1. Introduction

The analysis of pottery in Archaeology allows for the extraction of information related to the dating of a site and provides strong evidence of the technologies employed for its production. The recognition of pottery types can pinpoint the archaeological site in time and determine its spatial distribution, highlighting the cultural tradition of that society and the sociocultural aspects involved in its use.

Despite the highly informative potential that pottery sherds bring to the archaeological context, they also pose a significant challenge during the post excavation phase, since they are found in large quantities and consume significant laboratory space. Indeed, the vast number of sherds remains makes vessels reconstruction a meticulous and time-intensive endeavor, often straining the time and resources required for their proper analysis and interpretation.

Besides time-consuming, the identification and classification of pottery sherds require prior knowledge and experience. In the process of restoring archaeological pottery, sherds that are supposed to belong to the same vessel are grouped together based on the classification of pottery traditions. Sherds are compared one by one, aiming to fit them together until the vessel is reconstructed. In the case of archaeological pottery, missing sherds are common, further complicating the fitting process. Another challenging factor arises when there is a large quantity of fragments belonging to the same pottery tradition: the greater the number of sherds, the more time it will take to classify them into a pottery type and then proceed with the fitting of the sherds and reconstruction of the vessel.

In this work we propose a method for assisting the reconstruction of pottery artifacts from their sherds. The method is founded on 3D models and deep 1D-convolutional neural networks. More specifically, a 3D model of a sherd, in the form of a point cloud, is provided as input to the method. The outcome is a transformation matrix that positions the sherd into the vessel’s coordinates system. The proposed approach involves training artificial neural networks for any specific vessel model. In the literature, this class of approach is regarded as “sherds orientation”. Our method exploits two networks for predicting the respective Euclidean transformation matrix. The first infers translation moments, while the other predicts the rotation parameters. For the complete vessel reconstruction, it would be necessary to repeat the prediction for all its sherds.

The proposed network architecture, the so-called PotNet, is both inspired by the 3D POCO Net [

19] and PointNet [

27] models. The data used for training the PotNet consists of a set of virtual sherds’ point clouds. Those virtual sherds were generated by breaking apart the 3D model of a vessel a number of times in a digital environment. The usage of synthetic data assisted by virtual fragmentation of a vessel’s 3D model enables abundant quantities of training data generation. Such a training scheme addresses the issue of limited real-world training data, which is common in many machine learning applications, including those dedicated to Archaeology. Although the proposed method prescribes training with synthetic data, in this work we evaluated it in predicting the original positions of real sherds, produced by physically shattering real vessels.

The search conducted in the scientific literature up to the preparation of this article indicates that it presents a novel application of deep learning in heritage preservation.

The remainder of this document is structured as follows.

Section 2 brings a literature review, describing a number of computational applications in Archaeology dealing with pottery sherds assembly.

Section 3 describe the materials, including the physical vessels and the respective 3D models.

Section 4 presents the proposed method in detail. The experimental procedure is described in

Section 5. The obtained results and discussion are shown in

Section 6. Finally,

Section 7 presents the conclusions and points out directions for future works. The Appendix section contains the images corresponding to the results.

2. Related Works

This section briefly describes works that deal with the assembly of pottery fragments. As a starting point, we refer to a couple of literature surveys, i.e., [

8,

10].

In the literature, it is possible noticing a number of sherds matching approaches, in order to perform 3D mosaicing [

1,

3,

5,

9,

12,

14,

21,

25,

26,

30,

31,

34].

Papaioannou, G. [

26] present a semi-automatic method for assisting in the reconstruction of archaeological findings from 3D scanned fragments. The method does the one-by-one fragment matching by minimizing the matching error for all pairwise of candidate facets. Cooper, D.B. [

5] use a bottom-up maximum likelihood procedure for pottery assembly. Andrews, S. [

1] determine pairwise match proposals, which are probabilistic evaluated by a series of independent feature similarity modules. Alternatively, given a candidate sherd, Kampel, M. [

14] matches it with a reference sherd by providing an Euclidean transformation which connect both sherds coordinates systems. Marie, I. [

21] use the shadow moiré technique to obtain the 3D model, then, the profiles and edges of the sherds are virtually matched based on their 3D models. Given two sherds, S and T, Huang, Q.X. [

12] approach seeks for common features on the fractured surfaces in order to find out an aligning transformation able to bring S close to T. [

25] propose a flexible interactive system for vessel reconstruction which relies on sherds relations constraints delivered by the experience of an expert. The system employs a global energy minimization strategy for searching for a suitable assembly. Zheng, S. [

34] perform contour curves matching by estimating Euclidean transformations, being the most likely rigid transformations selected. Finally, a global refinement alignment improves the assembly accuracy. Stamatopoulos, M.I. [

31] propose an approach which takes into consideration profile information inside the core of a sherd instead of its surface. The authors argue that such approach works even when sherds are missing, and are neither affected by the presence of external wear and damages, nor by the geometrical shapes and colors degradation. Cohen, F. [

3] exploits vessel surface markings and vessels generic models constructed by archaeologists. Sherds alignment considers a set of weighted discrete moments computed from convex hulls of the markings on the sherds surface and reference points on their borders. Sakpere, W. [

30] extracts keypoints from the sherds point clouds using Principal Component Analysis. Then, pairwise correspondences are established employing adapted ColorSHOT descriptors, and the Iterative Closest Point algorithm is used for refining sherds alignment. Eslami, D. [

9] model sherds borders curves features. After Canny edge detection, fragments are fit together using wavelet transform approximation coefficients.

A few machine-learning-based approaches have been proposed thus far for assisting the restoration of archaeological artifacts from fragments. Some notable examples are [

15,

17].

Kashihara, K. [

15] proposes a system based on computational intelligence to assist in the restoration process. The Real-Coded Genetic Algorithm (RCGA) finds the fitness function from image similarity between the target and correct patterns in plane images taken at multiple camera angles.

To the best of our knowledge, Kim, K. [

17] present the initiative that comes closest to our work. The work employs a Dynamic Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (DGCNN) with skip-dense connections for both classifying the origin of sherds among groups of pottery types, and for predicting its location along a vessel’s revolution axis. The sherd’s position information delivered by that work is, however, limited in relation to the outcome of the method proposed in the current work. While Kim, K. [

17] only infers a sherd’s translation along the vertical axis, the proposed method predicts multiple parameters from which a complete Euclidean transformation matrix is derived, except for the angle of the revolution axis. Such a value was not considered in our work since, for any sherd located in the body of revolution solid shaped vessels, that angle is undetermined. Additionally, while only synthetic data was used to test the method proposed in Kim, K. [

17], in this work we evaluate the proposed method with real sherds, produced by the fragmentation of real vessels.

3. Materials

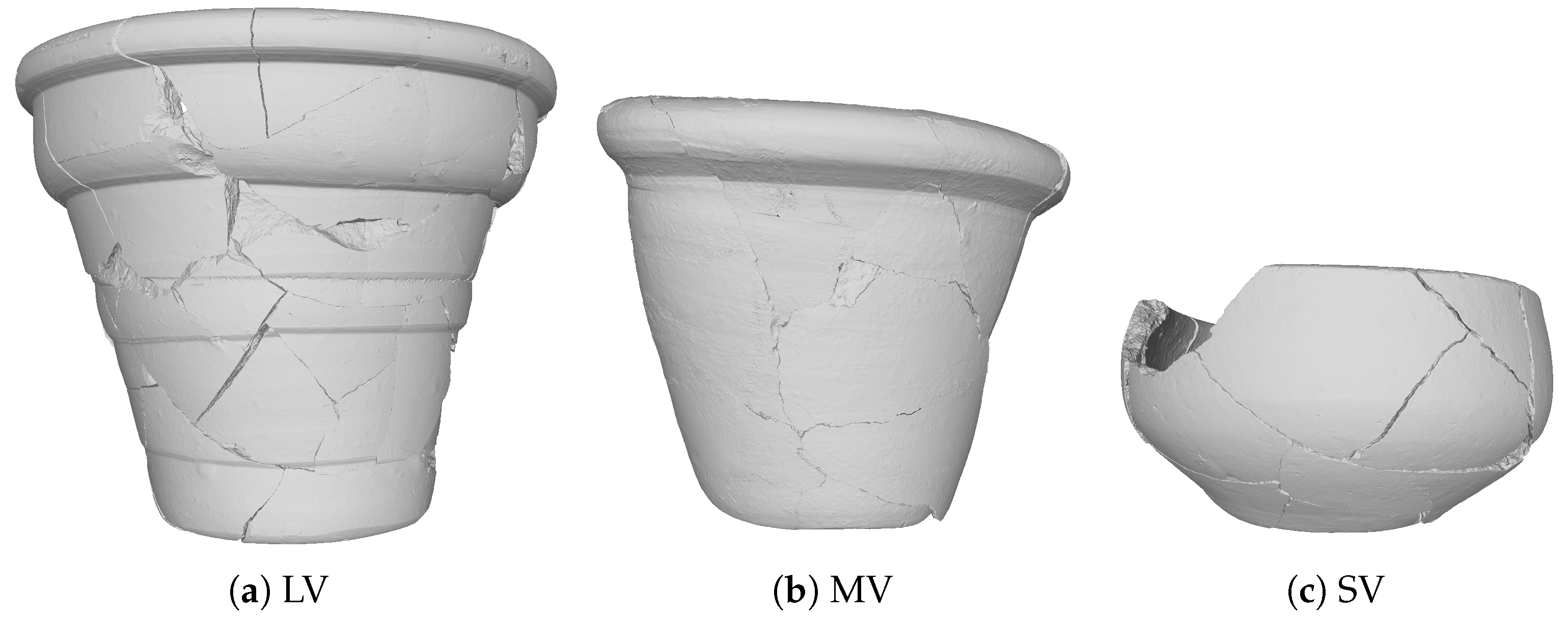

The objects employed in this research are shown in

Figure 1. The figure shows three real-world pottery vessels named LV, MV and SV, acronyms for Large, Medium and Small Vessel. Regarding shattering, the vessels were simply dropped from an approximate height of 1.5 m. Such a process does not allow controlling the resultant fragments sizes, and may cause loss of vessel mass due to tiny fragments which have great potential to increase reconstruction uncertainty. The resulting sherd sizes range from small chips to a maximum length of 10 cm. To avoid excessive uncertainty, only sherds larger than 3 cm were considered in this research, wich ammounts to 57, 20, and 21 physical sherds for LV, MV, and SV, respectively.

After shattering, the resulting sherds were digitized using a structured-light stereoscopic 3D scanner, the Virtuo Vivo

™ intraoral scanner [

16,

32]. Despite have being designed to dental use, after a short-time operational training, it proved to be precise enough for generating 3D models of sherds. To simplify sherd identification hereinafter, they were named by concatenating the vessel acronym to its scanning order, e.g. SV21.

Once digitized, the corresponding sherds were manually matched together using the Blender 3D mesh modeling software [

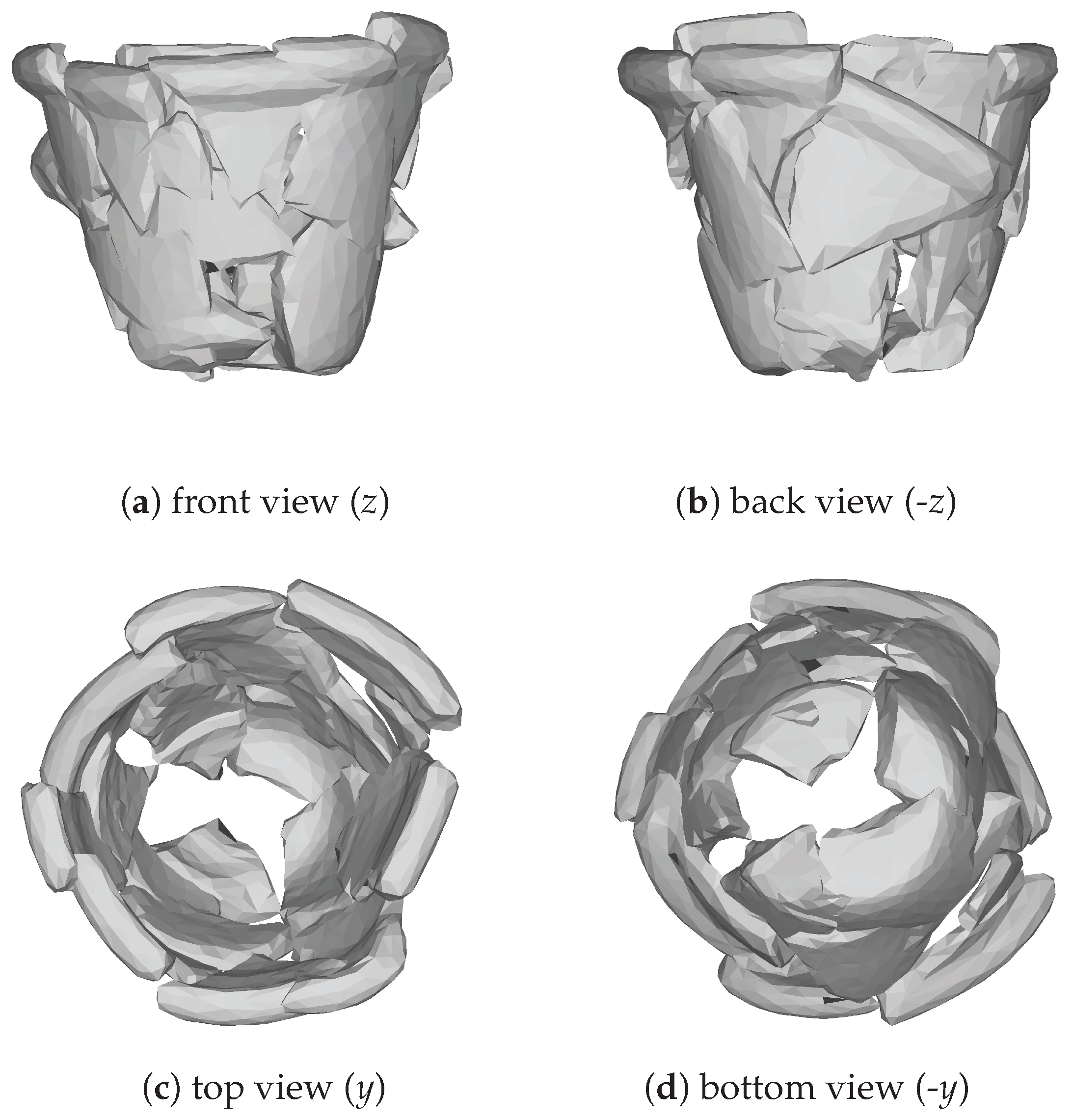

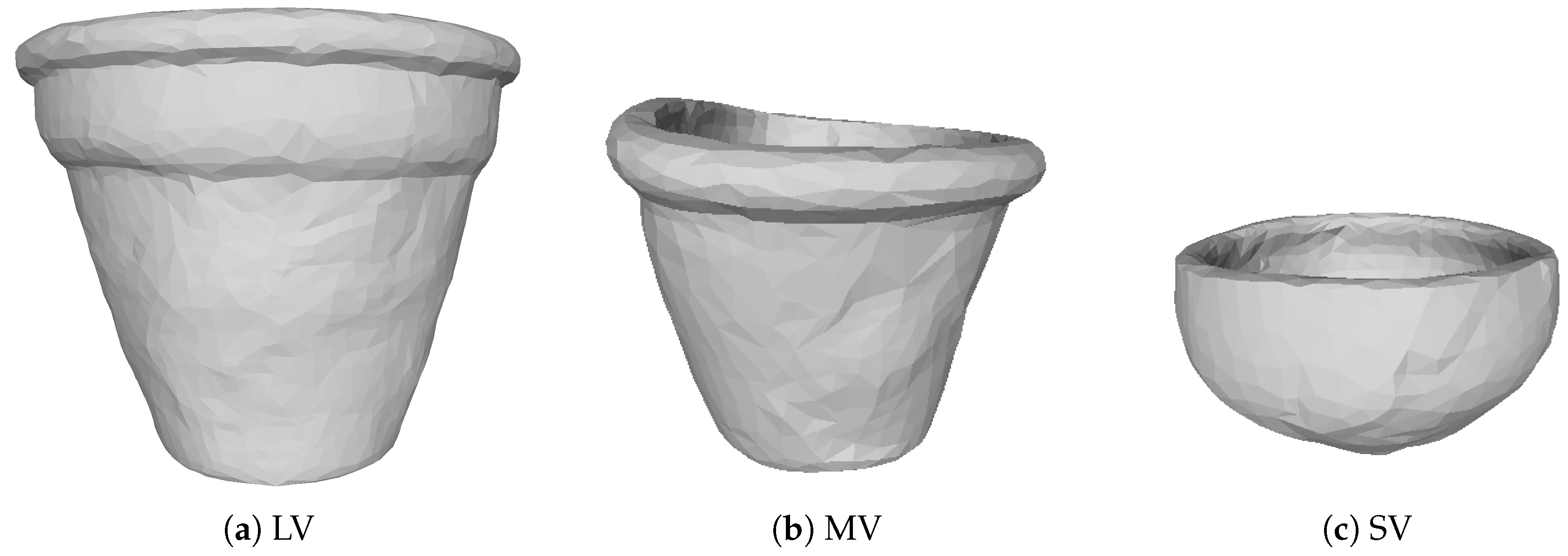

4]. The reassembled vessels are shown in

Figure 2, in which the readers can easily notice the sherds’ boundaries.

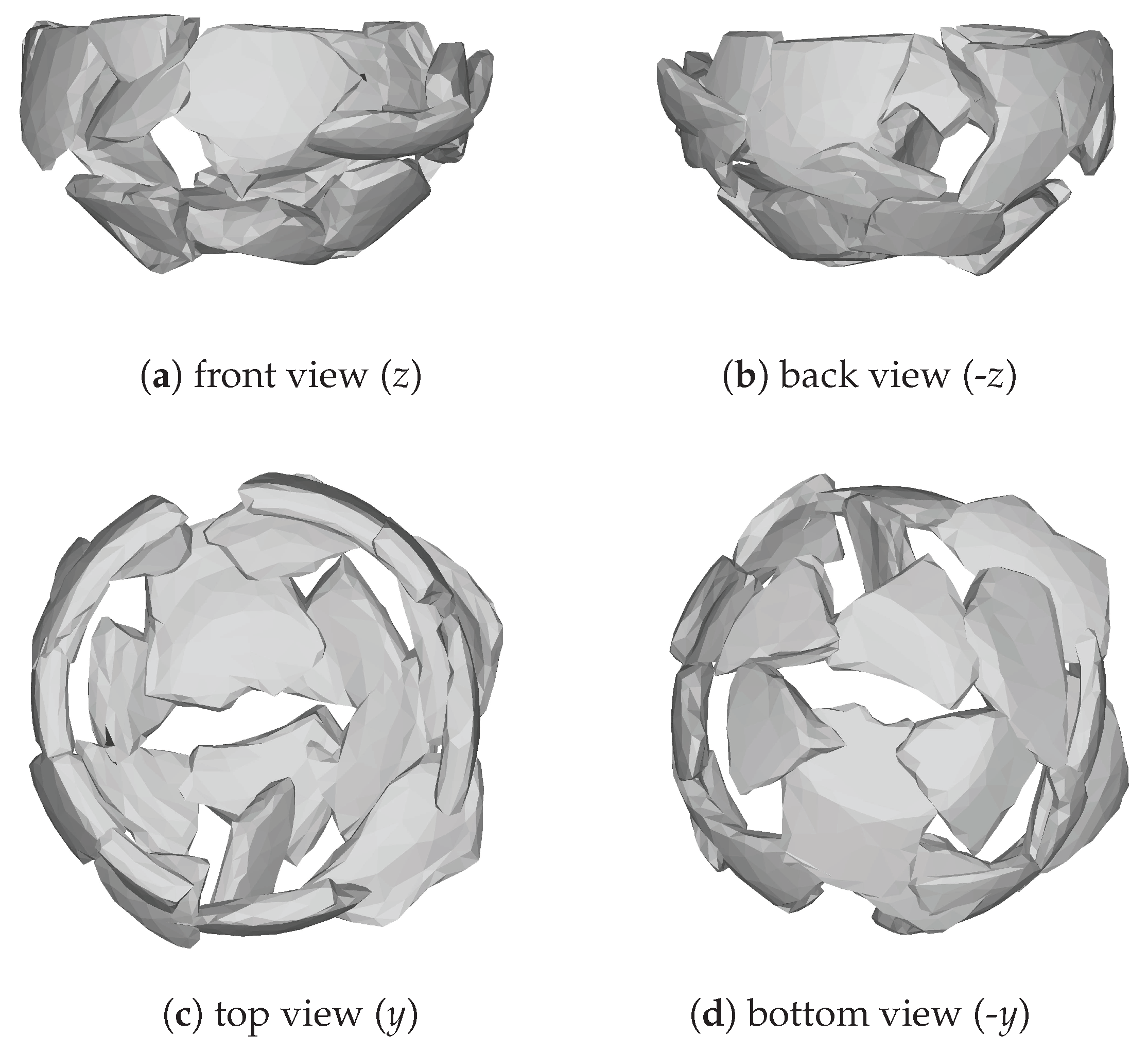

To virtually restore those vessels, it was necessary to stitch the sherds together in an single 3D model. Considering the high precision of the scanned sherds’ meshes, making that procedure feasible required applying a decimation process on every mesh. In this work, the Quadric Edge Collapse Decimation filter [

11] available in the Meshlab API [

23] was employed. The restored vessels can be seen in

Figure 3. Those 3D models are the input for generating the synthetic data used during training as a surrogate to overcome the lack of training data.

4. Proposed Method

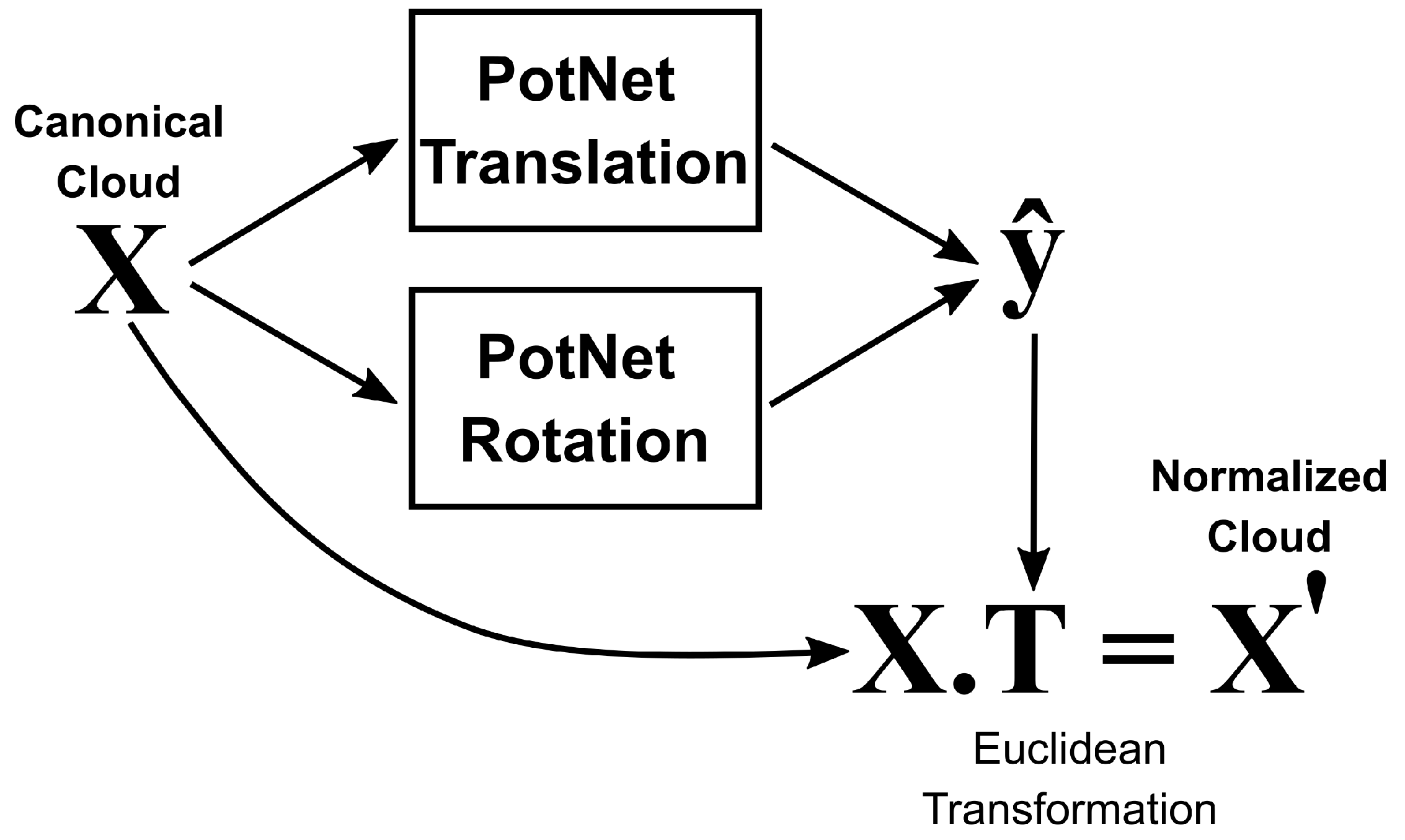

Figure 4 depicts an overview of the herein proposed sherds orientation method. By and large, given a point cloud

relative to a specific sherd expressed in its canonical coordinate system, referred in

Figure 4 as Canonical Cloud, the method produces

, a version of such a sherd cloud expressed in terms of the vessel (normalized) coordinate system. Mathematically, that process consists of a applying a determined Euclidean 3D transformation in Affine space, in the form of a linear operator

, where

, while

and

are

matrices, where

p stands for the number of points on every cloud. Thus, every column in those matrices denotes a 3D point of the cloud expressed in homogeneous coordinates (consisting of concatenating a one after the respective 3D coordinates). The coefficients of the transformation matrix are obtained through a two-branches neural network. Together, both branches predict the values of the parameter vector

. Based exclusively on

, a deterministic mathematical procedure brings about the transformation matrix

.

As it can be noticed on

Figure 4, the core of the proposed method consists of a dual branch neural network architecture, both predicting an outcome based on exactly the same input

. The branches of the neural network use the same special-purpose backbone, the herein proposed PotNet backbone, which are trained through independent training procedures.

There is a subtle difference between the heads of each PotNet branch. While the translation branch produces a two dimensional vector output relative to the y and z axes translation offsets, the rotation branch produces a vector of six dimensions. Given that 6D vector, the Gram-Schimdt process brings about the rotation matrix coefficients [

35].

In the following sections, the most significant components of the proposed method are presented in detail.

4.1. Problem Modeling

First we assume pottery vessels have axial symmetry in relation to the y-axis, letting virtually infinite valid orientations for a given sherd being produced by simply rotating it by an arbitrary angle around that axis. Thus, by definition, orientation prediction is an ill-conditioned problem. We observe, however, that such an does not prevent considering components such as handles or shoulders of a vessel. An additional source of ill-conditioning is the individual sherd coordinate system. So, in absence of a natural standard for the sherd systems, it is imperative establishing one.

For overcoming such ill-conditioning problem, we propose simplifying it on both sides. On one hand, we reduce the vessel system on one degree of liberty by eliminating the angle relative to the rotation axis. That brings about the so-called normalized system

1, which consists on bringing the sherd’s centroid to the

-plane. On the other hand, we defined an absolute, unique, inner system for each sherd. Such system, which only depends on the sherd’s shape, was named the “canonical system”.

4.1.1. Normalized Cloud

Normalized clouds are obtained by eliminating the rotation angle around the vessel revolution axis, so moving sherds centroid to the plane. That creates a standard position for every sherd relative to the vessel’s system. In this work, we approximate the centroid through the arithmetic mean of the points on the original sherd’s point cloud.

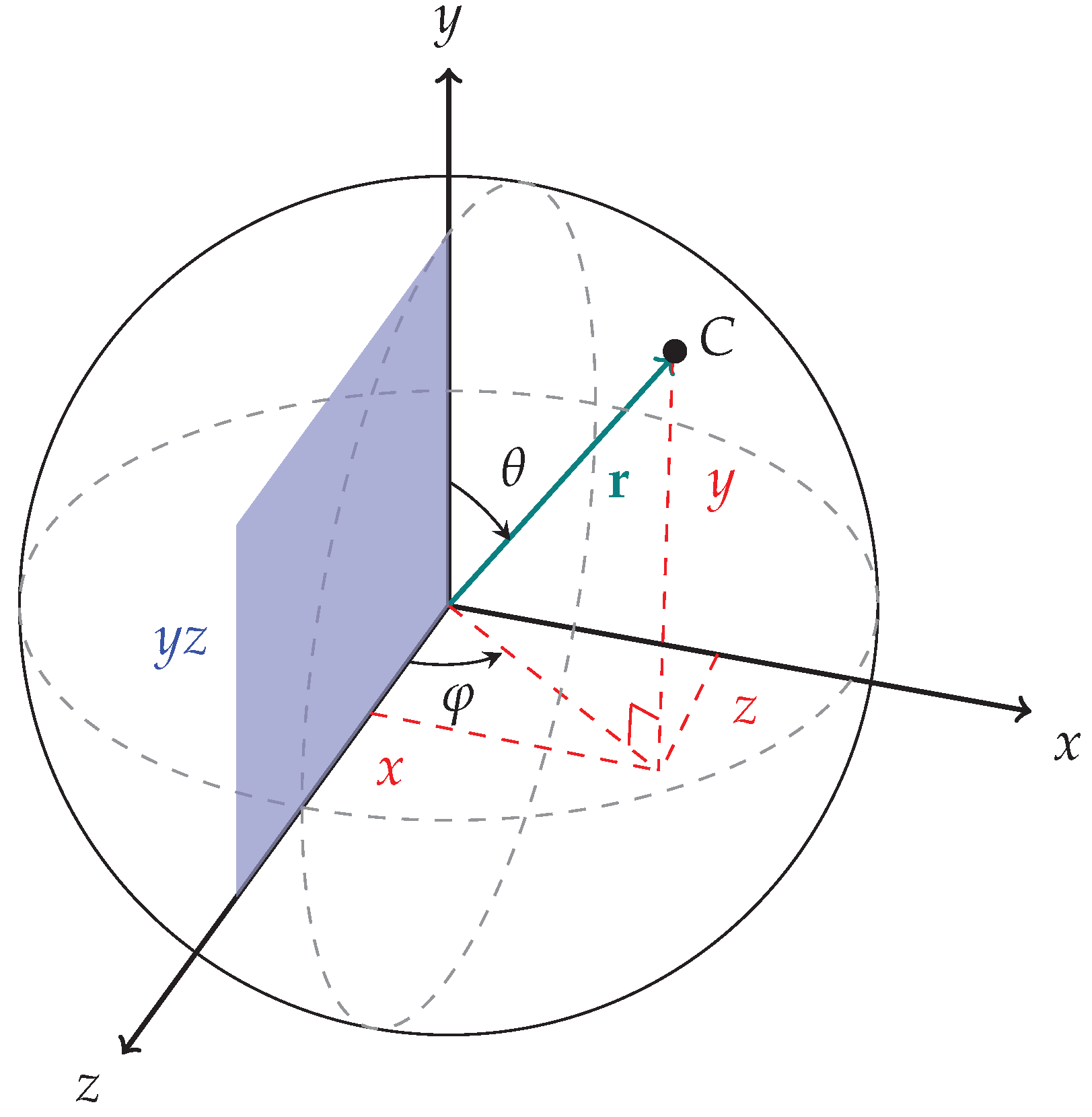

Bringing the centroid to the desired position is made easier by defining a spherical coordinate system (see

Figure 5). Given

, the Cartesian coordinates of the centroid

C, Eq.

1 presents the rotation matrix that brings such point cloud to its normalized position.

where

. Thus, given

, a vector which expresses a given sherd’s cloud point in terms of the physical vessel system,

, the vector of normalized coordinates for that point, is obtained multiplying

by

.

4.1.2. Canonical Cloud

Canonical cloud stands for the form in which sherds are presented at the input of our approach. Its respective coordinates system helps control the degrees of freedom of the sherd orientation process, creating a deterministic and exclusive canonical model for any given sherd. The origin of the canonical system coincides with the centroid of the sherd, while the vector space aligns with the directions of the minimum volume bounding rectangular cuboid.

Bringing a point cloud from its arbitrary sherd coordinate system to its canonical form involves three steps. Firstly, the sherd’s minimal bounding rectangular cuboid must be obtained. Then, the cloud points are translated, bringing the sherd’s centroid to the origin of the coordinate system. Finally, the Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) [

33] provides the matrix that projects the cloud into the canonical coordinate system.

Computing the minimal volume enclosing the bounding cuboid is performed with a faster alternative to the O’Rourke, J. [

24] approach: the Jylänki, J. [

13] algorithm implemented in the Trimesh API [

7].

Regarding SVD, it basically consists of the factorization of a rectangular matrix

into the product of three other matrices: an

orthogonal matrix

whose columns are the left singular values of

; a rectangular

diagonal matrix

containing the singular values of

in descending order; and the transpose of an

orthogonal matrix

, whose columns are the right singular values of

, in the form:

In this work, is a 8-by-3 matrix containing the coordinates of the vertices of the minimum volume bounding rectangular cuboid with centroid at the origin. has the same dimensions as , while and have orders 8 and 3, respectively. multiplication projects the cuboid vertices into the canonical space.

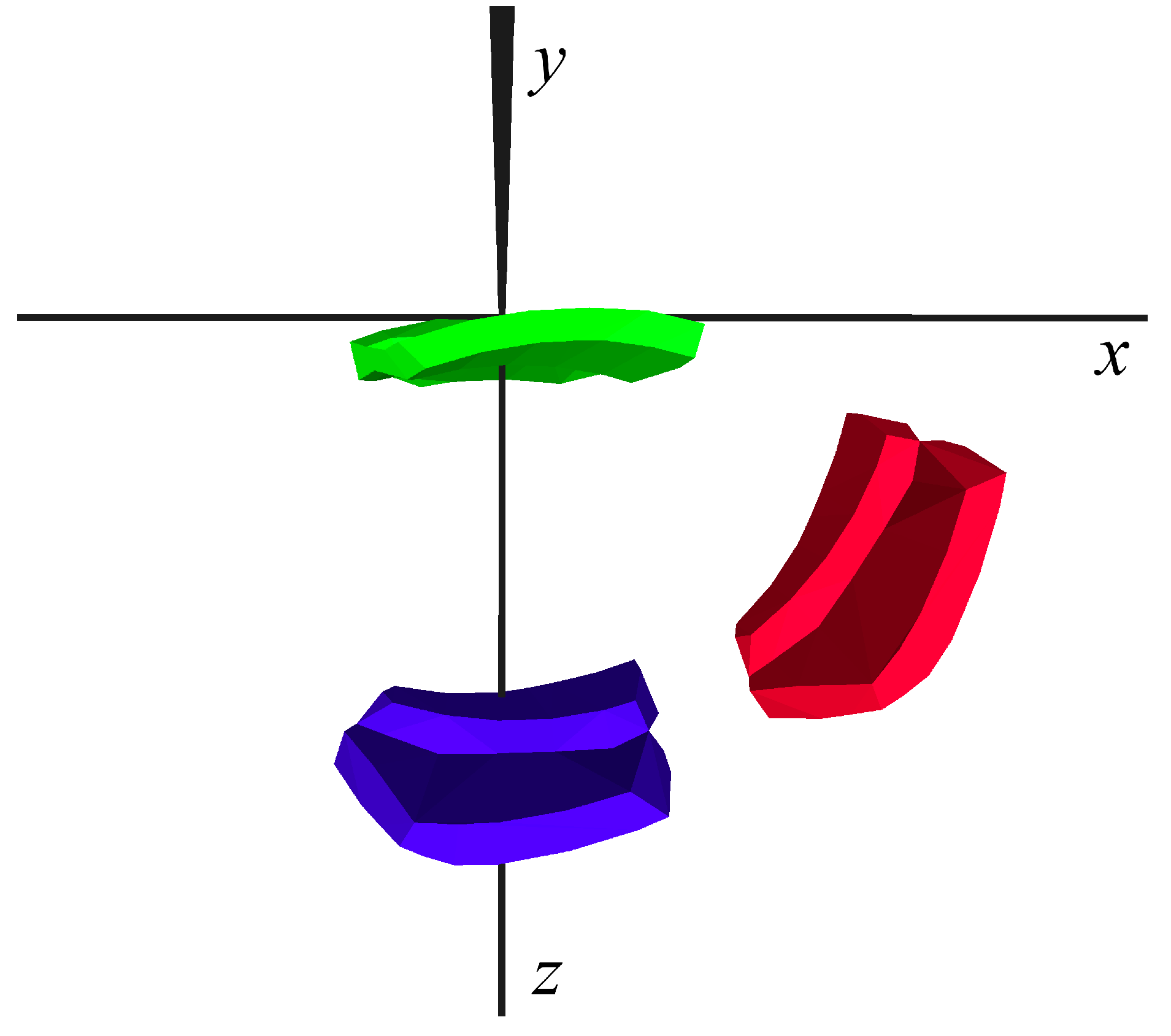

As visual example, in

Figure 6 the reddish object refers to an arbitrary sherd in its original position relative to the vessel, the bluish object represents the sherd in the normalized position, while the greenish object correspond to the sherd in the canonical position. At this point it’s important to observe that no knowledge about a sherd’s original position in the vessel is needed to place it in its unique canonical position.

4.1.3. Target Euclidean Transformation

Once having the normalized and canonical point clouds of a sherd, one needs to obtain the transformation that relate both clouds. The canonical to normalized position transformation is the one used for creating the training target , which will be later compared with the PotNet prediction .

In this work, the Kabsch algorithm [

2,

20] is used for computing the rotation components of the training targets

. The Kabsch algorithm is a method for calculating the optimal rotation matrix that minimizes the root mean squared deviation between two paired sets of points. The translation coefficients are computed as the distance between the centroids of the normalized and canonical point clouds.

In this work, we propose the use of a six-dimensional vector for modeling the rotation matrix. The full 3-by-3 rotation matrix may be recovered using the cross product restricted to the orthogonality constraint.

4.2. PotNet Model

In this work, we introduce PotNet, a neural network model dedicated to non-linear regression whose design was inspired by the first network of the 3D POCO Net [

19]. Differences between their architectures reside in the initial layers, activation functions and in the output layer size. When receiving as input a point cloud in the form of a matrix whose rows represent the points and columns the coordinates, PotNet predicts the transformation parameters associated with that point cloud.

By and large, PotNet’s architecture is composed by a number of single dimensional convolution layers, followed by a global uni-dimensional max pooling layer aiming at bringing about a number of features for the input point cloud. Such features pass through a multi layer perceptron network built on top of the convolutional layers. Most of the PotNet Layers are followed by ReLU activation functions, the only exception being the output layer which is coupled to a linear activation function. In this work, we experimented with five convolutional layers, containing respectively 64, 64, 64, 128, 1024 filters. The multilayer percepton hidden layers, which employ batch normalization, encompasses 512 and 256 neurons, while the output layer contains

N neurons. The number of neurons in the output layer can be 2 or 6, depending if it is a translation or a rotation network branch. The proposed PotNet network architecture is summarized in

Table 1.

4.3. Training Procedure

Deep learning models are known for demanding large volumes of training data. Nevertheless, the accessibility of fully restored archaeological vessel 3D models is limited due to incompleteness of archaeological records, the high costs associated with cataloging, and the time-consuming nature of the process.

An alternative for coping with such data scarcity is to use restored models as the ones presented in

Figure 3 to produce synthetic training data. Our approach relies on a virtual vessel shattering procedure (see

Section 5.1), which can be instantiated with different parameters, for delivering an arbitrary amount of synthetic sherds for a particular vessel. Then, point clouds sampled from the sherds created with the virtual shattering algorithm are processed as described in

Section 4.1.1 and

Section 4.1.2 to control the degrees of freedom. Afterwords, using the normalized and canonical point clouds as input, the respective target Euclidean transformation is computed using the algorithm described in

Section 4.1.3.

As mentioned in

Section 4, the PotNet Backbone is specialized into two models, one for rotation and another for translation. Each model is trained independently through an optimization process which minimizes a particular loss function. Therefore, parameters vector

gathers the rotation components

and translation moments

. As usual, losses relate target

and predicted

vectors. Accordingly, the respective loss functions

and

are used for each specialized network training. The L2 norm between the target and predicted vectors is shown in equation

3.

5. Experimental Setup

Concerning experimental procedure, this section regards method implementation details, and dataset description.

5.1. Virtual Shattering Procedure

To address the well-documented high data volume demanded for training deep learning models, we devised a way to automatically produce synthetic sherds. In that regard, we employed the Cell Fracture tool, a native feature of Blender software conceived to break up digital object models into an arbitrary number of fragments. The tool is based on a 3D Voronoi Diagram implementation designed for polyhedron fragmentation [

22,

28]. Cell Fracture implements a non deterministic approach whose outcome is influenced by some parameters, including the maximum number of fragments provided and a seed for noise generation ranging from 0 to 1. For a regular object like a cube, 0 means more regular shapes, while 1 means more natural shapes for the breaking results. For uneven objects, the Voronoi point distribution is always random. Thus, results have uneven and natural shapes. So, even fixing the noise parameter value, point distribution in the breakage process will still be random. In this work, the noise parameter value was fixed as 0.5. The maximum number of fragments in each break is set up to be the upper bound of the total number of real fragments for each vessel.

With the Cell Fracture tool, the 3D model of the restored LV vessel (refer to

Figure 3a) was broken up 2,000 times, being 60 the maximum number of fragments (synthetic sherds) in each run. Out of those, the product (synthetic sherds) of 1,800 runs composes the training set. The synthetic sherds created in the other 200 runs compose the test set.

The 3D model of the restored MV and SV vessels (refer to

Figure 3b and

Figure 3c) were broken up 3,300 times each, with a maximum of 30 sherds on each run. The product of 3,000 runs composes the training set, while the other 300 runs compose the test set. Performing more breaking runs for these two vessels while compared to the LV looks forward to standardize the number of sherds for these 3 vessels since for MV and SV less sherds are produced in each break.

5.2. Synthetic Sherds Datasets

Synthetic sherds are normalized and then placed in canonical position, afterwords, the respective target transformation matrices are calculated. In sequence, the Poisson-disk sampling filter [

6] of the Meshlab software is applied to every virtual sherd (in canonical position) in order to standardize the number of points in their point clouds. The resulting point clouds are then represented by a 1,024×3 matrix.

Part of the synthetic sherds are discarded, only sherds whose respective canonical rectangular cuboids exceed 10 cm

3 were selected to compose the datasets.

Table A1 shows the numbers of synthetic sherds used for training and testing the PotNet instances.

We recall that 57, 20, and 21

real sherds were selected from the physical shattering of the real LV, MV, and SV vessels, respectively. Those sherds were also used to evaluate the PotNet instances, as reported in

Section 6.

5.3. Training

A rotation-translation PotNet set was trained for each vessel independently, resulting on three different instances of the Rotation and Translation networks. Training procedures employed the same hyperparameters values, as follows. The batch size was 128. The Adam optimizer [

18,

29] was used with standard values (i.e., exponential decay rate for the 1st and 2nd moments as 0.9 and 0.999, respectively). The learning rate was fixed at 0.001. Networks were trained until the maximum number of epochs were reached: 1,500 for rotation network; and 1,000 for translation network. Training was performed on a 12th generation Intel Core i9-12900F hexacore with 5,1GHz, GPU NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090, 128GB RAM, with the operating system Ubuntu 22.04.3 LTS, kernel Linux 6.2.0-37-generic, Python 3.10.12 and Tensorflow 2.10.

6. Results and Discussion

This section presents and analyzes the outcomes for both synthetic and real-sherds test sets. This analysis concerns predictions quality while bringing about the transformation matrices, , that take the sherds canonical point clouds to the normalized space.

After prediction, every point

in the canonical cloud is multiplied by the corresponding

matrix resulting in

, a predicted point that should fit to

, its homologous in the ground truth normalized cloud. The predicted sherds points positions are compared to the respective reference normalized positions in order to compute the relative errors. Since the predicted and normalized point clouds of a sherd have exactly the same points, the exact error between those two clouds can be computed. The errors are calculated considering each point, and each coordinate axis. From the differences of each point positions we computed the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), given by Equation

4.

We also computed the RMSE relative to each coordinate axis, (x, y ,z), considering all points in the test dataset. Referring to Equation

4, instead of considering vector distances, we simply computed the differences of each particular coordinate. In addition, we group errors relative to axis x, y, z to present the standard deviation values (STD).

6.1. Results over the Synthetic Test Set

The number of sherds in the

synthetic test set for each vessel is given in

Table A1, while

Table 2 presents the values of RMSE, RMSE (x, y, z), and STD obtained for the whole synthetic test set. In average, the positioning error between the predicted and normalized clouds of the synthetic sherds is less than 1.9 cm for all vessels (column “RMSE”), which we considered small in relation to the size of the vessels. The standard deviation of the errors for all vessels is not more than 1 mm, showing that the errors in the predictions are quite stable.

Regarding translation, “RMSE (x, y, z)” column shows that the axis with the greater variation is the vertical one (y) which represents the height of the vessel. That coordinate is the harder to predict. The table shows consistent results for this observation, being the error related to y-axis the larger one in all cases.

6.2. Results over the Real-World Test Set

The real test set comprises the 57, 20, and 21 real sherds selected from the physical shattering of the real LV, MV, and SV vessels, respectively. Those sherds were 3D scanned, decimated by a factor of 3,000 and remeshed (a tesselation algorithm is used to connect the new vertices, producing a new mesh).

In these experiments, with the rotation and translation networks trained with the synthetic sherds datasets, we aim at validating the the proposed method with real objects, showing that it can be employed in real-world problems. At this point, it is important to observe that the real sherds were not used for training the deep networks.

After decimation, each sherd was sampled to 1,024 points with the Poisson-disk sampling Meshlab filter, resulting in a denser point cloud representation. Each point cloud was placed in its canonical position, and inputted to the trained rotation and translation models. It’s worth mentioning that, for the real test set, since each real sherd position comes from its natural position in the reassembled vessels (see

Figure 2), obtaining their ground truth normalized positions is trivial, being necessary solely eliminating the

rotation angle (see

Figure 5 and Equation

1).

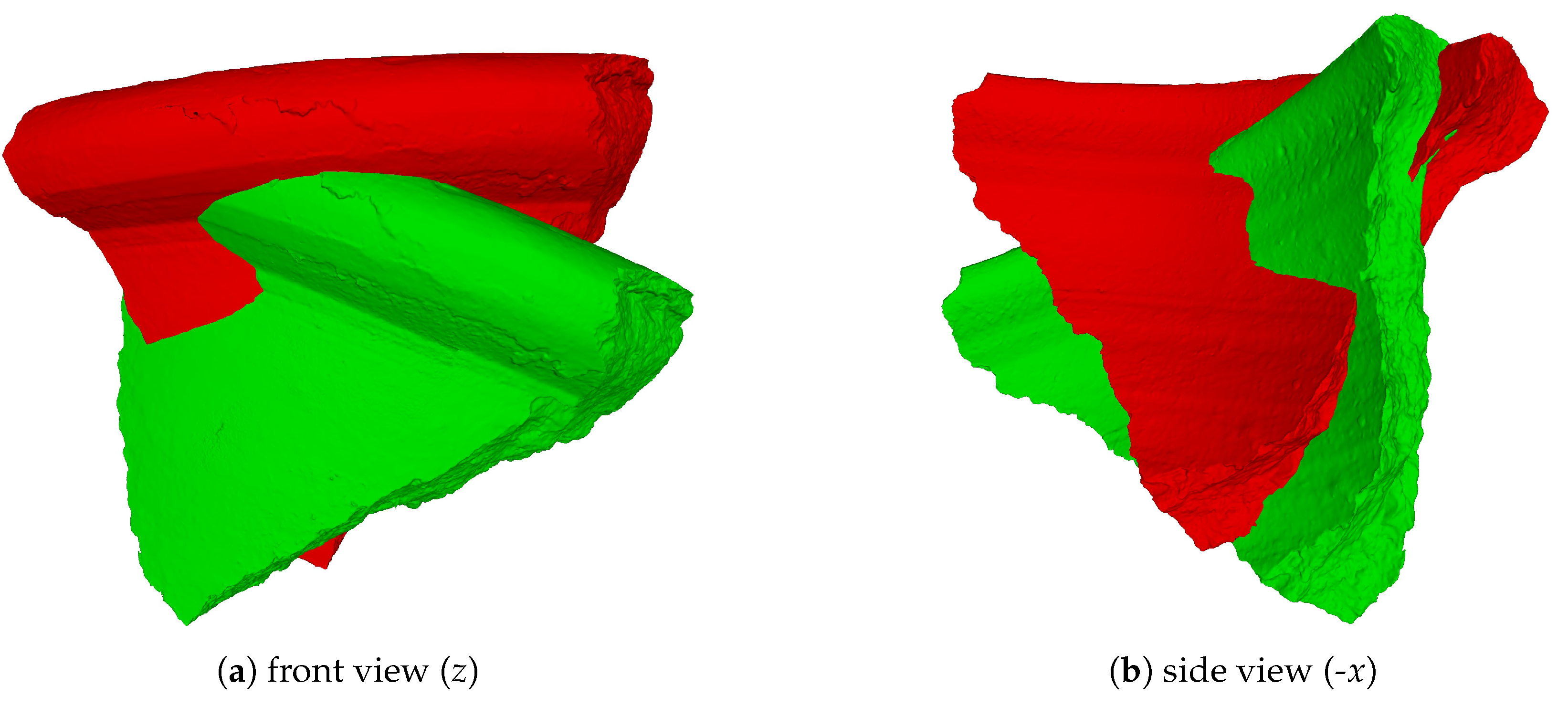

For visualization purposes, regarding the test set, it is sufficient to multiply the sherd’s point cloud in the predicted position in normalized space by the inverse of

matrix, so rotating the cloud around the

y-axis counterclockwise, bringing the sherd from the canonical space to the vessel’s space. This will cause the sherd to return to its true position within vessel’s coordinate system, ensuring that the rotation and translation predictions are maintained. The results are depicted in

Figure A1–

Figure A3.

Despite variations among individual sherds, overall, the qualitative results seen in

Figure A1–

Figure A3 are close to the expected, showing that the rotation and translation models closely approximate the expected outcomes of a pottery vessel reconstruction process from its sherds.

Table 3 shows the error metrics obtained for the real sherds of vessels LV, MV and SV, which are consistent with the results obtained for the synthetic test set (shown in

Table 2). The standard deviation of the errors is less than 1 mm for all vessels, showing again that the prediction errors are stable.

We believe that the slightly poorer results for the real sherds are due to the more irregular surfaces of the real-world sherds, as compared to the computer-generated ones, which have smoother, regular surfaces. That results in a more complex distribution of vertices on the real sherds, making it more challenging for the network to learn.

Table 4 shows the best, average and worst predictions for particular real sherds regarding different vessels. The sherds were selected based on their RMSE values. The best cases correspond to the lowest RMSE value, the average cases correspond to the the median, and the worst cases correspond to the highest RMSE value.

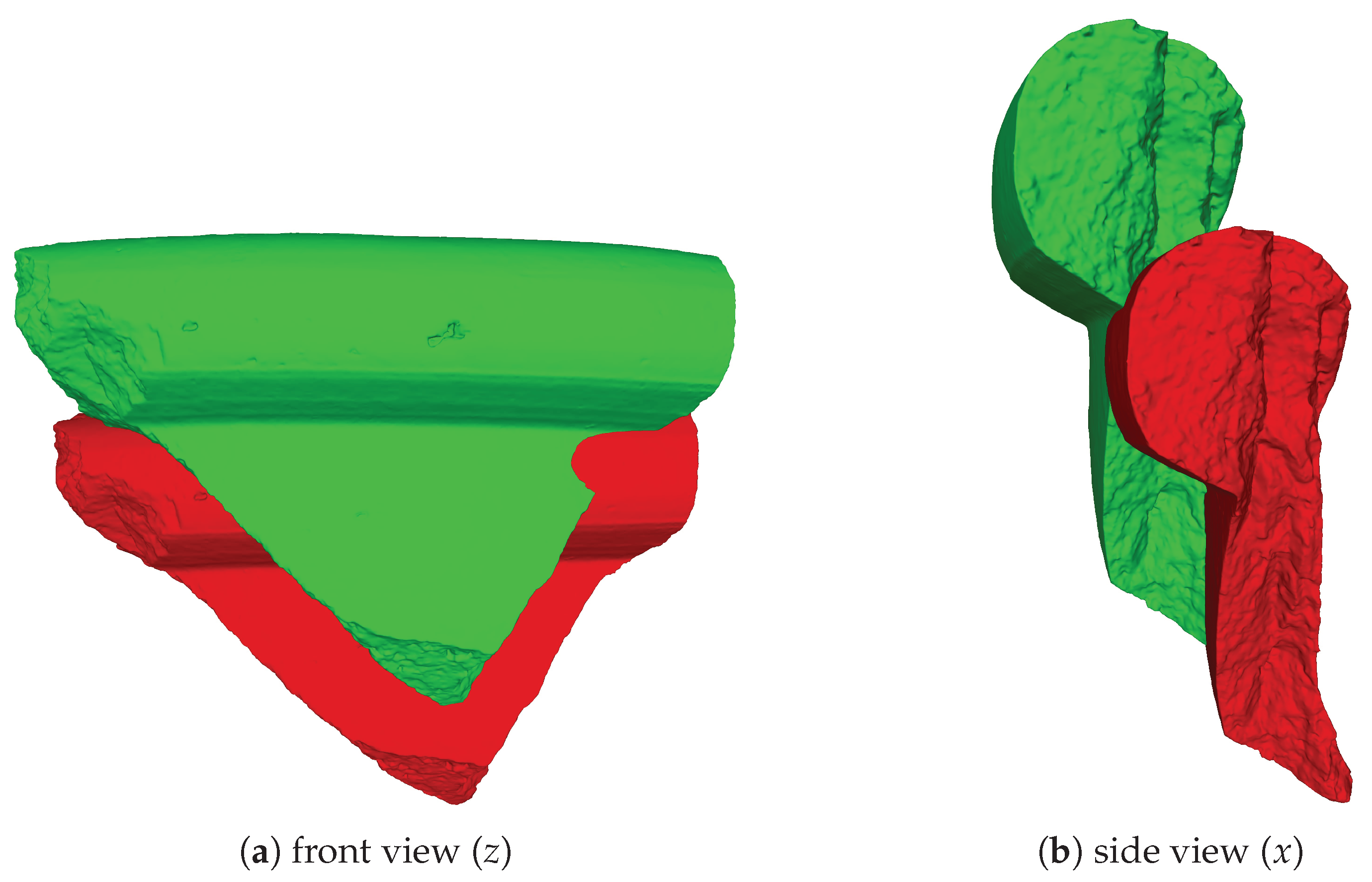

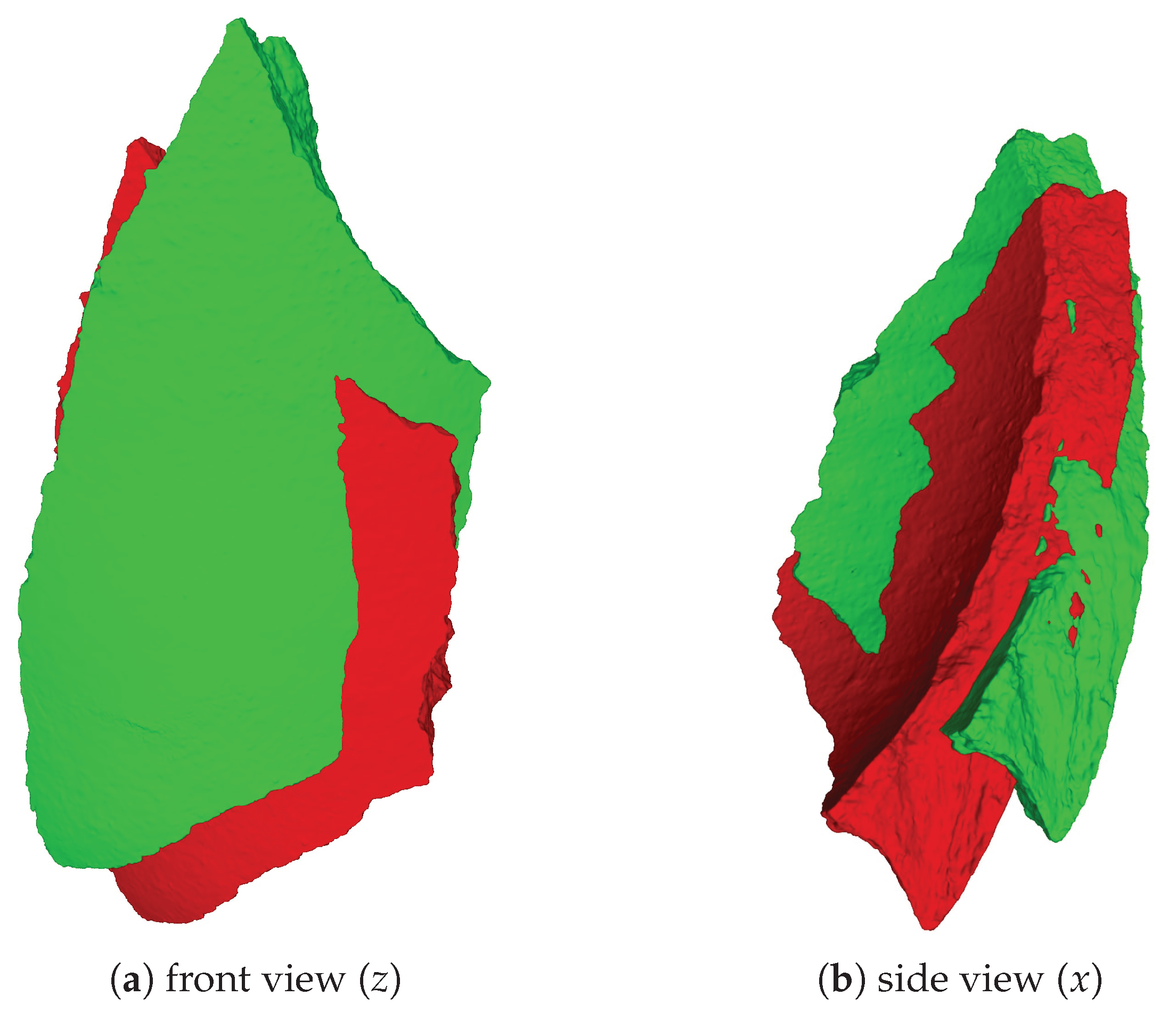

The prediction for sherd SV14 (

Figure A10), the best case among SV real sherds, achieved an RMSE of 0.019 m, corresponding to a distance of 1.9 cm between sherd SV14 in the expected and predicted positions. The worst case of MV, the MV17 shown in

Figure A9, achieved an RMSE of 0.038 m, corresponding to a distance of 3.8 cm between the expected and predicted positions.

The qualitative results obtained for SV are visually inferior to those obtained for MV, as the sherd SV21 (

Figure A11) and sherd SV11 (

Figure A12) were placed upside down compared to their expected positions. In terms of RMSE, the values of 0.015 (SV21) and 0.021 (SV11) are not very different from those obtained for MV because, being an average, they are balanced by the results of the most central part of the sherd. The worst case of SV (SV11) had an error of only 0.025 (2.5 cm).

7. Conclusion

In this work, we proposed and evaluated a deep learning-based approach for pottery reconstruction. The proposed method works by inferring the geometric transformation that moves a 3D model of a sherd in a standard, canonical position, to its original position relative to the respective vessel’s coordinate system.

The method was evaluated using three distinct real vessels. The vessels were first physically broken into real sherds. The sherds from each vessel were digitally scanned, and a 3D point cloud from each sherd was produced. The vessels were then virtually reassembled into 3D models, which were later digitally broken apart a number of times to produce virtual sherds. The virtual sherds were then used to train convolutional neural networks with the proposed PotNet architecture. Two PotNet models were trained for each vessel type; one responsible for predicting translation moments, and the other for predicting the rotation parameters of the geometric transformation associated to a single sherd.

In the experiments, the point clouds of the real sherds were subjected to the networks, which predicted the transformation that would move them to their expected positions. The results were considered very satisfactory, as the average errors considering all vessels were in the centimeter range. The results were also very stable, showing standard deviations in the millimeter range. The qualitative results, obtained by visually comparing the sherds at their real and predicted positions, were also satisfactory, as the automatic outcomes were similar to their expected appearances.

In the continuation of this work, we plan to investigate enhancements of the proposed PotNet architecture, in search of higher positioning accuracies. We also plan to extend the method, by proposing a more general architecture, which not only predicts a sherd’s position, but also delivers a probability of the sherd belonging to a particular vessel shape. Finally, we plan to exploit texture and decorative patterns in order to automatically stitch the sherds of a same vessel together.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Fundação Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Neodent and the Straumann Group for providing the Virtuo Vivo™ intraoral scanner, which enabled the development of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Quantities of synthetic sherds in the training and testing sets.

Table A1.

Quantities of synthetic sherds in the training and testing sets.

| Vessel |

Train |

Test |

Total |

| LV |

78,892 |

8,695 |

87,587 |

| MV |

76,664 |

7,816 |

84,480 |

| SV |

77,377 |

7,694 |

85,071 |

Figure A1.

Four different views of the sherds from the LV real-world test set placed at the predicted positions and rotated counterclockwise by the inverse of matrix.

Figure A1.

Four different views of the sherds from the LV real-world test set placed at the predicted positions and rotated counterclockwise by the inverse of matrix.

Figure A2.

Four different views of the sherds from the MV real-world test set placed at the predicted positions and rotated counterclockwise by the inverse of matrix.

Figure A2.

Four different views of the sherds from the MV real-world test set placed at the predicted positions and rotated counterclockwise by the inverse of matrix.

Figure A3.

Four different views of the sherds from the SV real-world test set placed at the predicted positions and rotated counterclockwise by the inverse of matrix.

Figure A3.

Four different views of the sherds from the SV real-world test set placed at the predicted positions and rotated counterclockwise by the inverse of matrix.

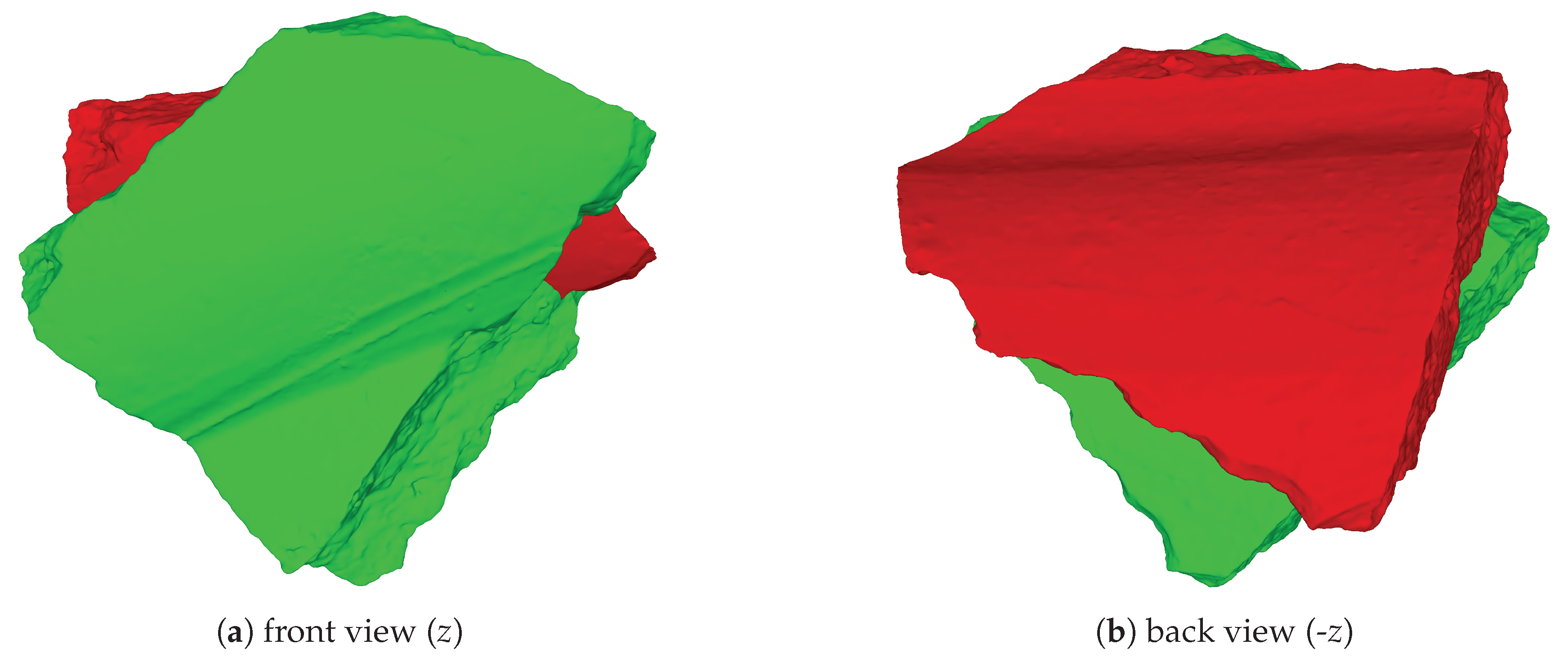

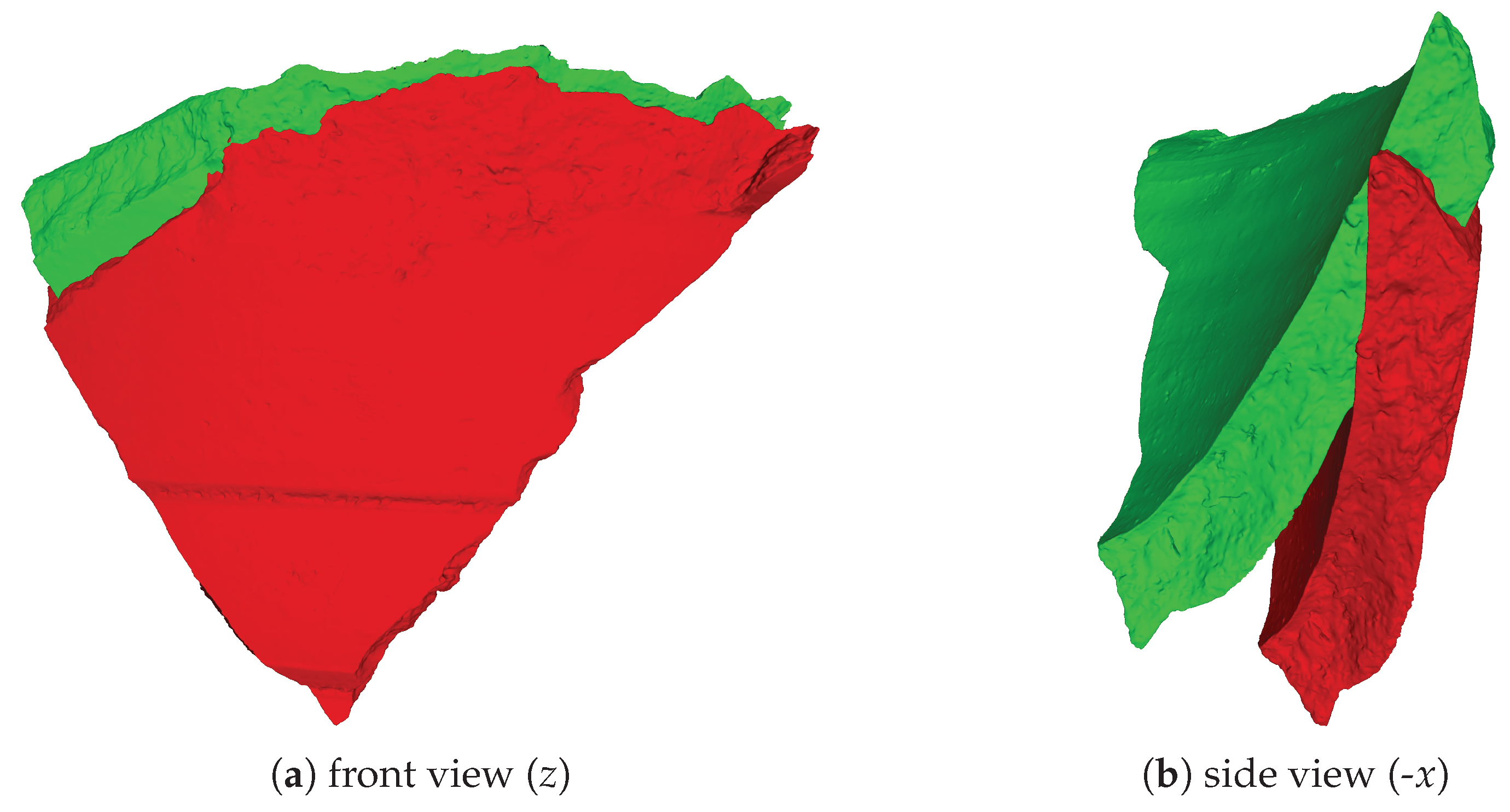

Figure A4.

Sherd LV29, the best case of the LV vessel (RMSE = 0.023 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A4.

Sherd LV29, the best case of the LV vessel (RMSE = 0.023 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A5.

Sherd LV23, the average case of the LV vessel (RMSE = 0.034 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A5.

Sherd LV23, the average case of the LV vessel (RMSE = 0.034 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A6.

Sherd LV21, the worst case of the LV vessel (RMSE = 0.038 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A6.

Sherd LV21, the worst case of the LV vessel (RMSE = 0.038 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

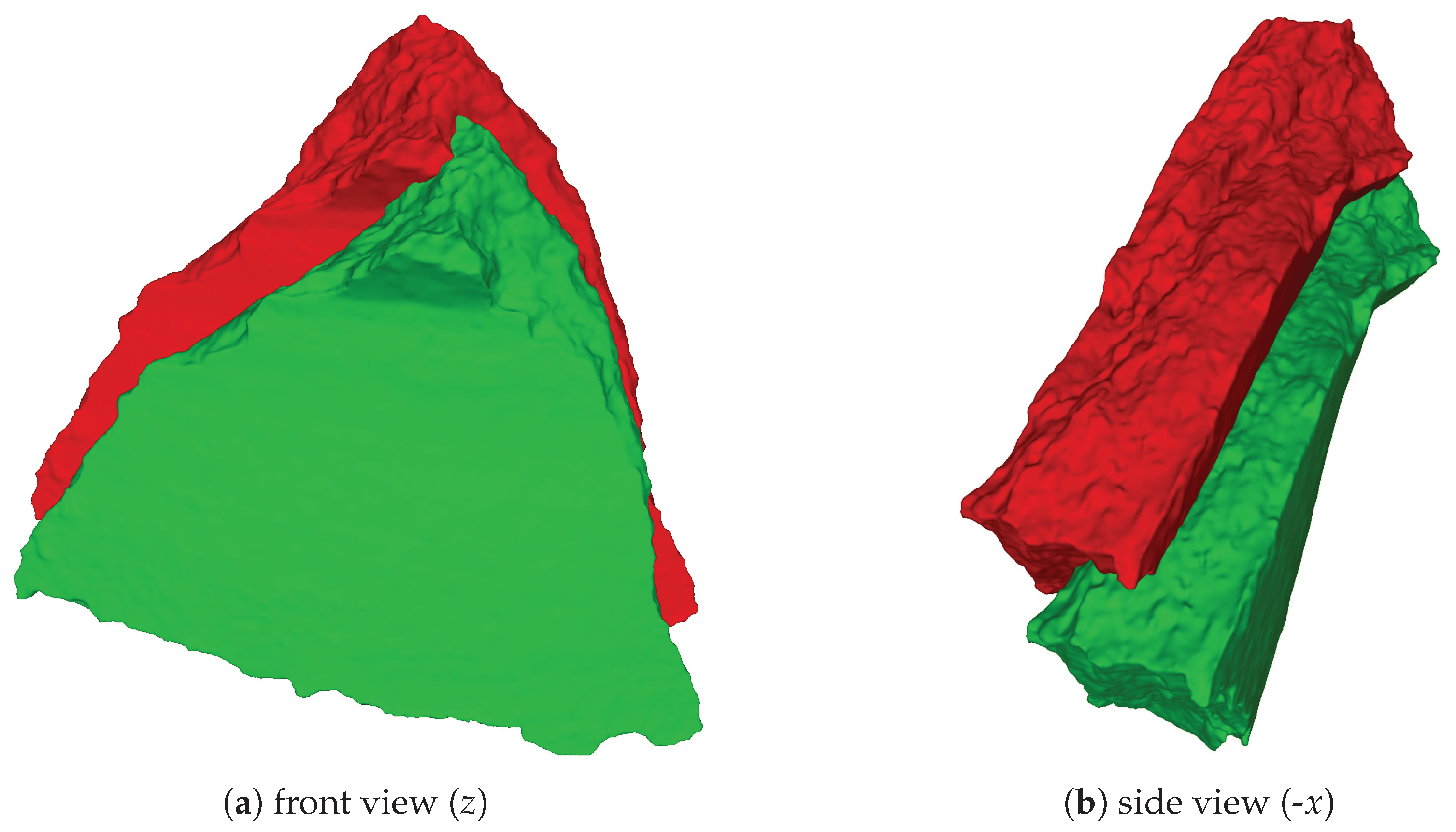

Figure A7.

Sherd MV11, the best case of the MV vessel (RMSE = 0.017 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A7.

Sherd MV11, the best case of the MV vessel (RMSE = 0.017 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A8.

Sherd MV19, the average case of the MV vessel (RMSE = 0.032 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A8.

Sherd MV19, the average case of the MV vessel (RMSE = 0.032 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A9.

Sherd MV17, the worst case of the MV vessel (RMSE = 0.038 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A9.

Sherd MV17, the worst case of the MV vessel (RMSE = 0.038 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A10.

Sherd SV14, the best case of the SV vessel (RMSE = 0.019 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A10.

Sherd SV14, the best case of the SV vessel (RMSE = 0.019 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A11.

Sherd SV21, the average case of the SV vessel (RMSE = 0.027 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A11.

Sherd SV21, the average case of the SV vessel (RMSE = 0.027 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A12.

Sherd SV11, the worst case of the SV vessel (RMSE = 0.033 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

Figure A12.

Sherd SV11, the worst case of the SV vessel (RMSE = 0.033 m), in the expected position (red) and predicted position (green).

| 1 |

Here, we use the right-handed coordinate system as our reference coordinate system with the y axis pointing up, coinciding with the rotation axis. |

References

- Andrews, S.; Laidlaw, D.H. Toward a framework for assembling broken pottery vessels. AAAI/IAAI 2002, 945–946. [Google Scholar]

- Arun, K.S.; Huang, T.S.; Blostein, S.D. Least-squares fitting of two 3-d point sets. IEEE Transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 1987, 698–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, F.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z. Mending broken vessels a fusion between color markings and anchor points on surface breaks. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2016, 75, 3709–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blender. Available online: http://www.blender.org (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Cooper, D.B.; Willis, A.; Andrews, S.; Baker, J.; Cao, Y.; Han, D.; Kang, K.; Kong, W.; Leymarie, F.F.; Orriols, X. Assembling virtual pots from 3d measurements of their fragments. In Proceedings of the 2001 conference on Virtual reality; 2001; pp. 241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Corsini, M.; Cignoni, P.; Scopigno, R. Efficient and flexible sampling with blue noise properties of triangular meshes. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics 2012, 18, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trimesh. Available online: https://trimsh.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Di Angelo, L.; Di Stefano, P.; Guardiani, E. A review of computer-based methods for classification and reconstruction of 3d high-density scanned archaeological pottery. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2022, 56, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, D.; Di Angelo, L.; Di Stefano, P.; Guardiani, E. A semi-automatic reconstruction of archaeological pottery fragments from 2d images using wavelet transformation. Heritage 2021, 4, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, D.; Di Angelo, L.; Di Stefano, P.; Pane, C. Review of computer-based methods for archaeological ceramic sherds reconstruction. Virtual Archaeology Review 2020, 11, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, M.; Heckbert, P.S. Surface simplification using quadric error metrics. In Proceedings of the 24th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques; 1997; pp. 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.X.; Flöry, S.; Gelfand, N.; Hofer, M.; Pottmann, H. Reassembling fractured objects by geometric matching. ACM siggraph 2006 papers 2006, 569–578. [Google Scholar]

- Jylänki, J. An exact algorithm for finding minimum oriented bounding boxes. Semantic Scholar. 2015. Available online: http://clb.confined.space/minobb/minobb.html (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Kampel, M.; Sablatnig, R. 3D puzzling of archeological fragments. Proc. of 9th Computer Vision Winter Workshop; 2004; pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kashihara, K. An intelligent computer assistance system for artifact restoration based on genetic algorithms with plane image features. International Journal of Computational Intelligence and Applications 2017, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, G.; Bilmenoglu, C. Accuracy of 14 intraoral scanners for the all-on-4 treatment concept: a comparative in vitro study. J Adv Prosthodont 2022, 14, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Hong, J., Rhee. Reconstructing the past: Applying deep learning to reconstruct pottery from thousands shards. In Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases. Applied Data Science and Demo Track: European Conference, ECML PKDD 2020, Ghent, Belgium, September 14–18, 2020, Proceedings, Part V; 2021; pp. 36–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Yang, Y. Progressive deep learning framework for recognizing 3d orientations and object class based on point cloud representation. Sensors 2021, 21, 6108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malischewski, S., Schumann, H., Hoffmann, D. Kabsch algorithm. Available online: https://biomolecularstructures.readthedocs.io/en/latest/kabsch/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Marie, I.; Qasrawi, H. Virtual assembly of pottery fragments using moiré surface profile measurements. Journal of Archaeological Science 2005, 32, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, d.B., Otfried, C., Marc, v.K., Mark, O. Computational geometry algorithms and applications, 3rd ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Pymeshlab. Available online: https://pymeshlab.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- O’Rourke, J. Finding minimal enclosing boxes. International journal of computer & information sciences 1985, 14, 183–199. [Google Scholar]

- Palmas, G., Pietroni, N., Cignoni, P., Scopigno, R. A computer-assisted constraint-based system for assembling fragmented objects. Digital Heritage International Congress (Digital-Heritage), IEEE; 2013; pp. 529–536. [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou, G., Karabassi, E.A., Theoharis, T. Theoharis, T. Automatic reconstruction of archaeological finds – a graphics approach. International Conference on Computer Graphics and Artificial Intelligence; 2000; pp. 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.R., Su, H., Mo, K., Guibas, L.J. Pointnet: Deep learning on point sets for 3d classification and segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2017; pp. 652–660. [Google Scholar]

- Ronnegren, J. Real time mesh fracturing using 2d voronoi diagrams. Bachelor of Science in Digital Game Development, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona, Sweden, 20 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ruder, S. An overview of gradient descent optimization algorithms. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.04747 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sakpere, W. 3D reconstruction of archaeological pottery from its point cloud. In Pattern Recognition and Image Analysis: 9th Iberian Conference, IbPRIA 2019, Madrid, Spain, July 1–4, Proceedings, Part I 9; Springer, 2019; pp. 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatopoulos, M.I.; Anagnostopoulos, C.N. 3D digital reassembling of archaeological ceramic pottery fragments based on their thickness profile. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1601.05824 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Straumann. Available online: https://www.straumann.com/clearcorrect/br/pt/discover/virtuo-vivo.html (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Van Loan, C.F. Generalizing the singular value decomposition. SIAM Journal on numerical Analysis 1976, 13, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S., Huang, R., Li, J., Wang, Z. Reassembling 3D thin fragments of unknown geometry in cultural heritage. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2014, 2, 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y., Barnes, C., Lu, J., Yang, J., Li, H. On the continuity of rotation representations in neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 5753; pp. 5745–5753. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).