1. Introduction

Open source hardware (OSH) was first recognised as a pillar of open science strategies in the UNESCO Open Science recommendation in 2021 (UNESCO 2021). This was the result of a decade of advocacy (Arancio 2021; Pearce 2012), as well as the development of open licenses dedicated to hardware (Luis Felipe R et al. 2010), and standardization efforts to improve documentation (Open Source Hardware Association 2010; Bonvoisin et al. 2020). The interest in better documenting and sharing hardware designs is growing. For instance the “OSHWA Certified Projects List” (2023) has close to 3000 projects currently. Most OSH are documented on Git forge platforms (Gitlab and GitHub principally), which do facilitate development, but do not count as academic publishing.

Academic publishing is a part of scholarly communication that encompass the processes of producing, reviewing, organizing, disseminating and preserving scholarly knowledge (Kraker et al. 2016). It usually involves the creation and dissemination of an archived (preserved) version of that knowledge, which has been previously peer-reviewed and can be cited in other academic publications. There are presently three academic journals that fulfil this role partly: the Journal of Open Hardware (ISSN 2475-9066), HardwareX (ISSN 2468-0672) and Hardware (ISSN: 2813-6640). Hardware journal articles present a summary of the hardware documentation in the form of text and images,and usually include links to additional digital assets online, which are not reviewed.

These assets that represent the hardware documentation or “source”, are not in the form of a single plain text file like manuscripts are (Bonvoisin et al. 2017). The situation is similar for software, and in recent years new concepts of peer-review dedicated to software emerged, where reviewers deal with the technical content and quality (meaning the source code), instead of only with a report about the software and its performance. Research software peer review has been developed inside different communities (Ropensci, Pyopensci), and is getting more attention (Wasser 2024). The Journal of Open Source Software (ISSN 2475-9066) combines such a software peer review and an academic paper publication in the form of a “short abstract describing the high-level functionality of the software (and perhaps a figure) as an academic article” (Smith 2016), if the review is positive. In hardware communities, there have been attempts at reviewing hardware documentation (Bonvoisin et al. 2020), as well as self-certification of their open source nature (Open Source Hardware Association 2023), but an academically recognized publication of hardware documentation is still missing. The three hardware journals mentioned above are indeed not reviewing the quality of the documentation itself, focusing on the hardware capacities and its general description.

The success of the Journal of open source software is in part due to the seal of trust the publication process brings to the research software published (Diehl et al. 2025a). Would such a system be useful for research hardware projects and the people behind them ? We define here research hardware engineers’ (RHEs) as people who are participating in a project designing research hardware (RH, which describes “physical objects developed as part of or for a research process” (Milijković et al. 2024)) and feel ownership over that project or part of it. In order to provide a better understanding of the putative motivations of RHEs for publishing, we analysed their responses when asked questions about their project, its documentation and how they made it public (Colomb et al. 2024). In particular, we looked for features they mentioned to be important in the tools they use, or would want to see in the field. For each feature, we derived a specific need or motivation which underlines these feature requests. This report provides a map of these motivations and aims at directing further research and discussions in the design of publication systems which would best serve the interests of the RHE communities.

2. Method

From the transcripts of the fifteen interviews , we derived 52 user stories in the form of “as a [user category], I want [features], in order to [objective]”. The interviews lasted for one hour and followed a script (Mies, Maxeiner, and Colomb 2025). Projects were chosen as a representative sample of successful RH projects. There were no direct questions on the motivation to publish the hardware in a journal, but they were questions about the tools they were using to document and share their work, as well as reasons for them to use these tools. Eleven interviews are available in a slightly revised form in the Open.Make project website blog (Colomb et al. 2024).

We then categorized and sorted these user stories, following four categories: “Growing community of contributors”, “Making the work discoverable and recognized”, “Have a quality control”, and “Facilitate knowledge transfer and production”. We then analysed the stories further while writing and iteratively reviewing this manuscript. This lead to modifications of the categorisation scheme and the organisation of the text. While this process negatively affected the provenance information of the statement made in this article, the readability of the text improved significantly.

Data Availability

A derived form of most of the interviews was published under a CC-BY license with interviewees as coauthors (Colomb et al. 2024). The user stories (Colomb, Maxeiner, and Mies 2025) and the list of interviewees and questions asked (Mies, Maxeiner, and Colomb 2025) are available on Zenodo.

3. Results

We read the transcript of 15 interviews of research hardware engineers, which aimed at understanding their habits and processes, and looked for features RHEs would expect from a hardware publication platform as well as reasons they would want these features. The RHEs had very different background: some were biologist, artists or software engineers becoming makers, others were highly skilled and experienced engineers who had been working in academia or in the industry. In these interviews, RHEs talked mostly about what they did and not much about why they did it. We used the context and our knowledge of the field to derive motivations when features were mentioned without a motivation. We present here the results of the analysis of these user stories. The methodology used aims at providing an exhaustive list of motivations but does not allow for a meaningful quantification of topics mentions or importance. The following sections follow five main categories: two intrinsic motivations (career and personal development) and three extrinsic motivations (one linked to societal impact and values, and two linked to the project: community building and hardware improvement).

3.1. Growing a Community

Several RHEs mentioned that publication may be a way to grow their community of contributors and users, helping the project to be discovered and taken seriously. We separated different aspects of the development of a community of contributors, which starts with raising their interest, continue with facilitating contributions, and end with keeping them in the project or creating their derived projects. In addition, RHEs aim at attracting and engaging users and production partners, which can be seen as other communities around the project.

3.1.1. Attracting Contributions

Projects should find their audience and adopters, who should be able to browse and filter projects as well as access concise information, in order to rapidly be able to decide whether they want to contribute to a project. A publication platform should therefore be compatible with present and future discovery tools, which should allow users to filter projects by topics, stage of the project and skill needed (to use or to contribute), as well as compare different projects.

For this purpose, a condensed, well structured, and easy to consume primers of the project should be available, as well as information about the community and the project’s general aim. On one hand, it might therefore be relevant to have a preview of the hardware (in some cases a video of the hardware in function may be particularly useful), and information about the type of output or data produced by the hardware. Indication about the skills needed to build the hardware should be clear, such that newcomers can evaluate whether the project can be adapted to their specific requirements. On the other hand, information about the community – such as its values, practices, and project governance, should be easily findable. Long term objectives and the overall vision should also be provided. In addition, there should be clear information on the legal framework that allows (or restricts) the reuse of all material.

3.1.2. Facilitating Contributions

In order to facilitate contributions to a project, new contributors should know how they can contribute. They should find information about what contribution is welcome, how they can communicate with the project leads or the community (including internet and social media platforms), and how they can actually make contributions. The tool and infrastructure used to document the hardware project should be indicated (and if possible commonly used in the community) in order to facilitate onboarding of new contributors and prevent confusion for readers.

3.1.3. Motivating Contributors

In order to attract and retain community members, it is important to be able to recognize different contributions to the project. Similar as in open source software projects, varied roles are indeed important and the platform should be able to give credit to every contributor, respectively of their engagement and type of contribution (see

Section 3.4). New contributors may be especially motivated to join if they get to know what kind of credit they can expect.

Finally, RHEs usually expect their project to change platform over time or even to change their main maintainers and leaders. In particular, the community is often distributed over different channels and the publication platform should be agnostic to the different platforms (see

Section 3.5.3). The community structures (governance, succession plan) and communication channels should be indicated, such that the readers can find additional information or ask for help.

3.1.4. Community of Users and Producers

Several RHEs are also selling hardware, or using the community of users to buy hardware components in batches to reduce costs. Publishing their RH documentation package is a way to attract users and buyers and get publicity for their project. In order to attract customers, the documentation should give an overview of the hardware purpose, capabilities and cost. In the particular case of hardware that collects data, an example or a sample of collected data may be provided. It can facilitates the processes of testing the hardware functions and the creation of data analysis workflows , even from people not having access to the hardware. Data standards and repositories specific for the data collected should be indicated. In order to facilitate the use of the hardware and widen the audience, the presence of training material (for instance tutorials) aimed at users with limited engineering experience can be instrumental in creating a large user base.

Additionally, some RHEs are not interested in the production of the hardware and want to attract industrial partners who produce, maintain, repair or recycle the hardware on a larger scale. Industrial partners may reduce the cost of hardware production and therefore attract more users. In addition, mature projects with potential for commercialization usually provide information on the validation and certification of the hardware (this might include tests to perform and existing certification processes), in order to facilitate the work of producers, such that the product can be safely and legally sold.

3.1.5. Promoting Reuse

As readers of hardware documentation, RHEs may often look for solutions to create or modify their own project, often reusing only a small part of the documented third-party hardware. Reuse can therefore be facilitated by providing documentation in a modular way and giving as much background as possible on design choices (see below). This kind of promotion of reuse can help RHEs to gather feedback, which can then be used to improve the original project (see

Section 3.2). The platform should highlight these aspects of the documentation and show how the hardware is or can be treated as different modules.

Information about the development history of the project should also be easily accessible. Indeed, future changes in hardware design, especially by RHEs outside of the original project, is greatly facilitated when design decisions are recorded and explained. This is particularly important for decisions taken in relation to the local infrastructure or material sourcing, as this information will facilitate the adaptation of the design to different objectives and local conditions or legislation. Because reuse can happen after the initial project ended, the hardware documentation should be archived beyond the involvement of the project owners and beyond the existence of the publication platform itself.

3.2. Improving the Hardware and Documentation

RHEs often complained about their difficulties obtaining feedback on their design. Good feedback has the potential to speed up new iterations of the product and improve the design. RHEs are looking for feedback from other RHEs, from manufacturers, and from users. Other engineers could indeed discover imperfections and problems before manufacturing starts, as well as help to make or plan improvement on the design. Feedback from hardware producers may especially help make the hardware ready for commercialization or for local manufacturing, which may have specific requirements. This feedback can also be useful in early stages of development, as knowledge on the life cycle of the hardware or certification processes may direct specific design choices. Finally, feedback from the community of users (including non-experts) might help improve both the hardware design and its documentation. As stated in Section 3.1.5, improving the hardware might also lead to a modularisation of the project, which facilitates reuse, especially for the creation of derived projects.

The platform and the review system should help RHEs find the right balance between being concise and exhaustive, preventing confusion for the readers. This might mean restricting the information available at first sight, for example via the use of warnings or advanced views that hide information only useful for specialists.

3.3. Personal Interest: Learning and Having Fun

RHEs are using open source hardware project to get in contact with new tools or learn new aspects of hardware development. Similarly, a hardware publication platform could be a learning experience for both the authors and the reviewers. Highlighting the history of the project (see Section 3.1.4) is also a way to promote a learning experience for peer-reviewers and future readers. In addition, providing this context information is necessary for the reviewer to give useful and informed review. The whole process should be as straightforward and intuitive as possible.

3.4. Career Development and Recognition

Academic RHEs identified methods to quantify and showcase the impact of their project as an objective for an open hardware publication platform. Publishing open hardware is a way to build their reputation and get more public funding and institutional support. It should also serve as a personal achievement and an official recognition of their skills, such that it can help them get a new job in academia or in the industry. In a virtuous cycle, building recognition for RHEs work will also help the development of a community of professional contributors in the project (see Section 3.1.3). This also implies the recognition for work done in the maturation of hardware, for instance when a prototype is made ready for the market. RHEs indeed mentioned that they could get recognition for a novel RH, but the work to get it to a more advanced or robust design was more difficult to get recognized (or paid) for.

Some RHEs want to control when they are going public, as part of their strategy to maximize impact and control the narrative around a project. This implies that the platform should provide the possibility to get private content reviewed, so RHEs can make sure only content reaching a certain quality threshold is made public.

3.5. Value-Driven Motivation

3.5.1. Inclusive Ecosystem and Communities

Most projects address a global audience, hence a publication platform has to be inclusive for projects created anywhere. In particular it should avoid financial or language barriers for readers and authors. This ideally includes both multilingualism of the platform and the absence of unexplained jargon terms.

3.5.2. Compatibility with Existing Workflows

Hardware project are usually using several online tools for documentation and communication.In particular, RHEs often use continuous integration (CI) tools that automatically run several checks in the repository. In order to facilitate modification of the hardware documentation during review, a platform should allow RHEs to use their usual workflows. This means it should facilitate submissions coming from different hardware development software and platforms, and that the documentation change happening during review should be visible on these platforms. This includes the metadata usually created during the submission process thatshould be exported to and reimported from the documentation platform. The platform should indeed be designed to facilitate the publication of new versions of the hardware (see

Section 3.4).

3.5.3. Transparent and Trustworthy

Last but not least, the platform should inspire trust in the published projects. The quality assurance should be thorough, transparent and easy to understand. The platform should be endorsed by the community (or communities), well known, and easy to access.

4. Discussion

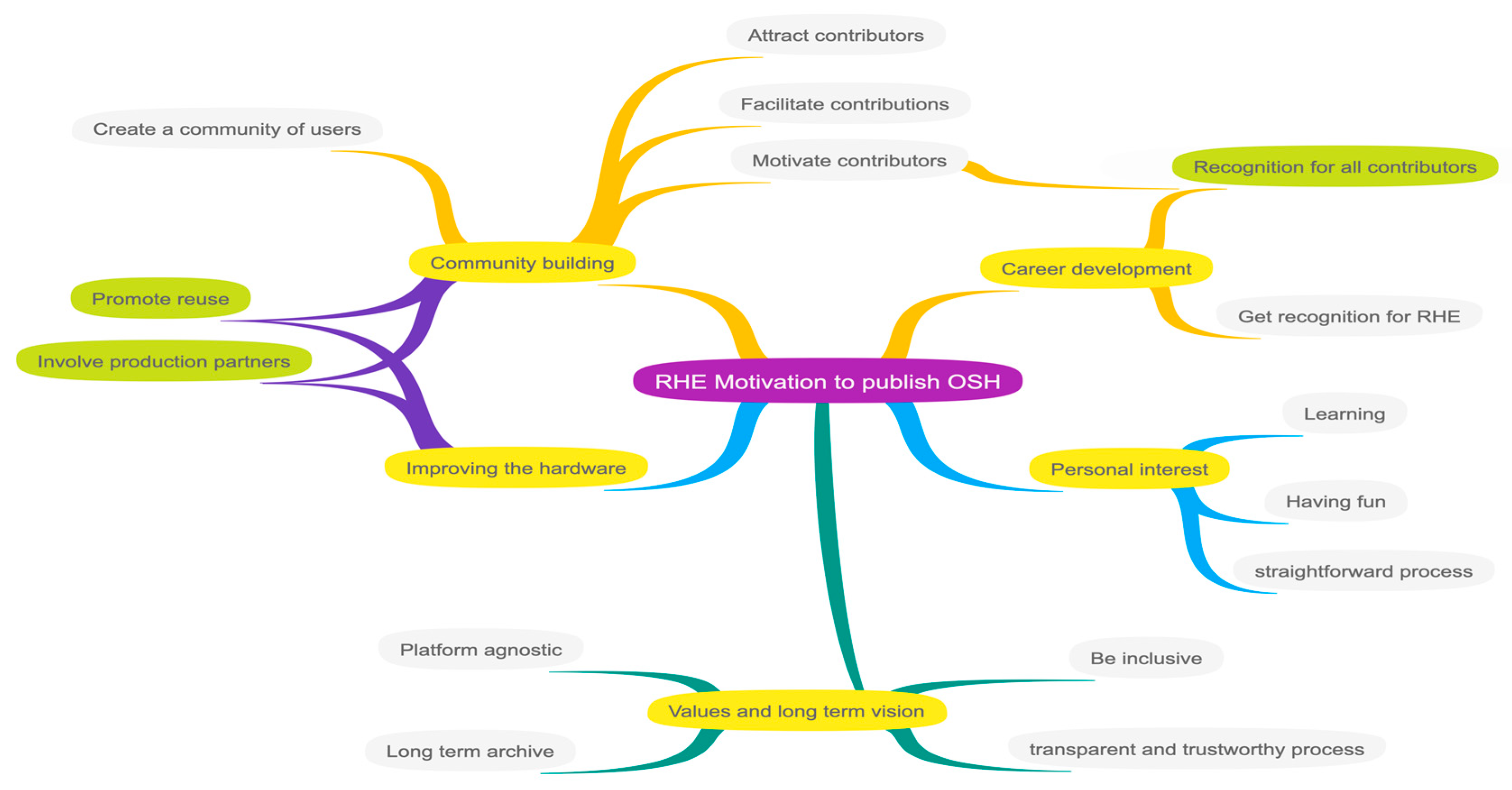

Based on 15 interviews of prominent open source hardware projects (Colomb et al. 2024), our qualitative analysis suggests that the motivations for RHEs to invest time in the publication of their research hardware is to build a community, to improve the hardware, to get advancement in their career, to learn new things and to follow their values (

Figure 1). By using this indirect and qualitative approach, we hope we grasped most of the different motivations RHEs may have. We did not find contradictory wishes and our method does not allow to prioritize the different aspects. After presenting an overview of the results, we will discuss the specific aspects of community building, needs for an archived version, researchers values in diversity equity and inclusivity, the peer review process, and how the whole process could be a positive experience.

Our motivation graph is larger than those reported in other studies (Diehl et al. 2025; Hausberg and Spaeth 2020; Li et al. 2021), suggesting our methodology allowed for a larger scope of motivation. The community building aspects were previously not analysed. This is particularly visible in the analysis of interviews of research software engineers who published in the Journal of Open Source Software (JOSS) (Diehl et al. 2025), where community building was not reported in the paper, although every podcast episode had a section on what type of contribution is most welcome.

RHEs intend to use RH publications to raise awareness and trust in their project, hoping to attract users, contributors, and hardware producers. It can also help consolidating teams by motivating current contributors to continue to work on the project, by providing recognition for RHEs and their work,including work to elevate the maturity level of the product. It should brings a seal of quality that is valued by other engineers and researchers who could then become new contributors or users in the project. RH should therefore be considered a research output and should provide an entity that can be cited (such that citation number can be quantified), has a persistent identifier and can be easily discovered (Mathiak et al. 2023), for example through indexing in aggregated databases using specific metadata (Bonvoisin et al. 2020). The platform may include the production of a text manuscript used for citation and entry in the usual academic databases for academic journals, as JOSS is doing (Diehl et al. 2025b). A papers may also be a way to distribute the knowledge in a format recognized by non-engineers researchers, who may get inspired by the project, and become new users or contributors.

Our analysis indeed shows that community development aspects are extremely important. This suggests that a hardware publication should not only report about the hardware product but also about the hardware development process and community practices. While these aspects were previously recognized in the literature (Bonvoisin and Mies 2018; Mies, Häuer, and Hassan 2022), and in the Turing way book chapter on open hardware (Community 2022)(

https://book.the-turing-way.org/reproducible-research/open/open-hardware), their importance has probably been underestimated so far, since hardware journals do not have a section about community practices. We therefore thrived for investigating the needs for a hardware publication system which considers not only the hardware product and replicability, but also the documentation of the hardware development process, especially its collaborative aspects.

On the other hand, the documentation should be archived to be found even if the main project is discontinued, in order to facilitate late reuse. This inherent discrepancy between making this snapshot of the project at a certain time (a peer reviewed, archived version), and growing a community over time and associated hardware iterations is also an ongoing research question for data publication systems (Klump et al. 2024).

Interestingly, core values of open science about diversity, equity and inclusivity (UNESCO 2021) were mentioned by RHEs. In particular, the financial barriers for researchers in low and middle income countries is a concern, as RHEs want to build inclusive communities. A publication platform should then be free of charge for readers and authors (UNESCO 2024) to fulfil this requirement. This is mirrored by the choice made by the Journal of Open Hardware to become a diamond open access journal (The Journal of Open Hardware Editorial Board 2024). This can also be related to the previously reported “moral obligation” to apply an open source hardware license (Li et al. 2021). However, research hardware publication does not have to come with a license requirement: like for data and software, one can distinguish hardware openness and hardware documentation availability, using the FAIR principles (Chue Hong et al. 2021; Wilkinson et al. 2016).

Concerning the quality control aspects, a review system should be incorporated with tools already in use in the community (mostly GitHub and GitLab), in order to lower the technological hurdles, and it should be possible to run on RH that are not public. The improvement of hardware documentation should be an important objective of the publication process. Specific aspects of the process could be derived from the DIN SPEC 3105-1 (DIN e.V. 2020), while the peer review should be interesting, pleasant to use, and an opportunity to learn. It can be interesting to test the inclusion of quality management tools inside the peer review (Mies et al. 2020), which would also call for reviews at early stages of the RH development.

Previous work (Hausberg and Spaeth 2020) suggests that expected skill learning and having fun correlate with the time spent hacking. This resonates with the notion of “having fun” during the open review process in the JOSS journal (Diehl et al. 2025, see also the josscast used as raw data). The hardware publication process has the potential to also become a pleasant exchange of ideas and knowledge, if the tooling allow creative ideas and discussions to emerge.

5. Conclusions

The Journal of Open Source Software (JOSS) has been successfully answering a need of research software engineer. It provides recognition for the authors and a quality seal for the software, it has also be quite instrumental in the development of new career pathways for software engineers. JOSS review system that focus on the code and its documentation and that works as an open discussion was reported to please the authors and the reviewers (Diehl et al. 2025b). Our analysis of research hardware engineers motivation suggests that such a system could also be useful for them, as they also wish for a review system leading to better hardware and a journal bringing academic recognition of their work. However, our analysis suggests a need for additional features, some are probably shared with the software community (features directed toward community building and nurturing as well as inclusivity and diversity), while others may be specific to hardware communities (features directed toward production partners and structural modularization). In brief, a research hardware publication workflow could build on the JOSS system, while implementing additional features to thrive the development of research hardware engineers communities: A research hardware publication system should be integrated in the project workflow and provide a specific snapshot of a project. The publication can then be recognized by the academic institutions (creating new career potential), and become an entry point for new community members, who will further develop, use, or produce the hardware. To win the trust of RHEs and the academic institutions, the development of such a platform has therefore both a technical and a community aspect, and we hope this paper will help thrive new discussions in the community.

Author Contributions

J.C.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing - original draft, and Writing - review & editing. M.M.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, and Writing - review & editing. TL: Funding acquisition, and Writing - review & editing. R.M.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, and Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgements

We thank the students who helped with the transcription of the interview and their editing for the blog post versions: Reeh, Fabio (

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3583-4841), and Guerrero, Diana Americano. We also thank every research hardware engineer who participated in the interviews: Serrano, Javier (

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0522-4471); Diez, Amanda; Stirling, Julian (

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8270-9237); de Vos, Jerry (

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-3240-1081); Chhabra, Vaibhav (

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-1504-1072); Read, Robert (

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4749-7045); Aronson, Rory; Rogers, Alex; Gaudenz, Urs (

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0845-3202); Camprodon, Guillem (

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3610-0009); Kodandaramaiah, Suhasa (

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7767-2644); Padilla Huamantinco, Pierre Guillermo (

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4321-1337); Jonveaux, Luc; and Dusseiller, Marc.

Conflicts of Interest

No competing interest

References

- Arancio, Julieta Cecilia. 2021. ‘Opening Up The Tools For Doing Science: The Case Of The Global Open Science Hardware Movement’. International Journal of Engineering, Social Justice, and Peace 8 (2): 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Bonvoisin, Jérémy, Robert Mies, Jean-François Boujut, and Rainer Stark. 2017. ‘What Is the “Source” of Open Source Hardware?’ Journal of Open Hardware 1 (1): 5. [CrossRef]

- Bonvoisin, Jérémy, Jenny Molloy, Martin Häuer, and Tobias Wenzel. 2020. ‘Standardisation of Practices in Open Source Hardware’. Journal of Open Hardware 4 (1): 2. [CrossRef]

- Colomb, Julien, Moritz Maxeiner, and Robert Mies. 2025. ‘Research Hardware Publication - User Stories’. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Colomb, Julien, Robert Mies, Moritz Maxeiner, Fabio Reeh, Mik Schutte, Diana Americano Guerrero, Javier Serrano, et al. 2024. ‘OpenMake Blogposts and Interviews of Open Hardware Projects’. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Diehl, Patrick, Charlotte Soneson, Rachel C Kurchin, Ross Mounce, and Daniel S Katz. 2025a. ‘The Journal of Open Source Software (JOSS): Bringing Open-Source Software Practices to the Scholarly Publishing Communityfor Authors, Reviewers, Editors, and Publishers’. Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication 12 (2). [CrossRef]

- ———. 2025b. ‘The Journal of Open Source Software (JOSS): Bringing Open-Source Software Practices to the Scholarly Publishing Communityfor Authors, Reviewers, Editors, and Publishers’. Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication 12 (2). [CrossRef]

- DIN e.V. 2020. ‘DIN SPEC 3105-1:2020-07, Open Source Hardware_- Teil_1: Anforderungen an Die Technische Dokumentation; Text Englisch’. DIN Media GmbH. [CrossRef]

- Kraker, Peter, Daniel Dörler, Andreas Ferus, Robert Gutounig, Florian Heigl, Christian Kaier, Katharina Rieck, Elena Šimukovič, and Michela Vignoli. 2016. ‘The Vienna Principles: A Vision for Scholarly Communication in the 21st Century’. Mitteilungen Der Vereinigung Österreichischer Bibliothekarinnen Und Bibliothekare 69 (3–4): 436–46. [CrossRef]

- Li, Zhuoxuan, Warren Seering, Maria Yang, and Charles Eesley. 2021. ‘Understanding the Motivations for Open-Source Hardware Entrepreneurship’. Cambridge University Press. https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/139657.

- Luis Felipe R, Murillo, Pietari Kauttu, Pujol Priego Laia, Wareham Jonathan, and Katz Andrew. 2010. ‘Open Hardware Licences: Parallels and Contrasts : Open Science Monitor Case Study’. https://core.ac.uk/outputs/287760857/?utm_source=pdf&utm_medium=banner&utm_campaign=pdf-decoration-v1.

- Mathiak, Brigitte, Nick Juty, Alessia Bardi, Julien Colomb, and Peter Kraker. 2023. ‘What Are Researchers’ Needs in Data Discovery? Analysis and Ranking of a Large-Scale Collection of Crowdsourced Use Cases’. Data Science Journal 22 (February):3. [CrossRef]

- Mies, Robert, Moritz Maxeiner, and Julien Colomb. 2025. ‘Open Make Interviews: Questions and List of Interviewees’. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Milijković, Nadica, Julien Colomb, Moritz Maxeiner, Ana Petrus, Robert Mies, Vladimir Milovanović, Mirco Panighel, Alexander Struck, and FAIR Principles for Research Hardware IG. 2024. ‘Research Hardware Definition’. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Open Source Hardware Association. 2010. ‘Open Source Hardware (OSHW) Definition 1.0’. 2010. https://www.oshwa.org/definition/.

- ———. 2023. ‘OSHWA Certified Projects List’. 2023. https://certification.oshwa.org/list.html.

- Pearce, Joshua M. 2012. ‘Building Research Equipment with Free, Open-Source Hardware’. Science 337 (6100): 1303–4. [CrossRef]

- Smith, Arfon. 2016. ‘Announcing The Journal of Open Source Software | Arfon Smith’. 5 May 2016. https://www.arfon.org/announcing-the-journal-of-open-source-software.

- UNESCO. 2021. ‘UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science’. UNESCO. [CrossRef]

- ———. 2024. ‘Diamond Open Access: Global Paradigm Shift in Scholarly Publishing | UNESCO’. 2024. https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/diamond-open-access-global-paradigm-shift-scholarly-publishing.

- Wasser, Leah. 2024. ‘It’s Been a Long Short Road: The Monumental Past 2 Years of pyOpenSci’. pyOpenSci. 30 August 2024. https://www.pyopensci.org/blog/what-pyopensci-accomplished-with-two-years-of-funding.html.

- Working Group Open Access and Scholarly Communication of the Open Access Network Austria. 2016. ‘Vienna Principles a Vision for Scholarly Communication’. 2016. https://viennaprinciples.org/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).