Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

DES Preparation

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

Thermal Properties

Density and Viscosity Measurements

Extraction and Stripping of LA

Lactic Acid Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

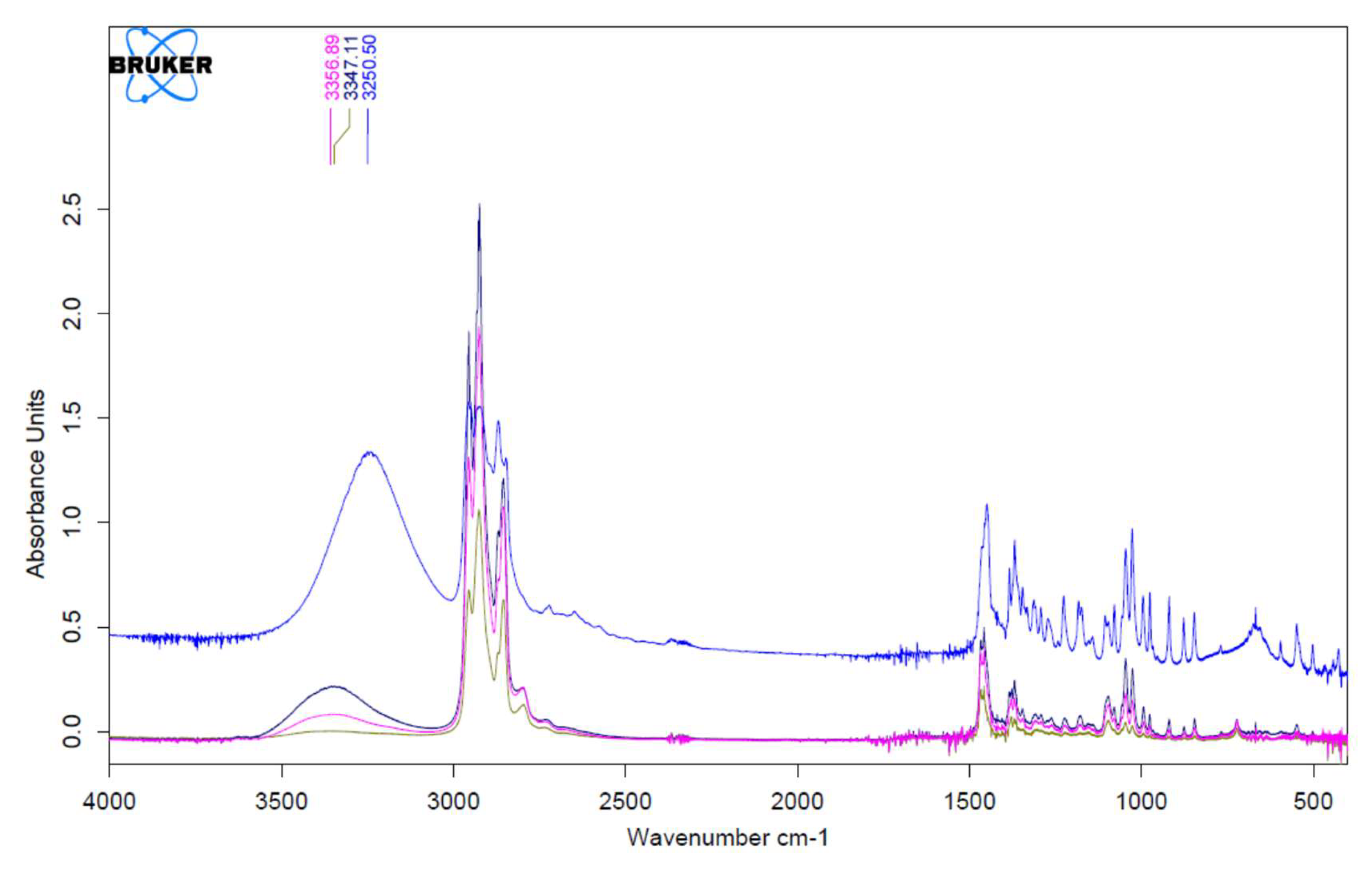

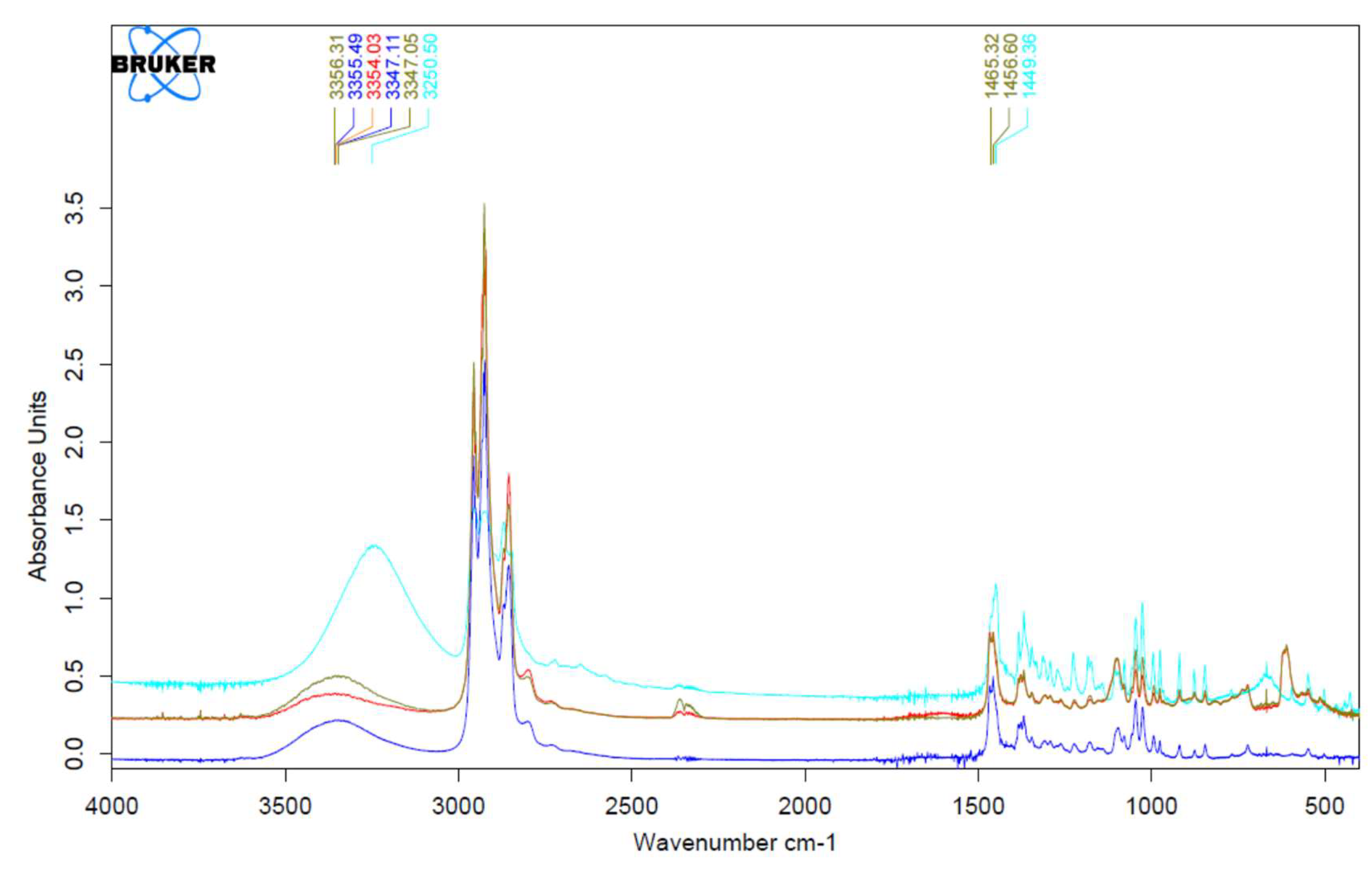

3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrophotometry (FTIR)

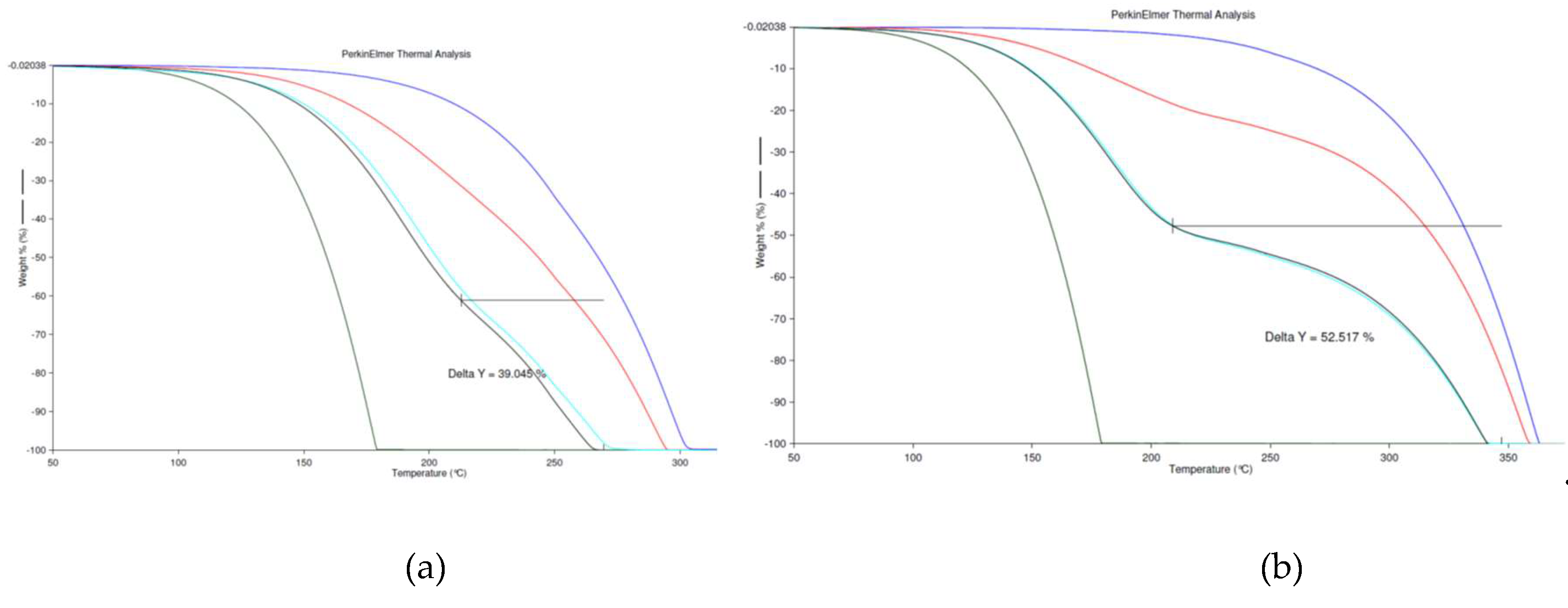

3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

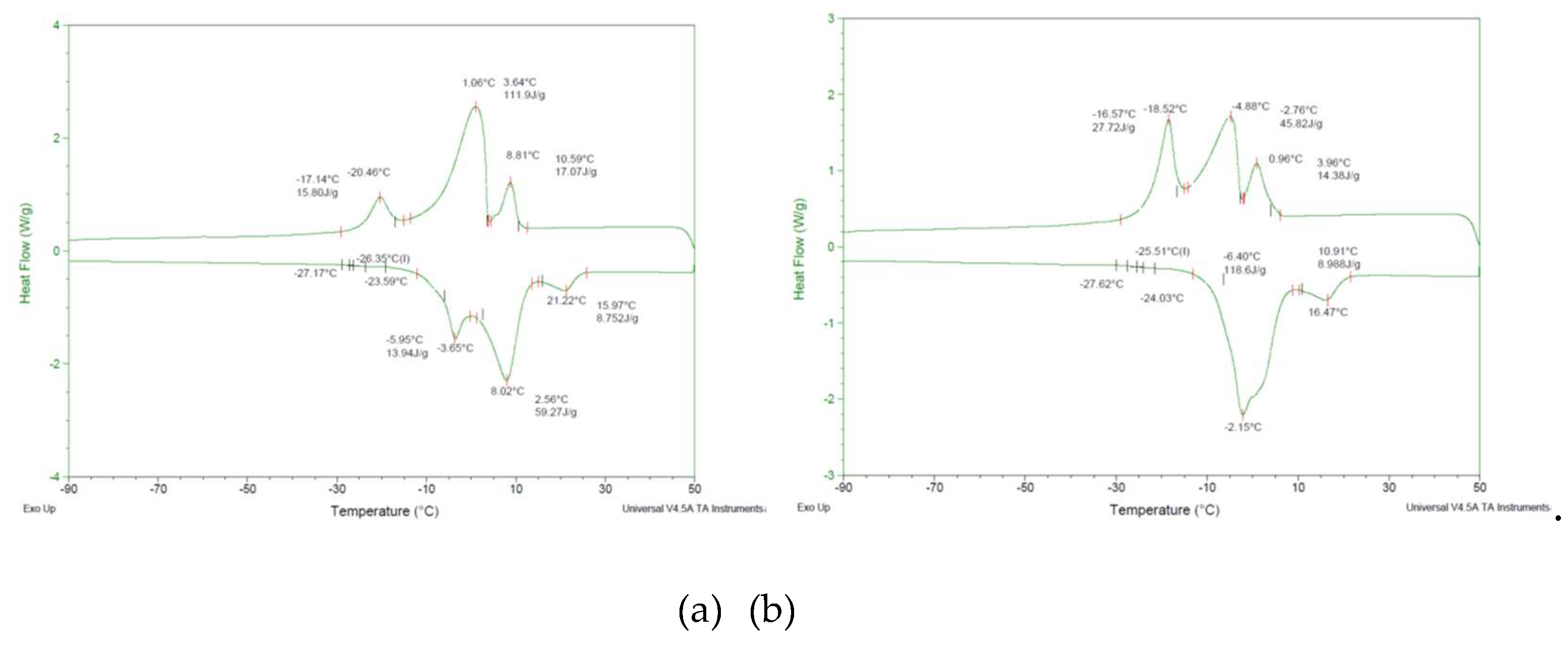

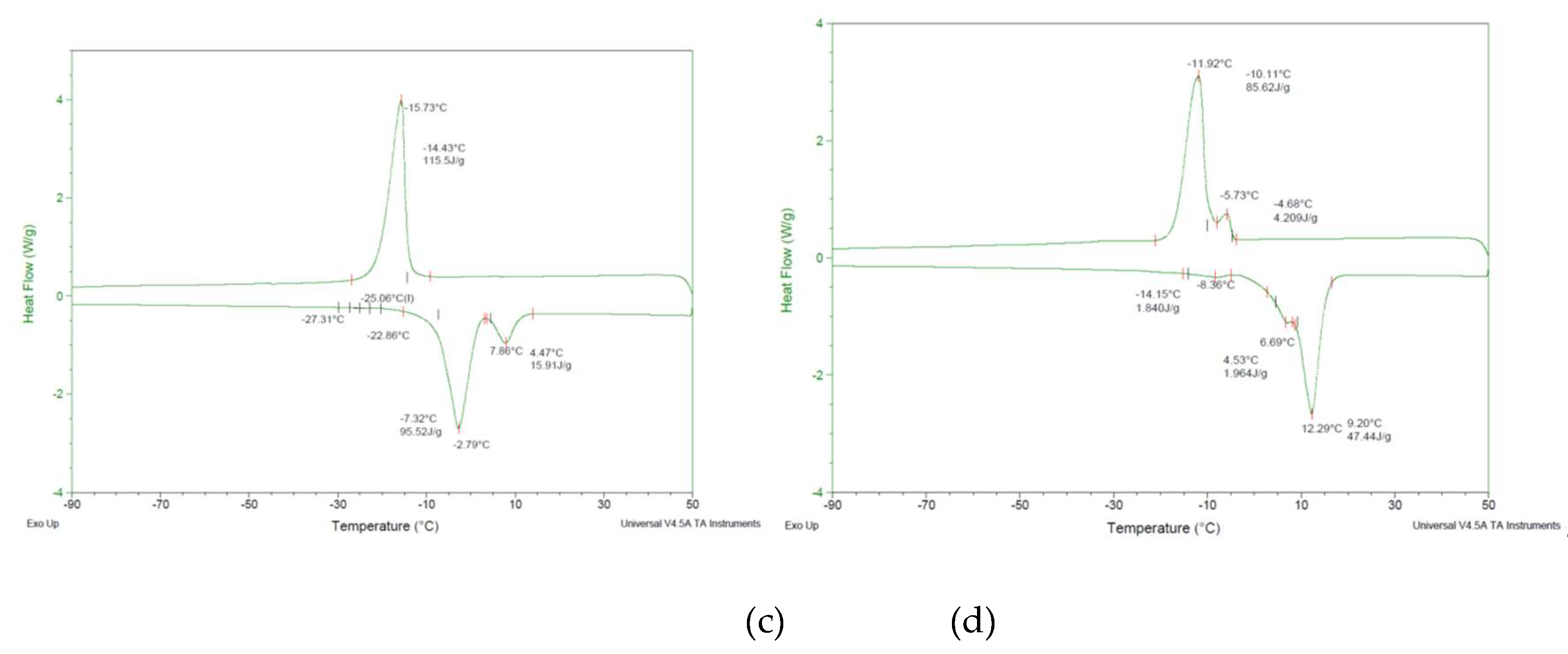

3.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

3.4. Density and Viscosity Measurements

3.5. Extraction and Stripping of Lactic Acid

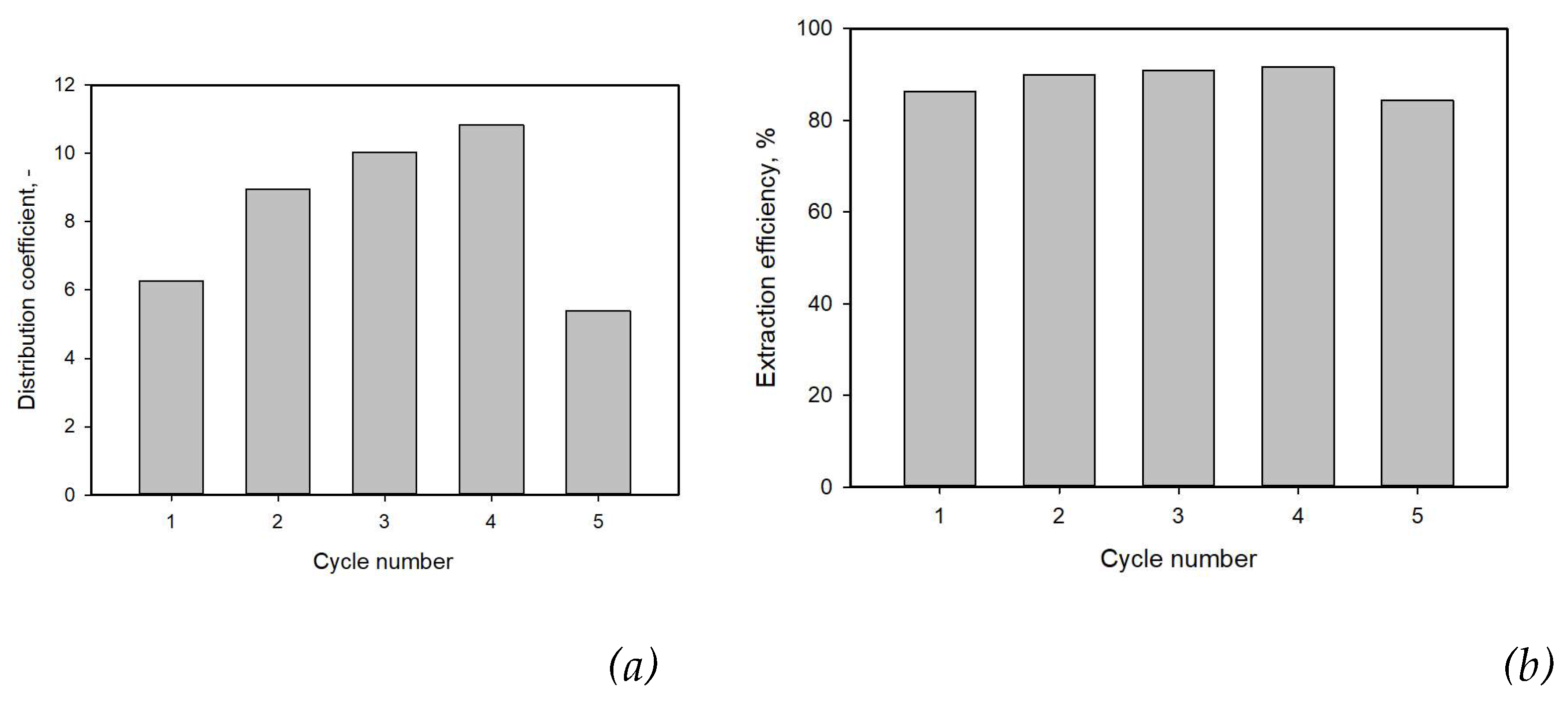

3.5. Consecutive Extraction of Lactic Acid with M:DOA 1:2 DES

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- P. von Frieling, K. Schuegerl Recovery of Lactic Acid from Aqueous Model Solutions and Fermentation Broths. Process Biochemistry 34, 685–696. [CrossRef]

- Alexandri, M.; Schneider, R.; Venus, J. Membrane Technologies for Lactic Acid Separation from Fermentation Broths Derived from Renewable Resources. Membranes 2018, 8, 94. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.D.; Lee, M.Y.; Hwang, Y.S.; Cho, Y.H.; Kim, H.W.; Park, H.B. Separation and Purification of Lactic Acid from Fermentation Broth Using Membrane-Integrated Separation Processes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 8301–8310. [CrossRef]

- Din, N.A.S.; Lim, S.J.; Maskat, M.Y.; Mutalib, S.A.; Zaini, N.A.M. Lactic Acid Separation and Recovery from Fermentation Broth by Ion-Exchange Resin: A Review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 31. [CrossRef]

- Tönjes, S.; Uitterhaegen, E.; De Winter, K.; Soetaert, W. Reactive Extraction Technologies for Organic Acids in Industrial Fermentation Processes – A Review. Separation and Purification Technology 2025, 356, 129881. [CrossRef]

- Beg, D.; Kumar, A.; Shende, D.; Wasewar, K. Liquid-Liquid Extraction of Lactic Acid Using Non-Toxic Solvents. Chemical Data Collections 2022, 38, 100823. [CrossRef]

- Teke, G.M.; Gakingo, G.K.; Pott, R.W.M. The Liquid-Liquid Extractive Fermentation of L–Lactic Acid in a Novel Semi-Partition Bioreactor (SPB). Journal of Biotechnology 2022, 360, 55–61. [CrossRef]

- Zinov’eva, I.V.; Zakhodyaeva, Yu.A.; Voshkin, A.A. Extraction of Lactic Acid Using the Polyethylene Glycol–Sodium Sulfate–Water System. Theor Found Chem Eng 2021, 55, 101–106. [CrossRef]

- Kyuchoukov, G.; Yankov, D. Lactic Acid Extraction by Means of Long Chain Tertiary Amines: A Comparative Theoretical and Experimental Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 9117–9122. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Thakur, A. Reactive Extraction of Lactic Acid Using Environmentally Benign Green Solvents and Synergistic Mixture of Extractants. Scientia Iranica 2019, 0, 0–0. [CrossRef]

- Bayazit, Ş.S.; Uslu, H.; İnci, İ. Comparison of the Efficiencies of Amine Extractants on Lactic Acid with Different Organic Solvents. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2011, 56, 750–756. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Munro, H.L.; Rasheed, R.K.; Tambyrajah, V. Preparation of Novel, Moisture-Stable, Lewis-Acidic Ionic Liquids Containing Quaternary Ammonium Salts with Functional Side Chains. Chem. Commun. 2001, 2010–2011. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Rasheed, R.K.; Tambyrajah, V. Novel Solvent Properties of Choline Chloride/Urea mixturesElectronic Supplementary Information (ESI) Available: Spectroscopic Data. See Http://Www.Rsc.Org/Suppdata/Cc/B2/B210714g/. Chem. Commun. 2003, 70–71. [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.A.R.; Pinho, S.P.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Insights into the Nature of Eutectic and Deep Eutectic Mixtures. J Solution Chem 2019, 48, 962–982. [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.L.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) and Their Applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [CrossRef]

- Zainal-Abidin, M.H.; Hayyan, M.; Hayyan, A.; Jayakumar, N.S. New Horizons in the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds Using Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review. Analytica Chimica Acta 2017, 979, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Guo, X.; Xu, T.; Fan, L.; Zhou, X.; Wu, S. Ionic Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Extraction and Separation of Natural Products. Journal of Chromatography A 2019, 1598, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Kalyniukova, A.; Holuša, J.; Musiolek, D.; Sedlakova-Kadukova, J.; Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Andruch, V. Application of Deep Eutectic Solvents for Separation and Determination of Bioactive Compounds in Medicinal Plants. Industrial Crops and Products 2021, 172, 114047. [CrossRef]

- Ruesgas-Ramón, M.; Figueroa-Espinoza, M.C.; Durand, E. Application of Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) for Phenolic Compounds Extraction: Overview, Challenges, and Opportunities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 3591–3601. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Witkamp, G.-J.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as a New Extraction Media for Phenolic Metabolites in Carthamus Tinctorius L. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 6272–6278. [CrossRef]

- Fanali, C.; Gallo, V.; Della Posta, S.; Dugo, L.; Mazzeo, L.; Cocchi, M.; Piemonte, V.; De Gara, L. Choline Chloride–Lactic Acid-Based NADES As an Extraction Medium in a Response Surface Methodology-Optimized Method for the Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Hazelnut Skin. Molecules 2021, 26, 2652. [CrossRef]

- Şen, F.B.; Nemli, E.; Bekdeşer, B.; Çelik, S.E.; Lalikoglu, M.; Aşçı, Y.S.; Capanoglu, E.; Bener, M.; Apak, R. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Valuable Phenolics from Sunflower Pomace with Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents and Food Applications of the Extracts. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Görüşük, E.M.; Lalikoglu, M.; Aşçı, Y.S.; Bener, M.; Bekdeşer, B.; Apak, R. Novel Tributyl Phosphate-Based Deep Eutectic Solvent: Application in Microwave Assisted Extraction of Carotenoids. Food Chemistry 2024, 459, 140418. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Cheng, H.; Song, Z.; Ji, L.; Chen, L.; Qi, Z. Selection of Deep Eutectic Solvents for Extractive Deterpenation of Lemon Essential Oil. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2022, 350, 118524. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, B.; Li, D. Ultrasound-Assisted Deep Eutectic Solvents Extraction of Podophyllotoxins from Juniperus Sabina L: Optimization, Enrichment, and Anti-Drug Resistant Bacteria Activity. Industrial Crops and Products 2024, 221, 119408. [CrossRef]

- Cañadas, R.; González-Miquel, M.; González, E.J.; Díaz, I.; Rodríguez, M. Hydrophobic Eutectic Solvents for Extraction of Natural Phenolic Antioxidants from Winery Wastewater. Separation and Purification Technology 2021, 254, 117590. [CrossRef]

- Lalikoglu, M. Intensification of Formic Acid from Dilute Aqueous Solutions Using Menthol Based Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents. Journal of the Indian Chemical Society 2022, 99, 100303. [CrossRef]

- Şahin, S.; Kurtulbaş, E. An Advanced Approach for the Recovery of Acetic Acid from Its Aqueous Media: Deep Eutectic Liquids versus Ionic Liquids. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2022, 12, 341–349. [CrossRef]

- Baş, Y.; Lalikoglu, M.; Uthan, A.; Kordon, E.; Anur, A.; Aşçı, Y.S. Realization for Rapid Extraction of Citric Acid from Aqueous Solutions Using Deep Eutectic Solvents. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2024, 411, 125699. [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Zamora, C.; González-Sálamo, J.; Hernández-Sánchez, C.; Hernández-Borges, J. Menthol-Based Deep Eutectic Solvent Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction: A Simple and Quick Approach for the Analysis of Phthalic Acid Esters from Water and Beverage Samples. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 8783–8794. [CrossRef]

- Demmelmayer, P.; Steiner, L.; Weber, H.; Kienberger, M. Thymol-Menthol-Based Deep Eutectic Solvent as a Modifier in Reactive Liquid–Liquid Extraction of Carboxylic Acids from Pretreated Sweet Sorghum Silage Press Juice. Separation and Purification Technology 2023, 310, 123060. [CrossRef]

- Demmelmayer, P.; Foo, J.W.; Wiesler, D.; Rudelstorfer, G.; Kienberger, M. Reactive Liquid-Liquid Extraction of Lactic Acid from Microfiltered Sweet Sorghum Silage Press Juice in an Agitated Extraction Column Using a Hydrophobic Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent as Modifier. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 458, 142463. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, K.; Datta, D. Recovery of Nicotinic Acid (Niacin) Using Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvent: Ultrasonication Facilitated Extraction. Chemical Data Collections 2022, 41, 100934. [CrossRef]

- Mulia, Ph.D, K.; Adam, D.; Zahrina, I.; Krisanti, Ph.D, E. Green Extraction of Palmitic Acid from Palm Oil Using Betaine-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. IJTech 2018, 9, 335. [CrossRef]

- Mulia, K.; Masanari, E.; Zahrina, I.; Susanto, B.; Krisanti, E.A. Optimization of Palmitic Acid Extraction from Palm Oil with Betaine-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent Using Response Surface Methodology.; Tangerang, Indonesia, 2019; p. 020041.

- Liu, L.; Fang, H.; Wei, Q.; Ren, X. Extraction Performance Evaluation of Amide-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents for Carboxylic Acid: Molecular Dynamics Simulations and a Mini-Pilot Study. Separation and Purification Technology 2023, 304, 122360. [CrossRef]

- Riveiro, E.; González, B.; Domínguez, Á. Extraction of Adipic, Levulinic and Succinic Acids from Water Using TOPO-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. Separation and Purification Technology 2020, 241, 116692. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Ma, W.; Zhao, J.; Yu, J.; Wei, Q.; Ren, X. In-Situ Formation of Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents to Separate Lactic Acid: Lactam as Hydrogen Bond Acceptor and Lactic Acid as Hydrogen Bond Donor. Separation and Purification Technology 2025, 353, 128511. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Han, X.; Huang, X.; Zhao, J.; Ren, Q.; Luo, H. Menthol-Based Eutectic Mixtures: Novel Potential Temporary Consolidants for Archaeological Excavation Applications. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2019, 39, 103–109. [CrossRef]

- Ohno, K.; Shimoaka, T.; Akai, N.; Katsumoto, Y. Relationship between the Broad OH Stretching Band of Methanol and Hydrogen-Bonding Patterns in the Liquid Phase. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 7342–7348. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Trindle, C.; Knee, J.L. Communication: Frequency Shifts of an Intramolecular Hydrogen Bond as a Measure of Intermolecular Hydrogen Bond Strengths. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2012, 137, 091101. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, B.D.; Florindo, C.; Iff, L.C.; Coelho, M.A.Z.; Marrucho, I.M. Menthol-Based Eutectic Mixtures: Hydrophobic Low Viscosity Solvents. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 2469–2477. [CrossRef]

- Aroso, I.M.; Craveiro, R.; Rocha, Â.; Dionísio, M.; Barreiros, S.; Reis, R.L.; Paiva, A.; Duarte, A.R.C. Design of Controlled Release Systems for THEDES—Therapeutic Deep Eutectic Solvents, Using Supercritical Fluid Technology. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2015, 492, 73–79. [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Banerjee, T. Liquid–Liquid Extraction of Lower Alcohols Using Menthol-Based Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvent: Experiments and COSMO-SAC Predictions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 3371–3381. [CrossRef]

- Chemical BooK, Dioctylamine (1120-48-5) Available online: https://www.chemicalbook.com/ProductMSDSDetailCB7389427_EN.htm (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Chemical BooK, Tridodecylamine (102-87-4) Available online: https://www.chemicalbook.com/ChemicalProductProperty_US_CB5727311.aspx (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Yamashita, H.; Hirakura, Y.; Yuda, M.; Terada, K. Coformer Screening Using Thermal Analysis Based on Binary Phase Diagrams. Pharm Res 2014, 31, 1946–1957. [CrossRef]

- Toprakçı, İ.; Pekel, A.G.; Kurtulbaş, E.; Şahin, S. Special Designed Menthol-Based Deep Eutectic Liquid for the Removal of Herbicide 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid through Reactive Liquid–Liquid Extraction. Chem. Pap. 2020, 74, 3995–4002. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Su, B.; Wei, Q.; Ren, X. Selective Separation of Lactic, Malic, and Tartaric Acids Based on the Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents of Terpenes and Amides. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 5866–5874. [CrossRef]

- Van Osch, D.J.G.P.; Zubeir, L.F.; Van Den Bruinhorst, A.; Rocha, M.A.A.; Kroon, M.C. Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents as Water-Immiscible Extractants. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 4518–4521. [CrossRef]

- Aşçı, Y.S.; Lalikoglu, M. Development of New Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents Based on Trioctylphosphine Oxide for Reactive Extraction of Carboxylic Acids. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 1356–1365. [CrossRef]

| Name | Abbreviation | Supplier | Purity |

|---|---|---|---|

| L (+) Lactic acid | LA | Acros Organics | ≥ 90% |

| Crystalline L- (+) Lactic acid | LA | Thermo Scientific | ≥ 98% |

| L- Menthol | M | Sigma-Aldrich | ≥ 99% |

| Dioctyl amine | DOA | Fluka | ≥ 97% |

| Trihexyl amine | THA | Jenssen Chemica | ≥ 95% |

| Trioctyl amine | TOA | Thermo Scientific | ≥ 95% |

| Tridodecyl amine | TDDA | Merck | ≥ 95% |

| Mixture components | Molar ratio |

|---|---|

| M/DOA | 1:1, 1:2, 2:1 |

| M/TOA | 1:1, 1:2, 2:1 |

| M/THA | 1:1, 1:2, 2:1 |

| M/TDDA | 1:1, 1:2, 2:1 |

| Pure compound | ToC | DES | Tdeg (oC) | First step decomposition degree (%) |

| L-Menthol | 175 | M/DOA 1:1 | 280 | - |

| DOA | 305 | M/DOA 1:2 | 290 | - |

| TOA | 365 | M/TOA 1:2 | 360 | 26,5 % |

| THA | 465 | M/THA 1/1 | 275 | - |

| TDDA | 470 | M/THA 1:2 | 290 | - |

| M/TDDA 1/1 | 460 | 30 % | ||

| M/TDDA 1:2 | 460 | 18 % |

| Eutectic mixtures (ratio) | First step Tdeg (oC) | Decomposition degree (%) | Second step Tdeg (oC) | Decomposition degree (%) |

| M/DOA 1:2 ex | - | - | 275 | 100 |

| M/DOA 1:2 re-ex | - | - | 275 | 100 |

| M/TOA 1/1 ex | 220 | 50 | 340 | 50 |

| M/TOA 1/1 re-ex | 220 | 50 | 340 | 50 |

| M/THA 1/1 ex | - | - | 275 | 100 |

| M/THA 1/1 re-ex | - | - | 275 | 100 |

| M/TDDA 1:2 ex | 230 | 41 | 450 | 59 |

| DES | Ratio | First stripping, % | First & Second stripping, % |

| M:DOA | 2:1 | 95 | 97 |

| M:THA | 1:2 | 86 | 86 |

| M:THA | 2:1 | 94 | 95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).