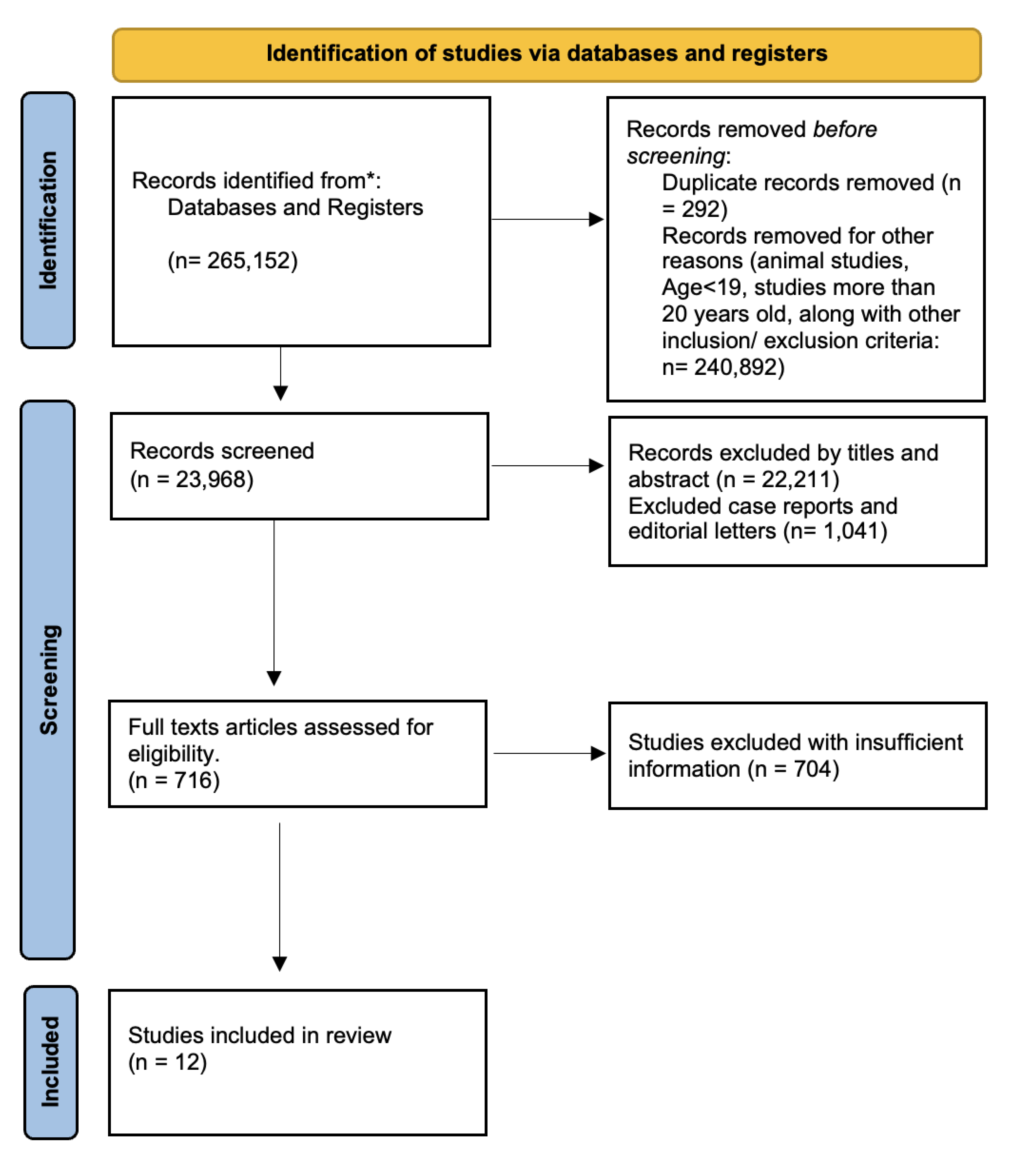

5. Technological Innovations in CPR

6. AI in Post-Cardiac Arrest Care

Institutional review board approval and ethics committee clearance

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bednarz K, Goniewicz K, Al-Wathinani AM, Goniewicz M. Emergency Medicine Perspectives: The Importance of Bystanders and Their Impact on On-Site Resuscitation Measures and Immediate Outcomes of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. JCM. 2023 Oct 28;12(21):6815.

- Zheng W, Zheng J, Wang C, Pan C, Zhang J, Liu R, et al. The development history, current state, challenges, and future directions of the BASIC-OHCA registry in China: A narrative review. Resusc Plus. 2024 Jun;18:100588.

- Kumari S, Kumari A, Asim R, Khan R. Multi-faceted role of artificial intelligence (AI) in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR): a narrative review. AI Ethics [Internet]. 2024 Dec 5 [cited 2025 Feb 12]; Available from: https://link.springer.com/10. 1007.

- Levitt CV, Boone K, Tran QK, Pourmand A. Application of Technology in Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation, a Narrative Review. JCM. 2023 Nov 29;12(23):7383.

- Semeraro F, Schnaubelt S, Malta Hansen C, Bignami EG, Piazza O, Monsieurs KG. Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the next decade: Predicting and shaping the impact of technological innovations. Resuscitation. 2024 Jul;200:110250.

- Waldmann V, Jouven X, Narayanan K, Piot O, Chugh SS, Albert CM, et al. Association Between Atrial Fibrillation and Sudden Cardiac Death: Pathophysiological and Epidemiological Insights. Circulation Research. 2020 Jul 3;127(2):301–9.

- Arzamendi D, Benito B, Tizon-Marcos H, Flores J, Tanguay JF, Ly H, et al. Increase in sudden death from coronary artery disease in young adults. American Heart Journal. 2011 Mar;161(3):574–80.

- Yang KC, Kyle JW, Makielski JC, Dudley SC. Mechanisms of Sudden Cardiac Death: Oxidants and Metabolism. Circulation Research. 2015 Jun 5;116(12):1937–55.

- Adabag AS, Luepker RV, Roger VL, Gersh BJ. Sudden cardiac death: epidemiology and risk factors. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010 Apr;7(4):216–25.

- Kirchhof P, Breithardt G, Eckardt L. Primary prevention of sudden cardiac death. Heart. 2006 Dec 1;92(12):1873–8.

- Lerma C, Glass L. Predicting the risk of sudden cardiac death. The Journal of Physiology. 2016 May;594(9):2445–58.

- Perkins GD, Gräsner JT, Semeraro F, Olasveengen T, Soar J, Lott C, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Executive summary. Resuscitation. 2021 Apr;161:1–60.

- Kapoor, MC. The History and Evolution of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Journal of Resuscitation. 2024 Dec;1(1):3.

- Khan SU, Lone AN, Talluri S, Khan MZ, Khan MU, Kaluski E. Efficacy and safety of mechanical versus manual compression in cardiac arrest – A Bayesian network meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2018 Sep;130:182–8.

- El-Menyar A, Naduvilekandy M, Rizoli S, Di Somma S, Cander B, Galwankar S, et al. Mechanical versus manual cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR): an umbrella review of contemporary systematic reviews and more. Crit Care. 2024 Jul 30;28(1):259.

- Larik MO, Ahmed A, Shiraz MI, Shiraz SA, Anjum MU, Bhattarai P. Comparison of manual chest compression versus mechanical chest compression for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2024 Feb 23;103(8):e37294.

- Abrams D, MacLaren G, Lorusso R, Price S, Yannopoulos D, Vercaemst L, et al. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults: evidence and implications. Intensive Care Med. 2022 Jan;48(1):1–15.

- Yannopoulos D, Bartos J, Raveendran G, Walser E, Connett J, Murray TA, et al. Advanced reperfusion strategies for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and refractory ventricular fibrillation (ARREST): a phase 2, single centre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2020 Dec;396(10265):1807–16.

- Scquizzato T, Bonaccorso A, Swol J, Gamberini L, Scandroglio AM, Landoni G, et al. Refractory out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Artificial Organs. 2023 May;47(5):806–16.

- Hashem A, Mohamed MS, Alabdullah K, Elkhapery A, Khalouf A, Saadi S, et al. Predictors of Mortality in Patients With Refractory Cardiac Arrest Supported With VA-ECMO: A Systematic Review and a Meta-Analysis. Current Problems in Cardiology. 2023 Jun;48(6):101658.

- Dalia AA, Lu SY, Villavicencio M, D’Alessandro D, Shelton K, Cudemus G, et al. Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: Outcomes and Complications at a Quaternary Referral Center. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia. 2020 May;34(5):1191–4.

- Stoll SE, Paul E, Pilcher D, Udy A, Burrell A. Hyperoxia and mortality in conventional versus extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Journal of Critical Care. 2022 Jun;69:154001.

- Richardson A (Sacha) C, Tonna JE, Nanjayya V, Nixon P, Abrams DC, Raman L, et al. Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Adults. Interim Guideline Consensus Statement From the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization. ASAIO Journal. 2021 Mar;67(3):221–8.

- Wagner M, Gröpel P, Eibensteiner F, Kessler L, Bibl K, Gross IT, et al. Visual attention during pediatric resuscitation with feedback devices: a randomized simulation study. Pediatr Res. 2022 Jun;91(7):1762–8.

- Jaskuła J, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Jaros K, Wordliczek J, Cebula G, Kloch M. Improvement in chest compression quality performed by paramedics and evaluated with a real-time feedback device: Randomized trial. Kardiol Pol. 2023 Feb 28;81(2):177–9.

- Baldi E, Cornara S, Contri E, Epis F, Fina D, Zelaschi B, et al. Real-time visual feedback during training improves laypersons’ CPR quality: a randomized controlled manikin study. CJEM. 2017 Nov;19(06):480–7.

- Koyama Y, Matsuyama T, Kaino T, Hoshino T, Nakao J, Shimojo N, et al. Adequacy of compression positioning using the feedback device during chest compressions by medical staff in a simulation study. BMC Emerg Med. 2022 Dec;22(1):76.

- Iskrzycki L, Smereka J, Rodriguez-Nunez A, Barcala Furelos R, Abelarias Gomez C, Kaminska H, et al. The impact of the use of a CPRMeter monitor on quality of chest compressions: a prospective randomised trial, cross-simulation. Kardiol Pol. 2018 Mar 16;76(3):574–9.

- Wu C, You J, Liu S, Ying L, Gao Y, Li Y, et al. Effect of a feedback system on the quality of 2-minute chest compression-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a randomised crossover simulation study. J Int Med Res. 2020 Apr;48(4):0300060519894440.

- Vahedian-Azimi A, Hajiesmaeili M, Amirsavadkouhi A, Jamaati H, Izadi M, Madani SJ, et al. Effect of the Cardio First AngelTM device on CPR indices: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Crit Care. 2016 Dec;20(1):147.

- Kopacz K, Fronczek-Wojciechowska M, Jaźwińska A, Padula G, Nowak D, Gaszyński T. Influenece of the CPRmeter on angular position of elbows and generated forces during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Int J Occup Med Environ Health [Internet]. 2017 Jul 6 [cited 2025 Feb 12]; Available from: http://www.journalssystem.com/ijomeh/Influenece-of-the-CPRmeter-on-angular-position-of-elbows-and-generated-forces-during-cardiopulmonary-resuscitation-,6 6857, 0, 2html.

- Crowe C, Bobrow BJ, Vadeboncoeur TF, Dameff C, Stolz U, Silver A, et al. Measuring and improving cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality inside the emergency department. Resuscitation. 2015 Aug;93:8–13.

- Viderman D, Abdildin Y, Batkuldinova K, Badenes R, Bilotta F. Artificial Intelligence in Resuscitation: A Scoping Review. JCM. 2023 Mar 14;12(6):2254.

- Ecker H, Adams NB, Schmitz M, Wetsch WA. Feasibility of real-time compression frequency and compression depth assessment in CPR using a “machine-learning” artificial intelligence tool. Resuscitation Plus. 2024 Dec;20:100825.

- Di Mitri D, Schneider J, Trebing K, Sopka S, Specht M, Drachsler H. Real-Time Multimodal Feedback with the CPR Tutor. In: Bittencourt II, Cukurova M, Muldner K, Luckin R, Millán E, editors. Artificial Intelligence in Education [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020 [cited 2025 Feb 12]. p. 141–52. (Lecture Notes in Computer Science; vol. 12163). Available from: http://link.springer.com/10. 1007.

- Di Mitri D, Schneider J, Specht M, Drachsler H. Detecting Mistakes in CPR Training with Multimodal Data and Neural Networks. Sensors. 2019 Jul 13;19(14):3099.

- Marhamati M, Dorry B, Imannezhad S, Hussain MA, Neshat AA, Kalmishi A, et al. Patient’s airway monitoring during cardiopulmonary resuscitation using deep networks. Medical Engineering & Physics. 2024 Jul;129:104179.

- Kim T, Suh GJ, Kim KS, Kim H, Park H, Kwon WY, et al. Development of artificial intelligence-driven biosignal-sensitive cardiopulmonary resuscitation robot. Resuscitation. 2024 Sep;202:110354.

- Ahn S, Jung S, Park JH, Cho H, Moon S, Lee S. Artificial intelligence for predicting shockable rhythm during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: In-hospital setting. Resuscitation. 2024 Sep;202:110325.

- Aqel S, Syaj S, Al-Bzour A, Abuzanouneh F, Al-Bzour N, Ahmad J. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications in Sudden Cardiac Arrest Prediction and Management: A Comprehensive Review. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2023 Nov;25(11):1391–6.

- Park S, Yoon H, Yeon Kang S, Joon Jo I, Heo S, Chang H, et al. Artificial intelligence-based evaluation of carotid artery compressibility via point-of-care ultrasound in determining the return of spontaneous circulation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2024 Sep;202:110302.

- Ebell, MH. Artificial neural networks for predicting failure to survive following in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Fam Pract. 1993 Mar;36(3):297–303.

- Yammouri G, Ait Lahcen A. AI-Reinforced Wearable Sensors and Intelligent Point-of-Care Tests. JPM. 2024 Nov 1;14(11):1088.

- Johnsson J, Björnsson O, Andersson P, Jakobsson A, Cronberg T, Lilja G, et al. Artificial neural networks improve early outcome prediction and risk classification in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients admitted to intensive care. Crit Care. 2020 Dec;24(1):474.

- Amacher SA, Arpagaus A, Sahmer C, Becker C, Gross S, Urben T, et al. Prediction of outcomes after cardiac arrest by a generative artificial intelligence model. Resuscitation Plus. 2024 Jun;18:100587.

- Okada Y, Mertens M, Liu N, Lam SSW, Ong MEH. AI and machine learning in resuscitation: Ongoing research, new concepts, and key challenges. Resuscitation Plus. 2023 Sep;15:100435.

- Khawar MM, Abdus Saboor H, Eric R, Arain NR, Bano S, Mohamed Abaker MB, et al. Role of artificial intelligence in predicting neurological outcomes in postcardiac resuscitation. Annals of Medicine & Surgery. 2024 Dec;86(12):7202–11.

- Reddy VS, Stout DM, Fletcher R, Barksdale A, Parikshak M, Johns C, et al. Advanced artificial intelligence–guided hemodynamic management within cardiac enhanced recovery after surgery pathways: A multi-institution review. JTCVS Open. 2023 Dec;16:480–9.

- Nedadur R, Bhatt N, Liu T, Chu MWA, McCarthy PM, Kline A. The Emerging and Important Role of Artificial Intelligence in Cardiac Surgery. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2024 Oct;40(10):1865–79.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

|

b) Non-English text |

|

c) Animal studies |

|

d) Age: below 19 years of age |

|

e) Paid studies and studies that are not free full - text |

| f)Free full papers |

| Database | Search strategy | Search results |

|---|---|---|

|

PubMed/ EMBASE: |

|

22,808 |

| Google scholar: |

|

1,160 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).