1. Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) consists of inflammation of pancreas due to various causes with variable involvement of secondary other organs [

1]. AP represents one of the main causes of abdominal pathology and hospitalization, with an annual global incidence of approximately 5-80 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. The highest incidence occurs in Finland and United States and is doubled in the last decades [

2,

3]. In Italy, the incidence of AP is about 31 cases per 100.000 inhabitants, in line with the global incidence [

4,

5]. The two most common causes of AP are gallstones and alcohol abuse, which comprise 60-80% of cases. Other less common causes are hypertriglyceridemia, hypercalcemia, viral infections (mumps, coxsackie, viral hepatitis, Covid 19 pancreatitis-like symptoms), bacteria (Mycoplasma pneumoniae and leptospirosis), biliary parasites (Ascaris lumbricoides, Fasciola hepatica, and hydatid disease), drugs (azathioprine, mercaptopurine, didanosine), pancreatic tumours, trauma, surgery, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), Oddi dysfunction and congenital abnormalities (pancreas divisum, annular pancreas, choledochocele, duodenal duplication cyst). The idiopathic forms are usually related to biliary microlithiasis or sludge [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

AP may have a variable clinical presentation. Most cases are represented by mild forms and only 10-30% of cases by severe forms which can complicate with sepsis and multiple organ failure, with a mortality rate which can comprise about half of patients. These two groups had different management. Mild forms are usually treated with supportive cares in accordance with international guidelines while the severe forms may require intensive care unit admission and eventually surgical, endoscopic or radiological approach [

2,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The initial diagnosis of AP is based on the presence of two out of three fundamental parameters: the presence of abdominal pain attributable to the disease (epigastric or left upper quadrant constant pain with radiation to the back, chest, or flanks), lipase or amylase level 3 times higher than the normal value, characteristic findings from abdominal imaging. In this contest, imaging is useful to confirm the clinical diagnosis and to evaluate the severity of the disease and the aetiology. Transabdominal ultrasound (TA-US) is usually regarded as the first line imaging modality, but it has several limitations. Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CE-CT) is the gold standard technique to confirm the diagnosis, stage the disease and evaluate the presence of complications. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) represents an alternative method for patients with iodine allergies and renal insufficiency and has demonstrated a high sensibility in the identification of small fluid collections, parenchymal necrosis and local complications [

12,

17,

18,

19,

20]. The aim of this review is to present a critical overview of the main radiological techniques for the diagnosis and staging of AP and its complications.

2. Classification of Acute Pancreatitis and Complications

The revised Atlanta classification system distinguishes AP in two morphological types (oedematous and necrotising), early and late pancreatitis and in mild, moderate-severe and severe pancreatitis. The same system provides a classification of complications secondary to AP [

21].

2.1. Morphological Classification

The interstitial oedematous pancreatitis represents the commonest form of AP and consists of oedema and enlargement of pancreas due to inflammatory oedema. Pancreatic inflammation may be focal or diffuse. This form is usually associated with peripancreatic effusion and resolves in few weeks. Necrotising pancreatitis represent 5-10% of AP. Necrosis usually involves pancreatic and peripancreatic tissue and less commonly the peripancreatic or pancreatic tissue alone. Pancreatic necrosis may be diffuse or focal. This form evolves over several days and has a higher degree of morbidity and mortality, in particular if the necrosis became infected [

21].

2.2. Phases of Acute Pancreatitis

The early phase is the initial stage of AP, characterized by a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) secondary to pancreatic damage. The early phase lasts usually over the first week but may extend into the second week. If the SIRS became persistent during this time, there is a higher risk to develop early organ failure and severe forms [

21,

22,

23]. The late phase is observed in patients with persistent inflammatory response over the first week and it is associated with moderate severe or severe forms with or without local complications. This phase can be prolonged for weeks or months [

21,

22,

23].

2.3. Severity of Acute Pancreatitis

In accordance with modified Atlanta criteria, mild acute pancreatitis is defined as acute inflammation of pancreas without organ failure or complications. This type is usually self-limiting during the first week and treated only with supportive cares. Moderately severe acute pancreatitis is characterised by the presence of transient organ failure (<48h) and/or local or systemic complications. Severe acute pancreatitis is characterised by persistent organ failure (>48h), and it is usually associated with local or systemic complications. The prognosis is poor with a mortality rate ranging from 30% to 60%. [

21,

24,

25,

26].

Several clinical scoring systems have been developed to define the severity of AP, and several papers have addressed their efficacy and reliability although with not so satisfactory results [

27]. The most used are the Ranson score and the Apache score. Another score is the BISAP SCORE. The first uses 11 criteria while the second uses 12 criteria, with 1 point assigned for each parameter. A Ranson score equal to or greater than 3 and an Apache score equal to or greater than 8 indicates severe AP. BISAP score (0-5) is used to identify the patients within 24 h of admission who are at risk of developing severe disease or organ failure; a score equal to or greater than 3 is the most used cut off for sever AP [

17,

25,

28,

29,

30,

31]. It has the advantage of being more easily applicable in a real-world setting.

In general, according to the revised Atlanta criteria, severe acute pancreatitis is defined by the presence of at least one of the following criteria: organ failure (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg, PaO2 ≤ 60 mmHg, serum creatinine>2 mg/dL, gastrointestinal bleeding>500 mL/day); presence of local complications (necrosis, infection, abscess, pseudocyst);Ranson score ≥3;APACHE II score≥8 [

1].

2.4. Local Complications

Local complications of AP can be divided in non-vascular and vascular complications. The more frequent non-vascular complications are peripancreatic fluid collections. They are usually divided in early and late collections. Early collections include acute peripancreatic fluid collections (APFCs) and acute necrotic collections (ANCs) occurring within four weeks. Acute pancreatic fluid collections (APFCs) are collections of fluid resulting from pancreatic or peripancreatic inflammation or pancreatic duct disruption. These collections are usually localized in the lesser sac but can be detected in the transverse mesocolon, mesenteric root, anterior pararenal space, gastro-hepatic, gastrocolic and gastrosplenic space. ANCs develop from pancreatic and/or peripancreatic necrosis. They are usually localized in the pancreas, replacing pancreatic tissue, or in peripancreatic region and contain necrotic tissue, haemorrhage, fat or necrotic fat. Most acute fluid collections resolve in the first four weeks. Late fluid collections include pseudocysts (PCs) and walled off necrosis (WON), They occur usually after 4 weeks and evolve from persistent APFCs and ANCs, respectively. These collections are enclosed by a non-epithelized fibrous or granulation tissue wall. Non-vascular complications include also infected pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis, infected pseudocysts and fistulas. Infected necrosis and infected PCs are related to enteric Gram- bacteria invasion and both can lead to abscess formation. Infected necrosis represents one of the worst complications of AP. It occurs especially in patients with prolonged hospitalization, and account for 80% of deaths in AP patients. Fistula is a rare complication secondary to pancreatic tissue disruption and pancreatic juice leakage, which may occur with peripancreatic organs and tissues, small bowel, colon or skin. Vascular complications are mainly thrombosis of portal venous system and haemorrhage. Portal venous system thrombosis involves usually the splenic vein and is related to inflammatory intimal damage, activation of coagulation cascade due to systemic inflammation or extrinsic compression by peripancreatic fluid collections. Haemorrhage is usually secondary to pancreatitis-induced gastroduodenitis, peptic ulcer or, more frequently, arterial intimal erosion, which can lead to direct bleeding or formation of pseudoaneurysms. The most affected arteries are the splenic artery, gastroduodenal artery and the pancreaticoduodenal artery [

2,

17,

23,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

3. Imaging

3.1. Ultrasound

Transabdominal ultrasound (TA-US) is the first-line imaging modality in the early acute phase as it is worldwide available, easy to use, repeatable and not use ionizing radiations.

TA-US Features, Role and Limitations

In the acute phase, the pancreas may appear normal or enlarged. The gland enlargement is assessed by measuring the anteroposterior diameter at the level of the pancreatic body. A diameter greater than 24 mm and an anterior convexity of the gland suggest an enlargement due to oedema. The echogenicity may be normal, hypoechoic or heterogenous in relation to oedema or necrosis and a marked hypoechogenicity is observed in case of severe oedema or diffuse parenchymal necrosis. Another application of TA-US in the acute setting is the identification of non-vascular and vascular complications. Early acute fluid collections are visible as hypoechoic or anechoic areas with irregular or indefinite borders. Late acute fluid collections are often well defined, hypoechoic or anechoic masses, with at least 1-2-mm thick wall. Necrotic debris can be detected as solid, echoic areas within the fluid collection. They may be detected with US in peripancreatic region or in distant peritoneal or retroperitoneal recesses and in pelvic spaces. The presence of hyperechoic air bubbles may suggest superinfection. Arterial pseudoaneurysms are vascular dilatation of arterial vessels (in particular gastroduodenal, pancreatoduodenal and splenic artery in AP patients) bounded only by tunica adventitia and characterized by intense Colour Doppler signal, bidirectional flow (Yin and Yang sign) and a pulsating character; sometimes a partial thrombosis may be present. The diagnosis of portal system vein thrombosis is made by the presence of vein dilatation, focal Doppler signal absence in the site of thrombus, retrograde flow and, in the case of splenic artery thrombosis, spleen enlargement. An intravascular echogenic mass, corresponding to thrombus, may be detected in some cases.

TA-US is also useful to define the aetiology of AP, identifying cholecystolithiasis or choledocholithiasis. It has a sensitivity of 90%-98% for cholecystolithiasis and 50%-80% for choledocholithiasis. The lower accuracy in the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis is related to the meteorism of the hilar region and can be compensated measuring the common bile duct diameter: a calibre equal to or greater than 9 mm is suggestive for biliary stones or sludge in nearly 100% of patients with clinical signs and symptoms of AP. These features allow to refer the patients to an interventional and/or surgical treatment rather than medical treatment.

TA-US has various limitations. The quality of the examination and diagnostic accuracy are highly influenced by the experience of sonographer. Pancreas may be not visible due to abdominal meteorism or other causes up to 40% of patients or may appear normal in mild oedematous forms. Furthermore, US is not useful for distinguishing necrosis and may be very difficult, with TA-US, to identify superinfection or vascular complications. Therefore, despite the possibility of studying pancreas and the complications of AP, the main role of TA-US is to identify biliary lithiasis and fluid collections, to carry out other causes of acute abdomen in the first 48-72 hours after the onset of symptoms and to guide percutaneous drainage [

17,

23,

32,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

In recent years, various studies have evaluated the effectiveness of the contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) for the diagnosis and staging of AP. CEUS is a relatively new method with several advantages. It uses intravascular contrast media containing microbubbles, expelled with breath. These contrast media have a rate of side effects much lower than iodized or gadolinium-based contrast media and can be used in patients with renal insufficiency or allergy. Furthermore, CEUS is a real time imaging method which allow to evaluate the pancreatic perfusion as the CE-CT or MR and the presence of parenchymal necrosis. In a metanalysis on 421 cases, Fei et al. demonstrated that CEUS is better than normal TA-US and roughly equal to CECT to assess the presence of parenchymal necrosis and the severity of acute pancreatitis, in particular, when the extension of necrosis is equal to or more than 30% of pancreatic length. However, CEUS may not provide additional information in patients with an unequivocal clinical presentation, and, to date, the use of microbubbles must be considered off-label. Like grey scale US, the accuracy of CEUS is limited by bowel gas. Therefore, even though CEUS is rapid, simple, safe and not use ionizing radiation, it must be used with caution, and, to date, it cannot be considered a first line imaging modality in the evaluation of patients with AP [

42,

43].

3.2. Computed Tomography

Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CE-CT) is the modality of choice for the radiological diagnosis, staging and follow up of AP. CE-CT has several advantages including rapid image acquisition, image reconstruction systems that can improve image accuracy, high availability, quick to use and read by radiologists and clinicians, high accuracy in the evaluation of pancreatitis and its complications and the possibility of carrying out diagnostic exams even in severely ill patients and obese patients [

24,

44].

3.2.1. CT Protocol and Technical Developments

At the present, a typical pancreatic CT protocol includes a non-contrast acquisition for better diagnose calcifications, gallstones, clips and haemorrhage and a dual-phase acquisition after IV contrast medium administration at a flow rate of 3–5 mL/s. The pancreatic phase is performed 40 seconds after contrast agent injection, the portal venous phase 70 seconds after contrast-medium injection. The pancreatic phase has high accuracy in identifying pancreatic necrosis, associated tumours and peripancreatic masses, which usually show a lower enhancement rate in this phase compared to normal pancreas. The portal-venous phase allows an easier detection of venous thrombus, due to higher and more homogeneous enhancement of vessels in this phase, and improves the accuracy of CT in the detection and characterization of necrosis and associated masses (in this phase “rim-enhancement” of a WON may be more evident such as solid components or a high homogenous enhancement of pancreatic parenchyma may confirm the presence of necrotic area). A relatively new technique is the Dual Energy CT (DE-CT) which uses two separate spectra of X-ray photon energy, allowing the reconstruction of specific images from different materials with different attenuation properties at different energies. DE-CT can generate material-attenuation images, including iodine images, water-attenuation images, virtual unenhanced images and monochromatic images. Iodine images show concentration and distribution of iodine in tissues in relation to their perfusion. Therefore, DE-CT can detect pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis with a higher accuracy than standard CE-CT as well as acute haemorrhage and pseudoaneurysm. Water-attenuation or virtual unenhanced images can describe haemorrhage and debris within the parenchyma, peripancreatic fluid collections and hematomas [

45,

46].

3.2.2. Indications

An important matter of debate is the timing of performing CE-CT. The American College of radiologists (ACR), in 2019, proposed the use of CE-CT for the initial imaging of suspected acute pancreatitis with atypical signs and symptoms, for the evaluation of acute pancreatitis greater than 48-72 hours after onset of symptoms in patients who are critically ill, have systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and severe clinical scores to evaluate the presence of necrosis, which is best appreciate on CT scans after 72 hours, for the evaluation of acute pancreatitis greater than 7 to 21 days, for the evaluation of known necrotizing pancreatitis with significant deterioration of clinical status and for the evaluation of AP greater than 4 weeks after symptoms onset in patients with known pancreatic or peripancreatic fluid collections with continued abdominal paid, early satiety, nausea, vomiting or signs of infection [

43]. Other indications are to guide radiological interventions or to exclude a possible associated neoplasm [

17].

3.2.3. CT Features

The CT features of AP are related with the morphological type. The interstitial oedematous AP is characterized by the presence of enlargement of pancreas, heterogenous attenuation due to oedema, peripancreatic fat stranding or fluid effusion which may obscure the pancreatic contour and may produce a reduction of peripancreatic fat density. The inflammatory oedema may produce the ''fat renal sign'' due to increased enhancement of Gerota's fascia and pararenal space, usually in the left side [

17,

23,

46]. Around 5-10% of patients can develop necrosis as the results of thrombosis of pancreatic and/or peripancreatic microcirculation and it is detected on CT images as unenhanced or minimally enhanced hypodense areas. Necrosis involves pancreatic (mostly body and tail) and peripancreatic tissue in 75% of cases, peripancreatic tissue only in 20% of cases and pancreatic tissue only in 5% of patients. Prognosis is worst when necrosis involves pancreatic tissue [

17,

21,

23,

46,

47].

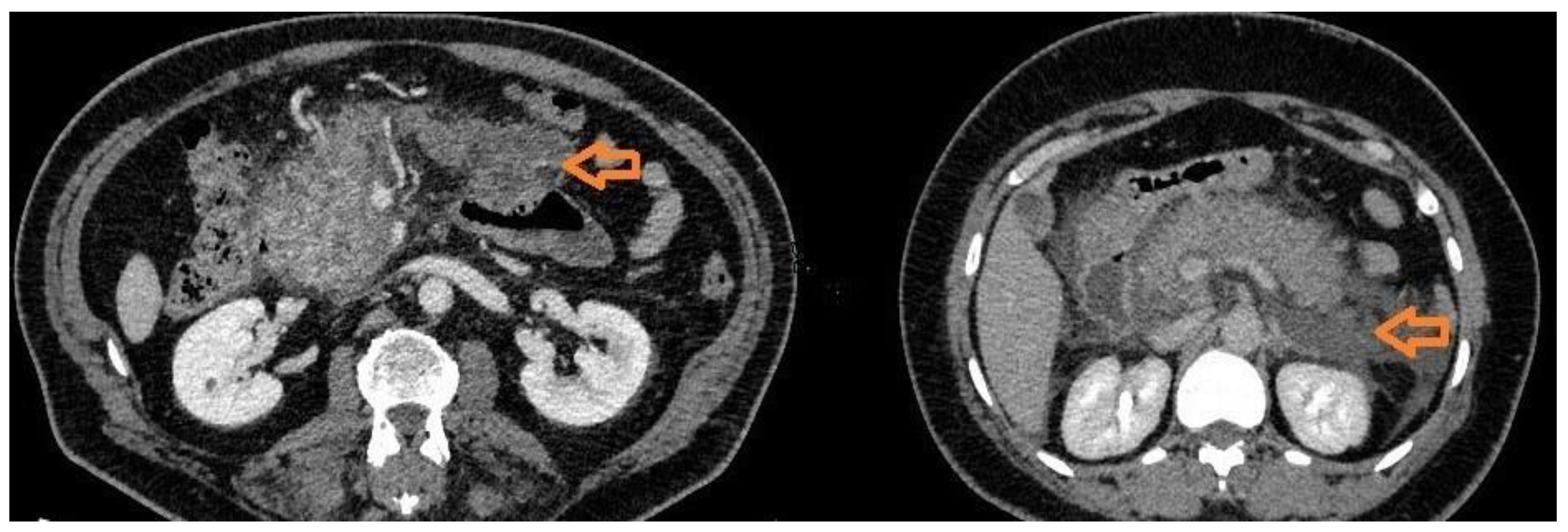

3.2.4. CT Features of Complications

CT is the gold standard technique to diagnose the presence and localization of acute complications. APFCs appear as hypodense, non-encapsulated, irregular fluid collections without or minimally enhancement. They can be single or multiple and do not involve pancreatic parenchyma. These collections are usually sterile and do not necessitate of drainage. PCs develop form APFCs after 4 weeks in 10-20% of patients. On CT scans, pancreatic PCs usually appear as circumscribed masses with fluid density and with a thin wall of 1-2 mm, with no enhancement or mild enhancement after IV contrast media injection. The wall can become thick and irregular with calcifications. Pancreatic PCs may communicate with the pancreatic duct up to 50% of cases, and the demonstration of this communications can help the management. Approximately 50% of pancreatic pseudocysts resolve spontaneously. PCs which do not resolve can complicate with infections, haemorrhage from erosion of adjacent vessels, fistulas, SIRS from rupture in abdomen or bile ducts obstruction. In these cases, percutaneous or endoscopic drainage or surgical treatment should be considered. The infection can be observed on CT images as an enlargement of the mass with thick and irregular wall with contrast enhancement, septa, fluid levels and air bubbles. Haemorrhage may be suspected when an acute extravasation of iodine contrast medium and/or a hyperdense fluid level inside the mass are detected. Fistulas are rare complications of PCs and are detected as abnormal communications, usually tubular in appearance, with peripancreatic organs and tissues, biliary tree and vessels. Intrabdominal fluid effusion and bile ducts dilatation are the CT signs of PCs rupture in abdomen and bile ducts obstructions, respectively. ANCs are the results of pancreatic an/or peripancreatic tissue necrosis. On CT images these collections can be fluid and indistinguishable from acute non necrotic collections or can contain solid necrotic debris, haemorrhage and fat, which gives a heterogeneous appearance especially after the first week allowing them to be distinguished from non-necrotic collections. These collections are usually in communication with pancreatic ducts and can be sterile or infected. If an ANC persists after 4 weeks, it evolves in WONs. On CT scans they appear usually as a large collection with thick and irregular wall (usually >3 mm with mild target-like contrast enhancement) and a partly solid component due to necrosis; furthermore, WONs are usually in communication with the pancreatic ducts. They can be infected or sterile. Infected WONs and ANCs have larger size, thicker and more irregular wall with a major degree of contrast enhancement; air bubbles can be present. As infected pseudocysts, infected necrotic collections are treated with percutaneous or endoscopic drainage or surgery. WONs can also complicate with fistulas, more frequently than PCs, and haemorrhage. (

Figure 1)

Vascular complications are also well detected on CT scans. Portal venous system thrombosis appear as a hypodense mass within a vessel, usually splenic vein. Variceal dilatations, portal hypertension and splenic infarction may be associated features. Acute arterial bleeding and pseudoaneurysms are well detected on arterial phase as contrast medium extravasation and saccular dilatation, respectively. Furthermore, a haemorrhagic collection, associated or not with acute extravasation, has usually a density, on non-contrast images, of 40-80 HU and can be easily differentiated from simple fluid collections on CT images. Haemorrhage can occur in gastrointestinal system, in peritoneal or retroperitoneal cavity, rarely in pancreatic duct (hemosuccus pancreaticus) and, as explained, in peripancreatic collections. A particular condition is when a pseudocyst envelops a visceral artery, a condition known as pseudo-aneurysmatic pseudocysts, with risk of active bleeding inside the pseudocyst. [

2,

17,

23,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56].

3.2.5. CT Based Severity Score

As a powerful and highly sensitive technique to define the presence of necrosis and complications, a severity score using CE-CT was developed by Balthazar et al. in 1994 (Table1). This score system is a 10-point severity scale, based on the degree of pancreatic inflammation and the presence of peripancreatic fluid collections and necrosis. This system has been successfully used to predict overall morbidity and mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis, allowing the clinicians to differentiate mild, moderate and severe pancreatitis. However, this score does not consider extra-pancreatic complications, did not significantly correlate with the development of organ failure and extra-pancreatic or vascular complications, is affected by a certain degree of variation in agreement between observers and, furthermore, there are no differences in survival of patients with necrosis of 30-50% and greater than 50%. Therefore, a simplified score was proposed in 2004 by Mortele et al., which allowed to obtain a higher agreement between observers, considers extravascular complications as factors affecting morbidity and mortality and considers the extent of necrosis only greater or less than 30%. This score seems to have an overall major correlation with the clinical outcome of AP [

57,

58].

3.3. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

CT is, to date, the gold standard radiological technique in the assessment of AP, being a relatively quick and fast exam, available in all centres and with an overall good accuracy in the depiction of pancreas and abdomen. However, on enhanced CT scans may be difficult to distinguish focal areas of oedema from necrosis or to identify small fluid collections or necrotic debris inside a peripancreatic mass and, for these reasons, the severity of AP may be underestimate or overestimate with CT. In this setting, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an alternative method in the study of acute pancreatitis and its complications.

3.3.1. MRI Protocol

The typical MRI protocol for the study of pancreas and abdomen in AP patients consists in T1-weighted fat-suppressed sequence single breath-hold gradient echo (GRE), T2-weighted fat-suppressed sequence with turbo spin-echo (TSE) or half Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo (HASTE), diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map, two- or three-dimensional MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) (HASTE heavily T2-weighted sequence) and fat-suppressed T1-weighted contrast-enhanced (DCE) sequences after intravenous gadolinium-based contrast-media injection with arterial, portal-venous and delayed phase at 25 s, 60 s and 180 s respectively, or dynamic fat suppressed T1 weighted contrast enhanced images lasting around 65 s using three-phase dynamic scans of 15 s each. Non-enhanced protocols, using morphological T1 and T2 weighted images and diffusion images, have been also studied, such as proposed by Tonolini et al. for mild AP in an emergency setting, with performance comparable to CE-CT or contrast enhanced MRI in diagnosis and staging of AP [

12,

18,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67].

The T2-weighted images are highly sensitive to liquid and can show, better than CT, minimal amount of fluid in oedematous pancreatitis or in the case of fluid collections. T1 and T2 weighted images are more accurate than CT in depicting haemorrhage or necrosis in pancreatic parenchyma or in peripancreatic fluid collections. Haemorrhage is usually hyperintense in T1 weighted images while necrosis is hypointense in T1 and T2 images and both are related with poorer outcomes compared to oedematous pancreatitis. Furthermore, the use of T1 and T2 sequences with fat signal suppression favours the definition of the contours of the pancreas and allow to obtain a better contrast resolution, which in turn allow a better assessment of pancreatic and peripancreatic pathological processes. The T1-weighted contrast enhanced images clearly show areas of necrosis without enhancement, with an accuracy greater than CT. Furthermore, MRCP sequences can be used to study the bile ducts without intravenous contrast media to detect bile stones in gallbladder and in the distal bile ducts, diffusion weighted sequences (DWI) can be useful to identify parenchymal areas of inflammation, solid areas within fluid collections or abscesses due to their lower degree of diffusion of the water molecules, while novel techniques as intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) allow to assess the perfusion and diffusion of the diseased tissue at the same time [

12,

18,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

68,

69,

70,

71].

3.3.2. Indications

According to ACR appropriateness criteria for acute pancreatitis, MRI of abdomen can be used in the following scenarios: 1)in the acute phase before 48-72 hours for the assessment of biliary tree with MRCP protocol; 2) in the acute phase before 48-72 hours in atypical cases; 3) in patients critically ill and with severe clinical score after 48-72 bours to assess the presence of necrosis; 4) in the follow up of fluid collections after 4 weeks; 5) in the follow up of necrotizing pancreatitis with clinical deterioration; 6) in the case of continued SIRS, severe clinical scores, leucocytosis, and fever, greater than 7 to 21 days after onset of symptoms. In all cases, except for the first and fifth scenarios, ACR recommends a full protocol with and without injection of intravenous gadolinium-based contrast media and MRCP [

43].

Besides this indications, MRI can be used in patients with iodine allergy and, due to the absence of ionizing radiation and the overall accuracy of non-enhanced protocols, in patients with renal insufficiency and in pregnant women (18,60, 66).Therefore, MRI may be used after the 4th week from onset when invasive intervention is considered because the contents (liquid vs. solid) of pancreatic collections are better characterized by MRI and evaluation of pancreatic duct integrity is possible [

72].

3.3.3. MRI Features

The MRI features of interstitial oedematous pancreatitis are related with the inflammatory oedema of the parenchyma. The gland appears usually enlarged (defined by an antero-posterior diameter equal to or greater than 3 cm) with focal or diffuse hypointensity on T1 weighted images and hyperintensity on T2 images. DWI usually shows a restriction of diffusion associated with areas of inflammation. T1 weighted contrast enhanced images show a homogeneous or slightly heterogeneous contrast enhancement of the gland. T2 weighted images and DWI images can detect associated peripancreatic areas of oedema. Necrotizing pancreatitis is best appreciated with MRI. Necrotic areas usually are hypointense on T1 and T2 weighted images (necrosis may be hyperintense in T2 images if liquified), with absent or very low enhancement after gadolinium injection. DWI images show an increase in ADC value due to membrane cell rupture and increase of diffusion of water molecules. As CE-CT, necrosis is better detected after 72 hours and areas of absent contrast uptake identified early must be monitored to confirm their necrotic nature while any similar areas identified after the first week should be considered necrotic. CE-MRI with MRCP sequences is the modality of choice in assessing the status of the pancreatic duct in necrotizing pancreatitis. Rupture of the duct can be another indicator of the severity of acute pancreatitis [

18,

23,

59,

67,

68] (

Figure 2).

3.3.4. MRI Features of Complications

APFCs appear as irregular fluid collections that are hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2 images. PCs appear as collections with hyperintense signal on T2 sequences and with a 1-2 mm wall with mild or no contrast enhancement. ANCs and WONs are necrotic collections which can be differentiated from non-necrotic collections by the presence of solid component which are hypointense on T1 and T2 images, with lower diffusion coefficient than fluid and mild or no enhancement. However, if the solid component is too small, MRI is less accurate in distinguishing necrotic collections from non-necrotic collections. Infected PCs and infected ANCs or WONs can be appreciate by the presence of thicker and irregular wall with a higher contrast enhancement. Furthermore, inflammation can lead to an increase in density and in non-fluid components within these masses, resulting in a reduction in T2 intensity, while the formation of a true abscess can cause a marked restriction of the diffusion of water molecules on DWI images. Fistulas secondary to PCs and more frequently WONs are detected on MRI images as abnormal communications, with peripancreatic organs, tissues and vessels, hypointense in T1, hyperintense in T2, with parietal enhancement after gadolinium administration. MRCP images can also help in detecting fistulas as a markedly hyperintense, abnormal, tubular tract. MRI can detect vascular complications. Vascular thrombosis appears as a loss of the normal void signal within a vessel replaced by a focal mass in T1 and T2 weighted images. After gadolinium injection, the thrombus did not enhance or enhance slightly. Haemorrhage and haemorrhagic collections, related or not with peripancreatic collections, can be detected in the acute and subacute period as T1 hyperintense areas while acute bleeding can be appreciated as extravasation of gadolinium. Pseudoaneurysms are also well identified after gadolinium injection as saccular dilatation of a vessel [

23,

65,

66,

69].

3.3.5. MRI Severity Score

As CE-CT, an MRI severity score (MR-SI) was developed. This score, derived from CT-SI, evaluates the severity of AP by integrating pancreatic and peripancreatic inflammation and/or fluid collections with pancreatic parenchymal necrosis. In general, MR-SI it proved to be better than APACHE II clinical score in assessing local complications, while APACHE II demonstrated better in determining systemic complications. Furthermore, MR-SI is comparable to CT-SI in defining the severity of AP, essential for the initial assessment of AP using MRI images and it correlates well with the overall clinical outcome [

18,

73,

74,

75].

4. Discussion, Future Directions and Conclusion

Acute pancreatitis is one of the main causes of admission to the emergency room for abdominal pathology. Although the diagnosis is based on clinical and laboratory data, imaging plays an essential role in diagnosis, staging and definition of the severity of AP in the acute phase and in the follow up period, especially in severe cases [

76,

77,

78]. US is the first line technique, useful to detect the presence of gallstones and to exclude other causes of abdominal pain but has limited accuracy regarding the evaluation of the pancreatic parenchyma. CE-CT is currently the gold standard technique for a correct assessment of AP. CE-CT is fast, widespread and easy to read with an overall high accuracy in the diagnosis of AP and in the identification of necrosis and complications [

79,

80]. MRI shows an accuracy equal to or greater than CE-CT in the diagnosis of AP and in the assessment of its severity. MRI is the most sensitive technique to detect intraparenchymal and peripancreatic oedema, necrosis and haemorrhagic components. Furthermore, using MRCP protocol, gallstones can be easily identified both in the gallbladder and in the distal bile ducts [

81].

In summary, in the clinical practice, according to ACR appropriateness criteria as reported, US of abdomen is usually appropriate for the initial imaging of suspected acute pancreatitis presenting for the first time with epigastric pain and increased amylase and lipase before 48 to 72 hours after symptom onset. CE-CT of abdomen and CE-MRI of abdomen with MRCP are usually appropriate for the initial imaging of suspected acute pancreatitis with atypical signs and symptoms including equivocal amylase and lipase values and when diagnoses other than pancreatitis may be possible (such as bowel diseases); for the evaluation of acute pancreatitis greater than 48 to 72 hours after onset of symptoms in patients who are critically ill, have SIRS or severe clinical scores to evaluate the presence of pancreatic and/or peripancreatic necrosis; for the evaluation of acute pancreatitis greater than 7 to 21 days after the onset of symptoms in patients with continued SIRS, severe clinical scores, leucocytosis and fever; for the evaluation of known necrotizing pancreatitis in patients with significant clinical deterioration. CE-CT and CE-MRI are complementary and can be used either individually or in succession (usually MRI is used as an in-depth analysis if necessary after CT) based on the information that each of them can provide, the clinical condition of the patient (for example impossibility of performing an MRI due to pacemaker, metal implants or claustrophobia; impossibility to perform CE-CT due to iodine allergy or pregnancy), the techniques available in the institution and the clinical context, considering that in the emergency setting it is often difficult to use MRI as a first or second level examination after US, despite its higher accuracy and the abbreviated and non-enhanced protocols proposed in the last years. CE-CT is also usually the modality of choice to guide percutaneous interventions and to characterize the target such as fluid collections or haemorrhage; however, CE-MRI may be used for a better characterization of fluid collections or the pancreatic duct status after 4 weeks if an invasive procedure is required [

43,

72].

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) models are revolutionizing the approach to medicine and its future developments. Machine learning and deep learning models offer a highly precise system for managing clinical problems, allowing the identification of specific therapeutic and diagnostic paths for each patient. Various studies have proposed automated algorithms and methods for the diagnosis and the definition of the severity of AP as well as for predicting the risk of evolution into more severe forms or the risk of recurrence [

82]. Zhang C. et al. developed a deep learning model based on CE-CT images, considering both pancreatic parenchyma and peripancreatic changes. This model exhibits an excellent performance in defining the severity of AP. Bette et al proposed a segmentation model based on CE-CT images which allow to obtain an accuracy in the diagnosis of AP comparable with the diagnostic performance of serum lipase level. Excellent performances in diagnosis and staging of AP were also obtained using MRI images. Qiao et al., using a MRI portal-venous phase model, obtained good results in the evaluation of the severity of AP, while Tartari et al. obtained high accuracy in the diagnosis of AP using T2 weighted images, In particular, in this study, the accuracy based on T2 weighted images was superior than models based on CE-CT images and on non-contrast and portal-venous phase T1 weighted images. (82,83,84, 85). All these initial experiences in the field of AI applied to the diagnosis and staging of acute pancreatitis demonstrate high levels of performance of the software currently used, even superior to an expert radiologist. However, multicentre, prospective and randomized studies on a larger population are needed to obtain a real clinical application of AI models for the study of AP, considering the emergency context and the need to combine the radiological data with clinical outcomes [

86,

87].

From a clinical point of view, recent advances had changed the common view of AP. AP is now regarded as a dynamic process in which systemic involvement is the main determinant of outcome. The therapeutic approach is more conservative than in the past and the endoscopic and radiological treatments have acquired a relevant role while the surgical approach is currently used exclusively in the treatment of complicated cases in which endoscopic or interventional attempts are inconclusive on not possible such as selected cases suitable for surgical necrosectomy, surgical drainage of fluid collections or surgical treatment of haemorrhage [

26,

88,

89].

In conclusion, AP is a common condition that can vary in severity at presentation or evolve into more severe forms over the course of few days. In this context, the correct definition of the severity of AP in the initial phase and the early identification of complications allow to identify patients with a worse prognosis who need more severe treatment and prolonged hospitalization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.E. and B.G.; writing—original draft preparation: B.G. and A.E.; review and editing: M.F., G.S., B.L., B.F., C.E., Di M.L., P.N., S.F; supervision: A.E. and S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bradley, E.L. A Clinically Based Classification System for Acute Pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, GA, September 11–13, 1992. 1993, 128, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, B.C.; Chinogureyi, A.; Shaw, A.S. Imaging acute pancreatitis. Br. J. Radiol. 2010, 83, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannuzzi, J.P.; King, J.A.; Leong, J.H.; Quan, J.; Windsor, J.W.; Tanyingoh, D.; Coward, S.; Forbes, N.; Heitman, S.J.; Shaheen, A.-A.; et al. Global Incidence of Acute Pancreatitis Is Increasing Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. P. Iannuzziet al., “Global Incidence of Acute Pancreatitis Is Increasing Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology, vol. 162, no. 1, pp. 122–134, Jan. 2022.

- Petrov, M.S.; Yadav, D. Global epidemiology and holistic prevention of pancreatitis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanier, B.; Dijkgraaf, M.; Bruno, M. Epidemiology, aetiology and outcome of acute and chronic pancreatitis: An update. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2008, 22, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawla, P.; Bandaru, S.S.; Vellipuram, A.R. Review of Infectious Etiology of Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterol. Res. 2017, 10, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, B.; Gougol, A.; Gao, X.; Reddy, N.; Talukdar, R.; Kochhar, R.; Goenka, M.K.; Gulla, A.; Gonzalez, J.A.; Singh, V.K.; et al. Worldwide Variations in Demographics, Management, and Outcomes of Acute Pancreatitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 18, 1567–1575.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R.; Smith, A.; Sutton, R. Covid-19-related pancreatic injury. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, e190–e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, F.U.; Laemmerhirt, F.; Lerch, M.M. Etiology and Risk Factors of Acute and Chronic Pancreatitis. Visc. Med. 2019, 35, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.S.; Shelat, V.G. Diagnosis, severity stratification and management of adult acute pancreatitis–current evidence and controversies. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2022, 14, 1179–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 Sep;108(9):1400-15; 1416.

- Arvanitakis, M.; Dumonceau, J.-M.; Albert, J.; Badaoui, A.; Bali, M.A.; Barthet, M.; Besselink, M.; Deviere, J.; Ferreira, A.O.; Gyökeres, T.; et al. Endoscopic management of acute necrotizing pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines. Endoscopy 2018, 50, 524–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, S.G.; Habtezion, A.; Gukovskaya, A.; Lugea, A.; Jeon, C.; Yadav, D.; Hegyi, P.; Venglovecz, V.; Sutton, R.; Pandol, S.J. Critical thresholds: key to unlocking the door to the prevention and specific treatments for acute pancreatitis. Gut 2020, 70, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radulova-Mauersberger O, Belyaev O, Birgin E, Bösch F, Brunner M, Müller-Debus CF, et al. Indications for surgical and interventional therapy of acute pancreatitis. Zentralbl Chir 2020; 145: 374–82.

- Gapp J, Hall AG, Walters RW, et al. Trends and Outcomes of Hospitalizations Related to Acute Pancreatitis: Epidemiology From 2001 to 2014 in the United States. Pancreas. 2019; 48:548–554.

- Türkvatan A, Erden A, Türkoğlu MA, Seçil M, Yener Ö. Imaging of acute pancreatitis and its complications. Part 1: acute pancreatitis. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015 Feb;96(2):151-60.

- Sun, H.; Zuo, H.-D.; Lin, Q.; Yang, D.-D.; Zhou, T.; Tang, M.-Y.; Wáng, Y.X.J.; Zhang, X.-M. MR imaging for acute pancreatitis: the current status of clinical applications. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 269–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memiş, A.; Parıldar, M. Interventional radiological treatment in complications of pancreatitis. Eur. J. Radiol. 2002, 43, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenner, S.; Vege, S.S.; Sheth, S.G.; Sauer, B.; Yang, A.; Conwell, D.L.; Yadlapati, R.H.; Gardner, T.B. American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines: Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 119, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, P.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Dervenis, C.; Gooszen, H.G.; Johnson, C.D.; Sarr, M.G.; Tsiotos, G.G.; Vege, S.S.; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: Revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut 2013, 62, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillip, V.; Steiner, J.M.; Algül, H. Early phase of acute pancreatitis: Assessment and management. World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiol. 2014, 5, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brizi, M.G.; Perillo, F.; Cannone, F.; Tuzza, L.; Manfredi, R. The role of imaging in acute pancreatitis. La Radiol. medica 2021, 126, 1017–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppäniemi, A.; Tolonen, M.; Tarasconi, A.; Segovia-Lohse, H.; Gamberini, E.; Kirkpatrick, A.W.; Ball, C.G.; Parry, N.; Sartelli, M.; Wolbrink, D.; et al. 2019 WSES guidelines for the management of severe acute pancreatitis. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2019, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.H.Ranson. Etiological and prognostic factors in human acute pancreatitis: a review. Am J Gastroenterol 77 (1982), pp. J.H.Ranson. Etiological and prognostic factors in human acute pancreatitis: a review. Am J Gastroenterol 77 (1982), pp.633-638.

- Italian Association for the Study of the Pancreas (AISP); Pezzilli R, Zerbi A, Campra D, Capurso G, Golfieri R, Arcidiacono PG, Billi P, Butturini G, Calculli L, Cannizzaro R, Carrara S, Crippa S, De Gaudio R, De Rai P, Frulloni L, Mazza E, Mutignani M, Pagano N, Rabitti P, Balzano G. Consensus guidelines on severe acute pancreatitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2015 Jul;47(7):532-43.

- Capurso, G.; Pisani, R.P.d.L.; Lauri, G.; Archibugi, L.; Hegyi, P.; Papachristou, G.I.; Pandanaboyana, S.; Maisonneuve, P.; Arcidiacono, P.G.; De-Madaria, E. Clinical usefulness of scoring systems to predict severe acute pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis with pre and post-test probability assessment. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2023, 11, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaus, W.A.; Draper, E.A.; Wagner, D.P.; Zimmerman, J.E. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Crit. Care Med. 1985, 13, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y.; Fang, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X. Predictive value of the Ranson and BISAP scoring systems for the severity and prognosis of acute pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0302046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.S.; Shelat, V.G. Diagnosis, severity, stratification and management of adult acute pancreatitis-current evidence and controversies. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2022, 14, 1179–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, Y.; Shelat, V.G. Ranson score to stratify severity in Acute Pancreatitis remains valid – Old is gold. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 15, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerem, E. Treatment of severe acute pancreatitis and its complications. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 13879–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, N.J.; Bakker, O.J.; Besselink, M.G.; Ali, U.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Gooszen, H.G.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Bruno, M.J. Impact of characteristics of organ failure and infected necrosis on mortality in necrotising pancreatitis. Gut 2018, 68, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komara, N.L.; Paragomi, P.; Greer, P.J.; Wilson, A.S.; Breze, C.; Papachristou, G.I.; Whitcomb, D.C. Severe acute pancreatitis: capillary permeability model linking systemic inflammation to multiorgan failure. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2020, 319, G573–G583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. I. K. A. S. R. Brindise E, “Temporal Trends in Incidence and Outcomes of Acute Pancreatitis in Hospitalized Patients in the United States From 2002 to 2013.,” Pancreas, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 169–175, Feb. 2019.

- D.Bhakta, R. D.Bhakta, R. de Latour, and L. Khanna, “Management of pancreatic fluid collections, Translational Gastroenterology and Hepatology, vol. 7. AME Publishing Company, Apr. 01, 2022.

- Z. Liu, H. Z. Liu, H. Ke, Y. Xiong, H. Liu, M. Yue, and P. Liu, “Gastrointestinal Fistulas in Necrotizing Pancreatitis Receiving a Step-Up Approach Incidence, Risk Factors, Outcomes and Treatment, J Inflamm Res, vol. 16, pp. 5531–5543, 2023.

- Badea, R. Ultrasonography of acute pancreatitis -- an essay in images. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2005, 14, 83–9. [Google Scholar]

- Azzo, C.; Driver, L.; Clark, K.T.; Shokoohi, H. Ultrasound Assessment of Postprocedural Arterial Pseudoaneurysms: Techniques, Clinical Implications, and Emergency Department Integration. Cureus 2023, 15, e43527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connor OJ, McWilliams S, Maher MM. Imaging of acute pancreatitis.AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011 Aug;197(2): W221-5.

- Burrowes, D.P.; Choi, H.H.; Rodgers, S.K.; Fetzer, D.T.; Kamaya, A. Utility of ultrasound in acute pancreatitis. Abdom. Imaging 2019, 45, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougard, M.; Barbier, L.; Godart, B.; Le Bayon-Bréard, A.-G.; Marques, F.; Salamé, E. Management of biliary acute pancreatitis. J. Visc. Surg. 2019, 156, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal Imaging; Porter KK, Zaheer A, Kamel IR, Horowitz JM, Arif-Tiwari H, Bartel TB, Bashir MR, Camacho MA, Cash BD, Chernyak V, Goldstein A, Grajo JR, Gupta S, Hindman NM, Kamaya A, McNamara MM, Carucci LR. ACR Appropriateness Criteria Acute Pancreatitis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019 Nov;16(11S): S316-S330.

- Bollen, Thomas L. Imaging Assessment of Etiology and Severity of Acute Pancreatitis. Pancreapedia: Exocrine Pancreas Knowledge Base (2016).

- Almeida, R.R.; Lo, G.C.; Patino, M.; Bizzo, B.; Canellas, R.; Sahani, D.V. Advances in Pancreatic CT Imaging. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2018, 211, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connor OJ, McWilliams S, Maher MM. Imaging of acute pancreatitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011 Aug;197(2): W221-5.

- Türkvatan A, Erden A, Türkoğlu MA, Seçil M, Yüce G. Imaging of acute pancreatitis and its complications. Part 2: complications of acute pancreatitis. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015 Feb;96(2):161-9.

- Balthazar, E.J. Complications of acute pancreatitis: Clinical and CT evaluation. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 2002, 40, 1211–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, K.P.; O'Connor, O.J.; Maher, M.M. Updated Imaging Nomenclature for Acute Pancreatitis. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2014, 203, W464–W469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao K, Adam SZ, Keswani RN, Horowitz JM, Miller FH.AJR Acute Pancreatitis: Revised Atlanta Classification and the Role of Cross-Sectional Imaging Am J Roentgenol. 2015 Jul;205(1): W32-41.

- Anis, F.S. ∙ Adiamah, A. ∙ Lobo, D.N. Sanyal S. Incidence and treatment of splanchnic vein thrombosis in patients with acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wolbrink, D.; Kolwijck, E.; Oever, J.T.; Horvath, K.; Bouwense, S.; Schouten, J. Management of infected pancreatic necrosis in the intensive care unit: a narrative review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 26, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.; Bellizzi, S.; Badas, R.; Canfora, M.L.; Loddo, E.; Spada, S.; Khalaf, K.; Fugazza, A.; Bergamini, S. Direct Endoscopic Necrosectomy: Timing and Technique. Medicina 2021, 57, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantarojanasiri, T.; Ratanachu-Ek, T.; Isayama, H. When Should We Perform Endoscopic Drainage and Necrosectomy for Walled-Off Necrosis? J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattarapuntakul, T.; Charoenrit, T.; Wong, T.; Netinatsunton, N.; Ovartlarnporn, B.; Yaowmaneerat, T.; Tubtawee, T.; Boonsri, P.; Sripongpun, P. Clinical Outcomes of the Endoscopic Step-Up Approach with or without Radiology-Guided Percutaneous Drainage for Symptomatic Walled-Off Pancreatic Necrosis. Medicina 2023, 59, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.H.; Chin, W.; Shaikh, A.L.; Zheng, S. Pancreatic pseudocyst: Dilemma of its recent management (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 21, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortele, K.J.; Wiesner, W.; Intriere, L.; Shankar, S.; Zou, K.H.; Kalantari, B.N.; Perez, A.; Vansonnenberg, E.; Ros, P.R.; Banks, P.A.; et al. A Modified CT Severity Index for Evaluating Acute Pancreatitis: Improved Correlation with Patient Outcome. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2004, 183, 1261–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuwanshi S, Gupta R, Vyas MM, Sharma R. CT Evaluation of Acute Pancreatitis and its Prognostic Correlation with CT Severity Index. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016 Jun;10(6):TC06-11.

- Vacca, G.; Reginelli, A.; Urraro, F.; Sangiovanni, A.; Bruno, F.; Di Cesare, E.; Cappabianca, S.; Vanzulli, A. Magnetic resonance severity index assessed by T1-weighted imaging for acute pancreatitis: correlation with clinical outcomes and grading of the revised Atlanta classification—a narrative review. Gland. Surg. 2020, 9, 2312–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loic Viremouneix, Olivier Monneuse, Guillaume Gautier, Laurent Gruner, Roch Giorgi, Bernard Allaouchiche, Frank Pilleul, Prospective evaluation of nonenhanced MR imaging in acute pancreatitis J Magn Reson Imaging 2007 Aug;26(2):331-8.

- Akash Bansal,Rajath Ramegowda, Pankaj Gupta,Jimil Shah,Jayanta Samanta,Harshal Mandavdhare,Vishal Sharma,Rakesh Kochhar,Manavjit Singh SandhuAbbreviated non-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2022 Jul;47(7):2381-2389.

- Štimac, D.; Miletić, D.; Radić, M.; Krznarić, I.; Mazur-Grbac, M.; Perković, D.; Milić, S.; Golubović, V. The Role of Nonenhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Early Assessment of Acute Pancreatitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 102, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonolini, M.; Di Pietro, S. Diffusion-weighted MRI: new paradigm for the diagnosis of interstitial oedematous pancreatitis. Gland. Surg. 2019, 8, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, B.; Xu, H.-B.; Jiang, Z.-Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.-M. Current concepts for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis by multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2019, 9, 1973–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirkes, T.; Menias, C.O.; Sandrasegaran, K. MR Imaging Techniques for Pancreas. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 2012, 50, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikpanah, M.; Morgan, D.E. Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation and management of acute pancreatitis: a review of current practices and future directions. Clin. Imaging 2024, 107, 110086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.-J.; Xiao, B. Acute pancreatitis: Structured report template of magnetic resonance imaging. World J. Radiol. 2023, 15, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin de Freitas Tertulino, Vladimir Schraibman, Jose´ Celso Ardengh, Danilo Cerqueira do Espı´rito-Santo, Sergio Aron Ajzen, Franz Robert Apodaca Torrez, Edson Jose Lobo, Jacob Szejnfeld, Suzan Menasce Goldman. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging indicates the severity of acute pancreatitis. Abdom Imaging. 2015 Feb;40(2):265-71.

- Miller, F.H.; Keppke, A.L.; Dalal, K.; Ly, J.N.; Kamler, V.-A.; Sica, G.T. MRI of Pancreatitis and Its Complications: Part 1, Acute Pancreatitis. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2004, 183, 1637–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghandili, S. ∙ Shayesteh, S. ∙ Fouladi, D.F., Blanco A., Chu L. Emerging imaging techniques for acute pancreatitis. Abdominal Radiology. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sandrasegaran, K. ∙ Heller, M.T. ∙ Panda, A. Shetty A., Menias O C. MRI in acute pancreatitis Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis, M.; Dumonceau, J.-M.; Albert, J.; Badaoui, A.; Bali, M.A.; Barthet, M.; Besselink, M.; Deviere, J.; Ferreira, A.O.; Gyökeres, T.; et al. Endoscopic management of acute necrotizing pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines. Endoscopy 2018, 50, 524–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Zhang, X.M.; Xiao, B.; Zeng, N.L.; Pan, H.S.; Feng, Z.S.; Xu, X.X. Magnetic resonance imaging versus Acute Physiology And Chronic Healthy Evaluation II score in predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis. Eur. J. Radiol. 2011, 80, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.-X. ∙ Zhao, C.-F. ∙ Wang, S.-L, Tu X-Y, Huang W-B,Chen J-N,Xie Y,Chen C-R. Acute pancreatitis: a review of diagnosis, severity prediction and prognosis assessment from imaging technology, scoring system and artificial intelligence World J Gastroenterol. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis, M.; Delhaye, M.; De Maertelaere, V.; Bali, M.; Winant, C.; Coppens, E.; Jeanmart, J.; Zalcman, M.; Van Gansbeke, D.; Devière, J.; et al. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2004, 126, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens KJ, Lisanti C. Pancreas imaging. In: StatPearls [Internet]. FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Baeza-Zapata, A.A. , García-Compeán D., Jaquez-Quintana J.O., Scharrer-Cabello S.I., Del Cueto-Aguilera Á.N., Maldonado-Garza H.J. Acute pancreatitis in elderly patients. Gastroenterology. 2021; 161:1736–1740.

- R. H. G. MD. Mederos MA, “Acute Pancreatitis: A Review., JAMA, vol. 325, no. 4, pp. 382–390, 2021.

- Polanco Amesquita VC, Larrañaga N, Espil G, Romualdo JE, Prado F, Kozima S. Findings of acute pancreatitis complications on CT.Revista Argentina de Radiologia. 2021;85(2):41-45.

- Willis J, van Sonnenberg E.Updated Review of Radiologic Imaging and Intervention for Acute Pancreatitis and Its ComplicationsJ Intensive Care Med. 2024 Feb.

- Ni, Y.-H.; Song, L.-J.; Xiao, B. Magnetic resonance imaging for acute pancreatitis in type 2 diabetes patients. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 7268–7276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Peng, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Sun, M.-W.; Jiang, H. A deep learning-powered diagnostic model for acute pancreatitis. BMC Med Imaging 2024, 24, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bette, S.; Canalini, L.; Feitelson, L.-M.; Woźnicki, P.; Risch, F.; Huber, A.; Decker, J.A.; Tehlan, K.; Becker, J.; Wollny, C.; et al. Radiomics-Based Machine Learning Model for Diagnosis of Acute Pancreatitis Using Computed Tomography. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartari, C.; Porões, F.; Schmidt, S.; Abler, D.; Vetterli, T.; Depeursinge, A.; Dromain, C.; Violi, N.V.; Jreige, M. MRI and CT radiomics for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Eur. J. Radiol. Open 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Ji, Y.; Chen, Y.; Sun, H.; Yang, D.; Chen, A.; Chen, T.; Zhang, X.M. Radiomics model of contrast-enhanced MRI for early prediction of acute pancreatitis severity. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2019, 51, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan G, Yan G, Li H, Liang H, Peng C, Bhetuwal A, McClure MA, Li Y, Yang G, Li Y, Zhao L, Fan X. Radiomics and Its Applications and Progress in Pancreatitis: A Current State of the Art Review.Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Jun 23; 9:922299.

- Jingyu Zhong, Yangfan Hu,Yue Xing,Xiang Ge,,Defang Ding,Huan Zhang,Weiwu Yao. A systematic review of radiomics in pancreatitis: applying the evidence level rating tool for promoting clinical transferabilityInsights Imaging.2022 Aug 20;13(1):139.

- Rahnemai-Azar, A.A.; Sutter, C.; Hayat, U.; Glessing, B.R.; Ammori, J.; Tavri, S. Multidisciplinary Management of Complicated Pancreatitis: What Every Interventional Radiologist Should Know. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2021, 217, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzerwi, N. Surgical management of acute pancreatitis: Historical perspectives, challenges, and current management approaches. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 15, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).