Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

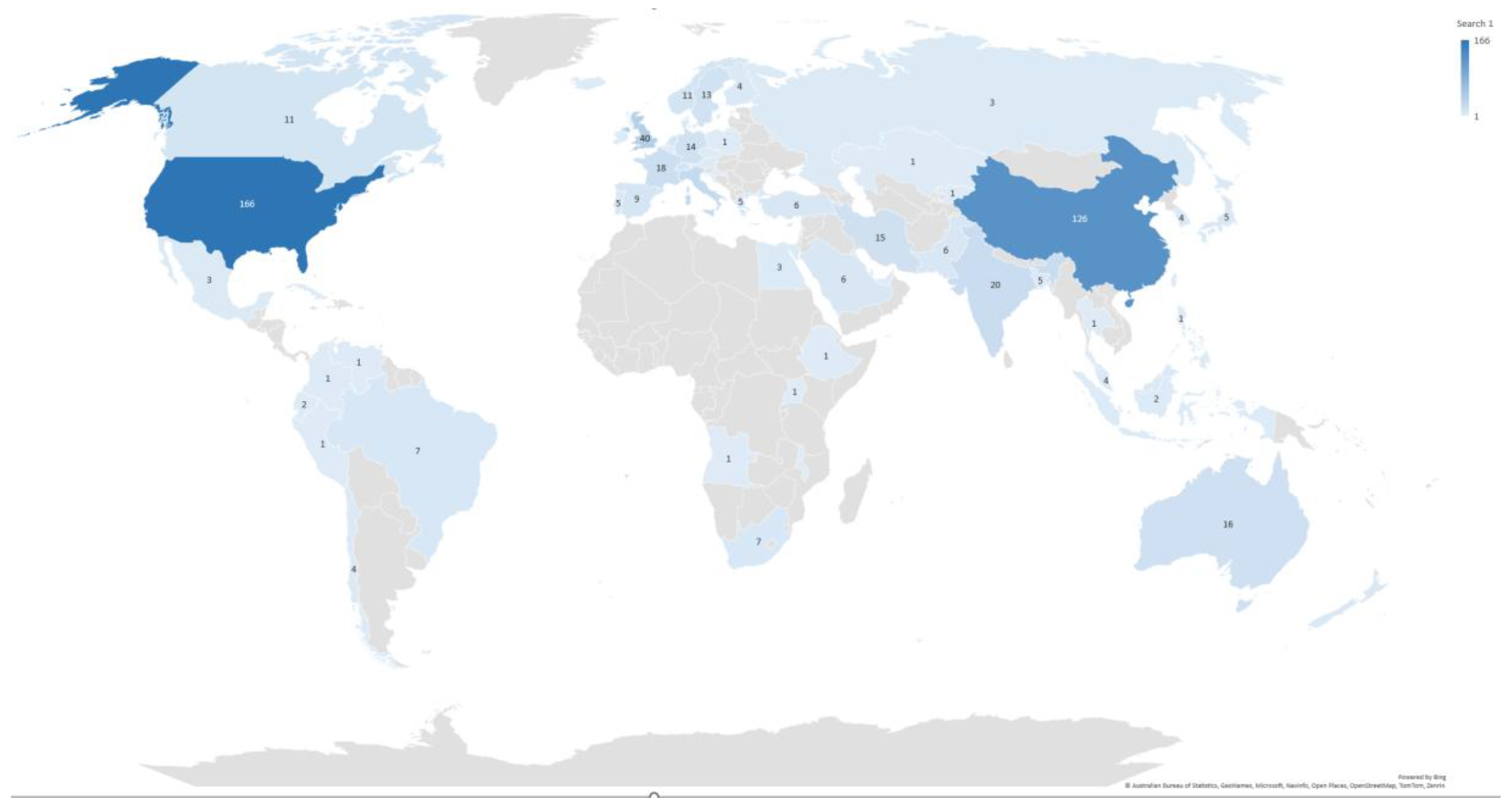

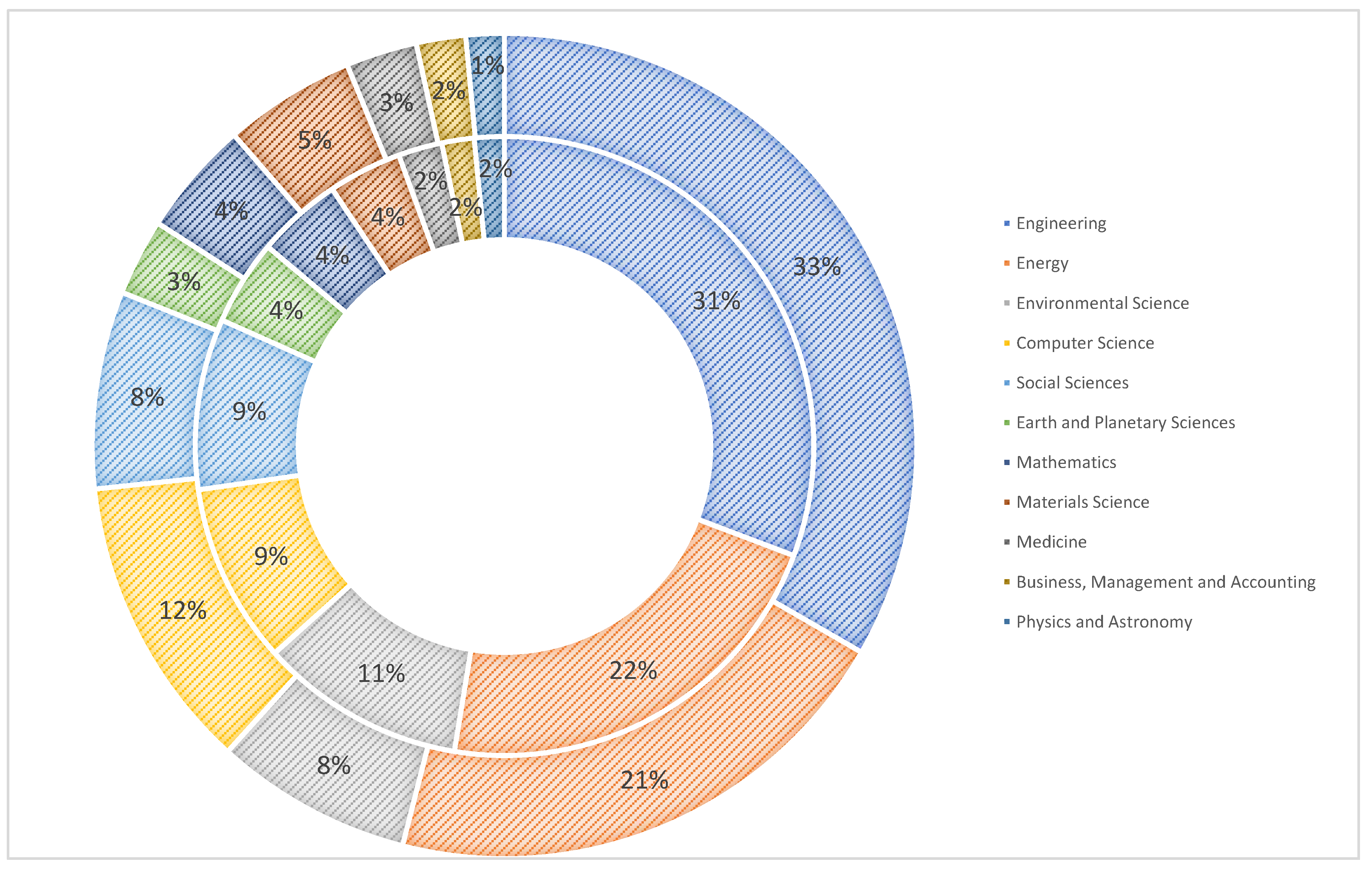

2.1. Systematic Review

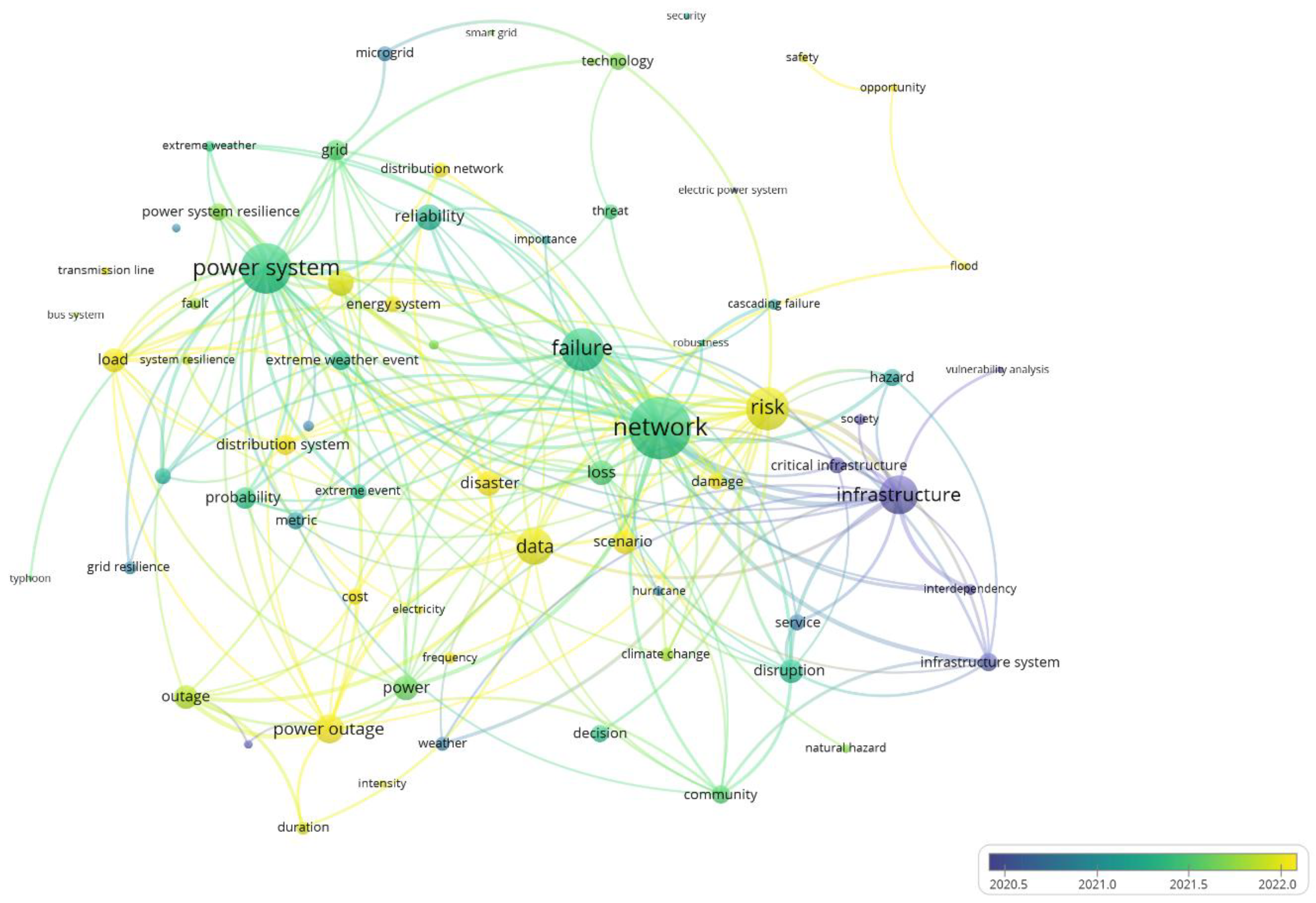

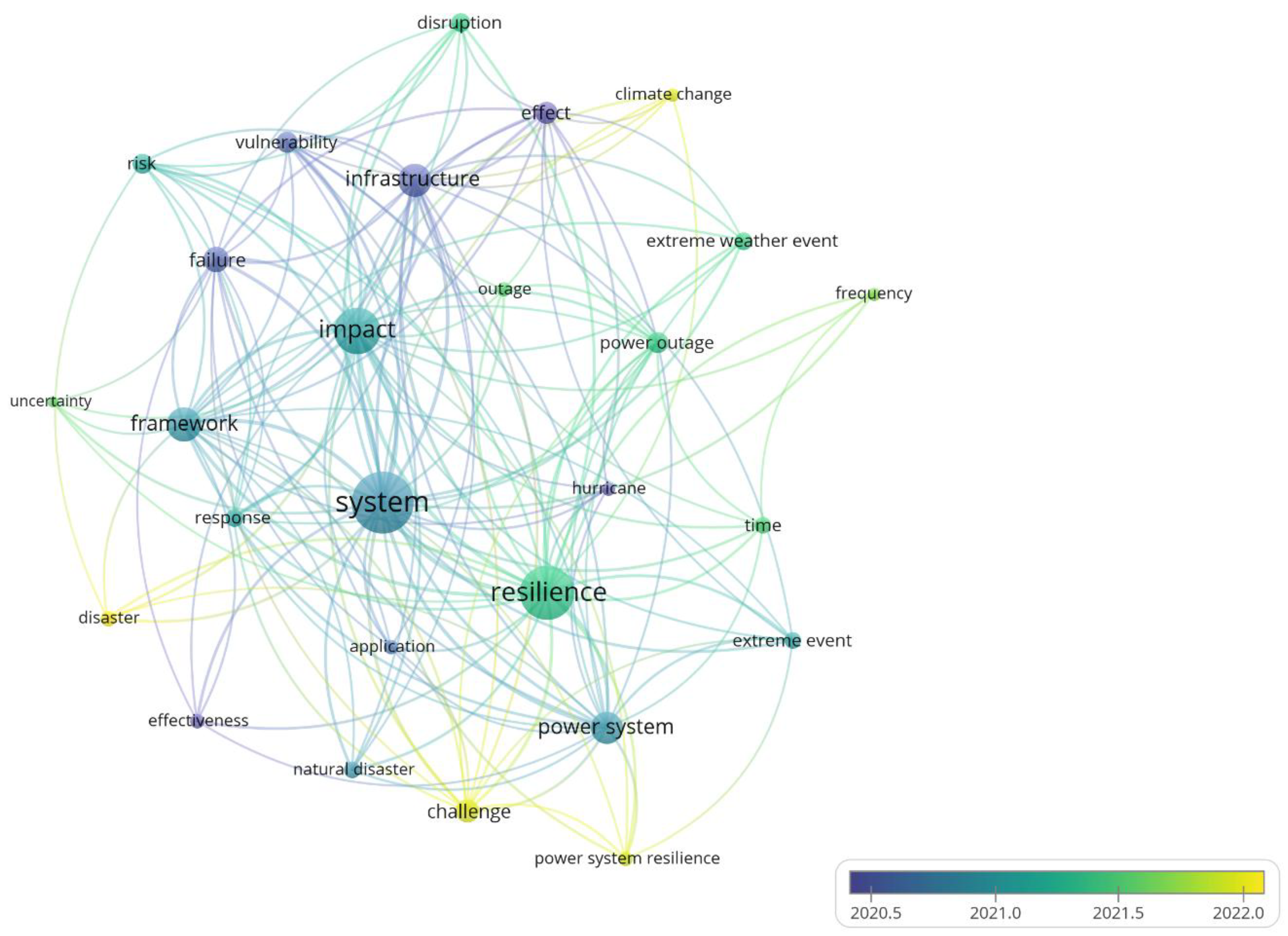

- Power Systems and Resilience: This cluster includes terms like "power system," "grid resilience," "distribution network," and "transmission line." It indicates a strong focus on the technical aspects of electric power grids and their ability to withstand and recover from storm-induced disruptions.

- Extreme Weather Events: Terms such as "extreme event," "hurricane," "typhoon," and "windstorm" fall under this cluster, emphasizing studies related to various types of severe weather phenomena and their impacts on infrastructure.

- Risk and Vulnerability Assessment: This cluster encompasses "risk," "vulnerability analysis," "hazard," and "probability," highlighting the importance of assessing and quantifying risks associated with storms to inform resilience strategies.

- Infrastructure and Interdependencies: Including terms like "critical infrastructure," "interdependency," and "infrastructure system," this cluster underscores the interconnected nature of urban infrastructures and how failures in one system can cascade to others.

- Response and Recovery: Terms such as "disaster," "response," "recovery," and "outage" are part of this cluster, focusing on the strategies and measures for responding to and recovering from storm-induced disruptions.

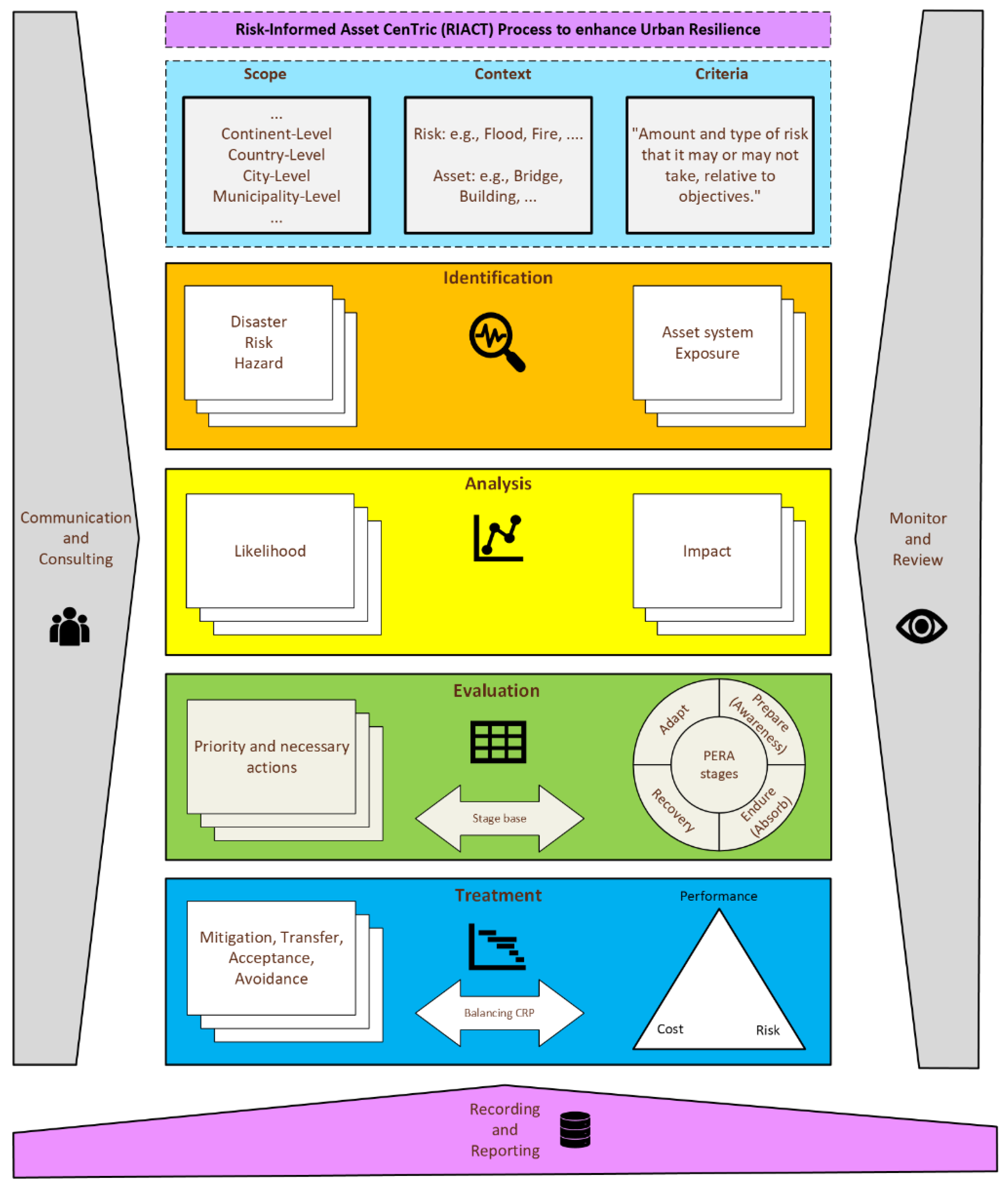

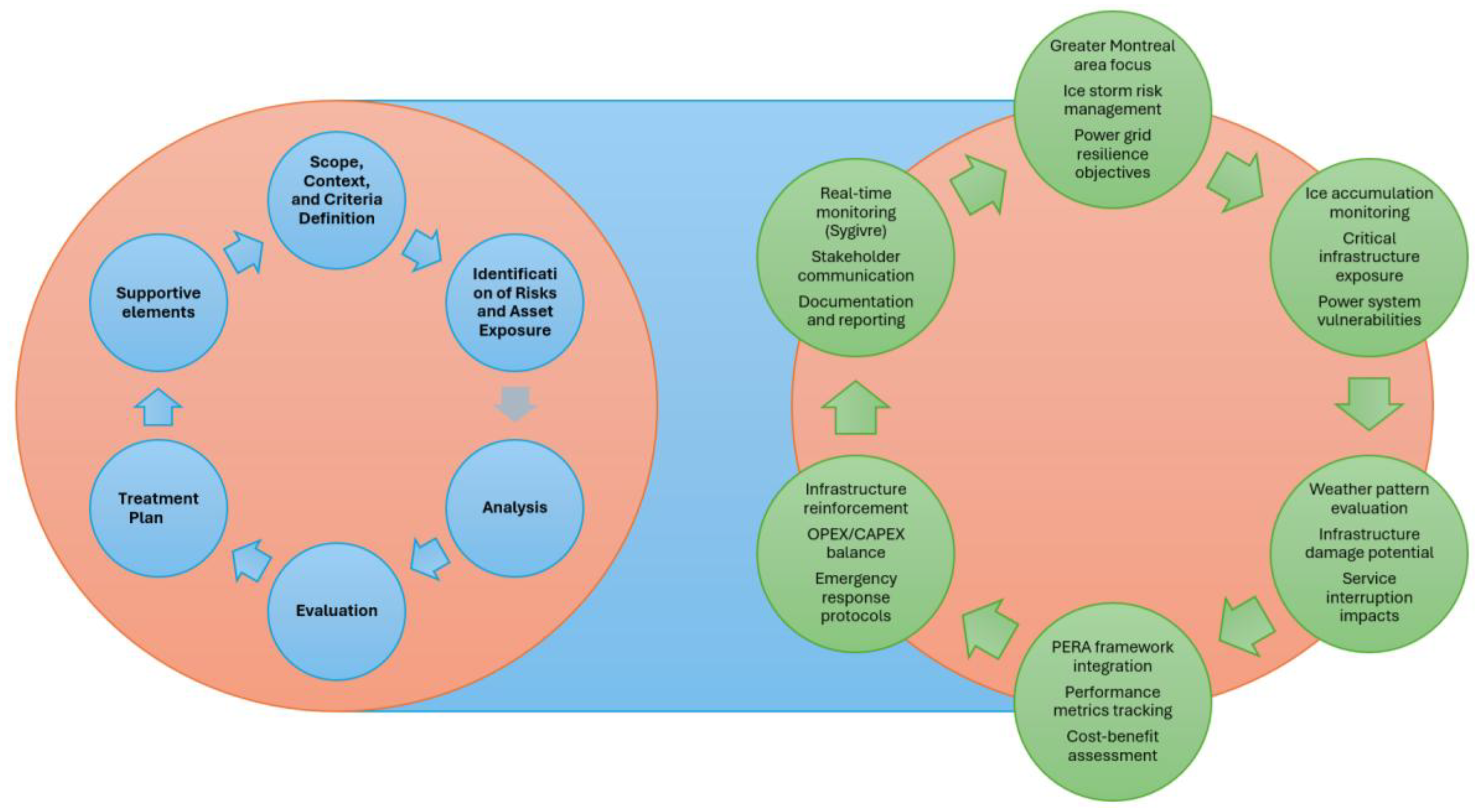

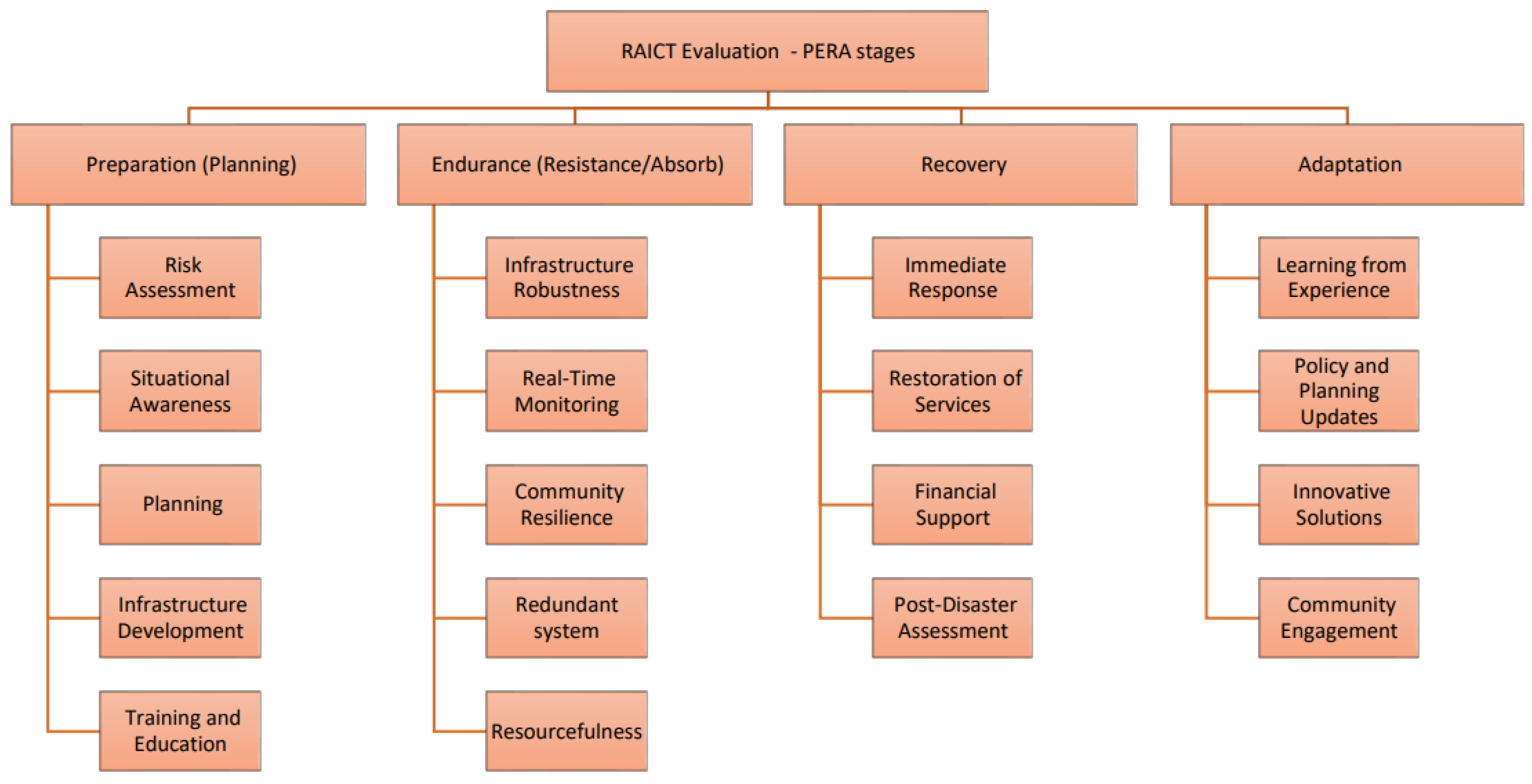

2.2. RIACT Process in Urban Resilience

2.3. Enhancing Grid Resilience and Asset Management in the Face of Ice Storm Impacts

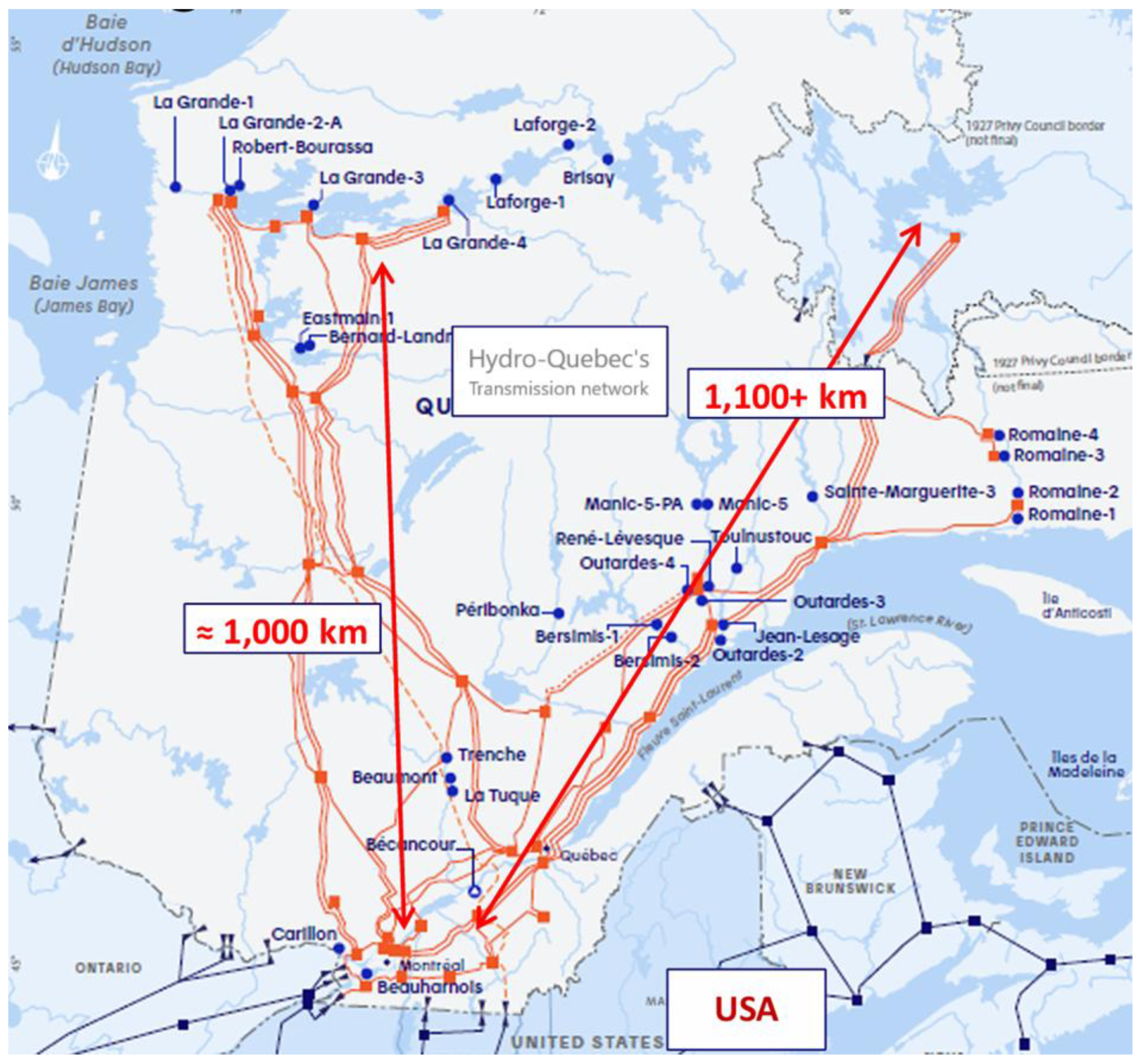

2.4. Overview of the 1998 Quebec Ice Storm and Its Impact on Power Infrastructure

3. Methodology

3.1. Scope, Context, and Criteria Definition

3.2. Identification and Analysis of Risks and Asset Exposure

3.3. Evaluation

3.4. Treatment

3.5. Supportive Elements

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. RIACT Framework Implementation Effectiveness

4.2. PERA Framework Implementation Analysis

4.3. Cost-Benefit Analysis, Technological Integration, and Stakeholder Coordination and Communication

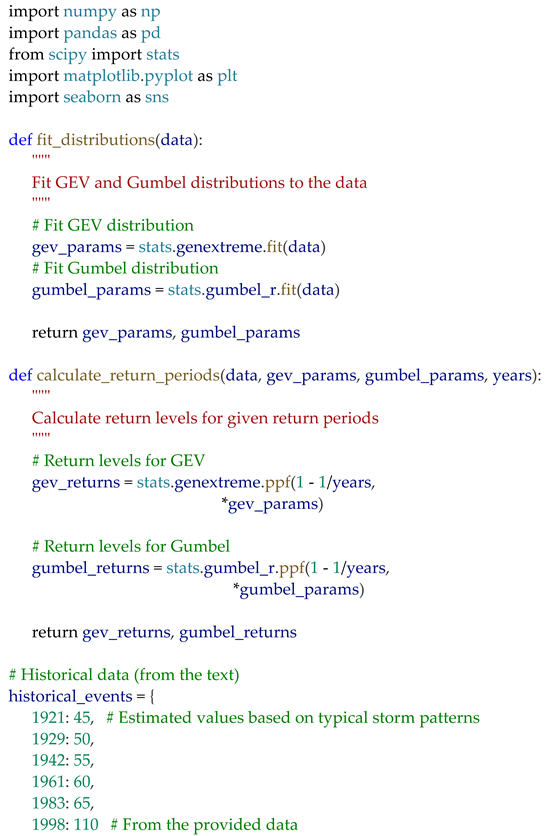

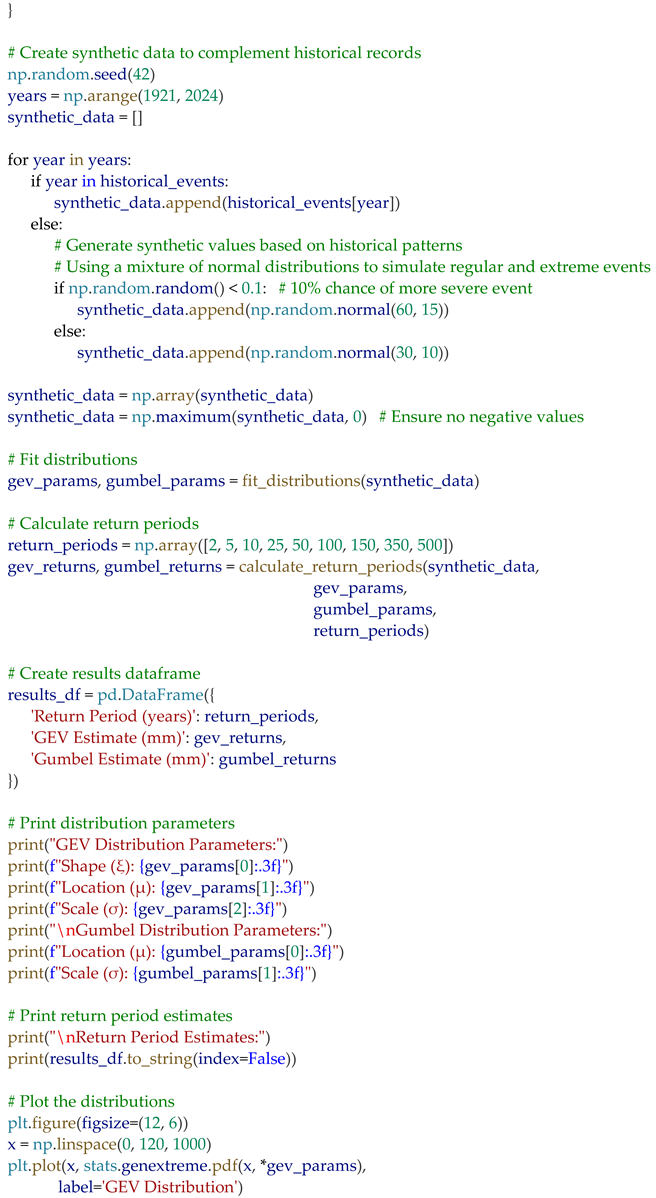

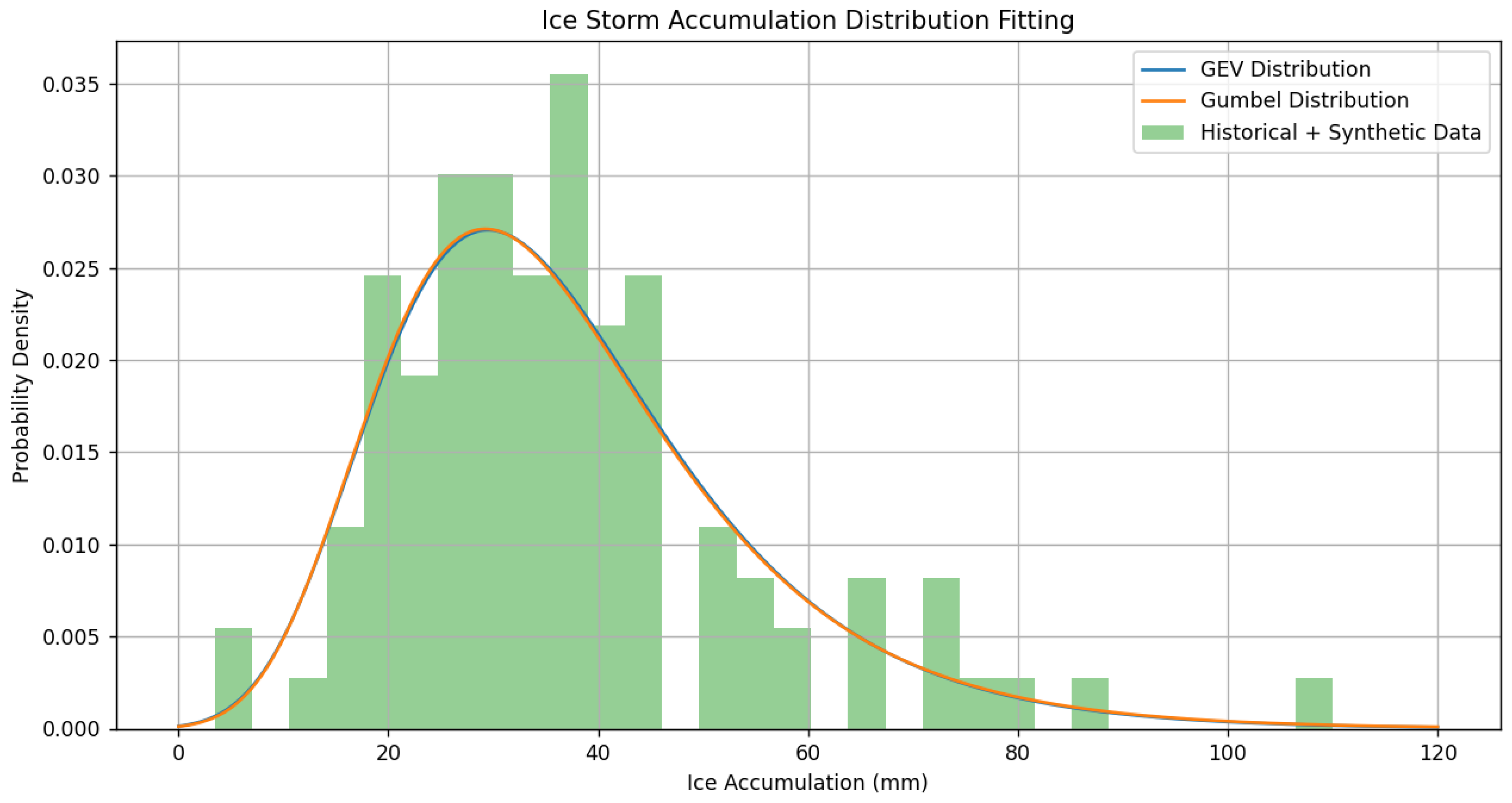

4.4. The Role of Statistical Distributions in Ice Storm Analysis

| 2 | 34.3 | 34.2 |

| 5 | 49.5 | 49.6 |

| 10 | 59.5 | 59.8 |

| 25 | 72.0 | 72.6 |

| 50 | 81.2 | 82.2 |

| 100 | 90.2 | 91.7 |

| 150 | 95.4 | 97.2 |

| 350 | 106.2 | 108.7 |

| 500 | 110.8 | 113.6 |

5. Conclusions, Future Research and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Komljenovic, D. Engineering Asset Management at Times of Major, Large-Scale Instabilities and Disruptions. In Proceedings of the WCEAM 2019; 2021; p. 255270.

- Nicolet, C. Pour Affronter l’imprévisible; Les Enseignements Du Verglas de 98 (Rapport Principal); Gouvernement du Québec: Québec, Canada, 1999.

- Hydro-Québec Annual Report; 2024.

- QUÉBEC, R.D.E.L.D.U. Décision D-2004-175 R-3522-2003; 2004.

- Rezvani, S.M.H.S.; Falcão Silva, M.J.; de Almeida, N.M. The Risk-Informed Asset-Centric (RIACT) Urban Resilience Enhancement Process: An Outline and Pilot-Case Demonstrator for Earthquake Risk Mitigation in Portuguese Municipalities. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, N.; Program, S.; Seminar, T. Risk-Informed Decision-Making in Asset Management of Critical Infrastructures. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arnette, A.N.; Zobel, C.W. A Risk-Based Approach to Improving Disaster Relief Asset Pre-Positioning. Prod Oper Manag 2019, 28, 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, S.M.; Falcão Silva, M.J.; de Almeida, N.M. Urban Resilience Index for Critical Infrastructure: A Scenario-Based Approach to Disaster Risk Reduction in Road Networks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, S.M.; Gonçalves, A.; Silva, M.J.F.; de Almeida, N.M. Smart Hotspot Detection Using Geospatial Artificial Intelligence: A Machine Learning Approach to Reduce Flood Risk. Sustain Cities Soc 2024, 115, 105873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, S.M.H.S.; João, M.; Silva, F.; Marques De Almeida, N. Mapping Geospatial AI Flood Risk in National Road Networks. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2024, Vol. 13, Page 323 2024, 13, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC ISO/IEC 31000:2018 - Risk Management - Principles and Guidelines; 2018; ISBN 2831886376.

- ISO 55000 ISO/CD: 2012. Asset Management - Oveview Principles and Terminology; International Organization for Standardization, 2014.

- ISO 37123 ISO 37123:2019(En), Sustainable Cities and Communities — Indicators for Resilient Cities; 2019.

- Rezvani, S.M.H.S.; Almeida, N.; Silva, M.J.F. Multi-Disciplinary and Dynamic Urban Resilience Assessment Through Stochastic Analysis of a Virtual City; 2023; ISBN 9783031254475.

- Duarte, M.; Almeida, N.; Falcão, M.J.; Rezvani, S.M.H.S. Resilience Rating System for Buildings Against Natural Hazards; 2022; ISBN 9783030967932.

- Rezvani, S.M.H.S.; Almeida, N.; Silva, M.J.F.; Maletič, D. Resilience Exposure Assessment Using Multi-Layer Mapping of Portuguese 308 Cities and Communities; 2023; ISBN 9783031254475.

- Rezvani, S.M.H.S.; Falcão, M.J.; Komljenovic, D.; de Almeida, N.M. A Systematic Literature Review on Urban Resilience Enabled with Asset and Disaster Risk Management Approaches and GIS-Based Decision Support Tools. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, N.M.; Silva, M.J.F.M.J.F.; Salvado, F.; Rodrigues, H.; Maletič, D.; de Almeida, N.M.N.M.; Silva, M.J.F.M.J.F.; Salvado, F.; Rodrigues, H.; Maletič, D. Risk-Informed Performance-Based Metrics for Evaluating the Structural Safety and Serviceability of Constructed Assets against Natural Disasters. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koks, E.E.; Rozenberg, J.; Zorn, C.; Tariverdi, M.; Vousdoukas, M.; Fraser, S.A.; Hall, J.W.; Hallegatte, S. A Global Multi-Hazard Risk Analysis of Road and Railway Infrastructure Assets. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchalogaranjan, V.; Moses, P.; Shumaker, N. Case Study of a Severe Ice Storm Impacting Distribution Networks in Oklahoma. IEEE Trans Reliab 2023, 72, 1442–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wan, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, N.; Deng, R.; Li, B. A Two-Stage Scheduling Model for Urban Distribution Network Resilience Enhancement in Ice Storms. IET Renewable Power Generation 2024, 18, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komljenovic, D.; Abdul-Nour, G.; Popovic, N. An Approach for Strategic Planning and Asset Management in the Mining Industry in the Context of Business and Operational Complexity. Int J Min Miner Eng 2015, 6, 338–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komljenovic, D.; Gaha, M.; Abdul-Nour, G.; Langheit, C.; Bourgeois, M. Risks of Extreme and Rare Events in Asset Management. Saf Sci 2016, 88, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancke, O.; Tahan, A.; Komljenovic, D.; Amyot, N.; Lévesque, M.; Hudon, C. A Holistic Multi-Failure Mode Prognosis Approach for Complex Equipment. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2018, 180, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancke, O.; Combette, A.; Amyot, N.; Komljenovic, D.; Lévesque, M.; Hudon, C.; Tahan, A.; Zerhouni, N. A Predictive Maintenance Approach for Complex Equipment Based on a Failure Mechanism Propagation Model. Int J Progn Health Manag 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komljenovic, D.; Messaoudi, D.; Côté, A.; Gaha, M.; Vouligny, L.; Alarie, S.; Dems, A.; Blancke, O. Asset Management in Electrical Utilities in the Context of Business and Operational Complexity; 2021; ISBN 9783030642273.

- Gaha, M.; Chabane, B.; Komljenovic, D.; Côté, A.; Hébert, C.; Blancke, O.; Delavari, A.; Abdul-Nour, G. Global Methodology for Electrical Utilities Maintenance Assessment Based on Risk-Informed Decision Making. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J.; Komljenovic, D. Situational Awareness: A Road Map to Generation Plant Modernization and Reliability. IEEE Power and Energy Magazine 2024, 22, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel, G.; Gingras, J.P.; Pierre, J.R. Designing a Reliable Power System: Hydro-Québec’s Integrated Approach. Proceedings of the IEEE 2005, 93, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettschneider, S.; Fofana, I. Evolution of Countermeasures against Atmospheric Icing of Power Lines over the Past Four Decades and Their Applications into Field Operations. Energies (Basel) 2021, 14, 6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbing, D. Globally Networked Risks and How to Respond; Nature Publishing Group, 2013; Vol. 497, pp. 51–59.

- Aven, T. The Call for a Shift from Risk to Resilience: What Does It Mean? Risk Analysis 2018, 39, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M.R. Situation Awareness Misconceptions and Misunderstandings. J Cogn Eng Decis Mak 2015, 9, 4–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Nour, G.; Gauthier, F.; Diallo, I.; Komljenovic, D.; Vaillancourt, R.; Côté, A. Development of a Resilience Management Framework Adapted to Complex Asset Systems: Hydro-Québec Research Chair on Asset Management; 2021; ISBN 9783030642273.

- Ghannoum, E. Evolution of IEC 60826 ``Loading and Strength of Overhead Lines’’. Electrical Transmission in a New Age 2002, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenheim, N.; Guidotti, R.; Gardoni, P.; Peacock, W.G. Integration of Detailed Household and Housing Unit Characteristic Data with Critical Infrastructure for Post-Hazard Resilience Modeling. Sustain Resilient Infrastruct 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, T.; Kuckshinrichs, W. Value of Lost Load: An Efficient Economic Indicator for Power Supply Security? A Literature Review. Front Energy Res 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katina, P.F.; Pyne, J.C.; Keating, C.B.; Komljenovic, D. Complex System Governance as a Framework for Asset Management. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, B.; Morabito, L. Success Factors and Lessons Learned during the Implementation of a Cooperative Space for Critical Infrastructures. International Journal of Critical Infrastructures 2024, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachapelle, M.; Thériault, J.M. Characteristics of Precipitation Particles and Microphysical Processes during the 11–12 January 2020 Ice Pellet Storm in the Montréal Area, Québec, Canada. Mon Weather Rev 2022, 150, 1043–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanković, A.M.; Tomsovic, K.L.; De Caro, F.; Braun, M.; Chow, J.H.; Čukalevski, N.; Dobson, I.; Eto, J.; Fink, B.; Hachmann, C.; and, al. Methods for Analysis and Quantification of Power System Resilience. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2023, 38, 4774–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zio, E. Challenges in the Vulnerability and Risk Analysis of Critical Infrastructures. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2016, 152, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, D.D. Four Concepts for Resilience and the Implications for the Future of Resilience Engineering. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2015, 141, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komljenovic, D. Engineering Asset Management at Times of Major, Large-Scale Instabilities and Disruptions. 14th WCEAM Proceedings 2020, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morissette, M.; Komljenovic, D.; Robert, B.; Gravel, J.-F.; Benoit, N.; Lebeau, S.; Fortin, W.; Yaacoub, S.-J.; Leduc, P.; Rioux, P.-J.; and, al. Combining Asset Integrity Management and Resilience in Coping with Extreme Climate Events in Electrical Power Grids. Asset Integrity Management of Critical Infrastructure 2024, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPRI Perspectives on Transforming Utility Business Models: Paper 11 – Business Models for Resilience. Available online: https://www.epri.com/research/products/000000003002030744 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Komljenovic, D.; Guner, I. Role and Importance of Resilience and Engineering Asset Management at Times of Major, Large-Scale Instabilities and Disruptions at Electrical Utilities “Value of Resilience Interest Group (EPRI)” (Slightly Modified). In Proceedings of the Value of Resilience Interest Group (EPRI); Department of Industrial Management, University of Seville, Seville, S., Márquez, A.C., Hydro-Quebec, Varennes, C., Komljenovic, D., Graduate School of Technology Management, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, S.A., Amadi-Echend, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Singapore, 28th – 31st July. 2019., 2021; pp. 255–270.

| Aspect | Details | Phase |

| Investment in System Reliability and Resilience | Invested 1.3 billion CAD in the early 1990s to improve system reliability/resilience. | Preparation |

| Weather Monitoring | 50 weather stations operated for 20 years to monitor weather conditions and ice accumulation. | |

| Transmission lines design | Revised transmission line design criteria to increase the mechanical capacity for radial ice accumulations | |

| Transmission lines Right-of-way | Established transmission line routes criteria limiting the number of lines to maximum two adjacent lines per right-of-way and a minimum distance of 15 km between right-of-way | |

| Duration of ice storm | Lasted from January 5 to January 10, 1998. | Endurance/Absorption |

| Storm magnitude | Considered as a 300-year recurrence event, highlighting its exceptional severity. Three successive storms over the duration | |

| Storm maximum ice accumulation | Reached up to 110 mm. | |

| Storm average ice accumulation | Between 50 and 70 mm. | |

| Impacted area | Affected 400,000 sq km total; 130,000 sq km in Quebec experienced ice accretion exceeding 20 mm. | |

| Infrastructure damage | - 24,000 poles damaged | |

| - 900 steel towers damaged | ||

| - 3,000 km of power lines affected | ||

| Financial impact | Total cost of 1.656 billion CAD; 1.028 billion CAD borne by the Quebec government and Hydro-Québec. | |

| Total Recovery Time | Spanned approximately one month. | Recovery |

| Customer Reconnection | - 80% reconnected within the first week | |

| - Remaining 20% regained power over the subsequent three weeks | ||

| Full Power Restoration | Achieved by February 6, 1998. | |

| Human Resources Deployed | - Hydro-Québec personnel | |

| - Personnel from neighboring utilities | ||

| - 9,000 soldiers assisted in recovery efforts | ||

| - Organized 30 missions, each with ~120 people, including ~50 soldiers per mission | ||

| Cost for High-Risk Substations | 18 million CAD required for work during recovery. | |

| Infrastructure Enhancements | - Added 295 km of new power lines | Adaptation |

| - Reinforced 552 km of existing lines | ||

| New Interconnection | Built a new interconnection to neighboring utility, providing an additional capacity of 1,250 MW. | |

| Transmission Line Design Standards | Reviewed internal transmission line design standard to more stringent criteria than national (CSA) and international standards (IEC). Creation of ice historic accumulation maps to account for climate zones when establishing line route. | |

| Transmission Line Design Standards | Instauration of ice storm recurrence rates: 50-years, 150-year and 500 years rate . | |

| Historical Ice Storms | Major storms occurred in 1921, 1929, 1942, 1961, and 1983—totaling six significant events over the last century. | |

| Transmission Line Extension | Construction of the sturdiest 735 kV transmission line to ensure the electrical supply of the most populated area of the province. | |

| Restoration objectives considered in planning | - Instauration of restauration criteria after a major event, 50% of electrical supply within four days and most of the electrical load within 21 days | |

| Financial Investment | More than 1 billion CAD invested in transmission system improvement projects after the storm. New transmission line upgrades investments have been recently approved and more projects using de-icing technologies are being analyzed. | |

| Transmission grid conception and exploitation philosophy revised and improved | Four basic principles and successive defense barriers have been reviewed at the power grid level. | |

| Ice Storm Scenario Planning | Considered the impact of 75 mm ice accumulation in most severe storm location. | |

| Height Factor Adjustment | Used a reduced height factor of 1,15 to more accurately assess ice thickness on distribution lines, resulting in 65 mm ice thickness on distribution conductors. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).