Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Methods

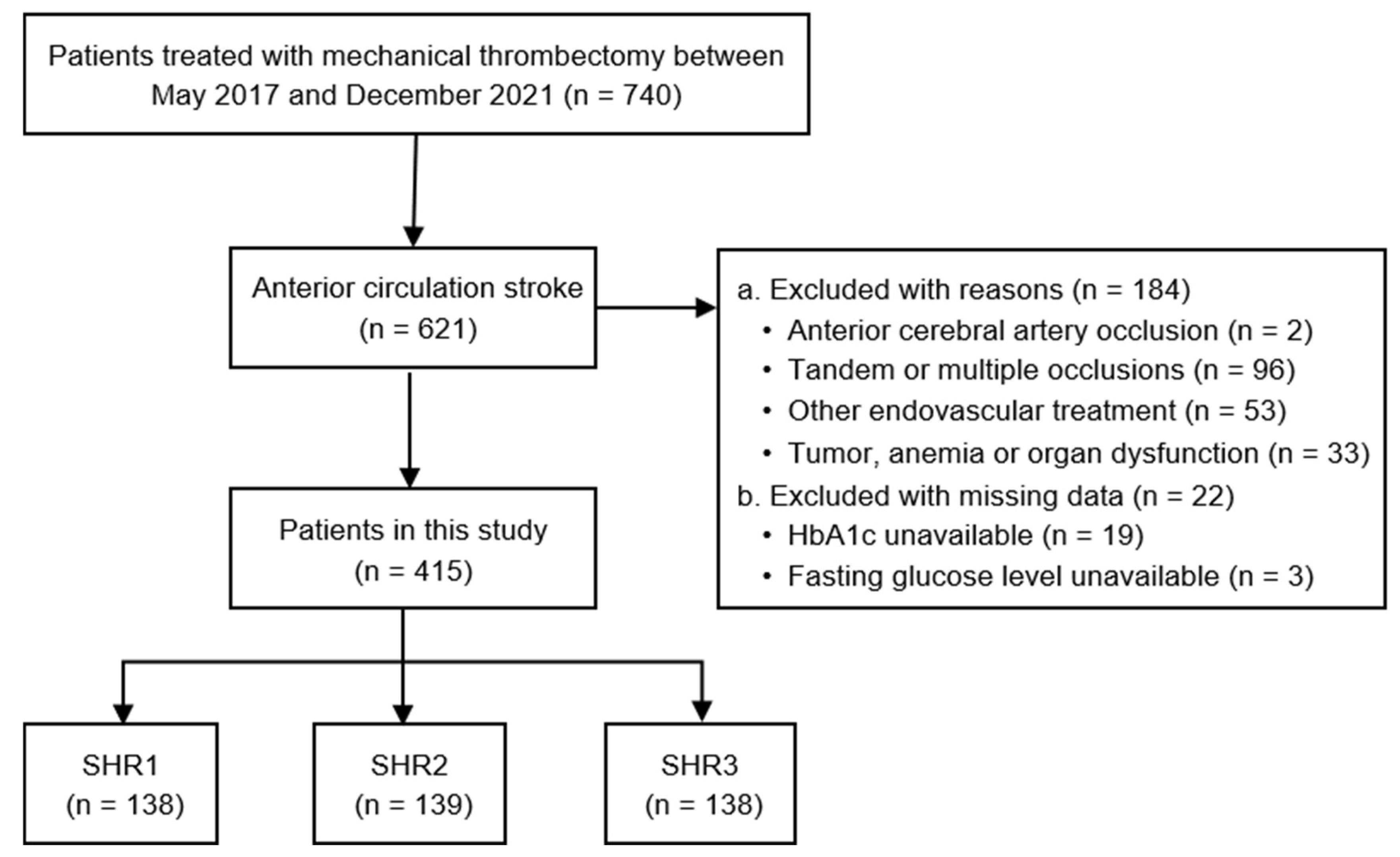

Study design

Participants

Baseline characteristics

Reperfusion therapy

Outcomes during hospitalization and 3-month follow-up

Statistical analysis

Results

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | SHR tertiles | P | ||||

| SHR1 (≤0.940) | SHR2 (0.940–1.177) | SHR3 (≥1.177) | ||||

| n | 138 | 139 | 138 | |||

| Demography | ||||||

| Age (years) | 69.0 (60.0–76.0) | 71.0 (61.0–80.0) | 76.0 (67.0–82.0) | <0.001 | ||

| Sex (female) | 48 (34.8%) | 46 (33.1%) | 66 (47.8%) | 0.023 | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 99 (71.7%) | 108 (77.7%) | 98 (71.0%) | 0.384 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 42 (30.4) | 37 (26.6%) | 42 (30.4%) | 0.722 | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 50 (36.2%) | 49 (35.3%) | 70 (50.7%) | 0.014 | ||

| Previous stroke/TIA | 38 (27.5%) | 33 (23.7%) | 30 (21.7%) | 0.522 | ||

| Pre-stroke mRS score ≤2 | 134 (97.1%) | 133 (96.4%) (n=138) | 132 (96.4%) (n=137) | 0.926 | ||

| Admission SBP | 133 (120–150) | 140 (123–157) | 144 (127–159) | 0.022 | ||

| Admission DBP | 83 (76–93) | 86 (76–95) | 86 (74–98) | 0.477 | ||

| Admission NIHSS score | 13 (8–17) | 13 (10–18) | 16 (12–19) | <0.001 | ||

| TOAST | 0.140 | |||||

| LAA | 65 (47.1%) | 68 (48.9%) | 50 (36.2%) | |||

| CE | 59 (42.8%) | 55 (39.6%) | 75 (54.3%) | |||

| Others | 14 (10.1%) | 16 (11.5%) | 13 (9.4%) | |||

| Blood test | ||||||

| FBG (mmol/l) | 4.8 (4.3–5.4) | 6.4 (5.7–6.9) | 8.5 (7.4–10.2) | <0.001 | ||

| HbA1c | 5.9 (5.6–6.8) | 5.9 (5.5–6.4) | 5.9 (5.5–6.6) | 0.495 | ||

| TC (mmol/l) | 4.0 (3.4–4.9) | 4.1 (3.4–4.9) (n=138) | 4.1 (3.5–4.9) (n=136) | 0.627 | ||

| TG | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) (n=138) | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) (n=136) | 0.217 | ||

| LDL | 2.4 (1.9–3.1) | 2.4 (2.0–3.1) (n=138) | 2.4 (1.9–3.0) (n=136) | 0.944 | ||

| BUN (mmol/l) | 4.8 (4.3–5.4) | 6.4 (5.7–6.9) | 8.5 (7.4–10.2) | 0.005 | ||

| eGFR(ml/(min·1.73 m2)) | 78.7 (59.9–98.9) | 75.9 (55.4–105.6) | 65.4 (51.0–88.7) | 0.002 | ||

| Intravenous alteplase | 50 (36.2%) | 54 (38.8%) | 63 (45.7%) | 0.257 | ||

| Occlusion site | 0.496 | |||||

| Intracranial ICA | 42 (30.4%) | 48 (34.5%) | 54 (39.1%) | |||

| The first segment of MCA | 87 (63.0%) | 81 (58.3%) | 72 (52.2%) | |||

| The second segment of MCA | 9 (6.5%) | 10 (7.2%) | 12 (8.7%) | |||

| Mechanical thrombectomy procedure | ||||||

| Door-to-puncture time | 115.0 (88.0–145.0) (n=135) | 110.0 (85.0–135.0) (n=135) | 113.0 (85.0–148.3) (n=134) | 0.819 | ||

| Successful recanalization | 124 (89.9%) | 126 (90.6%) | 111 (80.4%) | 0.019 | ||

| Symptomatic ICH at 24 h | 5 (3.6%) | 4 (2.9%) | 12 (8.7%) | 0.056 | ||

| Early neurological deterioration | 18 (22.8%) | 19 (24.1%) | 42 (53.2%) | <0.001 | ||

| Post-stroke pneumonia | 70 (50.7%) | 89 (64.0%) | 99 (71.7%) | 0.001 | ||

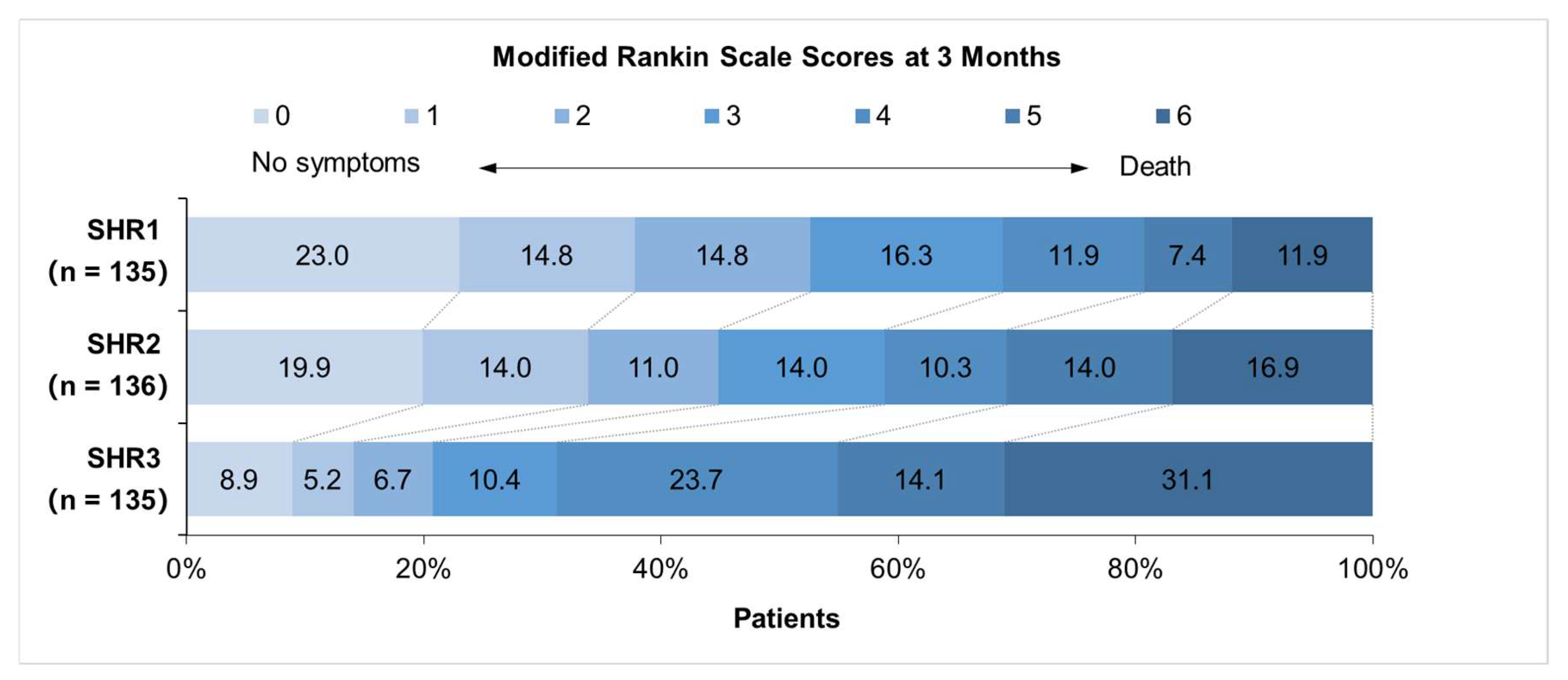

| mRS 3–6 at 3 months | 64 (47.4%) (n=135) | 75 (55.1%) (n=136) | 107 (79.3%) (n=135) | <0.001 | ||

| Death within 3 months | 16 (11.9%) (n=135) | 23 (16.9%) (n=136) | 43 (31.9%) (n=135) | <0.001 | ||

Clinical outcomes according to SHR tertiles

| SHR1–2 | SHR3 | P | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis* | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |||||

| Total population | n=277 | n=138 | ||||||

| sICH at 24h | 9 (3.2%) | 12 (8.7%) | 0.017 | 2.836 (1.165–6.905) | 0.022 | 4.088 (1.551–10.772) | 0.004 | |

| END at 72h | 37 (13.4%) | 42 (30.4%) | <0.001 | 2.838 (1.719–4.685) | <0.001 | 3.505 (1.984–6.192) | <0.001 | |

| post-stroke pneumonia | 159 (57.4%) | 99 (71.7%) | 0.005 | 1.884 (1.213–2.927) | 0.005 | 1.379 (0.838–2.268) | 0.206 | |

| DM | n=79 | n=42 | ||||||

| sICH at 24h | 2 (2.5%) | 5 (11.9%) | 0.048 | |||||

| END at 72h | 10 (12.7%) | 10 (23.8%) | 0.116 | 2.156 (0.816–5.697) | 0.121 | 2.533 (0.810–7.920) | 0.110 | |

| post-stroke pneumonia | 49 (62.0%) | 27 (64.3%) | 0.807 | 1.102 (0.506–2.399) | 0.807 | 1.018 (0.424–2.444) | 0.968 | |

| Non-DM | n=198 | n=96 | ||||||

| sICH at 24h | 7 (3.5%) | 7 (7.3%) | 0.240 | |||||

| END at 72h | 27 (13.6%) | 32 (33.3%) | <0.001 | 3.167 (1.760–5.697) | <0.001 | 5.313 (2.332–12.104) | <0.001 | |

| post-stroke pneumonia | 110 (55.6%) | 72 (75.0%) | 0.001 | 2.400 (1.398–4.120) | 0.001 | 4.089 (2.071–8.074) | <0.001 | |

| SHR1–2 | SHR3 | P | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |||||

| Total population | n=271 | n=135 | ||||||

| mRS 3–6 at 3 months | 139 (51.3%) | 107 (79.3%) | <0.001 | 1.799 (1.393–2.324) | <0.001 | 1.629 (1.230–2.158) | 0.001 | |

| Death within 3 months | 39 (14.4%) | 43 (31.9%) | <0.001 | 2.460 (1.573–3.848) | <0.001 | 1.986 (1.235–3.194) | 0.005 | |

| DM | n=75 | n=42 | ||||||

| mRS 3–6 at 3 months | 49 (65.3%) | 32 (76.2%) | 0.222 | 1.518 (0.962–2.395) | 0.073 | 1.587 (0.989–2.547) | 0.056 | |

| Death within 3 months | 11 (14.7%) | 13 (31.0%) | 0.036 | 2.492 (1.076–5.770) | 0.033 | 3.020 (1.219–7.484) | 0.017 | |

| Non-DM | n=196 | n=93 | ||||||

| mRS 3–6 at 3 months | 90 (45.9%) | 75 (80.6%) | <0.001 | 1.937 (1.419–2.645) | <0.001 | 1.600 (1.128–2.270) | 0.008 | |

| Death within 3 months | 28 (14.3%) | 30 (32.3%) | <0.001 | 2.346 (1.376–4.001) | 0.002 | 1.795 (1.007–3.200) | 0.047 | |

Impact of diabetes status on the association between SHR tertiles and outcomes

Added predictive value of SHR for outcomes during hospitalization and 3-month follow-up

| AUC (95% CI) | ΔAUC | P | |

| Symptomatic ICH at 24h | |||

| THRIVE-c | 0.564 (0.465–0.663) | - | - |

| THRIVE-c + SHR3 | 0.575 (0.460–0.690) | 0.011 | 0.040 |

| THRIVE-c + SHR-c | 0.636 (0.510–0.763) | 0.072 | 0.020 |

| Early neurological deterioration at 72h | |||

| THRIVE-c | 0.525 (0.453–0.596) | - | - |

| THRIVE-c + SHR3 | 0.530 (0.462–0.598) | 0.005 | 0.001 |

| THRIVE-c + SHR-c | 0.572 (0.497–0.678) | 0.042 | <0.001 |

| Post-stroke pneumonia | |||

| THRIVE-c | 0.669 (0.617–0.721) | - | - |

| THRIVE-c + SHR3 | 0.676 (0.622–0.729) | 0.007 | 0.311 |

| THRIVE-c + SHR-c | 0.687 (0.635–0.740) | 0.018 | 0.195 |

| mRS 3–6 at 3 months | |||

| THRIVE-c | 0.744 (0.697–0.791) | - | - |

| THRIVE-c + SHR3 | 0.751 (0.703–0.799) | 0.007 | 0.001 |

| THRIVE-c + SHR-c | 0.766 (0.720–0.813) | 0.022 | 0.040 |

| Death within 3 months | |||

| THRIVE-c | 0.690 (0.631–0.750) | - | - |

| THRIVE-c + SHR3 | 0.696 (0.635–0.758) | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| THRIVE-c + SHR-c | 0.731 (0.671–0.792) | 0.041 | 0.007 |

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of abbreviations

References

- Dungan K, Braithwaite S, Preiser J. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet. 2009;373:1798–807.

- Sun Y, Guo Y, Ji Y, Wu K, Wang H, Yuan L, et al. New stress-induced hyperglycaemia markers predict prognosis in patients after mechanical thrombectomy. BMC Neurol. 2023;23:132. [CrossRef]

- Roberts G, Sires J, Chen A, Thynne T, Sullivan C, Quinn S, et al. A comparison of the stress hyperglycemia ratio, glycemic gap, and glucose to assess the impact of stress-induced hyperglycemia on ischemic stroke outcome. J Diabetes. 2021;13:1034–42.

- Chen G, Ren J, Huang H, Shen J, Yang C, Hu J, et al. Admission random blood glucose, fasting blood glucose, stress hyperglycemia ratio, and functional outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke treated with intravenous thrombolysis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:782282. [CrossRef]

- Shen C, Xia N, Wang H, Zhang W. Association of stress hyperglycemia ratio with acute ischemic stroke outcomes post-thrombolysis. Front Neurol. 2021;12:785428. [CrossRef]

- Li G, Wang C, Wang S, Hao Y, Xiong Y, Zhao X. Clinical significance of stress hyperglycemic ratio and glycemic gap in ischemic stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2022;17:1841–9. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Liu Z, Miao J, Zheng W, Yang Q, Ye X, et al. High stress hyperglycemia ratio predicts poor outcome after mechanical thrombectomy for ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis Off J Natl Stroke Assoc. 2019;28:1668–73. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Zhou Z, Tian X, Wang H, Yang D, Hao Y, et al. Impact of relative blood glucose changes on mortality risk of patient with acute ischemic stroke and treated with mechanical thrombectomy. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis Off J Natl Stroke Assoc. 2019;28:213–9. [CrossRef]

- Gu M, Fan J, Xu P, Xiao L, Wang J, Li M, et al. Effects of perioperative glycemic indicators on outcomes of endovascular treatment for vertebrobasilar artery occlusion. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:1000030. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Yao Y, Zhang K, Zong C, Yang H, Li S, et al. Stress hyperglycemia predicts early neurological deterioration and poor outcomes in patients with single subcortical infarct. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2023;200:110689. [CrossRef]

- Zi W, Wang H, Yang D, Hao Y, Zhang M, Geng Y, et al. Clinical effectiveness and safety outcomes of endovascular treatment for acute anterior circulation ischemic stroke in China. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;44:248–58. [CrossRef]

- Kremers F, Venema E, Duvekot M, Yo L, Bokkers R, Lycklama À. Nijeholt G, et al. Outcome prediction models for endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke: systematic review and external validation. Stroke. 2022;53:825–36.

- Flint A, Rao V, Chan S, Cullen S, Faigeles B, Smith W, et al. Improved ischemic stroke outcome prediction using model estimation of outcome probability: the THRIVE-c calculation. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:815–21.

- Kastrup A, Brunner F, Hildebrandt H, Roth C, Winterhalter M, Gießing C, et al. THRIVE score predicts clinical and radiological outcome after endovascular therapy or thrombolysis in patients with anterior circulation stroke in everyday clinical practice. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24:1032–9. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Yin X, Li Z. Association of the stress hyperglycemia ratio and clinical outcomes in patients with stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2022;13:999536.

- Shen Y, Chao B, Cao L, Tu W, Wang L. Stroke center care and outcome: results from the CSPPC Stroke Program. Transl Stroke Res. 2020;11:377–86.

- Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Dávalos A, Guidetti D, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317–29. [CrossRef]

- Siegler J, Martin-Schild S. Early neurological deterioration (END) after Stroke: The END depends on the definition. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:211–2.

- Smith C, Kishore A, Vail A, Chamorro A, Garau J, Hopkins S, et al. Diagnosis of stroke-associated pneumonia: recommendations from the pneumonia in stroke consensus group. Stroke. 2015;46:2335–40.

- Sharma K, Akre S, Chakole S, Wanjari M. Stress-induced diabetes: a review. Cureus. 14:e29142. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari F, Moretti A, Villa R. Hyperglycemia in acute ischemic stroke: physiopathological and therapeutic complexity. Neural Regen Res. 2021;17:292–9.

- Pan Y, Cai X, Jing J, Meng X, Li H, Wang Y, et al. Stress hyperglycemia and prognosis of minor ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack: the CHANCE study (Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients With Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events). Stroke. 2017;48:3006–11.

- Tziomalos K, Dimitriou P, Bouziana S, Spanou M, Kostaki S, Angelopoulou S, et al. Stress hyperglycemia and acute ischemic stroke in-hospital outcome. Metabolism. 2017;67:99–105. [CrossRef]

- Merlino G, Pez S, Gigli GL, Sponza M, Lorenzut S, Surcinelli A, et al. Stress hyperglycemia in patients with acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion undergoing mechanical thrombectomy. Front Neurol. 2021;12:725002.

- Peng Z, Song J, Li L, Guo C, Yang J, Kong W, et al. Association between stress hyperglycemia and outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion. CNS Neurosci Ther. [CrossRef]

- Dai Z, Cao H, Wang F, Li L, Guo H, Zhang X, et al. Impacts of stress hyperglycemia ratio on early neurological deterioration and functional outcome after endovascular treatment in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1094353. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Dong D, Zeng Y, Yang B, Li F, Chen X, et al. The association between stress hyperglycemia and unfavorable outcomes in patients with anterior circulation stroke after mechanical thrombectomy. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:1071377.

- Wang Y, Fan H, Duan W, Ren Z, Liu X, Liu T, et al. Elevated stress hyperglycemia and the presence of intracranial artery stenosis increase the risk of recurrent stroke. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:954916. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Cheng Q, Hu T, Wang N, Wei X, Wu T, et al. Impact of stress hyperglycemia on early neurological deterioration in acute ischemic stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis. Front Neurol. 2022;13.

- Tao J, Hu Z, Lou F, Wu J, Wu Z, Yang S, et al. Higher stress hyperglycemia ratio is associated with a higher risk of stroke-associated pneumonia. Front Nutr. 2022;9:784114.

- Yuan C, Chen S, Ruan Y, Liu Y, Cheng H, Zeng Y, et al. The stress hyperglycemia ratio is associated with hemorrhagic transformation in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Clin Interv Aging. 2021;16:431–42. [CrossRef]

- Yang C, Liao W, Wang J, Tsai C, Lee J, Peng G, et al. Usefulness of glycated hemoglobin A1c-based adjusted glycemic variables in diabetic patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:1240–6.

- Capes S, Hunt D, Malmberg K, Pathak P, Gerstein H. Stress hyperglycemia and prognosis of stroke in nondiabetic and diabetic patients. Stroke. 2001;32:2426–32. [CrossRef]

- Mosenzon O, Cheng A, Rabinstein A, Sacco S. Diabetes and stroke: what are the connections? J Stroke. 2023;25:26–38.

- Muscari A, Falcone R, Recinella G, Faccioli L, Forti P, Pastore Trossello M, et al. Prognostic significance of diabetes and stress hyperglycemia in acute stroke patients. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2022;14:126.

- Qu K, Yan F, Qin X, Zhang K, He W, Dong M, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in vascular endothelial cells and its role in atherosclerosis. Front Physiol. 2022;13:1084604. [CrossRef]

- González P, Lozano P, Ros G, Solano F. Hyperglycemia and oxidative stress: an integral, updated and critical overview of their metabolic interconnections. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:9352.

- Mastrogiacomo L, Ballagh R, Venegas-Pino DE, Kaur H, Shi P, Werstuck GH. The effects of hyperglycemia on early endothelial activation and the initiation of atherosclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2023;193:121–33.

- Mac Grory B, Piccini J, Yaghi S, Poli S, De Havenon A, Rostanski S, et al. Hyperglycemia, risk of subsequent stroke, and efficacy of dual antiplatelet therapy: a post hoc analysis of the POINT trial. J Am Heart Assoc Cardiovasc Cerebrovasc Dis. 2022;11:e023223.

- Johnston K, Bruno A, Pauls Q, Hall C, Barrett K, Barsan W, et al. Intensive vs standard treatment of hyperglycemia and functional outcome in patients with acute ischemic stroke: the SHINE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:326–35.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).