1. Introduction

Central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) is a major concern associated with central venous catheters (CVCs). Compared to CVCs, peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) have a lower infection rate and are easier to manage, making them indispensable in modern healthcare for oncology and other long-term venous infusion patients.[

1,

2] PICCs are widely used for prolonged intravenous therapies, such as chemotherapy or antibiotic therapy. Various types of PICCs are available, and understanding their cost-effectiveness is crucial for informed healthcare decisions. Two distinct types have garnered attention for their potential to reduce catheter-related complications: Antimicrobial-coated PICCs and standard PICCs.

The advent of antimicrobial-coating represents a significant advancement in CLABSI prevention.[

3,

4] A randomized controlled trial comparing antimicrobial-impregnated CVC versus standard CVC showed that CLABSI risk reduction (RR) with chlorhexidine/silver sulfadiazine-coated CVC was 0.73 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.57–0.94).[

5] However, few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have focused on PICCs. One RCT compared miconazole- and rifampicin-impregnated PICCs with standard PICC found no significant difference in clinical outcomes. Another RCT comparing antimicrobial-coated PICCs with standard PICCs reported no significant difference in reducing CLABSI risk (P=0.61) or reducing VTE events (P>0.99) [

6,

7].

Few studies have examined the economic sustainability of different types of PICCs. The distinctive costs associated with nursing care and complication management make assessing the economic impact of PICC use in long-term intravenous therapy particularly challenging. To address this gap, we conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) utilizing secondary data to evaluate a novel catheter design and its associated complications. In China, community hospitals generally incur lower charge expenses compared to Class 3 hospitals, due largely to government policies aimed at encouraging the utilization of community healthcare resources for routine medical needs. Studies on China's healthcare system reforms suggest that expanding primary and community care capacities effectively addresses the imbalance between escalating healthcare demands and limited resources at tertiary hospitals [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Incorporating these societal insights, this study evaluates the economic implications of antimicrobial-coated PICCs relative to standard PICCs, specifically comparing hospital-based care with community-based catheter management. Data were collected from the hematology departments at Peking University People's Hospital from October 2020 to June 2023.

2. Materials and Methods

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

In this section, where applicable, authors are required to disclose details of how generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has been used in this paper (e.g., to generate text, data, or graphics, or to assist in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation). The use of GenAI for superficial text editing (e.g., grammar, spelling, punctuation, and formatting) does not need to be declared.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Population

The Cost-effectiveness Analysis (CEA) was based on data from Peking University People's Hospital, a Class 3A hospital in China. The patients enrolled in the analysis all underwent PICC procedures in the hematology departments from September 2020 to May 2023. As of May 31, 2023, Peking University People’s Hospital had a total of 430 beds, and during this period, 6,923 PICC units were inserted.

The economic evaluation was based on data from adult hematology patients who required either a bone marrow transplant or chemotherapy from October 2020 to June 2023.

2.2. Evaluation Points

The intravenous access procedures adhered to the CLABSI prevention program, which included the CDC’s recommended bundle strategies: maximum sterilized barrier, antibacterial-based antiseptic skin preparation, hand hygiene, and related training.[

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] The PICC insertion nurses were accredited and certified by the Chinese Nurse Society and had performed at least 50 procedures per year to maintain consistent, high-quality insertion techniques. The observation period was 90 days, with the regular follow-up to maintain catheter function. The standard follow-up procedures included insertion point care, ultrasonographic assessment of CVC-related thrombosis, and catheter function checks. The main evaluation points of PICCs ware catheter-related complications, which included the puncture success rate, the catheter-related bloodstream infections, the thrombosis and other catheter related local complications. The CLABSI was determined according to the laboratory-confirmed bloodstream infection criteria during the PICC indwelling time, excluding mucosal barrier injury laboratory-confirmed bloodstream infection (MBI-LCBI).[

16,

17,

18] The fever of unknown origin among patients was recorded according to patient-reported symptoms and clinical assessments that did not meet the CLABSI criteria. Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were not gathered, as referred to in other reported articles, and the direct costs related to PICC insertion and maintenance were obtained from the medical record [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

2.4. Cost Evaluation Measures

The public hospital perspective of the analysis reflects the costs in Chinese public hospitals covered by the Urban and Rural Residents Basic Medical Insurance (URRBMI). We calculated the following in both medical center and community hospital settings: the price of the standard PICC, estimated price of the antimicrobial-coated PICC (¥/piece) (This PICC did not launch in China market in 2020), average costs of insertion and maintenance once for one patient (¥/time), average costs for CLABSI diagnosis and treatment for one patient (¥/time), and average duration of hospitalization per therapy stage (days). Regarding the observation purpose, we did not include costs for the original disease or other costs unrelated to the catheter.

2.5. Currency Rate and Conversion

The costs were calculated according to real values reported from 2019 to 2023. All costs are presented in RMB. The average official currency conversion rate of the China Central Bank from 2020 Jan to 2023 Dec was 1 RMB (¥) equal to 0.1475 US dollars ($).

2.6. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

To assess the cost-effectiveness of two types of PICCs in China’s medical center and community hospital care settings, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated. The costs considered in the analysis were evaluated from a societal perspective.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

We processed the data using Stata/SE 15.1 and TreeAge Pro Healthcare (version 2023 R1.2), a software package tailored for health outcome research, provided by TreeAge Software, Inc. Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. Data for expenditure calculations of complication treatments were collected using the micro-costing method alongside standard patient care throughout the study.[

24,

25,

26] The mean daily care expenditure for each scenario was used to estimate the average cost of each procedure associated with central vascular access [

27].

3. Results

In our analysis, a total of 224 patients (136 male and 88 female) with hematologic diseases, aged 18–83 years (mean age, 42.34±13.70), required PICC catheters. The mean indwelling time of the antimicrobial-coated PICCs was ¥62.81 days (±27.98), while the standard PICCs had an indwelling time of 69.04 days (±26.65) (P=0.089). The baseline characteristics of all patients included in the study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical Variables of Patients in the Two PICC Groups.

A total of 113 patients received antimicrobial-coated PICCs, whereas 111 received standard PICCs. We analyzed 220 patients with CLABSI, fever of unknown origin, and local complications. Eight patients met the criteria for BSI: Three of them met the criteria for CLABSI, and the other five were diagnosed with MBI-LCBI. 36 patients developed CLABSI-related symptoms, but based on laboratory examination results, they did not meet all the CLABSI criteria, and other infection sources were excluded. Three patients developed CLABSI in the standard PICCs cohort; however, the difference was not significant between two groups (P=0.076). 17 patients (15.18%) in the antimicrobial-coated PICCs and 20 patients in the standard PICCs (N=20, 19.05%, P=0.449) developed fever of unknown origin (

Table 2). The unplanned withdrawal of the catheter in the antimicrobial-coated PICCs cohort was 31 (30.39%), and the standard PICCs cohort was 26 (25.24%, P=0.411). The local complications and the unplanned catheter withdrawal of complications lead to more medical treatment for inserting the catheter again and local therapy to release the symptoms, which were calculated into the cost model.

3.1. Cost Analysis

The Beijing Municipal Price Bureau for Class 3A hospitals provided the prices of the standard PICC, nursing expenses per patient, and laboratory test fees. For comparison, the price of a standard PICC was ¥2100 in 2020. To complete the decision tree model, the estimated price of the antimicrobial-coated PICC was set to ¥2300, and there was no price label for this new device in 2020.

China’s Basic Medical Insurance covers regular care and PICC insertion costs for Urban and Rural Residents. However, most community hospitals in central Beijing do not have certified nurses for PICC insertion. The additional care costs were related to catheter-related complications, which varied by catheter type, as assumed in the study. The direct costs of PICC are listed in

Table 3, calculated based on the average per-care costs, including costs per insertion and maintenance in 2020. Diagnosing CLABSI required at least two central catheter blood cultures per lumen and two peripheral blood cultures according to hospital protocol. The average cost for diagnosing CLABSI was ¥1,332.77 per event, while the average treatment cost per patient for each CLABSI event was ¥87,147.08, which included parenteral antibiotics, catheter removal, and other empirical therapies. CLABSI is the most feared complication, with an attributed mortality rate of 2.27–2.75%, as reported in another article. The expenses charged by community hospitals are lower than those of Class 3 hospitals; the estimated costs for the follow-up period of catheter maintenance in community hospitals were based on the charge expense list.

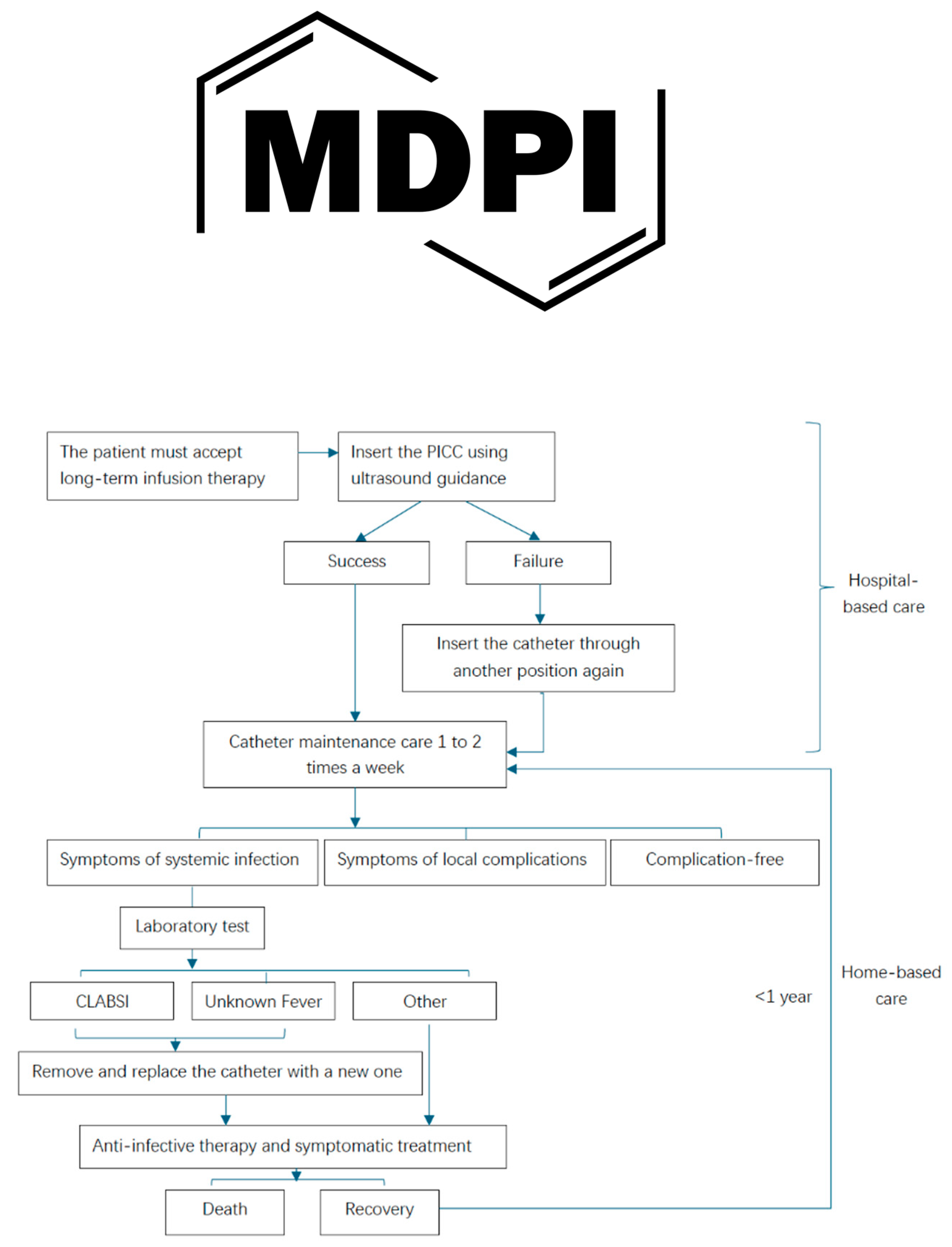

3.3. Decision Tree Model

The decision tree for economic analysis illustrates the trajectory of the two types of PICCs and the two different healthcare settings from placement until the end of infusion therapy, highlighting the probability of failure due to catheter-related complications.

Figure 1 presents the decision tree model for a patient who agrees to catheter insertion and maintains the catheter’s function throughout the therapy period, detailing the potential complications associated with standard PICCs and antimicrobial-coated PICCs in various healthcare settings. The rollout of the decision tree indicates that the antimicrobial-coated PICC is a more advanced device for managing expenses related to catheter-related complications in community hospital settings, with a total expense of ¥ 61,235.43 for 90 days of antimicrobial-coated PICC in a community hospital setting.

3.4. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) measures the cost-per-unit effect.[

28,

29,

30,

31] As the costs of standard PICCs were lower than those of antimicrobial-coated PICCs, we evaluated the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). ICER=C1-C2/E1-E2 was defined as the ratio of the difference in the costs of the two types of PICCs and the difference in clinical settings, where C1 and C2 denote the costs of the entire processes for the catheter-related indwelling period, respectively, and E1 and E2 denote the clinical effectiveness.

The PICC served as a tool channel and did not enhance the treatment outcome. However, the complications associated with PICC impacted the clinical results, allowing us to differentiate the costs of all catheter-related complications and treatments. The outcome was determined by calculating the difference in the rates of puncture unsuccess, CLABSI, unknown fever, and other local catheter-related complications.

ICER=C standard PICCs - C antimicrobial-coated PICCs/E standard PICCs -E antimicrobial-coated PICCs

The results were then interpreted as the cost per patient with a catheter per QALY for a complication incidence. In general, a lower ICER can lead to a higher value.

3.4.1. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis in Class 3A Hospital Setting

The average cost of the antimicrobial-coated PICC in a Class 3 hospital was ¥62,817.79, while the average price of the standard PICC was ¥102,861.57. According to the calculated ICER, compared to the standard PICC, the antimicrobial-coated PICC resulted in an average cost saving of ¥4,004,378.00 per QALY in a Class 3A hospital setting (Table 4). If these patients during the disease remission period could move to a community hospital for catheter maintenance care, the cost would be lower than in Class 3A hospitals. The average patient cost would be around ¥61,235.43 for the antimicrobial-coated PICC, and the standard PICC would be ¥100,561.69; the saving of per QALYs would be ¥3,932,626.00.

The difference between the two different catheters was caused by the complicated rates, especially of the infection and the suspected infection cases. From the breakdown of expense levels, the diagnosis and treatment of the CLABSI and unknown fever contributed to >80% of the expense of catheter maintenance. Fever of unknown would require empiric therapies, although it could not be diagnosed as CLABSI; however, the related diagnosis and treatment costs were almost the same among unknown fever and diagnosed CLABSI. Sometimes, unknown fever origin might lead to higher costs than diagnosed CLABSI because of the repeated lab examinations to identify the infection source. In the standard group, the costs of fever of unknown origin were ¥444,819.29, and CLABSI was ¥444,404.50; in the antimicrobial-coated PICC group, the cost of unknown fever was ¥314,742.50 and that of CLABSI was ¥314,204.50. Thus, antimicrobial-coated PICC appears to be a more cost-effective alternative to acute- and community-care solutions for oncology patients.

3.4.2. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis in Community Hospital Setting

The community hospital setting showed substantial cost savings compared to the Class 3A hospital setting (

Figure 2), despite no observable difference in clinical effectiveness. Specifically, the incremental cost in the community hospital is approximately ¥1600 lower. This significant reduction highlights the economic advantages of managing PICC-related care within community settings, suggesting potential efficiency gains and improved resource utilization when shifting appropriate healthcare services from higher-level hospitals to community-based care environments. The difference between the cost-effectiveness model of Class 3A hospitals and community hospital settings was centered on basic care for maintaining catheter function concerning indwelling times. The existing community hospital in Beijing could offer limited services, such as flushing and changing dressings. The ultrasound-based superficial vein test could not be performed; however, in comparison to the United States, an Infusion Nurse Society (INS) certified nurse could carry out this test for the PICC patient as part of standard procedures. If the community hospitals in Beijing could provide more catheter-related care for PICC patients, it could lead to greater cost savings.

4. Discuss

Despite significant improvements in PICC and CVC care over the past two decades, studies consistently highlight that effective procedures and innovative devices remain essential for reducing catheter-related bloodstream infections (CLABSI). Nevertheless, empirical treatments for unexplained catheter-associated fevers continue to pose clinical challenges [

32,

33]. Therefore, ongoing research efforts are necessary to explore and develop advanced catheter technologies and patient management protocols to enhance care quality and reduce associated healthcare costs.

Long-term indwelling catheters typically demonstrate a favorable profile with low complication rates, high patient comfort, and simplified care management, prioritizing both patient safety and durability. Although implanted ports are broadly utilized in Western countries, their adoption in China remains limited due to the high expenses associated with specialized non-reimbursable needles and the invasiveness of the implantation procedure itself. This study evaluates the cost-effectiveness of two type PICCs across various healthcare settings in China. From a societal perspective, identifying a solution that delivers lower complication rates, simplified management, and improved long-term outcomes across diverse clinical environments is critical, particularly given China’s healthcare resource allocation imbalances.

The antimicrobial-coated PICCs demonstrated a reduction in CLABSI compared with the standard PICCs; however, there was no significant difference observed in other clinical outcomes. When evaluating catheter-related complications requiring intervention in various healthcare settings, significant differences emerged in cost savings between antimicrobial-coated and standard PICCs in both Class 3A hospitals and community hospitals. The cost-effectiveness analysis, grounded in real-world data, highlights clinical outcome differences and underscores the challenges encountered in actual clinical practice.

4.1. Implications for Practice and Policy

As new technologies emerge, clinicians must balance long-term benefits against initial costs. Antimicrobial-coated PICCs showed better performance in terms of complication control and safety. Policymakers should consider incorporating cost-effective PICCs into standard healthcare practices and coverage policies to enhance patient satisfaction and optimize resource utilization. Additionally, greater emphasis should be placed on community healthcare settings by enhancing training programs for healthcare providers and expanding services for long-term care patients. Such improvements could effectively address healthcare resource allocation imbalances and enhance care accessibility at the community level.

4.2. Future Research Directions

Given the extensive use of PICC catheters, future research should include multicenter studies to validate findings across different healthcare environments. Specific future research priorities include:

Development of clear, innovative health economic evaluation frameworks specifically tailored to supportive medical devices.

Evaluation methodologies that account for varying healthcare settings, providing broader analytical scopes to assess the value of novel catheter technologies.

Investigation of clinical scenarios where statistically non-significant outcomes might still represent substantial economic value in real-world clinical practice.

Although antimicrobial-coated PICCs were evident in the cost-effectiveness analysis, these findings indicate that they are economically justified for high-risk patient groups from a societal perspective. Our findings underscore the need for policymakers to refine evaluation methodologies for novel medical devices, including considerations of reduced complication rates. Reduced complication rates lead to significant reductions in healthcare costs and improved overall quality of care in various healthcare settings.

5. Limitation of the Study

This study possesses several strengths, including extensive data collection, application of a rigorous decision-analytical model, and validation via a Delphi panel. However, certain limitations must be acknowledged:

Use of QALYs: The quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) applied in this study were derived from previous hematology-related research measuring general treatment impacts on patient quality of life. This approach did not specifically isolate catheter-associated quality-of-life variations unless associated with severe complications, such as mortality due to infection. Future research should include direct collection of catheter-specific quality-of-life data to evaluate catheter impacts more accurately.

Economic evaluation methods: Traditional economic evaluation methodologies may not fully capture the value of interventions primarily to enhance patient quality of life without significantly altering disease progression. Innovative economic evaluation theories and analytical tools are necessary to assess the true economic value of supportive medical technologies adequately.

PICC catheterization is an invasive procedure; the PICC must be inserted easily and have a low complication rate. Risks such as CLABSI, unknown fever, and other local catheter-related complications can impact additional treatment during the catheter indwelling period.

The incremental cost-effectiveness plot illustrates the economic comparison between the community hospital and the Class 3A hospital setting in Beijing.

Antibacterial-coated PICCs were used in the study group and Standard PICCs were used in the control group.

Author Contributions

JX conceptualized and executed the study, designed the model, collected the necessary data, and conducted the analysis. RC, HZ, and HCC served as clinical and economic experts, respectively. XY provided the clinical data source. JX drafted the manuscript, and the final version received input, approval, and contributions from all team members. All authors have collectively agreed to investigate and resolve any such questions and document the resolutions in the literature.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript. The data supporting this study's findings are available from Perking University People’s Hospital and Beijing Dongcheng Community Hospital Bureau. Data from the authors with permission from Perking University People’s Hospital.

Acknowledgments

This article does not include any personnel who are not authors that contributed to it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CLABSI |

Central line-associated bloodstream infection |

| QALYs |

Quality-adjusted life years |

| ICER |

Three letter acronym |

| CEA |

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis |

| PICC |

Peripherally inserted central catheter |

References

- M. G. Caris et al. a: “Indwelling time of peripherally inserted central catheters and incidence of bloodstream infections in haematology patients: a cohort study, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, Y. H. Zhang, Y. Li, N. Zhu, Y. Li, J. Fu, and J. Liu, “Comparison of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) versus totally implantable venous-access ports in pediatric oncology patients, a single center study,” Sci Rep, vol. 12, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Novikov, M. Y. A. Novikov, M. Y. Lam, L. A. Mermel, A. L. Casey, T. S. Elliott, and P. Nightingale, “Impact of catheter antimicrobial coating on species-specific risk of catheter colonization: a meta-analysis,” Antimicrob Resist Infect Control, vol. 1, p. 40, Dec. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Y. Chong, N. M. H. Y. Chong, N. M. Lai, A. Apisarnthanarak, and N. Chaiyakunapruk, “Comparative Efficacy of Antimicrobial Central Venous Catheters in Reducing Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in Adults: Abridged Cochrane Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis,” Clin Infect Dis, vol. 64, no. suppl_2, pp. S131–S140. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Jaeger et al., “Reduction of catheter-related infections in neutropenic patients: a prospective controlled randomized trial using a chlorhexidine and silver sulfadiazine-impregnated central venous catheter,” Ann Hematol, vol. 84, no. 4, pp. 258–262, Apr. 2005. [CrossRef]

- R. Gilbert et al., “Antimicrobial-impregnated central venous catheters for prevention of neonatal bloodstream infection (PREVAIL): an open-label, parallel-group, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial,” Lancet Child Adolesc Health, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 381–390, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Storey et al., “A comparative evaluation of antimicrobial coated versus nonantimicrobial coated peripherally inserted central catheters on associated outcomes: A randomized controlled trial,” Am J Infect Control, vol. 44, no. 6, pp. 636–641, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- l: medical expenditure. [CrossRef]

- S. Yang, J. S. Yang, J. Lu, J. Zeng, L. Wang, and Y. Li, “Prevalence and Risk Factors of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Intensive Care Unit Nurses in China,” Workplace Health Saf, vol. 67, no. 6, pp. 275–287, Jun. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Chen et al., “Ten years of China’s new healthcare reform: a longitudinal study on changes in health resources,” BMC Public Health, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 1–13, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Public Health, “China’s health reform: 10 years on,” Lancet Public Health, vol. 4, no. 9, p. e431, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. I. Ardura et al., “Impact of a Best Practice Prevention Bundle on Central Line-associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI) Rates and Outcomes in Pediatric Hematology, Oncology, and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Patients in Inpatient and Ambulatory Settings,” J Pediatr Hematol Oncol, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. E64–E72, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Marschall et al., “Strategies to Prevent Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Update,” Hospital Epidemiology, vol. 35, no. 7, pp. 753–771. 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. Böll et al., “Central venous catheter–related infections in hematology and oncology: 2020 updated guidelines on diagnosis, management, and prevention by the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO),” Ann Hematol, vol. 100, no. 1, pp. 239–259, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. H. Lee, N. H. K. H. Lee, N. H. Cho, S. J. Jeong, M. N. Kim, S. H. Han, and Y. G. Song, “Effect of Central Line Bundle Compliance on Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections,” Yonsei Med J, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 376–382, May. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. P. O et al., “Guidelines for the Prevention of Intravascular Catheter-Related Infections (2011)”, Accessed: Dec. 24, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/bsi/c-i-dressings/index.html.

- Y. Kato et al., “Impact of mucosal barrier injury laboratory-confirmed bloodstream infection (MBI-LCBI) on central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) in department of hematology at single university hospital in Japan,” J Infect Chemother, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 31–35, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- CDC, Ncezid, and DHQP, “Bloodstream Infection Event (Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection and Non-central Line Associated Bloodstream Infection),” Jan. 2024.

- F. Xie, T. F. Xie, T. Zhou, B. Humphries, and P. J. Neumann, “Do Quality-Adjusted Life-Years Discriminate Against the Elderly? An Empirical Analysis of Published Cost-Effectiveness Analyses,” Value in Health, Mar. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. D. Kim et al., “Developing Criteria for Health Economic Quality Evaluation Tool”. [CrossRef]

- A. Guliyeva, “Measuring quality of life: A system of indicators,” Econ Polit Stud, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 476–491. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B.S. Burckhardt and K. L. Anderson, “The Quality of Life Scale (QOLS): Reliability, Validity, and Utilization,” Health Qual Life Outcomes, vol. 1, p. 60, Oct. 2003. [CrossRef]

- K. Wang, Y. K. Wang, Y. Zhou, N. Huang, Z. Lu, and X. Zhang, “Peripherally inserted central catheter versus totally implanted venous port for delivering medium- to long-term chemotherapy: A cost-effectiveness analysis based on propensity score matching,” Journal of Vascular Access, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 365–374, May. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Gupta, R. N. Gupta, R. Verma, R. K. Dhiman, K. Rajsekhar, and S. Prinja, “Cost-Effectiveness Analysis and Decision Modelling: A Tutorial for Clinicians,” J Clin Exp Hepatol, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 177–184. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Kuntz et al., “Overview of Decision Models Used in Research,” 2013, Accessed: Jun. 18, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK127474/.

- A. H. Briggs, “Statistical Issues in Economic Evaluations,” Encyclopedia of Health Economics, pp. 352–361, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Neumann et al., “Future Directions for Cost-effectiveness Analyses in Health and Medicine,” Original Article Medical Decision Making, vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 767–777. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. H. C. Choong et al., “Use of Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC) for the Infusion of Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Products Is Safe and Effective,” Blood, vol. 136, no. Supplement 1, pp. 41–42, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Comas et al., “Cost-effectiveness Analysis of Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters Versus Central Venous Catheters for in-Hospital Parenteral Nutrition,” J Patient Saf, vol. 18, no. 7, pp. E1109–E1115, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Godino et al., “Effectiveness and cost-efficacy of diuretics home administration via peripherally inserted central venous catheter in patients with end-stage heart failure,” Int J Cardiol, vol. 365, pp. 69–77, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- “Health economic evaluation: Important principles and methodology.” Accessed: Jan. 08, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/lary.23943?saml_referrer.

- N. Buetti et al. 2: “Strategies to prevent central line-associated bloodstream infections in acute-care hospitals, 2022; Update. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang et al., “Effectiveness of antimicrobial-coated central venous catheters for preventing catheter-related blood-stream infections with the implementation of bundles: a systematic review and network meta-analysis,” Ann. Intensive Care, vol. 8, p. 71. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liang, H. Y. Liang, H. Wang, M. Niu, X. Zhu, J. Cai, and X. Wang, “Health-related quality of life before and after hematopoietic stem cell transplant: evidence from a survey in Suzhou, China,” Hematology, vol. 23, no. 9, pp. 626–632, Oct. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).