Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

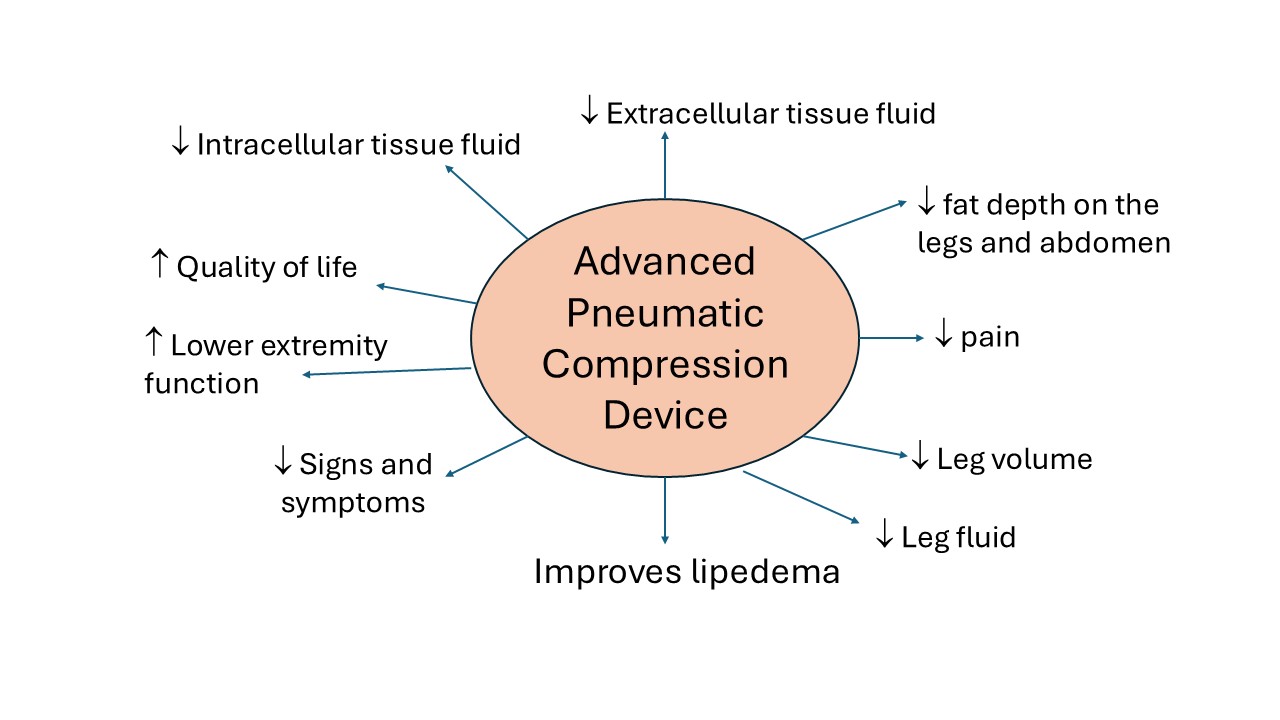

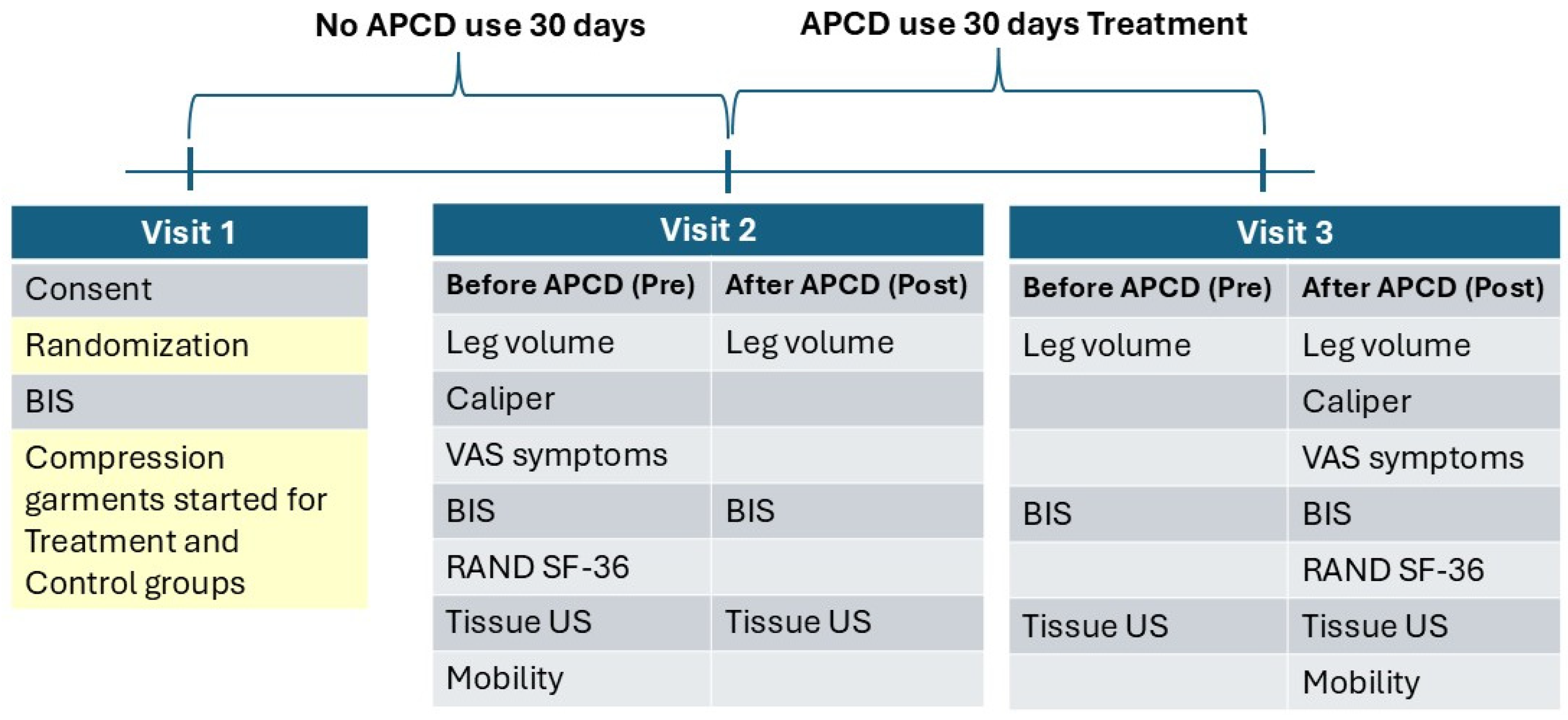

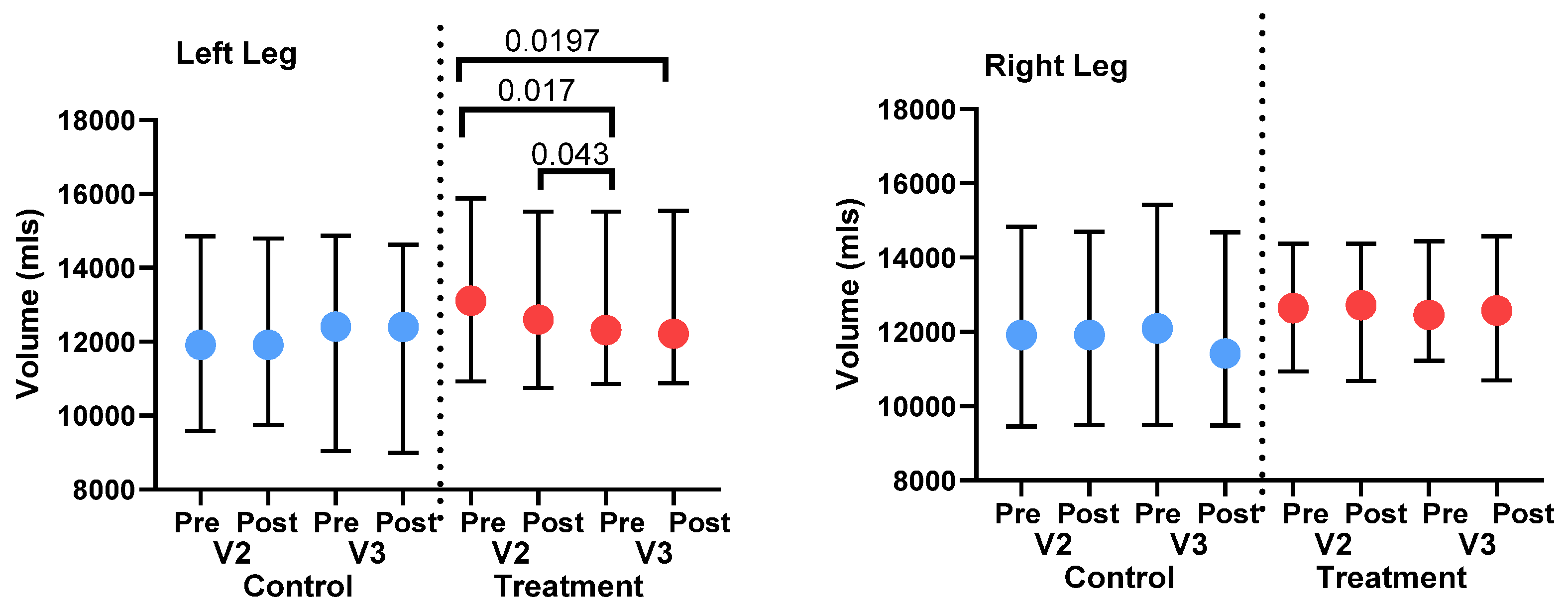

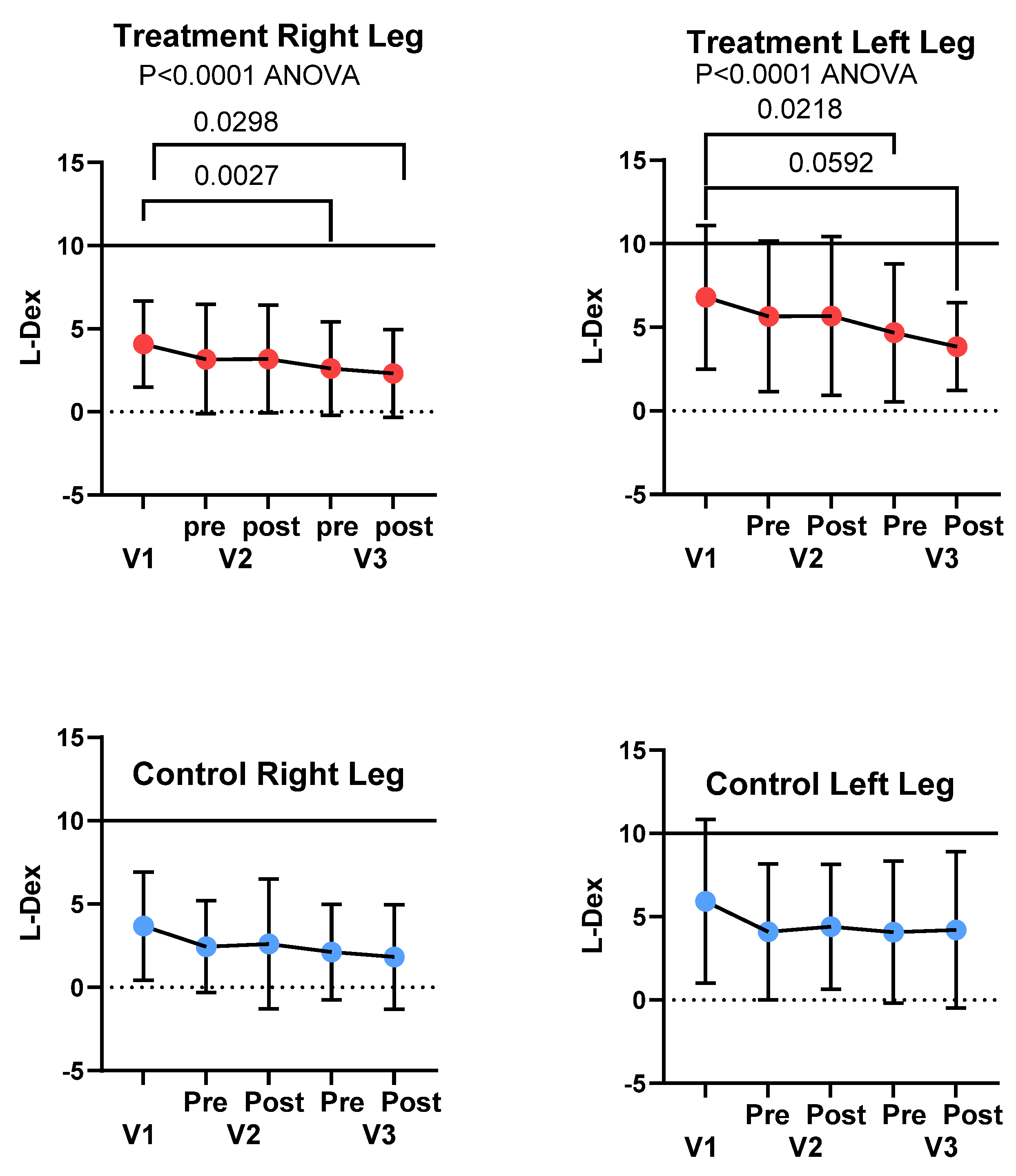

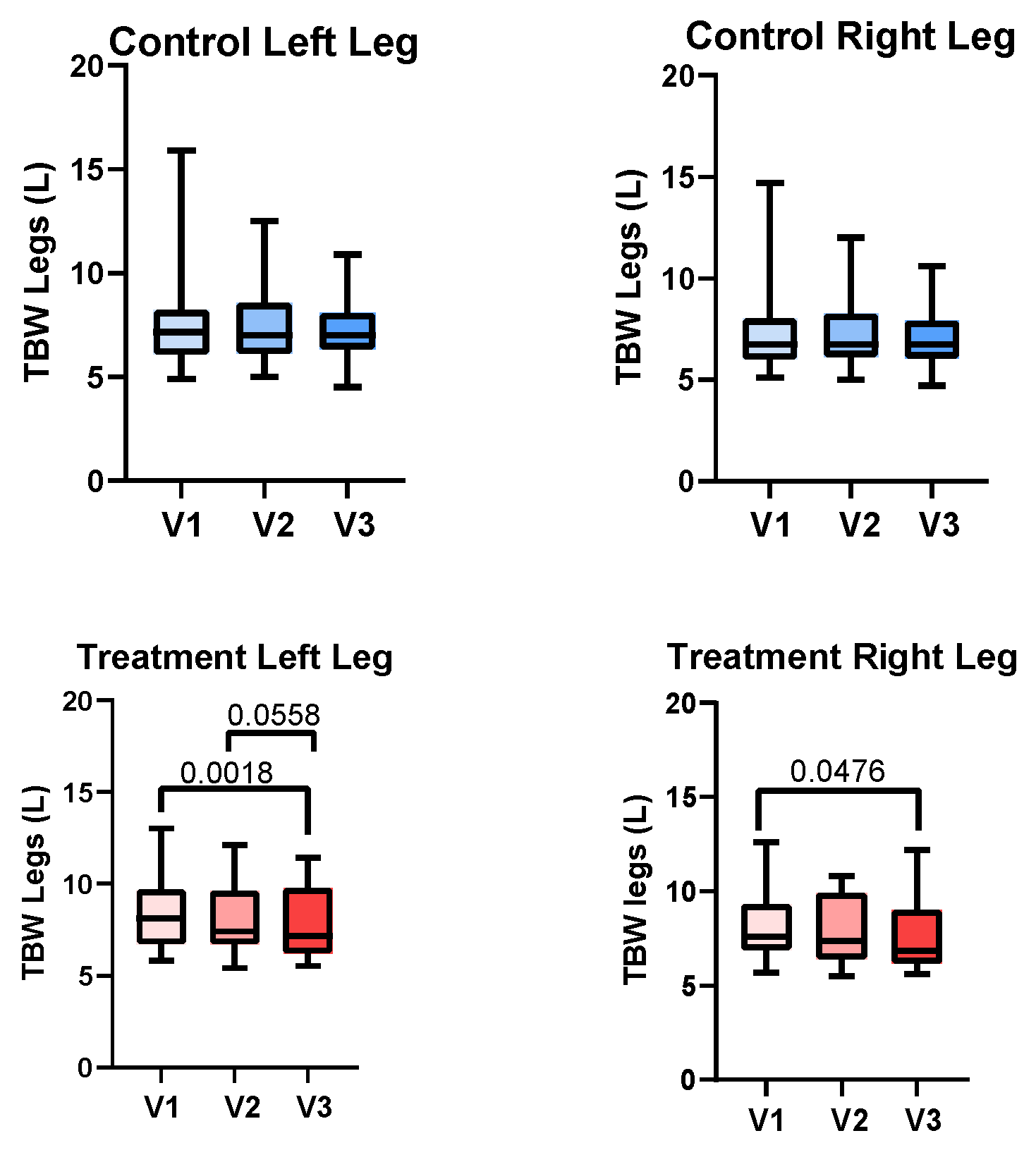

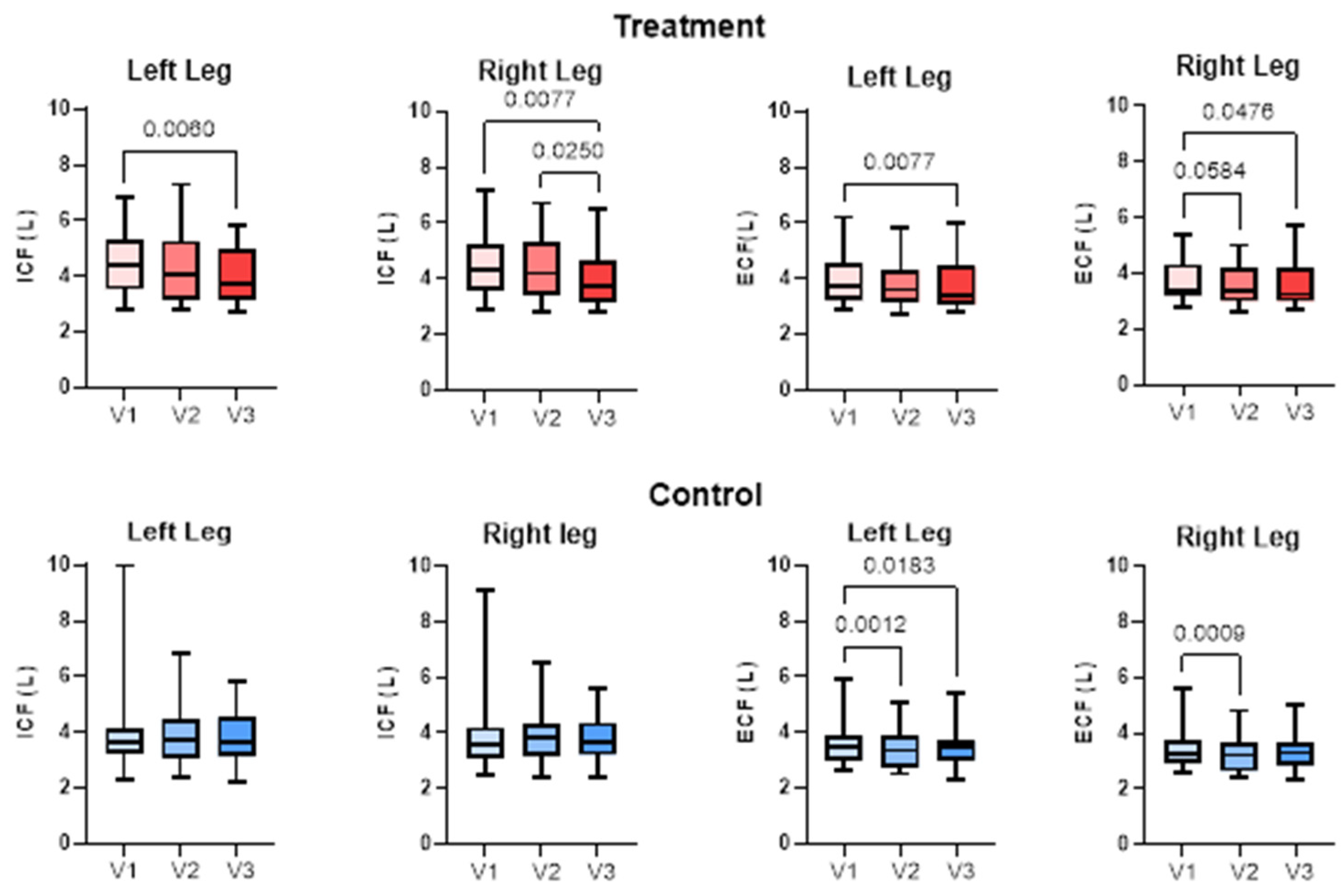

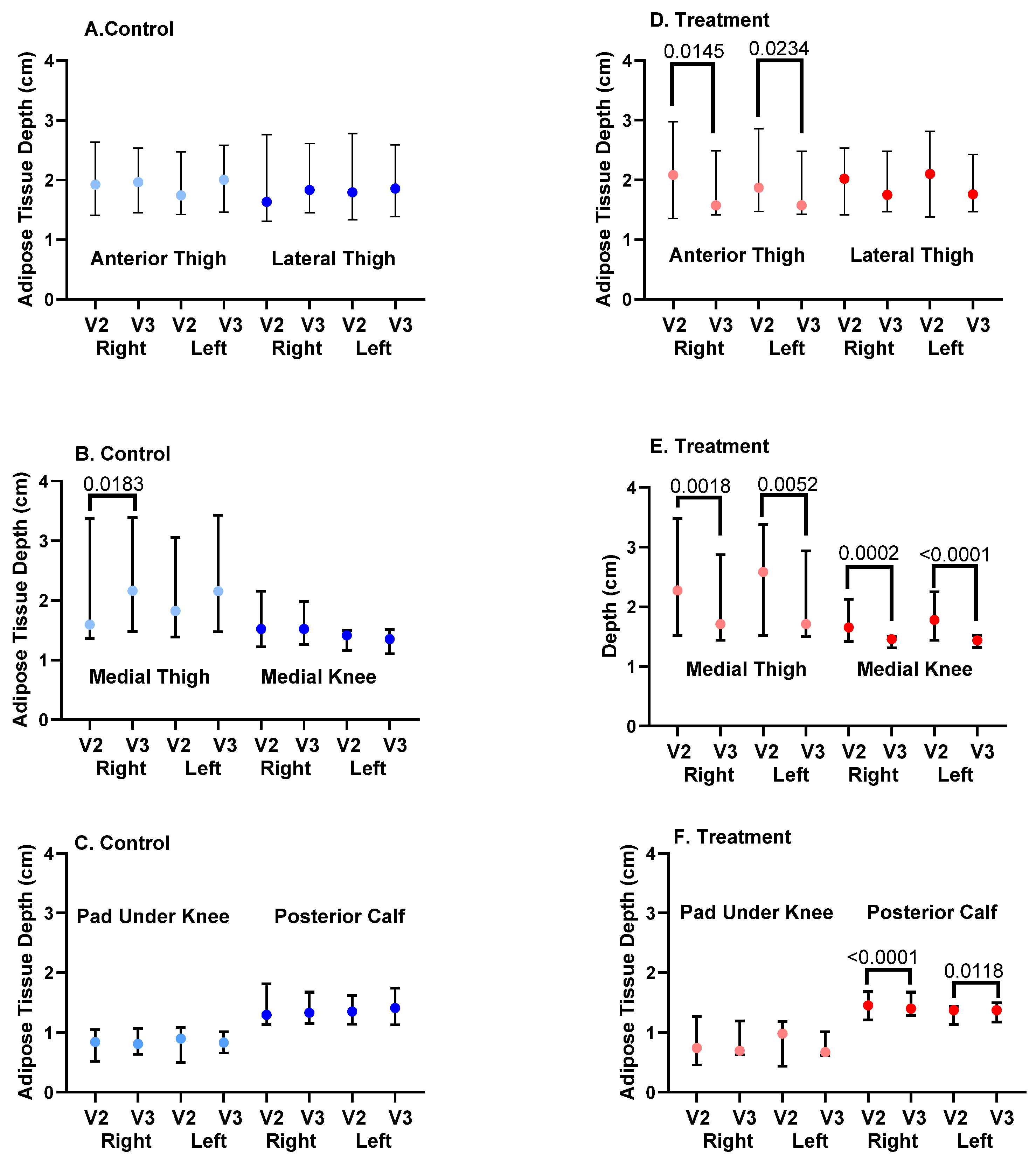

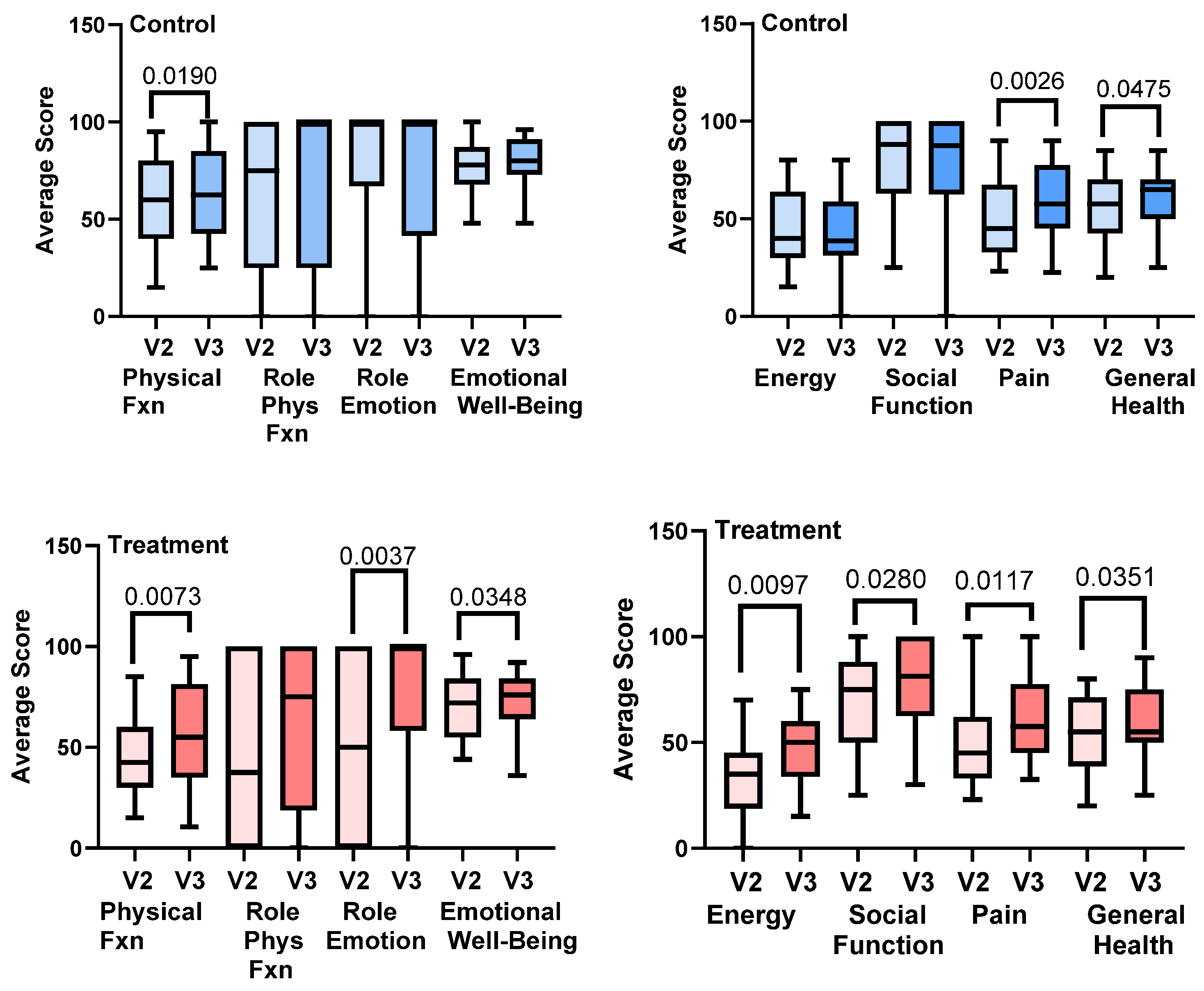

Lipedema is a painful disease of subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) in women. This study determined whether an advanced pneumatic compression device (APCD) improved lipedema SAT depth, swelling and pain. Women with lipedema started 20-30 mm Hg compression leggings then were randomized to an APCD (Lympha Press Optimal Plus) for 30 days (Treatment; n=22) or no APCD (Control; n=24). APCD Treatment significantly reduced left leg volume (3D imaging, LymphaTech; P<0.043) and fluid in the left (P=0.0018) and right legs (P=0.0476; SOZO, bioimpedance spectroscopy); Controls showed no change. Treatment significantly decreased extracellular fluid (ECF) and intracellular fluid (ICF) in left (P=0.0077; P=0.0060) and right legs (P=0.0476; P≤0.025), respectively. Only ECF decreased significantly in the left (P<0.0183) and right legs (P=0.0009) in Controls. SAT depth decreased significantly by ultrasound after Treatment at the anterior (P≤0.0234) and medial thigh (P≤0.0052), medial knee (P≤0.0002) and posterior calf (P≤0.0118) but not in Controls. All signs and symptoms of lipedema improved in the Treatment group including swelling (P=0.0005) and tenderness (pain) of right (P=0.0003) and left legs (P<0.0001); only swelling improved in Controls (P=0.0377). 87.5% of SF-36 quality of life improved after Treatment (P≤0.0351) compared to 37.5% in Controls (P≤0.0475). APCDs are effective treatment for lipedema.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Ambulatory females, age 18 - 70 years.

- Stage 2-3 Type II-III lipedema.

- Pain score with or without pressure in any lipedema area of 3 or more out of 11-point Likert visual analogue scale.

- Able to maintain a consistent eating plan and exercise regimen for the 60-day study with weight stability (within 4.5 kg or usual weight fluctuation per patient) over three months.

- Willing to wear compression garments during the study.

- Agreement to wash off manual therapy of any kind including massage, physical therapy, occupational therapy, instrument assisted soft tissue therapy or other deep tissue therapy and decongestive therapy methods (manual lymph drainage, pneumatic compression use, and compression garment other than provided) over 30 days prior to Visit 2.

- 1.

- Inability to understand the purpose of the study and complete consent.

- 2.

- Bed bound, preventing assessment of activities of daily living.

- 3.

-

Contraindications to APCD use:

- a)

- serious arterial insufficiency measured as a monophasic pulse wave by Doppler (Terason uSmart 3300 - 15L4 uSmart Linear Array Transducer; Burlington, Massachusetts, USA) without arterial disease

- b)

- edema due to decompensated congestive heart failure (CHF) by history or physical exam

- c)

- active phlebitis by physical exam

- d)

- active deep vein thrombosis by history or physical exam

- e)

- localized wound infection by physical exam

- f)

- cellulitis by physical exam

- 4.

- Positive Stemmer sign on the feet.

- 5.

- Lymphedema with minimal to no lipedema.

- 6.

- Weight >170 kg due to weight restriction on bioimpedance spectroscopy device.

- 7.

- Undergoing surgery during the time of the study.

- 8.

- Weight loss surgery within the past 18 months.

- 9.

- Use of diuretic medication.

- 10.

- Participation in other research at the time of the study.

- 11.

- Use of immunosuppressant medications including Gleevec, diosmin, methotrexate, corticosteroids, Plaquenil or other.

- 12.

- Medical illness deemed significant by the Principal Investigator.

- 13.

- Waist to hip ratio > 0.85 suggestive of obesity with lipedema.

- The “Timed up and Go (TUG)” test [27].

- Quantitative assessment of walking several times across a special mat (GAITRite) that records and analyzes the pattern of footsteps [28]. Measurements included right toe location, ambulatory time or velocity, number of steps or cadence, left heel-to-heel or right heel-to-heel base support.

- Lower extremity function scale (LEFS): a questionnaire containing 20 questions about a person’s ability to perform everyday tasks [29].

Leg Volume

3. Results

3.1. Compliance

3.2. Demographics

Quantitative Measures

3.3. Leg volume

3.3.1. Tape Measure

3.3.2. 3D Leg Imaging

3.4. Bioimpedance Spectroscopy

3.5. Caliper

3.6. Timed Up and Go

3.7. Gait-Rite

3.8. Ultrasound Depth of SAT

Qualitative Measures

3.9. Visual Analogue Scales

3.10. RAND-SF-36

3.11. LEFS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APCD | Intermittent pneumatic compression device |

| BIS | Bioimpedance spectroscopy |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| CVI | Chronic venous insufficiency |

| ECF | Extracellular fluid |

| ICF | Intracellular fluid |

| ICG | Indocyanine green |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| MCAS | Mast cell activation syndrome |

| NS | Non-significant |

| PCOS | Polycystic ovarian syndrome |

| POTS | Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome |

| SAT | Subcutaneous adipose tissue |

| SF-36 | RAND Short Form 36-Item Survey |

| US | Ultrasound |

| VAS | Visual analogue scales |

| WHR | Waist to hip ratio |

| WHtR | Waist to height ratio |

References

- B. A. Jagtman, J. P. Kuiper, and A. J. Brakkee, “[Measurements of skin elasticity in patients with lipedema of the Moncorps “rusticanus” type],” Phlebologie., vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 315-9., Jul-Sep 1984.

- K. L. Herbst et al., “Standard of care for lipedema in the United States,” (in eng), Phlebology, Journal Article vol. 36, no. 10, pp. 779-796, Dec 2021.

- K. L. Herbst et al., “Standard of care for lipedema in the United States,” (in eng), Phlebology, Journal Article vol. 28, no. 2683555211015887, p. 2683555211015887, May 28 2021.

- T. Wright, M. Babula, J. Schwartz, C. Wright, N. Danesh, and K. Herbst, “Lipedema Reduction Surgery Improves Pain, Mobility, Physical Function, and Quality of Life: Case Series Report,” (in eng), Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open, vol. 11, no. 11, p. e5436, Nov 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Bast, L. Ahmed, and R. Engdahl, “Lipedema in patients after bariatric surgery,” Surg Obes Relat Dis., vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 1131-2. [CrossRef]

- S. Pouwels, S. Huisman, H. J. M. Smelt, M. Said, and J. F. Smulders, “Lipoedema in patients after bariatric surgery: report of two cases and review of literature,” Clin Obes., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 147-150. [CrossRef]

- S. Pouwels, H. J. Smelt, M. Said, J. F. Smulders, and M. M. Hoogbergen, “Mobility Problems and Weight Regain by Misdiagnosed Lipoedema After Bariatric Surgery: Illustrating the Medical and Legal Aspects,” Cureus., Case Reports vol. 11, no. 8, p. e5388. [CrossRef]

- K. Herbst, L. Mirkovskaya, A. Bharhagava, Y. Chava, and C. H. Te, “Lipedema Fat and Signs and Symptoms of Illness, Increase with Advancing Stage,” Archives of Medicine, vol. 7, no. 4:10, pp. 1-8, 2015.

- S. AL-Ghadban et al., “Dilated Blood and Lymphatic Microvessels, Angiogenesis, Increased Macrophages, and Adipocyte Hypertrophy in Lipedema Thigh Skin and Fat Tissue,” Journal of Obesity, 2019.

- M. Allen, M. Schwartz, and K. L. Herbst, “Interstitial Fluid in Lipedema and Control Skin,” (in eng), Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle), vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 480-487, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Strohmeier et al., “Multi-Level Analysis of Adipose Tissue Reveals the Relevance of Perivascular Subpopulations and an Increased Endothelial Permeability in Early-Stage Lipedema,” Biomedicines, vol. 10, 1163, pp. 1-22, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Rasmussen, M. B. Aldrich, C. E. Fife, K. L. Herbst, and E. M. Sevick-Muraca, “Lymphatic function and anatomy in early stages of lipedema,” (in eng), Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), Journal Article Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t vol. 30, no. 7, pp. 1391-1400, Jul 2022.

- M. Ghods, I. Georgiou, J. Schmidt, and P. Kruppa, “Disease progression and comorbidities in lipedema patients: A 10-year retrospective analysis,” (in eng), Dermatol Ther, Journal Article vol. 33, no. 6, p. e14534, Nov 2020.

- A. C. Amato, J. L. Amato, and D. A. Benitti, “The Association Between Lipedema and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder,” (in eng), Cureus, vol. 15, no. 2, p. e35570, Feb 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Beltran and K. L. Herbst, “Differentiating lipedema and Dercum’s disease,” Int J Obes (Lond). vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 240-245., Feb 2017.

- S. M. Dean, E. Valenti, K. Hock, J. Leffler, A. Compston, and W. T. Abraham, “The clinical characteristics of lower extremity lymphedema in 440 patients,” J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord., vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 851-859. [CrossRef]

- K. L. Herbst, C. Ussery, and A. Eekema, “Pilot study: whole body manual subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) therapy improved pain and SAT structure in women with lipedema,” Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig., Clinical Trial vol. 33, no. 2, pp. /j/hmbci.2018.33.issue-2/hmbci-2017-0035/hmbci-2017-0035.xml. [CrossRef]

- P. M. C. Donahue et al., “Physical Therapy in Women with Early Stage Lipedema: Potential Impact of Multimodal Manual Therapy, Compression, Exercise, and Education Interventions,” (in eng), Lymphat Res Biol, Journal Article vol. 8, no. 10, Nov 8 2021.

- G. Szolnoky, B. Borsos, K. Barsony, M. Balogh, and L. Kemeny, “Complete decongestive physiotherapy with and without pneumatic compression for treatment of lipedema: a pilot study,” (in eng), Lymphology, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 40-4, Mar 2008.

- G. Szolnoky, E. Varga, M. Varga, M. Tuczai, E. Dosa-Racz, and L. Kemeny, “Lymphedema treatment decreases pain intensity in lipedema,” Lymphology., Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 178-82., Dec 2011.

- M. Volkan-Yazıcı, G. Yazici, and M. Esmer, “The Effects of Complex Decongestive Physiotherapy Applications on Lower Extremity Circumference and Volume in Patients with Lipedema,” (in eng), Lymphat Res Biol, Journal Article vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 111-114, Feb 2021.

- M. Volkan-Yazici and M. Esmer, “Reducing Circumference and Volume in Upper Extremity Lipedema: The Role of Complex Decongestive Physiotherapy,” (in eng), Lymphat Res Biol, Journal Article vol. 5, no. 10, Apr 5 2021.

- T. Atan and Y. Bahar-Özdemir, “The Effects of Complete Decongestive Therapy or Intermittent Pneumatic Compression Therapy or Exercise Only in the Treatment of Severe Lipedema: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” (in eng), Lymphat Res Biol, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 86-95, Feb 2021.

- L. E. Wold, E. A. Hines, Jr., and E. V. Allen, “Lipedema of the legs; a syndrome characterized by fat legs and edema,” (in eng), Ann Intern Med, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 1243-50, May 1951.

- Research Randomizer. (1997). Social Psychology Network. [Online]. Available: http://www.randomizer.org/about.htm.

- I. Forner-Cordero, M. V. Perez-Pomares, A. Forner, A. B. Ponce-Garrido, and J. Munoz-Langa, “Prevalence of clinical manifestations and orthopedic alterations in patients with lipedema: A prospective cohort study,” (in eng), Lymphology, Journal Article vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 170-181, 2021.

- A. Christopher, E. Kraft, H. Olenick, R. Kiesling, and A. Doty, “The reliability and validity of the Timed Up and Go as a clinical tool in individuals with and without disabilities across a lifespan: a systematic review,” (in eng), Disabil Rehabil, vol. 43, no. 13, pp. 1799-1813, Jun 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Bilney, M. Morris, and K. Webster, “Concurrent related validity of the GAITRite walkway system for quantification of the spatial and temporal parameters of gait,” (in eng), Gait Posture, Journal Article vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 68-74, Feb 2003.

- J. M. Binkley, P. W. Stratford, S. A. Lott, and D. L. Riddle, “The Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network,” Phys Ther., vol. 79, no. 4, pp. 371-83., 1999.

- M. Ibarra, A. Eekema, C. Ussery, D. Neuhardt, K. Garby, and K. L. Herbst, “Subcutaneous adipose tissue therapy reduces fat by dual X-ray absorptiometry scan and improves tissue structure by ultrasound in women with lipoedema and Dercum disease,” Clin Obes., vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 398-406. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Casley-Smith, “Measuring and representing peripheral oedema and its alterations,” Lymphology, vol. 27, 2, pp. 56-70, 1994.

- C. Yahathugoda et al., “Use of a Novel Portable Three-Dimensional Imaging System to Measure Limb Volume and Circumference in Patients with Filarial Lymphedema,” (in eng), Am J Trop Med Hyg, vol. 97, no. 6, pp. 1836-1842, Dec 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Binkley, M. J. Weiler, N. Frank, L. Bober, J. B. Dixon, and P. W. Stratford, “Assessing Arm Volume in People During and After Treatment for Breast Cancer: Reliability and Convergent Validity of the LymphaTech System,” (in eng), Phys Ther, vol. 100, no. 3, pp. 457-467, Mar 10 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Ware, Jr. and C. D. Sherbourne, “The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection,” (in eng), Med Care, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 473-83, Jun 1992.

- B. H. Duhon, T. T. Phan, S. L. Taylor, R. L. Crescenzi, and J. M. Rutkowski, “Current Mechanistic Understandings of Lymphedema and Lipedema: Tales of Fluid, Fat, and Fibrosis,” (in eng), Int J Mol Sci, vol. 23, no. 12, Jun 14 2022.

- L. M. Pereira de Godoy, H. J. Pereira de Godoy, P. Pereira de Godoy Capeletto, M. F. Guerreiro Godoy, and J. M. Pereira de Godoy, “Lipedema and the Evolution to Lymphedema With the Progression of Obesity,” (in eng), Cureus, vol. 12, no. 12, p. e11854, Dec 2 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Coppel et al., “Best Practice Guidelines: The management of lipoedema.,” Wounds UK, vol. 13, no. 1. [Online]. Available: http://www.wounds-uk.com/best-practice-statements/best-practice-guidelines-the-management-of-lipoedema.

- I. Forner-Cordero, G. Szolnoky, A. Forner-Cordero, and L. Kemény, “Lipedema: an overview of its clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of the disproportional fatty deposition syndrome - systematic review,” Clinical Obesity, vol. 2, no. 3-4, pp. 86-95, June 2012.

- J. M. Alcolea et al., “Documento de Consenso Lipedema 2018,” in 33rd National Congress of the Spanish Society of Aesthetic Medicine (SEME), Malaga, Spain, 2018, Barcelona, Spain: LITOGAMA S.L., 2018.

- M. Sandhofer et al., “Prevention of Progression of Lipedema With Liposuction Using Tumescent Local Anesthesia: Results of an International Consensus Conference,” Dermatol Surg., vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 220-228. [CrossRef]

- T. Bertsch et al., “Lipoedema – myths and facts, Part 5. European Best Practice of Lipoedema – Summary of the European Lipoedema Forum consensus,” Phlebologie, vol. 49, pp. 31-49, 2020.

- S. Reich-Schupke, P. Altmeyer, and M. Stücker, “Thick legs not always lipedema.,” J Dtsch Dermatol Ges., vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 225-233, 2013.

- S. Russo et al., “Standardization of lower extremity quantitative lymphedema measurements and associated patient-reported outcomes in gynecologic cancers,” (in eng), Gynecol Oncol, vol. 160, no. 2, pp. 625-632, Feb 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Coroneos, F. C. Wong, S. M. DeSnyder, S. F. Shaitelman, and M. V. Schaverien, “Correlation of L-Dex Bioimpedance Spectroscopy with Limb Volume and Lymphatic Function in Lymphedema,” (in eng), Lymphat Res Biol, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 301-307, Jun 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Gillham and D. Sidebotham, “Chapter 32 - Water and Electrolyte Disturbances,” in Cardiothoracic Critical Care, D. Sidebotham, A. McKee, M. Gillham, and J. H. Levy Eds. Philadelphia: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2007, pp. 470-480.

- L. Weiss, Histology: Cell and Tissue Biology. Elsevier Biomedical, 1983.

- D. L. Costill, R. Coté, and W. Fink, “Muscle water and electrolytes following varied levels of dehydration in man,” (in eng), J Appl Physiol, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 6-11, Jan 1976. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Durkot, O. Martinez, D. Brooks-McQuade, and R. Francesconi, “Simultaneous determination of fluid shifts during thermal stress in a small-animal model,” (in eng), J Appl Physiol (1985), vol. 61, no. 3, pp. 1031-4, Sep 1986. [CrossRef]

- E. Hvidberg, “Water-binding by connective tissue and the acid mucopolysaccharides of the ground substance,” Acta pharmacologica et toxicologica, vol. 17, pp. 267-76, 2009.

- K. Comley and N. Fleck, “The compressive response of porcine adipose tissue from low to high strain rate,” International Journal of Impact Engineering, vol. 46, pp. 1-10, 2012/08/01/ 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. Suga, J. Araki, N. Aoi, H. Kato, T. Higashino, and K. Yoshimura, “Adipose tissue remodeling in lipedema: adipocyte death and concurrent regeneration,” J Cutan Pathol, vol. 3, p. 3, 2009.

- G. Felmerer et al., “Adipose Tissue Hypertrophy, An Aberrant Biochemical Profile and Distinct Gene Expression in Lipedema,” J Surg Res., vol. 253:294-303., no. doi, p. 10.1016/j.jss.2020.03.055., May 11 2020.

- R. Crescenzi et al., “Upper and Lower Extremity Measurement of Tissue Sodium and Fat Content in Patients with Lipedema,” (in eng), Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 907-915, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. H. Hui, Z. L. Zhou, J. Qian, Y. Lin, A. H. Ngan, and H. Gao, “Volumetric deformation of live cells induced by pressure-activated cross-membrane ion transport,” (in eng), Phys Rev Lett, vol. 113, no. 11, p. 118101, Sep 12 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Tobias, B. D. Ballard, and S. S. Mohiuddin, “Physiology, Water Balance. [Updated 2022 Oct 3],” StatPearls [Internet]Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541059/.

- J. van Esch-Smeenge, R. J. Damstra, and A. A. Hendrickx, “Muscle strength and functional exercise capacity in patients with lipoedema and obesity: a comparative study,” Journal of Lymphoedema, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 27-31, 2017.

- Y. Li et al., “Compression-induced dedifferentiation of adipocytes promotes tumor progression,” (in eng), Sci Adv, vol. 6, no. 4, p. eaax5611, Jan 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Chakraborty et al., “Indications of Peripheral Pain, Dermal Hypersensitivity, and Neurogenic Inflammation in Patients with Lipedema,” (in eng), Int J Mol Sci, Journal Article vol. 23, no. 18, Sep 7 2022.

- R. W. Bohannon, “Reference values for the timed up and go test: a descriptive meta-analysis,” (in eng), J Geriatr Phys Ther, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 64-8, 2006. [CrossRef]

- V. A. Benites-Zapata et al., “High waist-to-hip ratio levels are associated with insulin resistance markers in normal-weight women,” (in eng), Diabetes Metab Syndr, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 636-642, Jan-Feb 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Schneider et al., “The predictive value of different measures of obesity for incident cardiovascular events and mortality,” (in eng), The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, vol. 95, no. 4, pp. 1777-85, Apr 2010. [CrossRef]

- E. Brenner, I. Forner-Cordero, G. Faerber, S. Rapprich, and M. Cornely, “Body mass index vs. waist-to-height-ratio in patients with lipohyperplasia dolorosa (vulgo lipedema),” (in eng), J Dtsch Dermatol Ges, vol. 21, no. 10, pp. 1179-1185, Oct 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Bulbena, J. Gago, G. Pailhez, L. Sperry, M. A. Fullana, and O. Vilarroya, “Joint hypermobility syndrome is a risk factor trait for anxiety disorders: a 15-year follow-up cohort study,” Gen Hosp Psychiatry., vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 363-70. [CrossRef]

- K. Amin, “The role of mast cells in allergic inflammation,” Respiratory Medicine, vol. 106, no. 1, pp. 9-14, 2012/01/01/ 2012. [CrossRef]

- G. Bonetti et al., “Targeting Mast Cells: Sodium Cromoglycate as a Possible Treatment of Lipedema,” (in eng), Clin Ter, vol. 174, no. Suppl 2(6), pp. 256-262, Nov-Dec 2023. [CrossRef]

| Demographic | Group (N) | P-value* | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (24) | Treat (22) | |||

| Age | 48.8±8.5 | 52±9.2 | NS | 50.3±8.9 |

| Female/Male | 24/0 | 22/0 | NS | 46 |

| Race: White/Black | 23/2 | 16/5 | NS | 39/7 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 122.5±16 | 124.7±14 | NS | 123.5±15 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 79.3±8.5 | 80.5±8 | NS | 72.8±9 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 73.5±8.3 | 72±10.4 | NS | 72.8±9 |

| Height (cm) | 161±7 | 161.6±6.6 | NS | 161.3±6.7 |

| Weight (kg) | 94.9±23 | 104.7±22 | NS | 99.4±22.7 |

| Waist (cm) | 92.4±13 | 98.4±11.4 | NS | 95.2±13 |

| Hips (in) | 121.1±17 | 130.4±15 | NS | 125.3±6.7 |

| WHR | 0.76±0.04 | 0.75±0.05 | NS | 0.76±0.05 |

| WHtR | 0.57±0.08 | 0.61±0.07 | NS | 0.59±0.07 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.3±7 | 38.9±7.5 | NS | 37±7.4 |

| Lipedema Stages | Control (number) | Treatment (number) | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 23 | 20 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Medical History | Control (%) | Treatment (%) | ||

| Migraine +/- aura | 20 / 24 | 33 / 14 | ||

| Depression | 24 | 48 | ||

| Anxiety | 40 | 52 | ||

| Allergies | 100 | 95 | ||

| Hypertension | 8 | 29 | ||

| Prediabetes/Diabetes | 20 / 12 | 14 / 9.5 | ||

| Pregnant (ever) | 84 | 86 | ||

| Miscarriage | 32 | 33.3 | ||

| Birth Control | 92 | 90 | ||

| Menopause | 40 | 62 | ||

| Asthma COPD | 16 | 28.5 | ||

| Thyroid Disease | 28 | 38 | ||

| Control (Mean±SD) | Treatment (Mean±SD) | |||

| Age 1st menstruation | 12.4±1.9 | 12.2±1.3 | ||

| Times pregnant | 2.3±1.7 | 2.1±2.0 | ||

| Age menopause | 50.2±4.2 | 46.7±7 | ||

| Surgical History | Control (%) | Treatment (%) | ||

| Bariatric | 16 | 33.3 | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 64 | 52 | ||

| Musculoskeletal | 32 | 43 | ||

| Reproductive | 72 | 67 | ||

| *NS=non-significant; BMI=body mass index; BP=blood pressure; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; WHR=waist to hip ratio; WHtR=waist to height ratio. | ||||

| Location | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control Group | |||

| Under Umbilicus | 40.3±17.3 | 40.5±14.8 | NS |

| Right Anterior Thigh | 61.1±6.3 | 62.2±4.8 | NS |

| Right medial Thigh | 55.2±9.1 | 56.9±7 | NS |

| Left Anterior Thigh | 60.8±6.4 | 62.6±5 | NS |

| Left Medial Thigh | 55.5±9.3 | 57.9±7 | NS |

| Treatment Group | |||

| Under Umbilicus | 45.1±14.3 | 38.9±14.4 | 0.0279 |

| Right Anterior Thigh | 63.8±4.7 | 64.1±4.4 | NS |

| Right medial Thigh | 57.1±8 | 58.8±7 | NS |

| Left Anterior Thigh | 62.2±6.8 | 64.1±4 | NS |

| Left Medial Thigh | 58.1±7.5 | 59±9 | NS |

| Adipose Tissue Location | Control (n=24) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 2 | P-value | Visit 3 | P-value | |||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||||

| Right Leg | ||||||||

| Anterior thigh | 2.2±1 | 2.1±1.0 | NS | 2.3±1.0 | 2.3±1.0 | NS | ||

| Lateral thigh | 2.1±1.1 | 2.1±1.0 | NS | 2.2±0.9 | 2.2±0.9 | NS | ||

| Medial thigh | 2.3±1.2 | 2.3±1.3 | NS | 2.5±1.1 | 2.5±1.2 | NS | ||

| Medial knee | 1.9±1.1 | 1.6±0.7 | NS | 1.5±0.5 | 1.4±0.5 | NS | ||

| Pad under knee | 0.84±0.4 | 0.8±0.4 | NS | 0.94±0.5 | 0.94±0.5 | NS | ||

| Posterior calf | 1.44±0.5 | 1.4±0.4 | NS | 1.4±0.4 | 1.4±0.4 | NS | ||

| Left Leg | ||||||||

| Anterior thigh | 2.1±0.9 | 2.2±0.9 | NS | 2.2±1.0 | 2.2±1.1 | NS | ||

| Lateral thigh | 2.1±1.0 | 2.1±0.8 | NS | 2.2±0.9 | 2.2±0.9 | NS | ||

| Medial thigh | 2.3±1.2 | 2.3±1.2 | NS | 2.5±1.1 | 2.5±1.2 | NS | ||

| Medial knee | 1.7±0.7 | 1.6±0.7 | NS | 1.4±0.5 | 1.4±0.5 | NS | ||

| Pad under knee | 0.82±0.4 | 0.89±0.4 | NS | 1.0±0.5 | 0.95±0.5 | NS | ||

| Posterior calf | 1.5±0.5 | 1.4±0.4 | NS | 1.4±0.4 | 1.5±0.4 | NS | ||

| Adipose Tissue Location | Treatment (n=22) | |||||||

| Visit 2 | P-value | Visit 3 | P-value | |||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||||

| Right Leg | ||||||||

| Anterior thigh | 2.3±1.0 | 2.1±0.9 | 0.009 | 2.1±0.8 | 2.0±0.8 | NS | ||

| Lateral thigh | 2.2±0.9 | 2.1±0.8 | NS | 2.1±0.6 | 2.0±0.6 | NS | ||

| Medial thigh | 2.6±1.2 | 2.5±0.9 | NS | 2.3±1.0 | 2.2±0.9 | 0.0097 | ||

| Medial knee | 1.9±0.7 | 1.7±0.5 | NS | 1.5±0.3 | 1.4±0.2 | 0.0097 | ||

| Pad under knee | 0.86±0.4 | 0.74±0.4 | 0.025 | 0.9±0.4 | 0.9±0.4 | NS | ||

| Posterior calf | 1.5±0.3 | 1.4±0.3 | 0.036 | 1.4±0.2 | 1.3±0.2 | NS | ||

| Left Leg | ||||||||

| Anterior thigh | 2.2±1.0 | 2.1±0.9 | 0.007 | 2.1±0.8 | 2.0±0.8 | NS | ||

| Lateral thigh | 2.2±0.8 | 2.0±0.7 | NS | 2.0±0.6 | 1.9±0.6 | NS | ||

| Medial thigh | 2.6±1.2 | 2.3±1.0 | NS | 2.3±1.0 | 2.2±0.9 | NS | ||

| Medial knee | 1.9±0.6 | 1.8±0.5 | NS | 1.5±0.2 | 1.5±0.3 | NS | ||

| Pad under knee | 0.86±0.4 | 0.8±0.4 | NS | 1.0±0.7 | 0.8±0.3 | NS | ||

| Posterior calf | 1.5±0.3 | 1.4±0.3 | NS | 1.4±0.2 | 1.4±0.5 | NS | ||

| Location | Control (n=24) | Treatment (n=22) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 2 | Visit 3 | P-value* | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | P-value* | |

| Right Leg | ||||||

| Tender | 4.7±2.2 | 3.7±1.9 | NS | 4.6±2.2 | 2.5±1.7 | 0.0003 |

| Ache throb | 4.1±2.3 | 2.9±2.4 | NS | 4.5±2.4 | 1.3±1.8 | <0.0001 |

| Burn Sting | 2.2±2.4 | 1.7±1.9 | NS | 2.6±2.4 | 0.59±1.3 | 0.0016 |

| Tired Heavy | 5.0±2.3 | 4.0±2.5 | NS | 5.5±2.5 | 1.9±1.9 | <0.0001 |

| Swelling Tightness | 4.8±2.5 | 3.7±2.4 | 0.0377 | 4.5±2.6 | 1.5±1.5 | 0.0005 |

| Difficulty Walking | 2.5±2.9 | 1.8±2.0 | NS | 4.1±2.8 | 0.7±1.3 | <0.0001 |

| Easy bruising | 5.9±2.89 | 5.0±2.5 | NS | 5.9±3.0 | 3.3±3.2 | 0.0016 |

| Left Leg | ||||||

| Tender | 4.7±2.2 | 3.7±1.9 | NS | 5.0±2.0 | 2.5±1.7 | <0.0001 |

| Ache throb | 4.1±2.3 | 2.9±2.4 | NS | 4.8±2.2 | 1.3±1.8 | <0.0001 |

| Burn Sting | 2.2±2.4 | 1.7±1.9 | NS | 2.6±2.4 | 0.59±1.3 | 0.0008 |

| Tired Heavy | 5.0±2.3 | 4.0±2.5 | NS | 5.6±2.4 | 1.9±1.9 | <0.0001 |

| Swelling Tightness | 4.8±2.5 | 3.7±2.4 | NS | 5.1±2.6 | 1.4±1.6 | <0.0001 |

| Difficulty Walking | 2.5±2.9 | 1.8±2.0 | NS | 4.2±2.8 | 0.73±1.3 | <0.0001 |

| Easy Bruising | 5.9±2.9 | 5.0±2.5 | NS | 5.9±3.0 | 3.3±3.2 | 0.0011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).