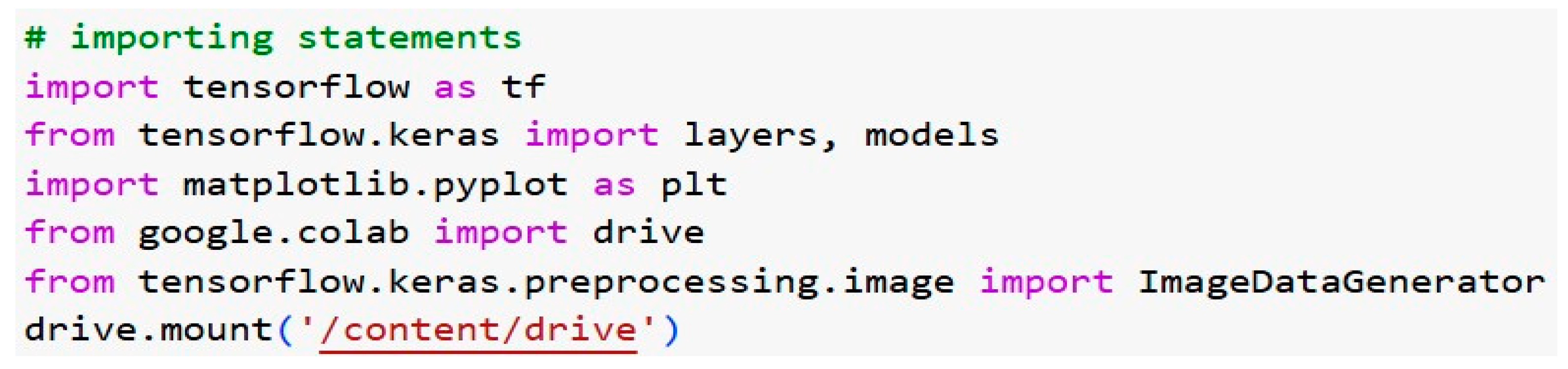

3.2. Data Preprocessing with Augmentation

Data augmentation is an integral part of the deep learning workflow, artificially boosting the number of datasets, principally to mitigate the feel of overfitting while simultaneously enhancing model generalization. Due to the small dataset size of images for the shipping category, transformations including rotation, width and height shift, zoom, and horizontal flipping can harden the model against different realistic variations in the data.

We first create a dataset directory, ‘dataset_dir’, to use later on. Then came the time to deploy the data generator for augmentation of the data. Next, parameters were set, beginning with ‘rescale’-the normalization process. The validation split was then issued at 30% in deviation from an 80/20 rate for the given case, to allow in-depth validation of such data. Finally, the images underwent all kinds of augmentation: rotation, horizontal and vertical shifts, shearing, zooming in, and flipping. To fill in the missing pixels caused by any change to an image an image generator has made, we set a fill mode to stretch the nearest pixel near a gap.

Then training and validation data have been loaded. We used the directory path created earlier to map to our dataset. The image size was kept at 150x150 pixels just enough to take details without being computationally inefficient. The batch is set to 32 because it fits well into a standard GPU memory and had a more stable run without causing the model to break due to RAM overload. The output of the model is in a format where classes belong to categories, hence we set it for classification in categorical mode. Although binary classification would generally have proven very efficient at this point since it is more specialized for binary classes, surprisingly, categorical classification gives an overall better accuracy. For safety, therefore, we went ahead and used this categorical classification. The subset parameter defines whether the code is being run for training or validation.

Dataset Splitting

The dataset has been partitioned into two main subsets: training and testing. This division is essential for assessing the model's capacity to generalize and accurately predict outcomes with previously unseen data. A split ratio of 70% for training and 30% for testing has been selected.

Justification for the Split Ratio

The 70-30 distribution is commonly employed in machine learning, as it strikes a balanced approach that provides ample data for both training and evaluation. The larger portion earmarked for training allows the model to learn from a wide range of examples. Conversely, the test set constitutes 30% of the total data, which is significant enough to yield reliable insights into how the model might perform in actual applications. Additionally, this ratio aids in detecting potential problems such as overfitting or underfitting since performance assessments are conducted on unseen data not utilized during training. Although some literature suggests an alternative 80-20 split (V. Roshan Joseph, 2022), where 80% of data serves as input for training and only 20% acts as a testing subset guided by the Pareto Principle (often referred to as the 80/20 rule), such an arrangement may occasionally fall short when aiming for a nuanced understanding of model performance. The selected 70-30 split embodies a more tailored strategy designed to facilitate deeper and more precise evaluations of model behavior. By allocating one-third of their available data toward testing, models are subject to more stringent scrutiny, thereby enhancing the trustworthiness of evaluation metrics while providing stronger insights regarding their generalization abilities.

3.3. Data Visualization

Verification steps generally include visual inspection of data before model training. The code below retrieves a batch of images and their related one-hot labels from the training set. As output, the screens display a 5 x 5 arrangement of images along with their class label ("ship" or "no-ship"), which is obtained from the one-hot encoded vector. Evidently, as part of the EDA, it is crucial to inspect our data first to check for any anomalies. We set our class names in a list, then load a batch of images along with their labels from the train generator using a next pointer. Then we use matplotlib to create a figure of size 10x10. This will iterate through the list, using 25 images and placing them on a 5x5 plot. The images will increment their index by 1 to make iteration easier. The class names must be reassigned after using labels. The labels are binary in format, so we use argmax to find the maximum value, which is 1. Then we use these labels to index the class names list. The names are assigned back to the variables automatically; no-ship is at the starting zero index and ship at one. The rest of the code is about the figure aesthetics, such as toggling ticks and grids off, and then showing the images in the plot as shown in

Figure 7.

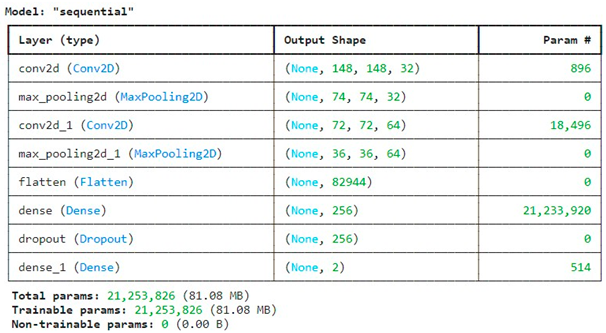

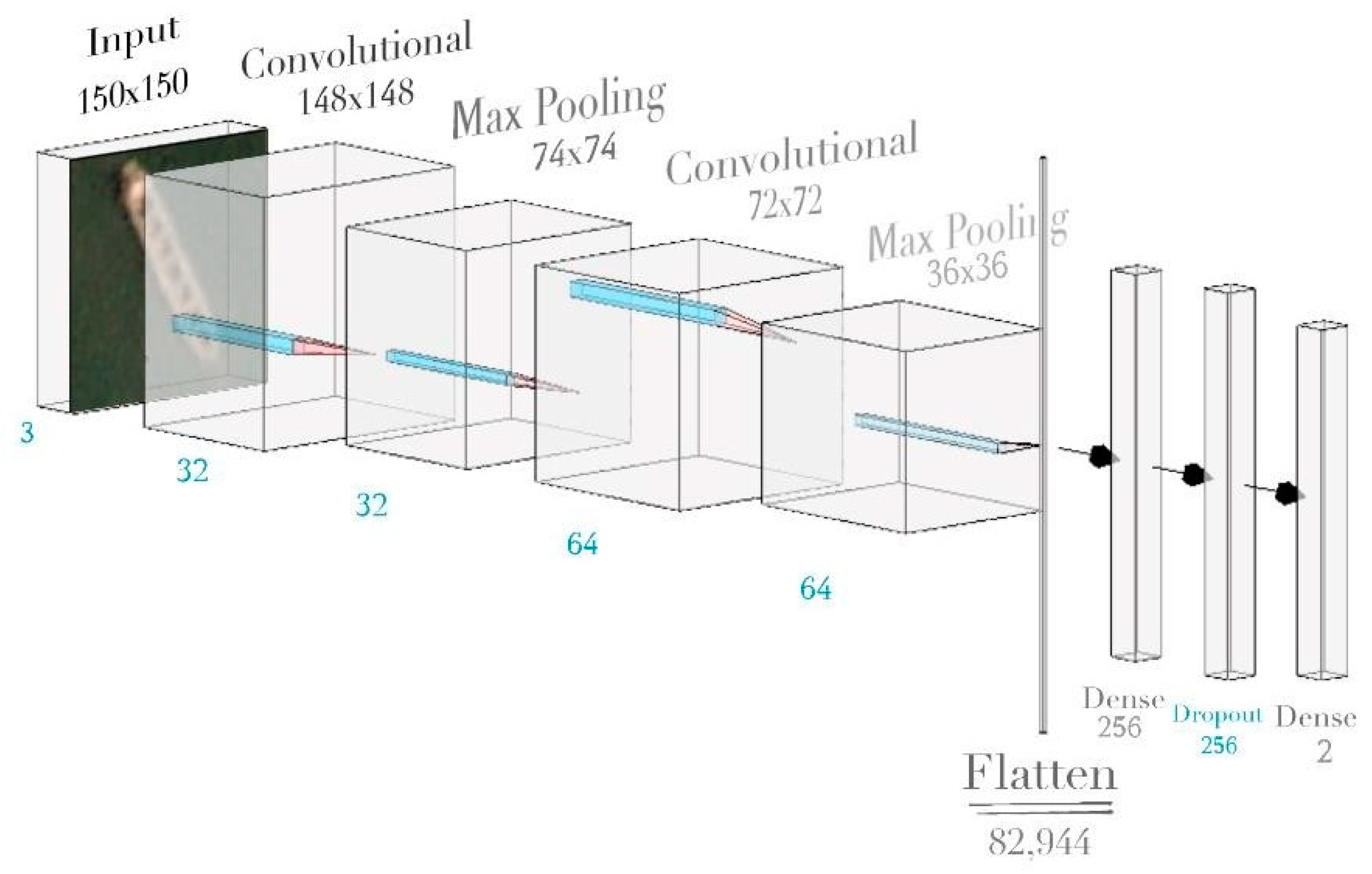

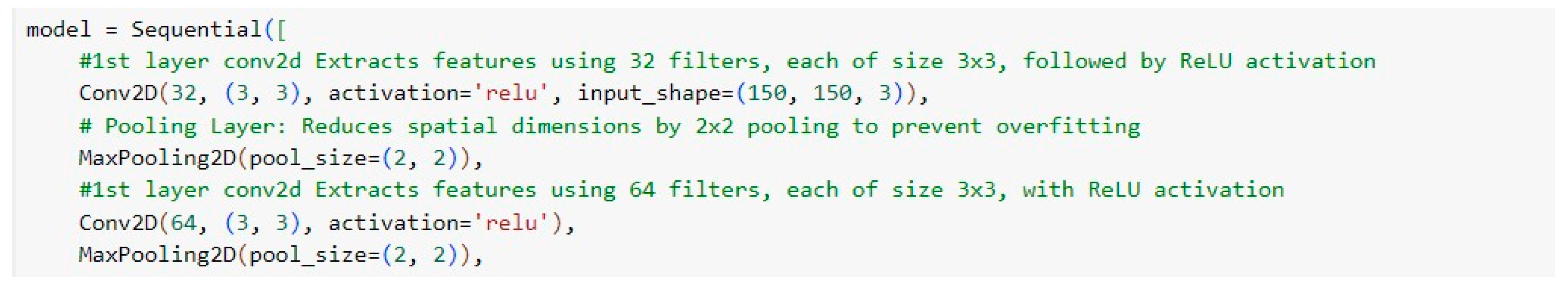

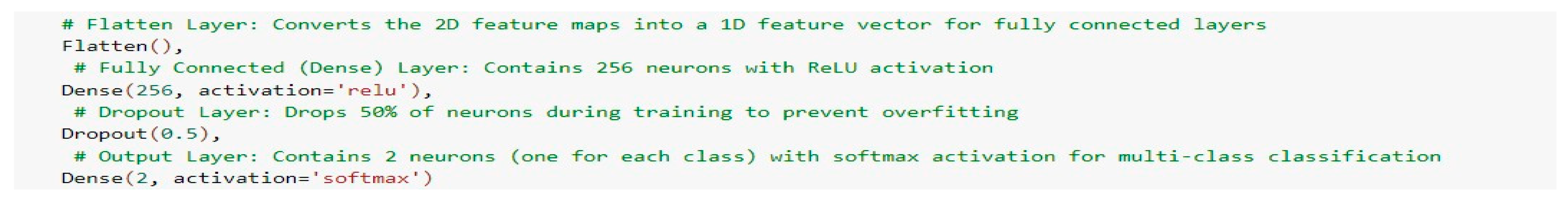

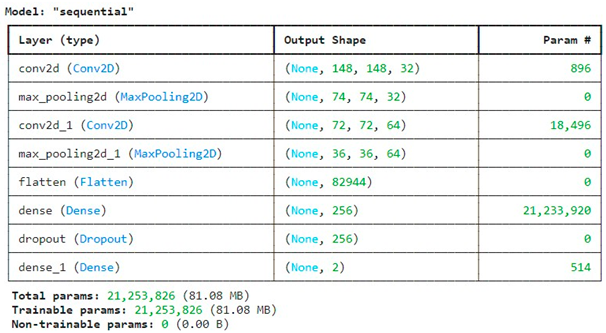

CNN Model Architecture

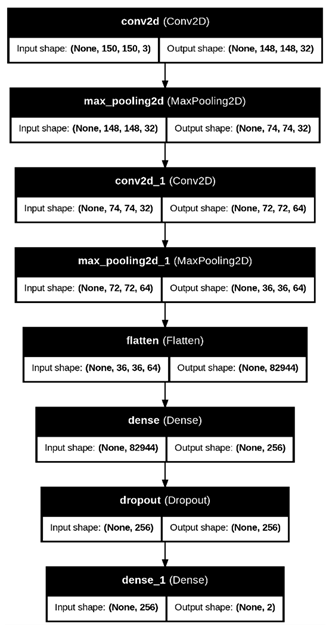

Next addressed is the architecture of the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). The model begins with two convolutional layers, with the max-pooling layers being inserted for feature extraction and dimensionality reduction. The last dense layer provides two outputs, namely ship or no-ship class probabilities, via using the SoftMax activation function. A dropout layer was added to lessen the effects of overfitting. For model architecture, we imported the layers required and then decided to work in sequential mode since models are linear stacks of layers. According to the architecture diagram, we chose the 3x3 kernel for all the convolutional layers, for the first convolutional layer with a depth of 32, to extract simpler features, while the next was at 64 depths for deeper, more complex features. The input image was set to 150x150, since it had 3 RGB colors, after the first conv_2D layer. This 150x150 input is supposed to be used for all layers though the convolutional and the max-pooling ones do change the input size, where the convolutional layer shrinks it down to 148 in one go simply by taking out two pixels from either corner, which is again halved to 74 after max pooling, etc. The max pooling function was used to extract dominant features and reduce spatial dimensions. Since the smaller kernel sizes tend to combat overfitting, we made it into 2x2 for max pooling to fully employ it. To not sound repetitive in this section on architecture, we can go ahead with model compilation. Using the Adam optimizer turned out to be quite effective and robust in comparison with other optimizers, particularly for our datasets with respect to efficiency and learning rates. Later on, binary_crossentropy was selected to cope with training the model with the dichotic classes of ship and no ship. Finally, since machine learning algorithms train for a particular task based on a specific metric, we will define our metric as accuracy, the very parameter we want to measure. Then, we gave the model a summary to see a simple table of our layers along with their information.

Output Snippet: The model summary outputs the number of parameters in each layer, highlighting the complexity of the model. The model consists of over 21 million trainable parameters, indicating a sophisticated network capable of learning intricate patterns from the data.

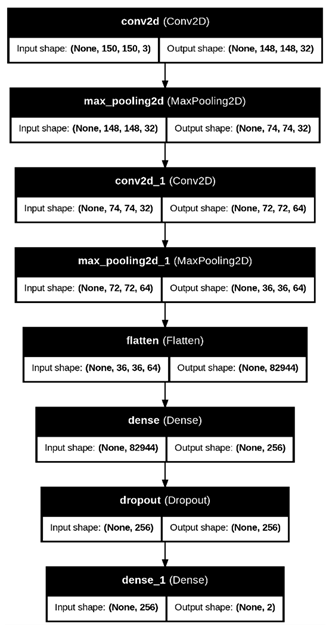

To help us visualize our layers, we also used AlexNet representation for additional insights. We can visualize the model architecture by calling the plot Model function. Set show shapes to True to display input and output for each layer and give a visualization of the dataflow between the layers. True was also set for show_layers_names, which will show the name of each specific layer.

The data flow and the dimensions associated with the input and output shapes are climatically shown along the provided layer names. Note that each output is fed into the subsequent layer. The initial input size was 150 by 150 but becomes 148 by 148 after the Conv layer takes away two pixels, and after that, the max-pooling layers shrink it to half of the input size. This continues until they reach the flattening of pixels into a 1D output. Dense then condenses the data, and Drop removes some neurons to avoid overfitting before the final dense in which the data is condensed into two classes our ship and no-ship class as shown in

Figure 8.

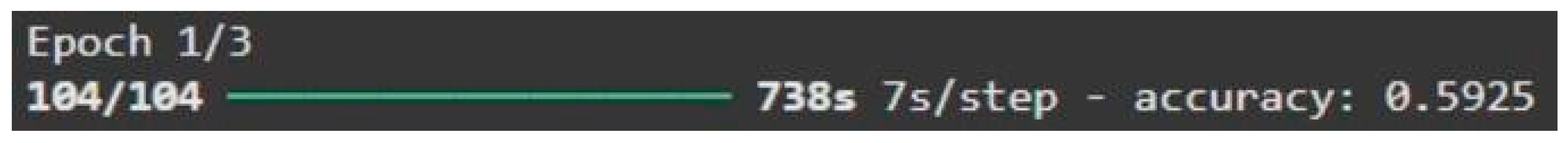

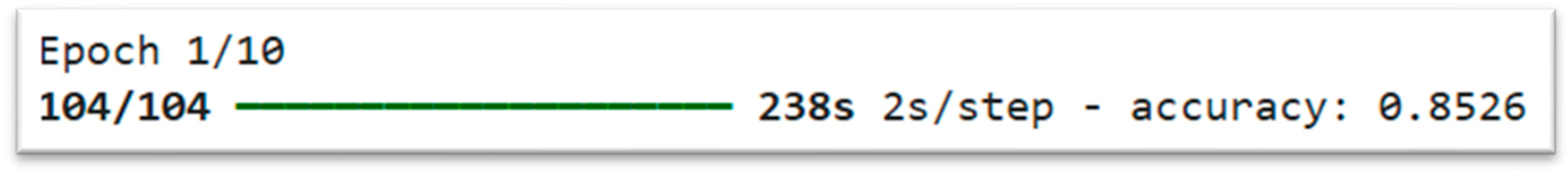

Training the CNN Model:

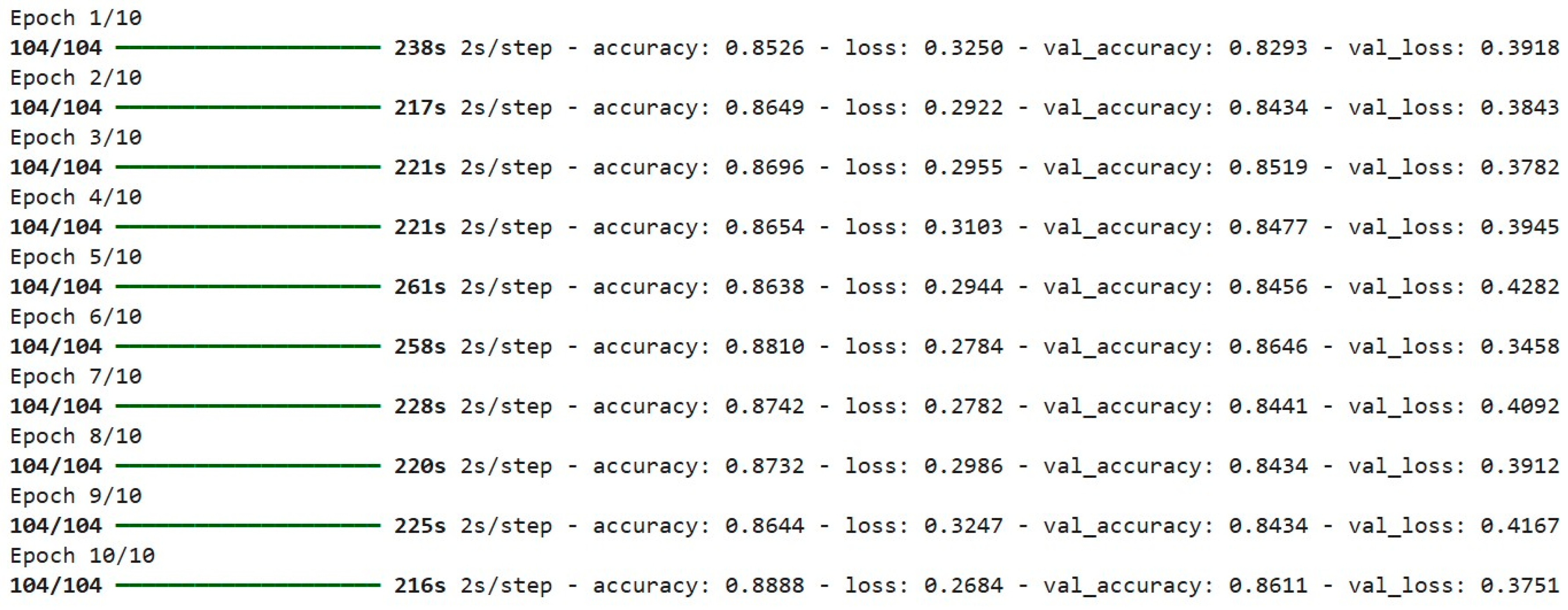

Training of the Neural Network would consist of the repeated handling of the training data and the adjustment of the model weights to minimize the loss function. The model is trained for 10 epochs, which offers a good representation of hyperparameters wherein the model is exposed sufficiently to the data, while the computational cost stays within limits. In training, we provide the training data to the network, and the weights are then adjusted using backpropagation, where the model learns to reduce the error through iterative updates. Validation data, which the model has not encountered during training, was monitored after each epoch for model performance. This information provided a measure of the model's ability to generalize beyond training data.

Performance Evaluation and Visualization

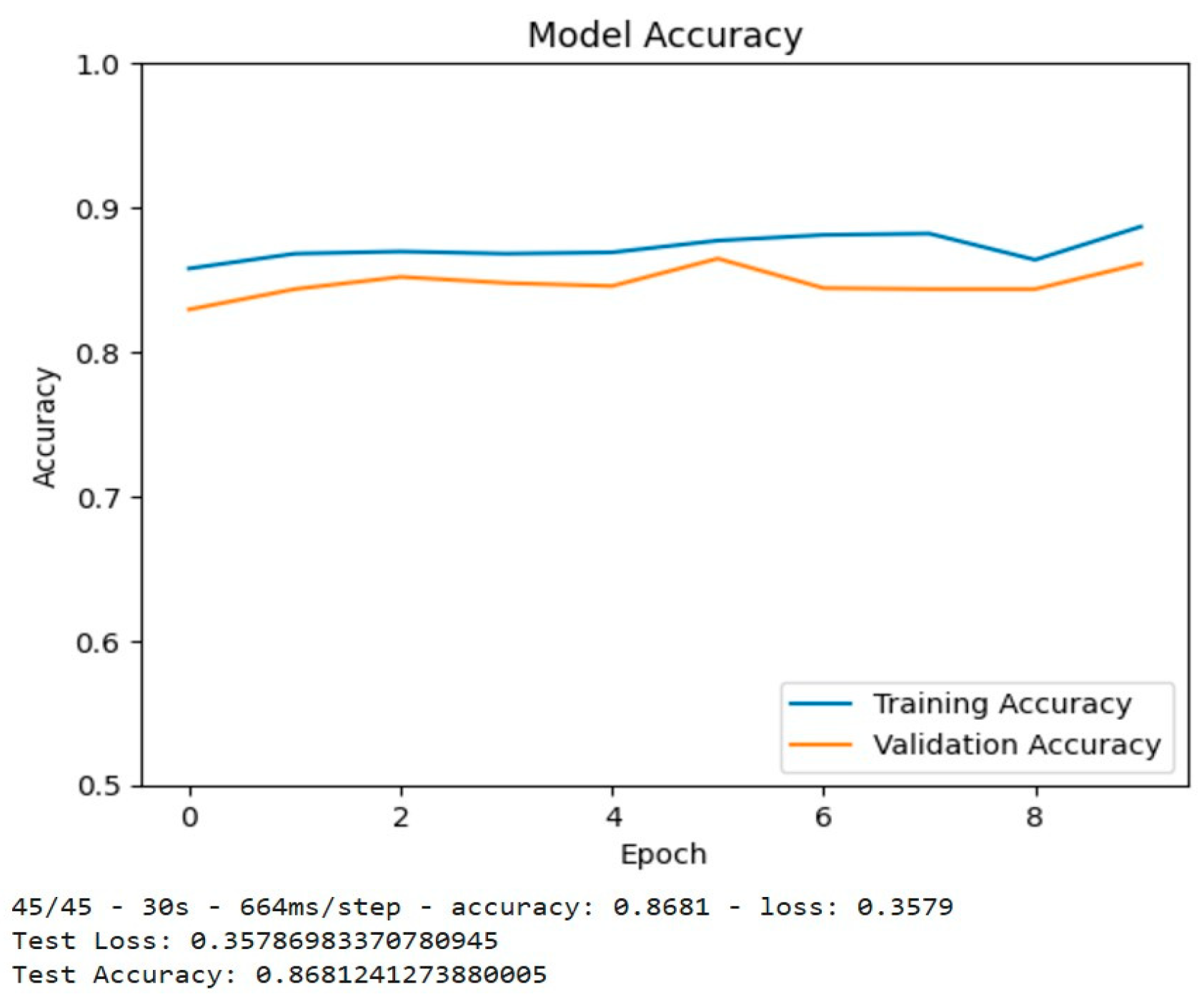

Model Accuracy

At the end of the training procedure, one evaluates the accuracy of the model on the validation dataset, and the training and validation accuracies over epochs are plotted to visualize the learning progress of the model. Subsequently, when testing on the test set, one calculates the test accuracy and loss.

Figure 9 shows the test accuracy of the model at 83.50% shows its effectiveness in distinguishing images of the "ship" and "no ship" classes. In such a case, the performance shows that the model generalized quite well when applied to unseen data.

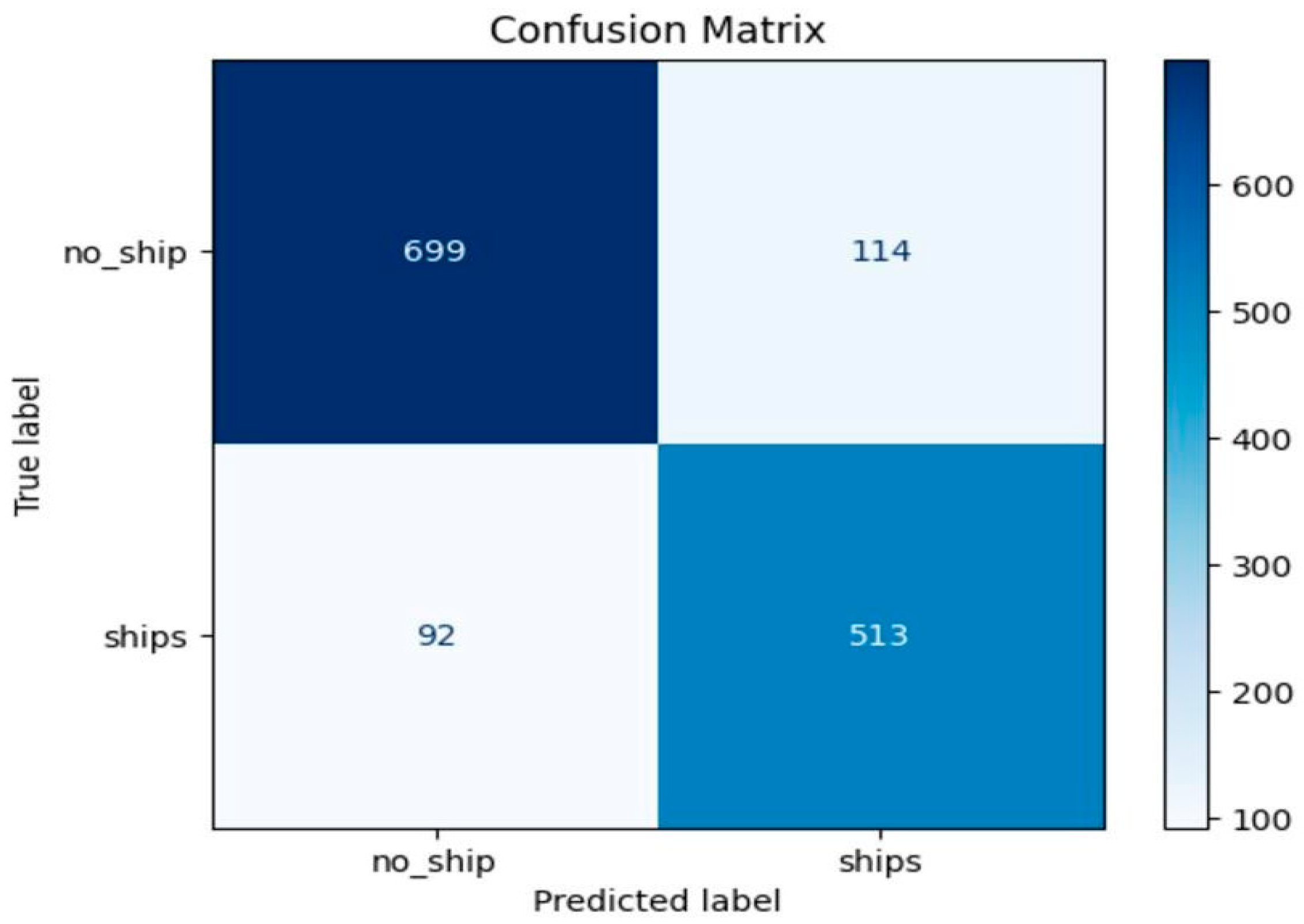

Confusion Matrix and Classification Report

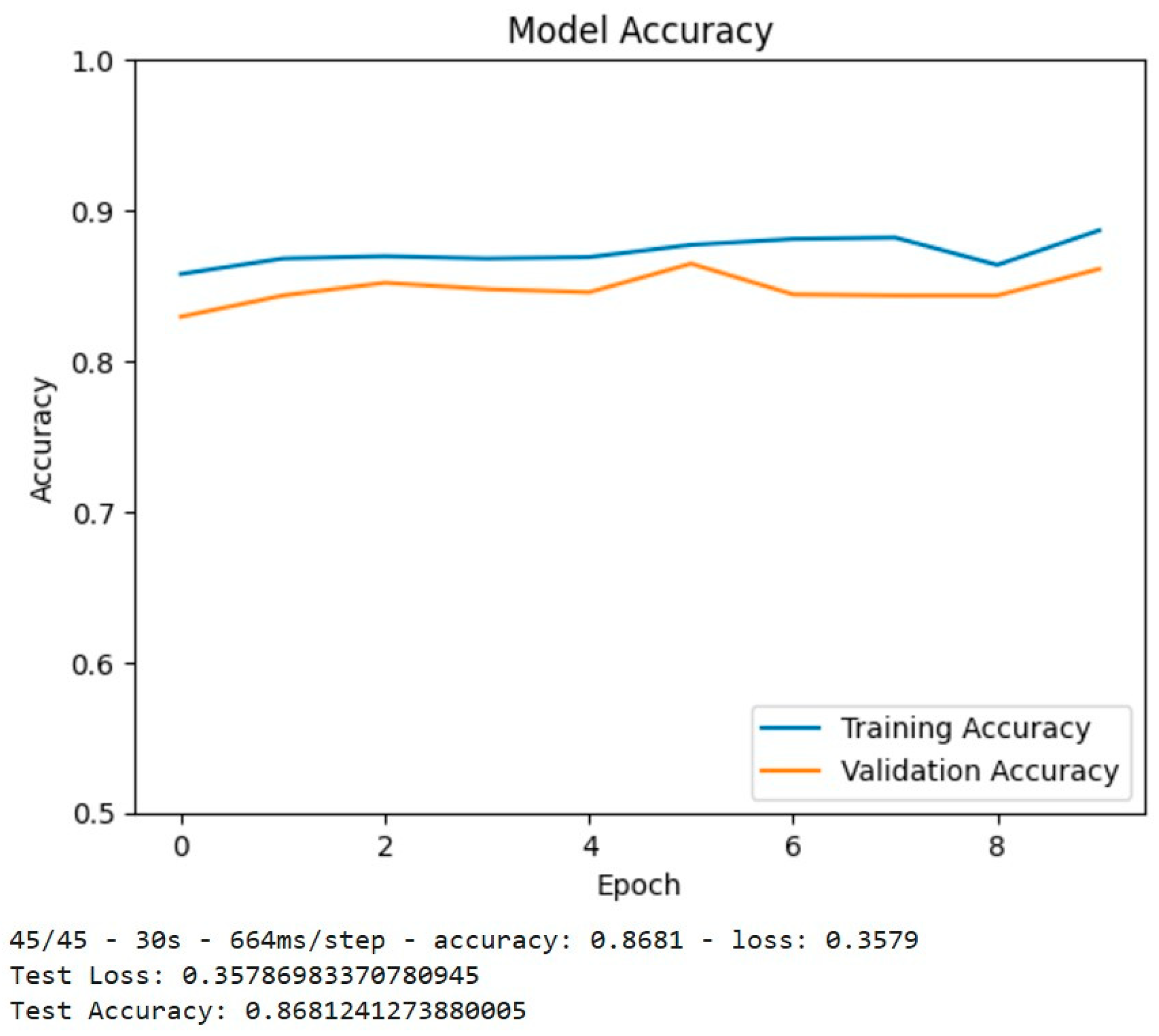

The confusion matrix and classification report further provide insight into the performance of the model. To discuss it in a bit more detail, the confusion matrix serves as an index whereby one observes the true positive, true negative, false positive, and false negative values as to how the model performs for each class. Whereby, the classification report gives the following metrics: precision, recall, and F1-score.

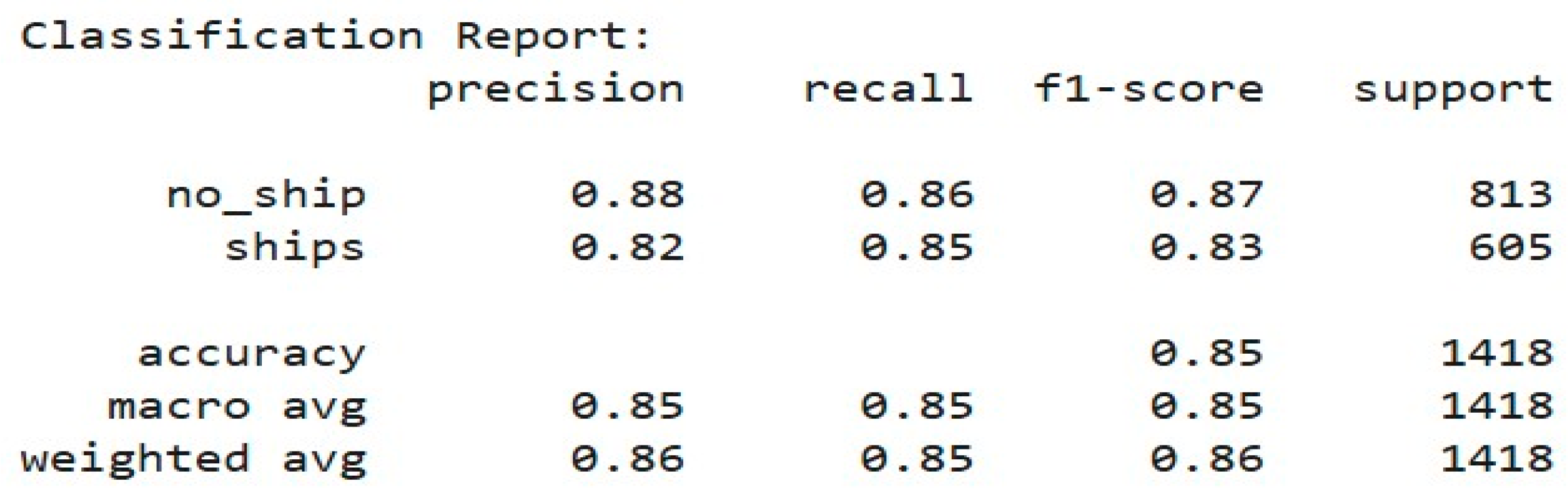

Figure 10 indicates the confusion matrix along with the classification report gives detailed information on how well the model performs for both classes. Precision, recall, and F1-score for each class are given, which shows that the model is slightly better in the precision of the "no-ship" class, while on the other hand, the "ship" class has a relatively lower recall but overall performs well.

Evaluation of Testing Set:

Once training is done, the last step would be to evaluate how the model performs on the testing dataset, a set that it has never seen in its training phase. This is an important step for analysing how well the model generalizes. After testing, the model achieved a test accuracy of around 85%. This score describes the capacity of the model to predict the probability of the presence of a ship or not in test images. Test loss is the difference between the predictions and actual labels. The lesser the test loss, the better it is because that means the predictions of the model are closer to the true labels.

Confusion Matrix and Classification Metrics:

Other evaluation metrics are made, including a confusion matrix and classification report, to have a deeper look into how the model performs. The confusion matrix is a visual representation of the model's predictions, with true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives being highlighted. This matrix can be used to diagnose how well the model is distinguishing between classes. A detailed classification report that gives metrics includes precision, recall, and F1-score. Precision tells how correct the positive predictions are, while recall is how good the model is at detecting positive cases. The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall; thus, it balances the metrics of performance for better evaluation when there are imbalanced classes. For instance, it may provide higher precision for the "no-ship" class, which explains that it is more precise when the prediction is about "no-ship" images. However, the recall of the "ship" class might be slightly less, which means that the model occasionally misses some images of ships but still performs acceptably.

Conclusion

Ship Detection Our aim in this project was to build a CNN model that could detect ships to monitor the oceans more efficiently, thus preventing illegal activities, and providing automated monitoring capability over edges of the manageable aquatic areas. Ship detection was the goal of the fusion of two datasets which has been created to support automatic ship detection. The training-validation metrics were regularly evaluated to facilitate the best possible learning without overfitting. To have learned the intellectual performance of the configuration, additional augmentations and dropout added. As presented, the findings show that the test accuracy stands at 86.5%, which denotes the capability of the model to prove the true classification of the classes’ 'ship' and 'no-ship'. Additional detailed analysis in terms of the classification report and confusion matrix further revealed that the model detected 'no ship' classes more efficiently - which shows corroborating evidence for the greater precision of that class Whereby, this project has successfully applied a CNN model in satellite images for the detection of ships, thereby representing how solving real-world problems is achievable via deep learning techniques. All decisions regarding data augmentation, architecture building, and evaluation methods were carefully defended and critically evaluated. The model is likely to improve further, with more optimizations in the future like hyperparameter optimization or supplying new data, allowing for more sophisticated use in the field of satellite image interpretation.

Challenges Faced

The project was characterized by various challenges that included problems relating to imbalanced data. The class of no ships had images that had a considerable imbalance of having more images than the ships themselves. This led to establishing bias in the model that distorted the outcomes. To mitigate this challenge, we have decided to combine two datasets from Kaggle to balance the ship class. The second issue was the model which suffered from overfitting, in which the validation accuracy surpassed the test accuracy. After many headaches with thorough searching of different literature, this issue was finally conquered by introducing the dropout layer. Then the standard versus exploration dilemma came. Our team was keen on getting the best research of code and standards; however, not every writing on CNN solutions fitted our specific model. That again forced us to develop some time and error techniques for pinpointing the right configurations for our model. Ultimately, we thought our iterative approach helped in overcoming those challenges and improving our model performance to a considerable extent.

Figure 11 shows the model evaluation; we chose accuracy measurement for an overall assessment of test loss. This model seems to generalize well to unseen data. We expect the validation accuracy to be smooth along the train plot with the gist of being inferior. The graph above indicates that while not passing on validation accuracy with a continuous loss of 0.35, the near approximation to training accuracy can suggest the model is functioning well and can adapt to new data at a considerable pace. Hence shortly, of course, this can improve on matching training accuracy, but with a current test accuracy of 86%, a fair part of the data has been identified correctly.

As a result of checking whether or not the model performs well across all classes, the confusion matrix was attached as shown in

Figure 12. The model is doing somewhat decently, giving a higher estimate of true positives and true negatives to compare with a false one, with around 699 and 513 cases correct for the no-ship class and ship cases respectively. However, given that the no-ships class has a larger number overall, about 813 images, in comparison to the total 605 for ship images, this may give rise to some bias. Notwithstanding, this bias was taken care of as much as possible, seeing that the original dataset was skewed, with over 4k images of no-ships against just 2k ships. Our group scaled down the dataset to a more reasonable ratio by adding more ship images. Although still not equal, the confusion matrix certainly certainly has improved on what it used to be at the start of this project.

Lastly, as a feed of overall model performance, we generated a classification report to find key metrics like precision and recall. The scores were 0.87 f1 for no-ship and 0.83 for ship respectively, which highlighted the effectiveness of the model for making competent predictions for each class. However, it suffers from lower recall and greater precision on the no-ship class because this is much of the dataset, and it is more likely to be predicted as positive than to be recalled as negative but vice versa for the ship's class as shown in

Figure 13.

Future Enhancements

While it has worked great for this model, there is still a lot to learn for future work. For instance, one thing learned is the quality of the dataset into which we have collected what we have decided to base on this study the interest of ship detection subject to our effort to solve marine surveillance problems; however, in the future, it should be considered balancing the number of images in the classes of a dataset to avoid biases in the process of training and validation. The other thing would be that, after getting all of that knowledge and experience, some in-depth image preprocessing and cleaning will be a very good consideration beforehand, like histogram equalization for better ship imaging and edge detection for improving shape detection; this will simplify the process of feature extraction into a more efficient model generalization of accuracy. The model may run just fine, but it is sure not ideal. There are quite a few experiences to learn from in the future project. One example of that is the quality of assessment of the data set. The choice made while creating this dataset was based on the subjectivity of interest in ship detection, together with our desire to find solutions to marine surveillance. The best to take on is not forgetting to balance the number of images of classes of the dataset so that no classes are left under or overrepresented during training and validation. Not to mention now with much more expertise and research after this project, it would be a valuable consideration to apply in-depth image processing and cleaning of images beforehand like histogram equalization for better image clarity of ships and edge detection for improving shape detection; thus, making efficient extraction of features much finer and boosting the general accuracy of the model.