Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

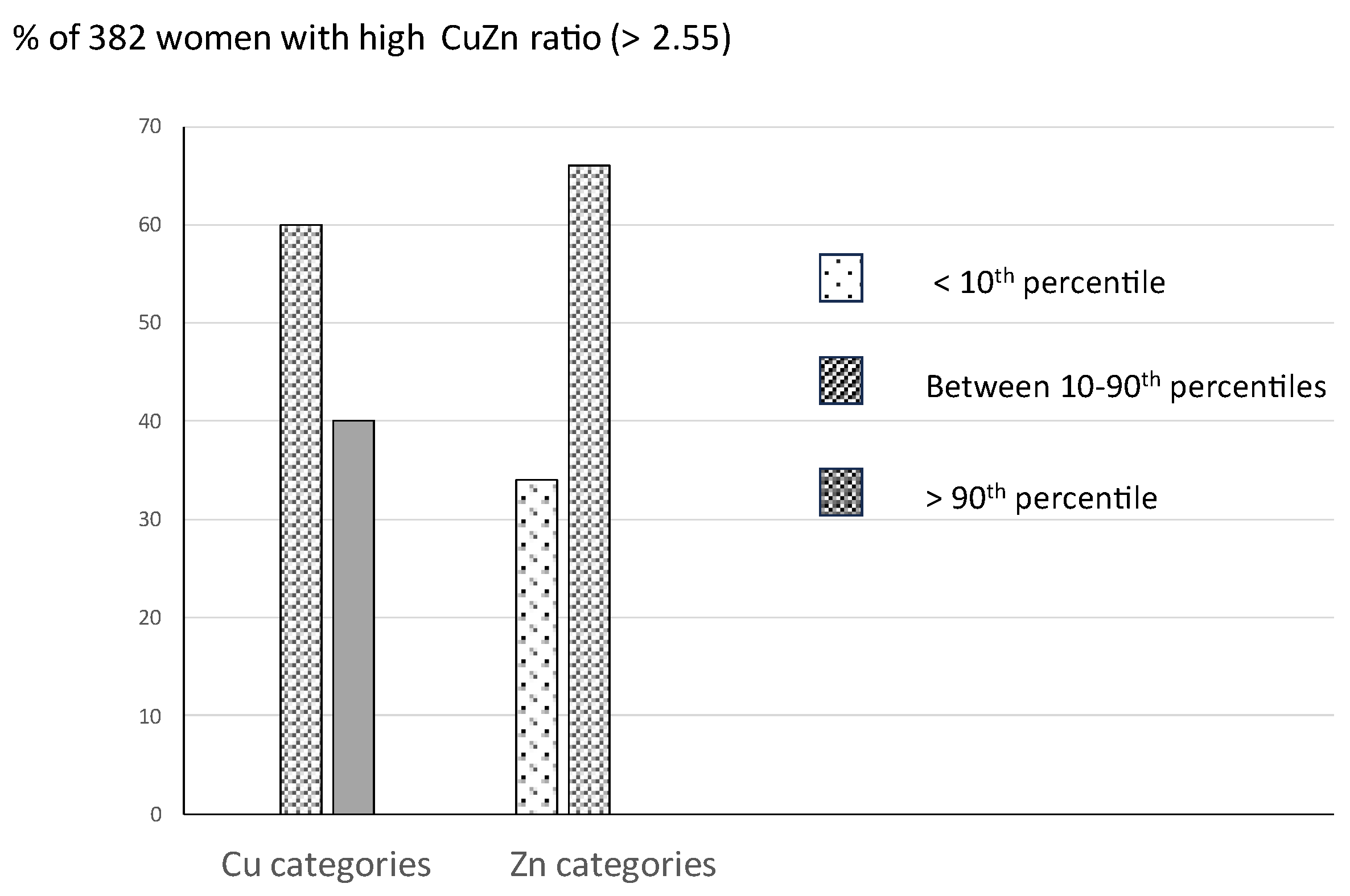

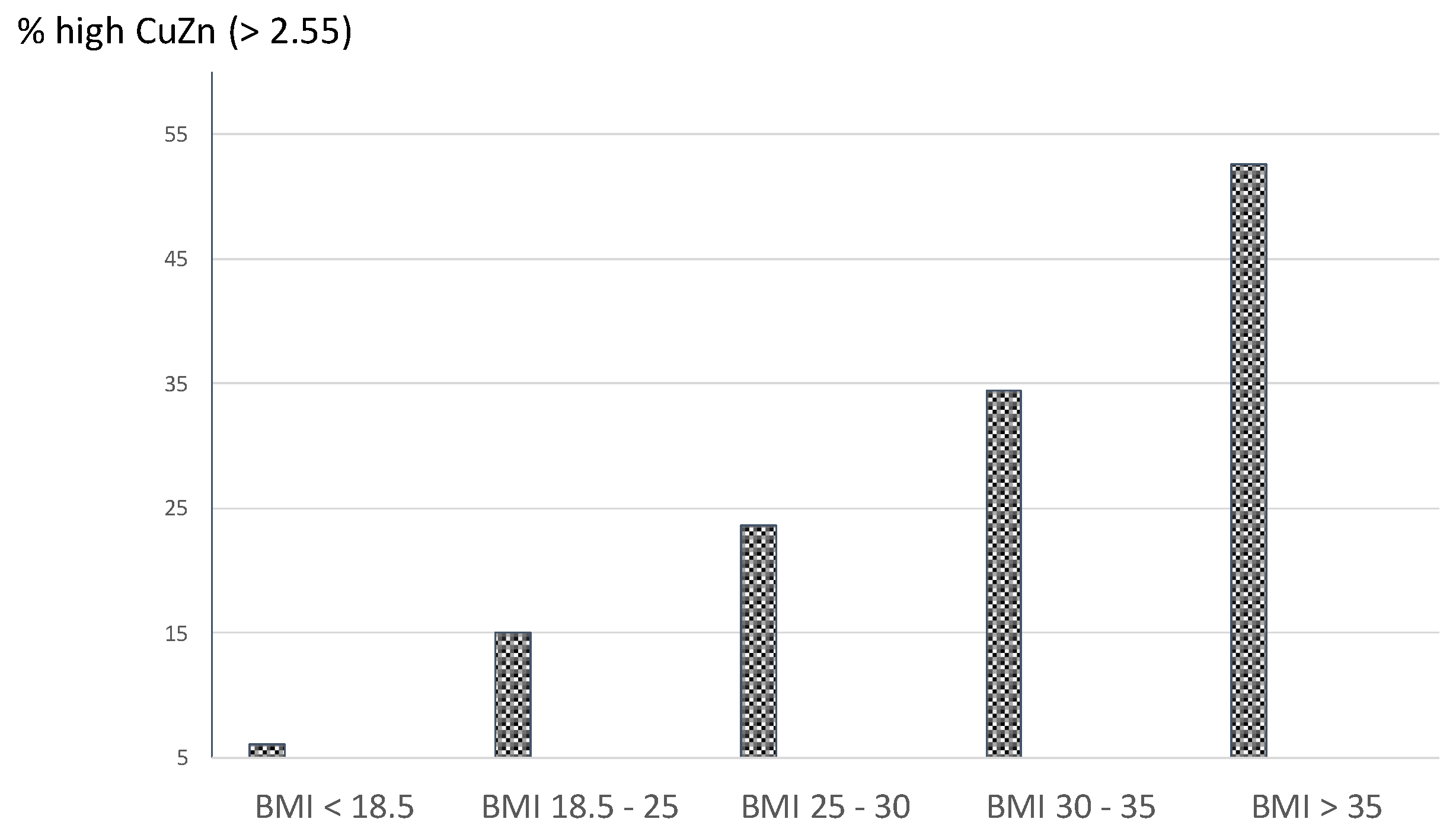

Background / Objectives Pregnancy is a state of increased physiological inflammation. The Cu/Zn ratio in general has been associated with inflammation. The current study evaluated a cut-off of the Cu/Zn ratio taking a high CRP as outcome variable and investigated possible associations between a high Cu/Zn ratio and obstetric complications. Methods Using the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (ROCcurve) technique, an upper cut-off level of the Cu/Zn ratio was evaluated in plasma of 2035 pregnant women with a high CRP (>95th percentile) as outcome test, assessed at 12 weeks of gestation. The occurrence of a high BMI, gestational diabetes (GDM), and high psychological distress in relation to a high Cu/Zn ratio was evaluated using logistic regression analysis (OR; 95% CI). Results ROC analysis showed an area under the curve of 0.81 (95% CI: 0.78 – 0.84) and an upper Cu/Zn ratio cut-off level of 2.55 (sensitivity 64%, specificity 84%). Of the 382 women with a high Cu/Zn ratio, 60-66% showed adequate Cu and Zn levels (between the 10th-90th percentiles). Women with a pre-pregnancy BMI > 30 were three times more likely to present with a high Cu/Zn ratio (OR: 2.97; 95% CI: 2.15-4.13). Compared to 1304 women without any obstetric complication, the 108 women who developed GDM were two times more likely to present with a high Cu/Zn ratio at 12 weeks of gestation (O.R.: 1.9, 95% CI: 1.23 – 3.01). Also, women with a high Cu/Zn ratio were almost twice as likely to report persistently high distress symptom levels throughout gestation (O.R. = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.4-2.6). Conclusions A first trimester high Cu/Zn ratio of 2.55 discerns women at risk for developing GDM and high distress symptom levels throughout gestation.

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Assessments

Copper and Zinc

C-Reactive Protein (CRP)

Statistics

Results

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang Z, Cao J, Chen Y, Dong Y. A novel and compact review on the role of oxidative stress in female reproduction. Reprod Biol Endocrinol (2018); 16(1):80. [CrossRef]

- Konrad Grzeszczak, Natalia Łanocha-Arendarczyk , Witold Malinowski , Paweł Ziętek , Danuta Kosik-Bogacka. Oxidative Stress in Pregnancy. Biomolecules (2023);13(12):1768.

- Tang C, Hu W. The role of Th17 and Treg cells in normal pregnancy and unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion (URSA): New insights into immune mechanisms. Placenta. (2023);142:18-26. [CrossRef]

- Schumacher A, Zenclussen AC. Human Chorionic Gonadotropin-Mediated Immune Responses That Facilitate Embryo Implantation and Placentation. Front Immunol. (2019);10:2896. [CrossRef]

- Aleksandra Vilotić, Mirjana Nacka-Aleksić, Andrea Pirković, et al. IL-6 and IL-8: An Overview of Their Roles in Healthy and Pathological Pregnancies. Int J Mol Sci (2022);23(23):14574. [CrossRef]

- Elenkov IJ. Neurohormonal-cytokine interactions: implications for inflammation, common human diseases and well-being. Neurochem Int. (2008);52(1-2):40-51. [CrossRef]

- Joo EH, Kim YR, Kim N, et al. Jung JE, Han SH, Cho HY. Effect of Endogenic and Exogenic Oxidative Stress Triggers on Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: Preeclampsia, Fetal Growth Restriction, Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Preterm Birth. Int J Mol Sci. (2020);22(18):10122. [CrossRef]

- Grzeszczak K, Kwiatkowski S, Kosik-Bogacka D. The Role of Fe, Zn, and Cu in Pregnancy. Biomolecules (2020);10(8):1176.

- Maret W. The redox biology of redox-inert zinc ions. Free Radic Biol Med (2019);134:311-326. [CrossRef]

- Ceylan MN, Akdas S, Yazihan N. The Effects of Zinc Supplementation on C-Reactive Protein and Inflammatory Cytokines: A Meta-Analysis and Systematical Review. J Interferon Cytokine Res. (2021);41(3):81-101. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova ID, Pal A, Simonelli I, Atanasova B, Ventriglia M, Rongioletti M, Squitti R. Evaluation of zinc, copper, and Cu:Zn ratio in serum, and their implications in the course of COVID-19. J Trace Elem Med Biol. (2022); 71:126944. [CrossRef]

- Lihua Guan, Yifei Wang, Liling Lin, Yutong Zou, Ling Qiu. Variations in Blood Copper and Possible Mechanisms During Pregnancy. Biological Trace Element Research (2024) 202:429–441. [CrossRef]

- Masashi Kitazawa, Heng-Wei Hsu, Rodrigo Medeiros, Copper Exposure Perturbs Brain Inflammatory Responses and Impairs Clearance of Amyloid-Beta, Toxicological Sciences. (2016); 152:1,194–204. [CrossRef]

- Marlene Fabiola Escobedo-Monge , Enrique Barrado, Joaquín Parodi-Román, María Antonieta Escobedo-Monge, María Carmen Torres-Hinojal, José Manuel Marugán-Miguelsanz. Copper/Zinc Ratio in Childhood and Adolescence: A Review. Metabolites (2023);13(1):82. [CrossRef]

- Joshi A, Mandal R. Review Article on Molecular Basis of Zinc and Copper Interactions in Cancer Physiology. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Vincent HK, Taylor AG. Biomarkers and potential mechanisms of obesity-induced oxidant stress in humans. Int J Obes (Lond) (2006);30:400–418. [CrossRef]

- Pallavi Dubey, Vikram Thakur, Munmun Chattopadhyay. Role of Minerals and Trace Elements in Diabetes and Insulin Resistance. Nutrients. (2020) ;12(6):1864. [CrossRef]

- Looman M, Geelen A, Samlal RA, et al.: Changes in micronutrient intake and status, diet quality and glucose tolerance from preconception to the second trimester of pregnancy. Nutrients. (2019); 11(2): 460. [CrossRef]

- Paulo MS, Abdo NM, Bettencourt-Silva R, Al-Rifai RH. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prevalence Studies. Front Endocrinol (2021);12:691033. [CrossRef]

- Qiu Q, Zhang F, Zhu W, Wu J, Liang M. Copper in Diabetes Mellitus: a Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Plasma and Serum Studies. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2017);177(1):53-63. [CrossRef]

- Li P, Yin J, Zhu Y, et al.: Association between plasma concentration of copper and gestational diabetes mellitus. Clin. Nutr. (2019); 38(6): 2922–2927. [CrossRef]

- Dennis CL, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry (2017);210:315–23. [CrossRef]

- Dohrenwend BP, Shrout PE, Egri G, Mendelsohn FS. Nonspecific psychological distress and other dimensions of psychopathology. Measures for use in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry (1980);37:1229–36. [CrossRef]

- Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2010);67:1012–24. [CrossRef]

- Lianne P. Hulsbosch, Myrthe G.B.M. Boekhorst, Frederieke A.J. Gigase, Maarten A.C. Broeren, Johannes G. Krabbe, Wolfgang Maret, Victor J.M. Pop. The first trimester plasma copper_zinc ratio is independently related to pregnancy-specific psychological distress symptoms throughout Pregnancy. Nutrition (2023); 109: 111938. [CrossRef]

- Truijens SE, Meems M, Kuppens SM, Broeren MA, Nabbe KC, Wijnen HA, et al. The HAPPY study (Holistic Approach to Pregnancy and the first Postpartum Year): design of a large prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth (2014);14:312. [CrossRef]

- Bergink V, Kooistra L, Lambregtse-van den Berg MP, Wijnen H, Bunevicius R, van Baar A, et al. Validation of the Edinburgh Depression Scale during pregnancy. J Psychosom Res. (2011);70(4):385-9. [CrossRef]

- Pop VJ, Pommer AM, Pop-Purceleanu M, Wijnen HA, Bergink V, Pouwer F. Development of the Tilburg Pregnancy Distress Scale: the TPDS. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth (2011);11:80. [CrossRef]

- Victor J M Pop, Johannes G Krabbe, Maarten Broeren,et al. Hypothyroxinaemia during gestation is associated with low ferritin and increased levels of inflammatory markers. Eur Thyroid J (2024);13(2):e230163.

- Ozarda Y, Sikaris K, Streichert T, Macri J. Distinguishing reference intervals and clinical decision limits—a review by the IFCC committee on reference intervals and decision limits. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. (2018);55:420-431. [CrossRef]

- Knottnerus JA, Buntinx F. The Evidence Base of Clinical Diagnosis: Theory and Methods of Diagnostic Research. 2nd ed. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell BMJ Books; (2009).

- Field, A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Page 698-699. Sage publications limited, 3th Edition (2009).

- Jaakko T Laine, Tomi-Pekka Tuomainen, Jukka T Salonen, Jyrki K Virtanen. Serum copper-to-zinc-ratio and risk of incident infection in men: the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Eur J Epidemiol. (2020); (12):1149-1156. [CrossRef]

- Yang M, Li Y, Yao C, Wang Y, Yan C Association between serum copper-zinc ratio and respiratory tract infection in children and adolescents. PLoS One (2023);18(11):e0293836.

- Huang, D., Lai, S., Zhong, S. et al. Association between serum copper, zinc, and selenium concentrations and depressive symptoms in the US adult population, NHANES (2011–2016). BMC Psychiatry (2023); 23, 498. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Song W, Zhang W. The emerging role of copper in depression. Front Neurosci. (2023);17:1230404. [CrossRef]

- Huidi Zhang, Yang Cao, Qingqing Man, Yuqian Li, Jiaxi Lu, Lichen Yang. Study on Reference Range of Zinc, Copper and Copper/Zinc Ratio in Childbearing Women of China. Nutrients (2021); 13(3): 946. [CrossRef]

- Perined data. National Dutch Birth Outcome data 2020, www.perined.nl.

- Kurlak, LO, Scaife, PJ, Briggs, LV, Broughton Pipkin, F, Gardner, DS, Mistry, HD. Alterations in Antioxidant Micronutrient Concentrations in Placental Tissue, Maternal Blood and Urine and the Fetal Circulation in Pre-eclampsia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. (2023), 24, 3579. [CrossRef]

- Central Office of Statistics 2021, www.cbs.nl.

| Mean (SD) | N (%) | median / range | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic features | |||||

| Caucasian | 2015 (99) | ||||

| Age (in years) | 30.5 (3.5) | ||||

| Educational level | |||||

| Low | 576 (28.3) | ||||

| Medium | 114 (5.6) | ||||

| High* | 1345 (66.1) | ||||

| Marital status | |||||

| With partner | 1925 (94.6) | ||||

| Single | 110 (5.4) | ||||

| Obstetric features | |||||

| Primipara’s | 999 (49.1) | ||||

| Multipara’s | 1036 (51.9) | ||||

| Previous miscarriage | 507 (24.9) | ||||

| Lifestyle habits during pregnancy | |||||

| Smoking | 126 (6.2) | ||||

| Any alcohol intake | 73 (3.6) | ||||

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | 23.8 (3.7) | ||||

| BMI < 18.5 | 66 (3.2) | ||||

| BMI 18.5 – 25 | 1319 (64.8) | ||||

| BMI 25 – 30 | 470 (23.1) | ||||

| BMI 30 – 35 | 142 (7.0) | ||||

| BMI > 35 | 38 (1.9) | ||||

| Biological parameters | |||||

| Zinc µmol/L Copper µmol/L Cu / Zn ratio |

12.56 (1.80) 26.26 (4.74) 2.13 (0.5) |

12.44 (7.51 – 20.94) 25.9 (12.85 – 47.84) 2.09 (0.98 – 4.0) |

|||

| CRP mg / L CRP>95thpercentile (>15mg/L) |

110 (5.4) |

3.7 (0.11 - 49) |

|||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).