Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

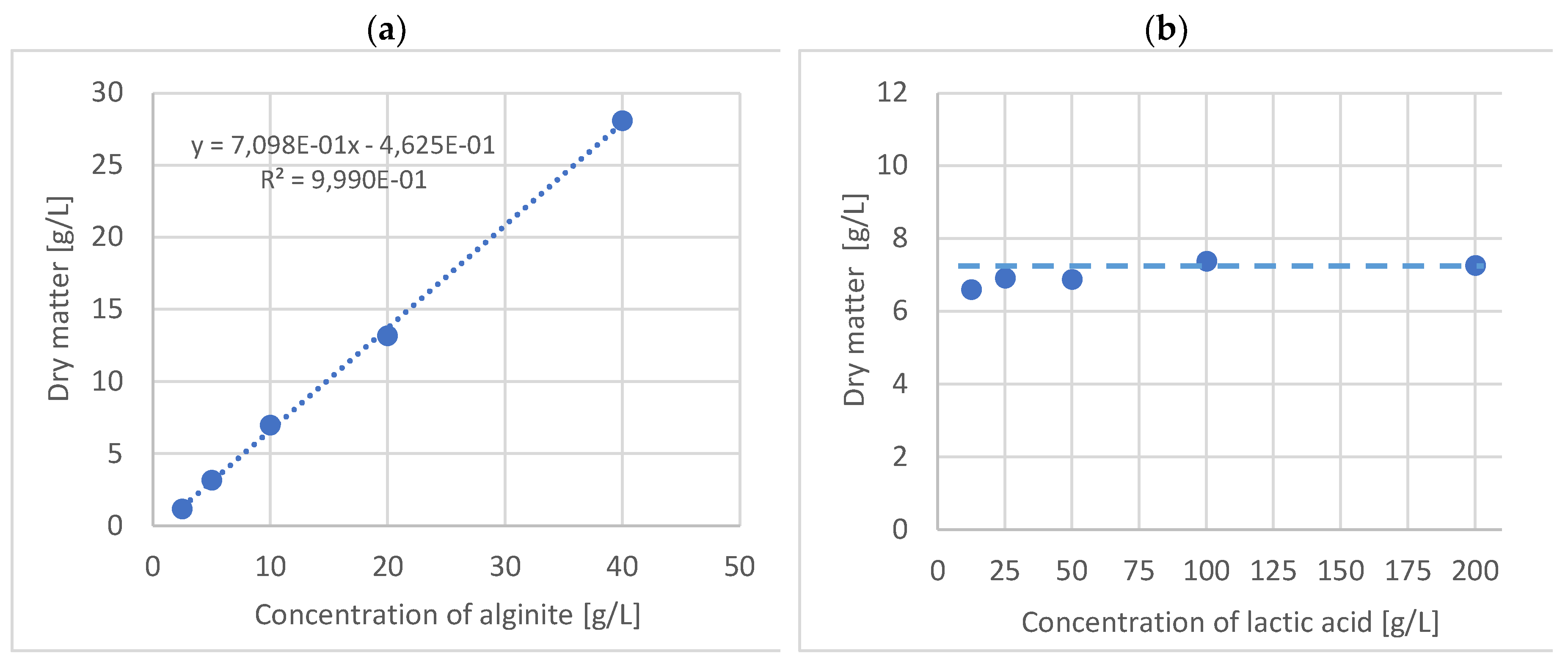

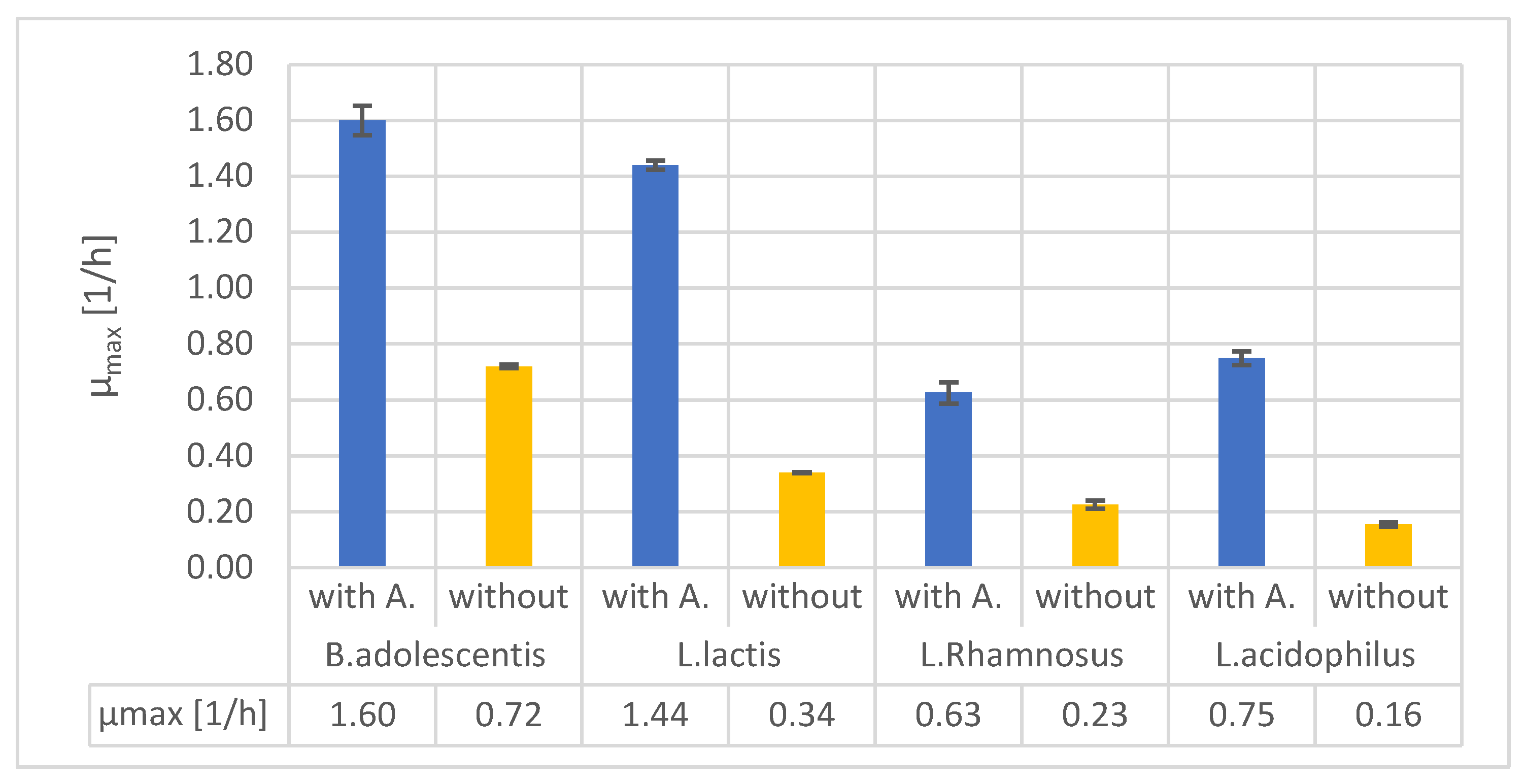

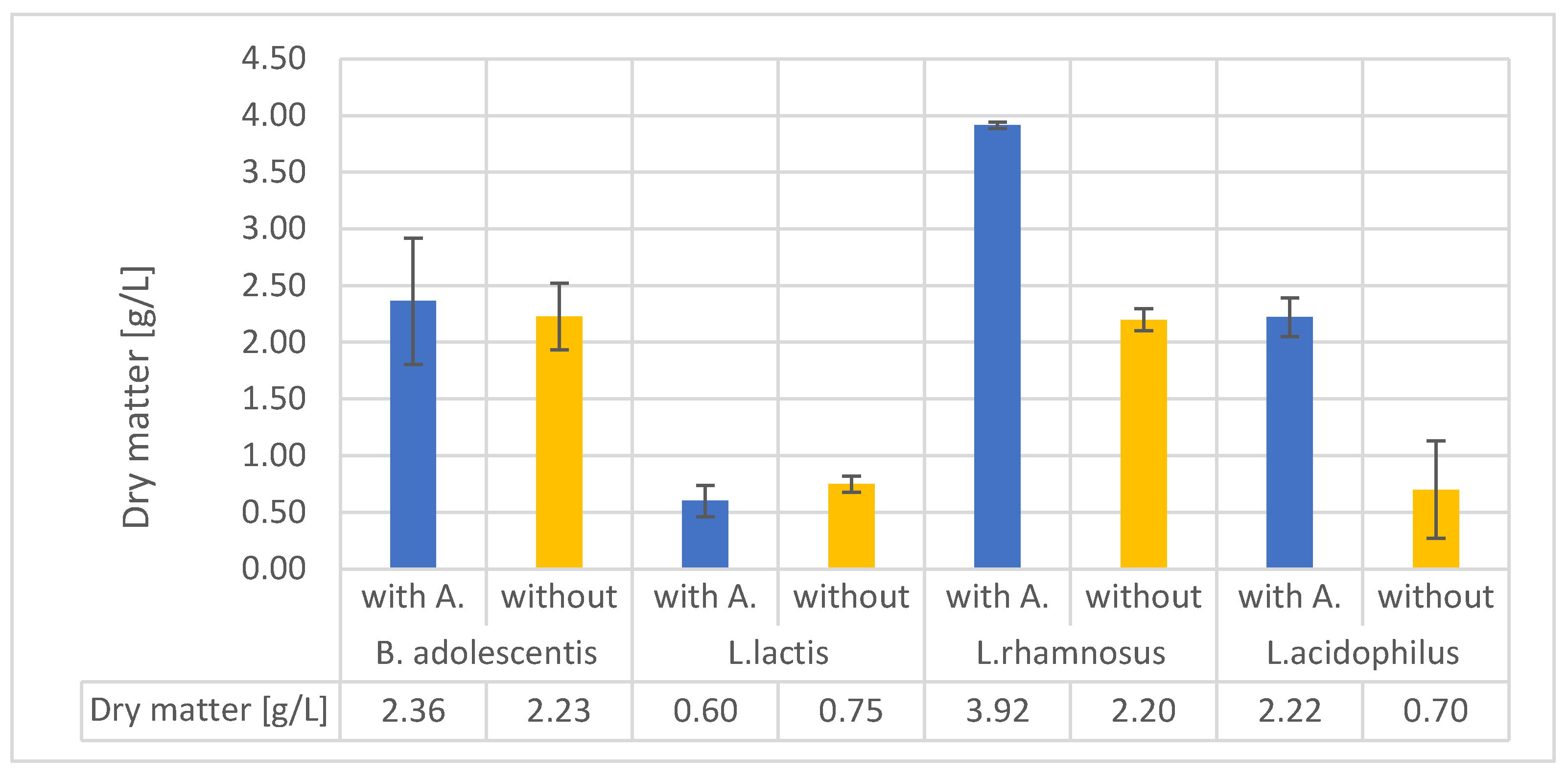

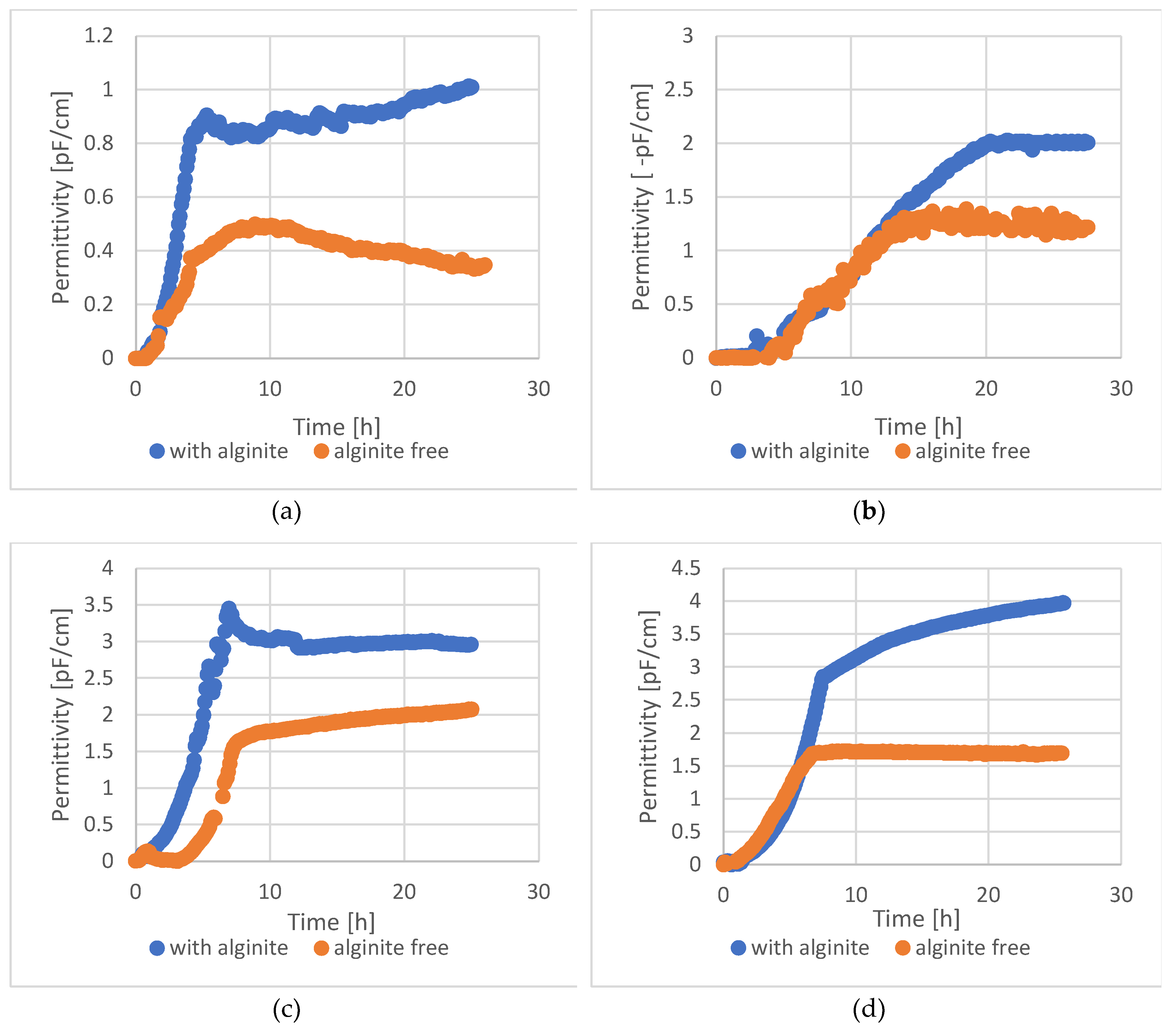

Studying the uses of different organic-mineral rocks is an expanding area of research. Although these materials have primarily been used in forestry and agriculture, other potential applications include cosmetics and nutrition. Alginite is a volcanic substance that resembles loam and is composed of clay minerals and extinct unicellular algae. Hungary's unique and environmentally friendly agricultural utilisation of alginite has sparked international interest and prompted further exploration of its potential applications. In recent years, studies have proved that alginite can be beneficial in agriculture and as a nutritional supplement, but only if it was further supplemented with lactic acid-producing bacteria (LAB). In contrary, our study investigates the application of alginite already during the LAB fermentation expecting higher probiotic cell number and enhanced positive probiotic effect. Our experiments, conducted using small-scale impedimetric high throughput equipment, revealed that alginite positively influenced the dry matter yield of all four tested probiotic species confirming the enhancing hypothesis. We also thoroughly investigated the fermentations in a lab-scale bioreactor to validate these results. The boosting potential of alginite was verified since depending on the applied strain 30–160% increase in probiotic biomass resulted.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Used Strains and Media

2.2. Fermentations

2.3. Analytic

3. Results

4. Discussion

Funding

Declarations

Data Availability

Ethics Approval

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- G. Solti, Az alginit. Budapest, A Magyar Áll Föld Int (alkalmi kiadványa). 1987, ISBN 963 671 073 2.

- Cukor, J.; Linhart, L.; Vacek, Z.; Baláš, M.; Linda, R. The effects of Alginite fertilization on selected tree species seedlings performance on afforested agricultural lands. For. J. 2017, 63, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tužinský, M.; Kupka, I.; Podrázský, V.; Prknová, H. Influence of the mineral rock alginite on survival rate and re-growth of selected tree species on agricultural land. J. For. Sci. 2015, 61, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hippmann, S.; Ahmed, S.S.; Fröhlich, P.; Bertau, M. Demulsification of water/crude oil emulsion using natural rock Alginite. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 553, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.S.; Hippmann, S.; Roode-Gutzmer, Q.I.; Fröhlich, P.; Bertau, M. Alginite rock as effective demulsifier to separate water from various crude oil emulsions. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 611, 125830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlubeňová, K.; Mudroňová, D.; Nemcová, R.; Gancarčíková, S.; Maďar, M.; Sciranková, Ľ. The Efect of Probiotic Lactobacilli and Alginite on the Cellular Immune Response in Salmonella Infected Mice. Folia Veter- 2017, 61, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strompfová, V.; Kubašová, I.; Farbáková, J.; Maďari, A.; Gancarčíková, S.; Mudroňová, D.; Lauková, A. Evaluation of Probiotic Lactobacillus fermentum CCM 7421 Administration with Alginite in Dogs. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2017, 10, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancarčíková, S.; Nemcová, R.; Popper, M.; Hrčková, G.; Sciranková, Ľ.; Maďar, M.; Mudroňová, D.; Vilček, Š.; Žitňan, R. The Influence of Feed-Supplementation with Probiotic Strain Lactobacillus reuteri CCM 8617 and Alginite on Intestinal Microenvironment of SPF Mice Infected with Salmonella Typhimurium CCM 7205. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2018, 11, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.P.; Kaur, M.; Myles, I.A. Does “all disease begin in the gut”? The gut-organ cross talk in the microbiome. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Lal, M.K.; Dutt, S.; Raigond, P.; Changan, S.S.; Tiwari, R.K.; Chourasia, K.N.; Mangal, V.; Singh, B. Functional Fermented Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics from Non-Dairy Products: A Perspective from Nutraceutical. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, e2101059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natt, S.K.; Katyal, P. Current Trends in Non-Dairy Probiotics and Their Acceptance among Consumers: A Review. Agric. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmizigul, A.; Sengun, I.Y. Traditional Non-Dairy Fermented Products: A Candidate for Probiotics. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 40, 1217–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silanikove, N.; Leitner, G.; Merin, U. The Interrelationships between Lactose Intolerance and the Modern Dairy Industry: Global Perspectives in Evolutional and Historical Backgrounds. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7312–7331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panghal, A.; Janghu, S.; Virkar, K.; Gat, Y.; Kumar, V.; Chhikara, N. Potential non-dairy probiotic products – A healthy approach. Food Biosci. 2018, 21, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Lara-Villoslada, F.; Ruiz, M.; Morales, M. Effect of unmodified starch on viability of alginate-encapsulated Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716. LWT 2013, 53, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, P.; Petrov, K. Lactic Acid Fermentation of Cereals and Pseudocereals: Ancient Nutritional Biotechnologies with Modern Applications. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasta, E.L.; Ronning, E.d.S.P.; Dekker, R.F.H.; da Cunha, M.A.A. Encapsulation and dispersion of Lactobacillus acidophilus in a chocolate coating as a strategy for maintaining cell viability in cereal bars. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Bai, X.; Zhang, J.; Kwok, L.-Y.; Shen, L.; Jin, H.; Sun, T.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, H. Gut Bifidobacterium responses to probiotic Lactobacillus casei Zhang administration vary between subjects from different geographic regions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 2665–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, P.; Németh, Á. Investigations into the Usage of the Mineral Alginite Fermented with Lactobacillus Paracasei for Cosmetic Purposes. Hung. J. Ind. Chem. 2022, 50, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B.; Seals, S.; Aban, I. Survival analysis and regression models. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2014, 21, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, P.; Németh, Á. Investigation and Characterisation of New Eco-Friendly Cosmetic Ingredients Based on Probiotic Bacteria Ferment Filtrates in Combination with Alginite Mineral. Processes 2022, 10, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barančíková, G.; Litavec, T. Comparison of Chemical Structure of Alginite Humic Acids Isolated with Two Different Procedures with Soil Humic Acids. 2016, 62, 138–148.

- Pospíšilová, L.; Komínková, M.; Zítka, O.; Kizek, R.; Barančíková, G.; Litavec, T.; Lošák, T.; Hlušek, J.; Martensson, A.; Liptaj, T. Fate of humic acids isolated from natural humic substances. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B — Soil Plant Sci. 2015, 65, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Donderski, A. Burkowska, Metabolic Activity of Heterotrophic Bacteria in the Presence of Humic Substances and Their Fractions. Pol J Environ Stud, 2000,9(4), pp.267-271. ISSN: 1230-1485.

- Visser, S. Effect of humic acids on numbers and activities of micro-organisms within physiological groups. Org. Geochem. 1985, 8, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travnik, L.J., Sieburth J., Effect of flocculated humic matter on free and attached pelagic microorganisms. Lim nol. Oceanogr, 1989, 34 (4), pp 688. [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.A.; Hodson, R.E. Bacterial production on humic and nonhumic components of dissolved organic carbon. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1990, 35, 1744–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donderski, W., Wodkowska A., Humic substances as a source of carbon and nitrogen for heterotrophic bacteria isolated from lakes of different trophy. Pol. J. Environ. Stud., 1997, 6 (4), pp 9.

- Benz, M.; Schink, B.; Brune, A. Humic Acid Reduction by Propionibacterium freudenreichii and Other Fermenting Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 4507–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A., Sah R., Sharir S., Zulkipli N., Mohamad A., Farinordin F. et al.. Untitled. Pertanika Journal of Tropical Agricultural Science 2022;45(3). [CrossRef]

- Gerke, J. Concepts and Misconceptions of Humic Substances as the Stable Part of Soil Organic Matter: A Review. Agronomy 2018, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikova, N.A.; Perminova, I.V. Interactions between Humic Substances and Microorganisms and Their Implications for Nature-like Bioremediation Technologies. Molecules 2021, 26, 2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudák, M.; Semjon, B.; Marcinčáková, D.; Bujňák, L.; Naď, P.; Koréneková, B.; Nagy, J.; Bartkovský, M.; Marcinčák, S. Effect of Broilers Chicken Diet Supplementation with Natural and Acidified Humic Substances on Quality of Produced Breast Meat. Animals 2021, 11, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J.D.; Cole, K.A.; Chakraborty, R.; O’Connor, S.M.; Achenbach, L.A.; Ka, C.; Sm, O. Diversity and Ubiquity of Bacteria Capable of Utilizing Humic Substances as Electron Donors for Anaerobic Respiration. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 2445–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, S.A.; Ramos, A.F.O.; Holman, D.B.; McAllister, T.A.; Breves, G.; Chaves, A.V. Humic Substances Alter Ammonia Production and the Microbial Populations Within a RUSITEC Fed a Mixed Hay – Concentrate Diet. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, P.; O Ribeiro, G.; Wang, Y.; A McAllister, T. Humic substances reduce ruminal methane production and increase the efficiency of microbial protein synthesisin vitro. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 99, 2152–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, D.; Nigam, P.S. Therapeutic and Dietary Support for Gastrointestinal Tract Using Kefir as a Nutraceutical Beverage: Dairy-Milk-Based or Plant-Sourced Kefir Probiotic Products for Vegan and Lactose-Intolerant Populations. Fermentation 2023, 9, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

glucose (at L.lactis lactose),

glucose (at L.lactis lactose),  lactic acid,

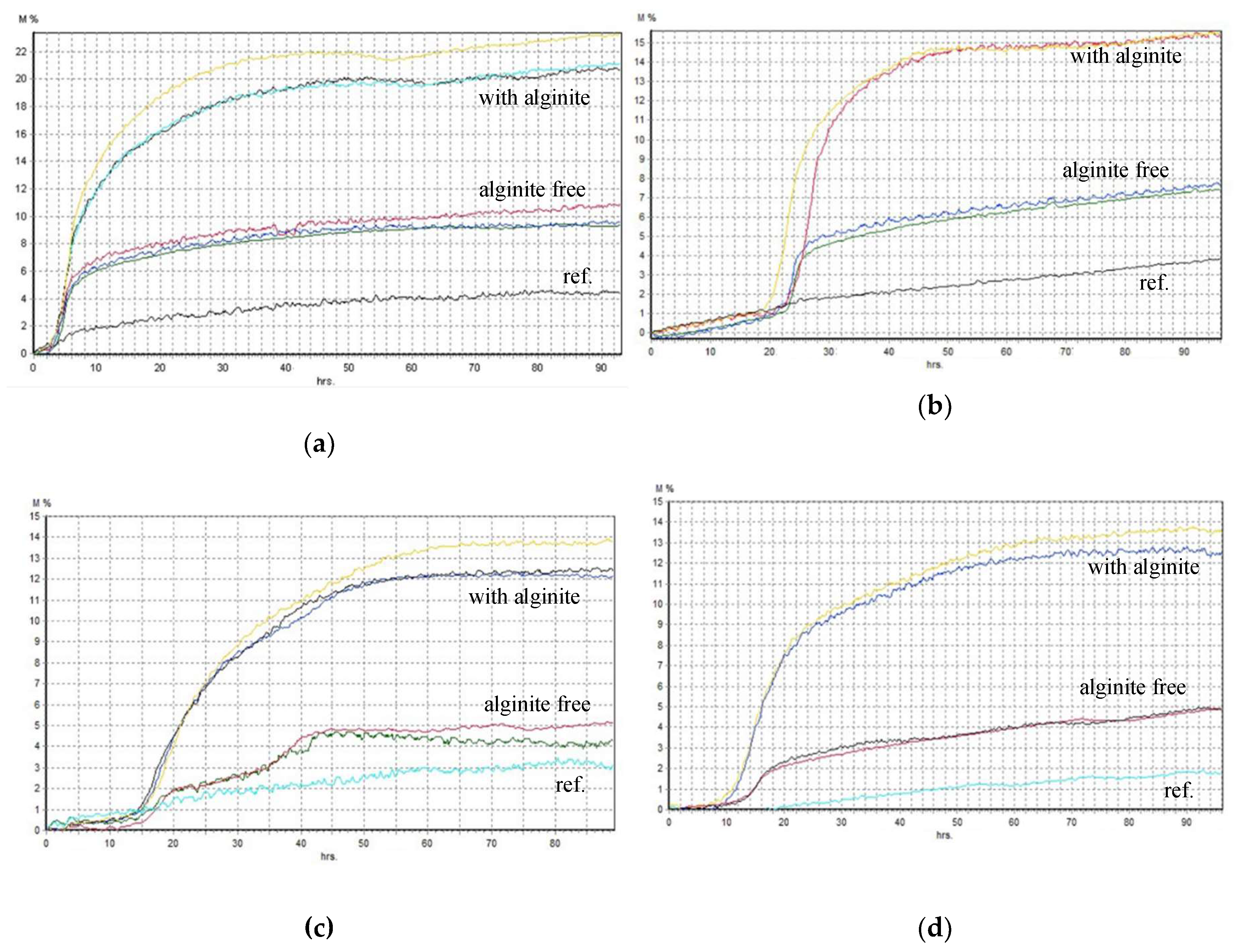

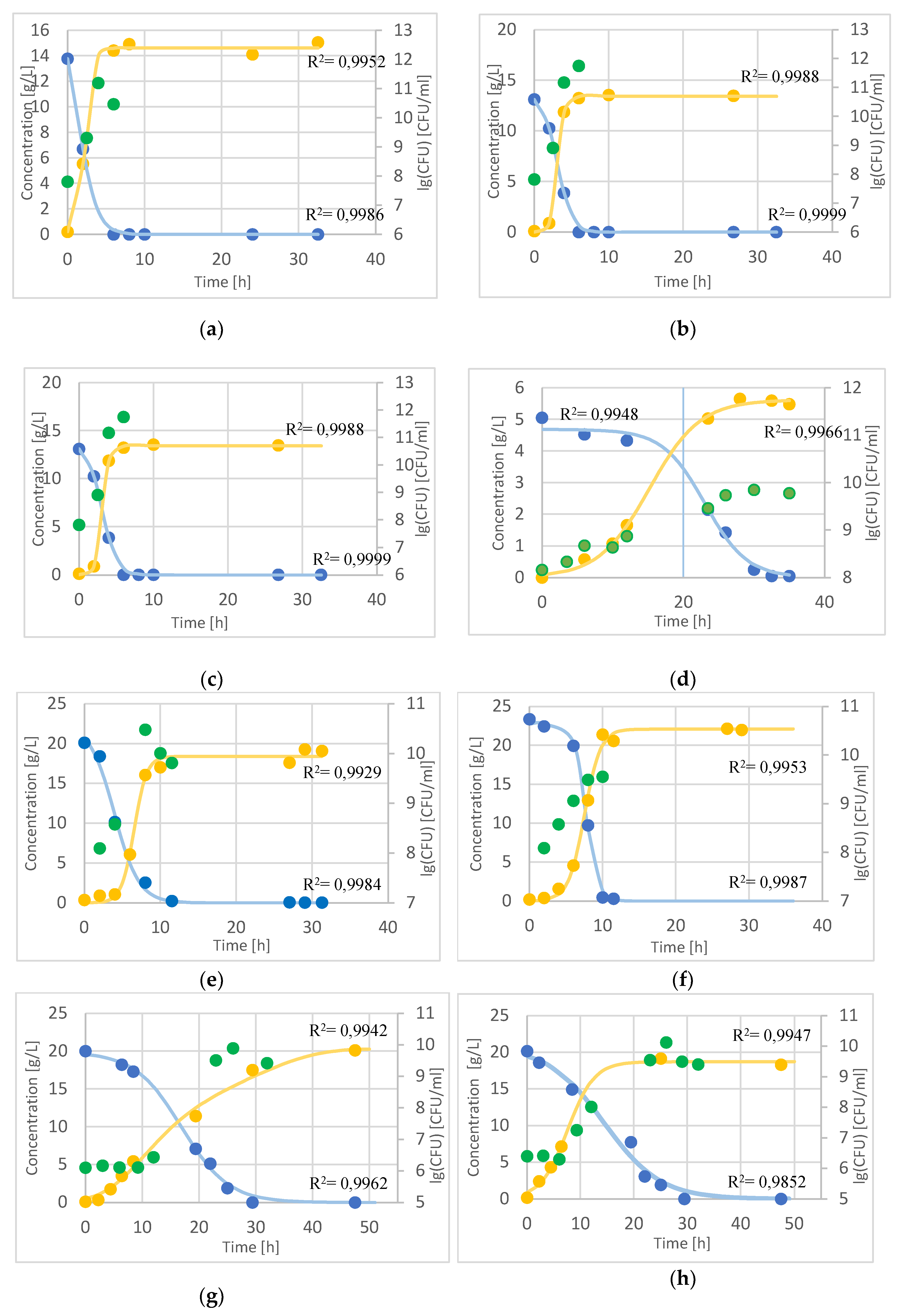

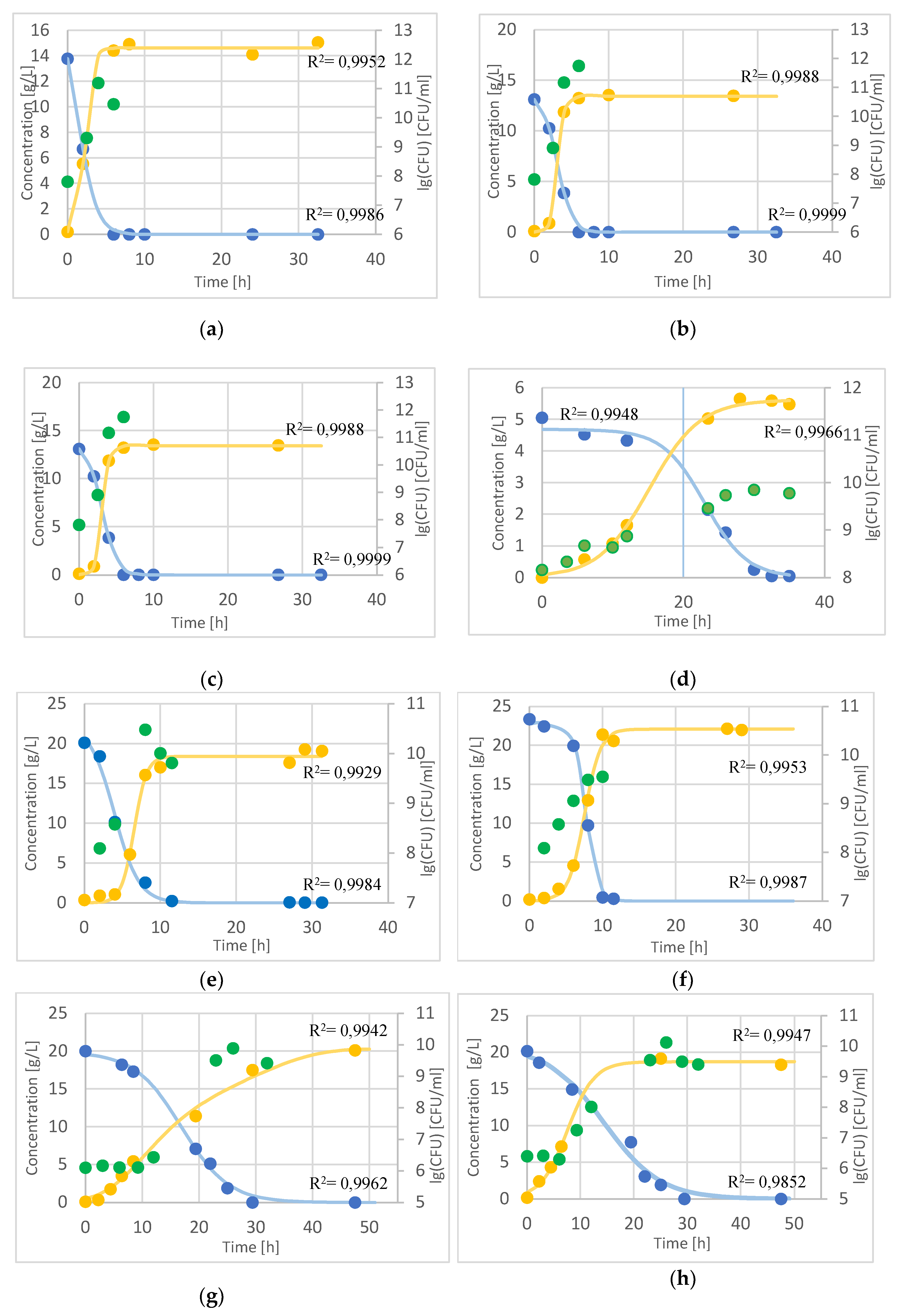

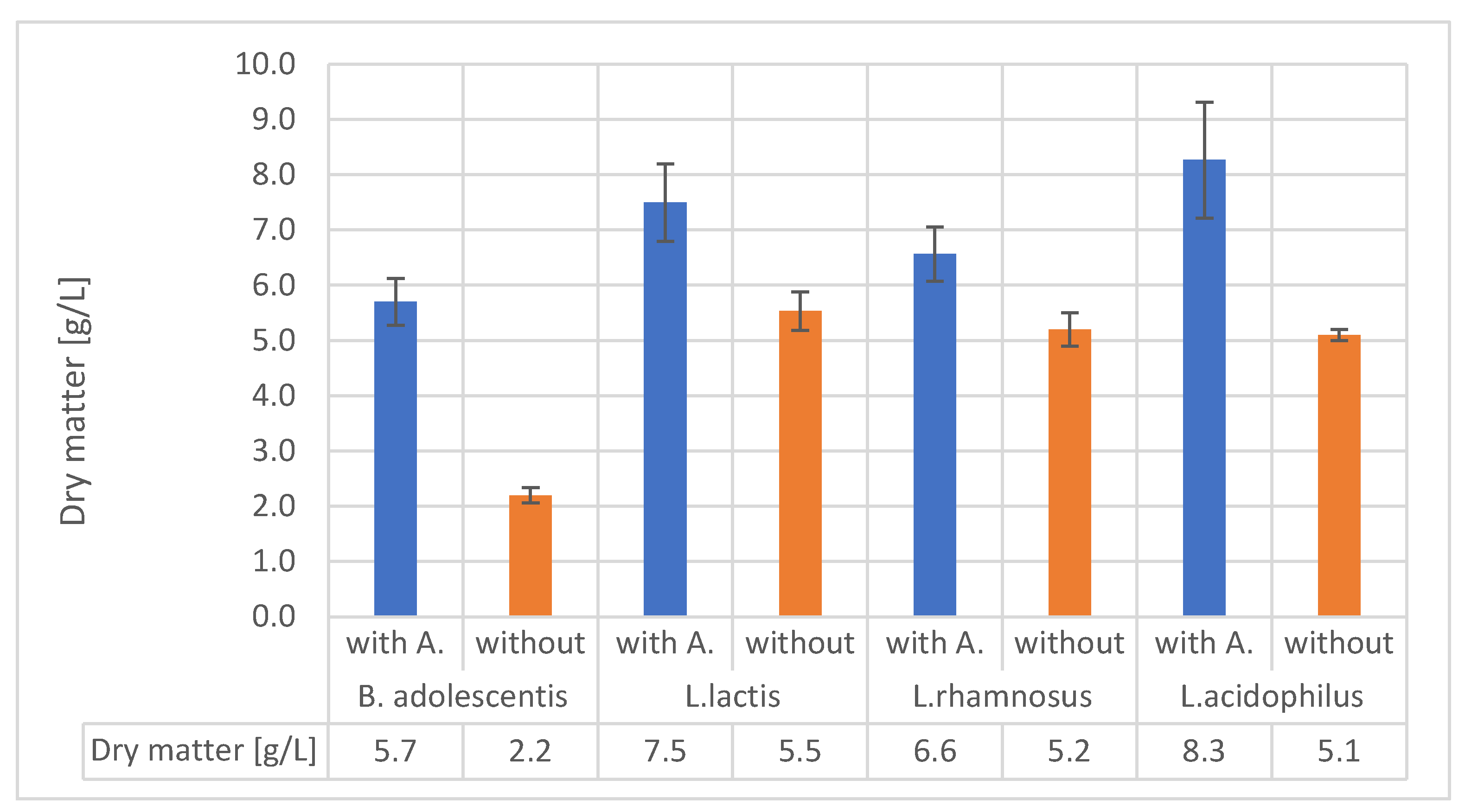

lactic acid,  CFU (B. adolescentis a. (with alginite), b.; L. lactis c. (with alginite), d.; L. rhamnosus e. (with alginite), f.; L. acidophilus g. (with alginite), h.).

CFU (B. adolescentis a. (with alginite), b.; L. lactis c. (with alginite), d.; L. rhamnosus e. (with alginite), f.; L. acidophilus g. (with alginite), h.).

glucose (at L.lactis lactose),

glucose (at L.lactis lactose),  lactic acid,

lactic acid,  CFU (B. adolescentis a. (with alginite), b.; L. lactis c. (with alginite), d.; L. rhamnosus e. (with alginite), f.; L. acidophilus g. (with alginite), h.).

CFU (B. adolescentis a. (with alginite), b.; L. lactis c. (with alginite), d.; L. rhamnosus e. (with alginite), f.; L. acidophilus g. (with alginite), h.).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).