Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fundamentals of Quantum Computing

2.2. Quantum Algorithms in Genetic Diagnostics

2.3. Design and Simulation of Quantum Circuits

2.4. Experimental Configuration

3. Results

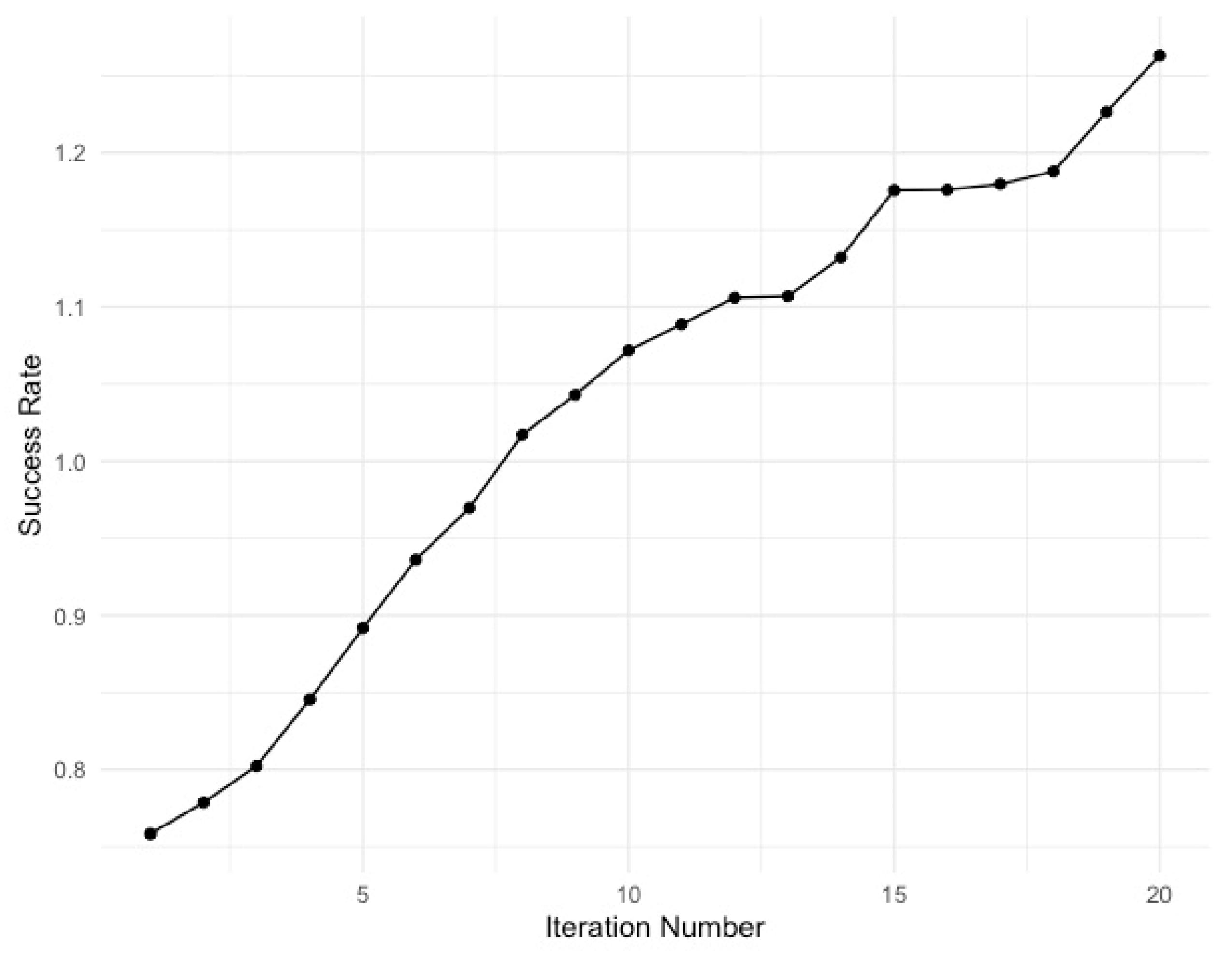

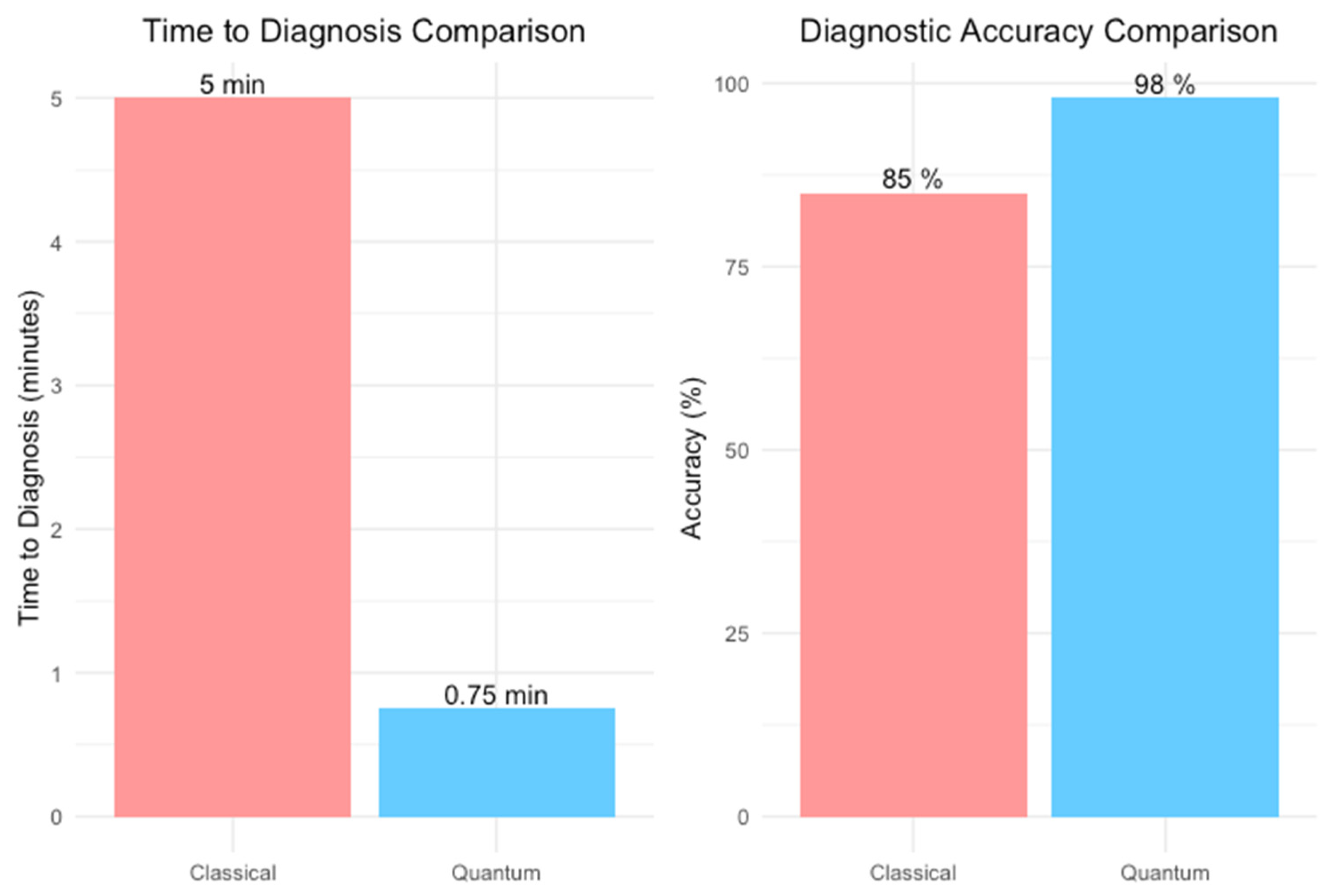

3.1. Gover’s Algorithm Performance

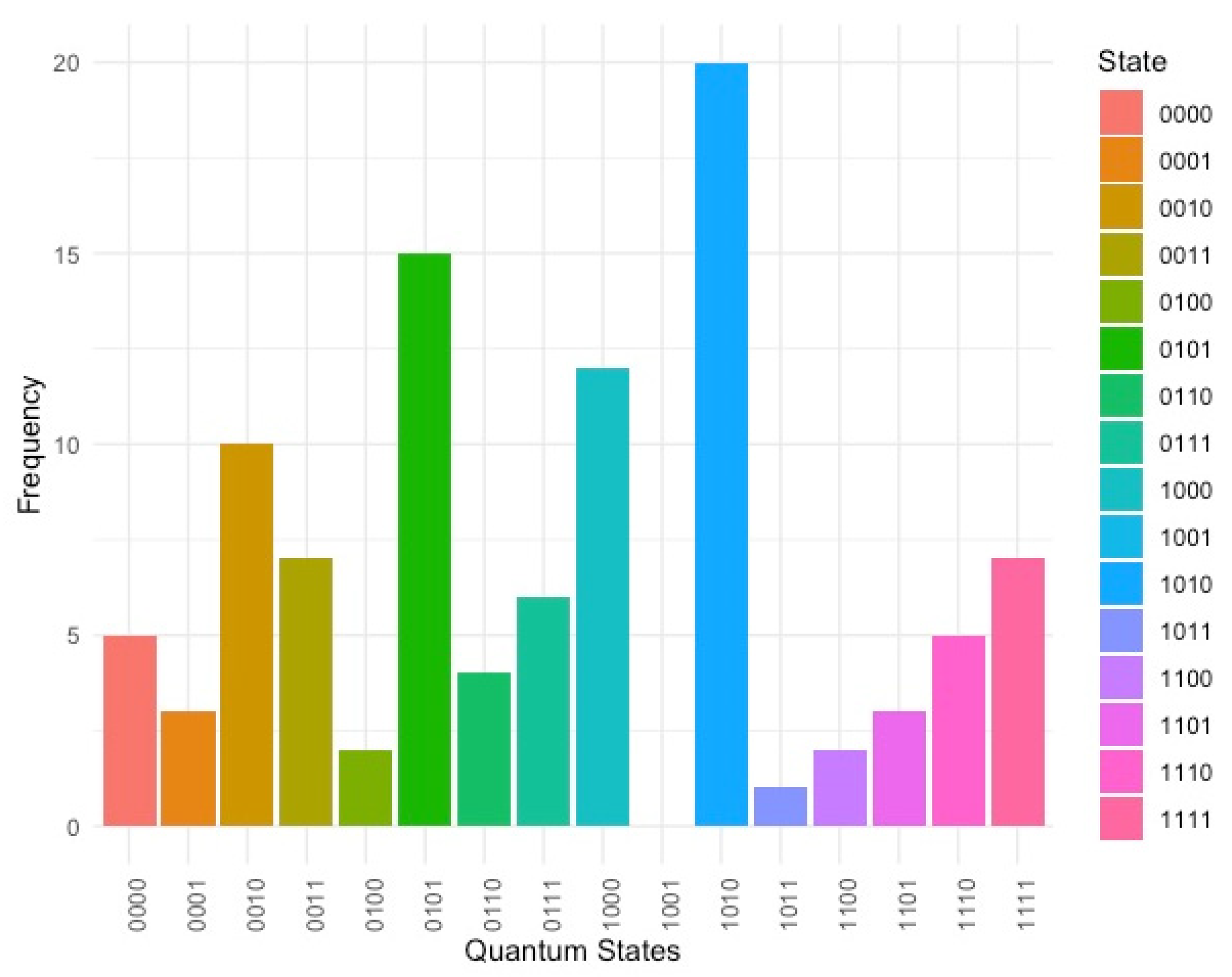

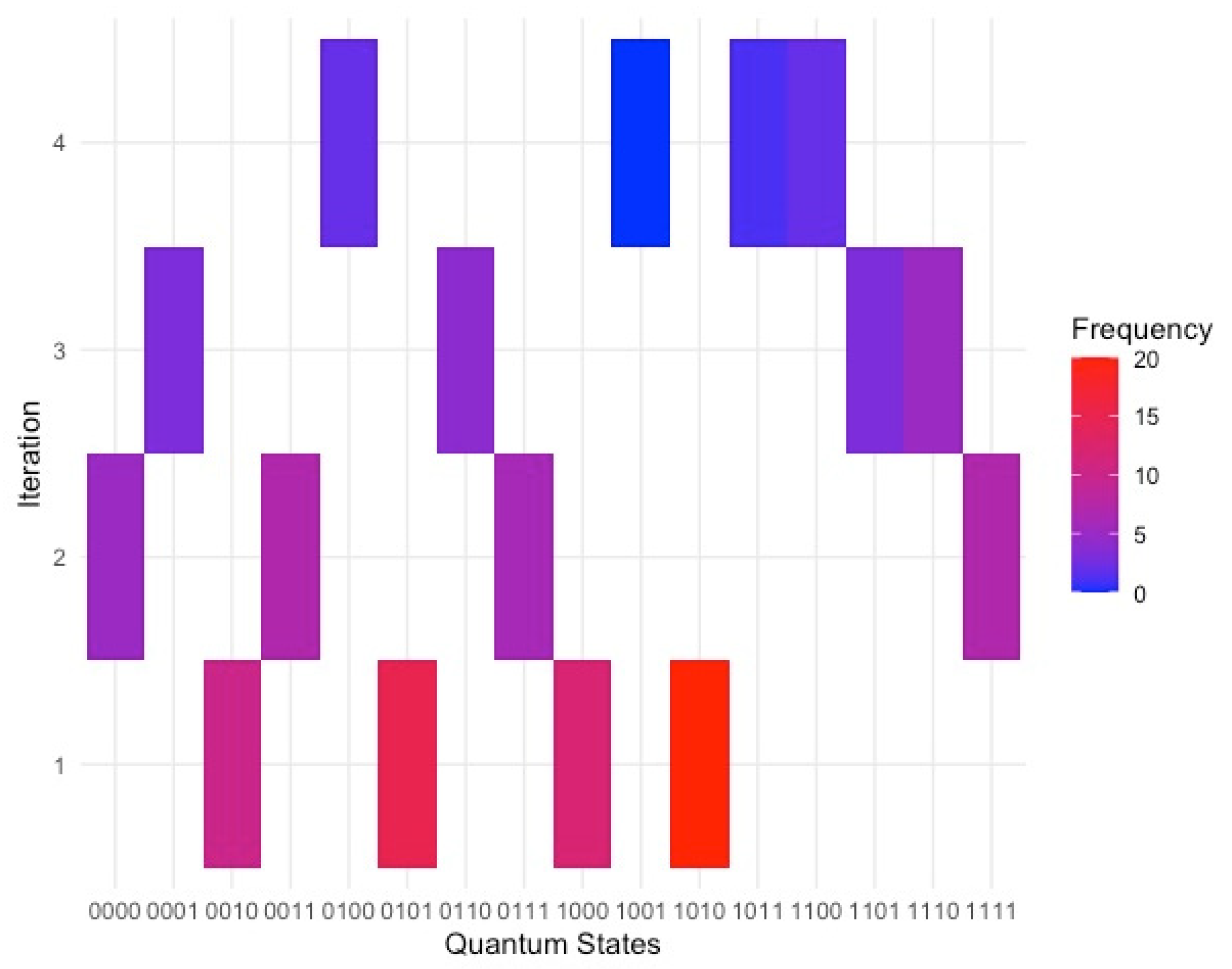

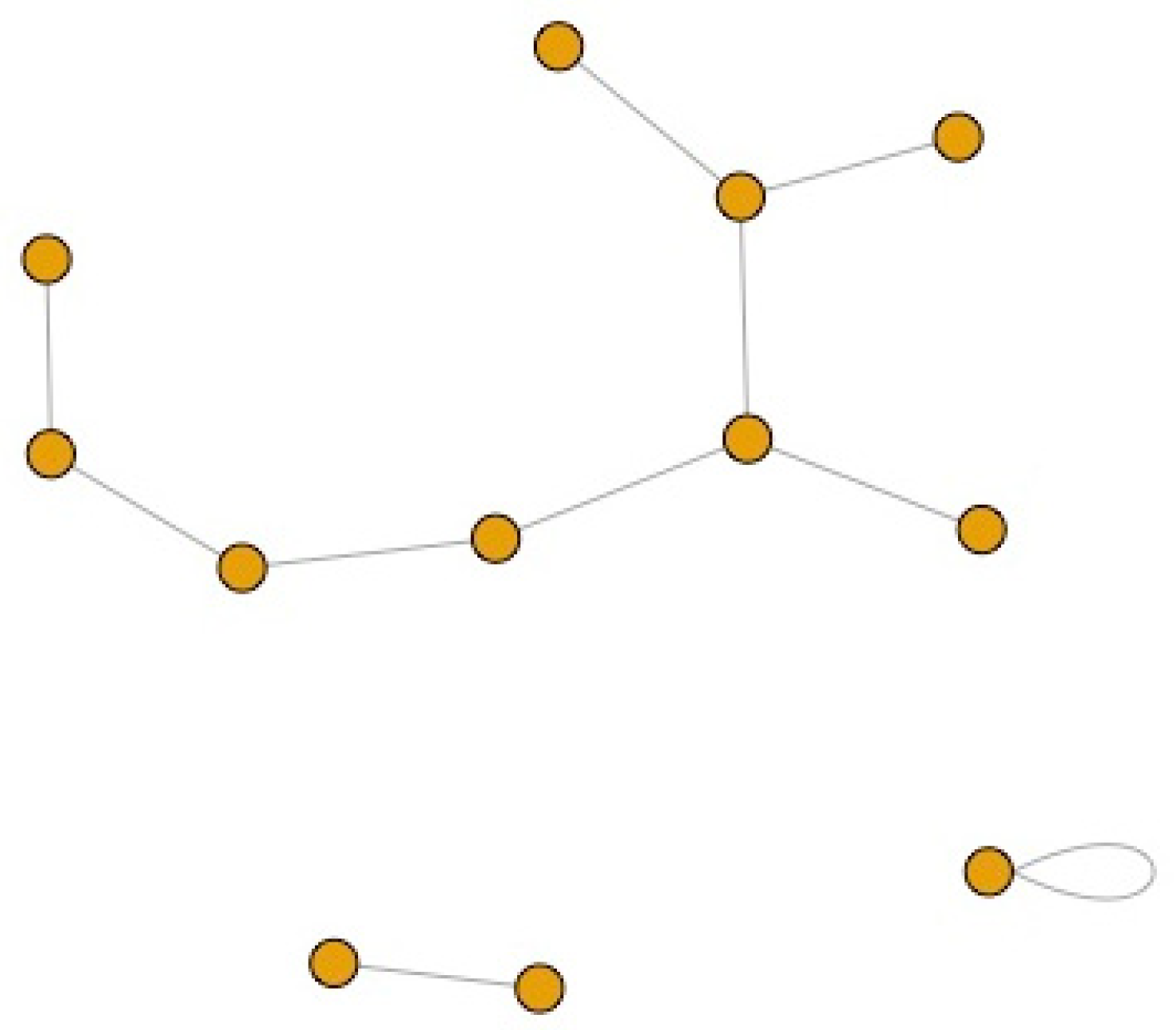

3.2. Visualization of Outputs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raparthi, M.; Gayam, S.R.; Kasaraneni, B.P.; Kondapaka, K.K.; Putha, S.; Pattyam, S.P.; Thuniki, P.; Kuna, S.S.; Nimmagadda, V.S.P.; Sahu, M.K. Harnessing Quantum Computing for Drug Discovery and Molecular Modelling in Precision Medicine: Exploring Its Applications and Implications for Precision Medicine Advancement. 2022.

- Cordier, B.A.; Sawaya, N.P.D.; Guerreschi, G.G.; McWeeney, S.K. Biology and Medicine in the Landscape of Quantum Advantages. J R Soc Interface 2022, 19, 20220541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattad, P.B.; Jain, V. Artificial Intelligence in Modern Medicine - The Evolving Necessity of the Present and Role in Transforming the Future of Medical Care. Cureus 2020, 12, e8041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- London, A.J. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine: Overcoming or Recapitulating Structural Challenges to Improving Patient Care? Cell Rep Med 2022, 3, 100622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mh, S. Understanding the Genetic Code. Journal of bacteriology 2019, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, C.S.; Smoczynski, R.; Tretyn, A. Sequencing Technologies and Genome Sequencing. J Appl Genet 2011, 52, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanis, S.H.; Katsanis, N. Molecular Genetic Testing and the Future of Clinical Genomics. Nat Rev Genet 2013, 14, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan-Pyke, C.; Dokras, A. Preimplantation Genetic Screening and Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2018, 45, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedenthal, J.; Maxwell, S.M.; Munné, S.; Kramer, Y.; McCulloh, D.H.; McCaffrey, C.; Grifo, J.A. Next Generation Sequencing for Preimplantation Genetic Screening Improves Pregnancy Outcomes Compared with Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization in Single Thawed Euploid Embryo Transfer Cycles. Fertil Steril 2018, 109, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, J.L.; Kingsmore, S.; Gelb, B.D.; Vockley, J.; Wigby, K.; Bragg, J.; Stroustrup, A.; Poindexter, B.; Suhrie, K.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Rapid Whole-Genomic Sequencing and a Targeted Neonatal Gene Panel in Infants With a Suspected Genetic Disorder. JAMA 2023, 330, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.M.; Hildreth, A.; Batalov, S.; Ding, Y.; Chowdhury, S.; Watkins, K.; Ellsworth, K.; Camp, B.; Kint, C.I.; Yacoubian, C.; et al. Diagnosis of Genetic Diseases in Seriously Ill Children by Rapid Whole-Genome Sequencing and Automated Phenotyping and Interpretation. Sci Transl Med 2019, 11, eaat6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, U.; Nathany, S.; Sharma, M.; Pasricha, S.; Bansal, A.; Jain, P.; Mehta, A. IHC versus FISH versus NGS to Detect ALK Gene Rearrangement in NSCLC: All Questions Answered? J Clin Pathol 2022, 75, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durant, T.J.S.; Knight, E.; Nelson, B.; Dudgeon, S.; Lee, S.J.; Walliman, D.; Young, H.P.; Ohno-Machado, L.; Schulz, W.L. A Primer for Quantum Computing and Its Applications to Healthcare and Biomedical Research. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2024, 31, 1774–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Xiong, J.; Shi, Y. When Machine Learning Meets Quantum Computers: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, January 29 2021; pp. 593–598.

- Doga, H.; Bose, A.; Sahin, M.E.; Bettencourt-Silva, J.; Pham, A.; Kim, E.; Andress, A.; Saxena, S.; Parida, L.; Robertus, J.L.; et al. How Can Quantum Computing Be Applied in Clinical Trial Design and Optimization? Trends Pharmacol Sci 2024, 45, 880–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraman, N.; Jeyaraman, M.; Yadav, S.; Ramasubramanian, S.; Balaji, S.; Jeyaraman, N.; Jeyaraman, M.; Yadav, S.; Ramasubramanian, S.; Balaji, S. Revolutionizing Healthcare: The Emerging Role of Quantum Computing in Enhancing Medical Technology and Treatment. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Bhattacharya, M.; Dash, S.; Lee, S.-S.; Chakraborty, C. Future Potential of Quantum Computing and Simulations in Biological Science. Mol Biotechnol 2024, 66, 2201–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flöther, F.F. The State of Quantum Computing Applications in Health and Medicine. Research Directions: Quantum Technologies 2023, 1, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, P. The Role of Quantum Mechanics in Cognition-Based Evolution. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2023, 180–181, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravyi, S.; Dial, O.; Gambetta, J.M.; Gil, D.; Nazario, Z. The Future of Quantum Computing with Superconducting Qubits. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 132, 160902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejpasand, M.T.; Sasani Ghamsari, M. Research Trends in Quantum Computers by Focusing on Qubits as Their Building Blocks. Quantum Reports 2023, 5, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Kumar, A.; Singh, H.; Singh, M.; Kaur, K.; Usman, M.; Buyya, R. Quantum Computing: A Taxonomy, Systematic Review and Future Directions. Software: Practice and Experience 2022, 52, 66–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrashed, S.; Min-Allah, N. Quantum Computing Research in Medical Sciences. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 2025, 52, 101606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.C.L. Quantum Computing in Medicine. Med Sci (Basel) 2024, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Liao, J.; Kuang, C.; Li, K.; Liang, W.; Xiong, N. Post-Quantum Security: Opportunities and Challenges. Sensors (Basel) 2023, 23, 8744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyaraman, N.; Jeyaraman, M.; Yadav, S.; Ramasubramanian, S.; Balaji, S. Revolutionizing Healthcare: The Emerging Role of Quantum Computing in Enhancing Medical Technology and Treatment. Cureus 2024, 16, e67486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boev, A.S.; Rakitko, A.S.; Usmanov, S.R.; Kobzeva, A.N.; Popov, I.V.; Ilinsky, V.V.; Kiktenko, E.O.; Fedorov, A.K. Genome Assembly Using Quantum and Quantum-Inspired Annealing. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 13183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Poschenrieder, J.M.; Incudini, M.; Baier, S.; Fritz, A.; Maier, A.; Hartung, M.; Hoffmann, C.; Trummer, N.; Adamowicz, K.; et al. Network Medicine-Based Epistasis Detection in Complex Diseases: Ready for Quantum Computing. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, 10144–10160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| State | Frequency | Decoded sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 101100 | 151 | GTA |

| 010101 | 75 | CTG |

| 110011 | 65 | AGC |

| 001100 | 50 | TAC |

| Gene | Function | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | TBX1 | Cardiovascular and pharyngeal apparatus development |

| 2 | DGCR8 | MicroRNA processing affecting neuronal and immune functions |

| 3 | COMT | Modulation of neurotransmitter systems, particularly dopamine |

| 4 | CLDN | Component of cellular tight junctions, affecting vascular and epithelial integrity |

| 5 | CRKL | Signal transduction involved in neural crest cell development |

| 6 | SNAP29 | Involved in intracellular trafficking |

| 7 | SCARF2 | Plays a role in receptor-mediated endocytosis and antigen presentation |

| 8 | SEPT5 | Involved in cytoskeletal organization and cell division |

| 9 | GP1BB | Involved in platelet production and function |

| 10 | HIRA | Plays a role in chromatin organization and DNA repair |

| 11 | CDC45 | Essential for DNA replication during cell division |

| 12 | SCARF2 | Involved in endocytic recycling and immune response |

| 13 | ZDHHC8 | Involved in palmitoylation, affecting protein sorting and signaling |

| 14 | USH2A | Associated with Usher syndrome and peripheral neuropathy |

| 15 | HIC2 | Regulator of p53-responsive genes, linked to cancer pathways |

| 16 | RTN4R | Involved in neural development and regeneration |

| 17 | SEPT5-GP1BB | Complex gene interplay affecting septin cytoskeleton and platelet function |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).