Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

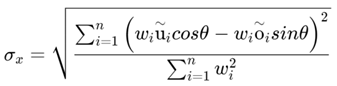

2. Overview of the Study Area and Data Sources

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Data Sources and Processing

2.3. Study Area Framework

3. Research Methods

3.1. Method for Selecting Ecological Source Areas

3.2. Resistance Surface Construction

3.3. Ecological Network Construction

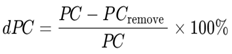

3.3.1. Ecological Corridor Identification and Classification Based on the MCR Model

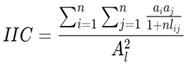

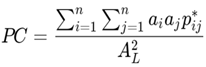

3.3.2. Ecological Corridor Network Structure Index Evaluation

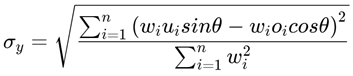

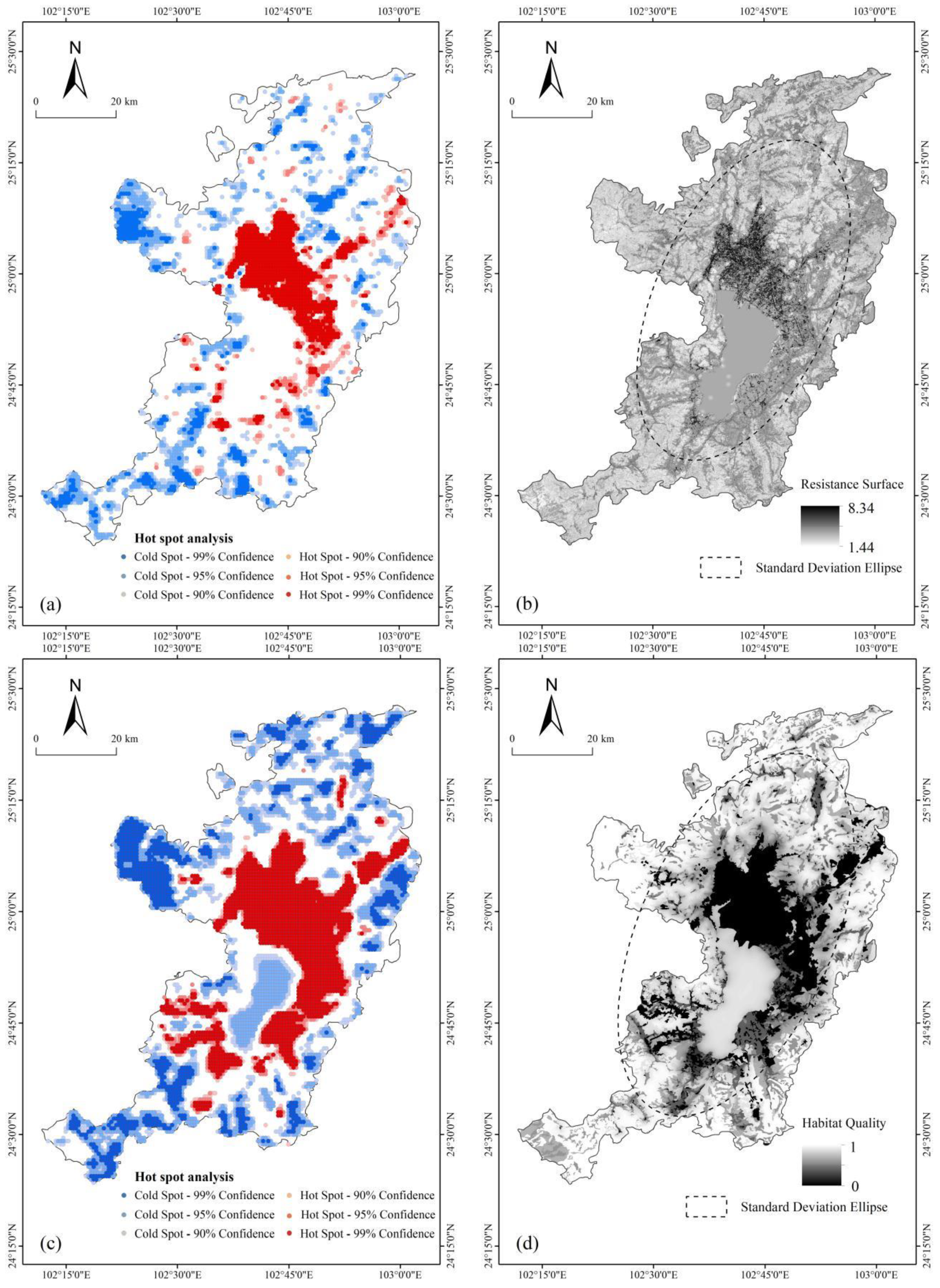

3.4. Spatial Analysis Based on Hotspot Analysis Coupled with the Standard Deviational Ellipse Model

4. Results

4.1. Analysis and Selection of Ecological Source Areas

4.2. Ecological Network Construction

4.2.1. Ecological Resistance Surface

4.2.2. Ecological Corridor Extraction and Classification

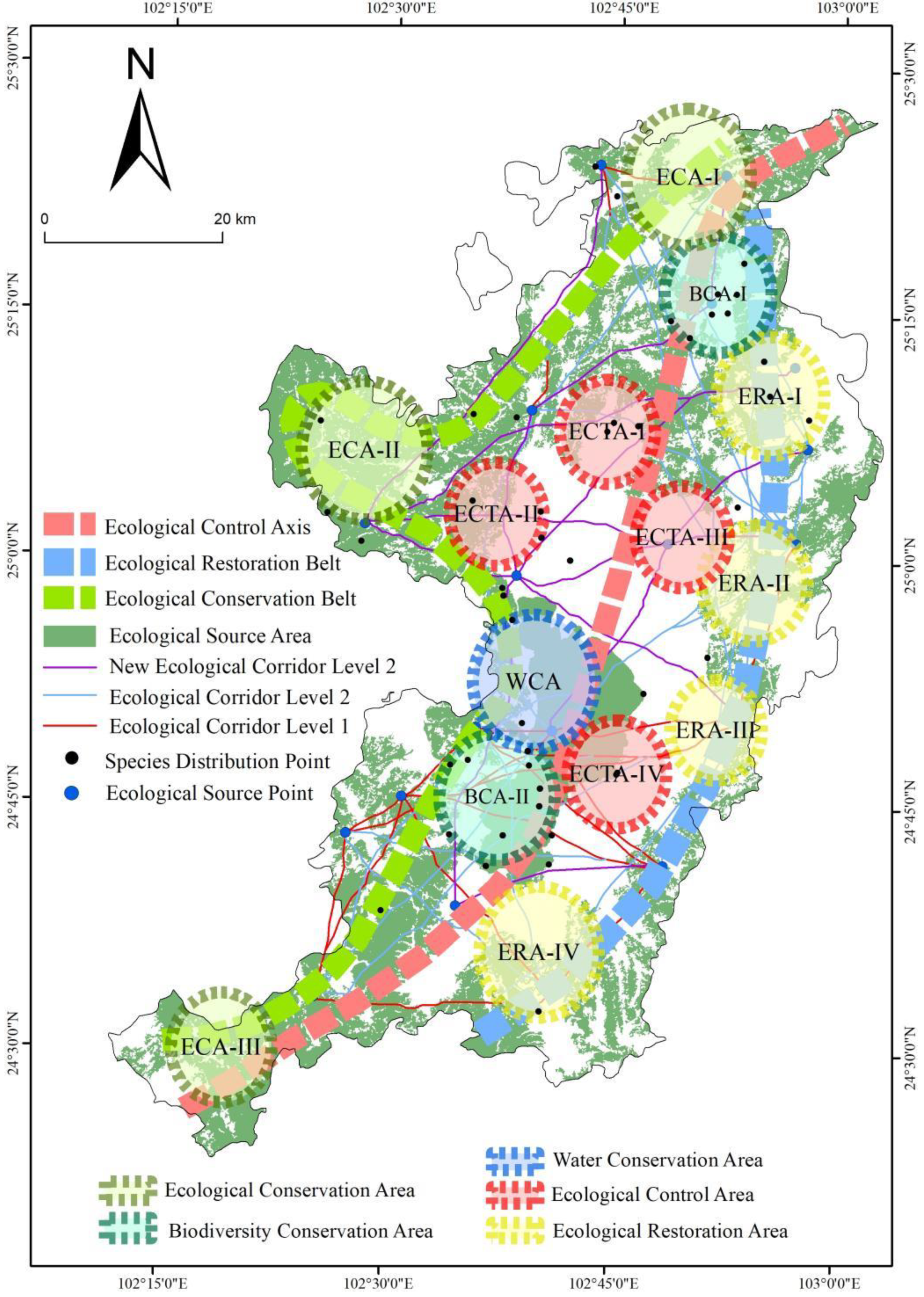

4.3. Ecological Network Optimization

4.3.1. New Ecological Patch Analysis

4.3.2. New Ecological Corridor Analysis

4.3.3. New Ecological Node, Stepping Stone, and Fracture Point Analysis

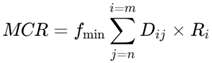

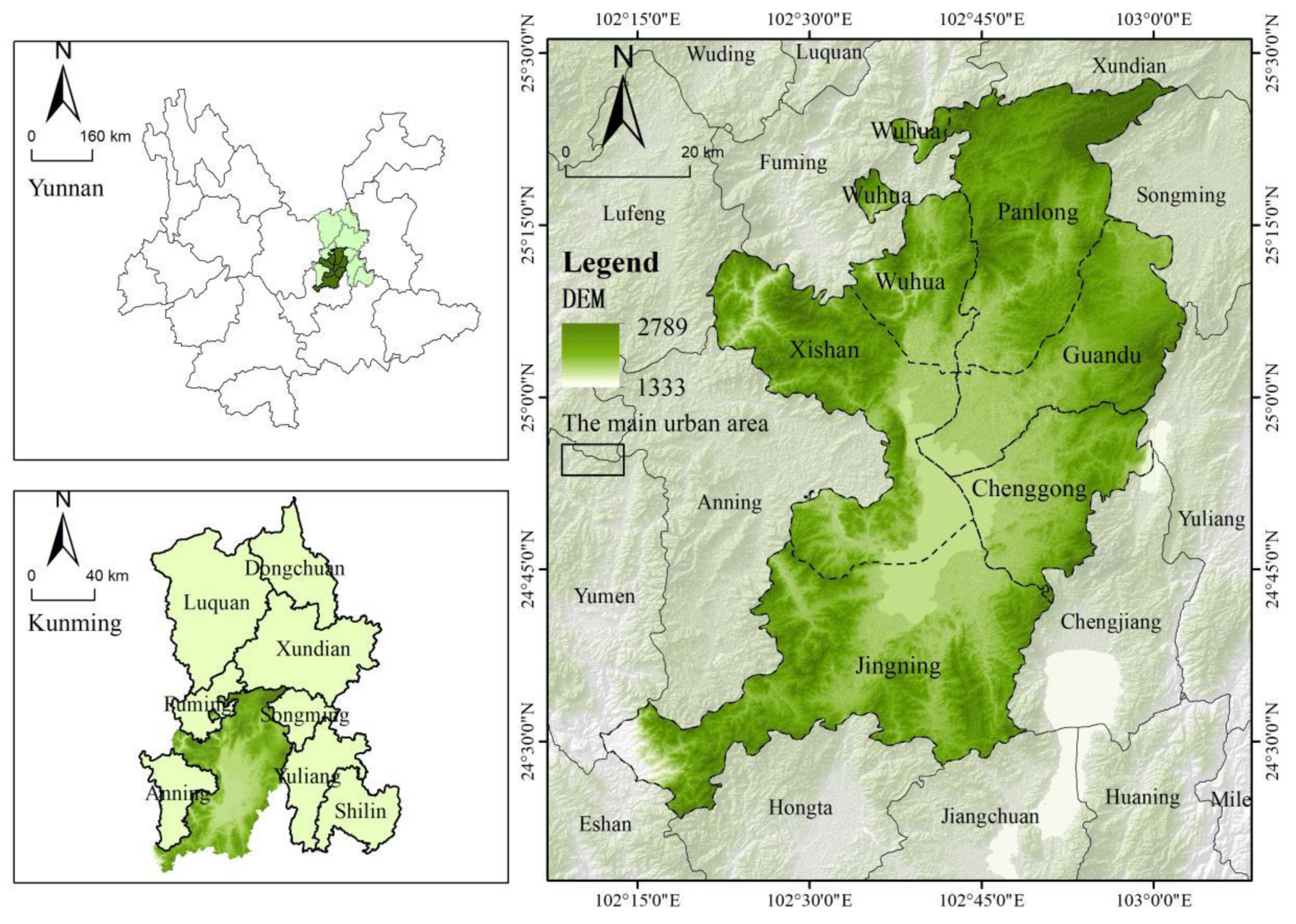

4.3.4. Based on the network structure index, quantitative evaluation and analysis of the ecological network

4.4. Spatial analysis through hotspot analysis coupled with the Standard Deviational Ellipse model

4.3. Construction of Ecological Safety Pattern

5. Discussion

References

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, W.; Xiao, R. Effects of rapid urbanization on ecological functional vulnerability of the land system in Wuhan, China: A flow and stock perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gong, J.; Guldmann, J.-M.; Yang, J. Assessment of Urban Ecological Quality and Spatial Heterogeneity Based on Remote Sensing: A Case Study of the Rapid Urbanization of Wuhan City. Remote. Sens. 2021, 13, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Qi, W. Construction of Cultivated Land Ecological Network Based on Supply and Demand of Ecosystem Services and MCR Model: A Case Study of Shandong Province, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Wang, L.; Guo, Y.; Fu, M.; Huang, N.; Duan, W.; Luo, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Song, W. Spatio-temporal variation and coupling coordination relationship between urbanisation and habitat quality in the Grand Canal, China. Land Use Policy 2022, 117, 106119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Yu, X.; Yu, H.; Ma, Z.; Luo, Y.; Liu, T.; Rong, Z.; Xu, J.; Chen, D.; Li, P.; et al. Suitable habitat evaluation and ecological security pattern optimization for the ecological restoration of Giant Panda habitat based on nonstationary factors and MCR model. Ecol. Model. 2024, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Liu, C.; Ma, L.; Zhang, X.; Xie, B. Ecological Land Suitability for Arid Region at River Basin Scale: Framework and Application Based on Minmum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) Model. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-X.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.-N.; Guo, W.-W.; Yang, A.-L.; Yang, X.; Li, E.-Z.; Wang, Z.-J. Identification and Trend Analysis of Ecological Security Pattern in Mudanjiang City Based on MSPA-MCR-PLUS Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, T. Construction and Optimization Strategy of County Ecological Infrastructure Network Based on MCR and Gravity Model—A Case Study of Langzhong County in Sichuan Province. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; You, H.; Han, X. Construction and Optimization of an Ecological Network in the Yellow River Source Region Based on MSPA and MCR Modelling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2023, 20, 3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Ju, H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, G. The Construction of Ecological Security Patterns in Coastal Areas Based on Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment—A Case Study of Jiaodong Peninsula, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 12249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiao, L.; Tian, C.; Zhu, B.; Chevallier, J. Impacts of the ecological footprint on sustainable development: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Sha, J.; Eladawy, A.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Kurbanov, E.; Lin, Z.; Wu, L.; Han, R.; Su, Y.-C. Evaluation of ecological security and ecological maintenance based on pressure-state-response (PSR) model, case study: Fuzhou city, China. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assessment: Int. J. 2022, 28, 734–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zang, P.; Guo, H.; Yang, G. Wetlands ecological security assessment in lower reaches of Taoerhe river connected with Nenjiang river using modified PSR model. HydroResearch 2023, 6, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhu, C.; Fan, X.; Li, M.; Xu, N.; Yuan, Y.; Guan, Y.; Lyu, C.; Bai, Z. Analysis of ecological network evolution in an ecological restoration area with the MSPA-MCR model: A case study from Ningwu County, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Du, Z.; Tao, P.; Liang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Construction of Green Space Ecological Network in Xiongan New Area Based on the MSPA–InVEST–MCR Model. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhu, H.; Chen, J.; Jiao, H.; Li, P.; Xiong, L. Construction and Optimization of Ecological Security Pattern in the Loess Plateau of China Based on the Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) Model. Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 5906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Halike, A.; Yao, K.; Chen, L.; Balati, M. Construction and optimization of ecological security pattern in Ebinur Lake Basin based on MSPA-MCR models. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 138, 108857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, W.; Li, Q.; Wang, J. Ecological Security Pattern Construction in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region Based on Hotspots of Multiple Ecosystem Services. Sustainability 2022, 14, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Fan, F.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J.; Chen, J. Construction of Ecological Security Patterns in Nature Reserves Based on Ecosystem Services and Circuit Theory: A Case Study in Wenchuan, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 16, 3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Wu, X.; Wen, H.; Ma, X.; Zhang, F.; Ji, Q.; Zhang, J. Ecological Security Pattern based on XGBoost-MCR model: A case study of the Three Gorges Reservoir Region. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Han, Z.; Meng, J.; Zhu, L. Circuit theory-based ecological security pattern could promote ecological protection in the Heihe River Basin of China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 27340–27356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Fu, B.; Ma, R.; Yang, Y.; Lü, Y.; Wu, X. Identifying ecological security patterns based on the supply, demand and sensitivity of ecosystem service: A case study in the Yellow River Basin, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 315, 115158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, W.; Pickett, S.T.; Yu, W.; Li, W. A multiscale analysis of urbanization effects on ecosystem services supply in an urban megaregion. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 662, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, S. Construction of landscape ecological network based on landscape ecological risk assessment in a large-scale opencast coal mine area. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Xu, D.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, S. Enhancing the MSPA Method to Incorporate Ecological Sensitivity: Construction of Ecological Security Patterns in Harbin City. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. Evaluation of urban ecological security model based on GIS sensing and MCR model. Meas. Sensors 2024, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Hu, J.; Li, B. How to restore ecological impacts from wind energy? An assessment of Zhongying Wind Farm through MSPA-MCR model and circuit theory. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhu, L.; Fu, H. Construction of wetland ecological network based on MSPA-Conefor-MCR: A case study of Haikou City. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Du, Z.; Tao, P.; Liang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Construction of Green Space Ecological Network in Xiongan New Area Based on the MSPA–InVEST–MCR Model. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.-Z.; Dai, J.-P.; Li, S.-H.; Zhang, J.-Z.; Peng, J.-S. Construction of ecological network in Qujing city based on MSPA and MCR models. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-X.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.-N.; Guo, W.-W.; Yang, A.-L.; Yang, X.; Li, E.-Z.; Wang, Z.-J. Identification and Trend Analysis of Ecological Security Pattern in Mudanjiang City Based on MSPA-MCR-PLUS Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, J. Construction and optimization of regional ecological security patterns based on MSPA-MCR-GA Model: A case study of Dongting Lake Basin in China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 165, 112169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Ju, H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, G. The Construction of Ecological Security Patterns in Coastal Areas Based on Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment—A Case Study of Jiaodong Peninsula, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 12249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Lv, C. Construction and optimization of green space ecological networks in urban fringe areas: A case study with the urban fringe area of Tongzhou district in Beijing. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Bao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wei, W. Multi-temporal evaluation and optimization of ecological network in multi-mountainous city. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, H.; Shan, L.; Xiao, F. Constructing and optimizing urban ecological network in the context of rapid urbanization for improving landscape connectivity. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 132, 108319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, T.; Han, F. Landscape Ecological Risk and Ecological Security Pattern Construction in World Natural Heritage Sites: A Case Study of Bayinbuluke, Xinjiang, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information 2022, 11, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIU, Y.Y.; Meng, G.A.O. Mesh-connected rings topology for network-on-chip. The Journal of China Universities of Posts and Telecommunications 2013, 20, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminzadeh, B.; Khansefid, M. A case study of urban ecological networks and a sustainable city: Tehran’s metropolitan area. Urban Ecosyst. 2010, 13, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Song, Q.; Zhao, J.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, H. Identification of Key Areas and Early-Warning Points for Ecological Protection and Restoration in the Yellow River Source Area Based on Ecological Security Pattern. Land 2023, 12, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Chen, K. Analysis of Blue Infrastructure Network Pattern in the Hanjiang Ecological Economic Zone in China. Water 2022, 14, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Jia, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, T.; Gao, Q. Application of MSPA-MCR models to construct ecological security pattern in the basin: A case study of Dawen River basin. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ao, Y.; Han, L.; Kang, S.; Sun, Y. Effects of human activity intensity on habitat quality based on nighttime light remote sensing: A case study of Northern Shaanxi, China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 851, 158037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.; Zhou, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, M.; Zhang, P. Linking Ecosystem Service and MSPA to Construct Landscape Ecological Network of the Huaiyang Section of the Grand Canal. Land 2021, 10, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, P.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Rong, T.; Liu, Z.; Yang, D.; Lou, Y. Construction of GI Network Based on MSPA and PLUS Model in the Main Urban Area of Zhengzhou: A Case Study. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 878656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.-Y.; Yue, W.-Z.; Feng, S.-R.; Cai, J.-J. Analysis of spatial heterogeneity of ecological security based on MCR model and ecological pattern optimization in the Yuexi county of the Dabie Mountain Area. J. Nat. Resour. 2019, 34, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, D.; Zhang, J. Combining MSPA-MCR Model to Evaluate the Ecological Network in Wuhan, China. Land 2022, 11, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Reference year | Spatial resolution | Source |

| IBI | 2020 | 30m | Google Earth Engine (https://code.earthengine.google.com/) |

| FVC | 2020 | 30m | Google Earth Engine https://code.earthengine.google.com/ |

| Land cover | 2020 | 30m | Resource and Environment Data Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences (http://www.resdc.cn/) |

| DEM | 2020 | 30m | Geospatial Data Cloud (http://www.gscloud.cn/) |

| Slope | 2020 | 30m | Calculated using DEM data in ArcMap software |

| Species distribution | 2020 | 30m | Resource and Environment Data Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences (http://www.resdc.cn/) |

| roads | 2020 | 30m | Open Street Map (http://www.openstreetmap.org) |

| rivers | 2020 | 30m |

| Resistance factor |

Classifcation criteia |

Resistance value |

Weight | Resistance factor |

Classifcation criteia |

Resistance value |

Weight |

| Land use type | Forest, Grassland | 1 | 0.3459 | Distance to Species distribution/(m) | 0-100 | 1 | 0.0892 |

| Arable land | 3 | 100-300 | 3 | ||||

| Water | 5 | 300-500 | 5 | ||||

| Bare land | 7 | 500-700 | 7 | ||||

| Impervious surface | 9 | >700 | 9 | ||||

| Slope/(°) | 0-6 | 1 | 0.1209 | Distance to roads/(m) | 0-50 | 9 | 0.0588 |

| 6-13 | 3 | 50-100 | 7 | ||||

| 13-20 | 5 | 100-200 | 5 | ||||

| 20-30 | 7 | 200-300 | 3 | ||||

| >30 | 9 | >300 | 1 | ||||

| Elevation/m | <1700 | 1 | 0.1103 | Distance to railways/(m) | 0-50 | 9 | 0.0588 |

| 1700-1900 | 3 | 50-100 | 7 | ||||

| 1900-2100 | 5 | 100-200 | 5 | ||||

| 2100-2300 | 7 | 200-300 | 3 | ||||

| >2300 | 9 | >300 | 1 | ||||

| IBI | <0.2 | 1 | 0.1101 | FVC | <0.2 | 9 | 0.106 |

| 0.2-0.4 | 3 | 0.2-0.4 | 7 | ||||

| 0.4-0.6 | 5 | 0.4-0.6 | 5 | ||||

| 0.6-0.8 | 7 | 0.6-0.8 | 3 | ||||

| >0.8 | 9 | >0.8 | 1 |

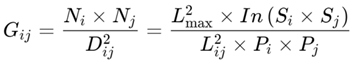

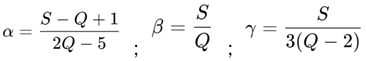

| Ecological Network | Number of Ecological Patches (Q) | Number of Potential Ecological Corridors (S) | Network Closure Index (α) | Network Connectivity Index (β) | Network Connectivity Rate Index (γ) |

| Before Optimization | 13 | 178 | 8.524 | 13.692 | 5.394 |

| After Optimization | 19 | 324 | 9.818 | 17.052 | 6.353 |

| Percentage Change | +46.15% | +82.02% | +15.16% | +24.56% | +17.79% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).