Submitted:

26 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

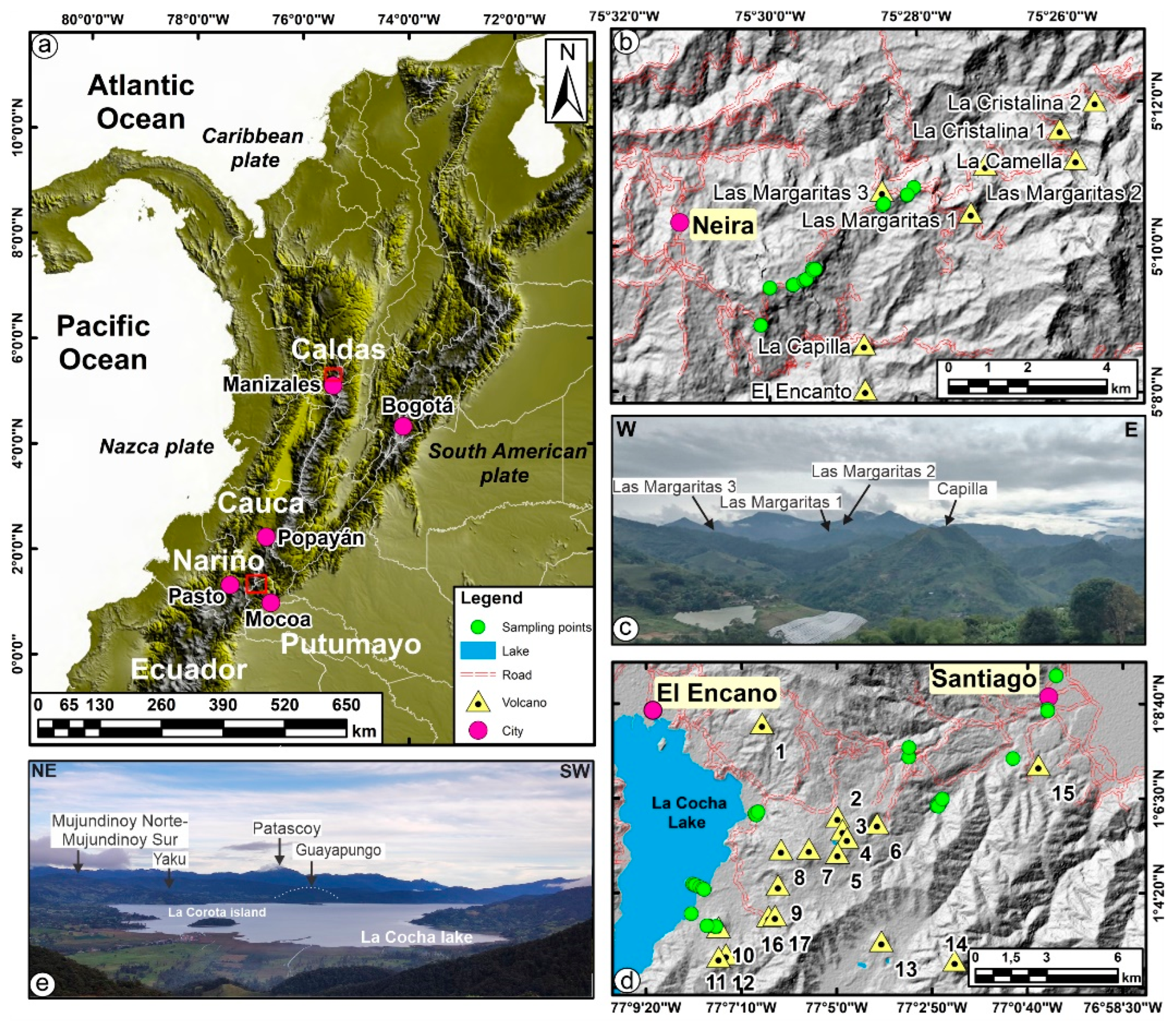

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Physicochemical properties of Andisol soils

2.1.1. Physical properties of Andisol soils.

2.1.2. Chemical properties of Andisol soils.

2.2. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical properties of Andisol soils

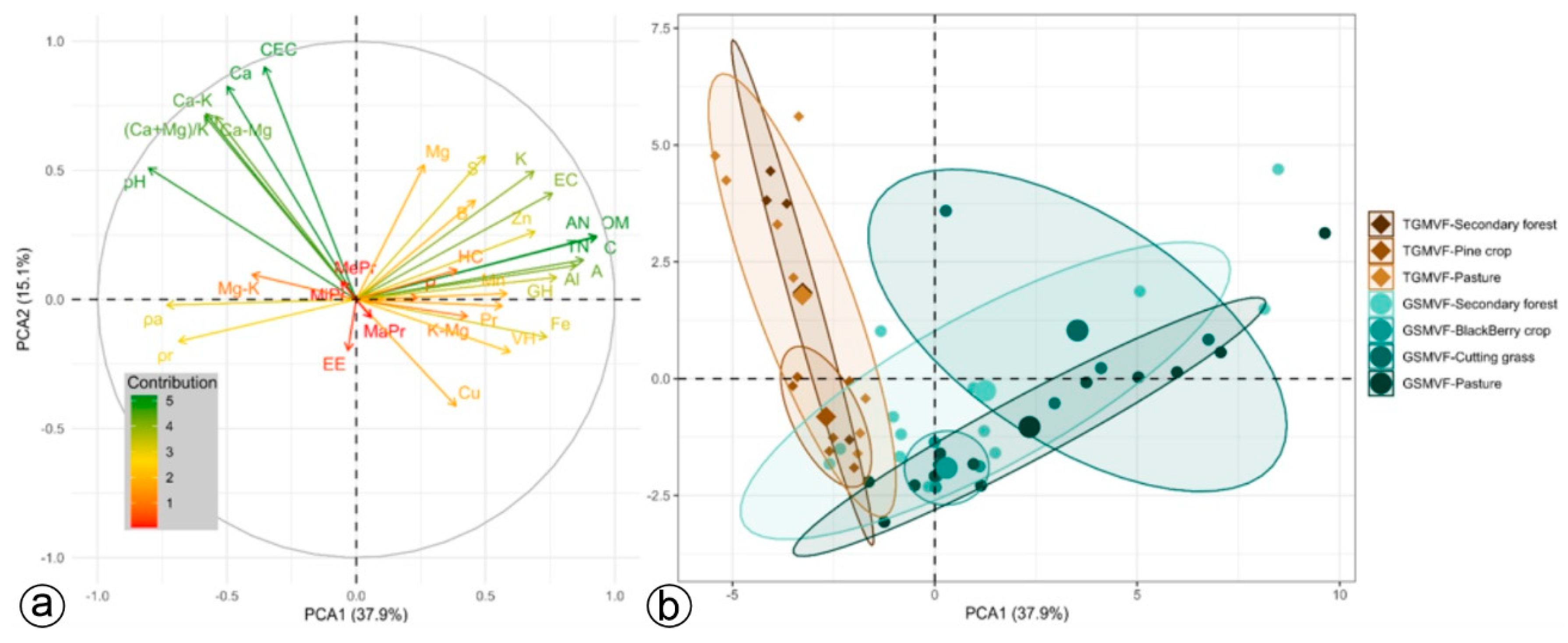

3.3. Multivariate statistical analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Physical properties

4.2. Chemical properties

4.2.1. Association of soil chemistry with parent material.

4.2.2. Acidification.

4.2.3. Contrast of chemical variables

4.3. Impact of major components on nutrient distribution.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soil Survey Staff (1999) Soil taxonomy. Second edition (USDA NRCS & Agriculture Handbook, Eds.; Second edition). [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, R.A., Saigusa, M., Ugolini, F.C. (2004) The Nature, Properties and Management of Volcanic Soils. Advances in Agronomy, 82, 113–182. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.G., Lambert, J.J., Nanzyo, M., Dahlgren, R.A. (2017) Soil genesis and mineralogy across a volcanic lithosequence. Geoderma, 285, 301–312. [CrossRef]

- Nanzyo, M. (2003) Unique Properties of Volcanic Ash Soils. Global Environmental Research-English Edition, 6(2), 99–112.

- Delmelle, P., Opfergelt, S., Cornelis, J.T., Ping, C.L. (2015) Volcanic Soils. The Encyclopedia of Volcanoes, 1253–1264. [CrossRef]

- Echeverri, T.L., Estévez, V.J.V., Bedoya, P.J.G. (2014) Caracterización física, química y mineralógica de suelos con vocación forestal protectora región Andina Central Colombiana. Revista Facultad Nacional de Agronomía Medellín , 67 (2), 7335–7343. [CrossRef]

- Saigusa, M.F., Shoji, S., Nakaminami, H. (1987) Measurement of water retention at 15 bar tension by pressure membrane method and available moisture of andosols. Japanese Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 58(3).

- Takahashi, T., Dahlgren, R.A. (2016) Nature, properties and function of aluminum–humus complexes in volcanic soils. Geoderma, 263, 110–121. [CrossRef]

- Valle, S.R., Carrasco, J. (2018) Soil quality indicator selection in Chilean volcanic soils formed under temperate and humid conditions. Catena, 162, 386–395. [CrossRef]

- Lobos-Ortega, I., Alfaro-Valenzuela, M., Martínez-Lagos, J., Pavez-Andrades, P. (2021) Chemical characterization of volcanic soils using near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). Chilean J. Agric. Anim. Sci., Ex Agro-Ciencia, 37(1), 32–42. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T., Shoji, S. (2001) Distribution and classification of volcanic ash soil. Global Enviornmental Research, Volcanic Ashes and Cheir Soils, 6(2), 83–98.

- Torres, D., Rodríguez, N., Yendis, H., Florentino, A., Zamora, F. (2006) Cambios en algunas propiedades químicas del suelo según el uso de la tierra en el sector el Cebollal, Estado Falcon, Venezuela. Bioagro, 18(2), 123–128.

- Jaurixje, M., Torres, D., Mendoza, B., Henríquez, M., Contreras, J. (2013) Propiedades físicas y químicas del suelo y su relación con la actividad biológica bajo diferentes manejos en la zona de Quíbor, Estado Lara. Bioagro, 25(1), 47–56.

- Morgan, R.P.C. (1986) Soil Erosion and Conservation. Longman Scientific and Technical, New York.

- Sánchez, E.J.A., Rubiano, S.Y. (2015) Procesos específicos de formación en Andisoles, Alfisoles y Ultisoles en Colombia. Revista EIA, SPE2, 85–97.

- Buol, S.W., Southard, R.J., Graham, R.C., McDaniel, P.A. (2011) Soil Genesis and Classification: Sixth Edition. Soil Genesis and Classification: Sixth Edition. [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Pedraza, E.A. (2005) Los suelos de Colombia y sus estadísticas más recientes. Análisis Geográficos, 29, 13–21.

- Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi (2012) Colombia, un país con una diversidad de suelos ignorada y desperdiciada. https://igac.gov.co/es/noticias/colombia-un-pais-con-una-diversidad-de-suelos-ignorada-y-desperdiciada.

- Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi (2014) Mapa Digital de Suelos del Departamento de Nariño, República de Colombia. Escala 1:100.000.

- IUSS Working Group, W.R.B. (2006) World reference base for soil resources 2006: a framework for international classification, correlation and communication. In World Soil Resources Reports No. 103. FAO.

- Vargas-Arcila, L., Murcia, H., Osorio-Ocampo, S., Sánchez-Torres, L., Botero-Gómez, L.A., Bolaños-Cabrera, G. (2023) Effusive and evolved monogenetic volcanoes: two newly identified (~ 800 ka) cases near Manizales City, Colombia. Bulletin of Volcanology, 85(7), 42. [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Orobio, L.T., Chapuel-Cuasapud, D.L., Botero-Gómez, L.A., Murcia, H. (2024) Análisis morfo-estructural del Campo Volcánico Monogenético Guamuéz-Sibundoy (sur de Colombia). Geofísica Internacional, 63(4).

- Arias-Díaz, A., Murcia, H., Vallejo-Hincapié, F., Németh, K. (2023) Understanding Geodiversity for Sustainable Development in the Chinchiná River Basin, Caldas, Colombia. Land, 12(11). [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Sabogal, J.E., García-Portilla, J., Forero-Amaya, J.C., Castro-Robledo, I., Canal-Albán, F.J., Rojas-Orjuela, D.R.., Carrizosa-Umaña, J., Guerrero-Barrios, V., Montealegre-Bocanegra, J.E., Rodríguez-Roa, A., Martínez-Chaparro, C.A., Espejo, Ó.J., Guio, A.D. (2014) Bogotá y Cundinamarca frente al cambio climático: plan regional integral de cambio climático región capital, Bogotá Cundinamarca: síntesis estratégica del proceso y principales resultados. Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales (IDEAM).

- Di Rienzo, J.A., Casanoves, F., Balzarini, M.G., Gonzalez, L., Tablada, M., Robledo, C.W. (2020) InfoStat. Insfostat. Córdoba, Ar.: Centro de Tranferencia InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina.

- Husson, F., Josse, J., Le, S., Maintainer, J.M. (2020) Package “FactoMineR”. Multivariate Exploratory Data Analysis and Data Mining.

- Kassambara, A., Mundt, F. (2020) Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. R Package Version 1.0.7. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=factoextra.

- Dray, S., Dufour, A.B. (2007) The ade4 Package: Implementing the Duality Diagram for Ecologists. Journal of Statistical Software, 22(4), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team (2024) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/.

- Posit Team (2024) RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Posit Software, PBC: Boston, MA, USA. https://posit.co/.

- Fernández de Andrade, L. (2014). Aplicación del índice de estabilidad estructural de Pieri (1995) a suelos montañosos de Venezuela. Terra, 30(48), 143–153.

- Lobo, D., Pulido, M. (2006) Métodos e índices para evaluar la estabilidad estructural de los suelos. Venesuelos, 14(1), 22–37.

- Kientz, D.G., Salazar, M.R., Pérez, E.M. (2000) Propiedades físicas y químicas de un suelo volcánico bajo bosque y cultivo en Veracruz, México. Foresta Veracruzana, 2(1), 31–34.

- Cruz, A.B., Barra, J.E., Castillo, R.F., Gutiérrez, C. (2004) La calidad del suelo y sus indicadores. Ecosistemas, 13(2).

- Yin, X., Zhao, L., Fang, Q., Ding, G. (2021) Differences in Soil Physicochemical Properties in Different-Aged Pinus massoniana Plantations in Southwest China. Forests 2021, 12(8), 987. [CrossRef]

- Volverás-Mambuscay, B., Merchancano-Rosero, J.D., Campo-Quesada, J.M., López-Rendón, J.F. (2020) Physical soil fertility in the sowing system in wachado on Nariño, Colombia. Agronomía Mesoamericana, 31(3), 743–760. [CrossRef]

- Arias, F., Alvarado, A., Mata, R., Serrano, E., Laguna, J. (2010) Relación entre la mineralogía de la fracción arcilla y la fertilidad en algunos suelos cultivados con banano en las llanuras aluviales del Caribe de Costa Rica. Agronomía Costarricense, 34, 223–236.

- Rica, C. (2009) Método gravimétrico para determinar in situ la humedad volumétrica del suelo. Agronomía Costarricense, 33(1), 121–124.

- Nissen, M.J., Quiroz, S.C., Seguel, S.O., MacDonald, H.R., Ellies, A. (2006) Flujo Hídrico no Saturado en Andisoles. Revista de La Ciencia Del Suelo y Nutrición Vegetal, 6(1), 9–19. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, E.M., Castillo, S.C., Zagal, V.E., Stolpe, L.N., Undurraga, D.P. (2007) Parámetros hidráulicos determinados en un Andisol bajo diferentes rotaciones culturales después de diez años. Revista de La Ciencia Del Suelo y Nutrición Vegetal, 7(2), 32–45. [CrossRef]

- Gallego, G.D., Marín-Toro, J.J., Alzate-Buitrago, A. (2023) Parent material effect’s and physical-mechanical properties on soil fertility. Universidad Libre Seccional Pereira.

- Nanzyo, M., Shoji, S., Dahlgren, R. (1993) Physical Characteristics of Volcanic Ash Soils. Developments in Soil Science, 21(C), 189–207. [CrossRef]

- Bockheim, J.G., Gennadiyev, A.N., Hartemink, A.E., Brevik, E.C. (2014) Soil-forming factors and Soil Taxonomy. Geoderma, 226–227(1), 231–237. [CrossRef]

- Soil Survey Staff (2010) Keys to Soil Taxonomy (11th ed.). USDA-NRCS.

- Shoji, S., Nanzyo, M., Dahlgren, R.A. (1993) Volcanic ash soils: genesis, properties and utilization. Volcanic Ash Soils: Genesis, Properties and Utilization. [CrossRef]

- Ayris, P.M., Delmelle, P. (2012) The immediate environmental effects of tephra emission. Bulletin of Volcanology, 74(9), 1905–1936.

- Dec, D., Dörner, J., Balocchi, O., López, I. (2012) Temporal dynamics of hydraulic and mechanical properties of an Andosol under grazing. Soil and Tillage Reseacrh, 125, 44–51. [CrossRef]

- Picón, K., Herrera, K., Avellán, D.R., Murcia, H., Botero-Gómez, L.A., Gómez-Arango, J. (2024) Radiocarbon dating, eruptive dynamics, and hazard implications of four Holocene Plinian-type eruptions recorded in Manizales city, Colombia. Natural Hazards, 120(6), 5561–5578.

- Medina-Castellanos, E.A., Sánchez-Espinosa, J.A., Cely-Reyes, G.E. (2017) Genesis and evolution of the Valle del Sibundoy soils. Ciencia y Agricultura, 14(1), 95–105. [CrossRef]

- Schott, J., Berner, R.A., Sjöberg, E.L. (1981) Mechanism of pyroxene and amphibole weathering I. Experimental studies of iron-free minerals. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 45(11), 2123–2135. [CrossRef]

- White, A.F. (2002) Determining mineral weathering rates based on solid and solute weathering gradients and velocities: application to biotite weathering in saprolites. Chemical Geology, 190(1–4), 69–89. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C., Brantley, S., Richter, D., Blum, A., Dixon, J., White, A.F. (2011) Strong climate and tectonic control on plagioclase weathering in granitic terrain. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 301(3–4), 521–530. [CrossRef]

- Bray, A.W., Oelkers, E.H., Bonneville, S., Wolff-Boenisch, D., Potts, N.J., Fones, G., Benning, L.G. (2015) The effect of pH, grain size, and organic ligands on biotite weathering rates. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 164, 127–145. [CrossRef]

- Brantley, S.L., Chen, Y. (1995) Chemical weathering rates of pyroxenes and amphiboles. Reviews in mineralogy, 31, 119–172. [CrossRef]

- Cronin, S.J., Hedley, M.J., Neall, V.E., Smith, R.G. (1998) Agronomic impact of tephra fallout from the 1995 and 1996 Ruapehu Volcano eruptions, New Zealand. Environmental Geology, 34(1), 21–30.

- Bockheim, J.G., Gennadiyev, A.N., Hammer, R.D., Tandarich, J.P. (2005) Historical development of key concepts in pedology. Geoderma, 124(1–2), 23–36. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, J., Nørremark, M., Bibby, B.M. (2007) Assessment of leaf cover and crop soil cover in weed harrowing research using digital images. Weed Research, 47(4), 299–310. [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, F., Dahlgren, R.A. (2002) Soil development in volcanic ash. Airies, 69, 1–13.

- Huggett, R.J. (1998) Soil chronosequences, soil development, and soil evolution: a critical review. Catena, 32(3–4), 155–172. [CrossRef]

- Wardle, D.A., Walker, L.R., Bardgett, R.D. (2004) Ecosystem properties and forest decline in contrasting long-term chronosequences. Science, 305(5683), 509–513.

- Walker, L.R., Wardle, D.A., Bardgett, R.D., Clarkson, B.D. (2010) The use of chronosequences in studies of ecological succession and soil development. Journal of Ecology, 98(4), 725–736. [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, M.B., Pérez, C., Núñez-Avila, M., Armesto, J.J. (2012) Desacoplamiento del desarrollo del suelo y la sucesión vegetal a lo largo de una cronosecuencia de 60 mil años en el volcán Llaima, Chile. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural, 85(3), 291–306. [CrossRef]

- Harden, J.W. (1982) A quantitative index of soil development from field descriptions: Examples from a chronosequence in central California. Geoderma, 28(1), 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Crews, T.E., Kitayama, K., Fownes, J.H., Riley, R.H., Herbert, D.A., Mueller-Dombois, D., Vitousek, P.M. (1995) Changes in Soil Phosphorus Fractions and Ecosystem Dynamics across a Long Chronosequence in Hawaii. Ecology, 76(5), 1407–1424. [CrossRef]

- Broquen, P., Candan, F., Falbo, G., Girardin, J.L., Pellegrini, V. (2005) Impact of Pinus ponderosa on acidification at forest-steppe transition soils, SW Neuquén, Argentina. Bosque (Valdivia), 26(3), 63–74. [CrossRef]

- Julca-Otiniano, A., Meneses-Florián, L., Blas-Sevillano, R., Bello-Amez, S. (2006) La materia orgánica, importancia y experiencia de su uso en la agricultura. Idesia (Arica), 24(1), 49–61. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Aparicio, J.C., Gutiérrez-Castorena, M., Cruz-Flores, G., Ortiz-Solorio, C.A. (2022) Reservas de carbono y micromorfología de la materia orgánica en suelos ribereños en tres ecosistemas de alta montaña: volcán Iztaccíhuatl. Madera y Bosques, 28(2). [CrossRef]

- Marín, S., Bertsch, F., Castro, L., Marín, S., Bertsch, F., Castro, L. (2017) Efecto del manejo orgánico y convencional sobre propiedades bioquímicas de un Andisol y el cultivo de papa en invernadero. Agronomía Costarricense, 41(2), 26–46. [CrossRef]

- Cortés, D., Pérez, J., Camacho-Tamayo, J.H. (2013) Relación espacial entre la conductividad eléctrica y algunas propiedades químicas del suelo. Actualidad y Divulgación UDCA, ISSN-e 0123-4226, ISSN 2619-2551, 16(2), 401–408.

- Gutiérrez, D.J.S., Cardoma, W.A., Monsalve, C.O. (2017) Potencial en el uso de las propiedades químicas como indicadores de calidad de suelo. Una revisión. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Hortícolas, 11(2), 450–458. [CrossRef]

- Nimmo, J.R. (2005) Porosity and pore-size distribution. Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment, 4, 295–303. [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, F., Regalado, C.M.. Basile, A., Buurman, P., Coppola, A. (2007) Physical properties in European volcanic soils: a synthesis and recent developments. Soils of Volcanic Regions in Europe, 515–537. [CrossRef]

- Dörner, J., Dec, D., Feest, E., Vásquez, N., Díaz, M. (2012) Dynamics of soil structure and pore functions of a volcanic ash soil under tillage. Soil and Tillage Research, 125, 52–60. [CrossRef]

- Furuhata, A., Hayashi, S. (1980) Relation between soil structure and soil pore composition: Case of volcanogenous soils in Tokachi district. Research Bulletin of the Hokkaido National Agricultural Experiment Station.

- Meza-Pérez, E., Geissert-Kientz, D. (2006) Estabilidad de estructura en Andisoles de uso forestal y cultivados. Terra Latinoamericana, 24(2), 163–170.

- Parfitt, R.L., Hemni, T. (1980) Structure of Some Allophanes from New Zealand. Clays and Clay Minerals 1980, 28(4), 285–294. [CrossRef]

- Hillel, D. (2003). Introduction to Environmental Soil Physics. Introduction to Environmental Soil Physics, 1–494. [CrossRef]

- Zagal, E., Rodríguez, N., Vidal, I., Flores, A.B. (2002) La fracción liviana de la materia orgánica de un suelo volcánico bajo distinto manejo agronómico como índice de cambios de la materia orgánica lábil. Agricultura Técnica, 62(2), 284–296. [CrossRef]

- Amézquita, E. (1999) Propiedades físicas de los suelos de los Llanos Orientales y sus requerimientos de labranza. Palmas, 20(1), 73–86.

- Malagón, D., Pulido, C., Llinas, R. (1991) Génesis y taxonomía de los Andisoles colombianos. Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi. Investigaciones, 3(1), 118.

- Christensen, B.T. (1996) Matching measurable soil organic matter fractions with conceptual pools in simulation models of carbon turnover: Revision of model structure. In Powlson D. S., P. Smith, and J. Smith (eds). Evaluation of soil organic matter models using long-term datasets. Springer, 38, 144–160.

- Graham, M.H., Haynes, R.J., Meyer, J.H. (2002) Soil organic matter content and quality: effects of fertilizer applications, burning and trash retention on a long-term sugarcane experiment in South Africa. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 34, 93–102. [CrossRef]

- Volverás-Mambuscay, B., Amézquita, E., Campo, J.M. (2016) Indicadores de calidad física del suelo de la zona cerealera andina del departamento de Nariño, Colombia. Corpoica Ciencia & Tecnología Agropecuaria, 17, 361–377. http://doi.org/10.21930/rcta.vol17_num3_art:513” Thank you for reaching out.

- Hofstede, R. (2001) El Impacto de las actividades humanas sobre el páramo. En: Mena, P., Medina, G., & Hofstede, R. Los páramos del Ecuador, particularidades, problemas y perspectivas. Abya-Yala, Proyecto Páramo, 311, 161–182.

- Hernández, F., Triana, F., Daza, M. (2009) Efecto de las actividades agropecuarias en la capacidad de infiltración de los suelos del páramo del Sumapaz. Ingeniería de los Recursos Naturales y del Ambiente, 8, 29–38.

- Clunes, J., Dörner, J., Pinochet, D. (2021) How does the functionality of the pore system affects inorganic nitrogen storage in volcanic ash soils? Soil and Tillage Research, 205, 104802. [CrossRef]

- Dörner, J., Dec, D., Peng, X., Horn, R. (2010) Effect of land use change on the dynamic behaviour of structural properties of an Andisol in southern Chile under saturated and unsaturated hydraulic conditions. Geoderma, 159(1–2), 189–197. [CrossRef]

- Reszkowska, A., Krümmelbein, J., Gan, L., Peth, S., Horn, R. (2011) Influence of grazing on soil water and gas fluxes of two Inner Mongolian steppe ecosystems. Soil and Tillage Research, 111, 180–189. [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, D., Hernández, O., Vélez, J.A. (2010) Efecto de la labranza sobre las propiedades físicas en un andisol del departamento de Nariño. Revista de Ciencias Agrícolas, 27(1), 40-48. ISSN-e 2256-2273.

| Physicochemical variables | Method of determination | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk density (ρa) | Cylinder of known volume | g.cm-3 |

| True density (ρr) | Pycnometer | g.cm-3 |

| Total porosity (Pr) | % | |

| Gravimetric humidity (GH) | 105 °C stove | % |

| Volumetric humidity (VH) | % | |

| Hydraulic conductivity (HC) | Constant head permeameter | cm/hour |

| Structural stability (SS) | dry sieving | DPM-mm |

| Microporosity (MiPr) | Calculation | % |

| Macroporosity (MaPr) | Calculation | % |

| Mesoporosity (MePr) | Calculation | % |

| Color in wet soil | Munsell Table | - |

| Texture | To the touch | - |

| pH | Active acidity/pH in soils GA-R-46, version 06, 2021-10-25. | Units ofpH |

| Electrical conductivity (EC) | NTC 5596:2008 Method B. | dS/m |

| Organic Carbon (C) | Determination of organic carbon in soil GA-R-119 version 4, 2021-10-25. | g/100g |

| Organic Matter (OM) | Calculation according to NTC 5403 Walkey & Black. | g/100g |

| Total nitrogen (TN) | Calculation | % |

| Disposable nitrogen (DN) | Calculation | % |

| Disposable phosphorus (P) | Available phosphorus in soils GA-R-48, 07, 2021-10-25 version. | mg/kg |

| Disposable sulfur (S) | Calcium monobasic phosphate | mg/kg |

| Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) | Calculation | cmol(+)/kg |

| Disposable boron (B) | Calcium monobasic phosphate | mg/kg |

| Acidity (Al+H; A) | KCl | cmol(+)/kg |

| Interchangeable aluminum (Al) | KCl | cmol(+)/kg |

| Disposable calcium (Ca) | Interchangeable bases on GA-R-50 version 9, 2021-10-25 floors. | cmol(+)/kg |

| Disposable magnesium (Mg) | Interchangeable bases on GA-R-50 version 9, 2021-10-25 floors. | cmol(+)/kg |

| Disposable potassium (K) | Interchangeable bases on GA-R -50 version 9, 2021-10-25 floors. | cmol(+)/kg |

| Disposable Olsen iron (Fe) | NTC 5526:2007 Method D. | mg/kg |

| Disposable Olsen copper (Cu) | NTC 5526:2007 Method D. | mg/kg |

| Disposable Olsen manganese (Mn) | NTC 5526:2007 Method D. | mg/kg |

| Disposable Olsen zinc (Zn) | NTC 5526:2007 Method D. | mg/kg |

| Ca-Mg ratio | Calculation | - |

| Mg-K ratio | Calculation | - |

| K-Mg ratio | Calculation | - |

| Ca-K ratio | Calculation | - |

| Ratio (Ca+Mg)/K | Calculation | - |

| Variable | L | S | Lx S |

|---|---|---|---|

| ρa | <0.0001*** | 0.5432ns | 0.0785* |

| ρr | 0.0001*** | 0.9360ns | 0.9954ns |

| Pr | 0.0002*** | 0.2720ns | 0.0425* |

| MiPr | 0.6703ns | 0.0484* | 0.0051* |

| MaPr | 0.6703ns | 0.0484* | 0.0051* |

| MePr | 0.6703ns | 0.0484* | 0.0051* |

| SS | 0.4251ns | 0.6782ns | 0.0080* |

| GH | <0.0001*** | 0.0287* | 0.0688* |

| VH | <0.0001*** | 0.1011ns | 0.1245ns |

| HC | 0.0679* | 0.4410ns | 0.2463ns |

| pH | <0.0001*** | 0.494ns | 0.6947ns |

| EC | 0.2214ns | 0.0059* | 0.2553ns |

| C | 0.0004*** | 0.1034ns | 0.9646ns |

| OM | 0.0004*** | 0.1034ns | 0.9786ns |

| TN | 0.0004*** | 01034ns | 0.9786ns |

| DN | 0.0004*** | 0.1034ns | 0.9786ns |

| P | 0.7391ns | <0.0001*** | 0.7999ns |

| S | 0.772ns | 0.5979ns | 0.9849ns |

| CEC | <0.0001*** | 0.41ns | 0.7612ns |

| B | 0.2461ns | 0.1797ns | 0.5336ns |

| A | 0.002*** | 0.4534ns | 0.9265ns |

| Al | 0.5034ns | 0.5034ns | 0.6616ns |

| Ca | <0.0001*** | 0.542ns | 0.677ns |

| Mg | 0.8157ns | 0.0251* | 0.158ns |

| K | 0.4507ns | 0.0186* | 0.9115ns |

| Fe | 0.0003*** | 0.0214* | 0.1051ns |

| Cu | 0.0008*** | 0.0003*** | 0.1241ns |

| Mn | 0.0011*** | 0.0479* | 0.1254ns |

| Zn | 0.4529ns | 0.0001*** | 0.8184ns |

| Ca-Mg | <0.0001*** | 0.8178ns | 0.4424ns |

| Mg-K | 0.3275ns | 0.0335* | 0.1079ns |

| K-Mg | 0.2686ns | 0.0004*** | 0.187ns |

| Ca-K | 0.3639ns | <0.0001*** | 0.5845ns |

| (Ca+Mg)/K | <0.0001*** | 0.3223ns | 0.5411ns |

| Variable | TGMVF | GSMVF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary forest | Pine crop | Pasture | Secondary forest | Paddock | Cutting pasture | Blackberry crop | |

| ρa | 0.79 ± 0.10 | 0.87 ± 0.09 | 0.89 ± 0.07 | 0.57 ± 0.07 | 0.38 ± 0.07 | 0.42 ± 0.12 | 0.60 ± 0.12 |

| ρr | 2.29 ± 0.16 | 2.37 ± 0.15 | 2.24 ± 0.12 | 1.87 ± 0.11 | 1.82 ± 0.11 | 1.93 ± 0.19 | 1.81 ± 0.19 |

| Pr | 65.47 ± 3.20 | 63.13 ± 2.92 | 60.67 ± 2.39 | 69.67 ± 3.02 | 78.67 ± 3.02 | 78.13 ± 5.45 | 66.20 ± 5.45 |

| MiPr | 17.94 ± 0.64 | 18.80 ± 0.59 | 19.93 ± 0.48 | 20.25 ± 0.58 b | 18.48 ± 0.58a | 18.10 ± 1.05a | 16.39 ± 1.05a |

| MaPr | 14.13 ± 1.28 | 12.39 ± 1.17 | 10.14 ± 7.03 | 9.50 ± 1.16 a | 13.04 ± 1.16b | 13.81 ± 2.09b | 17.21 ± 2.09b |

| MePr | 17.94 ± 0.64 | 18.80 ± 0.59 | 19.93 ± 0.48 | 20.25 ± 0.28b | 18.480 ± 0.58a | 18.10 ± 1.05a | 16.39 ± 1.05a |

| SS | 1.94 ± 0.69 | 1.47 ± 0.63 | 0.31 ± 0.51 | 0.66 ± 0.19 | 1.07 ± 0.19 | 0.45 ± 0.35 | 0.90 ± 0.35 |

| GH | 81.72 ± 21.63 | 89.20 ± 19.75 | 82.16 ± 16.12 | 185.84 ± 41.04a | 340.90 ± 41.04b | 233.50 ± 73.99a | 120.57 ± 73.99a |

| VH | 62.46 ± 7.03 | 70.07 ± 6.42 | 60.72 ± 5.24 | 81.06 ± 5.58 | 99.22 ± 5.58 | 94.54 ± 10.07 | 72.44 ± 10.07 |

| HC | 0.07 ± 0.12 | 0.22 ± 0.11 | 0.26 ± 0.09 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 0.37 ± 0.07 | 0.32 ± 0.13 | 0.12 ± 0.13 |

| pH | 7.24 ± 0.47 | 5.80 ± 0.43 | 6.88 ± 0.35 | 5.22 ± 0.19 | 5.08 ± 0.19 | 5.26 ± 0.33 | 5.17 ± 0.33 |

| EC | 0.72 ± 0.08b | 0.44 ± 0.07a | 0.65 ± 0.06b | 0.68 ± 0. 22a | 1.11 ± 0. 22a | 1.98 ± 0.99b | 0.76 ± 0. 39a |

| C | 4.04 ± 0.31 | 3.70 ± 0.29 | 4.34 ± 0.23 | 9.48 ± 1.46 | 9.64 ± 1.46 | 11.20 ± 2.63 | 7.30 ± 2.63 |

| OM | 6.97 ± 0.55 | 6.38 ± 0.50 | 7.41 ± 0.41 | 16.32 ± 2.51 | 16.63 ± 2.51 | 19.31 ± 4.53 | 12.31 ± 4.53 |

| TN | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.82 ± 0.13 | 0.83 ± 0.13 | 0.97 ± 0.23 | 0.62 ± 0.23 |

| DN | 7.0E-04±5.5E-05 | 6.4E-04 ± 5.0E-05 | 7.4E-04 ± 4.1E-05 | 1.6E-03 ± 2.5E-04 | 1.7E-03 ± 2.5E-04 | 1.9E-03 ± 4.5E-04 | 1.2E-03 ± 4.5E-04 |

| P | 10.67 ± 3.18 | 14.95 ± 2.90 | 16.17 ± 2.37 | 13.37 ± 4.09a | 16.70 ± 4.09a | 71.10 ± 7.38b | 24.92 ± 7. 38a |

| S | 13.34 ± 1.27 | 10.03 ± 1.16 | 12.97 ± 0.94 | 12.40 ± 3.56 | 11.90 ± 3.56 | 20.45 ± 6.42 | 10.75 ± 6.42 |

| CEC | 32.42 ± 7.92 | 10.26 ± 7.23 | 27.46 ± 5.91 | 8.97 ± 1. 58a | 6.43 ± 1. 58a | 18.19 ± 2. 86b | 4.94 ± 2. 86a |

| B | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 0.23 ± 0.07 | 0.25 ± 0.13 | 0.07 ± 0.13 |

| A | 0.00 ± 0.04 | 0.00 ± 0.04 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 2.25 ± 0.74 | 2.46 ± 0.74 | 2.42 ± 1.33 | 1.43 ± 1.33 |

| Al | 0.00 ± 0.03 | 0.00 ± 0.03 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 1.44 ± 0.58 | 1.99 ± 0.58 | 1.84 ± 1.05 | 1.05 ± 1.05 |

| Ca | 30.86 ± 7.88 | 8.96 ± 7.20 | 25.84 ± 5.88 | 4.41 ± 1. 41a | 2.64 ± 1. 41a | 13.68 ± 2.54b | 2.18 ± 2. 54a |

| Mg | 1.07 ± 0.17 | 1.00 ± 0.16 | 1.12 ± 0.13 | 1.44 ± 0.18b | 0.94 ± 0. 18a | 1.57 ± 0.32b | 0.43 ± 0. 32a |

| K | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 0.24 ± 0.06 | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 0.49 ± 0.07 | 0.42 ± 0.07 | 0.73 ± 0.13 | 0.33 ± 0.13 |

| Fe | 118.06 ± 36.69 | 186.21 ± 33.50 | 124.22 ± 27.35 | 248.33 ± 70. 67a | 490.54 ± 70.67b | 568.37 ± 127.41b | 220.93 ± 127.41a |

| Cu | 1.77 ± 0.37 | 2.14 ± 0.34 | 1.56 ± 0.28 | 2.53 ± 0. 43a | 3.74 ± 0. 43a | 5.89 ± 0.77b | 3.45 ± 0. 77a |

| Mn | 1.94 ± 0.54 | 3.39 ± 0.50 | 1.96 ± 0.41 | 26.69 ± 4.77 | 12.06 ± 4.77 | 9.93 ± 8.60 | 8.26 ± 8.60 |

| Zn | 3.78 ± 1.01 | 4.22 ± 0.92 | 4.88 ± 0.75 | 5.10 ± 1.24a | 5.61 ± 1.24a | 15.74 ± 2.24 b | 4.73 ± 2.24a |

| Ca-Mg | 29.07 ± 7.74 | 9.32 ± 7.06 | 23.71 ± 5.77 | 3.02 ± 0.60a | 3.23 ± 0.60a | 7.67 ± 1.09b | 5.25 ± 1.09a |

| Mg-K | 2.79 ± 0.70 | 4.24 ± 0.64 | 3.57 ± 0.52 | 3.26 ± 0.36 | 2.47 ± 0.36 | 2.35 ± 0.65 | 1.34 ± 0.65 |

| K-Mg | 0.41 ± 0.06 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.38 ± 0.06a | 0.48 ± 0.06a | 0.52 ± 0.10a | 0.81 ± 0.10b |

| Ca-K | 66.82 ± 21.27 | 41.63 ± 19.42 | 74.82 ± 15.86 | 10.91 ± 2.93 | 7.72 ± 2.93 | 21.62 ± 5.28 | 7.45 ± 5.28 |

| (Ca+Mg)/K | 69.61 ± 21.55 | 45.87 ± 19.67 | 78.39 ± 16.06 | 14.17 ± 3.19 | 10.19 ± 3.19 | 23.97 ± 5.76 | 8.79 ± 5.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).