Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

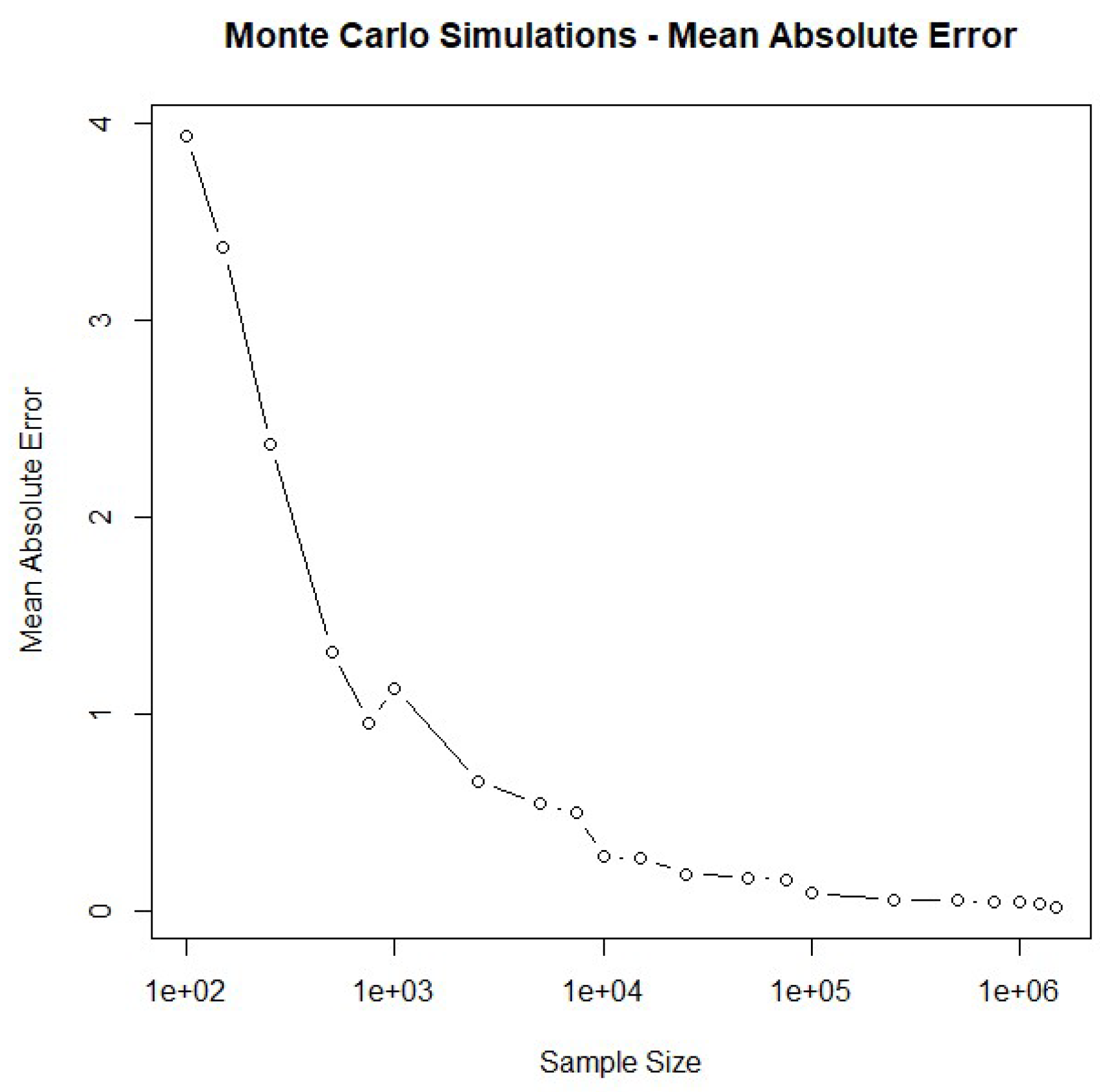

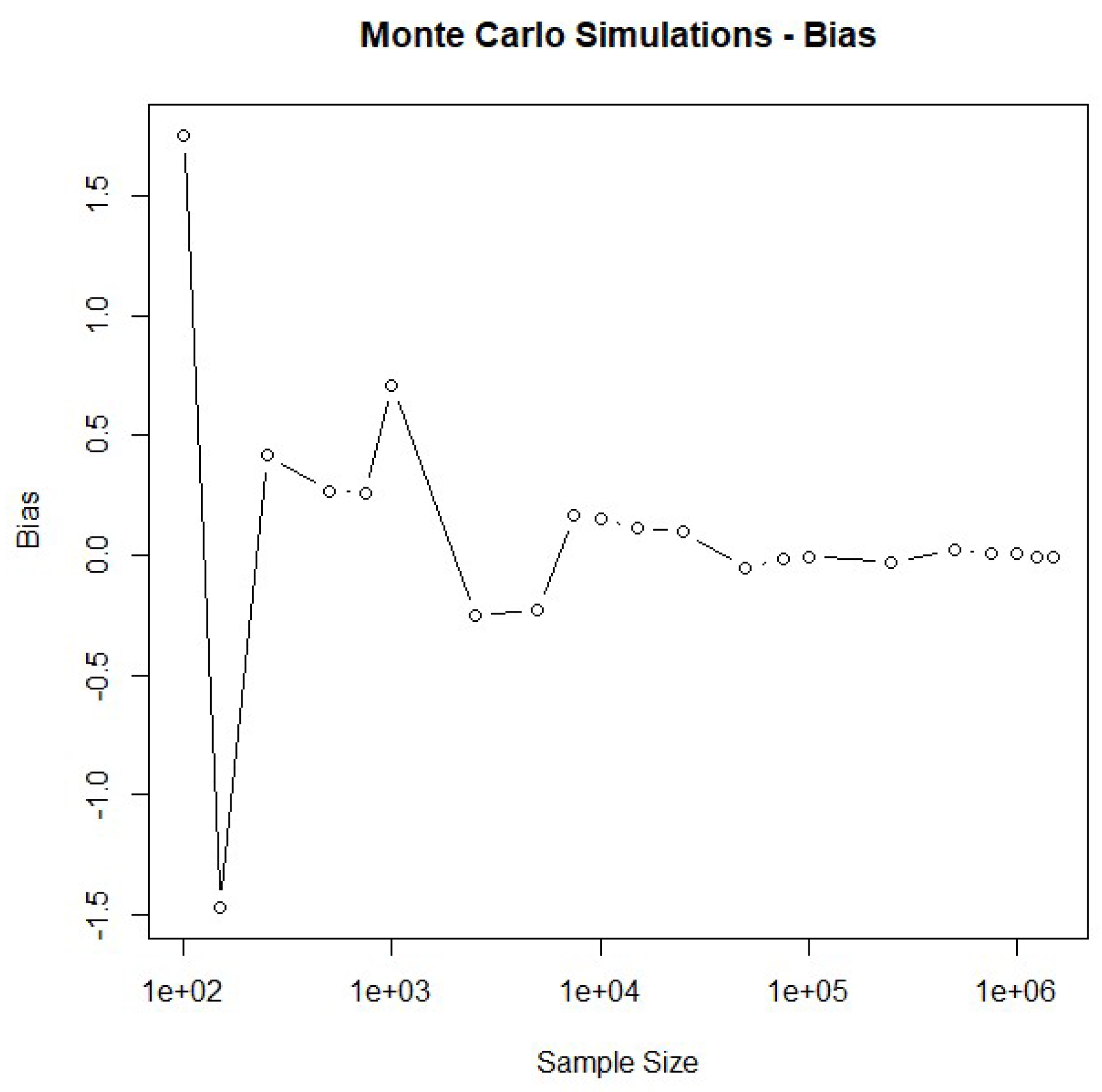

Forecast risk management is central to the financial management process. The study aims to apply Monte Carlo simulation to solve three classic probabilistic paradoxes and their implementation in corporate financial management. The article presents Monte Carlo simulation as an advanced tool for risk management in financial management processes. This method allows for a comprehensive risk analysis of financial forecasts, making it possible to assess potential errors in cash flow forecasts and predict the value of corporate treasury growth under various future scenarios. In the investment decision-making process, Monte Carlo simulation supports the evaluation of the effectiveness of financial projects by calculating the expected net value and identifying the risks associated with investments, allowing more informed decisions to be made on project implementation. The method is used in reducing cash flow volatility, which contributes to lowering the cost of capital and increasing the value of a company. Simulation also enables more accurate liquidity planning, including forecasting cash availability and determining ap-propriate financial reserves based on probability distributions. Monte Carlo also supports the management of credit and interest rate risk, enabling simulation of the impact of various economic scenarios on a company's financial obligations. In the context of strategic planning, the method is an extension of decision tree analysis, where subsequent decisions are made based on the results of earlier ones. Creating probabilistic models based on Monte Carlo simulations makes it possible to take into account random variables and their impact on key financial management indicators, such as free cash flow (FCF). Compared to traditional methods, Monte Carlo simulation offers a more detailed and precise approach to risk analysis and decision-making, providing companies with vital information for financial management under uncertainty. The article emphasizes that the use of Monte Carlo simulation in financial management not only enhances the effectiveness of risk management, but also supports the long-term growth of corporate value. The entire process of financial management moves into the future and is based on predicting future free cash flows discounted at the cost of capital. We used both numerical and analytical methods to solve verdict-type paradoxes. We used Monte Carlo simulation as the numerical method. The following analytical methods were used: conditional probability, Bayes' rule and Bayes' rule with multiple conditions. We solved all truth-type paradoxes and discovered why the Monty Hall problem was so widely discussed in the 1990s. We differentiated Monty Hall problems using different numbers of doors and prizes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Monte Carlo Simulation in Treasury Management

3. Veridical Type Paradoxes

3.1. Bertrand's Box

- a box containing two gold coins

- a box containing two silver coins

- a box containing one gold coin and one silver coin

3.2. Three Prisoners Dilemma

- A,B, and C are corresponding prisoners

- P(A),P(B),P(C) are probabilities that governor pardoned corresponding prisoners

- a,b,c are events in which the warden mentions that corresponding prisoners were pardoned

3.3. Monty Hall Problem

- is host opening door 3.

- 4.

- Switching decision

- 5.

- Flip a coin decision

- 6.

- Tic-toc decision

- 7.

- Opposite tic-toc decision

4. Conclusions

Funding

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate, and Consent for Publication

References

- Adamolekun G. (2024), Firm biodiversity risk, climate vulnerabilities, and bankruptcy risk, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 97, art. no. 102075. [CrossRef]

- Adil M.H., Roy A. (2024), Asymmetric effects of uncertainty on investment: Empirical evidence from India, Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 29, art. no. e00359. [CrossRef]

- Ajovalasit S., Consiglio A., Provenzano D. (2024), Debt Sustainability in the Context of Population Ageing: A Risk Management Approach, Risks, 12 (12), art. no. 188. [CrossRef]

- Akgün A.İ., Memiş Karataş A. (2024), Do impact of cash flows and working capital ratios on performance of listed firms during the crisis? The cases of EU-28 and Western European countries, Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar T. (2022), Corporate governance, excess-cash and firm value: Evidence from ASEAN-5, Economics and Business Review, 8 (4), pp. 39 - 67. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar T. (2024), Are the motives of holding cash differing between developed and emerging financial markets?, Kybernetes, 53 (5), pp. 1653 - 1681. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar T., Chen L., Tareq M.A. (2024), Blockchain technology enterprises’ ownership structure and cash holdings, Sustainable Futures, 8, art. no. 100229. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar T., Qasem A., Khan S. (2024), Internal corporate governance and cash holdings: the role of external governance mechanism, International Journal of Disclosure and Governance. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar T., Tareq M.A., Sakti M.R.P., Khan A.A. (2018), Corporate governance and cash holdings: the way forward, Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 10 (2), pp. 152 - 170. [CrossRef]

- Alam M.S., Safiullah M., Islam M.S. (2024), Cash-rich firms and carbon emissions, International Review of Financial Analysis, 81, art. no. 102106. [CrossRef]

- Alban A., Darji H.A., Imamura A., Nakayama M.K. (2017), Efficient Monte Carlo methods for estimating failure probabilities, Reliability Engineering and System Safety, 165, pp. 376 - 394. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamshary F.S.A.A., Mohamad Ariff A., Kamarudin K.A., Abd Majid N. (2025), Corporate risk-taking, financial constraints and cash holdings: evidence from Saudi Arabia, International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 18 (1), pp. 166 - 183. [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi M. (2021), Bank Capital Adequacy: The Impact Of Fundamental And Regulatory Factors In A Developing Country, Journal of Applied Business Research, 37 (6), pp. 205 - 216.

- Arnold U., Yildiz Ö. (2015), Economic risk analysis of decentralized renewable energy infrastructures - A Monte Carlo Simulation approach, Renewable Energy, 77 (1), pp. 227 - 239. [CrossRef]

- Athari S.A., Cho Teneng R., Çetinkaya B., Bahreini M. (2024), Country risk, global uncertainty, and firms’ cash holdings: Do the role of law, culture, and financial market development matter?, Heliyon, 10 (5), art. no. e26266. [CrossRef]

- Austin P.C. (2009), Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples, Statistics in Medicine, 28 (25), pp. 3083 - 3107. [CrossRef]

- Austin P.C. (2009), Some methods of propensity-score matching had superior performance to others: results of an empirical investigation and monte carlo simulations, Biometrical Journal, 51 (1), pp. 171 - 184. [CrossRef]

- Batan L.Y., Graff G.D., Bradley T.H. (2016), Techno-economic and Monte Carlo probabilistic analysis of microalgae biofuel production system, Bioresource Technology, 219, pp. 45 - 52. [CrossRef]

- Behera M., Mahakud J. (2025), Geopolitical risk and cash holdings: evidence from an emerging economy, Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 17 (1), pp. 132 - 156. [CrossRef]

- Belas J., Dvorsky J., Hlawiczka R., Smrcka L., Khan K.A. (2024), SMEs sustainability: The role of human resource management, corporate social responsibility and financial management, Oeconomia Copernicana, 15 (1), pp. 307 - 342. [CrossRef]

- Belas J., Gavurova B., Kubak M., Novotna A. (2023), RISK MANAGEMENT LEVEL DETERMINANTS IN VISEGRAD COUNTRIES – SECTORAL ANALYSIS, Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 29 (1), pp. 307 - 325. [CrossRef]

- Belas J., Gavurova B., Kubak M., Rowland Z. (2024), Quantifying Export Potential and Barriers of SMEs in V4, Acta Polytechnica Hungarica, 21 (2), pp. 251 - 270. [CrossRef]

- Brandimarte P. (2014), Handbook in Monte Carlo Simulation: Applications in Financial Engineering, Risk Management, and Economics, Handbook in Monte Carlo Simulation: Applications in Financial Engineering, Risk Management, and Economics, pp. 1 - 662. [CrossRef]

- Cao D., Tahir S.H., Rizvi S.M.R., Khan K.B. (2024), Exploring the influence of women's leadership and corporate governance on operational liquidity: The glass cliff effect, PLoS ONE, 19 (5 May), art. no. e0302210. [CrossRef]

- Carrick J. (2023) Navigating the path from innovation to commercialization: A review of technology-based academic entrepreneurship, Journal of Applied Business Research, 39 (1), pp. 1 - 14.

- Carsey T., J. Harden (2014), Monte Carlo Simulation and Resampling Methods for Social Science, SAGE Publications, London.

- Chen S., Farooq U., Aldawsari S.H., Waked S.S., Badawi M. (2025), Impact of environmental, social, and governance performance on cash holdings in BRICS: Mediating role of cost of capital, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 32 (1), pp. 1182 - 1197. [CrossRef]

- Chen X., Yu W., Zhao Y. (2020) Financial risk management and control based on marine economic forecast, Journal of Coastal Research, 112 (sp1), pp. 234 - 236. [CrossRef]

- Chung H.J., Jhang H., Ryu D. (2023), Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on corporate cash holdings: Evidence from Korea, Emerging Markets Review, 56, art. no. 101055. [CrossRef]

- Crouhy M., Galai D., Mark R. (2000), A comparative analysis of current credit risk models, Journal of Banking and Finance, 24 (1-2), pp. 59 - 117. [CrossRef]

- Cui F., Tan Y., Lu B. (2024), How Do Macroeconomic Cycles and Government Policies Influence Cash Holdings? Evidence from Listed Firms in China, Sustainability (Switzerland), 16 (18), art. no. 7961. [CrossRef]

- da Costa Moraes M.B., Manoel A.A.S., Carneiro J. (2025), Determinants of corporate cash holdings in private and public companies: insights from Latin America, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting. [CrossRef]

- Das B.C., Hasan F., Sutradhar S.R. (2024), The impact of economic policy uncertainty and inflation risk on corporate cash holdings, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 62 (3), pp. 865 - 887. [CrossRef]

- Demiraj R., Labadze L., Dsouza S., Demiraj E., Grigolia M. (2024), The quest for an optimal capital structure: an empirical analysis of European firms using GMM regression analysis, EuroMed Journal of Business. [CrossRef]

- Di L., Jiang W., Mao J., Zeng Y. (2024), Managing liquidity along the supply chain: Supplier-base concentration and corporate cash policy, European Financial Management, 30 (4), pp. 2376 - 2421. [CrossRef]

- Diebold F.X., Gunther T.A., Tay A.S. (1998), Evaluating density forecasts with applications to financial risk management, International Economic Review, 39 (4), pp. 863 - 883. [CrossRef]

- Diebold F.X., Hahn J., Tay A.S. (1999) Multivariate density forecast evaluation and calibration in financial risk management: High-frequency returns on foreign exchange, Review of Economics and Statistics, 81 (4), pp. 661 - 673. [CrossRef]

- Ding S., Wang A., Cui T., Min Du A. (2025), Renaissance of Climate Policy Uncertainty: The Effects of U.S. Presidential Election on Energy Markets Volatility, International Review of Economics & Finance. [CrossRef]

- Dsouza S., Momin M., Habibniya H., Tripathy N.(2024), Optimizing performance through sustainability: the mediating influence of firm liquidity on ESG efficacy in African enterprises, Cogent Business and Management, 11 (1), art. no. 2423273. [CrossRef]

- Elamer A.A., Utham V. (2024), Cash is queen? Impact of gender-diverse boards on firms' cash holdings during COVID-19, International Review of Financial Analysis, 95, art. no. 103490. [CrossRef]

- Elroukh A.W. (2025), The Asymmetric Impact of Economic Policy Uncertainty on the Demand for Money in the GCC Countries, International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues , 15 (1), pp. 93 - 100. [CrossRef]

- Elyasiani E., Movaghari H. (2024), Money demand function with time-varying coefficients, Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 98, art. no. 101914. [CrossRef]

- Fan J., Wang K., Xu M. (2024), Does digital finance development affect corporate cash holdings? Evidence from China, Technology Analysis and Strategic Management. [CrossRef]

- Fang S., Deitch M., Gebremicael T., Angelini C., Ortals C. (2024), Identifying critical source areas of non-point source pollution to enhance water quality: Integrated SWAT modeling and multi-variable statistical analysis to reveal key variables and thresholds, Water Research, 253, doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2024.121286.

- Fantazzini D. (2009), The effects of misspecified marginals and copulas on computing the value at risk: A Monte Carlo study, Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 53 (6), pp. 2168 - 2188. [CrossRef]

- Farooq U., Thavorn J., Tabash M.I. (2024), Exploring the impact of environmental regulations and green innovation on corporate investment and cash management: evidence from Asian economies, China Finance Review International. [CrossRef]

- Floros C., Galariotis E., Gkillas K., Magerakis E., Zopounidis C. (2024), Time-varying firm cash holding and economic policy uncertainty nexus: a quantile regression approach, Annals of Operations Research, 341 (2-3), pp. 859 - 895. [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh A.M.O. (2023), The Determinants of Capital Adequacy in the Jordanian Banking Sector: An Autoregressive Distributed Lag-Bound Testing Approach, International Journal of Financial Studies, 11 (2), art. no. 75. [CrossRef]

- Guo H., Polak P. (2021), Artificial Intelligence and Financial Technology FinTech: How AI Is Being Used Under the Pandemic in 2020, Studies in Computational Intelligence, 935, pp. 169 - 186. [CrossRef]

- Hasan M.M., Habib A., Zhao R. (2022), Corporate reputation risk and cash holdings, Accounting and Finance, 62 (1), pp. 667 - 707. [CrossRef]

- Hasan S.B., Alam M.S., Paramati S.R., Islam M.S. (2022), Does firm-level political risk affect cash holdings?, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 59 (1), pp. 311 - 337. [CrossRef]

- Hong L.J., Hu Z., Liu G. (2014), Monte carlo methods for value-at-risk and conditional value-at-risk: A review, ACM Transactions on Modeling and Computer Simulation, 24 (4), art. no. 5. [CrossRef]

- Hung N.T., Su Dinh T. (2022), Threshold effect of working capital management on firm profitability: evidence from Vietnam, Cogent Business and Management, 9 (1), art. no. 2141090. [CrossRef]

- Hwang J.-T., Wen M. (2024), Electronic payments and money demand in China, Economic Analysis and Policy, 82, pp. 47 - 64. [CrossRef]

- İnal V. (2024), On the Relationship between the Money Rate of Interest and Aggregate Investment Spending, Review of Radical Political Economics, 56 (2), pp. 300 - 318. [CrossRef]

- Jajuga K. (2023), Data Analysis for Risk Management—Economics, Finance and Business: New Developments and Challenges, Risks, 11 (4), art. no. 70. [CrossRef]

- Jinkrawee J., Lonkani R., Suwanaphan S. (2023), A matter of others' money: How cash holdings of other firms affect a firm’s cash holding?, International Journal of Emerging Markets, 18 (10), pp. 3954 - 3972. [CrossRef]

- Kalash I. (2024), How does excess cash affect corporate financial performance?, Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 25 (5), pp. 1223 - 1243. [CrossRef]

- Kayani U., Hasan F., Choudhury T., Nawaz F. (2025), Unveiling WCM and firm performance relationship: evidence from Shariah compliance United Kingdom firms, International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management. [CrossRef]

- Kazak H., Mensi W., Akif Gunduz M., Kilicarslan A. (2025), Connections between gold, main agricultural commodities, and Turkish stock markets, Borsa Istanbul Review. [CrossRef]

- Koller D., N. Friedman (2009), Probabilistic Graphical Models Principles and Techniques, The MIT Press, London.

- Kumar N., Symss J. (2024), Corporate cash holding and firm’s performance in times of Ukraine war: a literature review and way forward, Journal of Chinese Economic and Foreign Trade Studies. [CrossRef]

- Lara-Galera A., Alcaraz-Carrillo de Albornoz V., Molina-Millán J., Muñoz-Medina B. (2025), Spread valuation and risk on transport infrastructure loans, Economics of Transportation, 41. [CrossRef]

- Le Maux J., Smaili N. (2021), Annual report readability and corporate bankruptcy, Journal of Applied Business Research, 37 (3), pp. 73 - 80.

- Lee J. (2024), Corporate cash holdings and industry risk, Journal of Financial Research, 47 (2), pp. 435 - 470. [CrossRef]

- Li X., Pan Z., Ho K.-C., Bo Y. (2024), Epidemics, local institutional quality, and corporate cash holdings, International Review of Economics and Finance, 92, pp. 193 - 210. [CrossRef]

- Li X., Shiu Y.-M. (2024), The Effect of Risk Management on Direct and Indirect Capital Structure Deviations, Risks, 12 (12), art. no. 186. [CrossRef]

- Liu J., Cheng Y., Li X., Sriboonchitta S. (2022), The Role of Risk Forecast and Risk Tolerance in Portfolio Management: A Case Study of the Chinese Financial Sector, Axioms, 11 (3), art. no. 134. [CrossRef]

- Liu L. (2024), Litigation risk and corporate cash holdings: The moderating effect of CEO tenure, Finance Research Letters, 69, art. no. 106211. [CrossRef]

- Liu L., Cowan L., Wang F., Onega T. (2025), A multi-constraint Monte Carlo Simulation approach to downscaling cancer data, Health & Place, 91. [CrossRef]

- Luo P., Liu X. (2024), Dynamic investment in new technology and risk management, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting. [CrossRef]

- Mamani J.C.M., Carrasco-Choque F., Paredes-Calatayud E.F., Cusilayme-Barrantes H., Cahuana-Lipa R. (2024), Modeling Uncertainty Energy Price Based on Interval Optimization and Energy Management in the Electrical Grid, Operations Research Forum, 5 (1), art. no. 4. [CrossRef]

- Mertzanis C., Hamill P.A., Pavlopoulos A., Houcine A. (2024), Sustainable investment conditions and corporate cash holdings in the MENA region: Market preparedness and Shari'ah-compliant funds, International Review of Economics and Finance, 93, pp. 1043 - 1063. [CrossRef]

- Metwally A.B.M., Aly S.A.S., Ali M.A.S. (2024), The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Cash Holdings: The Moderating Role of Board Gender Diversity, International Journal of Financial Studies, 12 (4), art. no. 104. [CrossRef]

- Movaghari H., Sermpinis G. (2025), Heterogeneous impact of cost of carry on corporate money demand, European Financial Management, 31 (1), pp. 400 - 426. [CrossRef]

- Nießner T., Nießner S., Schumann M. (2022), Influence of Corporate Industry Affiliation in Financial Business Forecasting: A Data Analysis Concerning Competition, 28th Americas Conference on Information Systems, AMCIS 2022.

- Nießner T., Nießner S., Schumann M. (2023), Is It Worth the Effort? Considerations on Text Mining in AI-Based Corporate Failure Prediction, Information (Switzerland), 14 (4), art. no. 215. [CrossRef]

- Nishibe T., Iwasa T., Matsuda S., Kano M. (2025), Prediction of Aneurysm Sac Shrinkage After Endovascular Aortic Repair Using Machine Learning-Based Decision Tree Analysis, Journal of Surgical Research, 306, 197-202, doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2024.11.049.

- Nusair S.A., Olson D., Al-Khasawneh J.A. (2024), Asymmetric effects of economic policy uncertainty on demand for money in developed countries, Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 29, art. no. e00350. [CrossRef]

- Oh S., Lim C., Lee B. (2025), Stochastic scaling of the time step length in a full-scale Monte Carlo Potts model, Computational Materials Science, 249, doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2024.113644.

- Ortmann A., Spiliopoulos L. (2023) Ecological rationality and economics: where the Twain shall meet, Synthese, 201 (4), art. no. 135. [CrossRef]

- Page S. (2010), Diversity and Complexity. Princeton University Press, Woodstock 2010.

- Pang J., Wang K., Zhao L. (2024), Tax enforcement and corporate cash holdings, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 51 (9-10), pp. 2737 - 2762. [CrossRef]

- Park J. (2022), Impact Of Informal Communication On Corporate Creative Performance, Journal of Applied Business Research, 38 (1), pp. 19 - 28. [CrossRef]

- Pereira E.J.S., Pinho J.T., Galhardo M.A.B., Macêdo W.N. (2014), Methodology of risk analysis by Monte Carlo Method applied to power generation with renewable energy, Renewable Energy, 69, pp. 347 - 355. [CrossRef]

- Polak P., Masquelier F., Michalski G. (2018), Towards treasury 4.0/the evolving role of corporate treasury management for 2020, Management (Croatia), 23 (2), pp. 189 - 197. [CrossRef]

- Puri I. (2025), Simplicity and Risk, Journal of Finance. [CrossRef]

- Rajesh Banu J., Preethi, Kavitha S., Gunasekaran M., Kumar G. (2020), Microalgae based biorefinery promoting circular bioeconomy-techno economic and life-cycle analysis, Bioresource Technology, 302, art. no. 122822. [CrossRef]

- Rehan R. (2022), Investigating the capital structure determinants of energy firms, Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology, 6 (1), pp. 1 - 14. [CrossRef]

- Rehan R., Khan M.A., Fu G.H., Sa’ad A.A., Irshad A. (2024), The Determinants of Shariah Banks’ Capital Structure, International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues , 14 (5), pp. 193 - 202. [CrossRef]

- Rehan R., Sa’ad A.A., Fu G.H., Khan M.A. (2024), The determinants of banks' capital structure in SAARC economies, Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology, 8 (4), pp. 417 - 433. [CrossRef]

- Rehman I.U., Shahzad F., Hanif M.A., Khalid N., Nawaz F. (2024), From commitment to capital: does environmental innovation reduce corporate cash holdings?, Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment. [CrossRef]

- Reyes J.E.M., Pérez J.J.C., Aké S.C. (2023), Credit risk management analysis: An application of fuzzy theory to forecast the probability of default in a financial institution [Análisis de la gestión del riesgo de crédito: una aplicación de la teoría difusa para pronosticar la probabilidad de incumplimiento en una institución financiera], Contaduria y Administracion, 69 (1), pp. 180 - 211. [CrossRef]

- Rijanto A. (2022), Political connection status decisions and benefits for firms experiencing financial difficulties in emerging markets, Problems and Perspectives in Management, 20 (3), pp. 164 - 177. [CrossRef]

- Sabripoor A., Ghousi R. (2024), Risk-based cooperative vehicle routing problem for cash-in-transit scenarios: A hybrid optimization approach, International Journal of Industrial Engineering Computations, 15 (1), pp. 127 - 148. [CrossRef]

- Salas V., Saurina J. (2002), Credit risk in two institutional regimes: Spanish commercial and savings banks, Journal of Financial Services Research, 22 (3), pp. 203 - 224. [CrossRef]

- Schrand C., Unal H. (1998), Hedging and coordinated risk management: Evidence from thrift conversions, Journal of Finance, 53 (3), pp. 979 - 1013. [CrossRef]

- Song K., Lee Y. (2012), Long-term effects of a financial crisis: Evidence from cash holdings of East Asian firms, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 47 (3), pp. 617 - 641. [CrossRef]

- Steffen B. (2018), The importance of project finance for renewable energy projects, Energy Economics, 69, pp. 280 - 294. [CrossRef]

- Stewart J. (2005), Fiscal incentives, corporate structure and financial aspects of treasury management operation, Accounting Forum, 29 (3 SPEC. ISS.), pp. 271 - 288. [CrossRef]

- Taylor J.W., Yu K. (2016), Using auto-regressive logit models to forecast the exceedance probability for financial risk management, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A: Statistics in Society, 179 (4), pp. 1069 - 1092. [CrossRef]

- Tobisova A., Senova A., Rozenberg R. (2022), Model for Sustainable Financial Planning and Investment Financing Using Monte Carlo Method, Sustainability (Switzerland), 14 (14), art. no. 8785. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi V., Madhavan V. (2024), Firm Value Evidence from India, Economic and Political Weekly, 59 (21), pp. 83 - 90.

- Varela A., Dopico D., Fernández A. (2025), An analytical approach to the sensitivity analysis of semi-recursive ODE formulations for multibody dynamics, Computers & Structures, 308, doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2024.107642.

- Vasquez J.Z., Cruz L.D.C.S.S., Navarro L.R.R., Benavides A.M.V., López R.D.J.T., Rodriguez V.H.P. (2023), RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INTERNAL CONTROL AND TREASURY MANAGEMENT IN A PERUVIAN MUNICIPALITY, Journal of Law and Sustainable Development, 11 (2), art. no. e0706. [CrossRef]

- Vega-Gutiérrez P.L., López-Iturriaga F.J., Rodríguez-Sanz J.A. (2025), Economic policy uncertainty and capital structure in Europe: an agency approach, European Journal of Finance, 31 (1), pp. 53 - 75. [CrossRef]

- Vithayasrichareon P., MacGill I.F. (2012), A Monte Carlo based decision-support tool for assessing generation portfolios in future carbon constrained electricity industries, Energy Policy, 41, pp. 374 - 392. [CrossRef]

- von Solms J., Langerman J. (2022), Digital technology adoption in a bank Treasury and performing a Digital Maturity Assessment, African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 14 (2), pp. 302 - 315. [CrossRef]

- Wang X., Li L., Bian S. (2024), Irrelevant answers in customers’ earnings communication conferences and suppliers’ cash holdings, Journal of Financial Stability, 75, art. no. 101346. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z., Zhang C., Wu R., Sha L. (2024), From ethics to efficiency: Understanding the interconnected dynamics of ESG performance, financial efficiency, and cash holdings in China, Finance Research Letters, 64, art. no. 105419. [CrossRef]

- Worku Z. (2021), Business ethics and the repayment of loans in small enterprises, Journal of Applied Business Research, 37 (2), pp. 51 - 60.

- Wu J., Al-Khateeb F.B., Teng J.-T., Cárdenas-Barrón L.E. (2016), Inventory models for deteriorating items with maximum lifetime under downstream partial trade credits to credit-risk customers by discounted cash-flow analysis, International Journal of Production Economics, 171, pp. 105 - 115. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto T., Sakamoto H. (2025), Monte Carlo methods based on “virtual density” theory for calculation of k-eigenvalue sensitivity under nonuniform anisotropic deformation, Annals of Nuclear Energy, 213, doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2024.111181.

- Yang J., Bao M., Chen S. (2025), A retreat to safety: Why COVID-19 make firms more risk-averse?, International Review of Financial Analysis, 97, art. no. 103789. [CrossRef]

- Yang S.H., Jun S.-G. (2022), Owners Of Korean Conglomerates And Corporate Investment, Journal of Applied Business Research, 38 (1), pp. 1 - 18. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y., Lei J. (2025), Analysis of coupled distributed stochastic approximation for misspecified optimization, Neurocomputing. [CrossRef]

- Yitzhaky L., Bahli B. (2021), Target setting and firm performance: A review, Journal of Applied Business Research, 37 (3), pp. 81 - 94.

- Yudaruddin R., Lesmana D., Yudaruddin Y.A., Ekşi̇ İ.H., Başar B.D. (2024), Impact of the Israel–Hamas conflict on financial markets of MENA region – a study on investors’ reaction, Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L., Gao J. (2024), Does climate policy uncertainty influence corporate cash holdings? Evidence from the U.S. tourism and hospitality sector, Tourism Economics, 30 (7), pp. 1704 - 1728. [CrossRef]

- Zvarikova K., Dvorsky J., Belas J., Jr., Metzker Z. (2024), MODEL OF SUSTAINABILITY OF SMEs IN V4 COUNTRIES, Journal of Business Economics and Management, 25 (2), pp. 226 - 245. [CrossRef]

| No | Door | Prize | Changep | Ttp | Flipp | Ottp | No changep |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 66.645 | 55.585 | 50.061 | 44.415 | 33.355 |

| 2 | 4 | 1 | 37.545 | 31.857 | 31.278 | 30.005 | 24.992 |

| 3 | 4 | 2 | 75 | 66.686 | 62.54 | 60.013 | 49.993 |

| 4 | 5 | 1 | 26.704 | 23.5 | 23.35 | 22.854 | 19.979 |

| 5 | 5 | 2 | 53.287 | 47.463 | 46.657 | 45.705 | 40.047 |

| 6 | 5 | 3 | 80.014 | 73.354 | 69.997 | 68.534 | 59.99 |

| 7 | 6 | 1 | 20.86 | 18.802 | 18.791 | 18.505 | 16.649 |

| 8 | 6 | 2 | 41.67 | 37.76 | 37.493 | 37.015 | 33.303 |

| 9 | 6 | 3 | 62.565 | 57.244 | 56.253 | 55.6 | 50.053 |

| 10 | 6 | 4 | 83.273 | 77.724 | 75.042 | 74.074 | 66.719 |

| 11 | 7 | 1 | 17.155 | 15.756 | 15.767 | 15.591 | 14.286 |

| 12 | 7 | 2 | 34.268 | 31.582 | 31.477 | 31.138 | 28.581 |

| 13 | 7 | 3 | 51.457 | 47.512 | 47.114 | 46.796 | 42.892 |

| 14 | 7 | 4 | 68.592 | 63.727 | 62.917 | 62.387 | 57.163 |

| 15 | 7 | 5 | 85.661 | 80.856 | 78.553 | 77.89 | 71.399 |

| 16 | 8 | 1 | 14.564 | 13.591 | 13.562 | 13.408 | 12.49 |

| 17 | 8 | 2 | 29.171 | 27.15 | 27.097 | 26.916 | 25.009 |

| 18 | 8 | 3 | 43.77 | 40.764 | 40.609 | 40.408 | 37.492 |

| 19 | 8 | 4 | 58.368 | 54.537 | 54.252 | 53.886 | 49.989 |

| 20 | 8 | 5 | 72.953 | 68.614 | 67.716 | 67.327 | 62.504 |

| 21 | 8 | 6 | 87.511 | 83.353 | 81.251 | 80.743 | 74.955 |

| 22 | 9 | 1 | 12.709 | 11.932 | 11.919 | 11.793 | 11.063 |

| 23 | 9 | 2 | 25.378 | 23.882 | 23.85 | 23.712 | 22.286 |

| 24 | 9 | 3 | 38.05 | 35.79 | 35.62 | 35.541 | 33.302 |

| 25 | 9 | 4 | 50.793 | 47.765 | 47.603 | 47.438 | 44.429 |

| 26 | 9 | 5 | 63.514 | 59.971 | 59.574 | 59.209 | 55.543 |

| 27 | 9 | 6 | 76.224 | 72.26 | 71.459 | 71.043 | 66.624 |

| 28 | 9 | 7 | 88.856 | 85.161 | 83.35 | 82.965 | 77.803 |

| 29 | 10 | 1 | 11.263 | 10.659 | 10.663 | 10.589 | 9.974 |

| 30 | 10 | 2 | 22.496 | 21.287 | 21.273 | 21.272 | 20.021 |

| 31 | 10 | 3 | 33.796 | 31.901 | 31.856 | 31.801 | 29.957 |

| 32 | 10 | 4 | 44.983 | 42.591 | 42.497 | 42.38 | 40.009 |

| 33 | 10 | 5 | 56.281 | 53.328 | 53.151 | 52.905 | 49.971 |

| 34 | 10 | 6 | 67.475 | 64.136 | 63.734 | 63.504 | 59.945 |

| 35 | 10 | 7 | 78.761 | 75.157 | 74.413 | 74.125 | 69.99 |

| 36 | 10 | 8 | 90.008 | 86.636 | 84.967 | 84.669 | 79.949 |

| No | Door | Prize | Changep | No changep | No changep | Flipp | Flipp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monte Carlo | True | combined | |||||

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 66.645 | 33.355 | 33.333 | 50.061 | 49.989 |

| 2 | 4 | 1 | 37.545 | 24.992 | 25 | 31.278 | 31.273 |

| 3 | 4 | 2 | 75 | 49.993 | 50 | 62.54 | 62.5 |

| 4 | 5 | 1 | 26.704 | 19.979 | 20 | 23.35 | 23.352 |

| 5 | 5 | 2 | 53.287 | 40.047 | 40 | 46.657 | 46.644 |

| 6 | 5 | 3 | 80.014 | 59.99 | 60 | 69.997 | 70.007 |

| 7 | 6 | 1 | 20.86 | 16.649 | 16.667 | 18.791 | 18.764 |

| 8 | 6 | 2 | 41.67 | 33.303 | 33.333 | 37.493 | 37.502 |

| 9 | 6 | 3 | 62.565 | 50.053 | 50 | 56.253 | 56.283 |

| 10 | 6 | 4 | 83.273 | 66.719 | 66.667 | 75.042 | 74.97 |

| 11 | 7 | 1 | 17.155 | 14.286 | 14.286 | 15.767 | 15.721 |

| 12 | 7 | 2 | 34.268 | 28.581 | 28.571 | 31.477 | 31.42 |

| 13 | 7 | 3 | 51.457 | 42.892 | 42.857 | 47.114 | 47.157 |

| 14 | 7 | 4 | 68.592 | 57.163 | 57.143 | 62.917 | 62.868 |

| 15 | 7 | 5 | 85.661 | 71.399 | 71.429 | 78.553 | 78.545 |

| 16 | 8 | 1 | 14.564 | 12.49 | 12.5 | 13.562 | 13.532 |

| 17 | 8 | 2 | 29.171 | 25.009 | 25 | 27.097 | 27.086 |

| 18 | 8 | 3 | 43.77 | 37.492 | 37.5 | 40.609 | 40.635 |

| 19 | 8 | 4 | 58.368 | 49.989 | 50 | 54.252 | 54.184 |

| 20 | 8 | 5 | 72.953 | 62.504 | 62.5 | 67.716 | 67.727 |

| 21 | 8 | 6 | 87.511 | 74.955 | 75 | 81.251 | 81.256 |

| 22 | 9 | 1 | 12.709 | 11.063 | 11.111 | 11.919 | 11.91 |

| 23 | 9 | 2 | 25.378 | 22.286 | 22.222 | 23.85 | 23.8 |

| 24 | 9 | 3 | 38.05 | 33.302 | 33.333 | 35.62 | 35.692 |

| 25 | 9 | 4 | 50.793 | 44.429 | 44.444 | 47.603 | 47.619 |

| 26 | 9 | 5 | 63.514 | 55.543 | 55.556 | 59.574 | 59.535 |

| 27 | 9 | 6 | 76.224 | 66.624 | 66.667 | 71.459 | 71.446 |

| 28 | 9 | 7 | 88.856 | 77.803 | 77.778 | 83.35 | 83.317 |

| 29 | 10 | 1 | 11.263 | 9.974 | 10 | 10.663 | 10.632 |

| 30 | 10 | 2 | 22.496 | 20.021 | 20 | 21.273 | 21.248 |

| 31 | 10 | 3 | 33.796 | 29.957 | 30 | 31.856 | 31.898 |

| 32 | 10 | 4 | 44.983 | 40.009 | 40 | 42.497 | 42.492 |

| 33 | 10 | 5 | 56.281 | 49.971 | 50 | 53.151 | 53.141 |

| 34 | 10 | 6 | 67.475 | 59.945 | 60 | 63.734 | 63.738 |

| 35 | 10 | 7 | 78.761 | 69.99 | 70 | 74.413 | 74.381 |

| 36 | 10 | 8 | 90.008 | 79.949 | 80 | 84.967 | 85.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).