1. Introduction

Numerous hydrocarbon deposits, gigantic in size, have been discovered in different years in the ring-type structure [

1,

2]. The origin of most of these structures is explained by a collision with a meteorite and the formation of an impact crater [

3,

4]. The origin and formation of ring-type structures still raise many questions. Reliable information about the structure of the Siljan crater and the composition of its rocks can help to find answers to these questions. Geophysical studies demonstrate the geological complexity of the Siljan Ring structure, particularly its structural and stratigraphic interrelations [

5,

6,

7].

This paper aims to present the results of a petrological study of basement rock samples selected from four exploratory boreholes drilled in the crater area. Information about the sedimentary cover structure in the western and eastern parts of the Siljan Ring, based on the investigation of two core sections (wells VM 1 and Solberg 1), is presented in [

8]. The results presented in [

6] were interpreted to support a suggestion regarding the differentiation of Ordovician–Silurian facies belts. It was proposed that the evolution of these facies reflects a transition from carbonate platform environments to continental conditions. The results of a detailed lithological study of 257 sedimentary rock samples selected from four exploratory wells (VM 1, VM 2, Solberga 1, and C-C-1) are presented in [

9]. The results of the structure description, texture, and mineralogy examination of the rocks in thin sections, revealed that the composition of sediments in the sedimentary cover surrounding the Siljan Ring structure varies across different areas, reflecting their facies and stratigraphic characteristics. Additionally, variations in the thickness of these sections and the succession sequences of rock units were identified. Such changes are likely attributed to tectonic disturbances of endogenous origin or impact sources. Research conducted on sedimentary and basement rock samples from the exploration C-C-1 well, as presented in [

10], offers valuable insights for reconstructing the geological setting in the southwestern region of the Siljan Ring. The findings indicate that the interface between the basement and the sedimentary cover is tectonic, rather than resulting from normal sedimentary processes.

This paper presents the findings of an extensive petrographic analysis of 468 basement rock samples collected from four exploratory wells: VM 1, VM 2, and Solberga-1. The study includes structure description, textural analysis, and mineralogical examination of the rocks in thin sections. As a result, comprehensive petrographic characteristics of the basement rocks from the examined intervals were obtained. These insights are significant for refining stratigraphic models, reconstructing tectonic settings, and forecasting potential oil and gas reservoirs.

4. Results

As a result of the studies outlined in this paper, detailed petrographic characteristics of the basement rocks from the drilled intervals have been compiled. Utilizing the obtained characteristics, relatively homogeneous petrographic units were identified, and columns illustrating the structure of each borehole’s sections were created. A total of 21 petrotypes were identified and characterized (

Table 1). This set of petrotypes encompasses rocks of varying genesis and compositions, including igneous rocks (acidic, intermediate, and basic), volcanogenic acidic rocks, as well as metamorphic rocks (both metavolcanic and metasedimentary).

In the borehole sections VM-1 and VM-2, volcanic rocks of predominantly acidic composition are predominant, interspersed with intrusions of basic rocks. The volcanic rocks exhibit a porphyritic texture and show significant signs of secondary transformations, including kaolinitization and the replacement of plagioclases with calcite and sericite. Additionally, there is the formation of chlorite, epidote, and sericite within the primary mass of the rock (

Figure 2). In the VM-1 borehole section, zones of intense rock fragmentation, known as cataclasis, are identified. As a result, a distinct petrotype has been classified as cataclasites derived from acidic volcanites. These rocks are characterized by a brecciated structure, cataclastic and, in certain areas, a mylonitic structure (

Figure 3). Fine fractures throughout the rocks are filled with a micro-fine-grained material that includes fragments of rock-forming mineral grains and newly formed microflakes of clay and microparticles of carbonate minerals.

Intrusions composed of olivine monzogabbro-norites are identified in the sections of both boreholes. These intrusions exhibit a poikilophitic structure (

Figure 4) and are characterized by a dominant presence of plagioclases, which make up to 50% of the composition, predominantly of basic and intermediate types such as labradorite and andesine. The next most significant components are pyroxenes, comprising up to 35% of the total, specifically augite and hypersthene. Olivine and K-feldspars are found in lesser amounts, contributing up to 15% and 10%, respectively. Among the secondary minerals, chlorite, epidote, and sericite are the most prevalent.

Intrusions of fine-grained dolerites (

Figure 5) are observed exclusively in the lower part of the borehole VM-2 section. These dolerites feature a massive, fluidal structure and exhibit a porphyritic texture, complemented by an intersertal fabric in the groundmass. The composition is primarily characterized by medium and basic plagioclases (up to 60%, specifically andesine-labradorite), along with smaller amounts of epidote and biotite. The rock predominantly comprises of plagioclase microlites and ore minerals, which are sometimes entirely replaced by leucoxene. Notable alterations include active sericitization of plagioclases, leucoxenization of ore minerals, and chloritization within the main mass.

The basement section of borehole C-C-1 is characterized by weakly metamorphosed volcanogenic-sedimentary rocks, interspersed with isolated intrusions of gabbro-dolerites. The metatuffs and vitroclastic metatuffs (

Figure 6) share a similar mineral composition, predominantly featuring quartz and plagioclase (albite). In lesser amounts, K-feldspars and muscovite are also present. Additionally, secondary minerals such as calcite and sericite are found within this section.

The primary differences among the rocks lie in their quartz and albite percentages, as well as in their textures. Metatuffs typically contain 40-50% quartz and 30-35% albite, with a microgranoblastic texture, occasionally showing vitroclastic characteristics. In contrast, vitroclastic metatuffs comprise 70-75% quartz and 15-20% albite, exhibiting a vitroclastic texture.

Metatuffaceous siltstones and metasandstones (

Figure 7) are distinguished solely by the texture of their relict detrital components, which are silty and psammitic, respectively. The detrital part is primarily composed of quartz (up to 85%), with K-feldspars reaching up to 5% and muscovite making up 1-2%.

The space between the relict detrital grains is occupied by a fine-grained aggregate of quartz, sericite, and feldspar, consisting of small isometric grains measuring between 0.001 and 0.01 mm. A sporadic distribution of secondary calcite is observed.

Notable differences in textural parameters are also present among the arkose metasandstones, metasilty sandstones, and metasiltstones (

Figure 8). The mineral composition of these rocks is largely consistent, comprising approximately 50-55% quartz, 25-30% plagioclase (including albite and oligoclase), up to 20% K-feldspars (such as orthoclase and microcline), and 7-10% muscovite. Additionally, secondary minerals present include calcite in siltstones and sandstones, dolomite, chlorite, and anhydrite.

Gabbro-dolerites comprise an interval with a thickness of 13.05 m, characterized by heterogeneity of the mineral composition. In the lower part of this interval, olivine is present in the rocks, in an amount of up to 7%. However, in the upper part, olivine is absent and micropegmatite intergrowths of quartz and feldspar are observed (

Figure 9). Overall, the mineral composition consists of: plagioclase (labradorite) – 55-60%, clinopyroxene – 10-15%, orthopyroxene – 5-10%, olivine – 5-7%, quartz – 2-3%, micropegmatite – 5-10%, biotite – 3-5%, along with isolated fragments of hornblende and volcanic glass. There is also a notable development of secondary minerals, including chlorite, sericite, and iron hydroxides.

The basement section of the Solberga-1 borehole is characterized by petrotypes of igneous plutonic rocks, including three varieties of granite, diorite, and monzonite. The granites are primarily differentiated by their еучегку, which includes porphyritic, coarse-grained, and fine-grained types (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). The mineral composition among the three subtypes is largely consistent, with plagioclases (andesine) comprising 25-40%, potassium feldspars (predominantly microcline with a microperthitic texture) making up 25-35%, quartz ranging from 15-30%, and biotite accounting for 15-20%. Notable variations can be observed in the coarse-grained two-mica granites, where muscovite may appear (up to 3%). In the porphyritic granites, there is an increase in the proportion of microcline with a microperthite texture (up to 65%), coinciding with a reduction in andesine content (down to 15%). Additionally, secondary mineral formation has been actively developed, including epidotization and sericitization of plagioclase, chloritization of biotite, kaolinitization of both plagioclase and K-feldspar, and leucoxenization of ore minerals.

Monzonites (

Figure 12) are distinguished by a high microcline content, which can reach up to 80%, along with notable variations in plagioclase content (andesine); in certain regions of the rock, it ranges from 5-10%, while in others, it increases to 35-45%. Additionally, secondary processes such as epidotization, chloritization, sericitization, and the formation of iron hydroxides are also present.

Diorites occur as thin layers (up to 4 cm) within granites and can be categorized into two types: those with a typomorphic composition (

Figure 13) and those with a higher quartz content. The predominant rock-forming minerals include medium-calcic plagioclases (andesine), which constitute 65-80%, and biotite, ranging from 20-35%.

5. Discussion

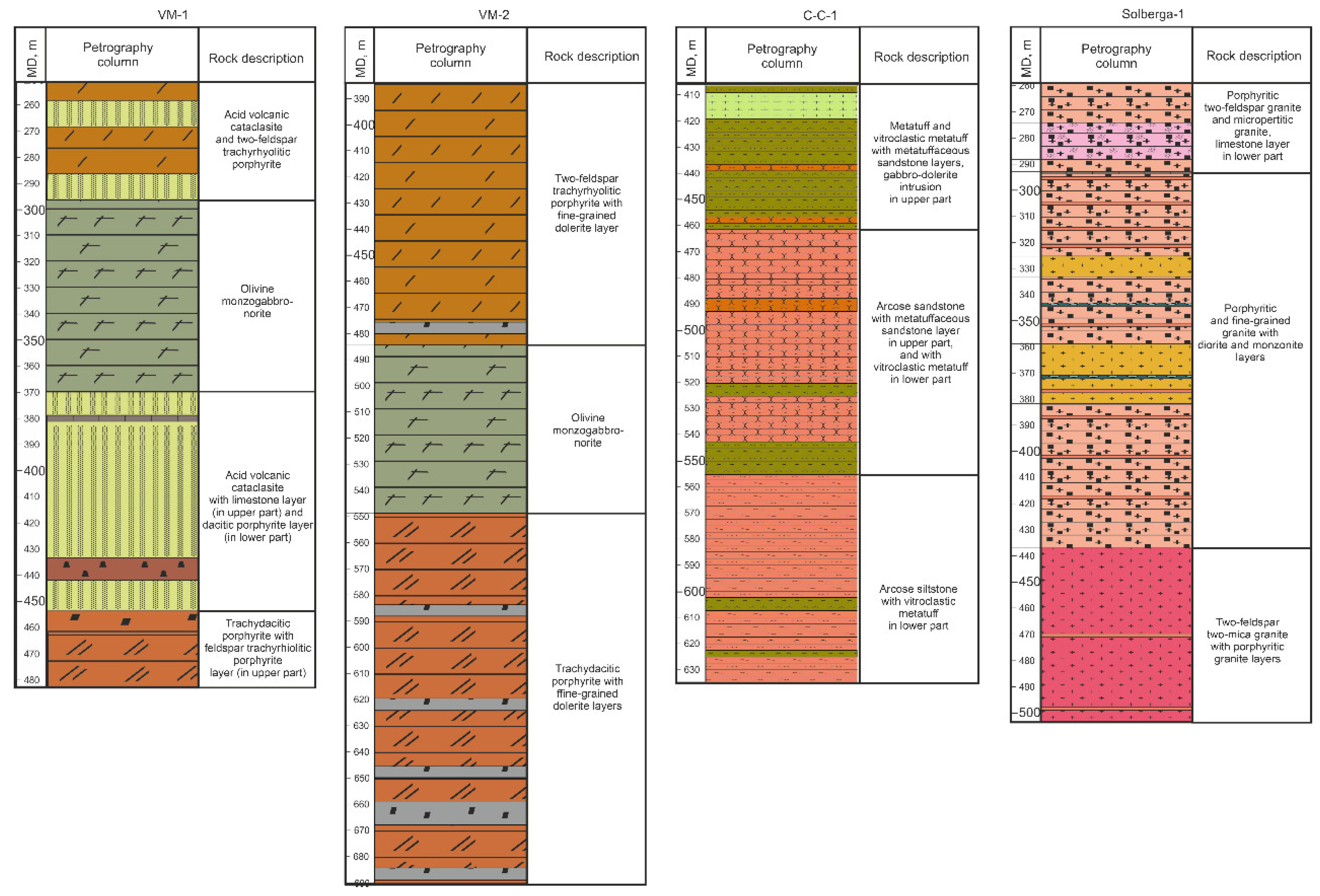

Basement sections in boreholes VM-2, VM-1, C-C-1, Solberga-1 are presented in

Figure 14.

The borehole sections VM-1 and VM-2 exhibit a similar arrangement of petrotypes and a comparable sequence of their variations throughout the sections. The predominant materials in these sections comprise volcanic rocks, specifically trachydacitic porphyrites in the lower part of the sections and trachyrhyolitic porphyrites in the upper part. These are separated by significant intrusions of olivine monzogabbro-norites, which can reach thicknesses of up to 74 meters.

However, within borehole VM-1, large packs of cataclasites, ranging from 10 to 52 meters in thickness, are prominent in both the lower and upper parts of the section. Additionally, a small layer of fine-grained limestone is identified in the lower part of borehole VM-1, likely representing an intrusion of tectonic origin. In contrast, the section from borehole VM-2 shows a more uniform composition regarding the identified porphyrite units, with the main variations in volcanic rock thickness introduced by interlayers of dolerite.

The nature of the changes in rock types suggests that the borehole section VM-1 is located within a fault zone, where active shear stresses have led to the cataclasis of porphyrites in the highly heterogeneous area surrounding the contact zone with the monzogabbro-norite intrusion.

In contrast, although borehole C-C-1 is situated nearby, its section exhibits a notable difference in the composition of its constituent units, with metamorphosed volcanic-sedimentary rocks prevailing. This indicates that the borehole may have penetrated a block of Proterozoic rocks that remained undisturbed by tectonic movements and experienced metamorphism during the orogenesis stage.

The Solberga-1 borehole section reveals granitoid rocks belonging to the post-orogenic development stage of the region, specifically from the Dala formation [

11,

12]. The granitic layers exhibit a heterogeneous character, characterized by the alternation of distinct types with varying structures and minor changes in the mineral composition, alongside the emergence of thin diorite interlayers. Notably, there are no significantly large zones of cataclasis or mylonitization, suggesting a relatively low intensity of tectonic shifts in this segment of the Siljan ring structure. However, in the upper part of the section, a thin limestone interlayer is present, indicating the existence of a fault zone and the impact of shear deformations in this particular area.

Figure 1.

Map scheme of the Siljan structure with the location of exploratory boreholes (modified from Ebbestad and Högström, 2007).

Figure 1.

Map scheme of the Siljan structure with the location of exploratory boreholes (modified from Ebbestad and Högström, 2007).

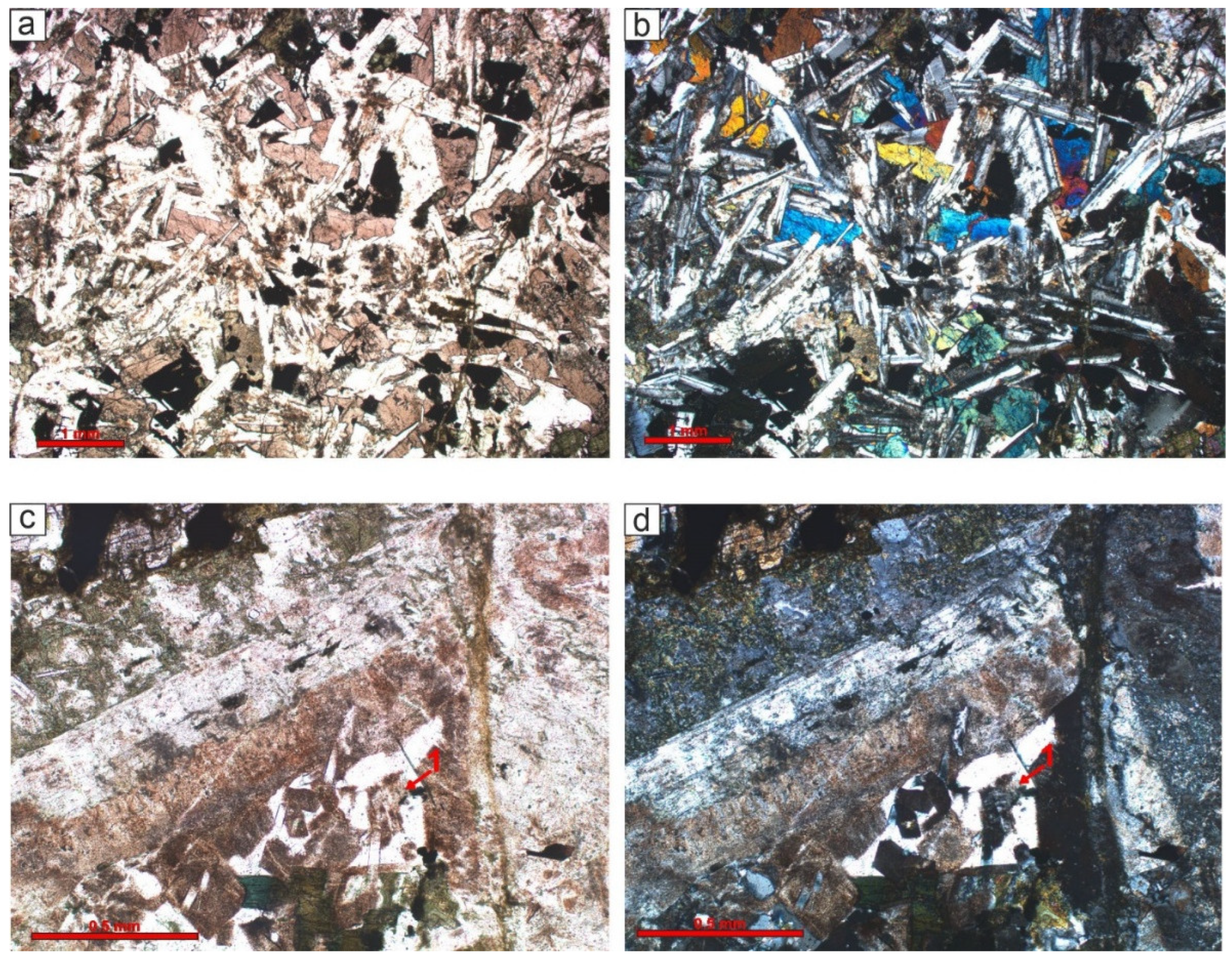

Figure 2.

Volcanogenic rocks of acid composition. Photos of rocks in thin sections: in plane-polarized light (left) and with crossed polars (right). a, b – two-feldspar trachyrhyolitic porphyryte (borehole VM-1, depth 280.71 m). Porphyritic-fluidal texture. Plagioclase grains replaced by kaolinite and calcite (1, 2). c, d – trachydacitic porphyryite (borehole VM-2, depth 618.90 m): 1 – chlorite inclusions; 2 – plagioclase grain replaced by sericite and calcite.

Figure 2.

Volcanogenic rocks of acid composition. Photos of rocks in thin sections: in plane-polarized light (left) and with crossed polars (right). a, b – two-feldspar trachyrhyolitic porphyryte (borehole VM-1, depth 280.71 m). Porphyritic-fluidal texture. Plagioclase grains replaced by kaolinite and calcite (1, 2). c, d – trachydacitic porphyryite (borehole VM-2, depth 618.90 m): 1 – chlorite inclusions; 2 – plagioclase grain replaced by sericite and calcite.

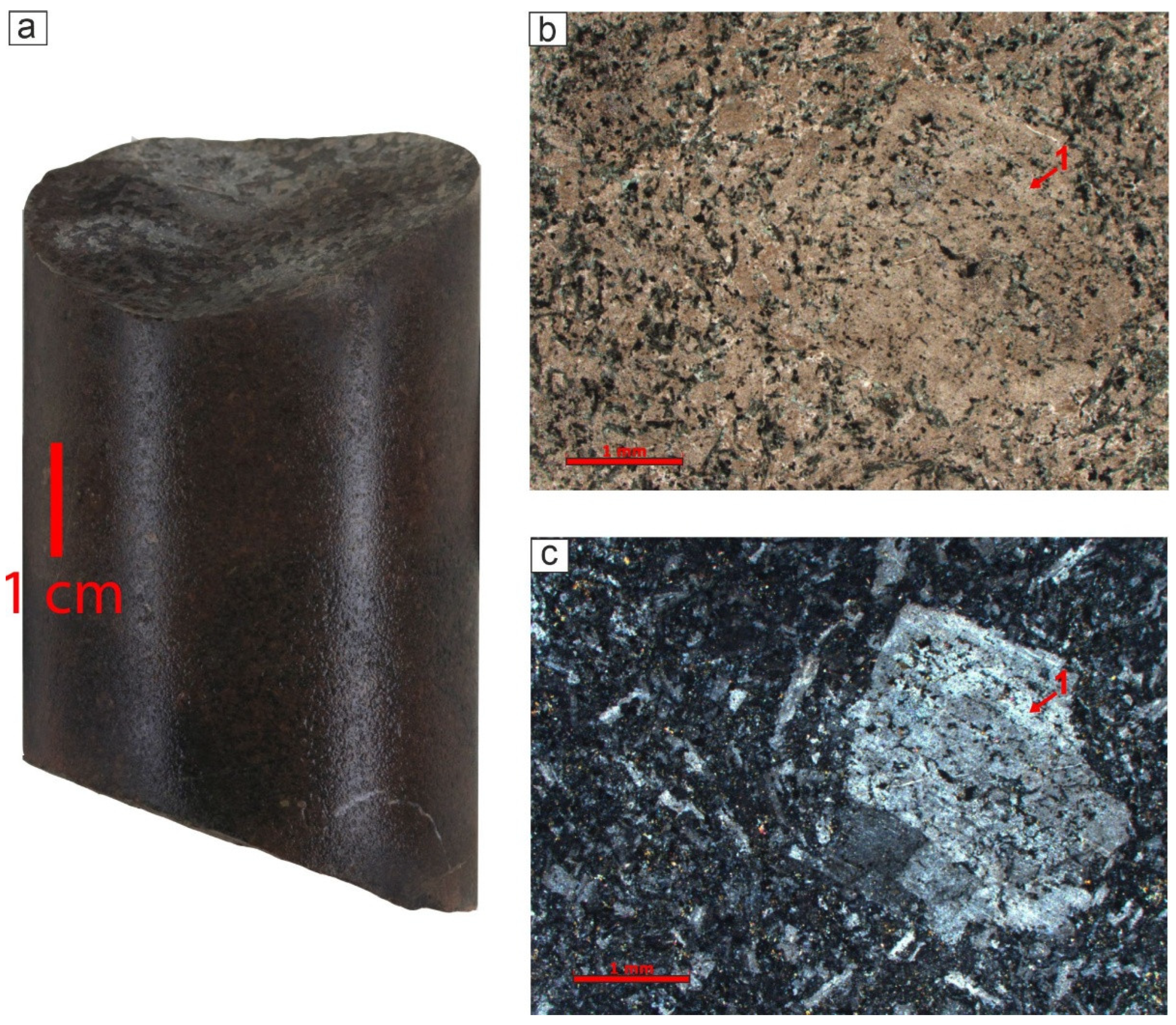

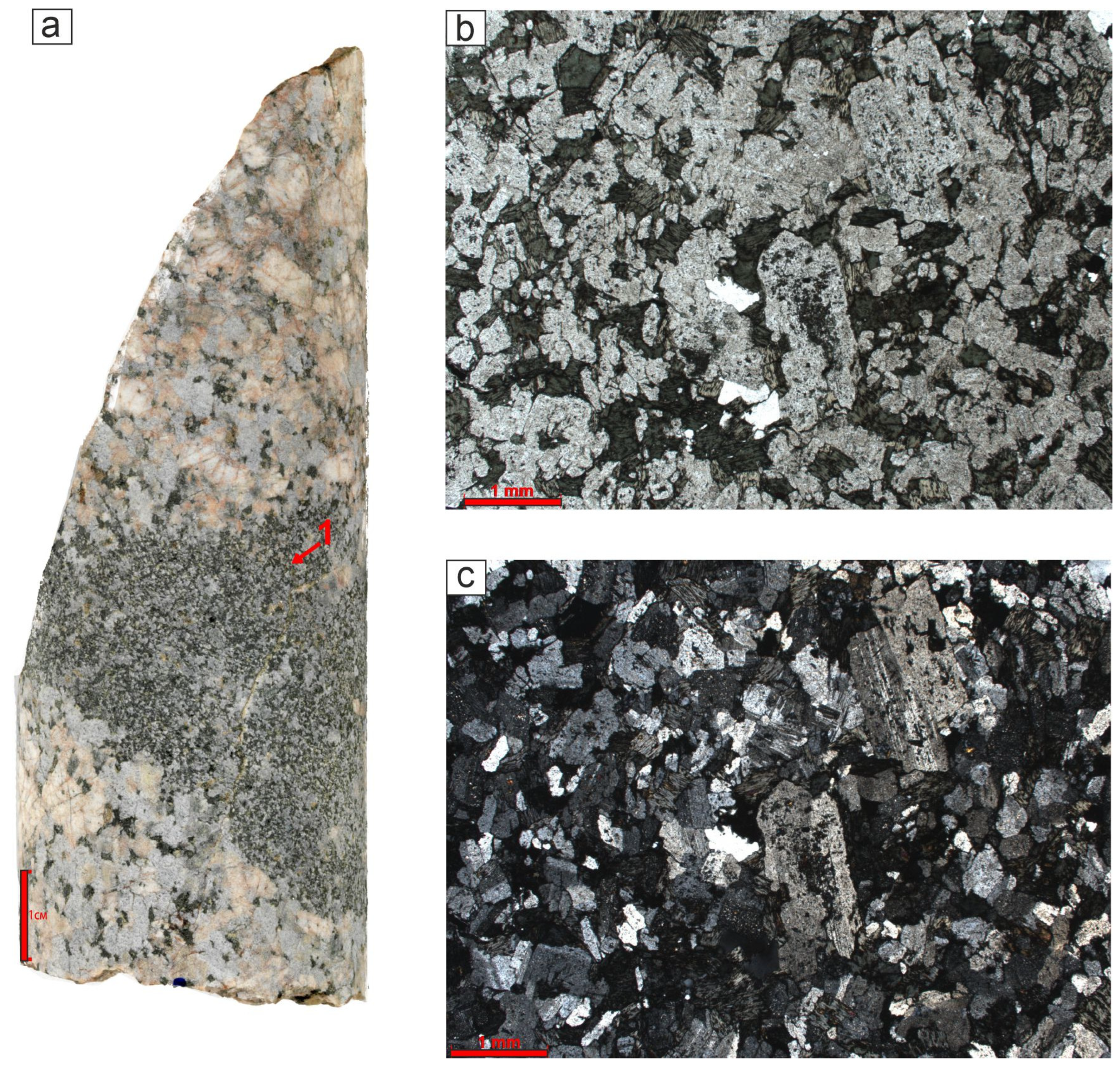

Figure 3.

Acid volcanic cataclasite (borehole VM-1, depth 400.48 m). Photo of sample (a) and rock in thin section: in plane-polarized light (b), with crossed polars (c). Fine-grained brecciated structure in the sample. Debris of acid volcanic rocks in mylonitic mass. 1, 2 – thin fractures filled with quartz.

Figure 3.

Acid volcanic cataclasite (borehole VM-1, depth 400.48 m). Photo of sample (a) and rock in thin section: in plane-polarized light (b), with crossed polars (c). Fine-grained brecciated structure in the sample. Debris of acid volcanic rocks in mylonitic mass. 1, 2 – thin fractures filled with quartz.

Figure 4.

Olivine monzogabbro-norite (borehole VM-1, depth 323.07 m). Photo of the rock in thin section: in plane-polarized light (a) and with crossed polars (b). Poikilophitic texture – poikilitic crystals of pyroxenes (1) among plagioclases. Olivine grain (2), epidote (3) in a fracture.

Figure 4.

Olivine monzogabbro-norite (borehole VM-1, depth 323.07 m). Photo of the rock in thin section: in plane-polarized light (a) and with crossed polars (b). Poikilophitic texture – poikilitic crystals of pyroxenes (1) among plagioclases. Olivine grain (2), epidote (3) in a fracture.

Figure 5.

Fine-grained dolerite (borehole VM-2, depth 587.77 m). Photo of sample (a) and rock in thin section: in plane-polarized light (b), with crossed polars (c). Massive structure in the sample. Porphyritic-resembling structure with intersertal texture of the groundmass. 1 – altered grain of plagioclase (sericitization, inclusions of ore minerals, epidote).

Figure 5.

Fine-grained dolerite (borehole VM-2, depth 587.77 m). Photo of sample (a) and rock in thin section: in plane-polarized light (b), with crossed polars (c). Massive structure in the sample. Porphyritic-resembling structure with intersertal texture of the groundmass. 1 – altered grain of plagioclase (sericitization, inclusions of ore minerals, epidote).

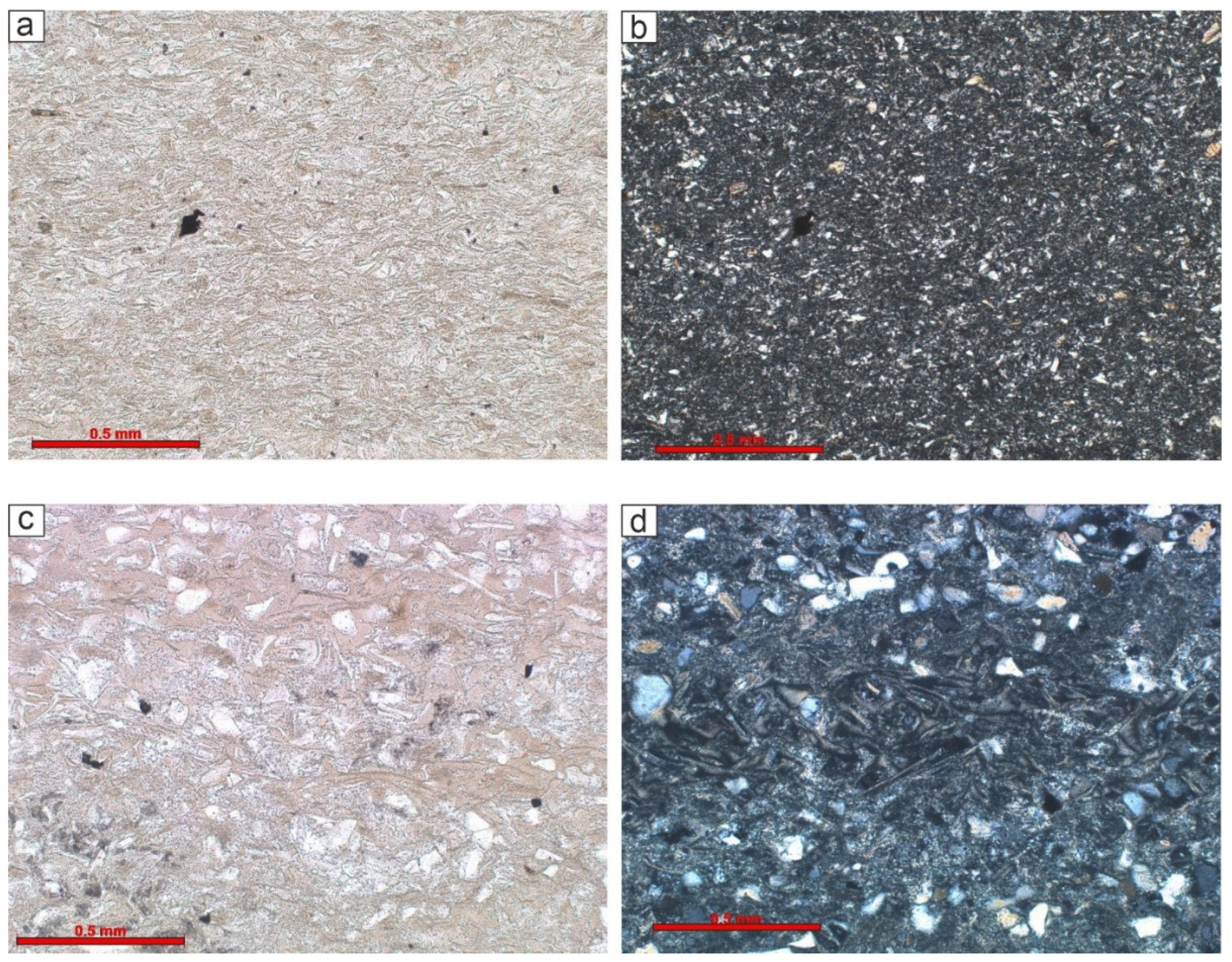

Figure 6.

Metatuff and vitroclastic metatuff (borehole C-C-1). Photos of rocks in thin sections: in plane-polarized light (left) and with crossed polars (right). a, b – microgranoblastic texture, partially – vitroclastic (depth 553.48 m). c, d – quartz grains in vitroclastic mass (depth 544.47 m).

Figure 6.

Metatuff and vitroclastic metatuff (borehole C-C-1). Photos of rocks in thin sections: in plane-polarized light (left) and with crossed polars (right). a, b – microgranoblastic texture, partially – vitroclastic (depth 553.48 m). c, d – quartz grains in vitroclastic mass (depth 544.47 m).

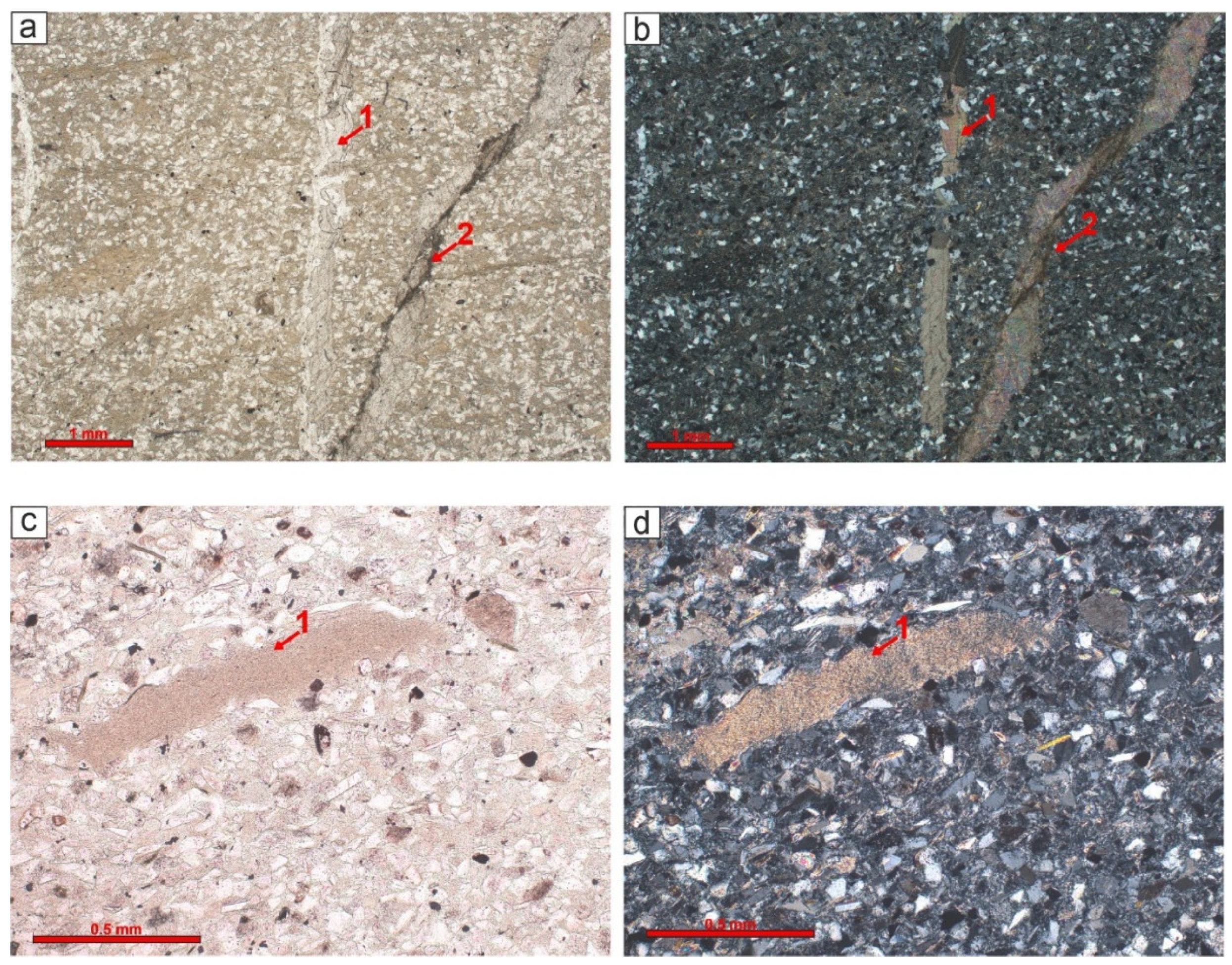

Figure 7.

Metatuffaceous sandstone and metatuffaceous siltstone (borehole C-C-1). Photos of rocks in thin sections: in plane-polarized light (left) and with crossed polars (right). a, b – cracks with calcite (1) and clayey (2) filling in metatuffaceous sandstone (depth 456.70 m). c, d – sericitized fragment of volcanic glass in metatuffaceous siltstone (depth 615.12 m).

Figure 7.

Metatuffaceous sandstone and metatuffaceous siltstone (borehole C-C-1). Photos of rocks in thin sections: in plane-polarized light (left) and with crossed polars (right). a, b – cracks with calcite (1) and clayey (2) filling in metatuffaceous sandstone (depth 456.70 m). c, d – sericitized fragment of volcanic glass in metatuffaceous siltstone (depth 615.12 m).

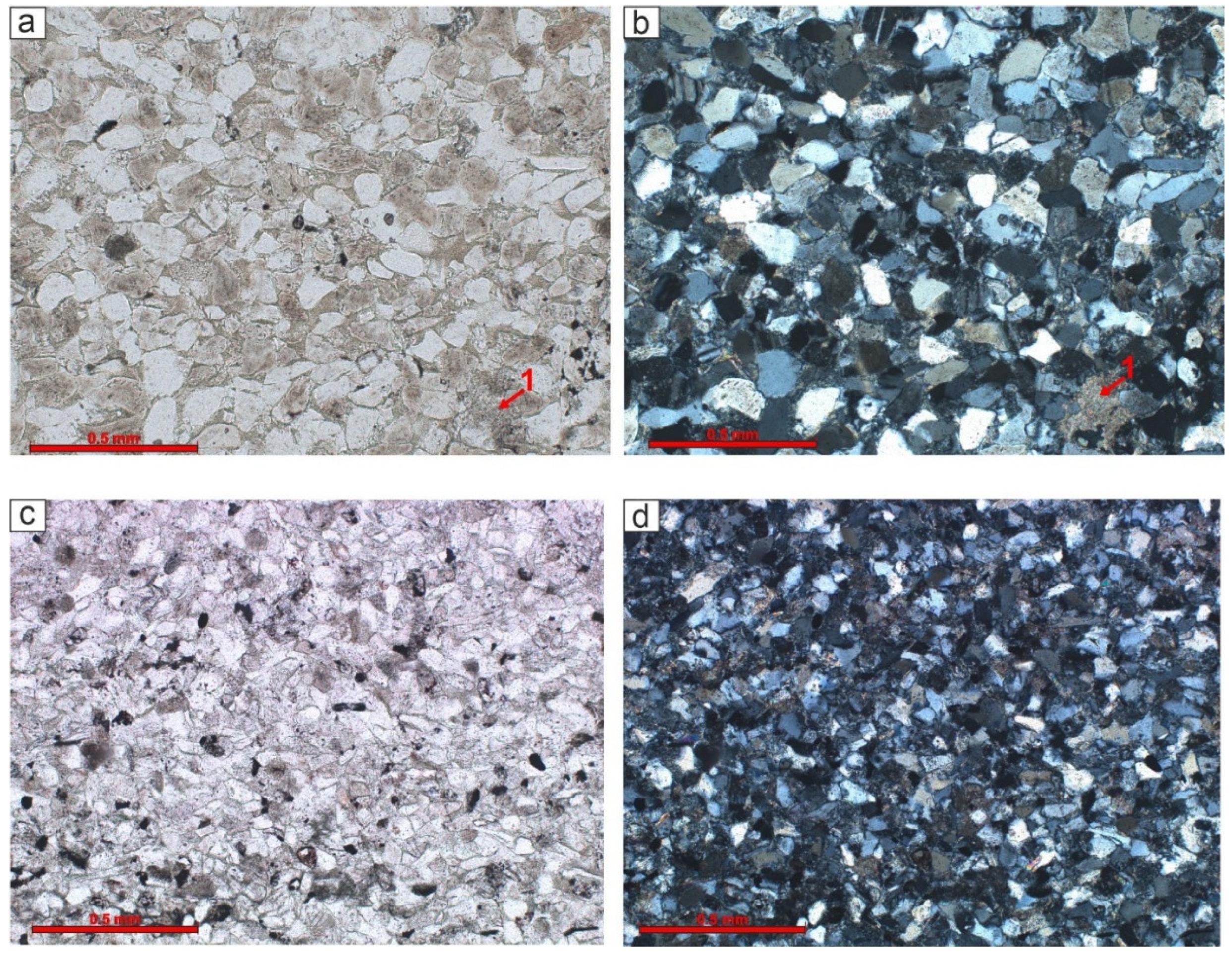

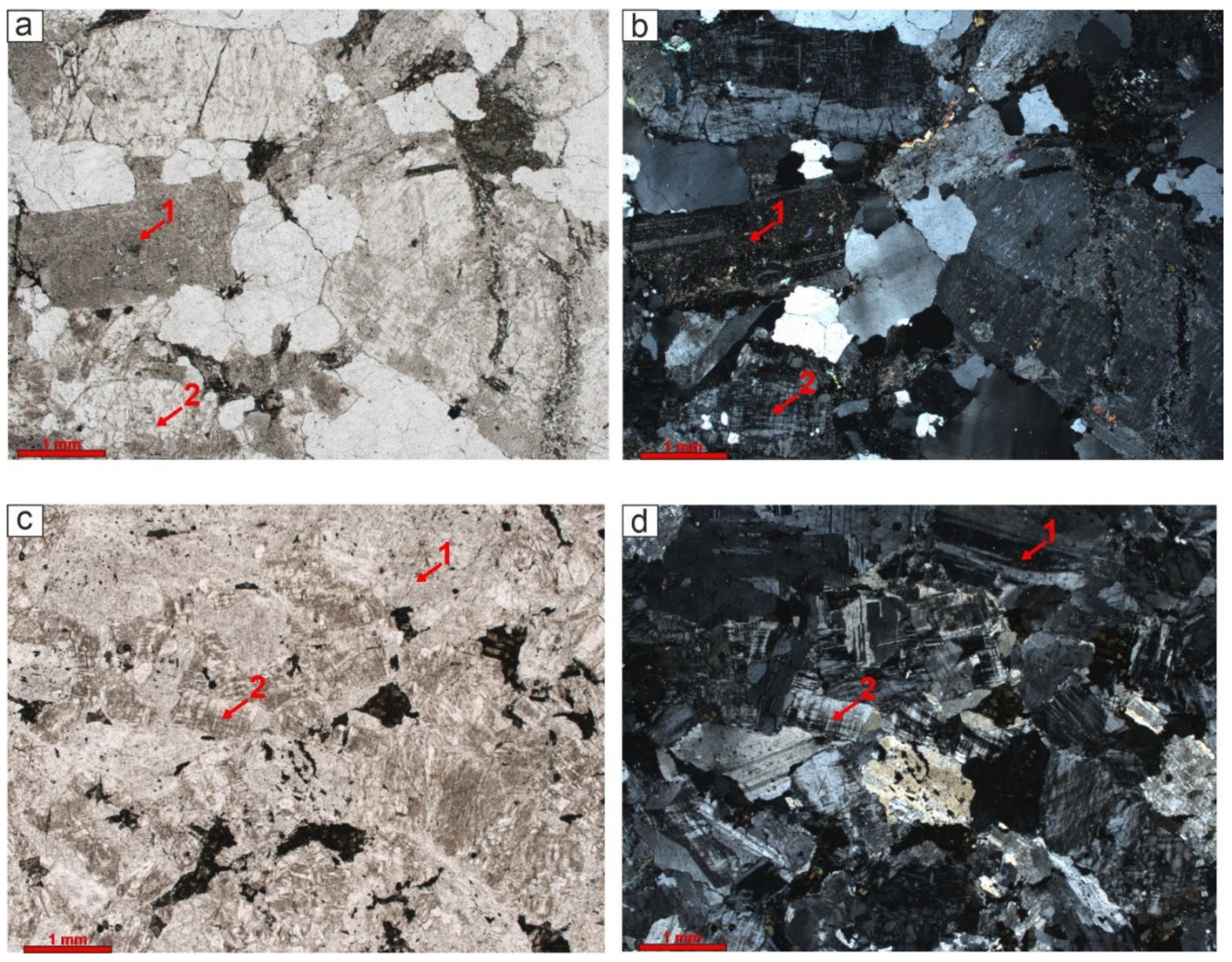

Figure 8.

Metasandstone and metasiltstone (borehole C-C-1). Photos of rocks in thin sections: in plane-polarized light (left) and with crossed polars (right). a, b – relict psammitic texture of metasandstone; 1 – accumulations of secondary calcite (depth 469.82 m). c, d – relict silt-psammitic texture in metasiltstone (depth 560.55 m).

Figure 8.

Metasandstone and metasiltstone (borehole C-C-1). Photos of rocks in thin sections: in plane-polarized light (left) and with crossed polars (right). a, b – relict psammitic texture of metasandstone; 1 – accumulations of secondary calcite (depth 469.82 m). c, d – relict silt-psammitic texture in metasiltstone (depth 560.55 m).

Figure 9.

Gabbro-dolerites (borehole C-C-1). Photos of rocks in thin sections: in plane-polarized light (left) and with crossed polars (right). a, b – poikilophitic texture with micropegmatite zones (depth 418.35 m). c, d – parts of micropegmatitic texture – 1 (depth 412.21 m).

Figure 9.

Gabbro-dolerites (borehole C-C-1). Photos of rocks in thin sections: in plane-polarized light (left) and with crossed polars (right). a, b – poikilophitic texture with micropegmatite zones (depth 418.35 m). c, d – parts of micropegmatitic texture – 1 (depth 412.21 m).

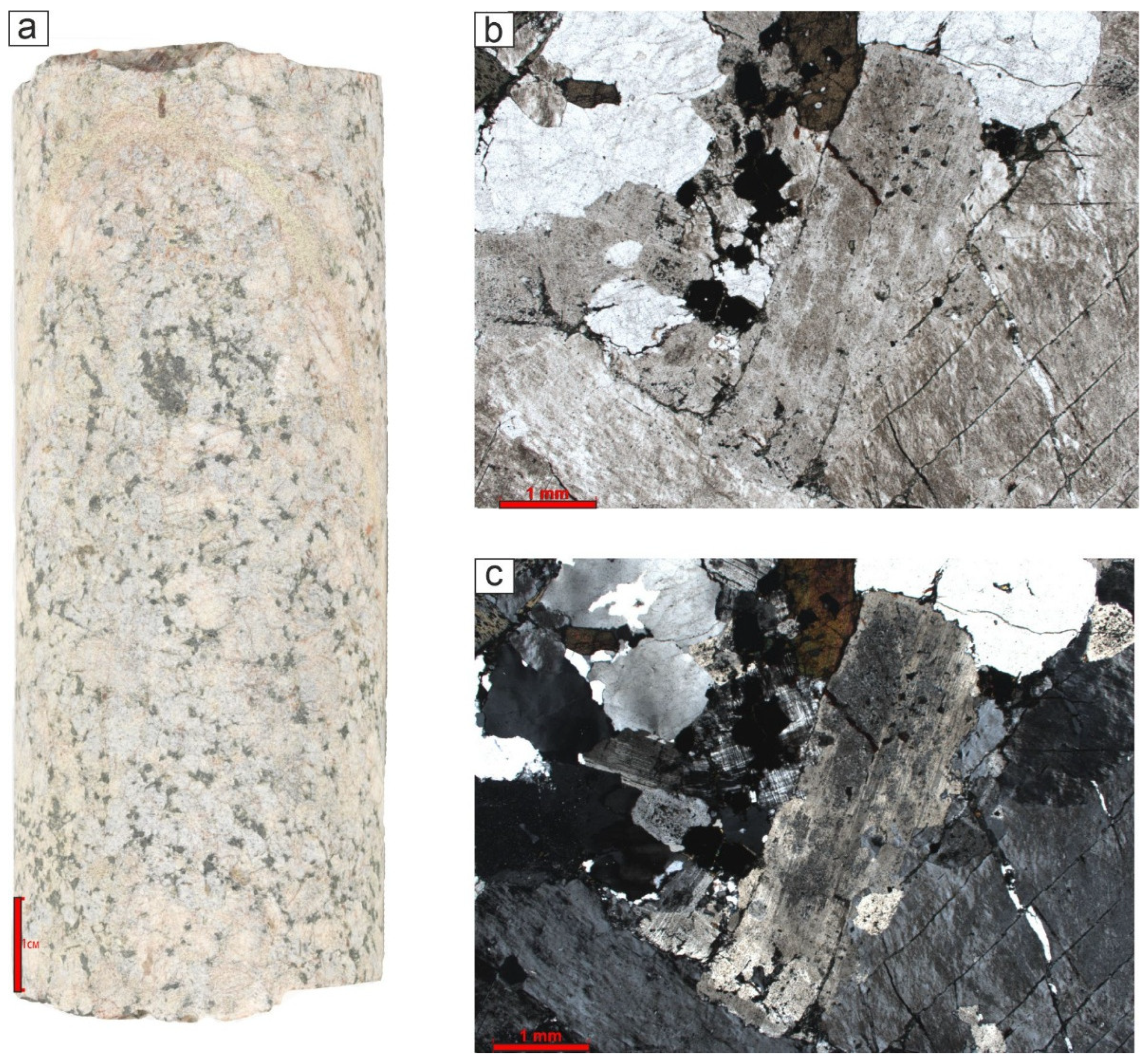

Figure 10.

Two-feldspar granites (Solberga-1 borehole). Photos of rocks in thin sections: in plane-polarized light (left) and with crossed polars (right). a, b – coarse-grained texture (depth 368.8 m). c, d – fine-grained texture (depth 467.2 m). Kaolinitization and sericitization of plagioclase (1) and K-feldspar (2).

Figure 10.

Two-feldspar granites (Solberga-1 borehole). Photos of rocks in thin sections: in plane-polarized light (left) and with crossed polars (right). a, b – coarse-grained texture (depth 368.8 m). c, d – fine-grained texture (depth 467.2 m). Kaolinitization and sericitization of plagioclase (1) and K-feldspar (2).

Figure 11.

Two-feldspar granite with porphyritic structure (Solberga-1 borehole, depth 422.35 m). Photo of sample (a) and rock in thin section: in plane-polarized light (b), with crossed polars (c). Porphyritic structure in the sample. Porphyritic texture: large hypidiomorphic crystals of K-feldspar.

Figure 11.

Two-feldspar granite with porphyritic structure (Solberga-1 borehole, depth 422.35 m). Photo of sample (a) and rock in thin section: in plane-polarized light (b), with crossed polars (c). Porphyritic structure in the sample. Porphyritic texture: large hypidiomorphic crystals of K-feldspar.

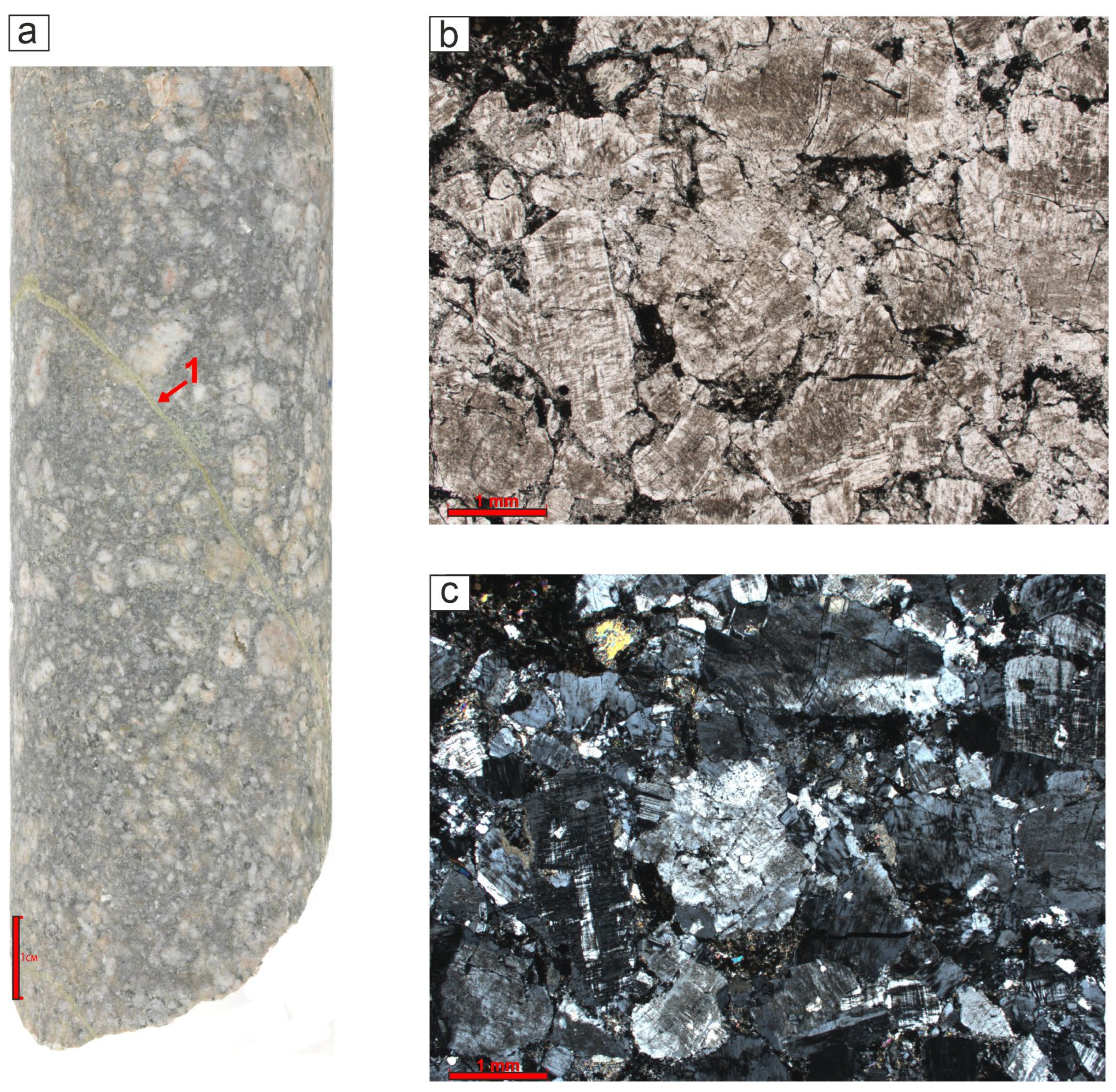

Figure 12.

Monzonite (Solberga-1 borehole, depth 371.45 m). Photo of sample (a) and rock in thin section: in plane-polarized light (b), with crossed polars (c). Mineralized crack in monzonite with porphyritic structure (1). Hypidiomorphic crystals of K-feldspar.

Figure 12.

Monzonite (Solberga-1 borehole, depth 371.45 m). Photo of sample (a) and rock in thin section: in plane-polarized light (b), with crossed polars (c). Mineralized crack in monzonite with porphyritic structure (1). Hypidiomorphic crystals of K-feldspar.

Figure 13.

Diorite interlayer (1) in porphyritic granite (Solberga-1 borehole, depth 386.82 m). Photo of sample (a) and rock in thin section: in plane-polarized light (b), with crossed polars (c). Predominance of plagioclases and chloritized biotite in the crystalline mass of diorite.

Figure 13.

Diorite interlayer (1) in porphyritic granite (Solberga-1 borehole, depth 386.82 m). Photo of sample (a) and rock in thin section: in plane-polarized light (b), with crossed polars (c). Predominance of plagioclases and chloritized biotite in the crystalline mass of diorite.

Figure 14.

Basement sections in boreholes VM-2, VM-1, C-C-1, Solberga-1.

Figure 14.

Basement sections in boreholes VM-2, VM-1, C-C-1, Solberga-1.

Table 1.

Types of rocks in the sections of the studied boreholes.

Table 1.

Types of rocks in the sections of the studied boreholes.

| Well Number |

VM-1 |

VM-2 |

С-С-1 |

Solberga 1 |

| Sample depth, m |

250.90–482.90 |

382.30–690.50 |

406.15–634.90 |

258.80–503.20 |

| Quantity of m/samples |

232.00

159 |

308.20

71 |

228.75

44 |

244.40

194 |

| Petrotypes |

| Two-feldspar trachyrhyolitic porphyrite |

● |

● |

|

|

| Dacitic porphyrite |

● |

|

|

|

| Plagioclase trachyrhyolitic porphyrite |

● |

|

|

|

| Trachydacitic porphyrite |

● |

● |

|

|

| Acid volcanic cataclasite |

● |

|

|

|

| Olivine monzogabbro-norite |

● |

● |

|

|

| Fine-grained dolerite |

|

● |

|

|

| Gabbro-dolerite |

|

|

● |

|

| Metatuff (albite-quartz schist) |

|

|

● |

|

| Vitroclastic metatuff (sericite quartzite schist) |

|

|

● |

|

| Metatuffaceous siltstones (albite-quartz schist) |

|

|

● |

|

| Metatuffaceous sandstones (sericite-quartz schist) |

|

|

● |

|

| Arkose metasandstones (albite-quartz schist) |

|

|

● |

|

| Arkose metasiltstones (sericite-albite-quartz schist) |

|

|

● |

|

| Arkose metasiltstones (albite-quartz schist) |

|

|

● |

|

| Two-feldspar two-mica granite |

|

|

|

● |

| Porphyritic two-feldspar granite |

|

|

|

● |

| Fine-grained two-feldspar granite |

|

|

|

● |

| Monzonite |

|

|

|

● |

| Quartz diorite |

|

|

|

● |

| Diorite |

|

|

|

● |