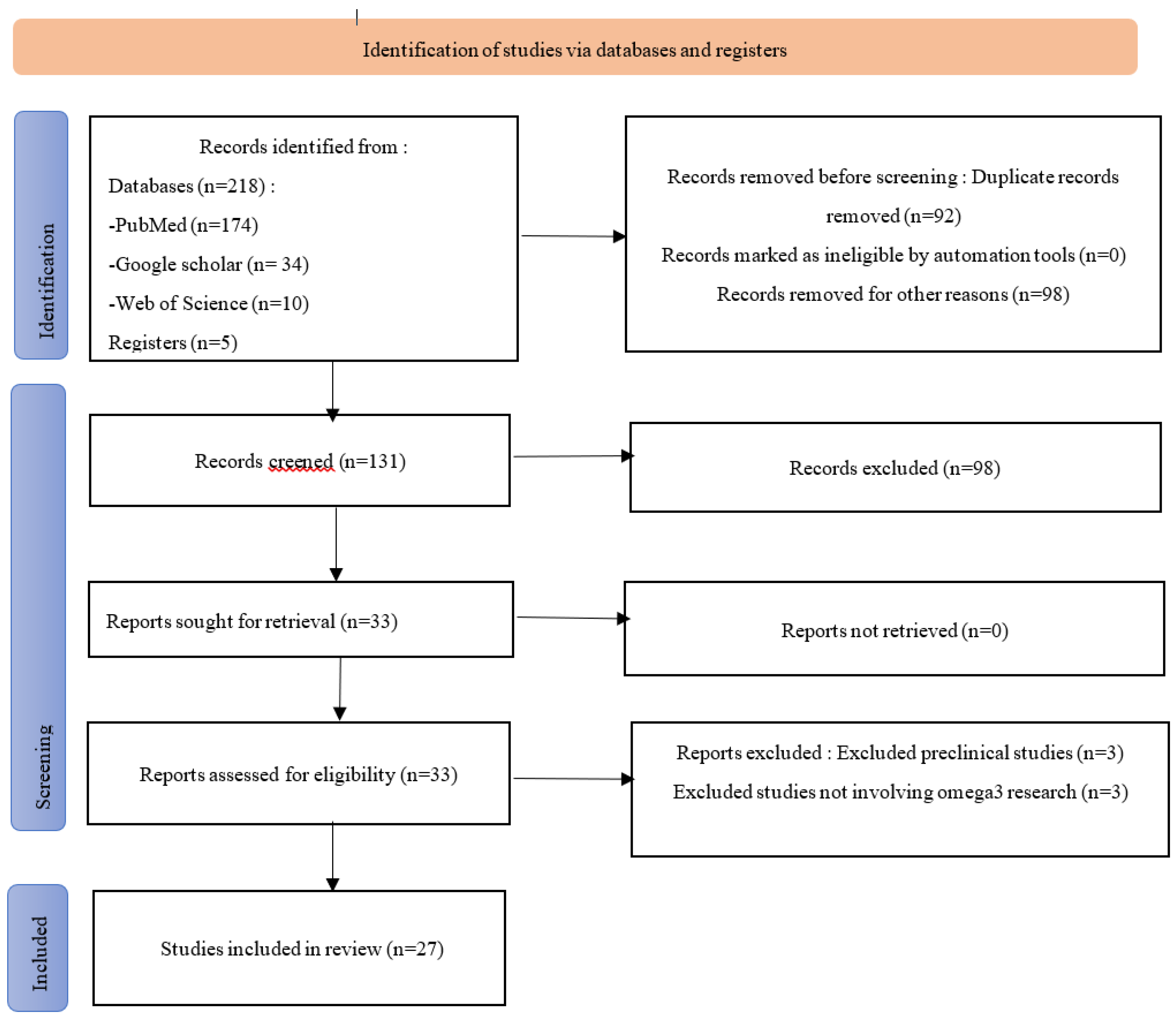

1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a progressive and irreversible decline in kidney function. CKD affects approximately 10 to 15% of the global adult population [

1]. Its prevalence varies according to countries, and access to treatment depends on the socio-economic level of each country [

2]. In 2019, more than one in ten adults suffered from kidney disease, representing nearly 850 million people worldwide [

3]. In United States, the estimated prevalence of all stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is around 13%, affecting nearly 20 million Americans [

4]. In contrast to developed countries, the exact prevalence of CKD in Africa is documented in only a few countries. In Côte d'Ivoire, the prevalence among patients admitted to internal medicine departments was 7.5% [

5]. In Burkina Faso, the prevalence in hospital settings was estimated at 27.1% during the initial nephrology consultation in 2011 [

6]. Recent data predict an increase of nearly 20% in kidney diseases over the next decade. Moreover, chronic kidney diseases (CKD) are now recognized as a global public health issue by WHO and other organizations due to their high prevalence, severity, and the substantial cost of their management [

3,

7]. In sub-Saharan Africa, most kidney diseases are diagnosed late, and their management continues to face organizational and financial challenges. This results in severe and adverse consequences on morbidity and mortality, with a high mortality rate [

8]. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in CKD, accounting for approximately 40 to 70% of deaths in international registries [

9]. Nutritional intervention studies conducted by several authors have demonstrated the benefits of fatty acids in reducing comorbidities associated with CKD [

10,

11]. Multiple studies on CKD patients have revealed that omega-3 consumption reduces blood triglyceride levels and platelet aggregation [

12]. CKD is associated with an increased risk of hypertension (HTN) and myocardial infarction. Omega-3s help prevent the worsening of HTN and renal deterioration in CKD patients [

13]. Omega-3 supplementation in CKD patients also has beneficial effects on levels of certain inflammatory factors [

14,

15,

16]. Moreover, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFAs) supplementation reduces oxidative stress in pre-terminal stage CKD patients by enhancing antioxidant enzymatic activity, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase, and catalase [

17]. In summary, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation is associated with a significant reduction in the risk of kidney failure and delays its progression [

18]. In Burkina Faso, as in the subregion, very few studies have reported the benefits of omega-3 supplementation in patients with CKD. This highlights the relevance of this study, whose general objective is to review (i) the nutritional disorders associated with CKD, (ii) the impact of omega-3 on renal function in patients and their contribution to improving the health and nutritional status of chronic kidney disease patients, and (iii) highlith dietary sources of PUFAs.

4. Discussion

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with numerous metabolic and nutritional complications that directly affect the quality of life and survival of patients. Patients with CKD are particularly vulnerable to nutritional disorders, primarily due to the dietary restrictions needed to manage complications related to the accumulation of uremic toxins, electrolyte imbalances, and metabolic dysregulations. Nutritional disorders, such as protein-energy malnutrition, mineral imbalances, appetite disturbances, and lipid metabolism anomalies, are key factors that exacerbate the morbidity and mortality of patients.

The nutritional management of CKD patients requires the prescription of a diet based on the energy and protein needs and the management of each patient’s mineral disturbances [

21]. Protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) is widely recognized as one of the most serious nutritional disorders in CKD patients, especially in those undergoing hemodialysis. [

22] reported that the prevalence of PEM in dialysis patients varies between 30 and 50%. This nutritional disorder is primarily caused by a decrease in food intake due to loss of appetite, severe dietary restrictions, and an increase in metabolic needs related to chronic inflammation. This leads to rapid depletion of protein and energy reserves, resulting in significant weight loss and reduced muscle mass. Protein-energy malnutrition in CKD patients has severe consequences. It increases the risk of infections and cardiovascular complications, contributing to high mortality. [

75] emphasized that PEM compromises the immune system, making patients more vulnerable to infections. Moreover [

76] demonstrates that malnutrition is an important and independent indicator of mortality in dialysis patients. These malnourished patients have an increased risk of hospitalization and complications such as infections or cardiovascular issues, worsening the morbidity and mortality associated with CKD and complicating disease management. Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are particularly prone to electrolyte imbalances, mainly due to the kidneys' loss of ability to maintain mineral homeostasis. Among the most common imbalances are hyperphosphatemia, hyperkalemia, and hypocalcemia. Hyperphosphatemia, resulting from the accumulation of phosphates in the body, is associated with an increase in parathyroid hormone (PTH) and secondary hyperparathyroidism, both of which contribute to bone fragility and vascular calcification[

23]. The latter is one of the main factors of cardiovascular morbidity in patients with CKD. A study by [

77], showed that reducing hyperphosphatemia through dietary strategies and phosphate binders could significantly improve survival. Additionally, hyperkalemia is another common complication in CKD, resulting from the kidneys' inability to eliminate excess potassium. Elevated potassium levels can lead to potentially fatal cardiac arrhythmias, requiring specific monitoring and dietary restrictions [

78]. Hypocalcemia, on the other hand, is associated with bone metabolism disorders and often requires calcium supplementation to stabilize blood levels. Dyslipidemia is another common nutritional problem observed in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). It is characterized by an increase in triglycerides and a decrease in HDL cholesterol (High-Density Lipoprotein) levels, thereby accelerating the risk of cardiovascular disease, a major complication of CKD [

20]. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, common in CKD, are responsible for these lipid abnormalities. [

24] highlighted that these disturbances increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases, the leading cause of death in patients with advanced CKD. Dietary interventions aimed at improving the lipid profile, such as increasing the intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), particularly omega-3s, have shown beneficial effects on reducing triglycerides and improving inflammatory markers [

26]. These nutritional interventions can thus help reduce the cardiovascular risks associated with CKD. Appetite disorders are a common complication in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), resulting from complex mechanisms involving hormonal, inflammatory, and neural mediators. [

25] demonstrated that altered levels of endocannabinoids, which regulate appetite and satiety, can lead to a significant decrease in food intake in these patients. Loss of appetite, often exacerbated by severe dietary restrictions and chronic inflammation, directly contributes to protein-energy malnutrition. Furthermore, the accumulation of uremic toxins in the blood further reduces appetite, creating a vicious cycle of malnutrition and weight loss. These nutritional complications require early interventions to prevent rapid deterioration of the patients' overall health.

Managing protein intake in CKD patients is a key component of nutritional strategies. It is important to find a balance between providing sufficient protein to avoid malnutrition and moderating intake to limit the accumulation of nitrogenous waste products.[

22] recommended moderate protein restriction for non-dialyzed CKD patients, while patients undergoing dialysis may benefit from a higher protein intake to compensate for protein losses related to the dialysis procedure.

Strict control of potassium, phosphorus, and calcium intake is crucial to prevent electrolyte imbalances. [

23] showed that phosphorus restriction, often necessary in these patients, could be effectively compensated for with phosphate binders and dietary adjustments. Calcium supplementation may also be indicated to correct hypocalcemia and prevent bone complications. In cases of severe malnutrition, nutritional supplementation, either orally or enterally, may be required. [

26] suggested that supplementation with omega-3s and other anti-inflammatory nutrients could improve nutritional status and reduce inflammatory cytokine levels in CKD patients. Additionally, specific dietary products, such as solutions containing essential amino acids, may be used to limit the accumulation of toxins while maintaining adequate protein intake. To mitigate appetite loss, pharmacological interventions, such as appetite stimulants, or specific nutritional approaches, can be implemented. [

25] demonstrated that modulating the hormonal systems regulating appetite could pave the way for innovative therapies capable of improving food intake and reducing malnutrition in this vulnerable population. Nutritional disorders in CKD patients are diverse and complex, with serious consequences on health and quality of life. Protein-energy malnutrition, electrolyte and mineral imbalances, and lipid metabolism abnormalities increase morbidity and mortality among patients. Personalized nutritional management, tailored to the specific needs of patients and the progression of the disease, is essential for improving clinical outcomes. Recent advances in research on nutritional supplements and specific interventions to improve appetite are paving the way for more targeted treatments for these patients.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), particularly omega-3s, have garnered increasing interest in the management of chronic diseases, including chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD characterized by the progressive deterioration of kidney function, is often associated with cardiovascular, inflammatory, and metabolic complications. Recent studies have shown that PUFA supplementation can have beneficial effects on various parameters related to kidney function and the quality of life of CKD patients. One of the major contributions of omega-3 PUFAs in CKD is their ability to improve endothelial function and promote vasodilation. Endothelial dysfunction is common in CKD patients and is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular complications. Asemi et al. (2016) showed that omega-3 supplementation improves vasodilation by increasing nitric oxide (NO) levels and antioxidant capacity. This is corroborated by (32)[

29], who observed a reduction in vascular oxidative stress after omega-3 PUFA intervention in rats, a key factor in protecting against vascular damage. These studies suggest that PUFAs improve vascular integrity and reduce the risk of endothelial dysfunction, a central aspect in managing the cardiovascular health of CKD patients. Furthermore, [

32] demonstrated similar results by highlighting a significant improvement in antioxidant markers, which has important implications for protecting against oxidative damage that accelerates the progression of CKD. Inflammation is a key component of the pathology of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Several studies show that omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation leads to a significant reduction in inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and TNF-α. These results are supported [

23], who demonstrated that omega-3s reduce not only CRP levels but also those of interleukin-6 (IL-6), an important marker of systemic inflammation. [

28] observed a reduction in high-sensitivity CRP levels after omega-3 supplementation, while [

33] highlighted a decrease in CRP and TNF-α levels. This reduction in inflammatory markers is crucial, as chronic inflammation is strongly linked to the progression of CKD and cardiovascular complications. All of these studies suggest that the modulation of inflammation by omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids could play a key role in slowing the progression of CKD and improving long-term clinical outcomes. Another beneficial effect of omega-3s is the improvement of the lipid profile. They help reduce triglycerides and LDL, while potentially increasing HDL.[

37] showed a reduction in triglycerides and LDL in patients with end-stage chronic kidney disease (CKD), which is essential for slowing the progression of the disease and reducing the risk of cardiovascular diseases. At the same time, [

36] reported a significant decrease in total cholesterol and triglycerides after 16 weeks of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation, further supporting the idea that these fatty acids can have a beneficial impact on lipid metabolism in CKD. Omega-3s can also improve the quality of life for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) by reducing specific symptoms associated with this condition. For example,[

35] showed a reduction in pruritus symptoms in patients undergoing dialysis. Furthermore, [

32] ont constaté une réduction des symptômes dépressifs chez les patients hémodialysés après supplémentation en oméga-3. This is particularly relevant as depression is a common issue among CKD patients, often exacerbated by the burden of the disease and intensive treatments. These results suggest that omega-3s can improve not only biological parameters but also psychological well-being and overall quality of life. The effects of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) on the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) show somewhat mixed results. [

78] found that patients with CKD and diabetes who had a low intake of linolenic acid (omega-3 PUFA) experienced a faster progression of kidney disease. However, some studies suggest that omega-3s may slow down this progression. [

41] reported a significant reduction in the risk of vascular access failure in dialysis patients after PUFA supplementation, suggesting an indirect protective effect on kidney function. However, other studies, such as the systematic review by [

22] highlighted more nuanced results, emphasizing that uncertainties still exist regarding the direct effects of PUFAs on the progression of CKD. This indicates that although PUFAs have therapeutic potential, their direct impact on kidney function still requires further investigation. Other beneficial effects include the reduction of serum creatinine [

24], energy intake through the reduction of protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) [

22], attenuation of renal damage induced by sodium arsenate [

26], improvement of appetite related to endocannabinoids (25), anti-inflammatory effects, and effects on coagulation markers [

45]. [

29] showed that omega-3s reduce vascular oxidative stress, a contributing factor to renal dysfunction. Finally, [

44] observed that low levels of PUFAs are associated with higher mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Polyunsaturated fatty acids, particularly omega-3s, have beneficial effects on various aspects of renal and cardiovascular function in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The main actions include improving endothelial function, reducing inflammation and blood lipids, as well as enhancing the quality of life of patients. Although the results on CKD progression are more nuanced, the data suggest that omega-3 supplementation could offer a complementary strategy for managing patients with CKD, improving both biological parameters and quality of life.

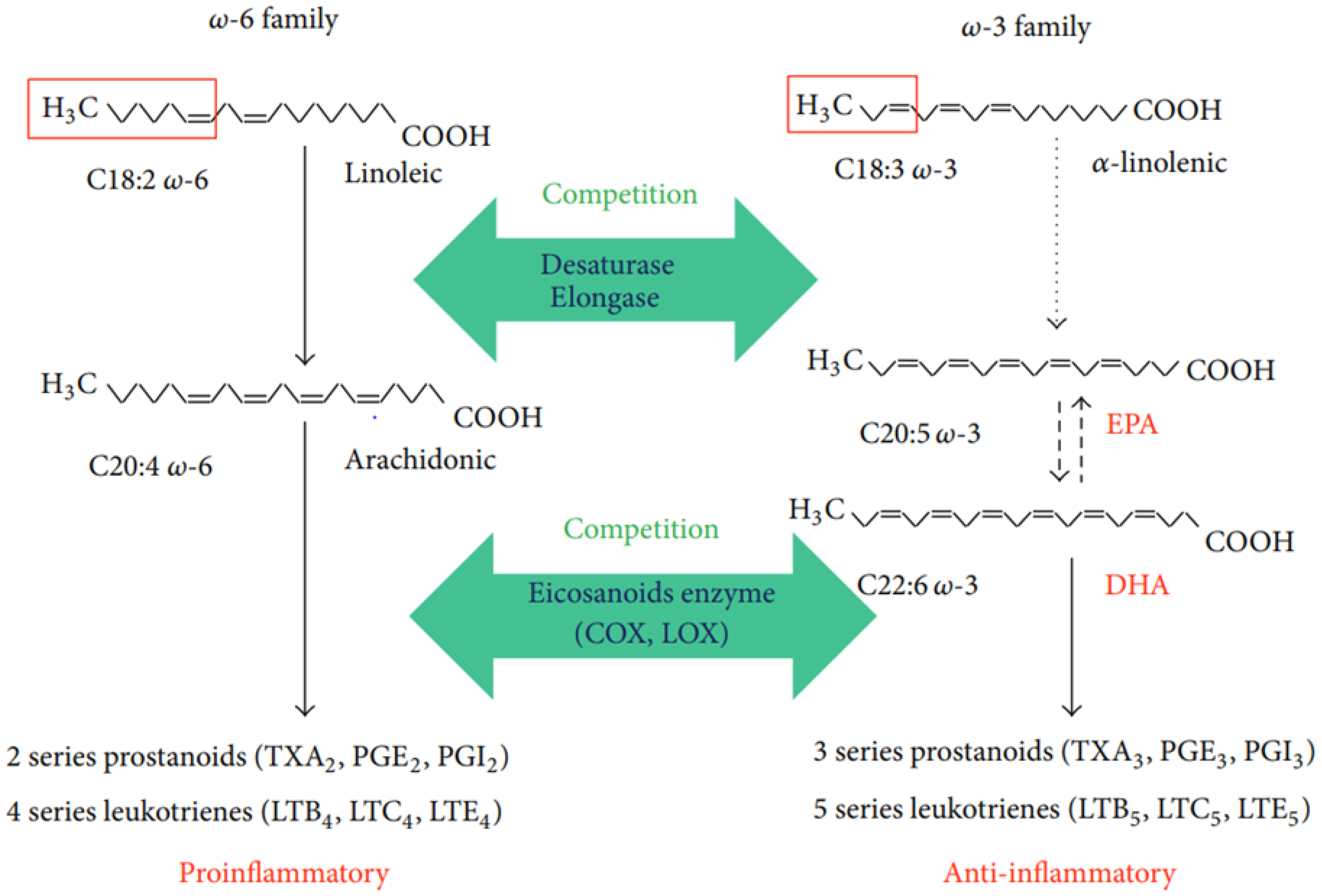

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), particularly omega-3 and omega-6, are essential for maintaining human health, and their presence varies according to dietary sources. Linoleic acid (18:2 n-6) and alpha-linolenic acid (18:3 n-3), plant-derived precursors of omega-6 and omega-3 PUFAs, respectively, compete for the same enzymes that convert them into 20- and 22-carbon PUFAs. As a result, their optimal intake levels are mutually dependent. Omega-3 PUFAs are primarily found in plant-based foods such as seeds, nuts, and certain oils. For example, vegetable oils like flaxseed, chia, and walnut oils are particularly rich in alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), a precursor of omega-3s. This precursor is essential because it must be obtained through the diet, as the human body cannot synthesize it directly [

58]. Saturated fatty acids (SFAs), primarily found in animal products and certain vegetable oils such as palm oil, are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and obesity when consumed in excess [

79]. Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), present in olive, hazelnut, and rapeseed oils, play a role in lipid regulation and have beneficial effects on the cardiovascular system, particularly within the context of a Mediterranean-type diet. Studies show that this diet, rich in MUFAs, reduces the risks of cancer and cardiovascular diseases due to significant antioxidant properties [

52,

53]. In low-income countries like Burkina Faso, omega-3 PUFAs are primarily sourced from staple foods such as chitoumou (Cirina butyrospermi) and leafy vegetables, which are rich in ALA. These foods represent important local sources of omega-3s, helping to meet the omega-6/omega-3 ratios recommended by the WHO (between 5 and 10) [

69]. However, processed foods and local dishes, while providing essential lipids, are often deficient in omega-3s, resulting in a high omega-6/omega-3 ratio, which is unsuitable for maintaining a proper lipid balance [

73]. A simple and feasible solution would be to prioritize local oils richer in omega-3s for culinary preparations to reduce this lipid imbalance. The consumption of sauces, often combined with local oils or animal-derived ingredients such as dried fish, contributes to lipid intake but may also lead to high ω6/ω3 ratios. For example, dishes such as amaranth-fish sauce and preparations including teff reach a satisfactory ω6/ω3 ratio, while other sauces, although they meet lipid requirements, remain deficient in omega-3 [

74]. The use of ingredients such as leafy vegetables and seafood, along with local oils rich in omega-3s, could enhance the intake of ALA, EPA, and DHA in traditional dishes. Omega-3 PUFAs are particularly important in a balanced diet. In countries like Burkina Faso, where the diet is largely plant-based, local sources of ALA, such as chitoumou and leafy vegetables, play a crucial role. However, adjustments in culinary habits, particularly through the use of omega-3-rich oils, could address the deficit in omega-3 PUFAs, improving nutritional quality and contributing to the prevention of cardiovascular diseases, inflammatory diseases, including CKD.

Recent research consistently demonstrates the role of adequate omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) intake in the prevention of several diseases, particularly cardiovascular diseases. Moreover, data from Rahmawaty et al.'s study support the notion that increasing long-chain omega-3 PUFA intake significantly reduces early-age risk factors for cardiovascular diseases [

79].