Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants and Ethical Approval

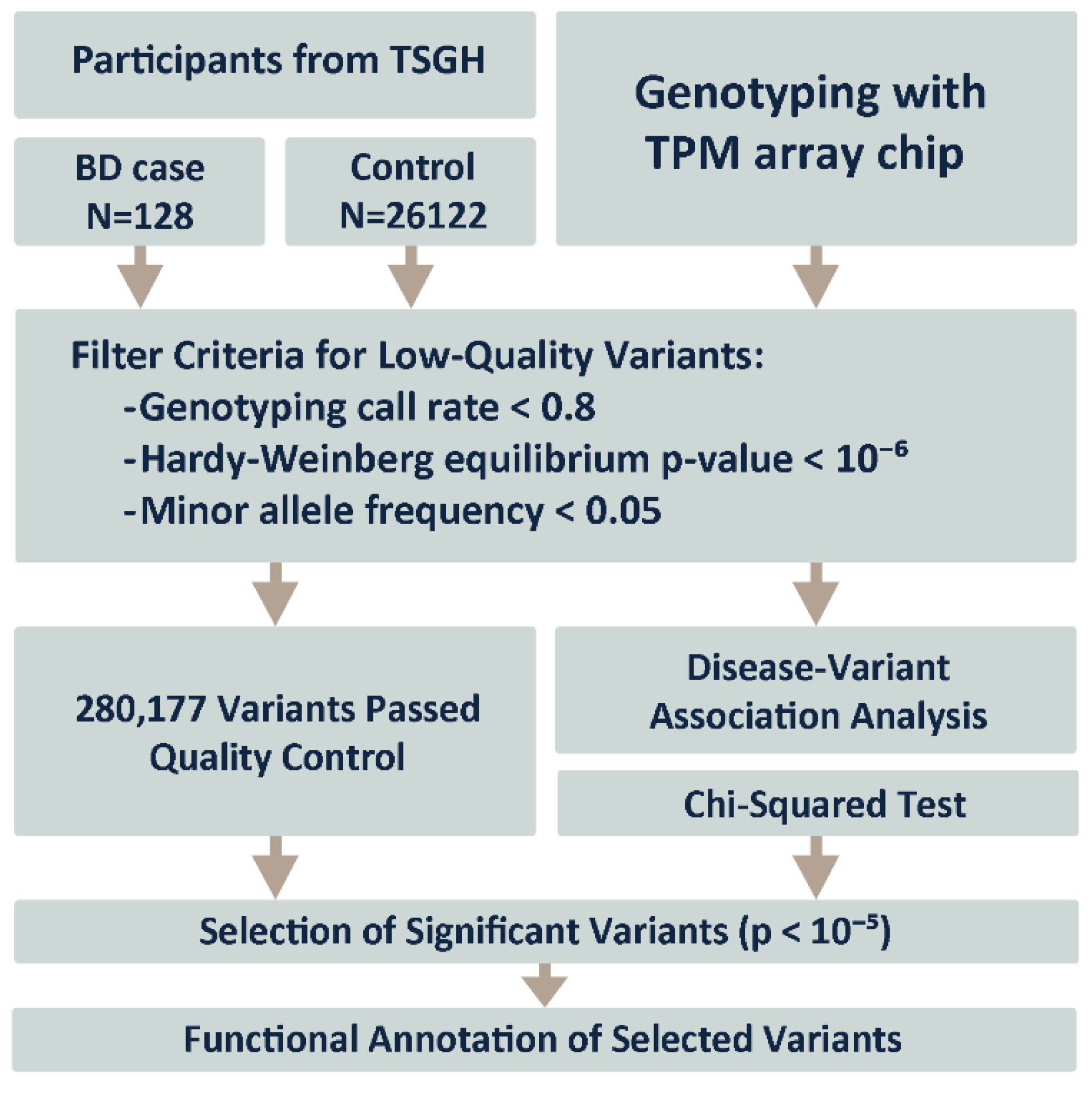

2.2. Disease Association Analysis

2.3. Variant Annotations and Functional Analysis

2.4. Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics of the Selected Patients

3.2. Study Workflow

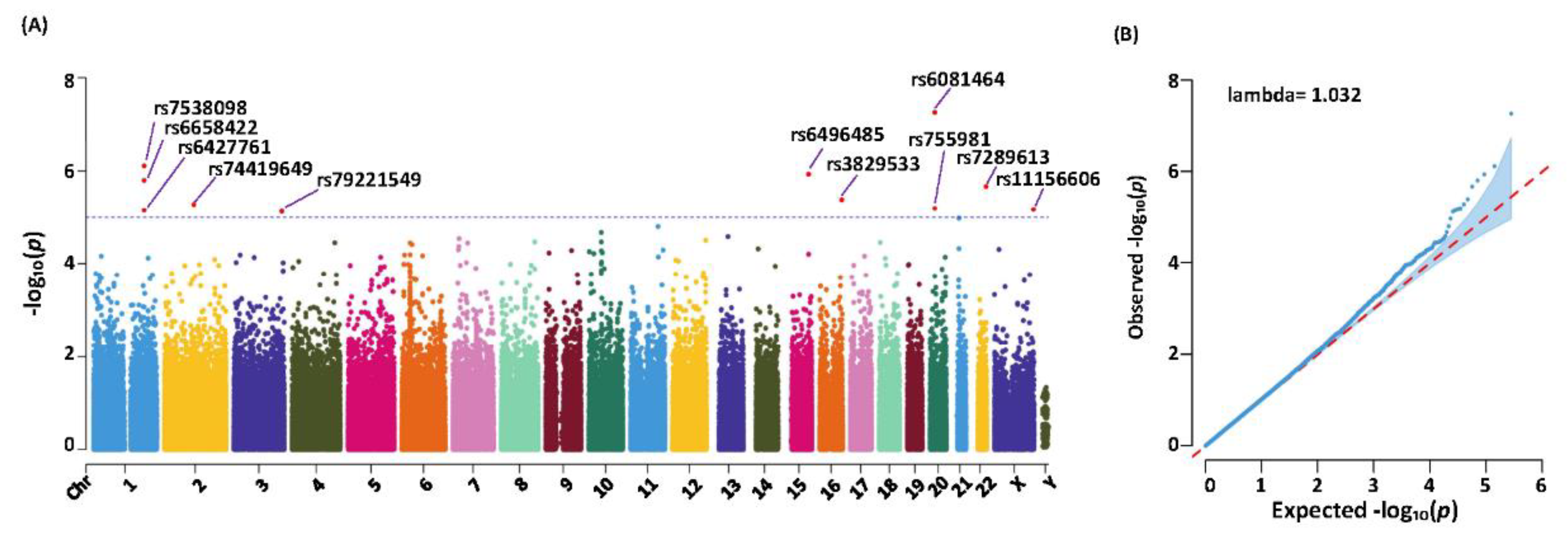

3.3. Genetic Variants Identified, Statistical Analysis and Significance

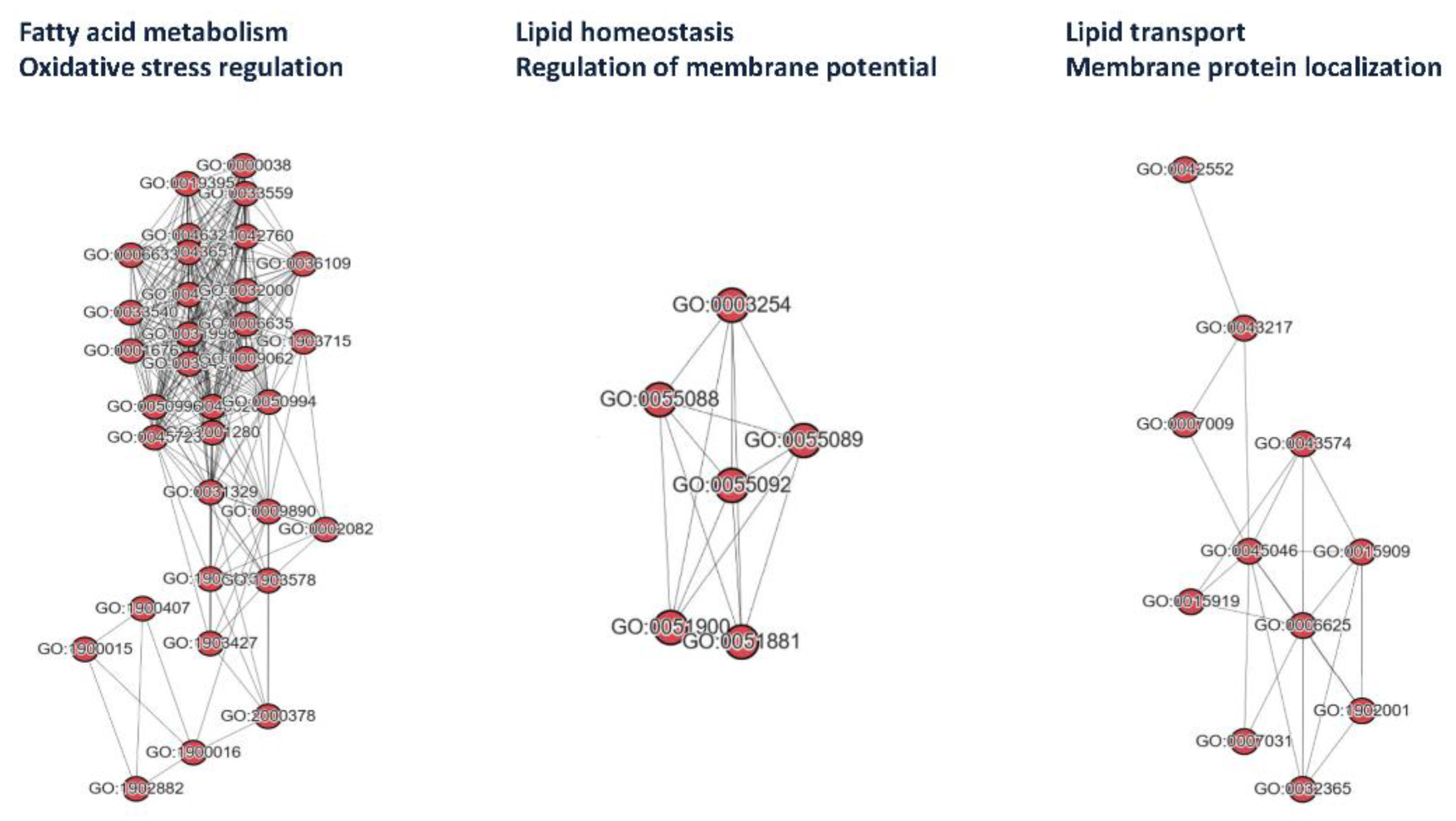

3.4. Functional Annotations of Risk Genes

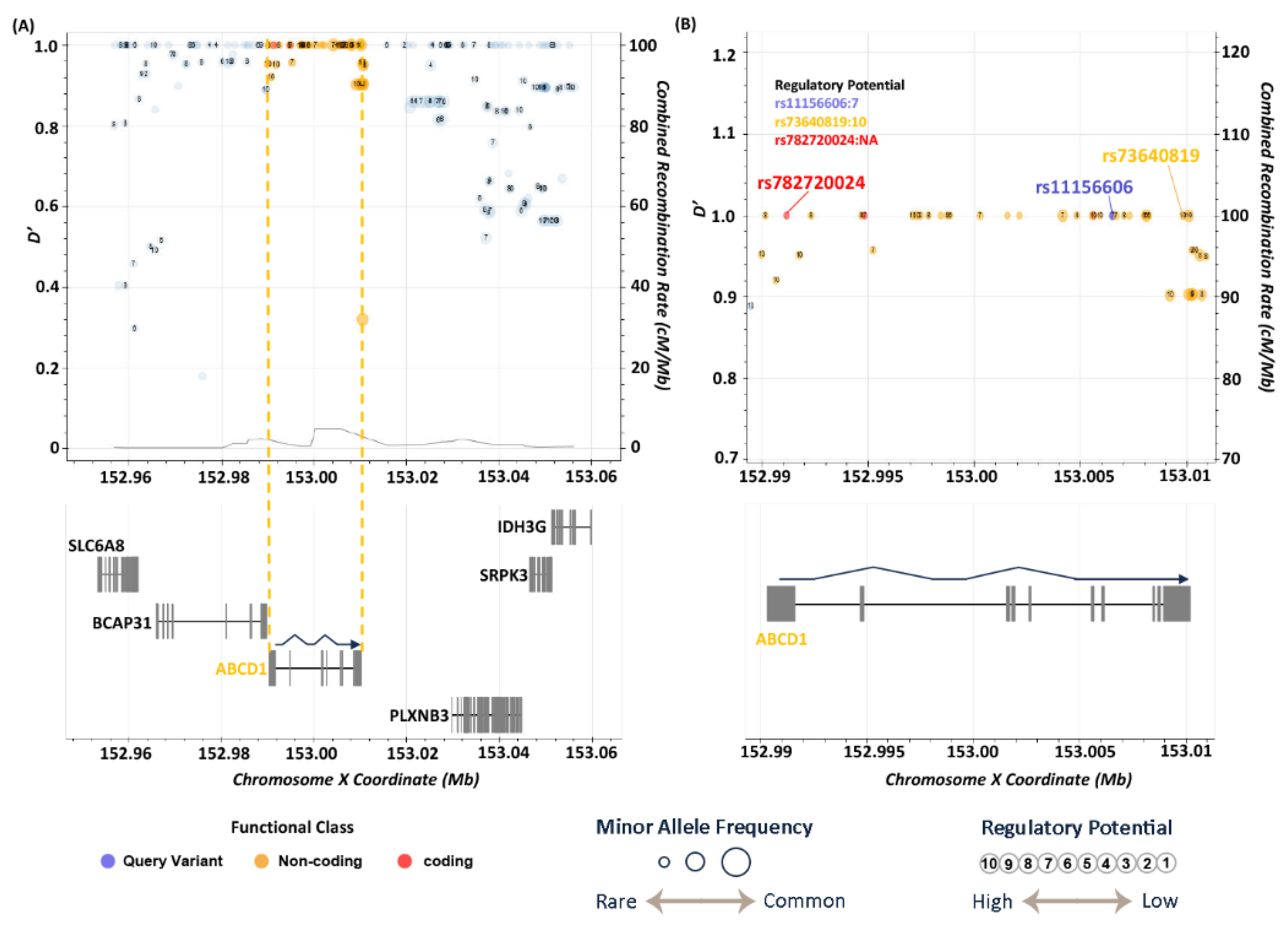

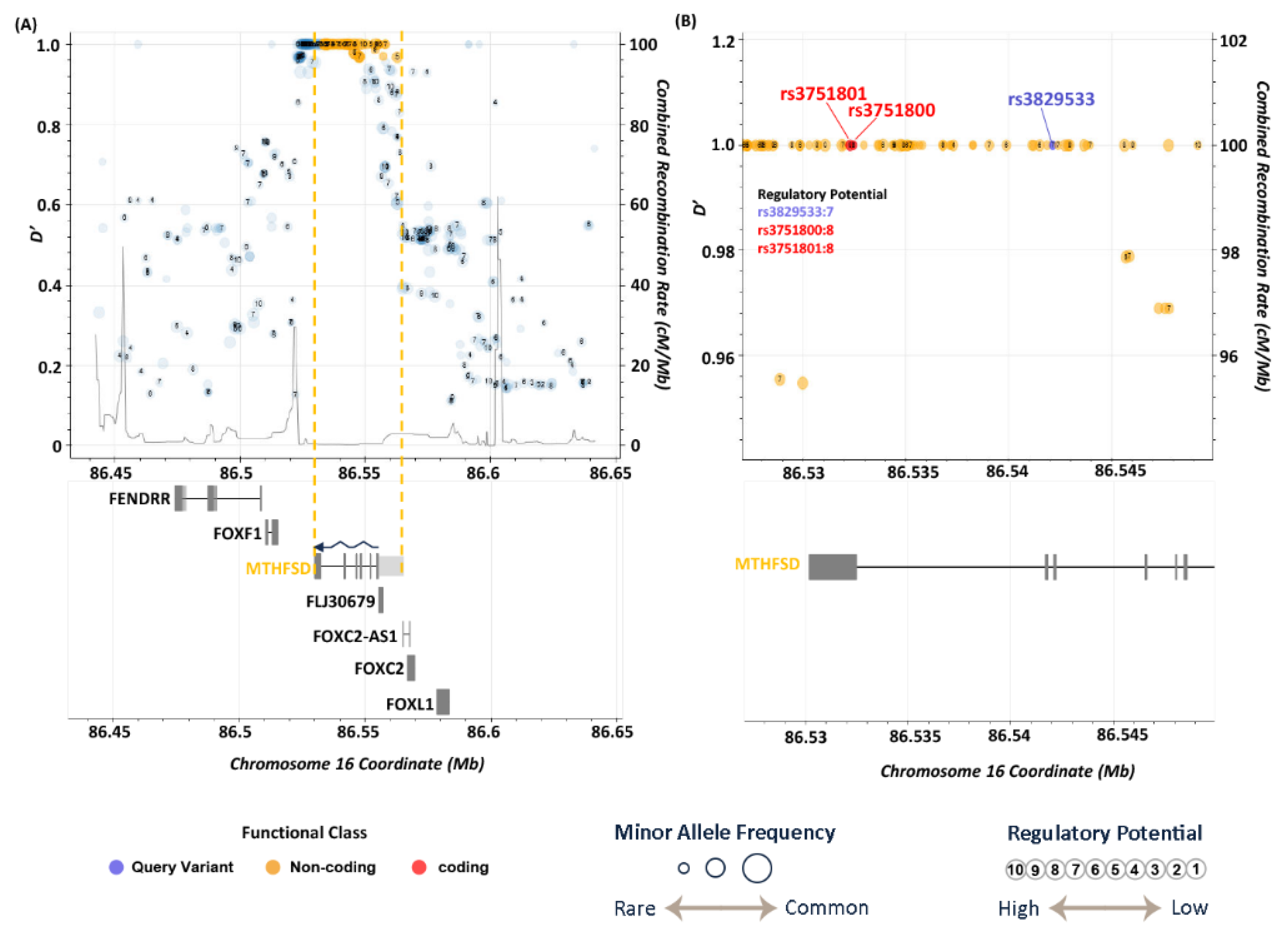

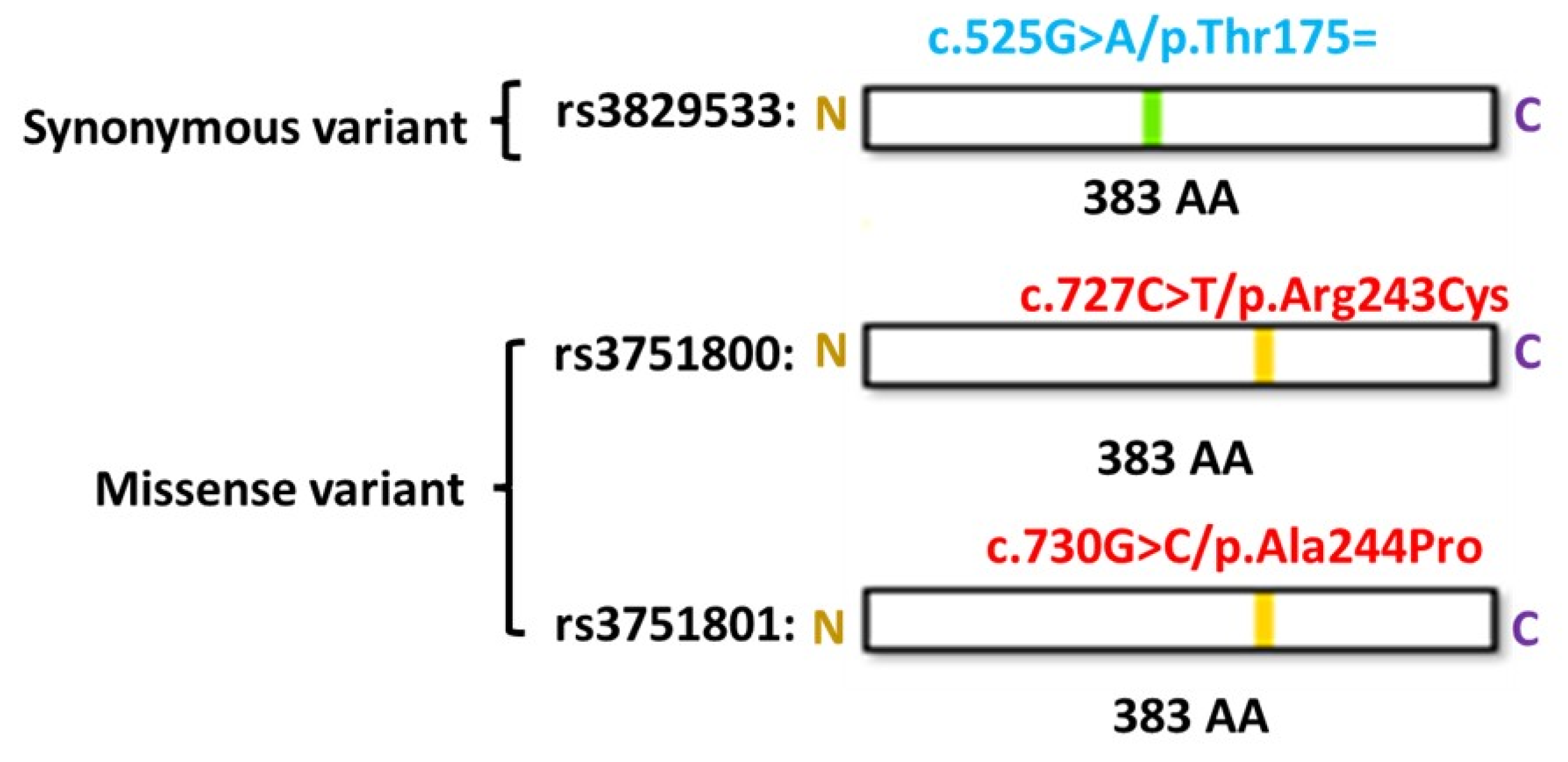

3.5. LD Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APA | Polyadenylation |

| BD | Bipolar Disorder |

| DALYs | Disability-Adjusted Life Years |

| DSM | The Diagnostic And Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| DSM-5 | DSM, Fifth Edition |

| EPA | Omega-3 Eicosapentaenoic Acid |

| GWAS | Genome-Wide Association Studies |

| ICD | The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems |

| LD | Linkage Disequilibrium |

| MAP | Methamphetamine-Associated Psychosis |

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

| MTHFSD | Methenyltetrahydrofolate Synthetase Domain Containing |

| SAM | S-Adenosyl Methionine |

| SCZ | Schizophrenia |

| SNP/SNPs | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism/Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms |

| TPM | Taiwan Precision Medicine |

| TPMI | Taiwan Precision Medicine Initiative |

| TSGH | Tri-Service General Hospital |

| UTR | Untranslated Region |

References

- Ketter, T.A. Diagnostic Features, Prevalence, and Impact of Bipolar Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 71, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Hu, C.; Ren, Z.; Bai, L.; Gao, F.; Lyu, J. Trends in the Incidence and DALYs of Bipolar Disorder at Global, Regional, and National Levels: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2020, 125, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratheesh, A.; Davey, C.; Hetrick, S.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Voutier, C.; Bechdolf, A.; McGorry, P.D.; Scott, J.; Berk, M.; Cotton, S.M. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prospective Transition from Major Depression to Bipolar Disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2017, 135, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.M.; Yengo, L.; Cox, N.J.; Wray, N.R. Discovery and Implications of Polygenicity of Common Diseases. Science 2021, 373, 1468–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leussis, M.P.; Berry-Scott, E.M.; Saito, M.; Jhuang, H.; de Haan, G.; Alkan, O.; Luce, C.J.; Madison, J.M.; Sklar, P.; Serre, T.; et al. The ANK3 Bipolar Disorder Gene Regulates Psychiatric-Related Behaviors That Are Modulated by Lithium and Stress. Biol Psychiatry 2013, 73, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, C.C.; Mühleisen, T.W.; Nenadic, I.; Koch, K.; Wagner, G.; Schachtzabel, C.; Siedek, F.; Nöthen, M.M.; Rietschel, M.; Deufel, T.; et al. Common Variation in NCAN, a Risk Factor for Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia, Influences Local Cortical Folding in Schizophrenia. Psychol Med 2014, 44, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starnawska, A.; Demontis, D.; Pen, A.; Hedemand, A.; Nielsen, A.L.; Staunstrup, N.H.; Grove, J.; Als, T.D.; Jarram, A.; O’Brien, N.L.; et al. CACNA1C Hypermethylation Is Associated with Bipolar Disorder. Transl Psychiatry 2016, 6, e831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A, H.; A, L.; J, T.; S, V.-K.; M, B.; S, S.; C, B.; L, P.; T, B.; G, B.; et al. The Risk Variant in ODZ4 for Bipolar Disorder Impacts on Amygdala Activation during Reward Processing. Bipolar disorders 2013, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, Y.-J.; Huang, T.-L. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and Bipolar Disorder. Psychiatry Research 2019, 274, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovadia, G.; Shifman, S. The Genetic Variation of RELN Expression in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. PLoS One 2011, 6, e19955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.W.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A Tool Set for Whole-Genome Association and Population-Based Linkage Analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Wang, K. Genomic Variant Annotation and Prioritization with ANNOVAR and wANNOVAR. Nat Protoc 2015, 10, 1556–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium; Corresponding authors; Auton, A. Abecasis, G.R.; Steering committee; Altshuler, D.M.; Durbin, R.M.; Abecasis, G.R.; Bentley, D.R.; Chakravarti, A.; et al. A Global Reference for Human Genetic Variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, S.; Singer-Berk, M.; Watts, N.A.; Phu, W.; Goodrich, J.K.; Solomonson, M.; Genome Aggregation Database Consortium; Rehm, H. L.; MacArthur, D.G.; O’Donnell-Luria, A. Variant Interpretation Using Population Databases: Lessons from gnomAD. Human Mutation 2022, 43, 1012–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.-C.A.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chen, T.-T.; Kuo, P.-H.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Yang, H.-I.; Chen, W.J.; Su, M.-W.; Chu, H.-W.; Shen, C.-Y.; et al. Taiwan Biobank: A Rich Biomedical Research Database of the Taiwanese Population. Cell Genomics 2022, 2, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbon, S.; Ireland, A.; Mungall, C.J.; Shu, S.; Marshall, B.; Lewis, S. the AmiGO Hub; the Web Presence Working Group AmiGO: Online Access to Ontology and Annotation Data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 288–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Bailey, A.; Kuleshov, M.V.; Clarke, D.J.B.; Evangelista, J.E.; Jenkins, S.L.; Lachmann, A.; Wojciechowicz, M.L.; Kropiwnicki, E.; Jagodnik, K.M.; et al. Gene Set Knowledge Discovery with Enrichr. Current Protocols 2021, 1, e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, B.M. Introduction to Linkage Disequilibrium, the HapMap, and Imputation. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2010, 2010, pdb.top74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiela, M.J.; Chanock, S.J. LDlink: A Web-Based Application for Exploring Population-Specific Haplotype Structure and Linking Correlated Alleles of Possible Functional Variants. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3555–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiela, M.J.; Chanock, S.J. LDassoc: An Online Tool for Interactively Exploring Genome-Wide Association Study Results and Prioritizing Variants for Functional Investigation. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 887–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeze, C.E.; Haugen, E.; Gutierrez-Arcelus, M.; Yao, X.; Teschendorff, A.; Beck, S.; Dunham, I.; Stamatoyannopoulos, J.; Franceschini, N.; Machiela, M.J.; et al. FORGEdb: A Tool for Identifying Candidate Functional Variants and Uncovering Target Genes and Mechanisms for Complex Diseases. Genome Biol 2024, 25, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.-S.; Liu, X.-F.; Aragam, N. A Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis Identifies Novel Loci Associated with Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Schizophrenia Research 2010, 124, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, T.A.; Marwaha, S. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Bipolar Disorder. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology 2018, 8, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.-P.; Xu, D.; Wang, L.; Mao, Y.-X.; Li, Y.; Cheng, M.-T.; Zhou, C.-Z.; Hou, W.-T.; Chen, Y. Structural Basis of Substrate Recognition and Translocation by Human Very Long-Chain Fatty Acid Transporter ABCD1. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M. The Genetics of ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier, 2005; Vol. 400, pp. 409–429 ISBN 978-0-12-182805-9.

- Dean, M. ATP-binding Cassette (ABC) Transporter Supergene Family: Genetics and Evolution. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences; Wiley, 2008 ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6.

- Wada, M. Role of ABC Transporters in Cancer Development and Malignant Alteration. YAKUGAKU ZASSHI 2022, 142, 1201–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salajegheh, A. Adenosine Triphosphate-Binding Cassette (ABC) Lipid Transporters. In Angiogenesis in Health, Disease and Malignancy; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-28138-4. [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq, S.; Skrzypski, J.; Courvoisier, A.; Gondcaille, C.; Bonnetain, F.; André, A.; Chardigny, J.-M.; Bellenger, S.; Bellenger, J.; Narce, M.; et al. Effect of Dietary Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on the Expression of Peroxisomal ABC Transporters. Biochimie 2008, 90, 1602–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, N.; Ogura, J.; Yoshida, F.; Hattori, K.; Hori, H.; Aizawa, E.; Ishida, I.; Kunugi, H. Altered Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Levels in Relation to Proinflammatory Cytokines, Fatty Acid Desaturase Genotype, and Diet in Bipolar Disorder. Transl Psychiatry 2019, 9, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-C.; Huang, S.-Y.; Su, K.-P.; Lu, M.-L.; Huang, M.-C.; Chen, C.-C.; Shen, W.W. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Deficit in Patients with Bipolar Mania. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2003, 13, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Jeong, S. 3’UTR Diversity: Expanding Repertoire of RNA Alterations in Human mRNAs. Molecules and Cells 2023, 46, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Tian, B. The Emerging Theme of 3′UTR mRNA Isoform Regulation in Reprogramming of Cell Metabolism. Biochemical Society Transactions 2023, 51, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello, A.; Fischer, B.; Eichelbaum, K.; Horos, R.; Beckmann, B.M.; Strein, C.; Davey, N.E.; Humphreys, D.T.; Preiss, T.; Steinmetz, L.M.; et al. Insights into RNA Biology from an Atlas of Mammalian mRNA-Binding Proteins. Cell 2012, 149, 1393–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karas Kuželički, N. S-Adenosyl Methionine in the Therapy of Depression and Other Psychiatric Disorders. Drug Development Research 2016, 77, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, N.; Xing, G.; Yang, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, G. Comparison of Inflammatory, Nutrient, and Neurohormonal Indicators in Patients with Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2021, 137, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdogan, M.G.; Aydin, E.F.; Ustundag, M.F.; Ceyhun, H.A.; Oral, E.; Bakan, E. Homocysteine, Chronotype and Clinical Course in Bipolar Disorder Patients. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 2020, 74, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, I.; Kamata, S.; Ito, S.; Shimonaga, A.; Koizumi, M.; Tsushima, M.; Miura, A.; Nagata, T.; Tosaka, Y.; Ohtani, H.; et al. A High-Methionine Diet for One-Week Induces a High Accumulation of Methionine in the Cerebrospinal Fluid and Confers Bipolar Disorder-like Behavior in Mice. IJMS 2022, 23, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, S.; Tang, B.; Head, S.R.; Gilmartin, T.J.; Sutcliffe, J.G.; Dean, B.; Thomas, E.A. Molecular Profiles of Schizophrenia in the CNS at Different Stages of Illness. Brain Research 2008, 1239, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, M.S.; Uhlmann, A.; Nday, C.M.; Glatt, S.J.; Mitt, M.; Metsalpu, A.; Stein, D.J.; Illing, N. Candidate Gene Networks and Blood Biomarkers of Methamphetamine-Associated Psychosis: An Integrative RNA-Sequencing Report. Transl Psychiatry 2016, 6, e802–e802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.-C.; Chou, L.-S.; Lin, C.-H.; Wu, H.-C.; Li, D.-J.; Tseng, P.-T. Serum Folate Levels in Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Table 1. Participant Information in This Study | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | BD | Control | p-value | |

| Sex | Male | 59 | 11793 | 0.63 |

| Female | 69 | 14329 | ||

| Age (Average ± SD) |

>90 | 0 | 197 (93 ± 2) | - |

| 80-89 | 1 (81 ± 0) | 895 (83 ± 3) | - | |

| 70-79 | 7 (73 ± 3) | 2970 (73 ± 3) | 0.86 | |

| 60-69 | 25 (64 ± 3) | 5681 (64 ± 3) | 0.26 | |

| 50-59 | 28 (54 ± 3) | 5124 (55 ± 3) | 0.54 | |

| 40-49 | 25 (44 ± 3) | 4096 (44 ± 3) | 0.16 | |

| 30-39 | 24 (35 ± 3) | 3424 (35 ± 3) | 0.21 | |

| 20-29 | 15 (25 ± 3) | 3002 (25 ± 3) | 0.56 | |

| 10-19 | 3 (15 ± 2) | 586 (15 ± 3) | 0.07 | |

| <9 | 0 | 147 (8 ± 1) | - | |

| Table 2. Variants Obtained from the Association Study Results with High Significance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHR | Position | SNP ID | Refa | Altb | p-valuec | Odds Ratio | Region | Relative Gene |

| 1 | 199219779 | rs6427761 | A | G | 1.56E-06 | 2.02 | intergenic | LINC01221;NR5A2 |

| 1 | 199223240 | rs6658422 | C | T | 7.01E-06 | 1.96 | intergenic | LINC01221;NR5A2 |

| 1 | 199262608 | rs7538098 | T | G | 7.63E-07 | 2.08 | intergenic | LINC01221;NR5A2 |

| 2 | 114648288 | rs74419649 | T | C | 5.17E-06 | 1.88 | intronic | DPP10 |

| 3 | 188587806 | rs79221549 | C | T | 7.47E-06 | 2.09 | intronic | LPP |

| 15 | 88454801 | rs6496485 | G | A | 1.18E-06 | 2.01 | intergenic | NTRK3-AS1;MRPL46 |

| 16 | 86542131 | rs3829533 | C | T | 4.06E-06 | 1.95 | exonic | MTHFSD |

| 20 | 19027381 | rs755981 | G | T | 6.48E-06 | 1.81 | intergenic | C20orf78;SLC24A3 |

| 20 | 19031000 | rs6081464 | T | C | 5.41E-08 | 2.09 | intergenic | C20orf78;SLC24A3 |

| 22 | 480s87568 | rs7289613 | C | T | 2.14E-06 | 2.06 | intergenic | LOC284930;MIR3201 |

| X | 153741041 | rs11156606 | A | C | 6.69E-06 | 2.36 | intronic | ABCD1 |

|

a Allele in control. b Allele in case. c Filter by p < 10-5 | ||||||||

| Table 3. Allele Frequencies of Variants from Other Genetic Projects | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | TPMIa | TWBankb | 1000gc | gnomADd | ||||||||||

| SNP ID | Alt | Case | Control | - | - | AFRe | AMR | EAS | EUR | AFR | AMR | EAS | FIN | NFE |

| rs6427761 | G | 0.231 | 0.129 | 0.134 | 0.134 | 0.200 | 0.098 | 0.160 | 0.022 | 0.195 | 0.087 | 0.123 | 0.044 | 0.025 |

| rs6658422 | T | 0.215 | 0.122 | 0.127 | 0.127 | 0.290 | 0.100 | 0.150 | 0.047 | 0.249 | 0.101 | 0.115 | 0.089 | 0.043 |

| rs7538098 | G | 0.224 | 0.122 | 0.127 | 0.126 | 0.290 | 0.099 | 0.150 | 0.041 | 0.268 | 0.086 | 0.118 | 0.076 | 0.044 |

| rs74419649 | C | 0.273 | 0.167 | 0.168 | 0.157 | 0.011 | 0.260 | 0.180 | 0.110 | 0.021 | 0.318 | 0.160 | 0.213 | 0.133 |

| rs79221549 | T | 0.169 | 0.089 | 0.089 | 0.084 | 0.002 | 0.037 | 0.091 | 0.033 | 0.006 | 0.039 | 0.084 | 0.038 | 0.028 |

| rs6496485 | A | 0.242 | 0.137 | 0.137 | 0.131 | 0.076 | 0.085 | 0.140 | 0.076 | 0.091 | 0.076 | 0.138 | 0.074 | 0.084 |

| rs3829533 | T | 0.238 | 0.138 | 0.138 | 0.150 | 0.008 | 0.110 | 0.160 | 0.110 | 0.023 | 0.106 | 0.144 | 0.102 | 0.092 |

| rs755981 | T | 0.332 | 0.216 | 0.220 | 0.205 | 0.550 | 0.420 | 0.210 | 0.430 | 0.543 | 0.370 | 0.213 | 0.561 | 0.470 |

| rs6081464 | C | 0.285 | 0.160 | 0.163 | 0.152 | 0.022 | 0.110 | 0.160 | 0.130 | 0.039 | 0.075 | 0.158 | 0.140 | 0.127 |

| rs7289613 | T | 0.203 | 0.110 | 0.113 | 0.120 | 0.160 | 0.069 | 0.095 | 0.098 | 0.168 | 0.041 | 0.121 | 0.133 | 0.096 |

| rs11156606 | C | 0.157 | 0.073 | 0.075 | 0.081 | 0.698 | 0.135 | 0.099 | 0.115 | 0.640 | 0.131 | 0.087 | 0.110 | 0.119 |

|

a Taiwan Precision Medicine Initiative. b Taiwan Biobank. c 1000 Genomes global minor allele frequency. d gnomAD (genomes) allele frequencies. e AFR: African. AMR: American. EAS: East Asian. EUR: European. FIN: Finnish. NFE: Non-Finnish European. | ||||||||||||||

| Table 4. GO annotation of variant genes a | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| GO_ID | Term | p-value | Gene |

| GO:0042758 | long-chain fatty acid catabolic process | 0.003 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0042760 | very long-chain fatty acid catabolic process | 0.004 | ABCD1 |

| GO:2001280 | positive regulation of unsaturated fatty acid biosynthetic process | 0.004 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0032000 | positive regulation of fatty acid beta-oxidation | 0.005 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0043574 | peroxisomal transport | 0.005 | ABCD1 |

| GO:1900407 | regulation of cellular response to oxidative stress | 0.005 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0043217 | myelin maintenance | 0.006 | ABCD1 |

| GO:1990535 | neuron projection maintenance | 0.006 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0046321 | positive regulation of fatty acid oxidation | 0.007 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0051900 | regulation of mitochondrial depolarization | 0.007 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0055089 | fatty acid homeostasis | 0.007 | ABCD1 |

| GO:1902882 | regulation of response to oxidative stress | 0.007 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0030497 | fatty acid elongation | 0.008 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0031998 | regulation of fatty acid beta-oxidation | 0.008 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0036109 | alpha-linolenic acid metabolic process | 0.008 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0045723 | positive regulation of fatty acid biosynthetic process | 0.008 | ABCD1 |

| GO:1903427 | negative regulation of reactive oxygen species biosynthetic process | 0.008 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0033540 | fatty acid beta-oxidation using acyl-CoA oxidase | 0.009 | ABCD1 |

| GO:1903715 | regulation of aerobic respiration | 0.009 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0002082 | regulation of oxidative phosphorylation | 0.010 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0009792 | embryo development ending in birth or egg hatching | 0.010 | NR5A2 |

| GO:0046320 | regulation of fatty acid oxidation | 0.010 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0106027 | neuron projection organization | 0.010 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0003254 | regulation of membrane depolarization | 0.011 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0009890 | negative regulation of biosynthetic process | 0.011 | ABCD1 |

| GO:1900016 | negative regulation of cytokine production involved in inflammatory response | 0.011 | ABCD1 |

| GO:1902001 | fatty acid transmembrane transport | 0.011 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0032365 | intracellular lipid transport | 0.013 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0043651 | linoleic acid metabolic process | 0.013 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0045046 | protein import into peroxisome membrane | 0.013 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0050994 | regulation of lipid catabolic process | 0.013 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0050996 | positive regulation of lipid catabolic process | 0.013 | ABCD1 |

| GO:2000378 | negative regulation of reactive oxygen species metabolic process | 0.014 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0007031 | peroxisome organization | 0.015 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0015919 | peroxisomal membrane transport | 0.016 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0006625 | protein targeting to peroxisome | 0.017 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0045070 | positive regulation of viral genome replication | 0.017 | NR5A2 |

| GO:1903426 | regulation of reactive oxygen species biosynthetic process | 0.017 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0043266 | regulation of potassium ion transport | 0.018 | DPP10 |

| GO:1904062 | regulation of cation transmembrane transport | 0.018 | DPP10 |

| GO:0015909 | long-chain fatty acid transport | 0.019 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0000038 | very long-chain fatty acid metabolic process | 0.020 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0051881 | regulation of mitochondrial membrane potential | 0.024 | ABCD1 |

| GO:1900015 | regulation of cytokine production involved in inflammatory response | 0.026 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0042552 | myelination | 0.028 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0006635 | fatty acid beta-oxidation | 0.031 | ABCD1 |

| GO:1903078 | positive regulation of protein localization to plasma membrane | 0.031 | DPP10 |

| GO:1904377 | positive regulation of protein localization to cell periphery | 0.031 | DPP10 |

| GO:0033559 | unsaturated fatty acid metabolic process | 0.032 | ABCD1 |

| GO:1901379 | regulation of potassium ion transmembrane transport | 0.032 | DPP10 |

| GO:1903578 | regulation of ATP metabolic process | 0.033 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0019395 | fatty acid oxidation | 0.035 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0048524 | positive regulation of viral process | 0.037 | NR5A2 |

| GO:0007009 | plasma membrane organization | 0.038 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0031329 | regulation of cellular catabolic process | 0.038 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0055088 | lipid homeostasis | 0.038 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0045069 | regulation of viral genome replication | 0.039 | NR5A2 |

| GO:0009062 | fatty acid catabolic process | 0.041 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0006633 | fatty acid biosynthetic process | 0.042 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0055092 | sterol homeostasis | 0.042 | ABCD1 |

| GO:1903076 | regulation of protein localization to plasma membrane | 0.047 | DPP10 |

| GO:0001676 | long-chain fatty acid metabolic process | 0.049 | ABCD1 |

| GO:0010232 | vascular transport | 0.049 | SLC24A3 |

| GO:0150104 | transport across blood-brain barrier | 0.050 | SLC24A3 |

| aSelected based on p-value < 0.05. | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).