Submitted:

16 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

- Viral persistence: This may explain some postherpetic reactions, since viral DNA has been isolated in certain cases. However, after herpetic infections resolve, viral DNA is no longer detected. This mechanism likely applies only to reactions occurring within a short interval (less than four weeks) after the herpes infection. [6,9]

- Lymphovascular microvasculature alteration: Damage to the microcirculation can render an area unable to respond adequately to subsequent insults, leading to localized inflammation at the same site.[6]

- Neural injury: Damaged dermal nerve fibers can contribute to disease pathogenesis, either directly through neuropeptide release or indirectly via immune system activation.[6] Specifically, neuropeptides such as nerve growth factor (NGF), which regulates skin epithelization, angiogenesis and formation of extracellular matrix,[27] as well as substance P from damaged nerve endings, which might play a crucial role in inducing the development of epidermal changes. [28]

| INFLAMMATORY DISEASES |

INFECTIONS |

|---|---|

| Acne | Molluscum contagiosum |

| Acneiform lesions | Warts and papillomata |

| Actinic granuloma (O’Brien)[31] | Candidiasis |

| Bullous pemphigoid[28] | Dermatophytosis |

| Chronic cutaneous graft-versus-host disease | |

| Chronic small vessel vasculitis (Extrafacial eosinophilic granuloma or Lever granuloma)[32] | |

| Chronic urticaria[33] | |

| Comedones | |

| Comedonic-microcystic reactions | |

| Contact dermatitis | |

| "Dysimmune" reactions | |

| Eosinophilic dermatosis | |

| Erythema annulare centrifugum | |

| Fibroelastolytic papulosis | |

| Folliculitis (granulomatous or eosinophilic [34]) | TUMORS AND PSEUDOTUMORS |

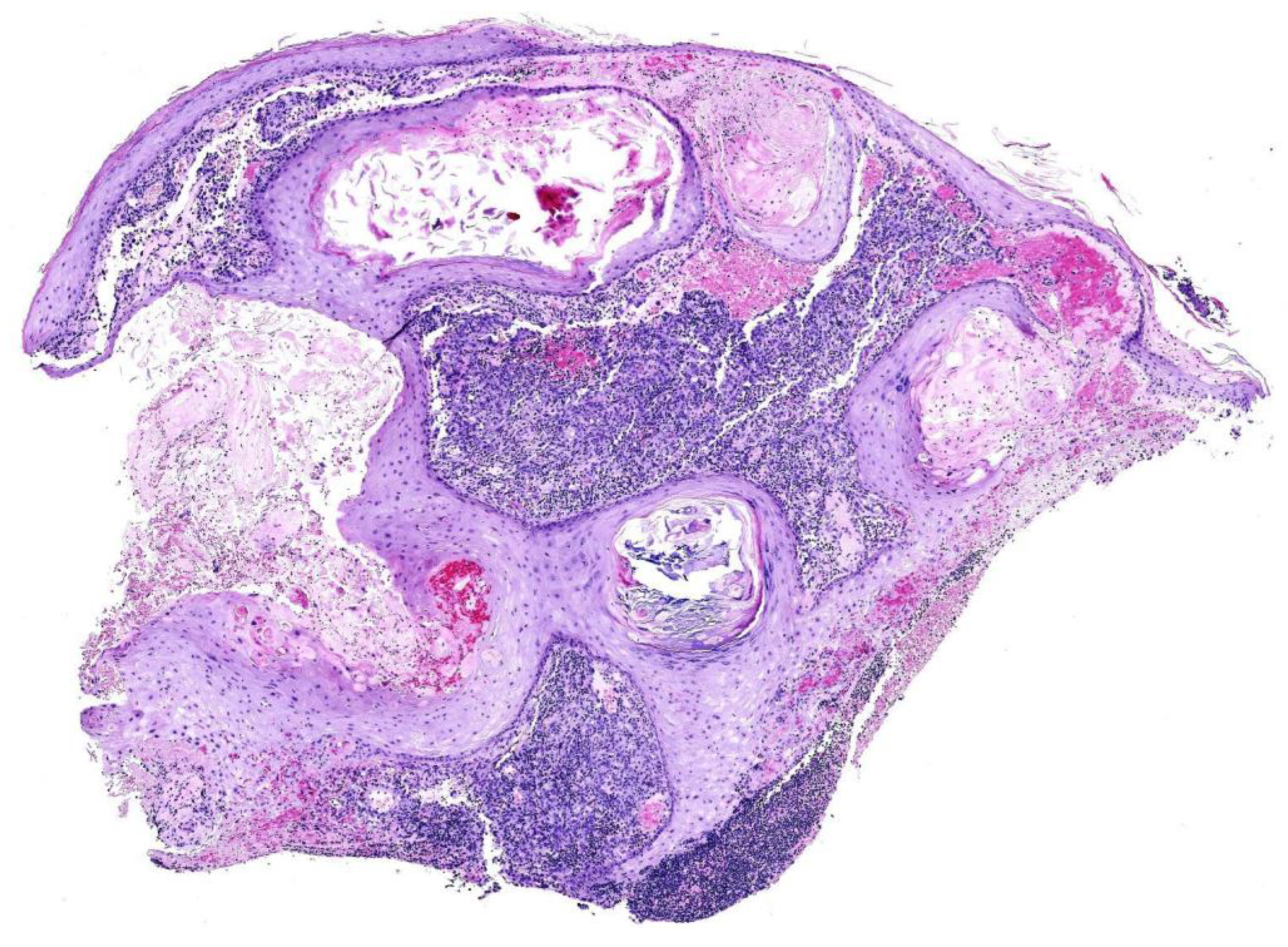

| Follicular mucinosis[35] | Angiosarcoma |

| Furunculosis | Basal cell carcinoma |

| Granuloma annulare [36] | Basosquamous carcinoma |

| Granulomatous folliculitis | Benign lymphangioendothelioma [29] |

| Granulomatous reactions (necrotizing or non-necrotizing) | Bowen disease |

| Granulomatous vasculitis | Breast carcinoma |

| Grover disease (personal case) | Kaposi sarcoma |

| Infections | Leukemia |

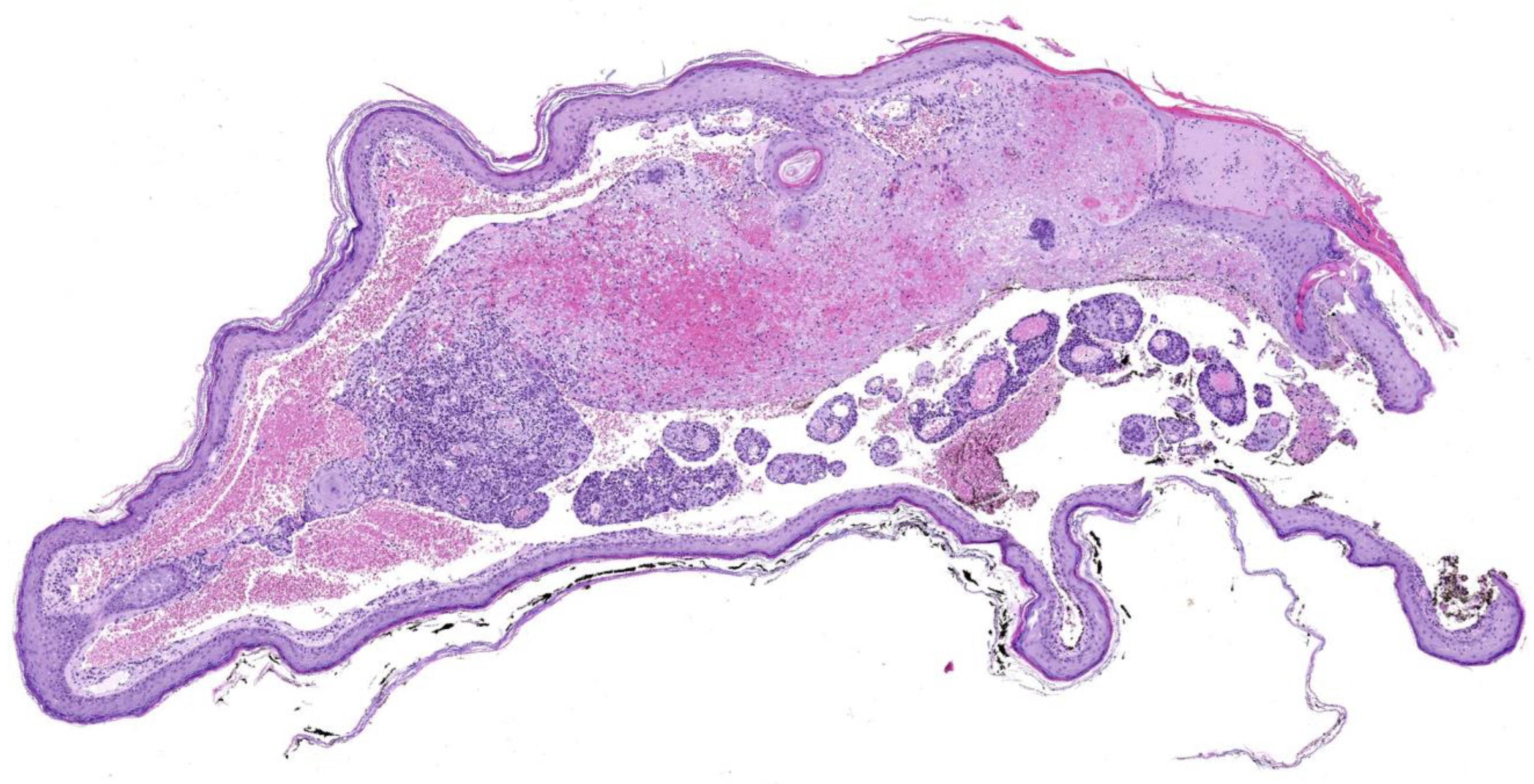

| Keloid | Lymphangiogenesis (pseudotumoral)[29] |

| Lichen planus | Lymphomas |

| Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus-morphea | Mastocytosis[41] |

| Lichen simplex | Metastases (from breast carcinoma and others) |

| Lichenoid dermatitis | Pseudolymphoma |

| Linear IgA dermatosis | Rosai-Dorfman disease |

| Lupus erythematosus[37] | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Milia | Syringoid eccrine carcinoma[28] |

| Mucinosis | Tufted Angioma[30] |

| Nodular solar degeneration | |

| Palpable purpura | |

| Pityriasis rosea (atypical)[38] | |

| Prurigo-like eruption | |

| Psoriasis | |

| Reactive perforating collagenosis | |

| Rosacea | |

| Sarcoidosis | |

| Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia[39] | |

| Vitiligo[40] | |

| Xanthoma[39] |

4. Conclusions

5. Future Directions

Acknowledgments

References

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, Brunetti G, Ruocco V. Wolf’s isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29(2):237–40.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. Br Med J. 1955 Nov;2(4948):1106–9.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, Filioli FG. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995 May;34(5):341–8.

- Happle R, Kluger N. Koebner’s sheep in Wolf’s clothing: does the isotopic response exist as a distinct phenomenon? Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2018;32(4):542–3.

- Sanchez DP, Sonthalia S. Koebner Phenomenon. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025; [cited 2025 Feb 8].Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553108/.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Piccolo V, Brunetti G, Guerrera LP, Wolf R. The immunocompromised district in dermatology: A unifying pathogenic view of the regional immune dysregulation. Clinics in Dermatology. 2014 Sep;32(5):569–76.

- Jenkins AM, Skinner D, North J. Postherpetic isotopic responses with 3 simultaneously occurring reactions following herpes zoster. Cutis. 2018 Mar;101(3):195–7.

- Schmidt AP, Tjarks BJ, Lynch DW. Gone fishing: a unique histologic pattern in cutaneous angiosarcoma. Cutis. 2018 Apr;101(4):270–2.

- Kuet K, Tiffin N, McDonagh A. An unusual eruption following herpes zoster infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44(2):197–9.

- Ji Y-Z, Liu S-R. Koebner phenomenon leading to the formation of new psoriatic lesions: evidences and mechanisms. Bioscience Reports. 2019 Dec;39(12):BSR20193266.

- Lo Schiavo A, Ruocco E, Russo T, Brancaccio G. Locus minoris resistentiae: An old but still valid way of thinking in medicine. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32(5):553–6.

- Zuehlke RL, Rapini RP, Puhl SC, Ray TL. Dermatitis in loco minoris resistentiae. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1982 Jun;6(6):1010–3.

- SAGHER F, LIBAN E, KOCSARD E. SPECIFIC TISSUE ALTERATION IN LEPROUS SKIN: VI. “Isopathic Phenomenon” Following BCG Vaccination in Leprous Patients. AMA Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology. 1954 Nov;70(5):631–9.

- Lewandowsky F, Lutz W. Ein Fall einer bisher nicht beschriebenen Hauterkrankung (Epidermodysplasia verruciformis). Arch f Dermat. 1922 Oct;141(2):193–203.

- Ghosh S, Jain VK. “Pseudo” Nomenclature in Dermatology: What’s in a Name? Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58(5):369–76.

- Berthelot C, Dickerson MC, Rady P, He Q, Niroomand F, Tyring SK, et al. Treatment of a patient with epidermodysplasia verruciformis carrying a novel EVER2 mutation with imiquimod. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2007 May;56(5):882–6.

- Happle: The Renbok phenomenon: an inverse Kobner... - Google Académico [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 9]. Available from: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Eur%20J%20Dermatol&title=The%20Renb%C3%B6k%20phenomenon:%20An%20inverse%20K%C3%B6ebner%20reaction%20observed%20in%20alopecia%20areata&author=R%20Happle&author=P%20Van%20Der%20Steen&author=C%20Perret&volume=1&publication_year=1991&pages=39-40&.

- Ovcharenko Y, Litus O, Khobzey K, Serbina I, Zlotogorski A. Inverse Koebner reaction observed in alopecia areata: the Renboek phenomenon. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2013 May.

- Rahman S, Daveluy S. Pathergy Test. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025; [cited 2025 Feb 9].Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558909/.

- Hudson CP, Hanno R, Callen JP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma in a site of healed herpes zoster. Int J Dermatol. 1984 Aug;23(6):404–7.

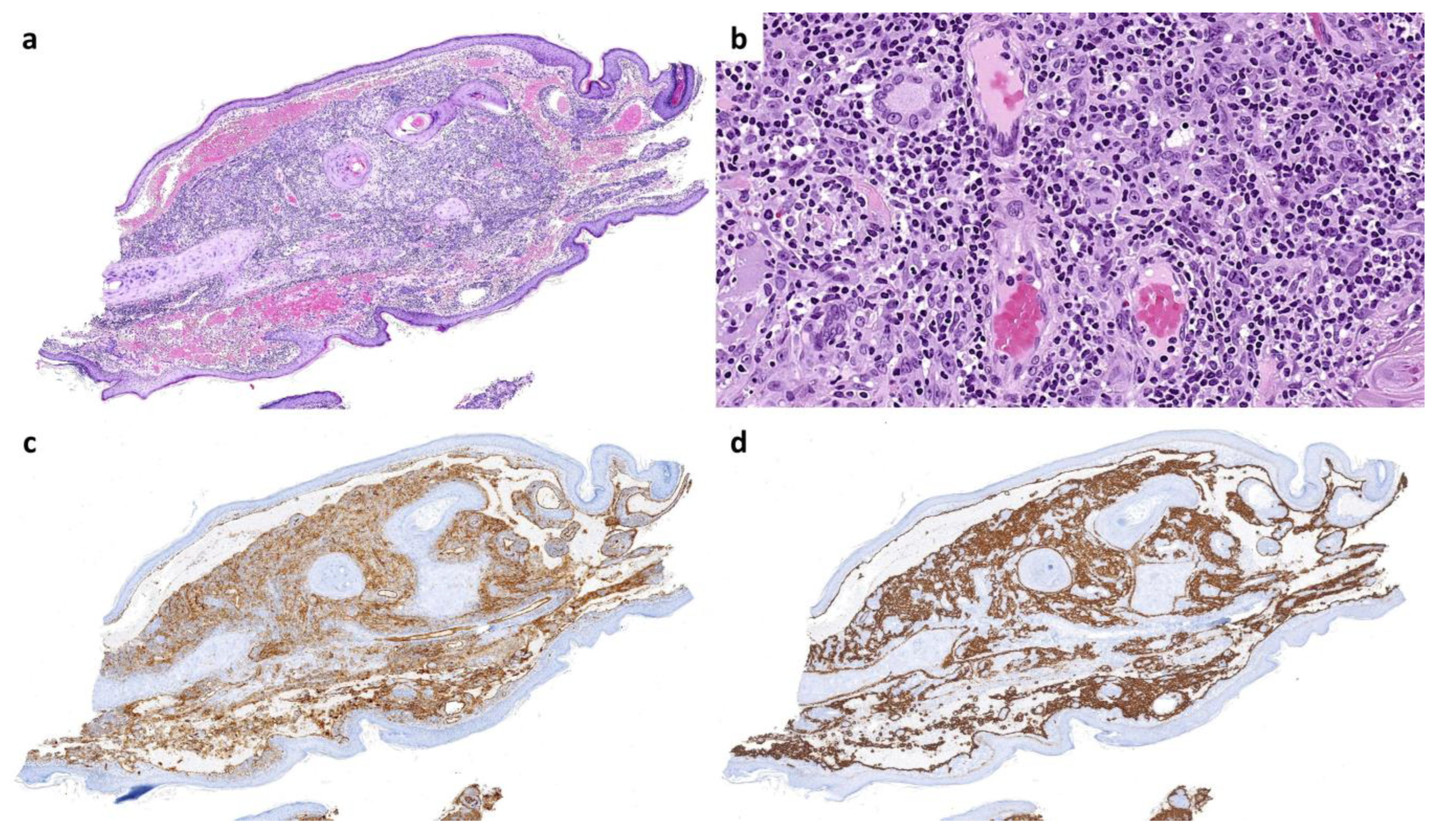

- Kwon CW, Stephens DM, Gilmore ES, Tausk FA, Scott GA. Cutaneous Pseudolymphoma Arising as Wolf’s Post-Herpetic Isotopic Response. JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Nov;153(11):1198–200.

- Sanchez-Salas, MP. Appearance of comedones at the site of healed herpes zoster: Wolf’s isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 2011 May;50(5):633–4.

- Elgoweini M, Blessing K, Jackson R, Duthie F, Burden AD. Coexistent granulomatous vasculitis and leukaemia cutis in a patient with resolving herpes zoster. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011 Oct;36(7):749–51.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Stutz N, Kaddu S, Weenig RH, Kutzner H, et al. Pseudolymphomatous cutaneous angiosarcoma: a rare variant of cutaneous angiosarcoma readily mistaken for cutaneous lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007 Aug;29(4):342–50.

- Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers W, Borghi S, Reichel M. Verrucous angiosarcoma of the skin: a distinct variant of cutaneous angiosarcoma. Histopathology. 1998 Jun;32(6):556–61.

- Ise M, Tanese K, Adachi T, Du W, Amagai M, Ohyama M. Postherpetic Wolf’s isotopic response: possible contribution of resident memory T cells to the pathogenesis of lichenoid reaction. Br J Dermatol. 2015 Nov;173(5):1331–4.

- G. El Baassiri M, Dosh L, Haidar H, Gerges A, Baassiri S, Leone A, et al. Nerve growth factor and burn wound healing: Update of molecular interactions with skin cells. Burns. 2023 Aug;49(5):989–1002.

- Wang T, Zhang M, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Zhang S, Qu T, et al. Wolf’s Isotopic Response after Herpes Zoster Infection: A Study of 24 New Cases and Literature Review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019 Oct;99(11):953–9.

- Schnebelen AM, Page J, Gardner JM, Shalin SC. Benign lymphangioendothelioma presenting as a giant flank mass. J Cutan Pathol. 2015 Mar;42(3):217–21.

- Cai Y-T, Xu H, Guo Y, Guo N-N, Li Y-M. A Case Report on Acquired Tufted Angioma with Severe Pain after Healed Herpes Zoster. Chin Med J (Engl). 2018 Oct;131(19):2378–9.

- Kim YJ, Kim SK, Kim YC, Kang HY. Actinic Granuloma Developed in a Herpes Zoster Scar. Annals of Dermatology. 2007 Mar;19(1):35–7.

- Melgar E, Henry J, Valois A, Dubois-Lacour M-B, Truchetet F, Cribier B, et al. [Extra-facial Lever granuloma on a herpes zoster scar: Wolf’s isotopic response]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2018 May;145(5):354–8.

- Lee HJ, Ahn WK, Chae KS, Ha SJ, Kim JW. Localized chronic urticaria at the site of healed herpes zoster. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999 Mar;79(2):168.

- Xv L, Wang B, Zhu Q, Zhang G. A Case of Isotopic Response Presented with Eosinophilic Pustular Folliculitis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2023;16:1749–52.

- Blakey BL, Gratrix ML. Reactive benign follicular mucinosis: a report of 2 cases. Cutis. 2012 Jun;89(6):266–8.

- Rademaker R, van Dalen E, Ossenkoppele PM, Knuiman GJ, Kemme SM. [Granuloma annulare after herpes zoster: Wolf’s isotopic response]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2021 Mar;165:D5344.

- Darsha A, Oldenburg R, Hinds B, Paravar T. A crack in the armor: Wolf isotopic response manifesting as cutaneous lupus. Dermatol Online J. 2022 Dec;28(6). [CrossRef]

- Ustuner P, Balevi A, Ozdemir M, Türkmen İ. Atypical pityriasis rosea presenting with a herald patch lesion on the healed site of herpes zoster: Wolf’s isotopic response. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26(1):102–3.

- Jaka-Moreno A, López-Pestaña A, López-Núñez M, Ormaechea-Pérez N, Vildosola-Esturo S, Tuneu-Valls A, et al. Wolf’s Isotopic Response: A Series of 9 Cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012 Nov;103(9):798–805.

- Cheng J-R, Mao H, Wang Y-J, Hui H-Z, Zheng J, Shi B-J. Postherpetic Vitiligo: A Wolf’s Isotopic Response. Indian J Dermatol. 2024;69(2):195–6.

- Sarsik S, Soliman SH, Elhalaby RE. Unusual presentation of telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans at the site of healed herpes zoster; Wolf’s isotopic response. Australas J Dermatol. 2023 Aug;64(3):e237–40.

| Term | First described | Definition & *interesting facts | Example |

| Koebner isomorphic phenomenon [4,5] | H Koebner, 1872 | Development of lesions from an existing cutaneous disease in previously healthy skin that has undergone non-specific injury, which can be mild. This disease may appear in locations where it typically does not occur. | Psoriasis lesions developing on surgical scars in a patient with underlying psoriasis. |

| Wolf isotopic response [2,3] | R Wyburn-Mason, 1955; refined by R Wolf, 1995 | Appearance of new skin lesions at the site of a previously healed, unrelated skin disease. | Comedones appearing exactly at the site of a previously healed herpes zoster. |

| Locus minoris resistentiae [11,12] | RL Zuehlke, 1982; | Areas of the body that are more vulnerable than others to suffer some pathologic conditions. *Its origins trace back to ancient myths, such as Achilles’ heel or Siegfried’s shoulder. |

Eczema appearing in skin previously damaged by surgery or burns. |

| Isopathic phenomenon [13] | F Sagher, 1954 | The injection of specific or non-specific proteins triggers the development of a disease already present in the patient. | In leprous patients, the cutaneous injection of several substances provokes changes typical of lepromatous leprosy. Conversely, in healthy individuals, the same injections cause only nonspecific inflammatory reaction. Similar reactions can be triggered by insect bites. |

|

Pseudoisomorphic response (pseudo-Koebner) [14,15,16] |

Unknown. First examples in literature from F Lewandowsky, W Lutz, 1922 | Spread of a cutaneous infection along a line of previously damaged skin |

Lineal lesions in epidermodysplasia verruciformis. Commonly seen in warts and molluscum contagiosum |

| Renboek/Renbök phenomenon (inverse or reverse Koebner phenomenon) [17,18] | R Happle, 1991 |

Disappearance of an existing skin condition following the onset of a new dermatosis at the same site. * The term “Renboek” or “Renbök” is not an eponym, but “Koebner” spelled backwards. |

A plaque of scalp psoriasis disappears as a patch of alopecia areata develops in the same location. |

| Pathergy [19] | Blobner, 1937 | A minor trauma on healthy skin induces non-specific cutaneous lesions, often rich in neutrophils. | Frequently seen in pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet’s syndrome or Beçet’s disease |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).