1. Introduction

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) secondary to ischemic cardiomyopathy represents one of the most significant challenges in modern cardiology. This condition contributes to a high number of hospitalizations and is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, making it a critical target for therapeutic advancements [

1]. Patients with concomitant left bundle branch block (LBBB) present an additional layer of complexity, as the disruption in ventricular synchronization leads to mechanical inefficiency and progressive remodeling [

2]. This exacerbates heart failure symptoms, reduces exercise capacity, and increases overall mortality risk.

In LBBB, the delayed activation of the left ventricle results in mechanical dyssynchrony, causing inefficient contraction patterns [

3]. The interventricular septum and lateral wall contract out of sync, leading to paradoxical septal motion that increases ventricular wall stress and accelerates adverse remodeling [

4]. While traditional pacing techniques, such as right ventricular (RV) pacing, address bradycardia, they can often worsen dyssynchrony and further impair cardiac function. Similarly, cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) has demonstrated success in correcting ventricular desynchronization, yet its effectiveness is limited by a considerable non-responder rate and the complexity of implantation [

5].

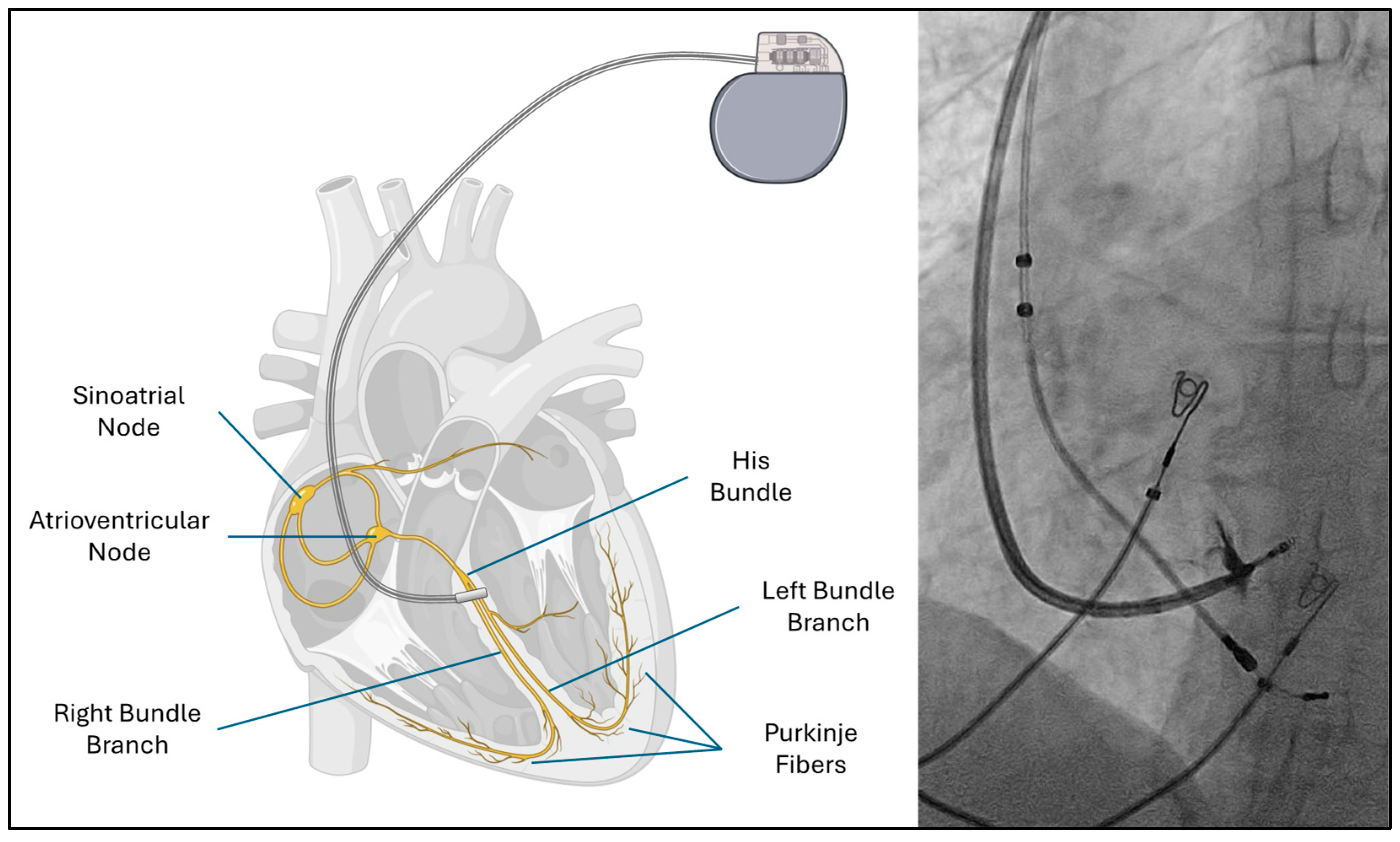

Bundle branch pacing (BBP) has emerged as a physiological alternative that directly engages the native conduction system through His bundle pacing or left bundle branch area pacing [

6] (

Figure 1). By restoring synchronized ventricular activation, BBP improves mechanical function and systemic hemodynamics. Early clinical evidence suggests this technique not only reduces dyssynchrony but also promotes reverse remodeling, decreases hospitalizations, and enhances the quality of life for patients with HFrEF [

7].

2. Pathophysiology of Dyssynchrony in Left Bundle Branch Block

LBBB-induced dyssynchrony involves a complex interplay of electrical, mechanical, hemodynamic, and metabolic disturbances. The loss of synchronized ventricular activation leads to inefficient contraction, impaired relaxation, and structural remodeling, all of which worsen heart failure symptoms and increase arrhythmic risk [

8]. Under normal conditions, the His-Purkinje system ensures rapid and simultaneous activation of both ventricles, allowing coordinated contraction of the interventricular septum and lateral walls, which optimizes cardiac output. However, in LBBB, conduction through the left bundle branch is delayed or blocked, leading to a sequence of detrimental mechanical and hemodynamic changes [

9].

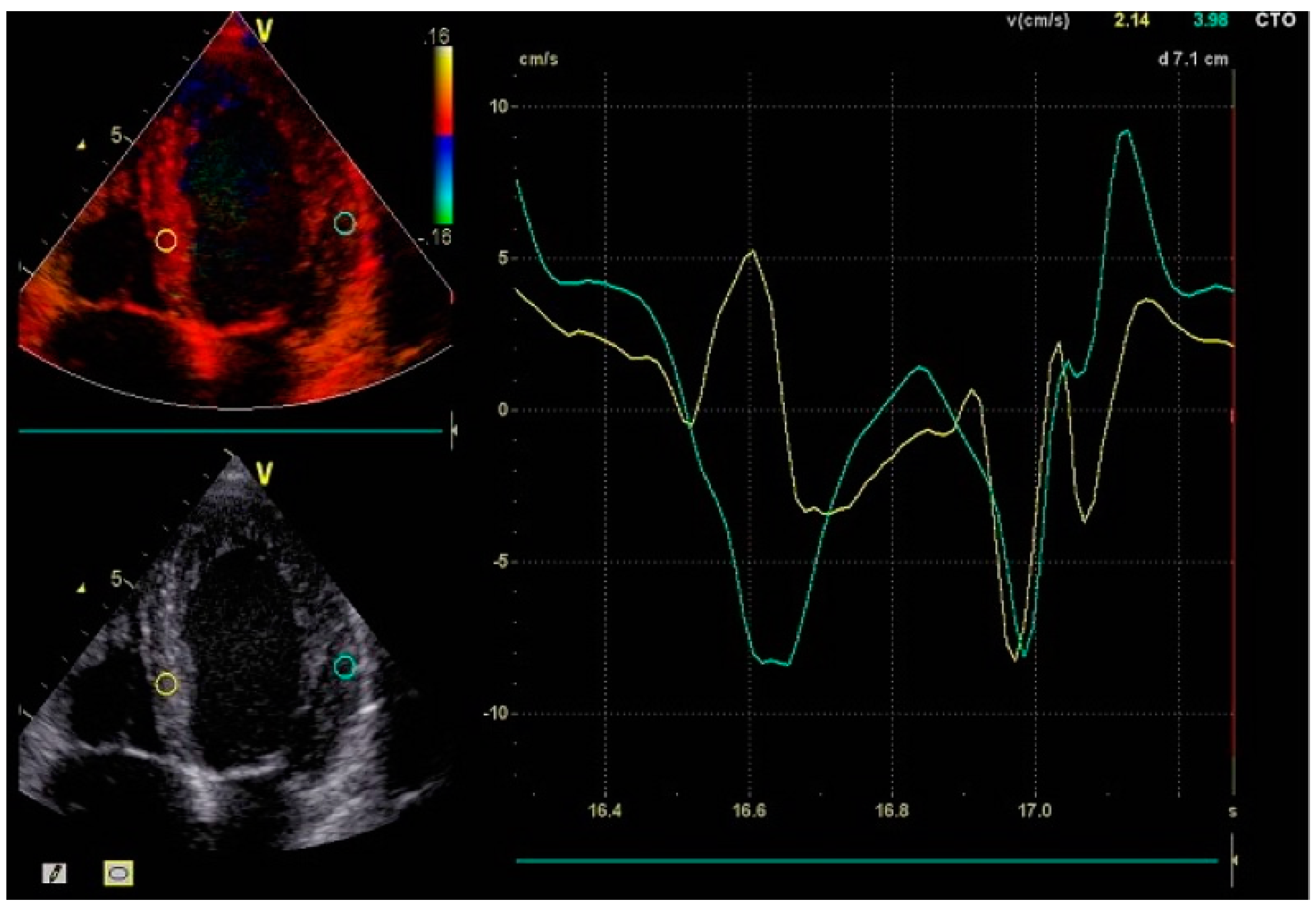

As the right ventricle is activated normally via the right bundle branch, the left ventricle experiences a significant delay in depolarization. This forces electrical impulses to propagate through myocardial tissue rather than the fast-conducting Purkinje fibers, creating interventricular dyssynchrony where the ventricles contract at different times. Within the left ventricle, further desynchronization occurs as the septum and lateral wall contract out of phase. The result is inefficient contraction patterns characterized by early septal activation followed by late lateral wall contraction [

10] (

Figure 2).

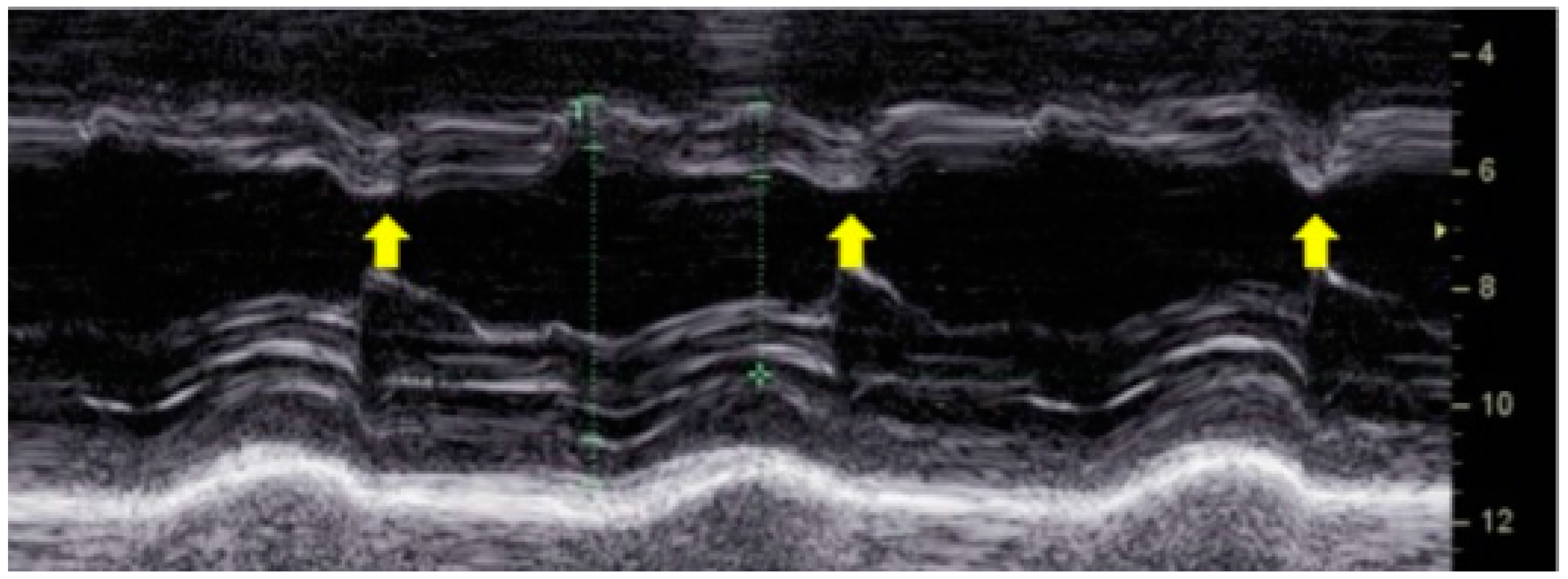

A hallmark feature of LBBB-induced dyssynchrony is paradoxical septal motion. Early contraction of the right ventricle pulls the septum toward the left ventricle, while the delayed lateral wall contraction stretches the septum back toward the right ventricle. This phenomenon, known as "septal flash", is a key echocardiographic finding associated with inefficient myocardial contraction [

11] (

Figure 3). The resulting uncoordinated motion increases myocardial wall stress and reduces left ventricular ejection efficiency, leading to progressive systolic dysfunction.

The mechanical inefficiencies extend beyond septal motion abnormalities. Delayed contraction of the lateral wall prolongs systole, impairing diastolic relaxation and reducing ventricular filling time, ultimately compromising stroke volume and cardiac output [

12].

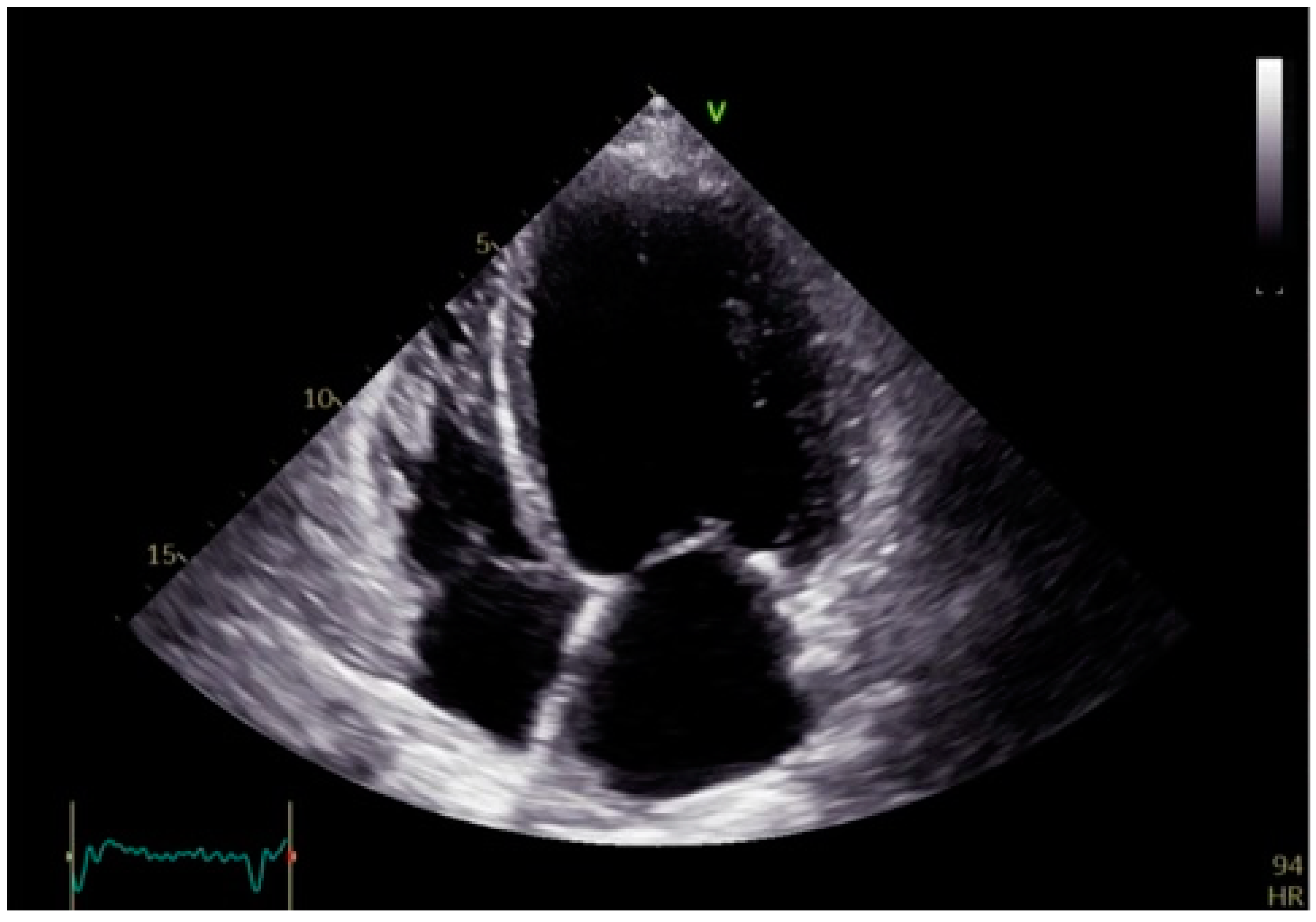

Over time, the increased workload and wall stress lead to adverse remodeling, including left ventricular dilation, hypertrophy, and fibrosis (

Figure 4). These structural changes further deteriorate heart failure symptoms, heighten arrhythmic risk, and contribute to poor clinical outcomes [

13].

The hemodynamic burden imposed by dyssynchrony in LBBB is substantial. The loss of coordinated contraction reduces ventricular pump efficiency, leading to impaired systemic perfusion. Consequently, patients develop elevated left ventricular end-diastolic pressures, which contribute to pulmonary congestion and secondary right ventricular dysfunction. This perpetuates a cycle of worsening heart failure, limiting exercise capacity and increasing hospitalization rates.

Beyond mechanical and hemodynamic effects, LBBB-induced dyssynchrony also disrupts myocardial metabolism and perfusion [

14]. The inefficient contraction pattern leads to suboptimal myocardial energy utilization, increasing oxygen demand while delivering less effective systolic function. Additionally, prolonged systole encroaches on diastolic time, disrupting coronary perfusion and exacerbating ischemia, particularly in patients with underlying coronary artery disease.

Clinical studies indicate that patients with LBBB experience a more rapid decline in left ventricular function compared to those with normal conduction. Moreover, LBBB is associated with an increased risk of sudden cardiac death, as its dyssynchronous activation pattern creates a substrate for malignant ventricular arrhythmias [

15]. All these factors emphasize the need for effective interventions to restore electrical synchrony in patients with heart failure.

Advancements in imaging techniques such as Tissue Doppler Imaging (TDI), speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE), and global longitudinal strain (GLS) have improved the ability to quantify dyssynchrony, enabling better patient selection for resynchronization therapies.

3. Imaging Modalities for Assessing Dyssynchrony

Although a QRS duration of ≥130 milliseconds on electrocardiography is a key criterion for BBP suitability [

16], echocardiographic advancements have greatly enhanced the assessment of ventricular mechanics and their response to treatment in patients with LBBB and HFrEF. Imaging plays a pivotal role in guiding patient selection for BBP or CRT, predicting treatment response, and monitoring the long-term success of resynchronization therapy [

17]. The ability to detect subtle changes in myocardial mechanics, such as GLS improvements or reductions in septal-to-lateral delay, allows for individualized therapy optimization, ultimately improving patient outcomes [

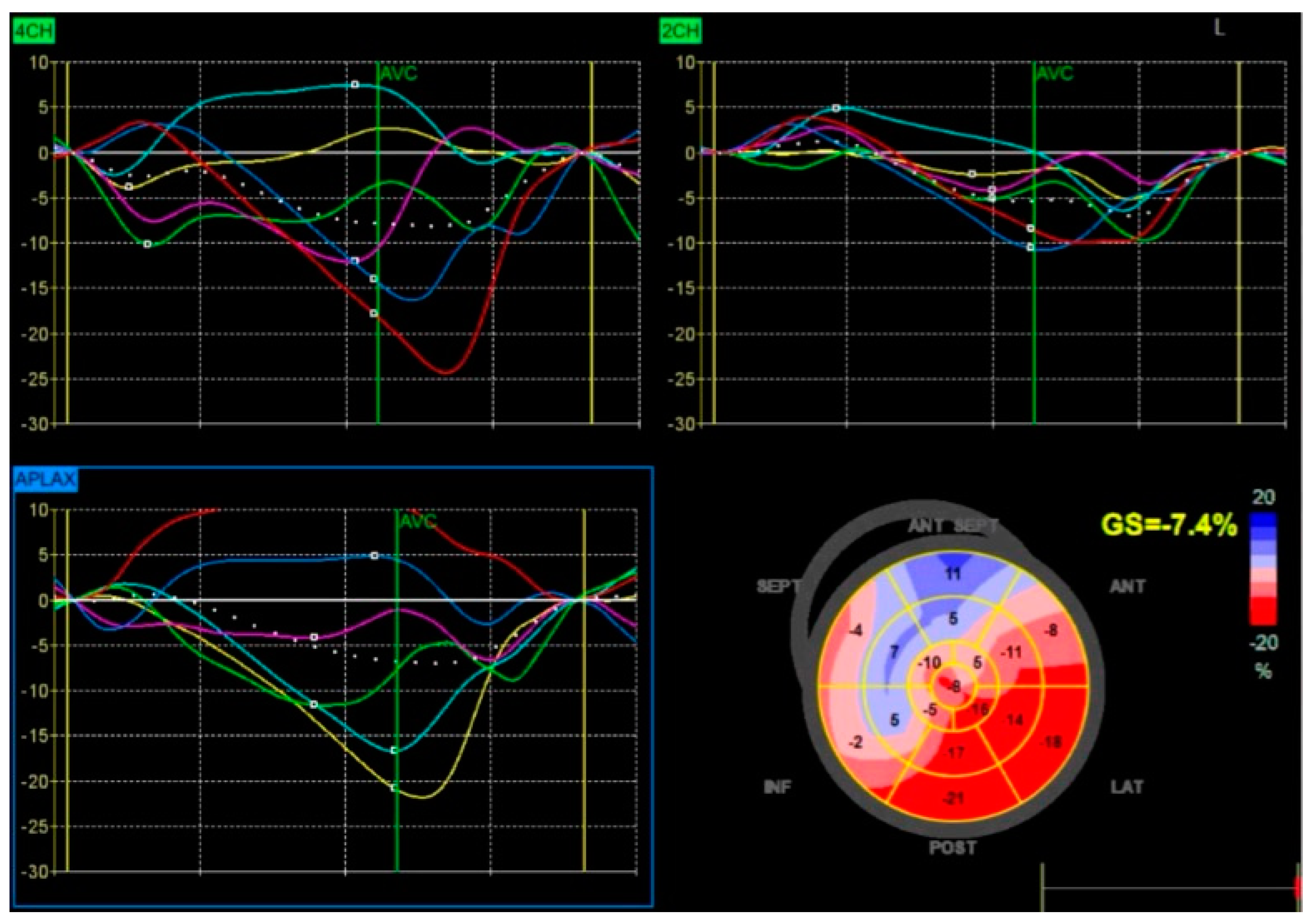

18] (

Figure 5).

Tissue Doppler Imaging: TDI is a widely used modality for evaluating dyssynchrony by measuring myocardial velocities at different ventricular segments. This technique assesses the time-to-peak systolic velocity between the interventricular septum and the left ventricular (LV) lateral wall, providing an objective measure of intraventricular delay. In LBBB, this delay frequently exceeds 65 milliseconds, highlighting significant desynchronization [

19].

A key finding in TDI is paradoxical septal motion, where early septal stretching is followed by delayed contraction due to premature right ventricular activation. This inefficient movement pattern is a hallmark of LBBB and contributes to mechanical dysfunction. TDI also enables a more comprehensive evaluation of dyssynchrony across other myocardial regions, such as the anterior and posterior walls, and serves as a valuable tool for monitoring improvements after CRT or BBP.

Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography: STE provides a refined evaluation of myocardial deformation by analyzing strain and strain rate. Unlike TDI, which measures myocardial velocities, STE evaluates the percentage change in myocardial length during contraction, offering a more precise assessment of ventricular mechanics [

20].

In LBBB, GLS is often significantly reduced due to asynchronous myocardial contraction. STE generates strain maps illustrating areas of delayed or paradoxical motion. The interventricular septum typically exhibits reduced or negative strain in early systole, while the lateral wall demonstrates delayed peak strain, underscoring the extent of dyssynchrony [

21]. This quantitative analysis aids in determining a patient’s likelihood of responding to resynchronization therapy.

STE has several advantages over TDI, including angle independence and greater accuracy in detecting subclinical LV dysfunction. Improvements in GLS following BBP or CRT are strongly correlated with better clinical outcomes, including enhanced LVEF, reduced ventricular volumes, and improved functional capacity [

22].

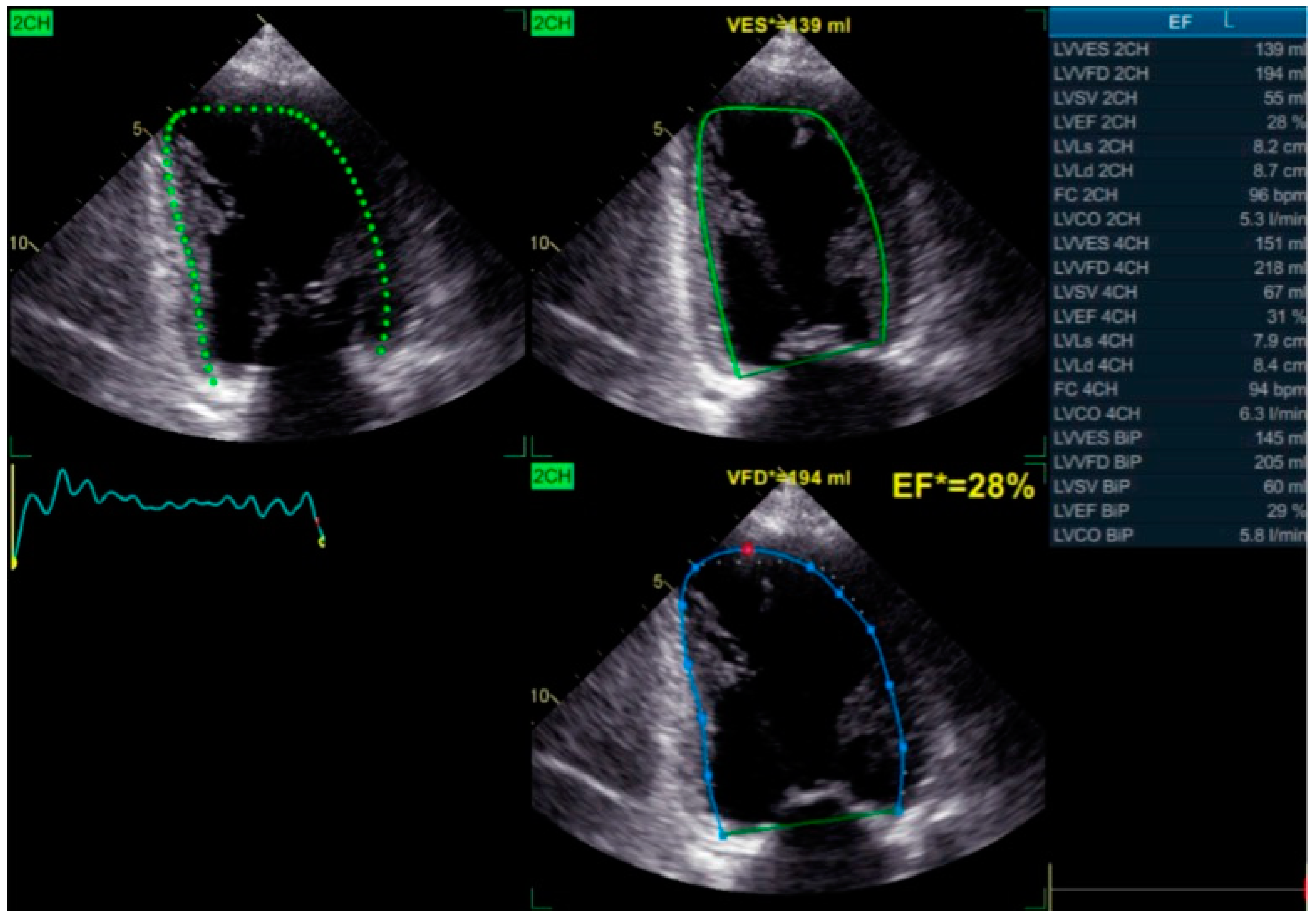

Simpson’s Method for Ejection Fraction Assessment: The biplane method of discs, or Simpson’s method, remains a cornerstone for evaluating global LV function, particularly left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). This technique calculates LVEF based on end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes obtained from apical two- and four-chamber views (

Figure 6).

In patients with LBBB, LVEF is frequently reduced due to inefficient contraction patterns. While Simpson’s method is less sensitive than TDI or STE in detecting regional dyssynchrony, it remains essential for assessing overall ventricular performance. Declining LVEF reflects adverse remodeling, whereas improvements following BBP or CRT indicate successful resynchronization and enhanced cardiac function.

Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion (TAPSE): TAPSE is an essential echocardiographic measure of RV function, assessing the longitudinal movement of the tricuspid annulus during systole. In patients with LBBB and heart failure, TAPSE is often reduced due to increased RV workload caused by elevated pulmonary pressures and impaired ventricular interaction.

LBBB-related dyssynchrony indirectly affects RV function by increasing LV filling pressures, leading to secondary pulmonary hypertension and further deterioration of RV contractility. A reduction in TAPSE suggests worsening RV performance, while improvements post-BBP or CRT indicate better ventricular coupling, reduced pulmonary congestion, and enhanced hemodynamics.

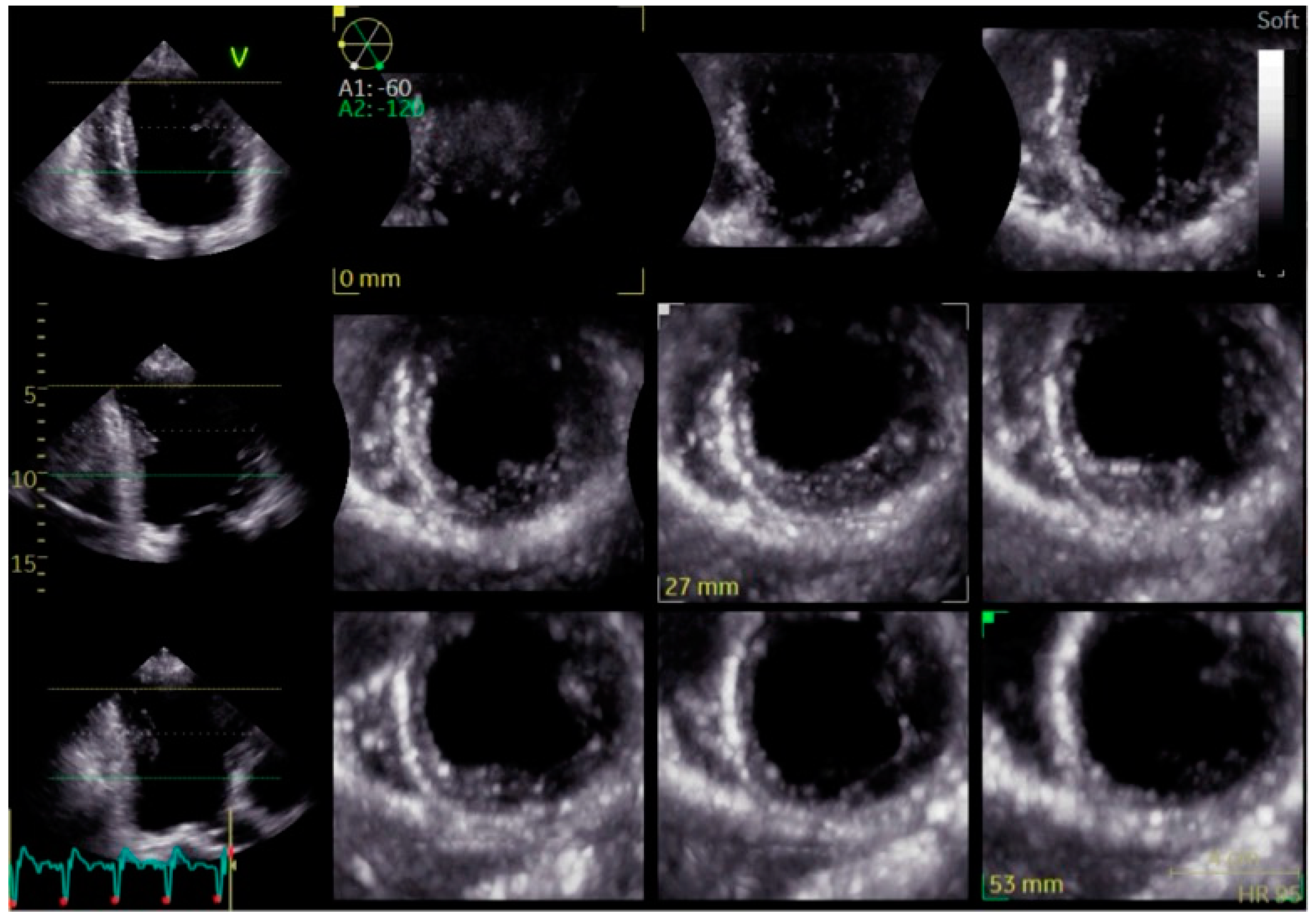

Three-Dimensional Echocardiography (3D Echo): Three-dimensional echocardiography provides an advanced volumetric analysis of ventricular mechanics, offering a more comprehensive evaluation of dyssynchrony than conventional two-dimensional methods (

Figure 7). Unlike standard echocardiography, 3D imaging captures time-to-peak contraction across multiple myocardial segments, allowing for a more detailed assessment of intraventricular coordination.

In LBBB, 3D echocardiography reveals the extent of mechanical dyssynchrony and its impact on ventricular geometry and volumes. This modality is particularly useful for tracking the effects of BBP or CRT, as it can detect subtle changes in ventricular function and remodeling over time. While its availability and expertise requirements currently limit widespread use, 3D Echo is expected to play an increasing role in dyssynchrony assessment and resynchronization therapy optimization.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (CMR): CMR remains the gold standard for assessing myocardial structure, ventricular volumes, and fibrosis. While echocardiography is the primary modality for dyssynchrony assessment, CMR provides superior accuracy in quantifying ventricular mass, identifying regional wall abnormalities, and detecting myocardial fibrosis [

24]. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging is particularly useful for identifying areas of fibrosis, which may impact the effectiveness of BBP or CRT [

25]. Patients with extensive myocardial scarring are less likely to benefit from conduction system pacing, as fibrotic tissue disrupts the transmission of pacing impulses.

In cases where echocardiographic findings are inconclusive, CMR offers additional insights into ventricular remodeling and structural abnormalities that contribute to mechanical inefficiency.

4. Clinical Outcomes of Bundle Branch Pacing

By restoring native conduction, BBP synchronizes ventricular activation, leading to significant improvements in symptom control, functional capacity, hospitalization rates, and reverse remodeling [

26]. Furthermore, BBP provides systemic benefits, enhancing quality of life and long-term survival in patients with HFrEF and LBBB [

27].

Patients with HFrEF and LBBB often experience dyspnea, fatigue, and exercise intolerance, which severely limit daily activities. The restoration of synchronized ventricular contraction via BBP enhances cardiac efficiency and reduces myocardial wall stress, alleviating heart failure symptoms.

One of the most widely documented benefits of BBP is improvement in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class. Many patients experience an upgrade of at least one NYHA class post-implantation, reflecting a clinically meaningful reduction in symptom burden and greater exercise tolerance [

28]. The six-minute walking test also demonstrates notable increases in walking distance and reduced dyspnea following implantation. These gains translate into improved overall well-being, as patients regain the ability to perform daily activities with less fatigue [

29].

Heart failure decompensation leading to hospitalizations is a major burden for both patients and healthcare systems. Recurrent admissions are associated with progressive cardiac decline, worsening comorbidities, and increased mortality risk. BBP has been shown to significantly lower hospitalization rates by stabilizing heart failure symptoms, improving hemodynamics, and preventing disease progression [

30]. Studies report up to a 50% reduction in heart failure-related hospitalizations following BBP implantation, underscoring its potential to decrease healthcare costs and improve long-term outcomes [

31].

Unlike conventional RV pacing, which can exacerbate adverse remodeling [

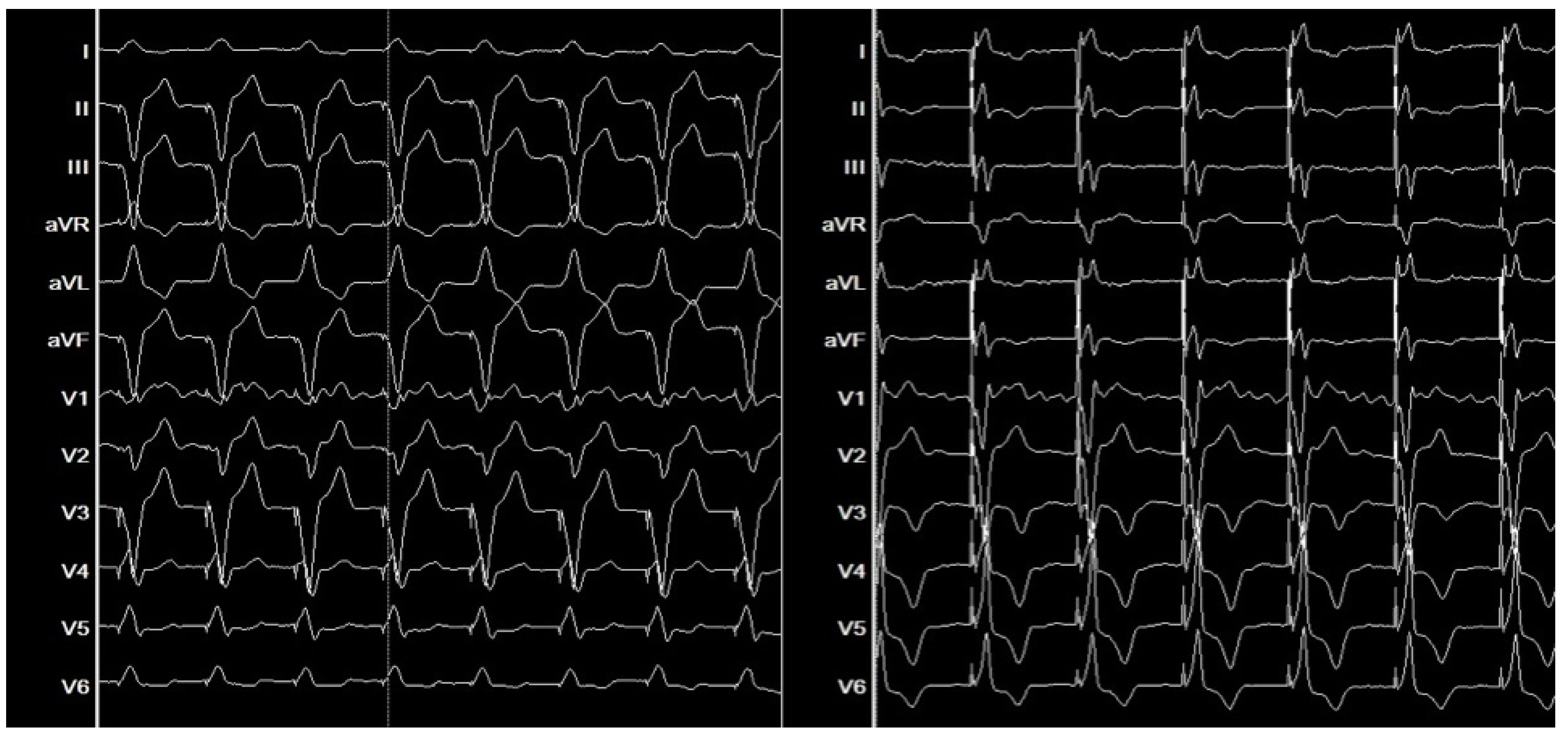

32], BBP preserves natural ventricular activation, preventing further deterioration. In LBBB, prolonged QRS duration is a marker of dyssynchrony and inefficient contraction. By engaging the His-Purkinje system, BBP narrows QRS duration, synchronizing ventricular activation and enhancing myocardial performance [

33] (

Figure 8).

Electrocardiographic improvements post-BBP are not merely cosmetic but reflect fundamental enhancements in cardiac electrophysiology and mechanical function. Studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between QRS narrowing and improved hemodynamics, further supporting BBP as an effective resynchronization strategy [

34].

Beyond cardiac improvements, BBP positively influences other organ systems, particularly the kidneys and pulmonary circulation.

HFrEF patients frequently develop renal impairment due to chronic hypoperfusion and congestion. BBP enhances cardiac output, improving renal perfusion and resulting in lower creatinine levels and increased eGFR [

35].

BNP and NT-proBNP, markers of myocardial wall stress and fluid overload, significantly decrease post-BBP, indicating improved hemodynamics and reduced congestion [

36].

Patients often report better mental clarity, reduced fatigue, and enhanced energy levels, reflecting improved systemic perfusion.

All these benefits translate into increased long-term survival for patients with HFrEF and LBBB [

37].

Although further research is needed to establish definitive long-term survival benefits, current evidence indicates BBP provides comparable or superior outcomes to CRT in selected patients, positioning it as a cornerstone therapy for conduction disturbances in heart failure.

5. Echocardiographic Selection Criteria and Evidence of Reverse Remodeling Following Bundle Branch Pacing

While BBP is an effective and physiological pacing strategy for many patients with HFrEF and LBBB, not all individuals are suitable candidates. A thorough echocardiographic evaluation is essential to identify anatomical, structural, or functional limitations that could reduce procedural feasibility, limit clinical efficacy, or increase the risk of complications [

38]. Recognizing these challenges ensures that alternative pacing strategies, such as CRT or biventricular pacing, are considered in cases where BBP may not provide optimal benefits.

A major limitation to BBP candidacy is the extent of left ventricular fibrosis, particularly in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy or advanced non-ischemic cardiomyopathies. When myocardial scarring disrupts the conduction system, the pacing stimulus may fail to propagate efficiently, making it difficult to achieve stable ventricular synchronization [

39]. CMR imaging with LGE is the gold standard for detecting fibrosis, but echocardiography can also provide useful clues, including severe wall motion abnormalities, interventricular septal thinning below 6 mm, and reduced myocardial strain on STE [

40]. A lack of contractile reserve on stress echocardiography further suggests that the affected myocardium is unable to respond effectively to pacing. In patients with transmural fibrosis, particularly in the septal or basal regions, conduction system capture may be unreliable or ineffective, making CRT a more appropriate alternative as it bypasses diseased pathways and provides broader electrical activation [

41].

Another factor limiting the success of BBP is severe left ventricular dilation, commonly observed in advanced heart failure. When left ventricular end-diastolic diameter exceeds 70 mm or left ventricular end-systolic diameter is greater than 60 mm, the extensive remodeling may prevent the pacing stimulus from effectively reaching the left bundle branch, reducing the likelihood of achieving synchronized ventricular activation. In such cases, biventricular pacing through CRT may be a more reliable alternative, as it directly stimulates both ventricles and compensates for structural and mechanical alterations present in advanced heart failure.

The interventricular septum plays a crucial role in BBP lead fixation and conduction system engagement, and abnormalities in this region can interfere with pacing effectiveness. Patients with marked septal thinning, akinesia, or paradoxical septal motion without contractile reserve may struggle to achieve stable pacing outcomes [

42]. Additionally, the presence of extensive septal fibrosis detected on speckle-tracking or stress echocardiography may indicate that the conduction system is too damaged for BBP to provide meaningful hemodynamic improvements.

Right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension also present challenges for BBP candidacy, as these conditions often indicate broader biventricular failure, which may limit the benefits of left-sided resynchronization alone. Echocardiographic parameters such as TAPSE below 10 mm, right ventricular fractional area change under 20%, moderate-to-severe tricuspid regurgitation, and pulmonary artery systolic pressures exceeding 50 mmHg suggest that right ventricular impairment may reduce the overall hemodynamic benefits of BBP [

43]. In such cases, CRT is often preferred because it supports both ventricles and improves biventricular function more comprehensively.

Elderly patients, especially those with severe diastolic dysfunction and restrictive filling patterns, may also experience limited symptomatic relief from BBP, as their left ventricles operate at persistently elevated filling pressures despite restoring electrical synchrony [

44]. Mitral inflow Doppler patterns showing an E/A ratio greater than 2, an elevated E/e’ ratio above 14, or severe left atrial enlargement exceeding 50 mm indicate advanced diastolic dysfunction, which may not significantly improve with BBP alone. In such cases, CRT may offer greater symptomatic relief, particularly when atrial remodeling or restrictive physiology is a predominant factor in the patient’s heart failure progression.

Venous anatomy and pacing lead positioning are also critical considerations for BBP feasibility, as structural challenges can complicate implantation and reduce procedural success [

45]. Prominent moderator bands or excessive septal trabeculation can interfere with lead fixation, making it difficult to achieve stable conduction system capture. Similarly, atrial septal patches or prosthetic valves can create physical barriers that prevent optimal lead placement [

46]. In these situations, alternative pacing approaches, such as CRT or biventricular pacing, may provide more consistent and reliable resynchronization. A comprehensive echocardiographic evaluation ultimately allows for optimized patient selection, ensuring that each intervention is tailored to the patient’s specific cardiac pathology, improving long-term outcomes and quality of life [

47].

Despite these limitations, BBP has been shown to promote reverse remodeling in appropriately selected patients. Echocardiographic assessments following BBP implantation demonstrate marked reductions in left ventricular end-diastolic volume and left ventricular end-systolic volume, reflecting a shift away from pathological dilation and a return to more efficient ventricular mechanics [

48]. This structural improvement alleviates the burden on the heart and supports better hemodynamic performance.

In addition to volumetric changes, myocardial strain analysis provides valuable insights into BBP’s role in reversing dyssynchrony. STE has shown that BBP significantly improves GLS by enhancing the coordination of myocardial contraction. This improvement is closely linked to the restoration of electrical synchrony, aligning the contraction of the septum and lateral wall. Notably, GLS has been identified as a strong predictor of clinical outcomes in heart failure, with improvements following BBP correlating with better functional capacity, fewer symptoms, and increased survival [

49].

Post-implantation echocardiography frequently demonstrates synchronous septal and lateral wall contraction, leading to more effective systolic function. This correction is particularly evident in TDI, which reveals resolution of early systolic stretching and delayed contraction in the septum. The normalization of wall motion reduces myocardial stress and enhances overall pump efficiency, which is essential for long-term cardiac recovery.

Another key structural benefit of BBP is the reversal of increased ventricular sphericity, another hallmark of progressive remodeling in HFrEF. As the LV dilates, its shape changes from an ellipsoid to a more spherical configuration, increasing wall stress and further impairing contraction. BBP has been shown to restore a more favorable ventricular geometry, reducing wall tension and improving contractile mechanics [

50]. This shift supports better overall LV function and contributes to the long-term benefits of BBP in heart failure management.

6. Biomolecular Effects of Bundle Branch Stimulation

Beyond the well-documented mechanical and electrical benefits, BBP induces a series of biomolecular changes that affect myocardial remodeling, cellular metabolism, and electrical stability [

51].

One of the most significant effects of BBP is its ability to modulate fibrotic remodeling [

52]. In ischemic HFrEF, the loss of cardiomyocytes due to ischemic events and the persistent neurohormonal activation lead to excessive collagen deposition in the extracellular matrix, resulting in increased left ventricular stiffness and progressive deterioration of contractile function [

53]. This fibrotic process is primarily mediated by the overexpression of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β1) and the activation of cardiac fibroblasts [

54]. By promoting a more coordinated contraction, bundle branch stimulation reduces mechanical stress disparities on the ventricular walls, limiting TGF-β1 activation and modulating the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their inhibitors (TIMPs) [

55]. This mechanism slows down fibrotic progression and helps preserve better left ventricular compliance.

Another crucial aspect is the improvement of intracellular calcium homeostasis. In patients with ischemic HFrEF and LBBB, myocardial calcium release is disorganized due to asynchronous left ventricular activation [

56]. This disruption compromises contractility and relaxation, contributing to diastolic dysfunction. BBP restores a more physiological activation sequence, enhancing the synchronization of calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum through ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2) and increasing the activity of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca²⁺-ATPase (SERCA2a) [

57]. This process improves calcium reuptake, leading to enhanced myocardial contraction and relaxation efficiency.

Simultaneously, BBP induces metabolic adaptations in ischemic myocardium. The electrical-mechanical decoupling in LBBB increases energy consumption, which, under chronic ischemic conditions, exacerbates the metabolic deficit in cardiomyocytes [

58]. CRT and BBP reduce this energy expenditure by improving contraction coordination and optimizing subendocardial perfusion [

59]. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that resynchronization can enhance mitochondrial function, reducing oxidative stress and limiting cellular damage from free radicals [

60].

Another major impact of bundle branch stimulation is its modulation of neurohormonal pathways, which are severely dysregulated in ischemic HFrEF. Chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system contributes to pathological cardiac remodeling, increasing left ventricular workload and promoting heart failure progression [

61]. BBP mitigates sympathetic overactivation, reducing circulating norepinephrine levels and enhancing parasympathetic tone. These effects not only improve cardiac function but also decrease the risk of arrhythmic events, which are often linked to excessive sympathetic activity [

62].

Finally, a critical aspect of BBP is its influence on electrical stability in ischemic myocardium. Ischemic LBBB is associated with altered expression of connexins (Cx43, Cx45), the proteins responsible for electrical conduction between cardiomyocytes. This disorganization increases repolarization heterogeneity, predisposing patients to ventricular arrhythmias [

63]. Both CRT and BBP restore connexin expression and distribution, improving electrical signal transmission and reducing the risk of ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation [

64].

7. Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its promising benefits, BBP faces challenges related to procedural complexity and patient selection. Implantation requires precise mapping and lead placement, which can be technically demanding. Variability in response among patients underscores the need for improved selection criteria, particularly in identifying individuals with extensive myocardial scarring. Future research should focus on refining implantation techniques, standardizing protocols, and conducting large-scale trials to establish the long-term benefits and safety of BBP. Advances in imaging technology and mapping tools may further enhance the precision and success of this innovative approach.

8. Conclusions

BBP is a transformative innovation in the management of HFrEF and LBBB. The effects of BBP go beyond merely correcting electrical activity detectable on ECG. BBP significantly improves left ventricular performance by enhancing synchrony and reducing mechanical inefficiencies. Additionally, its biomolecular effects play a crucial role in slowing the progression of HFrEF by modulating myocardial remodeling, optimizing calcium handling, and reducing oxidative stress. These combined benefits contribute to better long-term cardiac function and patient outcomes.

For these reasons, BBP represents a paradigm shift in the management of conduction disturbances in heart failure, offering a more physiological and effective alternative to conventional pacing strategies. With continued advancements in imaging, device technology, and patient selection criteria, BBP is poised to become a cornerstone therapy in the management of HFrEF with LBBB, ultimately improving outcomes for this high-risk patient population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C.; methodology, F.C., I.C., C.M., M.V., S.C. and S.A.; software, V.C. and C.P.; validation, F.C.; formal analysis, F.C. and I.C.; investigation, F.C., M.V. and C.M.; resources, O.M. and C.P.; data curation, F.C. and I.C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C.; writing—review and editing, F.C.; visualization, C.M.; supervision, M.V. and C.M.; echocardiographical evaluations, F.C. and I.C.; electrophysiological evaluations, F.C., S.C. and M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BBP |

Bundle Branch Pacing |

| HFrEF |

Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction |

| TDI |

Tissue Doppler Imaging |

| STE |

Speckle Tracking Imaging |

| GLS |

Global Longitudinal Strain |

| CRT |

Cardiac Resyncronization Therapy |

| LBB |

Left Bundle Branch Block |

References

- Vicent, L.; Álvarez-García, J.; Vazquez-Garcia, R.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Rivera, M.; Segovia, J.; Pascual-Figal, D.; Bover, R.; Worner, F.; Fernández-Avilés, F.; et al. Coronary Artery Disease and Prognosis of Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, D.J.; Emerek, K.; Kisslo, J.; Søgaard, P.; Atwater, B.D. Left bundle-branch block is associated with asimilar dyssynchronous phenotype in heart failure patients with normal and reduced ejection fractions. Am. Hear. J. 2020, 231, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujol-López, M.; Tolosana, J.M.; Upadhyay, G.A.; Mont, L.; Tung, R. Left Bundle Branch Block. Cardiol. Clin. 2023, 41, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sami, A.; Iftekhar, M.F.; Khan, I.; Jan, R. Intraventricular Dyssynchrony among patients with left bundle branch block. Pak. J. Med Sci. 2018, 34, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leclercq, C.; Burri, H.; Delnoy, P.P.; A Rinaldi, C.; Sperzel, J.; Calò, L.; Concha, J.F.; Fusco, A.; Al Samadi, F.; Lee, K.; et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy non-responder to responder conversion rate in the MORE-CRT MPP trial. Eur. 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, Q.; Sun, H.; Qin, X.; Zheng, Q. Left Bundle Branch Pacing: Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siranart, N.; Chokesuwattanaskul, R.; Prasitlumkum, N.; Huntrakul, A.; Phanthong, T.; Sowalertrat, W.; Navaravong, L.; Cheungpasitporn, W.; Jongnarangsin, K. Reverse of left ventricular remodeling in heart failure patients with left bundle branch area pacing: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2023, 46, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJaroudi, W. Left ventricular mechanical dyssynchrony in patient with CAD: The Saga continues. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2020, 28, 3021–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacharova, L.; de Luna, B. The Primary Alteration of Ventricular Myocardium Conduction: The Significant Determinant of Left Bundle Branch Block Pattern. Cardiol. Res. Pr. 2022, 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillanmäki, S.; Lipponen, J.A.; Tarvainen, M.P.; Laitinen, T.; Hedman, M.; Hedman, A.; Kivelä, A.; Hämäläinen, H.; Laitinen, T. Relationships between electrical and mechanical dyssynchrony in patients with left bundle branch block and healthy controls. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2018, 26, 1228–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayama, Y.; Miyazaki, A.; Ohuchi, H.; Miike, H.; Negishi, J.; Sakaguchi, H.; Kurosaki, K.; Shimizu, S.; Kawada, T.; Sugimachi, M. Septal Flash-like Motion of the Earlier Activated Ventricular Wall Represents the Pathophysiology of Mechanical Dyssynchrony in Single-Ventricle Anatomy. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2020, 33, 612–621.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calle, S.; Calle, S.; Kamoen, V.; Kamoen, V.; De Buyzere, M.; De Buyzere, M.; De Pooter, J.; De Pooter, J.; Timmermans, F.; Timmermans, F. A Strain-Based Staging Classification of Left Bundle Branch Block-Induced Cardiac Remodeling. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 14, 1691–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sze, E.; Daubert, J.P. Left bundle branch block-induced left ventricular remodeling and its potential for reverse remodeling. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2018, 52, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degtiarova, G.; Claus, P.; Duchenne, J.; Schramm, G.; Nuyts, J.; Verberne, H.J.; Voigt, J.-U.; Gheysens, O. Impact of left bundle branch block on myocardial perfusion and metabolism: A positron emission tomography study. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2019, 28, 1730–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenyo, A.; Pietrasik, G.; Barsheshet, A.; Huang, D.T.; Polonsky, B.; McNITT, S.; Moss, A.J.; Zareba, W. QRS Fragmentation and the Risk of Sudden Cardiac Death in MADIT II. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2012, 23, 1343–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezi, B.; Akinrimisi, O.P. Permanent Bi-Bundle Pacing in a Patient With Heart Failure and Left Bundle Branch Block. JACC: Case Rep. 2022, 4, 101688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agricola, E.; Ancona, F. Is There Any Room Left for Echocardiographic-Dyssynchrony Parameters in the Field of CRT? JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 16, 885–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazoukis, G.; Thomopoulos, C.; Tse, G.; Tsioufis, K.; Nihoyannopoulos, P. Global longitudinal strain predicts responders after cardiac resynchronization therapy—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hear. Fail. Rev. 2021, 27, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgu, A.; Luca, C.-T.; Vacarescu, C.; Petrescu, L.; Goanta, E.-V.; Lazar, M.-A.; Arnăutu, D.-A.; Cozma, D. Considering Diastolic Dyssynchrony as a Predictor of Favorable Response in LV-Only Fusion Pacing Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandoli, G.E.; Cameli, M.; Pastore, M.C.; Benfari, G.; Malagoli, A.; D’andrea, A.; Sperlongano, S.; Bandera, F.; Esposito, R.; Santoro, C.; et al. Speckle tracking echocardiography in early disease stages: a therapy modifier? J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 24, e55–e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer-Perl, M.; Arnold, J.H.; Moshkovits, Y.; Havakuk, O.; Shmilovich, H.; Chausovsky, G.; Sivan, A.; Szekely, Y.; Arbel, Y.; Banai, S.; et al. Evaluating the role of left ventricle global longitudinal strain in myocardial perfusion defect assessment. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 38, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujol-López, M.; Jiménez-Arjona, R.; Garcia-Ribas, C.; Borràs, R.; Guasch, E.; Regany-Closa, M.; Graterol, F.R.; Niebla, M.; Carro, E.; Roca-Luque, I.; et al. Longitudinal comparison of dyssynchrony correction and ‘strain’ improvement by conduction system pacing: LEVEL-AT trial secondary findings. Eur. Hear. J. - Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024, 25, 1394–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragança, B.; Trêpa, M.; Santos, R.; Silveira, I.; Fontes-Oliveira, M.; Sousa, M.J.; Reis, H.; Torres, S.; Santos, M. Echocardiographic Assessment of Right Ventriculo-arterial Coupling: Clinical Correlates and Prognostic Impact in Heart Failure Patients Undergoing Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 28, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlot, B.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Palazzuoli, A.; Marino, P. Myocardial phenotypes and dysfunction in HFpEF and HFrEF assessed by echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance. Hear. Fail. Rev. 2019, 25, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ma, X.; Gao, Y.; Wu, S.; Xu, N.; Chen, F.; Song, Y.; Li, C.; Lu, M.; Dai, Y.; et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance–derived myocardial scar is associated with echocardiographic response and clinical prognosis of left bundle branch area pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur. 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriña-Vázquez, P.; Moraleda-Salas, M.T.; López-Masjuan-Ríos, Á.; Esteve-Ruiz, I.; Arce-León, Á.; Lluch-Requerey, C.; Rodríguez-Albarrán, A.; Venegas-Gamero, J.; Gómez-Menchero, A.E. Improvement in electrocardiographic parameters of repolarization related to sudden death in patients with ventricular dysfunction and left bundle branch block after cardiac resynchronization through His bundle pacing. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2023, 66, 2003–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma PS, Patel NR, Ravi V, et al. Clinical outcomes of left bundle branch area pacing compared to right ventricular pacing: Results from the Geisinger-Rush Conduction System Pacing Registry [published correction appears in Heart Rhythm. 2023 Jul;20(7):1100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2023.05.001]. Heart Rhythm. 2022;19(1):3-11. [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, J.; Chen, C.; Lin, J.; Wang, J.; Fu, F. A long-term clinical comparative study of left bundle branch pacing versus biventricular pacing in patients with heart failure and complete left bundle branch block. Hear. Vessel. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, I.F.; Collini, M.; Fonseca, R.; Guida, C.; Armaganijan, L.; Healey, J.S.; Carvalho, G. Conduction system pacing versus biventricular pacing in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hear. Rhythm. 2024, 21, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezi, B.; Akinrimisi, O.P. Permanent Bi-Bundle Pacing in a Patient With Heart Failure and Left Bundle Branch Block. JACC: Case Rep. 2022, 4, 101688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastrzębski, M.; Kiełbasa, G.; Cano, O.; Curila, K.; Heckman, L.; De Pooter, J.; Chovanec, M.; Rademakers, L.; Huybrechts, W.; Grieco, D.; et al. Left bundle branch area pacing outcomes: the multicentre European MELOS study. Eur. Hear. J. 2022, 43, 4161–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher-Hall, S.D. Pacemaker-induced cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Acad. Physician Assist. 2023, 36, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Q.-J.; Xu, H.; Zhou, X.-J.; Chang, Q.; Ji, L.; Chen, C.; Jiang, Z.-X. Effects of permanent left bundle branch area pacing on QRS duration and short-term cardiac function in pacing-indicated patients with left bundle branch block. Chin. Med J. 2021, 134, 1101–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayaraman, P.; Pokharel, P.; Subzposh, F.A.; Oren, J.W.; Storm, R.H.; Batul, S.A.; Beer, D.A.; Hughes, G.; Leri, G.; Manganiello, M.; et al. His-Purkinje Conduction System Pacing Optimized Trial of Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy vs Biventricular Pacing. JACC: Clin. Electrophysiol. 2023, 9, 2628–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madias, J.E. The impact of changing oedematous states on the QRS duration: implications for cardiac resynchronization therapy and implantable cardioverter/defibrillator implantation. Eur. 2005, 7, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Qi, J.; Liu, J. Left bundle branch pacing in heart failure patients with left bundle branch block: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2021, 45, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraman, P.; Sharma, P.S.; Cano, Ó.; Ponnusamy, S.S.; Herweg, B.; Zanon, F.; Jastrzebski, M.; Zou, J.; Chelu, M.G.; Vernooy, K.; et al. Comparison of Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing and Biventricular Pacing in Candidates for Resynchronization Therapy. Circ. 2023, 82, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auricchio, A.; Prinzen, F.W. Enhancing Response in the Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Patient. JACC: Clin. Electrophysiol. 2017, 3, 1203–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Arnold, A.D.; Miyazawa, A.A.; Keene, D.; Peters, N.S.; Kanagaratnam, P.; Qureshi, N.; Ng, F.S.; Linton, N.W.F.; Lefroy, D.C.; et al. Septal scar as a barrier to left bundle branch area pacing. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2023, 46, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, M.; Cameli, M.; Mandoli, G.E.; Pastore, M.C.; Righini, F.M.; D’ascenzi, F.; Focardi, M.; Rubboli, A.; Mondillo, S.; Henein, M.Y. Detection of myocardial fibrosis by speckle-tracking echocardiography: from prediction to clinical applications. Hear. Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 1857–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed I, Kayani WT. Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; , 2023. 30 July.

- Yang, Z.; Liang, J.; Chen, R.; Pang, N.; Zhang, N.; Guo, M.; Gao, J.; Wang, R. Clinical outcomes of left bundle branch area pacing: Prognosis and specific applications. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2023, 47, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, H.; Fan, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Tao, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Yao, Y. Tricuspid regurgitation outcomes in left bundle branch area pacing and comparison with right ventricular septal pacing. Hear. Rhythm. 2022, 19, 1202–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciapuoti, F.; Marfella, R.; Paolisso, G.; Cacciapuoti, F. Is the aging heart similar to the diabetic heart? Evaluation of LV function of the aging heart with Tissue Doppler Imaging. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2009, 21, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, J.; Althoff, T.; Busch, S.; Chun, K.J.; Dahme, T.; Ebert, M.; Estner, H.; Gunawardene, M.; Heeger, C.; Iden, L.; et al. „Left bundle branch (area) pacing“: Sondenpositionierung und Erfolgskriterien – Schritt für Schritt. Herzschrittmachertherapie + Elektrophysiologie 2024, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, L.; Xiao, G.; Huang, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Cai, B. Feasibility and stability of left bundle branch pacing in patients after prosthetic valve implantation. Clin. Cardiol. 2020, 43, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Han, R.; Cheng, L.; Li, R.; He, Y.; Xie, J.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y. Assessment of Cardiac Function and Ventricular Mechanical Synchronization in Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing by Speckle Tracking and Three-Dimensional Echocardiography. Am. J. Cardiol. 2022, 187, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Qin, C.; Du, A.; Wang, Q.; He, C.; Zou, F.; Li, X.; Tao, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, Z.; et al. Comparisons of long-term clinical outcomes with left bundle branch pacing, left ventricular septal pacing, and biventricular pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy. Hear. Rhythm. 2024, 21, 1342–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnusamy, S.S.; Arora, V.; Namboodiri, N.; Kumar, V.; Kapoor, A.; Vijayaraman, P. Left bundle branch pacing: A comprehensive review. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2020, 31, 2462–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Li, H.; Hu, Y.; Jin, H.; Weng, S.; He, P.; Huang, H.; Liu, X.; Gu, M.; Niu, H.; et al. Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing With or Without Conduction System Capture in Heart Failure Models. JACC: Clin. Electrophysiol. 2024, 10, 2234–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xu, J.; Wu, Y.; Qin, C.; Xue, S.; Hu, G.; Zou, J.; Shan, Q.; Zhou, X.; Hou, X.; et al. The association between paced left ventricular activation time and cardiac reverse remodeling in heart failure patients with left bundle branch block. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2024, 35, 1636–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peigh, G.; Steinberg, B.A. Mechanisms for structural remodeling with left bundle branch area pacing: more than meets the eye. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2023, 67, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, M.; Chen, Y.; Xu, H.; Wu, M. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: current understanding and future prospects. Hear. Fail. Rev. 2024, 30, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Xie, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, D.W.; Shan, C.; Zhou, X.; et al. Hyperactivation of ATF4/TGF-β1 signaling contributes to the progressive cardiac fibrosis in Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy caused by DSG2 Variant. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Gong, X.; Chen, H.; Qin, S.; Zhou, N.; Su, Y.; Ge, J. Effect of Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy on Myocardial Fibrosis and Relevant Cytokines in a Canine Model With Experimental Heart Failure. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2017, 28, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sequeira, V.; Theisen, J.; Ermer, K.J.; Oertel, M.; Xu, A.; Weissman, D.; Ecker, K.; Dudek, J.; Fassnacht, M.; Nickel, A.; et al. Semaglutide normalizes increased cardiomyocyte calcium transients in a rat model of high fat diet-induced obesity. ESC Hear. Fail. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchinoumi, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Suetomi, T.; Nawata, T.; Fujinaka, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Yano, M.; Sano, M. Structural Instability of Ryanodine Receptor 2 Causes Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Dysfunction as Well as Sarcoplasmic Reticulum (SR) Dysfunction. J. Cardiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassingthwaighte, J.B. Linking Cellular Energetics to Local Flow Regulation in the Heart. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2008, 1123, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.; Acharya, S.; Totade, M. Evolution of Pacemakers and Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators (ICDs) in Cardiology. Cureus 2023, 15, e46389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantsupawat, T.; Gumrai, P.; Apaijai, N.; Phrommintikul, A.; Prasertwitayakij, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C.; Chattipakorn, N.; Wongcharoen, W. Atrial pacing improves mitochondrial function in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2024, 327, H1146–H1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furquim, S.R.; Bocchi, E.A.; Lira, M.T.S.d.S.; Wanderley, M.R.d.B.; de Marchi, D.C.; Maciel, P.C.; Zimerman, A.; Ramires, F.J.A.; Nastari, L.; Biselli, B.; et al. Predictors of sustained reverse remodelling in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. ESC Hear. Fail. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraleda-Salas, M.T.; Amigo-Otero, E.; Esteve-Ruiz, I.; Arce-León, Á.; Carreño-Lineros, J.M.; Torralba, E.I.; Roldan, F.N.; Moriña-Vázquez, P. Early Improvement in Cardiac Function and Dyssynchrony After Physiological Upgrading in Pacing-Induced Cardiomyopathy. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladenvall, P.; Andersson, B.; Dellborg, M.; Hansson, P.-O.; Eriksson, H.; Thelle, D.; Eriksson, P. Genetic variation at the human connexin 43 locus but not at the connexin 40 locus is associated with left bundle branch block. Open Hear. 2015, 2, e000187–e000187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlochiver, S. Subthreshold Parameters of Cardiac Tissue in a Bi-Layer Computer Model of Heart Failure. Cardiovasc. Eng. 2010, 10, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).