Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

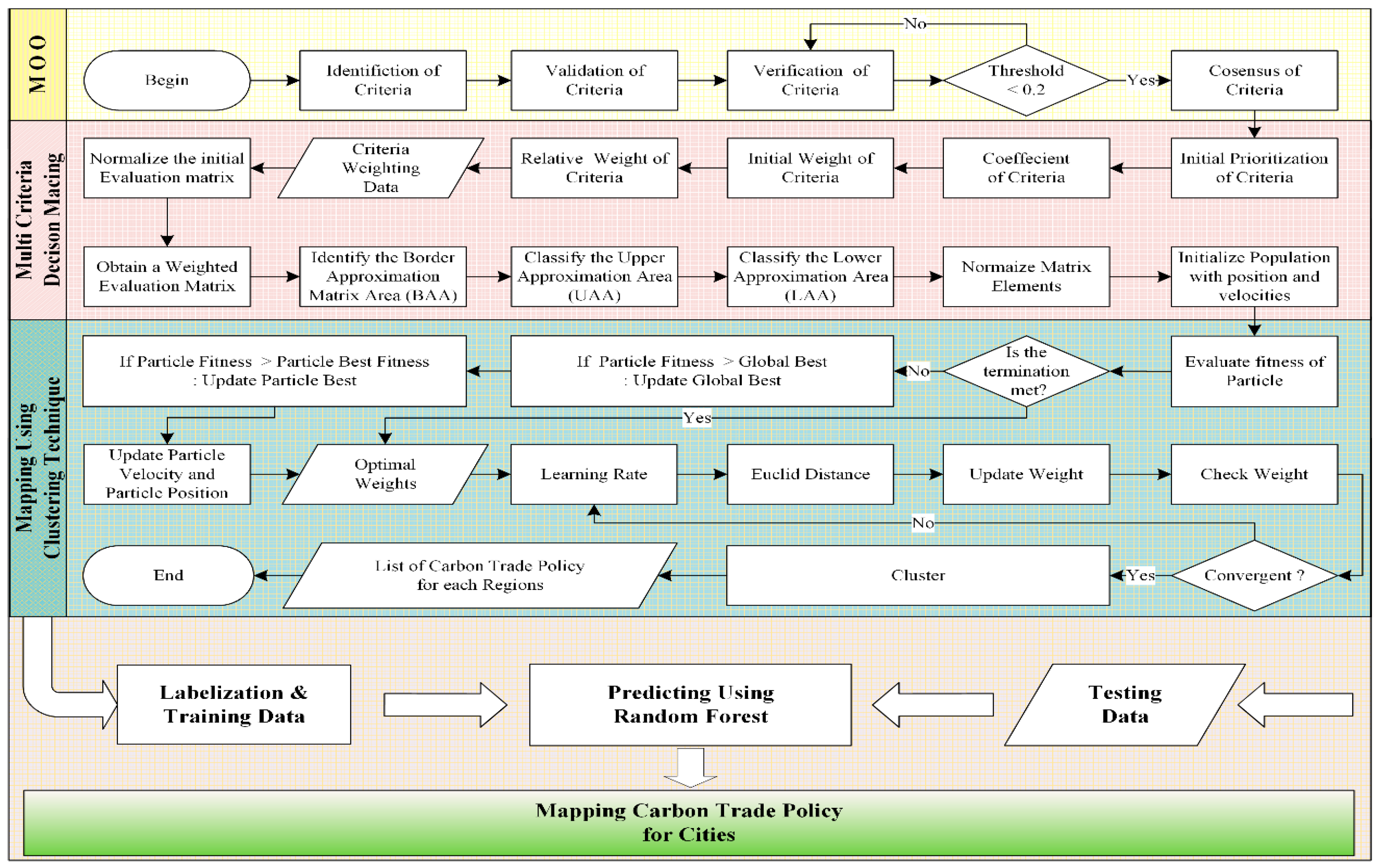

1. Introduction

- To find the optimal solution by considering several criteria that may be conflicting so as to help balance the influence of economic, social, environmental and political growth aspects on carbon trading using MOO.

- To determine the priority scale for carbon trade policy is based on criteria for each aspect using the MDCM.

- To identify patterns in data related to the effectiveness of carbon trading policies in various regions through mapping and grouping data using a hybrid PSOM.

- To predict the feasible carbon trading policies to be implemented in a city as a step to prepare for the future using a machine learning algorithm.

2. Related Work

2.1. Carbon Trade Policy

2.2. MOO and MCDM in Urban Policy

2.3. Applications in Energy and Emission Reduction

2.4. Advances in Hybrid Models and Future Directions

2.5. Contribution of The Proposed MOO-MCDM-PSOM Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Identification of Aspect and Criteria

3.2. Proposed Hybrid MOO-MCDM-PSOM

3.3. Data Collection

- Collection of data from a variety of sources, including policy documents, urban economic indicators, and environmental impact reports from municipalities.

- Cities are selected based on criteria such as their participation in carbon trading markets, availability of emissions data, and variation in policy implementation to ensure a representative sample for the MCDM process.

- The PSOM algorithm is used to optimize data extraction from various sources with adjustments based on feedback rounds to fine-tune policy impact modelling. In addition, qualitative data from stakeholder interviews will be integrated using the MCDM framework to align carbon policy trade-offs with city-level priorities.

4. Result and Discussion

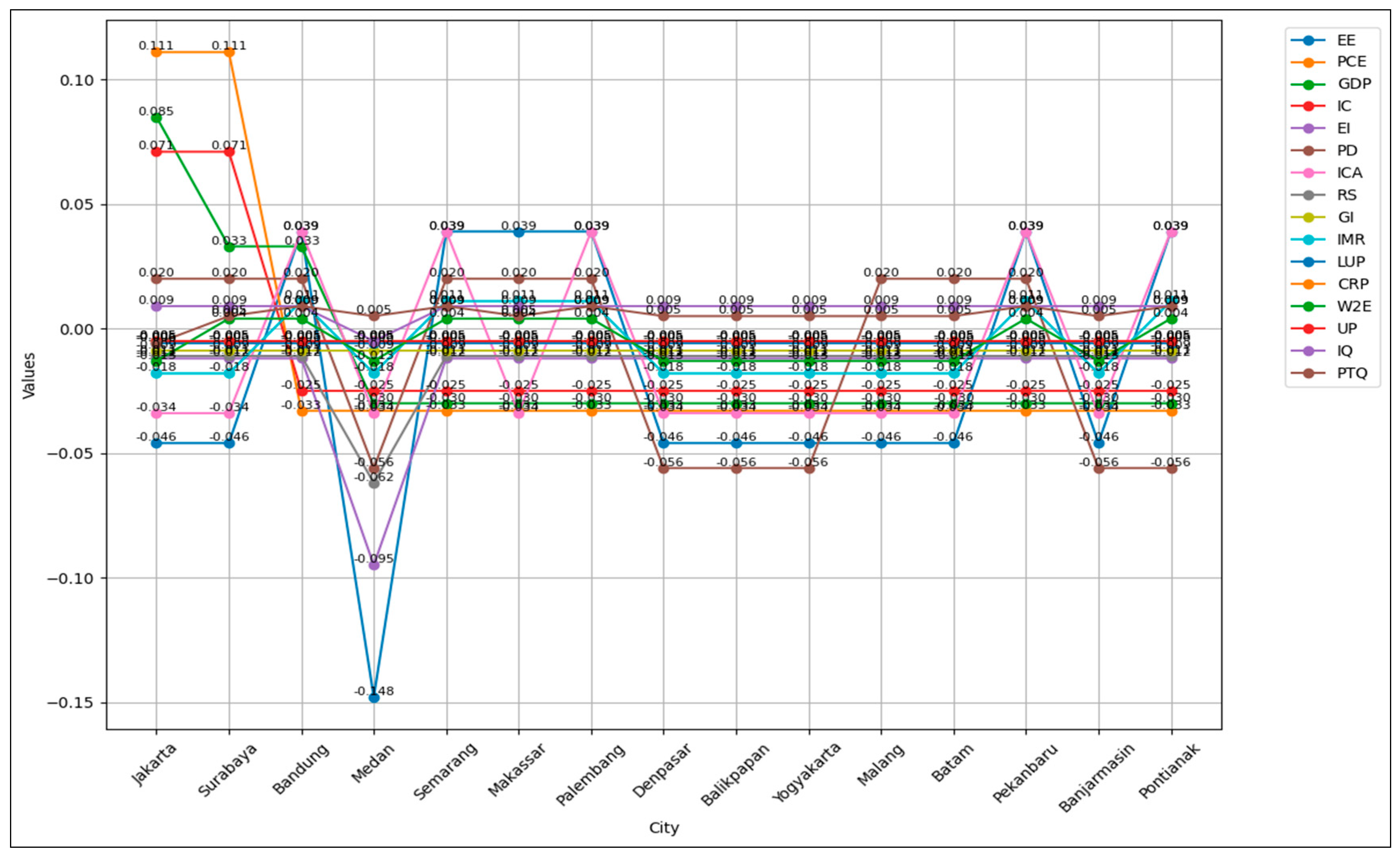

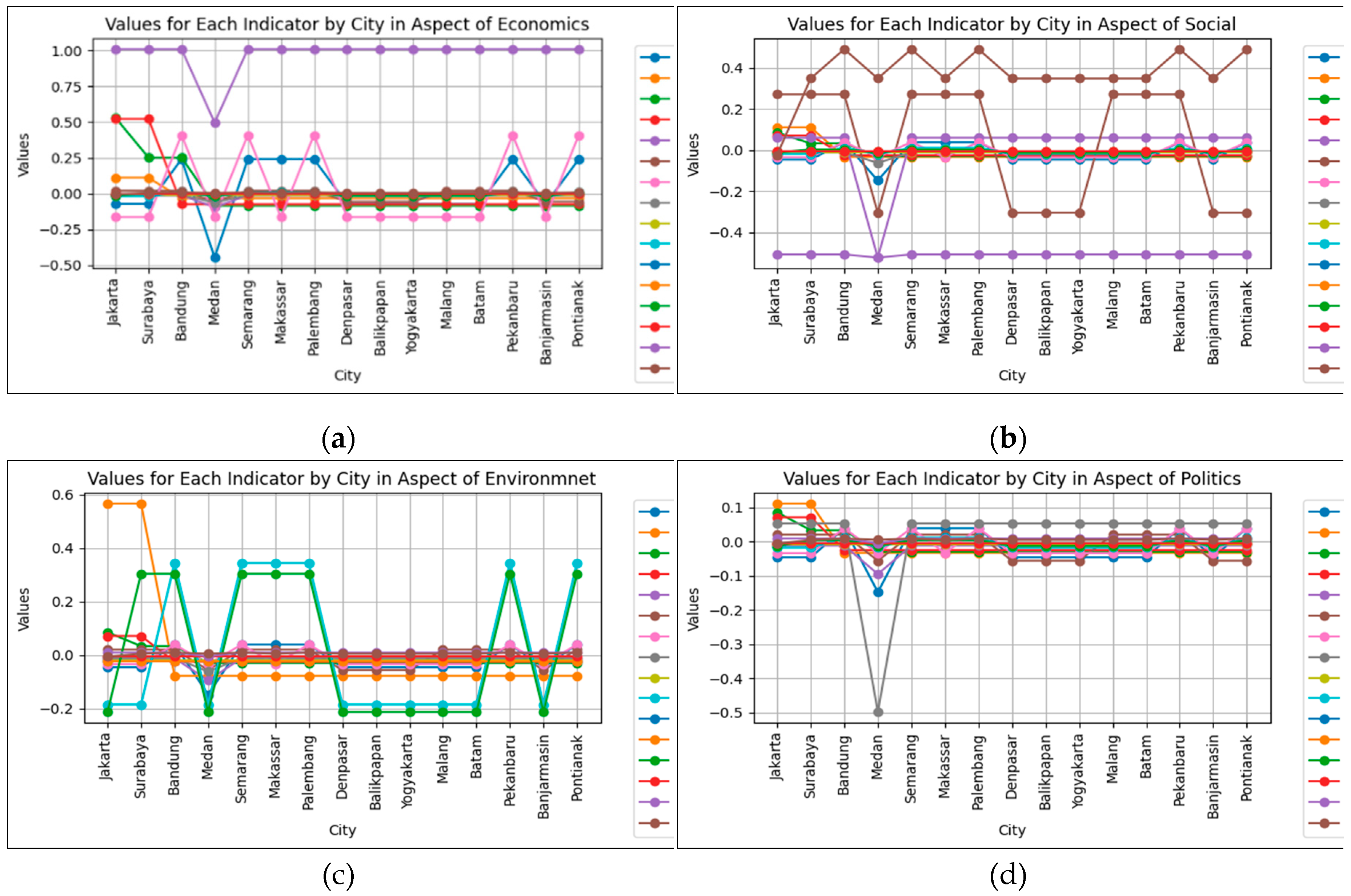

4.1. Application of hybrid MOO-MCDM-PSOM

- Positive Border Area:

- Intermediate Border Area:

- Negative Border Area:

- Particle initialization is when particles are initialized with random positions as small random weights and speeds, allowing hordes to explore the solution space.

- Speed and position update, where each particle updates its velocity based on three components: inertia, cognitive influence, and social influence, where the balance between exploration and convergence helps the swarm refine the search.

- Fitness evaluation is that each particle position is evaluated with a fitness function, where if a new position of a particle results in a lower quantization error than the previously known position, then its most famous position and score to be updated.

- The swarm's global best position and score are updated if any particle finds a new minimum quantization error.

- Policy-A, with Fiscal Incentives:

- Policy-B, with Strict Regulations:

- Policy-C, with Flexible Cap-and-Trade:

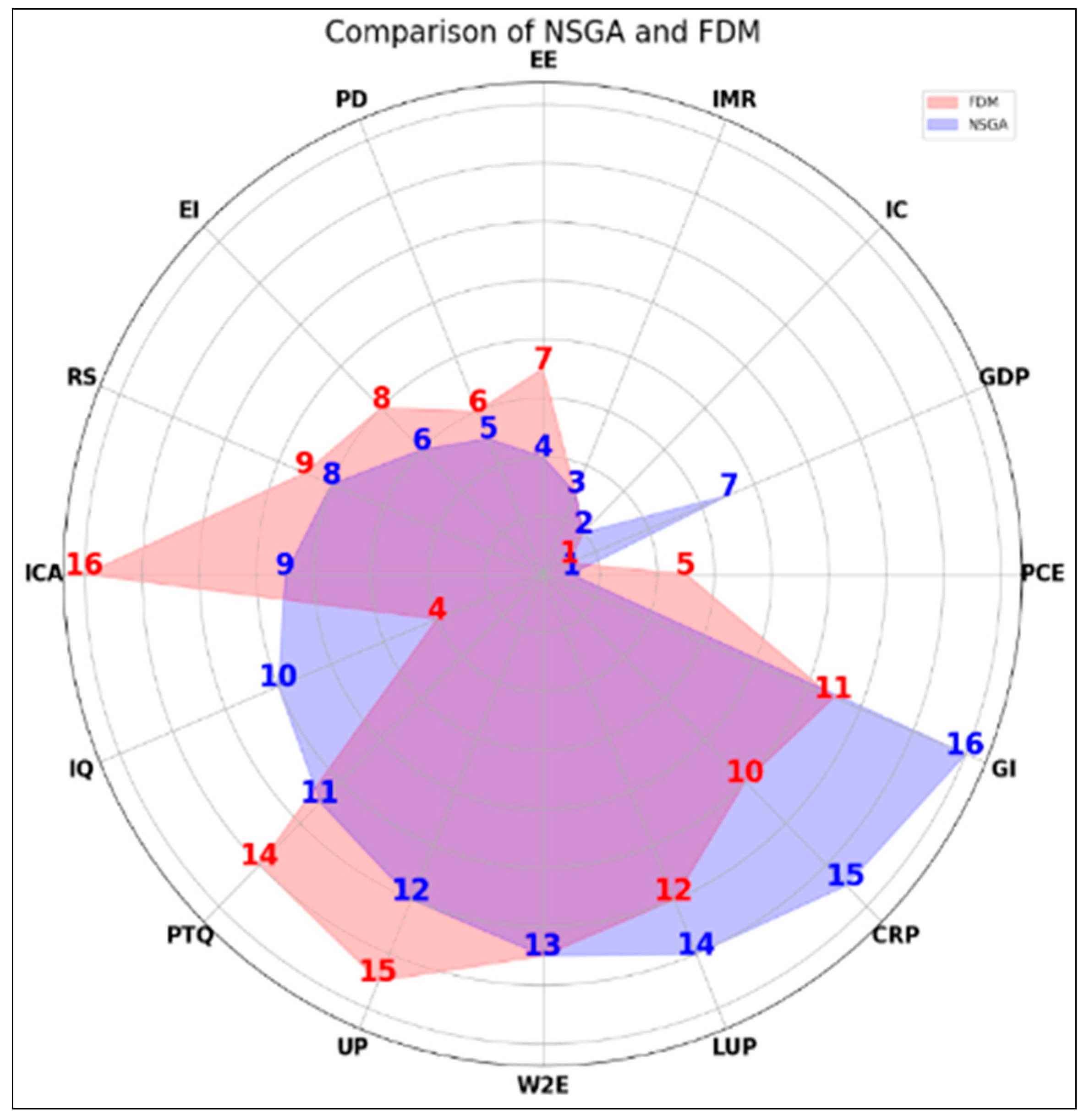

4.2. Sensitivity Test

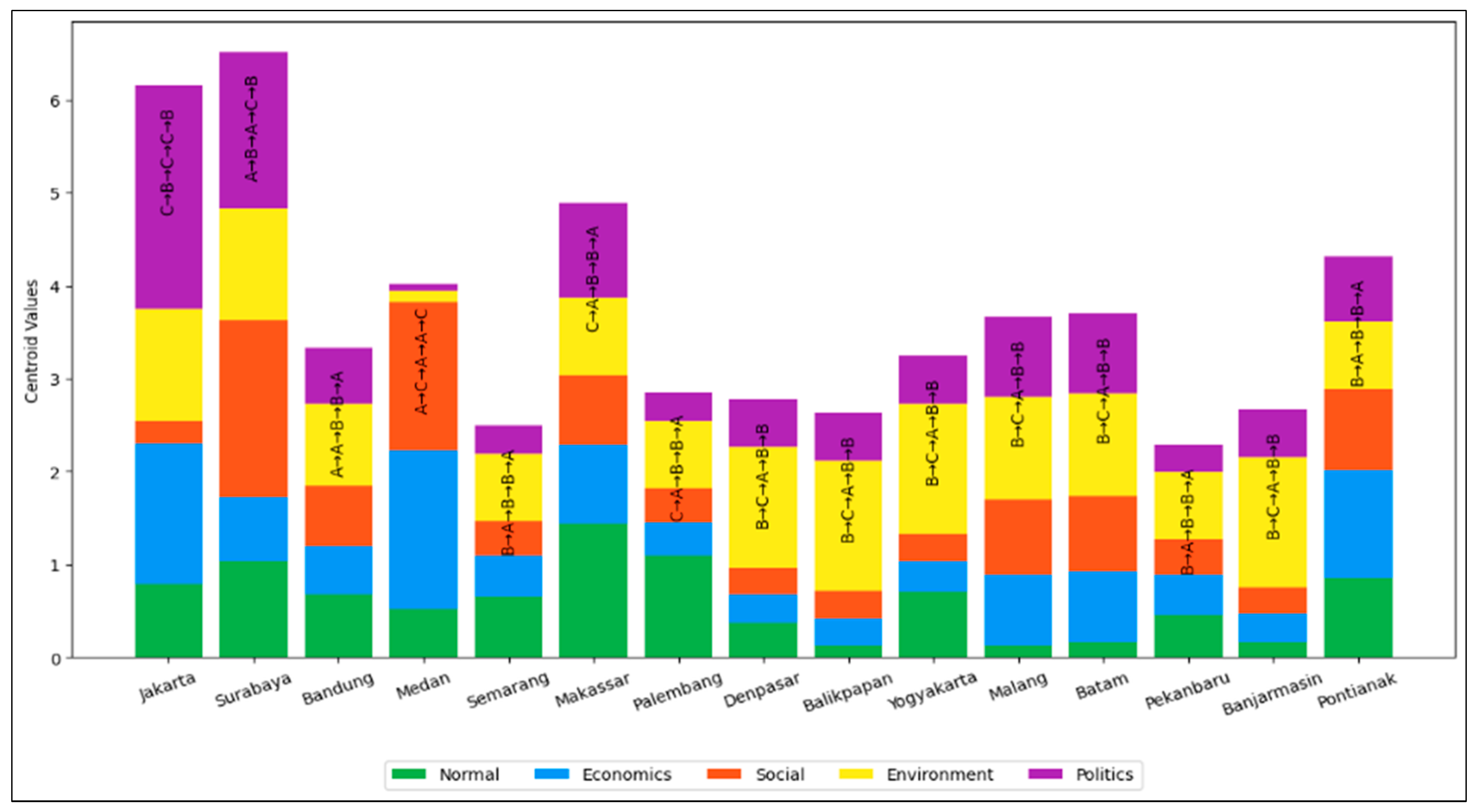

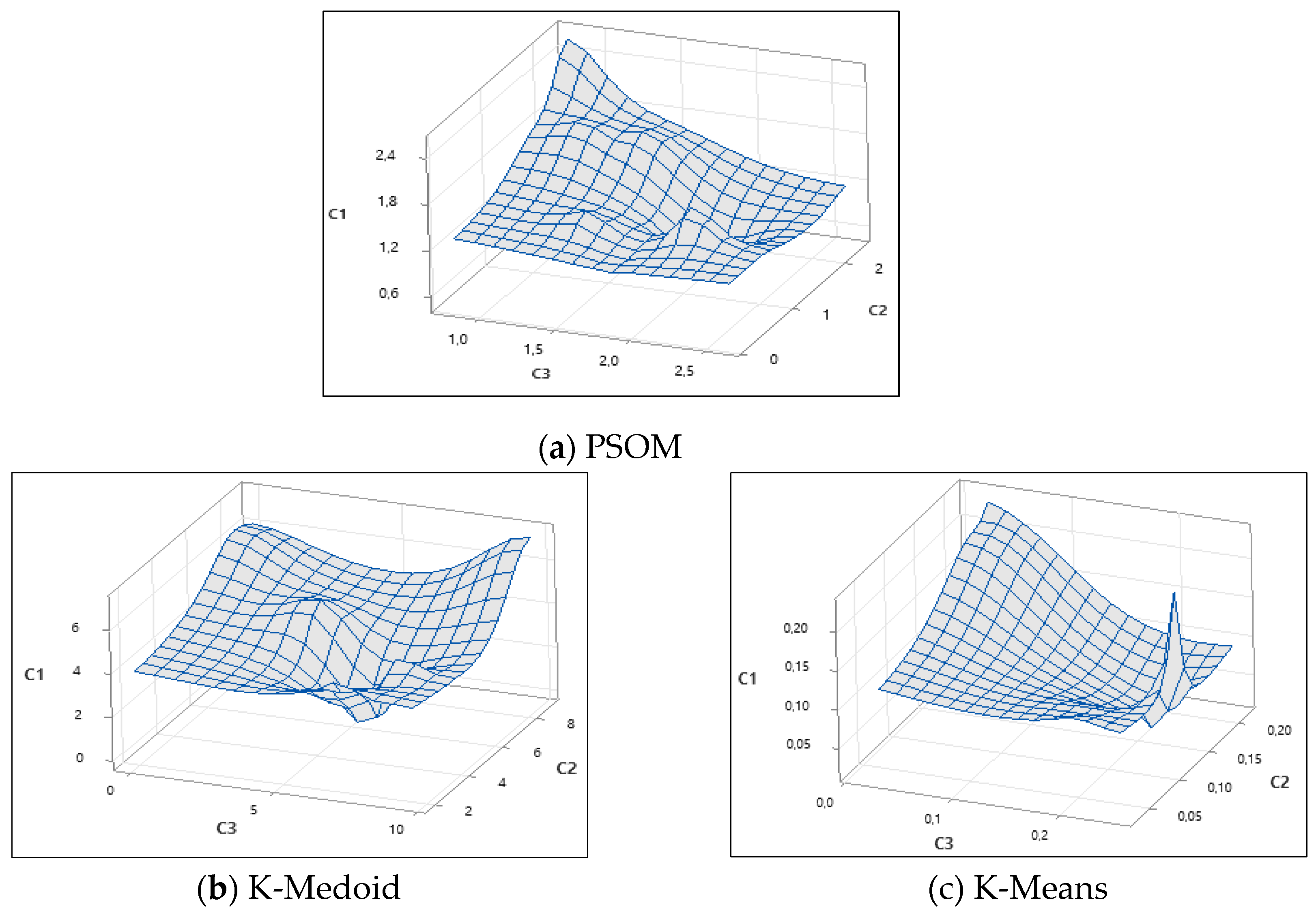

4.3. Identification of Patterns in Policy Effectiveness Using PSOM

4.4. Comparative analysis

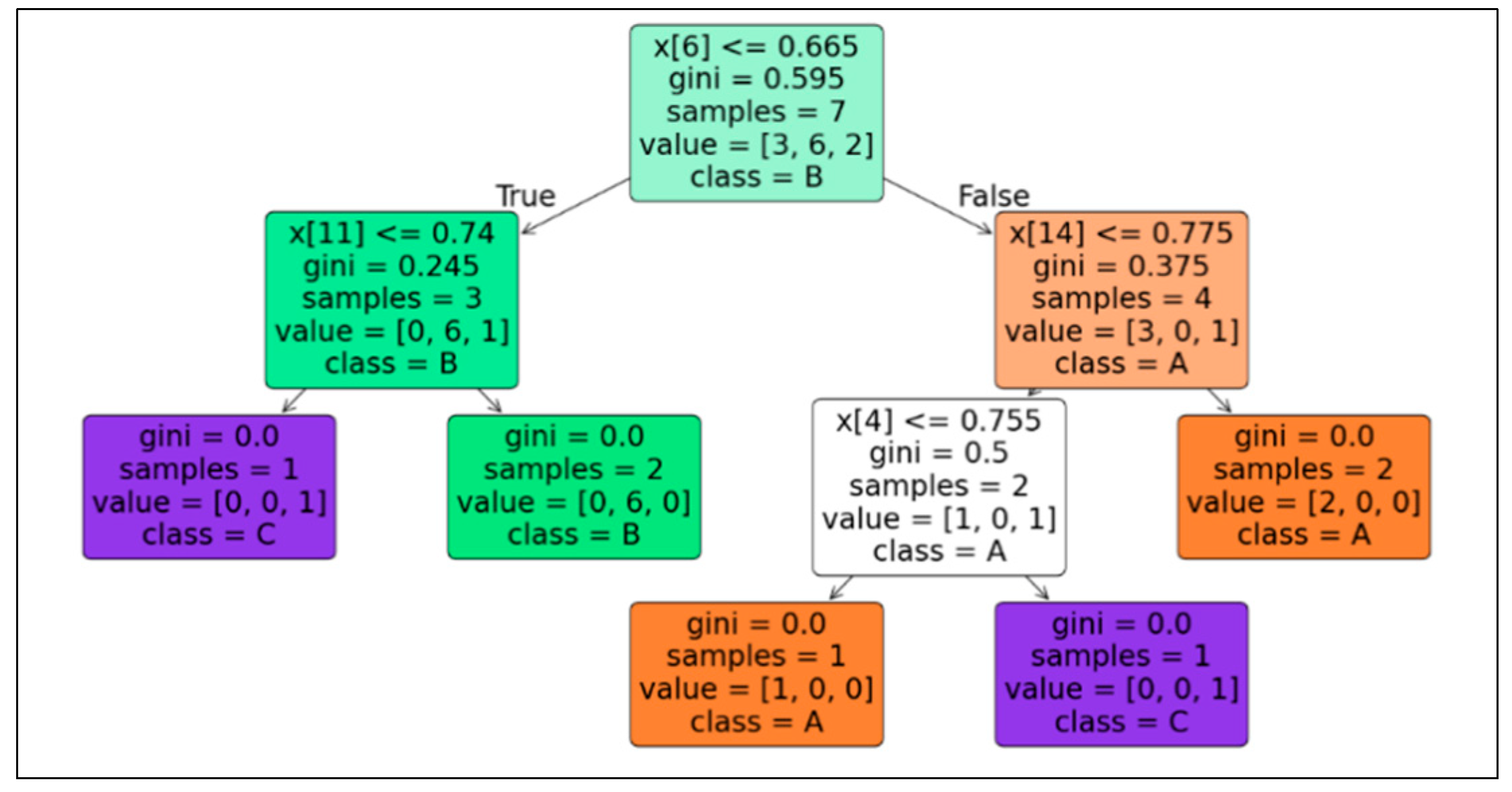

4.5. Machine Learning-Based Prediction Technique for Mapping Carbon Trade Policy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cui, Y.; Feng, W.; Gu, X. Research on the Spatial Spillover Effect of Carbon Trading Market Development on Regional Emission Reduction. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, R. Does Carbon Emission Trading Policy Has Emission Reduction Effect? —An Empirical Study Based on Quasi-Natural Experiment Method. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 351, 119791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adetama, D. S.; Fauzi, A.; Juanda, B.; Hakim, D. B. A Policy Framework and Prediction on Low Carbon Development in the Agricultural Sector in Indonesia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2022, 17(7), 2209–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Han, Z. How Can Carbon Trading Promote the Green Innovation Efficiency of Manufacturing Enterprises? Energy Strateg. Rev. 2024, 53, 101420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, R. Trade Openness Helps Move towards Carbon Neutrality—Insight from 114 Countries. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 32(1), 1081–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cho, S.-H.; Scheller-Wolf, A. Green Technology Development and Adoption: Competition, Regulation, and Uncertainty—A Global Game Approach. Manage. Sci. 2021, 67(1), 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.; Nguyen, C. P.; Le, T. N. L. Environmental Degradation &Amp; Role of Financialisation, Economic Development, Industrialisation and Trade Liberalisation. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 277, 111471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G. The Impact of Carbon Emissions Trading on the Total Factor Productivity of China’s Electric Power Enterprises—An Empirical Analysis Based on the Differences-in-Differences Model. Sustainability 2024, 16(7), 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lv, L.; Tang, R. Carbon Trading Mechanism, Low-Carbon E-Commerce Supply Chain and Sustainable Development. Mathematics 2021, 9(15), 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, T. The Impact of Carbon Emission and Carbon Price on International Trade Volume. Adv. Econ. Manag. Polit. Sci. 2024, 67(1), 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Sun, P. Exploring Air Pollution Characteristics from Spatio-Temporal Perspective: A Case Study of the Top 10 Urban Agglomerations in China. Environ. Res. 2023, 224, 115512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Li, D.; Wang, X. Study on the Influence of Carbon Trading Pilot Policy on Energy Efficiency in Power Industry. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2023, 15(2), 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, A.; Khan, M. Q.; Sun, W. Optimal Operation of Energy Hub Considering Reward-Punishment Ladder Carbon Trading and Electrothermal Demand Coupling. Energy 2024, 286, 129571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Liu, Q.; MacDonald, G. K.; Liu, Y.; Lin, J.; Cui, Q.; Feng, K.; Chen, B.; Adeniran, J. A.; Yang, L.; Li, X.; Lyu, K.; Liu, Y. Examining the Sensitivity of Global CO 2 Emissions to Trade Restrictions over Multiple Years. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2022, 9(4), 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Zhao, M. Agricultural Economic Evidence and Policy Prospects under Agricultural Trade Shocks and Carbon Dioxide Emissions. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Zhao, Y. The Impact of Carbon Trading on the “Quantity” and “Quality” of Green Technology Innovation: A Dynamic QCA Analysis Based on Carbon Trading Pilot Areas. Heliyon 2024, 10(3), e25668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Xia, Z.; Fan, S.; Gong, W. Energy Conservation and Emission Reduction Effect and Potential Emission Reduction Mechanism of China’s Thermal Power Generation Industry – Evidence from Carbon Emission Trading Policy. Polish J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32(5), 4825–4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; He, Y.; Yang, D.; Liu, S. A Novel Three-Way Decision-Making Method for Logistics Enterprises’ Carbon Trading Considering Attribute Reduction and Hesitation Degree. Inf. Sci. (Ny). 2024, 658, 119996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiva Noor Rachmayani. Comparing Different Approaches to Tackle the Challenges of Global Carbon Pricing; WTO Working Papers; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nahtigal, M. Pathways from the (Semi) Periphery: Early Assessment of EU Mercosur Trade Agreement in Principle. Am. J. Trade Policy 2023, 10(2), 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W. A Comparative Study of Carbon Pricing Policies in China and the Scandinavian Countries: Lessons for Effective Climate Change Mitigation with a Focus on Sweden. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 424, 04005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, Z.; Tang, F. The Effect of Carbon Price Volatility on Firm Green Transitions: Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Listed Firms. Energies 2022, 15(20), 7456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, J.; Bensebaa, F.; Milani, A. S.; Hewage, K.; Bhowmik, P.; Pelletier, N. Development of a Generic Decision Tree for the Integration of Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) and Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) Methods under Uncertainty to Facilitate Sustainability Assessment: A Methodical Review. Sustainability 2024, 16(7), 2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez Gallo, S.; Maheut, J. Multi-Criteria Analysis for the Evaluation of Urban Freight Logistics Solutions: A Systematic Literature Review. Mathematics 2023, 11(19), 4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Norambuena, P.; Martinez-Torres, J.; Nemati, A.; Hashemkhani Zolfani, S.; Antucheviciene, J. Towards Sustainable Urban Futures: Integrating a Novel Grey Multi-Criteria Decision Making Model for Optimal Pedestrian Walkway Site Selection. Sustainability 2024, 16(11), 4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz-Ghorabaee, M.; Amiri, M.; Zavadskas, E. K.; Turskis, Z.; Antuchevičienė, J. MCDM APPROACHES FOR EVALUATING URBAN AND PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS: A SHORT REVIEW OF RECENT STUDIES. Transport 2022, 37(6), 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Li, L.; Dong, J.; Zhang, B. Reduction Effect and Mechanism Analysis of Carbon Trading Policy on Carbon Emissions from Land Use. Sustainability 2021, 13(17), 9558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinatizadeh, S.; Azmi, A.; Monavari, S. M.; Sobhanardakani, S. Multi-Criteria Decision Making for Sustainability Evaluation in Urban Areas: A Case Study for Kermanshah City, Iran. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2017, 15(4), 1083–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, K.; Karayannis, V.; Moustakas, K. Circular Bio-Economy via Energy Transition Supported by Fuzzy Cognitive Map Modeling towards Sustainable Low-Carbon Environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 721, 137754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmat, A.; Ghiassi-Farrokhfal, Y.; Gunkel, P. A.; Bergaentzlé, C.-M. A Decision Support System for Green and Economical Individual Heating Resource Planning. Appl. Energy 2023, 347, 121442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Song, Y.; Ding, C.; Cheng, J.; Li, S.; Li, G. Optimal Bidding Strategy for PV and BESSs in Joint Energy and Frequency Regulation Markets Considering Carbon Reduction Benefits. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2024, 12(2), 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Xu, Q.; Liu, W.; Xu, Z. Low-carbon Economic Optimal Operation Strategy of Rural Multi-microgrids Based on Asymmetric Nash Bargaining. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2024, 18(1), 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, J.; Cerdas, F.; Heidrich, O. An Integrated Model to Conduct Multi-Criteria Technology Assessments: The Case of Electric Vehicle Batteries. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57(12), 5056–5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Yang, Y.; Qu, N.; Xi, Y.; Guo, X.; Dong, Y. A Low-Carbon Economic Dispatch Method for Regional Integrated Energy System Based on Multi-Objective Chaotic Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14(1), 4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J. Design of a Low Carbon Economy Model by Carbon Cycle Optimization in Supply Chain. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wu, K. Research on Multi-Objective Optimization of Energy Power System under Low Carbon Constraints. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2442(1), 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Dong, J.; Song, Y. Impact and Acting Path of Carbon Emission Trading on Carbon Emission Intensity of Construction Land: Evidence from Pilot Areas in China. Sustainability 2020, 12(19), 7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, D.; Kong, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, T.; Boamah, V. The Carbon Effects of the Evolution of Node Status in the World Trade Network. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J. Carbon Emission Trading Policy and Carbon Emission Efficiency: An Empirical Analysis of China’s Prefecture-Level Cities. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Fei, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yao, X.; Yang, S. The Impact of China’s ETS on Corporate Green Governance Based on the Perspective of Corporate ESG Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20(3), 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Luo, J. Impact on Carbon Intensity of Carbon Emission Trading—Evidence from a Pilot Program in 281 Cities in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19(19), 12483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Li, N.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y. Modeling Intercity CO2 Trading Scenarios in China: Complexity of Urban Networks Integrating Different Spatial Scales. Complexity 2022, 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. Does Carbon Emissions Trading Facilitate Carbon Unlocking? Empirical Evidence from China. J. Econ. Stat. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira-Rodado, D.; Jimenez-Delgado, G.; Crespo, F.; Morales Espinosa, R. A.; Plazas Alvarez, J. R.; Hernandez, H. A Hybrid MOO/MCDM Optimization Approach to Improve Decision-Making in Multiobjective Optimization. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); 2023; Vol. 14056 LNCS, pp 100–111. [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Rahman, T. K. A. Optimally Enhancement Rural Development Support Using Hybrid Multy Object Optimization (MOO) and Clustering Methodologies: A Case South Sulawesi - Indonesia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18(6), 1659–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, R. T.; Yaakob, R.; Sharef, N. M.; Abdullah, R. Unifying The Evaluation Criteria Of Many Objectives Optimization Using Fuzzy Delphi Method. Baghdad Sci. J. 2021, 4 (Suppl.)), 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Rahman, T. K. A.; Mulyadi, I.; Aryasa, K.; Irmawati; Thamrin, M. A Novelty Decision-Making Based on Hybrid Indexing, Clustering, and Classification Methodologies: An Application to Map the Relevant Experts Against the Rural Problem. Decis. Mak. Appl. Manag. Eng. 2024, 7 (2), 132–171. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E. A.; Kofi Alimo, P.; Abudu, R.; Lu, P. Towards Sustainable Freight Transportation in Africa: Complementarity of the Fuzzy Delphi and Best-Worst Methods. Sustain. Futur. 2024, 8, 100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvari, H.; Baghbaderani, A. B.; Chan, D. W. M.; Beer, M. Determining the Significant Contributing Factors to the Occurrence of Human Errors in the Urban Construction Projects: A Delphi-SWARA Study Approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 205, 123512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Irmawati, .; Rahman, T. K. A.; Jufri, .; Sahabuddin, .; Herlinah, .; Mulyadi, I. A Hybrid MOO, MCGDM, and Sentiment Analysis Methodologies for Enhancing Regional Expansion Planning: A Case Study Luwu - Indonesia. Int. J. Math. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2025, 10 (1), 163–188. [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, J.; Alves, P.; Marreiros, G.; Novais, P. Group Decision Support Systems for Current Times: Overcoming the Challenges of Dispersed Group Decision-Making. Neurocomputing 2021, 423, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, L. P.; Marchesan, T. B.; Siluk, J. C. M.; Rediske, G.; Ricci, M. R. Steps and Maturity of a Bioinput for Biological Control: A Delphi-SWARA Application. Biol. Control 2024, 191, 105477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, E.; Mirzaei Aliabadi, M. Risk Assessment of Firefighting Job Using Hybrid SWARA-ARAS Methods in Fuzzy Environment. Heliyon 2023, 9(11), e22230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Li, H.; Zhou, L.; Wu, Q. The SMAA-MABAC Approach for Healthcare Supplier Selection in Belief Distribution Environment with Uncertainties. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 129, 107654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, N.; Chen, J.; Zuo, J.; Liu, J. PSO–SOM Neural Network Algorithm for Series Arc Fault Detection. Adv. Math. Phys. 2020, 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Shiliang, S.; Yi, L.; He, L. Research on Risk Identification of Coal and Gas Outburst Based on PSO-CSA. Math. Probl. Eng. 2023, 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, A.; Lei, J.; Sun, M. Transformer Fault Diagnosis Based on Chaotic Particle Swarm Optimization RBF Neural Network. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2625(1), 012074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jufri, A. B. A. R. and H. S. Exploring the Impact of Social Media on Political Discourse: A Case Study of the Makassar Mayoral Election. Int. J. Adv. Technol. Eng. Explor. 2024, 11 (114). [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Rahman, T. K. A. Optimally Enhancement Rural Development Support Using Hybrid Multy Object Optimization (MOO) and Clustering Methodologies: A Case South Sulawesi - Indonesia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18(6), 1659–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Rahman, T. K. A.; Mulyadi, I.; Aryasa, K.; Irmawati; Thamrin, M. A Novelty Decision-Making Based on Hybrid Indexing, Clustering, and Classification Methodologies: An Application to Map the Relevant Experts Against the Rural Problem. Decis. Mak. Appl. Manag. Eng. 2024, 7 (2), 132–171. [CrossRef]

| Expert | PCE | GDP | IC | IMR | EE | PD | EI | RS | ICA | IQ | PTQ | UP | W2E | LUP | CRP | GI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T | A | T | T | T | T | T | T | A | T | A | S | A | T | A | T |

| 2 | S | A | T | T | T | T | T | T | A | T | A | S | A | S | A | T |

| 3 | T | T | A | T | T | T | A | T | A | A | A | A | A | S | T | T |

| 4 | T | T | T | T | T | T | A | S | A | T | A | T | S | S | T | S |

| 5 | T | T | T | A | A | T | A | S | A | T | A | S | T | T | T | A |

| 6 | A | T | T | T | A | T | T | T | A | T | S | S | T | T | T | T |

| 7 | T | T | T | T | T | T | T | T | A | T | T | A | A | A | T | A |

| 8 | T | T | T | T | A | T | T | T | A | T | S | A | A | A | A | A |

| 9 | A | T | A | T | T | T | T | A | A | T | A | A | T | A | A | A |

| 10 | T | T | T | T | T | A | T | A | A | T | A | A | A | A | A | T |

| 11 | T | T | T | A | T | A | T | T | A | A | A | A | T | T | A | T |

| 12 | T | T | T | A | T | A | T | T | A | T | A | A | A | A | T | A |

| 13 | T | T | T | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | T | T | A | T | T | S |

| 14 | T | T | A | T | T | T | T | T | S | T | A | A | A | A | T | T |

| 15 | T | T | A | T | A | A | A | A | A | A | T | T | S | A | A | A |

| 16 | A | T | T | T | A | A | A | A | A | A | S | T | A | T | A | A |

| Threshold | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| F-Evaluation | 11.8 | 12.4 | 12 | 12 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 9.4 | 11.8 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 10 | 10.2 | 11.2 | 10.8 |

| F-Number | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0.75 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.67 |

| Construction | 0.086 | |||||||||||||||

| Consensus | 0.960 | |||||||||||||||

| Criteria | Index | Sj | Kj | Qi | Wi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.18753 |

| PCE | 2 | 0.30 | 1.30 | 0.7692 | 0.14425 |

| GDP | 3 | 0.25 | 1.25 | 0.6154 | 0.11540 |

| IC | 4 | 0.20 | 1.20 | 0.5128 | 0.09617 |

| EI | 5 | 0.15 | 1.15 | 0.4459 | 0.08362 |

| PD | 6 | 0.10 | 1.10 | 0.4054 | 0.07602 |

| ICA | 7 | 0.05 | 1.05 | 0.3861 | 0.07240 |

| RS | 8 | 0.40 | 1.40 | 0.2758 | 0.05172 |

| GI | 9 | 0.35 | 1.35 | 0.2043 | 0.03831 |

| IMR | 10 | 0.30 | 1.30 | 0.1571 | 0.02947 |

| LUP | 11 | 0.25 | 1.25 | 0.1257 | 0.02357 |

| CRP | 12 | 0.20 | 1.20 | 0.1048 | 0.01964 |

| W2E | 13 | 0.15 | 1.15 | 0.0911 | 0.01708 |

| UP | 14 | 0.10 | 1.10 | 0.0828 | 0.01553 |

| IQ | 15 | 0.05 | 1.05 | 0.0789 | 0.01479 |

| PTQ | 16 | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.0773 | 0.01450 |

| Subcriteria ([Benefit] ; [Cost]) | Sj | Kj | Qi | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Extremely High] ; [Low] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.3966 |

| [High] ; [Average] | 0.3333 | 1.3333 | 0.75 | 0.2974 |

| Moderate | 0.6666 | 1.6666 | 0.45 | 0.1784 |

| [Average] ; [High] | 1 | 2 | 0.225 | 0.0892 |

| [Low] ; [Extremely High] | 1.3333 | 2.3333 | 0.0964 | 0.0382 |

| Criteria | Low | Average | Moderat | High | Extremely High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE | < 0.50 | 0.50 - 0.60 | 0.60 - 0.70 | 0.70 - 0.80 | > 0.80 |

| PCE | < 1 ton | 1 - 4 ton | 4 - 7 ton | 7 - 10 ton | > 10 ton |

| GDP | < $5000 | $5000 - $10000 | $10000 - $20000 | $20000 - $30000 | > $30000 |

| IC | < 0.10 | 0.10 - 0.20 | 0.20 - 0.35 | 0.35 - 0.50 | > 0.50 |

| EI | < 0.30 | 0.30 - 0.50 | 0. 50 - 0.70 | 0.70 - 0.90 | > 0.90 |

| PD | < 2000 | 2000 - 4000 | 4000 - 7000 | 7000 - 10000 | > 10000 |

| ICA | < 0.10 | 0.10 - 0.30 | 0.30 - 0.50 | 0.50 – 0.70 | > 0.70 |

| RS | 0 - 0.10 | 0.10 - 0.30 | 0.30 - 0.50 | 0.50 - 0.70 | > 0.70 |

| GI | < 0.05 | 0.05 - 0.15 | 0.15 - 0.30 | 0.30 - 0.50 | > 0.50 |

| IMR | < 0.05 | 0.05 - 0.15 | 0.15 - 0.30 | 0.30 - 0.50 | > 0.50 |

| LUP | < 0.10 | 0.10 - 0.20 | 0.20 - 0.30 | 0.30 - 0.40 | > 0.40 |

| CRP | < 0.05 | 0.05 - 0.15 | 0.15 - 0.30 | 0.30 - 0.50 | > 0.50 |

| W2E | < 0.10 | 0.10 - 0.30 | 0.30 - 0.50 | 0.50 - 0.70 | > 0.70 |

| UP | < 0.05 | 0.05 - 0.15 | 0.15 - 0.30 | 0.30 - 0.50 | > 0.50 |

| IQ | < 0.10 | 0.10 - 0.30 | 0.30 - 0.50 | 0.50 - 0.70 | > 0.70 |

| PTQ | < 0.10 | 0.10 - 0.30 | 0.30 - 0.50 | 0.50 - 0.70 | > 0.70 |

| City | EE | PCE | GDP | IC | EI | PD | ICA | RS | GI | IMR | LUP | CRP | W2E | UP | IQ | PTQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jakarta | 0.75 | 6.0 | $40000 | 0.50 | 0.80 | 15000 | 0.70 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.25 | 0.70 | 0.85 | 0.30 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.07 |

| Surabaya | 0.80 | 4.5 | $30000 | 0.40 | 0.75 | 12000 | 0.65 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.30 | 0.65 | 0.80 | 0.35 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.65 |

| Bandung | 0.85 | 3.5 | $25000 | 0.30 | 0.85 | 14000 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.35 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.40 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.80 |

| Medan | 0.70 | 4.0 | $20000 | 0.35 | 0.70 | 10000 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.20 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.25 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.60 |

| Semarang | 0.90 | 3.0 | $15000 | 0.25 | 0.90 | 11000 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.40 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.45 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.75 |

| Makassar | 0.82 | 3.2 | $16000 | 0.30 | 0.82 | 10500 | 0.68 | 0.78 | 0.82 | 0.32 | 0.68 | 0.78 | 0.32 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.68 |

| Palembang | 0.84 | 3.7 | $18000 | 0.33 | 0.84 | 10800 | 0.72 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.34 | 0.72 | 0.82 | 0.37 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.72 |

| Denpasar | 0.78 | 2.8 | $14000 | 0.28 | 0.78 | 9500 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.28 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.28 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.66 |

| Balikpapan | 0.80 | 2.9 | $14500 | 0.29 | 0.80 | 9800 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.70 |

| Yogyakarta | 0.75 | 2.6 | $13000 | 0.26 | 0.75 | 8600 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.65 |

| Malang | 0.77 | 3.1 | $15500 | 0.31 | 0.77 | 10200 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.27 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.27 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.69 |

| Batam | 0.80 | 3.3 | $16500 | 0.35 | 0.80 | 10700 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.70 |

| Pekanbaru | 0.83 | 3.4 | $17000 | 0.32 | 0.83 | 10900 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.33 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.73 |

| Banjarmasin | 0.79 | 3.0 | $15000 | 0.30 | 0.79 | 9000 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.29 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.29 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.67 |

| Pontianak | 0.81 | 2.7 | $13500 | 0.27 | 0.81 | 9300 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.31 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.31 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.71 |

| City | EE | PCE | GDP | IC | EI | PD | ICA | RS | GI | IMR | LUP | CRP | W2E | UP | IQ | PTQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jakarta | 0.290 | 0.289 | 0.231 | 0.192 | 0.167 | 0.152 | 0.072 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.029 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.015 |

| Surabaya | 0.290 | 0.289 | 0.178 | 0.192 | 0.167 | 0.152 | 0.072 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.029 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.034 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.025 |

| Bandung | 0.375 | 0.144 | 0.178 | 0.096 | 0.167 | 0.152 | 0.145 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.059 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.034 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.029 |

| Medan | 0.188 | 0.144 | 0.115 | 0.096 | 0.084 | 0.076 | 0.072 | 0.052 | 0.038 | 0.029 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.025 |

| Semarang | 0.375 | 0.144 | 0.115 | 0.096 | 0.167 | 0.152 | 0.145 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.059 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.034 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.029 |

| Makassar | 0.375 | 0.144 | 0.115 | 0.096 | 0.167 | 0.152 | 0.072 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.059 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.034 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.025 |

| Palembang | 0.375 | 0.144 | 0.115 | 0.096 | 0.167 | 0.152 | 0.145 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.059 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.034 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.029 |

| Denpasar | 0.290 | 0.144 | 0.115 | 0.096 | 0.167 | 0.076 | 0.072 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.029 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.025 |

| Balikpapan | 0.290 | 0.144 | 0.115 | 0.096 | 0.167 | 0.076 | 0.072 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.029 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.025 |

| Yogyakarta | 0.290 | 0.144 | 0.115 | 0.096 | 0.167 | 0.076 | 0.072 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.029 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.025 |

| Malang | 0.290 | 0.144 | 0.115 | 0.096 | 0.167 | 0.152 | 0.072 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.029 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.025 |

| Batam | 0.290 | 0.144 | 0.115 | 0.096 | 0.167 | 0.152 | 0.072 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.029 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.025 |

| Pekanbaru | 0.375 | 0.144 | 0.115 | 0.096 | 0.167 | 0.152 | 0.145 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.059 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.034 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.029 |

| Banjarmasin | 0.290 | 0.144 | 0.115 | 0.096 | 0.167 | 0.076 | 0.072 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.029 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.025 |

| Pontianak | 0.375 | 0.144 | 0.115 | 0.096 | 0.167 | 0.076 | 0.145 | 0.103 | 0.038 | 0.059 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.034 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.029 |

| City | EE | PCE | GDP | IC | EI | PD | ICA | RS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jakarta | -0.046 | 0.111 | 0.085 | 0.071 | -0.012 | 0.020 | -0.034 | -0.011 |

| Surabaya | -0.046 | 0.111 | 0.033 | 0.071 | -0.012 | 0.020 | -0.034 | -0.011 |

| Bandung | 0.039 | -0.033 | 0.033 | -0.025 | -0.012 | 0.020 | 0.039 | -0.011 |

| Medan | -0.148 | -0.033 | -0.030 | -0.025 | -0.095 | -0.056 | -0.034 | -0.062 |

| Semarang | 0.039 | -0.033 | -0.030 | -0.025 | -0.012 | 0.020 | 0.039 | -0.011 |

| Makassar | 0.039 | -0.033 | -0.030 | -0.025 | -0.012 | 0.020 | -0.034 | -0.011 |

| Palembang | 0.039 | -0.033 | -0.030 | -0.025 | -0.012 | 0.020 | 0.039 | -0.011 |

| Denpasar | -0.046 | -0.033 | -0.030 | -0.025 | -0.012 | -0.056 | -0.034 | -0.011 |

| Balikpapan | -0.046 | -0.033 | -0.030 | -0.025 | -0.012 | -0.056 | -0.034 | -0.011 |

| Yogyakarta | -0.046 | -0.033 | -0.030 | -0.025 | -0.012 | -0.056 | -0.034 | -0.011 |

| Malang | -0.046 | -0.033 | -0.030 | -0.025 | -0.012 | 0.020 | -0.034 | -0.011 |

| Batam | -0.046 | -0.033 | -0.030 | -0.025 | -0.012 | 0.020 | -0.034 | -0.011 |

| Pekanbaru | 0.039 | -0.033 | -0.030 | -0.025 | -0.012 | 0.020 | 0.039 | -0.011 |

| Banjarmasin | -0.046 | -0.033 | -0.030 | -0.025 | -0.012 | -0.056 | -0.034 | -0.011 |

| Pontianak | 0.039 | -0.033 | -0.030 | -0.025 | -0.012 | -0.056 | 0.039 | -0.011 |

| City | GI | IMR | LUP | CRP | W2E | UP | IQ | PTQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jakarta | -0.009 | -0.018 | -0.006 | -0.005 | -0.013 | -0.005 | 0.009 | -0.006 |

| Surabaya | -0.009 | -0.018 | -0.006 | -0.005 | 0.004 | -0.005 | 0.009 | 0.005 |

| Bandung | -0.009 | 0.011 | -0.006 | -0.005 | 0.004 | -0.005 | 0.009 | 0.009 |

| Medan | -0.009 | -0.018 | -0.006 | -0.005 | -0.013 | -0.005 | -0.005 | 0.005 |

| Semarang | -0.009 | 0.011 | -0.006 | -0.005 | 0.004 | -0.005 | 0.009 | 0.009 |

| Makassar | -0.009 | 0.011 | -0.006 | -0.005 | 0.004 | -0.005 | 0.009 | 0.005 |

| Palembang | -0.009 | 0.011 | -0.006 | -0.005 | 0.004 | -0.005 | 0.009 | 0.009 |

| Denpasar | -0.009 | -0.018 | -0.006 | -0.005 | -0.013 | -0.005 | 0.009 | 0.005 |

| Balikpapan | -0.009 | -0.018 | -0.006 | -0.005 | -0.013 | -0.005 | 0.009 | 0.005 |

| Yogyakarta | -0.009 | -0.018 | -0.006 | -0.005 | -0.013 | -0.005 | 0.009 | 0.005 |

| Malang | -0.009 | -0.018 | -0.006 | -0.005 | -0.013 | -0.005 | 0.009 | 0.005 |

| Batam | -0.009 | -0.018 | -0.006 | -0.005 | -0.013 | -0.005 | 0.009 | 0.005 |

| Pekanbaru | -0.009 | 0.011 | -0.006 | -0.005 | 0.004 | -0.005 | 0.009 | 0.009 |

| Banjarmasin | -0.009 | -0.018 | -0.006 | -0.005 | -0.013 | -0.005 | 0.009 | 0.005 |

| Pontianak | -0.009 | 0.011 | -0.006 | -0.005 | 0.004 | -0.005 | 0.009 | 0.009 |

| City | C1 | C2 | C3 | Cluster | Policy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jakarta | 2.5791 | 2.3419 | 0.7960 | 3 | C |

| Surabaya | 1.0409 | 1.7120 | 2.6131 | 1 | A |

| Bandung | 0.6810 | 1.3807 | 2.1166 | 1 | A |

| Medan | 0.5233 | 1.1751 | 2.0222 | 1 | A |

| Semarang | 1.1352 | 0.6548 | 1.8289 | 2 | B |

| Makassar | 1.8333 | 1.8541 | 1.4470 | 3 | C |

| Palembang | 1.9556 | 1.7045 | 1.0995 | 3 | C |

| Denpasar | 1.0735 | 0.3752 | 1.7772 | 2 | B |

| Balikpapan | 1.0996 | 0.1237 | 1.8631 | 2 | B |

| Yogyakarta | 1.4825 | 0.7092 | 1.4648 | 2 | B |

| Malang | 1.1821 | 0.1242 | 1.8760 | 2 | B |

| Batam | 1.2125 | 0.1593 | 1.8829 | 2 | B |

| Pekanbaru | 1.2075 | 0.4581 | 1.5841 | 2 | B |

| Banjarmasin | 1.2125 | 0.1593 | 1.8829 | 2 | B |

| Pontianak | 1.7270 | 0.8534 | 2.1285 | 2 | B |

| Aspect | Criteria | Initial Weight | Type | Sensitivity Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economics | GDP | 0.11540 | Benefit | 0.61540 |

| IC | 0.09617 | Cost | 0.59617 | |

| EE | 0.18753 | Benefit | 0.68753 | |

| ICA | 0.07240 | Benefit | 0.57240 | |

| IQ | 0.01479 | Benefit | 0.51479 | |

| Social | PD | 0.07602 | Cost | 0.57602 |

| EI | 0.08362 | Benefit | 0.58362 | |

| PTQ | 0.01450 | Benefit | 0.51450 | |

| UP | 0.01553 | Benefit | 0.51553 | |

| Environment | PCE | 0.14425 | Cost | 0.64425 |

| IMR | 0.02947 | Benefit | 0.52947 | |

| W2E | 0.01708 | Benefit | 0.51708 | |

| LUP | 0.02357 | Benefit | 0.52357 | |

| CRP | 0.01964 | Benefit | 0.51964 | |

| GI | 0.03831 | Benefit | 0.53831 | |

| Politics | RS | 0.05172 | Benefit | 0.55172 |

| City | Aspects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Economics | Social | Environment | Politics | |

| Jakarta | 0.1332 | 1.8728 | -0.0949 | 0.1776 | 0.1971 |

| Surabaya | 0.1083 | 1.6207 | 0.2419 | 0.6527 | 0.1722 |

| Bandung | 0.0590 | 1.7986 | 0.3309 | 0.6034 | 0.1229 |

| Medan | -0.5406 | -0.5737 | -1.4070 | -0.9961 | -0.9766 |

| Semarang | -0.0040 | 1.4630 | 0.2679 | 0.5405 | 0.0600 |

| Makassar | -0.0804 | 0.8865 | 0.0532 | 0.4641 | -0.0164 |

| Palembang | -0.0040 | 1.4630 | 0.2679 | 0.5405 | 0.0600 |

| Denpasar | -0.2882 | 0.4515 | -0.6546 | -0.7437 | -0.2242 |

| Balikpapan | -0.2882 | 0.4515 | -0.6546 | -0.7437 | -0.2242 |

| Yogyakarta | -0.2882 | 0.4515 | -0.6546 | -0.7437 | -0.2242 |

| Malang | -0.2122 | 0.5275 | -0.0786 | -0.6677 | -0.1482 |

| Batam | -0.2122 | 0.5275 | -0.0786 | -0.6677 | -0.1482 |

| Pekanbaru | -0.0040 | 1.4630 | 0.2679 | 0.5405 | 0.0600 |

| Banjarmasin | -0.2882 | 0.4515 | -0.6546 | -0.7437 | -0.2242 |

| Pontianak | -0.0800 | 1.3869 | -0.3081 | 0.4645 | -0.0160 |

| City | Aspects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Economics | Social | Environment | Politics | |

| Jakarta | 0.7960 | 1.5100 | 0.2442 | 1.2000 | 2.4000 |

| Surabaya | 1.4090 | 0.6824 | 1.9000 | 1.2000 | 1.6900 |

| Bandung | 0.6810 | 0.5176 | 0.6479 | 0.8781 | 0.6105 |

| Medan | 0.5233 | 1.7000 | 1.6000 | 0.1233 | 0.0663 |

| Semarang | 0.6548 | 0.4382 | 0.3777 | 0.7237 | 0.3020 |

| Makassar | 1.4470 | 0.8460 | 0.7389 | 0.8418 | 1.0200 |

| Palembang | 1.0995 | 0.3502 | 0.3777 | 0.7237 | 0.3020 |

| Denpasar | 0.3752 | 0.3013 | 0.2912 | 1.3000 | 0.5154 |

| Balikpapan | 0.1237 | 0.3002 | 0.2912 | 1.4000 | 0.5154 |

| Yogyakarta | 0.7092 | 0.3286 | 0.2912 | 1.4000 | 0.5154 |

| Malang | 0.1242 | 0.7651 | 0.8118 | 1.1000 | 0.8657 |

| Batam | 0.1593 | 0.7663 | 0.8118 | 1.1000 | 0.8657 |

| Pekanbaru | 0.4581 | 0.4288 | 0.3777 | 0.7237 | 0.3020 |

| Banjarmasin | 0.1593 | 0.3074 | 0.2912 | 1.4000 | 0.5154 |

| Pontianak | 0.8534 | 1.1600 | 0.8710 | 0.7237 | 0.7065 |

| City | PSOM | K-Means | K-Medoid | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C1 | C2 | C3 | |

| Jakarta | 2.5791 | 2.3419 | 0.7960 | 0.2308 | 0.2159 | 0.0279 | 6.4981 | 7.8268 | 0.0000 |

| Surabaya | 1.0409 | 1.7120 | 2.6131 | 0.2112 | 0.1938 | 0.0279 | 5.3791 | 5.7606 | 3.9550 |

| Bandung | 0.6810 | 1.3807 | 2.1166 | 0.0553 | 0.1533 | 0.2102 | 4.9053 | 1.8555 | 7.2203 |

| Medan | 0.5233 | 1.1751 | 2.0222 | 0.2315 | 0.1234 | 0.2526 | 7.2022 | 8.8650 | 9.7004 |

| Semarang | 1.1352 | 0.6548 | 1.8289 | 0.0204 | 0.1397 | 0.2267 | 4.5407 | 4.2146 | 7.8268 |

| Makassar | 1.8333 | 1.8541 | 1.4470 | 0.0631 | 0.1191 | 0.2145 | 3.8589 | 2.3931 | 6.9846 |

| Palembang | 1.9556 | 1.7045 | 1.0995 | 0.0204 | 0.1397 | 0.2267 | 4.5407 | 4.2146 | 7.8268 |

| Denpasar | 1.0735 | 0.3752 | 1.7772 | 0.1272 | 0.0296 | 0.2091 | 0.0000 | 4.5407 | 6.4981 |

| Balikpapan | 1.0996 | 0.1237 | 1.8631 | 0.1272 | 0.0296 | 0.2091 | 0.0000 | 4.5407 | 6.4981 |

| Yogyakarta | 1.4825 | 0.7092 | 1.4648 | 0.1272 | 0.0296 | 0.2091 | 0.0000 | 4.5407 | 6.4981 |

| Malang | 1.1821 | 0.1242 | 1.8760 | 0.1110 | 0.0579 | 0.1948 | 2.0412 | 4.0561 | 6.1692 |

| Banjarmasin | 1.2125 | 0.1593 | 1.8829 | 0.1272 | 0.0296 | 0.2091 | 0.0000 | 4.5407 | 6.4981 |

| Pontianak | 1.7270 | 0.8534 | 2.1285 | 0.0653 | 0.1306 | 0.2391 | 4.0561 | 2.0412 | 8.0886 |

| City | EE | PCE | GDP | IC | EI | PD | ICA | RS | GI | IMR | LUP | CRP | W2E | UP | IQ | PTQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bogor | 0.63 | 1.8 | 12000 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 14000 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.12 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.56 |

| Manado | 0.67 | 2.1 | 11500 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 10500 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.13 | 0.59 | 0.51 | 0.22 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.60 |

| Samarinda | 0.71 | 2.3 | 13500 | 0.39 | 0.60 | 12000 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.22 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.30 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.66 |

| Jambi | 0.62 | 1.7 | 12500 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 11000 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.16 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.51 |

| Padang | 0.69 | 2.5 | 16000 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 15000 | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.21 | 0.69 | 0.60 | 0.27 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.62 |

| Kupang | 0.55 | 1.9 | 11000 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 9800 | 0.44 | 0.5 | 0.42 | 0.09 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.14 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.49 |

| Mataram | 0.68 | 2.4 | 14500 | 0.48 | 0.64 | 16000 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.24 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.28 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.72 |

| T.Pinang | 0.66 | 2.1 | 13000 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 12500 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.12 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.20 | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.60 |

| Kendari | 0.72 | 2.0 | 14000 | 0.44 | 0.61 | 9000 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.20 | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.25 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.64 |

| Palu | 0.74 | 2.6 | 16000 | 0.46 | 0.66 | 11000 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.23 | 0.72 | 0.68 | 0.30 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.68 |

| Ambon | 0.59 | 1.5 | 3000 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 10500 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.11 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.17 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.55 |

| Bengkulu | 0.65 | 2.3 | 14500 | 0.42 | 0.57 | 9500 | 0.56 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.18 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.26 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).