Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

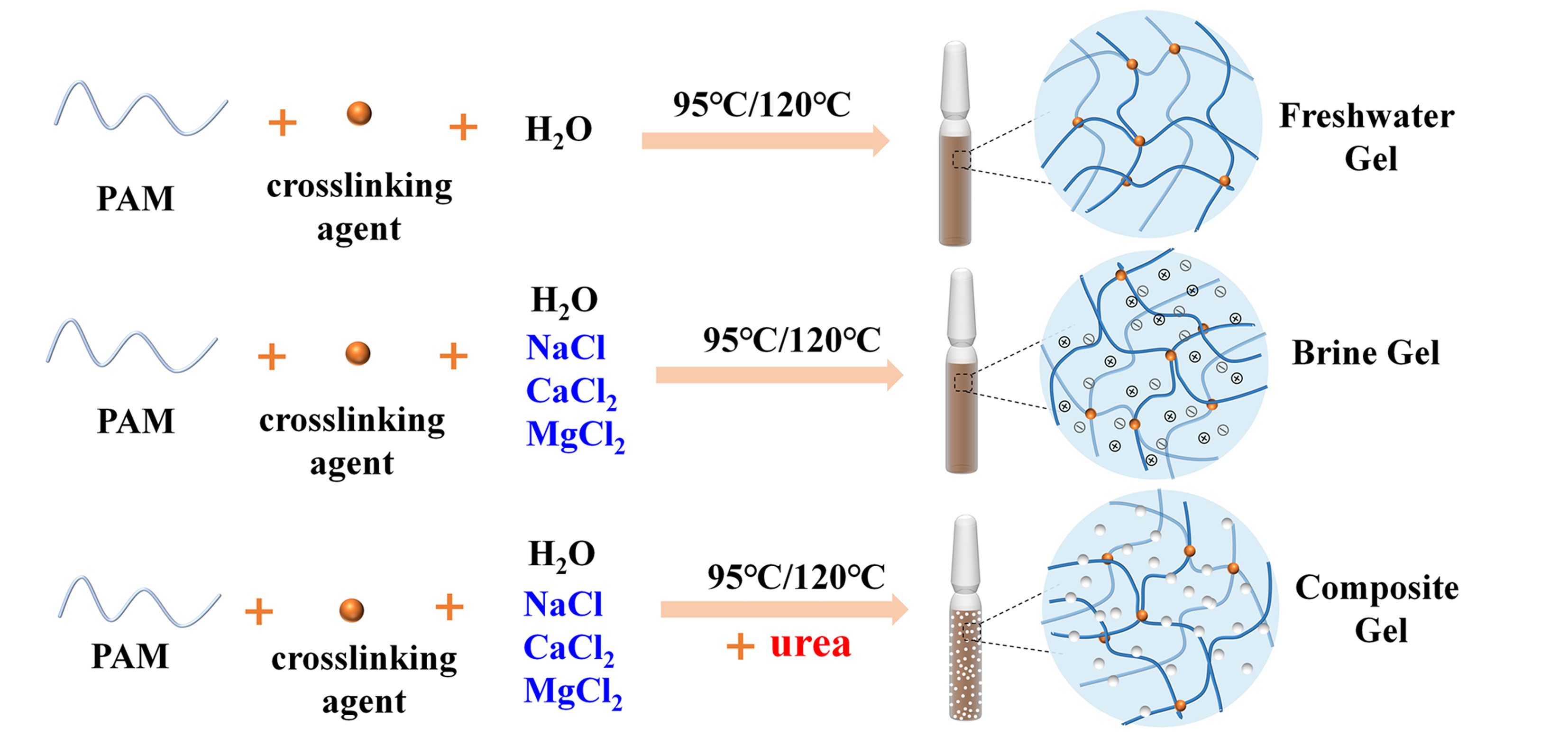

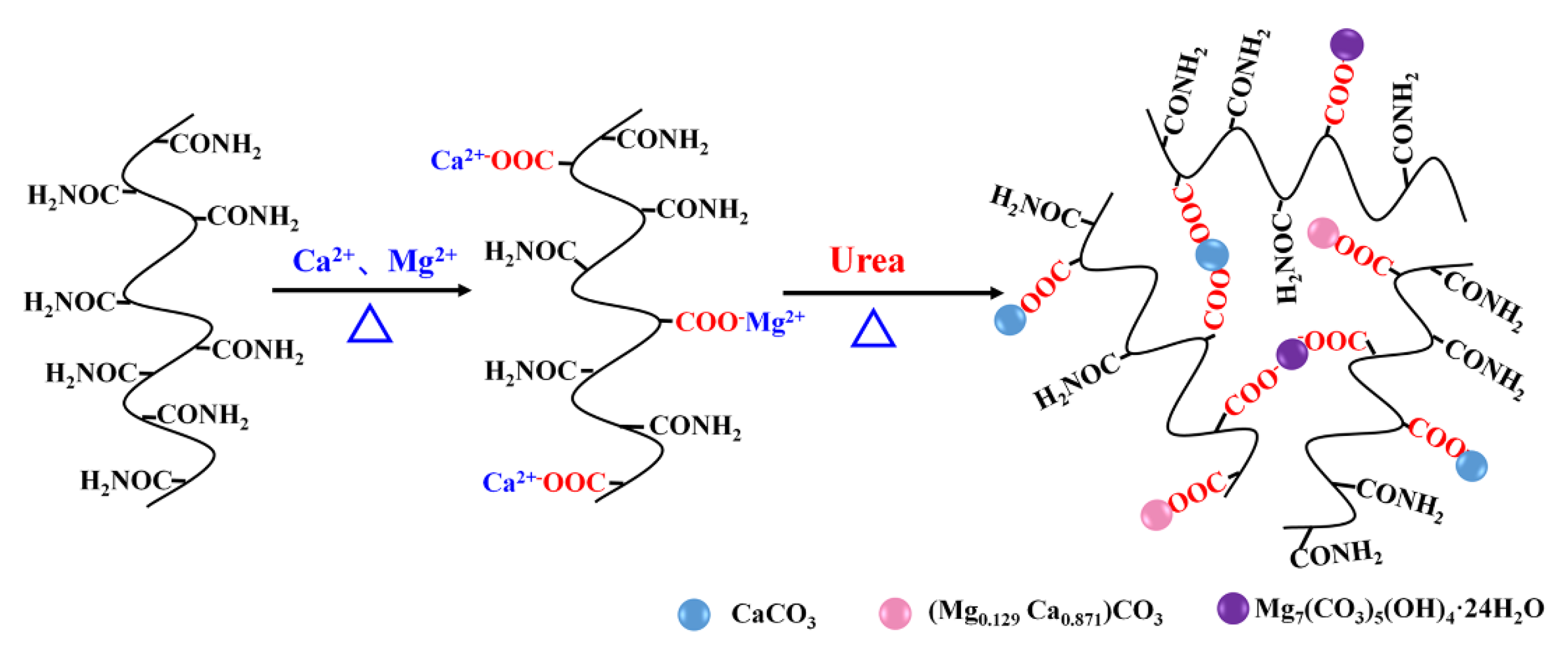

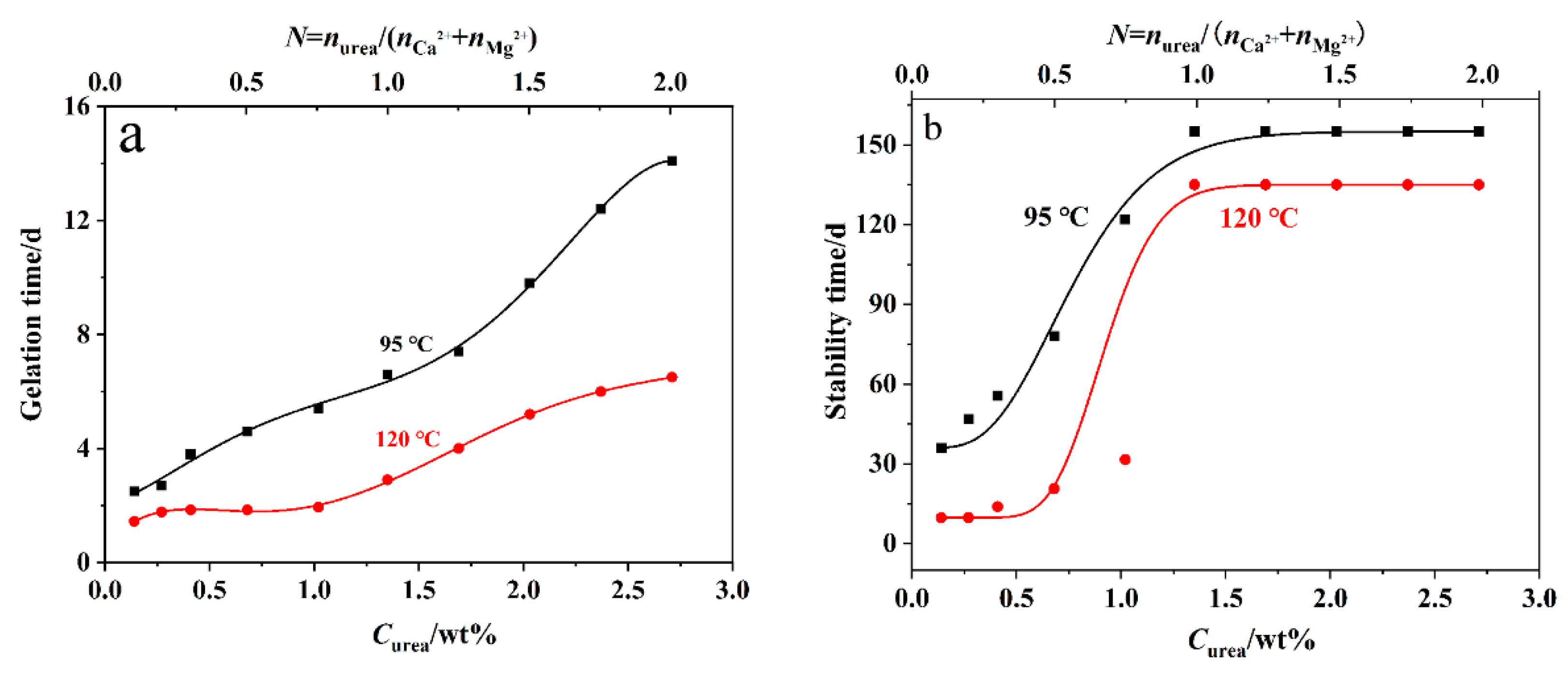

To address the rapid crosslinking reaction and short stability duration of polyacrylamide gel under high salinity and temperature conditions, this paper proposes the use of urea to delay the nucleophilic substitution crosslinking reaction among polyacrylamide, hydroquinone, and formaldehyde. At the same time, urea also regulates the precipitation of calcium and magnesium ions, enabling the in situ preparation of an organic/inorganic composite gel of crosslinked polyacrylamide and carbonate particles. With calcium and magnesium ion concentrations at 6817 mg/L and total salinity at 15×104 mg/L, the gelation time can be controlled to range from 6.6 to 14.1 days at 95 °C and from 2.9 to 6.5 days at 120 °C. The corresponding composite gel can remain stable for up to 155 days and 135 days, respectively. The delayed gelation facilitates longer-distance diffusion of the gelling agent into the formation, and the enhancements in gel strength and stability provide a solid foundation for improving the effectiveness of profile control and water shut-off in oilfields. This innovative approach promotes the comprehensive utilization of mineral resources within the formation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

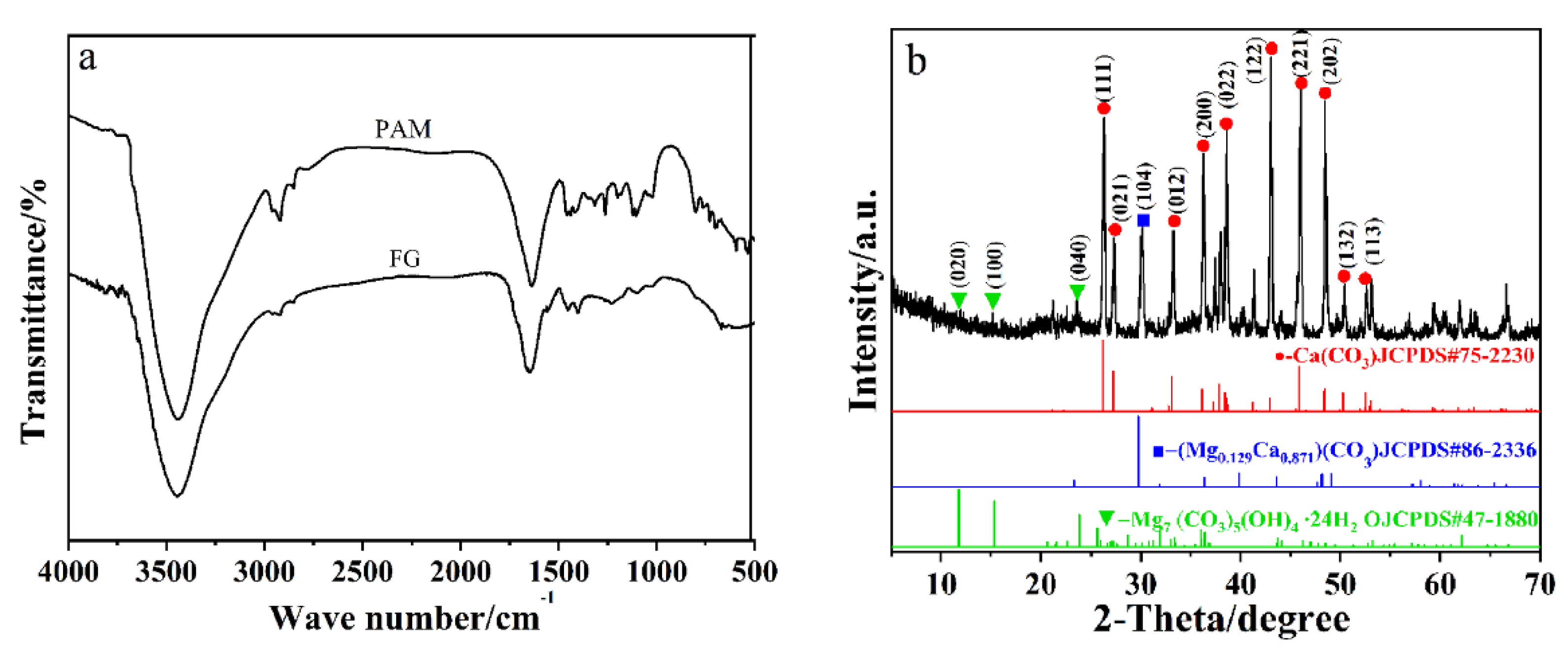

2.1. FT-IR and XRD

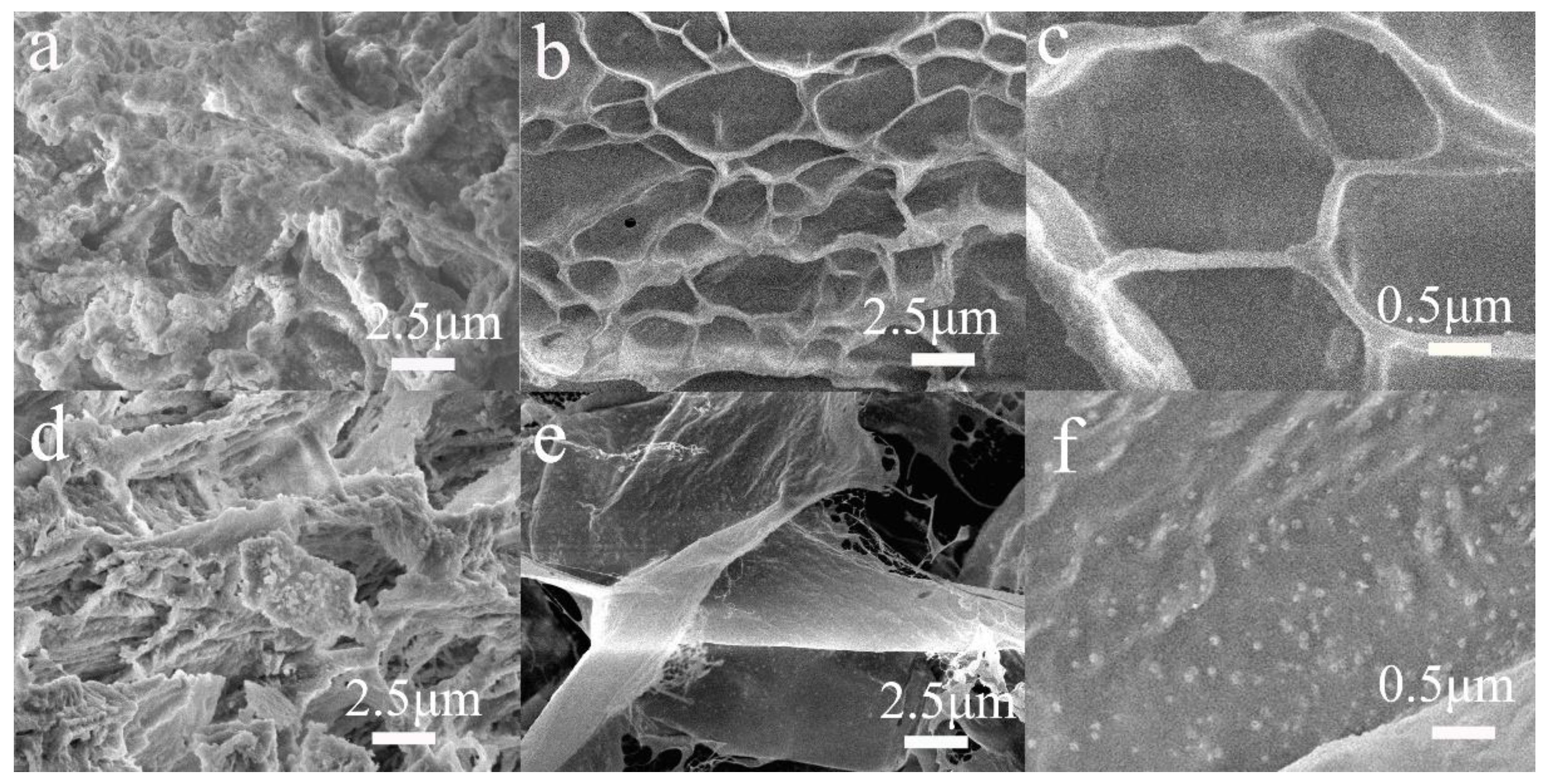

2.2. SEM

2.3. Gelation Performance

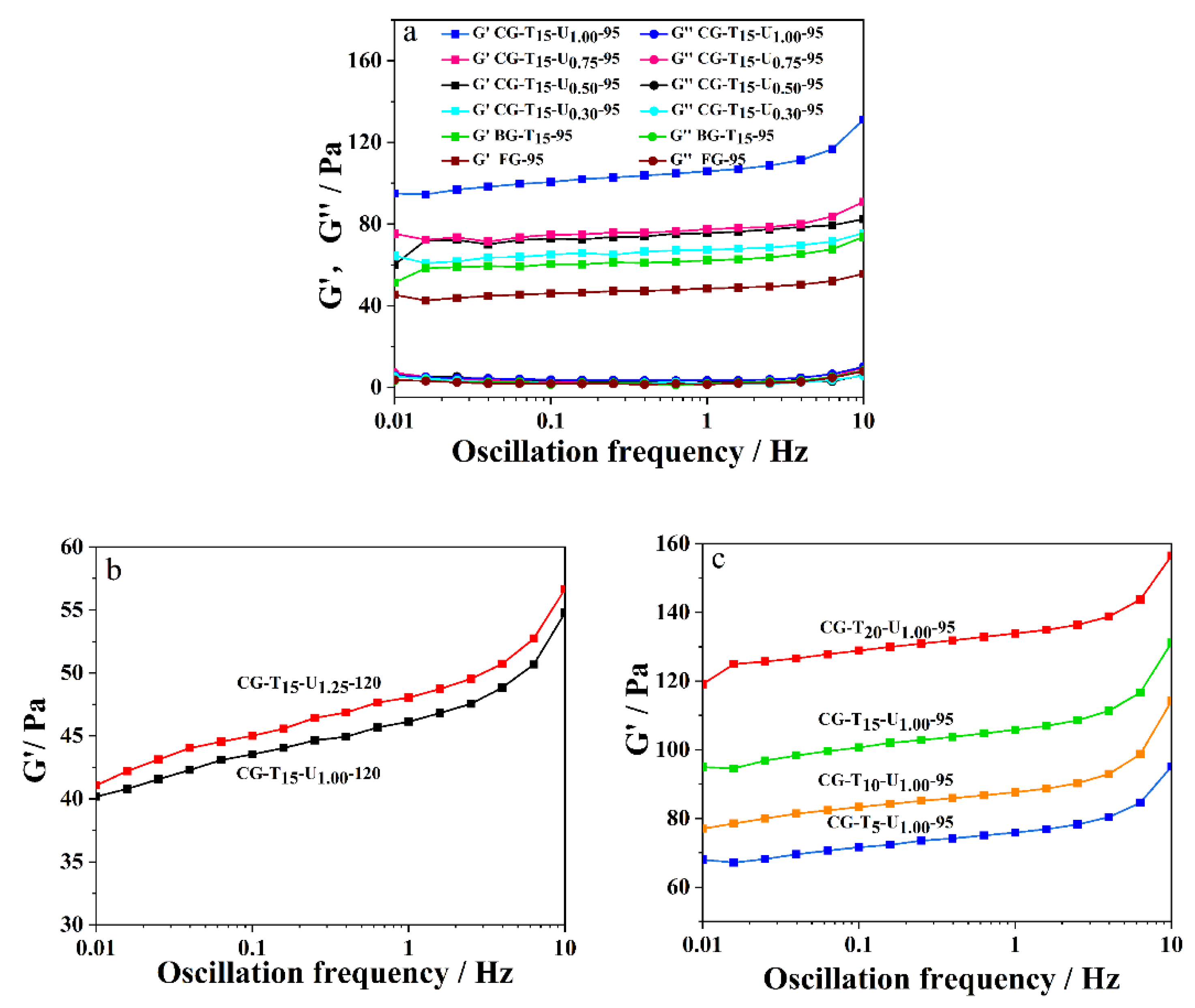

2.4. Dynamic Rheological Property

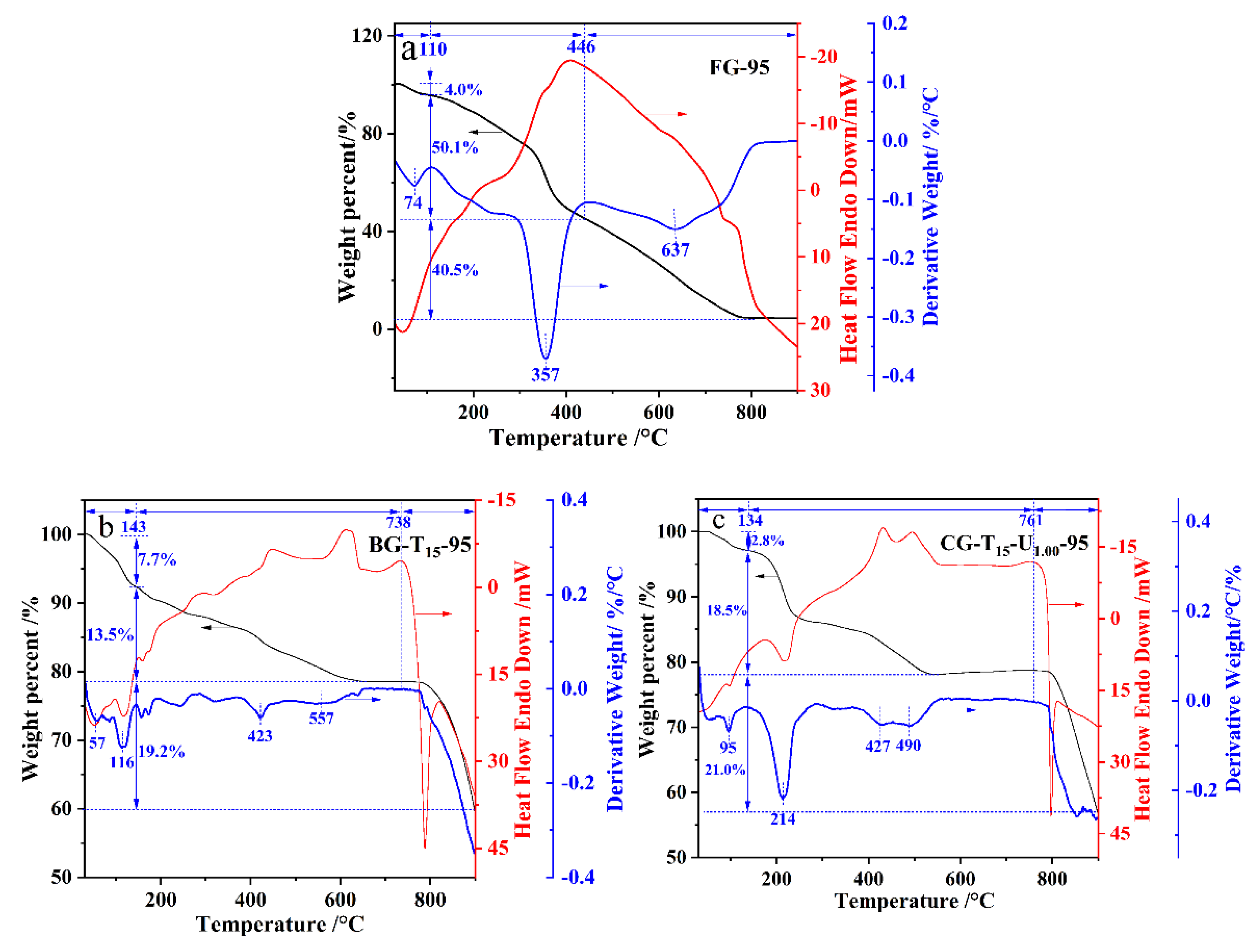

2.5. Thermal Stability

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Polyacrylamide Synthesis

4.3. Gel Sample Preparation

4.4. Structure Characterization and Morphology Observation

4.5. Gelation Performance Observation

4.6. Rheological Testing

4.7. Thermal Stability Testing

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moradi-Araghi, A. A review of thermally stable gels for fluid diversion in petroleum production. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2000, 26, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Naficy, S.; Brown, H.R.; Razal, J.M.; Spinks, G.M.; Whitten, P.G. Progress toward robust polymer hydrogels. Aust. J. Chem. 2011, 64, 1007-1025. [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Zhou, J.; Yin, M. A comprehensive review of polyacrylamide polymer gels for conformance control. Pet. Explor. Develop. 2015, 42, 525-532. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Bai, B.; Hou, J. Polymer gel systems for water management in high-temperature petroleum reservoirs: A chemical review. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 13063-13087. [CrossRef]

- Amir, Z.; Said, I.M.; Jan, B.M. In situ organically cross-linked polymer gel for high-temperature reservoir conformance control: A review. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2018, 30, 13-39. [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Kang, X.; Lashari, Z.A.; Li, Z.; Zhou, B.; Yang, H.; et al. Progress of polymer gels for conformance control in oilfield. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 289, 102363. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Lucero, D.; Martínez-Palou, R.; Palomeque-Santiago, J.F.; Vega-Paz, A.; Guzmán-Pantoja, J.; López-Falcón, D.A.; et al. Water control with gels based on synthetic polymers under extreme conditions in oil wells. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2022, 45, 998-1016. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, L.; Ge, J.; Jiang, P.; Zhu, X. Experimental research of syneresis mechanism of HPAM/Cr3+ gel. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2015, 483, 96-103. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Wei, F.; Li, W.; Liu, P.; Wu, Y.; Dai, M.; et al. Mechanism of polyacrylamide hydrogel instability on high-temperature conditions. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 10716-10724. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, B.; Sharma, V.P.; Udayabhanu, G. Gelation studies of an organically cross-linked polyacrylamide water shut-off gel system at different temperatures and pH. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2012, 81, 145-150. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhao, M.; Sun, N.; Meng, X.; Yang, Z.; Xie, Y.; et al. Delayed crosslinking gel fracturing fluid with dually crosslinked polymer network for ultra-deep reservoir: Performance and delayed crosslinking mechanism [J]. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 708, 135967. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhang, X.; He, L.; Zhao, G.; Dai, C. Experimental research of hydroquinone (HQ)/hexamethylene tetramine (HMTA) gel for water plugging treatments in high-temperature and high-salinity reservoirs. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 134, 43359. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, C.; Wang, K.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, G.; Yang, S.; et al. New insights into the hydroquinone (HQ)-hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA) gel system for water shut-off treatment in high temperature reservoirs. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2016, 35, 20-28. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Hou, J.; Wei, Q.; Wu, X.; Bai, B. Terpolymer gel system formed by resorcinol-hexamethylenetetramine for water management in extremely high-temperature reservoirs. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 1519-1528. [CrossRef]

- Bryant, S.L.; Bartosek, M.; Lockhart, T.P. Laboratory evaluation of phenol-formaldehyde/polymer gelants for high-temperature applications. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 1997, 17, 197-209. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yu, X.; Wang, L.; Qu, S.; Wu, W.; Ji, R.; et al. Nano-silica hybrid polyacrylamide/polyethylenimine gel for enhanced oil recovery at harsh conditions. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 633, 127898. [CrossRef]

- Tongwa, P.; Nygaard, R.; Bai, B. Evaluation of a nanocomposite hydrogel for water shut-off in enhanced oil recovery applications: design, synthesis, and characterization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 128, 787-794. [CrossRef]

- Michael, F.M.; Fathima, A.; AlYemni, E.; Jin, H.; Almohsin, A.; Alsharaeh, E.H. Enhanced polyacrylamide polymer gels using zirconium hydroxide nanoparticles for water shutoff at high temperatures: Thermal and rheological investigations. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 16347-16357. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, M.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Experimental investigation on the nanosilica-reinforcing polyacrylamide/polyethylenimine hydrogel for water shutoff treatment. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 6650-6656. [CrossRef]

- Azimi Dijvejin, Z.; Ghaffarkhah, A.; Sadeghnejad, S.; Vafaie Sefti, M. Effect of silica nanoparticle size on the mechanical strength and wellbore plugging performance of SPAM/chromium (III) acetate nanocomposite gels. Polym. J. 2019, 51, 693-707. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, C.; Wang, K.; Zou, C.; Gao, M.; Fang, Y.; et al. Study on a novel cross-linked polymer gel strengthened with silica nanoparticles. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 9152-9161. [CrossRef]

- Telin, A.; Safarov, F.; Yakubov, R.; Gusarova, E.; Pavlik, A.; Lenchenkova, L.; et al. Thermal degradation study of hydrogel nanocomposites based on polyacrylamide and nanosilica used for conformance control and water shutoff. Gels 2024, 10, 846. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.I.A.D.R.; Carvalho, L.D.O.; Lopes, R.C.F.G.; Sena, L.E.B.; Amparo, S.E.Z.S.D.; Oliveira, C.P.M.D.; et al. Enhanced polyacrylamide polymer hydrogels using nanomaterials for water shutoff: Morphology, thermal and rheological investigations at high temperatures and salinity. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 405, 125041. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Robles, S.; Cortés, F.B.; Franco, C.A. Effect of the nanoparticles in the stability of hydrolyzed polyacrylamide/resorcinol/formaldehyde gel systems for water shut-off/conformance control applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47568. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, T.; Chujo, Y. Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA)-based hybrid materials with reactive zirconium oxide nanocrystals. Polym. J. 2010, 42, 58-65. [CrossRef]

- Adewunmi, A.A.; Ismail, S.; Sultan, A.S. Study on strength and gelation time of polyacrylamide/polyethyleneimine composite gels reinforced with coal fly ash for water shut-off treatment. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 132, 41392. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Zheng, L.; Wen, J.; et al. Modulation of syneresis rate and gel strength of PAM-PEI gels by nanosheets and their mechanisms. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 704, 135525. [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Du, G.; Sun, Y.; Fu, J. Self-healable, tough, and ultrastretchable nanocomposite hydrogels based on reversible polyacrylamide/montmorillonite adsorption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 5029-5037. [CrossRef]

- Helvacıoğlu, E.; Aydın, V.; Nugay, T.; Nugay, N.; Uluocak, B.G.; Şen, S. High strength poly(acrylamide)-clay hydrogels. J. Polym. Res. 2011, 18, 2341-2350. [CrossRef]

- Zolfaghari, R.; Katbab, A.A.; Nabavizadeh, J.; Tabasi, R.Y.; Nejad, M.H. Preparation and characterization of nanocomposite hydrogels based on polyacrylamide for enhanced oil recovery applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 100, 2096-2103. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, K.A.B.; Aguiar, K.; Oliveira, P.F.; Vicente, B.M.; Pedroni, L.G.; Mansur, C.R.E. Synthesis of hydrogel nanocomposites based on partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide, polyethyleneimine, and modified clay. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 4759-4769. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Shang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X. Experimental study of low molecular weight polymer/nanoparticle dispersed gel for water plugging in fractures. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 551, 95-107. [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Xu, K.; Song, H.; Chen, G.; Yang, J.; Niu, Y. Preparation, stability and rheology of polyacrylamide/pristine layered double hydroxide nanocomposites. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 3869-3876. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-P.; Cao, J.-J.; Jiang, W.-B.; Yang, Y.-Q.; Zhu, B.-Y.; Liu, X.-Y.; et al. Synthesis and mechanical properties of polyacrylamide gel doped with graphene oxide. Energies 2022, 15, 5714. [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Chen, F. Study on a strong polymer gel by the addition of micron graphite oxide powder and its plugging of fracture. Gels 2024, 10, 304. [CrossRef]

- Moradi-Araghi, A.; Doe, P.H. Hydrolysis and precipitation of polyacrylamides in hard brines at elevated temperatures. SPE Reservoir Eng. 1987, 2, 189-198. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Shuler, P.J.; Aften, C.W.; Tang, Y. Theoretical studies of hydrolysis and stability of polyacrylamide polymers. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2015, 121, 69-77. [CrossRef]

- Marandi, G.B.; Esfandiari, K.; Biranvand, F.; Babapour, M.; Sadeh, S.; Mahdavinia, G.R. pH sensitivity and swelling behavior of partially hydrolyzed formaldehyde-crosslinked poly(acrylamide) superabsorbent hydrogels. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 109, 1083-1092. [CrossRef]

- Fong, D.W.; Kowalski, D.J. An investigation of the crosslinking of polyacrylamide with formaldehyde using 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 1993, 31, 1625-1627. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Qin, Y.; Su, Y.; Pan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liao, R.; et al. Development of a high-strength and adhesive polyacrylamide gel for well plugging. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 6151-6159. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhao, M.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Dai, C. Development and gelation mechanism of ultra-high-temperature-resistant polymer gel. Gels 2023, 9, 726. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Hou, J.; Meng, X.; Zheng, Z.; Wei, Q.; Chen, Y.; et al. Effect of different phenolic compounds on performance of organically cross-linked terpolymer gel systems at extremely high temperatures. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 8120-8130. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.R.; Eoff, L.; Dalrymple, E.D.; Black, K.; Brown, D.; Rietjens, M. A natural polymer-based crosslinker system for conformance gel systems. SPE J. 2003, 8, 99-106. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-Y.; Li, X.-G.; Du, K.; Liu, H.-K. Development of a new high-temperature and high-strength polymer gel for plugging fractured reservoirs. Upstream Oil Gas Technol. 2020, 5, 100014. [CrossRef]

- Fox, K.B.; Evans, A.Jr. Acceleration of gelation of water soluble polymers. United States patent US 5447986, 5 Sep 1995.

- Ren, Q.; Jia, H.; Yu, D.; Pu, W.-F.; Wang, L.-L.; Li, B.; et al. New insights into phenol-formaldehyde-based gel systems with ammonium salt for low-temperature reservoirs. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 40657. [CrossRef]

- Hakiki, F.; Arifurrahman, F. Cross-linked and responsive polymer: gelation model and review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 119, 532-549. [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Shang, Z.; Yao, M.; Li, X. Mechanistic insight into improving strength and stability of hydrogels via nano-silica. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 357, 119094. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Hou, J.; Chen, Y.; Wei, Q.; Zhao, S.; Bai, B. Evaluation of terpolymer-gel systems crosslinked by polyethylenimine for conformance improvement in high-temperature reservoirs. SPE J. 2019, 24, 1726-1740. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, Q.; Wang, R.; Zhao, J.; Quan, Z.; Zhan, T.; et al. 3D hierarchical porous nitrogen-doped carbon/Ni@NiO nanocomposites self-templated by cross-linked polyacrylamide gel for high performance supercapacitor electrode. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 570, 286-299. [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. Incorporation of partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide with zwitterionic units and poly(ethylene glycol) units toward enhanced tolerances to high salinity and high temperature. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 788746. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yan, R.; Chen, H.; Lee, D.H.; Zheng, C. Characteristics of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin pyrolysis. Fuel 2007, 86, 1781-1788. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Control the polymorphism and morphology of calcium carbonate precipitation from a calcium acetate and urea solution. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 2377-2380. [CrossRef]

- De Silva, P.; Bucea, L.; Sirivivatnanon, V. Chemical, microstructural and strength development of calcium and magnesium carbonate binders. Cem. Concr. Res. 2009, 39, 460-465. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, T.E.L.; Łapa, A.; Samal, S.K.; Declercq, H.A.; Schaubroeck, D.; Mendes, A.C.; et al. Enzymatic, urease-mediated mineralization of gellan gum hydrogel with calcium carbonate, magnesium-enriched calcium carbonate and magnesium carbonate for bone regeneration applications. J. Tissue Eng. Regener. Med. 2017, 11, 3556-3566. [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, B. Urease-aided calcium carbonate mineralization for engineering applications: A review. J. Adv. Res. 2018, 13, 59-67. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ajo-Franklin, J.B.; Spycher, N.; Hubbard, S.S.; Zhang, G.; Williams, K.H.; et al. Geophysical monitoring and reactive transport modeling of ureolytically-driven calcium carbonate precipitation. Geochem. Trans. 2011, 12, 7. [CrossRef]

- Digiacomo, P.M.; Schramm, C.M. Mechanism of polyacrylamide gel syneresis determined by C-13 NMR. Paper SPE 11787, International Symposium on Oilfield and Geothermal Chemistry, Denver, USA, June 1-3; Society of Petroleum Engineers: Texas, USA, 1983. [CrossRef]

- Rauner, N.; Meuris, M.; Dech, S.; Godde, J.; Tiller, J.C. Urease-induced calcification of segmented polymer hydrogels-A step towards artificial biomineralization. Acta. Biomater. 2014, 10, 3942-3951. [CrossRef]

- Albonico, P.; Lockhart, T.P. Divalent ion-resistant polymer gels for high-temperature applications: Syneresis Inhibiting Additives. Paper SPE 25220, SPE International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry, New Orleans, USA, March 2-5; Society of Petroleum Engineers: Texas, USA,1993. [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Lv, Y.; Fan, X.; Zhao, C.; Dai, C.; Zhao, G. Study on rheology and microstructure of phenolic resin crosslinked nonionic polyacrylamide (NPAM) gel for profile control and water shutoff treatments. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 169, 546-552. [CrossRef]

- Caulfield, M.J.; Qiao, G.G.; Solomon, D.H. Some aspects of the properties and degradation of polyacrylamides. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 3067-3084. [CrossRef]

- Burrows, H.D.; Ellis, H.A.; Utah, S.I. Adsorbed metal ions as stabilizers for the thermal degradation of polyacrylamide. Polymer 1981, 22, 1740-1744. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.-H. The Two-stages thermal degradation of polyacrylamide. Polym. Test 1998, 17, 191-198. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.E.; Khan, I.; Morad, N.; Teng, T.T.; Poh, B.T. Thermal behavior and morphological properties of novel magnesium salt–polyacrylamide composite polymers. Polym. Compos. 2011, 32, 1515-1522. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjya, D.; Selvamani, T.; Mukhopadhyay, I. Thermal decomposition of hydromagnesite effect of morphology on the kinetic parameters. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2012, 107, 439-445. [CrossRef]

| gel strength code | description |

| A | No detectable gel formed: The viscosity of the gelant is as same as that of polymer solution. |

| B | Highly flowable gel: The viscosity of the gelant is slightly higher than that of the initial polymer solution. |

| C | Flowable gel: The majority of the gelant can flow upon inversion. |

| D | Medium flowable gel: 90-95% of the gel can flow upon inversion. |

| E | Slightly flowable gel: less than 85% of the gel can flow upon inversion. |

| F | Highly deformable gel: The gel is highly deformed but does not flow upon inversion. |

| G | Moderately deformable gel: The gel does not flow and the gel deforms to the middle of the bottle upon inversion. |

| H | Slightly deformable gel: The gel does not flow and only the surface of the gel undergoes slight deformation upon inversion. |

| I | Rigid gel: The surface of the gel does not deform upon inversion. |

| samples | time/d | |||||||||||||||||||

| 0.5 | 2.5 | 4.6 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 7.9 | 8.4 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 11.2 | 12.4 | 14.1 | 24.5 | 35.0 | 36.0 | 40.8 | 42.0 | 78.0 | 122 | 155 | |

| FG- 95 | A | B | B | B | B | B | B | D | D | F | G | H | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I |

| BG-T5-95 | A | A | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | C | D | E | F | H | I | I3 | I5 | / | / | / |

| BG-T10-95 | A | A | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | D | D | E | I | I0.5 | I1 | I5 | / | / | / | / |

| BG-T15-95 | A | B | B | B | B | C | D | E | E | F | F | F | H | H5 | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| BG-T20-95 | A | B | B | B | C | D | E | F | F | H | H | H0.5 | H5 | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| CG-T15-U0.10-95 | A | D | H | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I0.1 | F0.5 | F4 | F5 | / | / | / | / | / |

| CG-T15- U0.50-95 | A | B | D | E | H | H | H | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I5 | / | / |

| CG-T15- U0.75-95 | A | B | C | D | G | G | H | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I5 | / |

| CG-T15- U1.00-95 | A | B | B | C | D | F | G | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I |

| CG-T15- U1.50-95 | A | B | B | B | B | B | B | C | D | E | F | F | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I |

| CG-T15-U2.0-95 | A | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | C | D | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I |

| samples | time/d | ||||||||||||||||||

| 0.5 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 5.6 | 6.5 | 7.5 | 9.7 | 14.3 | 15.8 | 20.7 | 31.6 | 126 | 135 | |

| FG- 120 | A | B | B | B | C | D | D | D | H | H | H | I | I | I | I | I | I | I0.2 | I0.2 |

| BG-T5-120 | A | B | B | B | B | C | C | D | G | H0.1 | H0.2 | H0.5 | H2 | H4 | H5 | / | / | / | / |

| BG-T10-120 | A | B | B | B | B | C | D | G | G | H0.5 | H0.5 | H1 | H3 | H5 | / | / | / | / | / |

| BG-T15-120 | A | B | B | B | D | F | F | F | F0.5 | F0.5 | F1 | F3 | F5 | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| BG-T20-120 | A | B | C | D | F | G | G | G | H | H0.5 | H1 | H5 | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| CG-T15-U0.10-120 | A | D | H | H | F0.5 | F0.5 | F0.5 | F0.5 | F0.5 | F1 | F2 | F2.5 | F5 | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| CG-T15- U0.50-120 | A | B | D | D | F | G | G | H | I | I | I | I | I0.5 | I0.5 | I1 | I5 | / | / | / |

| CG-T15- U0.75-120 | A | B | C | D | E | F | F | F | G | G | G | H | I0.2 | I0.5 | H1 | H2 | H5 | / | / |

| CG-T15- U1.00-120 | A | B | B | B | B | C | D | D | F | G | H | H | H | H | I | I | I | I2 | I2.5 |

| CG-T15- U1.50-120 | A | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | C | D | G | H | H | H | I | I | I | I1 | I1.5 |

| CG-T15-U2.0-120 | A | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | C | D | F | G | H | I | I | I | I0.5 | I0.8 |

| samples | tD/d | tS/d |

| FG-95 | 9.7 | >176 |

| BG-T5-95 | 12.4 | 42.0 |

| BG-T10-95 | 11.2 | 40.8 |

| BG-T15-95 | 8.4 | 35.0 |

| BG-T20-95 | 7.9 | 24.5 |

| FG-120 | 2.7 | >126 |

| BG-T5-120 | 3.0 | 15.8 |

| BG-T10-120 | 2.9 | 14.3 |

| BG-T15-120 | 2.3 | 9.7 |

| BG-T20-120 | 1.9 | 7.5 |

| CPAM/% | CHQ/wt% | CHCHO/wt% | tD/d | tS/d |

| 1.0 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 12.6 | 69.2 |

| 1.0 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 7.7 | 71.0 |

| 1.0 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 4.6 | 78.0 |

| 1.0 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 1.9 | 56.1 |

| 1.0 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 1.6 | 43.9 |

| 0.5 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 9.1 | 37.8 |

| 1.5 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 1.2 | 57.0 |

| 2.0 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.7 | 57.0 |

| samples | Curea/wt% | tD/d | tS/d |

| CG-T5- U0.50-95 | 0.23 | 2.1 | 85.2 |

| CG-T10- U0.5-95 | 0.45 | 2.8 | 76.7 |

| CG-T15- U0.5-95 | 0.68 | 4.6 | 78.0 |

| CG-T20- U0.5-95 | 0.90 | 5.2 | 72.1 |

| CG-T5- U1.0-95 | 0.45 | 2.2 | 167.4 |

| CG-T10- U1.0-95 | 0.90 | 3.6 | 161.2 |

| CG-T15- U1.0-95 | 1.35 | 6.6 | 155.0 |

| CG-T20- U1.0-95 | 1.81 | 7.0 | 170.0 |

| ion concentration/mg·L-1 | total dissolved solids/mg·L-1 | |||

| Na+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | Cl- | |

| 99,998.7 | 6,816.0 | 6,818.6 | 186,366.7 | 3.0×105 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).