Introduction

Clostridium cadaveris is an anaerobic, spore-forming bacterium, first described by Klein in 1899 [

1,

2]. True to its name, it was initially identified as part of the "putrefying flora," associated with human decomposition and decaying tissues. Historically considered non-pathogenic to humans and linked to cadaveric environments, recent clinical evidence suggests its infectious potential [

3]. While rare, C. cadaveris has been implicated in serious conditions such as sepsis, particularly in patients with compromised immunity, chronic wounds, or those undergoing invasive medical procedures.

A study by Brook and colleagues analyzed blood cultures collected from June 1973 to June 1985 at the microbiology laboratories of Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, DC [

4]. Their findings indicated that anaerobic bacteria were identified in 12% of patients with positive blood cultures and bacteremia caused by Clostridium species accounted for 0.5% to 2% of all cases [

4,

5]. The Clostridium genus, are pleomorphic anaerobic spore-forming bacilli and includes several species, such as C. perfringens, C. septicum, C. difficile, C. botulinum, C. tetani, C. sordellii, C. histolyticum and C. innocuum [

6,

7]. However, C. cadaveris remains exceptionally rare, with only 14 cases reported in the literature, primarily as individual case reports.

Case Presentation:

A 50-year-old female with metastatic rectal adenocarcinoma, involving the liver and lungs, was admitted to the hospital from the cancer clinic while undergoing fifth-line chemotherapy. She presented with fever, lower abdominal discomfort, and anemia secondary to rectal bleeding. On admission, her vital signs showed a fever of 38.8°C and tachycardia with a heart rate of 120 beats per minute. Laboratory results revealed a hemoglobin level of 6.9 g/dL and leukopenia. Initial management with fluids and a blood transfusion led to partial improvement, but her fever persisted. Broad-spectrum antibiotics, vancomycin, and piperacillin-tazobactam were then initiated. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with intravenous contrast demonstrated progression of metastatic disease, including enlargement of the left ovarian metastasis, a new large right ovarian mass (

Figure 1), slight worsening of pulmonary and hepatic metastases, and increased rectal mass/thickening (

Figure 1), but no clear source of infection was identified.

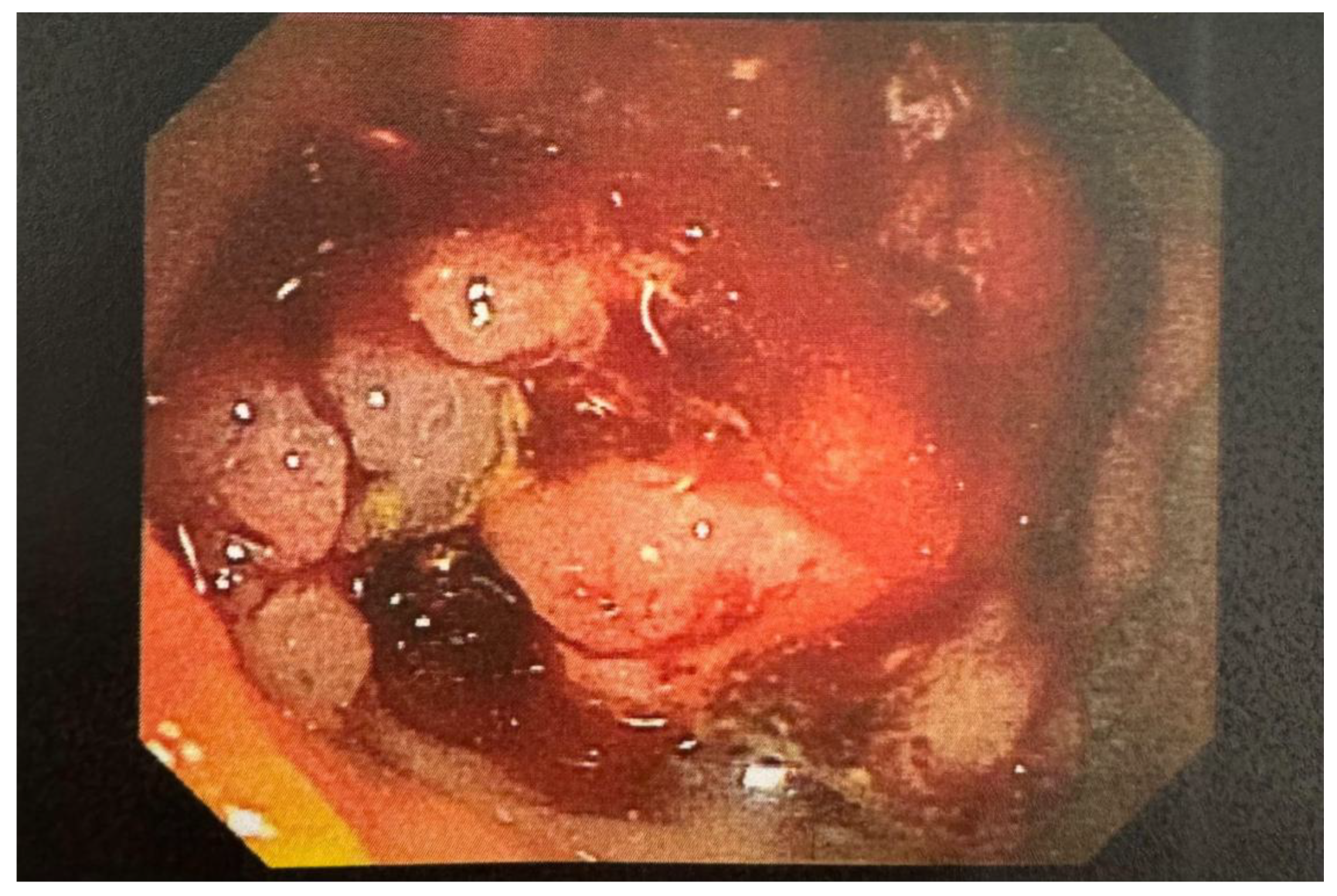

Initial blood cultures grew Clostridium cadaveris, and after 48 hours, vancomycin was discontinued, continuing piperacillin-tazobactam. By day seven, her white blood cell count increased to 13 K/uL with neutrophilia, and she remained febrile. Repeat blood cultures grew C. cadaveris. Imaging studies, including a repeat CT scan and transvaginal ultrasound, showed further evidence of metastatic disease, including a large cystic pelvic mass and bilateral ovarian metastases, but no definitive infectious focus was identified. Given recurrent bacteremia, additional workup was done to look for the source of infection. A WBC scan and echocardiogram did not reveal any infectious source. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed a 3 cm hiatal hernia and non-bleeding erosive gastropathy, while flexible sigmoidoscopy revealed intermittent bleeding from a mass 20 cm from the anal verge (

Figure 2), with suspicion of circumferential gastrointestinal bleeding as the source of bacteremia. Given the clinical findings, her chemotherapy port was removed, and antibiotic therapy was switched to meropenem.

Blood cultures continued to grow C. cadaveris daily until day 9, prompting the addition of metronidazole to meropenem due to persistent bacteremia. After 48 hours of metronidazole therapy, blood cultures turned negative. The patient had a PICC line inserted following two consecutive negative blood cultures. She was discharged with ertapenem via the PICC line and oral metronidazole for 14 days after clearance of the bacteremia. Due to her advanced, refractory cancer and poor prognosis, palliative care was consulted. However, the patient expressed a desire to pursue alternative chemotherapy once the infections were resolved. She was scheduled for regular outpatient follow-up with her oncologist.

Discussion:

Clostridium cadaveris, though typically considered non-pathogenic, can occasionally cause severe infections like bacteremia. These infections are more likely to occur in immunocompromised individuals, those with chronic wounds (e.g., pressure ulcers or long-standing osteomyelitis), patients undergoing invasive surgical procedures, or those with significant comorbid conditions, and trauma. Recent advancements in detecting anaerobes from clinical samples include methods like 16S rRNA gene sequencing, MALDI-TOF MS, multiplex PCR, and DNA hybridization and these techniques enhance strain differentiation, aiding in infection characterization and antimicrobial susceptibility prediction [

8].

A review of 14 cases revealed an average patient age of 49.1 years (range 11–75 years), with 7 female cases reported. Among the 13 individuals with documented immune status, 7 were immunocompromised, primarily due to malignancies, chemotherapy, or corticosteroid use for conditions like acute exacerbations of COPD. The immune status of one individual remained unspecified. While immunocompromised patients were predominantly affected, chronic wounds or surgical interventions were linked to cases in immunocompetent individuals.

Probable Sources of Infection:

Disruption of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract plays a central role in the development of bacteremia. Although C. cadaveris is part of the normal flora of the skin and mucosa, its fastidious growth characteristics make it challenging to isolate, often leading to underdiagnosis. GI disruption has frequently been identified as the primary source of infection and is associated with conditions like spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, diverticular abscesses, splenic abscesses, and abscesses in the lesser sac [

10,

9,

11]. An unusual case involved an immunocompetent individual working on a pig farm who developed pulmonary empyema with C. cadaveris isolated from pleural fluid, possibly related to handling deceased pigs [

12]. Chronic wounds, including decubitus ulcers and osteomyelitis, trauma, and surgery can also be seen as potential sources. These reports emphasize the GI tract as the predominant origin of C. cadaveris bacteremia.

In our case, flexible sigmoidoscopy identified a fungating, partially obstructing mass approximately 20 cm from the anus, involving two-thirds of the lumen with oozing areas. This, combined with the patient’s immunosuppression due to metastatic rectal adenocarcinoma, strongly indicated a GI source for the bacteremia. This observation reinforces the GI tract as the most common source of C. cadaveris infections.

Seven partial C. cadaveris genome assemblies exist, with the first complete sequence recently derived from cryopreserved colon adenocarcinoma tissue of a 67-year-old female patient [

13]. These genomic analyses, especially regarding tissue necrosis in human diseases, help provide insights into its pathogenic mechanisms, resistance profiles, and virulence factors [

13]. Further research is warranted to elucidate the mechanisms, clinical manifestations, and optimal management strategies for these infections.

Management Strategies:

Since Clostridium cadaveris infections are rare, there are no established treatment guidelines. However, cases have been successfully treated with antibiotics such as penicillin, metronidazole, clindamycin, vancomycin, and carbapenems, with metronidazole being the most commonly used. Citron et al. assessed the in vitro effectiveness of glycolipodepsipeptide antibiotics (Ramoplanin, Teicoplanin, and Vancomycin) using an agar dilution technique to determine which drugs were active against C. cadaveris [

14]. The choice of antibiotic depends on the bacteria’s sensitivity, the infection site, the availability of drugs, and the doctor’s decision.

Previous reports show that C. cadaveris is sensitive to antibiotics like metronidazole (MIC 0.25–0.35 mg/mL), clindamycin, cefoxitin, imipenem, vancomycin, meropenem, and amoxicillin/clavulanate, with no resistance to metronidazole or other antibiotics found. In 14 cases, seven were treated with metronidazole, while others received clindamycin, amoxicillin/clavulanate, imipenem-cilastin, or vancomycin. Kiu et al. isolated C. tertium LH009, C. cadaveris LH052, and three C. paraputrificum strains from preterm infants in neonatal intensive care units, sequencing their genomes with Illumina HiSeq [

15]. Genomic analysis found resistance to tetracycline and methicillin, as well as phospholipases and toxins, providing insights to improve diagnosis and treatment, but more research is needed.

In our case, the patient was treated with oral metronidazole and intravenous ertapenem for 14 days, showing significant improvement. Although metronidazole seems effective, further studies are necessary to establish clear treatment guidelines.

Clinical Features, Prognosis, and Mortality:

Yamamoto et al. studied Clostridium bacteremia at Shizuoka Cancer Center from 2004 to 2018, finding hepatobiliary infections and gastrointestinal tumors as the main sources, with Cl. perfringens and Cl. ramnosum being a common species, polymicrobial bacteremia in 62.5% of cases, and a 30-day mortality rate of 42.5%, but no cases of Cl. cadaveris [

16]. Infections caused by

C. cadaveris often present with symptoms such as, fever, diarrhea, joint pain, and abdominal pain. From the data available, the prognosis is generally favorable when appropriate treatment is administered, with 11 out of 14 reviewed cases showing improvement. Mortality appears linked more to underlying conditions than the infection itself, though the infection may exacerbate patient outcomes.

Three cases illustrate fatalities possibly related to C. cadaveris infections. One involved a female patient with bacterial peritonitis and chronic liver disease who succumbed to an upper GI hemorrhage. Another case described a patient with gastrointestinal symptoms, positive blood cultures, and cardiac findings, who died despite initial improvement with antibiotics. A third case involved a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and pancytopenia, who experienced clinical deterioration despite treatment and ultimately died from multiorgan failure.

These cases highlight the need for heightened awareness and timely intervention to manage C. cadaveris infections effectively. Further documentation and studies are essential to improve understanding of the clinical characteristics, treatment outcomes, and prognosis associated with these rare infections.

Table 1.

Summary of reported Clostridium Cadaveris infection cases.

Table 1.

Summary of reported Clostridium Cadaveris infection cases.

| Gender/Age |

Probable Source of Infection |

Antibiotic |

Underlying disease |

Co-Organism |

Prognosis |

Culture Source

And Sensitivity/ Resistant |

| 50 yr/Fe |

Gastro-intestinal |

IV Ertapenem and oral Metronidazole |

Metastatic Rectal Adenocarcinoma and Liver metastases |

None |

Recovered |

Blood |

| 17yr/Fe[10] |

Gastro-intestinal |

Metronidazole and Surgical drainage |

Autoimmune hepatitis,

End-stage liver disease

|

None |

Recovered |

Splenic abscess |

| 74yr/Fe[11] |

Gastro-intestinal |

Imipenem and Cilastin sodium and hydrocortisone

|

Metastatic Ovarian Adenocarcinoma |

None |

Recovered |

Blood

(Strain was sensitive to cefoxitin, clindamycin, imipenem, meropenem, metronidazole, and vancomycin)

|

| 32yr/M[17] |

Osteomyelitis |

Oral Clindamycin For 3 Months |

Chronic

Osteomyelitis |

None |

Recovered |

Bone

(sensitive to penicillin, tetracycline, erythromycin, fusidic acid, rifampicin, linezolid, vancomycin and metronidazole) |

| 58yr/Fe[9] |

Gastro-intestinal |

Penicillin G |

Alcoholic Chronic Liver Disease |

- |

Death due to Upper GI-bleeding |

Ascites |

75yr/m

[18] |

Unknown |

Metronidazole |

COPD |

None |

Recovered |

Blood

(Susceptible to

Metronidazole (MIC-0.32 mg/ml)) |

68yr/m

[18] |

Gastro-intestinal |

Intravenous Amoxicillin/Clavulanic Acid and Intravenous Metronidazole |

Cardiovascular disease [pericarditis] |

None |

Died after initial period of improvement |

Blood

(Susceptible to Metronidazole (MIC B/0.25 mg/ml)) |

72yr/Fe

[19] |

Decubitus Ulcer |

Ceftriaxone plus Metronidazole

upgraded to for coverage of other co-organism

Metronidazole, Oxacillin and Cefotaxime |

Dual malignancies of breast cancer and locally advanced shoulder myxo-fibrosarcoma on radiotherapy. Infected sacral decubitus ulcer; stage IV |

S. hominis,

&

P. mirabilis |

Recovered |

Blood

(Susceptibleto metronidazole

minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC- of 0.032)) |

19yr/M

[20] |

Unknown |

Metronidazole, Pip/Taz and oral Vancomycin |

SMV thrombus |

None |

Recovered |

Blood |

42yr/M

[21] |

Decubitus Ulcer |

Vancomycin and Rifampin |

Paraplegic with necrotic decubitus with purulent discharge |

MRSA |

Recovered |

Blood |

33yr/M

[12] |

Unknown

(? Aerosol) |

amoxicillin/clavulanate

and pneumonectomy.

and later

Metronidazole was added and pericardiotomy done |

Pulmonary empyema progressing to pericardial effusion |

Clostridium

difficile |

Recovered |

Pleural fluid

(Susceptible to amoxicillin/clavulanate and metronidazole.) |

61yr/Fe

[22] |

Gastro-intestinal |

Imipenem, Amikacin and [Vancomycin for Cl. Cadaveris] |

Metastatic RCC [S/P Surgery] and

Lesser sac abscess. |

Escherichia coli &

Bacteroides sp |

Recovered |

Blood

(But culture of the abscess grew Escherichia coli and Bacteroides sp.) |

66yr/Fe

[22] |

Unknown |

Mezlocillin, Gentamycin, Metronidazole

later upgraded to

Ceftazidime, Vancomycin Metronidazole and Tobramycin |

Chronic lymphoproliferative disease |

Corynebacterium sp. &

Bacillus sp |

Died of multiple

organ failure |

Blood culture

(susceptible to clindamycin (MICB/0.25 mg/ml) and metronidazole (MICB/0.25 mg/ml)) |

60yr/Fe

[23] |

Iatrogenic |

Intravenous clindamycin |

Breast carcinoma with metastatic lytic lesion

with

septic arthritis in

(S/P Total hip arthroplasty) |

None |

Recovered |

Bone debridement |

11yr/M

[24] |

Trauma |

Empirically oral Amoxicillin-Clavulanate and Piperacillin-Tazobactam

upgrade to

IV Cefepime and Daptomycin

and Sequential debridement |

Traumatic Nail entering knee |

None |

Recovered |

Arthrocentesis |

Conclusion:

This case report and literature review highlight the significant role of Clostridium cadaveris as a potential pathogen, especially in individuals with weakened immune systems or multiple comorbidities. Although traditionally considered non-pathogenic and linked to decaying tissues, C. cadaveris can lead to infections in situations, often related to gastrointestinal disturbances, chronic wounds, or invasive procedures and trauma. Treatment for C. cadaveris infections involves appropriate antibiotics, with metronidazole being the most commonly used. Furthermore, C. cadaveris shows susceptibility to various antibiotics, including carbapenems, clindamycin, and vancomycin; with no documentation of resistant cases. Early diagnosis and targeted therapy are crucial for achieving positive clinical outcomes. While the prognosis is generally favorable with proper treatment, severe underlying conditions may negatively impact recovery, and in some cases, C. cadaveris infections may contribute to clinical deterioration or death. This review vocalizes the need for greater clinical awareness of C. cadaveris as a potential pathogen, particularly in vulnerable patients. Further research, genomic study, and case documentation are essential to better understand its pathogenic mechanisms, clinical features, and optimal treatment strategies. Enhanced awareness and knowledge will help clinicians more effectively recognize and manage this rare but important condition, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

Laxman Wagle: Conceptualization; supervision, project administration; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Prachi Bhanvadia: Conceptualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Anuj Timshina: Project administration; supervision; writing-original draft. Mustafa Abdulmahdi: Project administration; validation; visualization; supervision, writing – original draft. Ravindra Karmakar: Project administration; validation; visualization; supervision, writing – original draft.

Funding Information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval Statements

Our institution does not require ethical approval to report individual cases or case series.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient and family for permitting us to report the case.

Conflict of Interest Statements

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Saito, A.; Wu, S.; Kwoh, E. Clostridium Cadaveris Bacteremia in an Immunocompromised Host. J. Brown Hosp. Med. 2024, 3, 115586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein: Ein beitrag zur bakteriologie der leichenverwesung - Google Scholar. Accessed December 21, 2024. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Zentralbl%20Bakteriol%20Parasitenkd%20Infektionskr%20Hyg&title=%5BEin%20beitrag%20zur%20bakteriologie%20der%20leichenverwesung%5D&author=E%20Klein&volume=1&publication_year=1899&pages=278-284&.

- Willis, AT. Anaerobic Bacteriology: Clinical and Laboratory Practice. Butterworth-Heinemann; 2014.

- Brook, I. Anaerobic Bacterial Bacteremia: 12-Year Experience in Two Military Hospitals. J. Infect. Dis. 1989, 160, 1071–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, G.; Ngoi, S.S.; Cennerazzo, W.; Harris, L.; DeCosse, J.J. Clostridial septicemia in an urban hospital. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992, 174, 291–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jousimies-Somer, H.; Summanen, P. Recent Taxonomic Changes and Terminology Update of Clinically Significant Anaerobic Gram-Negative Bacteria (Excluding Spirochetes). Clin. Infect. Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2002, 35, S17–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jousimies-Somer H. Wadsworth-KTL anaerobic bacteriology manual. No Title. Published online 2002. Accessed December 21, 2024. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1130282272595631872.

- Advancement in the routine identification of anaerobic bacteria by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry | European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. Accessed December 21, 2024. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10096-013-1865-1.

- Herman R, Goldman IS, Bronzo R, McKinley MJ. Clostridium cadaveris: An Unusual Cause of Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis. | EBSCOhost. January 1, 1992. Accessed December 21, 2024. https://openurl.ebsco.com/contentitem/gcd:16018278?sid=ebsco:plink:crawler&id=ebsco:gcd:16018278.

- Yan, J.; Hinds, R.; Burgner, D. Clostridium Cadaveris Splenic Abscess in an Adolescent. J. Paediatr. Child Heal. 2018, 54, 460–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wu, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y. First Report of Bacteremia Caused by Clostridium cadaveris in China. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, ume 14, 5411–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleural Empyema Due to Clostridium difficile and... - Google Scholar. Accessed December 21, 2024. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C21&q=Pleural+Empyema+Due+to+Clostridium+difficile+and+Clostridium+cadaveris&btnG=.

- McGlinchey, A.S.; Zepeda-Rivera, M.A.; Stepanovica, M.; Baryiames, A.A.; Jones, D.S.; LaCourse, K.D.; Bullman, S.; Johnston, C.D. Complete Genome Sequence of Clostridium cadaveris IFB3C5, Isolated from a Human Colonic Adenocarcinoma. Genome Announc. 2022, 11, e0113521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citron, D.M.; Merriam, C.V.; Tyrrell, K.L.; Warren, Y.A.; Fernandez, H.; Goldstein, E.J.C. In Vitro Activities of Ramoplanin, Teicoplanin, Vancomycin, Linezolid, Bacitracin, and Four Other Antimicrobials against Intestinal Anaerobic Bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 2334–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiu, R.; Caim, S.; Alcon-Giner, C.; Belteki, G.; Clarke, P.; Pickard, D.; Dougan, G.; Hall, L.J. Preterm Infant-Associated Clostridium tertium, Clostridium cadaveris, and Clostridium paraputrificum Strains: Genomic and Evolutionary Insights. Genome Biol. Evol. 2017, 9, 2707–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Itoh, N.; Sugiyama, T.; Kurai, H. Clinical features of Clostridium bacteremia in cancer patients: A case series review. J. Infect. Chemother. 2020, 26, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, R.A.; Lomas-Cabeza, J.; Stubbs, D.; McNally, M. Clostridium cadaveris Osteomyelitis: an Unusual Pathogen which Highlights the Importance of Deep Tissue Sampling in Chronic Osteomyelitis. J. Bone Jt. Infect. 2020, 5, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schade, R.P.; Van Rijn, M.; Timmers, H.J.L.M.; Dofferhoff, A.S.M.; Klaassen, C.H.W.; Meis, J.F.G.M. Clostridium cadaveris bacteraemia: Two cases and review. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 38, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abarca, J.; Awada, B.; Itkin, B.; Milupi, M. Poly-microbial Clostridium cadaveris bacteremia in an immune-compromised patient. Oxf. Med Case Rep. 2023, 2023, omac146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, C.G.; Heitmann, P.T.; McDonald, C.R. Clostridium cadaveris bacteraemia with associated superior mesenteric vein thrombus. ANZ J. Surg. 2021, 91, E531–E532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poduval, R.D.; Mohandas, R.; Unnikrishnan, D.; Corpuz, M. Clostridium cadaveris Bacteremia in an Immunocompetent Host. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1999, 29, 1354–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gucalp, R.; Motyl, M.; Carlisle, P.; Dutcher, J.; Fuks, J.; Wiernik, P.H. Clostridium cadaveris bacteremia in the immunocompromised host. Med Pediatr. Oncol. 1993, 21, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morshed, S.; Malek, F.; Silverstein, R.M.; O'Donnell, R.J. Clostridium cadaveris Septic Arthritis after Total Hip Arthroplasty in a Metastatic Breast Cancer Patient. J. Arthroplast. 2007, 22, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemonnier, N.; Payen, M.; Curado, J. Trauma-Induced Clostridium cadaveris Septic Arthritis of the Knee in an Immunocompetent Young Patient: A Case Report. Am. J. Case Rep. 2024, 25, e943084–e943084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).