1. Introduction

Establishing the cause of an aviation incident or accident, to prevent it from re-occurring in the future, is the core goal of any aviation safety occurrence investigation and analysis. Hereafter, aviation accidents will be considered a subset of aviation incidents. Conventionally, whenever an investigation is deemed necessary in the event of an aviation incident or accident, the primary source of information is usually the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) and Flight Data Recorder (FDR) devices [

1]. Data from these two devices is vital in giving an account of what was happening within the cockpit and the input to the aircraft received from the pilot, respectively, minutes before and at the time of the incident. However, retrieving these two devices can take months or even years and in the worst case, the devices get severely damaged during or after the incident making the data irretrievable [

2]. In such cases, where the data on the devices does not give conclusive findings or is not readily available for the investigations to start, the experts often divert their attention to other sources which can include eyewitnesses, pilot reports, air traffic controllers, satellite images, radar information, damaged aircraft components, and weather stations readings at the time of the incident [

3]. This gathered information is often prepared and presented as a narrative describing the series of events and conditions under which the incident/accident occurred. This information is then analysed by experts to establish the likely cause of the incident [

4], allowing them to suggest possible measures that can deter such incidents from happening again.

However, this entire process is time-consuming, and in the event of a design flaw, until the cause is established, and a preventative measure designed and implemented, the lives of passengers flying with such an aircraft model remain at risk. As an example, the flaw in the design of Boeing 737 MAX’s Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) feature which in certain circumstances counteract the pilots’ input caused two fatal accidents including the crash of Lion Air (JT610) [

5] flight followed, five months later, by Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302. Both aircraft crashed a few minutes after taking-off killing all 189 and 157 people on board respectively [

5,

6]. If the cause of the Lion Air accident had been established quickly and acted upon appropriately, the ET-302 [

6] accident would likely have been avoided. With the aim of shortening aviation incident/accident investigation time, and allowing the quick establishment of the cause, researchers have proposed various natural language processing (NLP) and topic modeling-based approaches like Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA), Parallel Latent Dirichlet Allocation (PLDA), among others [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. These proposed schemes analyse and group aviation terms with related meanings or that are connected to a given phase of flight, field of aviation, flight conditions, and/or causes into related topics. Such approaches could help the investigation team to establish the area of concentration and consequently, lead to quick establishment of the causes.

However, no previous study has proposed a scheme for generating the probable causes given the analysis narrative of the pre-incident conditions and activities. To this end, this work builds and deploys a transformer-based model to predict the probable cause of an aviation incident from the initial analysis narrative. Transformer models like Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) [

12] and its variants [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] have demonstrated cutting-edge performance across various challenging NLP tasks. Since the analysis narratives often contain long textual paragraphs, The researchers hypothesized that the resulting model would produce enhanced performance if based upon recent studies on long-input transformers [

19,

20,

21,

22] which have revealed that increasing the Transformer’s input length positively correlates with model performance.

The training approach for the transformer model deployed in this work aligns with the fundamental principles of a language translation transformer. However, it deviates in that, instead of setting the masked input to the transformer’s decoder as the target language during training, it utilizes the target probable cause. Upon evaluation on the NTSB dataset, the model showcased the potential for transformers to accelerate aviation incident investigations by generating the probable causes based on the analysis narrative. The contribution of this study is two-fold:

A new generative model based on multi-head attention transformer is proposed and trained for generating the probable cause of an aviation incident when given as input the raw text narrative of series events before, during or after the accident. The model accepts both long and short input narratives which should expedite the investigation process enhance air transport safety.

Many aviation incident dataset have instances with analysis narratives but with no corresponding entry for the probable causes. This leads to eliminating many instances during model training and consequently leads to poor model performance in terms of generalization to new instances. With the ability to generate missing probable cause, instances with missing values can be retained, likely leading to better model performance and generalization.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents a review of prior related work followed by

Section 3 where a detailed description of the our approach is presented. In

Section 4 the findings of this study are presented. In

Section 5 a detailed discussion of the findings is presented, highlighting the contributions and limitations of our study and finally

Section 6 gives concluding remarks, highlighting the direction of future work.

2. Related Work

The utilization of machine learning and deep learning methods and techniques in aviation analysis and prediction has garnered increasing attention from aviation safety researchers. This interest is driven by objectives such as expediting aviation incident investigations, promptly determining the causes of incidents for swift mitigation of future occurrences, predicting incidents, and extracting knowledge to enhance air transport safety. This section delves into key prior studies that have employed AI-based techniques in alignment with aviation safety.

Burnett et al., [

23] trained four conventional ML classifiers, including Decision Trees, KNN, SVM, and ANN with back propagation for prediction of aviation injuries and fatalities. The authors employed a cross validation training approach with 10 folds and looked at how factors like pilots’ accumulated flight hours and age impacted the rate of injuries and fatalities. Experimental results revealed ANN to be superior for the task when evaluated on datasets sourced from Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) between 1975 and 2002 inclusive.

Nanyonga et al., [

24] utilized NLP and other AI to analyze text narratives, aiming to determine aircraft damage levels from safety incidents. Four learning models: Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Bidirectional LSTM (BLSTM), and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), Simple recurrent Neural Network (sRNN) and hybrid architecture models including GRU+LSTM, sRNN+BLSTM+GRU, etc, were assessed on 27,000 NTSB reports. Results indicated all models achieved over 87.9% accuracy, surpassing random guessing (25%) for a four-class problem.

Another study [

25], assessed the risk created by various anomalies in aviation events using of a hybrid classifier constituting proposed a hybrid model comprising a SVM and and several neural networks. The four-step method involved all events being categorized into five risk-level groups, followed by application of a SVM model to determine the link between textual event synopses and the resulting consequences. Next the hybrid model was trained to capture the correlations between contextual event attributes and risk-level groups. A fusion rule was then proposed to combine outcomes from the two models and finally, a stochastic-base decision tree was used to predict the risk level.

Both [

26] and [

27] deployed Bayesian inference-based techniques for aviation incident modeling and analysis. Study [

27] aimed to forecast aircraft safety incidents by employing an inventive statistical method. This method utilized Bayesian inferences and hierarchical structures to build learning models of varying complexities and goals. In contrast, [

26] focused on analyzing commercial aviation accidents spanning the period between 1982 and 2006, as documented by the NTSB. This second study proposed a four-phase approach to build a Bayesian network capable of capturing the relationship between the sequence of events that led to the accidents. The methodology encompassed creating a graphical representation for visualizing aviation accident events, forming a Bayesian network representation by amalgamating the graphical representations of all accidents, while accounting for the causal and dependent relationships between aircraft damage and personnel injury.

In their study [

13], trained and evaluated two models,

ResNet and simple RNN, to classify the phase of flight during which the incident happened. Various NLP-based techniques were sequentially deployed including word tokenization, punctuation, unwanted characters and stopword removal, lemmatization operations and

word2vec transformation of the unstructured textual analysis narratives extracted from the NTSB aviation incident investigation reports. The models recorded a classification accuracy of more than 68% on a 7-class classification problem.

In study [

28], Nanyonga et al., carried out a comparative study of two topic modeling analysis techniques: LDA and Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) regarding aviation accident reports. Using Coherence Value for performance evaluation the quality of generated topics was evaluated with LDA, displaying superior topic coherence and indicating its robustness in extracting semantic connections among words within topics. NMF, on the other hand, showcased exceptional performance in line with generating unique and detailed topics, facilitating a more targeted examination of particular aspects of aviation accidents.

Their study [

29] showcased an automated text classification approach, utilizing machine learning, that could enhance analysts’ efficiency by accurately categorizing “Occurrence” in aviation incident reports, thereby enabling more precise querying of reporting databases. Using a Random Forest algorithm to classify more than 45,000 textural reports, an accuracy of 80-93% was recorded based on the ICAO “Occurrence” Category. The authors also conducted text cleaning that encompassed use of standard NLP techniques including stemming, removal of irrelevant words and symbols like stop words, punctuation characters and other special symbols, and then deployed the

n-gram techniques including bi-gram, tri-gram, etc for feature extraction prior to passing the reports to the ML algorithm for classification.

Studies including [

30,

31,

32] deployed NLP-based techniques including topic modelling, and text classification, for information extraction from, and analysis of, aviation incident reports and have reported competitive results regarding causal factor analysis like human factors analysis, and aviation incident risk classification, aircraft damage classification, aviation report clustering and grouping, and many other AI-based tasks.

One research gap revealed in our literature review concerns attention-based transformers. Despite the attention-based transformer models achieving outstanding performance on various NLP tasks, including machine translation [

33,

34,

35], text summarization [

36,

37], text simplification [

38,

39], grammatical error correction [

40,

41] and question answering [

42], little-to-no attention has been paid to their deployment in the field of aviation safety to establish the likely causes of an aviation incident given the raw text analysis narrative. The work in this study aims to close this knowledge gap by proposing and training a transformer-based model for such tasks.

3. Proposed Approach

3.1. Dataset

Several aviation, and transport safety agencies, such as the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB), Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS), and the NTSB, actively gather and release reports detailing aviation incident investigations. This research utilized aviation incident reports provided by the NTSB. These reports, along with accompanying metadata, are available on the NTSB’s website in a variety of formats, such as monthly-published

.pdf documents,

.json files, or by querying individual reports through their online platform. A summarized version in

.csv format can also be obtained. For this study, the researchers focused on

.json files containing detailed incident investigations from the years 2001 to 2020. Importantly, the only included incidents where investigations that had been concluded, resulting in a dataset comprising 29,676 cases. From each report, the

analysisNarrative were extracted and

probableCause sections to facilitate model training and validation processes. Additionally, a comprehensive statistical analysis was carried out to assess the distribution of text lengths within these fields. It was found that the average length of the

analysisNarrative was 1,116 words, while the

probableCause field averaged 165 words, with standard deviations of 858.36 and 93.12, respectively. Further examination revealed that the shortest

analysisNarrative entry contained only 4 words, while the longest reached 36,544 words. In comparison, the

probableCause field ranged from 7 to 1,600 words.

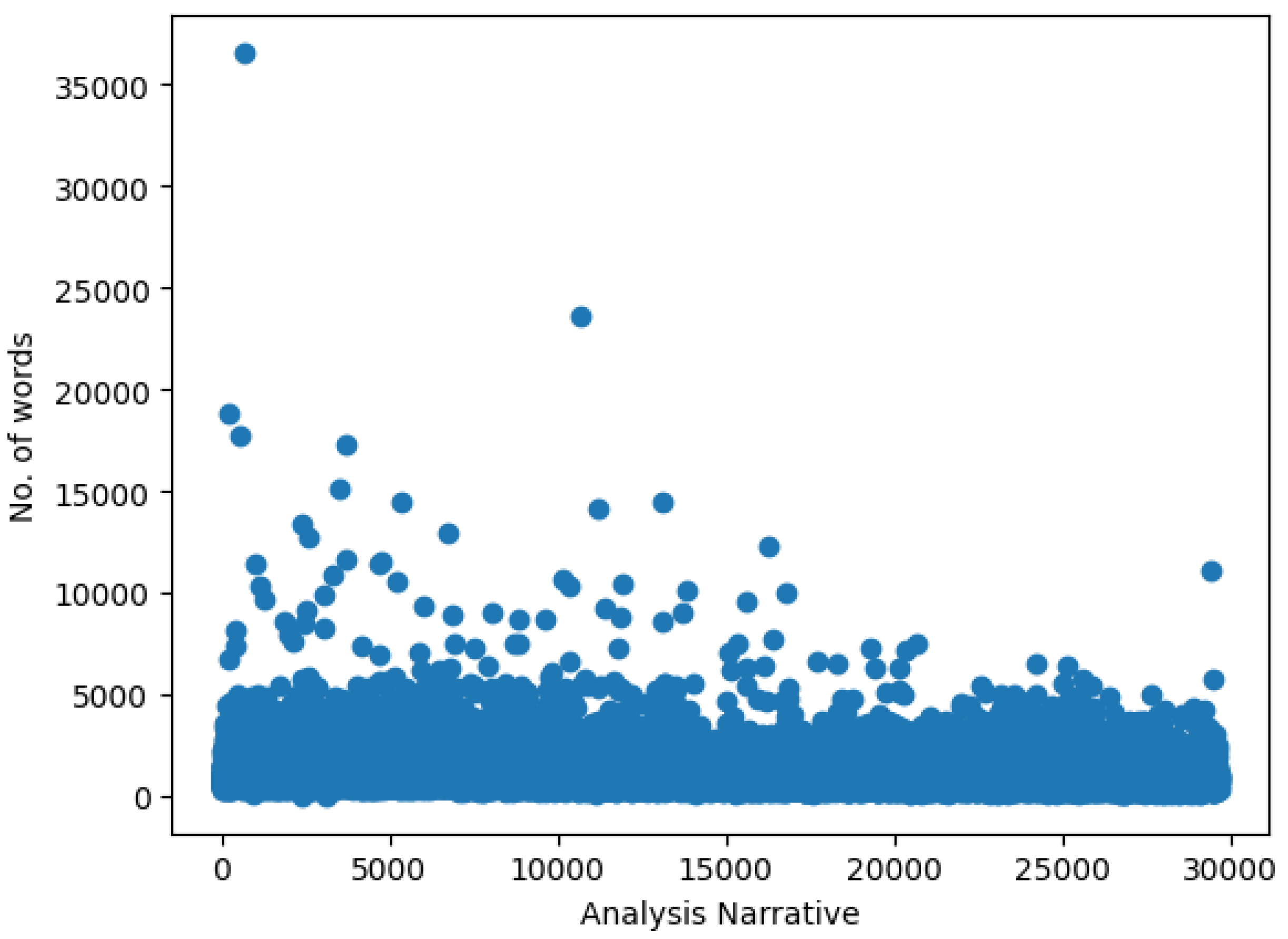

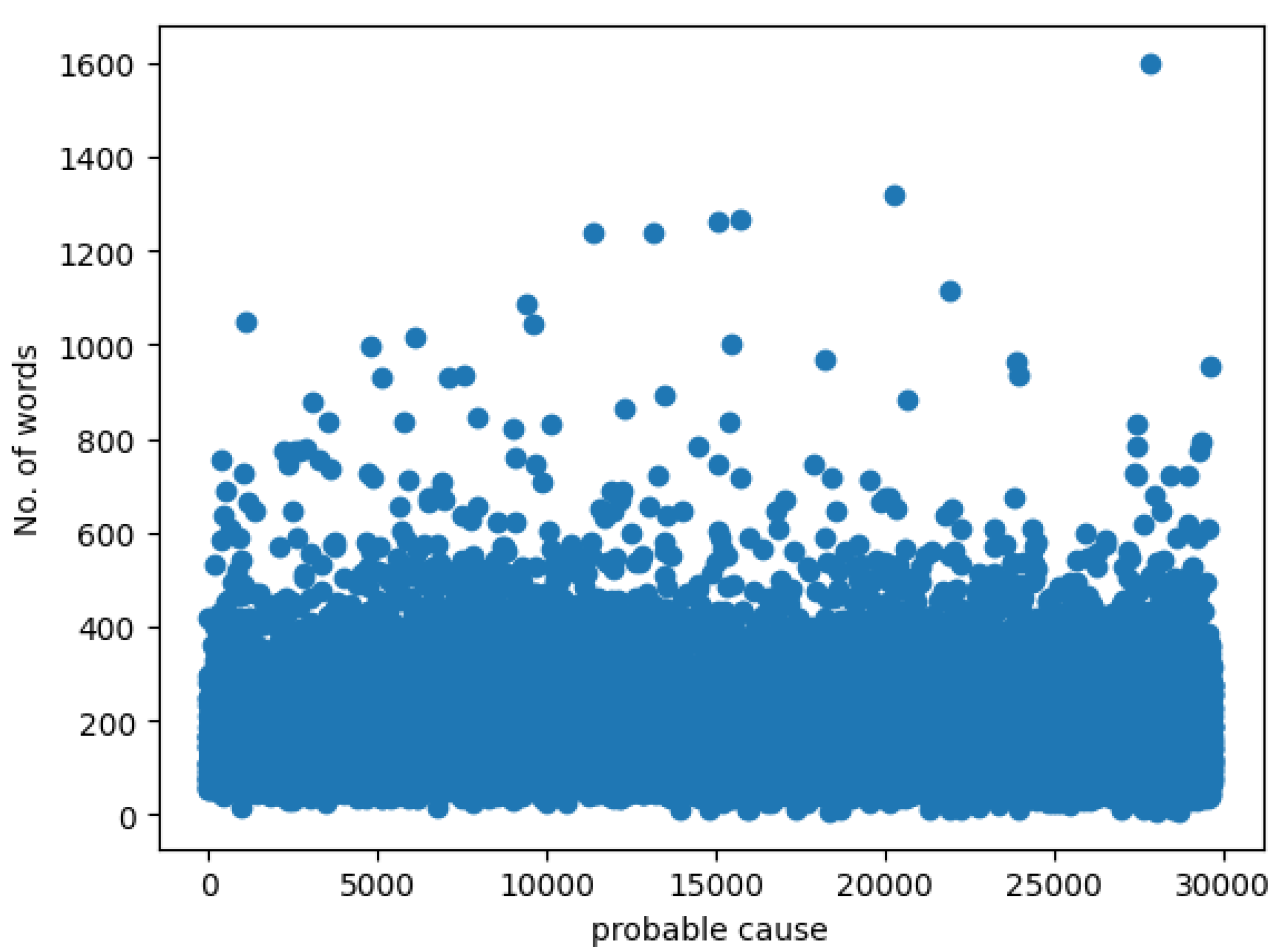

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 visually represent the distribution of text lengths for both the

analysisNarrative and

probableCause fields.

3.2. Data Pre-Processing

Data pre-processing involved removing HTML tags and urls, transforming wrongly-encoded characters; that is, characters encoded with the ASCII equivalent codes were decoded to their natural language characters. Also, reports whose analysisNarrative entries were longer than 10,000 words, and probableCause entries longer than 1,000 words, were treated as outliers and discarded for this study.

3.3. The Transformer

The Transformer architecture, introduced in study [

43], represented a revolutionary advancement in the NLP domain, yielding remarkable outcomes. Departing from traditional RNN models, the Transformer employs multi-head self-attention, enabling parallel processing and overcoming the limitations of sequential training inherent in conventional RNNs. This self-attention mechanism not only enhances computational efficiency but also captures intricate dependencies among various text components. As described by the authors, the attention process involves associating a given query, Q, with key(K)-value(V) pairs for sequence generation. Within this framework, Q, keys K, V, and the prediction are expressed as vectors. The resulting sequence is computed through a weighted summation of the V entries, with each value’s weight determined by a passing a scaled-dot product of Q and K vectors through a softmax function as depicted in Eq.(

1).

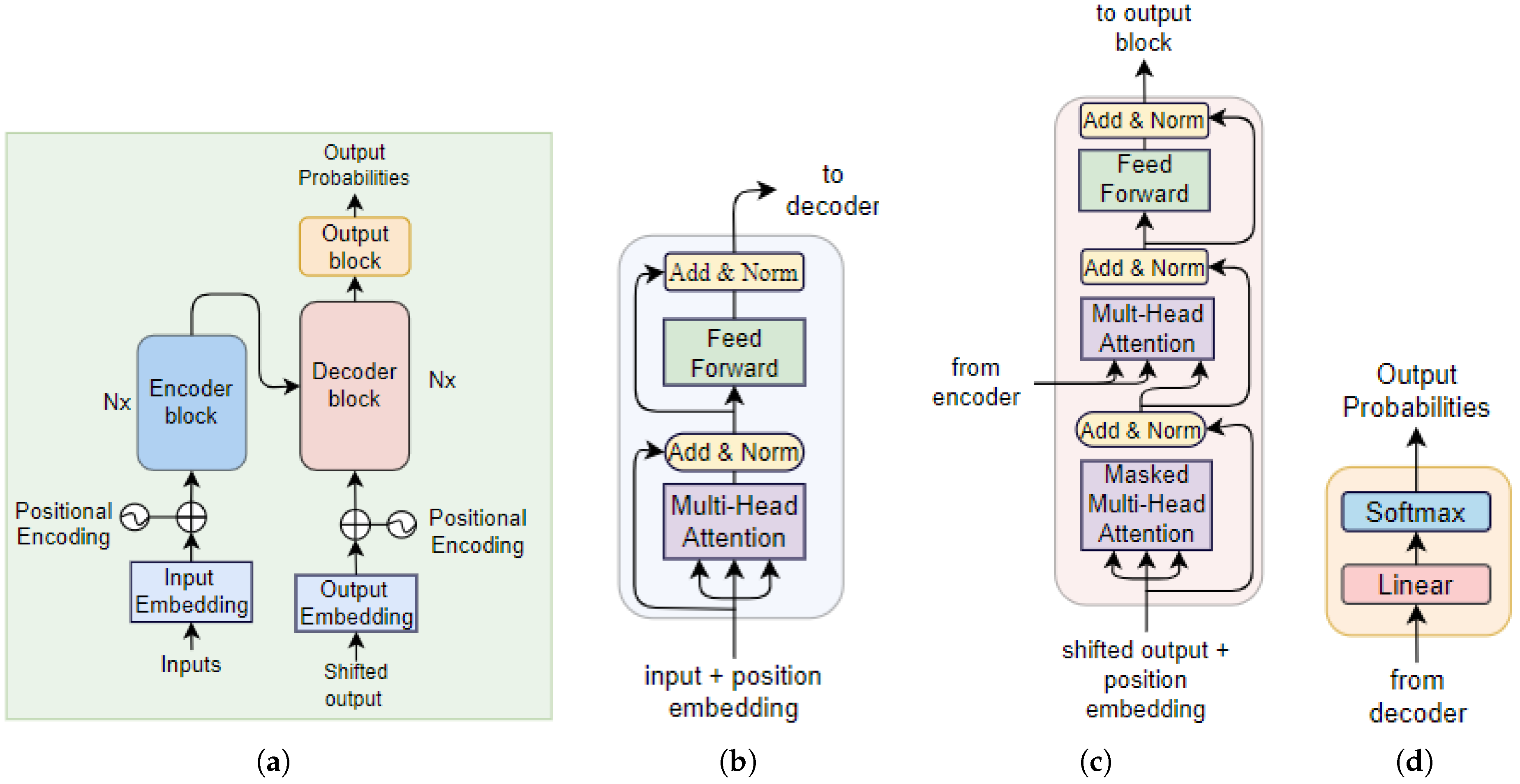

Figure 3 shows the architecture of the transformer model and the architectural components of its encoder, decoder and output blocks.

Where;

.

In order to facilitate concurrent processing, the multi-head self-attention mechanism utilizes several linear projections of Q, K, and V, each mapped to dimensions

,

and

respectively. These parallel operations generate outputs within the

-dimensional space, which are combined and mapped again to derive the ultimate V entries. This approach results in a model capable of simultaneously attending to information across many representational vector subspaces at various locations. The multi-head self-attention mechanism, featuring

p heads, is defined as presented in Eq.(

2).

Given that

3.4. Experimental Setup

For our experiments, the model constituted 8 encoder and decoder layers and its embedding dimension was set to 1024 to enable long inputs. For multi-head attention, 8 attention heads were employed, while a dropout of 0.1 was used at each Batch normalization layer, and Feed-forward layer for regularisation and to prevent model over-fitting. In addition, the input sequence length was set to 1024 and the dimension of the Feed-Forward network’s inner-layers was set to 2048, both the “analysisNarrative” and“probableCause”’s vocabulary sizes were set to 100,000.

The model was trained on

of the dataset while the remaining

was used for testing following study [

44] in which this split ratio produced the best prediction results. Training was done for 50 epochs using a learning rate of

with Adam optimizer, betas were set to

, epsilon set to

, batch-size set to 64, and cross-entropy as the loss function.

3.5. Performance Metrics

To evaluate the quality of generated probable cause, three metrics commonly used tasks involving natural language generation problems such as text summarizing, machine translation, question answering and grammatical error correction are used in this study.

3.5.1. Bilingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU)

BLEU [

45] deploys an

n-gram based evaluation metric approach that is extensively utilized in Machine Translation assessment. It is precision-centric and assesses the degree of overlap between n-grams from the target and generated texts. This overlap is insensitive to word position, except for

n-gram term associations. However, BLEU imposes a brevity penalty when the generated text is substantially shorter than the reference text. Besides Machine Translation, BLEU finds application in problems where the input and output use the same natural language, including grammatical error correction [

46,

47], summarization [

48,

49], and text simplification [

39,

50], which involves rewriting a sentence into one or more simpler sentences. The BLEU score can be computed using Eq.(

3) [

45].

where;

Brevity Penalty, calculated using Eq.(

4)

order i n-gram precision’s weight.

n-gram’s modified precision score of order i

maximum n-gram order to consider

3.5.2. Recall Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation (ROUGE)

ROUGE [

51] applies a definition similar to that of BLEU. However, unlike BLEU which emphasizes precision, ROUGE’s emphasis is on recall. ROUGE comes in three main versions [

52,

53]:

n-rouge, primarily examining

n-gram overlap (such as 2-rouge and 1-rouge for 2-grams, and 1-gram respectively);

L-rouge, which evaluates the Longest Common Text Sub-sequence; and

s-rouge, emphasizing skip grams. Like BLEU, ROUGE finds application in both machine translation and in problems where the input and output use the same natural language, including summarizing [

54,

55,

56], grammatical error correction [

53,

57], and text simplification [

58,

59,

60], which involves rewriting a sentence into one or more simpler sentences. For each of

rouge-1,

rouge-2 and

rouge-L, the precision, recall, and F-measure are calculated using Eqs.(

5), (

6), (

7) [

51].

where’

is the number of n-grams from the target probable cause matching with the predicated probable cause.

is the count of n-grams in predicted probable cause

is the count of n-grams in actual probable cause

3.5.3. Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA)

LSA [

61], presented in 1997 by Landauer and Dumais in [

62], calculates the semantic similarity between a reference sentence and the model’s generated sentence. It relies on pre-computed word co-occurrence counts from a large corpus. Employing the bag of words (BOW) approach, it treats word order as irrelevant. Unlike ROUGE and BLEU, LSA is lenient on variations in word choice, such as "hard" versus "difficult." In essence, LSA encodes sentences or documents into vectors using a bag of words technique. These vectors enable the computation of similarity metrics, such as cosine similarity, to assess the likeness between generated and target texts. Like BLEU and ROUGE, LSA has seen application in measuring the output quality of various natural language generation models including text summarizing, grammatical correction, translation, and text simplification [

63,

64,

65,

66,

67]. The cosine similarity between sequences,

and

, can be obtained by converting the sequences to numeric vectors,

and

, and then using Eq.(

8) for similarity calculation [

68].

4. Results

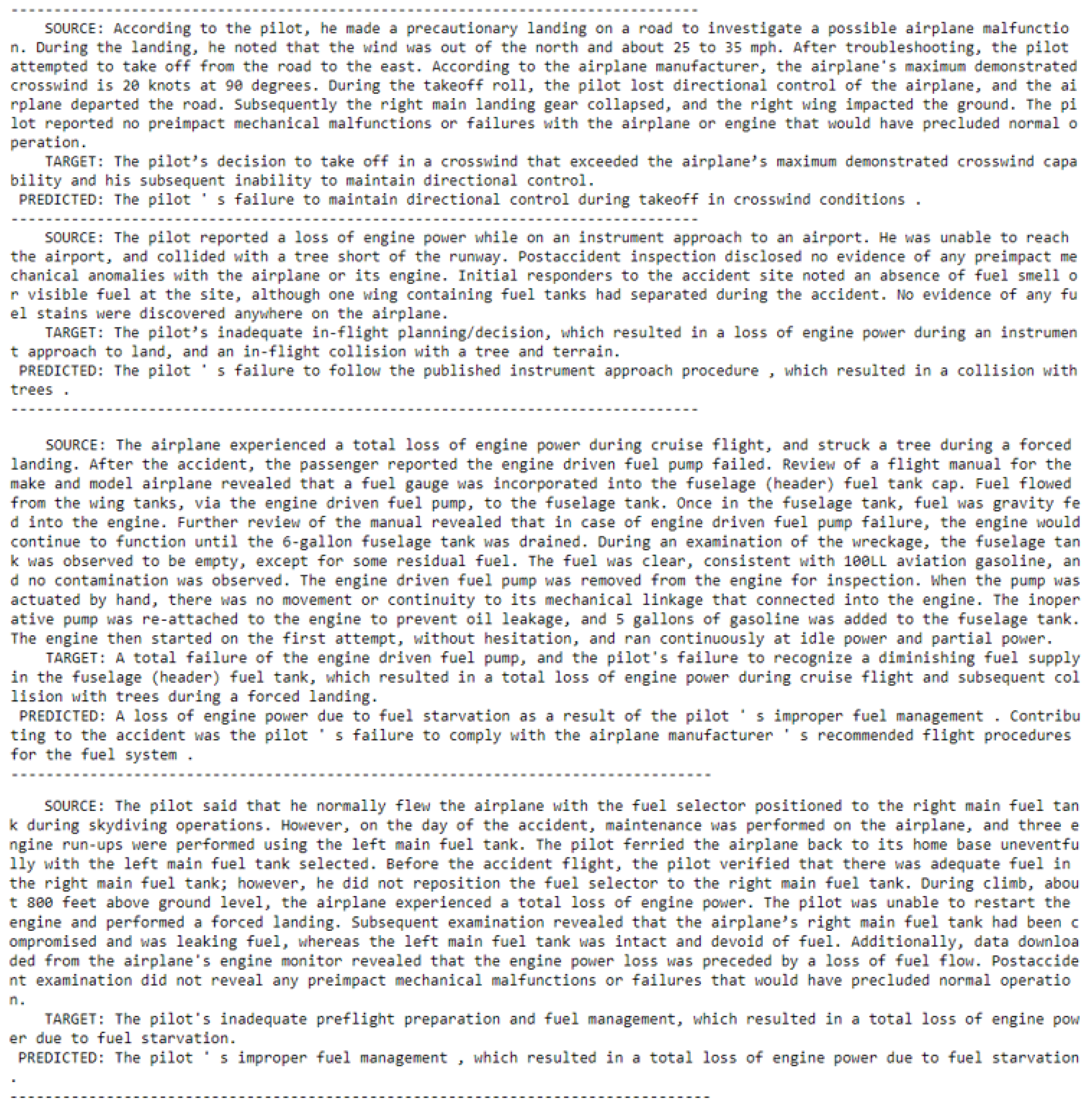

For model inference, instances from the test were fed into the model and it generated a probable main cause for each analysis narrative. The example of training cases are shown in

Figure 4, where random samples of analysis narratives from the test set are passed to the model. The model generated almost semantically perfect probable causes concerning each input narrative.

4.1. Model Performance Based on the BLEU Score

The BLEU Score was used to measure how closely the predicted probable cause matched the reference probable cause. For each pair of sentences, BLEU gives a value between 0 and 1, with 1 indicating a perfect match. The minimum n-gram order was set to 1 while N was set to 4 for this work. After a series of evaluations with various random samples of size 500 from the test set, in comparison with results from other metrics, the weight vector, w was set to .

For each instance in our test set, the BLEU score was computed, recording a mean score of

with a standard deviation of

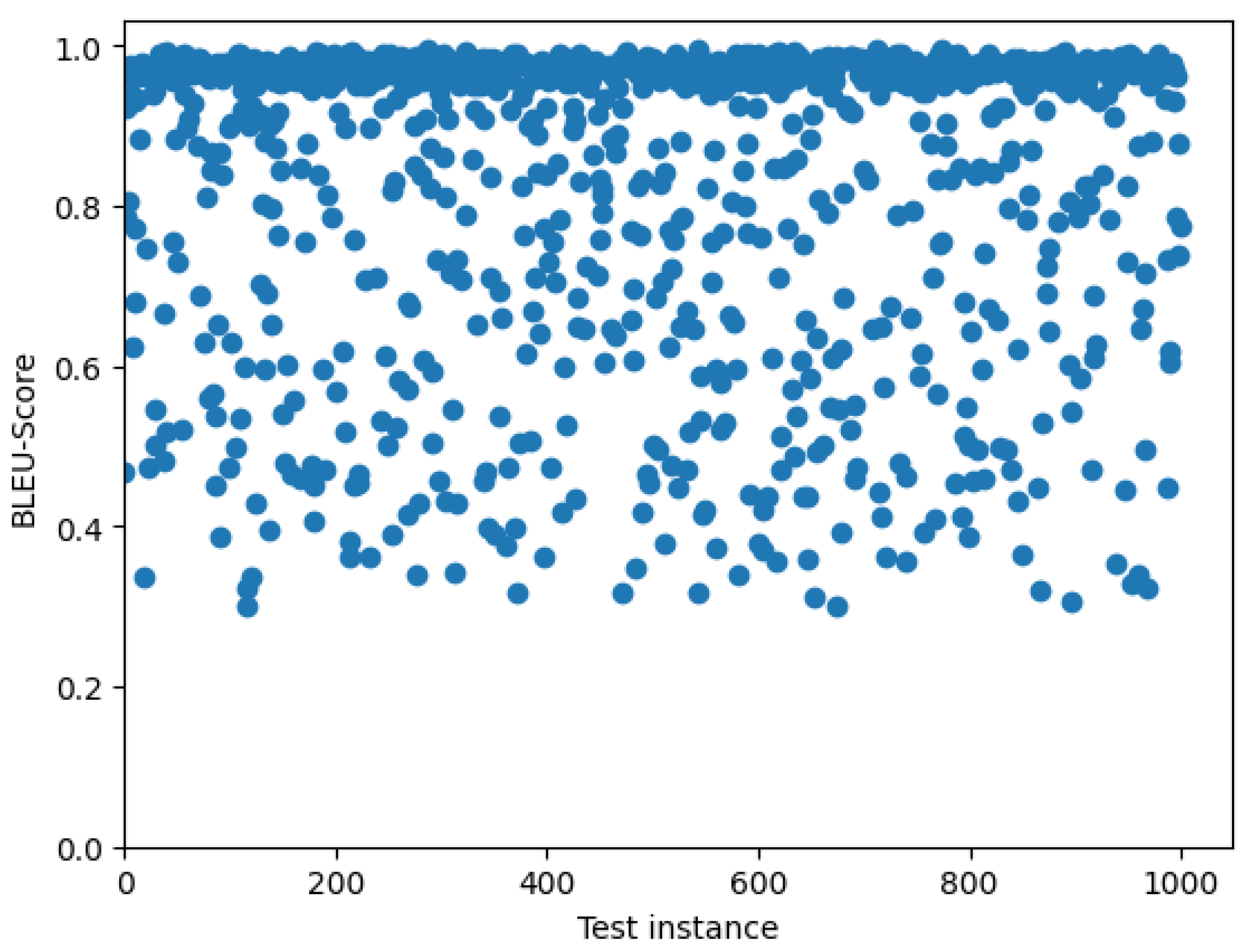

. A scatter distribution of the obtained BLEU scores between the first 1000 (probable cause, predicted probable cause) pairs is shown in

Figure 5.

4.2. Model Performance Based on the LSA Similarity Score

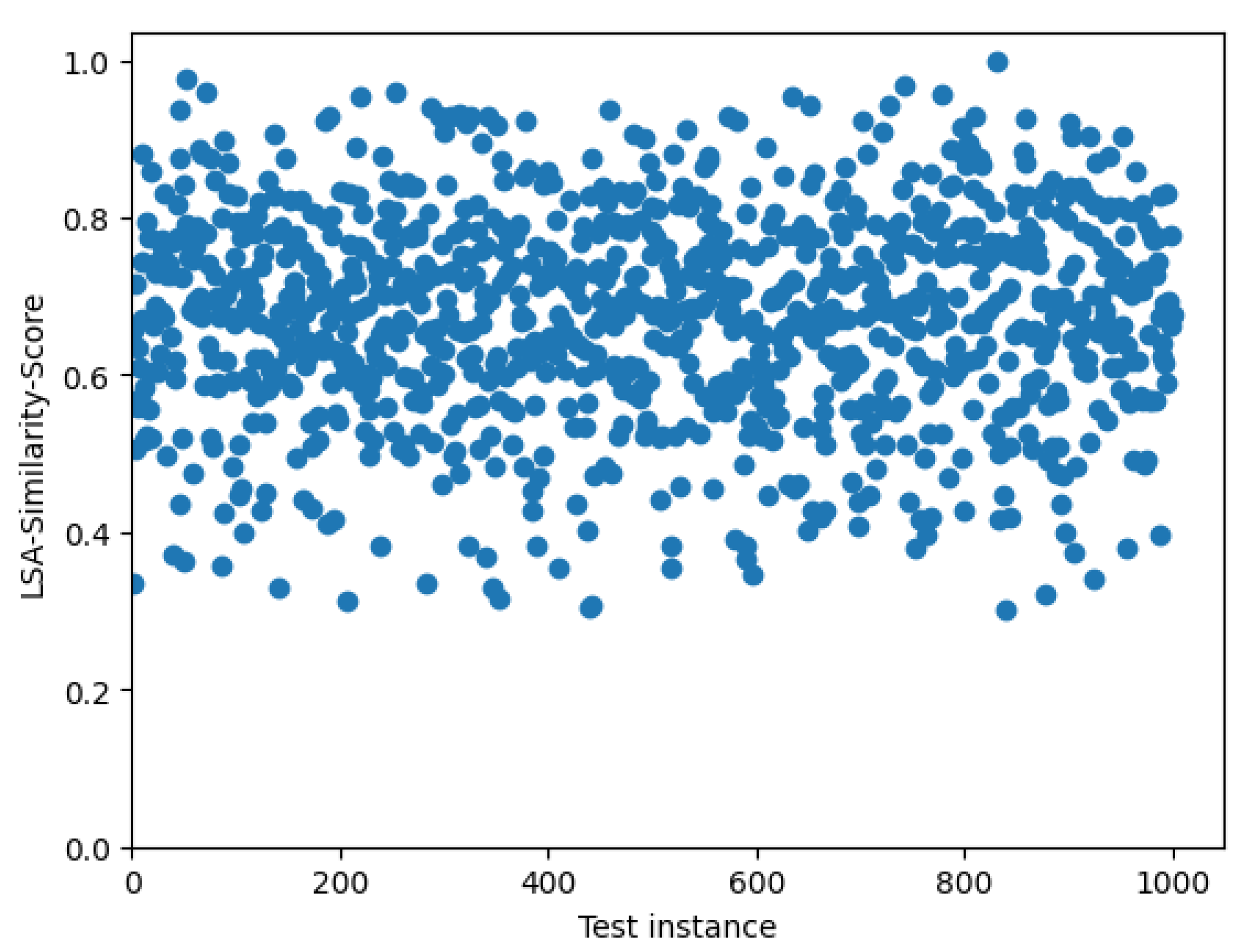

LSA Similarity gives the semantic similarity between vector representations of the output probable cause and target probable cause. It represents the semantic similarity rather than lexical similarity. A high similarity score implies that the sequences have closer meanings. Like the case of BLEU scores, for each instance in the test set obtained the (probable_cause, predicted_probable_cause) pair.

Each component of the pair was then converted into its numeric vector representation using Google’s pretrained Universal-Sentence-Encoder Version 4, which is the latest version at the time of writing this paper. Universal-sentence-Encoder models were introduced by Google Researchers in study [

69] where the cosine similarity was deployed consequently placing vector embeddings of semantically similar words close to each other. The pretrained Universal-Sentence-Encoder model used in this work can be downloaded from the TensorFlow hub

1. Our model recorded a mean LSA similarity score of

with a standard deviation of

. A distribution of the obtained Similarity scores is visualized in

Figure 6

4.3. Model Performance Based on the ROUGE Scores

For ROUGE Scores, this study considered n-rouge(rouge-1, rouge-2) and L-rouge(rouge-L). These scores measure the overlap of n-grams between the candidate and reference sentences. Rouge-1 gives score from unigrams, rouge-2 gives score from bi-grams, while rouge-L gives score from the longest common sub-sequence. Higher scores indicate better overlap between the sentences.

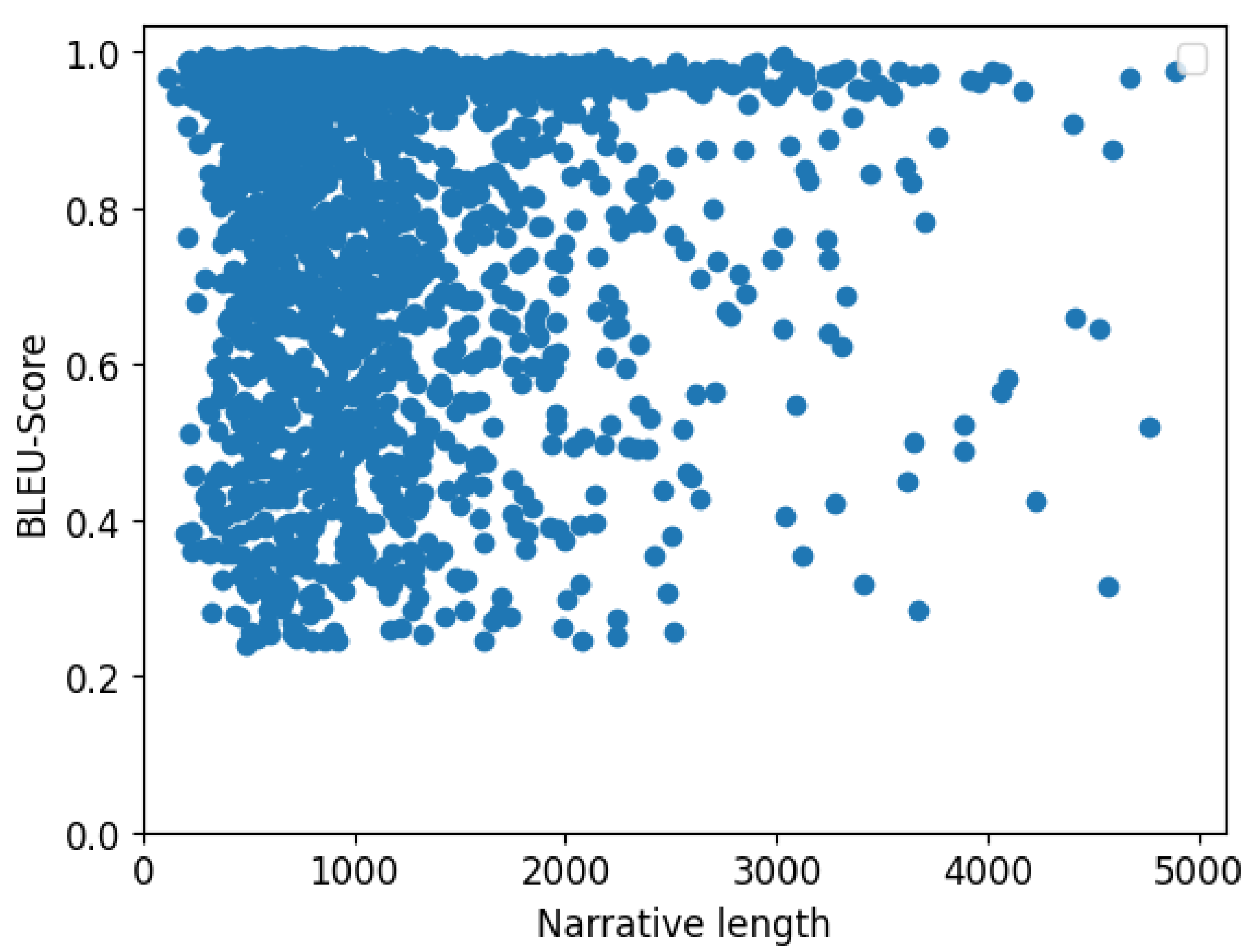

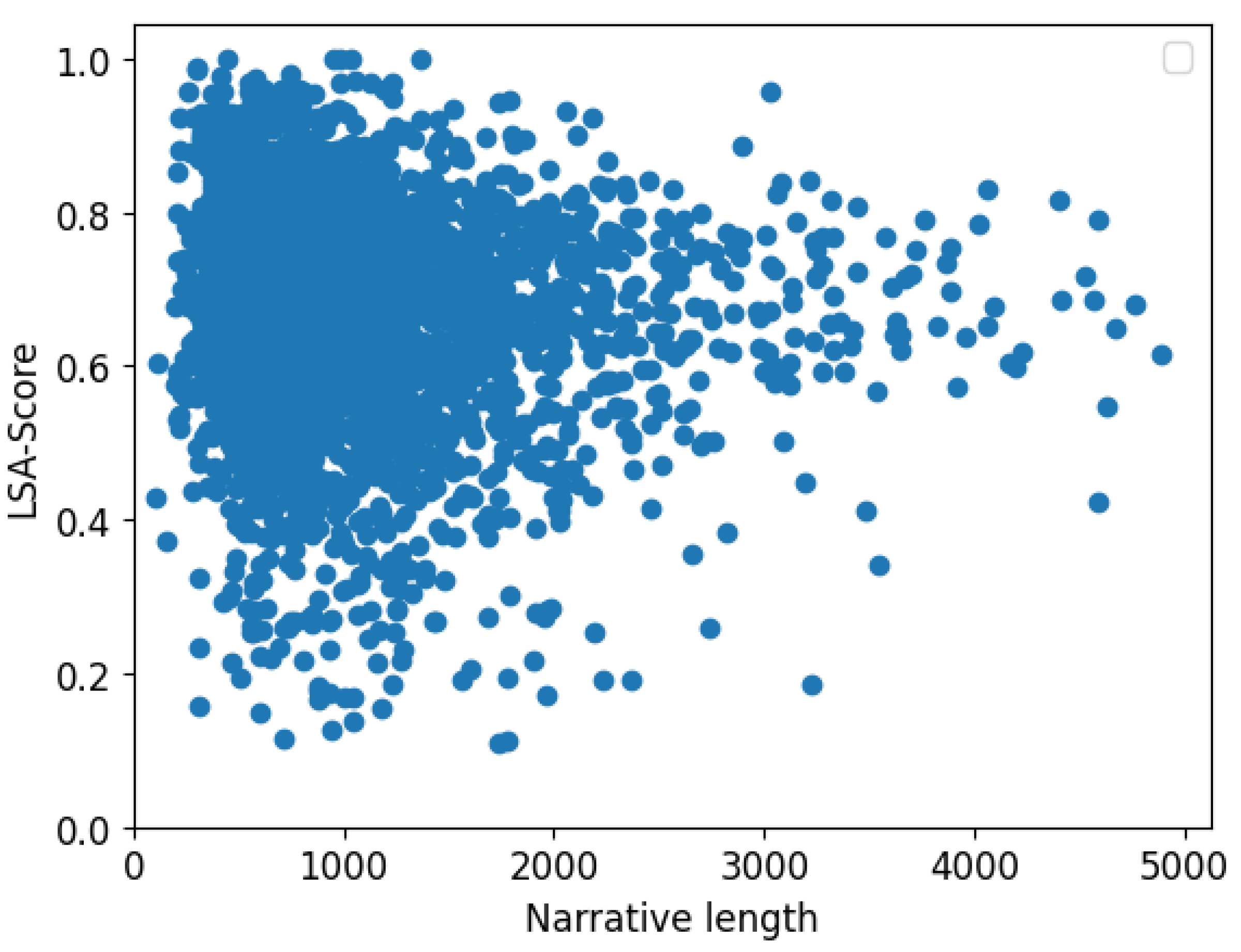

4.4. AnalysisNarrative Length Vs BLEU/LSA Scores

Further investigations were carried out on how the length of the input analysis narrative impacted the model’s output in terms of the BLUE and LSA similarity scores. The results revealed that the analysis narrative length had no direct correlation with the model’s BLUE score as shown in

Figure 7. On the other hand, the LSA similarity score shows no correlation with the length of the input analysis narrative for shorter inputs. However, it tends to converge to the mean score as the length of the analysis pattern increases as shown in

Figure 8. This finding emphasizes the researchers’ hypothesis which stated that working with long input sequences would enhance the model’s predictive performance. This also emphasises the finding of prior studies on long-input transformers including [

19,

20,

21,

22] which revealed that increasing the Transformer’s input length positively correlates with model performance.

5. Discussion

Having the ability to predict the probable causes of an aviation incident can greatly expedite the investigation process. The results from this study revealed that a multi-head attention-based transformer model is a tool for solving this problem. However, although the model recorded commendable results across all metrics, by their formula, the LSA similarity score is more reliable compare to BLEU and ROUGE metrics. This is because the model’s output and reference sentence can constitute a different set words for the same semantic content. Since the LSA similarity score computes the overall semantic similarity between the sentences, it will more likely produce a high score if the two sentences are similar and vice-versa. On the other hand, the BLEU score requires that the weight vector, w for each n-gram is manually determined. This means that the final BLEU score greatly depends on the accuracy of the values of w which requires human expert and if wrongly determined can lead to misleading results. Also, the computation of BLUE and ROUGE scores like the uni-gram, bi-gram, etc, depend on the overlap of words between the reference and predicted sentence, that is, observed probable cause and predicted probable cause for this study.

For instance, considering the output in the screenshot in

Figure 9, the reference probable cause as given in the dataset is:

“The mechanic’s improper maintenance of the main transmission aft pinion nut and belt drive system, which resulted in the uncoupling of the tail rotor driveshaft and the subsequent loss of helicopter control”.

While the model’s prediction given the same analysis narrative, is:

“The failure of the main rotor drive belts due to a loss of belt tension on the main rotor drive system as a result of maintenance personnel s failure to properly secure the - nut and the helicopter s main rotor drive belts.”

Although the semantic meanings of the two narratives are close and would both draw the incident investigator’s attention to the same component and attribute the failure to the maintenance personnel’s not properly securing the nut and belt drive system, BLEU scores differed across different weight vector values as shown in

Table 2.

On the other hand, the ROUGE scores were rouge-1: precision=0.476, recall=0.606, Fmeasure=0.533, rouge-2: precision=0.146, recall=0.188, Fmeasure=0.164 and rouge-L: precision=0.310, recall=0.394, Fmeasure=0.347. As it can be seen, the results from the BLEU score largely depend on the values of vector w. It is also clear that the score greatly degrades when w contains entries for the tri-gram and quad-gram which correspond to the third and fourth entries of w respectively. The value is also, misleading for very small entries of the uni-gram and bi-gram as seen when w is set to .

Generally, the recorded scores in the case of ROUGE metrics are relative more reliable for the

rouge-1 and

rouge-L. The

rouge-2 has recorded poor performance due to the fact that the word sequence in the reference text does not always overlap with the word sequence in the model’s output. For the example output in

Figure 9, the recorded ROUGE scores are poor in terms of

precision,

recall, and

F-measure for all the three n-grams used in this study despite the semantic meaning being very similar. On the other hand, because the LSA returns the semantic similarity between two text sequences, its output is considerably high (

) for this particular example indicating that despite the discrepancies in the used set of words, the semantic meaning is greatly similar.

Finally, the LSA Similarity score’s input length-model performance analysis indicated that training the model with long inputs can result in stable model performance as the score converged to the mean score with increasing input length (See

Figure 8). It is worth noting that training a highly efficient transformer model requires huge amounts of training data which was a great limitation for this study.

6. Conclusion

Identifying potential causes in aviation incidents quickly is crucial for preventing future tragedies. While flight data recorders are commonly used, delays or damage can obstruct their effectiveness. The Boeing 737 MAX accidents with Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines highlight the impact of such delays. To improve investigation efficiency, this study developed a transformer-based model for predicting the probable cause of an aviation incident given an analysis narrative of the pre/post incident series of events that can be collected from sources including eyewitnesses, radar systems, Air traffic controllers that were in charge of the flight under investigation, maintenance history/logs, etc. The model was trained on extensive NTSB aviation incident reports and allows short- and long-input narratives. This approach shows promise in expediting investigations and enhancing aviation safety through key metrics like BLEU, ROUGE, and LSA.

The assumption is that the model’s output can improve with a larger training dataset. Therefore, as a direction for future work, analysis narratives from other aviation investigation bureaus, such as the ATSB, can be combined with the NTSB narratives, and the model can be retrained on a larger dataset for improved predictions.

References

- Vidović, A.; Franjić, A.; Štimac, I.; Ban, M.O. The importance of flight recorders in the aircraft accident investigation. Transportation research procedia 2022, 64, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, G. Airbus A32x Versus Boeing 737 Safety Occurrences. IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine 2023, 38, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C. A handbook of incident and accident reporting. Cité dans la 2003, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, T.; Yang, Q.; Ebadi, N.; Luo, X.R.; Rad, P. Identifying incident causal factors to improve aviation transportation safety: Proposing a deep learning approach. Journal of advanced transportation 2021, 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.; Suhartono, H. Pilot Who Hitched a Ride Saved Lion Air 737 Day Before Deadly Crash. Bloomberg, March 2019, 19, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dahal, S. Letting go and saying goodbye: a Nepalese family’s decision, in the Ethiopian Airline crash ET-302. Forensic Sciences Research 2022, 7, 383–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanyonga, A.; Wasswa, H.; Turhan, U.; Joiner, K.; Wild, G. Comparative Analysis of Topic Modeling Techniques on ATSB Text Narratives Using Natural Language Processing. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference for Innovation in Technology (INOCON). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, F.; de la Chica, S.; Butcher, K.; Sumner, T.; Martin, J.H. Towards automatic conceptual personalization tools. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 7th ACM/IEEE-CS joint conference on Digital libraries, 2007, pp.

- Jelodar, H.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Feng, X.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L. Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) and topic modeling: models, applications, a survey. Multimedia tools and applications 2019, 78, 15169–15211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, K.D. Using structural topic modeling to identify latent topics and trends in aviation incident reports. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2018, 87, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Huang, F.; Li, Z.; Zhou, J. Exploit latent Dirichlet allocation for collaborative filtering. Frontiers of Computer Science 2018, 12, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805, arXiv:1810.04805 2018.

- Nanyonga, A.; Wasswa, H.; Molloy, O.; Turhan, U.; Wild, G. Natural Language Processing and Deep Learning Models to Classify Phase of Flight in Aviation Safety Occurrences. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Region 10 Symposium (TENSYMP). IEEE; 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I.; et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, X.; Yin, Y.; Shang, L.; Jiang, X.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Wang, F.; Liu, Q. Tinybert: Distilling bert for natural language understanding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.10351 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nanyonga, A.; Wasswa, H.; Wild, G. Aviation Safety Enhancement via NLP & Deep Learning: Classifying Flight Phases in ATSB Safety Reports. In Proceedings of the 2023 Global Conference on Information Technologies and Communications (GCITC). IEEE, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Duh, K.; Gao, J. Stochastic answer networks for natural language inference. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.07888 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nanyonga, A.; Wild, G. Impact of Dataset Size & Data Source on Aviation Safety Incident Prediction Models with Natural Language Processing. In Proceedings of the 2023 Global Conference on Information Technologies and Communications (GCITC). IEEE; 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie, J.; Ontanon, S.; Alberti, C.; Cvicek, V.; Fisher, Z.; Pham, P.; Ravula, A.; Sanghai, S.; Wang, Q.; Yang, L. ETC: Encoding long and structured inputs in transformers. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.08483 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zaheer, M.; Guruganesh, G.; Dubey, K.A.; Ainslie, J.; Alberti, C.; Ontanon, S.; Pham, P.; Ravula, A.; Wang, Q.; Yang, L.; et al. Big bird: Transformers for longer sequences. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 17283–17297. [Google Scholar]

- Katharopoulos, A.; Vyas, A.; Pappas, N.; Fleuret, F. Transformers are rnns: Fast autoregressive transformers with linear attention. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2020; pp. 5156–5165. [Google Scholar]

- Beltagy, I.; Peters, M.E.; Cohan, A. Longformer: The long-document transformer. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.05150 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, R.A.; Si, D. Prediction of injuries and fatalities in aviation accidents through machine learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Compute and Data Analysis, 2017, pp. 60–68.

- Nanyonga, A.; Wasswa, H.; Turhan, U.; Molloy, O.; Wild, G. Sequential Classification of Aviation Safety Occurrences with Natural Language Processing. In Proceedings of the AIAA AVIATION 2023 Forum; 2023; p. 4325. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Mahadevan, S. Ensemble machine learning models for aviation incident risk prediction. Decision Support Systems 2019, 116, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Mahadevan, S. Bayesian network modeling of accident investigation reports for aviation safety assessment. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2021, 209, 107371. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, R.M.A.; Comendador, V.F.G.; Sanz, L.P.; Sanz, A.R. Prediction of aircraft safety incidents using Bayesian inference and hierarchical structures. Safety science 2018, 104, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanyonga, A.; Wasswa, H.; Wild, G. Topic Modeling Analysis of Aviation Accident Reports: A Comparative Study between LDA and NMF Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Smart Generation Computing, Communication and Networking (SMART GENCON). IEEE; 2023; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, V. Classification of aviation safety reports using machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Data Analytics for Air Transportation (AIDA-AT). IEEE; 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Buselli, I.; Oneto, L.; Dambra, C.; Gallego, C.V.; Martínez, M.; Smoker, A.; Martino, P. Natural Language Processing and Data-Driven Methods for Aviation Safety and Resilience: From Extant Knowledge to Potential Precursors. Open Research Europe 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tanguy, L.; Tulechki, N.; Urieli, A.; Hermann, E.; Raynal, C. Natural language processing for aviation safety reports: From classification to interactive analysis. Computers in Industry 2016, 78, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perboli, G.; Gajetti, M.; Fedorov, S.; Giudice, S.L. Natural Language Processing for the identification of Human factors in aviation accidents causes: An application to the SHEL methodology. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 186, 115694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, B.; Xiao, T.; Zhu, J.; Li, C.; Wong, D.F.; Chao, L.S. Learning deep transformer models for machine translation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.01787 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Wan, X. Multimodal transformer for multimodal machine translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 58th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics, 2020, pp.

- Raganato, A.; Tiedemann, J. An analysis of encoder representations in transformer-based machine translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 EMNLP workshop BlackboxNLP: analyzing and interpreting neural networks for NLP, 2018, pp. 287–297.

- Khandelwal, U.; Clark, K.; Jurafsky, D.; Kaiser, L. Sample efficient text summarization using a single pre-trained transformer. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.08836 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Lapata, M. Text summarization with pretrained encoders. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.08345 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sheang, K.C.; Saggion, H. Controllable sentence simplification with a unified text-to-text transfer transformer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Natural Language Generation (INLG); 2021 Sep 20-24; Aberdeen, Scotland, UK. Aberdeen: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021. ACL (Association for Computational Linguistics), 2021.

- Alissa, S.; Wald, M. Text simplification using transformer and BERT. Computers, Materials & Continua 2023, 75, 3479–3495. [Google Scholar]

- Alikaniotis, D.; Raheja, V. The unreasonable effectiveness of transformer language models in grammatical error correction. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.01733 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, N.; Bijoy, M.H.; Islam, S.; Shatabda, S. Panini: a transformer-based grammatical error correction method for Bangla. Neural Computing and Applications 2024, 36, 3463–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Guo, Y.; Chen, H.; Hao, Z. Transformer-based neural network for answer selection in question answering. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 26146–26156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser. ; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Muraina, I. Ideal dataset splitting ratios in machine learning algorithms: general concerns for data scientists and data analysts. In Proceedings of the 7th international Mardin Artuklu scientific research conference; 2022; pp. 496–504. [Google Scholar]

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.J. Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 40th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2002, pp. 311–318.

- Park, C.; Yang, Y.; Lee, C.; Lim, H. Comparison of the evaluation metrics for neural grammatical error correction with overcorrection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 106264–106272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.H.; Jung, S.J.; Jung, S.H.; Yang, S.; Cho, J.S.; Kim, S.H. Grammatical error correction models for Korean language via pre-trained denoising. Quantitative Bio-Science 2020, 39, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A.K.; Singh, A.; Dhiman, M.; Vineet. ; Kaundal, R.; Verma, A.; Yadav, D. Extractive text summarization using deep learning approach. International Journal of Information Technology 2022, 14, 2407–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manojkumar, V.; Mathi, S.; Gao, X.Z. An experimental investigation on unsupervised text summarization for customer reviews. Procedia Computer Science 2023, 218, 1692–1701. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bercken, L.; Sips, R.J.; Lofi, C. Evaluating neural text simplification in the medical domain. In Proceedings of the The World Wide Web Conference; 2019; pp. 3286–3292. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.Y. Rouge: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Proceedings of the Text summarization branches out; 2004; pp. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kryściński, W.; Paulus, R.; Xiong, C.; Socher, R. Improving abstraction in text summarization. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.07913 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, M.; Saha, S.; Bhattacharyya, P.; Chinnadurai, G.; Vatsa, M.K. Natural Answer Generation: From Factoid Answer to Full-length Answer using Grammar Correction. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.03849 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, J.P.; Abrecht, V. Better summarization evaluation with word embeddings for ROUGE. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1508.06034 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dorr, B.; Monz, C.; Schwartz, R.; Zajic, D. A methodology for extrinsic evaluation of text summarization: does ROUGE correlate? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACL Workshop on Intrinsic and Extrinsic Evaluation Measures for Machine Translation and/or Summarization; 2005; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Barbella, M.; Tortora, G. Rouge metric evaluation for text summarization techniques. Available at SSRN 4120317 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Jiang, Y. A DAE-based Approach for Improving the Grammaticality of Summaries. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computers and Automation (CompAuto). IEEE; 2021; pp. 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Kumar, N.; Madhavan, C.V. Text Simplification for Enhanced Readability. In Proceedings of the KDIR/KMIS; 2013; pp. 202–207. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, F.; Shardlow, M.; Hassan, S.U.; Aljohani, N.R.; Nawaz, R. HTSS: A novel hybrid text summarisation and simplification architecture. Information Processing & Management 2020, 57, 102351. [Google Scholar]

- Phatak, A.; Savage, D.W.; Ohle, R.; Smith, J.; Mago, V. Medical text simplification using reinforcement learning (teslea): Deep learning–based text simplification approach. JMIR Medical Informatics 2022, 10, e38095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, T.K.; Foltz, P.W.; Laham, D. An introduction to latent semantic analysis. Discourse processes 1998, 25, 259–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, T.K.; Dumais, S.T. A solution to Plato’s problem: The latent semantic analysis theory of acquisition, induction, and representation of knowledge. Psychological review 1997, 104, 211–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberger, J.; Jezek, K.; et al. Using latent semantic analysis in text summarization and summary evaluation. Proc. ISIM 2004, 4, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Ozsoy, M.G.; Alpaslan, F.N.; Cicekli, I. Text summarization using latent semantic analysis. Journal of information science 2011, 37, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Liu, X. Generic text summarization using relevance measure and latent semantic analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 24th annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval, 2001, pp. 19–25.

- Hao, S.; Xu, Y.; Ke, D.; Su, K.; Peng, H. SCESS: a WFSA-based automated simplified chinese essay scoring system with incremental latent semantic analysis. Natural Language Engineering 2016, 22, 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajjala, S.; Meurers, D. Readability assessment for text simplification: From analysing documents to identifying sentential simplifications. ITL-International Journal of Applied Linguistics 2014, 165, 194–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salton, G.; Buckley, C. Term-weighting approaches in automatic text retrieval. Information Processing & Management 1988, 24, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cer, D.; Yang, Y.; Kong, S.y.; Hua, N.; Limtiaco, N.; John, R.S.; Constant, N.; Guajardo-Cespedes, M.; Yuan, S.; Tar, C.; et al. Universal sentence encoder for English. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing: system demonstrations, 2018, pp. 169–174.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).