1. Introduction

Mental health disorders represent one of the most significant health challenges facing children and adolescents globally. Despite substantial investments by governments and healthcare systems over the past two decades, the prevalence of mental health conditions among young people has remained stubbornly unchanged [

1]. This fact is particularly concerning given that approximately 50% of all mental health disorders have their onset before the age of 14 years [

2]. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated this situation, introducing new stressors and barriers to care while simultaneously accelerating digital transformations in healthcare delivery [

3,

4].

Traditional models of pediatric mental healthcare continue to face persistent challenges. Long waiting lists, high costs, geographical limitations, stigma, and shortages of specialized providers create substantial barriers to accessing timely and appropriate care [

5]. These systemic issues are further complicated by difficulties in early identification of mental health concerns in children and adolescents, as well as the tendency for pediatric mental health services to mirror adult-oriented approaches that not adequately address the unique developmental needs of younger populations [

6,

7].

Against this backdrop, artificial intelligence (AI) conversational agents—such as large language models (LLMs) exemplified by ChatGPT, Claude, and similar technologies—have emerged as potential supplementary tools in the mental health landscape [

8,

9]. These AI systems can engage in text-based dialogues that simulate human conversation, providing a novel medium through which children and adolescents might express emotions, receive information, and potentially experience therapeutic interactions [

10]. The 24/7 availability, lack of judgment, and low access threshold of these tools address several traditional barriers to care, suggesting potential utility as adjunctive approaches within comprehensive mental health frameworks [

11].

However, the application of conversational AI in pediatric mental health contexts remains in its infancy, with limited empirical investigation specifically addressing efficacy, safety, and implementation considerations for children and adolescents [

12,

13]. While preliminary research with adult populations has indicated promising results for certain applications—such as cognitive behavioral therapy support, mood monitoring, and psychoeducation [

14]—the translation of these findings to pediatric populations requires careful consideration of developmental, ethical, and safety factors [

15].

This review aims to critically examine the current evidence base regarding conversational AI applications in pediatric mental health, synthesizing findings across disciplines including psychology, psychiatry, computer science, and ethics. We evaluate the potential therapeutic mechanisms through which these tools might function, identify promising applications within pediatric mental health contexts, and discuss critical considerations for safe and effective implementation. By mapping the current state of knowledge and identifying key research gaps, this review seeks to establish a foundation for future empirical work while providing preliminary guidance for clinicians, developers, and policymakers interested in the responsible integration of AI conversational agents into pediatric mental health services [

16].

2. Scoping Review Methodology

This review followed the methodological framework for scoping reviews outlined by Arksey and O'Malley [

17] and further refined by Levac et al. [

18], with reporting guided by the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [

19]. The scoping review approach was selected due to the emerging nature of conversational AI applications in pediatric mental health and the need to map the breadth of existing literature across multiple disciplines.

2.1. Research Questions

This scoping review aimed to address the following questions:

What types of conversational AI applications have been developed or proposed for supporting pediatric mental health?

What is the current evidence regarding the effectiveness, acceptability, and safety of these applications?

What unique considerations apply to the use of conversational AI with children and adolescents compared to adults?

What ethical, technical, and implementation challenges have been identified?

What gaps exist in the current research landscape?

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

We conducted searches across multiple electronic databases to capture literature from diverse disciplines including medicine, psychology, computer science, and digital health. Databases included PubMed/MEDLINE, PsycINFO, ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, and Scopus. The search was supplemented by examining reference lists of included articles and relevant review papers.

The search strategy combined terms related to three key concepts: (1) conversational AI technologies (e.g., "chatbot," "conversational agent," "large language model"), (2) mental health (e.g., "mental health," "psychological support," "therapy"), and (3) pediatric populations (e.g., "child," "adolescent," "youth"). The search was limited to English-language publications from January 2010 to February 2025. Given the rapid evolution of large language models, we also included relevant preprints from arXiv and other repositories to capture emerging research.

2.3. Study Selection

Articles were eligible for inclusion if they discussed conversational AI applications in mental health contexts, had relevance to pediatric populations (either directly studying children/adolescents or with clear pediatric implications), and included original research, theoretical frameworks, ethical analyses, or significant commentary on implementation. We included a broad range of publication types, including empirical studies, technical descriptions, ethical analyses, theoretical papers, and relevant case studies. This inclusive approach is characteristic of scoping reviews and appropriate for mapping an emerging field where evidence come in diverse forms. Initial screening of titles and abstracts was conducted by two independent reviewers, with full-text review of potentially relevant articles.

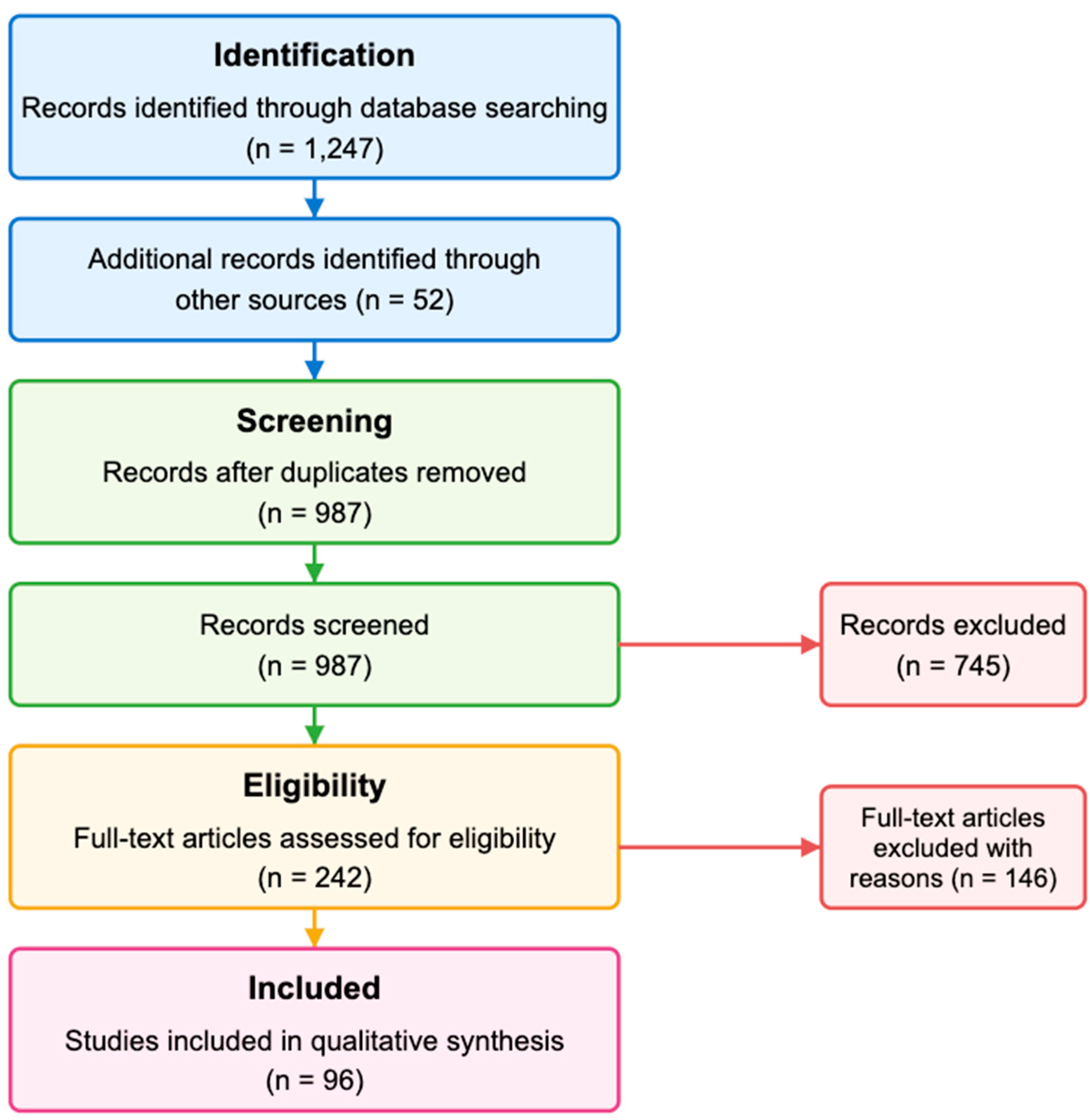

Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA flow diagram of our literature search and study selection process, showing the identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion of studies.

2.4. Data Synthesis

We employed a narrative synthesis approach with thematic analysis to organize findings into meaningful categories. The analysis focused on mapping the current landscape rather than evaluating effectiveness or quality. We identified patterns across studies while highlighting conceptual boundaries, contradictions in the literature, and areas of emerging consensus. Special attention was given to identifying research gaps and future directions.

The synthesis was structured thematically around key aspects of conversational AI in pediatric mental health, including technological approaches, therapeutic applications, developmental considerations, implementation contexts, and ethical frameworks. This organization allows for a comprehensive overview of the field accessible to interdisciplinary audiences.

In keeping with scoping review methodology, we presented the findings as a narrative overview supplemented by tables and figures that visually map the literature landscape. This approach provides both a comprehensive picture of current knowledge and clear identification of areas requiring further research [

20].

3. Current Landscape of Pediatric Mental Health Challenges

Mental health disorders represent a significant and growing public health concern for children and adolescents worldwide. Current epidemiological data indicate that approximately 13-20% of children under 18 years of age experience a diagnosable mental health condition in any given year [

21]. More concerning is evidence suggesting that the prevalence of certain conditions, particularly anxiety, depression, and behavioral disorders, has been steadily increasing over the past decade [

22]. This trend has been further accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which introduced unprecedented stressors including social isolation, academic disruptions, family economic hardships, and grief experiences [

23].

The burden of pediatric mental health conditions is distributed unevenly across populations, with significant disparities observed across socioeconomic, racial, and geographic lines [

24]. Children from lower-income families, racial and ethnic minorities, and those living in rural or underserved communities face disproportionate challenges in both the prevalence of mental health conditions and access to appropriate care [

25]. These disparities reflect broader social determinants of health that influence both the development of mental health conditions and the barriers to receiving timely intervention [

26]. Despite clear evidence demonstrating the benefits of early intervention, substantial gaps persist between the need for mental health services and their availability and accessibility for children and adolescents [

27].

3.1. Challenges of Current Mental Health Delivery

Current systems of care struggle with multiple interconnected challenges that limit their effectiveness.

3.1.1. Workforce Shortages

The global shortage of child psychiatrists, psychologists, and specialized mental health professionals creates a fundamental capacity limitation [

28]. In many regions, the ratio of child mental health specialists to the pediatric population falls dramatically below recommended levels, creating bottlenecks in service delivery and extending wait times for initial assessments and ongoing treatment [

29].

3.1.2. Access Barriers

Even when services exist, multiple barriers impede access, including geographical limitations, transportation challenges, scheduling constraints, high costs, and insurance coverage limitations [

30]. For many families, particularly those in rural or underserved areas, the nearest appropriate provider be hours away, making regular attendance at appointments impractical or impossible [

31].

3.1.3. Fragmented Systems

Pediatric mental healthcare often spans multiple systems including healthcare, education, juvenile justice, and social services. Poor coordination between these systems creates fragmented care pathways, administrative burdens for families, and opportunities for vulnerable children to "fall through the cracks" [

32].

3.1.4. Detection and Referral Challenges

Many mental health conditions in children present initially as somatic complaints, behavioral problems, or academic difficulties and not be readily recognized as mental health concerns by parents, teachers, or primary care providers [

33]. These challenges contribute to delays in identification and appropriate referral, particularly in contexts where mental health literacy remains limited [

34].

3.1.5. Stigma and Help-Seeking Barriers

Despite some progress, mental health conditions continue to carry significant stigma that can discourage help-seeking behaviors among young people and their families [

35]. Adolescents, in particular, often express concerns about confidentiality, judgment from peers, and reluctance to engage with traditional clinical environments [

36].

3.1.6. Developmental Considerations

Children's mental health needs vary significantly across developmental stages, requiring age-appropriate assessment tools and intervention approaches that many systems struggle to properly differentiate and implement [

37]. What works for an adolescent be entirely inappropriate for a young child, yet services often lack the flexibility to adequately address these differences [

38].

3.1.7. Treatment Adherence and Engagement

Even when children do access care, engagement and adherence challenges are common, with dropout rates from traditional mental health services estimated at 40-60% [

39,

40]. Factors contributing to poor engagement include practical barriers, perceived lack of cultural competence, misalignment with youth preferences, and failure to involve families effectively [

41].

The pandemic has both exacerbated these existing challenges and catalyzed innovation in service delivery models. Telehealth adoption has accelerated dramatically, demonstrating that remote care options can effectively reach some previously underserved populations [

42]. However, the rapid shift to digital platforms has also highlighted the "digital divide," with families lacking adequate technology or internet access experiencing new barriers to care [

43].

These complex and interrelated challenges in pediatric mental healthcare create both an urgent need and a fertile environment for innovative approaches that can complement traditional services, address specific access barriers, and potentially reach children and families who remain underserved by current systems [

44]. It is within this context that conversational AI applications have emerged as a potential component of more accessible, scalable, and youth-friendly mental health support infrastructure [

45].

4. Emergence of AI Conversational Agents in Mental Health

The integration of artificial intelligence into mental healthcare represents a significant evolution in digital mental health interventions. While digital tools for mental health have existed for decades—from computerized cognitive behavioral therapy programs to mobile applications for mood tracking—AI conversational agents mark a qualitative shift in how technology can simulate human-like therapeutic interactions [

46].

4.1. Historical Context and Technological Evolution

The conceptual foundation for conversational agents in mental health can be traced back to ELIZA, a computer program developed by Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT in the 1960s [

47]. ELIZA simulated a Rogerian psychotherapist using simple pattern-matching techniques to reflect user statements back as questions, creating an illusion of understanding. Despite its technical limitations, ELIZA demonstrated the potential for computer programs to engage users in therapeutic-like conversations and revealed people's tendency to anthropomorphize and disclose personal information to computer systems [

48].

Early rule-based chatbots for mental health that followed ELIZA relied on predefined scripts and decision trees, offering limited flexibility in conversations [

49]. The next generation incorporated more sophisticated natural language processing capabilities but still operated within relatively constrained conversational parameters [

50]. These systems showed promise in specific applications such as screening for mental health conditions, delivering psychoeducational content, and guiding users through structured therapeutic exercises [

51].

The landscape transformed dramatically with the advent of large language models (LLMs) based on transformer architectures, exemplified by systems like GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), Claude, and similar technologies [

52]. These models, trained on vast corpora of text from the internet and other sources, can generate contextually relevant, coherent responses without explicit programming for specific scenarios [

53]. This technological leap enabled conversational agents to engage in more natural, flexible dialogues across a wide range of topics, including sensitive mental health conversations [

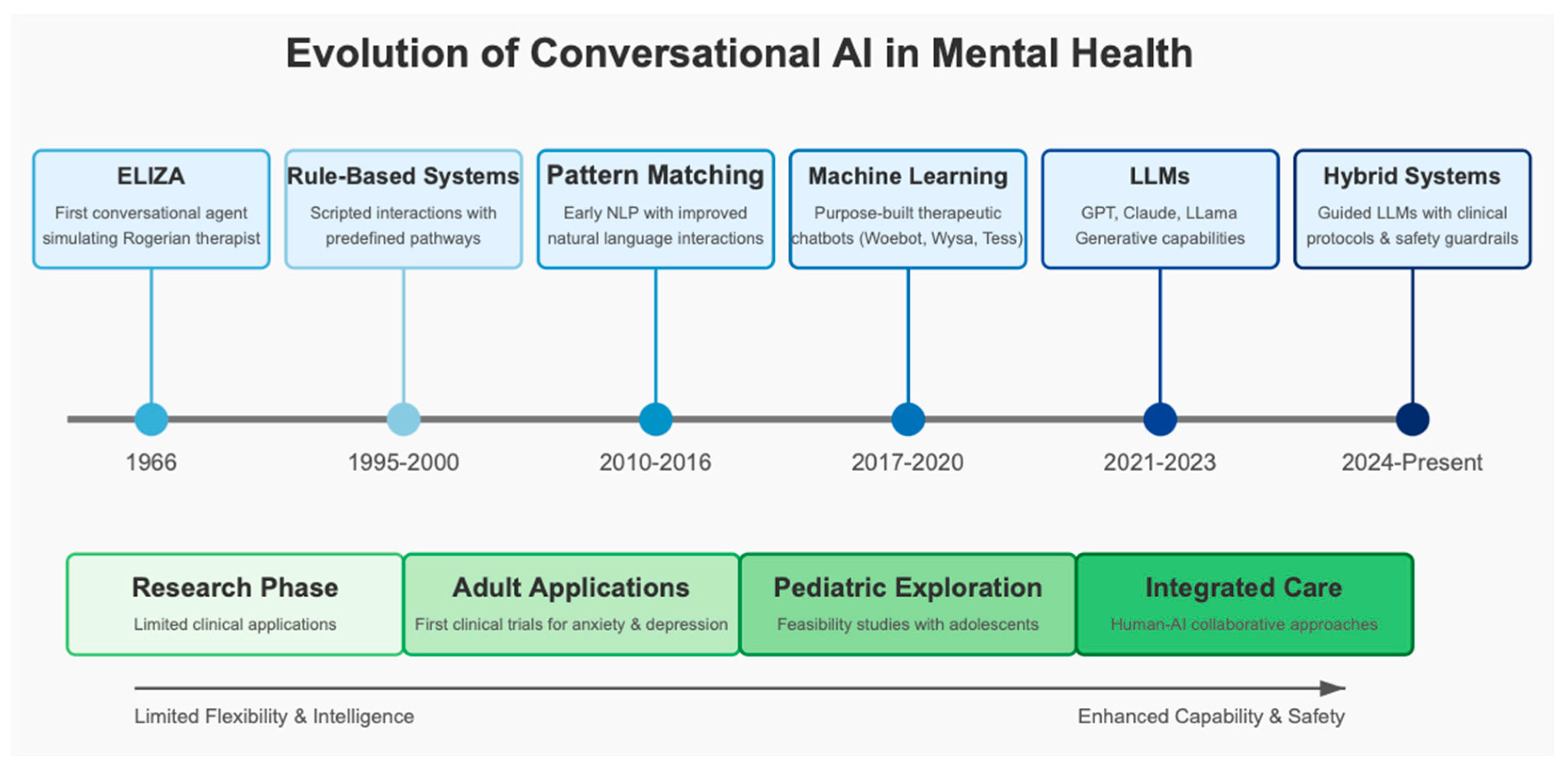

54]. As illustrated in

Figure 2, conversational AI technologies have evolved significantly since ELIZA in the 1960s, with recent developments in large language models and hybrid systems offering unprecedented capabilities while raising new considerations for pediatric applications.

4.2. Types of Conversational AI in Mental Health Applications

Current conversational AI systems in mental health contexts can be categorized based on their technological sophistication, therapeutic approach, and intended function.

4.2.1. Rule-Based Systems

Rule-based systems follow predetermined conversation flows and decision trees [

55]. While limited in handling unexpected user inputs, they offer precise control over therapeutic content and safety guardrails [

56]. Examples include Woebot and Wysa, which deliver structured cognitive-behavioral therapy exercises through guided conversations [

57].

4.2.2. Retrieval-Based Systems

Retreival-based systems select appropriate responses from a database based on user input patterns. They provide more flexibility than rule-based systems while maintaining consistency in therapeutic approaches [

58].

4.2.3. Generative AI Systems

Generative AI systems generate novel responses based on patterns learned during training rather than selecting from predefined options [

59]. Modern LLMs fall into this category, offering unprecedented conversational flexibility but raising questions about consistency and safety [

60].

4.2.4. Hybrid Approaches

Many deployed systems combine elements of these approaches, using rule-based frameworks to guide overall therapeutic structure while employing generative or retrieval-based techniques for specific conversational components [

61].

Table 1.

Comparison of conversational AI system types used in mental health applications, including their key characteristics, examples, strengths, limitations, and special considerations for pediatric applications.

Table 1.

Comparison of conversational AI system types used in mental health applications, including their key characteristics, examples, strengths, limitations, and special considerations for pediatric applications.

| Type |

Key Characteristics |

Examples in Mental Health |

Strengths |

Limitations |

Pediatric Considerations |

| Rule-Based Systems |

Predetermined conversation flows and decision trees; Script-based interactions |

Woebot, Wysa |

Precise control over therapeutic content; Safety guardrails; Consistent delivery of interventions |

Limited flexibility with unexpected user inputs; feel mechanical; Cannot easily adapt to novel situations |

Can be designed with age-appropriate content; Safety-focused; Less likely to generate inappropriate responses |

| Retrieval-Based Systems |

Select responses from existing database based on user input patterns |

Tess, Replika (in more structured modes) |

More flexible than rule-based systems; Consistency in therapeutic approach; Can incorporate evidence-based responses |

Limited to existing response database; Less adaptable to unique user needs

|

Can incorporate developmentally appropriate response sets; struggle with child-specific language patterns |

| Generative AI Systems |

Generate novel responses based on training data patterns; Not limited to predefined responses |

ChatGPT, Claude when used for mental health support |

Highly flexible conversations; Can address unexpected inputs; More natural dialogue flow |

Less predictable responses; Safety and accuracy concerns; Potential for harmful content |

Higher risk of developmentally inappropriate responses; Require substantial safety measures; Often trained primarily on adult language |

| Hybrid Approaches |

Combine rule-based frameworks with generative or retrieval capabilities |

Emerging integrated platforms; Wysa’s newer versions |

Balance of structure and flexibility; Combine safety controls with conversational naturalness |

More complex to develop and maintain; have inconsistent interaction quality |

Potentially optimal for pediatric applications; Can incorporate developmental safeguards while maintaining engagement |

Functionally, these systems serve various roles in mental health contexts:

Screening and Assessment Tools: Conversational interfaces that gather information about symptoms and experiences to support early identification of mental health concerns [

62].

Psychoeducational Agents: Systems that provide information about mental health conditions, coping strategies, and available resources through interactive dialogue rather than static content [

63].

Guided Self-Help Programs: Structured therapeutic interventions delivered through conversational interfaces, often based on evidence-based approaches like cognitive-behavioral therapy [

64].

Emotional Support Companions: Applications designed primarily for empathetic listening and validation rather than formal therapeutic interventions [

65].

Adjuncts to Traditional Therapy: Tools that complement professional care by supporting homework completion, skills practice, or monitoring between sessions [

66].

4.3. Initial Evidence in Adult Populations

Research on conversational AI for mental health has predominantly focused on adult populations, with pediatric applications emerging more recently. Several review studies have synthesized early findings from adult implementations.

Vaidyam et al. [

67] identified promising evidence for chatbot interventions in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety, with effect sizes comparable to some traditional digital interventions. User engagement metrics often exceeded those of non-conversational digital tools, suggesting that the dialogue format enhance user experience and retention.

Abd-Alrazaq et al. [

68] found that most evaluated chatbots employed cognitive-behavioral techniques, with fewer examples of other therapeutic approaches. Their review noted generally positive user satisfaction but highlighted significant methodological limitations in many studies, including small sample sizes, short follow-up periods, and lack of comparison to established interventions.

A meta-analysis by He et al. [

69] examining randomized controlled trials of conversational agents for mental health reported statistically significant short-term effects of conversational agent interventions in improving depressive symptoms, generalized anxiety symptoms, specific anxiety symptoms, quality of life or well-being, general distress, stress, mental disorder symptoms, psychosomatic disease symptoms, and negative affect.

Studies exploring user experiences have identified several potential therapeutic mechanisms. The perception of non-judgment and anonymity appears to facilitate self-disclosure, particularly regarding stigmatized topics [

70]. The 24/7 availability addresses practical barriers to traditional care, while the conversational format feel more natural and engaging than other digital interventions [

71].

These early findings with adult populations have established sufficient proof-of-concept to justify exploration in pediatric contexts, while simultaneously highlighting the need for age-specific adaptations and careful consideration of developmental factors in implementation [

72]. The transition from adult-focused to pediatric applications represents not merely a change in target population but necessitates fundamental reconsideration of content, interaction patterns, safety protocols, and ethical frameworks [

73].

The emergence of conversational AI in mental health has coincided with growing recognition of the limitations of traditional care models in meeting population-level needs, particularly for prevention and early intervention [

74]. This convergence has accelerated interest in exploring how these technologies might complement existing services within comprehensive systems of care, potentially addressing some of the access barriers and resource constraints that disproportionately affect children and adolescents [

75].

5. Evidence for Efficacy and Therapeutic Mechanisms

The evidence base for conversational AI applications in mental health is still developing, with significant variations in methodological rigor, study design, and outcome measures across investigations. This section examines the current state of evidence regarding both efficacy and the potential therapeutic mechanisms through which these systems influence mental health outcomes.

5.1. Evidence in Adult Populations

Most empirical research on conversational AI for mental health has focused on adult populations, providing an important foundation for understanding potential applications with children and adolescents. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have investigated chatbot-delivered interventions primarily for common mental health conditions:

Fitzpatrick et al. [

76] conducted an RCT of Woebot, a CBT-based chatbot, with 70 young adults experiencing symptoms of depression and anxiety. After two weeks, participants using Woebot showed significantly greater reductions in depression symptoms compared to an information control group (effect size d = 0.44). Engagement metrics were promising, with participants having an average of 12 conversations with the bot over the study period.

In a larger trial, Fulmer et al. [

77] evaluated a conversational agent delivering behavioral activation techniques to 75 adults with mild to moderate depression symptoms. The intervention group showed significantly greater improvement in depression scores at 4-week follow-up compared to a waitlist control, with improvements maintained at 8-week follow-up.

A systematic review by Gaffney et al. [

78] identified 13 RCTs of conversational agents for mental health published between 2016-2022. Across studies, small to moderate positive effects were observed for anxiety and depression compared to non-active controls. However, effects compared to active controls (e.g., self-help materials) were considerably smaller and often non-significant.

5.2. Emerging Evidence in Pediatric Populations

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being utilized in pediatric mental health care, with various studies exploring its applications, effectiveness, and ethical considerations. A longitudinal study by Vertsberger et al. [

79] examined the impact of

Kai.ai, an AI-powered chatbot delivering Acceptance Commitment Therapy (ACT) to adolescents. Conducted through self-reported mood surveys, the study found improvements in stress management and emotional well-being among users. However, limitations such as self-reporting biases and lack of long-term follow-up were noted. Ethical concerns revolved around data privacy and the absence of direct clinician oversight.

Similarly, Gual-Montolio et al. [

80] conducted a systematic review on AI-assisted psychotherapy for youth, including tools like Wysa, a chatbot employing Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). The review concluded that AI is a valuable supplement to traditional therapy but cannot replace human clinicians. It also highlighted limitations such as limited long-term efficacy data and concerns over data privacy.

Further exploring AI-based interventions, Nicol et al. [

81] conducted a feasibility and acceptability study on an AI chatbot delivering CBT to adolescents with depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study demonstrated high engagement and perceived helpfulness but faced limitations, including a small sample size and lack of a control group. Ethical considerations emphasized informed consent and safety measures. Complementing this, Yaffe et al. [

82] investigated primary care physicians’ perceptions of AI in adolescent mental health through a qualitative study. The research revealed skepticism regarding AI’s reliability, with concerns that AI could not fully replace human judgment. While physicians acknowledged the potential of AI-assisted therapy, they emphasized the need for clinical oversight.

In addition to feasibility studies, Fujita et al. [

83] explored the challenges of implementing an AI chatbot,

Emol, for adolescents on psychiatric waiting lists. The study identified technical challenges, dropout rates, and ethical concerns related to the risks of unsupervised AI therapy. The researchers emphasized that AI should be used as a supplementary tool rather than a replacement for human clinicians. Similarly, Imran et al. (2023) conducted a literature review on the use of AI-powered chatbots in child psychiatry. Their findings indicated that AI can play a role in early intervention and diagnosis but raised concerns regarding bias in AI training data and the risk of over-reliance on AI in therapy[

84].

The ethical implications of AI in pediatric psychotherapy were further explored by Moore et al. [

85] , who analyzed whether AI-powered chatbots should serve as a scaffold or substitute for human therapists. The study emphasized that AI should support rather than replace traditional therapy, highlighting issues such as parental consent and the unknown long-term effects of AI interventions. Similarly, Opel et al. [

86] examined the role of AI as a mental health therapist for adolescents, noting that AI-assisted therapy improves accessibility but requires strict regulation to mitigate risks such as misdiagnosis and the lack of human empathy.

Beaudry et al. [

87] conducted a feasibility study of a conversational agent designed to deliver mood management skills to 13 teenagers. The study demonstrated high engagement (97% completion rate) and user satisfaction, with qualitative feedback highlighting preferences for personalization and age-appropriate language.

Collectively, these studies suggest that AI-powered mental health tools can enhance accessibility and supplement traditional therapy, but they require careful implementation and ethical considerations. Issues such as data privacy, clinician oversight, and the potential for AI dependency must be addressed to ensure the safe and effective integration of AI in pediatric mental health care.

Table 2.

Selected studies investigating conversational AI applications in pediatric mental health, highlighting populations studied, methodological approaches, key findings, and limitations.

Table 2.

Selected studies investigating conversational AI applications in pediatric mental health, highlighting populations studied, methodological approaches, key findings, and limitations.

| Study |

Population |

AI System & Therapeutic Approach |

Study Design |

Key Findings |

Limitations |

| Vertsberger et al. (2023) |

Adolescents |

Kai.ai (Acceptance Commitment Therapy) |

Longitudinal study |

Improvements in stress management and emotional well-being |

Self-reporting biases; Lack of long-term follow-up |

| Gual-Montolio et al. (2024) |

Youth (various ages) |

Multiple systems including Wysa (CBT) |

Systematic review |

AI valuable as supplement to traditional therapy; Cannot replace human clinicians |

Limited long-term efficacy data |

| Nicol et al. (2023) |

Adolescents with depression and anxiety |

CBT-based chatbot |

Feasibility and acceptability study |

High engagement; Perceived helpfulness |

Small sample size; No control group |

| Yaffe et al. (2024) |

Primary care physicians providing adolescent mental health care |

N/A (Physicians’ perceptions of AI) |

Qualitative study |

Skepticism about AI reliability; Recognition of potential as supplementary tool |

Limited to physician perspectives |

| Fujita et al. (2023) |

Adolescents on psychiatric waiting lists |

Emol |

Implementation study |

Identified technical challenges and dropout rates |

Focus on implementation rather than outcomes |

| Beaudry et al. (2022) |

Teenagers |

Mood management conversational agent |

Feasibility study |

97% completion rate; High user satisfaction |

Small sample; No efficacy measures |

| Moore et al. (2024) |

Children and adolescents |

Various AI chatbots |

Ethical analysis |

AI should support rather than replace therapy; Concerns about parental consent |

Limited empirical data |

| Opel et al. (2024) |

Adolescents |

AI mental health therapist systems |

Systematic analysis |

Improved accessibility; Need for regulation to mitigate risks |

Theoretical focus; Limited experimental evidence |

5.3. Therapeutic Mechanisms

Beyond outcome measures, researchers have begun to investigate the mechanisms through which conversational AI influence mental health. Several potential therapeutic pathways have been identified.

5.3.1. Reduced Barriers to Self-Disclosure

The perception of anonymity and non-judgment appears to facilitate disclosure of sensitive information that users might hesitate to share with human providers [

88]. This fact be particularly relevant for adolescents navigating identity development and heightened sensitivity to peer evaluation [

89].

5.3.2. Cognitive Change

Structured conversational interventions based on cognitive-behavioral principles appear capable of promoting cognitive reframing and challenging maladaptive thought patterns [

32]. Text-based interactions provide opportunities for reflection and cognitive processing that differ from face-to-face exchanges [

90].

5.3.3. Emotional Validation

Analysis of user-chatbot interactions suggests that even simple acknowledgment and reflection of emotions by AI systems can provide a sense of validation that users find supportive [

91], aligning with fundamental therapeutic processes identified in human psychotherapy research.

5.3.4. Behavior Activation

Conversational agents have demonstrated effectiveness in promoting engagement in positive activities and behavioral experiments, core components of evidence-based treatments for depression [

92]. The interactive format and ability to send reminders enhance compliance with behavioral recommendations.

5.3.5. Skill Development and Practice

Regular interaction with conversational agents provides opportunities for repeated practice of coping skills and emotion regulation strategies in naturalistic contexts [

93]. This distributed practice enhance skill acquisition compared to less frequent traditional therapy sessions.

5.3.6. Bridging to Human Care

Several studies suggest that conversational agents serve as "digital gateways" that increase willingness to seek professional help among those who might otherwise avoid traditional services [

94]. This bridging function be especially valuable for adolescents who typically show low rates of help-seeking for mental health concerns [

95].

The current evidence suggests that conversational AI applications have promising potential in supporting pediatric mental health, particularly for common conditions like anxiety and depression, and for specific functions such as psychoeducation, skills practice, and bridging to professional care. However, the field remains in early stages of development, with substantial need for larger, more rigorous studies specifically designed for pediatric populations across developmental stages [

114].

6. Special Considerations for Pediatric Applications

The application of conversational AI in pediatric mental health contexts requires careful consideration of developmental, ethical, and implementation factors that differ substantially from adult applications. These special considerations must inform both research and practice to ensure that these technologies appropriately address the unique needs of children and adolescents.

6.1. Developmental Considerations

6.1.1. Cognitive and Language Development

Children's cognitive and language abilities evolve significantly throughout development, necessitating age-appropriate adjustments to conversational complexity, vocabulary, abstract concepts, and interaction patterns [

96]. What works for adolescents be incomprehensible to younger children, while content designed for younger children appear patronizing to adolescents.

6.1.2. Emotional Development

Children's ability to identify, articulate, and regulate emotions develops gradually, impacting how they express mental health concerns and engage with therapeutic content [

97]. Conversational agents must adapt to varying levels of emotional awareness and vocabulary across developmental stages.

6.1.3. Identity Formation

Adolescence in particular is characterized by intensive identity exploration and formation [

98]. Interactions with AI systems during this sensitive period influence self-concept and beliefs in ways that require careful consideration and safeguards.

6.1.4. Suggestibility and Critical Thinking

Younger children typically demonstrate greater suggestibility and less developed critical thinking skills, potentially increasing vulnerability to misinformation or inappropriate advice [

99]. This fact necessitates heightened attention to content accuracy and age-appropriate framing of information.

6.1.5. Digital Literacy

While often characterized as "digital natives," children and adolescents show significant variation in digital literacy skills that affect their ability to understand AI limitations and interpret AI-generated content appropriately [

100]. Educational components be necessary to establish appropriate expectations and boundaries.

6.1.6. Attention Span and Engagement Preferences

Children's attention spans and engagement preferences differ from adults and vary across developmental stages, requiring adaptations to conversation length, interaction style, and multimedia integration [

101]. Gamification elements enhance engagement but must be developmentally appropriate [

102].

6.2. Clinical and Therapeutic Considerations

6.2.1. Presentation of Mental Health Concerns

Mental health conditions often present differently in children than adults, with more somatic complaints, behavioral manifestations, and developmental impacts [

103]. Conversational agents must be trained to recognize and respond appropriately to these pediatric-specific presentations.

6.2.2. Assessment Challenges

Accurate assessment of mental health in children often requires multi-informant approaches (child, parent, teachers) due to varying perspectives and limited self-awareness [

104]. This complicates the design of conversational assessment tools that typically rely on single-user interaction.

6.2.3. Parental Involvement

Effective mental health interventions for children generally involve parents/caregivers, raising questions about how conversational AI should manage family involvement while respecting the child's growing autonomy and privacy needs [

105]. Different models of parent-child-AI interaction be needed across developmental stages.

6.2.4. Comorbidity and Complexity

Children with mental health concerns frequently present with comorbid conditions or complex contextual factors that exceed the capabilities of narrowly focused conversational interventions [

106]. Clear pathways for escalation to human providers are essential when complexity emerges.

6.2.5. School Context

For many children, mental health supports are accessed primarily through educational settings rather than healthcare systems [

107]. This suggests potential value in developing conversational agents specifically designed for school-based implementation with appropriate integration into existing support structures.

6.3. Safety and Ethical Considerations

6.3.1. Content Safety

Heightened responsibility exists for ensuring age-appropriate content and preventing exposure to harmful, frightening, or developmentally inappropriate information [

108]. Careful consideration of how mental health concepts are explained and discussed must be considered.

6.3.2. Crisis Detection and Response

Robust protocols for detecting and responding to crisis situations, including suicidality, abuse disclosure, or emergent safety concerns, are particularly critical in pediatric applications [

109]. Clear pathways for human intervention must exist when necessary.

6.3.3. Privacy and Confidentiality

Complex balancing is required between respecting the growing need for privacy among older children and adolescents and ensuring appropriate adult oversight for safety and care coordination [

110]. Different approaches be needed across age groups and risk levels.

6.3.4. Data Protection

Special protections apply to children's data under various regulatory frameworks (e.g., COPPA in the US, GDPR in Europe), necessitating stringent data handling practices and transparent communication about data usage [

111].

6.3.5. Developmental Impact

Long-term effects of regular interaction with AI systems during critical developmental periods remain largely unknown, necessitating ongoing monitoring and research to identify potential unintended consequences [

112].

6.3.6. Autonomy and Agency

Respect for developing autonomy requires giving children appropriate voice in decisions about using AI mental health tools while acknowledging their evolving capacity for informed consent [

113]. This balance shifts across developmental stages.

6.4. Implementation Considerations

6.4.1. Access and Equity

Digital divides affect children disproportionately, with socioeconomic factors influencing access to devices, internet connectivity, and private spaces for sensitive conversations [

114]. Implementation strategies must address these disparities to avoid exacerbating existing inequities.

6.4.2. Integration with Support Systems

For maximal effectiveness, conversational AI applications for children should integrate with existing support ecosystems including schools, primary care, mental health services, and family systems [

115]. Standalone applications have limited impact without these connections.

6.4.3. Cultural Responsiveness

Children develop within specific cultural contexts that shape understanding of mental health, help-seeking behaviors, and communication styles [

116]. Conversational agents must demonstrate cultural humility and adaptability to diverse perspectives.

6.4.4. Supervised vs. Independent Use

Decisions about whether and when children should engage with mental health AI independently versus under adult supervision require balancing safety concerns with developmental needs for privacy and autonomy [

117]. Graduated independence be appropriate across age ranges.

6.4.5. Educational Support

Implementation in pediatric contexts require more substantial educational components for both children and adults to establish appropriate expectations, boundaries, and understanding of AI limitations [

118].

These special considerations highlight the complexity of developing and implementing conversational AI for pediatric mental health. Rather than simply adapting adult-oriented systems, developmentally appropriate applications require fundamental reconsideration of design principles, content, interaction patterns, safety protocols, and implementation strategies [

119]. Successfully addressing these considerations requires interdisciplinary collaboration among developmental psychologists, pediatric mental health specialists, ethicists, technology developers, and—critically—children and families themselves.

7. Discussion

This scoping review aims to map the emerging landscape of conversational AI applications in pediatric mental health, highlighting both promising potential and significant challenges that must be addressed for responsible implementation. Several key themes have emerged across the literature that warrant further discussion.

7.1. The Promise and Limitations of Current Evidence

The evidence base for conversational AI in pediatric mental health remains nascent, with most robust empirical studies focused on adult populations. While preliminary research suggests potential benefits for addressing common mental health conditions like anxiety and depression [

120], significant gaps exist in the pediatric literature. The studies that do exist with children and adolescents are predominantly small-scale feasibility or acceptability studies rather than rigorous effectiveness trials. This pattern mirrors the historical development of digital mental health interventions more broadly, where adult applications typically precede pediatric adaptations.

The therapeutic mechanisms identified in the literature—including reduced barriers to self-disclosure, cognitive change, emotional validation, behavioral activation, skill development, and bridging to human care—align with established principles of effective mental health interventions [

121]. However, the degree to which these mechanisms operate similarly across developmental stages remains largely theoretical rather than empirically established. The field must move beyond extrapolating from adult findings to directly investigating how these mechanisms function within specific developmental contexts.

7.2. Developmental Appropriateness as a Fundamental Challenge

Perhaps the most consistent theme across the literature is the critical importance of developmental appropriateness in conversational AI applications for children and adolescents. Unlike many digital adaptations that require primarily interface modifications for younger users, conversational AI requires fundamental reconsideration of multiple dimensions including language complexity, cognitive processing, emotional development, and interaction patterns [

122]. The significant variation in capabilities across childhood and adolescence further complicates this challenge, suggesting that a developmental spectrum of conversational AI applications be necessary rather than a single pediatric approach.

Current conversational AI systems, particularly those based on large language models, are trained predominantly on adult-oriented text corpora that poorly represent children's communication patterns, concerns, and developmental needs [

123]. This foundational limitation highlights the need for specialized training approaches and careful adaptation of existing systems for pediatric applications.

7.3. Balancing Innovation with Safety and Ethics

The literature reveals the tension between the imperative for innovation to address significant unmet needs in pediatric mental health and the heightened ethical responsibilities when developing technologies for vulnerable young populations [

124]. While conversational AI offers potential solutions to persistent barriers in traditional care models—including accessibility, stigma, and resource constraints—these benefits must be weighed against risks, including privacy concerns, potential for harmful content, and the largely unknown developmental impacts of regular AI interaction.

Existing frameworks for digital ethics in healthcare typically address adult populations and inadequately account for children's unique vulnerabilities and evolving capacities. The development of pediatric-specific ethical guidelines for conversational AI represents an urgent need, with particular attention to issues of informed consent, privacy boundaries between children and parents/guardians, crisis detection protocols, and safeguards against potential developmental harm [

125].

7.4. Integration Rather than Replacement

The literature consistently emphasizes that conversational AI should function as a complement to rather than replacement for human-delivered mental health support [

126]. The most promising implementations position AI within comprehensive ecosystems of care rather than as standalone interventions, integrating with schools, primary care, specialized mental health services, and family systems [

127]. This integration approach acknowledges both the capabilities and limitations of current AI technologies while leveraging existing support structures to maximize benefits and mitigate risks.

For children in particular, the relational context of mental health support appears fundamentally important, suggesting that hybrid models combining AI and human elements prove most effective [

128]. These might include AI systems that facilitate connection to human providers, augment existing therapeutic relationships, or operate under various levels of human supervision depending on the child's age, needs, and risk level.

7.5. Equity and Access Considerations

While conversational AI potentially address some access barriers in traditional mental health care, the literature highlights concerns that without deliberate attention to equity, these technologies could exacerbate existing disparities [

129]. Digital divides affecting device access, internet connectivity, and digital literacy disproportionately impact children from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, potentially limiting the reach of AI-based interventions to those with greater resources.

Additionally, current conversational AI systems demonstrate limitations in cultural responsiveness and linguistic diversity that particularly affect children from minoritized communities [

130]. These limitations include reduced performance in non-dominant languages, cultural biases in content and interaction styles, and inadequate representation of diverse cultural conceptualizations of mental health and wellbeing. Addressing these equity concerns requires intentional design approaches that prioritize accessibility, cultural humility, and linguistic inclusivity from inception rather than as afterthoughts. Implementation strategies that specifically target underserved populations and contexts where traditional mental health resources are most limited are necessary.

7.6. Research Gaps and Future Directions

This scoping review has identified several critical gaps in the current literature that should guide future research.

Developmental Validation: Studies explicitly examining how children at different developmental stages interact with and respond to conversational AI, including potential differences in engagement patterns, comprehension, trust formation, and therapeutic benefit.

Longitudinal Outcomes: Research investigating the medium to long-term impacts of conversational AI interventions on pediatric mental health outcomes, including potential maintenance effects, habituation, or developmental influences.

Implementation Science: Studies examining how conversational AI can be effectively integrated into existing systems of care, including schools, primary care, and specialized mental health services.

Safety Monitoring: Systematic approaches to identifying and mitigating potential harms associated with conversational AI in pediatric populations, including protocols for crisis detection, content safety, and developmental impact assessment.

Equity-Focused Design and Evaluation: Research explicitly addressing how conversational AI can be designed and implemented to reduce rather than exacerbate health disparities across socioeconomic, cultural, and linguistic dimensions.

Comparative Effectiveness: Studies directly comparing conversational AI to established interventions and examining potential differential effects across developmental stages, presenting problems, and implementation contexts.

Addressing these research priorities will require interdisciplinary collaboration among developmental psychologists, pediatric mental health specialists, computer scientists, implementation researchers, ethicists, and—critically—children and families themselves. Participatory research approaches that meaningfully involve young people in design and evaluation processes be particularly valuable for ensuring that conversational AI applications meet their needs and preferences [

131].

8. Conclusions

This scoping review has mapped the emerging landscape of conversational AI applications in pediatric mental health, revealing a field with significant potential to address persistent challenges in care delivery while simultaneously navigating complex developmental, ethical, and implementation considerations.

The evidence base for conversational AI in pediatric mental health, while still developing, suggests promising applications particularly for common conditions like anxiety and depression, psychoeducation, skills practice, and facilitating connections to traditional care. However, most robust empirical research has focused on adult populations, with pediatric applications only beginning to receive focused investigation. The therapeutic mechanisms identified—including reduced barriers to self-disclosure, cognitive restructuring, emotional validation, and behavioral activation—align with established principles of effective mental health interventions but require further validation in developmental contexts.

A central finding of this review is the fundamental importance of developmental appropriateness in conversational AI design. Unlike many digital adaptations that require primarily interface modifications for younger users, conversational AI for pediatric populations demands comprehensive reconsideration of interaction patterns, language complexity, emotional processing, and safety protocols across the developmental spectrum from early childhood through adolescence.

The review emphasizes that conversational AI should function as a complement to rather than replacement for human-delivered mental health support. The most promising implementations position AI within comprehensive ecosystems of care rather than as standalone interventions, integrating with schools, primary care, specialized services, and family systems.

Critical challenges remain regarding equitable access, with potential for digital divides to limit the reach of AI-based interventions to those with greater resources. Additionally, ethical frameworks specific to pediatric applications require further development, particularly regarding privacy boundaries, informed consent processes, and safeguards against potential developmental harms.

Future research should prioritize developmental validation studies, longitudinal outcomes assessment, implementation science approaches, rigorous safety monitoring, and equity-focused design and evaluation. Interdisciplinary collaboration that meaningfully involves children and families in research and development processes will be essential to ensure that conversational AI applications effectively address the unique mental health needs of young people while mitigating potential risks.

As technological capabilities continue to advance rapidly, the field has both an opportunity and responsibility to develop conversational AI applications that thoughtfully consider the developmental, clinical, ethical, and implementation factors unique to pediatric populations. With appropriate safeguards and evidence-based implementation, conversational AI has potential to become a valuable component in addressing the significant unmet mental health needs of children and adolescents worldwide.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to this study being a review of preexisting data.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available at reasonable request to corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| CBT |

Cognitive Behavorial Therapy |

| ACT |

Acceptance Commitment Therapy |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RCT |

Randomized Controlled Trial |

| COPPA |

Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| ELIZA |

Early Natural Language Processing Computer Program |

References

- Gustavson, K.; Knudsen, A.K.; Nesvåg, R.; Knudsen, G.P.; Vollset, S.E.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T. Prevalence and stability of mental disorders among young adults: findings from a longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, P.B. Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2013, 202, s5–s10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, J. Mental Health Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am 2021, 68, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran, N.; Zeshan, M.; Pervaiz, Z. Mental health considerations for children & adolescents in COVID-19 Pandemic. Pak J Med Sci 2020, 36, S67–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toure, D.M.; Kumar, G.; Walker, C.; Turman, J.E.; Su, D. Barriers to Pediatric Mental Healthcare Access: Qualitative Insights from Caregivers. Journal of Social Service Research 2022, 48, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Tuomainen, H. Transition from child to adult mental health services: needs, barriers, experiences and new models of care. World Psychiatry 2015, 14, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorry, P.D.; Goldstone, S.D.; Parker, A.G.; Rickwood, D.J.; Hickie, I.B. Cultures for mental health care of young people: an Australian blueprint for reform. The Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, N.; Hashmi, A.; Imran, A. Chat-GPT: Opportunities and Challenges in Child Mental Healthcare. Pak J Med Sci 2023, 39, 1191–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; et al. . The now and future of ChatGPT and GPT in psychiatry. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2023, 77, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlbring, P.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.; Kleiboer, A.; Andersson, G. A new era in Internet interventions: The advent of Chat-GPT and AI-assisted therapist guidance. Internet Interv 2023, 32, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Adhikari, S. GPT-4o and multimodal large language models as companions for mental wellbeing. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 2024, 99, 104157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torous, J.; et al. . The growing field of digital psychiatry: current evidence and the future of apps, social media, chatbots, and virtual reality. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, E.; O’Neill, S.; Mulvenna, M.; Bond, R. Chatbots supporting mental health and wellbeing of children and young people; applications, acceptability and usability: European Conference on Mental Health. 20 2357.

- Jang, S.; Kim, J.-J.; Kim, S.-J.; Hong, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, E. Mobile app-based chatbot to deliver cognitive behavioral therapy and psychoeducation for adults with attention deficit: A development and feasibility/usability study. International Journal of Medical Informatic 2021, 2021, 150104440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abusamra, H.N.J.; Ali, S.H.M.; Elhussien, W.A.K.; Mirghani, A.M.A.; Ahmed, A.A.A.; Ibrahim, M.E.A. Ethical and Practical Considerations of Artificial Intelligence in Pediatric Medicine: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2025. [CrossRef]

- Meadi, M.R.; Sillekens, T.; Metselaar, S.; van Balkom, A.; Bernstein, J.; Batelaan, N. Exploring the Ethical Challenges of Conversational AI in Mental Health Care: Scoping Review. JMIR Mental Health 2025, 12, e60432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Sci 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; et al. . PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2016; 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “CHILD AND ADOLESCENT MENTAL HEALTH. in 2022 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report [Internet], Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2022. Accessed: 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK587174/.

- Buecker, S.; Petersen, K.; Neuber, A.; Zheng, Y.; Hayes, D.; Qualter, P. A systematic review of longitudinal risk and protective factors for loneliness in youth. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2024, 1542, 620–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabarali, A.; Williams, J.W. Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Adolescents’ Mental Health Based on Coping Behavior - Statistical Perspective. Adv. Data Sci. Adapt. Data Anal. 2024, 16, 2450003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, T.R.; Choi, K.R.; Elmore, J.G.; Dudovitz, R. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Receipt of Pediatric Mental Health Care. Academic Pediatrics 2024, 24, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichett, L.M.; et al. . Racial and Gender Disparities in Suicide and Mental Health Care Utilization in a Pediatric Primary Care Setting. Journal of Adolescent Health 2024, 74, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. . Disparities and Medical Expenditure Implications in Pediatric Tele-Mental Health Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Mississippi. J Behav Health Serv Res 2025, 52, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, D.R. Availability and Accessibility of Mental Health Services for Youth: A Descriptive Survey of Safety-Net Health Centers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Community Ment Health J 2024, 60, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, J.A.; Attridge, M.M.; Carroll, M.S.; Simon, N.-J.E.; Beck, A.F.; Alpern, E.R. Association of Youth Suicides and County-Level Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas in the US. JAMA Pediatrics 2023, 177, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaligram, D.; et al. . ‘Building’ the Twenty-First Century Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist. Acad Psychiatry 2022, 46, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.A.; et al. . Disparities in Pediatric Mental and Behavioral Health Conditions. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2022058227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluyede, L.; Cochran, A.L.; Wolfe, M.; Prunkl, L.; McDonald, N. Addressing transportation barriers to health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives of care coordinators. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2022, 159, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringewatt, E.H.; Gershoff, E.T. Falling through the cracks: Gaps and barriers in the mental health system for America’s disadvantaged children. Children and Youth Services Review 2010, 32, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Surgeon General (OSG), Protecting Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. in Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services, 2021. Accessed: 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK575984/.

- Johnson, C.L.; Gross, M.A.; Jorm, A.F.; Hart, L.M. Mental Health Literacy for Supporting Children: A Systematic Review of Teacher and Parent/Carer Knowledge and Recognition of Mental Health Problems in Childhood. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2023, 26, 569–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, K.; Huxley, E.; Townsend, M.L. Mental health help seeking in young people and carers in out of home care: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review 2021, 127, 106088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viksveen, P.; et al. . User involvement in adolescents’ mental healthcare: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2022, 31, 1765–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. A. Henning, The Complete Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding, Supporting, and Nurturing Young Minds. Winifred Audrey Henning.

- Ratheesh, A.; Loi, S.M.; Coghill, D.; Chanen, A.; McGorry, P.D. Special Considerations in the Psychiatric Evaluation Across the Lifespan (Special Emphasis on Children, Adolescents, and Elderly). in Tasman’s Psychiatry, A. Tasman, M. B. Riba, R. D. Alarcón, C. A. Alfonso, S. Kanba, D. M. Ndetei, C. H. Ng, T. G. Schulze, and D. Lecic-Tosevski, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 1–37. [CrossRef]

- Lehtimaki, S.; Martic, J.; Wahl, B.; Foster, K.T.; Schwalbe, N. Evidence on Digital Mental Health Interventions for Adolescents and Young People: Systematic Overview. JMIR Mental Health 2021, 8, e25847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilles, M.R.; Anderson, M.; Li, S.H.; Subotic-Kerry, M.; Parker, B.; O’Dea, B. Adherence to e-mental health among youth: Considerations for intervention development and research design. DIGITAL HEALTH 2020, 62055207620926064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellström, L.; Beckman, L. Life Challenges and Barriers to Help Seeking: Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Voices of Mental Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 13101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzner, M.; Cuffee, Y. Telehealth Interventions and Outcomes Across Rural Communities in the United States: Narrative Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2021, 23, e29575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.E.; Lai, A.Y.; Gupta, A.; Nguyen, A.M.; Berry, C.A.; Shelley, D.R. Rapid Transition to Telehealth and the Digital Divide: Implications for Primary Care Access and Equity in a Post-COVID Era. The Milbank Quarterly 2021, 99, 340–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, T.D.; Boyd, R.C.; Njoroge, W.F.M. Addressing the Global Crisis of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. JAMA Pediatrics 2021, 175, 1108–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhugra, D.; Moussaoui, D.; Craig, T.J. , Oxford Textbook of Social Psychiatry. Oxford University Press, 2022.

- Li, H.; Zhang, R.; Lee, Y.-C.; Kraut, R.E.; Mohr, D.C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of AI-based conversational agents for promoting mental health and well-being. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, D.M. The Limits of Computation: Joseph Weizenbaum and the ELIZA Chatbot. Weizenbaum Journal of the Digital Society 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, S.G.; et al. . When ELIZA meets therapists: A Turing test for the heart and mind. PLOS Ment Health 2025, 2, e0000145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisha, M.A.; Jamei, R.B. Conversational AI Revolution: A Comparative Review of Machine Learning Algorithms in Chatbot Evolution. East Journal of Engineering 2025, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rajaraman, V. From ELIZA to ChatGPT. Reson 2023, 28, 889–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Thakur, J.; Mohan, Y. A Historical Analysis of Chatbots from Eliza to Google Bard. Proceedings of Fifth Doctoral Symposium on Computational Intelligence, A. Swaroop, V. Kansal, G. Fortino, and A. E. Hassanien, Eds., 2024, Singapore: Springer Nature; pp. 15–39. [CrossRef]

- Annepaka, Y.; Pakray, P. Large language models: a survey of their development, capabilities, and applications. Knowl Inf Syst 2025, 67, 2967–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, J.; Tan, M. Modern AI Unlocked: Large Language Models and the Future of Contextual Processing. Baltic Multidisciplinary Research Letters Journal 2025, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, E.M.; et al. . Artificially intelligent chatbots in digital mental health interventions: a review. Expert Review of Medical Devices 2021, 18, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Waa, J.; Nieuwburg, E.; Cremers, A.; Neerincx, M. Evaluating XAI: A comparison of rule-based and example-based explanations. Artificial Intelligenc 2021, 291, 103404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; et al. . Safeguarding Large Language Models: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.02622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagwala, M.K.; Asher, R. Conversational Artificial Intelligence and Distortions of the Psychotherapeutic Frame: Issues of Boundaries, Responsibility, and Industry Interests. The American Journal of Bioethics 2023, 23, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Dou, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wen, J.-R. Learning Implicit User Profile for Personalized Retrieval-Based Chatbot. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, in CIKM ’21. New York, NY, 2021, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; pp. 1467–1477. [CrossRef]

- Bandi, A.; Adapa, P.V.S.R.; Kuchi, Y.E.V.P.K. The Power of Generative AI: A Review of Requirements, Models, Input–Output Formats, Evaluation Metrics, and Challenges. Future Internet 2023, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Esmaeilzadeh, P. Generative AI in Medical Practice: In-Depth Exploration of Privacy and Security Challenges. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2024, 26, e53008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beredo, J.L.; Ong, E.C. Analyzing the Capabilities of a Hybrid Response Generation Model for an Empathetic Conversational Agent. Int. J. As. Lang. Proc. 2022, 32, 2350008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, L.; De Leo, D. Human-Computer Interaction in Digital Mental Health. Informatics 2022, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, S.M.; Maskeliūnas, R.; Damaševičius, R. Dialogue agents for artificial intelligence-based conversational systems for cognitively disabled: a systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 2024, 19, 1059–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, K.K.; Darcy, A.; Vierhile, M. Delivering Cognitive Behavior Therapy to Young Adults With Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety Using a Fully Automated Conversational Agent (Woebot): A Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mental Health 2017, 4, e7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.; Liao, L.; Zhou, Z.; Ngo, C.-W.; Hong, R. Towards Multimodal Emotional Support Conversation Systems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.03650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; et al. A Generic Review of Integrating Artificial Intelligence in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:arXiv:2407.19422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyam, A.N.; Wisniewski, H.; Halamka, J.D.; Kashavan, M.S.; Torous, J.B. Chatbots and Conversational Agents in Mental Health: A Review of the Psychiatric Landscape. Can J Psychiatry 2019, 64, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Alrazaq, A.A.; Alajlani, M.; Ali, N.; Denecke, K.; Bewick, B.M.; Househ, M. Perceptions and Opinions of Patients About Mental Health Chatbots: Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2021, 23, e17828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; et al. . Conversational Agent Interventions for Mental Health Problems: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2023, 25, e43862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubin, C.; Rodriguez, J.P.M.; de Marchi, A.C.B. User experience with conversational agent: a systematic review of assessment methods. Behaviour & Information Technology 2022, 41, 3519–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardine, J.; Nadal, C.; Robinson, S.; Enrique, A.; Hanratty, M.; Doherty, G. Between Rhetoric and Reality: Real-world Barriers to Uptake and Early Engagement in Digital Mental Health Interventions. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2024, 31, 27:1–27:59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugnot-Cerioli, M.; Laurenty, O.M. The Future of Child Development in the AI Era. Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives Between AI and Child Development Experts. arXiv, 2019; arXiv:2405.19275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, N.; Madhavan, R.; Weleff, J. Digital Dialogue—How Youth Are Interacting With Chatbots. JAMA Pediatrics 2024, 178, 429–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, K. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Mental Health: A Review. Science Insights 2023, 43, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, A.C.; et al. . A Call to Action on Assessing and Mitigating Bias in Artificial Intelligence Applications for Mental Health. Perspect Psychol Sci 2023, 18, 1062–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K.K.; Darcy, A.; Vierhile, M. Delivering Cognitive Behavior Therapy to Young Adults With Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety Using a Fully Automated Conversational Agent (Woebot): A Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mental Health 2017, 4, e7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulmer, R.; Joerin, A.; Gentile, B.; Lakerink, L.; Rauws, M. Using Psychological Artificial Intelligence (Tess) to Relieve Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mental Health 2018, 5, e9782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, H.; Mansell, W.; Tai, S. Conversational Agents in the Treatment of Mental Health Problems: Mixed-Method Systematic Review. JMIR Mental Health 2019, 6, e14166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertsberger, D.; Naor, N.; Winsberg, M. Adolescents’ Well-being While Using a Mobile Artificial Intelligence–Powered Acceptance Commitment Therapy Tool: Evidence From a Longitudinal Study. JMIR AI 2022, 1, e38171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gual-Montolio, P.; Jaén, I.; Martínez-Borba, V.; Castilla, D.; Suso-Ribera, C. Using Artificial Intelligence to Enhance Ongoing Psychological Interventions for Emotional Problems in Real- or Close to Real-Time: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2022; 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, G.; Wang, R.; Graham, S.; Dodd, S.; Garbutt, J. Chatbot-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Adolescents With Depression and Anxiety During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Feasibility and Acceptability Study. JMIR Formative Research 2022, 6, e40242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadiri, P.; Yaffe, M.J.; Adams, A.M.; Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi, S. Primary care physicians’ perceptions of artificial intelligence systems in the care of adolescents’ mental health. BMC Prim. Care, 2024; 25, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, J.; et al. Challenges in Implementing an AI Chatbot Intervention for Depression Among Youth on Psychiatric Waiting Lists: A Study Termination Report”.

- Imran, N.; Hashmi, A.; Imran, A. Chat-GPT: Opportunities and Challenges in Child Mental Healthcare. Pak J Med Sci 2023, 39, 1191–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, B.; Herington, J.; Tekin, Ş. The Integration of Artificial Intelligence-Powered Psychotherapy Chatbots in Pediatric Care: Scaffold or Substitute? The Journal of Pediatrics 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opel, D.J.; Kious, B.M.; Cohen, I.G. AI as a Mental Health Therapist for Adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics 2023, 177, 1253–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudry, J.; Consigli, A.; Clark, C.; Robinson, K.J. Getting Ready for Adult Healthcare: Designing a Chatbot to Coach Adolescents with Special Health Needs Through the Transitions of Care. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 2019; 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papneja, H.; Yadav, N. Self-disclosure to conversational AI: a literature review, emergent framework, and directions for future research. Pers Ubiquit Comput, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, L.H. The Teenage Brain: Sensitivity to Social Evaluation. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2013, 22, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehrwald, B. Understanding social presence in text-based online learning environments. Distance Education 2008, 29, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shafei, M. Navigating Human-Chatbot Interactions: An Investigation into Factors Influencing User Satisfaction and Engagement. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2025, 41, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-González, I.; Pacheco-Lorenzo, M.R.; Fernández-Iglesias, M.J.; Anido-Rifón, L.E. Conversational agents for depression screening: A systematic review. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 2024; 181, 105272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Car, L.T.; et al. . Conversational Agents in Health Care: Scoping Review and Conceptual Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2020; 22, e17158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, R.; Dobrean, A.; Poetar, C.R. Use of automated conversational agents in improving young population mental health: a scoping review. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Gaur, M.; Chen, L.K.; Garg, M.; Srivastava, B. A review of the explainability and safety of conversational agents for mental health to identify avenues for improvement. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1229805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R.; Norbury, C. , Language Disorders from Infancy Through Adolescence - E-Book: Language Disorders from Infancy Through Adolescence - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2012.

- Cole, P.M.; Michel, M.K.; Teti, L.O. The Development of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: A Clinical Perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 1994; 59, 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E. Identity Formation in Adolescence: The Dynamic of Forming and Consolidating Identity Commitments. Child Development Perspectives 2017, 11, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemfuss, J.Z.; Olaguez, A.P. Individual Differences in Children’s Suggestibility: An Updated Review. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 2020, 29, 158–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; et al. . Children as creators, thinkers and citizens in an AI-driven future. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2021; 2, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]