Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Quantification of Potential Available Forest Resources

2.2. Quantification of Potentially Available Agro-Wastes

2.3. Review of Agronomic Performance of Alternative Growth Media

3. Availability of Local Raw Bio-Resources Excluding Imports

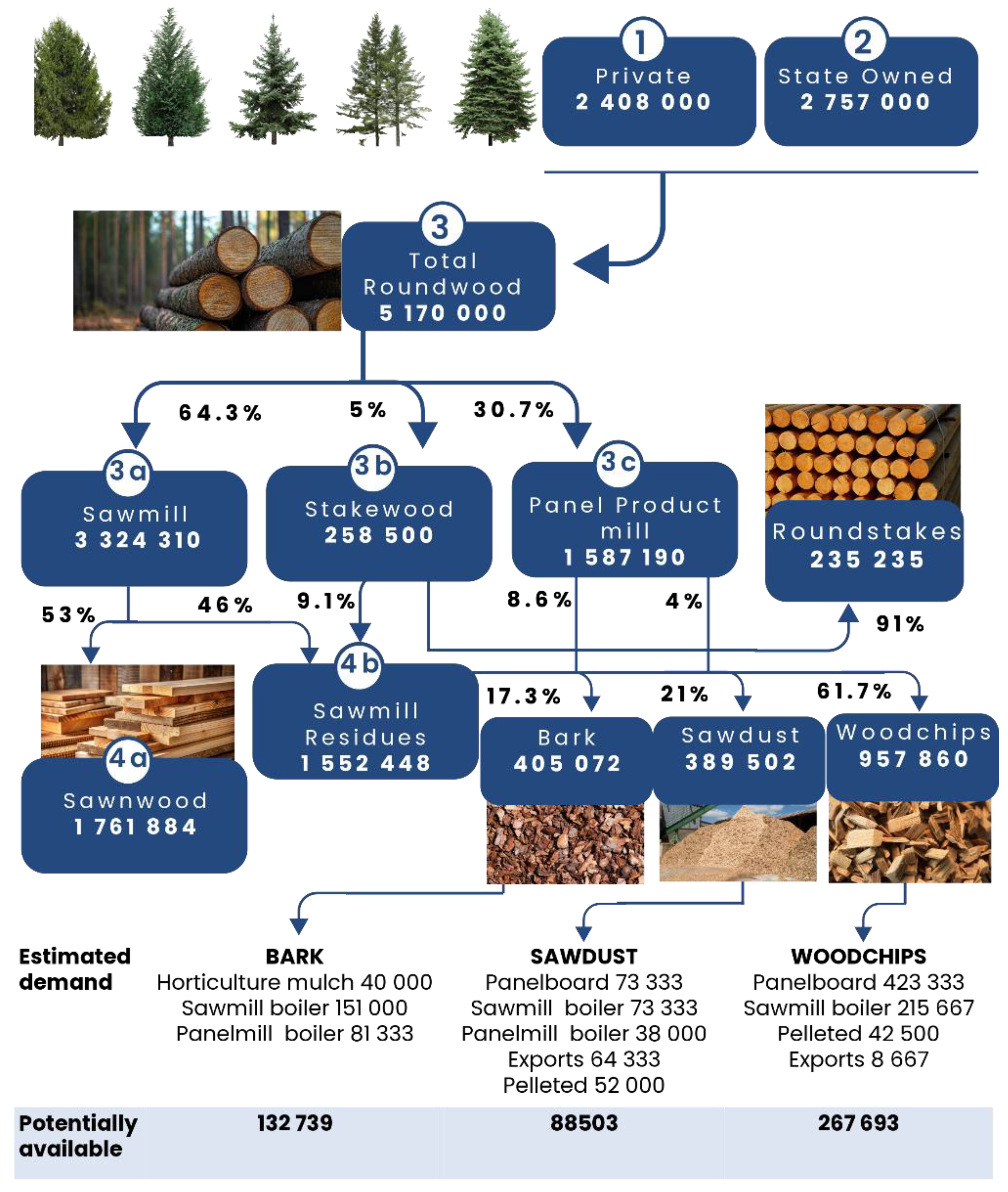

3.1. Availability of Wood and Forest Residues

3.2. Availability of Straw from Field Crops

3.3. Availability of Distillery/Brewers Spent Grain

3.4. Availability of Paper and Cardboard Waste, Municipal Composted Green Wastes, Digestates and Spent Mushroom Compost.

4. Biomass Processing Pathways for Production of Growth Media and Minimum Irish Estimates.

4.1. Mechanical Alteration (Chipping, Milling, Extruding Fibers)

4.2. Pyrolysis and Hydrothermal Carbonisation to Produce Biochars and Hydrochars

4.3. General Composting

4.4. Estimates of Potential Volumes That Could Be Produced from Available Resources in Ireland.

5. Recent Agronomic Effectiveness Results from Alternative Material Use in Horticultural Growth Media.

5.1. Raw and Mechanically Altered Materials as Growth Media (Milled, Shavings, Dust, Chopped, Extruded Fibers).

5.2. Thermally Carbonised Products (Bio- and Hydro- Chars) as Growth Media.

5.3. Composted Materials as Growth Media.

6. Identified Physico-Chemical Challenges of Alternative Growth Media and Opportunities.

6.1. Challenges with Wood and Plant Fibre

6.2. Challenges with Biochars/Hydrochars

6.3. Challenges with Composted Materials

6.4. Are Multi-Mix Growth Media the Answer?

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barrett, G.E.; Alexander, P.D.; Robinson, J.S.; Bragg, N.C. Achieving environmentally sustainable growing media for soilless plant cultivation systems – A review. Scientia Horticulturae 2016, 212, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European green deal. 2019.

- Prasad, M. Review of the use of peat moss in horticulture; 2021.

- Mulholland, B.J.; Waldron, K.; Watson, A.; Moates, G.; Whiteside, C.; Davies, J.; Newman, S.; Hickinbotham, R. Developing a methodology to replace peat in UK horticulture with responsibly sourced alternative raw materials. Acta Horticulturae 2019, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, N.; Alexander, P. A review of the challenges facing horticultural researchers as they move toward sustainable growing media. Acta Horticulturae 2019, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.H.; Kraska, T.; Winkler, W.; Aydinlik, S.; Jackson, B.E.; Pude, R. Primary Mechanical Modification to Improve Performance of Miscanthus as Stand-Alone Growing Substrates. Agronomy 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurdal, S.M.; Woznicki, T.L.; Haraldsen, T.K.; Kusnierek, K.; Sønsteby, A.; Remberg, S.F. Wood Fiber-Based Growing Media for Strawberry Cultivation: Effects of Incorporation of Peat and Compost. Horticulturae 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lonardo, S.; Cacini, S.; Becucci, L.; Lenzi, A.; Orsenigo, S.; Zubani, L.; Rossi, G.; Zaccheo, P.; Massa, D. Testing new peat-free substrate mixtures for the cultivation of perennial herbaceous species: A case study on Leucanthemum vulgare Lam. Scientia Horticulturae 2021, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschler, O.; Osterburg, B.; Weimar, H.; Glasenapp, S.; Ohmes, M.-F. Peat replacement in horticultural growing media: Availability of bio-based alternative materials; Thünen Institute: Braunschweig and Hamburg/Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- DAFM. Working paper to address challenges related to peat supply in the horticulture sector. 2022.

- Séamus Boland, I.R.L.I. Final report on the assessment of the Levels and suitability of current indigenous peat stocks and identification of sub-thirty hectare sites and other recommendations to support domestic horticulture industry as it transitions to peat alternatives; Séamus Boland, Irish Rural Link (IRL): 2022.

- Growing Media Ireland. Irish Horticultural Peat Industry 2021, Opening Statement. 2021.

- Galvin, L.F. Physical properties of Irish peats. Irish Journal of Agricultural Research 1976, 15, 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Ireland’s peatland conservation action plan 2020: halting the loss of peatland biodiversity, 2: Peatland Conservation Council, 2009.

- O’Brien, A. Over 390,000t of peat exported in 2022 – minister. Agriland 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. End the sale of peat moss compost in the retail sector. 2024.

- DAFM. Horticulture. 2020.

- COFORD. All Ireland Roundwood Production Forecast 2021-2040; Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine: Dublin, Ireland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- COFORD. All Ireland roundwood production forecast 2021-2040 - methodology; Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine: Dublin 2, Ireland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- COFORD. Forests and wood products, and their importance in climate change mitigation: A series of COFORD statements, 2022; 2.

- COFORD. Wood supply and demand on the island of Ireland to 2030; Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine: Dublin 2, Ireland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- COFORD. Wood supply and demand on the island of Ireland to 2025, 2018; 2.

- COFORD. All Ireland roundwood production forecast 2021-2040, 2021; 2.

- Whelan, D. ITGA submission on the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine’s Statement of Strategy 2020 - 2023. In Forestry and timber yearbook (2020); Irish timber growers association: Dublin, ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- O’driscoll, E. An overview of wood fibre use in ireland (2016). In Forestry and timber yearbook (2018); Irish timber growers association: Dublin, Ireland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- O’Driscoll, E. An overview of wood fibre use in Ireland (2017). In Forestry and timber yearbook (2019); Irish timber growers association: Dublin, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- O’Driscoll, E. An overview of wood fibre use in Ireland (2018). In Forestry and timber yearbook 2020; Irish timber growers association: Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Magner, D. Roundwood forecast supply to increase to 7.9 million m3 by 2035. In Forestry and timber yearbook (2021); Irish timber growers association: Dublin, Ireland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Magner, D. Timber production from private forests increased by 63% from 2015 to 2021. In Forestry and timber yearbook (2023); Irish timber growers association: Dublin, ireland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- FAO ITTO and United Nations. Forest product conversion factors, 2020.

- Teagasc. Harvest report 2022; Teagasc: Carlow, Ireland, 17/10/2023 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Teagasc. Harvest report 2023; Teagasc: Carlow, Ireland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Teagasc. Harvest Report 2020; Crops Knowledge Transfer Department, Teagasc: Carlow, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Teagasc. Harvest report 2021; Teagasc: Carlow, Ireland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Teagasc. Fact sheet energy -13: Straw for energy. 2020.

- Nolan, A.; Mc Donnell, K.; Devlin, G.J.; Carroll, J.P.; Finnan, J. Potential availability of non-woody biomass feedstock for pellet production within the Republic of Ireland. Int J Agric & Biol Eng. [CrossRef]

- Robb, S. Where to next for willow and miscanthus. Available online: https://www.farmersjournal.ie/where-to-next-for-willow-and-miscanthus-684693 (accessed on 23/07/2024).

- Caslin, B.; Finnan, J.; Johnston, C.; McCracken, A.; Walsh, L. Short rotation coppice willow; best practice guidelines; Teagasc and AFBI: 2015.

- EPA. National Waste Statistics. 2023.

- DAFM. Forest Statistics Ireland 2023. 2023.

- Sosa, A.; Klvac, R.; Coates, E.; Kent, T.; Devlin, G. Improving Log Loading Efficiency for Improved Sustainable Transport within the Irish Forest and Biomass Sectors. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3017–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Tuama, P.; Purser, P.; Wilson, F.; Dhubháin, Á.N. Challenges and opportunities – Sitka spruce in Ireland. In Introduced tree species in European forests: opportunities and challenges, Krumm, F., Vítková, L., Eds.; European Forest Institute: 2016; pp. 344-351.

- Magner, D. Weak home market driving increased pulpwood exports. Farmers journal 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Knaggs, G.; O’Driscoll, E. Woodflow and forest-based biomass energy use on the island of Ireland (2018). 2019.

- Wallace, M. Economic impact assessment of the tillage sector in Ireland; 2020.

- Teagasc. Mushroom Sector Development Plan to 2020; Teagasc Mushroom Stakeholder Consultative Group: Carlow, Ireland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- SIM. The Straw Incorporation Measure (SIM) 2022; Article 28 of Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of (Agri-environment-climate). 2022. 17 December.

- DAFM. Report on consultation on the potential for growing fibre crops and whether these crops have a viable market. 2022.

- Styles, D.; Thorne, F.; Jones, M.B. Energy crops in Ireland: An economic comparison of willow and Miscanthus production with conventional farming systems. Biomass and Bioenergy 2008, 32, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry-Ryan, E.C.U.a.C. Overview of the Irish brewing and distilling. Brewing Science 2022, 75, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kieran, M. Lynch, E.J.S., Elke K. Arendt. Brewers’ spent grain: a review with an emphasison food and health. Journal of the Institute of Brewing Volume 122, Issue 4.

- Abolore, R.S. , Pradhan, D., Jaiswal, S., Jaiswal, A.K. Characterization of Spent Grain from Irish Whiskey Distilleries for Biorefinery Feedstock Potential to Produce High-Value Chemicals and Biopolymers. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 11577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, R.J. Incorporation of novel brewers’ spent grain (BSG)-derived protein hydrolysates and blended ingredient in functional foods for older adults and assessment of health benefits in vivo; 2022.

- J. C. Akunna, G.M.W. J. C. Akunna, G.M.W. Co-products from malt whisky production and their utilisation. In The alcohol textbook: a reference for the beverage, fuel and industrial alcohol industries, G. M. Walker, C.A., W. M. Ingledew, C. Pilgrim, Ed.; Lallemand Biofuels & Distilled Spirits: 2017; pp. 529-537.

- Umego, E.C.; Barry-Ryan, C. "Review of the valorization initiatives of brewing and distilling byproducts. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naibaho, J.a.K., M. The variability of physico-chemical properties of brewery spent grain from 8 different breweries. Heliyon 2021, 7, 2405–8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikram, S.; Huang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Yin, M. Composition and Nutrient Value Proposition of Brewers Spent Grain. J Food Sci 2017, 82, 2232–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, A.; Melito, S.; Garau, M.; Giannini, V.; Zara, G.; Assandri, D.; Oufensou, S.; Coronas, R.; Pampuro, N.; Budroni, M. The potential use of brewers’ spent grain-based substrates as horticultural bio-fertilizers. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysargyris, A.; Stavrinides, M.; Moustakas, K.; Tzortzakis, N. Utilization of paper waste as growing media for potted ornamental plants. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2018, 21, 1937–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, S.N.; Holland, L.B.; Linnane, S.U. Spent mushroom compost management and options for use. 2012.

- Maher, M.J.; Magette, W.L.; Smyth, S.; Duggan, J.; Dodd, V.A.; Hennerty, M.J.; McCabe, T. Managing spent mushroom compost; 84170 113 0; Teagasc: Dublin, ireland, 2000; ISBN 1. [Google Scholar]

- Northway Mushrooms. Submission 32 Northway Mushrooms public consultation. 2020.

- Lee, J.S.; Rezaei, H.; Gholami Banadkoki, O.; Yazdan Panah, F.; Sokhansanj, S. Variability in Physical Properties of Logging and Sawmill Residues for Making Wood Pellets. Processes 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, C.; Pecenka, R.; Løes, A.-K.; Cáceres, R.; Conroy, J.; Rayns, F.; Schmutz, U.; Kir, A.; Kruggel-Emden, H. Extrusion of Different Plants into Fibre for Peat Replacement in Growing Media: Adjustment of Parameters to Achieve Satisfactory Physical Fibre-Properties. Agronomy 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumbure, A.; Bishop, P.; Bretherton, M.; Hedley, M. Co-Pyrolysis of Maize Stover and Igneous Phosphate Rock to Produce Potential Biochar-Based Phosphate Fertilizer with Improved Carbon Retention and Liming Value. ACS Sustainable Chemistry and Engineering 2020, 8, 4178–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshman, V.; Brassard, P.; Hamelin, L.; Raghavan, V.; Godbout, S. Pyrolysis of Miscanthus: Developing the mass balance of a biorefinery through experimental tests in an auger reactor. Bioresource Technology Reports 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, J.S.; Hude, M.P.; Yadav, G.D.; Thomas, M.; Kozinski, J.; Dalai, A.K. Hydrothermal processing of waste pine wood into industrially useful products. Journal of the Indian Chemical Society 2022, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, R.R.; Trugilho, P.F.; Silva, C.A.; Melo, I.; Melo, L.C.A.; Magriotis, Z.M.; Sanchez-Monedero, M.A. Properties of biochar derived from wood and high-nutrient biomasses with the aim of agronomic and environmental benefits. PLoS One 2017, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedmihradská, A.; Pohořelý, M.; Jevič, P.; Skoblia, S.; Beňo, Z.; Farták, J.; Čech, B.; Hartman, M. Pyrolysis of wheat and barley straw. Research in Agricultural Engineering 2020, 66, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Lau, A.; Sokhansanj, S. Hydrothermal carbonization and pelletization of moistened wheat straw. Renewable Energy 2022, 190, 1018–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Peng, Q.; Yang, R.; Lin, W.; Wang, H.; Zhou, W.; Qi, Z.; Ouyang, L. Slight carbonization as a new approach to obtain peat alternative. Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaoui, A.; Ben Hassen Trabelsi, A.; Ben Abdallah, A.; Chagtmi, R.; Lopez, G.; Cortazar, M.; Olazar, M. Assessment of pine wood biomass wastes valorization by pyrolysis with focus on fast pyrolysis biochar production. Journal of the Energy Institute 2023, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutaieb, M.; Guiza, M.; Román, S.; Ledesma Cano, B.; Nogales, S.; Ouederni, A. Hydrothermal carbonization as a preliminary step to pine cone pyrolysis for bioenergy production. Comptes Rendus. Chimie 2021, 23, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada Arias, E.; Bertero, M.; Jozami, E.; Feldman, S.R.; Falco, M.; Sedran, U. Pyrolytic conversion of perennial grasses and woody shrubs to energy and chemicals. SN Applied Sciences 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta, A.K.; Snoussi, Y.; Garah, M.E.; Ammar, S.; Chehimi, M.M. Brewer’s Spent Grain Biochar: Grinding Method Matters. C Journal of carbon research 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Araújo, F.P.; de Souza Cupertino, G.; de Cássia Superbi de Sousa, R.; de Castro Santana, R.; Pereira, A.F. Use of biochar produced from brewer’s spent grains as an adsorbent. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, E.; Zeaiter, J.; Ahmad, M.N.; Leahy, J.J.; Kwapinski, W. Hydrothermal carbonization of spent mushroom compost waste compared against torrefaction and pyrolysis. Fuel Processing Technology 2021, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, M.; Lee, A.; Prasad, M.; Cassidy, J. Municipal organic wastes in crop production. TRESEARCH 2017.

- Czekała, W.; Janczak, D.; Pochwatka, P.; Nowak, M.; Dach, J. Gases Emissions during Composting Process of Agri-Food Industry Waste. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Rico, V.S.; Bodelier, P.L.E.; van Eekert, M.; Sechi, V.; Veeken, A.; Buisman, C. Producing organic amendments: Physicochemical changes in biowaste used in anaerobic digestion, composting, and fermentation. Waste Manag 2022, 149, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitenbeck, G.A.; Schellinger, D. Calculating the Reduction in Material Mass And Volume during Composting. Compost Science & Utilization 2004, 12, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeter-Zakrzewska, A.; Komorowicz, M. The Use of Compost from Post-Consumer Wood Waste Containing Microbiological Inoculums on Growth and Flowering of Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum × grandiflorum Ramat./Kitam.). Agronomy 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M. Evaluation of woodwastes as a substrate for ornamental crops watered by capillary and drip irrigation. Acta Horticulturae 1980, 99, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poleatewich, A.; Michaud, I.; Jackson, B.; Krause, M.; DeGenring, L. The Effect of Peat Moss Amended with Three Engineered Wood Substrate Components on Suppression of Damping-Off Caused by Rhizoctonia solani. Agriculture 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Orozco, M.; Prieto-Ruíz, J.; Aldrete, A.; Hernández-Díaz, J.; Chávez-Simental, J.; Rodríguez-Laguna, R. Nursery Production of Pinus engelmannii Carr. with Substrates Based on Fresh Sawdust. Forests 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fascella, G.; Mammano, M.M.; D’Angiolillo, F.; Rouphael, Y. Effects of conifer wood biochar as a substrate component on ornamental performance, photosynthetic activity, and mineral composition of pottedRosa rugosa. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2017, 93, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, D.; Creber, H.; Van Poucke, R.; Sohi, S.; Meers, E.; Mašek, O.; Ronsse, F. Biochar from sawmill residues: characterization and evaluation for its potential use in the horticultural growing media. Biochar 2021, 3, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysargyris; Prasad; Kavanagh; Tzortzakis. Biochar Type and Ratio as a Peat Additive/Partial Peat Replacement in Growing Media for Cabbage Seedling Production. Agronomy 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fascella, G.; Mammano, M.M.; D’Angiolillo, F.; Pannico, A.; Rouphael, Y. Coniferous wood biochar as substrate component of two containerized Lavender species: Effects on morpho-physiological traits and nutrients partitioning. Scientia Horticulturae 2020, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.; Tzortzakis, N.; McDaniel, N. Chemical characterization of biochar and assessment of the nutrient dynamics by means of preliminary plant growth tests. J Environ Manage 2018, 216, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysargyris, A.; Prasad, M.; Kavanagh, A.; Tzortzakis, N. Biochar Type, Ratio, and Nutrient Levels in Growing Media Affects Seedling Production and Plant Performance. Agronomy 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Niu, G.; Starman, T.; Gu, M. Growth and development of Easter lily in response to container substrate with biochar. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2018, 94, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, S.F.; Kenar, J.A.; Thompson, A.R.; Peterson, S.C. Comparison of biochars derived from wood pellets and pelletized wheat straw as replacements for peat in potting substrates. Industrial Crops and Products 2013, 51, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.; Maher, M.J. Evaluation of composted botanic materials as components of a reduced-peat growing media for nursery stock. European Compost Network ECN 2006, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Mininni, C.; Grassi, F.; Traversa, A.; Cocozza, C.; Parente, A.; Miano, T.; Santamaria, P. Posidonia oceanica (L.) based compost as substrate for potted basil production. J Sci Food Agric 2015, 95, 2041–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczewska-Sowińska, K.; Sowiński, J.; Jamroz, E.; Bekier, J. Combining Willow Compost and Peat as Media for Juvenile Tomato Transplant Production. Agronomy 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczewska-Sowinska, K.; Sowinski, J.; Jamroz, E.; Bekier, J. Compost from willow biomass (Salix viminalis L.) as a horticultural substrate alternative to peat in the production of vegetable transplants. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 17617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marutani, M.; Clemente, S. Compost-Based Growing Media Improved Yield of Leafy Lettuce in Pot Culture. Agronomy 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.; Siebert, S. Overview of bio-waste collection, treatment & markets across Europe; European Compost Network ECN: Bochum, Germany, 06 January 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.-H.; Duan, Z.-Q.; Li, Z.-G. Use of Spent Mushroom Substrate as Growing Media for Tomato and Cucumber Seedlings. Pedosphere 2012, 22, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, D.; Malorgio, F.; Lazzereschi, S.; Carmassi, G.; Prisa, D.; Burchi, G. Evaluation of two green composts for peat substitution in geranium (Pelargonium zonale L.) cultivation: Effect on plant growth, quality, nutrition, and photosynthesis. Scientia Horticulturae 2018, 228, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzińska, A.; Salachna, P.; Nowak, J.S.; Kowalczyk, W.; Piechocki, R.; Łopusiewicz, Ł.; Pietrak, A. Compost Based on Pulp and Paper Mill Sludge, Fruit-Vegetable Waste, Mushroom Spent Substrate and Rye Straw Improves Yield and Nutritional Value of Tomato. Agronomy 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.W. , Helms, K. M., Jackson, B. E., Machesney, L. M., and Lee, J. A. Evaluation of Peat Blended with Pine Wood Components for Effects on Substrate Physical Properties, Nitrogen Immobilization, and Growth of Petunia (Petunia ×hybrida Vilm.-Andr.). HortScience 2022, 57, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woznicki, T.; Jackson, B.E.; Sønsteby, A.; Kusnierek, K. Wood Fiber from Norway Spruce—A Stand-Alone Growing Medium for Hydroponic Strawberry Production. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, B.E. Methods for mitigating toxicity in fresh wood substrates. Greenhouse Management 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, J.-C. , Durand, S., Jackson, B.E. and Fonteno, W.C. Analyzing rehydration efficiency of hydrophilic (wood fiber) vs potentially hydrophobic (peat) substrates using different irrigation methods. Acta Horticulturae 2021, 1317, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysargyris, A.; Antoniou, O.; Tzionis, A.; Prasad, M.; Tzortzakis, N. Alternative soilless media using olive-mill and paper waste for growing ornamental plants. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2018, 25, 35915–35927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Liao, J.; Zhou, B.; Yang, R.; Lin, W.; Zhang, D.; Wang, H.; Qi, Z. Rapidly reducing phytotoxicity of green waste for growing media by incubation with ammonium. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2023, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escuer, O.; Karp, K.; Escuer-Gatius, J.; Raave, H.; Teppand, T.; Shanskiy, M. Hardwood biochar as an alternative to reduce peat use for seed germination and growth of Tagetes patula. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B — Soil & Plant Science 2021, 71, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, R.W.; Mustafa, M.; Kappel, N.; Csambalik, L.; Szabó, A. Practical applications of spent mushroom compost in cultivation and disease control of selected vegetables species. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management 2024, 26, 1918–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fabal, A.; López-López, N. Using gorse compost as a peat-free growing substrate for organic strawberry production. Biological Agriculture & Horticulture 2022, 39, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandecasteele, B.; Debode, J.; Willekens, K.; Van Delm, T. Recycling of P and K in circular horticulture through compost application in sustainable growing media for fertigated strawberry cultivation. European Journal of Agronomy 2018, 96, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criscione, K.S.; Fields, J.S.; Owen, J.S.; Fultz, L.; Bush, E. Evaluating Stratified Substrates Effect on Containerized Crop Growth under Varied Irrigation Strategies. HortScience 2022, 57, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Crop | Estimated straw yields (t/ha) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Winter wheat | 4.2 | [35] |

| Summer wheat | 3 | [35] |

| Winter barley | 4.2 | [35] |

| Summer barley | 3.6 | [35] |

| Winter Oats | 4.7 | [35] |

| Summer Oats | 3.9 | [35] |

| Oil seed rape | 2.2 | [36] |

| Beans | 3.7 | [36] |

| Willow and miscanthus | 10 | [37] |

| Type | 5-year Average annual cropping (ha) | Quantity produced (t)1 | Total Volume produced (m3) | Competing Uses | Reference | Potentially available for growth media (m3)2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat straw | 60 440 | 246 000 | 1 824 500 | c.93% of total combined cereals straw baled (wheat, barley, oats) [45], of which 60%-90% is used for bedding and feed [35,45], and 8.5 – 8.9% is used for mushroom compost (excluding oat straw) [35,45] | [31,32,33,34,45] | 145 960 |

| Barley straw | 186 280 | 710 052 | 5 266 219 | see above | [31,32,33,34,45] | 421 298 |

| Oats straw | 26 500 | 113 622 | 842 697 | see above | [31,32,33,34,45] | 67 416 |

| Oilseed rape straw | 12 460 | 27 910 | 207 002 | c.25% baled [45] | [31,32,33,34,45] | 155 252 |

| Bean Straw | 27340 | 38 796 | 287 737 | Amount used as animal feed and animal bedding unknown – est 90% | [31,32,33,34] | 28 774 |

| Miscanthus | 5933 | 5 930 | 31 997 | The amount used in energy production and animal bedding figures unknown. – est 60% | [49] | 12 799 |

| Willow | 2783 | 2 780 | 18 5334 | First harvest in 3- 4 years [37] Amount used in energy production unknown. – est 60% | [37] | 7 413 |

| Material | Mechanical Process | Final bulk density of product (kg/m3) | Estimated product yield (% mass to volume change) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soft wood | Sawdust | 232 | 431 | [63] |

| Willow | Chipped | 150 | 667 | [38] |

| Miscanthus | Hammer milled | 160 | 625 | [6] |

| Forest residues | Twin screw extrusion | 182 | 549 | [64] |

| Paper Waste | Shredded | 107 | 935 | [59] |

| Type of feedstocks | Thermal carbonisation conditions | Expected yield (% w/w) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agro-wastes e.g. wheat, barley, oats | 300 - 600 oC, dry | 24 - 60% | [69] |

| Agro-wastes e.g. wheat, barley, oats | 100 - 220 oC, wet | 63 – 71% | [70] |

| Woody shrub clippings, forest residues, pine bark | 350 - 750, dry | 32 – 60% | [71] [68] |

| Pinecones | 500 – 700 oC, wet | 18 – 84% | [72,73] |

| Grass clippings – Miscanthus, pasture grass | 425 - 575 oC, dry | 20 – 33% | [66,74] |

| Brewers spent grains | 500 - 850 oC, dry | 15 – 63% | [75,76] |

| Spent mushroom compost | 225 - 250 oC, wet | 34 – 73% | [77] |

| Type of feedstocks | Composting conditions / details | Expected product yield (% w/w) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green wastes – vegetable, household waste | 2 -4 m3/min airflow, covered with insulation, 50 days | 38 – 40% | [79] |

| Green wastes | Forced aeration, heated (30-50 oC), 60 days | 37% | [80] |

| Woody chips, forest residues | uncovered windrows, 100 days | 87% (63% of initial volume) | [81] |

| Bark | uncovered windrows, 100 days | 73% (56% of initial volume) | [81] |

| Hypothetical volumes that can be produced (m3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | Raw | Extruded Fibera |

Biocharb | Hydrocharc | Compostd |

| Wood chips/Slabs | 267 693 | 1 469 635 | 160 616 | 214 154 | 168 647 |

| Sawdust | 88 503 | - | - | - | 55 757 |

| Bark | 132 739 | 728 737 | 79 643 | 106 191 | 74 334 |

| Straw (wheat, barley, oats, oil seed rape, bean, miscanthus, willow) | 838 912 | 4 605 627 | 251 674 | 587 238 | 335 565 |

| Brewers Spent Grain | 202 532 | - | 60 760 | 141 772 | 81 013 |

| Green-wastes – household, municipal and agroc | - | - | - | - | 201 291 |

| Spent mushroom compost | 274 295 | - | 82 289 | 192 007 | 164 577 |

| Total | 1 804 674 | 6 803 999 | 634 982 | 1 241 362 | 1 081 184 |

| Feedstock | Ratio with peat (v/v) | Growth media characteristics | Crops grown | Yield result as compared to control | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD g/L | pH | EC dS/m | |||||

| Scots pine (hammer milled) | 10 – 30% | 95 – 138 | 5.7 – 6.1 | 0.39 – 0.42 |

Radish (Raphanus sativus) | Increased yields by 14 to 24% (compared to 70% peat + 30% perlite control) | [84] |

| Miscanthus (milled and screened) |

100% | 120 – 160 | 6.2 – 6.3 | 0.4 – 0.7 | Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa subsp. Pekinensis) | Reduced yields by -44 to -56% (compared to coir control) | [6] |

| Miscanthus (chopped) |

100% | 100 | 6.3 | 0.3 | Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa subsp. Pekinensis) | Reduced yields by -61% (compared to coir control) | [6] |

| Fresh pine sawdust mixed with composted pine bark | 20 – 70% | nr | 4.5 – 4.8 | 0.07 – 0.09 | Apache pine (Pinus engelmannii) | Mixed results: increased shoot yields by 7 to 17% for 20, 30 & 50% blends but reduced yields by -2 to -12% for 40, 60 and 70% blends (compared to 50% peat + 50% composted bark control) |

[85] |

| Scots pine (disc refined fiber) | 10 – 30% | 70 - 91g | 5.4 - 6 | 0.35 – 0.36 | Radish (Raphanus sativus) | Increased yields by 5 to 15% (compared to 70% peat + 30% perlite control) |

[84] |

| Scots pine (screw extruded fiber) | 10 – 30% | 75 - 130 | 5.2 – 5.7 | 0.3 | Radish (Raphanus sativus) | Reduced shoot yields by -6 to -14% (compared to 70% peat + 30% perlite control) |

[84] |

| wood (disc refined fiber) + sewage sludge | 25 – 100% | 370 | 4.5 | nr | Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) | All reduced yields by about 6% except for the 75% blend | [7] |

| Feedstock & pyrolysis conditions | Ratio with peat (v/v) | Growth media characteristics | Crops grown | Yield result as compared to control | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD g/L | pH | EC dS/m | |||||

| Woody materials biochar | |||||||

| Pine forest residues (450 oC, 48hr) | 25 – 75% | 375 – 505 | 6.6 – 7.8 | 5.5 – 14.6 |

Beach rose (Rosa rugosa Thunb) | All reduced shoot yields by -8 to -57% | [86] |

| Sitka spruce sawmill residues (550 oC, 4mins) | 25 – 100% | 180 – 280 | 5.9 – 9.9 | 0.2 – 0.4 | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | 25 and 50% blends improved shoot yields up to 40% while 75 & 100% blends reduced yields by up to -86% |

[87] |

| Beech spruce & pine mix (400 -700 oC, 15 - 30mins) | 5 – 20% | nr | 5.01 – 5.89 | 0.038 – 0.047 |

Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) | All reduced shoot yields from -30 to 44% | [88] |

| Conifer wood (conditions n.r.) | 25 – 75% | 375 – 505 | 6.5 – 7.8 | 5.5 – 14.6 |

Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) | All reduced shoot yields from -35 to -70% | [89] |

| Beech, spruce and ash mix (450 -600oC, mins n.r.) |

10 – 50% | nr | 5 – 8.3 | 0.21-0.39 | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | All reduced shoot yields from -10 to -53% | [90] |

| Beech, spruce & pine (500 -600oC, mins n.r.) | 7.5 & 15% | nr | 5.1 and 5.4 | 330 and 210 | Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) | Yield reduction of -49 and -6% | [91] |

| Pine wood (450oC) | 20 – 80% | 100 - 160 | nr | nr | Easter Lily (Lilium longiflorum Thunb.) | No significant differences in plant height between all ratios mixes and peat. | [92] |

| Field crop residues biochar | |||||||

| Wheat straw (temperature n.r., 3hrs) | 5 – 15% | 141 - 148 | 5.4 - 5.6 | 1.72 – 1.9 | Marigold (Tagetes patula L.) | Improved shoot yields by 6.5 – 15% | [93] |

| Compost type | Ratio with peat (v/v) | Growth media characteristics | Crops grown | Yield result as compared to control | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD g/L | pH | EC dS/m | |||||

| Green waste | 45% with coir | 210 | 7.8 | 0.77 | Oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare) | Yield increased by 48% | [8] |

| Green waste (mixed green refuse including urban prunings) | 30 - 50% | 180 – 280 | 6.7 – 7.5 | 0.24 – 0.45 |

Geranium (Pelargonium zonale L.) | Increased yields by up to 6.7% except for a 50% blend treatment | [101] |

| Green waste (40% fruit-vegetable waste) |

25 – 30% | 220 – 310 | 5.6 – 6.1 | 1.5 – 1.6 | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Increased shoot yields by range 21 - 62% | [102] |

| Green waste (urban pruning and trimmings) | 30 – 100% | 281 – 365 | 6.7 – 8.4 | 0.71 – 1.44 |

Basil (Ocimum basilicum) | Reduced shoot yields by -20 to –64% | [95] |

| Green waste (municipal + sewage sludge) |

100% | 600 | 7.6 | nr | Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) | Reduced shoot yields by -12% (compared to coir control) | [7] |

| Green waste (botanic wastes) | 25 – 100% | 137 - 176 | nr | nr | Escallonia laevis ‘Gold Brian’, Euonymus europaeus, Viburnum tinus, Euryops pectinatus and Olearia x haastii | Similar yields to peat | [94] |

| Forest residues (willow) | 100% | nr | 7 – 6.6 | 0.2 – 0.3 | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), cucumber (Cucumis sativus) | Reduced yields by -97% for tomato and -74% for cucumber | [97] |

| Composted Spent mushroom compost and pasturised | 20 – 50% (with vermiculite or perlite) | 277 - 396 | 6 – 6.9 | 1.28 – 1.58 | Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) and Tomato (Solanum lycopersi cum) |

Yielded similar biomass yields to peat | [100] |

| Physico-chemical challenges of material | Type of fibre | Reference | Possible solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low N availability – inherent and N immobilisation | Wood: disc refined, grass: milled and paper waste |

[6,7,59] | Increase fertigation rates or initial nutrient application before potting. |

| Low water holding capacity | Wood Grass: milled (miscanthus) |

[64] [6] |

Mix with high water holding materials. Fine mill to < 3mm. |

| High EC - phytotoxic levels of Ca and Na |

Paper waste | [59,107] | Leach media initially. |

| Phytotoxic compounds |

Wood – milled prunnings | [105,108] | Volatile compounds - Change milling method applied (i.e. increase heat and pressure) Soluble compounds - feedstock pre-conditioning (i.e. soaking) Organic acids - incubate with ammonium carbonate |

| Low Ca exchange capacity | Grass (miscanthus) | [6] | Adjust fertigation rates or apply higher starter fertiliser rates. |

| Physico-chemical challenges of material | Biochar feedstock | Reference | Possible solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| High pH | beech, pine, poplar, alder, larch, silver fir and spruce | [86,87,88,89,109] | Leach with water or dilute acid. Mix with other materials. Perform pre-pyrolysis additions (e.g. with phosphates) Adjust pyrolysis conditions to those that reduce ash content. Acidify irrigation water or add of S to growth media |

| High EC (mainly a result of increased available K) | beech, pine, poplar, alder, larch, silver fir and spruce | [86,87,88,89,109] | Leach with water or dilute acid. Sieve out finer particles. Adjust pyrolysis conditions to those that reduce ash content |

| Low available P, Ca, Mg and N | beech, pine, poplar, alder, larch, silver fir and spruce | [86,87,88,89,90,109] | Leach with water or dilute acid. Increase fertiliser rates (might not be feasible) or use slow-release fertilisers. Perform pre-pyrolysis additions (e.g. with phosphates) |

| Low water holding capacity | beech, pine, poplar, alder, larch, silver fir and spruce | [86,87,89,109] | Perform post pyrolysis sieving to < 2mm. Mix with other finer materials. |

| Physio-chemical challenges of material | Compost feedstock | Reference | Possible solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced availability of N | Gorse Ulex europaeus | [111] | Increase N fertiliser rates. Add nutrients pre-composting. |

| High N availability | Mixed green waste | [112] | Reduce N fertigation. |

| High EC; mainly due to high chloride concentration (high salinity) | Mixed green waste | [101] | Mix with inert materials. |

| Low pH | Post consumer wood | [82] | Apply lime. |

| Low water availability | Municipal garden waste and sewage digestate | [7] | Adjust irrigation rates. Mix with other materials. |

| High salinity (K, Na, Ca, Cl, sulphates, and nitrates) | Spent mushroom compost | [60,110] | Mix with other materials, Long-term weathering |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).