Submitted:

12 February 2025

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

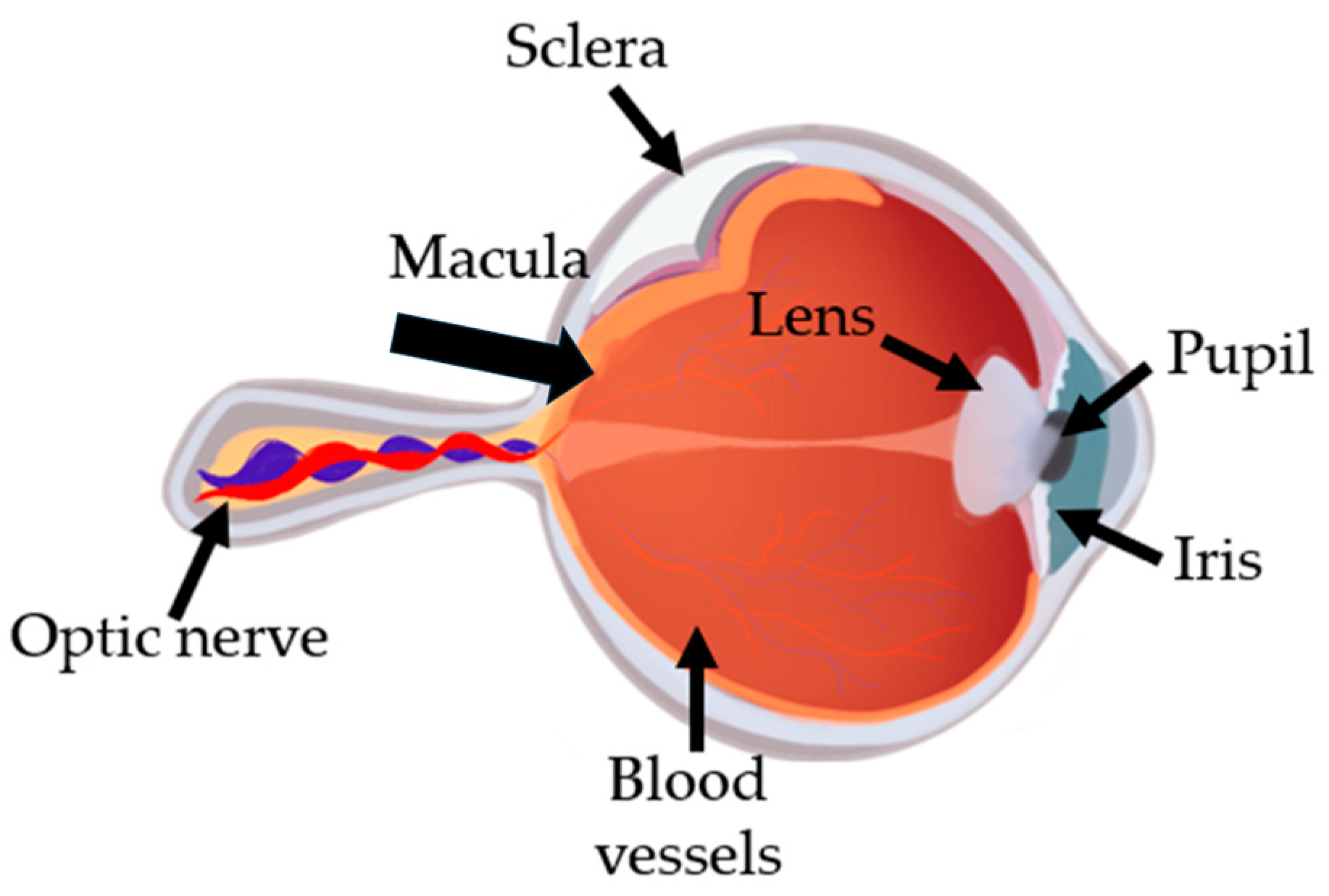

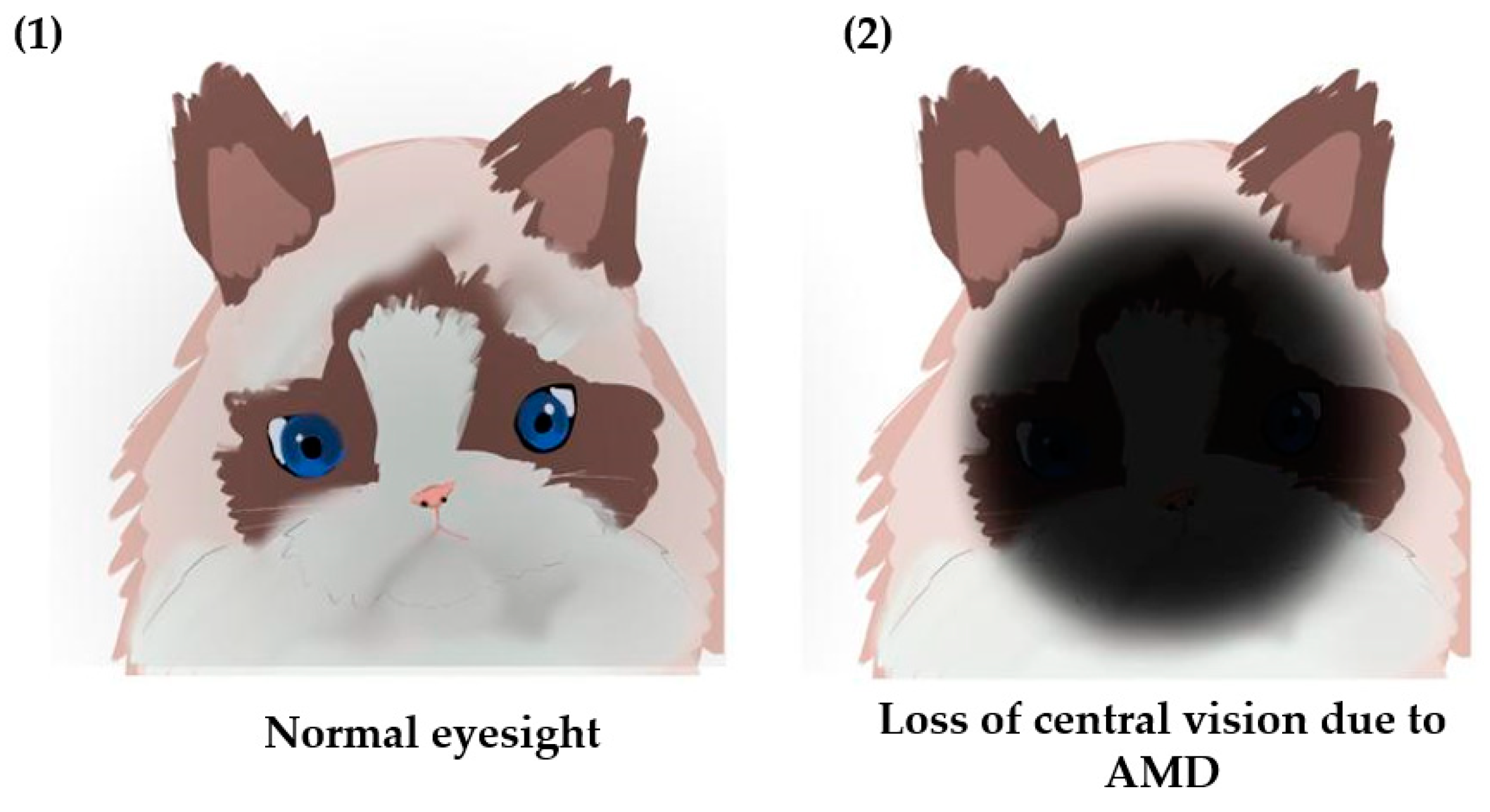

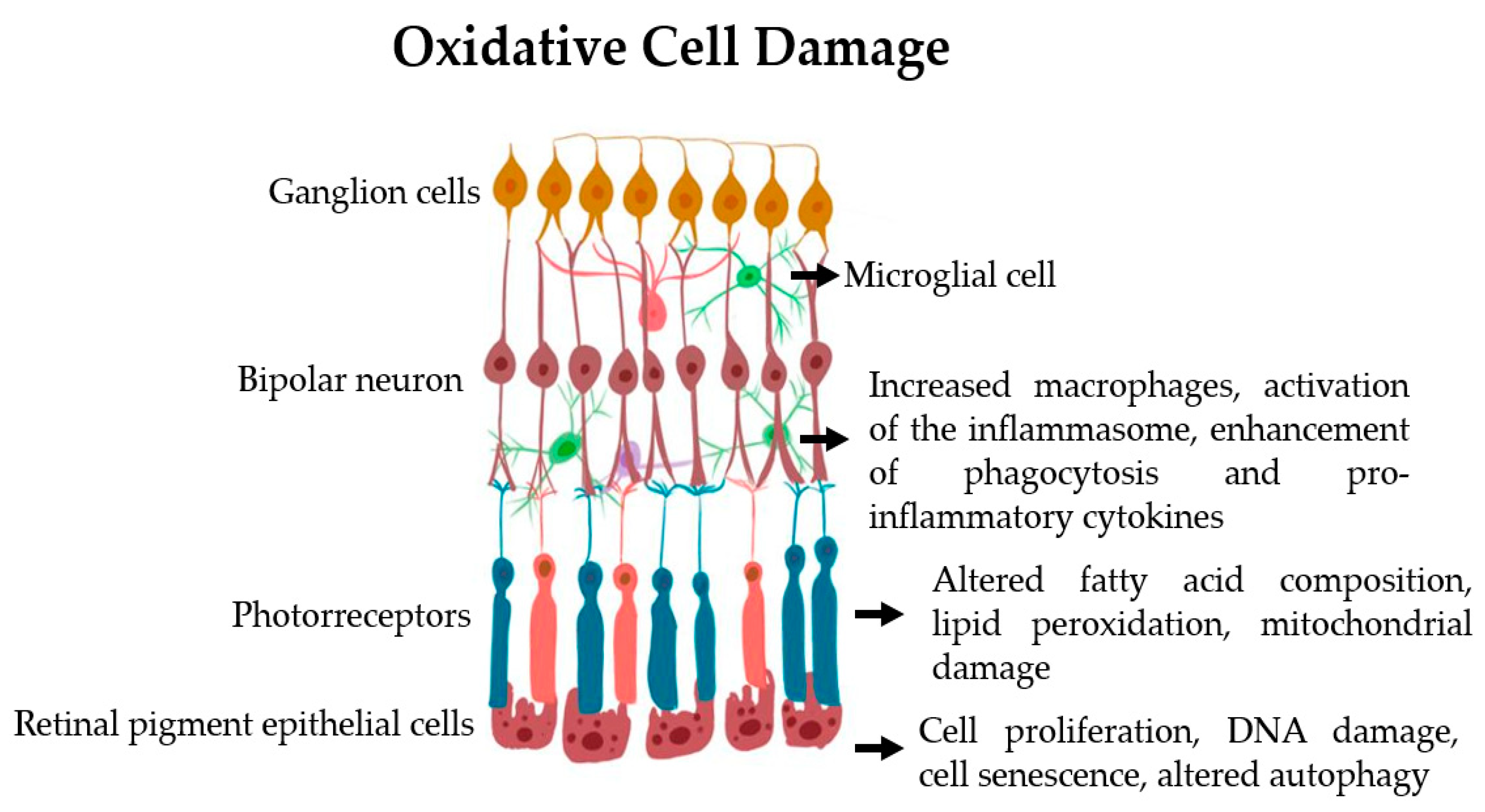

1.1. Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)

1.2. Brown Algae

2. Bioactive Compounds

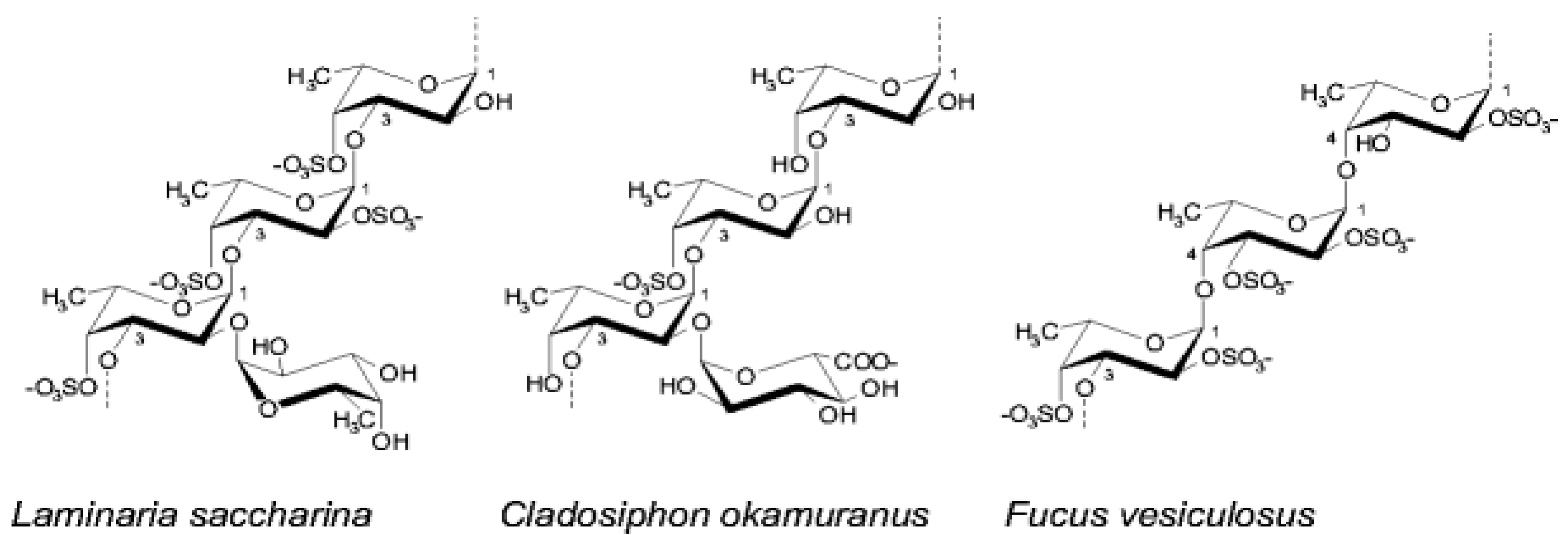

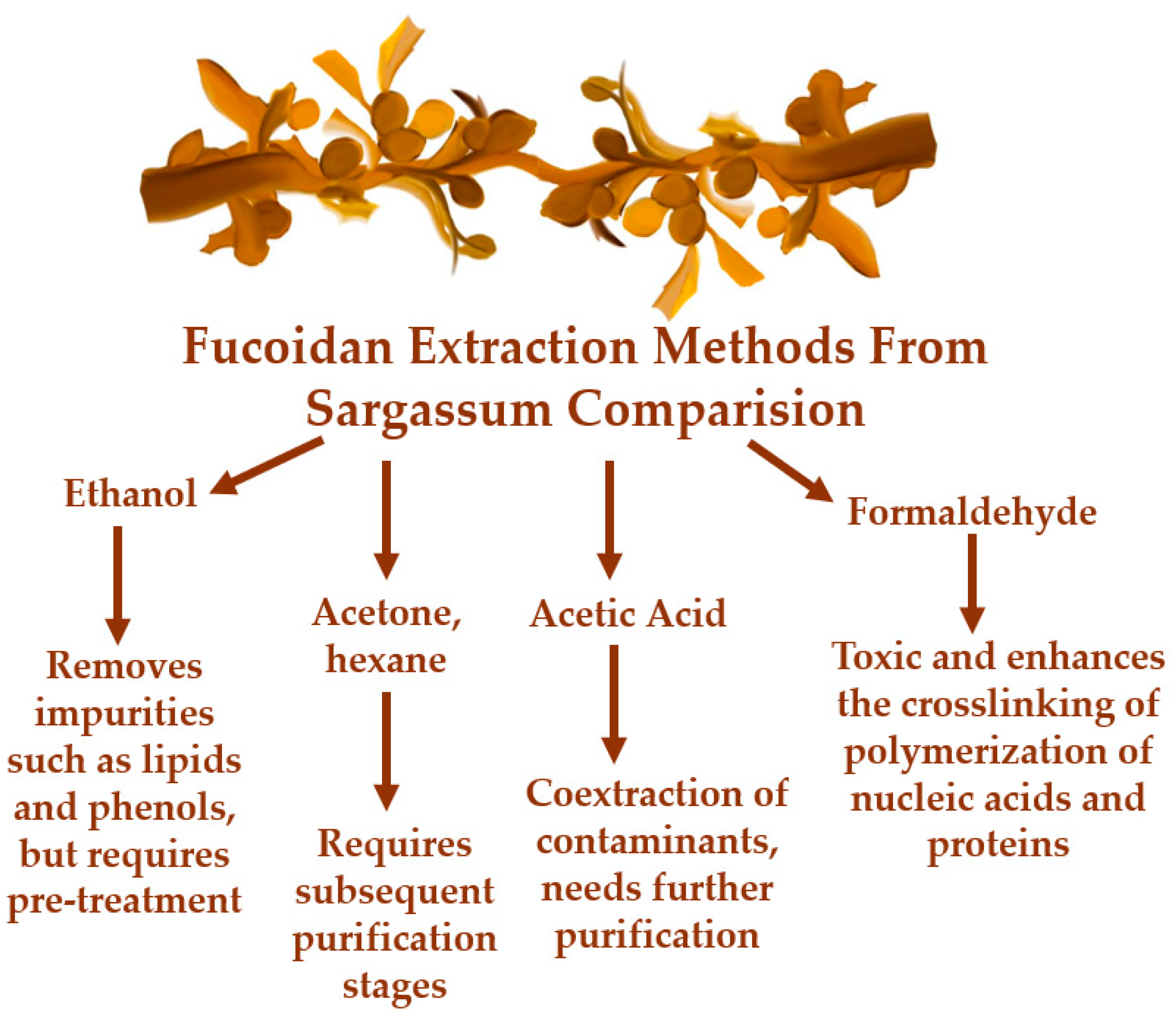

2.1. Fucoidan

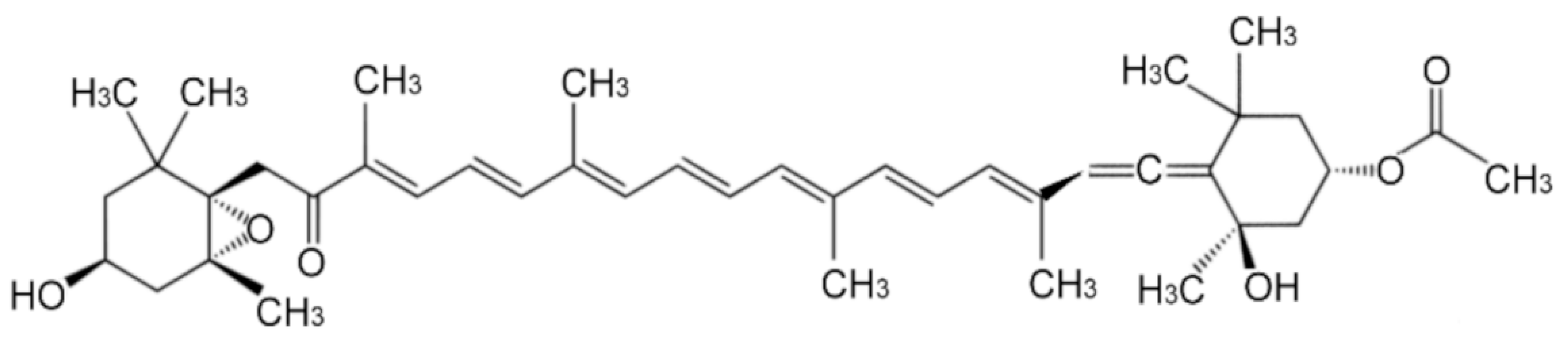

2.3. Fucoxanthin and Fucoxanthinol

3. Additional Challenge for the Use of Fucoidan in AMD

4. Conclusions

References

- Mitchell, P.; Liew, G.; Gopinath, B.; Wong, T.Y. Age-related macular degeneration. Lancet 2018, 1147–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Q.; Tham, Y.; Rim, T.H.; Kithinji, D.M.; Wu, J.; Cheng, C.; Liang, H.; et al. Global Incidence, Progression, and Risk Factors of Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Projection of Disease Statistics in 30 Years: A Modeling Study. Gerontology 2021, 68, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, S.; Cano, M.; Ebrahimi, K.; Wang, L.; Handa, J.T. The impact of oxidative stress and inflammation on RPE degeneration in non-neovascular AMD. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2017, 60, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P.X.; Stiles, T.; Douglas, C.; Ho, D.; Fan, W.; Du, H. ; Xiao, X Oxidative stress, innate immunity, and age-related macular degeneration. AIMS molecular science 2016, 196–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, J.B. Updates on the Epidemiology of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2017, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutto, I.; Lutty, G. Understanding age-related macular degeneration (AMD): Relationships between the photoreceptor/retinal pigment epithelium/Bruch’s membrane/choriocapillaris complex. Mol. Asp. Med. 2012, 33, 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleckenstein, M.; Schmitz-Valckenberg, S.; Chakravarthy, U. Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Review. JAMA 2024, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, A.; Mahdi, L.; Musat, O. Age-related macular degeneration. Rom J Ophthalmol 2015, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsche, L.; Igl, W.; Cooke-Bailey, J.N.; Grassmann, F.; Sengupta, S. Nat Genet 2016, 134–143. [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Carsten, B.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative Stress. Annu Rev Biochem 2017, 715–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klettner, A. Oxidative stress induced cellular signaling in RPE cells. Frontiers in bioscience (Scholar edition) 2012, 392–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, M.; Milliner, C.; Bell, B.A.; Bonilha, V.L. Oxidative stress in the retina and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE): Role of aging, and DJ-1. Redox Biol 2020, 37, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T.; Shimazawa, M.; Hara, H. Retinal Diseases Associated with Oxidative Stress and the Effects of a Free Radical Scavenger (Edaravone). Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 9208489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Chong, V.; Loewenstein, A.; Larsen, M.; Souied, E.; Schlingemann, R.; Eldem, B.; Monés, J.; Richard, G.; Bandello, F. Guidelines for the management of neovascular age-related macular degeneration by the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA). Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 98, 1144–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hytti, M.; Korhonen, E.; Hongisto, H.; Kaarniranta, K.; Skottman, H.; Kauppinen, A. Differential Expression of Inflammasome-Related Genes in Induced Pluripotent Stem-Cell-Derived Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells with or without History of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, W.M.; McCollum, G.W.; Savage, S.R.; Capozzi, M.E.; Penn, J.S.; Morrison, D.G. Hypoxia-induced expression of VEGF splice variants and protein in four retinal cell types. Experimental eye research 2013, 116, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klettner, A.; Koinzer, S.; Meyer, T.; Roider, J. Toll-like receptor 3 activation in retinal pigment epithelium cells – Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways of cell death and vascular endothelial growth factor secretion. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013, 91, e211–e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgis, S.; Lee, L.R. Treatment of dry age-related macular degeneration: A review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2023, 51, 835–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klettner, A. Fucoidan as a Potential Therapeutic for Major Blinding Diseases—A Hypothesis. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y. Fucoxanthin Pretreatment Ameliorates Visible Light-Induced Phagocytosis Disruption of RPE Cells under a Lipid-Rich Environment via the Nrf2 Pathway. Mar. Drugs 2021, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stengel, D.; Connan, S. ; Popper, Z Algal chemo diversity and bioactivity: Sources of natural variability and implications for commercial application. Biotechnology Advances 2011, 483–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangestuti, R. Biological activities and health beneft effects of natural pigments derived from marine algae. Journal of Functional Foods 2011, 3, 255–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohibbullah, M.; Haque, M.; Sohag, A.; Hossain, M.; Zahan, M.; Uddin, M.; Hannan, M.; Moon, I.; Choi, J. A Systematic Review on Marine Algae-Derived Fucoxanthin: An Update of Pharmacological Insights. Mar Drugs 2022, 20, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörschmann, P.; Klettner, A. Fucoidans as Potential Therapeutics for Age-Related Macular Degeneration—Current Evidence from In Vitro Research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, A.; El-Aasr, M.; Ibrahim, A.-R.S.; Ulber, R. Fucoidan Characterization: Determination of Purity and Physicochemical and Chemical Properties. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardena, T.U.; Nagahawatta, D.P.; Fernando, I.P.S.; Kim, Y.-T.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, W.-S.; Lee, J.S.; Jeon, Y.-J. A Review on Fucoidan Structure, Extraction Techniques, and Its Role as an Immunomodulatory Agent. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.G.; Jayawardena, T.U.; Liyanage, N.; Song, K.-M.; Choi, Y.-S.; Jeon, Y.-J.; Kang, M.-C. Antioxidant potential of low molecular weight fucoidans from Sargassum autumnale against H2O2-induced oxidative stress in vitro and in zebr. Food Chemistry 2022, 132591. [Google Scholar]

- Marudhupandi, T.; Kumar, T.A.; Lakshmana-Senthil, S.; Nanthini-Devi, K. Invitro antioxidant properties of fucoidans fractions from Sargassum tenerrimum. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences 2014, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-Y.; Wu, S.-J.; Yang, W.-N.; Kuan, A.-W.; Chen, C.-Y. Antioxidant activities of crude extracts of fucoidan extracted from Sargassum glaucescens by a compressional-puffing-hydrothermal extraction process. Food Chem. 2016, 197, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, A.; Al-Saedi, D.A.; Mensah, E.O.; Kanwugu, O.N.; Adadi, P.; Ulber, R. Fucoidan’s Molecular Targets: A Comprehensive Review of Its Unique and Multiple Targets Accounting for Promising Bioactivities Supported by In Silico Studies. Mar. Drugs 2023, 22, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörschmann, P.; Mikkelsen, M.D.; Thi, T.N.; Roider, J.; Meyer, A.S.; Klettner, A. Effects of a Newly Developed Enzyme-Assisted Extraction Method on the Biological Activities of Fucoidans in Ocular Cells. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dörschmann, P.; Bittkau, K.S.; Neupane, S.; Roider, J.; Alban, S.; Klettner, A. Effects of Fucoidans from Five Different Brown Algae on Oxidative Stress and VEGF Interference in Ocular Cells. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Wan, Y.; Hu, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, J. In vivo immunomodulatory activity of fucoidan from brown alga Undaria pinnatifida in sarcoma 180-bearing mice. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dithmer, M.; Fuchs, S.; Shi, Y.; Schmidt, H.; Richert, E.; Roider, J.; Klettner, A. Fucoidan Reduces Secretion and Expression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in the Retinal Pigment Epithelium and Reduces Angiogenesis In Vitro. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e89150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozharitskaya, O.; Obluchinskaya, E.; Shikov, A.N. Mechanisms of Bioactivities of Fucoidan from the Brown Seaweed Fucus vesiculosus L. of the Barents. Sea. Mar Drugs 2020, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smale, D.A.; Pessarrodona, A.; King, N.; Burrows, M.T.; Yunnie, A.; Vance, T.; Moore, P. Environmental factors influencing primary productivity of the forest-forming kelp Laminaria hyperborea in the northeast Atlantic. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörschmann, P.; Kopplin, G.; Roider, J.; Klettner, A. Interaction of High-Molecular Weight Fucoidan from Laminaria hyperborea with Natural Functions of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stévant, P.; Rebours, C.; Chapman, A. Seaweed aquaculture in Norway: recent industrial developments and future perspectives. Aquac. Int. 2017, 25, 1373–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yuan, J.-P.; Wu, C.-F.; Wang, J.-H. Fucoxanthin, a Marine Carotenoid Present in Brown Seaweeds and Diatoms: Metabolism and Bioactivities Relevant to Human Health. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 1806–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-L.; Liang, A.-L.; Hu, M.-L. Protective effects of fucoxanthin against ferric nitrilotriacetate-induced oxidative stress in murine hepatic BNL CL.2 cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2011, 25, 1314–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Park, Y.-J.; Jeon, Y.-J.; Ryu, B. Bioactivities of the edible brown seaweed, Undaria pinnatifida: A review. Aquaculture 2018, 495, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, U.; Derwenskus, F.; Flaiz Flister, V.; Schmid-Staiger, U.; Hirth, T.; Bischoff, S.C. Fucoxanthin, A Carotenoid Derived from Phaeodactylum tricornutum Exerts Antiproliferative and Antioxidant Activities In Vitro. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandi, A.C.; Molina, N.; Guerra, B.A.; Bolin, A.P.; Otton, R. Fucoxanthin in association with Vitamin c acts as modulators of human neutrophil function. Eur. J. Nutr. 2013, 53, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cheng, C.; Liu, C.; Sue, Y.; Chen, T.; Hsu, Y.; Hwang, P.; Chen, C. Alleviative effect of fucoxanth in containing extract from brown seaweed Laminaria japonica on renal tubular cell apoptosis through upregulating Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1 in chronic kidney disease mice J. Ethnopharmacol 2018, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpi´nski, T.; Adamczak, A. Fucoxanthin—An Antibacterial Carotenoid. Antioxidants 2019, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y. Anti-Inflammatory and Apoptotic Signaling Effect of Fucoxanthin on Benzo(A)Pyrene-Induced Lung Cancer in Mice. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2019, 38, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.-J.; Lin, T.-B.; Peng, H.-Y.; Liu, H.-J.; Lee, A.-S.; Lin, C.-H.; Tseng, K.-W. Cytoprotective Potential of Fucoxanthin in Oxidative Stress-Induced Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cell Senescence In Vivo and In Vitro. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.J.; Yoon, W.J.; Kim, K.N.; Ahn, G.N.; Kang, S.M.; Kang, D.H.; Affan, A.; Oh, C.; Jung, W.K.; Jeon, Y.J. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory effect of fucoxanthin isolated from brown algae in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated raw 264.7 macrophages. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 2045–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Yuan, J.-P.; Wu, C.-F.; Wang, J.-H. Fucoxanthin, a Marine Carotenoid Present in Brown Seaweeds and Diatoms: Metabolism and Bioactivities Relevant to Human Health. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 1806–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.-J.; Ko, S.-C.; Kang, S.-M.; Kang, H.-S.; Kim, J.-P.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, K.-W.; Cho, M.-G.; Jeon, Y.-J. Cytoprotective effect of fucoxanthin isolated from brown algae Sargassum siliquastrum against H2O2-induced cell damage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 228, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Heo, S.; Yoon, W.; Kang, S.; Ahn, G.; Yi, T.; Jeon, Y. Fucoxanthin inhibits the inflammatory response by suppressing the activation of NF-κB and MAPKs in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages. Eur. J. Pharmacol 2010, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irhimeh, M.; Fitton, J.; Lowenthal, R. Pilot clinical study to evaluate the anticoagulant activity of fucoidan. Blood Coagulation & Fibrinolysis: A International Journal in Haemostasis and Thrombosis 2009, 607–610. [Google Scholar]

- Tokita, Y.; Hirayama, M.; Nakajima, K.; Tamaki, K.; Iha, M.; Nagamine, T. Detection of Fucoidan in Urine after Oral Intake of Traditional Japanese Seaweed, Okinawa mozuku (Cladosiphon okamuranus Tokida). J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2017, 63, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irhimeh, M.R.; Fitton, J.H.; Lowenthal, R.M.; Kongtawelert, P. A quantitative method to detect fucoidan in human plasma using a novel antibody. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005, 27, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbs, T.; Zvyagintseva, T.; Ermakova, S. Is the transformation of fucoidans in human body possible? Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 142, 778–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokita, Y.; Nakajima, K.; Mochida, H.; Iha, M.; Nagamine, T. Development of a Fucoidan-Specific Antibody and Measurement of Fucoidan in Serum and Urine by Sandwich ELISA. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010, 74, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.H.; Lee, B.-J.; Tran, T.T. Current developments in the oral drug delivery of fucoidan. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 598, 120371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, K.; Takatani, N.; Beppu, F.; Abe, A.; Tominaga, E.; Fukuhara, T.; Ozeki, M.; Hosokawa, M.M. Enhances Bioavailability of Fucoxanthin in Diabetic/Obese KK-Ay Mice. Mar. Drugs 2022, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, V.; Mamatha, B.S. Fucoxanthin, a Functional Food Ingredient: Challenges in Bioavailability. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cell type | Disease Model | Concentration | Source | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microvascular endothelial cells |

High glucose | 12.5, 25, 50/mL | Fucoidan de L. japonica | Reduces VEGF (retina) | [19] Klettner, A et. 2016 |

| human colon carcinoma HT-29 | human colon | 0.272- 3.7mg/ml | Sargassum glaucescens | Antioxidant | [29] Huang, C.-Y et al. 2016 |

| primary porcine RPE cells (brighfield, 50×) | uveal melanoma cell line (OMM-1) | 1, 50 and 100 µgç |

Saccharina latissima And Laminaria hyperborea |

Reduces VEGF | [24] Klettner, A et al. 2020 |

| Murine S180 cell line | in vitro | 100, 200 and 300 mg/kg/day) | Undaria pinnatifida | Immunomodulatory | [33]. Qin Li et al. 2023 |

| RAW 264.7 macrophage cells | in vitro and in zebra fish | 25,50,100,200 µg/mL | Sargassum autumnale | anti-inflammatory | [27] Lee, H.U et al. |

| RAW 264.7 macrophage cells | in vitro | 10,50,250,5000 and 1000 µg/mL | Sargassum tenerrimum | Antioxidant | [28] Marudhupandi, T. et al. 2014 |

| primary porcine RPE cells (brighfield, 50×) | OMM-1 Cells | 100 µM, 200µM, 400 µM1000 µM | Fucus vesiculosus, Fucus distichus subsp. evanescens, Fucus serratus, Laminaria digitata, Saccharina latissima | Oxidative Stress and reduces VEGF | [32].P. Dörschmann et al. 2019 |

| ARPE-19 and porcine RPE-cells, | OMM-1 Cells | 100 µg/mL | Fucus vesiculosus | reduces VEGF |

[34] M. Dithmer et al. 2014 |

| ARPE-19 cells | In Vivo and In Vitro | 0.1,1 and 10 mg/kg | Hijikia fusiformis, Laminaria japonica and Sargassum fulvellum | Cytoprotective | [[47[M1] ]Chen, S.-J et al. 2021 |

| RAW 264.7 macrophage cells | In vitro | 12.5, 25 and 50 µM | Ishige okamurae | anti-inflammatory | [51]K.-N. Kim et al. 2010 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).