1. Introduction

Peer-to-peer (P2P) lending, also known as social lending, is an online financial service that directly connects borrowers and lenders without traditional intermediaries, such as banks [

1]. By leveraging digital platforms and social media, P2P lending democratizes access to credit, promoting financial inclusion. Since its inception with Zopa in the United Kingdom in 2005 [

2], platforms like Lending Club, Prosper, and Funding Circle have facilitated billions of dollars in loans, highlighting the global reach and potential of this lending model. Despite its rapid growth, P2P lending faces significant challenges, particularly information asymmetry and rising default rates, which threaten platform stability and profitability [

3,

4].

To mitigate these risks, P2P platforms utilize internal credit scoring systems, framing credit risk assessment as a binary classification problem. In this context, loan repayment status serves as the target variable, where fully repaid loans are labeled ’0’ and unpaid loans ’1’ [

5].

Historically, creditworthiness was assessed using traditional methods such as FICO (Fair Isaac Corporation) scores and subjective judgment. However, these approaches often fail to capture complex borrower behaviors and non-linear interactions. In response, statistical and machine learning models have emerged, offering enhanced predictive performance and interpretability by evaluating high-dimensional borrower attributes, dynamic credit behaviors, and intricate correlations.

Among these, ensemble learning methods have shown superior performance by aggregating predictions from multiple base models, thereby capturing complex patterns and improving the identification of minority class instances, such as loan defaults [

6]. Ensemble models, including XGBoost and LightGBM, have demonstrated exceptional accuracy in credit risk modeling, outperforming traditional statistical methods [

10]. However, their effectiveness is highly sensitive to hyperparameter selection, which controls the learning process and model complexity. Improper tuning can lead to poor generalization, either by premature convergence or overfitting the training data. Therefore, optimizing hyperparameters is essential to maximize predictive performance and computational efficiency.

According to Lessmann et al. [

10], ensemble methods consistently outperform individual machine learning and statistical models, offering superior predictive accuracy. However, their performance is highly sensitive to hyperparameter selection, including learning rates, tree depths, and regularization terms. Proper hyperparameter optimization is crucial for maximizing predictive performance in credit risk modeling, as hyperparameters govern the learning process and control the complexity of both individual models and the ensemble. For example, an excessively high learning rate can cause premature convergence, leading to missed patterns associated with potential defaults. In contrast, an overly complex architecture, such as deep decision trees, may overfit the training data, compromising the model’s ability to generalize to new and unseen loan applications.

In P2P lending, even marginal improvements in default prediction accuracy can lead to significant economic benefits, such as reduced lender exposure and enhanced platform stability [

7,

8]. However, exhaustive hyperparameter searches are computationally expensive, while suboptimal configurations can degrade model performance. Therefore, selecting an appropriate tuning method is crucial. Furthermore, the choice of hyperparameter optimization strategy influences feature importance rankings, impacting model interpretability and the prioritization of risk factors [

9]. Despite its importance, the impact of tuning methods on feature selection and model explainability remains underexplored.

This study addresses these gaps by systematically comparing three widely used hyperparameter tuning strategies—Grid Search, Random Search, and Optuna [

10]—across XGBoost, LightGBM, and Logistic Regression models. Using the Lending Club dataset, this research investigates the trade-offs between predictive performance and computational efficiency, addressing the specific challenges of information asymmetry and class imbalance in P2P lending.

A key contribution of this study is the demonstration that Optuna significantly outperforms Grid Search and Random Search in computational efficiency while maintaining comparable predictive accuracy. Specifically, Optuna is 10.7 times faster than Grid Search for XGBoost and 40.5 times faster for LightGBM, highlighting the potential of Bayesian optimization in large-scale credit risk modeling. Additionally, this research explores how different hyperparameter tuning methods impact model interpretability and feature importance rankings. The findings reveal that variations in feature importance influence the prioritization of risk factors, which is crucial for transparent and interpretable credit scoring models.

Moreover, the study addresses class imbalance by employing random undersampling and evaluates model performance using balanced metrics such as G-mean, sensitivity, and specificity. This approach ensures effective identification of both defaulting and non-defaulting loans, enhancing predictive robustness and decision-making.

By providing a comprehensive comparison of hyperparameter tuning methods and examining their impact on model performance and interpretability, this study advances the literature on credit risk modeling. It also offers practical implications for financial institutions and P2P lending platforms seeking to optimize credit scoring models efficiently.

This research is guided by the following questions:

Which hyperparameter tuning method provides the best trade-off between computational efficiency and predictive performance in credit scoring for P2P lending?

Does feature importance vary depending on the choice of hyperparameter tuning method, and if so, how does this impact model interpretability and performance?

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on P2P lending, default prediction, and machine learning applications in credit risk.

Section 3 outlines the data preprocessing and model construction methodology.

Section 4 presents the experimental setup, while

Section 5 discusses the results. Finally,

Section 6 concludes with implications for future research.

2. Related Work

Peer-to-peer lending has garnered significant attention for its potential to democratize access to credit by providing faster and more flexible funding solutions. However, the absence of collateral and limited regulatory oversight expose the industry to considerable credit risk, necessitating robust methods to predict loan defaults accurately. Traditionally, online financial platforms have relied on quantitative credit scoring systems, such as FICO scores, or proprietary metrics like the Lending Club (LC) score. While these methods offer initial assessments of borrower creditworthiness, they fall short in accurately predicting default risk. Their reliance on general risk scores limits their ability to capture the nuanced interactions between variables, leaving investors with insufficient confidence in the borrower’s reliability [

11].

In response to these limitations, P2P platforms have begun framing credit evaluation as a binary classification task, where the goal is to predict the likelihood of default based on borrower demographics and financial data. Early studies utilized statistical techniques such as logistic regression (LR) and discriminant analysis (LDA) to estimate default probabilities [

12,

19]. While these methods proved effective in identifying key predictive variables, their assumption of linear relationships limited their applicability to complex, high-dimensional datasets.

2.1. Machine Learning for Credit Scoring

Machine learning techniques have emerged as a promising alternative for credit risk prediction. Methods such as decision trees (DT), support vector machines (SVM), and artificial neural networks (ANN) have shown significant improvements in predictive performance [

10]. For example, Teply and Polena [

13] conducted a comparative evaluation of ten classifiers—including logistic regression, artificial neural networks, support vector machines, random forests, and Bayesian networks—on the Lending Club dataset spanning 2009–2013. They found that logistic regression achieved the highest classification accuracy. However, in a similar analysis of the same dataset, Malekipirbazari and Aksakalli [

11] discovered that random forests outperformed both logistic regression and FICO scores.

Numerous studies have performed comparative evaluations to identify the best algorithm for classification tasks. Lessmann et al. [

10] assessed 41 classification techniques across eight credit scoring datasets. Their study explored advanced approaches, such as heterogeneous ensembles, rotation forests, and extreme learning machines, while using robust performance measures like the H-measure and partial Gini index. The findings highlight the superiority of ensemble models over traditional methods, offering valuable insights for improving credit risk modeling.

2.2. Ensemble Models for Credit Scoring

Building on these advancements, ensemble learning has become a widely adopted approach for credit risk modeling. Techniques such as random forests and gradient boosting combine multiple base models to enhance predictive accuracy and robustness. By integrating diverse algorithms that evaluate various hypotheses, these models produce more reliable predictions, leading to improved accuracy and reliability [

7,

8]. Ensemble methods are generally categorized into parallel and sequential structures. Parallel ensembles, like bagging and random forests, combine independently trained models to make collective decisions simultaneously. In contrast, sequential ensembles, such as boosting algorithms, iteratively refine models by correcting errors from previous iterations.

Ma et al. [

15] highlighted LightGBM’s computational efficiency, showing it achieves comparable accuracy to extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) while running ten times faster. Similarly, Ko et al. [

14] benchmarked three statistical models—logistic regression, Bayesian classifier, and linear discriminant analysis—alongside five machine learning models: decision tree, random forest, LightGBM, artificial neural network, and convolutional neural network (CNN) using the Lending Club dataset. Their findings showed that LightGBM outperformed the other models, achieving a 2.91% improvement in accuracy. However, the study did not consider hyperparameter tuning strategies, which could significantly affect model performance. Additionally, their focus on classification accuracy overlooked computational efficiency, a crucial factor for real-world deployment.

2.3. Challenges in Social Lending Datasets

A persistent challenge in Peer-to-Peer lending datasets is class imbalance, where the majority of loans do not default [

5,

6]. This imbalance causes models to be biased toward the majority class, leading to reduced sensitivity toward the minority class [

14,

16]. This issue is particularly critical for predicting defaults, as failing to identify defaulted loans can expose lenders to significant financial risks [

6]. Traditional machine learning models often assume equal class distributions and focus on optimizing overall accuracy, rather than prioritizing balanced performance metrics such as sensitivity, specificity, or the geometric mean (G-Mean) [

18,

19].

Resampling techniques such as oversampling, undersampling, and hybrid methods have emerged as effective solutions to address class imbalance [

17]. Oversampling methods, like the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE), generate synthetic examples to augment the minority class, while undersampling reduces the majority class, retaining all minority class samples to achieve balance. KrishnaVeni and Sobha Rani [

18] identified three main reasons why traditional classification algorithms struggle with imbalanced data: (1) they are primarily accuracy-driven, often favoring the majority class; (2) they assume an equal distribution of classes, which is rarely the case in imbalanced datasets; and (3) they treat the misclassification error costs of all classes as equal. To overcome these challenges, the study recommended the use of sampling strategies and cost-sensitive learning techniques. Additionally, alternative performance metrics, such as the confusion matrix, precision, and F1-score, were used to better evaluate models on imbalanced datasets.

In another study, Alam et al. [

7] investigated credit card default prediction using imbalanced datasets, with a focus on enhancing classifier performance while preserving model interpretability. Using datasets like the South German Credit and Belgium Credit data, the study addressed the challenge of class imbalance through various resampling techniques. Gradient-boosted decision trees (GBDT) were used as the primary model, with hyperparameter tuning of learning rates and the number of trees to improve predictive accuracy. The K-means SMOTE oversampling technique demonstrated significant improvements in G-mean, precision, and recall, effectively addressing the issue of class imbalance.

Several studies have specifically utilized the Lending Club dataset to explore and benchmark methods for addressing class imbalance in credit risk prediction. Moscato et al. [

5] highlighted the bias of machine learning models toward the majority class in imbalanced settings. To counter this, they employed oversampling techniques like SMOTE, alongside undersampling methods, on the Lending Club data. The study demonstrated significant improvements in default prediction by using a random forest classifier combined with these resampling techniques. Additionally, several explainability methods, such as LIME and SHAP, were incorporated to enhance model transparency.

Similarly, Namvar et al. [

19] investigated the effectiveness of resampling strategies, such as random undersampling and oversampling, combined with machine learning classifiers like logistic regression and random forests. Their findings underscored the importance of metrics such as G-mean, which balance sensitivity and specificity, in effectively addressing imbalanced datasets. The results indicated that combining random forests with random undersampling could be a promising approach for assessing credit risk in social lending markets. Song et al. [

20] adopted a different approach by introducing an ensemble-based methodology, DM-ACME, which leverages multi-view learning and adaptive clustering to increase base learner diversity. This method showed superior sensitivity and adaptability in default identification, outperforming traditional classifiers in highly imbalanced settings.

While addressing class imbalance is crucial, it is not sufficient for optimizing predictive performance in P2P lending datasets due to the complexities introduced by high dimensionality and intricate feature interactions. Hyperparameter tuning offers a complementary approach that improves model sensitivity and accuracy, particularly in the context of imbalanced data. Huang and Boutros [

21] highlighted that optimal hyperparameters often vary across datasets, underscoring the importance of tailoring tuning strategies to the specific characteristics of each dataset.

Advanced methods like Optuna, which utilizes Bayesian optimization, have proven superior to traditional tuning techniques. Chang et al. [

23] emphasized the effectiveness of combining models, such as random forests (RF) and logistic regression (LR), to predict loan defaults. Their analysis, using the Lending Club dataset from 2007 to 2015, found that LR, enhanced with misclassification penalties and Gaussian Naive Bayes, achieved competitive performance, with Naive Bayes showing the highest specificity. The study also highlighted the crucial role of hyperparameter tuning, especially for support vector machines (SVM), where kernel selection and regularization parameters significantly impact model performance.

Xia et al. [

22] aimed to develop an accurate and interpretable credit scoring model using XGBoost, with a focus on hyperparameter tuning and sequential model building. Using datasets from a publicly available credit scoring competition that featured class imbalance, the authors employed Bayesian optimization, specifically the tree-structured Parzen estimator (TPE), for adaptive hyperparameter tuning. The study demonstrated that Bayesian hyperparameter optimization significantly improved SVM performance compared to manual tuning, grid search, and random search, with Bayesian optimization yielding approximately 5% better results than grid and manual searches, and 3% better than random search. Additionally, the study examined feature importance but focused only on models optimized using TPE. However, the research did not explore whether different hyperparameter optimization methods affect feature rankings.

The studies reviewed highlight the increasing focus on hyperparameter tuning in credit scoring, especially in relation to ensemble models. This study explores the relationships between three established tuning methods applied to the XGBoost and LightGBM frameworks, with an emphasis on their computational costs, accuracy, and impact on feature importance rankings. Additionally, our study covers the entire modeling process, including feature selection, addressing class imbalance, automatic hyperparameter tuning, training, and evaluation.

3. Methods

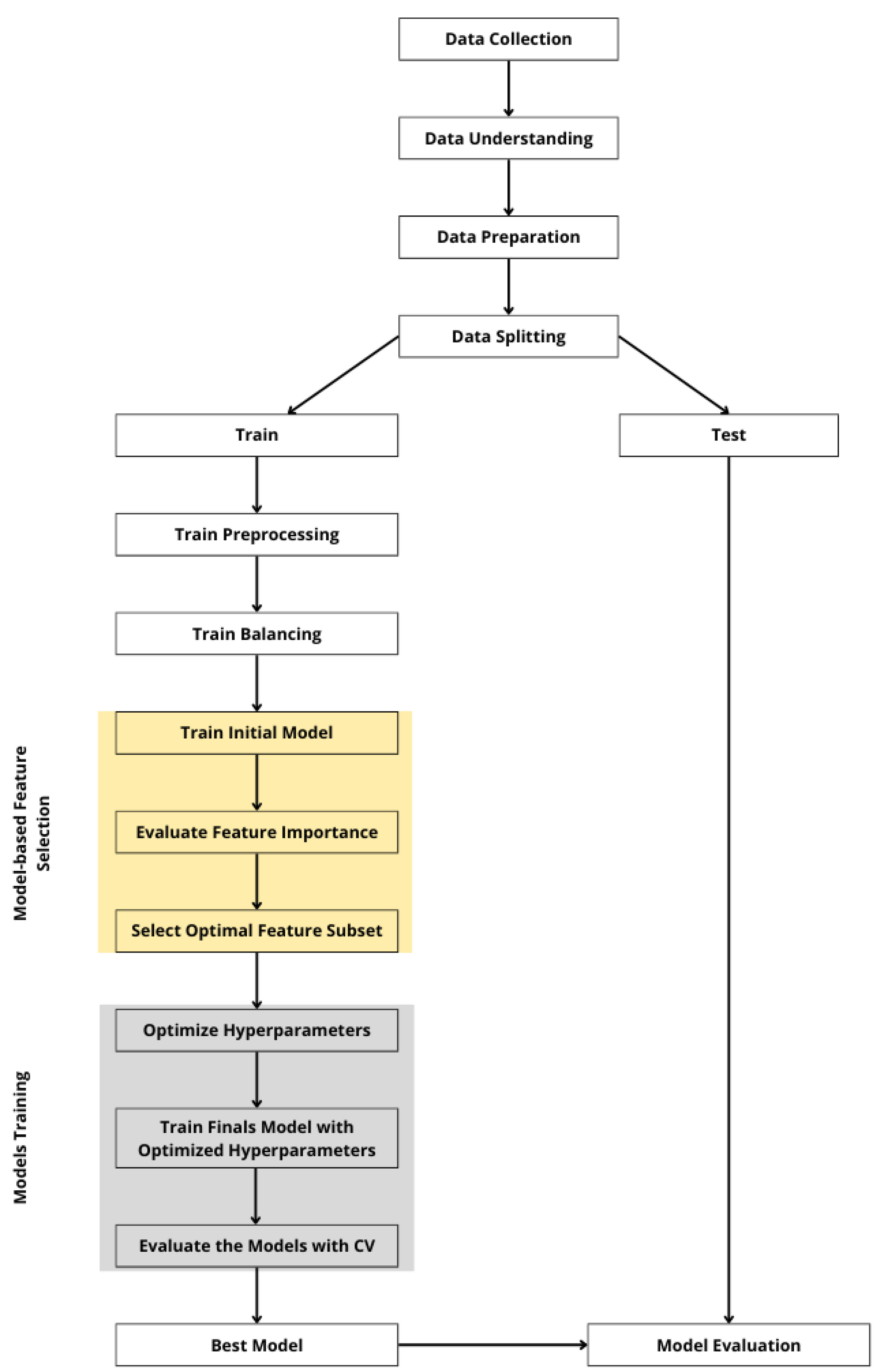

Ensemble models are powerful machine learning algorithms with numerous hyperparameters, and their configuration is key to optimizing predictive performance. In this paper, Optuna is used to tune the hyperparameters of three predictive models. Additionally, grid search and random search are benchmarked as baseline optimization methods, with identical parameter search intervals for comparison. Grid search was selected for its comprehensive coverage of the parameter space and its common use in prior research. Random search presents an efficient alternative, achieving comparable results more effectively. Optuna, on the other hand, represents an advanced method of Bayesian optimization. The experimental design is illustrated in

Figure 1.

The study uses the publicly available Lending Club dataset, widely recognized in peer-to-peer credit risk research for its comprehensiveness and reliability. During the data preprocessing phase, common challenges such as missing values, redundancy, class imbalance, and data leakage are addressed. Redundant attributes, which convey similar information, are removed, leaving only the most representative features. Numerical variables are scaled, and multicollinearity is analyzed. To enhance storage and processing efficiency, certain object features are converted to categorical types, and floating-point features requiring integer representation are identified and adjusted accordingly.

Class imbalance in the dataset is addressed through random undersampling, ensuring that the training set is fully balanced while the test set retains its original distribution. This approach helps maintain evaluation metrics that reflect real-world lending scenarios. Next, feature selection is applied to filter out unrepresentative features. Data leakage is systematically identified and excluded by analyzing feature importance scores from a tree-based model, with features showing unusually high importance flagged as potential sources of leakage. Additionally, feature engineering is used to introduce interaction terms, enhancing the predictive capacity of the models.

In the final step, three hyperparameter tuning methods are employed to optimize the parameters of the prediction models: grid search, random search, and Optuna. Grid search exhaustively evaluates all possible parameter combinations, while random search offers a more computationally efficient alternative by sampling random combinations. Optuna, a Bayesian optimization technique, iteratively selects and evaluates promising configurations based on the estimated probability density function (PDF) and the expected improvement (EI) metric. Optuna begins by recording the model settings and corresponding 3-fold cross-validation performance (e.g., logistic loss) in a dataset H. At each iteration, Optuna estimates the PDF of each hyperparameter using a Parzen estimator. It then computes the joint density function for potential hyperparameter combinations and selects the most promising configurations by maximizing the expected improvement metric. These configurations are evaluated, and their performance is added to the dataset H. The process of selecting, evaluating, and updating H continues until a predefined limit is reached. Through this iterative process, Optuna efficiently explores the hyperparameter space and identifies the optimal configurations to maximize model performance.

After hyperparameter tuning, each model is trained using the optimized parameters and the refined feature subset. This step results in a fully trained model with the best features and parameters for prediction. The final models are then evaluated on the test set using metrics such as the area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, and G-mean.

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Dataset

This study utilizes a publicly available dataset from Lending Club

1, one of the largest peer-to-peer lending platforms in the United States. Widely recognized as a benchmark for credit risk analysis, the dataset comprises 2,925,493 records and 141 features, collected between 2007 and the third quarter of 2020. The LC dataset includes a diverse range of borrower and financial characteristics, providing detailed information on loan amounts, interest rates, credit histories, and borrower demographics. Key attributes include seven loan statuses such as "Fully Paid," "Charged Off," "Default," and various stages of delinquency. Following Namvar et al. [

19], we treat these loan statuses as the target class, categorizing them into two classes to align with the binary classification objectives of this study. The possible values for each class are shown in

Table 1.

The features retained for analysis offer a comprehensive view of the borrower’s profile and financial behavior. Loan-specific variables include loan amount, term length, interest rate, and loan grade, which are classified from A to G, with grades B and C being the most common. Borrower characteristics include annual income, homeownership status (classified into six categories), and employment duration. Credit history indicators, such as FICO score, debt-to-income ratio, and the number of open credit lines, provide additional insights into financial reliability. Payment history features, including late payments and total outstanding balances, further enrich the dataset by reflecting the borrower’s ongoing financial health. To ensure compatibility with machine learning models, categorical variables were converted to ordinal format. Finally, irrelevant features, such as loan IDs and payment dates, were removed.

4.1.1. Data Preprocessing and Feature Selection

The dataset underwent thorough preprocessing to address common challenges such as missing data, redundancy, class imbalance, and data leakage. Features with more than 50% missing values were removed. Redundant attributes, such as "funded_amnt," "funded_amnt_inv," and "loan_amnt," which recorded similar information, were identified using the Lending Club data dictionary, and only one was retained. Numerical variables were scaled using a robust scaler to minimize the impact of outliers. A multicollinearity analysis was then performed, and variables with correlation coefficients above 95% were excluded to reduce redundancy and improve interpretability. Misclassified object features were converted to categorical types to optimize memory usage and processing speed, while incorrectly specified float features were corrected to integers.

Data leakage was identified during preliminary modeling, confirming findings from previous studies [

19]. Variables prone to leakage were systematically identified and excluded. Feature engineering was also applied to enhance predictive capacity, introducing interaction terms, such as the product of the debt-to-income ratio and annual income. As a result, the dataset was reduced to 98 features, significantly improving memory efficiency by reducing usage from 2.2 GB to 0.34 GB.

The dataset exhibited substantial class imbalance, with 89.04% of loans classified as "Fully Paid" and only 10.96% as "Default." This imbalance poses significant challenges for predictive modeling, as classifiers tend to become biased toward the majority class. To address this, the training set was balanced using random undersampling, reducing the size of the majority class to match the minority class. This ensures that the models learn equally from both classes, enhancing their ability to detect defaults. As a result, the training set contains 132,113 samples, while the test set retains the original class distribution to better reflect real-world conditions.

4.2. Hyperparameter Tuning for Machine Learning Models

Hyperparameters are advanced settings in machine learning algorithms that define the model’s structure and learning process but are not directly learned from the data. They differ from model parameters, which are optimized during training to fit the dataset. Classification algorithms are rarely parameter-free; for instance, XGBoost’s learning rate and maximum tree depth are critical settings that require careful tuning. Similarly, the number of hidden layers and neurons in a backpropagation neural network are typical hyperparameters. While model parameters determine how well a model fits the data, hyperparameters primarily control complexity and regularization, impacting the model’s accuracy, generalization, and computational efficiency. Hyperparameter tuning involves identifying the optimal combination of these settings to achieve the best performance. However, this process can be computationally intensive, especially for complex models with numerous hyperparameters [

17]. To address these challenges, various tuning methods have been developed, including grid search, random search, and more advanced techniques like Optuna.

In credit risk modeling, grid search has traditionally been the most widely used method for hyperparameter tuning [

31]. This algorithm performs an exhaustive search across all possible combinations of a predefined hyperparameter space. The performance of each combination is evaluated using cross-validation, which splits the training dataset into k-folds and computes an averaged evaluation metric, such as the area under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC). This Cartesian product-based approach ensures that the global optimum within the specified search space is found. However, it can be computationally expensive due to the exhaustive exploration of all parameter combinations.

In Equation (

1),

represents the set of candidate values for the

k-th hyperparameter,

K is the total number of hyperparameters, and

S is the total number of evaluations. Grid search ensures comprehensive coverage of the hyperparameter space. For example, if optimizing two hyperparameters—learning rate (

) and regularization strength (

)—with

and

, the grid search evaluates

configurations. While grid search is straightforward and easy to parallelize, it suffers from the curse of dimensionality, as the computational cost increases exponentially with the number of hyperparameters [

24].

In contrast, random search introduces stochasticity into the hyperparameter optimization process. Rather than evaluating every combination, it randomly samples a specified set of hyperparameters from the full search space, significantly reducing the computational cost. The likelihood of selecting the optimal configuration is expressed as:

where

is the hyperparameter space, and

represents a hyperparameter configuration sampled uniformly at random. Random search is often more efficient than grid search, particularly in high-dimensional spaces, because it avoids wasting computational resources on irrelevant dimensions. By focusing on random samples, this method can achieve better results with fewer trials. However, its performance depends on the number of trials

S and the distribution used for sampling. Studies have shown that random search can outperform grid search in high-dimensional hyperparameter spaces due to its broader exploration, but it may miss promising regions of the search space [

24].

Advanced techniques like Optuna are increasingly used to overcome the limitations of traditional hyperparameter tuning methods. Optuna [

25] utilizes state-of-the-art optimization strategies, including the tree-structured Parzen estimator (TPE) method for modeling objective functions and pruning unpromising trials, achieving superior results while reducing computational cost. This makes it particularly effective for high-dimensional search spaces. Unlike grid search and random search, Optuna constructs probabilistic models to capture the relationship between hyperparameters and the objective function, focusing on promising regions and discarding ineffective configurations based on previous trials. It proposes new hyperparameter values by sampling from learned distributions. Additionally, Optuna’s pruning mechanism halts poorly performing trials early, further minimizing computational overhead [

24].

The optimization objective is expressed as:

where

denotes the expected improvement or acquisition function, balancing the exploration of uncertain regions and the exploitation of promising ones. Bayesian optimization adaptively selects configurations to evaluate, enhancing computational efficiency. The model is updated iteratively with observed results, enabling the method to concentrate on regions of the search space most likely to yield optimal outcomes.

In this study, we systematically evaluate the performance of all three methods in optimizing the hyperparameters of our machine learning models.

4.2.1. Benchmark Models

The benchmark models used in this study are described as follows.

Logistic regression is a classical statistical method for binary classification tasks. It models the probability of an instance belonging to the positive class (e.g., default) as a function of a linear combination of input features. This approach is widely used due to its simplicity and balanced error distribution [

22].

The logistic function is expressed as:

where

are the model coefficients. By mapping predictions to a probability range between 0 and 1, logistic regression ensures interpretability and computational efficiency. However, it assumes a linear relationship between the predictors and the log-odds of the target variable, limiting its capacity to capture non-linear interactions in complex datasets.

XGBoost [

26] is an ensemble learning algorithm that enhances the predictive power of weak learners through gradient boosting, where decision trees are built iteratively. Each tree aims to correct the residual errors from the previous iteration, improving the model’s overall accuracy. The updated model at iteration

m is defined as:

where

represents the model from the previous iteration,

is the weak learner (e.g., decision tree) trained on the residuals, and

is the learning rate that controls the contribution of each new learner. This iterative approach allows XGBoost to effectively minimize the loss function, enhancing predictive performance and robustness against overfitting.

The overall XGBoost objective function is designed to minimize the following:

where

is the loss function that quantifies predictive accuracy by comparing the true labels

to the predictions

. Common choices for the loss function include mean squared error for regression tasks and logistic loss for classification problems.

The regularization term penalizes model complexity to enhance generalization and prevent overfitting. This term can include or regularization on model parameters, as well as tree-specific complexity measures, such as the number of leaves or leaf weights.

XGBoost optimizes the objective function by iteratively adding new weak learners to correct residual errors from previous iterations. The learning rate controls the contribution of each learner. This process continues until a predefined stopping criterion is met or optimal predictive performance is achieved, balancing model accuracy and complexity.

LightGBM enhances the gradient boosting framework by emphasizing computational efficiency and scalability. It utilizes gradient-based one-sided sampling, histogram-based algorithms, and exclusive feature bundling to accelerate training and reduce memory usage [

27]. The histogram-based approach optimizes the splitting process while mitigating overfitting, making LightGBM particularly effective for large-scale datasets.

Unlike the level-wise tree growth used in XGBoost, LightGBM employs a leaf-wise strategy that splits the leaf with the highest potential loss reduction. This approach efficiently allocates computational resources to the most challenging regions of the data, leading to faster convergence and improved predictive performance.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

Given the imbalanced nature of credit risk datasets, traditional metrics like accuracy are inadequate, as they often reflect the dominance of the majority class [

28,

29]. In skewed data distributions, correctly identifying minority instances (e.g., defaults) is crucial. However, it is equally important to maintain the model’s accuracy in classifying majority instances (non-defaults) without significantly compromising performance.

To achieve a balanced evaluation, multiple metrics are used, including AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and G-mean. These metrics are derived from the confusion matrix, which details the number of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, providing a comprehensive view of the model’s predictive performance.

Sensitivity measures the proportion of actual positive loans (non-defaults) correctly identified, while specificity (true negative rate) reflects the proportion of actual negative loans (defaults) accurately classified as negative. To provide a balanced evaluation, the geometric mean (G-mean) is calculated, ensuring the model performs well across both classes. G-mean is particularly useful for imbalanced datasets, as it penalizes models that excel in predicting the majority class while neglecting the minority class.

For performance evaluation, models are trained on the first 80% of the dataset and tested on the remaining 20%. This approach ensures that the model’s effectiveness is assessed on unseen data, maintaining the validity of the results.

where:

and

The benchmarking was performed on Google Colab, utilizing a single-core hyper-threaded Xeon processor at 2.3 GHz, 12 GB of RAM, and a Tesla K80 GPU with 2,496 CUDA cores and 12 GB of GDDR5 VRAM. The testing environment was configured with Python 3.6 and scikit-learn version 0.23.1.

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Optimization of Hyperparameters

This study examines the effectiveness of three automated hyperparameter tuning methods—grid search, random search, and Optuna—in optimizing model performance and minimizing manual intervention in machine learning. To simulate real-world credit scoring scenarios, the dataset is divided into training and test sets using a three-fold partitioning strategy. Models are trained on the training set and evaluated on the test set, with each fold serving as the test set once to ensure robust performance assessment. The number of iterations is set to 50 to balance accuracy and computational complexity. Due to the large dataset size and the high computational cost of grid search, hyperparameters are grouped into two categories: dynamic, which are adjusted during optimization, and fixed, which remain constant throughout the experiments.

Dynamic hyperparameters, including C, max_depth, and learning_rate, were systematically adjusted within the same predefined ranges across all three hyperparameter tuning methods to ensure comparability. In contrast, fixed hyperparameters, such as maximum iterations and minimum child weight, were set to their default values to maintain consistency across experiments (Appendix A

Table A1).

Table 2 presents the hyperparameter configurations selected by the three tuning methods before model training.

The results indicate that the three methods do not always converge on the same optimal hyperparameters. For logistic regression, both grid search and random search, which rely on fixed sampling strategies, select identical hyperparameters, with the inverse of regularization strength (C) set at 0.01.

In contrast, Optuna selects a higher value for C (0.1758), likely due to its ability to explore a continuous range with finer granularity.

Similarly, for XGBoost, the selected hyperparameters share some similarities in fixed settings, such as max_depth (8–9) and n_estimators (188–200). However, differences emerge in learning_rate, reg_alpha, and reg_lambda. Grid search tends to select larger regularization parameters (reg_alpha=1, reg_lambda=10) with a higher learning rate (0.1), while random search explores smaller values. Optuna strikes a balance, selecting intermediate values for learning_rate and reg_lambda, with greater flexibility in the subsample (0.709).

For LightGBM, Optuna demonstrates similar strengths, exploring finer granularity across all parameters. It selects intermediate values for subsample (0.54) and reg_alpha (0.018), compared to the broader choices of grid search (subsample=0.5) and random search (subsample=0.778).

5.2. Performance Analysis

The performance of the three hyperparameter tuning methods is evaluated on the test set across three models: LightGBM, XGBoost, and logistic regression.

Table 3 shows that Optuna outperforms grid search in terms of computational efficiency while delivering comparable model performance. Optuna achieves hyperparameter optimization in 986.12 seconds for XGBoost and 621.89 seconds for LightGBM, resulting in accelerations of 10.7 times for XGBoost and 40.5 times for LightGBM compared to grid search, which took 10,528.95 and 25,170.92 seconds, respectively, exhibiting the slowest performance. Random search ranks first in terms of speed, completing optimization in 746.77 seconds for XGBoost and 508.53 seconds for LightGBM. Its random exploration of the hyperparameter space enables efficient identification of optimal configurations.

However, the execution time for logistic regression was shortest with grid search, at 389.57 seconds, compared to 1,346.56 seconds for random search and 2,319.85 seconds for Optuna. Logistic regression has fewer hyperparameters and a simpler model structure, allowing grid search to optimize it quickly. In contrast, random search and Optuna, which rely on probabilistic or random sampling, require more iterations to converge to an optimal solution.

The results highlight a trade-off between predictive performance and computational efficiency when selecting a hyperparameter tuning approach. The findings reveal consistent trends across the AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and G-mean metrics, with LightGBM generally outperforming the other models.

LightGBM achieves the highest AUC values across all methods, with grid search slightly leading at 0.9422, followed closely by Optuna (0.9418) and random search (0.9415). Sensitivity and specificity were closely aligned across the tuning methods, with grid search yielding marginally better G-mean (0.8629) than Optuna (0.8627) and random search (0.8612).

XGBoost performance is similarly stable across methods, with grid search achieving a slightly better G-mean (0.8616) compared to Optuna (0.8614) and random search (0.8606). Grid search also demonstrates high sensitivity (0.8162).

For logistic regression, AUC performance remains consistent across all methods (approximately 0.915).

However, Optuna’s configurations result in slightly lower recall (0.7143) but higher specificity (0.955) compared to grid search and random search, which yield identical results. The difference in G-mean between the methods remains minimal (grid search: 0.8284, Optuna: 0.8260).

These findings suggest that hyperparameter optimization strategies primarily impact computational efficiency rather than addressing class imbalance. Nonetheless, maintaining strong discriminative power is crucial for credit risk assessment, as it ensures both risky and creditworthy borrowers are correctly classified, reducing credit losses from defaults while maximizing loan approvals through accurate classification.

The marginal differences in AUC, sensitivity, and specificity across the tuning methods indicate a convergence toward near-optimal solutions. However, the high computational cost of grid search becomes a significant concern in real-world P2P applications. Its exhaustive search of the hyperparameter space results in exponential computational complexity. In contrast, Optuna and random search offer a clear advantage, achieving similar predictive performance while significantly reducing computational overhead. By leveraging information from previous trials, Optuna dynamically refines its exploration of the hyperparameter space, often identifying well-balanced configurations. This advantage is particularly evident in LightGBM, where Optuna achieved comparable AUC and G-mean values to grid search, leading to substantial savings in computational resources without compromising model performance.

While random search offers greater time efficiency, it relies heavily on randomness, which can lead to inconsistent performance. Its dependence on chance for selecting optimal parameters means that the quality of identified hyperparameters may vary significantly across different runs. Despite this variability, random search remains efficient because it avoids the additional steps required in Bayesian optimization, such as fitting surrogate models, estimating acquisition functions, and iteratively updating the search distribution.

5.3. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Results

The performance results from this study were benchmarked against those presented in Ko et al. [

14], Song et al. [

20], and Xia et al. [

22], each of which employed the same dataset but utilized different methodologies and modeling frameworks. Their results are presented in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6.

For AUC, a critical metric for model evaluation in credit scoring, LightGBM and XGBoost consistently outperformed logistic regression and decision tree models from previous studies. Optuna-LightGBM achieved an AUC of 0.942, surpassing the values reported by Ko et al. [

14], where LightGBM and ANN showed AUCs of 0.749 and 0.736, respectively. Across all studies, our models demonstrated significant improvements in sensitivity. For example, Optuna-LightGBM achieved a recall of 0.818 with a G-mean of 0.863, outperforming the 0.702 recall of random forest in Ko et al. [

14] and the 0.637 recall of XGBoost-TPE in Xia et al. [

22]. Similarly, Optuna-XGBoost achieved a recall of 0.812, substantially higher than the 0.662 sensitivity of random forest reported in Song et al. [

20]. These results suggest more balanced classification performance and improved credit management. Although differences in experimental setups and datasets may contribute to variations between studies, the findings indicate that systematically tuning hyperparameters enhances the predictive robustness of ensemble methods for credit scoring.

5.4. Feature Importance Analysis

Interpretability remains a significant challenge in machine learning, particularly in credit scoring. Models with improved transparency, such as those incorporating explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) techniques like SHAP or F-scores, enable managers to understand the decision-making process. This facilitates targeted improvements while addressing concerns related to fairness, accountability, and regulatory compliance [

6]. In tree-based models, feature importance is determined by measuring how much each feature contributes to reducing the model’s prediction error. Common metrics include feature frequency in splits (weight), total impurity reduction (gain), and average gain across splits (cover). These measures quantify a feature’s overall impact on the model’s predictive performance, allowing the ranking of attributes by their relative importance. The top 10 features, ranked in descending order, are presented in

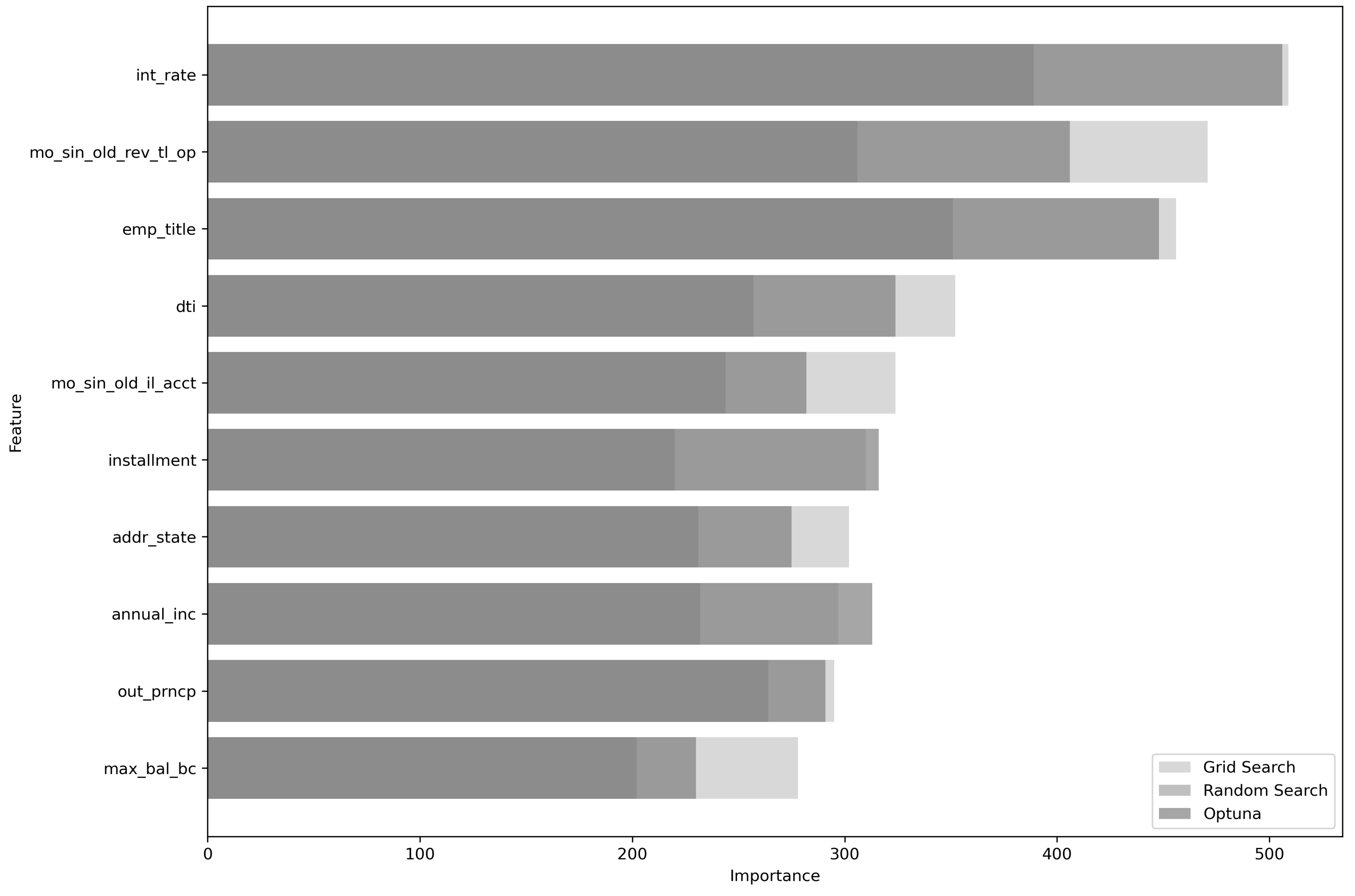

Figure 2, using LightGBM optimized by grid search, random search, and Optuna.

In

Figure 2, a higher importance score indicates that the corresponding feature is more influential in the model’s decision-making. The analysis highlights distinct patterns across the different hyperparameter tuning methods. Notably, temporal credit indicators, such as months since the oldest revolving trade opening (mo_sin_old_rev_tl_op) and months since the oldest installment account (mo_sin_old_il_acct), consistently emerge as primary predictors across all tuning methods. However, differences arise in the rankings of Optuna and random search, which emphasize features like interest rate sensitivity, job status, and the number of installments, reflecting a focus on the cost of borrowing and financial stability. In contrast, grid search tends to prioritize credit depth and borrower maturity, underscoring its orientation towards longer-term credit history.

6. Conclusions

This research benchmarks hyperparameter tuning methods in terms of both performance and efficiency, while also examining how tuning influences feature importance and model interpretability. Utilizing the Lending Club dataset and applying rigorous data preprocessing and feature engineering techniques, the study evaluates the performance of grid search, random search, and Optuna across three widely used machine learning models: XGBoost, LightGBM, and logistic regression.

The results can be summarized as follows: LightGBM consistently outperformed most other techniques across hyperparameter tuning methods, demonstrating robust predictive performance and high sensitivity to bad loans. This makes LightGBM particularly advantageous for financial institutions looking to mitigate risks by accurately identifying potential defaulters. These findings are consistent with those of Lessmann et al. [

10], further supporting the increasing preference for ensemble methods. Bayesian optimization, as implemented by Optuna, proves to be a highly effective and efficient strategy for hyperparameter tuning. This approach strikes a balance between exploration and exploitation, allowing it to leverage prior knowledge and efficiently converge on high-performing hyperparameter configurations while maintaining strong computational efficiency. While grid search achieves comparable performance to Optuna, it is significantly less efficient. Lastly, logistic regression remains relevant in credit scoring due to its simplicity and interpretability, but its performance is surpassed by ensemble models, likely due to their enhanced robustness in high-dimensional datasets resulting from a larger number of parameters and hyperparameters.

To answer the research questions, this study empirically explored the trade-off between computational efficiency and predictive performance, as well as the impact of hyperparameter tuning on model interpretability. Firstly, random search provided the best balance between G-Mean and execution cost, closely followed by Optuna, which incurred slightly higher computational costs. However, the stochastic nature of random search introduces variability in results across iterations, as it randomly selects hyperparameter values from a predefined search space, with each run exploring a different subset of possible configurations. In contrast, Optuna’s structured Bayesian approach offers greater stability and efficiency. By optimizing both accuracy and cost, Optuna enables faster and more accurate credit risk assessment in P2P lending.

The variation in feature importance rankings across hyperparameter tuning methods has a notable impact on LightGBM’s interpretability. The results indicate that the importance of features shifts depending on the internal feature weighting mechanisms of different tuning strategies. This sensitivity carries significant implications for model transparency and regulatory compliance, as varying optimization approaches can result in divergent risk factor rankings, even when predictive performance remains similar. In practice, these differences influence loan approval decisions, borrower risk segmentation, and regulatory transparency. Consequently, the choice of tuning strategy becomes a critical factor in ensuring reliable credit scoring for P2P lending platforms.

Building on these insights, future research could explore the integration of meta-learning models, such as stacking, which may enhance the robustness and accuracy of credit scoring classifiers. Additionally, investigating alternative loss functions that better align with real-world cost distributions in credit risk assessment could further improve model performance and practical relevance. Expanding the study to include additional datasets from diverse geographic regions and lending platforms would also provide valuable insights into the generalizability of the observed trends.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.I.S. and A.R.H.; methodology, L.I.S. and A.R.H.; software, A.R.H.; validation, L.I.S., A.R.H. and B.B.; formal analysis, L.I.S., A.R.H. and B.B.; investigation, L.I.S., A.R.H. and B.B.; resources, L.I.S., A.R.H. and B.B.; data curation, L.I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.I.S., J.M.O. and P.R.; writing—review and editing, L.I.S., J.M.O. and P.R.;visualization, L.I.S. and A.R.H.; supervision, B.B.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

A publicly available dataset was used in this study. The data can be found here:

https://www.lendingclub.com/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our sincere gratitude to the research laboratory “Applied Studies in Business and Management Sciences” at the Higher School of Commerce, Algeria, for their support and collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this paper:

| ANN |

Artificial Neural Networks |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| AUC-ROC |

Area Under the ROC Curve |

| C |

Inverse of regularization strength |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| DT |

Decision Trees |

| DTI |

Debt-to-Income ratio |

| EI |

Expected Improvement |

| FICO |

Fair Isaac Corporation |

| GB |

Gigabytes |

| GBDT |

Gradient Boosted Decision Trees |

| G-mean |

Geometric Mean |

| GS |

Grid Search |

| LC |

Lending Club |

| LDA |

Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| LightGBM |

Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

| LIME |

Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations |

| LR |

Logistic Regression |

| P2P |

Peer-to-Peer |

| PDF |

Probability Density Function |

| RS |

Random Search |

| SHAP |

Shapley Additive Explanations |

| SMOTE |

Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machines |

| TPE |

Tree-structured Parzen Estimator |

| XAI |

Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| XGBoost |

Extreme Gradient Boosting |

Appendix A

The dynamic and fixed hyperparameters are summarized in

Table A1.

Table A1.

Hyperparameters for different models.

Table A1.

Hyperparameters for different models.

| Model |

Dynamic Hyperparameters |

Fixed Hyperparameters |

| Logistic Regression |

c, solver, penalty |

max_iter = 1000, random_state = 42 |

| XGBoost |

n_estimators, max_depth, learning_rate, subsample, reg_alpha, reg_lambda |

use_label_encoder = false, eval_metric = ’logloss’, random_state = 42, colsample_bytree = 1, min_child_weight = 1 |

| LightGBM |

n_estimators, max_depth, learning_rate, subsample, reg_alpha, reg_lambda, num_leaves |

verbosity = -1, boosting_type = ’gbdt’, random_state = 42, min_child_samples = 20, n_jobs = -1 |

References

- B.-J. Ma, Z.-L. Zhou, and F.-Y. Hu, Pricing mechanisms in the online peer-to-peer lending market, Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, vol. 26, pp. 119–130, 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Lenz, Peer-to-peer lending: Opportunities and risks, European Journal of Risk Regulation, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 688–700, 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Serrano-Cinca, B. Gutiérrez-Nieto, and L. López-Palacios, Determinants of default in P2P lending, PloS one, vol. 10, no. 10, p. e0139427, 2015. [CrossRef]

- X. Lei, Discussion of the Risks and Risk Control of P2P in China, Modern Economy, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 399–403, 2016. [CrossRef]

- V. Moscato, A. Picariello, and G. Sperlì, A benchmark of machine learning approaches for credit score prediction, Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 165, p. 113986, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Noriega, L. A. Rivera, and J. A. Herrera, Machine Learning for Credit Risk Prediction: A Systematic Literature Review, Data, vol. 8, no. 11, p. 169, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. M. Alam, K. Shaukat, I. A. Hameed, S. Luo, M. U. Sarwar, S. Shabbir, J. Li, and M. Khushi, An investigation of credit card default prediction in the imbalanced datasets, IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 201173–201198, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Si, H. Niu, and W. Wang, Credit Risk Assessment by a Comparison Application of Two Boosting Algorithms, in Fuzzy Systems and Data Mining VIII, IOS Press, pp. 34–40, 2022.

- F. Doshi-Velez and B. Kim, Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning, arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.08608, 2017.

- S. Lessmann, B. Baesens, H.-V. Seow, and L. C. Thomas, Benchmarking state-of-the-art classification algorithms for credit scoring: An update of research, European Journal of Operational Research, vol. 247, no. 1, pp. 124–136, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Malekipirbazari and V. Aksakalli, Risk assessment in social lending via random forests, Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 42, no. 10, pp. 4621–4631, 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. Emekter, Y. Tu, B. Jirasakuldech, and M. Lu, Evaluating credit risk and loan performance in online Peer-to-Peer (P2P) lending, Applied Economics, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 54–70, 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. Teply and M. Polena, Best classification algorithms in peer-to-peer lending, The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, vol. 51, p. 100904, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P.-C. Ko, P.-C. Lin, H.-T. Do, and Y.-F. Huang, P2P lending default prediction based on AI and statistical models, Entropy, vol. 24, no. 6, p. 801, 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Ma, J. Sha, D. Wang, Y. Yu, Q. Yang, and X. Niu, Study on a prediction of P2P network loan default based on the machine learning LightGBM and XGboost algorithms according to different high dimensional data cleaning, Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, vol. 31, pp. 24–39, 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Rout, D. Mishra, and M. K. Mallick, Handling imbalanced data: a survey, in International Proceedings on Advances in Soft Computing, Intelligent Systems and Applications: ASISA 2016, pp. 431–443, 2018.

- H. Guo, Y. Li, J. Shang, M. Gu, Y. Huang, and B. Gong, Learning from class-imbalanced data: Review of methods and applications, Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 73, pp. 220–239, 2017.

- C. V. KrishnaVeni and T. Sobha Rani, On the classification of imbalanced datasets, IJCST, vol. 2, no. SP1, pp. 145–148, 2011.

- A. Namvar, M. Siami, F. Rabhi, and M. Naderpour, Credit risk prediction in an imbalanced social lending environment, International Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 925–935, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Song, Y. Wang, X. Ye, D. Wang, Y. Yin, and Y. Wang, Multi-view ensemble learning based on distance-to-model and adaptive clustering for imbalanced credit risk assessment in P2P lending, Information Sciences, vol. 525, pp. 182–204, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. F. F. Huang and P. C. Boutros, The parameter sensitivity of random forests, BMC bioinformatics, vol. 17, pp. 1–13, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xia, C. Liu, Y. Li, and N. Liu, A boosted decision tree approach using Bayesian hyper-parameter optimization for credit scoring, Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 78, pp. 225–241, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Chang, S. D. Kim, and G. Kondo, Predicting default risk of lending club loans, Machine Learning, pp. 1–5, 201.

- J. Bergstra and Y. Bengio, Random search for hyper-parameter optimization, Journal of Machine Learning Research, vol. 13, no. 2, 2012.

- T. Akiba, S. Sano, T. Yanase, T. Ohta, and M. Koyama, Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework, in Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, pp. 2623–2631, 2019.

- J. H. Friedman, Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine, Annals of Statistics, pp. 1189–1232, 2001.

- Y. Song, Y. Li, Y. Zou, R. Wang, Y. Liang, S. Xu, Y. He, X. Yu, and W. Wu, Synergizing multiple machine learning techniques and remote sensing for advanced landslide susceptibility assessment: a case study in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area, Environmental Earth Sciences, vol. 83, no. 8, p. 227, 2024.

- M. F. Amasyali, Improved space forest: A meta ensemble method, IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 816–826, 2018.

- J. Abellán and J. G. Castellano, A comparative study on base classifiers in ensemble methods for credit scoring, Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 73, pp. 1–10, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H.-P. Nguyen, J. Liu, and E. Zio, A long-term prediction approach based on long short-term memory neural networks with automatic parameter optimization by Tree-structured Parzen Estimator and applied to time-series data of NPP steam generators, Applied Soft Computing, vol. 89, p. 106116, 2020.

- G. M. Jakka, A. Panigrahi, A. Pati, M. N. Das, and J. Tripathy, A novel credit scoring system in financial institutions using artificial intelligence technology, Journal of Autonomous Intelligence, vol. 6, no. 2, 2023. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

https://www.lendingclub.com/ |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).