Submitted:

14 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

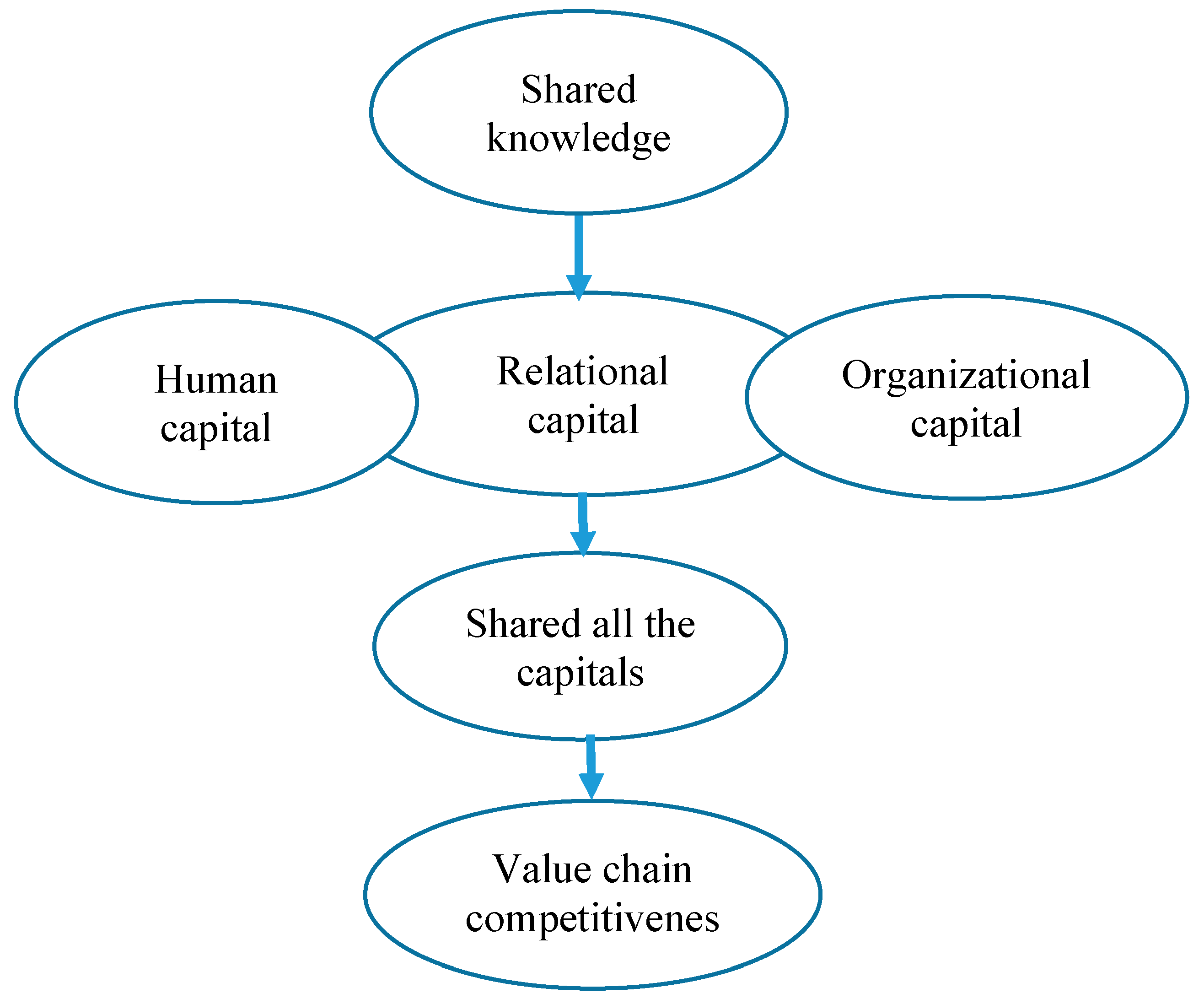

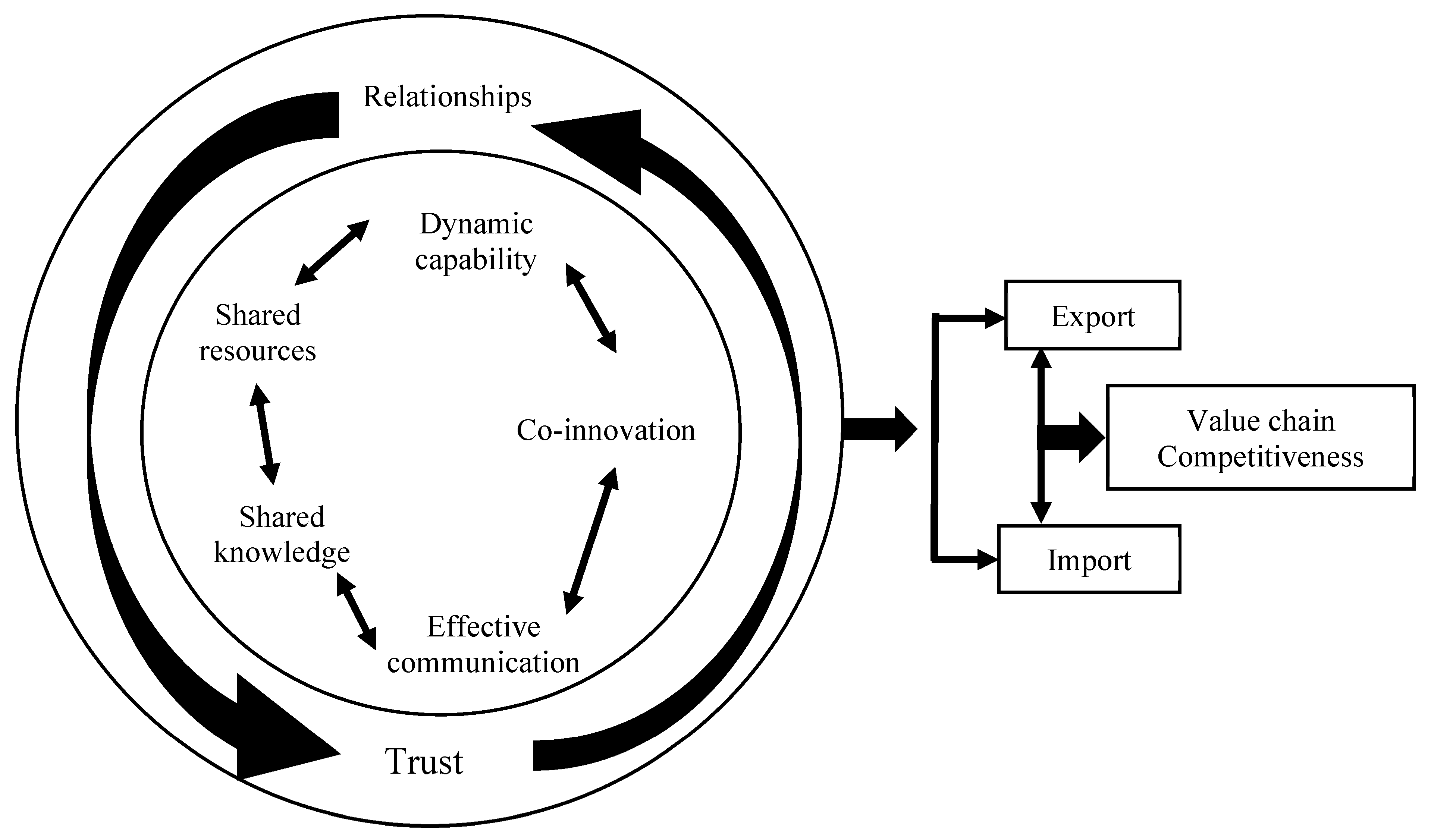

2. Conceptual Framework

3. Methods

3.1. System Boundary

3.2. Qualitative System Dynamic Modelling

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

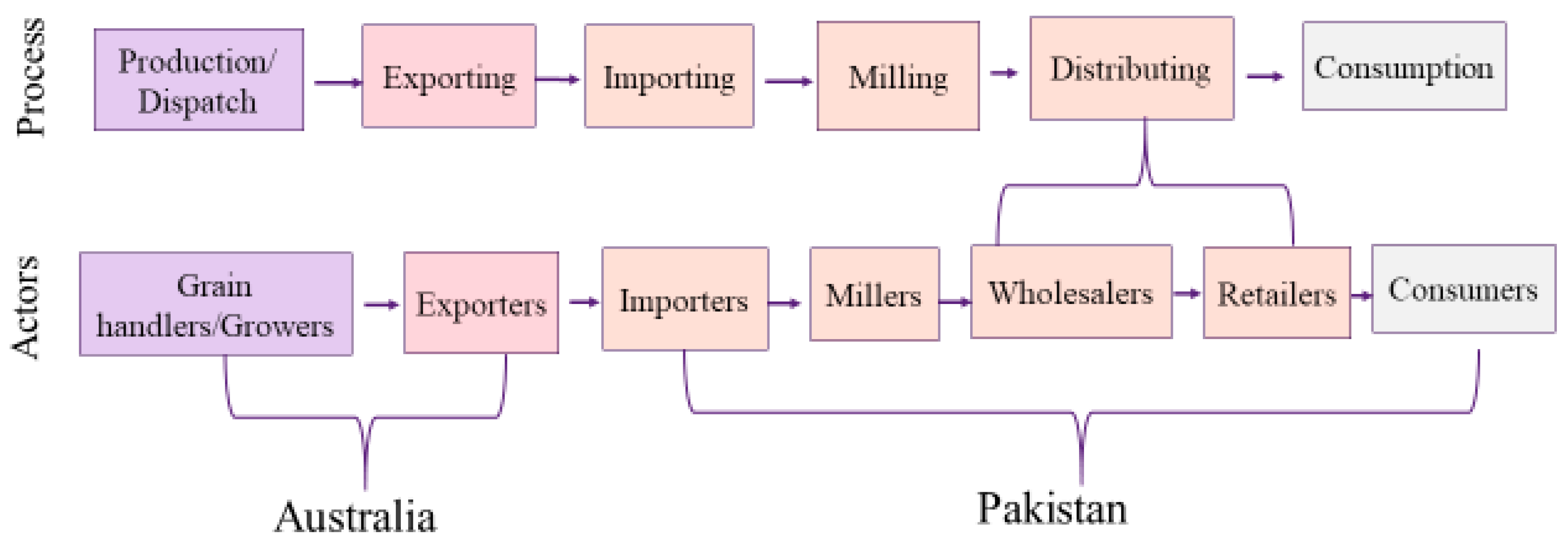

4.1. Value Chain Mapping

4.2. Relationship Components and Their Drivers

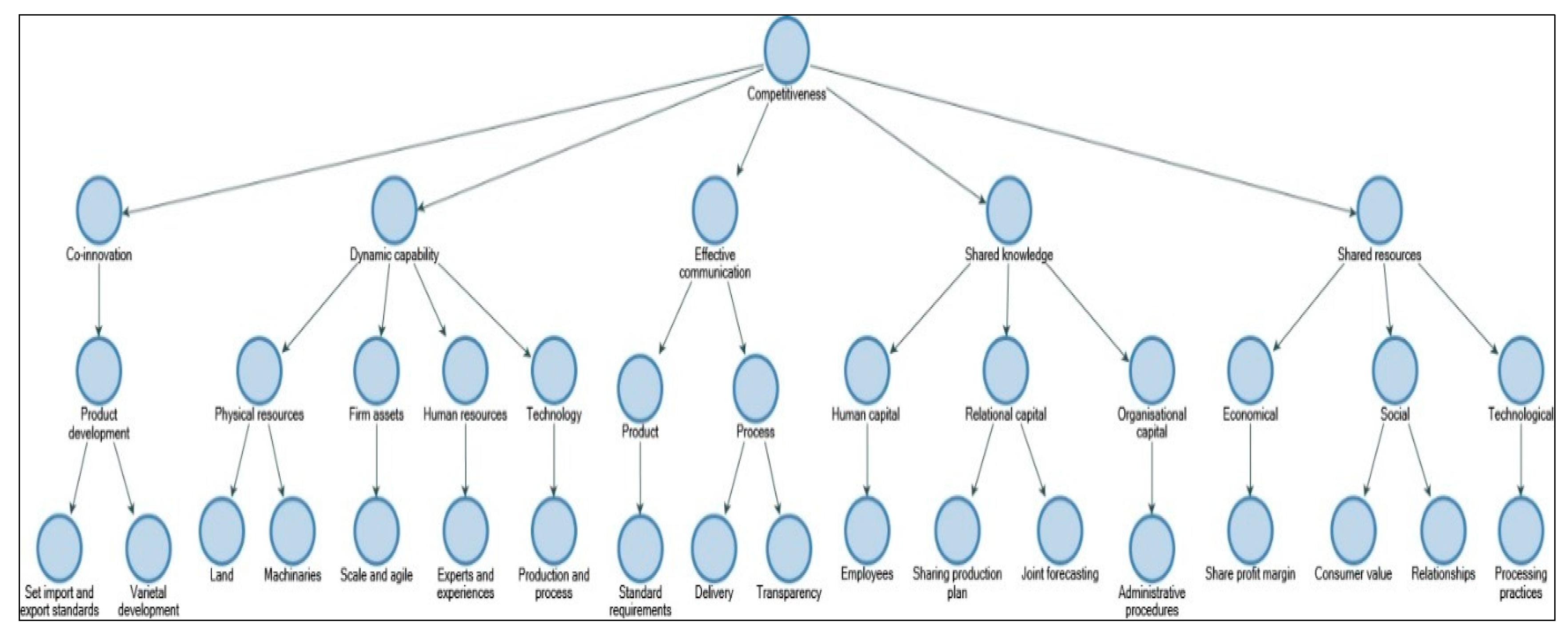

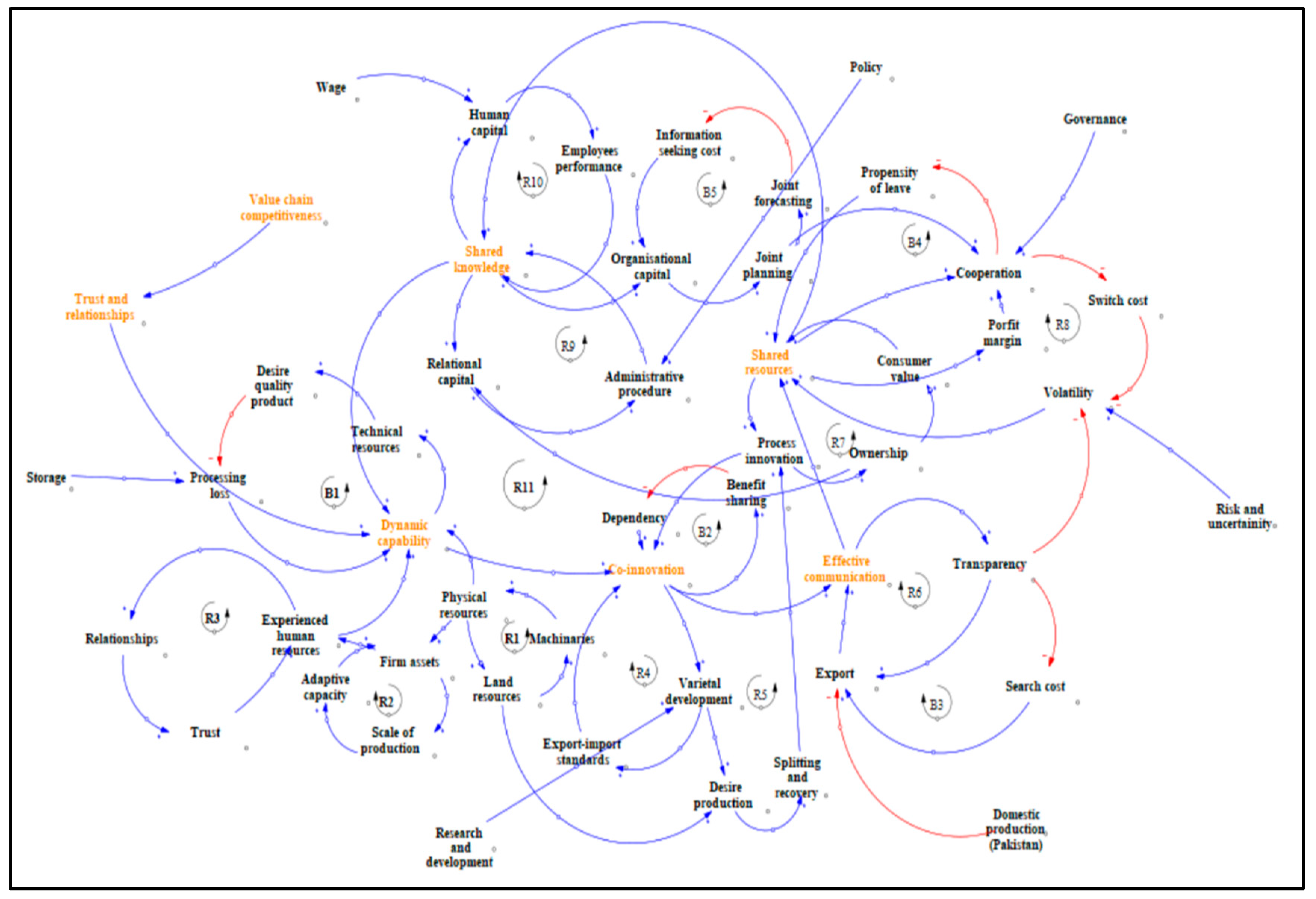

4.3. Dynamic Hypothesis

4.3.1. Co-Innovation

4.3.2. Dynamic Capability

We have been doing pulses trading for the last 20 years; we are better than others because of our dried grain and our number of distributors and outlets (EX1, Personal communication, Aug 2, 2021).

4.3.3. Effective Communication

Australian suppliers are good we have good relations; however, if someone is new, it takes time to build relations and trust. We regularly communicate through WhatsApp(IM3, personal communication, Sept 11, 2021).

Australian, easy communicate, one or alternate we have frequent communication, social media are helping us to communicate frequently (IM2, personal communication, Sept 11, 2021).

4.3.4. Shared Knowledge

Australian exporters are the best in the world; we share knowledge through webinars before and after crop harvest in Pakistan and Australia that helped us in planning. We also talked regularly, especially before shipping(IM4, personal communication, Sept 11, 2021).

4.3.5. Shared Resources

I believe we are consuming domestic lentils and chickpeas, we don’t know if Pakistan also imports lentils and chickpeas, I think many Pakistani consumers are unaware of the overseas pulses they have regularly consumed (CON2, personal communication, Sept 14, 2021).

….it’s a volatile market with very, very low, pretty free cash flow. OK, so that cash flow crunches all the time. So, after that, we actively defaulted on regularly and are managing that default risk, which is the major issue we deal with in Pakistan(EX2, personal communication, Aug 11, 2021).

With the fluctuation in price, sometimes somebody might have bought something at a very high price, and when they seek the goods from us, the price might have fallen hundreds of dollars. For example, buyers have legal contracts with us and then are going to receive goods at a high price all around then, the market is much lower, and they will be losing money when they come to sell those goods they’ve received(EX5, personal communication, Aug 20, 2021).

| Strong | High level of collaboration, a joint effort on problem-solving. | Desired to establish long-term relationships but are guided mainly by short-term profit. |

| Basic | Transactional relationships, although they have an efficient flow of information and frequent communication. | Those partners who are new to the business and motivated by the short-term profit margin. |

| Resources | Shared | Less shared |

5. Discussion

….it’s a volatile market with very, very low, pretty free cash flow. OK, so that cash flow crunches all the time. So, after that, we actively defaulted on regularly and are managing that default risk which is the major issue we deal with in Pakistan(EX2, personal communication, Aug 11, 2021).

Enough cropping areas for pulses production, a large number of distributors and outlets and less delivery cost are our strengths compared to our competitors (EX1, Personal communication, Aug 2, 2021).

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Other statement

Appendix A

| Code of respondent | Stage of Involvement | Experience in the field | Representative country | Interview duration (Minutes: seconds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX1 | Export | 25 | Australia | 27:32 |

| EX2 | Export | 20 | Australia | 34:28 |

| EX3 | Export | 6 | Australia | 13:09 |

| EX4 | Export | 20 | Australia | 39:30 |

| EX5 | Export | 15 | Australia | 31:16 |

| PRA1 | Process | 6 | Australia | 13:09 |

| PRA2 | Process | 20 | Australia | 24:36 |

| PRA3 | Process | 18 | Australia | 20:12 |

| PRA4 | Process | 15 | Australia | 21:12 |

| IM1 | Import | 22 | Pakistan | 15:18 |

| IM2 | Import | 15 | Pakistan | 26:09 |

| IM3 | Import | 20 | Pakistan | 27:32 |

| IM4 | Import | 12 | Pakistan | 23:00 |

| IM5 | Import | 18 | Pakistan | 16:37 |

| PRP1 | Process | 25 | Pakistan | 18:59 |

| PRP2 | Process | 20 | Pakistan | 15:25 |

| WHL1 | Wholesalers | 17 | Pakistan | 14:00 |

| WHL2 | Wholesalers | 25 | Pakistan | 25:00 |

| RT1 | Retailers | 12 | Pakistan | 10:00 |

| RT2 | Retailers | 8 | Pakistan | 11:12 |

| RT3 | Retailers | 18 | Pakistan | 12:14 |

| RT4 | Retailers | 20 | Pakistan | 8:45 |

| RT5 | Retailers | 7 | Pakistan | 5:15 |

| CON1 | Consumption | Life long | Pakistan | 25:51 |

| CON2 | Consumption | Life long | Pakistan | 40:26 |

| CON3 | Consumption | Life long | Pakistan | 16:04 |

| CON4 | Consumption | Life long | Pakistan | 9:56 |

| CON5 | Consumption | Life long | Pakistan | 12:15 |

| Total 28 respondents | ||||

References

- United Nations. "International Trade Statistics Yearbook ": Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division 2023.

- DAFF. "Insight – Australia Is a Key Global Exporter of Pulses." Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, https://www.agriculture.gov.au/about/news/insight-australia-key-global-exporter-pulses#:~:text=Australia's%20pulse%20production%20has%20grown,(876%20kt)%20after%20India. (.

- Sharples, Jerry A, and Nick Milham. "Long-Run Competitiveness of Australian Agriculture." (1990).

- Employsure. "Minimum Wage in Australia." Employsure.com.au (.

- Acciani, C, A De Boni, F Bozzo, and R Roma. "Pulses for Healthy and Sustainable Food Systems: The Effect of Origin on Market Price. Sustainability 2021, 13, 185." s Note: MDPI stays neu-tral with regard to jurisdictional claims in …, 2020. [CrossRef]

- PA. "Australian Pulse Industries (2020 Posters)." Pulse Australia, https://www.pulseaus.com.au/storage/app/media/uploaded-files/PULSEAU004_AGIC%20A1%20Posters_CB2020-opt.pdf (.

- Joshi, PK, and P Parthasarathy Rao. "Global Pulses Scenario: Status and Outlook." Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1392, no. 1 (2017): 6-17.

- Watts, P. "Global Pulse Industry: State of Production, Consumption and Trade; Marketing Challenges and Opportunities." Pulse foods: Processing, quality and nutraceutical applications (2011): 437-64.

- AEGIC. "Australian Pulses." Australia: Australian Export Grains Innovation Centre (AEGIC), 2020.

- DAFF. "Insight – Australia Is a Key Global Exporter of Pulses." Australian Government, Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, 2024.

- Vanzetti, David, Elizabeth Petersen, and Saima Rani. "Pulses Policy in Pakistan: An Empirical Analysis." Pakistan Economic and Social Review 60, no. 1 (2022): 1-21.

- Rani, Saima, Hassnain Shah, Umar Farooq, and Bushra Rehman. "Supply, Demand, and Policy Environment for Pulses in Pakistan." Pakistan J. Agric. Res 27, no. 2 (2014).

- Ullah, Aman, Tariq Mahmud Shah, and Muhammad Farooq. "Pulses Production in Pakistan: Status, Constraints and Opportunities." International Journal of Plant Production 14, no. 4 (2020): 549-69.

- Vanzetti, David, EH Petersen, and Saima Rani. "Economic Review of the Pulses Sector and Pulses-Related Policies in Pakistan." Paper presented at the Mid-Project Workshop of ACIAR Project ADP/2016/140 “How can policy reform remove constraints and increase productivity in Pakistan 2017.

- Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development. "Cropping Pulses." Government of New South Wales, 2024.

- de Vries, Jasper R, James A Turner, Susanna Finlay-Smits, Alyssa Ryan, and Laurens Klerkx. "Trust in Agri-Food Value Chains: A Systematic Review." International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 26, no. 2 (2023): 175-97.

- Marques Vieira, Luciana, and W Bruce Traill. "Trust and Governance of Global Value Chains: The Case of a Brazilian Beef Processor." British Food Journal 110, no. 4/5 (2008): 460-73.

- Trienekens, Jacques H. "Agricultural Value Chains in Developing Countries a Framework for Analysis." International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 14, no. 2 (2011): 51-82.

- Porter, Michael E. "The Value Chain and Competitive Advantage." Understanding business processes 2 (2001): 50-66.

- Kumar, Dilip, and PV Rajeev. "Value Chain: A Conceptual Framework." International journal of engineering and management sciences 7, no. 1 (2016): 74-77.

- Collins, RC, Benjamin Dent, and LB Bonney. "A Guide to Value-Chain Analysis and Development for Overseas Development Assistance Projects." A guide to value-chain analysis and development for overseas development assistance projects. (2016).

- Dong-Jin, Lee, and Jee-In Jang. "The Role of Relational Exchange between Exporters and Importers Evidence from Small and Medium-Sized Australian Exporters." Journal of small business management 36, no. 4 (1998): 12.

- Styles, Chris, Paul G Patterson, and Farid Ahmed. "A Relational Model of Export Performance." Journal of international business studies 39, no. 5 (2008): 880-900.

- O’Connor, Neale G, Sandra C Vera-Muñoz, and Francis Chan. "Competitive Forces and the Importance of Management Control Systems in Emerging-Economy Firms: The Moderating Effect of International Market Orientation." Accounting, Organizations and Society 36, no. 4-5 (2011): 246-66. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Mei-Ying, Yung-Chien Weng, and I-Chiao Huang. "A Study of Supply Chain Partnerships Based on the Commitment-Trust Theory." Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 24, no. 4 (2012): 690-707. [CrossRef]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice: Sage publications, 2014.

- Morgan, Robert M, and Shelby D Hunt. "The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing." Journal of marketing 58, no. 3 (1994): 20-38.

- Collins, Ray, and Benjamin Dent. "Value Chain Management and Postharvest Handling." In Postharvest Handling, 319-41: Elsevier, 2022.

- Chowdhury, Md Maruf H, and Mohammed Quaddus. "Supply Chain Resilience: Conceptualization and Scale Development Using Dynamic Capability Theory." International journal of production economics 188 (2017): 185-204. [CrossRef]

- Masteika, Ignas, and Jonas Čepinskis. "Dynamic Capabilities in Supply Chain Management." Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 213 (2015): 830-35.

- Aboah, Joshua, Mark MJ Wilson, Kathryn Bicknell, and Karl M Rich. "Ex-Ante Impact of on-Farm Diversification and Forward Integration on Agricultural Value Chain Resilience: A System Dynamics Approach." Agricultural Systems 189 (2021): 103043. [CrossRef]

- Muflikh, Yanti Nuraeni, Carl Smith, and Ammar Abdul Aziz. "A Systematic Review of the Contribution of System Dynamics to Value Chain Analysis in Agricultural Development." Agricultural Systems 189 (2021): 103044. [CrossRef]

- Bitzer, Verena, and Jos Bijman. "From Innovation to Co-Innovation? An Exploration of African Agrifood Chains." British Food Journal 117, no. 8 (2015): 2182-99.

- Salmela, Erno, and Janne Huiskonen. "Co-Innovation Toolbox for Demand-Supply Chain Synchronisation." International Journal of Operations & Production Management 39, no. 4 (2019): 573-93.

- Fischer, Christian. "Trust and Communication in European Agri-Food Chains." Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 18, no. 2 (2013): 208-18.

- Talluri, Srinivas, RC Baker, and Joseph Sarkis. "A Framework for Designing Efficient Value Chain Networks." International journal of production economics 62, no. 1-2 (1999): 133-44. [CrossRef]

- Myers, Matthew B, and Mee-Shew Cheung. "Sharing Global Supply Chain Knowledge." MIT Sloan management review (2008).

- Huang, Chun-Che, and Shian-Hua Lin. "Sharing Knowledge in a Supply Chain Using the Semantic Web." Expert Systems with Applications 37, no. 4 (2010): 3145-61. [CrossRef]

- Brandon-Jones, Emma, Brian Squire, Chad W Autry, and Kenneth J Petersen. "A Contingent Resource-Based Perspective of Supply Chain Resilience and Robustness." Journal of supply chain management 50, no. 3 (2014): 55-73. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Long, Cheng-Hung Chuang, and Chien-Hua Hsu. "Information Sharing and Collaborative Behaviors in Enabling Supply Chain Performance: A Social Exchange Perspective." International journal of production economics 148 (2014): 122-32. [CrossRef]

- Sterman, John D. Business Dynamics : Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World. Boston: Irwin/McGraw-Hill, 2000.

- Maani, Kambiz, and R. Y. Cavana. Systems Thinking, System Dynamics : Managing Change and Complexity. 2nd ed. Auckland, N.Z.: Prentice Hall, 2007.

- Welsh, Elaine. "Dealing with Data: Using Nvivo in the Qualitative Data Analysis Process." Paper presented at the Forum qualitative sozialforschung/Forum: qualitative social research 2002.

- Blismas, Nick G, and Andrew RJ Dainty. "Computer-Aided Qualitative Data Analysis: Panacea or Paradox?" Building research & information 31, no. 6 (2003): 455-63.

- Haraldsson, Hörđur V. Introduction to System Thinking and Causal Loop Diagrams: Department of chemical engineering, Lund University Lund, Sweden, 2004.

- Maghsoudi, Amin, and Ala Pazirandeh. "Visibility, Resource Sharing and Performance in Supply Chain Relationships: Insights from Humanitarian Practitioners." Supply Chain Management: An International Journal (2016). [CrossRef]

- Aykol, Bilge, and Leonidas C Leonidou. "Exporter-Importer Business Relationships: Past Empirical Research and Future Directions." International Business Review 27, no. 5 (2018): 1007-21. [CrossRef]

- Van Donk, Dirk Pieter, and Taco Van Der Vaart. "A Case of Shared Resources, Uncertainty and Supply Chain Integration in the Process Industry." International journal of production economics 96, no. 1 (2005): 97-108.

- Daudi, Morice. Trust in Sharing Resources in Logistics Collaboration. Universität Bremen, 2018.

- Ariyawardana, Anoma, and Ray Collins. "Value Chain Analysis across Borders: The Case of Australian Red Lentils to Sri Lanka." Journal of Asia-Pacific Business 14, no. 1 (2013): 25-39. [CrossRef]

- Ilham, Ilham, Badri Munir Sukoco, Anis Eliyana, Tanti Handriana, and Heri Cahyo Bagus Setiawan. "Dynamic Capabilities Information Technology Enabler for Performance Organization." Library Philosophy and Practice (e-Journal) (2021).

- Kamal, Marium. "Institutional Failure: A Challenge to Good Governance in Pakistan." South Asian Studies 35, no. 01 (2020): 101-18.

- Khan, Mushtaq. "State Failure in Developing Countries and Institutional Reform Strategies." Toward pro-poor policies: aid, institutions, and globalization (2004): 165-96.

- Ellis, Frank. Agricultural Policies in Developing Countries: Cambridge university press, 1992.

- Lee, Sang M, David L Olson, and Silvana Trimi. "Co-Innovation: Convergenomics, Collaboration, and Co-Creation for Organizational Values." Management decision (2012).

- Botha, Neels, James A. Turner, Simon Fielke, and Laurens Klerkx. "Using a Co-Innovation Approach to Support Innovation and Learning : Cross-Cutting Observations from Different Settings and Emergent Issues." Outlook on agriculture 46, no. 2 (2017): 87-91. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Morten T, and Julian Birkinshaw. "The Innovation Value Chain." Harvard business review 85, no. 6 (2007): 121-30, 42.

- Kess, Pekka, Kris MY Law, Rapee Kanchana, and Kongkiti Phusavat. "Critical Factors for an Effective Business Value Chain." Industrial Management & Data Systems (2010). [CrossRef]

- De Silva, Harsha, and Dimuthu Ratnadiwakara. "Using Ict to Reduce Transaction Costs in Agriculture through Better Communication: A Case-Study from Sri Lanka." LIRNEasia, Colombo, Sri Lanka, Nov (2008).

- Mohr, Jakki, and Robert Spekman. "Characteristics of Partnership Success: Partnership Attributes, Communication Behavior, and Conflict Resolution Techniques." Strategic management journal 15, no. 2 (1994): 135-52.

- Ferrer, Mario, Ricardo Santa, Paul W Hyland, and Phil Bretherton. "Relational Factors That Explain Supply Chain Relationships." Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics (2010). [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Shu-Mei, and Pei-Shan Lee. "The Effect of Knowledge Management Capability and Dynamic Capability on Organizational Performance." Journal of enterprise information management (2014). [CrossRef]

- Lee, Dong-Jin. "The Effect of Cultural Distance on the Relational Exchange between Exporters and Importers: The Case of Australian Exporters." Journal of Global Marketing 11, no. 4 (1998): 7-22.

| Balancing loops | Variables |

| B1 | Dynamic capability (+) Technical resources (+) Desire quality product (-) Processing loss (+) |

| B2 | Co-innovation (+) Benefit-sharing (-) Dependency (+) |

| B3 | Effective communication (+) Transparency (-) Search cost (+) Export (+) |

| B4 | Shared resources (+) Profit margin (+) Cooperation (-) propensity to leave (+) |

| B5 | Organisational capital (+) Joint Planning (+) Joint forecasting (+) Information seeking cost (-) |

| Reinforcing loops | Variables |

| R1 | Physical resources (+) Land resources (+) Machinery (+) |

| R2 | Firm assets (+) Scale of production (+) Adaptive capacity (+) |

| R3 | Experienced human resources (+) Relationships (+) Trust (+) |

| R4 | Co-innovation (+) Varietal development (+) Export-import standards (+) |

| R5 | Co-innovation (+) Varietal development (+) Desire production (+) Splitting and recovery (+) Process innovation (+) |

| R6 | Effective communication (+) Transparency (+) Export (+) |

| R7 | Shared resources (+) Process innovation (+) Ownership (+) Consumer value (+) |

| R8 | Shared resources (+) Cooperation (+) Switch cost (-) Volatility (-) |

| R9 | Shared knowledge (+) Relational capital (+) Administrative procedure (+) |

| R10 | Shared knowledge (+) Human capital (+) Employee performance (+) |

| R11 | Dynamic capability (+) Co-innovation (+) Effective communication (+) Shared resources (+) Shared knowledge (+) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).