Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

21 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Are There Rules for Defining Race in Biology?

1.2. The Relevant Biological Concepts

1.3. Population Structure

“In principle, a low global FST would not preclude a small number of intelligence- related genes of major effect that differed in frequency between socially defined races, but in practice, no such genes have been found.”

2. Conflating Ancestry with Race

Local Adaptation

3. Making Biological Sense of Race

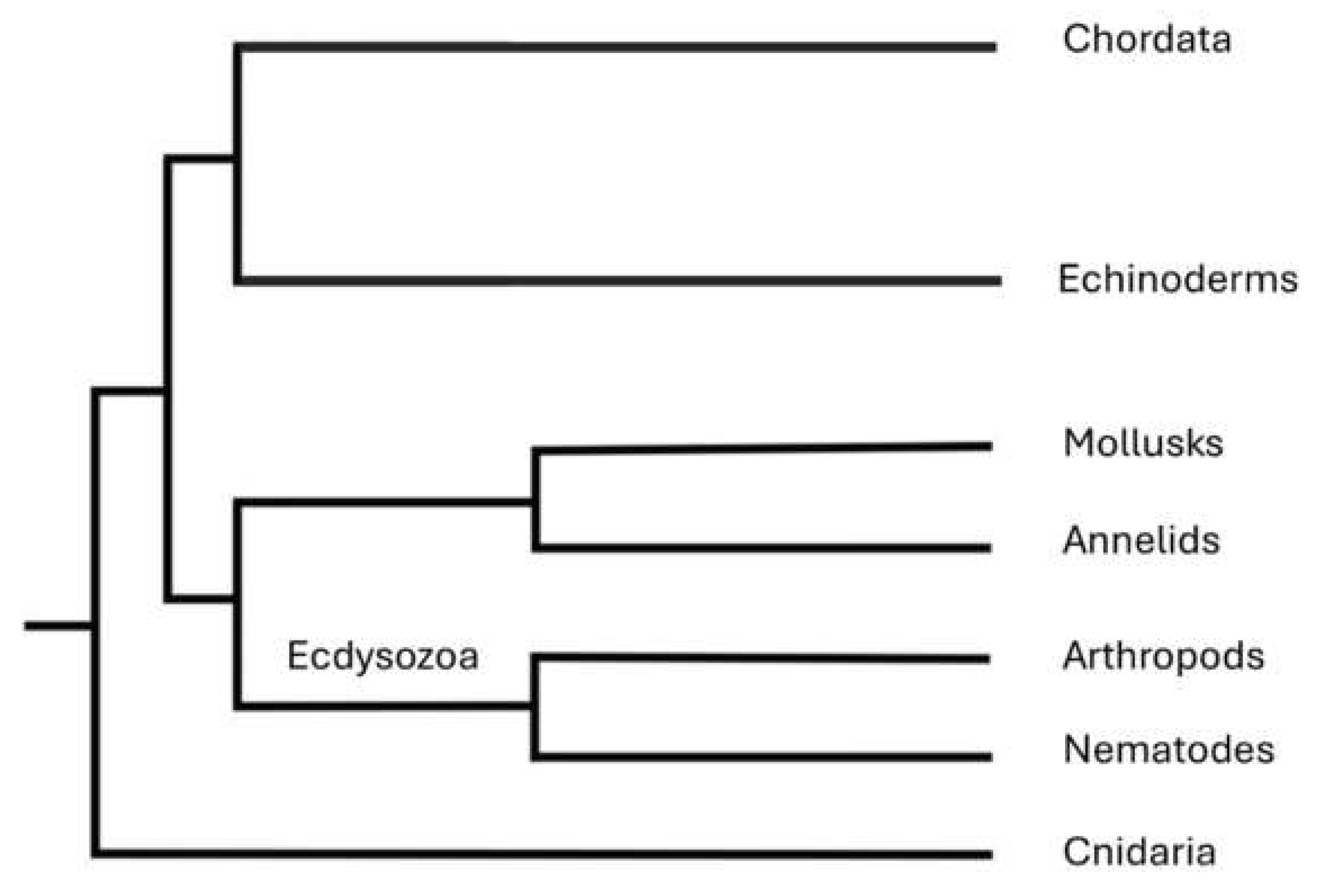

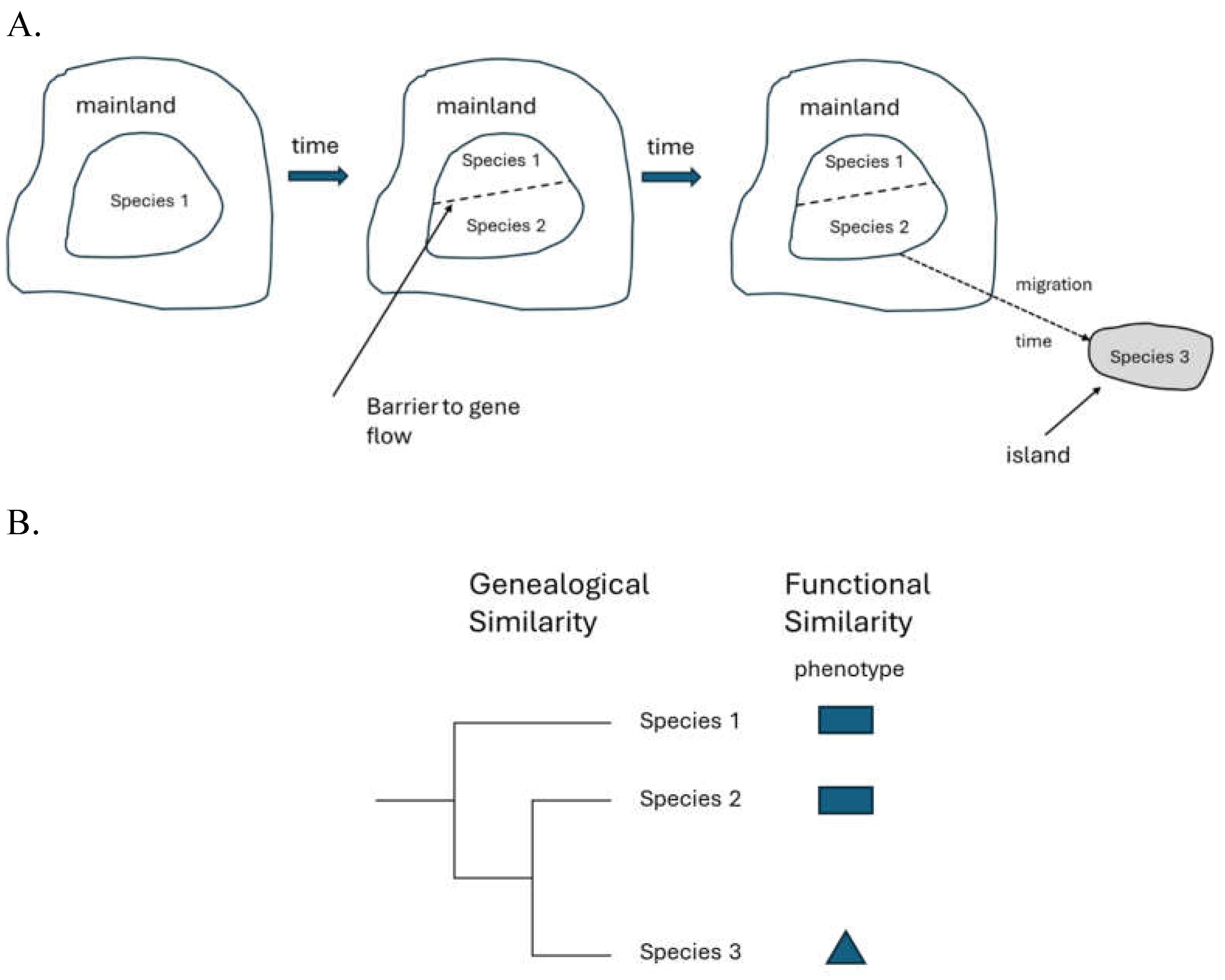

3.1. A Basic Introduction to Evolutionary Trees

3.2. Stasis and Convergence

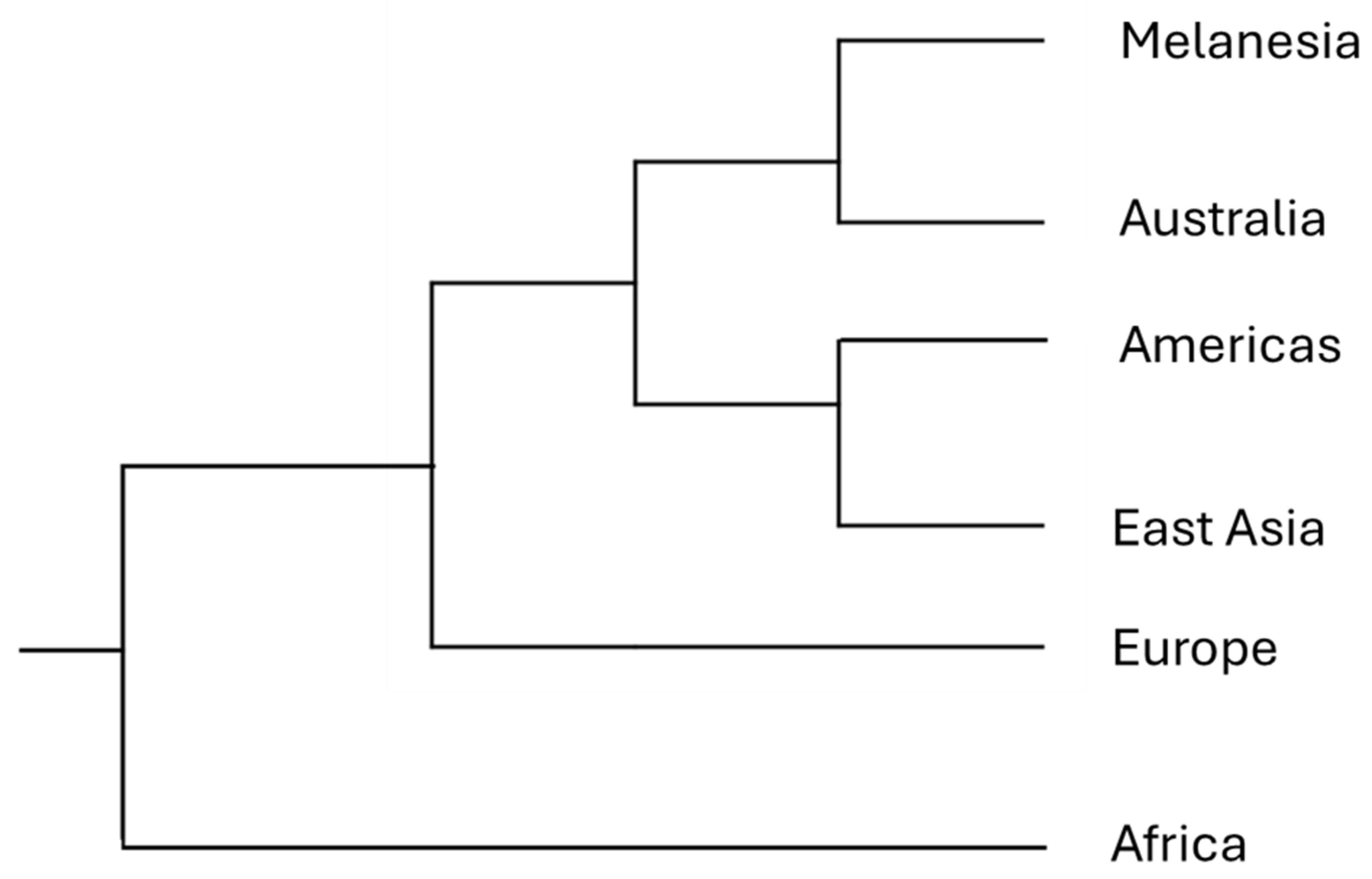

4. Human Races from an Ecotypic Perspective

5. Scientific Racism

Race Is Both a Social and Biological Construct

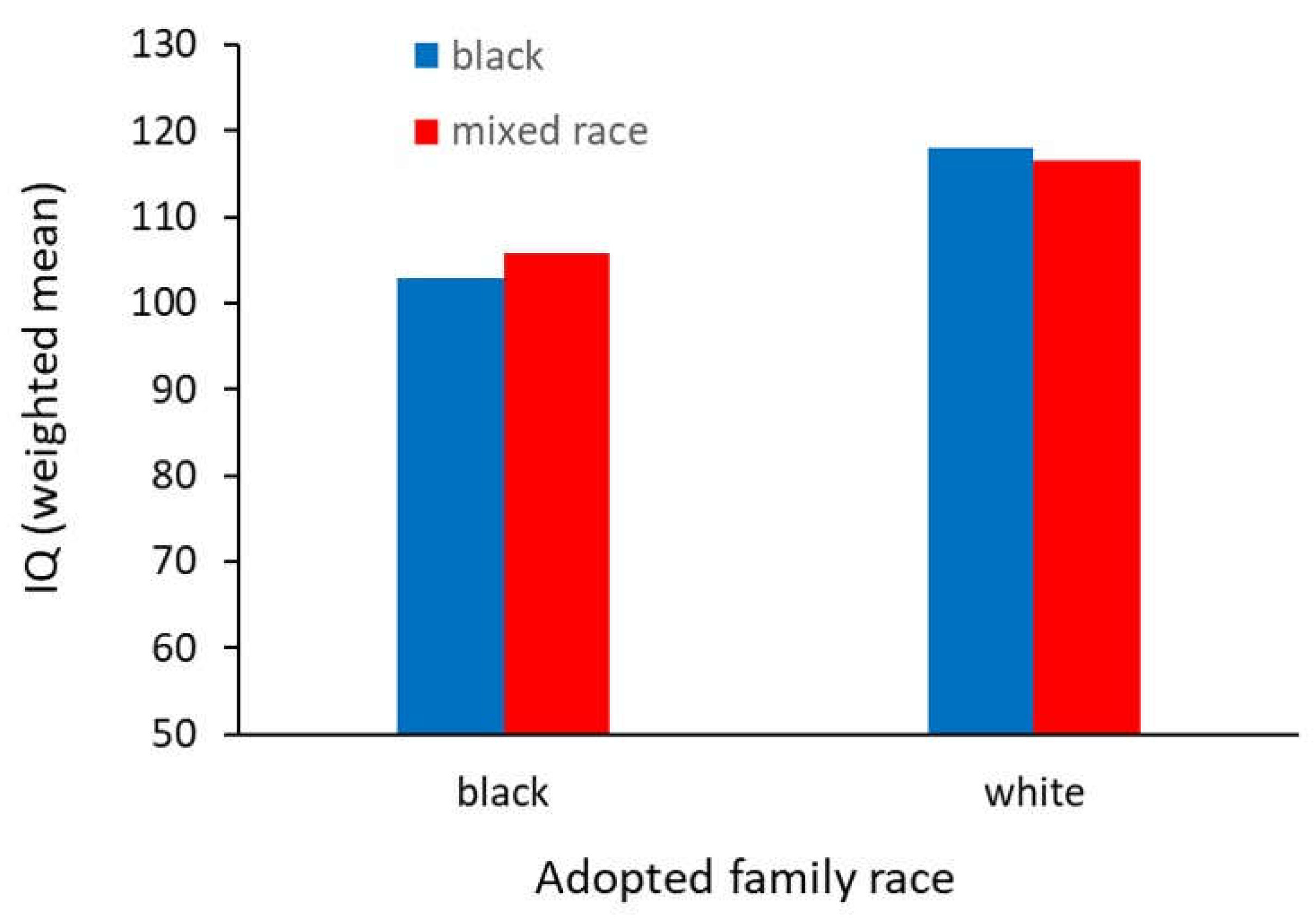

6. The Bell Curve

7. Conclusions

- If an alien arrived and treated human beings the way we scientifically treat every other animal species, they would almost certainly identify many ecotypes. “Ecotype” seems the correct expression for human races, given that our differences relate to local adaptation and are few in number. Subspecies, the other possible term, seems better suited to cases of genome-wide differentiation, which is weak across human populations.

- Attempts to show that races do not exist because population structure does not map onto folk races, i.e. black, white, Asian are without merit for two reasons. First, they commit the continuum fallacy in that race is fundamentally about biological variation within our species. How we carve the variation up, or if we choose to do so at all, does not affect the existence of the variation. Proving that variation does not matter requires phenotypic experiments, not exploration of population structure. Second, with respect to structure, scientific racists could not care less about how race is defined. They do not care about the number of races, what they are called, whether they are based on large scale genomic differentiation, or on a few mutations. All they care about is whether functional differences exist for traits like intelligence. Hence, studies of genome-wide human population structure are strawman arguments with respect to both race and scientific racism.

- Given that we do not know the genetic basis of intelligence (even in gross approximation), the only data that can address beliefs in racial superiority for this trait are phenotypic in nature. The relevant data suggests no difference whatsoever in the phenotypes, meaning genetics studies looking for differences are without merit. In short, genetic studies that claim to inform us on this topic are of little value no matter their political agenda.

- Ideologically driven attempts to show that races do not exist, although well intentioned, erode the public’s confidence in the objectivity of scientists when it comes to this contentious issue. These attempts have thus ironically strengthened the position of scientific racists.

| 1 | It seems to be a convention in evolutionary biology, which I will not follow because I think it is historically inaccurate, to forgive Darwin all his discussion of the inferiority of so called “savage races,” by which he meant all nonwhites. Darwin also expressed belief in the idea that the so-called lesser races will eventually face extinction in the face of competition from what he called the higher races of Western Europe. His belief in such ideas, and especially his unwavering support for the even worse bigotry of his cousin Galton, gave immense scientific credibility to scientific racism. |

| 2 | Bryan also cared about the theological issues. I focus here on the neglected part of this history. |

| 3 | Crick’s views can be found in his correspondence which is available online. E. O. Wilson’s support was also made clear in his personal correspondence, which was published after his death. |

| 4 | I prefer to call it pseudoscientific racism, which I think better captures what it is. I will cover this later in this paper. |

| 5 | Lewontin was a great scientist who radically expanded our understanding of evolution. Unfortunately, this is not as appreciated, even in science, as it should be because he was more prone to mixing ideology and science than any other foundational figure in biology and this has hurt his legacy. |

| 6 | This is conjecture, of course; the authors I discuss here do not admit this. |

| 7 | I do not know of a study that quantifies this claim, but whether it is true or not, the main point would stand, which is that many, and probably most, species do not have races. |

| 8 | “Type” can refer to race, subspecies population, or ecotype depending on the whim of the author. |

| 9 | This is to say that the idea that the races are fundamentally different, that is, strongly different across the entire genome cannot be true. Rather, if there are differences, they must relate to particular, traits. In other words, race must be skin deep. The problem with this perspective is that racists do in fact think race is skin deep, they just want to substitute the trait skin with intelligence or character. |

| 10 | It would probably have to be variation in the expression levels, or timing or place of expression, of one or more genes, or some combination of alleles, but the argument is the same whether the genetic basis is simple or complex. |

| 11 | I say in principle because shared ancestry can correlate with functional differences, but they are separate concepts. In other words, if all humans were limited to one region, Europe, for example, and no concept of race even existed we would still be able to do all the 23andme type analyses to identify people’s ancestry by their country of origin. |

| 12 | Clearly the racist notion of Irish inferiority, popular in the past, was socially constructed and we will return to this topic later when we discuss the social and biological construction of race. |

| 13 | When there is a barrier to gene flow (of variable force) between two populations and their habitats differ, then both genome wide population structure and stronger variation in the traits related to the selection are both predicted to occur. |

| 14 | The number of races, and their places of origin, is a classic lumper splitter problem that will never be resolved to everyone’s satisfaction. We clearly have many more tropical ecotypes, but a dispassionate biologist looking at human variation would likely hypothesize that we have many ecotypes in both the tropics and in the temperate zone. Founder effects, sexual selection and other forces in addition to natural selection probably add further complexity to our patterns of variation. |

| 15 | This is certainly true at the phenotypic level but at the genetic level it maybe true for some loci but not others. Even in cases where the genetic basis for a shared trait is different, however, it does not change the fact that from a functional perspective there is strong similarity, or even identical function. |

| 16 | Needless to say, I am giving a simple example to illustrate a general point, while ignoring much that goes into the design and interpretation of such studies. |

| 17 | Depending on the goals of the study we may or may not break up the three ecotypes into more groups. |

| 18 | The black children were adopted at an older age, and into poorer homes than the white children, making the inference that their IQs were lower due to genetic reasons unsound. |

| 19 | This study found a strong environmental effect suggesting white household are superior to black ones when it comes to providing a place where students can excel in school. This result likely led to this work also being ignored by the left as it neither supports the genetic argument for low black achievement, nor the popular idea that poor black achievement is caused by systemic racism. |

| 20 | They invariably ignore Native Americans, as their low scores, and close ancestry with Asians, cannot be made to fit their narrative. |

| 21 | I only compare scientific racism and creationism in the sense that both are pseudoscientific. Other than this, they could not be more different. I am not one of the many evolutionary biologists with a dim view of religion. I am not a believer, but I think religion does a lot of people good. |

| 22 | Medieval superstitious beliefs about handedness or hair color fall into this category. |

| 23 | Something like this is happening now as the age at which one becomes an adult seems to drift higher and higher. College students are called ‘kids” and the category “teenager” seems to be dissolving away as people in this clear developmental class are referred to as children, something that would have shocked people a century ago. I do not argue, or course, that this is a bad thing; the rise in standard of living has allowed us to make these social changes, which are generally a good thing. These examples simply illustrate that good biological reasons to have clear categories can be be ignored if society sees fit to do so. |

References

- Amemiya, J.; Sodré, D.; Heyman, G.D. Early developmental insights into the social construction of race. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 2024, 153, 3062–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, P.; Stobdan, T.; Zhou, D.; Hartley, I.; Akbari, A.; Bafna, V.; Haddad, G.G. High-altitude adaptation in humans: From genomics to integrative physiology. Journal of Molecular Medicine 2017, 95, 1269–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamshad, M.; Wooding, S.; Salisbury, B.A.; Stephens, J.C. Deconstructing the relationship between genetics and race. Nature reviews genetics 2004, 5, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickford, D.; Lohman, D.J.; Sodhi, N.S.; Ng, P.K.; Meier, R.; Winker, K.; Ingram, K.K.; Das, I. Cryptic species as a window on diversity and conservation. Trends in ecology & evolution 2007, 22, 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- Bigham, A.W.; Lee, F.S. Human high-altitude adaptation: Forward genetics meets the HIF pathway. Genes & development 2014, 28, 2189–2204. [Google Scholar]

- Blanquart, F.; Kaltz, O.; Nuismer, S.L.; Gandon, S. A practical guide to measuring local adaptation. Ecology letters 2013, 16, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolnick, D.A.; Fullwiley, D.; Duster, T.; Cooper, R.S.; Fujimura, J.H.; Kahn, J.; Kaufman, J.S.; Marks, J.; Morning, A.; Nelson, A.; Ossorio, P. The science and business of genetic ancestry testing. Science 2007, 318, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borevitz, J.O.; Chory, J. Genomics tools for QTL analysis and gene discovery. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2004, 7, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, S. G.; Schultz, T. R.; Fisher, B. L.; Ward, P. S. Evaluating alternative hypotheses for the early evolution and diversification of ants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 18172–18177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brothers, D.J. Aculeate Hymenoptera: Phylogeny and classification. In Encyclopedia of Social Insects; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, B.E.; Jordan, A.; Clark, U.S. Race as a social construct in psychiatry research and practice. JAMA psychiatry 2022, 79, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbrink, F.T.; Crother, B.I.; Murray, C.M.; Smith, B.T.; Ruane, S.; Myers, E.A.; Pyron, R.A. Empirical and philosophical problems with the subspecies rank. Ecology and Evolution 2022, 12, e9069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardinal, S.; Danforth, B. N. The Antiquity of Bees Is Derived from Extant Diversity and Resurrected Fossils. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 13118–13121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carl, N. How stifling debate around race, genes and IQ can do harm. Evolutionary Psychological Science 2018, 4, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, Z.; Pan, Q.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Guo, H.; Liu, S.; Lu, H.; Tian, S.; Li, R.; Shi, W. Genomic analyses reveal demographic history and temperate adaptation of the newly discovered honey bee subspecies Apis mellifera sinisxinyuan n. ssp. Molecular biology and evolution 2016, 33, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, R.; Hendren, N.; Jones, M.R.; Porter, S.R. Race and economic opportunity in the United States: An intergenerational perspective. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 2020, 135, 711–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claeys, G. The" survival of the fittest" and the origins of social darwinism. Journal of the History of Ideas 2000, 61, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, G.; Hardy, J.; Harpending, H. Natural history of Ashkenazi intelligence. Journal of Biosocial Science 2006, 38, 659–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corliss, J.O. On lumpers and splitters of higher taxa in ciliate systematics. Transactions of the American Microscopical Society 1976, 95, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C.; Darwin C. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection; Murray: London, 1859. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, C. The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex (Vol. 2). D. Appleton. 1872. [Google Scholar]

- De Queiroz, K. Species concepts and species delimitation. Systematic biology 2007, 56, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, W.T.; Flynn, J.R. Black Americans reduce the racial IQ gap - Evidence from standardization samples. Psychological Science 2006, 17, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duello, T.M.; Rivedal, S.; Wickland, A.; Weller, A. Race and genetics versus “race” in genetics: A systematic review of the use of African ancestry in genetic studies. Evol. Med. Public Health 2021, 9, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A. W. F. Human genetic diversity: Lewontin’s fallacy. BioEssays 2003, 25, 798–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldredge, N.; Gould, S.J. in Models in Paleobiology, ed Schopf TJM (Freeman, San Francisco), pp 82–115. 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Eldredge, N.; Thompson, J.N.; Brakefield, P.M.; Gavrilets, S.; Jablonski, D.; Jackson, J.B.; Lenski, R.E.; Lieberman, B.S.; McPeek, M.A.; Miller, W. The dynamics of evolutionary stasis. Paleobiology 2005, 31, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endersby, J. Lumpers and splitters: Darwin, Hooker, and the search for order. science 2009, 326, 1496–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. M., May (Ed.) Natural Selection in the Wild; Princeton Univ: Princeton.

- Engelhard, G.H.; Ellis, J.R.; Payne, M.R.; Hofstede, R. Ter; Pinnegar, J.K. Ecotypes as a concept for exploring responses to climate change in fish assemblages. ICES Journal of Marine Science 2011, 68, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan J.F., Holland; R. Equal opportunity and racial differences in IQ. Intelligence 2002, 30, 361–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, J.F.; Holland, C.R. Racial equality in intelligence: Predictions from a theory of intelligence as processing. Intelligence 2007, 35, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, D.S.; Mackay, T.F. Introduction to quantitative genetics; Longman Press: London, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.; Hansen, M.E.; Lo, Y.; Tishkoff, S.A. Going global by adapting local: A review of recent human adaptation. Science 2016, 354, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, Y.; Boyle, E.A.; Telis, N.; Gao, Z.; Gaulton, K.J.; Golan, D.; Yengo, L.; Rocheleau, G.; Froguel, P.; McCarthy, M.I.; Pritchard, J.K. Detection of human adaptation during the past 2000 years. Science 2016, 354, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, M.; Moltke, I.; Grarup, N.; Racimo, F.; Bjerregaard, P.; Jørgensen, M.E.; Korneliussen, T.S.; Gerbault, P.; Skotte, L.; Linneberg, A.; Christensen, C. Greenlandic Inuit show genetic signatures of diet and climate adaptation. Science 2015, 349, 1343–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galton, F. Hereditary genius. D. Appleton. 1891. [Google Scholar]

- Galton, F. Eugenics: Its definition, scope, and aims. American Journal of Sociology 1904, 10, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, L.S. Mainstream science on intelligence: An editorial with 52 signatories, history, and bibliography (Reprinted from The Wall Street Journal, 1994). Intelligence 1997, 24, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.J. The Mismeasure of Man. WW Norton & Company. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, J.L. The emperor's new clothes: Biological theories of race at the millennium. Rutgers University Press. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, J. The race myth: Why we pretend race exists in America. Penguin. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gregor, J.W. The ecotype. Biological Reviews 1944, 19, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haier, H. No Voice at Vox: Sense and nonsense about discussing IQ and Race. Quilette, https://quillette.com/2017/06/11/no-voice-vox-sense-nonsense-discussing-iq-race/. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hailer, F.; Leonard, J.A. Hybridization among three native North American Canis species in a region of natural sympatry. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, R.M. The bell curve. CONTEMPORARY SOCIOLOGY-A JOURNAL OF REVIEWS 1995, 24, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapeman, P.; Smith, L.M. Genetics, geography, and subspecies status of American mink in Florida, with an emphasis on Neogale vison evergladensis. Systematics and Biodiversity 2024, 22, 2330371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J.J. Lessons from the bell curve. Journal of Political Economy 1995, 103, 1091–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrnstein, R.; Murray, C. The bell curve. Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life, New York. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Sánchez, E.; Jin, X.; Asan, Bianba; Z, Peter; B.M, Vinckenbosch; N, Liang; Y.U, Yi; X, He; M., Somel; P., Ni. Altitude adaptation in Tibetans caused by introgression of Denisovan-like DNA. Nature 2014, 512, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huxley, J.S. Eugenics and society. The Eugenics Review 1936, 28, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyasov, R.A.; Lee, M.L.; Takahashi, J.I.; Kwon, H.W.; Nikolenko, A.G. A revision of subspecies structure of western honey bee Apis mellifera. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2020, 27, 3615–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, N.G. The evolution of human skin and skin color. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2004, 33, 585–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A. How much can we boost IQ and scholastic achieve ment? Harvard Educational Review 1969, 39, 1–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.; Rienzo, A. Di. Adaptations to local environments in modern human populations. Current opinion in genetics & development 2014, 29, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B. Race, Genes, Evolution, and IQ: The Key Datasets and Arguments. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörger, K.M.; Schrödl, M. How to describe a cryptic species? Practical challenges of molecular taxonomy. Frontiers in zoology 2013, 10, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.M. ‘Race’: What biology can tell us about a social construct. eLS, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kawecki, T.J.; Ebert, D. Conceptual issues in local adaptation. Ecology letters 2004, 7, 1225–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korte, A.; Farlow, A. The advantages and limitations of trait analysis with GWAS: A review. Plant methods 2013, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krohn, A.R.; Apodaca, J.J.; Collins, L.; Hudson, B.D.; Barrett, K. Phylogenetics, subspecies, and conservation of the eastern pinesnake. The Journal of Wildlife Management 2024, 88, e22599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, K.N.; Feldman, M.W. Genes, culture, and scientific racism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121, e2322874121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lande, R.; Arnold, S. J. The measurement of selection on correlated characters. Evolution 1983, 37, 1210–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levins, R.; Lewontin, R. The dialectical biologist. Harvard University Press. 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin, R.C. Race and intelligence. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 1970, 26, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewontin, R. The Triple Helix: Gene, Organism, and Environment. Harvard University Press. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin, R.C. Dobzhansky, T., Hecht, MK, Steere, WC, Eds.; The apportionment of human diversity. In Evolutionary biology; Appleton-Century-Crofts: New York, 1972; Volume 6, pp. 381–398. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.Z.; Absher, D.M.; Tang, H.; Southwick, A.M.; Casto, A.M.; Ramachandran, S.; Cann, H.M.; Barsh, G.S.; Feldman, M.; Cavalli-Sforza, L.L.; Myers, R.M. Worldwide human relationships inferred from genome-wide patterns of variation. science 2008, 319, 1100–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, R.; Vanhanen, T.; Stuart, M. IQ and the wealth of nations. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Macholdt, E.; Lede, V.; Barbieri, C.; Mpoloka, S.W.; Chen, H.; Slatkin, M.; Pakendorf, B.; Stoneking, M. Tracing pastoralist migrations to southern Africa with lactase persistence alleles. Current Biology 2014, 24, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallet, J. Subspecies, semispecies, superspecies. Encyclopedia of biodiversity 2007, 5, 523–526. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr, E. Systematics and the origin of species; Columbia Univer sity Press: New York, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr, E. Of what use are subspecies? The Auk 1982, 99, 593–595. [Google Scholar]

- Meirmans, P.G.; Hedrick, P.W. Assessing population structure: FST and related measures. Molecular ecology resources 2011, 11, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meixner, M.D.; Leta, M.A.; Koeniger, N.; Fuchs, S. The honey bees of Ethiopia represent a new subspecies of Apis mellifera—Apis mellifera simensis n. ssp. Apidologie 2011, 42, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.; Schuster, S.C.; Welch, A.J.; Ratan, A.; Bedoya-Reina, O.C.; Zhao, F.; Kim, H.L.; Burhans, R.C.; Drautz, D.I.; Wittekindt, N.E.; Tomsho, L.P. Polar and brown bear genomes reveal ancient admixture and demographic footprints of past climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, E2382–E2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, J.; Parejo, M.; Nielsen, R.O.; Langa, J.; Montes, I.; Papoutsis, L.; Farajzadeh, L.; Bendixen, C.; Căuia, E.; Charrière, J.D.; Coffey, M.F. Authoritative subspecies diagnosis tool for European honey bees based on ancestry informative SNPs. BMC genomics 2021, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondol, S.; Moltke, I.; Hart, J.; Keigwin, M.; Brown, L.; Stephens, M.; Wasser, S.K. New evidence for hybrid zones of forest and savanna elephants in Central and West Africa. Molecular Ecology 2015, 24, 6134–6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.G.J. Family socialization and the IQ test performance of traditionally and transracially adopted black children. Developmental Psychology 1986, 22, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbett, R.E. The Achievement Gap: Past, Present & Future. Daedalus 2011, 140, 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett, R.E,. J. Aronson; Blair, C.; Dickens, W.; Flynn, J.; Halpern, D.F.; Turkheimer, E. Group Differences in IQ Are Best Understood as Environmental in Origin. The American Psychologist 2012, 67, 503–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novembre, J. The background and legacy of Lewontin's apportionment of human genetic diversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2022, 377, 20200406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obach, B.K. Demonstrating the social construction of race. Teaching Sociology 1999, 27, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleksa, A.; Tofilski, A. Wing geometric morphometrics and microsatellite analysis provide similar discrimination of honey bee subspecies. Apidologie 2015, 46, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omi, M; Winant, H. Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Omi, M.; Winant, H. Racial formation rules. Racial formation in the twenty-first century, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemberton, T.J.; DeGiorgio, M.; Rosenberg, N.A. Population structure in a comprehensive genomic data set on human microsatellite variation. G, 8: Genomes, Genetics 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Phillimore, A.B.; Owens, I.P. Are subspecies useful in evolutionary and conservation biology? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2006, 273, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, J.L. Pierce, J.L., 2014, March. Why teaching about race as a social construct still matters. In Sociological Forum (Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 259–264). Wiley, Springer.

- Pigliucci, M.; Kaplan, J. On the concept of biological race and its applicability to humans. Philosophy of Science 2003a, 70, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigliucci, M.; Kaplan, J. Making Sense of Evolution: The Conceptual Foundations of Evolutionary Biology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 2003b. [Google Scholar]

- Pinker, S. Groups and Genes. New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/77727/groups-and-genes. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pongracz, J.D.; Paetkau, D.; Branigan, M.; Richardson, E. Recent hybridization between a polar bear and grizzly bears in the Canadian Arctic. Arctic 2017, 70, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, J.S.; Castellano, S.; Andrés, A.M. The genomics of human local adaptation. Trends in Genetics 2020, 36, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindermann, H.; Becker, D.; Coyle, T.R. Survey of Expert Opinion on Intelligence: Causes of International Differences in Cognitive Ability Tests. Frontiers in Psychology 2016, 7, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J. The evolutionary history of human skin pigmentation. Journal of molecular evolution 2020, 88, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, J.A. Darwinism and social Darwinism. Journal of the History of Ideas 1972, 33, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, N.A. A population-genetic perspective on the similarities and differences among worldwide human populations. Human biology 2011, 83, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, N.A.; Pritchard, J.K.; Weber, J.L.; Cann, H.M.; Kidd, K.K.; Zhivotovsky, L.A.; Feldman, M.W. Genetic structure of human populations. science 2002, 298, 2381–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, N.A.; Mahajan, S.; Ramachandran, S.; Zhao, C.; Pritchard, J.K.; Feldman, M.W. Clines, clusters, and the effect of study design on the inference of human population structure. PLoS genetics 2005, 1, e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, N.A.; Edge, M.D.; Pritchard, J.K.; Feldman, M.W. Interpreting polygenic scores, polygenic adaptation, and human phenotypic differences. Evolution, medicine, and public health 2019, 2019, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rushton, J.P.; Jensen, A.R. Thirty years of research on race differences in cognitive ability. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 2005, 11, 235–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeti, P.C.; Varilly, P.; Fry, B.; Lohmueller, J.; Hostetter, E.; Cotsapas, C.; Xie, X.; Byrne, E.H.; McCarroll, S.A.; Gaudet, R.; Schaffner, S.F. Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations. Nature 2007, 449, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savolainen, O.; Lascoux, M.; Merilä, J. Ecological genomics of local adaptation. Nature Reviews Genetics 2013, 14, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarr, S.; Weinberg, R.A. IQ test performance of black children adopted by white families. American Psychologist 1976, 31, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlebusch, C.M.; Gattepaille, L.M.; Engström, K.; Vahter, M.; Jakobsson, M.; Broberg, K. Human adaptation to arsenic-rich environments. Molecular biology and evolution 2015, 32, 1544–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ségurel, L.; Bon, C. On the evolution of lactase persistence in humans. Annual review of genomics and human genetics 2017, 18, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selden, S. Eugenics and the social construction of merit, race and disability. Journal of Curriculum Studies 2000, 32, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.I. On Watson, Racism, and Standardized Tests. Marshall Journal of Medicine 2019, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, W.S.; Meixner, M.D. Apis mellifera pomonella, a new honey bee subspecies from Central Asia. Apidologie 2003, 34, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Feldman, M.W. Diversity and its causes: Lewontin on racism, biological determinism and the adaptationist programme. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2022, 377, 20200417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, N.R.; Vidya, T.N.C. To split or not to split: The case of the African elephant. Current Science (00113891) 2011, 100, 810. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, H. Social Statics: Or, The Conditions Essential to Human Happiness Specified, and the First of Them Developed. D. Appleton. 1866. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, D.L. The genetic causes of convergent evolution. Nature Reviews Genetics 2013, 14, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.J. For whom the bell curve tolls: A review of The Bell Curve. Psychological Science 1995, 6, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, R.D. Wither the subspecies? An ecological perspective on taxonomic, environmental and sexual determinants of phenotypic variation in big-eared woolly bats, Chrotopterus auritus. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 2023, 139, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, A. R. Biological races in humans. Stud. Hist. Philos. Biol. Biomed. Sci. 2013, 44, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, D. Racial IQ Differences among Transracial Adoptees: Fact or Artifact? Journal of Intelligence 2016, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tontonoz, M.J. The Scopes Trial Revisited: Social Darwinism versus Social Gospel. Science as Culture 2008, 17, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, A.; Gandhi, J. The evolution of human skin color. JAMA dermatology 2017, 153, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turesson, G. ‘The Genotypical Response of the Plant Species to the Habitat. Hereditas 1922, 3, 211–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, R.A.; Scarr, S.; Waldman, I.D. The Minnesota transracial adoption study – a follow up of test performance at adolescence. Intelligence 1992, 16, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, B.S.; Cockerham, C.C. Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution 1984, 38, 1358–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O.; Brown, W.L. The subspecies concept and its taxonomic application. Systematic zoology 1953, 2, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S. The statistical consequences of Mendelian heredity in relation to speciation. Pages 161–183 in The new systematics (J. Huxley, ed.). Oxford University Press, London. 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, S. The genetical structure of populations. Annals of eugenics 1949, 15, 323–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Liang, Y.; Huerta-Sanchez, E.; Jin, X.; Cuo, Z.X.P.; Pool, J.E.; Xu, X.; Jiang, H.; Vinckenbosch, N.; Korneliussen, T.S.; Zheng, H. Sequencing of 50 human exomes reveals adaptation to high altitude. science 2010, 329, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Connecticut | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | 2017 |

| white | 253 | 253 | 249 | 249 |

| black | 220 | 219 | 218 | 222 |

| Hispanic | 222 | 224 | 224 | 223 |

| Massachusetts | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | 2017 |

| white | 258 | 260 | 256 | 255 |

| black | 235 | 230 | 230 | 229 |

| Hispanic | 236 | 234 | 232 | 234 |

| New York | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | 2017 |

| white | 245 | 248 | 245 | 244 |

| black | 224 | 225 | 221 | 224 |

| Hispanic | 226 | 229 | 228 | 223 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).