Submitted:

12 February 2025

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

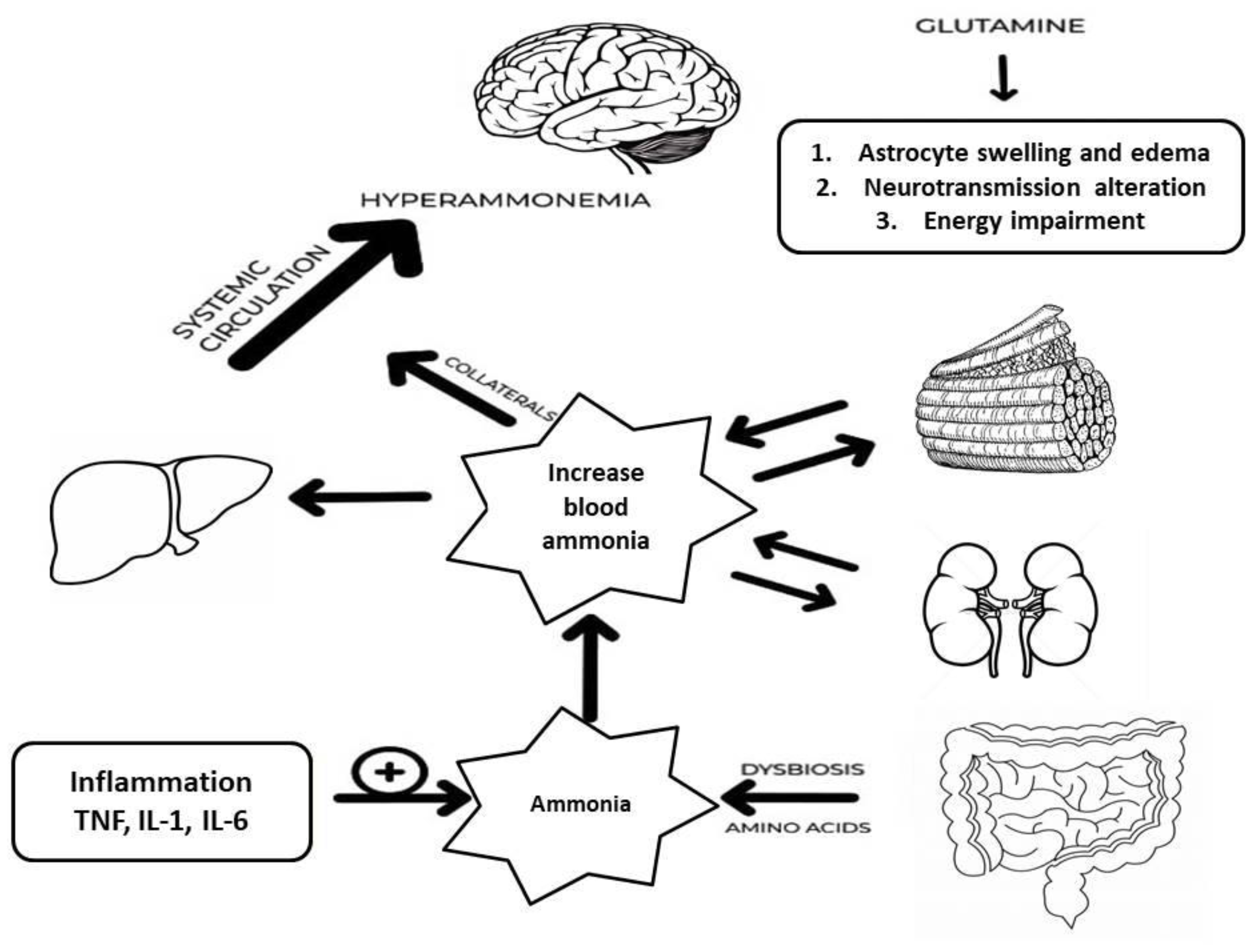

2. Pathophysiology

2.1. Role of Ammonia

2.1.1. Ammonia Production

2.1.2. Ammonia Excretion

2.2. Ammonia Neurotoxicity

2.2.1. Astrocyte Dysfunction Theory

2.3. Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha

2.4. Role of Gut Microbiota: Gut-Liver-Brain Axis

2.5. Neurotransmitters and Minerals Involved in the Pathophysiology of Hepatic Encephalopathy

2.5.1. Glutamate

2.5.2. Monoamines: Histamine and Serotonin

2.5.3. Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid

2.5.4. Manganese

2.6. Risk Factors Contributing to the Development of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy

2.7. Mechanisms Underlying Cognitive Dysfunction in Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy

2.8. Differences in Brain Activity Between Averted Hepatic Encephalopathy and Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy

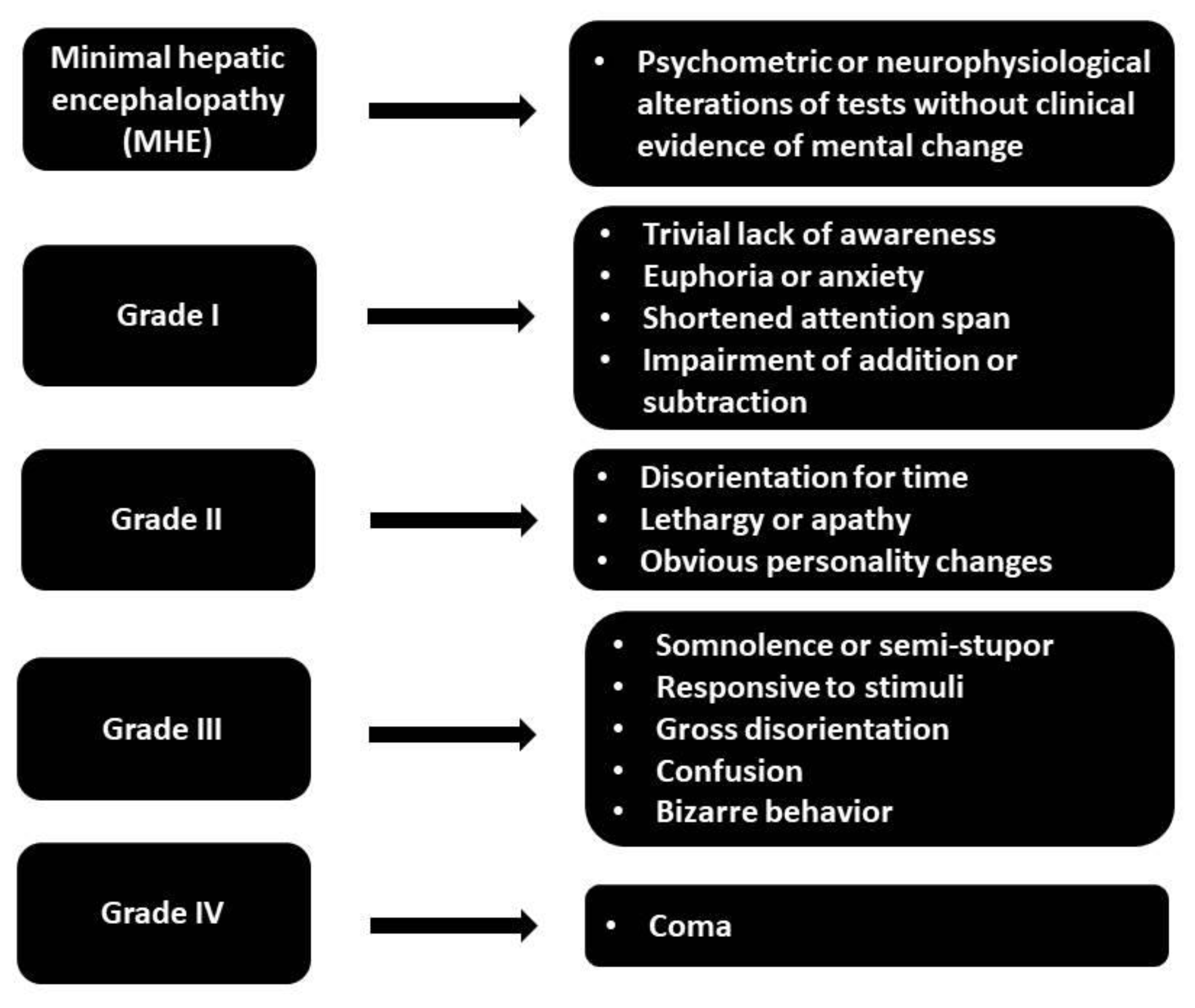

3. Definition

3.1. Clinical Manifestations

3.2. Clinical Significance

3.2.1. Effect of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy on Quality of Life

3.2.2. Sleep and Health-Related Quality of Life

3.2.3. Memory and Learning Difficulties in Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy

3.2.4. Driving and Navigational Skills in Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy

3.2.5. Falls in Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy

3.2.6. Employment and Socioeconomic Burden of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy

3.2.7. Natural History and Survival in Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy

4. Diagnosis and Available Tests

4.1. Psychometric Testing

4.1.1. Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score (PHES)

4.1.2. Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS)

4.1.3. Animal Naming Test (ANT)

4.1.4. Continuous Response Time (CRT) Test

4.1.5. Inhibitory Control Test (ICT)

4.1.6. EncephalApp (Stroop App) and QuickStroop

4.1.7. SCAN Test

4.2. Electrophysiologic Tests

4.2.1. Electroencephalogram Monitoring

4.2.2. Evoked Potentials

4.2.3. Critical Flicker Frequency Testing

4.3. Biomarkers

4.4. Evaluation for Precipitating Causes

4.5. Challenges in Diagnosing Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy

5. Management

5.1. Pharmacological Management

5.2. Nutritional Therapies and Dietary Modifications

5.3. Role of Liver Transplant

6. Interesting Points of Discussion

6.1. Prevalence and Incidence of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy

6.2. Impact of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy on Quality of Life

6.3. Continuum of Hepatic Encephalopathy from Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy to Overted Hepatic Encephalopathy and Prognosis

6.4. Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy Versus Hepatic Encephalopathy Stage I in Clinical Practice

7. Future Perspectives and Current Trends

7.1. Development of Biomarkers

7.2. Development of Medical Calculators

7.3. Preventive Medicine

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALD | Alcohol-related liver disease |

| ANT | Animal Naming Test |

| AP | Astrocyte Population |

| AEPs | Auditory Evoked Potentials |

| BAEPs | Brainstem Auditory Evoked Potentials |

| BCAAs | Branched-Chain Amino Acids |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| CFF | Critical Flicker Frequency |

| CNP | Cortical Neuron Population |

| CLD | Chronic Liver Disease |

| CHC | Chronic Hepatitis C Virus |

| CHB | Chronic Hepatitis B Virus |

| cGMP | Cyclase Guanylyl Monophosphate |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CTP | Child-Turcotte-Pugh |

| DFCs | Distinguishing Features of DFCs |

| DMN | Default Mode Network |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| HE | Hepatic Encephalopathy |

| HRQOL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| ICT | Inhibitory Control Test |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ISHEN | International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism |

| LOLA | L-Ornithine L-Aspartate |

| MHE | Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy |

| MDF | Mean Dominant Frequency |

| Mn | Manganese |

| NAFLD | Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease |

| NHP | Nottingham Health Profile |

| NOS | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale |

| NMDA | N-Methyl-D-Aspartic Acid |

| OHE | Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy |

| PHES | Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score |

| pVEPs | Pattern Visual Evoked Potentials |

| PPI | Proton Pump Inhibitors |

| RBANS | Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status |

| SIP | Sickness Impact Profile |

| TNF-alpha | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| VEPs | Visual Evoked Potentials |

| WHC | West Haven Criteria |

References

- Asrani, S.K.; Devarbhavi, H.; Eaton, J.; Kamath, P.S. Burden of Liver Diseases in the World. J Hepatol 2019, 70, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devarbhavi, H.; Asrani, S.K.; Arab, J.P.; Nartey, Y.A.; Pose, E.; Kamath, P.S. Global Burden of Liver Disease: 2023 Update. J Hepatol 2023, 79, 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepatic Encephalopathy in Chronic Liver Disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. J Hepatol 2014, 61, 642–659. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzano, T.; Forteza, J.; Borreda, I.; Molina, P.; Giner, J.; Leone, P.; Urios, A.; Montoliu, C.; Felipo, V. Histological Features of Cerebellar Neuropathology in Patients With Alcoholic and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2018, 77, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gómez, M.; Montagnese, S.; Jalan, R. Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Acute Decompensation of Cirrhosis and Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. J Hepatol 2015, 62, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissenborn, K.; Ennen, J.C.; Schomerus, H.; Rückert, N.; Hecker, H. Neuropsychological Characterization of Hepatic Encephalopathy. J Hepatol 2001, 34, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Cordoba, J.; Mullen, K.D.; Amodio, P.; Shawcross, D.L.; Butterworth, R.F.; Morgan, M.Y. Review Article: The Design of Clinical Trials in Hepatic Encephalopathy--an International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism (ISHEN) Consensus Statement. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011, 33, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodio, P.; Montagnese, S.; Gatta, A.; Morgan, M.Y. Characteristics of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 2004, 19, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridola, L.; Cardinale, V.; Riggio, O. The Burden of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: From Diagnosis to Therapeutic Strategies. Ann Gastroenterol 2018, 31, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauridsen, M.M.; Schaffalitzky de Muckadell, O.B.; Vilstrup, H. Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy Characterized by Parallel Use of the Continuous Reaction Time and Portosystemic Encephalopathy Tests. Metab Brain Dis 2015, 30, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Thacker, L.R.; Heuman, D.M.; Gibson, D.P.; Sterling, R.K.; Stravitz, R.T.; Fuchs, M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Wade, J.B. Driving Simulation Can Improve Insight into Impaired Driving Skills in Cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 2012, 57, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapper, E.B.; Parikh, N.D.; Waljee, A.K.; Volk, M.; Carlozzi, N.E.; Lok, A.S.-F. Diagnosis of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Systematic Review of Point-of-Care Diagnostic Tests. Am J Gastroenterol 2018, 113, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Córdoba, J.; López-Hellín, J.; Planas, M.; Sabín, P.; Sanpedro, F.; Castro, F.; Esteban, R.; Guardia, J. Normal Protein Diet for Episodic Hepatic Encephalopathy: Results of a Randomized Study. J Hepatol 2004, 41, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montano-Loza, A.J.; Meza-Junco, J.; Prado, C.M.M.; Lieffers, J.R.; Baracos, V.E.; Bain, V.G.; Sawyer, M.B. Muscle Wasting Is Associated with Mortality in Patients with Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012, 10, 166–173, 173.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalan, R.; Kapoor, D. Enhanced Renal Ammonia Excretion Following Volume Expansion in Patients with Well Compensated Cirrhosis of the Liver. Gut 2003, 52, 1041–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.-H. Mechanisms of the Effects of Acidosis and Hypokalemia on Renal Ammonia Metabolism. Electrolyte Blood Press 2011, 9, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasarathy, S.; Mookerjee, R.P.; Rackayova, V.; Rangroo Thrane, V.; Vairappan, B.; Ott, P.; Rose, C.F. Ammonia Toxicity: From Head to Toe? Metab Brain Dis 2017, 32, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, I.D.; Mitch, W.E.; Sands, J.M. Urea and Ammonia Metabolism and the Control of Renal Nitrogen Excretion. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015, 10, 1444–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawaro, T.; Yang, A.; Dixit, D.; Bridgeman, M.B. Management of Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Primer. Ann Pharmacother 2016, 50, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircheis, G.; Nilius, R.; Held, C.; Berndt, H.; Buchner, M.; Görtelmeyer, R.; Hendricks, R.; Krüger, B.; Kuklinski, B.; Meister, H.; et al. Therapeutic Efficacy of L-Ornithine-L-Aspartate Infusions in Patients with Cirrhosis and Hepatic Encephalopathy: Results of a Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Study. Hepatology 1997, 25, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakouh, N.; Benjelloun, F.; Cherif-Zahar, B.; Planelles, G. The Challenge of Understanding Ammonium Homeostasis and the Role of the Rh Glycoproteins. Transfus Clin Biol 2006, 13, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saparov, S.M.; Liu, K.; Agre, P.; Pohl, P. Fast and Selective Ammonia Transport by Aquaporin-8. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 5296–5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felipo, V.; Butterworth, R.F. Neurobiology of Ammonia. Prog Neurobiol 2002, 67, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, J.; Norenberg, M.D. Glutamine: A Trojan Horse in Ammonia Neurotoxicity. Hepatology 2006, 44, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, M.; Baccaro, M.E.; Ríos, J.; Martín-Llahí, M.; Uriz, J.; Ruiz del Arbol, L.; Planas, R.; Monescillo, A.; Guarner, C.; Crespo, J.; et al. Risk Factors for Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Cirrhosis and Refractory Ascites: Relevance of Serum Sodium Concentration. Liver Int 2010, 30, 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umapathy, S.; Dhiman, R.K.; Grover, S.; Duseja, A.; Chawla, Y.K. Persistence of Cognitive Impairment after Resolution of Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol 2014, 109, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, R.F. Hepatic Encephalopathy in Cirrhosis: Pathology and Pathophysiology. Drugs 2019, 79, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, R.F. Neuronal Cell Death in Hepatic Encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 2007, 22, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.P.; Aggarwal, A.; Krieger, D.; Easley, K.A.; Karafa, M.T.; Van Lente, F.; Arroliga, A.C.; Mullen, K.D. Correlation between Ammonia Levels and the Severity of Hepatic Encephalopathy. Am J Med 2003, 114, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.C.; Hu, S. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Potentiates Glutamate Neurotoxicity in Human Fetal Brain Cell Cultures. Dev Neurosci 1994, 16, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, M.; Lucidi, C.; Pentassuglio, I.; Giannelli, V.; Giusto, M.; Di Gregorio, V.; Pasquale, C.; Nardelli, S.; Lattanzi, B.; Venditti, M.; et al. Increased Risk of Cognitive Impairment in Cirrhotic Patients with Bacterial Infections. J Hepatol 2013, 59, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Duan, Z.P.; Ha, D.K.; Bengmark, S.; Kurtovic, J.; Riordan, S.M. Synbiotic Modulation of Gut Flora: Effect on Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2004, 39, 1441–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Fagan, A.; Gavis, E.A.; Kassam, Z.; Sikaroodi, M.; Gillevet, P.M. Long-Term Outcomes of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Patients With Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1921–1923.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterworth, R.F. Glutamate Transporters in Hyperammonemia. Neurochem Int 2002, 41, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Lavoie, J.; Lé, N.L.; Szerb, J.C.; Butterworth, R.F. Neurochemical and Electrophysiological Studies on the Inhibitory Effect of Ammonium Ions on Synaptic Transmission in Slices of Rat Hippocampus: Evidence for a Postsynaptic Action. Neuroscience 1990, 37, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomero-Gallagher, N.; Zilles, K. Neurotransmitter Receptor Alterations in Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Review. Arch Biochem Biophys 2013, 536, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, A.; Cangiano, C.; Fiaccadori, F.; Ghinelli, F.; Merli, M.; Pelosi, G.; Riggio, O.; Rossi Fanelli, F.; Sacchini, D.; Stortoni, M.; et al. Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid Amino Acid Patterns in Hepatic Encephalopathy. Dig Dis Sci 1982, 27, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erecińska, M.; Pastuszko, A.; Wilson, D.F.; Nelson, D. Ammonia-Induced Release of Neurotransmitters from Rat Brain Synaptosomes: Differences between the Effects on Amines and Amino Acids. J Neurochem 1987, 49, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantzer, R.; O’Connor, J.C.; Lawson, M.A.; Kelley, K.W. Inflammation-Associated Depression: From Serotonin to Kynurenine. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.A. Ammonia, the GABA Neurotransmitter System, and Hepatic Encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 2002, 17, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häussinger, D.; Sies, H. Hepatic Encephalopathy: Clinical Aspects and Pathogenetic Concept. Arch Biochem Biophys 2013, 536, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, M.; Agusti, A.; Llansola, M.; Montoliu, C.; Strömberg, J.; Malinina, E.; Ragagnin, G.; Doverskog, M.; Bäckström, T.; Felipo, V. GR3027 Antagonizes GABAA Receptor-Potentiating Neurosteroids and Restores Spatial Learning and Motor Coordination in Rats with Chronic Hyperammonemia and Hepatic Encephalopathy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2015, 309, G400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Normandin, L.; Hazell, A.S. Manganese Neurotoxicity: An Update of Pathophysiologic Mechanisms. Metab Brain Dis 2002, 17, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouabid, S.; Tinakoua, A.; Lakhdar-Ghazal, N.; Benazzouz, A. Manganese Neurotoxicity: Behavioral Disorders Associated with Dysfunctions in the Basal Ganglia and Neurochemical Transmission. J Neurochem 2016, 136, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, S.; Xiang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Zu, H.; Wang, J.; Lv, J.; Zhang, X.; Meng, F.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Cirrhotic Patients with Different Etiologies. Portal Hypertension & Cirrhosis 2023, 2, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, P.; Christensen, J.; Weissenborn, K.; Watson, H.; Vilstrup, H. Epilepsy as a Risk Factor for Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Cohort Study. BMC Gastroenterol 2016, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-V.; Chen, J.-D.; Wu, W.-T.; Huang, K.-C.; Lin, H.-Y.; Han, D.-S. Is Sarcopenia Associated with Hepatic Encephalopathy in Liver Cirrhosis? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Formos Med Assoc 2019, 118, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawcross, D.L.; Wright, G.; Olde Damink, S.W.M.; Jalan, R. Role of Ammonia and Inflammation in Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 2007, 22, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoliu, C.; Piedrafita, B.; Serra, M.A.; del Olmo, J.A.; Urios, A.; Rodrigo, J.M.; Felipo, V. IL-6 and IL-18 in Blood May Discriminate Cirrhotic Patients with and without Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009, 43, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipo, V.; Urios, A.; Montesinos, E.; Molina, I.; Garcia-Torres, M.L.; Civera, M.; Olmo, J.A.D.; Ortega, J.; Martinez-Valls, J.; Serra, M.A.; et al. Contribution of Hyperammonemia and Inflammatory Factors to Cognitive Impairment in Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 2012, 27, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Franco, Ó.; Morin, J.-P.; Cortés-Sol, A.; Molina-Jiménez, T.; Del Moral, D.I.; Flores-Muñoz, M.; Roldán-Roldán, G.; Juárez-Portilla, C.; Zepeda, R.C. Cognitive Impairment After Resolution of Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Neurosci 2021, 15, 579263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felipo, V. Hepatic Encephalopathy: Effects of Liver Failure on Brain Function. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013, 14, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Wu, B.; Chen, T.; Diao, W.; Jia, Z. Altered Intrinsic Brain Activity in Patients with Hepatic Encephalopathy. J Neurosci Res 2021, 99, 1337–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.-J.; Jiao, Y.; Zhu, X.-Q.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Liu, J.-C.; Wen, S.; Teng, G.-J. Brain Dysfunction Primarily Related to Previous Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy Compared with Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: Resting-State Functional MR Imaging Demonstration. Radiology 2013, 266, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, R.C.; Smith, G.E.; Waring, S.C.; Ivnik, R.J.; Tangalos, E.G.; Kokmen, E. Mild Cognitive Impairment: Clinical Characterization and Outcome. Arch Neurol 1999, 56, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikkers, L.; Jenko, P.; Rudman, D.; Freides, D. Subclinical Hepatic Encephalopathy: Detection, Prevalence, and Relationship to Nitrogen Metabolism. Gastroenterology 1978, 75, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomerus, H.; Hamster, W.; Blunck, H.; Reinhard, U.; Mayer, K.; Dölle, W. Latent Portasystemic Encephalopathy. I. Nature of Cerebral Functional Defects and Their Effect on Fitness to Drive. Dig Dis Sci 1981, 26, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissenborn, K.; Heidenreich, S.; Giewekemeyer, K.; Rückert, N.; Hecker, H. Memory Function in Early Hepatic Encephalopathy. J Hepatol 2003, 39, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, A.H. “What’s in a Name?” Improving the Care of Cirrhotics. J Hepatol 2000, 32, 859–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenci, P.; Lockwood, A.; Mullen, K.; Tarter, R.; Weissenborn, K.; Blei, A.T. Hepatic Encephalopathy--Definition, Nomenclature, Diagnosis, and Quantification: Final Report of the Working Party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna, 1998. Hepatology 2002, 35, 716–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, N.M.; Mullen, K.D.; Sanyal, A.; Poordad, F.; Neff, G.; Leevy, C.B.; Sigal, S.; Sheikh, M.Y.; Beavers, K.; Frederick, T.; et al. Rifaximin Treatment in Hepatic Encephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2010, 362, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, J.S. Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy Matters in Daily Life. World J Gastroenterol 2008, 14, 3609–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Saeian, K.; Schubert, C.M.; Hafeezullah, M.; Franco, J.; Varma, R.R.; Gibson, D.P.; Hoffmann, R.G.; Stravitz, R.T.; Heuman, D.M.; et al. Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy Is Associated with Motor Vehicle Crashes: The Reality beyond the Driving Test. Hepatology 2009, 50, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyan, A.S.; Hughes, R.D.; Shawcross, D.L. Changing Face of Hepatic Encephalopathy: Role of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. World J Gastroenterol 2010, 16, 3347–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralnek, I.M.; Hays, R.D.; Kilbourne, A.; Rosen, H.R.; Keeffe, E.B.; Artinian, L.; Kim, S.; Lazarovici, D.; Jensen, D.M.; Busuttil, R.W.; et al. Development and Evaluation of the Liver Disease Quality of Life Instrument in Persons with Advanced, Chronic Liver Disease--the LDQOL 1.0. Am J Gastroenterol 2000, 95, 3552–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Guyatt, G.; Kiwi, M.; Boparai, N.; King, D. Development of a Disease Specific Questionnaire to Measure Health Related Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Liver Disease. Gut 1999, 45, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeneweg, M.; Quero, J.C.; De Bruijn, I.; Hartmann, I.J.; Essink-bot, M.L.; Hop, W.C.; Schalm, S.W. Subclinical Hepatic Encephalopathy Impairs Daily Functioning. Hepatology 1998, 28, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.R.; Lindor, K.D.; Malinchoc, M.; Petz, J.L.; Jorgensen, R.; Dickson, E.R. Reliability and Validity of the NIDDK-QA Instrument in the Assessment of Quality of Life in Ambulatory Patients with Cholestatic Liver Disease. Hepatology 2000, 32, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mina, A.; Moran, S.; Ortiz-Olvera, N.; Mera, R.; Uribe, M. Prevalence of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy and Quality of Life in Patients with Decompensated Cirrhosis. Hepatol Res 2014, 44, E92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Heuman, D.M.; Wade, J.B.; Gibson, D.P.; Saeian, K.; Wegelin, J.A.; Hafeezullah, M.; Bell, D.E.; Sterling, R.K.; Stravitz, R.T.; et al. Rifaximin Improves Driving Simulator Performance in a Randomized Trial of Patients with Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 478–487.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnese, S.; De Pittà, C.; De Rui, M.; Corrias, M.; Turco, M.; Merkel, C.; Amodio, P.; Costa, R.; Skene, D.J.; Gatta, A. Sleep-Wake Abnormalities in Patients with Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2014, 59, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montagnese, S.; Middleton, B.; Skene, D.J.; Morgan, M.Y. Night-Time Sleep Disturbance Does Not Correlate with Neuropsychiatric Impairment in Patients with Cirrhosis. Liver Int 2009, 29, 1372–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, M.; Córdoba, J.; Jacas, C.; Flavià, M.; Esteban, R.; Guardia, J. Neuropsychological Abnormalities in Cirrhosis Include Learning Impairment. J Hepatol 2006, 44, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, A.H.; Weissenborn, K.; Bokemeyer, M.; Tietge, U.; Burchert, W. Correlations between Cerebral Glucose Metabolism and Neuropsychological Test Performance in Nonalcoholic Cirrhotics. Metab Brain Dis 2002, 17, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erceg, S.; Monfort, P.; Hernández-Viadel, M.; Rodrigo, R.; Montoliu, C.; Felipo, V. Oral Administration of Sildenafil Restores Learning Ability in Rats with Hyperammonemia and with Portacaval Shunts. Hepatology 2005, 41, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Mehta, R.; Rothke, S.P.; Rademaker, A.W.; Blei, A.T. Fitness to Drive in Patients with Cirrhosis and Portal-Systemic Shunting: A Pilot Study Evaluating Driving Performance. J Hepatol 1994, 21, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Hafeezullah, M.; Hoffmann, R.G.; Varma, R.R.; Franco, J.; Binion, D.G.; Hammeke, T.A.; Saeian, K. Navigation Skill Impairment: Another Dimension of the Driving Difficulties in Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Hepatology 2008, 47, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, E.; Córdoba, J.; Torrens, M.; Torras, X.; Villanueva, C.; Vargas, V.; Guarner, C.; Soriano, G. Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy Is Associated with Falls. Am J Gastroenterol 2011, 106, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, G.; Román, E.; Córdoba, J.; Torrens, M.; Poca, M.; Torras, X.; Villanueva, C.; Gich, I.J.; Vargas, V.; Guarner, C. Cognitive Dysfunction in Cirrhosis Is Associated with Falls: A Prospective Study. Hepatology 2012, 55, 1922–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J. Bone Disorders in Chronic Liver Disease. Hepatology 2007, 46, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeneweg, M.; Moerland, W.; Quero, J.C.; Hop, W.C.; Krabbe, P.F.; Schalm, S.W. Screening of Subclinical Hepatic Encephalopathy. J Hepatol 2000, 32, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poordad, F.F. Review Article: The Burden of Hepatic Encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007, 25 Suppl 1, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gómez, M.; Córdoba, J.; Jover, R.; del Olmo, J.A.; Ramírez, M.; Rey, R.; de Madaria, E.; Montoliu, C.; Nuñez, D.; Flavia, M.; et al. Value of the Critical Flicker Frequency in Patients with Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Hepatology 2007, 45, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhiman, R.K.; Chawla, Y.K. Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Indian J Gastroenterol 2009, 28, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardone, R.; Taylor, A.C.; Höller, Y.; Brigo, F.; Lochner, P.; Trinka, E. Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Review. Neurosci Res 2016, 111, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wein, C.; Koch, H.; Popp, B.; Oehler, G.; Schauder, P. Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy Impairs Fitness to Drive. Hepatology 2004, 39, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Wade, J.B.; Sanyal, A.J. Spectrum of Neurocognitive Impairment in Cirrhosis: Implications for the Assessment of Hepatic Encephalopathy. Hepatology 2009, 50, 2014–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardelli, S.; Gioia, S.; Faccioli, J.; Riggio, O.; Ridola, L. Sarcopenia and Cognitive Impairment in Liver Cirrhosis: A Viewpoint on the Clinical Impact of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. World J Gastroenterol 2019, 25, 5257–5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, R.K.; Kurmi, R.; Thumburu, K.K.; Venkataramarao, S.H.; Agarwal, R.; Duseja, A.; Chawla, Y. Diagnosis and Prognostic Significance of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Cirrhosis of Liver. Dig Dis Sci 2010, 55, 2381–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, K.; Ramezani, A. Regression-Based Normative Formulae for the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status for Older Adults. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2015, 30, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, F.; Montagnese, S.; Ridola, L.; Senzolo, M.; Schiff, S.; De Rui, M.; Pasquale, C.; Nardelli, S.; Pentassuglio, I.; Merkel, C.; et al. The Animal Naming Test: An Easy Tool for the Assessment of Hepatic Encephalopathy. Hepatology 2017, 66, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Heuman, D.M.; Sterling, R.K.; Sanyal, A.J.; Siddiqui, M.; Matherly, S.; Luketic, V.; Stravitz, R.T.; Fuchs, M.; Thacker, L.R.; et al. Validation of EncephalApp, Smartphone-Based Stroop Test, for the Diagnosis of Covert Hepatic Encephalopathy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015, 13, 1828–1835.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, C.; Shaw, J.; Duong, N.; Fagan, A.; McGeorge, S.; Wade, J.B.; Thacker, L.R.; Bajaj, J.S. QuickStroop, a Shortened Version of EncephalApp, Detects Covert Hepatic Encephalopathy With Similar Accuracy Within One Minute. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 21, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montagnese, S.; Schiff, S.; De Rui, M.; Crossey, M.M.E.; Amodio, P.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D. Neuropsychological Tools in Hepatology: A Survival Guide for the Clinician. J Viral Hepat 2012, 19, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodio, P.; Campagna, F.; Olianas, S.; Iannizzi, P.; Mapelli, D.; Penzo, M.; Angeli, P.; Gatta, A. Detection of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: Normalization and Optimization of the Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score. A Neuropsychological and Quantified EEG Study. J Hepatol 2008, 49, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Rojo, A.; Estradas, J.; Hernández-Ramos, R.; Ponce-de-León, S.; Córdoba, J.; Torre, A. Validation of the Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score (PHES) for Identifying Patients with Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Dig Dis Sci 2011, 56, 3014–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.S.; Yim, S.Y.; Jung, J.Y.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, J.D.; Keum, B.; An, H.; Yim, H.J.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, C.D.; et al. Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score for the Detection of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Korean Patients with Liver Cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012, 27, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-W.; Wang, K.; Yu, Y.-Q.; Wang, H.-B.; Li, Y.-H.; Xu, J.-M. Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score for Diagnosis of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in China. World J Gastroenterol 2013, 19, 8745–8751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.L.; Livingston, R.B.; Smernoff, E.N.; Reese, E.M.; Hafer, D.G.; Harris, J.B. Factor Analysis of the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) in a Large Sample of Patients Suspected of Dementia. Appl Neuropsychol 2010, 17, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Leahy, B.; Corradi, K.; Forchetti, C. Component Structure of the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status in Dementia. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2008, 23, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, C.; Wertheimer, J.C.; Fichtenberg, N.L.; Casey, J.E. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): Clinical Utility in a Traumatic Brain Injury Sample. Clin Neuropsychol 2008, 22, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labenz, C.; Beul, L.; Toenges, G.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Nagel, M.; Sprinzl, M.F.; Nguyen-Tat, M.; Zimmermann, T.; Huber, Y.; Marquardt, J.U.; et al. Validation of the Simplified Animal Naming Test as Primary Screening Tool for the Diagnosis of Covert Hepatic Encephalopathy. Eur J Intern Med 2019, 60, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Taneja, S.; Chopra, M.; Duseja, A.; Dhiman, R.K. Animal Naming Test - a Simple and Accurate Test for Diagnosis of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy and Prediction of Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy. Clin Exp Hepatol 2020, 6, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Li, T.; Lin, C.; Liu, F.; Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Ye, Q. Animal Naming Test for the Assessment of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Asian Cirrhotic Populations. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2021, 45, 101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gairing, S.J.; Schleicher, E.M.; Galle, P.R.; Labenz, C. Prediction and Prevention of the First Episode of Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauridsen, M.M.; Mikkelsen, S.; Svensson, T.; Holm, J.; Klüver, C.; Gram, J.; Vilstrup, H.; Schaffalitzky de Muckadell, O.B. The Continuous Reaction Time Test for Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy Validated by a Randomized Controlled Multi-Modal Intervention-A Pilot Study. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0185412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, S.; Dhiman, R.K.; Khatri, A.; Goyal, S.; Thumbru, K.K.; Agarwal, R.; Duseja, A.; Chawla, Y. Inhibitory Control Test for the Detection of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Cirrhosis of Liver. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2012, 2, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbecker, A.; Weissenborn, K.; Hamidi Shahrezaei, G.; Afshar, K.; Rümke, S.; Barg-Hock, H.; Strassburg, C.P.; Hecker, H.; Tryc, A.B. Comparison of the Most Favoured Methods for the Diagnosis of Hepatic Encephalopathy in Liver Transplantation Candidates. Gut 2013, 62, 1497–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Ingle, M.; Shah, K.; Phadke, A.; Sawant, P. Prospective Comparative Study of Inhibitory Control Test and Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score for Diagnosis and Prognosis of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Cirrhotic Patients in the Indian Subcontinent. J Dig Dis 2015, 16, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Yu, X.-B.; Hu, S.-J.; Bai, F.-H. EncephalApp Stroop App Predicts Poor Sleep Quality in Patients with Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy Due to Hepatitis B-Induced Liver Cirrhosis. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2020, 26, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha-Silva, M.; Neto, F.L.P.; de Araújo, P.S.; Pazinato, L.V.; Greca, R.D.; Secundo, T.M.L.; Imbrizi, M.R.; Monici, L.T.; Sevá-Pereira, T.; Mazo, D.F. EncephalApp Stroop Test Validation for the Screening of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Brazil. Ann Hepatol 2022, 27, 100543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupescu, I.C.; Iacob, S.; Lupescu, I.G.; Pietrareanu, C.; Gheorghe, L. Assessment of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy with Brain MRI and EncephalApp Stroop Test. Maedica (Bucur) 2023, 18, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, E.; Thacker, L.R.; Wade, J.B.; Sterling, R.K.; Stravitz, R.T.; Fuchs, M.; Heuman, D.M.; Bouneva, I.; Sanyal, A.J.; Siddiqui, M.S.; et al. Diagnosis of Covert Hepatic Encephalopathy without Specialized Tests. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, 12, 1384–1389.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharshi, S.; Sharma, B.C.; Sachdeva, S.; Srivastava, S.; Sharma, P. Efficacy of Nutritional Therapy for Patients With Cirrhosis and Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in a Randomized Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016, 14, 454–460.e3, quiz e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauridsen, M.M.; Jepsen, P.; Wernberg, C.W.; Schaffalitzky de Muckadell, O.B.; Bajaj, J.S.; Vilstrup, H. Validation of a Simple Quality-of-Life Score for Identification of Minimal and Prediction of Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy. Hepatol Commun 2020, 4, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Ma, P.; Li, L.; Cao, W.-K. Advances in Psychometric Tests for Screening Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: From Paper-and-Pencil to Computer-Aided Assessment. Turk J Gastroenterol 2019, 30, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, T.J.; Koff, R.S. Feedback EEG in the Detection of Subclinical Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Preliminary Report. Int J Psychophysiol 1989, 8, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodio, P.; Marchetti, P.; Del Piccolo, F.; de Tourtchaninoff, M.; Varghese, P.; Zuliani, C.; Campo, G.; Gatta, A.; Guérit, J.M. Spectral versus Visual EEG Analysis in Mild Hepatic Encephalopathy. Clin Neurophysiol 1999, 110, 1334–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodio, P.; Pellegrini, A.; Ubiali, E.; Mathy, I.; Piccolo, F.D.; Orsato, R.; Gatta, A.; Guerit, J.M. The EEG Assessment of Low-Grade Hepatic Encephalopathy: Comparison of an Artificial Neural Network-Expert System (ANNES) Based Evaluation with Visual EEG Readings and EEG Spectral Analysis. Clin Neurophysiol 2006, 117, 2243–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoli, D.; Guérit, J.M.; Montagnese, S.; de Tourtchaninoff, M.; Minelli, T.; Pellegrini, A.; Del Piccolo, F.; Gatta, A.; Amodio, P. Analysis of EEG Tracings in Frequency and Time Domain in Hepatic Encephalopathy. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2006, 81, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, S.; Casa, M.; Di Caro, V.; Aprile, D.; Spinelli, G.; De Rui, M.; Angeli, P.; Amodio, P.; Montagnese, S. A Low-Cost, User-Friendly Electroencephalographic Recording System for the Assessment of Hepatic Encephalopathy. Hepatology 2016, 63, 1651–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amodio, P.; Gatta, A. Neurophysiological Investigation of Hepatic Encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 2005, 20, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullmann, F.; Hollerbach, S.; Holstege, A.; Schölmerich, J. Subclinical Hepatic Encephalopathy: The Diagnostic Value of Evoked Potentials. J Hepatol 1995, 22, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeneroli, M.L.; Pinelli, G.; Gollini, G.; Penne, A.; Messori, E.; Zani, G.; Ventura, E. Visual Evoked Potential: A Diagnostic Tool for the Assessment of Hepatic Encephalopathy. Gut 1984, 25, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, B.C.; Puri, V.; Sarin, S.K. Critical Flicker Frequency: Diagnostic Tool for Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. J Hepatol 2007, 47, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, B.C.; Sarin, S.K. Critical Flicker Frequency for Diagnosis and Assessment of Recovery from Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Cirrhosis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2010, 9, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lauridsen, M.M.; Jepsen, P.; Vilstrup, H. Critical Flicker Frequency and Continuous Reaction Times for the Diagnosis of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Comparative Study of 154 Patients with Liver Disease. Metab Brain Dis 2011, 26, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.; Shahini, E.; Iannone, A.; Viggiani, M.T.; Corvace, V.; Principi, M.; Di Leo, A. Critical Flicker Frequency Test Predicts Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy and Survival in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis. Dig Liver Dis 2018, 50, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direkze, S.; Jalan, R. Diagnosis and Treatment of Low-Grade Hepatic Encephalopathy. Dig Dis 2015, 33, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Kuroda, H.; Sawara, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Kakisaka, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Suzuki, A.; Onodera, M.; Oikawa, T.; Tei, W. Predictive Biomarkers for Diagnosis of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis: A Preliminary Result in a Single Center Study in Japan. Biomed Res Clin Prac 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiati Kenston, S.S.; Song, X.; Li, Z.; Zhao, J. Mechanistic Insight, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Ammonia-Induced Hepatic Encephalopathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, 34, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoliu, C.; Cauli, O.; Urios, A.; ElMlili, N.; Serra, M.A.; Giner-Duran, R.; González-Lopez, O.; Del Olmo, J.A.; Wassel, A.; Rodrigo, J.M.; et al. 3-Nitro-Tyrosine as a Peripheral Biomarker of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011, 106, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, T.; Elsabaawy, M.; Omar, M.; Afify, M.; Elezawy, H.; Ghanem, S.; Abdelraouf, O.; Rewisha, E.; Shebl, N. Evaluation of Different Diagnostic Modalities of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Cirrhotic Patients: Case-Control Study. Clin Exp Hepatol 2021, 7, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanapirom, K.; Wongwandee, M.; Suksawatamnuay, S.; Thaimai, P.; Siripon, N.; Makhasen, W.; Treeprasertsuk, S.; Komolmit, P. Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score for the Diagnosis of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Thai Cirrhotic Patients. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, C.; Hilsabeck, R.; Kato, A.; Kharbanda, P.; Li, Y.-Y.; Mapelli, D.; Ravdin, L.D.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Stracciari, A.; Weissenborn, K. Neuropsychological Assessment of Hepatic Encephalopathy: ISHEN Practice Guidelines. Liver Int 2009, 29, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilstrup, H.; Amodio, P.; Bajaj, J.; Cordoba, J.; Ferenci, P.; Mullen, K.D.; Weissenborn, K.; Wong, P. Hepatic Encephalopathy in Chronic Liver Disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology 2014, 60, 715–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarter, R.E.; Van Thiel, D.H.; Arria, A.M.; Carra, J.; Moss, H. Impact of Cirrhosis on the Neuropsychological Test Performance of Alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1988, 12, 619–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrell, J.H.; Zolnikov, B.J.; Sharma, A.; Jinnai, I. Cognitive Impairment in People Diagnosed with End-Stage Liver Disease Evaluated for Liver Transplantation. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006, 60, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louissaint, J.; Deutsch-Link, S.; Tapper, E.B. Changing Epidemiology of Cirrhosis and Hepatic Encephalopathy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 20, S1–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauridsen, M.M.; Grønbæk, H.; Næser, E.B.; Leth, S.T.; Vilstrup, H. Gender and Age Effects on the Continuous Reaction Times Method in Volunteers and Patients with Cirrhosis. Metab Brain Dis 2012, 27, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, V.B.; Surude, R.G.; Sonthalia, N.; Zanwar, V.; Jain, S.; Contractor, Q.; Rathi, P.M. Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Indians: Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score and Inhibitory Control Test for Diagnosis and Rifaximin or Lactulose for Its Reversal. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2019, 7, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Saeian, K.; Verber, M.D.; Hischke, D.; Hoffmann, R.G.; Franco, J.; Varma, R.R.; Rao, S.M. Inhibitory Control Test Is a Simple Method to Diagnose Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy and Predict Development of Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol 2007, 102, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Hafeezullah, M.; Franco, J.; Varma, R.R.; Hoffmann, R.G.; Knox, J.F.; Hischke, D.; Hammeke, T.A.; Pinkerton, S.D.; Saeian, K. Inhibitory Control Test for the Diagnosis of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 1591–1600.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amodio, P.; Ridola, L.; Schiff, S.; Montagnese, S.; Pasquale, C.; Nardelli, S.; Pentassuglio, I.; Trezza, M.; Marzano, C.; Flaiban, C.; et al. Improving the Inhibitory Control Task to Detect Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 510–518, 518.e1-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Thacker, L.R.; Heuman, D.M.; Fuchs, M.; Sterling, R.K.; Sanyal, A.J.; Puri, P.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Stravitz, R.T.; Bouneva, I.; et al. The Stroop Smartphone Application Is a Short and Valid Method to Screen for Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Hepatology 2013, 58, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allampati, S.; Duarte-Rojo, A.; Thacker, L.R.; Patidar, K.R.; White, M.B.; Klair, J.S.; John, B.; Heuman, D.M.; Wade, J.B.; Flud, C.; et al. Diagnosis of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy Using Stroop EncephalApp: A Multicenter US-Based, Norm-Based Study. Am J Gastroenterol 2016, 111, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagalingam, G.; Park, D.; Badal, B.D.; Fagan, A.; Thacker, L.R.; Bajaj, J.S. QuickStroop Predicts Time to Development of Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy and Related Hospitalizations in Patients With Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024, 22, 899–901.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodio, P.; Del Piccolo, F.; Marchetti, P.; Angeli, P.; Iemmolo, R.; Caregaro, L.; Merkel, C.; Gerunda, G.; Gatta, A. Clinical Features and Survivial of Cirrhotic Patients with Subclinical Cognitive Alterations Detected by the Number Connection Test and Computerized Psychometric Tests. Hepatology 1999, 29, 1662–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodio, P.; Marchetti, P.; Del Piccolo, F.; Rizzo, C.; Iemmolo, R.M.; Caregaro, L.; Gerunda, G.; Gatta, A. Study on the Sternberg Paradigm in Cirrhotic Patients without Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 1998, 13, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, P.W. The EEG in Metabolic Encephalopathy and Coma. J Clin Neurophysiol 2004, 21, 307–318. [Google Scholar]

- Götz, T.; Huonker, R.; Kranczioch, C.; Reuken, P.; Witte, O.W.; Günther, A.; Debener, S. Impaired Evoked and Resting-State Brain Oscillations in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis as Revealed by Magnetoencephalography. Neuroimage Clin 2013, 2, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PARSONS-SMITH, B.G.; SUMMERSKILL, W.H.; DAWSON, A.M.; SHERLOCK, S. The Electroencephalograph in Liver Disease. Lancet 1957, 273, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerit, J.-M.; Amantini, A.; Fischer, C.; Kaplan, P.W.; Mecarelli, O.; Schnitzler, A.; Ubiali, E.; Amodio, P. Neurophysiological Investigations of Hepatic Encephalopathy: ISHEN Practice Guidelines. Liver Int 2009, 29, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amodio, P.; Del Piccolo, F.; Pettenò, E.; Mapelli, D.; Angeli, P.; Iemmolo, R.; Muraca, M.; Musto, C.; Gerunda, G.; Rizzo, C.; et al. Prevalence and Prognostic Value of Quantified Electroencephalogram (EEG) Alterations in Cirrhotic Patients. J Hepatol 2001, 35, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, P.; D’Avanzo, C.; Orsato, R.; Montagnese, S.; Schiff, S.; Kaplan, P.W.; Piccione, F.; Merkel, C.; Gatta, A.; Sparacino, G.; et al. Electroencephalography in Patients with Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1680–1689.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Westover, M.B.; Zhang, R. A Neural Mass Model for Disturbance of Alpha Rhythm in the Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Mol Cell Neurosci 2024, 128, 103918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba, J.; Raguer, N.; Flavià, M.; Vargas, V.; Jacas, C.; Alonso, J.; Rovira, A. T2 Hyperintensity along the Cortico-Spinal Tract in Cirrhosis Relates to Functional Abnormalities. Hepatology 2003, 38, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oria, M.; Raguer, N.; Chatauret, N.; Bartolí, R.; Odena, G.; Planas, R.; Córdoba, J. Functional Abnormalities of the Motor Tract in the Rat after Portocaval Anastomosis and after Carbon Tetrachloride Induction of Cirrhosis. Metab Brain Dis 2006, 21, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandford, N.L.; Saul, R.E. Assessment of Hepatic Encephalopathy with Visual Evoked Potentials Compared with Conventional Methods. Hepatology 1988, 8, 1094–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, N.; Bhatia, M.; Joshi, Y.K.; Garg, P.K.; Dwivedi, S.N.; Tandon, R.K. Electrophysiological and Neuropsychological Tests for the Diagnosis of Subclinical Hepatic Encephalopathy and Prediction of Overt Encephalopathy. Liver 2002, 22, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.G.; Rowan, M.J.; MacMathuna, P.; Keeling, P.W.; Weir, D.G.; Feely, J. The Auditory P300 Event-Related Potential: An Objective Marker of the Encephalopathy of Chronic Liver Disease. Hepatology 1990, 12, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curran, S.; Wattis, J. Critical Flicker Fusion Threshold: A Potentially Useful Measure for the Early Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease. Hum Psychopharmacol 2000, 15, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gómez, M.; Boza, F.; García-Valdecasas, M.S.; García, E.; Aguilar-Reina, J. Subclinical Hepatic Encephalopathy Predicts the Development of Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol 2001, 96, 2718–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jover, R.; Compañy, L.; Gutiérrez, A.; Lorente, M.; Zapater, P.; Poveda, M.J.; Such, J.; Pascual, S.; Palazón, J.M.; Carnicer, F.; et al. Clinical Significance of Extrapyramidal Signs in Patients with Cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2005, 42, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumral, D.; Qayyum, R.; Roseff, S.; Sterling, R.K.; Siddiqui, M.S. Adherence to Recommended Inpatient Hepatic Encephalopathy Workup. J Hosp Med 2019, 14, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauli, O.; Rodrigo, R.; Llansola, M.; Montoliu, C.; Monfort, P.; Piedrafita, B.; El Mlili, N.; Boix, J.; Agustí, A.; Felipo, V. Glutamatergic and Gabaergic Neurotransmission and Neuronal Circuits in Hepatic Encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 2009, 24, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, E.A.; Mohammed, M.N.; Sayyed, M.M.; El-Khayal, A.E.-S.; Ahmed, M.A.S. 3-Nitro-Tyrosine as a Biomarker of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis. The Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine 2018, 72, 5647+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genesca, J.; Gonzalez, A.; Segura, R.; Catalan, R.; Marti, R.; Varela, E.; Cadelina, G.; Martinez, M.; Lopez-Talavera, J.C.; Esteban, R.; et al. Interleukin-6, Nitric Oxide, and the Clinical and Hemodynamic Alterations of Patients with Liver Cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 1999, 94, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, G.I.; Christiansen, M.; Møller, K.; Clemmesen, J.O.; Larsen, F.S.; Knudsen, G.M. S-100b and Neuron-Specific Enolase in Patients with Fulminant Hepatic Failure. Liver Transpl 2001, 7, 964–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero, J.; Jordano, Q.; Lee, W.M.; Blei, A.T. Serum Protein S-100b in Acute Liver Failure: Results of the US Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Liver Transpl 2003, 9, 887–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe-Harima, Y.; Terai, S.; Segawa, M.; Uchida, K.; Yamasaki, T.; Sakaida, I. Serum S100b (Astrocyte-Specific Protein) Is a Useful Marker of Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Fulminant Hepatitis. Liver Int 2008, 28, 146–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte-Rojo, A.; Ruiz-Margáin, A.; Macias-Rodriguez, R.U.; Cubero, F.J.; Estradas-Trujillo, J.; Muñoz-Fuentes, R.M.; Torre, A. Clinical Scenarios for the Use of S100β as a Marker of Hepatic Encephalopathy. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22, 4397–4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiltfang, J.; Nolte, W.; Otto, M.; Wildberg, J.; Bahn, E.; Figulla, H.R.; Pralle, L.; Hartmann, H.; Rüther, E.; Ramadori, G. Elevated Serum Levels of Astroglial S100beta in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis Indicate Early and Subclinical Portal-Systemic Encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 1999, 14, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guevara, M.; Baccaro, M.E.; Torre, A.; Gómez-Ansón, B.; Ríos, J.; Torres, F.; Rami, L.; Monté-Rubio, G.C.; Martín-Llahí, M.; Arroyo, V.; et al. Hyponatremia Is a Risk Factor of Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Prospective Study with Time-Dependent Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2009, 104, 1382–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, P.; Watson, H.; Andersen, P.K.; Vilstrup, H. Diabetes as a Risk Factor for Hepatic Encephalopathy in Cirrhosis Patients. J Hepatol 2015, 63, 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudyal, N.S.; Chaudhary, S.; Kc, S.; Paudel, B.N.; Basnet, B.K.; Mandal, A.; Kafle, P.; Chaulagai, B.; Mojahedi, A.; Paudel, M.S.; et al. Precipitating Factors and Treatment Outcomes of Hepatic Encephalopathy in Liver Cirrhosis. Cureus 2019, 11, e4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie, M.S.; Shousha, H.I.; Abdelrazek, W.; Hassany, M.; Dabees, H.; Abdelghafour, R.; Aboganob, W. mosaad; Said, M. Prediction of Hepatic Decompensation and Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy in Patients with Hepatitis C-Related Liver Cirrhosis: A Cohort Study. Egyptian Liver Journal 2023, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praktiknjo, M.; Simón-Talero, M.; Römer, J.; Roccarina, D.; Martínez, J.; Lampichler, K.; Baiges, A.; Low, G.; Llop, E.; Maurer, M.H.; et al. Total Area of Spontaneous Portosystemic Shunts Independently Predicts Hepatic Encephalopathy and Mortality in Liver Cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2020, 72, 1140–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Gómez, A.; Ampuero, J.; Rojas, Á.; Gallego-Durán, R.; Muñoz-Hernández, R.; Rico, M.C.; Millán, R.; García-Lozano, R.; Francés, R.; Soriano, G.; et al. Development and Validation of a Clinical-Genetic Risk Score to Predict Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients With Liver Cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2021, 116, 1238–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Z.; Guo, X. Covered versus Bare Stents for Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2017, 10, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnese, S.; Balistreri, E.; Schiff, S.; De Rui, M.; Angeli, P.; Zanus, G.; Cillo, U.; Bombonato, G.; Bolognesi, M.; Sacerdoti, D.; et al. Covert Hepatic Encephalopathy: Agreement and Predictive Validity of Different Indices. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20, 15756–15762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisarek, W. Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy - Diagnosis and Treatment. Prz Gastroenterol 2021, 16, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Etemadian, A.; Hafeezullah, M.; Saeian, K. Testing for Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in the United States: An AASLD Survey. Hepatology 2007, 45, 833–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, C.F.; Amodio, P.; Bajaj, J.S.; Dhiman, R.K.; Montagnese, S.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D.; Vilstrup, H.; Jalan, R. Hepatic Encephalopathy: Novel Insights into Classification, Pathophysiology and Therapy. J Hepatol 2020, 73, 1526–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patidar, K.R.; Bajaj, J.S. Covert and Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy: Diagnosis and Management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015, 13, 2048–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, N.M. Review Article: The Current Pharmacological Therapies for Hepatic Encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007, 25 Suppl 1, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.Y.; Alonso, M.; Stanger, L.C. Lactitol and Lactulose for the Treatment of Subclinical Hepatic Encephalopathy in Cirrhotic Patients. A Randomised, Cross-over Study. J Hepatol 1989, 8, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsmans, Y.; Solbreux, P.M.; Daenens, C.; Desager, J.P.; Geubel, A.P. Lactulose Improves Psychometric Testing in Cirrhotic Patients with Subclinical Encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1997, 11, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, A.; Sakai, T.; Sato, S.; Imai, F.; Ohto, M.; Arakawa, Y.; Toda, G.; Kobayashi, K.; Muto, Y.; Tsujii, T.; et al. Clinical Efficacy of Lactulose in Cirrhotic Patients with and without Subclinical Hepatic Encephalopathy. Hepatology 1997, 26, 1410–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, R.K.; Sawhney, M.S.; Chawla, Y.K.; Das, G.; Ram, S.; Dilawari, J.B. Efficacy of Lactulose in Cirrhotic Patients with Subclinical Hepatic Encephalopathy. Dig Dis Sci 2000, 45, 1549–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Dhiman, R.K.; Duseja, A.; Chawla, Y.K.; Sharma, A.; Agarwal, R. Lactulose Improves Cognitive Functions and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Cirrhosis Who Have Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Hepatology 2007, 45, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Gillevet, P.M.; Patel, N.R.; Ahluwalia, V.; Ridlon, J.M.; Kettenmann, B.; Schubert, C.M.; Sikaroodi, M.; Heuman, D.M.; Crossey, M.M.E.; et al. A Longitudinal Systems Biology Analysis of Lactulose Withdrawal in Hepatic Encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 2012, 27, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, B.C.; Agrawal, A.; Sarin, S.K. Primary Prophylaxis of Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Cirrhosis: An Open Labeled Randomized Controlled Trial of Lactulose versus No Lactulose. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012, 27, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziada, D.H.; Soliman, H.H.; El Yamany, S.A.; Hamisa, M.F.; Hasan, A.M. Can Lactobacillus Acidophilus Improve Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy? A Neurometabolite Study Using Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Arab J Gastroenterol 2013, 14, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap Mouli, V.; Benjamin, J.; Bhushan Singh, M.; Mani, K.; Garg, S.K.; Saraya, A.; Joshi, Y.K. Effect of Probiotic VSL#3 in the Treatment of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Non-Inferiority Randomized Controlled Trial. Hepatol Res 2015, 45, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, S.S.; Goyal, O.; Parker, R.A.; Kishore, H.; Sood, A. Rifaximin vs. Lactulose in Treatment of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Liver Int 2016, 36, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Bajaj, J.S.; Wang, J.B.; Shang, J.; Zhou, X.M.; Guo, X.L.; Zhu, X.; Meng, L.N.; Jiang, H.X.; Mi, Y.Q.; et al. Lactulose Improves Cognition, Quality of Life, and Gut Microbiota in Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Multicenter, Randomized Controlled Trial. J Dig Dis 2019, 20, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-W.; Ma, W.-J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X.-H.; Xue, Y.-F.; Guan, J.; Chen, X. Comparison of the Effects of Probiotics, Rifaximin, and Lactulose in the Treatment of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy and Gut Microbiota. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1091167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, S.S.; Goyal, O.; Mishra, B.P.; Sood, A.; Chhina, R.S.; Soni, R.K. Rifaximin Improves Psychometric Performance and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy (the RIME Trial). Am J Gastroenterol 2011, 106, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, M.-P.; Gallego, J.-J.; Fiorillo, A.; Casanova-Ferrer, F.; Giménez-Garzó, C.; Escudero-García, D.; Tosca, J.; Ríos, M.-P.; Montón, C.; Durbán, L.; et al. Metabolic Syndrome Is Associated with Poor Response to Rifaximin in Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Heuman, D.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Hylemon, P.B.; Sterling, R.K.; Stravitz, R.T.; Fuchs, M.; Ridlon, J.M.; Daita, K.; Monteith, P.; et al. Modulation of the Metabiome by Rifaximin in Patients with Cirrhosis and Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. PLoS One 2013, 8, e60042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahluwalia, V.; Wade, J.B.; Heuman, D.M.; Hammeke, T.A.; Sanyal, A.J.; Sterling, R.K.; Stravitz, R.T.; Luketic, V.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Puri, P.; et al. Enhancement of Functional Connectivity, Working Memory and Inhibitory Control on Multi-Modal Brain MR Imaging with Rifaximin in Cirrhosis: Implications for the Gut-Liver-Brain Axis. Metab Brain Dis 2014, 29, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Cao, B.; Tian, Q. Effects of SIBO and Rifaximin Therapy on MHE Caused by Hepatic Cirrhosis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015, 8, 2954–2957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goyal, O.; Sidhu, S.S.; Kishore, H. Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Cirrhosis- How Long to Treat? Ann Hepatol 2017, 16, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakulin, I.G.; Ivanova, K.N.; Eremina, E.Y.; Marchenko, N.V. Comparative Analysis of the Efficacy of Different Regimens of 12 Months Rifaximin-Alfa Therapy in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis and Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, A.; Gallego, J.J.; Casanova-Ferrer, F.; Urios, A.; Ballester, M.-P.; San Miguel, T.; Megías, J.; Kosenko, E.; Tosca, J.; Rios, M.-P.; et al. Neurofilament Light Chain Protein in Plasma and Extracellular Vesicles Is Associated with Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy and Responses to Rifaximin Treatment in Cirrhotic Patients. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova-Ferrer, F.; Gallego, J.-J.; Fiorillo, A.; Urios, A.; Ríos, M.-P.; León, J.L.; Ballester, M.-P.; Escudero-García, D.; Kosenko, E.; Belloch, V.; et al. Improved Cognition after Rifaximin Treatment Is Associated with Changes in Intra- and Inter-Brain Network Functional Connectivity. J Transl Med 2024, 22, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egberts, E.H.; Schomerus, H.; Hamster, W.; Jürgens, P. Branched Chain Amino Acids in the Treatment of Latent Portosystemic Encephalopathy. A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Crossover Study. Gastroenterology 1985, 88, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plauth, M.; Egberts, E.H.; Hamster, W.; Török, M.; Müller, P.H.; Brand, O.; Fürst, P.; Dölle, W. Long-Term Treatment of Latent Portosystemic Encephalopathy with Branched-Chain Amino Acids. A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Crossover Study. J Hepatol 1993, 17, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesini, G.; Bianchi, G.; Merli, M.; Amodio, P.; Panella, C.; Loguercio, C.; Rossi Fanelli, F.; Abbiati, R. Nutritional Supplementation with Branched-Chain Amino Acids in Advanced Cirrhosis: A Double-Blind, Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology 2003, 124, 1792–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Les, I.; Doval, E.; García-Martínez, R.; Planas, M.; Cárdenas, G.; Gómez, P.; Flavià, M.; Jacas, C.; Mínguez, B.; Vergara, M.; et al. Effects of Branched-Chain Amino Acids Supplementation in Patients with Cirrhosis and a Previous Episode of Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Randomized Study. Am J Gastroenterol 2011, 106, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaguarnera, M.; Greco, F.; Barone, G.; Gargante, M.P.; Malaguarnera, M.; Toscano, M.A. Bifidobacterium Longum with Fructo-Oligosaccharide (FOS) Treatment in Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Dig Dis Sci 2007, 52, 3259–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Saeian, K.; Christensen, K.M.; Hafeezullah, M.; Varma, R.R.; Franco, J.; Pleuss, J.A.; Krakower, G.; Hoffmann, R.G.; Binion, D.G. Probiotic Yogurt for the Treatment of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol 2008, 103, 1707–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, B.C.; Puri, V.; Sarin, S.K. An Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial of Lactulose and Probiotics in the Treatment of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008, 20, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, V.V.; Sharma, B.C.; Sharma, P.; Sarin, S.K. A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Lactulose, Probiotics, and L-Ornithine L-Aspartate in Treatment of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011, 23, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Heuman, D.M.; Hylemon, P.B.; Sanyal, A.J.; Puri, P.; Sterling, R.K.; Luketic, V.; Stravitz, R.T.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Fuchs, M.; et al. Randomised Clinical Trial: Lactobacillus GG Modulates Gut Microbiome, Metabolome and Endotoxemia in Patients with Cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014, 39, 1113–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunia, M.K.; Sharma, B.C.; Sharma, P.; Sachdeva, S.; Srivastava, S. Probiotics Prevent Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, 12, 1003–1008.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Pant, S.; Misra, S.; Dwivedi, M.; Misra, A.; Narang, S.; Tewari, R.; Bhadoria, A.S. Effect of Rifaximin, Probiotics, and l-Ornithine l-Aspartate on Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2014, 20, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Chen, J.; Xia, J.; Wang, B.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Ling, Z. Role of Probiotics in the Treatment of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with HBV-Induced Liver Cirrhosis. J Int Med Res 2018, 46, 3596–3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndraha, S.; Hasan, I.; Simadibrata, M. The Effect of L-Ornithine L-Aspartate and Branch Chain Amino Acids on Encephalopathy and Nutritional Status in Liver Cirrhosis with Malnutrition. Acta Med Indones 2011, 43, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, A.; Tanaka, H.; Kawaguchi, T.; Kanazawa, H.; Iwasa, M.; Sakaida, I.; Moriwaki, H.; Murawaki, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Okita, K. Nutritional Management Contributes to Improvement in Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy and Quality of Life in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis: A Preliminary, Prospective, Open-Label Study. Hepatol Res 2013, 43, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, R.; Ahuja, C.K.; Agrawal, S.; Kalra, N.; Duseja, A.; Khandelwal, N.; Chawla, Y.; Dhiman, R.K. Reversal of Low-Grade Cerebral Edema After Lactulose/Rifaximin Therapy in Patients with Cirrhosis and Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2015, 6, e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Li, F. Clinical Study of Probiotics Combined with Lactulose for Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy Treatment. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 35, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaguarnera, M.; Gargante, M.P.; Cristaldi, E.; Vacante, M.; Risino, C.; Cammalleri, L.; Pennisi, G.; Rampello, L. Acetyl-L-Carnitine Treatment in Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Dig Dis Sci 2008, 53, 3018–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Gupta, A.; Chandra, M.; Koowar, S. Role of Helicobacter Pylori Infection in the Pathogenesis of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy and Effect of Its Eradication. Indian J Gastroenterol 2011, 30, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkard, T.; Biedermann, A.; Herold, C.; Dietlein, M.; Rauch, M.; Diefenbach, M. Treatment with a Potassium-Iron-Phosphate-Citrate Complex Improves PSE Scores and Quality of Life in Patients with Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Multicenter, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013, 25, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janyajirawong, R.; Vilaichone, R.-K.; Sethasine, S. Efficacy of Zinc Supplement in Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Prospective, Randomized Controlled Study (Zinc-MHE Trial). Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2021, 22, 2879–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.C.; Maharshi, S.; Sachdeva, S.; Mahajan, B.; Sharma, A.; Bara, S.; Srivastava, S.; Kumar, A.; Dalal, A.; Sonika, U. Nutritional Therapy for Persistent Cognitive Impairment after Resolution of Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 38, 1917–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, M.; Campollo, O.; Coté, C. Effect of Lactulose on the Metabolism of Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Hepatology 1990, 12, 1251–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, M.; Berthier, J.M.; Lewis, H.; Mata, J.M.; Sierra, J.G.; García-Ramos, G.; Ramírez Acosta, J.; Dehesa, M. Lactose Enemas plus Placebo Tablets vs. Neomycin Tablets plus Starch Enemas in Acute Portal Systemic Encephalopathy. A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Study. Gastroenterology 1981, 81, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, M.; Toledo, H.; Perez, F.; Vargas, F.; Gil, S.; Garcia-Ramos, G.; Ravelli, G.P.; Guevara, L. Lactitol, a Second-Generation Disaccharide for Treatment of Chronic Portal-Systemic Encephalopathy. A Double-Blind, Crossover, Randomized Clinical Trial. Dig Dis Sci 1987, 32, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gluud, L.L.; Vilstrup, H.; Morgan, M.Y. Non-Absorbable Disaccharides versus Placebo/No Intervention and Lactulose versus Lactitol for the Prevention and Treatment of Hepatic Encephalopathy in People with Cirrhosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016, 4, CD003044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, R.S.; Singal, A.G.; Cuthbert, J.A.; Rockey, D.C. Lactulose vs Polyethylene Glycol 3350--Electrolyte Solution for Treatment of Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy: The HELP Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014, 174, 1727–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal-Cevallos, P.; Chávez-Tapia, N.C.; Uribe, M. Current Approaches to Hepatic Encephalopathy. Ann Hepatol 2022, 27, 100757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swales, J.D.; Wrong, O.M. Ammonia Production in the Human Colon. N Engl J Med 1971, 284, 216–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglio, F.; Valpiani, D.; Rossellini, S.R.; Ferrieri, A. Rifaximin, a Non-Absorbable Rifamycin, for the Treatment of Hepatic Encephalopathy. A Double-Blind, Randomised Trial. Curr Med Res Opin 1997, 13, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, Y.H.; Lee, K.S.; Han, K.H.; Song, K.H.; Kim, M.H.; Moon, B.S.; Ahn, S.H.; Lee, S.J.; Park, H.J.; Lee, D.K.; et al. Comparison of Rifaximin and Lactulose for the Treatment of Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Prospective Randomized Study. Yonsei Med J 2005, 46, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.C.; Sharma, P.; Lunia, M.K.; Srivastava, S.; Goyal, R.; Sarin, S.K. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Trial Comparing Rifaximin plus Lactulose with Lactulose Alone in Treatment of Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol 2013, 108, 1458–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltawil, K.M.; Laryea, M.; Peltekian, K.; Molinari, M. Rifaximin vs. Conventional Oral Therapy for Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Meta-Analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2012, 18, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poo, J.; Cervera, E.; De Hoyos, A.; Gil, S.; Cadena, M.; Uribe, M. Benzoato de Sodio. Fundamentos Para Su Uso Clinico En Hepatologia. Rev Invest Clin 1990, 42, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Uribe, M.; Bosques, F.; Marín, E.; Cervera, E.; Gil, S.; Luis Poo, J.; Garcia Compeán, D.; Santoyo, R.; Huerta, E.; García-Ramos, G.; et al. [Sodium benzoate in portal-systemic-encephalopathy-induced blood ammonia normalization and clinical improvement. Interim report of a double-blind multicenter trial]. Rev Invest Clin 1990, 42, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, R.S.; Safadi, R.; Thabut, D.; Bhamidimarri, K.R.; Pyrsopoulos, N.; Potthoff, A.; Bukofzer, S.; Bajaj, J.S. Efficacy and Safety of Ornithine Phenylacetate for Treating Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy in a Randomized Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 19, 2626–2635.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura-Cots, M.; Arranz, J.A.; Simón-Talero, M.; Torrens, M.; Blanco, A.; Riudor, E.; Fuentes, I.; Suñé, P.; Soriano, G.; Córdoba, J. Safety of Ornithine Phenylacetate in Cirrhotic Decompensated Patients: An Open-Label, Dose-Escalating, Single-Cohort Study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013, 47, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poo, J.L.; Góngora, J.; Sánchez-Avila, F.; Aguilar-Castillo, S.; García-Ramos, G.; Fernández-Zertuche, M.; Rodríguez-Fragoso, L.; Uribe, M. Efficacy of Oral L-Ornithine-L-Aspartate in Cirrhotic Patients with Hyperammonemic Hepatic Encephalopathy. Results of a Randomized, Lactulose-Controlled Study. Ann Hepatol 2006, 5, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, E.T.; Stokes, C.S.; Sidhu, S.S.; Vilstrup, H.; Gluud, L.L.; Morgan, M.Y. L-Ornithine L-Aspartate for Prevention and Treatment of Hepatic Encephalopathy in People with Cirrhosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018, 5, CD012410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.C.; Singh, J.; Srivastava, S.; Sangam, A.; Mantri, A.K.; Trehanpati, N.; Sarin, S.K. Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Lactulose plus Albumin versus Lactulose Alone for Treatment of Hepatic Encephalopathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 32, 1234–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Flores, R.; Morán-Villota, S.; Cervantes-Barragán, L.; López-Macias, C.; Uribe, M. Manipulation of Microbiota with Probiotics as an Alternative for Treatment of Hepatic Encephalopathy. Nutrition 2020, 73, 110693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamirano-Barrera, A.; Uribe, M.; Chávez-Tapia, N.C.; Nuño-Lámbarri, N. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in the Pathology and Prevention of Liver Disease. J Nutr Biochem 2018, 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, R.; McGee, R.G.; Riordan, S.M.; Webster, A.C. Probiotics for People with Hepatic Encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017, 2, CD008716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Tapia, N.C.; González-Rodríguez, L.; Jeong, M.; López-Ramírez, Y.; Barbero-Becerra, V.; Juárez-Hernández, E.; Romero-Flores, J.L.; Arrese, M.; Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Uribe, M. Current Evidence on the Use of Probiotics in Liver Diseases. Journal of Functional Foods 2015, 17, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Shukla, A.; Mehboob, S.; Guha, S. Meta-Analysis: The Effects of Gut Flora Modulation Using Prebiotics, Probiotics and Synbiotics on Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011, 33, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe, M.; Dibildox, M.; Malpica, S.; Guillermo, E.; Villallobos, A.; Nieto, L.; Vargas, F.; Garcia Ramos, G. Beneficial Effect of Vegetable Protein Diet Supplemented with Psyllium Plantago in Patients with Hepatic Encephalopathy and Diabetes Mellitus. Gastroenterology 1985, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amodio, P.; Bemeur, C.; Butterworth, R.; Cordoba, J.; Kato, A.; Montagnese, S.; Uribe, M.; Vilstrup, H.; Morgan, M.Y. The Nutritional Management of Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Cirrhosis: International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism Consensus. Hepatology 2013, 58, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laleman, W.; Simon-Talero, M.; Maleux, G.; Perez, M.; Ameloot, K.; Soriano, G.; Villalba, J.; Garcia-Pagan, J.-C.; Barrufet, M.; Jalan, R.; et al. Embolization of Large Spontaneous Portosystemic Shunts for Refractory Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Multicenter Survey on Safety and Efficacy. Hepatology 2013, 57, 2448–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Kim, K.W.; Han, S.; Lee, J.; Lim, Y.-S. Improvement in Survival Associated with Embolisation of Spontaneous Portosystemic Shunt in Patients with Recurrent Hepatic Encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014, 39, 1418–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Kassam, Z.; Fagan, A.; Gavis, E.A.; Liu, E.; Cox, I.J.; Kheradman, R.; Heuman, D.; Wang, J.; Gurry, T.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplant from a Rational Stool Donor Improves Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Hepatology 2017, 66, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, M.; Kimer, N.; Bendtsen, F.; Petersen, A.M. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Systematic Review. Scand J Gastroenterol 2021, 56, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Tapia, N.C.; Cesar-Arce, A.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T.; Villegas-López, F.A.; Méndez-Sanchez, N.; Uribe, M. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Use of Oral Zinc in the Treatment of Hepatic Encephalopathy. Nutr J 2013, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.C.; Sharma, P.; Agrawal, A.; Sarin, S.K. Secondary Prophylaxis of Hepatic Encephalopathy: An Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial of Lactulose versus Placebo. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 885–891, 891.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Agrawal, A.; Sharma, B.C.; Sarin, S.K. Prophylaxis of Hepatic Encephalopathy in Acute Variceal Bleed: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Lactulose versus No Lactulose. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011, 26, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, K.D.; Sanyal, A.J.; Bass, N.M.; Poordad, F.F.; Sheikh, M.Y.; Frederick, R.T.; Bortey, E.; Forbes, W.P. Rifaximin Is Safe and Well Tolerated for Long-Term Maintenance of Remission from Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, 12, 1390–1397.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caraceni, P.; Riggio, O.; Angeli, P.; Alessandria, C.; Neri, S.; Foschi, F.G.; Levantesi, F.; Airoldi, A.; Boccia, S.; Svegliati-Baroni, G.; et al. Long-Term Albumin Administration in Decompensated Cirrhosis (ANSWER): An Open-Label Randomised Trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 2417–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietemann, J.L.; Reimund, J.M.; Diniz, R.L.; Reis, M.J.; Baumann, R.; Neugroschl, C.; Von Söhsten, S.; Warter, J.M. High Signal in the Adenohypophysis on T1-Weighted Images Presumably Due to Manganese Deposits in Patients on Long-Term Parenteral Nutrition. Neuroradiology 1998, 40, 793–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.-H.; Hwang, S.; Jung, B.-H.; Park, Y.-H.; Park, C.-S.; Namgoong, J.-M.; Song, G.-W.; Jung, D.-H.; Ahn, C.-S.; Kim, K.-H.; et al. Post-Transplant Assessment of Consciousness in Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure Patients Undergoing Liver Transplantation Using Bispectral Index Monitoring. Transplant Proc 2013, 45, 3069–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Lee, S.-G.; Park, J.-I.; Song, G.-W.; Ryu, J.-H.; Jung, D.-H.; Hwang, G.-S.; Jeong, S.-M.; Song, J.-G.; Hong, S.-K.; et al. Continuous Peritransplant Assessment of Consciousness Using Bispectral Index Monitoring for Patients with Fulminant Hepatic Failure Undergoing Urgent Liver Transplantation. Clin Transplant 2010, 24, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Kim, G.S.; Ko, J.S.; Gwak, M.S.; Lee, S.-K.; Son, M.G. Factors Associated with Consciousness Recovery Time after Liver Transplantation in Recipients with Hepatic Encephalopathy. Transplant Proc 2014, 46, 712–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, T.-L.; Wang, C.-C. Conscious Recovery Response in Post-Hepatic Transplant as a Function of Time-Related Acute Hepatic Encephalopathy. Transplant Proc 2012, 44, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotil, E.U.; Gottstein, J.; Ayala, E.; Randolph, C.; Blei, A.T. Impact of Preoperative Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy on Neurocognitive Function after Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl 2009, 15, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.; Young, G.B.; Marotta, P. Perioperative Neurological Complications after Liver Transplantation Are Best Predicted by Pre-Transplant Hepatic Encephalopathy. Neurocrit Care 2008, 8, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, J.I.; Bilbao, J.I.; Diaz, M.L.; Alegre, F.; Inarrairaegui, M.; Pardo, F.; Quiroga, J. Hepatic Encephalopathy after Liver Transplantation in a Patient with a Normally Functioning Graft: Treatment with Embolization of Portosystemic Collaterals. Liver Transpl 2009, 15, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saritaş, S.; Tarlaci, S.; Bulbuloglu, S.; Guneş, H. Investigation of Post-Transplant Mental Well-Being in Liver Transplant Recipients with Hepatic Encephalopathy. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, S.; Umapathy, S.; Dhiman, R.K. Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy Impairs Quality of Life. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2015, 5, S42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeegen, R.; Drinkwater, J.E.; Dawson, A.M. Method for Measuring Cerebral Dysfunction in Patients with Liver Disease. Br Med J 1970, 2, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Hepatic Encephalopathy. J Hepatol 2022, 77, 807–824. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Dhiman, R.K.; Saraswat, V.A.; Verma, M.; Naik, S.R. Prevalence and Natural History of Subclinical Hepatic Encephalopathy in Cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001, 16, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesini, G.; Bianchi, G.; Amodio, P.; Salerno, F.; Merli, M.; Panella, C.; Loguercio, C.; Apolone, G.; Niero, M.; Abbiati, R. Factors Associated with Poor Health-Related Quality of Life of Patients with Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2001, 120, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Boparai, N.; Price, L.L.; Kiwi, M.L.; McCormick, M.; Guyatt, G. Health-Related Quality of Life in Chronic Liver Disease: The Impact of Type and Severity of Disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2001, 96, 2199–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labenz, C.; Baron, J.S.; Toenges, G.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Nagel, M.; Sprinzl, M.F.; Nguyen-Tat, M.; Zimmermann, T.; Huber, Y.; Marquardt, J.U.; et al. Prospective Evaluation of the Impact of Covert Hepatic Encephalopathy on Quality of Life and Sleep in Cirrhotic Patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018, 48, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardelli, S.; Pentassuglio, I.; Pasquale, C.; Ridola, L.; Moscucci, F.; Merli, M.; Mina, C.; Marianetti, M.; Fratino, M.; Izzo, C.; et al. Depression, Anxiety and Alexithymia Symptoms Are Major Determinants of Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) in Cirrhotic Patients. Metab Brain Dis 2013, 28, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomerus, H.; Hamster, W. Quality of Life in Cirrhotics with Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 2001, 16, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguedas, M.R.; DeLawrence, T.G.; McGuire, B.M. Influence of Hepatic Encephalopathy on Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 2003, 48, 1622–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanta, J.; Dhiman, R.K.; Khatri, A.; Thumburu, K.K.; Grover, S.; Duseja, A.; Chawla, Y. Correlation between Degree and Quality of Sleep Disturbance and the Level of Neuropsychiatric Impairment in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis. Metab Brain Dis 2013, 28, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marjot, T.; Ray, D.W.; Williams, F.R.; Tomlinson, J.W.; Armstrong, M.J. Sleep and Liver Disease: A Bidirectional Relationship. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 6, 850–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]