1. Introduction

Burnout represents an increasingly common phenomenon among healthcare professionals. It is characterized by a condition of physical, emotional and mental exhaustion caused by chronic stress at work [

1]. Healthcare workers working in particular settings, such as pediatric oncology, are exposed to significant levels of stress because of the complex and often traumatic nature of their work, which involves treating children with life-threatening illnesses. A systematic review and meta-analysis indicate that pediatric oncology nurses are especially vulnerable to emotional exhaustion, exhibit moderate levels of depression despite experiencing high personal accomplishment [

2]. According to Pellegrino [

3], burnout symptoms can manifest in various ways: Physical: insomnia, headaches, general discomfort; behavioral: irritability, impulsivity, isolation; cognitive-affective: depression, hypersensitivity/insensitivity, cynicism, pessimism, inattention.

Healthcare professionals in complex work environments, like pediatric oncology departments, engage in emotionally demanding relationships with patients. These relations between the caregiver and the patients can lead to significant psychological stress at both individual and group levels. Studies have identified several factors contributing to burnout risk, including the type of disease - cancer diagnosis are often perceived as “incurable” or “inescapable” - the emotional intensity of relationships with patients, the management of pain and suffering, and the inevitable and frequent exposure to death [

4]. Burnout not only affects the mental and physical well-being of healthcare workers, but also the quality of care provided and their relationship with patients and families. Therefore, it is essential to identify strategies to prevent and manage burnout in a complex setting such as pediatric oncology. The most recent scientific evidences define art as a possible tool for preventing burnout among healthcare workers. Artistic practices in healthcare settings have been linked with stress reduction, improved emotional well-being, and enhanced resilience [

5]. Among patients art therapy facilitates emotional expression, personal reflection, and connection with self and others [

6]. Similarly, for healthcare worker, it provides strategies for dealing with work-related traumatic experiences. Several studies have investigated the potential of art as a supportive tool for healthcare providers, highlighting how it can foster greater emotional awareness and a sense of personal gratification [

7]. In pediatric oncology, art-based interventions could help create reflective and supportive spaces, promoting well-being in healthcare workers, improving stress management and reducing burnout risk.

This article presents the Art-Out pilot project, a team-building course integrating clay therapy to reduce burnout among healthcare workers.

2. Materials and Methods

In 2022, the Art-Out pilot project aimed at the healthcare staff of Pediatric Oncology Unit at the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS in Rome, using clay therapy to prevent burnout and improve the emotional climate of the team. The group was led by a ceramist from the Lene Thun Foundation and by a psychologist-psychotherapist from the Pediatric Oncology Unit. The project duration was 10 months; the project culminated in the development of a work of art created by the group of participants and subsequently displayed in the hospital's public spaces.

The primary objective of the study was to test how much the team-building course, through clay therapy, helped improve the work climate and promoted well-being in healthcare workers, reducing burnout levels. The structure of the multidisciplinary project included respective steps:

- -

Literature review to investigate the phenomenon, with focus on pediatric oncology-hematology areas;

- -

Assessment (T0) of the degree of nursing staff burnout by validated screening tests (MBI, TAS-20, DERS);

- -

Implementation of team building through clay therapy with two monthly meetings for the two subgroups of providers;

- -

Final evaluation (T1) of how the variables under study changed.

2.1. Participants

The population involved in the study consists of the nursing team affiliated with the Pediatric Oncology Unit at the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS. Of the 19 members of the equipe, 13 (68.4%) took part in the project. The group of operators was divided into two subgroups to allow each staff member to participate without interfering with regular clinical care. Each participant completed a questionnaire to facilitate the collection of demographic data. The detailed demographic variables of the participants (

Table 1) included: age, gender, role in the department's care team, professional seniority and length of service within the Pediatric Oncology Unit, and presence or absence of a personal psycho-therapy. The age range was 23 to 61 years, and only one man participated in the study. Each participant followed at least 8 (80%) of the 10 meetings scheduled for each group, and all completed the study assessments pre-intervention (T0) and at the conclusion of the project (post-intervention T1). Initial recruitment took place in November 2022. Data collection was conducted pre- and post-intervention: from November 16 to 31, 2022 at T0 and from September 15 to 31, 2023 at T1. All healthcare workers in the department including nurses, researchers and health and social workers were invited to participate voluntarily with no exclusion criteria. No financial incentives were provided to participants, instead they demonstrated motivation and interest; the participants coordinated their attendance with their supervisor based on their shifts. Their participation was voluntary, and their response was considered informed consent for participating in the study. Complete confidentiality of data collected was maintained.

Table 1.

Demographic variables (N=13).

Table 1.

Demographic variables (N=13).

| Demographic Variables |

N (%) |

Means ± SD |

| Age, years |

|

43,31 |

Gender

Male |

1 (7.7) |

|

| Female |

12 (92.3) |

|

| Role in pediatric oncology |

|

|

| Nurse |

12 (92.3) |

|

| Care assistant |

1 (7.7) |

|

| Professional seniority |

|

|

| 0-10 |

5 (38.5) |

|

| 11-20 |

0 |

|

| > 20 |

8 (38.5) |

|

Professional seniority in

pediatric oncology |

|

|

| 0-10 |

6 (46.1) |

|

| 11-20 |

4 (30.8) |

|

| > 20 |

3 (23.1) |

|

| Psychotherapy |

|

|

| Yes, still in progress |

1 (7.7) |

|

| Yes, in the past |

3 (23.1) |

|

| No, never |

9 (69.2) |

|

2.2. Tools

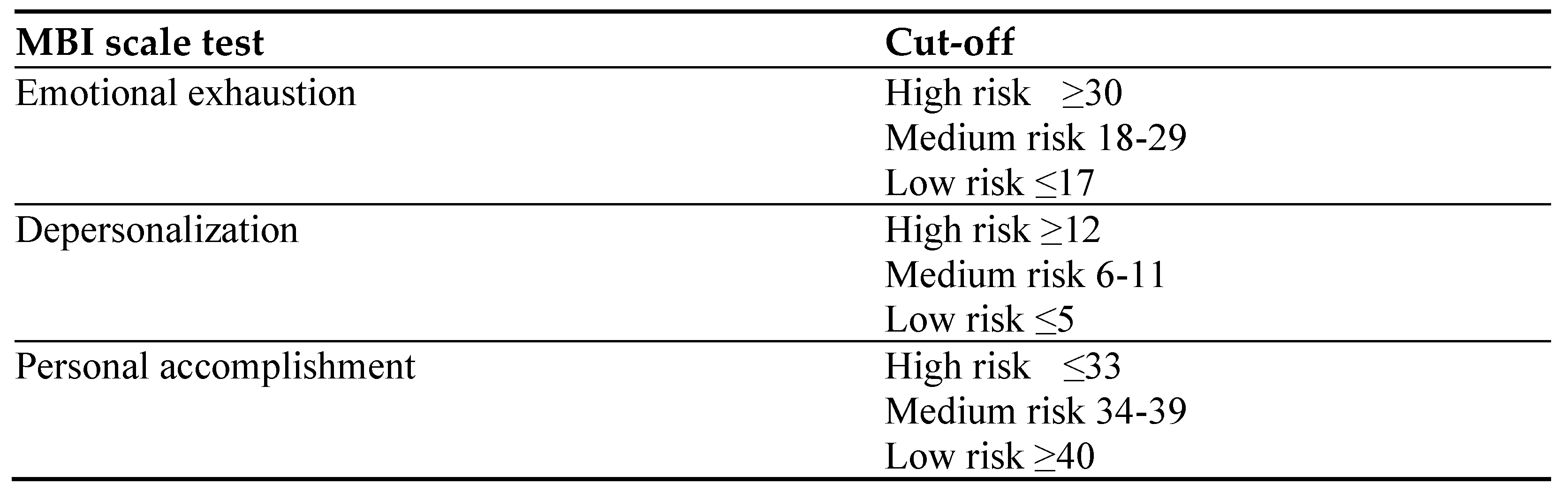

The following psychological tests were used to monitor the variables under examination: Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) and Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS). The presence and degree of burnout among healthcare workers was assessed through the Italian version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) [

8]. This questionnaire has been widely used in literature regarding mental health in healthcare professionals and it’s the standard tool for measuring burnout among healthcare workers [

9]. The instrument assesses an individual's level of burnout by asking respondents to answer how often certain emotions are experienced over the course of a year. On a 7-point Likert scale, respondents rate how often they experience certain emotions, from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). The questions assess the three main subscales on work-related feelings: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and personal accomplishment. The emotional exhaustion subset consists of nine questions, the depersonalization subset includes five questions, and the personal fulfilment subset includes eight questions. A high level of burnout is defined as a score of 30 or higher in the emotional exhaustion subset, a score of 12 or higher in the depersonalization subset, or a score of 33 or lower in the personal achievement subset. The categories of burnout levels are “high,” “moderate,” and “low.” High levels of burnout are correlated with higher scores in the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization items and lower scores in personal accomplishment. Alexithymia was assessed using the Italian version Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) with twenty items [

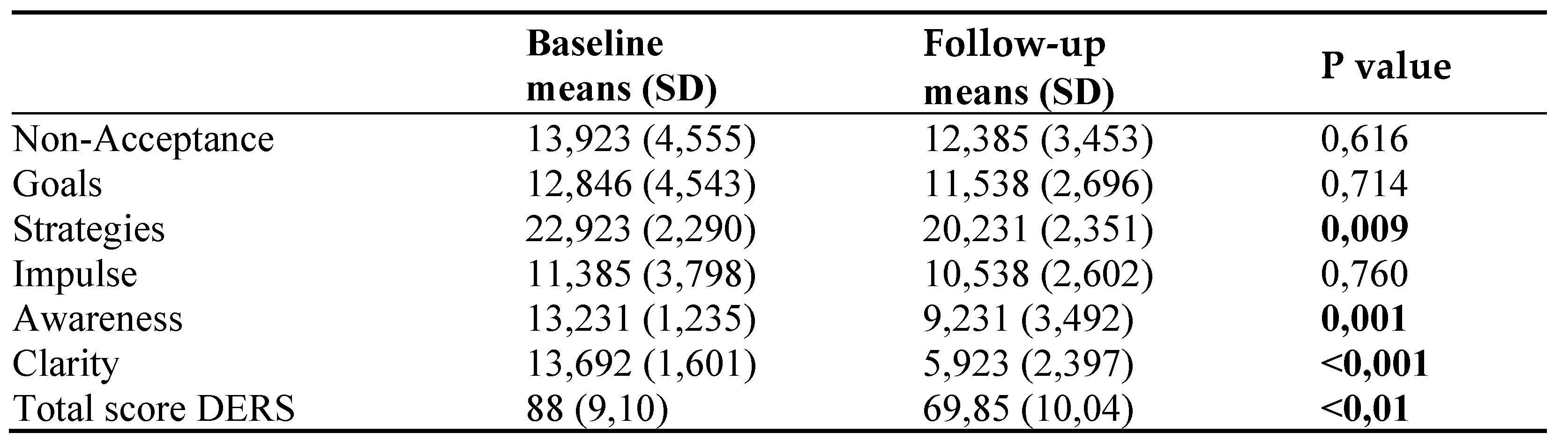

10]. A score of 61 or higher was considered indicative of alexithymia. The TAS-20 has a three-factor structure: factor 1 assesses the ability to identify feelings and distinguish between feelings and the bodily sensations of emotional arousal (difficulty in identifying feelings); factor 2 reflects the inability to communicate feelings to other people (difficulty in describing feelings); and factor 3 assesses outward-oriented thinking. The presence of any difficulties in the regulation of negative emotions was assessed through the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), a questionnaire that specifically investigates awareness and acceptance of one's emotions and the ability to use appropriate emotional regulation strategies. The original version was presented by Gratz and Roemer [

11], and was later translated and adapted to Italian by Sighinolfi et al. [

12]. It consists of 36 items with a 5-value Likert scale ranging from “almost never” to “almost always.” It includes 6 scales: non-acceptance of negative emotions (non-acceptance), difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviours when distressed (goals), belief that there is little that one can do to regulate emotions effectively (strategies), difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed (impulse), lack of emotional awareness (awareness) and lack of emotional clarity (clarity) [

11,

12].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

In the absence of data on burnout within the target population, we set the sample size for this study at 13 subjects that correspond to the total number of nurses from our Pediatric Oncology unit who decided to participate in the pilot project. Despite the small sample size, it captures various expected proportions, with a 95% confidence level and a margin of error ranging from a minimum of 2% (for an expected proportion of 1%) to a maximum of 10,2 (for an expected proportion of 50%). Quantitative variables were presented through mean and standard deviation (SD), qualitative variables through absolute and percentage frequency tables. Comparison of means was performed by Mann-Whitney test, which was considered statistically significant for p-values <0.05. Statistical evaluation was performed by XLSTAT 2023.1.4.1408.

2.4. The Art-Out Project

The Art-Out Project aims to improving emotional climate and prevent and limit burnout in healthcare personnel. It uses art and its therapeutic value in a specific work environment, i.e. Pediatric Oncology. The Art-Out Project combines the experience of team building with clay therapy, promoting the creative process fostered by the manipulation of clay and its benefits. The nursing team participated in focus groups centered on key themes that emerged during group brainstorming sessions. These themes were further explored through expressive work and clay manipulation. The meetings addressed various areas of vulnerability, including communication, individual and group boundaries, emotional responses to the work environment, and group dynamics that need monitoring like personal and interpersonal conflict, tension, cohesion, confusion, boredom, motivation, peer pressure, subgroups formation and unclear goals. Each meeting fostered group sharing of emotions, experiences, and thoughts related to the professional context. The clay work, serving as the decompressive phase at the end of each session, provided a tangible representation of the issue discussed during the meeting. The culminating artistic piece, titled “The Burnout Spiral,” encapsulates the group’s journey serving as a kind of shared “emotional signpost” born from abstract concepts such as fear, empathy and active listening listening, into a figurative form. Each emotional insight or warning was modelled on soft clay tiles of equal size which were then assembled into a permanent installation in the hospital lobby. serving as a visible trace in the hospital environment of the path undertook together by the group. Additionally, the team building experience allowed to promote and improve communication within the nursing team, highlighting critical challenges like available resources, protective and risk factors within the work environment.

3. Results

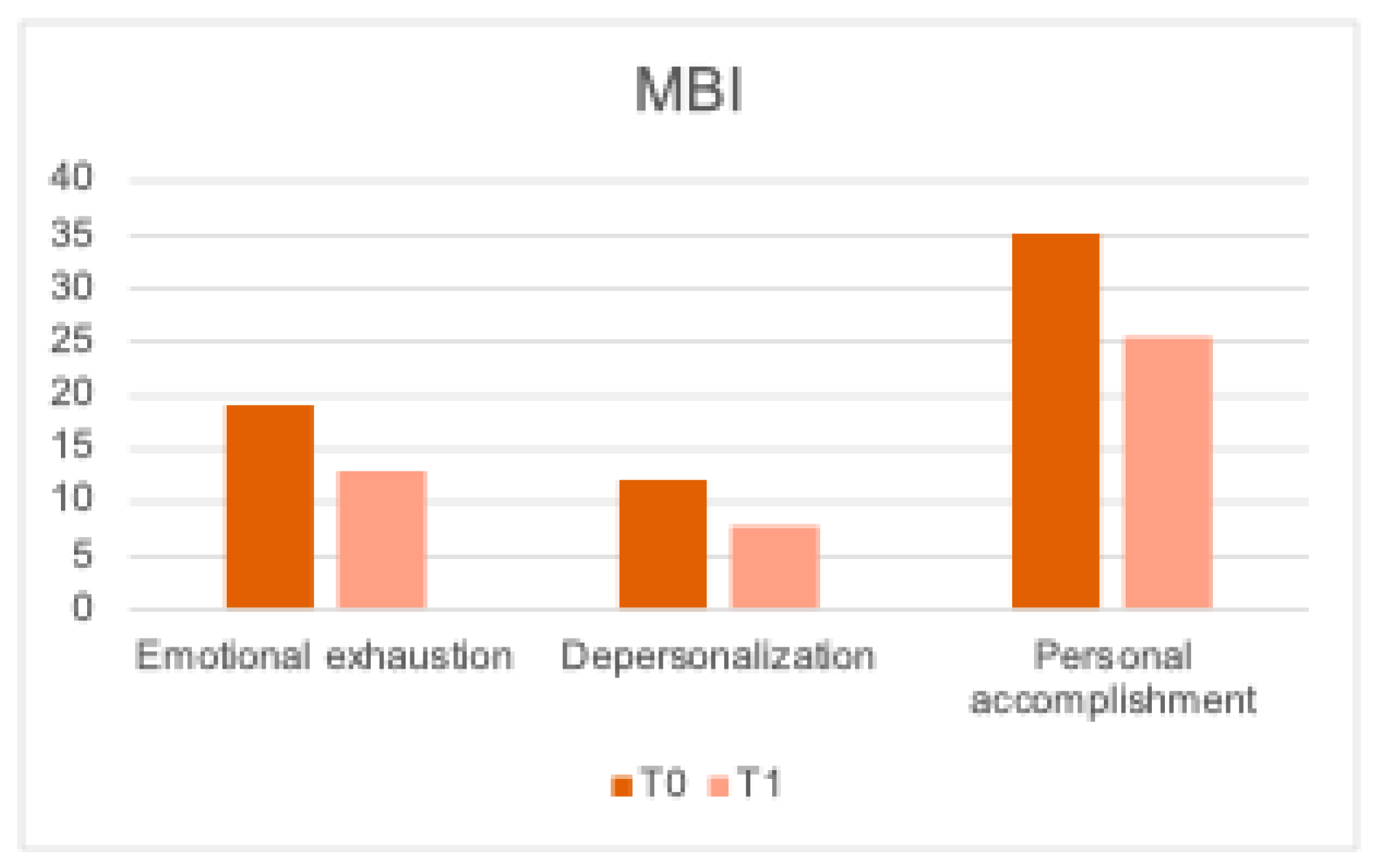

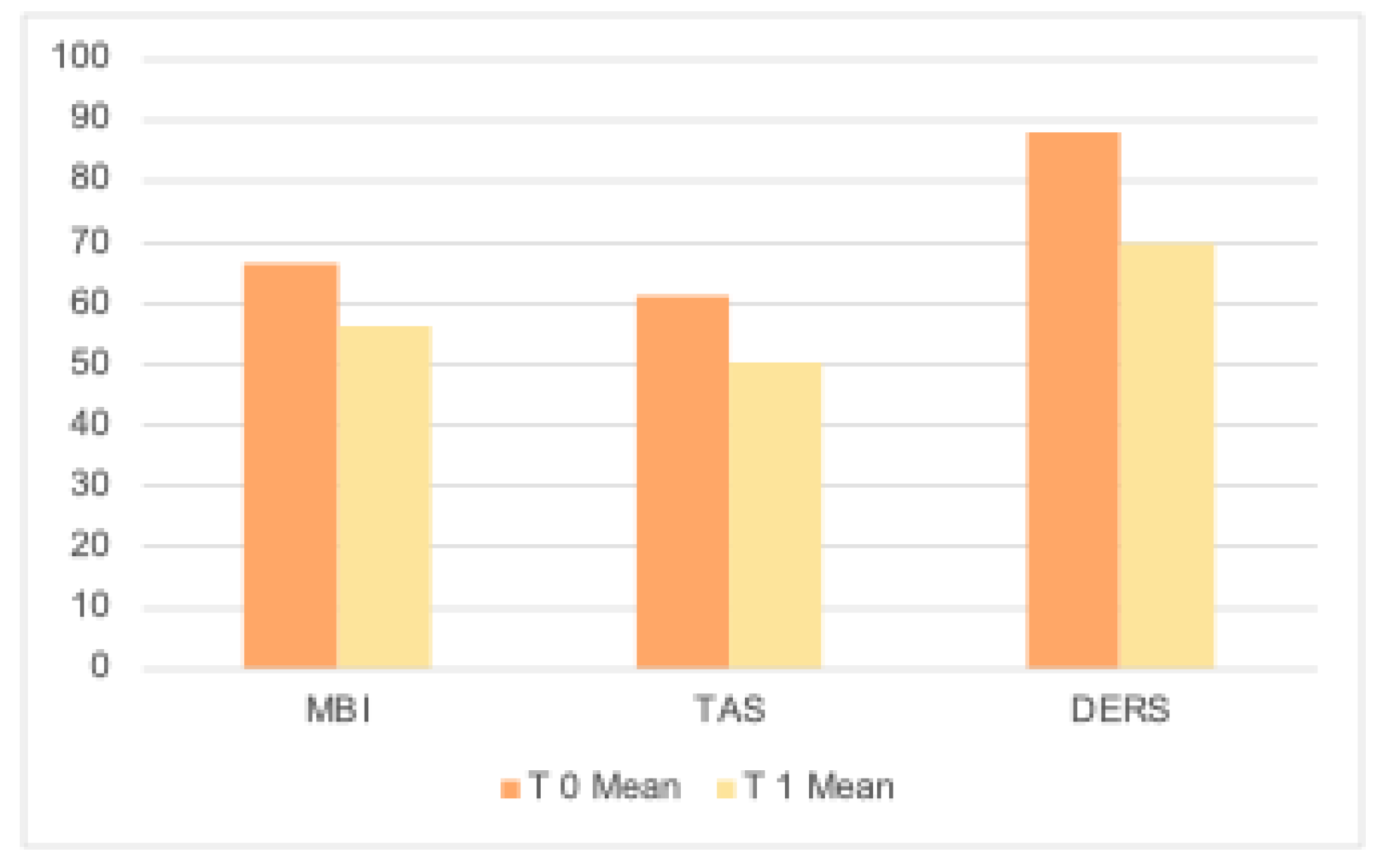

The prevalence study conducted on the enrolled nursing staff (N=13) analysed the burnout risk levels, emotional dysregulation, and alexithymia before (T0) and after (T1) the team building course. In Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) at T0 (

Table 2) compared with the baseline cut-off (

Table 3), medium risk was found in personal accomplishment (T0=35.23), high risk in depersonalization (T0=12.07) and medium risk in emotional exhaustion (T0=19.07). At T1 in the MBI, all the variables analysed improved from the baseline cut-off (

Table 3). In particular, the variable “emotional exhaustion” which had a value of 19.07 at T0 (medium risk) reduced statistically significantly at T1, reaching a value of 12.92 (p=0.039), placing it below the clinical reference range. ”Depersonalization” showed a statistically significant decrease at T1 (p=0.013). Our results showed significant improvement in the MBI total score (

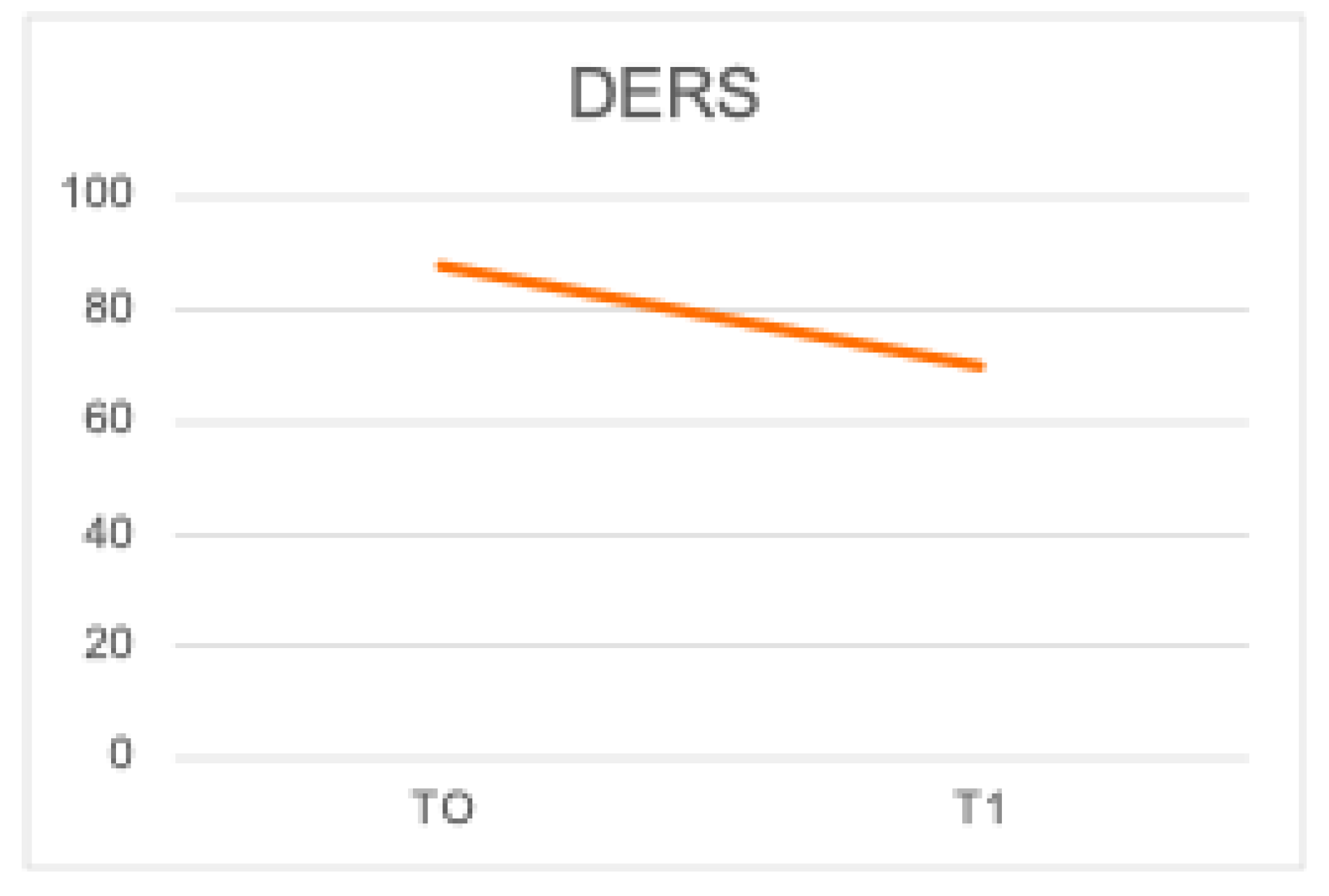

Figure 1) (p=0.019). In Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) (Table 4), the total score assessed at T0 (T0=61.15) falls within the clinically significant range for alexithymia (cut off: ≥61 Alexithymia; 52-60 Borderline; ≤51 No alexithymia). Ten months later, score comparison performed at T1 (T1=50.15) shows a significant (p=0.028) improvement in total score compared to T0 (61.15). Compared to the reference cut-off, the score is below the clinical reference range. In Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), the result obtained at T0 shows a high score (T0=88) that falls within the clinical reference range (cut-off: score totals clinical range 80-127).

In the reassessment at T1, the value drops to 69.85 (

Figure 3), showing a significant reduction (<0.01) below the cut-off. In particular, statistically significant improvement is shown in the variables “Strategies”, “Awareness,” and “Clarity” as well as in the total score (

Table 5).

In summary, ten months later, at the end of the team-building, re-evaluated nursing staff (N=13) show significant improvement in all variables analyzed (

Table 6;

Figure 4).

3.1. Figures, Tables and Schemes

Table 2.

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).

Table 2.

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).

Table 3.

cut-off Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).

Table 3.

cut-off Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).

Table 5.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS).

Table 5.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS).

Table 6.

T0 and T1 of all variables analyzed.

Table 6.

T0 and T1 of all variables analyzed.

Figure 1.

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).

Figure 1.

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).

Figure 2.

Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20).

Figure 2.

Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20).

Figure 3.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS).

Figure 3.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS).

Figure 4.

T0 and T1 of MBI, TAS and DERS.

Figure 4.

T0 and T1 of MBI, TAS and DERS.

4. Discussion

The study showed high burnout risk among pediatric oncology nurses at baseline. Data analysis of MBI scores, which assesses the level of burnout, showed medium risk in the personal accomplishment (T0=35.23), high risk in depersonalization (T0=12.07) and medium risk in emotional exhaustion (T0=19.07). In the TAS-20 (T0=61.15) assessing alexithymia and the DERS (T0=87) analysing emotional dysregulation, the total score was in the clinically significant range for these two scales (Table 4 and Table 5). Baseline scores emphasized the need of burnout prevention strategies and effective treatment plans for healthcare workers; it should also be noted that, as a recent systematic review highlighted, burnout is an increasingly common condition in healthcare workers in many different countries [

13,

14,

15]. Other studies have highlighted that burnout and work-related mental exhaustion in healthcare workers have exacerbated in recent years due to changes in the healthcare system during and after the Covid-19 pandemic. Increasing scientific interest in the use of art therapy to address burnout has led to further studies aimed at evaluating its efficacy in preventing and lowering burnout risk [

7]. In accordance with the literature our study, the Art-Out pilot project, aims to enhance team building and assess the efficacy of clay workshop and art making as a mean to reduce and prevent burnout. Ten months later (T1), at the end of the Art-Out course, the nursing team was evaluated noting a marked improvement in all variables investigated. In the MBI, all scales analysed improved from baseline. In particular, the variable “emotional exhaustion” (T1=12.92 p=0.028) and the variable “depersonalization” (T1=7.84 p=<0.013) were significantly reduced below the clinical reference range. These data show how this approach has enhanced emotional climate within the nursing staff and how it has significantly improved emotional management skills. In summary, there was a significant improvement in the MBI score (T1=56.29 p=0.019), supporting the hypothesis that the intervention was effective. The TAS-20 and DERS score confirmed an improvement in emotional management in the nursing staff at T1 (TAS-20=50.15; DERS=69.85). Overall, study results showed a marked improvement in the nurses’ awareness and acceptance of their emotions as well as acquisition of appropriate emotional regulations strategies.

5. Conclusions

Overall, our results highlights the emotional burden of pediatric oncology healthcare workers and the need for structured support programs to enhance the staff well-being and clinical care quality.

Existing literature highlights how art can be an effective tool to improve well-being in healthcare personnel [

7,

16,

17]. Based on these evidencesthe pilot project “Art-Out” was initiated specifically incorporating clay therapy. Team building empowered by expressive work resulted in reduced levels of burnout and improved analysed variables. The group course was positively received by the participants and allowed a better understanding of the emotional challenges of the nursing team and how to improve emotional management of patients’ physical and psychological suffering. The shared group experience enhanced the creative process and promoted the psychological well-being of the nursing staff, improving their awareness of their emotions and their ability to regulate them. The first limitation of our study is sample size, consisting of only 13 participants. The refusal of some professionals (N=7) due to time constraints further reduced the sample size, potentially impacting the representativeness of our results. Given this limitation the therapeutic value of other team-building interventions incorporating clay therapy could be investigated in other oncology and pediatric oncology settings.

Additionally, the sample is limited to nurses and healthcare assistant not involving other professionals who are also at risk of burnout. To address this gap, phase two of the project is currently underway to involve medical staff in the intervention.

In conclusion, the results of this pilot study highlight the significant emotional burden experienced by healthcare workers, showing the importance of implementing innovative supportive interventions to prevent burnout. These interventions have the potential to enhance the workers well-being improving team dynamics and contributing to the quality of care provided to patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: The concluding artistic work “The Burnout Spiral”. Caption: Burn out: a spiral in motion “ArtOut” is the need to make visible, through the plastic material of clay, the thoughts, experiences and complex emotions, with the aim of cushioning and preventing the effects of “Burn-out” (work stress). This work is the result of a path creative, individual and collective, aimed at improve the working climate of the staff. The tiles make up a spiral that from the center seems to expand outward outward, or from the outside return to the center, but which is always the image of a movement: courageous, necessary and vital. The spiral is one of the most ancient and fascinating precisely because of its ability to reconcile opposites: introspection and expansion, involution and evolution; it is a vortex that sucks in but also energy that radiates. And in this complexity, as the 28th tile suggests:“don't panic!”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G, L.P., P.A., L.D., M.T., A.Ru. and A.Ro.; methodology, M.T., D.P.R.C., G.P., L.D., S.S., A.M.V, C.S., D.T., and A.G.; validation, A.G., L.P., D.R.P. C., P.A.,I.P.,S.R.,S.P.,R.P.,F.B.,D.C.,C.D.L.,A.B., S.S., G.P., C.S., A.M.V., and L.D.; formal analysis, A.Ro., D.T., A. G.; investigation, L.P., L.D., C.S., G. P., A.M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G., A.Ro., D.T., A.Ru, L.D..; writing—review and editing, A. Ro., A.G., A.Ru., and L.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Università Cattolica Sacro Cuore-Policlinico Gemelli IRCCS (protocol code DIPUSVSP-15-11-2241, date of approval 15/11/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

More detailed data can be obtained by contacting the author of the communication.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank “Fondazione Lene Thun” for their dedicated patient care and scientific support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/.

- De la Fuente-Solana, E. I. , Pradas-Hernández, L., Ramiro-Salmerón, A., Suleiman-Martos, N., Gómez-Urquiza, J. L., Albendín-García, L., & Fuente, G. A. C.-D. L. Burnout syndrome in paediatric oncology nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare (Basel) 2020, 8(3),309. [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino F. La sindrome del burn-out. Centro Scientifico Ed., Torino, 2000.

- Sidoti E., Arcoleo A., Tringali G., Batista N.A., & Sonzogno M.C. Supportive care in a paediatric onco-haematological service: Therapeutic patient education and burn-out prevention in health workers. Supp Palliat Cancer Care 2006, 3(1), 29–35.

- Bolwerk, A. , Mack-Andrick J., Lang F. R., Dörfler A., & Maihöfner C. How art changes your brain: differential effects of visual art production and cognitive art evaluation on functional brain connectivity. PloS One 2014,9(7), e101035. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M. M. , Saini B. & Smith L. Using drawings to explore patients' perceptions of their illness: a scoping review. J Multidiscip Healthc 2016, 9, 631–646. [CrossRef]

- Stuckey H., L. & Nobel J. The connection between art, healing, and public health: a review of current literature. Am J Public Health 2010, 100(2), 254–263. [CrossRef]

- Portoghese, I. , Leiter M.P., Maslach C., Galletta M., Porru F., D'Aloja E., Finco G., Campagna M. Measuring Burnout Among University Students: Factorial Validity, Invariance, and Latent Profiles of the Italian Version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory Student Survey (MBI-SS). Front Psychol 2018,9:2105. [CrossRef]

- Maslach C., Jackson S., Leiter M. Maslach burnout inventory manual. Palo Alto, California: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1996.

- Bressi, C. , Taylor G., Parker J., Bressi S., Brambilla V., Aguglia E., Allegranti I., Bongiorno A., Giberti F., Bucca M., et al. Cross validation of the factor structure of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: An Italian multicenter study. J Psychosom Res 1996;41:551–559. [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K.L. , Roemer L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2004,26, 41–54. [CrossRef]

- Sighinolfi, C. , Norcini Pala A., Chiri L. R., Marchetti I., & Sica C. Traduzione e adattamento italiano del Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Strategies (DERS): una ricerca preliminare. Psicoterapia Cognitiva e Comportamentale 2010, 16, 141-70.

- Tjasink, M. , Keiller E., Stephens M., Carr C.E., Priebe S. Art therapy-based interventions to address burnout and psychosocial distress in healthcare workers-a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2023,23(1):1059. [CrossRef]

- HaGani, N. , Yagil D., Cohen M. Burnout among oncologists and oncology nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol 2022,41(1):53-64. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Calderon, J. , Infante-Cano M., Casuso-Holgado M.J., García-Muñoz C. The prevalence of burnout in oncology professionals: an overview of systematic reviews with meta-analyses including more than 90 distinct studies. Support Care Cancer 2024,32(3):196. [CrossRef]

- Italia, S. , Favara-Scacco C., Di Cataldo A., Russo G. Evaluation and art therapy treatment of the burnout syndrome in oncology units. Psychooncology 2008,17(7):676-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabi, R.O. , Hietanen P., Elmusrati M., Youssef O., Almangush A., Mäkitie A.A. Mitigating Burnout in an Oncological Unit: A Scoping Review. Front Public Health 2021,9:677915. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).