Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Preamble

[…] On a fort peu étudié jusqu’ici les changements de température survenus dans les corps par l’effet du mouvement; cette classe de phénomènes mériterait cependant l’attention des observateurs. Lorsque les corps sont en mouvement, lorsque surtout il se consomme ou qu’il se produit de la puissance motrice, il arrive des changements remarquables dans la distribution de la chaleur et peut-être dans sa quantité. Nous allons apporter un petit nombre de faits, où ce phénomène se développe avec le plus d’évidence. (Carnot 1824b, p. 195)

[…] La thermodynamique a habitué de longue date la physique mathématique [cf. DUHEM P.] à la considération de formes de Pfaff complètement intégrables : la chaleur élémentaire dQ [notation des thermodynamiciens] représentant la chaleur élémentaire cédée dans une modification infinitésimale réversible est une telle forme complètement intégrable. Ce point ne semble guère avoir été creusé depuis lors. (Reeb 1978, p. 8)

2. Jean-Marie Souriau’s Symplectic Model of Lie Groups Thermodynamics and Geometric Definition of Entropy as Casimir Function on Symplectic Foliation

[…] The consideration of the above case of statistical equilibrium may be made the foundation of the theory of the thermodynamic equilibrium of rotating bodies, a subject which has been treated by Maxwell in his memoir On Boltzmann's theorem on the average distribution of energy in a system of material points (Gibbs 1902, p.44)

[…] This book is not one of those that one analyzes hastily; but, on the other hand, the questions it deals with have been greatly agitated in recent times; the ideas defended by Gibbs have been the subject of much controversy; the reasoning with which he supported them has also been criticized. It seems interesting to me to study his work in the light of these controversies and by discussing these criticisms (Hadamard 1906, p. 194)

2.1. Souriau’s Seminal Idea of Symplectic Model of Statistical Mechanics in the Framework of Representation Theory

[…] Tuesday's class was devoted to the systematic study of the relationships between foliation and Poisson manifolds. The notion of Poisson manifold was introduced by us in 1975 as a natural contravariant generalization of that of symplectic manifold. On such a manifold, the Poisson structure determines a symplectic foliation either in a generalized sense (non-regular Poisson manifold) or in the strict sense of the term (regular Poisson manifold). A simple natural example of the first case is provided by the orbits of the coadjoint representation of a Lie algebra. A simple example of the second case is given by the fibers cotangent to the foliations. Let (M, F) be a symplectic manifold equipped with a Lagrangian foliation £. It has been shown that there always exists on M a connection adapted to foliation which induces on each leaf a flat connection without torsion. If the manifold admits a fiber-type Riemannian metric for £, it admits a Riemannian metric which induces a flat metric on each leaf. We have thus clarified and generalized recent results of A. Weinstein and P. Dazord. The same results are valid if, instead of a Lagrangian foliation, we consider an isotropic foliation of (M, F) such that the field of symplectic orthogonal planes is a coisotropic foliation. (Lichnerowicz 1983d, p.2)

[…] A characteristic trend in mathematical physics is the growing use of the same abstract formalisms for the description of very different physical phenomena. A paradigm is the Hamiltonization of various fields of physics, i.e. the use of Hamiltonian structuresand symplectic geometry, based on the mathematical language of exterior differential forms, fibre bundles, Poisson bracket structures and generally Lie algebraic conceptions. Examples are widespread. With the dliscovery of the Lie-Poisson structure underlying the Euler equations of fluid flow by Arnol’d ... Another field where Hamiltonian structures and symplectic geometry play a growing role is quantum mechanics and quantum field theory including nuclear physics. In the foreground are problems of quantization (so-called geometric quantization) by means of the Wigner-Wel formalism and the physics of semi-classical systems. A further use for Hamiltonian structures and symplectic notions is given in the fields of differential equations, optimization and control theory. Characteristic of all these theoretical developments is that the systems considered are ideal systems (fluids, plasmas, quantum systems,…) without energy dissipation (without frictions, damping,…), i.e. without entropy production. There exists a larger literature on the damping of quantized systems or, in other words, on problems of the correct formulation of a quantum theory of systems with friction. A symplectic approach to nonconservative systems- which can be considered as a first step towards a correct quantization procedure-was treated only in few papers without explicitly considering, however, the thermodynamics and, in particular, the entropy balance. On the other hand a few papers have been published on the symplectic structure of equilibrium thermodynamics, but (to the best of our knowledge) not of irreversible thermodynamics, with one important exception, i.e. a set of papers by the Ingarden group on “information geometry” and irreversible thermodynamics where indeed the connection between information theory and differential geometry plays the main role”.(Vojta 1990, p. 251)

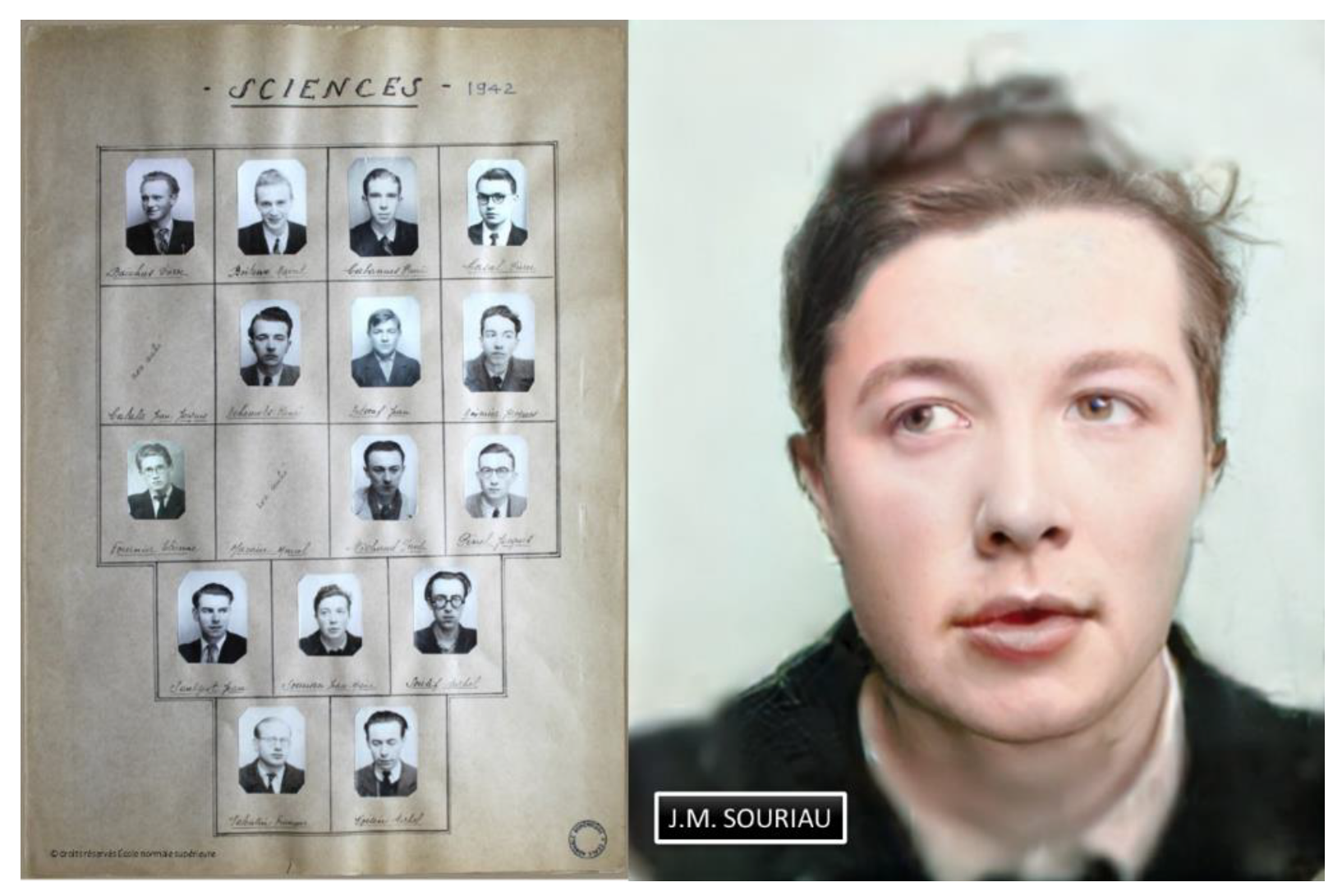

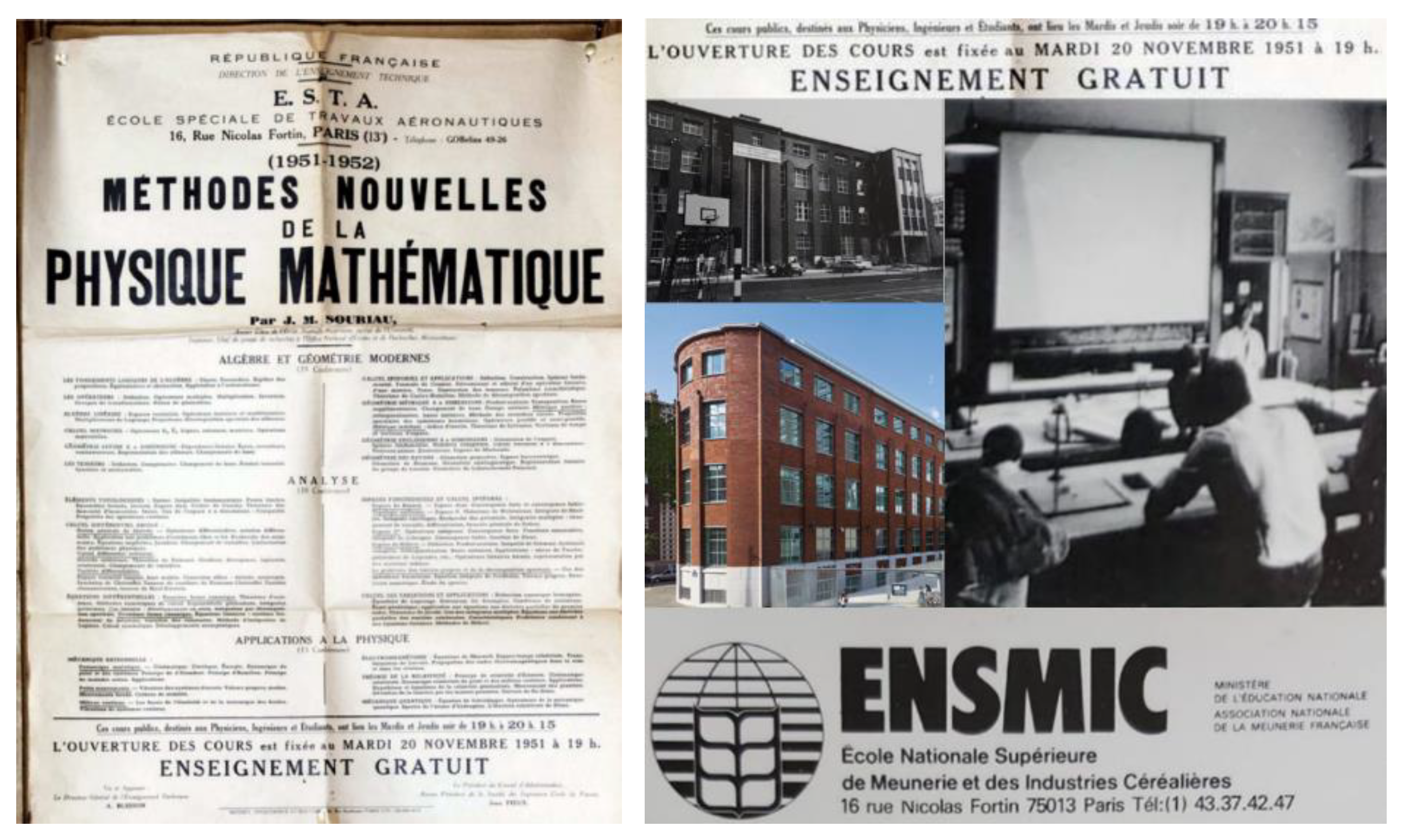

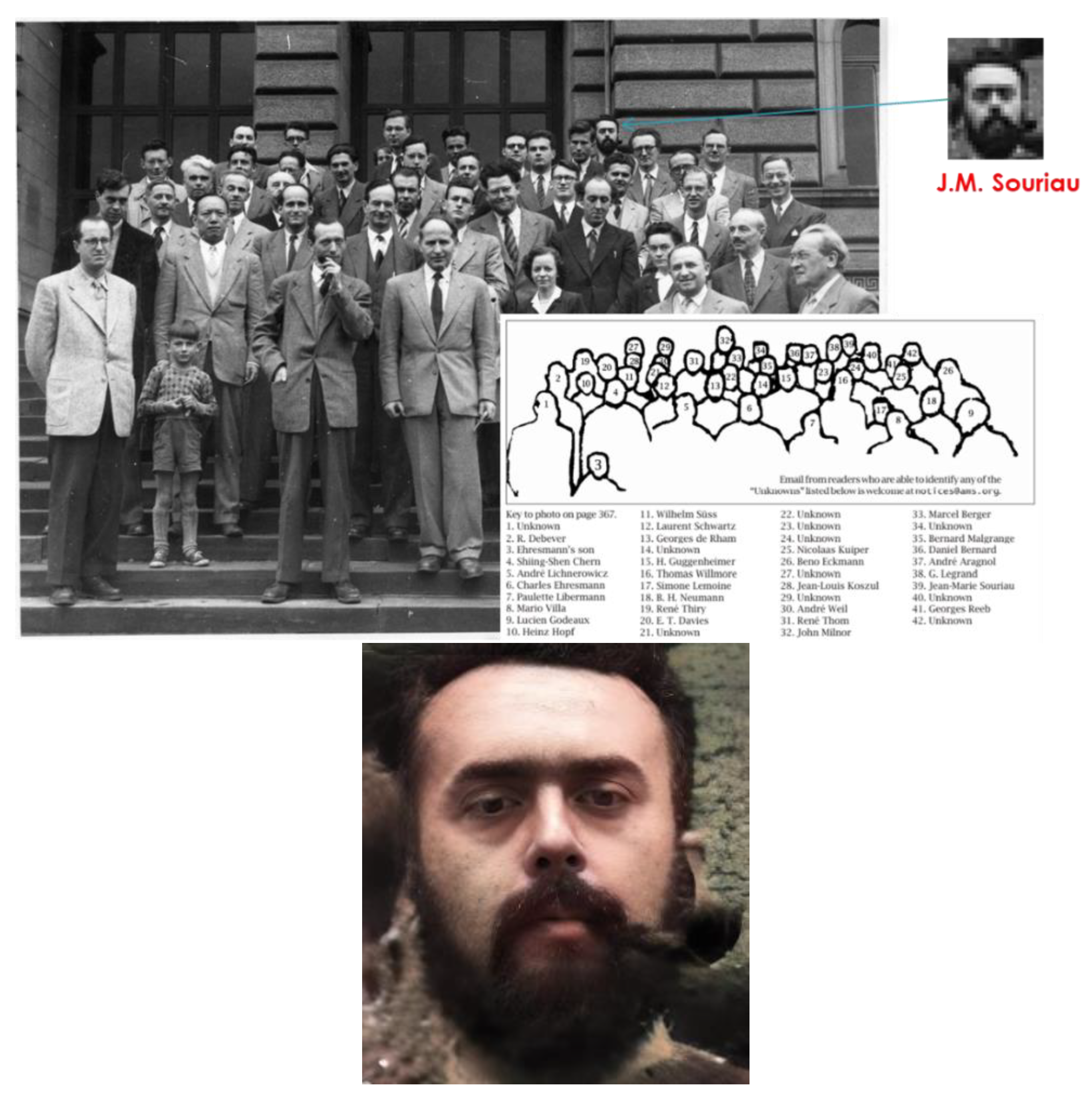

2.2. Jean-Marie Souriau Scientific Biography

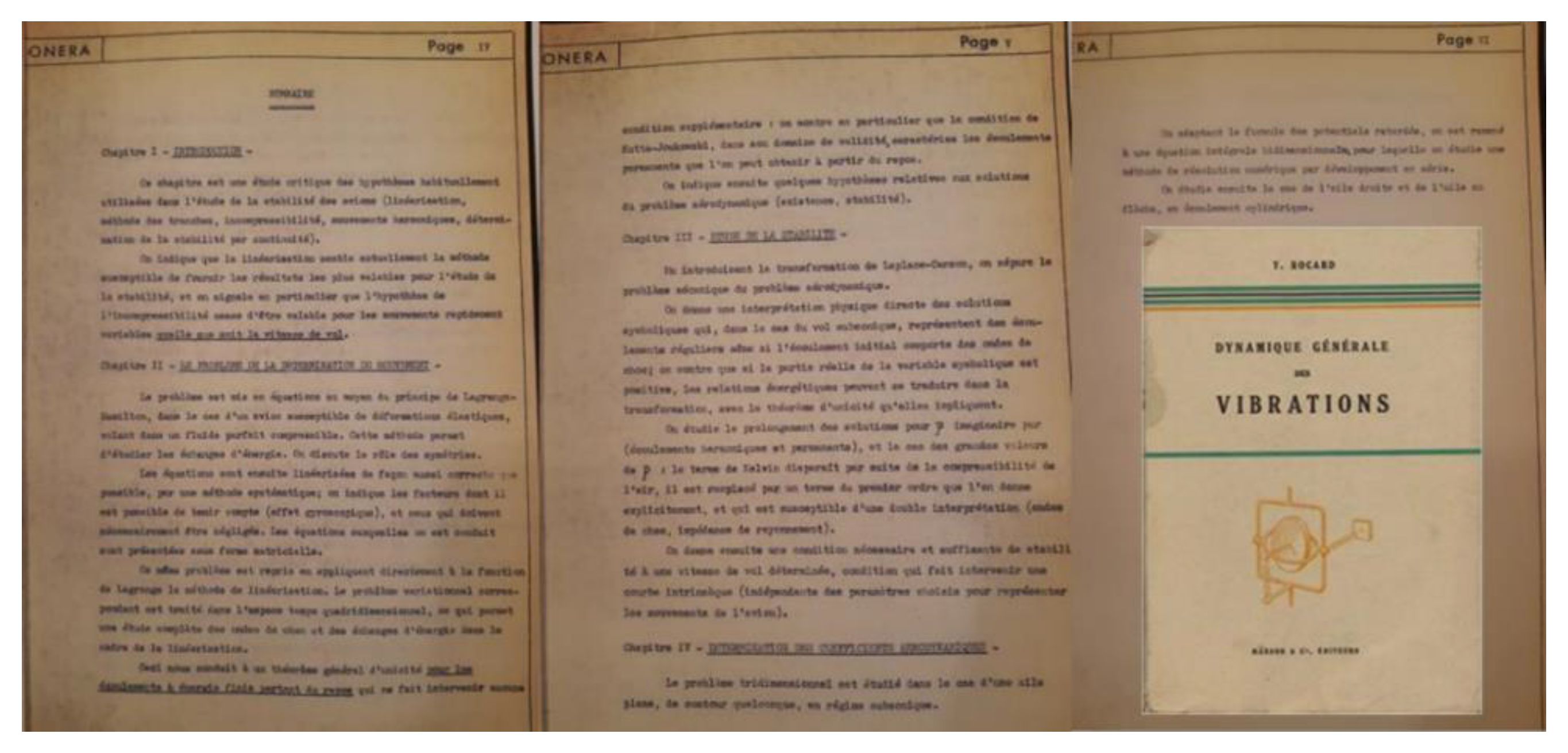

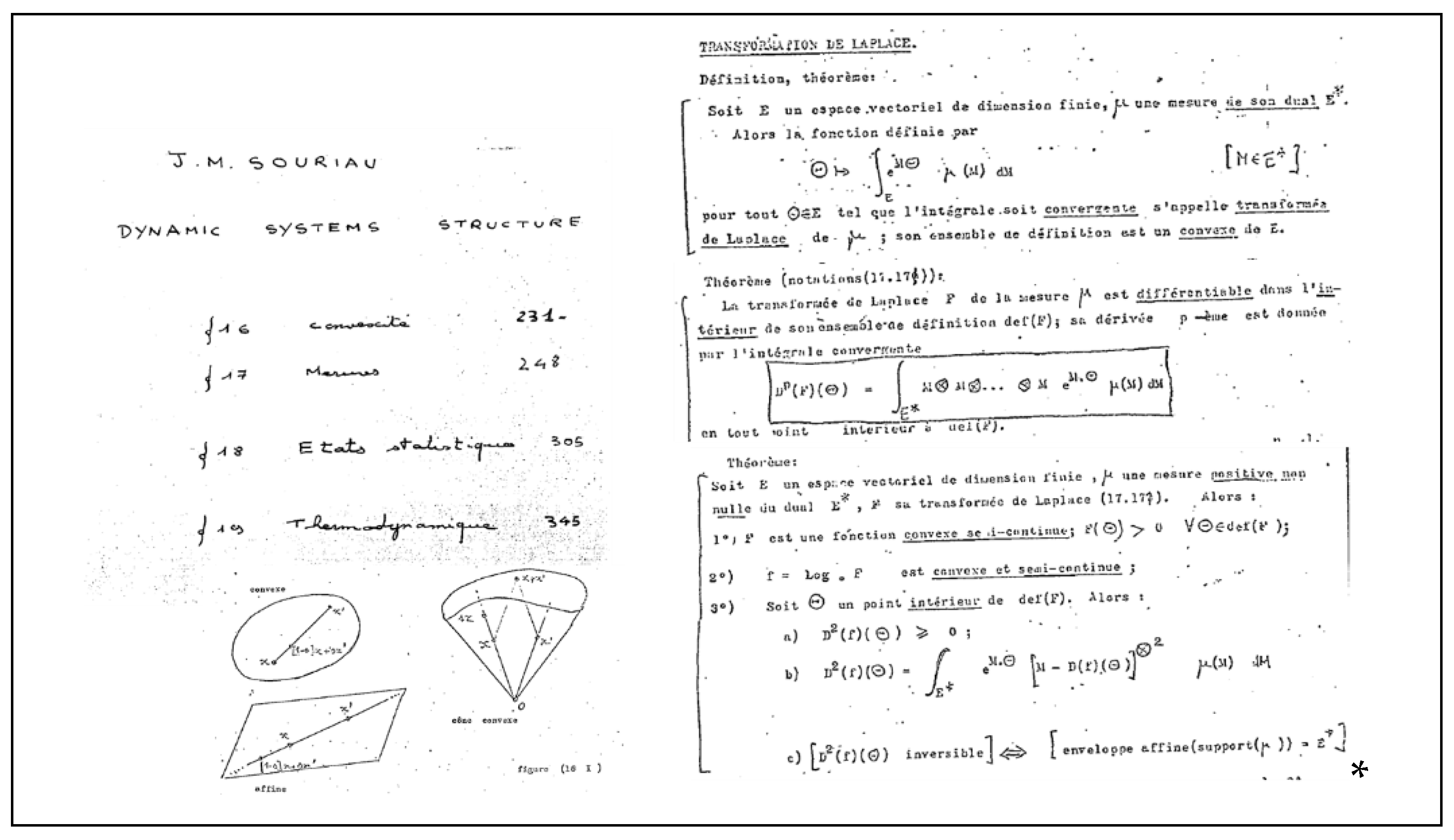

2.3. Jean-Marie Souriau elaboration of Symplectic model of Mechanics and Lie Group Thermodynamics

[…] In my first publication, there was also the word “application”. I applied this formalism to the calculation of disturbances, introducing saturated isotropic manifolds (which today we call Lagrangian manifolds) which make it possible to produce so many symplectomorphisms , while there are so few “riemannomorphisms”. Earlier I was talking about determinants which appear miraculously when we try to invert a matrix. For symplectic geometry it's a bit the same thing. You try to resolve the disturbances of a system and you see the coefficients of the symplectic structure appear . You want to solve a problem, you solve it by hand, you work, and when you have worked well, you see something appear that was hidden underneath. And what Lagrange saw, which Laplace did not see, was the symplectic structure. Finally, if you look closely at the progression of mathematics, you realize that it is very often like that. It's usage that tells you if it's important , and then you axiomatize things. But that comes after the fact. What makes symplectic geometry important is that it is self-imposed . I am not a Platonist, I am not saying that mathematical ideas are ready-made and that we only have to discover them. We discover physics. Symplectic geometry was discovered as a tool for celestial mechanics. Starting from a general theory of differential equations, we would probably never have found it. The particular model of the equations of celestial mechanics was richer than the model of “general” differential equations…. What makes the theory global, and therefore geometric, is the action of groups of symplectomorphisms. Think of the theorem of Noether, a mathematician at the origin of an important part of modern algebra, but who also discovered this theorem which teaches us that the symmetries of a system lead to conserved quantities. It hides (or reveals) the relationships between group and symplectic. I implemented something that I thought was new, but which had existed since Sophus Lie, a geometrization of Noether's theorem . I called it “moment map”. The initial variational formulation has exceptions which disappear with the symplectic formulation. (Souriau 1995, p. 164)

[…] In 1958, I returned to France, to Marseille. And there I found myself confronted with theoretical physicists and the problems of quantum mechanics which had disturbed me during my studies like all students, I think. I realized that symplectic geometry was an essential tool for quantum mechanics . And that in fact it was even more appropriate for quantum mechanics than it was for classical mechanics . When I wrote my book on the subject I wanted to write a book on quantum mechanics and I realized that I had to present all classical mechanics in detail, as well as statistical mechanics . These were not foreign theories since they were linked by symplectic structure and symmetries. You take two particles which revolve around each other following Newton's laws, and then you take a hydrogen atom of which you only see the spectrum. These are two objects which a priori have nothing to do with each other; but they have symplectic symmetries in common. A door is ajar . (Souriau 1995, p. 165)

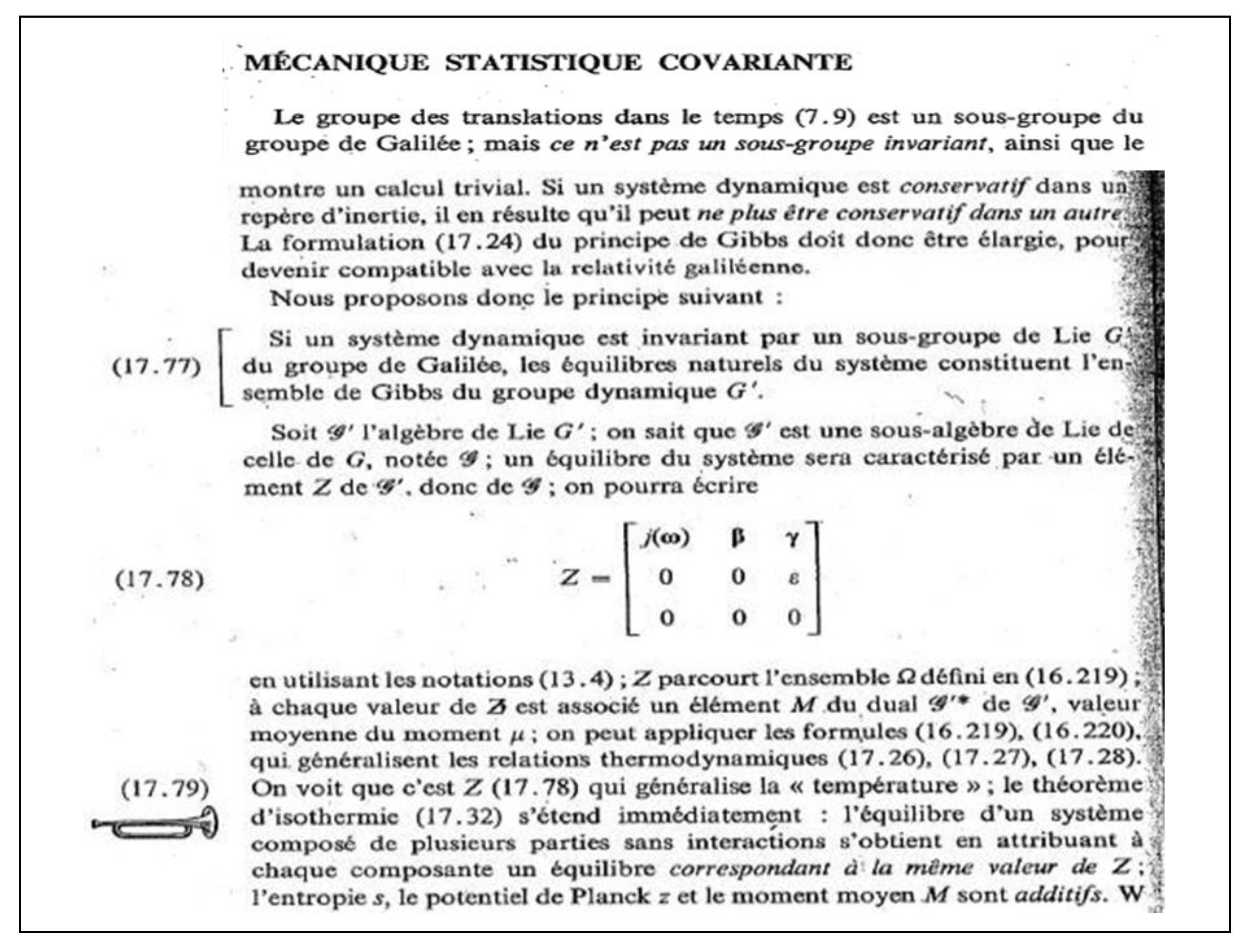

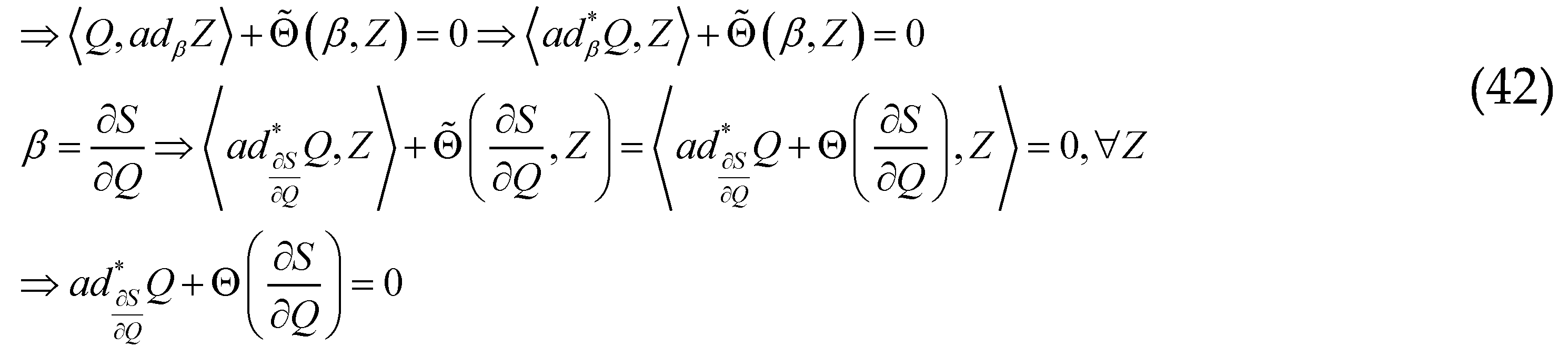

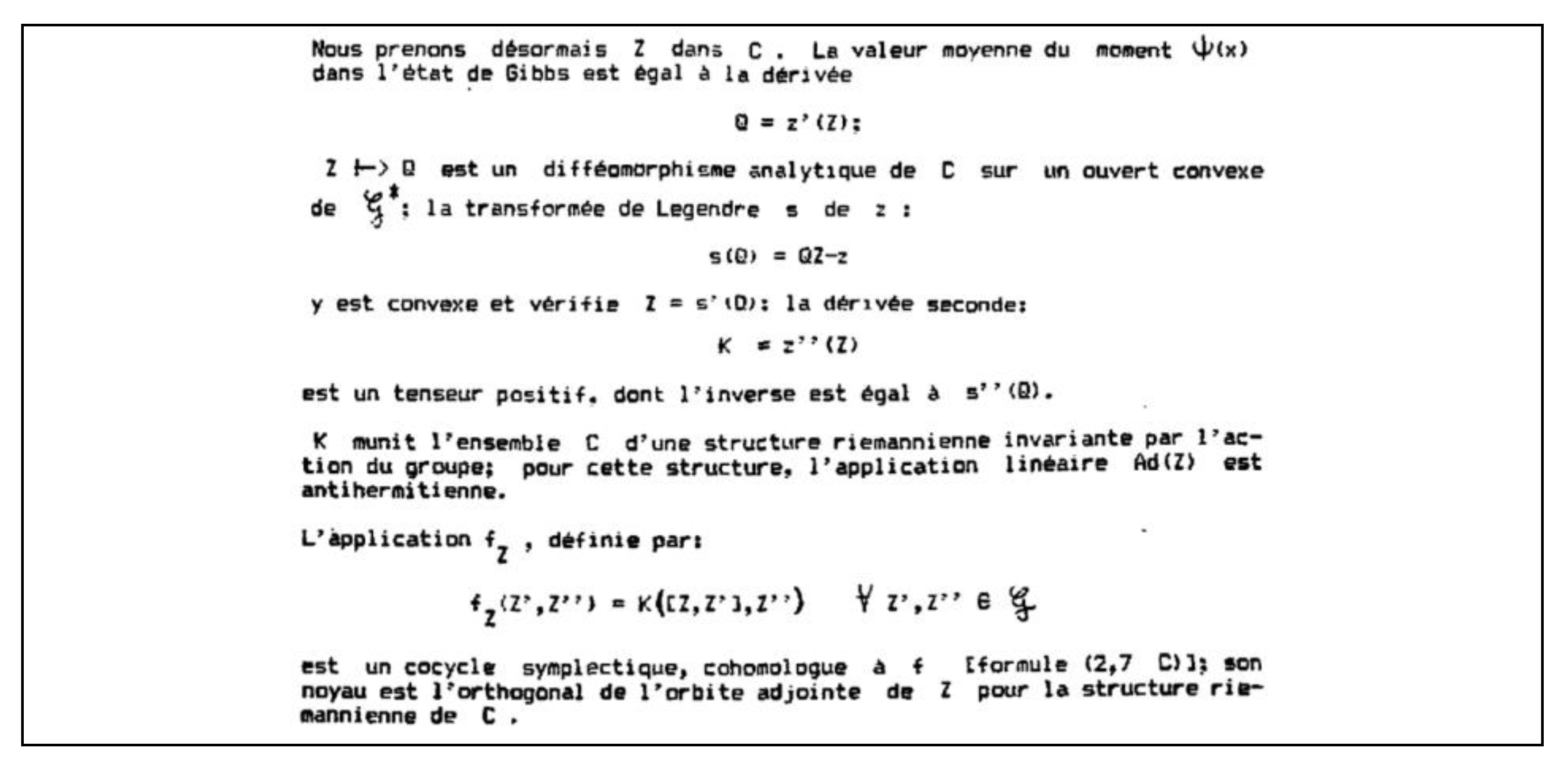

2.4. Souriau’s Lie Group Thermodynamics as Symplectic Model of Statstical Mechanics

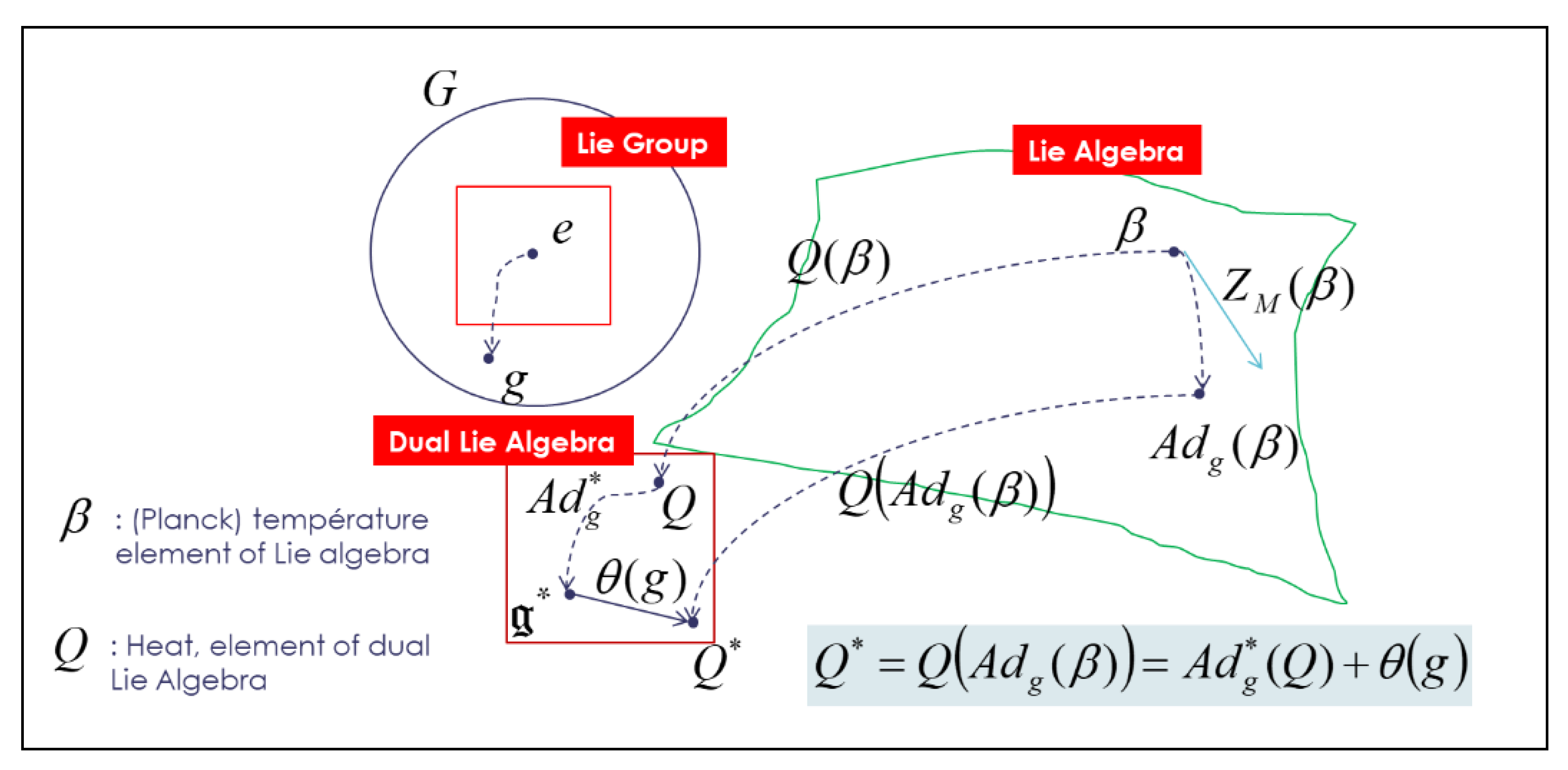

- Lie and dual Lie algebras:

- Coadjoint operator:

- Moment map:

- Souriau 1-cocycle:

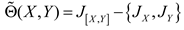

- Souriau 2-cocycle:

- Affine coadjoint operator:

- Poisson Bracket given by KKS 2-form

- Affine Poisson bracket:

- Foliation : A foliation can be thought of as a structure where one "cuts" the manifold into a set of smooth leaves (submanifolds), and the overall structure of the foliation can be very different from simply cutting the manifold into disjoint pieces. The leaves can "bend" or "twist" across the manifold in a regular way. The concept of foliation is particularly used in geometric, topological, and analytical studies, and appears in many areas, including dynamics, geometry of manifolds, and physics (e.g., in models of dynamical systems or phase structures).

- Lie algebra cohomology: Lie algebra cohomology can be seen through a geometric interpretation. For example, in differential geometry, Lie algebra cohomology appears in the study of local symmetries of a manifold, connection structures on bundles, and complexes of differential forms associated with Lie algebras. Lie algebra cohomology is a way to measure the obstructions to the possibility of "deforming" a structure given by a Lie algebra. It allows to study properties of Lie algebras, such as representations and internal structure, in a very general and abstract way. We will use the default of cohomology, where a cocycle appears when coadjoint operator is not equivariant.

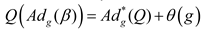

(this cocycle appears due to the non-equivariance of the coadjoint operator

(this cocycle appears due to the non-equivariance of the coadjoint operator  action of the group on the dual space of the Lie algebra, which is modified with a cocycle).

action of the group on the dual space of the Lie algebra, which is modified with a cocycle). . In the following we will use the notation with such as Koszul and Souriau use it.

. In the following we will use the notation with such as Koszul and Souriau use it.  is called a Souriau cocycle, and it is a measure of the lack of equivariance.

is called a Souriau cocycle, and it is a measure of the lack of equivariance.

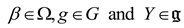

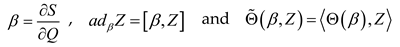

of the Lie algebra, the operator is given by the adjoint operator

of the Lie algebra, the operator is given by the adjoint operator  . With respect to the group action

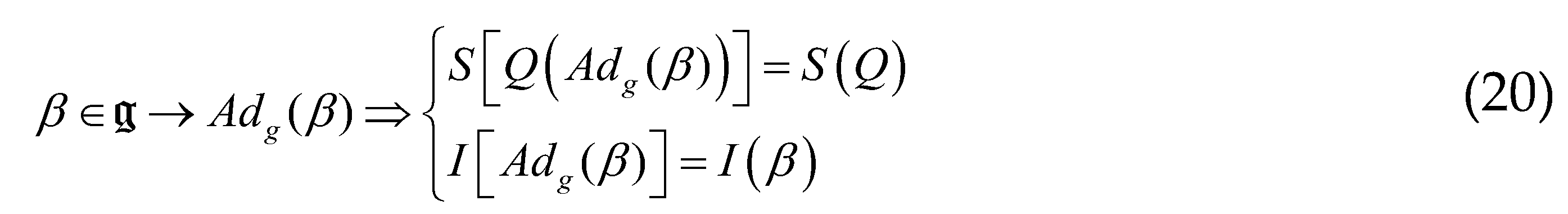

. With respect to the group action  , Entropy

, Entropy  and Fisher's metric

and Fisher's metric  are invariant:

are invariant:

:

:

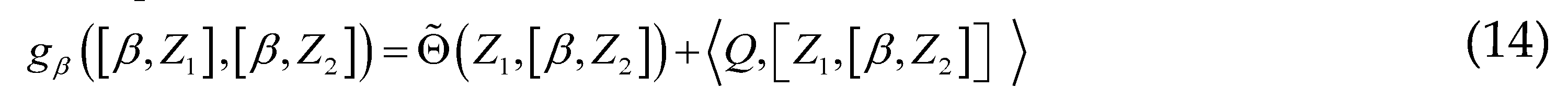

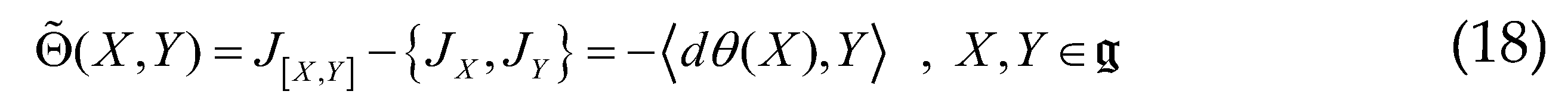

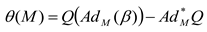

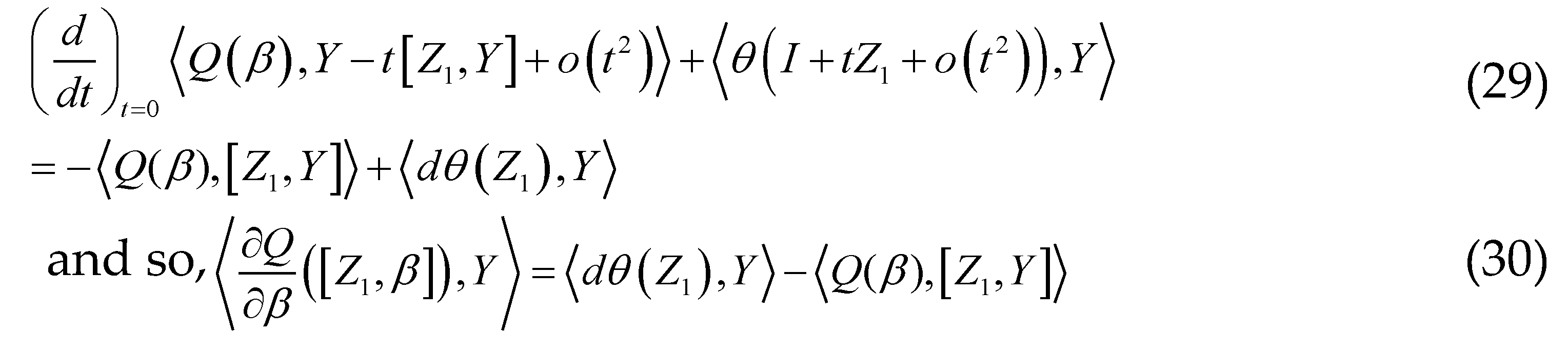

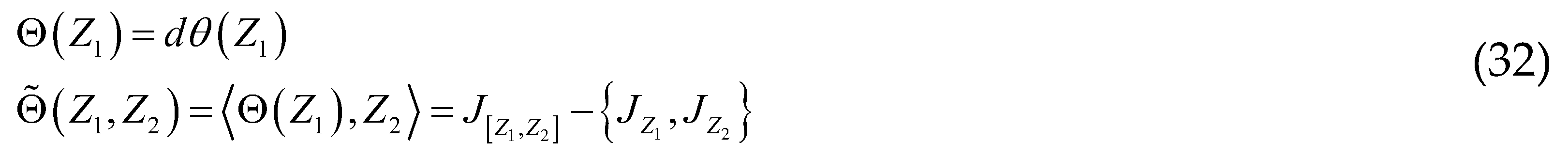

where

where  is a cocycle of the Lie algebra, defined by

is a cocycle of the Lie algebra, defined by  with θ a cocycle of the Lie group defined by

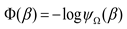

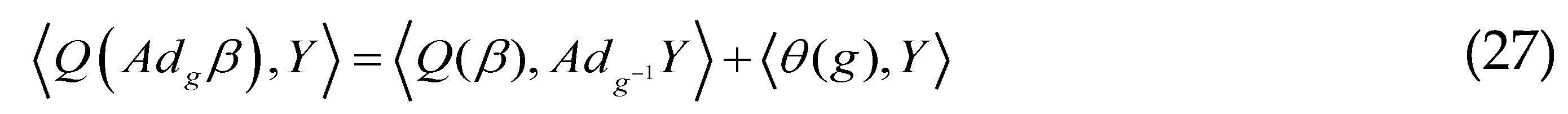

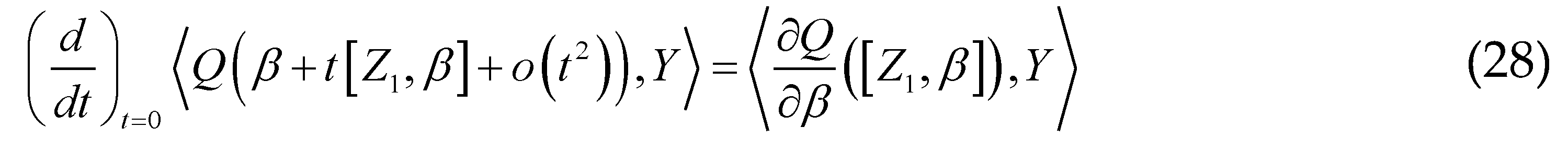

with θ a cocycle of the Lie group defined by  . We observe that the Riemannian Souriau metric, introduced with the symplectic cocycle, is a generalization of the Fisher metric, which we call the Souriau-Fisher metric, which retains the property of being defined as the Hessian of the logarithm of the function of partition

. We observe that the Riemannian Souriau metric, introduced with the symplectic cocycle, is a generalization of the Fisher metric, which we call the Souriau-Fisher metric, which retains the property of being defined as the Hessian of the logarithm of the function of partition  as in classical information geometry. We will establish the equality of two terms, between the definition of Souriau based on the cocycle of the Lie group

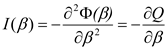

as in classical information geometry. We will establish the equality of two terms, between the definition of Souriau based on the cocycle of the Lie group  and parameterized by the “geometric heat” Q (element of the dual space of the Lie algebra) and the “geometric temperature”

and parameterized by the “geometric heat” Q (element of the dual space of the Lie algebra) and the “geometric temperature”  (element of the Lie algebra) and the Hessian of the characteristic function with respect to the variable

(element of the Lie algebra) and the Hessian of the characteristic function with respect to the variable  :

:

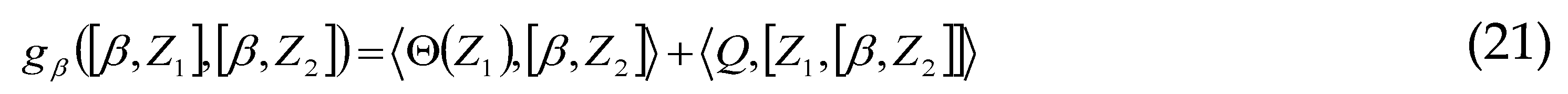

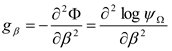

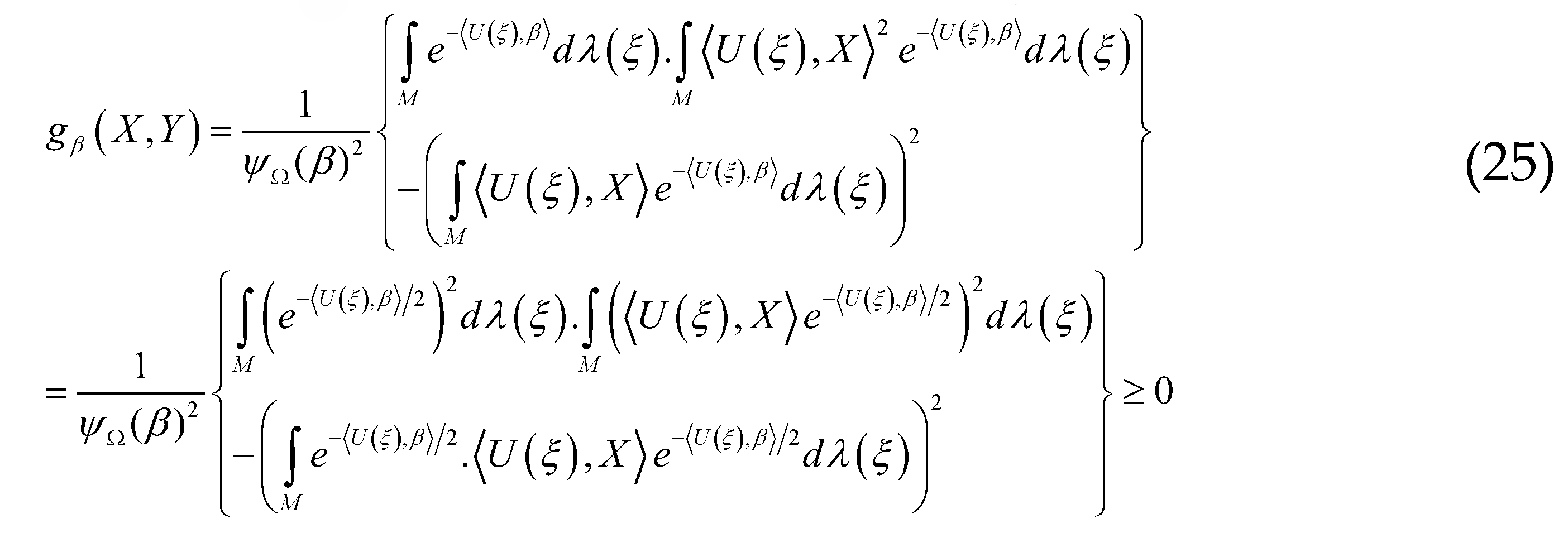

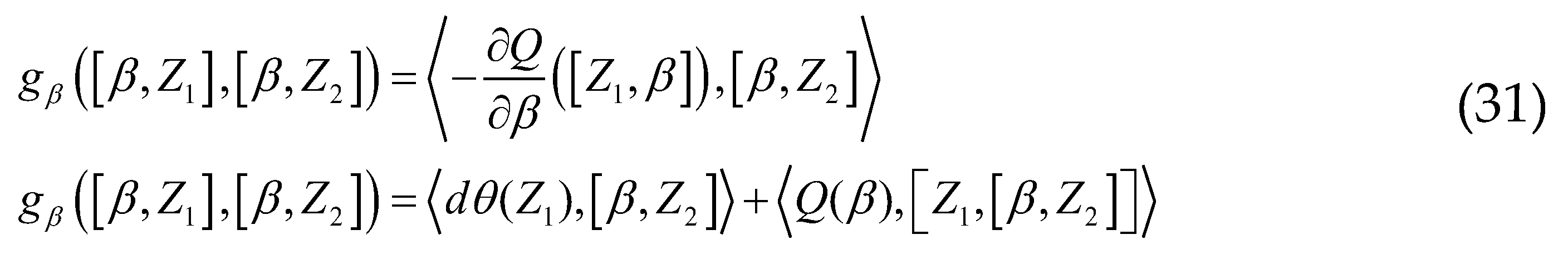

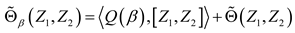

, either gβ the Hessian form on

, either gβ the Hessian form on  with the potential

with the potential  . For

. For  , we define:

, we define:

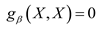

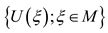

if and only if

if and only if  is independent of

is independent of  , which means that the set

, which means that the set  is contained in an affine hyperplane in

is contained in an affine hyperplane in  perpendicular to the vector

perpendicular to the vector  . We have seen that

. We have seen that  , which is a generalization of the classic Fisher metric from information geometry , and will give the relation the Riemannian metric introduced by Souriau:

, which is a generalization of the classic Fisher metric from information geometry , and will give the relation the Riemannian metric introduced by Souriau:

we have for everything :

we have for everything :

and the right-hand side of the other equation is calculated as follows:

and the right-hand side of the other equation is calculated as follows:

for the expression above:

for the expression above:

, it is an extension of the KKS (Kirillov-Kostant-Souriau) 2-form in the case of non-zero cohomology. Introduced by Souriau, we can define this metric extension of Fisher with the 2-form of Souriau:

, it is an extension of the KKS (Kirillov-Kostant-Souriau) 2-form in the case of non-zero cohomology. Introduced by Souriau, we can define this metric extension of Fisher with the 2-form of Souriau:

.

. .

. : To prove this equation, we need to consider the parameterized curve . The parameterized curve passes, for , through the point , since is the identical map of the Lie algebra . This curve is in the adjoint orbit of . So by taking its derivative with respect to , then for , we obtain a tangent vector in to the deputy orbit of this point. When takes all possible values in , the vectors thus obtained generate the entire tangent vector space at the orbit of this point:

: To prove this equation, we need to consider the parameterized curve . The parameterized curve passes, for , through the point , since is the identical map of the Lie algebra . This curve is in the adjoint orbit of . So by taking its derivative with respect to , then for , we obtain a tangent vector in to the deputy orbit of this point. When takes all possible values in , the vectors thus obtained generate the entire tangent vector space at the orbit of this point:

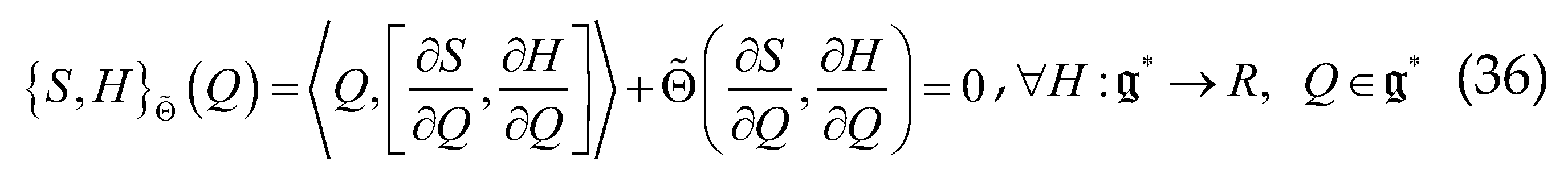

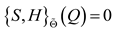

2.5. Hidden geometric definition of Entropy as Casimir function in Souriau’sequation

, then we can deduce that

, then we can deduce that  .

. , that characterizes an invariant Casimir function in the case of non-zero cohomology , which we propose to write with Poisson brackets, where:

, that characterizes an invariant Casimir function in the case of non-zero cohomology , which we propose to write with Poisson brackets, where:

, then the generalized Casimir condition

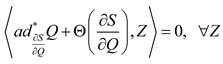

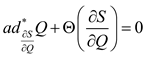

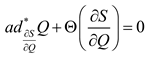

, then the generalized Casimir condition  . This previous Lie-Poisson equation is equivalent to the modified Lie-Poisson variational principle :

. This previous Lie-Poisson equation is equivalent to the modified Lie-Poisson variational principle : , that is to say:

, that is to say:

which we can develop to find the Casimir equation:

which we can develop to find the Casimir equation:

[…] Angular momentum is transmitted to the gas when the molecules collide with the rotating walls, which changes the Maxwell distribution at each point, moving its origin. The walls act as a reservoir of angular momentum. Their movement is characterized by a certain angular speed, and the angular speeds of the fluid and the walls become equal at equilibrium, exactly like the equalization of temperature by energy exchanges. (Balian 1991, p.339)

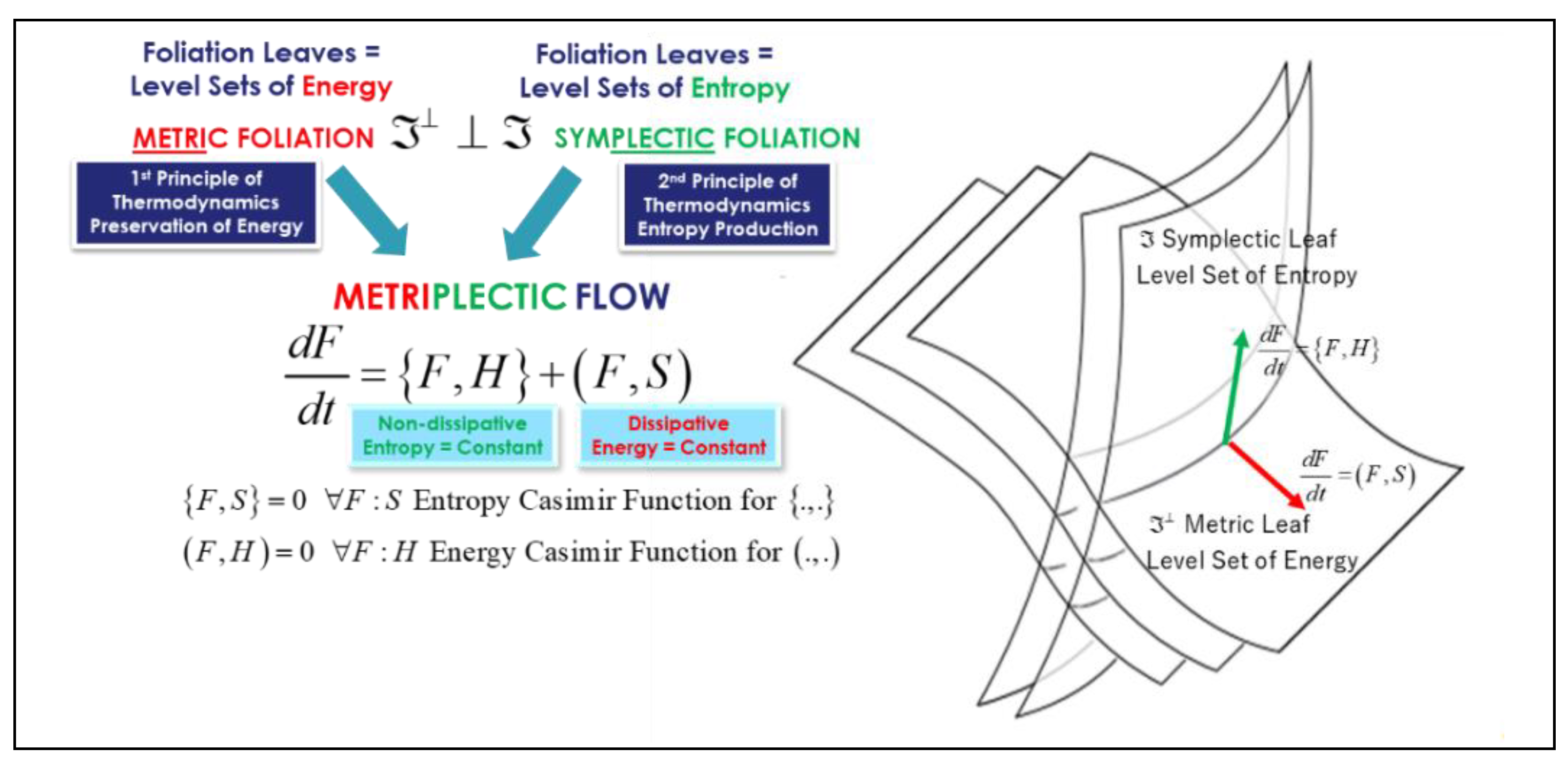

3. Metriplectic Flow and Webs model of Dissipative Thermodynamics

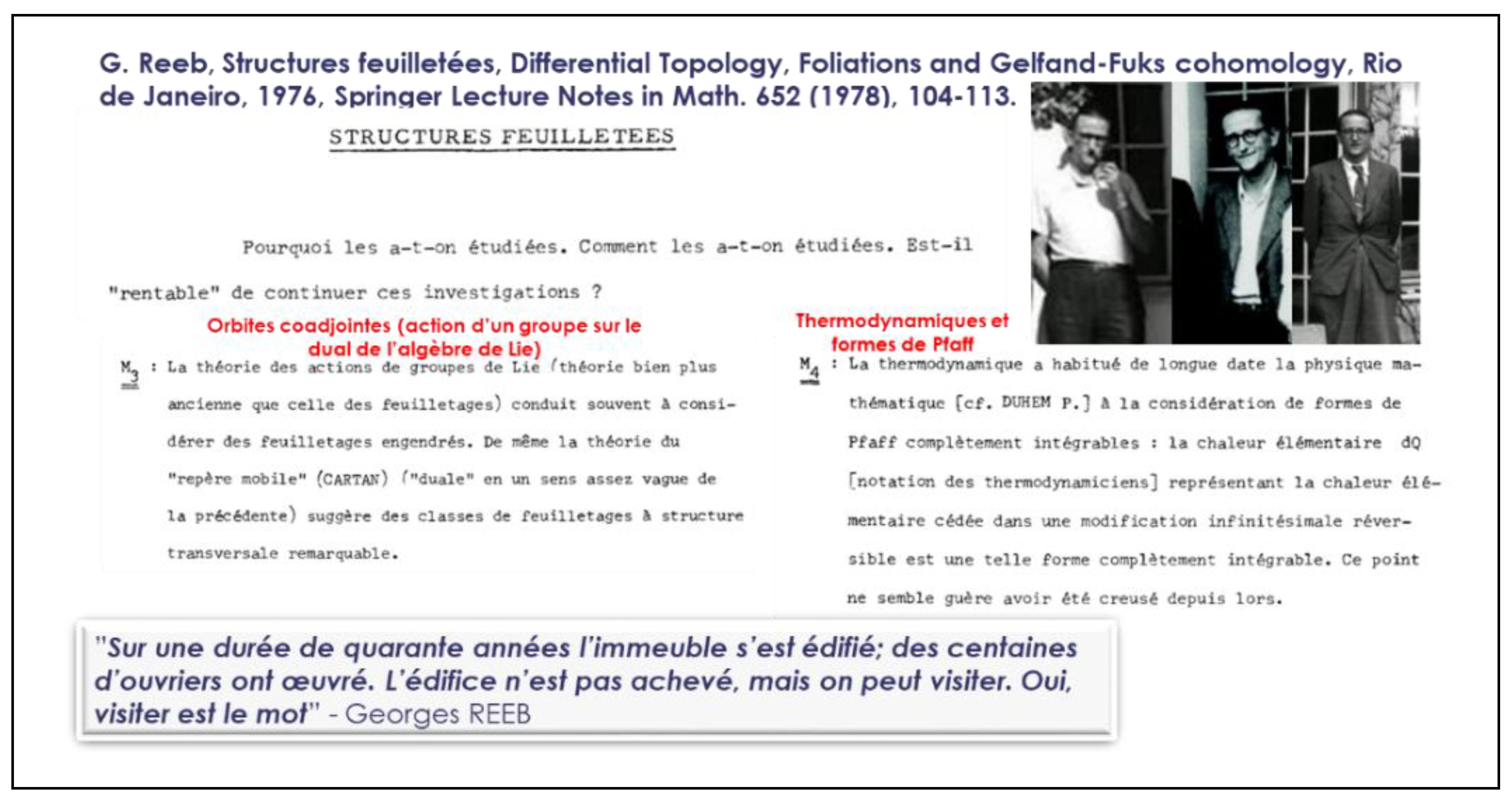

3.1. Theory of Foliation from Ehresmann and Reeb to Libermann

[…] The theory of the action of Lie groups (a much older theory than that of foliations) often leads to considering the generated foliations. Likewise , the theory of the “moving frame” (Cartan) (“dual” in a rather vague sense of the previous one) suggests classes of foliations with a remarkable transverse structure. (Reeb 1959, p. 110)

[…]Thermodynamics has long accustomed mathematical physics [cf. Duhem P.] to the consideration of completely integrable Pfaff forms : the elementary heat dQ [notation of thermodynamicists] representing the elementary heat given up in an infinitesimal reversible modification is such a completely integrable form. This point hardly seems to have been explored since then. (Reeb 1959, p. 110)

3.2. Transverse Symplectic foliation model of dissipative thermodynamics and the metriplectic flow

4. Thermodynamics as a Science of Symmetry by Herbert B. Callen

[…] every continuous symmetry of a system implies a conservation theorem, and vice versa … The most primitive class of symmetries is the class of continuous spacetime transformations. The (presumed) invariance of physical laws under time translation implies the conservation of energy. Symmetry under spatial translation implies conservation of momentum, and rotational symmetry implies conservation of angular momentum.(Callen, p.425)

[…] The most immediately evident conserved coordinate is, of course, the energy (time-translation symmetry). Its relevance as a thermodynamic coordinate underlies the "first law" of thermodynamics. Time-translation, spatial translation, and spatial rotation symmetries are interrelated in a single class of continuous space-time symmetries. The symmetry interpretation of thermodynamics immediately suggests, then, that energy, linear momentum, and angular momentum should play fully analogous roles in thermodynamics. The equivalence of these roles is rarely evident in conventional treatments, which appear to grant the energy a misleadingly unique status. The momentum and the angular momentum are generally suppressed by restricting the theory to systems at rest, constrained by external "clamps." Nevertheless, it is evident that in principle the linear momentum does appear in the formalism in a form fully equivalent to the energy, for relativistic considerations imply that the energy in one frame appears partially as linear momentum in another frame. Similarly, the angular momentum is only occasionally introduced explicitly into thermodynamic formalisms (as in astrophysical applications to rotating galaxies); it appears, for instance, in the "Boltzmann factor," , additively and symmetrically with the energy. To stress these facts we might well amend the first law to read that "the extended first law of thermodynamics is the symmetry of the laws of physics under space and time translations and under spatial rotation.".(Callen 1974 p.427)

5. Last works of Jean-Marie Souriau on Thermodynamics

Acknowledgments

References

- Albert C (1989) Le théorème de réduction de Marsden-Weinstein en géométrie cosymplectique et de contact. Journal of Geometry and Physics 6(4):627–649.

- Arnold VI (1966) Sur la géométrie différentielle des groupes de Lie de dimension infinie et ses applications à l'hydrodynamique des fluides parfaits. Annales de l'institut Fourier 19(1):319-361.

- Arnold VI, Givental AB (1990) Symplectic Geometry. In: Arnol'd VI and Novikov SP (eds). Dynamical Systems IV Symplectic Geometry and its Applications, Encyclopaedia of Mathematical Sciences, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 1-136.

- Audin M (2008) Differential Geometry, Strasbourg, 1953. Notices from the AMS 55(3):366-370.

- Bachelard G (1973) Étude sur l’évolution d’un problème de physique: La propagation thermique dans les solides. Vrin, Paris.

- Balian R, Alhassid Y, Reinhardt H (1986) Dissipation in many-body systems: a geometric approach based on information theory. Physical Reports 131:1-146.

- Balian R, Valentin P (2001) Hamiltonian structure of thermodynamics with gauge. The European Physical Journal B, Condensed Matter and Complex Systems 21:269-282.

- Balian R (2015) François Massieu et les potentiels thermodynamiques. Évolution des disciplines et histoire des découvertes, n° Avril, Académie des Sciences, Paris.

- Barbaresco F (2018) Higher Order Geometric Theory of Information and Heat Based on Poly-Symplectic Geometry of Souriau Lie Groups Thermodynamics and Their Contextures: The Bedrock for Lie Group Machine Learning. Entropy 20(11):840-900.

- Barbaresco F (2019a) Jean–Louis Koszul and the elementary structures of information geometry. In: Nielsen F (eds). Geometric Structures of Information, Springer, Switzerland, pp. 333–392.

- Barbaresco F (2019b) Lie Groups Thermodynamics & Souriau-Fisher Metric. In: Lachieze-Rey M (eds). Souriau 2019 Conference Proceedings, Institut Henri Poincaré, Paris.

- Barbaresco F (2019c) Souriau Exponential Map Algorithm for Machine Learning on Matrix Lie Groups. In: Nielsen F and Barbaresco F (eds), Geometric Science of Information GSI’19, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 11712, Springer, Berlin, pp. 85–95.

- Barbaresco F (2020) Lie Group Statistics and Lie Group Machine Learning Based on Souriau Lie Groups Thermodynamics & Koszul-Souriau-Fisher Metric: New Entropy Definition as Generalized Casimir Invariant Function in Coadjoint Representation. Entropy (22,):642-700.

- Barbaresco F (2021a) Souriau-Casimir Lie Groups Thermodynamics and Machine Learning. In: Nielsen F and Barbaresco F (eds). Geometric Structures of Statistical Physics, Information Geometry, and Learning, Springer, Berlin, pp. 53–83.

- Barbaresco F (2021b) Koszul lecture related to geometric and analytic mechanics, Souriau’s Lie group thermodynamics and information geometry. Information Geometry Journal, Springer 4:245–262.

- Barbaresco F (2021c) Invariant Koszul Form of Homogeneous Bounded Domains and Information Geometry Structures. In: Nielsen F (eds). Progress in Information Geometry. Signals and Communication Technology, Springer, Berlin, Germany, pp. 89-126.

- Barbaresco F (2021d) Jean-Marie Souriau’s Symplectic Model of Statistical Physics: Seminal Papers on Lie Groups Thermodynamics - Quod Erat Demonstrandum. In: Nielsen F and Barbaresco F (eds). Geometric Structures of Statistical Physics, Information Geometry, and Learning, Springer, Berlin, pp. 12–50.

- Barbaresco F (2021e) Archetypal Model of Entropy by Poisson Cohomology as Invariant Casimir Function in Coadjoint Representation and Geometric Fourier Heat Equation. In: Nielsen F and Barbaresco F (eds). Geometric Science of Information GSI’21, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 12829. Springer, pp. 417–429.

- Barbaresco F (2022a) Symplectic theory of heat and information geometry. Handbook of Statistics, special issue Geometry and Statistics 46(4):107-143.

- Barbaresco F (2022b) Symplectic Foliation Structures of Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics as Dissipation Model: Application to Metriplectic Nonlinear Lindblad Quantum Master Equation. Entropy 24 :1626-1662.

- Barbaresco F (2022c) Densité de probabilité gaussienne à maximum d’Entropie pour les groupes de Lie basée sur le modèle symplectique de Jean-Marie Souriau. Proceedings of the GRETSI’22 Conference, Nancy, France.

- Barbaresco F (2022d) Théorie symplectique de l’Information et de la chaleur: Thermodynamique des groupes de Lie et définition de l’Entropie comme fonction de Casimir. GRETSI’22, Nancy. Retrieved via: https://gretsi.fr/data/colloque/pdf/2022_barbaresco696.pdf [07/09/2022].

- Barbaresco F (2022e) Entropy Geometric Structure as Casimir Invariant Function in Coadjoint Representation: Geometric Theory of Heat & Information Geometry Based on Souriau Lie Groups Thermodynamics and Lie Algebra Cohomology. In: Freeden W and Zuhair Nashed M (eds). Frontiers in Entropy Across the Disciplines, World Scientific, Singapore, pp. 133–158.

- Barbaresco F (2022f) Souriau Entropy Based on Symplectic Model of Statistical Physics: Three Jean-Marie Souriau’s Seminal Papers on Lie Groups Thermodynamics. In: Freeden W and Zuhair Nashed M (eds). Frontiers in Entropy Across the Disciplines, World Scientific, Singapore, pp. 55–90.

- Barbaresco F (2023) Symplectic Foliation Transverse Structure and Libermann Foliation of Heat Theory and Information Geometry. In: Nielsen F and Barbaresco F (eds) Geometric Science of Information GSI’23. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 14072, Springer, Berlin, pp. 152–164.

- Basart H, Lichnerowicz A (1982) Variétés de poisson et star-produits tangentiels. Ibidem 1(295) :681-685.

- Benayoun L (1999) Méthodes géométriques pour l’étude des systèmes thermodynamiques et la génération d’équations d’état. PhD Thesis, Institut National Polytechnique de Grenoble, Grenoble.

- Benayoun L, Valentin P (2022) Evolution of equations of state through contact transformations. Fluid Phase Equilibria 194:439-449.

- Bourguignon JP (2019) Jean-Marie Souriau and Symplectic Geometry, Souriau’19 conference, 50th birthday of Jean-Marie Souriau’s Book, Paris, Retrieved via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=93hFolIBo0Q&t=3s [27/05/2019].

- Callen HB (1973) A Symmetry Interpretation of Thermodynamics. In: Domingos JDD (eds.). Foundations of Continuum Thermodynamics, Instituto de Alta Cultura-Núcleo de Estudos de Engenharia Mecanica, pp. 61–79.

- Callen, HB (1974) Thermodynamics as a Science of Symmetry, Foundations of Physics 4(4):423–443.

- Callen HB (1985) Thermodynamics and An Introduction to Thermostatistics, 2nd edition, Wiley, New York.

- Carnot S (1824a) Réflexions sur la Puissance Motrice du Feu et sur les Machines propres à développer cette Puissance, Bachelier, Paris.

- Carnot S (1824b) Extracts from unpublished notes by Sadi Carnot on mathematics, physics and other subjects. Gallica, Paris.

- Cartan E (1899) Sur certaines expressions différentielles et le problème de Pfaff. Annales de l’Ecole Normale Supérieure 16 :239-332.

- Cartan E (1958) Leçons sur les invariants intégraux, Hermann, Paris.

- Cartier P (1994) Some fundamental techniques in the theory of integrable systems. In: Babelon O, Cartier P, Kosmann-Schwarzbach Y (eds).Lectures on Integrable Systems, World Scientific Publishing, pp. 1-41.

- Casimir HGB (1931) Uber die konstruktion einer zu den irreduziblen darstellungen halbeinfacher kontinuierlicher gruppen gehörigen differentialleichung. Proceedings of Royal Society Amsterdam 34:844–846.

- Casimir HBG (1945) On onsager’s principle of microscopic reversibility. Reviews of Modern Physics 17:343-362.

- Coleman CP (1994) The Search for Stable Equilibria on Coadjoint Orbits and Applications to Dissipative Processes. University of California, Berkeley report. Retrieved via: https://www.cds.caltech.edu/~marsden/wiki/uploads/projects/geomech/Coleman1994.pdf.

- Condevaux M, Dazord P, Molino P (1988) Géométrie du moment. Publications du département de mathématiques de Lyon, fascicule 1B, Séminaire Sud-Rhodanien 1(5) :131-160.

- Coquinot B, Morrison PJ (2020) A General Metriplectic Framework with Application to Dissipative Extended Magnetohydrodynamics. Journal of Plasma Physics 86(3):835860302.

- Cosserat O (2023) Theory and Construction of Structure Preserving Integrators in Poisson Geometry. Differential Geometry. Université de La Rochelle, La Rochelle.

- Darboux G (1882a) Sur le problème de Pfaff. Bulletin des sciences mathématiques et astronomiques 2(6):14-36.

- Darboux G (1882b) Sur le problème de Pfaff, Bulletin des sciences mathématiques et astronomiques 2(6):49-62.

- Dazord P (1983) Feuilletages et mécanique hamiltonienne. Seminaire de geometrie, université de Lyon I 3(4) :1-49.

- Dazord P, Molino P (1988) Gamma-Structures poissonniennes et feuilletages de Libermann, Publications du département de mathématiques de Lyon, fascicule 1B, Séminaire Sud-Rhodanien 1(2):69-89.

- Dazord P, Delzant T (1987) Le problème général des variables actions-angles. Journal of Differential Geometry 26 :223-251.

- Delzant T (1986) Variables actions-angles non commutatives et exemples d'images convexes de l'application moment, Paris 6 University, Paris.

- Delzant T (1988) Hamiltoniens périodiques et images convexes de l’application moment. Bulletin de la Société Mathématique de France 116(3)315–339.

- de Saxcé G, Vallée C (2012) Bargmann group, momentum tensor and Galilean invariance of Clausius–Duhem inequality. International Journal of Engineering Science 50(1):216-232.

- de Saxcé G, Vallée C (2016) Galilean Mechanics and Thermodynamics of Continua. Wiley, Hoboken.

- de Saxcé G (2016) Link between Lie Group Statistical Mechanics and Thermodynamics of Continua. Entropy 18:254-269.

- de Saxcé G (2019) Euler-Poincaré equation for Lie groups with non null symplectic cohomology. Application to the mechanics. In: Nielsen F and Barbaresco F (eds), Geometric Science of Information GSI’19, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 11712, Springer, Berlin, pp. 66–74.

- de Saxcé G, Marle CM (2022) Structure des Systèmes Dynamiques Jean-Marie Souriau’s Book 50th Birthday. In: Barbaresco F and Nielsen F (eds), Geometric Structures of Statistical Physics, Information Geometry, and Learning, Springer Berlin, pp. 3-11.

- Ehresmann, C (1951) Sur la théorie des variétés feuilletées. Rendieonti di Matematiea 5(10):64-83.

- Fedida E (1973) Feuilletages du plan, feuilletages de Lie. PhD University of Strasbourg, Strasbourg.

- Fedida E (1974) Sur l’existence des feuilletages de Lie. Compte-Rendu de l’Académie des Sciences Paris 278:835–837.

- Fedida E (1978) Sur la théorie des feuilletages associée au repère mobile : cas des feuilletages de lie. In: Schweitzer PA (eds). Differential Topology, Foliations and Gelfand-Fuks Cohomology, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Springer, Berlin, pp. 183–195.

- Françoise JP (2013) Systèmes Dynamiques appliqués aux Oscillations. 21ème Congrès Français de Mécanique, Bordeaux. Retrieved via: https://hal.science/hal-03441433/document [22/11/21].

- Gallisot F (1952) Les formes extérieures en mécanique. Annales de l’Institut Fourier 4 :145–297.

- Gibbs JW (1875) Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances. The transactions of the Connecticut Academy 3:108-248 and 3:343-524.

- Gibbs JW (1902) Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics, developed with Especial Reference to the Rational Foundation of Thermodynamics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Goursat E (1922) Leçons sur les problèmes de Pfaff, Hermann, Paris.

- Hadamard J (1906) Review of Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics, Developed with Special Reference to the Rational Foundations of Thermodynamics by J. Willard Gibbs. Bulletin of American Mathematical Society 12(4):194–210.

- Haefliger A (2016) Naissance des feuilletages, d'Ehresmann-Reeb à Novikov. In : Kouneiher J, Flament D, Nabonnand P and Szczeciniarz JJ (eds). Géométrie au XXe Siècle, 1930-2000, Histoire et Horizons, Hermann, Paris, pp. 99–110.

- Hamoui A, Lichnerowicz A (1982) Sur la quantification d'un système dynamique à hamiltonien dépendant du temps. Comptes rendus Académie des Sciences Paris 294(1) :705-710.

- Hubmer GF, Titulaer UM (1987) The Onsager-Casimir relations revisited. Journal of Statistical Physics 49:331–346.

- Jayne N (1992) Legendre Foliations on Contact Metric Manifolds, Massey University PhD thesis, Massey.

- Jaynes ET (1957a) Information Theory and Statistical Mechanics. The Physical Review 106(4):620-630.

- Jaynes ET (1957b) Information Theory and Statistical Mechanics II. Physics Revue 108(2):171–190.

- Kapranov M (2011) Thermodynamics and the moment map, arXiv:1108.3472v1. Retrieved via: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1108.3472 [17/08/2011]. [CrossRef]

- Khesin BA, Tabachnikov SL (2014) Arnold Swimming Against the Tide, AMS Non-Series Monographs, Volume 86, Moscow, Retrieved via: https://doi.org/10.1090/mbk/086. [CrossRef]

- Kirillov AA (1974) Eléments de la théorie des représentations. Mir, Moscow.

- Kirillov AA (2004) Lectures on the orbit method. Volume 64 of Graduate Studies in Mathematics, American Mathematical Society, Providence.

- Kozlov VV (2004) Gibbs and Poincaré Statistical Equilibria in Systems with Slowly Varying Parameters. Doklady Mathematics 69(2):278–281.

- Lagrange JL (1855) Mécanique Analytique. Mallet-Bachelier, Paris.

- Lawson JrH (1974) Foliations. Bulletin of American Mathematics Society 80:369–418.

- Libermann P (1954) Sur Ie problème d'équivalence de certaines structures infinitésimales regulières. Annali di Matematica Pura ed Applicata 36:27-120.

- Libermann P (1959) Automorphismes infinitésimaux des structures symplectiques et de contact. Collection de Géométrie Différentielle Globale, Gauthier-Villars, Paris.

- Libermann P (1983) Problèmes d’équivalence et géométrie symplectique. Astérisque 107:43-68.

- Libermann P (1986) Sur quelques propriétés de géométrie homogène. In : Dufour JC (eds). Séminaire Sud-Rhodanien de Géométrie, Travaux en cours, Hermann, Paris, pp. 91-106.

- Libermann P, Marle CM (1987) Symplectic Geometry and analytical Mechanics. Reidel, Dordrecht.

- Libermann P (1989) Cartan-Darboux theorems for Pfaffian forms on foliated manifolds. Proceedings VIth International Colloquium Differential Geometry 125-144.

- Libermann P (1991) Legendre Foliations on Contact Manifolds, Differential Geometry and its Applications 1:57-76.

- Libermann P (2005) La géométrie différentielle d’Elie Cartan à Charles Ehresmann et André Lichnerowicz. In : Kouneiher J, Flament D, Nabonnand P, Szczeciniarz JJ (eds). Géométrie au XXe siècle, 1930-2000. Histoire et horizons, Hermann, Paris, pp. 191–208.

- Lichnerowicz A (1976) Variétés symplectiques, canoniques et systèmes dynamiques. In : Rund H and Forbes W (eds). Topics in Differential Geometry, volume in honour of ET Davies, Academic Press, New York, pp. 57-85.

- Lichnerowicz A (1982a) Géométrie différentielle des variétés de contact. Journal de Mathématiques pures et appliquées 4 :345-380.

- Lichnerowicz A (1982b) Variétés de Poisson et feuilletages. Annales de la Faculté des Sciences, Toulouse 4:195-262.

- Lichnerowicz A (1983a) Formes caractéristiques d'un feuilletage et classes de cohomologie de l'algèbre des vecteurs tangents à valeurs dans les formes normales. Comptes rendus Académie des Sciences Paris 296(1):67-71.

- Lichnerowicz A (1983b) Quantum Mechanics and déformations of Geometrical Dynamics. In: Barut AO (eds). Quantum Theory, Groups, Fields and Particles, Reidel, Dordrecht, pp. 3-82.

- Lichnerowicz A, Tran-Van-Tan (1983c) Feuilletages, géométrie riemannienne et géométrie symplectique. Ibidem 296(1):205-210.

- Lichnerowicz, A (1983d) Physique mathématique, Cours du Collège de France 1982-1983, Institut de France 1:111-115.

- Lie S (1876) Allgemeine Theorie der partiellen Differentialgleichungen erster Ordnung. Mathematische Annalen 9:245-296.

- Lie S (1877) Allgemeine Theorie der partiellen Differentialgleichungen erster Ordnung (Zweite Abhandlung). Mathematische Annalen 11:464-557.

- Lie S (1890) Transformationsgruppen, I, II, III. Teubner, Berlin. Reprinted by Chelsea Publishing Company, New York.

- Lindblad G (1893) Non-Equilibrium Entropy and Irreversibility, D. Reidel, Dordrecht.

- Marle CM (2016) From Tools in Symplectic and Poisson Geometry to, J.-M. Souriau’s Theories of Statistical Mechanics and Thermodynamics. Entropy 18(10):370-416.

- Marle CM (2018) Géométrie Symplectique et Géométrie de Poisson. Calvage & Mounet, Paris.

- Marle CM (2019) Projection Stéréographique et Moments, Hal-02157930, Version 1. Retrieved via: https://hal.science/hal-02157930/document [06/07/2019].

- Marle CM (2020a) On Gibbs states of mechanical systems with symmetries. Journal of Geometry and Symmetry in Physics 57:45–85.

- Marle CM (2020b) Examples of Gibbs States of Mechanical Systems with Symmetries. Journal of Geometry and Symmetry in Physics 58:55–79.

- Marle CM (2021a) On Generalized Gibbs States of Mechanical Systems with Symmetries. arXiv, arXiv:2012.00582v2. Retrieved via: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2012.00582 [13/01/2021].

- Marle CM (2021b) États de Gibbs construits au moyen d’un moment de l’action hamiltonienne d’un groupe de Lie: Signification physique et exemples. Diaporama Bilingue Français–Anglais, Colloque en L’honneur de Jean-Pierre Marco. Retrieved via: https://marle.perso.math.cnrs.fr/diaporamas/GibbsStatesMomentMap.pdf [07/06/2021].

- Marle CM (2021c) Gibbs States on Symplectic Manifolds with Symmetries. Geometric Science of Information. In: Nielsen F and Barbaresco F (eds), Geometric Science of Information GSI’21, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 12829, Springer, Berlin, pp 237–244.

- Martinet J, Reeb G (1973) Sur une généralisation des structures feuilletées de codimension 1. In : Maslov V (eds). Dynamical systems, Academic Press, New York, pp. 177-184.

- Maschke B, Goreac G, Kirchhoff J (2024) Generating functions for irreversible Hamiltonian systems. arXiv:2404.04092v2. Retreived via: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2404.04092 [08/04/2024].

- Massieu F (1869a) Sur les Fonctions caractéristiques des divers fluides. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences Paris 69:858–862.

- Massieu F (1869b) Addition au précédent Mémoire sur les Fonctions caractéristiques. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences Paris 69:1057–1061.

- Massieu F (1873) Exposé des principes fondamentaux de la théorie mécanique de la chaleur (note destinée à servir d'introduction au Mémoire de l'auteur sur les fonctions caractéristiques des divers fluides et la théorie des vapeurs), Gallica, Paris.

- Massieu F (1876) Thermodynamique: Mémoire sur les Fonctions Caractéristiques des Divers Fluides et sur la Théorie des Vapeurs, Académie des Sciences Paris 1:92-110.

- Molino P (1989) Dualité symplectique, feuilletage et géométrie du moment. Publicacions Matematiques 33:533-541.

- Molitor M (2021) Kähler toric manifolds from dually flat spaces. arXiv:2109.04839v1. Retreived via: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2109.04839 [10/09/2021].

- Morrison PJ, Updike MH (2023) An inclusive curvature-like framework for describing dissipation: metriplectic 4-bracket dynamics. Physical Review E109:045202.

- Mrugala R (1978) Geometrical formulation of equilibrium phenomenological thermodynamics. Reports on Mathematical Physics 14(3):419-427.

- Mrugala R (2000) On contact and metric structures on thermodynamic spaces. Mathematical Aspects of Quantum Information and Quantum Chaos 1142:167-181.

- Nencka H, Streater RF (1999) Information Geometry for some Lie algebras. Infinite Dimensional Analysis, Quantum Probability and Related Topics 2(3):441-460.

- Noether E (1918) Invariante variationsprobleme. Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Gottingen, Abhandlungen der Mathematisch-Physikalischen Klasse 191:235-257.

- Nehorosev NN (1972) Action-angle variables and their generalizations. Translation Moscow Mathematical Society 26:180–198.

- Onsager L (1931) Reciprocal relations in irreversible processes I. Physical Review 37:405–426.

- Onsager L, Machlup S (1953a) Fluctuations and Irreversible Processes, Physical Review 91:1505-1510.

- Onsager L, Machlup S (1953b) Fluctuations and Irreversible Processes II. Systems with Kinetic Energy, Physical Review 91:1512–1515.

- Pang MY (1990) The Structure of Legendre Foliations. Transations of the American Mathematical Society 30(2):417-455.

- Pavlov VP, Sergeev VM (2008) Thermodynamics from the Differential Geometry Standpoint. Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 157(1):1484–1490.

- Pisano R (2024) Brief summaries on symmetries in the history of physics–mathematics: James Clerk Maxwell (1865–1873), Emmy Noether (1915–1918) and Albert Einstein (1905–1926). Journal of Physics: Conference Series IOP Oxford: 2877 012101.

- Poincaré H (1901) Sur une forme nouvelle des équations de la Mécanique. Compte-Rendus des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences Paris 18:48–51.

- Poincaré H (1908) Thermodynamique, cours de Sorbonne 2nd édition revue et corrigée, Gauthier-Villars, Paris.

- Reeb G (1952) Sur certaines propriétés topologiques des trajectoires des systèmes dynamiques. Académie royale de Belgique 27(9) :234-265.

- Reeb G (1956) Sur la théorie générale des systèmes dynamiques. Annales de l'institut Fourier 6:89-115.

- Reeb G (1959) Structures feuilletées. Bulletin de la Société Mathématique de France 87 :445–450.

- Reeb G (1978) Structures feuilletées. Differential Topology, Foliations and Gelfand-Fuks cohomology, Lecture Notes in Mathematics 652:104–113.

- Reeb G, Ehresmann C, Thom R, Libermann P (1964) Structures feuilletées, Colloques Internationaux Du Cnrs (CIDC), CNRS, Paris.

- Reech F (1858) Note sur un mémoire intitulé: Théorie des propriétés calorifiques et expansives des fluides élastiques. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Scinces Paris 46(2):84-89.

- Reech F (1869) Théorie des machines motrices et des effets mécaniques de la chaleur. Eugène Lacroix, Paris.

- Reinhart BL (1983) Differential Geometry of Foliations, vol. 99, Springer Verlag, Cham.

- Souriau JM (1952) Sur la stabilité des avions. PhD ONERA, Chatillon.

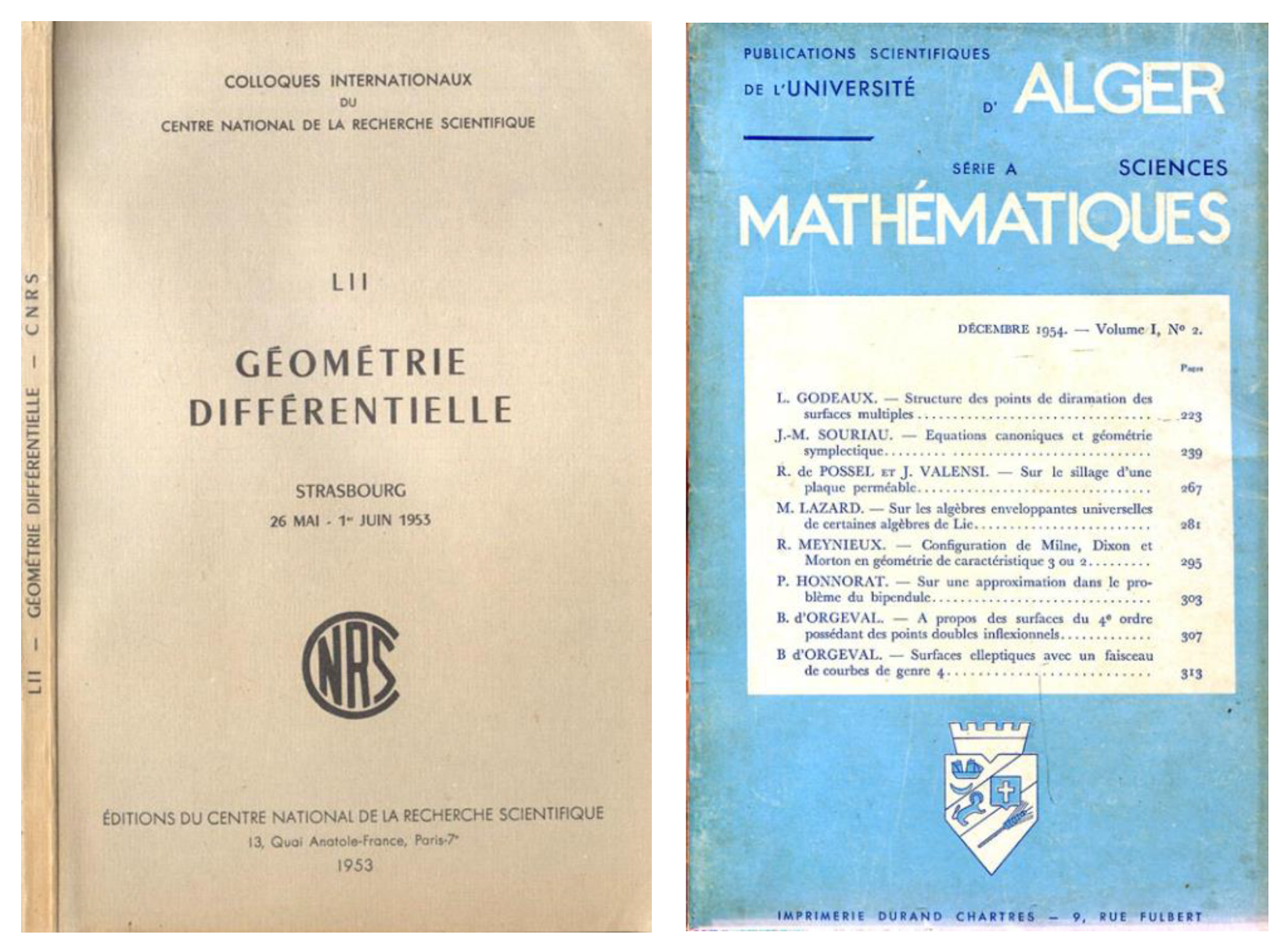

- Souriau JM (1953) Géométrie symplectique différentielle. Applications. In : Ehresmann C and Lichnerowicz A (eds). Colloque CNRS, Géométrie différentielle, Strasbourg, Editions du CNRS, Paris, pp. 53-59.

- Souriau JM (1954) Equations Canoniques et Géométrie Symplectique. Publications Scientifiques Universitaire d’Alger A(1):239–265.

- Souria JM (1965) Géométrie de l’Espace des Phases, Calcul des Variations et Mécanique Quantique. Tirage Ronéotypé, Faculté des Sciences, Marseille.

- Souriau JM (1966) Définition covariante des équilibres thermodynamiques. Supplement Il Nuovo Cimento 4:203–216.

- Souriau JM (1967) Réalisations d’algèbres de Lie au moyen de variables dynamiques. Il Nuovo Cimento A(49):197–198.

- Souriau JM (1969) Structure des systèmes dynamiques. Dunod, Paris.

- Souriau JM (1974) Mécanique statistique, groupes de Lie et cosmologie. In : Souriau JM (eds). Colloque International du CNRS Géométrie symplectique et physique Mathématique, CNRS, Marseille.

- Souriau JM (1975) Géométrie Symplectique et Physique Mathématique. Deux Conférences de Jean-Marie Souriau, Colloquium de la Société Mathématique de France, SMF, Paris.

- Souriau JM (1977) Thermodynamique et géométrie. In: Bleuler K and Reetz A (eds). Differential Geometry Methods in Mathematical Physics II, Springer, Berlin, pp. 369–397.

- Souriau JM (1978) Géométrie symplectique et physique mathématique, CNRS, Marseille.

- Souriau JM (1984) Mécanique Classique et Géométrie Symplectique. CNRS-CPT-84/PE.1695, CNRS, Marseille.

- Souriau JM (1986) La structure symplectique de la mécanique décrite par Lagrange en 1811. Mathématiques & Sciences Humaines 94:45–54.

- Souriau JM (1990) Titres & travaux : principaux thèmes de recherche, CNRS, Marseille.

- Souriau JM (1995) Itinéraire d’un mathématicien - Un entretien avec Jean-Marie Souriau. Propos recueillis par Patrick Iglesias, Le journal de maths des élèves 1(3):162-168.

- Souriau JM (1996) Grammaire de la Nature. Private publication. Retreived via: https://jmsouriau.klacto.net/Souriau.2007a.pdf [25/05/2007].

- Souriau JM (1997) Structure of dynamical systems, a symplectic view of physics. Progress in Mathematics. Birkhäuser, Boston.

- Souriau JM (2003) C’est quantique ? Donc c’est géométrique. Série Documents de travail (Équipe F2DS), Feuilletages-quantification géométrique : textes des journées d’étude. Retreived via : https://jmsouriau.klacto.net/JMS.html [10/05/2003].

- Souriau JM (2005) Les groupes comme universaux. In : Kouneiher J, Flament D., Nabonnand P., Szczeciniarz JJ (eds). Géométrie au XXe siècle, 1930-2000. Histoire et horizons, Hermann, Paris, pp.395-416.

- Souriau JM (2007) On Geometric Dynamics. Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems, 19:595–607.

- Streater RF (2007) Lost Causes in and beyond Physics, Springer, London.

- Thom R (1982) Logos et théorie des Catastrophes. René Thom talk at the Cerisy International Conference, Annales de la Fondation Louis de Broglie 27(4):575-596.

- Thomson W (1849) XXXVI.—An Account of Carnot’s Theory of the Motive Power of Heat;with Numerical Results deduced from Regnault’s Experiments on Steam. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 16(5):541-574.

- Trusdell C (1980) The Tragicomical History of Thermodynamics 1822-1854, Springer, Berlin.

- Vallée C, de Saxcé G, Marle CM (2012) Hommage à Jean-Marie Souriau, Gazette des Mathématiciens 133:97-102.

- Vojta G (1990) Symplectic Formalism for the Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes, Annalen Der Physik 502(2):251-258.

- Wolak RA (1989) Foliated and associated geometric structures on foliated manifolds. Annales de la faculté des sciences de Toulouse 5e série 10(3):337-360.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).