1. Introduction

The advent of quantum computing poses a significant threat to existing cryptographic systems, necessitating a transition to post-quantum cryptography (PQC). Recent advancements, such as Google’s Willow quantum chip and Microsoft’s Majorana 1 chip, have demonstrated breakthroughs in quantum error correction, potentially bringing us closer to cryptographically relevant quantum computers (CRQCs). Microsoft’s chip with a quantum processor that uses topological qubits, is designed to be more robust against errors, which could significantly improve the reliability of quantum computations and thus hasten the advent of CRQCs[

1]. HPCwire’s 2025 article highlights that these developments could enable CRQCs within the next decade, threatening traditional algorithms like RSA and elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) [

2,

3]. SecurityWeek’s 2025 report corroborates this, projecting a timeline for CRQCs to emerge, underscoring the urgency for quantum-resistant solutions [

4], particularly relevant for cloud-based cryptographic operations, where both security and energy efficiency must be optimized simultaneously. This transition becomes especially critical as AI systems increasingly handle sensitive data processing tasks in cloud environments, where both quantum resistance and energy efficiency are crucial considerations.

As a result of the above innovations, the protection of sensitive information has become more critical than ever. Homomorphic encryption enables calculations on encrypted data without the need to access private keys [

5]. This capability allows data such as salaries and pensions to be stored in an encrypted form and securely updated without decryption. This approach has gained significant popularity with the proliferation of cloud computing. Companies increasingly store their data in the cloud rather than on-premise systems, elevating the importance of robust security measures.

In response, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) finalized the first three PQC standards in 2024, including ML-KEM, ML-DSA, and SPHINCS+, to ensure long-term security against quantum attacks [

6]. Furthermore, governmental initiatives are underway to prepare for this transition, with the US government issuing guidelines for PQC adoption, emphasizing the need for a coordinated approach. The United Nations’ designation of 2025 as the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology further underscores the global significance of these developments.

The proliferation of cloud computing and AI applications has significantly increased data center energy consumption, raising environmental concerns. The International Energy Agency (IEA) reports that data centers currently account for approximately 1% of global electricity consumption, with projections indicating a potential doubling by 2026 due to the AI boom [

7]. In the United States, Datacenter Dynamics’ 2025 analysis predicts a rise from 17 GW in 2020 to 35 GW by 2030, driven by hyperscale data centers and AI workloads. This escalation not only increases operational costs but also amplifies the environmental footprint, with Scope 1-3 emissions (direct, indirect from purchased electricity, and supply chain impacts) becoming a critical metric [

8]. The rapid adoption of large-scale AI models and automated systems has further accelerated this energy consumption trend, making the optimization of underlying cryptographic operations increasingly important for overall data center sustainability.

The Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) further projects that data centers could consume up to 9% of US electricity by 2030, highlighting the sustainability challenge posed by AI-driven demand [

9]. Park Place Technologies’ 2024 study emphasizes the environmental impact, noting that cooling systems and continuous uptime contribute to greenhouse gas emissions, particularly in hyperscale facilities [

10]. These findings underscore the need for energy-efficient solutions in data center operations, especially as cryptographic workloads intensify.

Without homomorphic encryption, encrypted data must be decrypted, updated, and then re-encrypted. All updates must be performed on-premises, or the private key must be transmitted to the cloud, which introduces security risks. With homomorphic encryption, sensitive data can be stored and updated directly in the cloud without exposing the private key.

Homomorphic encryption (HE) is a pivotal technology for secure cloud computing, enabling computations on encrypted data without decryption. Fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) supports arbitrary operations, such as addition and multiplication, but is computationally intensive, posing challenges for energy efficiency, particularly in AI and blockchain applications. Venafi’s 2025 analysis highlights FHE’s energy intensity, noting its limitations in large-scale deployments [

11]. In contrast, partially homomorphic encryption (PHE), which restricts operations to either addition or multiplication, offers a more energy-efficient alternative, suitable for specific use cases where full homomorphicity is not required[

12,

13,

14]. With the growing deployment of AI-driven applications in cloud environments, the energy efficiency of cryptographic operations becomes a critical factor in managing the overall environmental impact of these systems.

Fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) allows for both addition and multiplication on ciphertexts [

15]. Conversely, partially homomorphic encryption (PHE) is more limited, supporting either addition or multiplication, but not both [

16]. PHE algorithms can also multiply a ciphertext by a known constant and support regenerating ciphertexts, meaning the same plaintext can have different ciphertext representations. PHE schemes find applications in various contexts such as e-voting and Private Information Retrieval [

17]. However, these applications have been limited in scope due to constraints on the types of homomorphic evaluation operations they support. Essentially, PHE schemes are only applicable to specific scenarios where the algorithms involve either addition or multiplication operations exclusively.

Although FHE has become more accessible, PHE is often a more efficient and practical choice for many tasks. PHE is faster, requires fewer computational resources, generates smaller ciphertexts, and uses smaller keys. It is well-suited for environments with limited memory and strikes a good balance for practical applications.

In this paper, LightPHE, a lightweight and hybrid partially homomorphic encryption framework for Python, is used. It is open-sourced at

https://github.com/serengil/lightphe and licensed under MIT. While several FHE options are available, such as SEAL [

18], TenSEAL [

19], Pyfhel [

20], or PyFHE [

21], there is a notable lack of PHE frameworks. LightPHE aims to address this gap by providing a library that encapsulates various PHE algorithms, including RSA [

22], ElGamal [

23], Exponential ElGamal, Elliptic Curve ElGamal [

24], Paillier [

25], Damgard-Jurik [

26], Okamoto–Uchiyama [

27], Benaloh [

28], Naccache–Stern [

29], and Goldwasser–Micali [

30]. The design of the framework adheres to best practices in software engineering.

Recent research has focused on optimizing HE for energy efficiency. An arXiv paper from 2024 explores Computing-in-Memory (CiM) architectures, demonstrating reduced latency and energy consumption for HE operations [

31]. Similarly, IEEE Spectrum’s 2023 article discusses hardware accelerators, such as RISE, enhancing HE’s feasibility on edge devices, though further developments are needed for data center scalability [

32]. These advancements suggest a pathway to mitigate the energy demands of HE, aligning with sustainability goals.

In this broader context, organizations aiming to address sustainability must also consider their Scope 1 (direct), Scope 2 (indirect from purchased electricity), and Scope 3 (all other indirect) emissions. Advanced cryptographic methods, including both PHE and FHE, can introduce additional computational overhead, potentially elevating data center power usage [

7,

8]. Even a slight increase in the required processing power can translate to higher cooling demands and greater greenhouse gas emissions, emphasizing the need for energy-optimized cryptographic solutions. As data centers scale to meet AI-driven workloads, striking a balance between robust encryption and minimal environmental impact becomes ever more critical.

Moreover, the rapid deployment of large-scale AI models amplifies this challenge, as extensive training and inference cycles demand substantial computing resources [

9,

10]. Cryptographic operations, particularly those running continuously in cloud environments, can compound the energy requirements if not carefully optimized. Evaluating the full life cycle of cryptographic hardware, from raw material extraction (contributing to Scope 3) to disposal, is essential for a holistic view of environmental impact. By adopting encryption methods that reduce computational overhead while preserving security guarantees, organizations can mitigate their overall carbon footprint across all scopes and support a more sustainable trajectory for cloud and AI ecosystems.

1.1. Organization of the Paper

In

Section 3, the various algorithms supported by LightPHE are explored. Each algorithm’s capabilities and the theoretical underpinnings of their homomorphic features are explained. A range of algorithms, including RSA, ElGamal, Paillier, and others, are covered. The application of these algorithms to encrypted data, ensuring the security of sensitive information without the need for decryption, is demonstrated.

Moving on to

Section 4.1, a detailed examination of the design and structure of LightPHE is provided. The different components of the framework are broken down and their integration is explained. Using diagrams and clear explanations, the management of tasks such as encryption, computation, and decryption by LightPHE is illustrated. This section aims to enhance readers’ understanding of the framework’s functionality and reliability.

In

Section 5, the practical use of LightPHE is detailed. Examples and code snippets are provided to guide users through integrating LightPHE into their Python projects. By breaking down the implementation details and offering practical advice, the section aims to facilitate researchers and developers in maximizing the utilization of LightPHE’s features.

In addition to proposing LightPHE, extensive experiments were conducted to evaluate its performance across various cloud environments, including Colab Normal, Colab A100 GPU, Colab L4 GPU, Colab T4 High RAM, Colab TPU2, and Azure Spark. These experiments focused on several critical parameters, including time consumption for key generation, encryption, decryption, and homomorphic operations such as addition or multiplication for different key sizes.

Recent advancements in cloud computing and homomorphic encryption have significantly influenced the design and deployment of secure and efficient cryptographic systems. By leveraging the unique capabilities of these cloud environments, detailed benchmarks were established to provide a comprehensive performance analysis of LightPHE. This analysis not only highlights the practical differences between various cloud setups but also serves as a valuable benchmark for practitioners and researchers in selecting the appropriate environment for their specific needs.

Radar maps were created to visualize and compare the performance metrics across these diverse cloud environments. These visual tools offer insights into the strengths and weaknesses of each setup, aiding in the decision-making process for deploying homomorphic encryption in production systems. The comparative analysis emphasizes factors such as computational efficiency, scalability, and resource utilization, which are crucial for determining the suitability of a particular cloud environment for real-world applications.

Furthermore, the benchmarks provide guidance on selecting the optimal cloud environment based on specific use cases and performance requirements. For instance, environments like Colab A100 GPU and TPU2 are evaluated for their superior computational power, making them suitable for tasks requiring high performance and scalability. Conversely, setups like Colab Normal and Azure Spark are assessed for their cost-effectiveness and accessibility, offering viable options for projects with limited resources.

Following these sections, we introduce a dedicated 2, section (not shown here) to define Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions and discuss their significance in data center operations. We then expand our that approach to detailing the energy consumption measurement design, including data-collection methods, approximations for hardware power usage, and the calculation of carbon emissions based on typical grid intensities. In this expanded methodological framework, we also address quantum-era security concerns—particularly the impact of larger key sizes on both performance and potential carbon footprint.

Finally, result section is reorganized to include energy and emission metrics, where we correlate the computational performance of different algorithms and key sizes with estimated energy consumption and associated carbon emissions. This holistic view helps stakeholders balance strong cryptographic security with environmental considerations, guiding them toward sustainable implementations of homomorphic encryption technologies.

The insights gained from these experiments are intended to assist organizations in making informed decisions about the deployment of homomorphic encryption technologies in their production systems. By understanding the performance characteristics of different cloud environments—alongside their respective energy usage and emission impacts—stakeholders can better align their infrastructure choices with both operational and sustainability goals, ensuring a robust, efficient, and environmentally responsible implementation of LightPHE.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Design and Architecture

An abstract class in programming is a class that cannot be instantiated on its own and is designed to be subclassed, typically containing one or more abstract methods that must be implemented by its subclasses [

41]. The LightPHE framework is designed with a generic abstract class called Homomorphic. This class will include all the necessary methods for homomorphic operations, such as the addition of ciphertexts, multiplication of ciphertexts, xor of ciphertext, scalar multiplication of a ciphertext with a constant, and ciphertext regeneration. In addition to these homomorphic operations, the Homomorphic abstract class will have methods for generating key pairs for the cryptosystem, as well as methods for encryption and decryption.

Besides, each PHE algorithm generates different type of ciphertexts. Basically, this specifies the design of the class.

Table 3 shows ciphertext types of these algorithms and also the random key availability in the encryption process.

Each partially homomorphic encryption (PHE) algorithm will have its own class that inherits from the Homomorphic abstract class. Abstract class covers all ciphertext types whereas PHE algorithms’ classes followed the design mentioned in

Table 3.

For additively homomorphic algorithms, the framework will throw exceptions in PHE classes for homomorphic multiplication and homomorphic XOR operations, as these are not supported by these algorithms. For multiplicatively homomorphic algorithms, the framework will throw exceptions for homomorphic addition and homomorphic XOR operations. Additionally, exceptions will be thrown for scalar multiplication and ciphertext regeneration because these operations are only supported by additively homomorphic algorithms. For exclusively homomorphic algorithms, the framework will throw exceptions for both homomorphic addition and homomorphic multiplication. Similarly, exceptions will be thrown for scalar multiplication and ciphertext regeneration because these operations are only supported by additively homomorphic algorithms. In that way, each PHE algorithm class will have same methods.

Users will only interact with LightPHE class and they do not have to play with backend cryptosystems’ classes at all. Once a cryptosystem is created, it will have its own encrypt and decrypt methods. Encrypt method will return a Ciphertext class, with the returned values from backend cryptosystems set to the value argument of the Ciphertext class. Addition, multiplication and xor methods are overwritten on this class - in this way, adding or multiplying two Ciphertexts classes will perform homomorphic addition, multiplication or xor. Similarly, right multiplication method is overwritten to perform scalar multiplication when multiplying a Ciphertext object with a constant.

The framework’s design considers both computational efficiency and environmental impact, but it is important to note that the implementation presented in this work serves primarily as a demonstration rather than a precise measurement tool. The code measures cryptographic operations’ runtime and applies simplified assumptions (e.g., fixed CPU utilization patterns, base power of 150 W, constant PUE and grid intensity values) to estimate energy consumption and Scope 1–3 emissions. In a real-world data center, actual power usage can fluctuate based on dynamic factors such as server load, cooling requirements, and time-of-day energy mix. Hence, for accurate energy or emission data, one would need to integrate real-time monitoring tools (e.g., Intel RAPL, IPMI, or cloud provider telemetry) and up-to-date information on hardware efficiency, cooling, and local energy grid composition.

Despite these simplifications, the demonstration-based approach still provides insight into how homomorphic encryption algorithms might scale in terms of both resource usage and environmental footprint. As shown in Table ??, certain algorithms—particularly at larger key sizes—require significantly more computational resources. For instance, RSA with a 7680-bit key size demonstrates notably high time consumption in key generation (370.568 seconds), while Damgard-Jurik with the same key size shows substantial encryption and decryption overhead (8.0903 and 8.1464 seconds respectively). These longer runtimes are mapped to estimated energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions using the framework’s model.

Rather than calculating emissions for every algorithm variant, the analysis focuses on low and mid impact cases such as 80-bit and 128-bit resource-intensive homomorphic operations—where environmental considerations are most critical with Colab L4 GPU. Since the comparison with all cpu and gpu types including all data centers that will lead to another research. This targeted assessment investigates how direct on-site emissions (Scope 1), indirect emissions from purchased electricity (Scope 2), and broader lifecycle factors such as hardware manufacturing and cooling systems (Scope 3) scale with computational demand. It is conducted across multiple data centers with varying hardware efficiency (PUE values) and electricity carbon intensities, thereby highlighting how cryptographic security margins intersect with sustainability goals in different operational contexts.

By emphasizing environments where CPU load is highest, this study elucidates the interplay between cryptographic performance and ecological impact. However, all findings should be interpreted as indicative estimates rather than precise measurements. For rigorous emission tracking in an operational data center, one must combine or replace the demonstration model with real-world metrics, such as actual power draw logs and up-to-date carbon intensity data. Within these limitations, the presented framework offers both robust encryption benchmarking and environmental impact estimations, thus enabling more informed decisions about resource allocation and sustainability in cryptographic deployments. Fully Carbon-Based (DC1–DC3): Primarily powered by fossil fuels, leading to high Scope 2 emissions. Fully Renewable (DC4–DC6): Rely on renewable energy sources, resulting in minimal or zero Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, leaving mostly Scope 3 (indirect) emissions. Hybrid (DC7–DC9): Operate on a blend of renewable and non-renewable energy, producing emissions that lie between fully carbon-based and fully renewable centers.

Table 4.

Sample Data Center Configurations

Table 4.

Sample Data Center Configurations

| Data Center |

Type |

Grid Intensity (gCO2/kWh) |

PUE |

Renewable Ratio |

| DC1_Carbon_1 |

Fully Carbon |

600.0 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

| DC2_Carbon_2 |

Fully Carbon |

650.0 |

1.4 |

0.0 |

| DC3_Carbon_3 |

Fully Carbon |

700.0 |

1.5 |

0.0 |

| DC4_Renewable_1 |

Fully Renewable |

100.0 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

| DC5_Renewable_2 |

Fully Renewable |

50.0 |

1.05 |

1.0 |

| DC6_Renewable_3 |

Fully Renewable |

120.0 |

1.2 |

1.0 |

| DC7_Hybrid_1 |

Hybrid |

300.0 |

1.3 |

0.6 |

| DC8_Hybrid_2 |

Hybrid |

280.0 |

1.2 |

0.7 |

| DC9_Hybrid_3 |

Hybrid |

250.0 |

1.2 |

0.8 |

| DC10_Hybrid_4 |

Hybrid |

200.0 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

5. Results and Discussion

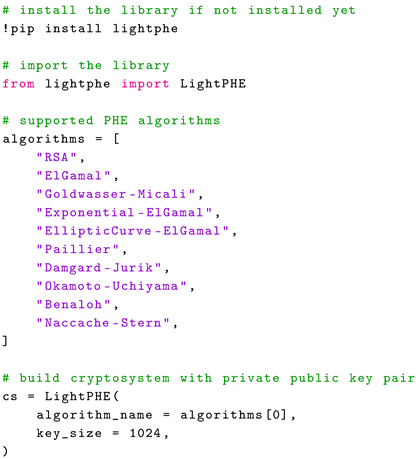

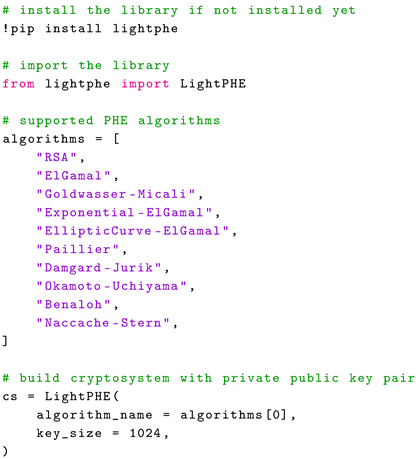

To use the LightPHE framework, the library is imported and the LightPHE class is initialized with the desired partially homomorphic encryption (PHE) algorithm. The following code example demonstrates this process.

In the example shown in Algorithm 1, the LightPHE class is imported from the lightphe library. The algorithms list contains the names of all the supported PHE algorithms. Initializing the LightPHE class with first algorithm in the list, which corresponds to RSA in this case, generates a random private-public key pair for the chosen cryptosystem. This procedure is sufficient to build a cryptosystem using the selected PHE algorithm.

| Algorithm 1: Building a Cryptosystem |

|

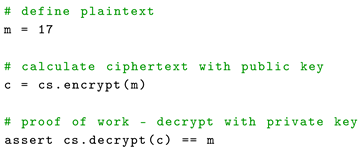

Then, the following code demonstrates defining a plaintext value, encrypting it, and then decrypting it to verify correctness.

In the example shown in Algorithm 2, A plaintext value m is defined and set to 17. The encrypt method of the cryptosystem is called with plaintext, producing the ciphertext c. The decrypt method of cryptosystem is then called with ciphertext as the argument to decrypt the ciphertext. An assertion is made to verify that the decrypted value matches the original plaintext m. This ensures that the encryption and decryption processes are functioning correctly within the cryptosystem.

| Algorithm 2: Encrypt and Decrypt with Built Cryptosystem |

|

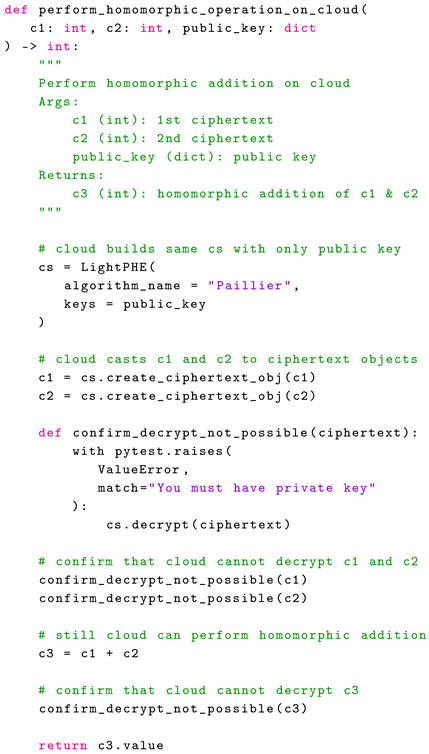

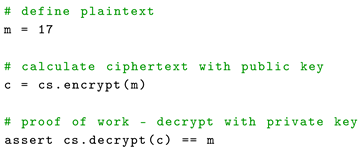

The following code demonstrates homomorphic addition using the Paillier algorithm:

In the example demonstrated in Algorithm 3, the LightPHE class is initialized with the Paillier algorithm. This generates a random private public key pair. Two plaintext values, and , are defined and set to 10000, representing the base salary, and 500, representing the wage increase in amount, respectively. The encrypt method of the LightPHE instance cs is called with and as arguments, producing the ciphertexts and . Encryption can be done with just public keys, without need of private keys. These are done on premises side and , pair and public keys are sent to the cloud environment.

| Algorithm 3: On Premises Encryptions |

|

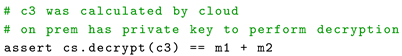

The Algorithm 4 summarizes the operations done in the cloud side. It receives

,

pair and public keys from on premises side. Firsly, cloud cannot decrypt

,

pair because it doesn’t have the private key. Secondly, types of

and

are casted to Ciphertext and LightPHE overwritten that class’ addition method to perform homomorphic addition as mentioned in

Section 4.1. So, homomorphic addition is performed by adding

and

to produce a new ciphertext

, which represents the updated encrypted salary. This operation does not require the private key and can be done with public key only. Even though

was calculated by the cloud system, cloud itself cannot decrypt it because it doesn’t have the private keys. Finally, cloud stores

on its database.

| Algorithm 4: Cloud Calculations |

|

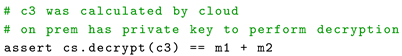

Thereafter, The Algorithm 5 summarizes the proof of work. On premises retrieves from cloud. An assertion is made to verify that decrypting returns the sum of the original plaintext values ( + ) on premises side. Decryption can only be done by the data owner who holds private key. This demonstrates the correctness of the homomorphic addition operation.

| Algorithm 5: Proof of Work |

|

In the example illustrated in Algorithm 6, a scalar k is defined to represent a 5% wage increase and is set to 1.05. The variable is a type of Ciphertext, representing the encrypted base salary of someone, and the class’s right multiplication method is overridden to perform scalar multiplication. Thus, scalar multiplication is performed by multiplying k with the ciphertext to produce a new ciphertext , which represents the encrypted updated salary. This operation does not require the private key and can be done by anyone who has the public keys.

| Algorithm 6: Scalar Multiplication |

|

Finally, an assertion is made to verify that decrypting returns the product of the scalar k and the original plaintext , demonstrating the correctness of the scalar multiplication operation. This operation can only be done by the data owner who holds private key of the cryptosystem.

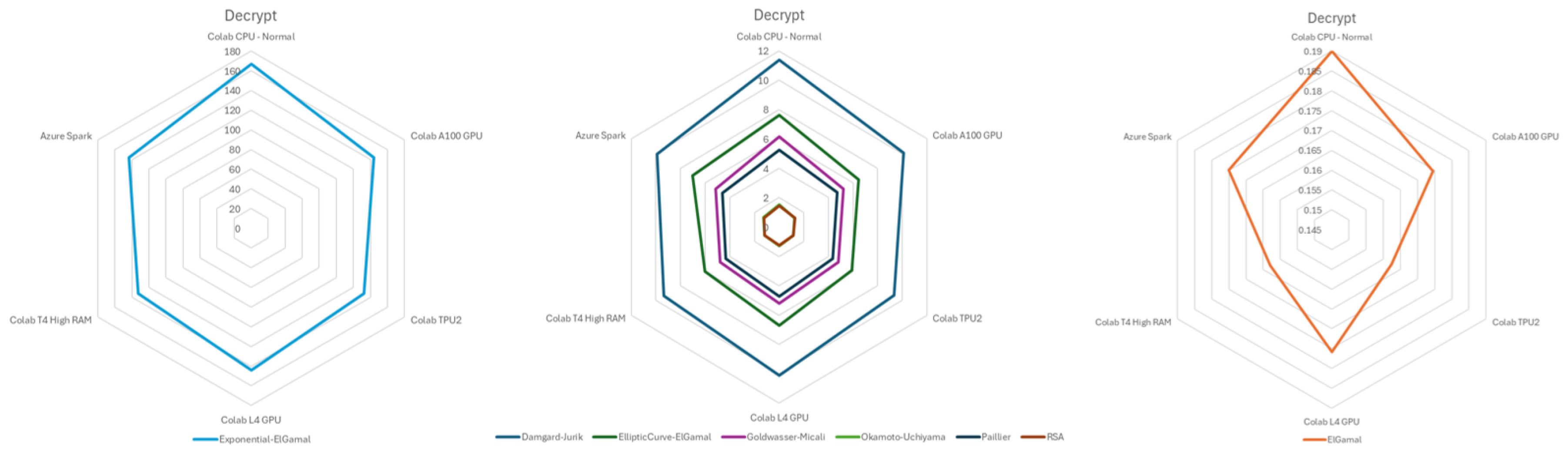

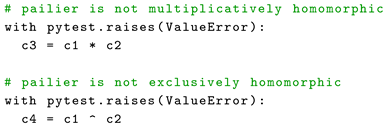

The following code in Algorithm 7 demonstrates the limitations of the Paillier algorithm with respect to multiplicative and exclusive homomorphic operations:

| Algorithm 7: Unsupported Operations |

|

Since the Paillier algorithm is not multiplicatively homomorphic, attempting to multiply ciphertexts and will raise an error with the message "Paillier is not homomorphic with respect to the multiplication". Similarly, since the Paillier algorithm is not exclusively homomorphic, attempting to perform an exclusive OR operation (XOR) on and will raise another error with the message "Paillier is not homomorphic with respect to the exclusive or". These are thrown by the Paillier class’ homomorphic multiply and homomorphic xor methods. These exceptions demonstrate the algorithm’s limitations concerning these specific homomorphic operations.

5.1. Performance

The provided

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9 showcase the performance metrics of various cryptographic algorithms with default configurations, specifically focusing on key generation, encryption, decryption, and homomorphic operations such as addition, multiplication or xor with different key sizes. These measurements are crucial in evaluating the practicality and efficiency of these algorithms in real-world applications. Here, the encryption and homomorphic operation times are represented in scientific notation to illustrate the performance differences clearly. The values in cells represent the times in seconds and are the average of five different experiments.

In these experiments, 18-bit plaintexts were used to simulate realistic annual salary values, typically ranging in the hundreds of thousands. This choice reflects a practical application scenario where the encryption of such values is relevant.

The tables also adhere to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) recommendations for key sizes to achieve specific security levels [

42] as detailed in

Table 5. For an 80-bit symmetric key security level, NIST suggests using 160-bit keys for elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) and 1024-bit keys for other algorithms. For a 112-bit symmetric key security level, 224-bit ECC keys and 2048-bit keys for other algorithms are recommended. For a 128-bit symmetric key security level, NIST recommends 256-bit ECC keys and 3072-bit keys for other algorithms. These guidelines ensure that the cryptographic strength meets the required security standards.

One notable observation from the tables is the significantly higher decryption times for Elliptic Curve ElGamal and Exponential ElGamal algorithms in particular smaller key sizes. This is attributed to the necessity of solving the Discrete Logarithm Problem (DLP) and Elliptic Curve Discrete Logarithm Problem (ECDLP) during the decryption process. This computational complexity renders these cryptosystems more theoretical than practical, especially given the small plaintext values used in the experiments. As the plaintext size increases, the decryption times are expected to rise even further, exacerbating the impracticality.

Interestingly, larger key sizes do not have a significant impact on the encryption and decryption times of Elliptic Curve ElGamal. This consistency across different key sizes highlights a unique aspect of the algorithm’s performance. However, it is important to note that the decryption time for Elliptic Curve ElGamal is still slow when compared to other cryptosystems, making it less practical with today’s computational power for applications requiring frequent decryption at the 80, 112, and 128-bit symmetric key size equivalents. On the other hand, Elliptic Curve ElGamal becomes advantageous at the 192-bit symmetric key size equivalent, as it becomes faster in key generation, encryption, and decryption when compared to other additively homomorphic encryption algorithms such as Paillier or Damgard-Jurik. Additionally, Elliptic Curve ElGamal has potential in the post-quantum era because its equivalents have a much greater impact on key generation, encryption, and decryption. While the times for these operations increase exponentially with key size for other algorithms, the times for EC ElGamal increase linearly.

Additionally, it is important to mention that the Benaloh and Naccache-Stern cryptosystems were excluded from these experiments. Despite functioning correctly for smaller key sizes, these algorithms encountered significant issues during the key generation step for 1024-bit and 2048-bit keys, effectively hanging and becoming non-operational. This limitation prevented their inclusion in the comparative analysis, highlighting the challenges in scaling certain cryptosystems to higher security levels.

Homomorphic operations and encryptions, as noted in the tables, are very fast. This efficiency is crucial as these operations are typically handled frequently, with encryption being performed on-premise and homomorphic operations executed in the cloud. In cloud environments, where performance is a key concern, the swift execution of these tasks ensures optimal system performance. Although decryption is slower than both homomorphic operations and encryption, its less frequent occurrence mitigates the impact of its slower speed. It’s important to note that key generation occurs only once, and while it may be slightly slower, its infrequent occurrence makes this delay negligible in the overall scheme of cryptographic processes.

Overall, these tables provide valuable insights into the performance and practicality of various cryptographic algorithms under different security settings, emphasizing the balance between theoretical capabilities and real-world applicability.

Finally, all experiments were conducted on a machine with an 11th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-11370H CPU running at 3.30 GHz with 8 cores. This CPU model belongs to Intel’s Tiger Lake family and is commonly found in high-performance laptops. Therefore, the information provided about the CPU ensures transparency regarding the computational environment in which the experiments were conducted.

Table 6.

Time Consumption of Algorithms with 80-bit Symmetric Key Size Equivalent in Seconds

Table 6.

Time Consumption of Algorithms with 80-bit Symmetric Key Size Equivalent in Seconds

| Algorithm |

Key Size |

Key Generation |

Encrypt |

Decrypt |

Homomorphic Operation |

| RSA |

1024 |

0.1483 |

|

0.0038 |

|

| ElGamal |

1024 |

0.0177 |

|

0.0007 |

|

| Paillier |

1024 |

0.0507 |

|

0.0120 |

|

| Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

0.0585 |

|

0.0245 |

|

| Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

0.1050 |

|

0.0037 |

|

| Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

0.0400 |

|

0.0093 |

|

| Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

0.0302 |

|

3.1553 |

|

| EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

0.0053 |

|

4.1529 |

|

Table 7.

Time Consumption of Algorithms with 112-bit Symmetric Key Size Equivalent in Seconds

Table 7.

Time Consumption of Algorithms with 112-bit Symmetric Key Size Equivalent in Seconds

| Algorithm |

Key Size |

Key Generation |

Encrypt |

Decrypt |

Homomorphic Operation |

| RSA |

2048 |

1.4959 |

|

0.0235 |

|

| ElGamal |

2048 |

0.6238 |

|

0.0037 |

|

| Paillier |

2048 |

0.7613 |

|

0.0847 |

|

| Damgard-Jurik |

2048 |

0.6388 |

|

0.1997 |

|

| Okamoto-Uchiyama |

2048 |

0.7543 |

|

0.0239 |

|

| Goldwasser-Micali |

2048 |

0.6725 |

|

0.0536 |

|

| Exponential-ElGamal |

2048 |

0.3957 |

|

10.572 |

|

| EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

224 |

0.0060 |

|

3.6356 |

|

Table 8.

Time Consumption of Algorithms with 128-bit Symmetric Key Size Equivalent in Seconds

Table 8.

Time Consumption of Algorithms with 128-bit Symmetric Key Size Equivalent in Seconds

| Algorithm |

Key Size |

Key Generation |

Encrypt |

Decrypt |

Homomorphic Operation |

| RSA |

3072 |

5.8871 |

|

0.1201 |

|

| ElGamal |

3072 |

1.5976 |

|

0.0120 |

|

| Paillier |

3072 |

2.5762 |

|

0.3188 |

|

| Damgard-Jurik |

3072 |

3.0325 |

|

0.6809 |

|

| Okamoto-Uchiyama |

3072 |

2.7635 |

|

0.0881 |

|

| Goldwasser-Micali |

3072 |

3.6569 |

|

0.4216 |

|

| Exponential-ElGamal |

3072 |

1.6232 |

|

23.171 |

|

| EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

256 |

0.0086 |

|

4.3759 |

|

Table 9.

Time Consumption of Algorithms with 192-bit Symmetric Key Size Equivalent in Seconds

Table 9.

Time Consumption of Algorithms with 192-bit Symmetric Key Size Equivalent in Seconds

| Algorithm |

Key Size |

Key Generation |

Encrypt |

Decrypt |

Homomorphic Operation |

| RSA |

7680 |

370.568 |

|

0.9861 |

|

| ElGamal |

7680 |

22.1267 |

|

0.1383 |

|

| Paillier |

7680 |

71.0874 |

|

4.0049 |

|

| Damgard-Jurik |

7680 |

110.567 |

|

8.1464 |

|

| Okamoto-Uchiyama |

7680 |

84.0547 |

|

1.1667 |

|

| Goldwasser-Micali |

7680 |

78.9467 |

|

4.1952 |

|

| Exponential-ElGamal |

7680 |

49.9941 |

|

117.68 |

|

| EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

384 |

0.01000 |

|

3.5553 |

|

5.2. Cloud Performances

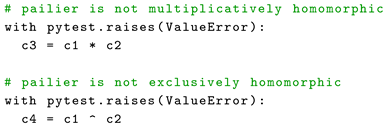

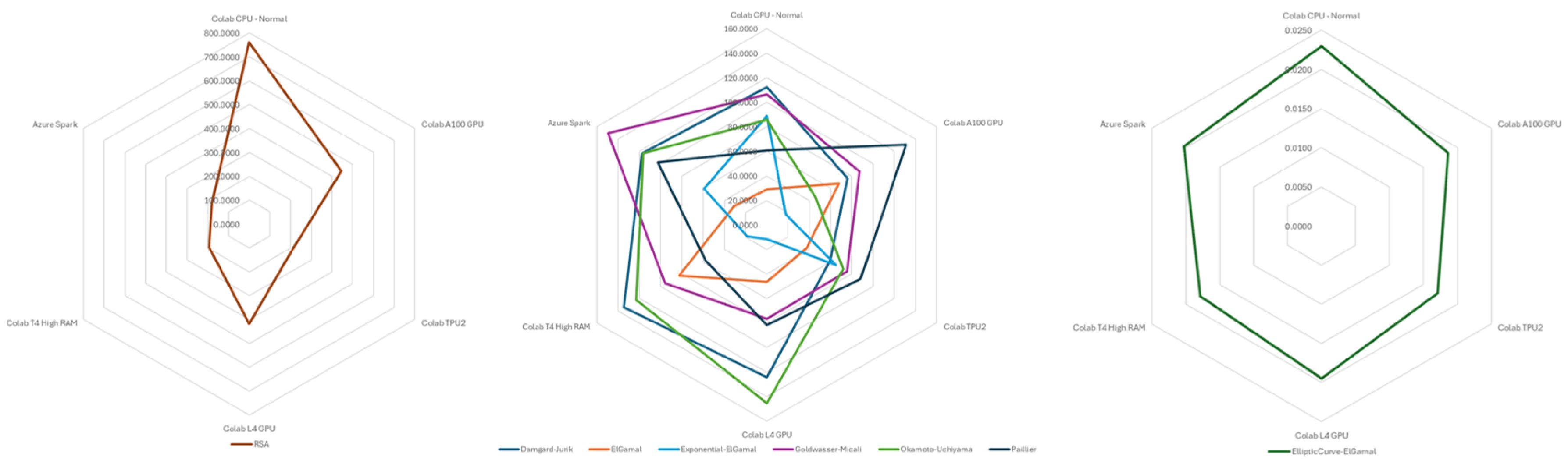

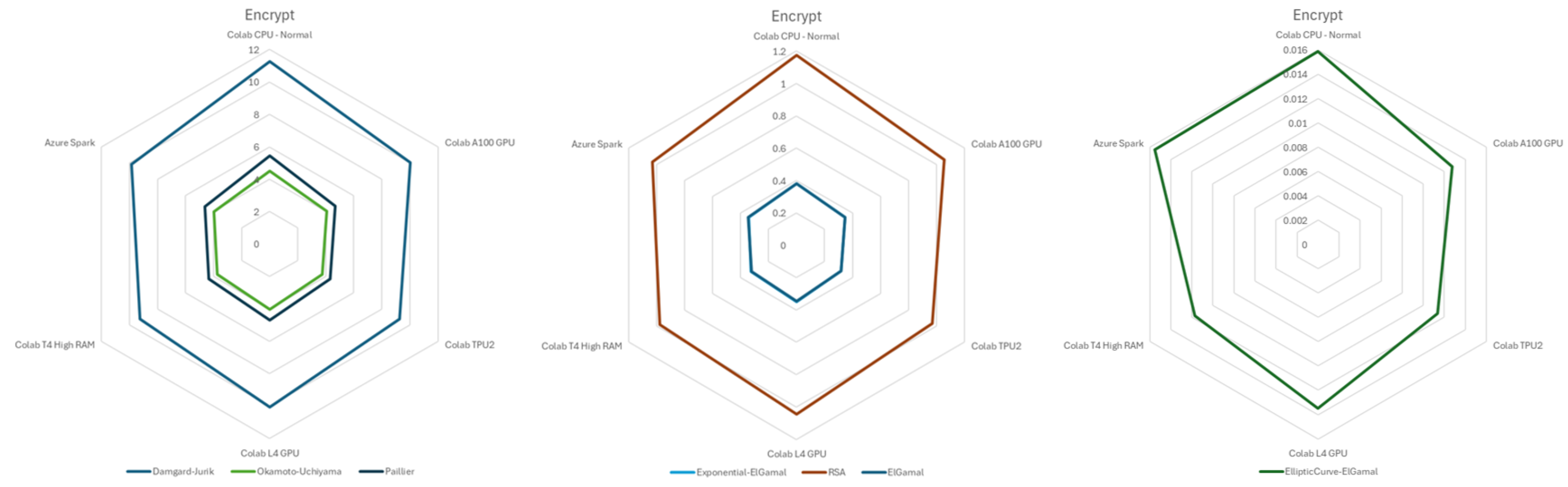

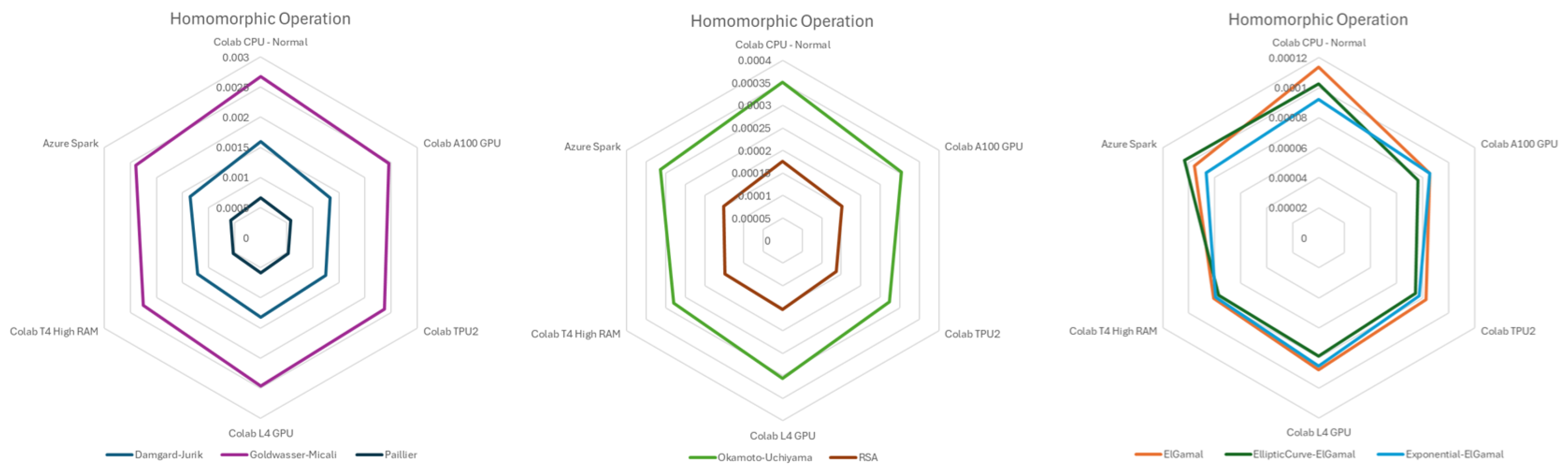

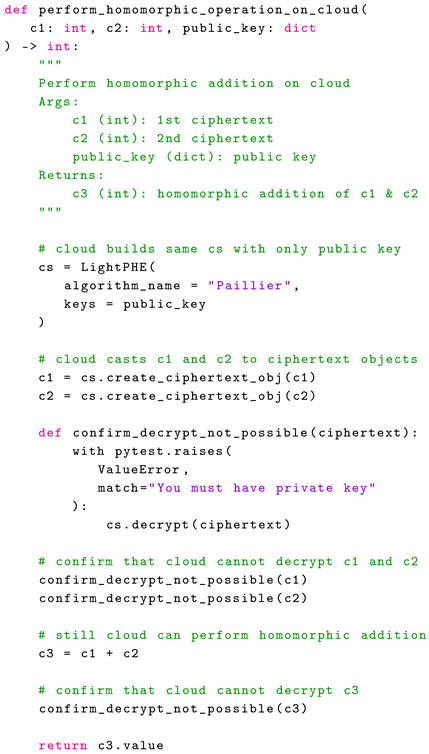

We conducted experiments on key generation, encryption, decryption, and homomorphic operations using various algorithms with an equivalent 192-bit symmetric key size. These experiments were performed across several cloud environments, including Colab Normal, Colab A100 GPU, Colab L4 GPU, Colab T4 High RAM, Colab TPU2, and Azure Spark, running five experiments for each task and averaging the consumption times to ensure accuracy.

We utilize radar map charts to present the performance of various algorithms across diverse cloud environments. Multiple radar maps are shown because consolidating them into a single radar map would render it illegible. Additionally, the radar maps are arranged from left to right to illustrate slower to faster speeds.

Figure 1 illustrates a radar map depicting key generation times in seconds for different algorithms across various cloud environments. Among these algorithms, RSA emerges as the slowest in key generation, with Elliptic Curve ElGamal demonstrating the fastest performance. Following Elliptic Curve ElGamal, ElGamal and Exponential ElGamal exhibit slightly slower key generation times than Elliptic Curve ElGamal. The remaining algorithms exhibit relatively similar performance to each other. Notably, the key generation process exhibits significant instability compared to encryption, decryption, or homomorphic operations. This instability arises from the inherent requirement of generating random values until a specific condition is met, contributing to fluctuating performance levels.

Figure 2 shows the performance comparisons of various algorithms in seconds for encryption tasks across different cloud environments, with values depicted in seconds. Damgard-Jurik, Paillier, and Okamoto-Uchiyama were the slowest performers. ElGamal and Exponential ElGamal charts are overlaid, showcasing moderate performance, with RSA slightly trailing behind in this category. Meanwhile, Elliptic Curve ElGamal emerged as the fastest option.

The decryption performance comparison in seconds, shown in

Figure 3, revealed Exponential ElGamal as the slowest, ElGamal as the fastest, and other algorithms displaying moderate performance across different cloud environments.

Figure 4 highlights the performance of various algorithms in seconds for homomorphic operations across different cloud environments, with values depicted in seconds. Damgard-Jurik, Goldwasser-Micali, and Paillier were the slowest, while ElGamal, Exponential ElGamal, and Elliptic Curve ElGamal exhibited the fastest performance. Okamoto-Uchiyama and RSA demonstrated moderate performance in homomorphic operations. In practice, just homomorphic opetaion will be performed on the cloud environment and just this operation will be done often.

In evaluating the performance of various tasks across different cloud environments, it becomes evident that the Colab Normal environment emerges as the slowest, contrasting sharply with the remarkable speed demonstrated by Colab TPU2 and Colab TPU High RAM, irrespective of the algorithm employed. The performances of various tasks across different cloud environments are summarized in

Table 10.

5.3. Cloud Emission Calculations

For the calculations each cryptographic operation (key generation, encryption, decryption, and homomorphic operation) is timed, and a simplified model is used to estimate its energy consumption and carbon footprint. First, the duration of the operation (

) is combined with a fixed CPU utilization factor (

) that is set for each type of operation (e.g., 95%, 85%, etc.). Next, the server’s base power consumption (

) is used to compute the approximate energy consumption (

) in kWh, as follows:

This quantity is then multiplied by the data center’s

Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) to account for additional overheads, such as cooling and power distribution. Hence,

Because a fraction of the power may be from renewable sources, the model uses

to distinguish between renewable and non-renewable energy consumption. The non-renewable portion (

) is assigned a CO

2 intensity (

, in gCO

2/kWh) to estimate

Scope 2 (purchased electricity) emissions. A small fraction of these non-renewable emissions is assumed to come from backup generators (

), which constitutes

Scope 1. Finally, the model adds

Scope 3 emissions by multiplying the total energy by 0.35, representing life-cycle impacts of hardware, cooling systems, and other indirect factors:

Summing these yields . Such a model serves as a demonstration rather than an accurate reflection of real-world data-center measurements, since all parameters (PUE, grid intensity, CPU usage patterns) are fixed and not derived from live monitoring. Nevertheless, it provides a comparative view of how varying cryptographic operations and key sizes might drive differences in energy consumption and resulting emissions. As mentioned 80-bit and 128-bit calculations made with Colab L4 GPU, otherwise results will be too complex to visualize and represent with those dimensions. The data encompasses multiple data centers categorized as fully carbon-based (DC1-DC3), fully renewable (DC4-DC6), and hybrid (DC7-DC9), executing operations such as key generation (KG), encryption (E), decryption (D), and homomorphic operations (H) for algorithms including RSA, ElGamal, Paillier, Damgard-Jurik, Okamoto-Uchiyama, Goldwasser-Micali, Exponential-ElGamal, and EllipticCurve-ElGamal. Key sizes analyzed are 1024-bit and 160-bit for the 80-bit security level, and 3072-bit and 256-bit for the 128-bit security level, reflecting equivalent security strengths based on computational complexity.

The obtained results underscore the significant influence of data center energy sources on the carbon footprint of cryptographic operations. Fully renewable data centers (DC4–DC6) exhibit markedly lower carbon emissions due to effectively zero Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, leaving only Scope 3 (indirect) emissions—primarily from hardware manufacturing and supply chains.For example, RSA key generation at 1024-bit in DC4 produced only 0.15 gCO2, a reduction of approximately 98% when compared to 9.83 gCO2 in the fossil fuel-powered DC1. Fully carbon-based data centers (DC1–DC3), on the other hand, recorded the highest emissions, predominantly driven by Scope 2. This is best illustrated by RSA 3072-bit key generation in DC1, which emitted 400.29 gCO2 in total, 285.92 gCO2 of which can be attributed to electricity sourced from fossil fuels. Hybrid data centers (DC7–DC9) demonstrated emission levels that fell between these extremes. Specifically, RSA 1024-bit key generation in DC7 emitted 2.55 gCO2, significantly below DC1 but considerably above DC4.

In comparing the energy intensity of different cryptographic tasks, key generation emerged as the most resource-intensive for most algorithms, such as RSA, ElGamal, and Paillier. For instance, RSA 1024-bit key generation in DC1 required 0.0117 kWh (9.83 gCO2), whereas encryption and decryption consumed only 0.000186 kWh (0.16 gCO2) and 0.000209 kWh (0.18 gCO2), respectively. Notable exceptions included Exponential-ElGamal and EllipticCurve-ElGamal, where decryption proved more energy-intensive due to the complexity of homomorphic properties and discrete logarithm-based computations. A prime example is Exponential-ElGamal at 1024-bit, for which the decryption phase in DC1 consumed 0.21183 kWh (177.94 gCO2)—over 260 times that of its own key generation.

Regarding algorithmic efficiency, elliptic curve-based methods stood out for their reduced energy consumption during key generation and encryption. For instance, EllipticCurve-ElGamal at 160-bit in DC1 consumed only 0.000388 kWh (0.33 gCO2) for key generation, noticeably lower than RSA 1024-bit’s 0.0117 kWh. However, decryption costs remained high for these elliptic curve algorithms at larger key sizes: EllipticCurve-ElGamal at 256-bit required 0.271057 kWh (227.69 gCO2) in DC1, contrasting sharply with 0.004277 kWh (3.59 gCO2) for RSA 3072-bit decryption. Additionally, scaling security levels from 80-bit to 128-bit produced substantial jumps in both energy usage and emissions. RSA key generation, for instance, increased from 0.0117 kWh (9.83 gCO2) at 1024-bit in DC1 to 0.47653 kWh (400.29 gCO2) at 3072-bit—approximately a 40-fold rise. Similarly, Exponential-ElGamal decryption escalated sixfold, reaching 1.28965 kWh (1083.31 gCO2) at 3072-bit.

Finally, even among data centers sharing the same primary energy source, operational and hardware variations influenced efficiency. An example is RSA 1024-bit key generation in DC2 (carbon-based), which was more efficient at 0.007571 kWh (6.89 gCO2) than the 0.0117 kWh (9.83 gCO2) measured in DC1. These findings collectively highlight the critical role of energy sourcing, algorithm selection, and hardware optimizations in determining the overall carbon footprint and energy consumption of cryptographic processes.

Table 11.

Cloud Emission Calculations 80-bit

Table 11.

Cloud Emission Calculations 80-bit

| Data Center Name |

Algorithm |

Key Size |

Operation |

Duration (s) |

Energy(kWh) |

Scope 1 (gCO2) |

Scope 2 (gCO2) |

Scope 3 (gCO2) |

Total (gCO2) |

| DC1 |

RSA |

1024 |

KG |

0.2274 |

0.0117 |

0.35 |

7.02 |

2.46 |

9.83 |

| DC1 |

RSA |

1024 |

E |

0.004 |

0.000186 |

0.01 |

0.11 |

0.04 |

0.16 |

| DC1 |

RSA |

1024 |

D |

0.0045 |

0.000209 |

0.01 |

0.13 |

0.04 |

0.18 |

| DC1 |

RSA |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC1 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.0275 |

0.001417 |

0.04 |

0.85 |

0.3 |

1.19 |

| DC1 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0015 |

0.000071 |

0 |

0.04 |

0.01 |

0.06 |

| DC1 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

0.0009 |

0.00004 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.03 |

| DC1 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC1 |

Paillier |

1024 |

KG |

0.0439 |

0.002259 |

0.07 |

1.36 |

0.47 |

1.9 |

| DC1 |

Paillier |

1024 |

E |

0.0149 |

0.000686 |

0.02 |

0.41 |

0.14 |

0.58 |

| DC1 |

Paillier |

1024 |

D |

0.0151 |

0.000695 |

0.02 |

0.42 |

0.15 |

0.58 |

| DC1 |

Paillier |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC1 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

KG |

0.0654 |

0.003365 |

0.1 |

2.02 |

0.71 |

2.83 |

| DC1 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

E |

0.0314 |

0.001445 |

0.04 |

0.87 |

0.3 |

1.21 |

| DC1 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

D |

0.0315 |

0.001452 |

0.04 |

0.87 |

0.3 |

1.22 |

| DC1 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000002 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC1 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

KG |

0.076 |

0.003909 |

0.12 |

2.35 |

0.82 |

3.28 |

| DC1 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

E |

0.0139 |

0.000641 |

0.02 |

0.38 |

0.13 |

0.54 |

| DC1 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

D |

0.0047 |

0.000218 |

0.01 |

0.13 |

0.05 |

0.18 |

| DC1 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC1 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

KG |

0.1013 |

0.005211 |

0.16 |

3.13 |

1.09 |

4.38 |

| DC1 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

E |

0.0004 |

0.00002 |

0 |

0.01 |

0 |

0.02 |

| DC1 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

D |

0.0228 |

0.001052 |

0.03 |

0.63 |

0.22 |

0.88 |

| DC1 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

H |

0.0001 |

0.000003 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC1 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.0158 |

0.000811 |

0.02 |

0.49 |

0.17 |

0.68 |

| DC1 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0016 |

0.000074 |

0 |

0.04 |

0.02 |

0.06 |

| DC1 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

4.6008 |

0.21183 |

6.35 |

127.1 |

44.48 |

177.94 |

| DC1 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC1 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

KG |

0.0075 |

0.000388 |

0.01 |

0.23 |

0.08 |

0.33 |

| DC1 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

E |

0.0132 |

0.000609 |

0.02 |

0.37 |

0.13 |

0.51 |

| DC1 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

D |

6.0519 |

0.27864 |

8.36 |

167.18 |

58.51 |

234.06 |

| DC1 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

H |

0.0001 |

0.000003 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC2 |

RSA |

1024 |

KG |

0.1366 |

0.007571 |

0.25 |

4.92 |

1.72 |

6.89 |

| DC2 |

RSA |

1024 |

E |

0.004 |

0.000199 |

0.01 |

0.13 |

0.05 |

0.18 |

| DC2 |

RSA |

1024 |

D |

0.0045 |

0.000224 |

0.01 |

0.15 |

0.05 |

0.2 |

| DC2 |

RSA |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC2 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.0322 |

0.001783 |

0.06 |

1.16 |

0.41 |

1.62 |

| DC2 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0015 |

0.000076 |

0 |

0.05 |

0.02 |

0.07 |

| DC2 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

0.0009 |

0.000043 |

0 |

0.03 |

0.01 |

0.04 |

| DC2 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC2 |

Paillier |

1024 |

KG |

0.0798 |

0.004423 |

0.14 |

2.88 |

1.01 |

4.03 |

| DC2 |

Paillier |

1024 |

E |

0.0153 |

0.000758 |

0.02 |

0.49 |

0.17 |

0.69 |

| DC2 |

Paillier |

1024 |

D |

0.0153 |

0.000759 |

0.02 |

0.49 |

0.17 |

0.69 |

| DC2 |

Paillier |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC2 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

KG |

0.054 |

0.002993 |

0.1 |

1.95 |

0.68 |

2.72 |

| DC2 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

E |

0.0313 |

0.00155 |

0.05 |

1.01 |

0.35 |

1.41 |

| DC2 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

D |

0.0315 |

0.001562 |

0.05 |

1.02 |

0.36 |

1.42 |

| DC2 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000002 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC2 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

KG |

0.0765 |

0.004239 |

0.14 |

2.76 |

0.96 |

3.86 |

| DC2 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

E |

0.0137 |

0.000678 |

0.02 |

0.44 |

0.15 |

0.62 |

| DC2 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

D |

0.0046 |

0.000229 |

0.01 |

0.15 |

0.05 |

0.21 |

| DC2 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC2 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

KG |

0.1009 |

0.005594 |

0.18 |

3.64 |

1.27 |

5.09 |

| DC2 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

E |

0.0004 |

0.00002 |

0 |

0.01 |

0 |

0.02 |

| DC2 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

D |

0.0236 |

0.00117 |

0.04 |

0.76 |

0.27 |

1.06 |

| DC2 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

H |

0.0001 |

0.000003 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC2 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.0323 |

0.001792 |

0.06 |

1.16 |

0.41 |

1.63 |

| DC2 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0016 |

0.000079 |

0 |

0.05 |

0.02 |

0.07 |

| DC2 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

4.5871 |

0.227444 |

7.39 |

147.84 |

51.74 |

206.97 |

| DC2 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC2 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

KG |

0.0071 |

0.000395 |

0.01 |

0.26 |

0.09 |

0.36 |

| DC2 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

E |

0.0118 |

0.000585 |

0.02 |

0.38 |

0.13 |

0.53 |

| DC2 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

D |

6.0367 |

0.299318 |

9.73 |

194.56 |

68.09 |

272.38 |

| DC2 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

H |

0.0001 |

0.000003 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC3 |

RSA |

1024 |

KG |

0.1787 |

0.010608 |

0.37 |

7.43 |

2.6 |

10.4 |

| DC3 |

RSA |

1024 |

E |

0.004 |

0.000213 |

0.01 |

0.15 |

0.05 |

0.21 |

| DC3 |

RSA |

1024 |

D |

0.0045 |

0.000241 |

0.01 |

0.17 |

0.06 |

0.24 |

| DC3 |

RSA |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC3 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.0177 |

0.001049 |

0.04 |

0.73 |

0.26 |

1.03 |

| DC3 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0015 |

0.000081 |

0 |

0.06 |

0.02 |

0.08 |

| DC3 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

0.0009 |

0.000047 |

0 |

0.03 |

0.01 |

0.05 |

| DC3 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC3 |

Paillier |

1024 |

KG |

0.0313 |

0.00186 |

0.07 |

1.3 |

0.46 |

1.82 |

| DC3 |

Paillier |

1024 |

E |

0.0152 |

0.000808 |

0.03 |

0.57 |

0.2 |

0.79 |

| DC3 |

Paillier |

1024 |

D |

0.0152 |

0.000806 |

0.03 |

0.56 |

0.2 |

0.79 |

| DC3 |

Paillier |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC3 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

KG |

0.055 |

0.003268 |

0.11 |

2.29 |

0.8 |

3.2 |

| DC3 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

E |

0.0316 |

0.001679 |

0.06 |

1.18 |

0.41 |

1.65 |

| DC3 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

D |

0.0317 |

0.001686 |

0.06 |

1.18 |

0.41 |

1.65 |

| DC3 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000002 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC3 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

KG |

0.0985 |

0.005846 |

0.2 |

4.09 |

1.43 |

5.73 |

| DC3 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

E |

0.0137 |

0.000727 |

0.03 |

0.51 |

0.18 |

0.71 |

| DC3 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

D |

0.0046 |

0.000245 |

0.01 |

0.17 |

0.06 |

0.24 |

| DC3 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC3 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

KG |

0.0679 |

0.00403 |

0.14 |

2.82 |

0.99 |

3.95 |

| DC3 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

E |

0.0005 |

0.000028 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.03 |

| DC3 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

D |

0.0233 |

0.001239 |

0.04 |

0.87 |

0.3 |

1.21 |

| DC3 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

H |

0.0001 |

0.000003 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC3 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.0347 |

0.002061 |

0.07 |

1.44 |

0.51 |

2.02 |

| DC3 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0016 |

0.000086 |

0 |

0.06 |

0.02 |

0.08 |

| DC3 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

4.6527 |

0.247173 |

8.65 |

173.02 |

60.56 |

242.23 |

| DC3 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC3 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

KG |

0.007 |

0.000417 |

0.01 |

0.29 |

0.1 |

0.41 |

| DC3 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

E |

0.0117 |

0.000624 |

0.02 |

0.44 |

0.15 |

0.61 |

| DC3 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

D |

5.9809 |

0.317737 |

11.12 |

222.42 |

77.85 |

311.38 |

| DC3 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

H |

0.0001 |

0.000003 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC4 |

RSA |

1024 |

KG |

0.0996 |

0.004336 |

0 |

0 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

| DC4 |

RSA |

1024 |

E |

0.0041 |

0.000159 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| DC4 |

RSA |

1024 |

D |

0.0046 |

0.000178 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| DC4 |

RSA |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC4 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.0464 |

0.002021 |

0 |

0 |

0.07 |

0.07 |

| DC4 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0016 |

0.000062 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC4 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

0.0009 |

0.000034 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC4 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC4 |

Paillier |

1024 |

KG |

0.0755 |

0.003289 |

0 |

0 |

0.12 |

0.12 |

| DC4 |

Paillier |

1024 |

E |

0.0151 |

0.000588 |

0 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

| DC4 |

Paillier |

1024 |

D |

0.0152 |

0.000592 |

0 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

| DC4 |

Paillier |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC4 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

KG |

0.0629 |

0.002738 |

0 |

0 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

| DC4 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

E |

0.0317 |

0.001234 |

0 |

0 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

| DC4 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

D |

0.0317 |

0.001237 |

0 |

0 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

| DC4 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC4 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

KG |

0.0762 |

0.00332 |

0 |

0 |

0.12 |

0.12 |

| DC4 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

E |

0.0139 |

0.000541 |

0 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

| DC4 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

D |

0.0046 |

0.00018 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| DC4 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC4 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

KG |

0.086 |

0.003746 |

0 |

0 |

0.13 |

0.13 |

| DC4 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

E |

0.0004 |

0.000017 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC4 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

D |

0.024 |

0.000937 |

0 |

0 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

| DC4 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

H |

0.0001 |

0.000003 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC4 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.0267 |

0.001162 |

0 |

0 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

| DC4 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0017 |

0.000065 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC4 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

4.6526 |

0.181258 |

0 |

0 |

6.34 |

6.34 |

| DC4 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC4 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

KG |

0.0071 |

0.000309 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| DC4 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

E |

0.0122 |

0.000476 |

0 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

| DC4 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

D |

5.9941 |

0.233522 |

0 |

0 |

8.17 |

8.17 |

| DC4 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

H |

0.0001 |

0.000002 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

RSA |

1024 |

KG |

0.1244 |

0.00517 |

0 |

0 |

0.09 |

0.09 |

| DC5 |

RSA |

1024 |

E |

0.004 |

0.000149 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

RSA |

1024 |

D |

0.0045 |

0.000169 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

RSA |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.0266 |

0.001107 |

0 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

| DC5 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0016 |

0.000058 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

0.0009 |

0.000033 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

Paillier |

1024 |

KG |

0.061 |

0.002535 |

0 |

0 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

| DC5 |

Paillier |

1024 |

E |

0.0153 |

0.000571 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| DC5 |

Paillier |

1024 |

D |

0.0154 |

0.000573 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| DC5 |

Paillier |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

KG |

0.0601 |

0.002498 |

0 |

0 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

| DC5 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

E |

0.0315 |

0.001171 |

0 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

| DC5 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

D |

0.0316 |

0.001174 |

0 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

| DC5 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

KG |

0.0841 |

0.003495 |

0 |

0 |

0.06 |

0.06 |

| DC5 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

E |

0.0136 |

0.000507 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| DC5 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

D |

0.0047 |

0.000173 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

KG |

0.0559 |

0.002322 |

0 |

0 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

| DC5 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

E |

0.0004 |

0.000016 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

D |

0.0233 |

0.000868 |

0 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

| DC5 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

H |

0.0001 |

0.000002 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.0451 |

0.001874 |

0 |

0 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

| DC5 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0016 |

0.000058 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

4.5495 |

0.169185 |

0 |

0 |

2.96 |

2.96 |

| DC5 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC5 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

KG |

0.0075 |

0.000311 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| DC5 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

E |

0.0117 |

0.000435 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| DC5 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

D |

5.9192 |

0.220121 |

0 |

0 |

3.85 |

3.85 |

| DC5 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

H |

0.0001 |

0.000002 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC6 |

RSA |

1024 |

KG |

0.1165 |

0.005535 |

0 |

0 |

0.23 |

0.23 |

| DC6 |

RSA |

1024 |

E |

0.0041 |

0.000173 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| DC6 |

RSA |

1024 |

D |

0.0046 |

0.000194 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| DC6 |

RSA |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC6 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.0459 |

0.002178 |

0 |

0 |

0.09 |

0.09 |

| DC6 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0015 |

0.000065 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC6 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

0.0008 |

0.000036 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC6 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC6 |

Paillier |

1024 |

KG |

0.0728 |

0.003459 |

0 |

0 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

| DC6 |

Paillier |

1024 |

E |

0.015 |

0.000639 |

0 |

0 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

| DC6 |

Paillier |

1024 |

D |

0.0151 |

0.000642 |

0 |

0 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

| DC6 |

Paillier |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC6 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

KG |

0.0891 |

0.004231 |

0 |

0 |

0.18 |

0.18 |

| DC6 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

E |

0.0317 |

0.001349 |

0 |

0 |

0.06 |

0.06 |

| DC6 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

D |

0.0316 |

0.001342 |

0 |

0 |

0.06 |

0.06 |

| DC6 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC6 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

KG |

0.1032 |

0.004902 |

0 |

0 |

0.21 |

0.21 |

| DC6 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

E |

0.0139 |

0.00059 |

0 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

| DC6 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

D |

0.0047 |

0.000201 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| DC6 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC6 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

KG |

0.089 |

0.004226 |

0 |

0 |

0.18 |

0.18 |

| DC6 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

E |

0.0004 |

0.000018 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC6 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

D |

0.0229 |

0.000972 |

0 |

0 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

| DC6 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

H |

0.0001 |

0.000003 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC6 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.044 |

0.002091 |

0 |

0 |

0.09 |

0.09 |

| DC6 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0015 |

0.000063 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC6 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

4.4484 |

0.189058 |

0 |

0 |

7.94 |

7.94 |

| DC6 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC6 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

KG |

0.0074 |

0.000351 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| DC6 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

E |

0.0119 |

0.000504 |

0 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

| DC6 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

D |

5.8188 |

0.247301 |

0 |

0 |

10.39 |

10.39 |

| DC6 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

H |

0.0001 |

0.000003 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC7 |

RSA |

1024 |

KG |

0.2148 |

0.011051 |

0.07 |

1.33 |

1.16 |

2.55 |

| DC7 |

RSA |

1024 |

E |

0.004 |

0.000186 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.04 |

| DC7 |

RSA |

1024 |

D |

0.0046 |

0.00021 |

0 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

| DC7 |

RSA |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC7 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.0535 |

0.002751 |

0.02 |

0.33 |

0.29 |

0.64 |

| DC7 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0015 |

0.000071 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.02 |

| DC7 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

0.0008 |

0.000039 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

| DC7 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC7 |

Paillier |

1024 |

KG |

0.0936 |

0.004818 |

0.03 |

0.58 |

0.51 |

1.11 |

| DC7 |

Paillier |

1024 |

E |

0.0152 |

0.000698 |

0 |

0.08 |

0.07 |

0.16 |

| DC7 |

Paillier |

1024 |

D |

0.0152 |

0.000702 |

0 |

0.08 |

0.07 |

0.16 |

| DC7 |

Paillier |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC7 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

KG |

0.0598 |

0.003079 |

0.02 |

0.37 |

0.32 |

0.71 |

| DC7 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

E |

0.0312 |

0.001437 |

0.01 |

0.17 |

0.15 |

0.33 |

| DC7 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

D |

0.0314 |

0.001446 |

0.01 |

0.17 |

0.15 |

0.33 |

| DC7 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000002 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC7 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

KG |

0.112 |

0.005763 |

0.03 |

0.69 |

0.61 |

1.33 |

| DC7 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

E |

0.0139 |

0.00064 |

0 |

0.08 |

0.07 |

0.15 |

| DC7 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

D |

0.0047 |

0.000215 |

0 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

| DC7 |

Okamoto-Uchiyama |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC7 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

KG |

0.0985 |

0.00507 |

0.03 |

0.61 |

0.53 |

1.17 |

| DC7 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

E |

0.0004 |

0.000019 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC7 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

D |

0.0234 |

0.001079 |

0.01 |

0.13 |

0.11 |

0.25 |

| DC7 |

Goldwasser-Micali |

1024 |

H |

0.0001 |

0.000003 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC7 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.0726 |

0.003735 |

0.02 |

0.45 |

0.39 |

0.86 |

| DC7 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0016 |

0.000073 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.02 |

| DC7 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

4.5853 |

0.211113 |

1.27 |

25.33 |

22.17 |

48.77 |

| DC7 |

Exponential-ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC7 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

KG |

0.0072 |

0.000372 |

0 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

0.09 |

| DC7 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

E |

0.0119 |

0.000547 |

0 |

0.07 |

0.06 |

0.13 |

| DC7 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

D |

5.893 |

0.271324 |

1.63 |

32.56 |

28.49 |

62.68 |

| DC7 |

EllipticCurve-ElGamal |

160 |

H |

0.0001 |

0.000003 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC8 |

RSA |

1024 |

KG |

0.3302 |

0.015684 |

0.07 |

1.32 |

1.54 |

2.92 |

| DC8 |

RSA |

1024 |

E |

0.0041 |

0.000175 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

| DC8 |

RSA |

1024 |

D |

0.0046 |

0.000196 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.04 |

| DC8 |

RSA |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC8 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

KG |

0.0425 |

0.002021 |

0.01 |

0.17 |

0.2 |

0.38 |

| DC8 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

E |

0.0016 |

0.000066 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| DC8 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

D |

0.0009 |

0.000037 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

| DC8 |

ElGamal |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC8 |

Paillier |

1024 |

KG |

0.0767 |

0.003641 |

0.02 |

0.31 |

0.36 |

0.68 |

| DC8 |

Paillier |

1024 |

E |

0.0151 |

0.000642 |

0 |

0.05 |

0.06 |

0.12 |

| DC8 |

Paillier |

1024 |

D |

0.0152 |

0.000647 |

0 |

0.05 |

0.06 |

0.12 |

| DC8 |

Paillier |

1024 |

H |

0 |

0.000001 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| DC8 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

KG |

0.0915 |

0.004345 |

0.02 |

0.37 |

0.43 |

0.81 |

| DC8 |

Damgard-Jurik |

1024 |

E |

0.0311 |

0.001324 |