Submitted:

22 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

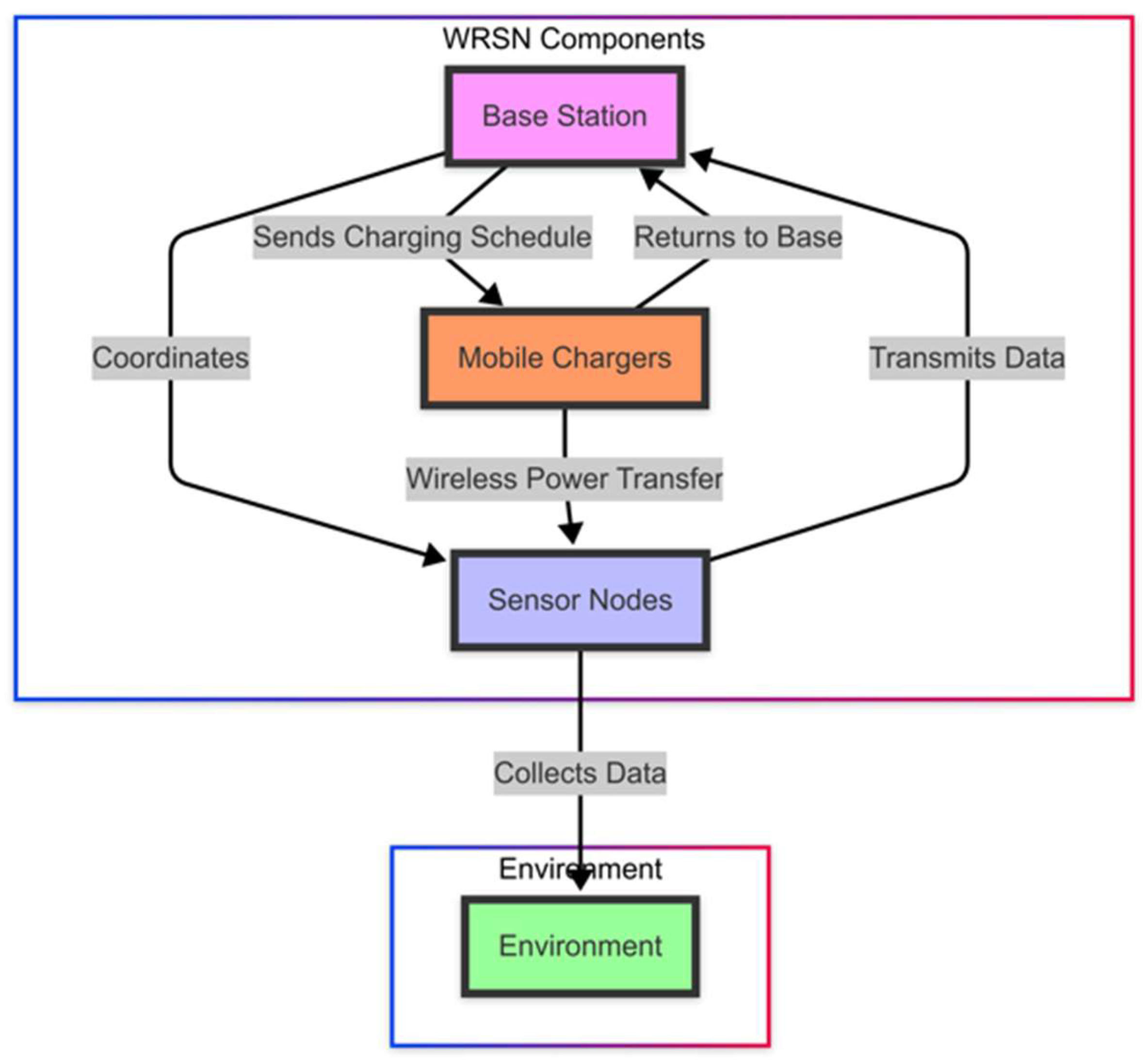

2. Overview and Related Works of WRSN

2.1. Overview of WRSNs

2.2. Related Survey Works

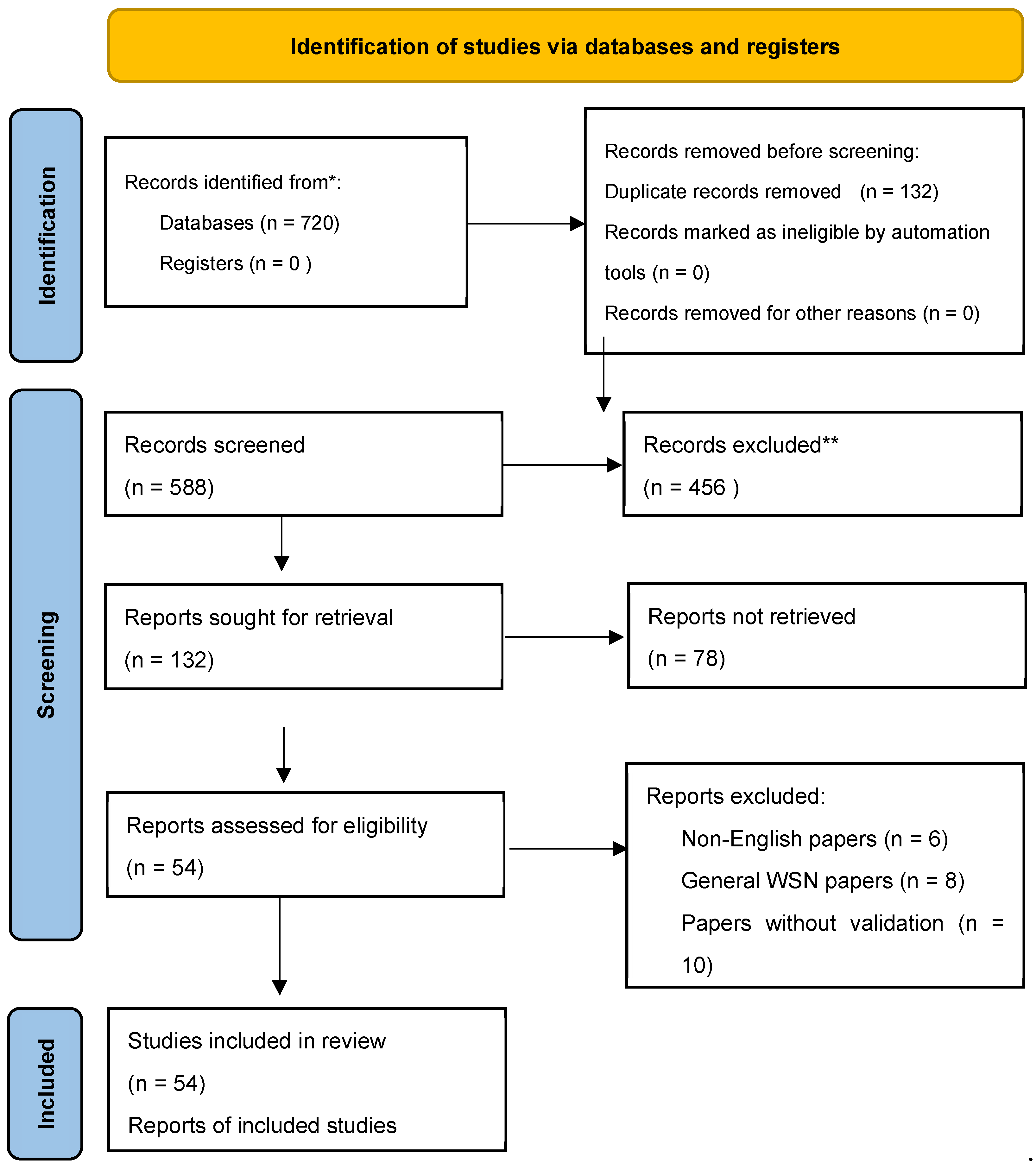

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Search Strategy and Data Sources

3.2. Search Query and Keywords

3.3. Study Selection Process

- Initial Retrieval: A total of 720 papers were identified from the Scopus database using the search query: ("Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks" OR "WRSN") AND ("Energy Efficiency" OR "Mobile Chargers" OR "Lifetime Enhancement" OR "Energy Optimisation" OR "Sensor Nodes").

- Duplicate Removal: After identifying and removing 132 duplicate records, 588 unique articles remained for screening.

- Title and Abstract Screening: Each paper was reviewed for relevance based on its title and abstract. Studies that did not explicitly focus on WRSN energy efficiency strategies or lacked technical contributions were excluded. This step resulted in the removal of 456 papers, leaving 132 for full-text review.

- Full-Text Review: The remaining 132 papers were assessed for methodological rigour, relevance to WRSN energy efficiency, scheduling or charging strategies, experimental validation or simulation results, and novel contributions compared to existing literature. After this evaluation, 78 papers were excluded for not meeting the selection criteria, resulting in a final set of 54 papers for inclusion in the review.

3.3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Peer-reviewed journal and conference articles published between January and December 2024.

- Papers focusing on charging strategies, energy management, and efficiency improvements in WRSN

- Studies presenting new methodologies, experimental validations, or simulations

- Exclusion Criteria:

- Non-English articles

- General wireless network studies without an emphasis on wireless power transfer or charging

- Papers without experimental validation, simulations, or practical applicability

3.3.2. Selection Methodology Justification

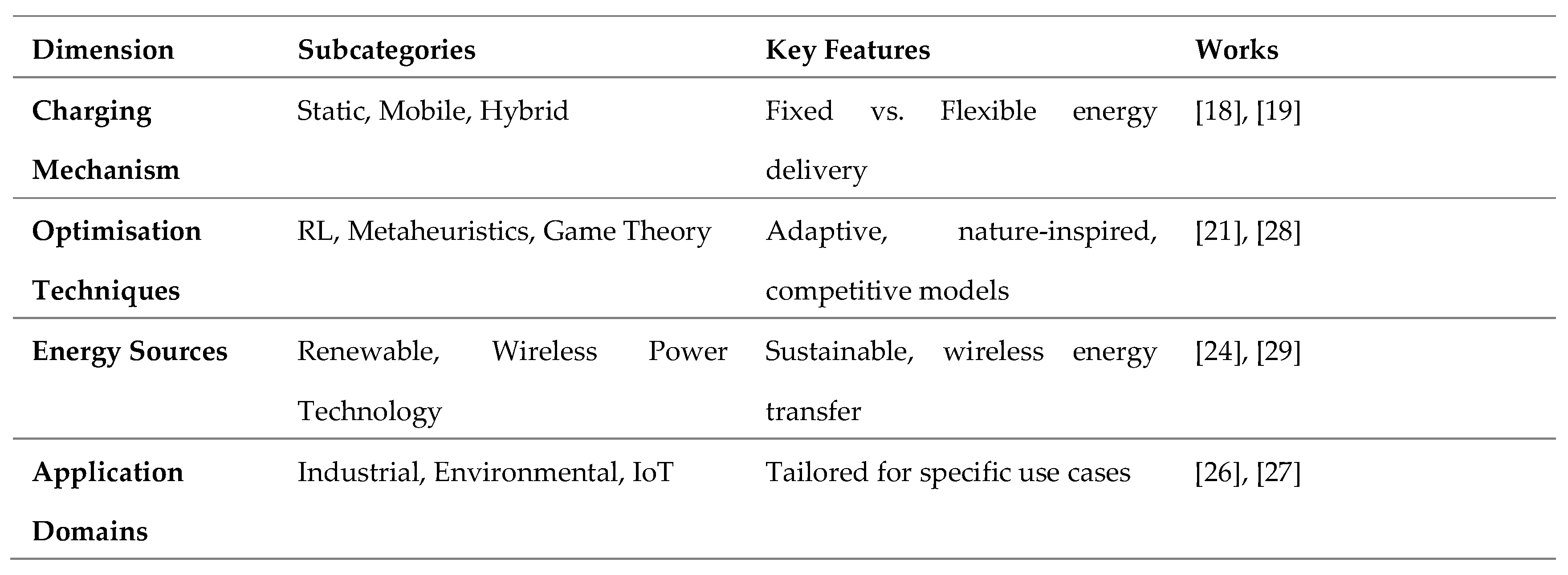

3.4.1. Rationale for Taxonomy Design

- Methodological Approach: The core technique or strategy used to address WRSN challenges.

- Optimisation Focus: The primary objectives of the articles are energy efficiency, charging path optimisation, and network longevity.

- Application Context: The practical scenario or domain where the proposed solution is applied.

3.4.2. Key Dimensions of the Taxonomy

3.4.2.1. Charging Mechanisms

- Static Chargers: Fixed energy sources.

- Mobile Chargers: UAVs or ground vehicles.

- Hybrid Systems: Combined static and mobile.

3.4.2.2. Optimization Techniques

- Reinforcement Learning (RL /DRL): Adaptive decision-making frameworks.

- Metaheuristics: Nature-inspired algorithms.

- Game Theory: Pricing and competition models.

- Fuzzy Logic and MCDM: Rule-based and multi-criteria systems.

3.4.2.3. Energy Management Objectives

- Minimising Node Deaths: Focused on prolonging network lifespan.

- Trajectory Optimization: Efficient path planning for mobile chargers.

- Energy Harvesting: Sustainable energy solutions.

3.4.2.4. Application Domains

- Industrial WRSNs: Tailored for factories or harsh environments.

- Large-Scale Networks: Solutions for expansive deployments.

- IoT Integration: Bridging WRSNs with IoT Ecosystems.

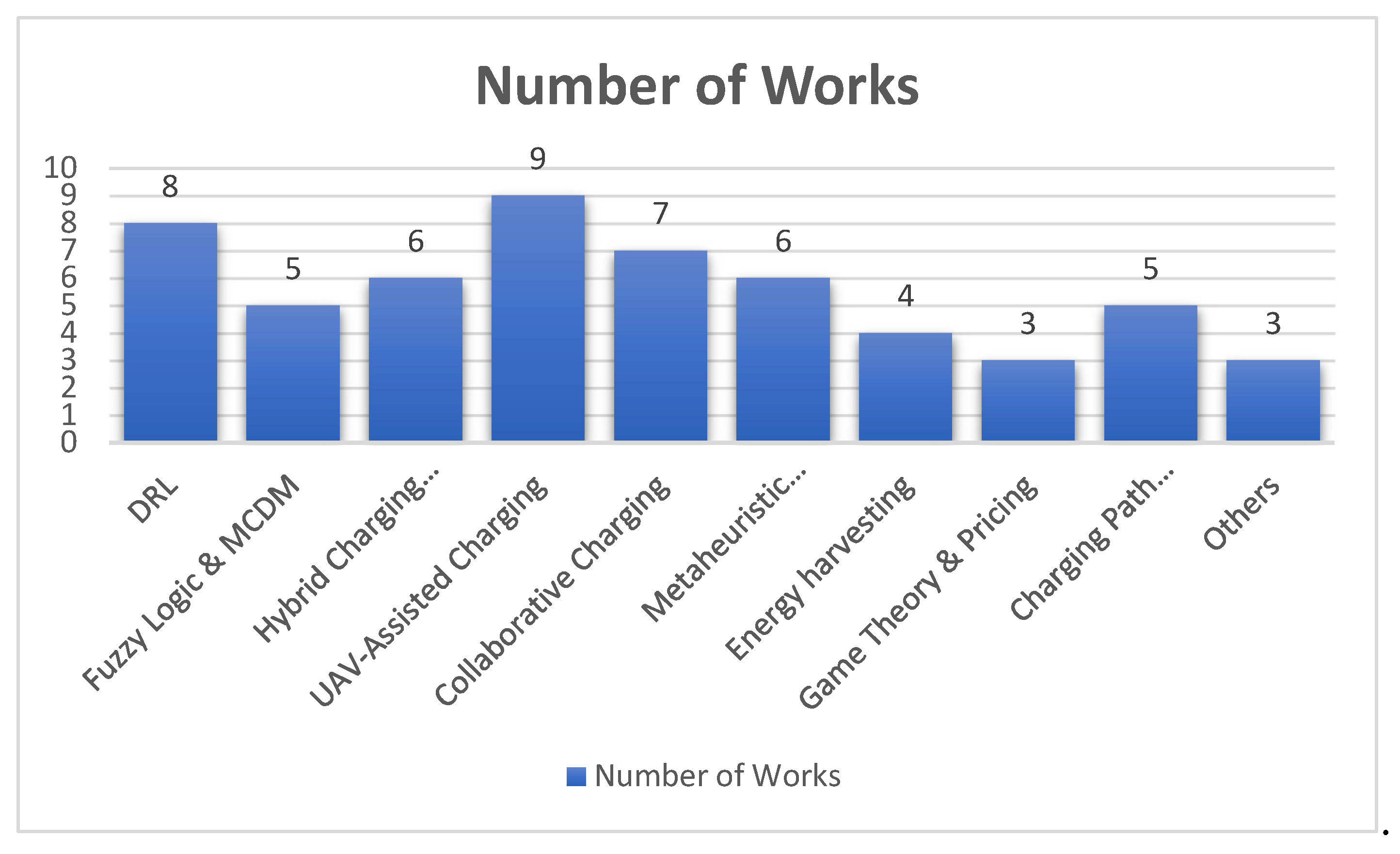

3.5. Thematic Structure Overview

- Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL): Adaptive, AI-driven strategies for dynamic charging.

- Fuzzy Logic and MCDM: Rule-based prioritisation and multi-objective decision-making.

- Hybrid Charging: Blending static and mobile energy delivery.

- UAV-Assisted Systems: Charging via drones with optimised trajectories.

- Collaborative Scheduling: Coordinating multiple chargers for efficiency.

- Metaheuristics: Nature-inspired algorithms for complex optimisation.

- Sustainability: Energy harvesting and green solutions.

- Game Theory: Market-driven pricing and competition models.

- Charging Path and Trajectory Optimization: Advanced trajectory planning for energy delivery.

3.5.1. Purpose of the Taxonomy

- Clarity: Simplifies navigation through diverse methodologies.

- Comparison: Highlights strengths/weaknesses of similar approaches.

- Gap Identification: Reveals underexplored areas, such as renewable energy integration in industrial WRSNs.

| Dimension | Subcategories | |

| 1 | Charging Mechanisms | Static, Mobile, Hybrid |

| 2 | Optimisation Techniques | DRL, Metaheuristics, Game Theory |

| 3 | Energy Objectives | Node Survival, Trajectory, Harvesting |

| 4 | Application Domains | Industrial, Large-Scale, IoT |

| Theme | Strengths | Limitations |

| DRL | Adaptability, dynamic decision-making | High computational complexity |

| Fuzzy Logic and MCDM | Prioritization, multi-criteria balance | Sensitivity to parameter tuning |

| Charging Path Optimisation | Reduced energy waste, obstacle avoidance | Dependency on accurate localization |

4. Taxonomy of WRSN Charging Strategies

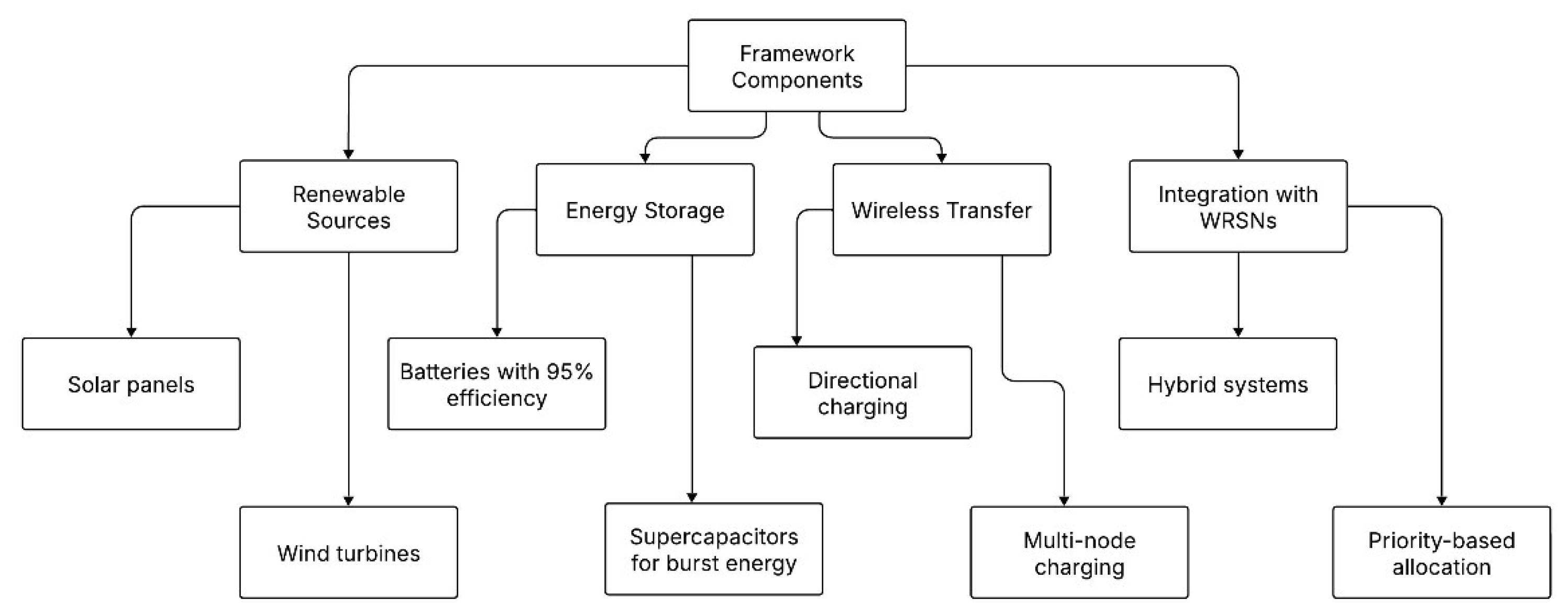

4.1. Classification Framework

- Charging Mechanisms: How energy is delivered to sensor nodes.

- Optimisation Techniques: The computational or algorithmic strategies used to optimise charging.

- Energy Sources: The types of energy used for charging.

- Application Domains: The practical scenarios where these strategies are applied.

4.2. Key Dimensions of Taxonomy

4.2.1. Charging Mechanisms

- Advantages: Reliable, minimal maintenance.

- Limitations: Limited coverage, inflexible in dynamic environments.

- Advantages: High flexibility and adaptability to dynamic networks.

- Limitations: High energy consumption and complex path planning.

- Advantages: Combines the strengths of static and mobile systems.

- Limitations: Increased complexity in coordination.

4.2.2. Optimization Techniques

- Advantages: High adaptability, suitable for dynamic environments.

- Limitations: Computationally intensive, requires extensive training.

- Metaheuristics: Nature-inspired algorithms for solving complex optimisation problems.

- Advantages: Effective for large-scale problems, robust to local optima.

- Limitations: High computational cost, probabilistic nature.

- Advantages: Realistic modelling of competitive scenarios.

- Limitations: Assumes rational behaviour, may not scale well.

- Advantages: Handles uncertainty and flexible prioritisation.

- Limitations: Sensitive to parameter tuning, may lack adaptability.

4.2.3. Energy Sources

- Renewable Energy: Energy harvested from natural sources like solar or wind.

- Advantages: Environmentally friendly, reduces dependency on external power.

- Limitations: Intermittent availability, requires energy storage.

- Advantages: Eliminates the need for physical connections.

- Limitations: Limited range, efficiency decreases with distance.

4.2.4. Application Domains

- Industrial WRSNs: Networks deployed in factories or industrial settings.

- Challenges: Harsh conditions and high-reliability requirements.

- Challenges: Remote locations, limited energy availability.

- Challenges: Scalability and interoperability with IoT devices.

4.2.5. Other Works

- Key Contributions: These works explore unconventional approaches, such as optimising charging pad placement or addressing security concerns in industrial settings.

- Further research is needed to integrate these niche solutions into mainstream WRSN frameworks.

5. Thematic Review of Emerging Research Directions

5.1. Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) in WRSNs

5.1.1. Base Structure and Formulae

- S: Set of states (e.g., node energy levels, charger positions).

- A: Set of actions (e.g., move to a node, charge a node).

- P: Transition probability P(s′∣s, α), the probability of moving to state s′ from state s after taking action α.

- R: Reward function R(s, α,s′), the immediate reward for taking action α in state s and transitioning to s′.

- γ: Discount factor (0≤γ≤10≤γ≤1), which determines the importance of future rewards.

5.1.2. Key Works and Contributions

- [28] Proposed a DRL-based Partial Charging Algorithm (DPCA) that dynamically allocates charging requests and optimises charging paths. This approach significantly improves packet arrival rates and reduces dead nodes.

- [31] Introduced an Adaptive Multi-node Charging Scheme with DRL (AMCS-DRL), which uses real-time network information to minimise node failures in large-scale WRSNs.

- [19] Developed a Deep Double Q-Network for Dynamic Charging-Recycling Scheduling (DDQN-DCRS), focusing on reducing waiting times and dead nodes through adaptive charging thresholds.

5.1.3. Comparative Analysis

- Strengths: DRL-based approaches excel in dynamic environments, offering high adaptability and real-time optimisation.

- Limitations: These methods are computationally intensive and require extensive training data, which can be challenging in resource-constrained WRSNs.

5.1.4. Future Directions

- Improvements: Developing lightweight DRL models for resource-constrained devices.

- Challenges: Addressing scalability issues and integrating DRL with other optimisation techniques.

5.2.1. Base Structure and Formulae

5.2.2. Key Works and Contributions

5.2.3. Comparative Analysis

- Advantages: Fuzzy logic and MCDM handle uncertainty effectively and provide flexible prioritisation.

- Challenges: These methods are sensitive to parameter tuning and may lack adaptability in highly dynamic environments.

5.2.4. Future Directions

- Integration: Combining fuzzy logic with machine learning for enhanced adaptability.

- Applications: Extending these techniques to multi-UAV systems and large-scale networks.

5.3 Hybrid Charging Schemes

5.3.1. Base Structure and Formulae

5.3.2. Key Works and Contributions

- [18] Proposed a Hybrid Charging Cooperative Scheme (HCCS) that uses fixed chargers in high-density areas and mobile chargers for on-demand energy delivery.

- [20] Introduced Hybrid Charging with Reinforcement Learning (HCRL), which optimises charging strategies using a combination of static and mobile chargers.

5.3.3. Comparative Analysis

- Effectiveness: Hybrid approaches reduce energy depletion and improve network longevity.

- Challenges: Coordinating static and mobile chargers can be complex, especially in dynamic environments.

5.3.4. Future Directions

- Scalability: Developing scalable solutions for large-scale deployments.

- Real-World Implementation: Testing hybrid schemes in real-world scenarios to validate their effectiveness.

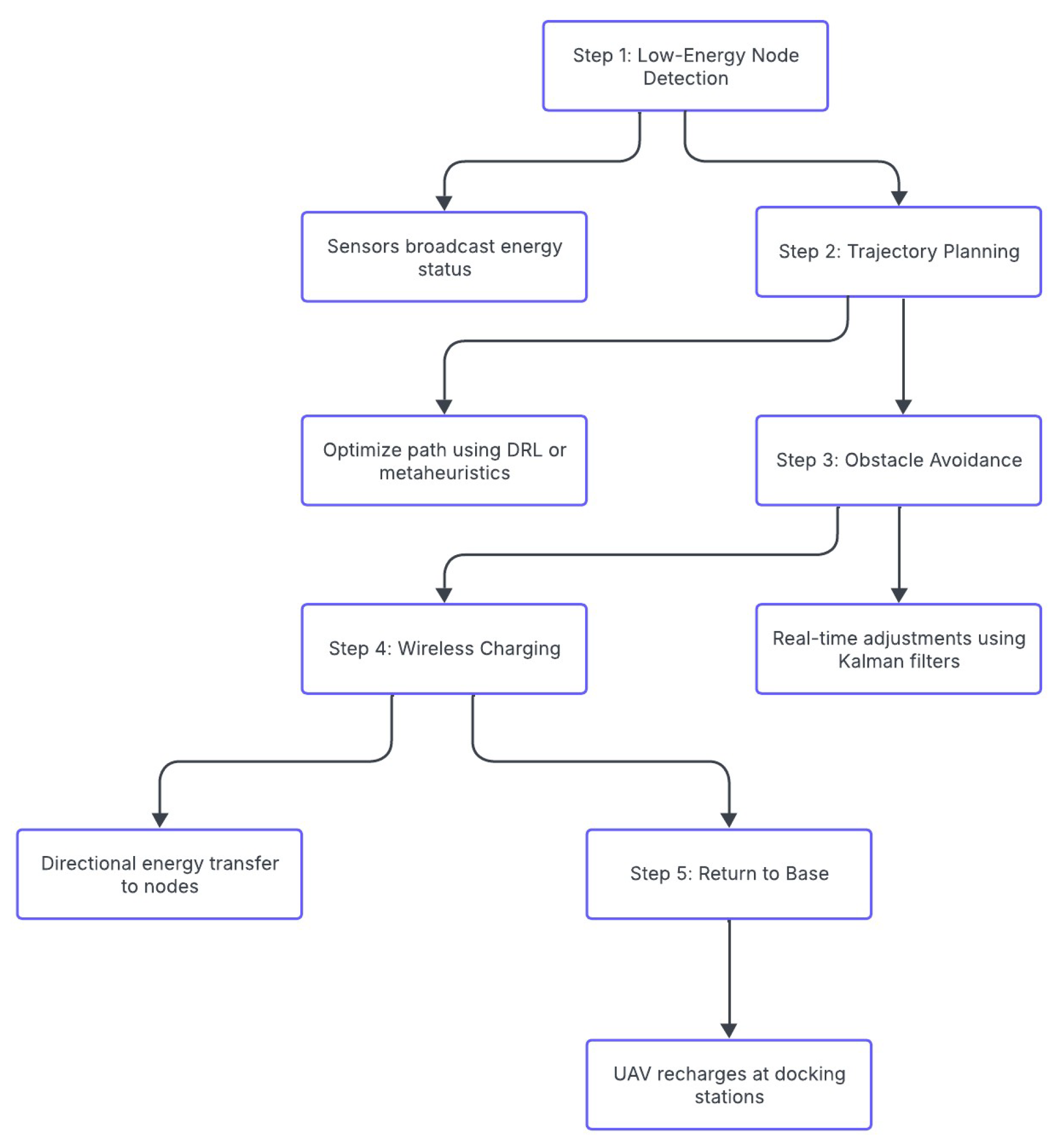

5.4. UAV-Assisted Charging and Trajectory Optimization

5.4.1. Base Structure and Formulae

5.4.2. Key Works and Contributions

5.4.3. Comparative Analysis

- Challenges: UAV energy constraints and obstacle avoidance remain significant hurdles.

- Advantages: UAVs offer unparalleled flexibility and adaptability in dynamic environments.

5.4.4. Future Directions

- Multi-UAV Coordination: Developing strategies for coordinating multiple UAVs to improve efficiency.

- Dynamic Environments: Enhancing UAV adaptability in unpredictable or changing environments.

5.5. Collaborative and Multi-Charger Scheduling

5.5.1. Base Structure and Formulae

- Objective: Minimize the maximum workload across all chargers:

5.5.2. Key Works and Contributions

5.5.3. Comparative Analysis

- Benefits: Multi-charger systems improve charging efficiency and reduce delays.

- Limitations: Increased complexity in coordination and resource allocation.

5.5.4. Future Directions

- Scalability: Developing scalable solutions for large-scale networks.

- Energy Efficiency: Optimizing energy consumption in multi-charger systems.

5.6. Metaheuristic and Optimization Algorithms

5.6.1. Base Structure and Formulae

5.6.2. Key Works and Contributions

5.6.3. Comparative Analysis

- Strengths: Metaheuristics are robust and effective for large-scale problems.

- Weaknesses: These methods can be computationally expensive and may require fine-tuning.

5.6.4. Future Directions

- Integration: Combining metaheuristics with machine learning for enhanced performance.

- Applications: Extending these techniques to multi-objective optimisation problems.

| Algorithm | Energy Efficiency (%) | Convergence Speed (Iterations) | Computational Time (s) |

| QACOA (Kumari 2024) | 92 | 150 | 45 |

| AOCS (Rahaman 2024) | 85 | 200 | 60 |

| MTS-HACO (Qin 2024) | 88 | 180 | 55 |

5.7. Energy Harvesting and Sustainability

5.7.1. Base Structure and Formulae

5.7.2. Key Works and Contributions

5.7.3. Comparative Analysis

- Challenges: Intermittent energy availability and storage limitations.

- Advantages: Environmentally friendly and cost-effective in the long term.

5.7.4. Future Directions

- Integration: Combining energy harvesting with other optimisation techniques.

- Scalability: Developing scalable solutions for large-scale networks.

5.8. Game Theory and Pricing Strategies

5.8.1. Base Structure and Formulae

5.8.2. Key Works and Contributions

5.8.3. Comparative Analysis

- Advantages: Realistic modelling of competitive scenarios.

- Limitations: Assumes rational behaviour and may not scale well.

5.8.4. Future Directions

- Real-World Applicability: Testing game-theoretic approaches in real-world scenarios.

- Scalability: Developing scalable solutions for large-scale networks.

5.9. Charging Path and Trajectory Optimization

5.9.2. Base Structure and Formulae

5.9.2. Key Works and Contributions

5.9.3. Comparative Analysis

- Challenges: Dynamic environments and scalability issues.

- Advantages: Improved energy efficiency and reduced charging delays.

5.9.4. Future Directions

- Real-Time Adaptability: Enhancing algorithms for real-time adaptability.

- Obstacle Avoidance: Developing robust solutions for environments with obstacles.

5.10. Others

5.10.1. Description

5.10.2. Key Contributions

5.10.3. Future Directions

5. Conclusion

5.1. Summary of Contributions

5.2. Implications for Future Research

5.3. Final Remarks

6. Discussion

6.1. Synthesis of Key Findings

6.1.1. Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) in WRSNs

6.1.2. Fuzzy Logic and Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM)

6.1.3. Hybrid Charging Schemes

6.1.4. UAV-Assisted Charging and Trajectory Optimization

6.1.5. Collaborative and Multi-Charger Scheduling

6.1.6. Metaheuristic and Optimization Algorithms

6.1.7. Energy Harvesting and Sustainability

6.1.8. Game Theory and Pricing Strategies

6.1.9. Charging Path and Trajectory Optimization

6.1.10. Others

6.2. Comparative Analysis of Themes

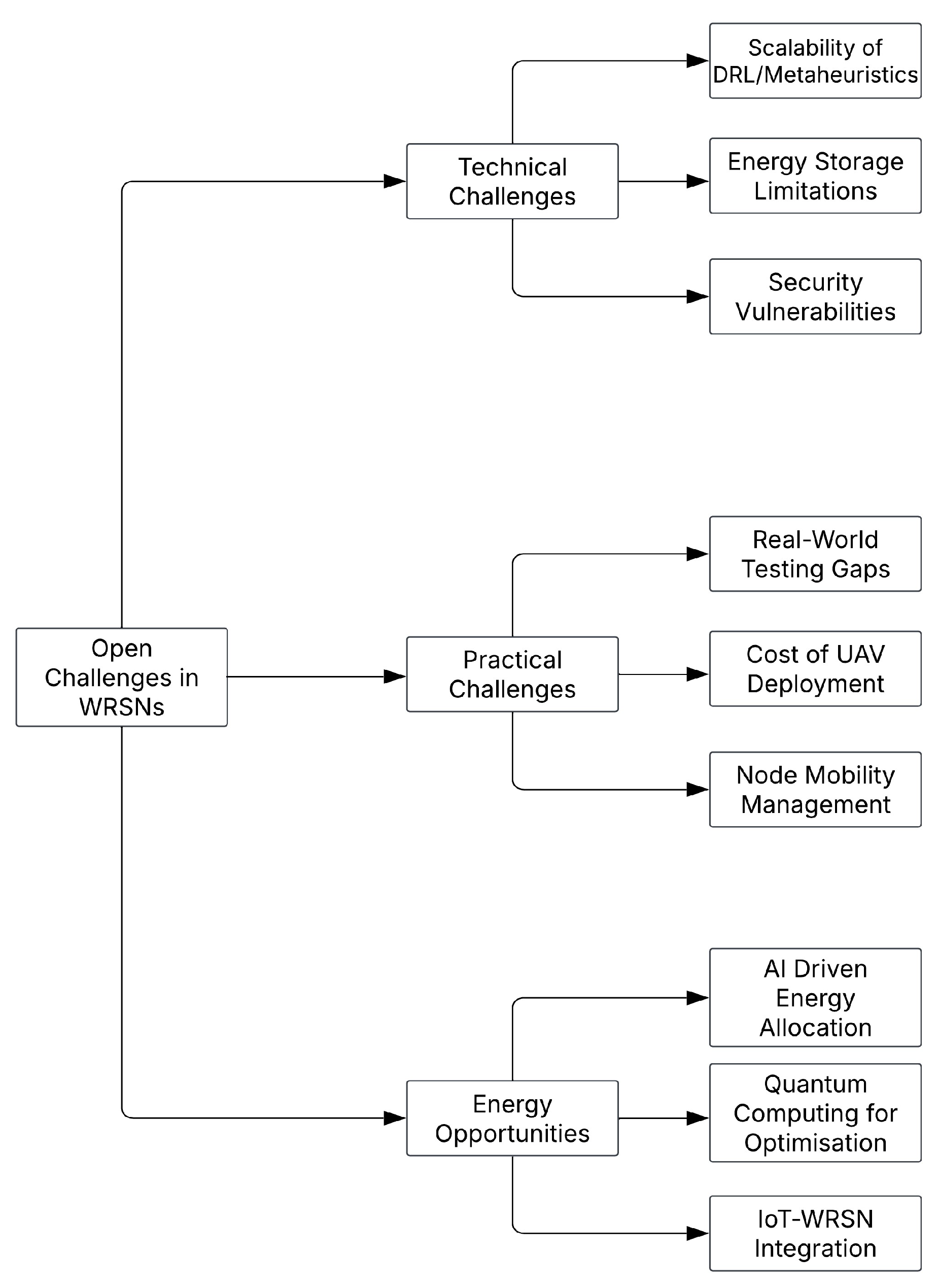

6.3. Open Challenges and Research Gaps

6.3.1. Scalability in Real-World Deployments:

6.3.2. Energy Source Integration and Efficiency:

6.3.3. Security and Privacy Concerns:

6.3.4. Coordination in Multi-Agent Systems:

6.3.5. Obstacle Handling and Dynamic Environments:

6.3.6. Integration of Machine Learning:

6.3.7. Real-World Validation and Testing:

6.4. Future Directions

- Developing lightweight Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) models that can operate efficiently on edge devices.

- Exploring hybrid energy systems (e.g., solar + wind) to enhance reliability and sustainability.

- Designing robust security protocols to safeguard data and energy transactions.

- Investigating advanced multi-agent coordination strategies for large-scale networks.

- Conducting extensive real-world testing to validate theoretical advancements.

7. Conclusion

7.1. Summary of Contributions

- Taxonomic Classification:

- Thematic Trends:

- Comparative Insights:

7.2. Implications for Future Research

- Scalability Solutions:

- Sustainability Integration:

- Security and Robustness:

- Real-World Validation:

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| DQN | Deep Q-Network |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| ETLBO | Enhanced Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization |

| FCNP | Fuzzy Clustering Node Placement |

| FA | Firefly Algorithm |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| HCCS | Hybrid Charging Cooperative Scheme |

| MCDM | Multi-Criteria Decision Making |

| MCV | Mobile Charging Vehicle |

| PBC | Priority-Based Charging |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| QACO | Quantum Ant Colony Optimization |

| RAN | Random Allocation Node |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| SAC | Soft Actor-Critic Algorithm |

| TOPSIS | Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| WET | Wireless Energy Transfer |

| WPT | Wireless Power Transfer |

| WRSN | Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Network |

| WSN | Wireless Sensor Network |

References

- Liu, Z.; Li, T.; Li, S.; Mi, C.C. Advancements and challenges in wireless power transfer: A comprehensive review. Nexus 2024, 1, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabsi, A.; Hawbani, A.; Wang, X.; Al-Dubai, A.; Hu, J.; Aziz, S.A.; Kumar, S.; Zhao, L.; Shvetsov, A.V.; Alsamhi, S.H. Wireless Power Transfer Technologies, Applications, and Future Trends: A Review. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Comput. 2025, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaoui, W.; Retal, S.; El Bhiri, B.; Kharmoum, N.; Ziti, S. Towards revolutionizing precision healthcare: A systematic literature review of artificial intelligence methods in precision medicine. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 2024, 46, 101475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawashin, D.; Nemer, M.; Gebreab, S.A.; Salah, K.; Jayaraman, R.; Khan, M.K.; Damiani, E. Blockchain applications in UAV industry: Review, opportunities, and challenges. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2024, 230, 103932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuvaraj, T.; Devabalaji, K.R.; Kumar, J.A.; Thanikanti, S.B.; Nwulu, N.I. A Comprehensive Review and Analysis of the Allocation of Electric Vehicle Charging Stations in Distribution Networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 5404–5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hawbani, A.; Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Z.; Alsamhi, S. A DRL-based Partial Charging Algorithm for Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. ACM Trans. Sen. Netw. 2024, 20, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.R.S.; Gopikrishnan, S. Caddisfalcon optimization algorithm for on-demand energy transfer in wireless rechargeable sensors based IoT networks. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2024, 64, 103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Yang, W.; Dai, H.; Obaidat, M.S.; Wang, L.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Q. Maximizing Charging Utility With Fresnel Diffraction Model. IEEE Trans. on Mobile Comput. 2024, 23, 11685–11699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Kaur, K.; Singh, K.; Saleem, K.; Ur Rehman, A.; Gupta, R.; Hussen Adem, S. Energy-efficient artificial fish swarm-based clustering protocol for enhancing network lifetime in underwater wireless sensor networks. J Wireless Com Network 2024, 2024, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Nyitamen, D.S. An Overview of On-Demand Wireless Charging as a Promising Energy Replenishment Solution for Future Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. Journal of Computing and Communication 2024, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammodi, Z.; Al Hilli, A.; Al-Ibadi, M. Energy Optimization in Wireless Sensor Networks: A Review. Iraqi Journal for Computer Science and Mathematics 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijemaru, G.K.; Ang, K.L.-M.; Seng, J.K.P.; Nwajana, A.O.; Yeoh, P.L.; Oleka, E.U. On-Demand Energy Provisioning Scheme in Large-Scale WRSNs: Survey, Opportunities, and Challenges. Energies 2025, 18, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Dai, H.; Liu, T.; Deng, X.; Dou, W.; Yang, Y.; Chen, G. Understanding Wireless Charger Networks: Concepts, Current Research, and Future Directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2024, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, R. Energy-Efficient Routing in Wireless Sensor Networks: A Meta-heuristic and Artificial Intelligence-based Approach: A Comprehensive Review. Arch Computat Methods Eng 2024, 31, 2109–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaswan, A.; Jana, P.K.; Das, S.K. A Survey on Mobile Charging Techniques in Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2022, 24, 1750–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, M.; Mansoor, A.M.; Ahmad, R. A systematic literature review on mobility in terrestrial and underwater wireless sensor networks. Int J Communication 2021, 34, e4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Tang, S.; Chen, Y.; Lin, F. A Hybrid Charging Scheme for Minimizing the Number of Energy-Exhausted Nodes in Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. IEEE Sensors J. 2024, 24, 17169–17182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Deng, Z.; Feng, Y.; Liu, N. Deep-Reinforcement-Learning-Based Joint Energy Replenishment and Data Collection Scheme for WRSN. Sensors 2024, 24, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallikarjuna, M.; Amgoth, T. A hybrid charging scheme for efficient operation in wireless sensor network. Wireless Netw 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, B.; Yadav, A.K.; Kumar, R.R. Towards Perpetual Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks with Path Optimization of Mobile Chargers. SN COMPUT. SCI. 2024, 5, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Bhatnagar, M.R. A Non-Cooperative Pricing Strategy for UAV-Enabled Charging of Wireless Sensor Network. IEEE Trans. on Green Commun. Netw. 2024, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Sha, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, R. A Fuzzy Logic-Based Directional Charging Scheme for Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. Sensors 2024, 24, 5070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Deng, T.; Liu, Y.; Lin, F. Charging Between PADs: Periodic Charging Scheduling in the UAV-Based WRSN With PADs. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks 2024, 2024, 8851835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.M.; Tufail, A.; Apong, R.A.A.H.M.; De Silva, L.C.; Kalinaki, K.; Namoun, A. ICS Deployment Optimization with Time Delay Reduction and Energy-Efficiency in IWSNs. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC); IEEE: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Sha, C.; Zhu, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, R. Charging Scheduling Method for Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks Based on Energy Consumption Rate Prediction for Nodes. Sensors 2024, 24, 5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, N.; Wang, H.; Aslam, M.F.; Aamir, M.; Hadi, M.U. Intelligent Wireless Charging Path Optimization for Critical Nodes in Internet of Things-Integrated Renewable Sensor Networks. Sensors 2024, 24, 7294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.-H.; Yu, C.-W.; Zhang, Z.-L. Optimizing Charging Pad Deployment by Applying a Quad-Tree Scheme. Algorithms 2024, 17, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, H.-C. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shakya, A.K.; Pillai, G.; Chakrabarty, S. Reinforcement learning algorithms: A brief survey. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 231, 120495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, A.D.; Tran, H.T.; Pham, H.N.Q.; Bui, Q.M.; Ngo, T.P.; Huynh, B.T.T. An adaptive charging scheme for large-scale wireless rechargeable sensor networks inspired by deep Q-network. Neural Comput & Applic 2024, 36, 10015–10030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, H.; Xiao, W. A reinforcement learning based mobile charging sequence scheduling algorithm for optimal sensing coverage in wireless rechargeable sensor networks. J Ambient Intell Human Comput 2024, 15, 2869–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, J.S.; Ri, M.G.; Pak, S.H.; Kim, U.S. FCVM(i): Integrated FCNP-VWA-MCDM(i) Methods for On-Demand Charging Scheduling in WRSNs. JDSIS 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, X.; Qin, X. Efficient and Economical UAV-Facilitated Wireless Charging and Data Relay Trajectory Planning for WRSNs. In Proceedings of the ICC 2024 - IEEE International Conference on Communications; IEEE: Denver, CO, USA, 2024; pp. 4221–4226. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Chang, C.-Y.; Guan, W.; Wang, Y.; Sinha Roy, D. MC3: A Multicharger Cooperative Charging Mechanism for Maximizing Surveillance Quality in WRSNs. IEEE Sensors J. 2024, 24, 17080–17091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, Z.; Yang, L. Collaborative Charging Scheduling in Wireless Charging Sensor Networks. CMC 2024, 79, 1613–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, S.M.A.; Azharuddin, M.; Shameem, M. Unveiling Efficient Partial Charging Schedules for Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks Using Novel Aquila Optimization Approach. Arab J Sci Eng 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaisar, M.U.F.; Yuan, W.; Bellavista, P.; Liu, F.; Han, G.; Zakariyya, R.S.; Ahmed, A. Poised: Probabilistic On-Demand Charging Scheduling for ISAC-Assisted WRSNs With Multiple Mobile Charging Vehicles. IEEE Trans. on Mobile Comput. 2024, 23, 10818–10834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wu, D.; Gao, J.; Sun, W.; Yang, J.; Liu, T. Dynamic Power Distribution Controlling for Directional Chargers. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2024 - IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; IEEE: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2024; pp. 2059–2068. [Google Scholar]

- Ri, M.G.; Kim, I.G.; Pak, S.H.; Jong, N.J.; Kim, S.J. An integrated MCDM-based charging scheduling in a WRSN with multiple MCs. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2024, 17, 3286–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, S.M.A.; Azharuddin, M.; Kuila, P. Efficient Scheduling of Charger-UAV in Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks: Social Group Optimization Based Approach. J Netw Syst Manage 2024, 32, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SN | Authors | Focus | Key Contributions | Limitations | Gaps Identified |

| 1 | [15] | Mobile Charging Techniques (MCTs) for WRSNs | Categorizes MCTs into periodic and on-demand methods; Discusses coverage, connectivity, and energy optimization | Lacks depth in real-world applications; Superficial analysis of collaborative charging and hybrid provisioning | Underutilization of AI; Need for multi-source energy harvesting.; No innovative solutions proposed |

| 2 | [16] | Impact of mobility on WSN performance (terrestrial and underwater) | Highlights use of UAVs and UMEs for data collection, charging, and localization | Surface-level analysis; no critical evaluation of practical challenges or scalability | Limited exploration of dynamic environments; no bold vision for future research |

| 3 | [10] | On-demand wireless charging schemes in WRSNs | Emphasizes advantages of on-demand over periodic charging; mentions AI and mobile edge computing | Overly theoretical; lacks concrete examples or case studies; no detailed taxonomy or classification | No practical implementation insights; shallow treatment of AI and edge computing |

| 4 | [11] | Energy optimization in WSNs | Summarizes energy-efficient protocols and strategies | Lacks critical analysis; ignores real-world challenges like dynamic environments and obstacles | No innovative solutions; superficial classification framework |

| 5 | [13] | Evolution of WRSNs, BF-WSNs, and WPCNs | Covers charger deployment, scheduling strategies, and communication optimization | Shallow analysis; no innovative solutions; disconnected from real-world applications | No actionable roadmap: future directions (e.g., AI, 6G) lack connection to current advancements |

| 6 | [14] | Energy-efficient routing in WSNs (meta-heuristic and AI-based approaches) | Catalogs bio-inspired algorithms and AI integration | Lacks practical examples, case studies, or discussion on data privacy and security; no clear taxonomy | Needs to bridge theory and real-world applications, offering actionable insights |

| 7 | [12] | On-demand energy provisioning in large-scale WRSNs | Categorizes energy harvesting sources (solar, kinetic) and storage technologies (supercapacitors, batteries) | Lacks critical evaluation of real-world performance, shallow discussion of energy management strategies | No bold proposals for improvement; does not address practical constraints |

| Parameter | [15] | [16] | [10] | [11] | [13] | [14] | [12] |

| Scope and Relevance | Covers mobile charging but lacks depth (3) | Covers terrestrial and underwater WRSNs but lacks foundational depth (3) | Touches on on-demand charging but lacks real-world examples (3) | Focuses on energy optimization but lacks practical applications (3) | Covers WRSNs broadly but misses practical insights | Lacks depth in practical applications (3) | Covers WRSNs broadly but lacks real-world deployment challenges (3) |

| Literature Coverage | Includes key studies but omits recent developments (3) | Covers key studies but lacks foundational depth (3) | Mentions advancements but lacks depth, especially in AI and MEC (3) | Discusses various studies but overlooks dynamic environments (3) | Covers key studies but fails to provide an exhaustive review (3) | Overlooks foundational studies and case studies (3) | Lacks critical evaluation of cited studies (3) |

| Organization and Structure | Somewhat logical but needs clearer sectioning (3) | Logical but could improve categorization of mobile elements (3) | Covers design issues and performance but feels disjointed (3) | Structured into relevant sections but lacks cohesiveness (3) | Well-structured but offers superficial topic treatment (3) | No clear taxonomy, making comprehension difficult (3) | Clear structure but lacks deep insights in each section (4) |

| Critical Analysis | Compares techniques but lacks depth and insight (3) | Limited comparison of methodologies, lacks critique (2) | Summarizes methods but fails to challenge the status quo (2) | Superficial analysis with no innovative comparisons (2) | Lacks deep comparative analysis of methodologies (2) | Lacks deep comparison of methodologies (2) | Presents data descriptively rather than analytically (2) |

| Research Gaps and Future Directions | Identifies gaps but offers weak future directions (3) | Identifies gaps but lacks innovative research suggestions (3) | Highlights scalability and efficiency issues but lacks actionable insights (3) | Mentions gaps but does not provide a clear research roadmap (2) | Suggests directions but they feel speculative (3) | Mentions gaps but lacks detailed exploration (3) | Points out gaps but does not explore them in depth (3) |

| Methodology of the Review | Mentions methodology but lacks systematic rigor (3) | Systematic but lacks transparency, raising bias concerns (3) | Literature selection unclear, making conclusions questionable (2) | No clear literature selection method described (2) | Weak methodology description, limiting credibility (2) | Unclear literature selection process (2) | Lacks a well-defined literature review process (2) |

| Thematic Categorization and Taxonomy | Classification present but could be expanded (3) | Basic taxonomy, missing diversity in research themes (3) | Basic classification but lacks a comprehensive framework (3) | Provides themes but lacks a guiding taxonomy (3) | Tries to categorize WRSNs but lacks depth (3) | No structured classification system (2) | Provides a classification but lacks detail (3) |

| Citations and References | Credible but lacks diversity (3) | Credible but could incorporate broader perspectives (3) | Proper citations but relies on a narrow set of sources (4) | Uses credible sources but lacks recent studies (3) | Limited reference diversity weakens the review (3) | Fails to assess source credibility (3) | Uses diverse sources but lacks critical engagement (4) |

| Writing Quality and Clarity | Generally clear but could be more concise and logical (3) | Clear but lacks engaging narrative (3) | Writing is clear but lacks examples and case studies (3) | Clear writing but lacks in-depth analysis (3) | Clear but explanations need more detail (3) | Lacks examples and case studies (3) | Writing is understandable but could be more engaging (3) |

| Contribution to the Field | Provides some insights but lacks unique perspectives (3) | No groundbreaking insights; needs a fresh survey (2) | Adds little new knowledge, mostly a recap of existing work (3) | Offers an overview but lacks novel contributions (2) | Provides insights but does not significantly advance the field (2) | Limited originality and research impact (2) | Broad overview but lacks innovation (3) |

| Metric | [28] | [31] | [32] |

| Adaptability | 9/10 | 8/10 | 9/10 |

| Computational complexity | High | Medium | High |

| Scalability | Moderate | High | Low |

| Energy Efficiency | 85% | 78% | 88% |

| Node Survival Rate | 92% | 85% | 94% |

| S/N | Theme | Key Works | Strengths | Limitation |

| 1 | DRL | [6,31,32] | Adaptability, dynamic decision-making | High computational complexity |

| 2 | Fuzzy Logic and MCDM | [23,40] | Prioritization, multi-criteria balance | Sensitivity to parameter tuning |

| 3 | Hybrid Charging | [18,20] | Combines static and mobile strengths | Increased complexity in coordination |

| 4 | UAV-Assisted Charging | [32,34] | High flexibility, obstacle avoidance | UAV energy constraints |

| 5 | Collaborative Scheduling | [35,36] | Improved efficiency, reduced delays | Complexity in coordination |

| 6 | Metaheuristics | [21,41] | Robust, effective for large-scale problems | Computationally expensive |

| 7 | Energy Harvesting | [24,26] | Sustainable, environmentally friendly | Intermittent energy availability |

| 8 | Game Theory | [22,38] | Realistic modeling of competitive scenarios | Assumes rational behavior |

| 9 | Charging Path Optimization | [29,39] | Improved energy efficiency, reduced delays | Dynamic environments, scalability issues |

| 10 | Others | [28] | Niche solutions, unique contributions | Limited integration with mainstream methods |

| Theme | Strengths | Weaknesses |

| DRL | Adaptability, real time decision making | High computational cost, slow convergence |

| Fuzzy logic and MCDM | Handles uncertainty, multi-criteria balance | Sensitive to parameter tuning |

| UAV-Assisted Charging | Flexibility, obstacle avoidance | Limited battery life, complex path planning |

| Metaheuristics | Solves large-scale problems, robust | Computationally intensive, probabilistic |

| Energy Harvesting | Sustainable, reduces external dependency | Intermittent energy sources, storage issues |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).