Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study design

Patients’ selection

Laboratory sampling

Calculations

3. Results

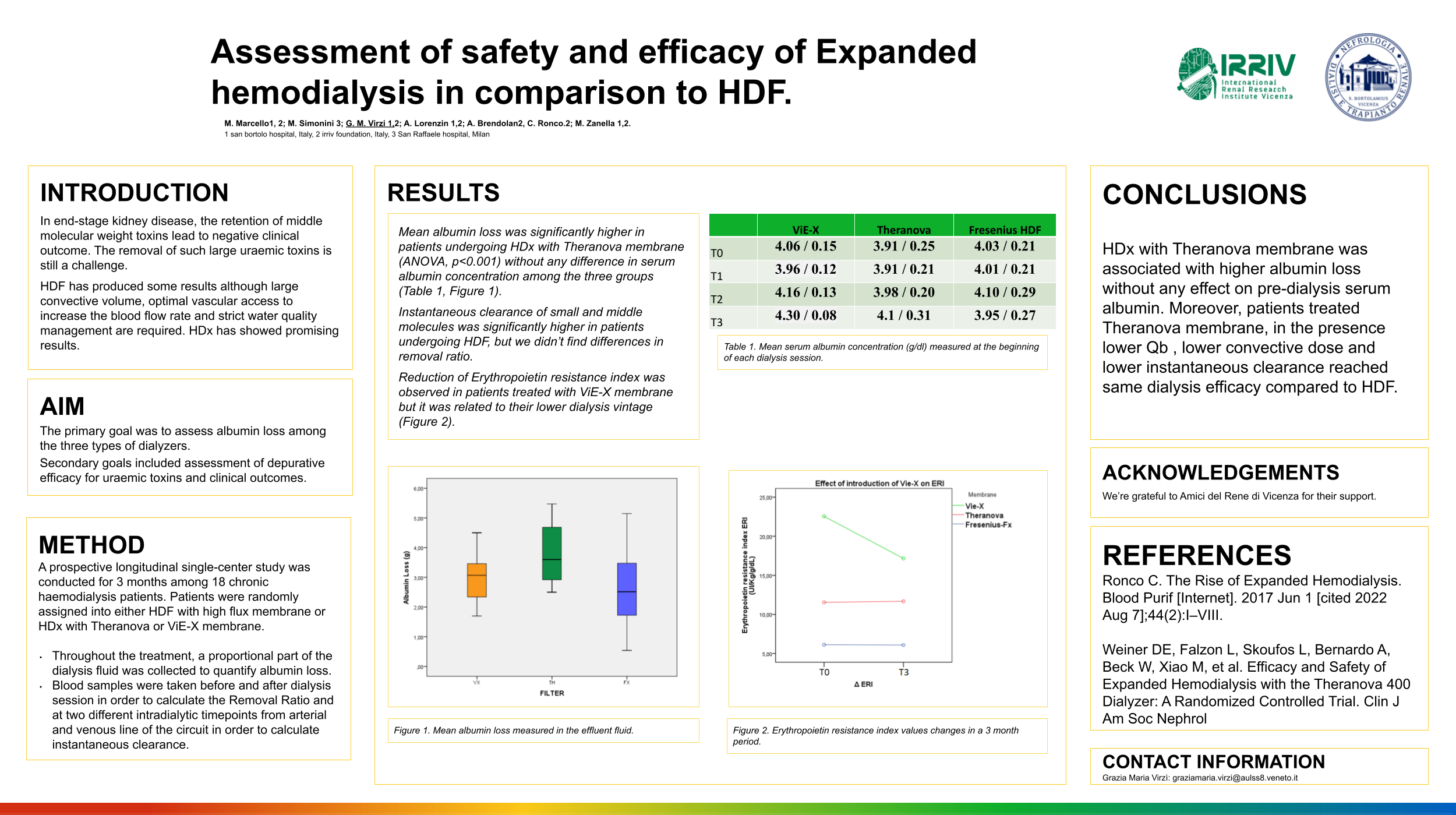

Primary endpoint

Secondary endpoint

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Authorship

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Ethical Approval

Conflicting Interest

References

- Locatelli F, Gauly A, Czekalski S, Hannedouche T, Jacobson SH, Loureiro A, et al. The MPO Study: just a European HEMO Study or something very different? Blood Purif [Internet]. 2008 Jan [cited 2022 Jul 31];26(1):100–4. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18182806/.

- Kuragano T, Kida A, Furuta M, Nanami M, Otaki Y, Hasuike Y, et al. The impact of beta2-microglobulin clearance on the risk factors of cardiovascular disease in hemodialysis patients. ASAIO J [Internet]. 2010 Jul [cited 2022 Jul 31];56(4):326–32. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20431482/.

- Nakano T, Matsui M, Inoue I, Awata T, Katayama S, Murakoshi T. Free immunoglobulin light chain: its biology and implications in diseases. Clin Chim Acta [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2022 Jul 31];412(11–12):843–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21396928/.

- Ronco, C. The Rise of Expanded Hemodialysis. Blood Purif [Internet]. 2017 Jun 1 [cited 2022 Aug 7];44(2):I–VIII. Available from: https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/476012.

- Sakurai, K. Biomarkers for evaluation of clinical outcomes of hemodiafiltration. Blood Purif [Internet]. 2013 Apr 24 [cited 2022 Aug 1];35 Suppl 1:64–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23466382/.

- Scholze A, Jankowski J, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Evenepoel P. Oxidative Stress in Chronic Kidney Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2022 Aug 7];2016. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27579156/.

- Lee BT, Ahmed FA, Lee Hamm L, Teran FJ, Chen CS, Liu Y, et al. Association of C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interleukin-6 with chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2022 Aug 30];16(1). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4449580/.

- Kaltsatou A, Sakkas GK, Poulianiti KP, Koutedakis Y, Tepetes K, Christodoulidis G, et al. Uremic myopathy: is oxidative stress implicated in muscle dysfunction in uremia? Front Physiol [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2022 Aug 7];6(MAR). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25870564/.

- Aucella F, Gesuete A, Vigilante M, Prencipe M. Adsorption dialysis: from physical principles to clinical applications. Blood Purif [Internet]. 2013 May [cited 2022 Aug 7];35 Suppl 2(SUPPL.2):42–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23676835/.

- Canaud B, Barbieri C, Marcelli D, Bellocchio F, Bowry S, Mari F, et al. Optimal convection volume for improving patient outcomes in an international incident dialysis cohort treated with online hemodiafiltration. Kidney Int [Internet]. 2015 Nov 1 [cited 2022 Aug 8];88(5):1108–16. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25945407/.

- Tattersall JE, Ward RA. Online haemodiafiltration: definition, dose quantification and safety revisited. Nephrol Dial Transplant [Internet]. 2013 Mar [cited 2022 Aug 10];28(3):542–50. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23345621/.

- Bradbury BD, Fissell RB, Albert JM, Anthony MS, Critchlow CW, Pisoni RL, et al. Predictors of early mortality among incident US hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2007 Jan [cited 2022 Aug 10];2(1):89–99. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17699392/.

- Smith JR, Zimmer N, Bell E, Francq BG, McConnachie A, Mactier R. A Randomized, Single-Blind, Crossover Trial of Recovery Time in High-Flux Hemodialysis and Hemodiafiltration. Am J Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2017 Jun 1 [cited 2022 Aug 29];69(6):762–70. Available from: http://www.ajkd.org/article/S0272638616306357/fulltext.

- Kirsch AH, Lyko R, Nilsson LG, Beck W, Amdahl M, Lechner P, et al. Performance of hemodialysis with novel medium cut-off dialyzers. Nephrol Dial Transplant [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2022 Aug 19];32(1):165–72. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27587605/.

- Fiore GB, Ronco C. Principles and practice of internal hemodiafiltration. Contrib Nephrol [Internet]. 2007 Aug 8 [cited 2022 Aug 28];158:177–84. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17684356/.

- Ronco C, Marchionna N, Brendolan A, Neri M, Lorenzin A, Martínez Rueda AJ. Expanded haemodialysis: from operational mechanism to clinical results. Nephrol Dial Transplant [Internet]. 2018 Oct 1 [cited 2022 Aug 28];33(suppl_3):iii41–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30281134/.

- Leypoldt JK, Cheung AK, Deeter RB. Single compartment models for evaluating beta 2-microglobulin clearance during hemodialysis. ASAIO J [Internet]. 1997 [cited 2022 Aug 15];43(6):904–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9386841/.

- Bergström J, Wehle B. No change in corrected beta 2-microglobulin concentration after cuprophane haemodialysis. Lancet (London, England) [Internet]. 1987 Mar 14 [cited 2022 Aug 15];1(8533):628–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2881162/.

- Chait Y, Kalim S, Horowitz J, Hollot C V., Ankers ED, Germain MJ, et al. The greatly misunderstood erythropoietin resistance index and the case for a new responsiveness measure. Hemodial Int [Internet]. 2016 Jul 1 [cited 2022 Aug 7];20(3):392–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26843352/.

- Lins L, Carvalho FM. SF-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: Scoping review. SAGE open Med [Internet]. 2016 Jan 1 [cited 2022 Aug 17];4:205031211667172. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27757230/.

- Maduell, F. Hemodiafiltration versus conventional hemodialysis: Should “conventional” be redefined? Semin Dial [Internet]. 2018 Nov 1 [cited 2022 Aug 29];31(6):625–32. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/sdi.12715.

- Weiner DE, Falzon L, Skoufos L, Bernardo A, Beck W, Xiao M, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Expanded Hemodialysis with the Theranova 400 Dialyzer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2020 Sep 7 [cited 2022 Sep 11];15(9):1310–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32843372/.

- Lowrie EG, Lew NL. Death risk in hemodialysis patients: the predictive value of commonly measured variables and an evaluation of death rate differences between facilities. Am J Kidney Dis [Internet]. 1990 [cited 2022 Sep 11];15(5):458–82. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2333868/.

- Van Gelder MK, Abrahams AC, Joles JA, Kaysen GA, Gerritsen KGF. Albumin handling in different hemodialysis modalities. Nephrol Dial Transplant [Internet]. 2018 Jun 1 [cited 2022 Sep 11];33(6):906–13. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29106652/.

- Cozzolino M, Magagnoli L, Ciceri P, Conte F, Galassi A. Effects of a medium cut-off (Theranova®) dialyser on haemodialysis patients: a prospective, cross-over study. Clin Kidney J [Internet]. 2021 Feb 3 [cited 2022 Sep 11];14(1):382–9. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ckj/article/14/1/382/5621471.

- Krishnasamy R, Hawley CM, Jardine MJ, Roberts MA, Cho Y, Wong M, et al. A tRial Evaluating Mid Cut-Off Value Membrane Clearance of Albumin and Light Chains in HemoDialysis Patients: A Safety Device Study. Blood Purif [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2022 Sep 11];49(4):468–78. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31968346/.

- Rocco M, Daugirdas JT, Depner TA, Inrig J, Mehrotra R, Rocco M V., et al. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Hemodialysis Adequacy: 2015 Update. Am J Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2015 Nov 1 [cited 2022 Sep 11];66(5):884–930. Available from: http://www.ajkd.org/article/S0272638615010197/fulltext.

- Pstras L, Ronco C, Tattersall J. Basic physics of hemodiafiltration. Semin Dial [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 14]; Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/sdi.13111.

- Lorenzin A, Neri M, Lupi A, Todesco M, Santimaria M, Alghisi A, et al. Quantification of Internal Filtration in Hollow Fiber Hemodialyzers with Medium Cut-Off Membrane. Blood Purif [Internet]. 2018 Jul 1 [cited 2022 Aug 28];46(3):196–204. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29886489/.

- Maduell, F. Hemodiafiltration versus conventional hemodialysis: Should “conventional” be redefined? Semin Dial [Internet]. 2018 Nov 1 [cited 2022 Sep 13];31(6):625–32. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29813181/.

- Maduell F, Broseta JJ, Rodas L, Montagud-Marrahi E, Rodriguez-Espinosa D, Hermida E, et al. Comparison of Solute Removal Properties Between High-Efficient Dialysis Modalities in Low Blood Flow Rate. Ther Apher Dial [Internet]. 2020 Aug 1 [cited 2022 Sep 13];24(4):387–92. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31583845/.

- Maduell F, Broseta JJ, Gómez M, Racionero P, Montagud-Marrahi E, Rodas L, et al. Determining factors for hemodiafiltration to equal or exceed the performance of expanded hemodialysis. Artif Organs [Internet]. 2020 Oct 1 [cited 2022 Sep 13];44(10):E448–58. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32279348/.

- Lee Y, Jang M jin, Jeon J, Lee JE, Huh W, Choi BS, et al. Cardiovascular Risk Comparison between Expanded Hemodialysis Using Theranova and Online Hemodiafiltration (CARTOON): A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2022 Aug 28];11(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34031503/.

- Yang SK, Xiao L, Xu B, Xu XX, Liu FY, Sun L. Effects of vitamin E-coated dialyzer on oxidative stress and inflammation status in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2022 Sep 12];36(5):722–31. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK231773/.

- Rodríguez-Ribera L, Corredor Z, Silva I, Díaz JM, Ballarín J, Marcos R, et al. Vitamin E-coated dialysis membranes reduce the levels of oxidative genetic damage in hemodialysis patients. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen [Internet]. 2017 Mar 1 [cited 2022 Sep 12];815:16–21. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28283088/.

- Girndt M, Lengler S, Kaul H, Sester U, Sester M, Köhler H. Prospective crossover trial of the influence of vitamin E-coated dialyzer membranes on T-cell activation and cytokine induction. Am J Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2000 Jan 1 [cited 2022 Aug 29];35(1):95–104. Available from: http://www.ajkd.org/article/S0272638600703076/fulltext.

- Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD, Block G, Humphreys MH. Association among SF36 quality of life measures and nutrition, hospitalization, and mortality in hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2022 Aug 29];12(12):2797–806. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11729250/.

- Ikizler TA, Cano NJ, Franch H, Fouque D, Himmelfarb J, Kalantar-Zadeh K, et al. Prevention and treatment of protein energy wasting in chronic kidney disease patients: a consensus statement by the International Society of Renal Nutrition and Metabolism. Kidney Int [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2022 Aug 29];84(6):1096–107. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23698226/.

- Mazairac AHA, de Wit GA, Grooteman MPC, Penne EL, van der Weerd NC, den Hoedt CH, et al. Effect of Hemodiafiltration on Quality of Life over Time. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2013 Jan 1 [cited 2022 Aug 29];8(1):82–9. Available from: https://cjasn.asnjournals.org/content/8/1/82.

- Alarcon JC, Bunch A, Ardila F, Zuñiga E, Vesga JI, Rivera A, et al. Impact of Medium Cut-Off Dialyzers on Patient-Reported Outcomes: COREXH Registry. Blood Purif [Internet]. 2021 Jan 1 [cited 2022 Aug 29];50(1):110–8. Available from: https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/508803.

| HDx | HDF | p-value | |||

| Group | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Filter | VIEX | THERANOVA | Fresenius Cordiax | ||

| Nr of patients (n/%) | 6 /25 | 6 / 25 | 6 / 25 | ||

| AGE (mean ± SD) | 67.6 ± 4.1 | 65.17 ± 7.73 | 70.33 ± 10.1 | ns | |

| SEX (male) (n/ %) | 4 / 66.7 | 4 / 66.7 | 3 / 50 | ns | |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 27.3 ± 4.3 | 24.67 ± 5.68 | 22.82 ± 1.64 | ns | |

| URINE OUTPUT (n/%) | ns | ||||

| <100 ml | 1 / 16.7 | 1 / 16.7 | 5 / 83.3 | ||

| < 500 ml | 3 / 50 | 4 / 66.7 | 1 / 16.7 | ||

| >500 ml | 2 / 33.3 | 1 / 16.7 | 0 | ||

| DIABETES (n/ %) | 2 / 33.3 | 1 / 16.7 | 3 / 50 | ns | |

| CHARLSON > 6 (n/%) | 3 / 50 | 2 / 33.3 | 3 / 50 | ns | |

| CHARLSON (mean ± SD) | 7.1 ± 0.9 | 5.67 ± 2.16 | 6.83 ± 2.99 | ns | |

| CKD CAUSE (n/%) | ns | ||||

| UNKNOWN | 4/ 66.7 | 1 / 16.7 | 5 / 83.3 | ||

| GLOMERULAR | 2/33.3 | 3 / 50 | 0 | ||

| OBSTRUCTIVE | 0 | 1 / 16.7 | 1 / 16.7 | ||

| ADPKD | 0 | 1 / 16.7 | 0 | ||

| DIALISYS VINTAGE (months) (median/IQR) | 15 [2.5-42.5] | 91 [18.5-113.2] | 149.8 [37-100] | .042 | |

| VASCULAR ACCES (n/%) | ns | ||||

| AVF | 5 / 83.3 | 3 / 50 | 5 / 83.3 | ||

| CVC | 1 / 16.7 | 3 / 50 | 1 / 16.7 | ||

|

Qb (ml/min) (median/IQR) |

290 [281-300] | 300 [287-300] | 300 [300-350] | <0.001 | |

|

Qf (ml/min) (median/IQR) |

13.15 [12.3-14] | 11,8 [7,9-14,3] | 99,1 [85,9-108,2] | <0.001 | |

|

ALBUMIN LOSS (G) (MEAN/SD) | |

| VIE-X | 2.9/ 0.7 |

| THERANOVA | 3.7/ 0.9 |

| FRESENIUS-FX | 2.5/ 1.1 |

|

SERUM ALBUMIN (G/DL) (MEAN±SD) | |

| VIE-X | |

| T0 | 4.06 / 0.15 |

| T1 | 3.96 / 0.12 |

| T2 | 4.16 / 0.13 |

| T3 | 4.30 / 0.08 |

| THERANOVA | |

| T0 | 3.91 / 0.25 |

| T1 | 3.91 / 0.21 |

| T2 | 3.98 / 0.20 |

| T3 | 4.1 / 0.31 |

| FRESENIUS-FX | |

| T0 | 4.03 / 0.21 |

| T1 | 4.01 / 0.21 |

| T2 | 4.10 / 0.29 |

| T3 | 3.95 / 0.27 |

| Vie-X | Theranova | FreseniusFx | p-value | ||

| K Urea (Mean±SD) | I | 258 ± 16 | 258± 15 | 277± 29 | 0.003 |

| F | 212 ± 10 | 199 ± 32 | 222 ± 501 | ns | |

| Δ | 45.6 ± 14.8 | 58.3 ± 34 | 54.5 ± 56.7 | ns | |

| Pre | 60.3 ± 9.6 | 58.0 ± 16.8 | 65.2 ± 14.2 | ns | |

| Post | 15.8 ± 4.9 | 16.2 ± 6.1 | 16.5 ± 5.8 | ns | |

| RR | 72.9 ± 5.1 | 72.1 ± 6.2 | 75.0 ± 4.4 | ns | |

| K Creatinine (Mean±SD) | I | 140 ± 17 | 144 ± 14 | 156 ± 20 | 0.007 |

| F | 133 ± 15 | 145 ± 13 | 151 ± 20 | 0.001 | |

| Δ | 7.3 ± 8.2 | -0.6 ± 11 | 5.4 ± 13.2 | 0.040 | |

| Pre | 8.6 ± 1.5 | 10.0 ± 1.3 | 9.1 ± 1.9 | 0.010 | |

| Post | 3.0 ± 0.7 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | ns | |

| RR | 65.5 ± 6.3 | 66.3 ± 6.3 | 66.9 ± 5.1 | ns | |

| K Uric Acid (Mean±SD) | I | 132.6 ± 12.5 | 143.7 ± 11 | 157.9 ± 25.7 | ns |

| F | 127.8 ± 6.0 | 133.9 ± 10 | 159.3 ± 26.0 | 0.010 | |

| Δ | 4.8 ± 8.1 | 10.7 ± 8.3 | -1.4 ± 11.8 | ns | |

|

K Phosphate (Mean±SD) |

I | 164.8 ± 12.6 | 174.5± 12.8 | 178.6 ± 13.8 | 0.002 |

| F | 154.1 ± 14.1 | 165.1 ± 11.8 | 169.5 ± 20.2 | 0.004 | |

| Δ | 10.6 ± 10.9 | 9.4 ± 4.1 | 9.0 ± 14.9 | ns | |

| Pre | 4.67 ± 0.7 | 4.69 ± 1.21 | 4.88 ± 0.85 | ns | |

| Post | 1.96 ± 0.95 | 2.03 ± 0.5 | 1.93 ± 0.45 | ns | |

| RR | 58.2 ± 11.2 | 56.1 ± 9.4 | 60.2 ± 7.3 | ns | |

|

K IL-6 (Mean±SD) |

I | 23.1 ± 17.4 | 12.8 ± 8 | 107.0 ± 28.1 | < 0.001 |

| F | 21.4 ± 19.7 | 10.4 ± 6.5 | 107.9 ± 26.0 | < 0.001 | |

| Δ | 1.7 ± 5.5 | 2.3 ± 8.8 | -0.9 ± 4.2 | ns | |

| Pre | 6,93 ± 0.15 | 6.96 ± 0.17 | 6.88 ± 0.16 | ns | |

| Post | 6.86 ± 0.28 | 6.90 ± 0.17 | 6.88 ± 0.07 | ns | |

| RR | 0.9 ± 3.7 | 0.9 ± 2.6 | - 0.05 ± 2.9 | ns | |

|

K β2-microglobulin (Mean±SD) |

I | 75.4 ± 12.6 | 86.9 ±10.1 | 128.5 ± 32.4 | < 0.001 |

| F | 82.0 ± 11.3 | 82.2 ± 14.2 | 110.7 ± 34.6 | < 0.001 | |

| Δ | -6.5 ± 14.1 | 4.2 ± 16.5 | 11.4± 26.8 | 0.013 | |

| Pre | 13.7 ± 2.8 | 16.0 ± 2.9 | 16.5 ± 3.6 | ns | |

| Post | 6.9 ± 1.1 | 7.2 ± 2.2 | 7.5 ± 1.8 | ns | |

| RR | 48.2 ± 8.9 | 55.9 ± 9.3 | 55.7 ± 13.2 | ns | |

|

Kα1-microglobulin (Mean±SD) |

I | 8.8 ± 5.3 | 8.0 ± 7.3 | 101.6 ± 42.1 | < 0.001 |

| F | 9.1 ± 12.3 | 10.9 ± 16.3 | 61.9 ± 36.3 | < 0.001 | |

| Δ | -0.3 ± 13.7 | -2.3 ± 12.6 | 33.0 ± 39.0 | <0.001 | |

| Pre | 222.4 ± 54.1 | 212.7 ± 25.0 | 264.5 ± 22.0 | < 0.001 | |

| Post | 232.4 ± 57.9 | 211.7 ± 33.1 | 254.0 ± 46.8 | 0.012 | |

| RR | - 4.5 ± 5.8 | 0.7 ± 13.2 | 4.5 ± 12.9 | 0.024 | |

|

K Myoglobin (Mean±SD) |

I | 58.3 ± 9.8 | 69.7 ± 11.9 | 94.5 ± 46.1 | < 0.001 |

| F | 45.0 ± 10.5 | 51.6 ± 7.3 | 73.4 ± 30.9 | < 0.001 | |

| Δ | 13.2 ± 12.0 | 18.1 ± 13.6 | 21.1 ± 38.9 | ns | |

| Pre | 196.4 ± 86.2 | 266.6 ± 121 | 198.2 ± 73.8 | 0.005 | |

| Post | 118.9 ± 46.5 | 135.2 ± 47.1 | 123.2 ± 73.5 | ns | |

| RR | 38.1 ± 8.6 | 47.1 ± 9 | 38.6 ± 23.1 | 0.07 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).